Abstract

This study aims to investigate the protective effects of curcumin (CUR) in high glucose (HG)-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis of primary cardiomyocytes by activating the Notch1 signaling pathway. CUR is a natural polyphenol isolated from turmeric rhizomes and is known for its antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory effects, particularly relevant in diabetes.Therefore, we used neonatal rat cardiomyocytes exposed to HG conditions, followed by treatment with CUR and DAPT, respectively. We detected and assessed myocardial cells viability and antioxidant enzyme activity by CCK-8 reagent and antioxidant enzyme kit. Apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry. The production of reactive oxygen species was detected by fluorescence labeling, and the expression of related genes and proteins was detected by qRT-PCR and Western blot. HG-induced primary rat cardiomyocytes not only increased apoptosis and ROS production, but also decreased the activity of antioxidant enzymes and the expression of Notch1 and Hes1 proteins. After pre-treatment by CUR, surprisingly, we found that CUR markedly improved viability of HG-treated cardiomyocytes. The results showed that CUR could inhibit the apoptosis of rat cardiomyocytes, inhibit the production of intracellular ROS, and increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes. Further, we found that CUR can upregulate the expression of Notch1 and Hes1 proteins and related genes, suggesting that the protective effect of CUR on HG-induced damage involves the Notch1/Hes1 signaling. These results suggest that CUR protects cardiomyocytes from HG-induced oxidative stress by activating Notch1 and its downstream target genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) is a special kind of cardiomyopathy in the state of diabetes, that is, extensive focal myocardial necrosis on the basis of microangiopathy, leading to subclinical cardiac dysfunction. It is not related to coronary artery disease, hypertension or other heart diseases. The incidence and prevalence of DCM have increased rapidly worldwide. Meanwhile, the incidence and mortality of cardiovascular diseases were associated with DCM in the past 50 years increased, too1. Hyperglycemia is a major feature of type I and type II diabetes, which can lead to excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in cardiomyocyte apoptosis, and then cause myocardial systolic dysfunction and promote the progression of DCM2. However, oxidative stress can be a double-edged sword, which can induce transient activation of antioxidant responses and prevent cytotoxicity3.DCM can trigger oxidative stress responses in myocardial cells. However, the specific relationship between oxidative stress and curcumin’s protective role remains unclear.

CUR, known as two acetyl methane (4-HO-3-MeO-C6H3)-CH = CH-CO-CH2-CO-CH = CH-(3-MeO-4-HO-C6H3), is an active ingredient in turmeric with non-toxic and non-mutagenic properties.In addition, CUR exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer properties, with potential therapeutic effects against liver, breast, heart diseases, and diabetes4,5. It has also been known that CUR protects cardiomyocytes against HG and ROS damage, and the antioxidant effect of CUR is to inhibit the production of ROS by inhibiting the opening of mitochondrial membrane potentials in cells6.

Notch homolog1, translocation-associated (Drosophila) (Notch1) signaling pathway can regulate variety cellular process (such as development, differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis and regeneration), which plays a vital role in various organisms and cell type, e.g. bone disease7,8. Notch1 signaling pathway is a cell communicate with each other’s platform, which plays an important regulatory role in the development of cardiac growth and differentiation in the embryonic stage and the progression of cardiomyopathy. Notch1 protein activated and released by the tumor necrosis factor -alpha (TNF-α) converting enzyme (TACE) and γ-secretase complex. It releases the Notch intracellular domain (N1ICD), and then combines the transcriptional factor CSL (CBF-1 in humans)9. After translocation of N1ICD into the nucleus, Notch promotes its target gene Hes. In the heart, Notch1 signaling not only regulates the development and differentiation of embryonic heart, but also stimulates the proliferation of immature cardiac myocytes10,11.

Studies have shown that Notch1 signaling pathway is closely related to nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway and other signaling pathways12. Notch ligand Dll1 and its target genes Hes1 and Hes3 can upregulate the expression of Nrf2 and its target genes, so as to reduce ROS formation and counteract oxidative stress13. However, up to now, it remains unclear whether CUR improves HG-mediated oxidative stress and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes by activating the Notch1 pathway. Therefore, the present study was designed to explore the potential protective mechanisms of CUR on primary rat cardiomyocytes using an in vitro model of HG-induced myocardial injury, and to study the role of Notch1 in the oxidative damage induced by HG. The present study may provide possible molecular mechanisms underlying the effect of CUR as a potent treatment for DCM.

