Abstract

Accurately characterizing \(\hbox {CO}_2\) sequestration and migration post-injection is crucial to the success of carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects. Time-lapse seismic monitoring technique is an effective tool; however, it can only reveal changes in elastic properties such as compressional wave velocity (\(V_{\text {p}}\)) and quality factor (\(Q_{\text {p}}\)). In contrast, reservoir simulation enables detailed tracking of fluid movement within the reservoir, allowing for precise simulation of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation. Thus, to enable a more accurate characterization of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration, we develop an integrated workflow that closes the loop between reservoir saturation data and time-lapse seismic data, which operate at different resolution scales. First, we build a realistic geological model for \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage based on the field