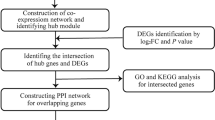

Materials and methods

Cell culture and determination of CUR concentration and cell viability

The Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased from Nanjing Medical University’s Animal Centre. All animal experiments were performed under the procedures approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Nanjing first hospital. The previously described protocol was used to isolate neonatal rat cardiomyocytes from Sprague-Dawley rats (1 day old)13. Cells were cultured at 37 ℃ in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. The cells were assigned to the following groups for 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, 48 h, respectively. The experiment group: the normal glucose (NG) medium (5.5 mM) group, high glucose (HG, 33 mM) medium group, and HG + CUR (5, 10, 20, 40 µM, respectively) group (purity > 98%; Aladdin Biochemical Technology Company, Shanghai, China). Then 10 µL of Cell Counting Kit 8 (CCK-8, TransGen Biotech) solution was added to each well. Incubation in the CO2 incubator was continued for 1.5 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader (ThermoFisher Scientific). We used the CCK-8 reagent to detect cell viability treated with X µM CUR and DAPT for 36 h.

Detection of intracellular

ROS Myocardial cells were incubated in 6-well plates at 2 × 105 cells/well. The accumulation of ROS in the cells was detected by fluorescence probe 2, 7- two, chlorofluorescein two acetate (DCFH-DA). DCFH-DA can be transformed into DCFH2 by intracellular lactase and then oxidized to high fluorescence DCF by ROS. DCFH-DA is diluted with DMEM to 10 µM. H9C2 cardiac myocytes were cultured in 60 mm cell dishes, removing cell culture medium and adding 1 mL diluted DCFH-DA. The cell incubator was incubated for 20 min at 37 ℃. The cells were washed with serum free medium for three times to remove DCFH-DA from the cells. Observation under fluorescence microscope.

Detection of cell apoptosis

Apoptosis detected by annexin V/propidium iodide (PI) staining: in a 10 cm culture dish, myocardial cells were grown at a density of 1 × 106 cells per dish. After allowing sufficient incubation, the supernatant was removed. and the pellet was re-suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). After the suspension was centrifuged at 1000 rpm at 4℃ for 5 min, the resulting precipitates were then re-dispersed in 200 µL of binding buffer, 10 µL of Annexin V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and 10 µL of propidium iodide (from Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co.) were subsequently incorporated into the solution. Then add 300 µL of binding buffer and gently mix for 15 min in a darkroom temperature setting. The apoptosis rate within 1 h was detected by flow cytometry.

Biochemical analysis

The cellular supernatants or precipitates were gathered. The assessment of superoxide dismutase (SOD), malondialdehyde (MDA), and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) activities was carried out, alongside the measurement of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) levels and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) contents, utilizing the respective assay kits provided by Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, in accordance with the instructions given by the manufacturer.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

For this, total RNA was extracted and subsequently converted into cDNA through the use of a reverse transcription kit (TruScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit)2. The StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system was employed to carry out qRT-PCR, with β-actin mRNA serving as the internal control. The sequences of the primers utilized were: β-actin: forward, 5’-CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC-3’ and reverse, 5’-CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT-3’; Notch1: forward, 5’-GAGGCGTGGCAGACTATGC-3’ and reverse, 5’-CTTGTACTCCGTCAGCGTGA-3’; Hes1: forward, 5’-TCAACACGACACCGGATAAAC-3’ and reverse, 5’-GCCGCGAGCTATCTTTCTTCA-3’.

Western blot analysis

Myocardial cells were cultured in 6 cm culture dish treated with CUR and DAPT for 36 h. Adding lysate into the culture dish.After lysis, the cells were scraped with one clean scraper on one side of the dish, and the cell debris and lysate were transferred to a 1.5 mL EP tube and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 15 min at 4 ℃. Take the supernatant, 100 µL/tube aliquot, take a small amount of BCA protein quantification, the remaining − 80 ℃ preservation. Take 1 tube protein plus 25 µL SDS-PAGE loading buffer, mixed, boiled for 10 min, and stored at -80 ℃ for Western blotting detection2. Proteins were separated using 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using primary antibodies for Notch1 (3608, CST), N1ICD (4147, CST), Hes1 (134202, Abcam, USA) and β-actin (8227, Abcam, USA). The intensity of each band was analyzed using Image Lab 4.0.1 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 23.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The experimental results are reported as means ± standard deviation (SD). Group comparisons were conducted utilizing a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA)2. For multiple comparisons where equal variances were not assumed, Tamhane’s T2 method was employed, and the LSD method was used to test multiple comparisons of homogeneity of assumed variances. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. A value of P < 0.01 was considered to indicate a statistically very significant difference.All datasets are included as Supplementary Table S1.

Results

CUR increased the viability of myocardial cells with HG-induced damage

The CCK-8 assay was used to detect the effective concentration of CUR on myocardial cells. We can find that cell viability of the HG + CUR group increased in a dose-dependent manner, and the cell viability was highest in the HG + 20 µM CUR group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1A). However, we found that the cell viability of the HG + CUR group treated with a higher concentration of CUR (40 µM) was reduced, and the cell culture time is best at 36 h (Fig. 1C). Therefore, in this study, we chose 20 µM concentration of CUR and cultivated for 36 h. As shown in Fig. 1B, the cell viability in the HG group was significantly lower than that in the normal group (P < 0.01). The cell viability of the HG + CUR group was significantly higher than that of the HG group. Furthermore, the cell viability of the HG + DAPT group was significantly lower than that of the HG group. The results showed that DAPT significantly inhibited the protective effect of CUR (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1B).

CUR increased viability of myocardial cells subjected to HG injury. (A) Rat myocardial cells were incubated with CUR (concentration gradient 5, 10, 20, 40 µM, respectively). (B) The HG group decreased the viability of myocardial cells, whereas HG + CUR treatment increased the cell viability, while treatment of the Notch1 inhibitor DAPT abolished the effects of CUR on cell viability. (C) Cell viability was determined using the TransDetect™ Cell Counting Kit (CCK)-8 assay at varying concentrations of CUR at different timepoints (12, 24, 36, and 48 h).**P < 0.01, ΔΔP < 0.01, and ##P < 0.01 versus 20 µM CUR group at 12, 24, 36, 48 h, respectively (A). **P < 0.01 HG group vs. HG + CUR group, *P < 0.05 HG group vs. HG + DAPT group, **P < 0.01 HG + CUR group vs. HG + CUR + DAPT group (B). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 3.

CUR can reduce the formation of ROS under conditions of HG damage

A high glucose injury model was established and DCFH-DA was used to detect intracellular ROS. The results showed that ROS formation in the HG-treated myocardial cells increased significantly (P < 0.01), while the HG + CUR group significantly decreased intracellular ROS levels (P < 0.01). In contrast, co-treatment with DAPT reversed CUR’s suppression of ROS (P < 0.01). HG + CUR + DAPT and HG group had no significant changes, indicating that DAPT increased ROS production (Fig. 2).

CUR pretreatment decreased the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. (A) ROS generation was measured using DCF fluorescence analysis. Representative images of the intracellular ROS production are shown (100×). (B) The DCF+ numbers significantly increased in the HG group and HG + DAPT group (**P < 0.01 vs. HG + CUR group) and decreased in HG + CUR + DAPT groups (**P < 0.01 vs.HG + CUR group).Data are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 3.

CUR inhibited cardiomyocyte apoptosis under HG

The HG model was established and Annexin V/PI was used to detect apoptosis. The double staining flow cytometry analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the normal group and the mannitol group (Fig. 3A). The apoptosis rate of the HG + CUR group was lower than that of the HG group(P < 0.01). It indicated that activation of Notch1 signal can reduce cardiomyocyte apoptosis after HG. However, the HG + DAPT group significantly increased the rate of cardiomyocyte apoptosis compared to the HG group (P < 0.01). It proved that activation of Notch1 signal can reduce myocardial apoptosis induced by high glucose. The apoptosis rate of the HG + CUR + DAPT and the HG + DAPT group were higher than that of the HG + CUR group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3B). There was no significant difference in apoptosis between the control group and the mannitol group.

CUR inhibited the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes, and can regulate the activity of antioxidant enzymes. (A) Representative dot plots of flow cytometry (the x-axis and y-axis represent Annexin V and PI staining, respectively). (B) Evaluation of apoptotic cell populations.The apoptosis rate of HG + CUR group was significantly lower than that of HG group and HG + DAPT group, there were obvious statistical significance (**P < 0.01). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 3.

CUR attenuated HG-induced oxidative stress injury

The activities of SOD, MDA, HO-1, NADPH and GSH-Px were measured using the related kit. The activity of the HG + DAPT group was significantly lower than that of the HG group. However, the activity of the antioxidant enzymes in the HG + CUR group was significantly higher than that of the HG group. The activity of the antioxidant enzymes in the HG + CUR + DAPT group was lower than that in the HG + CUR group, except for MDA. However, it was higher than in the HG + DAPT group (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4).

The contents of malondialdehyde (MDA) and the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH), and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) induced by high glucose (HG) injury. The activities of SOD, HO-1, NADPH, and GSH-Px were significantly increased in the HG + CUR group (**P < 0.01 vs. HG group) and were decreased in both the HG + CUR + DAPT and HG + DAPT groups (**P < 0.01 vs. HG + CUR group). However, the contents of MDA showed the opposite trends. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 3.

CUR upregulated Notch1 and N1ICD expression

The result shows that the gene and protein of Notch1 and Hes1 levels are highly expressed in the HG + CUR group (Fig. 5A-D). The HG + DAPT groups had significantly lower protein levels compared to the HG group (P < 0.01). Similarly, the expression of Hes1 protein in the HG + CUR group was similar to that of N1ICD. The HG + CUR protein expression level was higher than that of the HG, and the HG + CUR + DAPT (P < 0.01). There is no difference between the Control group and Mannitol group (Fig. 5E). DAPT and CUR affected the translocation of N1ICD from cytoplasm to the nucleus, CUR counteracted the blocking effect of DAPT on Notch1 signaling (Fig. 5F-H).

CUR activated Notch1 signaling pathways. (A, B) Rat myocardial cells were incubated in HG-treated with or without CUR for 36 h, respectively. qRT-PCR was applied to detect the mRNA expression of Notch1 and Hes1 genes. (C) Notch1, N1ICD and Hes1 protein expression were evaluated by western blotting; β-actin was used as an internal control. (D) DAPT and CUR affected the translocation of N1ICD from cytoplam to the nucles.CUR promoted N1ICD translocation into the nucleus. (E-G) The expression levels of Notch1, N1ICD and Hes1 proteins significantly increased in the HG + CUR group (**P < 0.01 vs. HG group) and decreased in both the HG + CUR + DAPT (**P < 0.01 vs. HG + CUR group). (H) The expression levels of N1ICD proteins in nuclear significantly increased in both the HG + CUR group (**P < 0.01 vs. HG group, and **P < 0.01 vs. HG + CUR + DAPT). Data are expressed as the mean ± SD, n = 3.

Discussion

This investigation revealed that exposure to high glucose levels diminished cell viability, intensified oxidative stress, and triggered apoptosis in the cardiomyocytes obtained from rats. Conversely, treatment with CUR led to an enhancement in cell viability. This enhancement was dependent on both dosage and duration. Additionally, CUR alleviated oxidative stress within the cells. This effect correlated with a decrease in the production of reactive oxygen species and a reduction in apoptosis. Furthermore, there was an increase in the activity of antioxidant enzymes. In addition, CUR treatment enhanced the levels of Notch1 and hes1 expression under high glucose conditions. The application of the Notch1 antagonist DAPT significantly diminished the CUR-induced elevation of Notch1 and Hes1, thereby hindering the protective effects of CUR on cardiomyocytes. This indicates that CUR may provide cardioprotective effects partly through the Notch1/Hes1 signaling pathway.

CUR, a polyphenolic compound derived from Curcuma longa, has long been used in traditional medicine, is a polyphenolic substance4. Often referred to as curcumin, it has been extensively utilized in traditional Chinese medicine. CUR is used for the management of cardiac complications associated with diabetes, neuropathy, kidney disease, retinal dysfunction, dysfunction of β cells in the islets, and vascular disorders. It significantly contributes to cardiovascular treatment by modulating antioxidant activity, effects that protect against cell death and inflammation5,6,14. Last year the beneficial impacts of CUR on heart health are well acknowledged, its role in mitigating cardiotoxicity caused by doxorubicin has been demonstrated for several years15. Research involving animals has indicated that CUR can also aid in lessening cardiac hypertrophy induced by lipopolysaccharides and in relieving myocardial fibrosis resulting from spontaneous hypertension, it also plays a role in averting heart failure16. Furthermore, CUR has been shown to facilitate cardiac regeneration and enhance heart function in a rat model of myocardial infarction17.

In this study, the results indicated a notable dose-dependent enhancement in the viability of cardiomyocytes with CUR treatment. To determine if the protective effect of CUR against HG-induced apoptosis in cardiomyocytes was linked to the reduction of oxidative stress, the levels of intracellular ROS were assessed using the DCFH-DA probe, revealing that CUR enhanced the function of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD. HO-1, NADPH and GSH Px, excluding MDA. At a CUR concentration of 20 µM, the viability of the cells reached its peak, suggesting that CUR can safeguard cardiomyocytes against injury from high glucose levels. However, in the HG + CUR group, administering a higher dose of 40 µM resulted in toxic effects, indicating that excessive doses of CUR could have detrimental effects (Fig. 1).

CUR participates in myocardial protection through a variety of pathways, such as SIRT1, NF-κB, JNK, and others18. The Notch1 signaling pathway involves a wide range of physiological processes, including mitosis, cell survival, metastasis and transcription in the state of stress19. In addition, the Notch1/Hes1 signaling pathway has been shown to protect myocardial cells and reduce myocardial injury20. To test whether Notch1 signaling mediates CUR’s protective effects on HG-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis, the highly active γ-secretase inhibitor DAPT blocks Notch cleavage. Our results show that when exposed to HG injury, the expression of Notch1 protein is highest when 20 µM CUR is administered. Meanwhile, we used DAPT (α-secretase inhibitor, which inhibits Notch1 signaling pathways) to eliminate these effects. In fact, these effects were eliminated when DAPT was used, indicating that the cardioprotective effects of CUR are related to the Notch1 signaling pathway. Therefore, we conferred that Notch1 may be involved in the protective effect of CUR on HG-induced cardiomyocyte injury.

CUR exerts a protective effect on cardiomyocytes against injuries induced by high glucose by activating the Notch1 signaling pathway, which results in enhanced cell viability, a lower rate of apoptosis, and diminished production of reactive oxygen species. In a similar way, the activation of the Notch1 signaling pathway resulted in enhanced cardiomyocyte survival, a reduction in apoptosis among the cardiomyocytes, and a decrease in damage caused by ROS.

Elevated glucose levels can trigger significant levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which contribute to oxidative stress damage21. The findings of this investigation illustrated that treatment with CUR resulted in a decrease in MDA levels and an enhancement in the activities of HO-1, SOD, GSH-Px, and NADPH. This suggests that CUR has the potential to mitigate the harm caused by HG in oxidative stress (Fig. 4). Research demonstrates that treatment with CUR can lower ROS levels that are provoked by HG. Research indicates that CUR may also inhibit the generation of ROS in N2A cells while alleviating oxidative stress effects in endothelial cells derived from human umbilical veins22.

While this study primarily demonstrates that curcumin (CUR) alleviates high glucose (HG)-induced cardiomyocyte oxidative stress and apoptosis through Notch1/Hes1 pathway activation, emerging evidence suggests that other regulated cell death mechanisms may also contribute to diabetic cardiomyopathy. For instance, ferroptosis, an iron-dependent process linked to glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) inactivation, has been implicated in diabetic cardiac complications and may interact with Notch1-mediated antioxidant responses23. Notably, the redox imbalance observed in HG-treated cardiomyocytes could potentially trigger alternative pathways such as cuproptosis24 or disulfidptosis25, given their shared dependence on metabolic and oxidative stress. Although our data confirm CUR’s specific modulation of Notch1-mediated apoptosis and ROS scavenging, future studies should explore whether CUR’s pleiotropic effects extend to these novel death pathways—particularly given its known metal-chelating properties (e.g., iron and copper) and ability to restore cytoskeletal integrity. Such investigations could further elucidate the comprehensive cardioprotective mechanisms of CUR in diabetes.

We did have some limitations. It has been proposed that the generation of reactive oxygen species and the resulting oxidative stress could potentially play a role in cardioprotective mechanisms associated with CUR; However, the precise pathways involved remain to be elucidated. Initially, only western blot assays were employed in the examination of the signaling pathways to assess the expression levels of N1ICD and Hes1 proteins. And we have not performed experiments to determine the mRNA level of N1ICD. Besides, there is a lack of in vivo experiments to justify the entire study.

In summary, we demonstrated that activation of the Notch1 signaling pathway protects cardiomyocytes by enhancing cell viability, reducing ROS formation, and inhibiting apoptosis. In addition, the most pronounced DAPT-sensitive effects included a significant reduction in cardiomyocyte survival and an increase in apoptosis, both of which led to the abolition of most cardioprotective effects. However, the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), NADPH, and glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) helped mitigate the damage to cardiomyocytes caused by DAPT. The findings show that pretreating with CUR can enhance the levels of Notch1 and Hes1 proteins, which implies that CUR has a protective role against damage induced by high glucose (HG).

Data availability

All datasets are included as Supplementary Table S1.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

A one-way analysis of variance

- CCK:

-

Cell Counting Kit

- CUR:

-

Curcumin

- DCM:

-

Diabetic cardiomyopathy

- DMEM:

-

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

- GSH-Px:

-

Glutathione peroxidase

- HG:

-

High glucose

- HO-1:

-

Heme oxygenase-1

- H:

-

Hour

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- NADPH:

-

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- NG:

-

Normal glucose

- N1ICD:

-

Notch 1 intracellular domain

- Notch1:

-

Notch homolog 1, translocation-associated (Drosophila)

- NRF2:

-

Nuclear factor-erythroid-2-related factor 2

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PI:

-

Propidium iodide

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SOD:

-

Superoxide dismutase

- TNF-α:

-

Tumor necrosis factor -alpha

References

Dillmann, W. H. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 124 (8), 1160–1162 (2019).

Wu, X., Zhou, X. L., Lai, S. Q., Liu, J. C. & Qi, J. W. Curcumin activates Nrf2/HO-1 signaling to relieve diabetic cardiomyopathy injury by reducing ROS in vitro and in vivo. FASEB J. 36 (9), e22505 (2022).

Rosini, E. & Pollegioni, L. Reactive oxygen species as a double-edged sword: the role of oxidative enzymes in antitumor therapy. Biofactors 48 (2), 384–399 (2022).

Kotha, R. R. & Luthria, D. L. Curcumin: biological, pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and analytical aspects. Molecules 24 (16), 2930 (2019).

Wei, Z., Shaohuan, Q., Pinfang, K. & Chao, S. Curcumin Attenuates Ferroptosis-Induced myocardial injury in diabetic cardiomyopathy through the Nrf2 pathway. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2022, 3159717 (2022).

Rajabi, S., Darroudi, M., Naseri, K., Farkhondeh, T. & Samarghandian, S. Protective effects of Curcumin and its analogues via the Nrf2 pathway in metabolic syndrome. Curr. Med. Chem. 31 (25), 3966–3976 (2024).

Edelmann, J. NOTCH1 signalling: A key pathway for the development of high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Front. Oncol. 12, 1019730 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. Icariin improves osteoporosis, inhibits the expression of PPARγ, C/EBPα, FABP4 mRNA, N1ICD and jagged1 proteins, and increases Notch2 mRNA in ovariectomized rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 13 (4), 1360–1368 (2017).

Townson, J. M., Gomez-Lamarca, M. J., Santa Cruz Mateos, C. & Bray, S. J. OptIC-Notch reveals mechanism that regulates receptor interactions with CSL. Development 150 (11), dev201785 (2023).

Luo, X., Zhang, L., Han, G. D., Lu, P. & Zhang, Y. MDM2 Inhibition improves cisplatin-induced renal injury in mice via inactivation of Notch/hes1 signaling pathway. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 40 (2), 369–379 (2021).

Miao, L. et al. The Spatiotemporal expression of Notch1 and numb and their functional interaction during cardiac morphogenesis. Cells 10 (9), 2192 (2021).

Zhou, X. L. et al. Notch1-Nrf2 signaling crosstalk provides myocardial protection by reducing ROS formation. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 98 (2), 106–111 (2020).

Zhang, W. et al. EGFL7 secreted by human bone mesenchymal stem cells promotes osteoblast differentiation partly via downregulation of Notch1-Hes1 signaling pathway. Stem Cell. Rev. Rep. 19 (4), 968–982 (2023).

Duan, J., Yang, M., Liu, Y., Xiao, S. & Zhang, X. Curcumin protects islet beta cells from streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus injury via its antioxidative effects. Endokrynol Pol. 73 (6), 942–946 (2022).

Yu, W. et al. Curcumin suppresses doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte pyroptosis via a PI3K/Akt/mTOR-dependent manner. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 10 (4), 752–769 (2020).

Liu, X. et al. Curcumin alleviated lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury via regulating the Nrf2-ARE and NF-κB signaling pathways in ducks. J. Sci. Food Agric. 102 (14), 6603–6611 (2022).

Rahnavard, M. et al. Curcumin ameliorated myocardial infarction by Inhibition of cardiotoxicity in the rat model. J. Cell. Biochem. 120 (7), 11965–11972 (2019).

Cox, F. F. et al. Protective Effects of Curcumin in Cardiovascular Diseases-Impact on Oxidative Stress and Mitochondria. Cells ;11(3):342. (2022).

Jo, Y. W. et al. Notch1 and Notch2 signaling exclusively but cooperatively maintain fetal myogenic progenitors. Stem Cells. 40 (11), 1031–1042 (2022).

Lu, Y. et al. Patchouli alcohol protects against myocardial ischaemia-reperfusion injury by regulating the Notch1/Hes1 pathway. Pharm. Biol. 60 (1), 949–957 (2022).

Shabab, S., Mahmoudabady, M., Gholamnezhad, Z., Fouladi, M. & Asghari, A. A. Diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats was attenuated by endurance exercise through the Inhibition of inflammation and apoptosis. Heliyon 10 (1), e23427 (2023).

Dai, C. et al. Curcumin attenuates Colistin-Induced neurotoxicity in N2a cells via Anti-inflammatory activity, suppression of oxidative stress, and apoptosis. Mol. Neurobiol. 55 (1), 421–434 (2018).

Garciaz, S., Miller, T., Collette, Y. & Vey, N. Targeting regulated cell death pathways in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Drug Resist. 6 (1), 151–168 (2023).

Liu, H. Expression and potential immune involvement of Cuproptosis in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma. Cancer Genet. 274–275, 21–25 (2023).

Liu, H. & Tang, T. Pan-cancer genetic analysis of disulfidptosis-related gene set. Cancer Genet. 278–279, 91–103 (2023).

Funding

All research costs were supplied by Nanjing Medical University Science and Technology Development Fund (No. NMUB20220079).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. researched, analyzed the data and reviewed the article. X.W. and Z.Y. Q. wrote and edited the article. X.W. analyzed the data, prepared figures and/or tables, authored or reviewed drafts of the paper, approved the final draft, performed statistical analysis. P.Y. L. contributed initial discussion of the project and reviewed the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study was approved (NMUC20240358) by Laboratory Animal Ethics Committee of Nanjing First Hospital.

Research involving human and\or animal participants

This study is performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All methods are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, X., Qu, Z. & Liu, P. Curcumin mitigates high glucose-induced cardiac oxidative stress via Notch1 pathway activation. Sci Rep 15, 23660 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09105-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09105-9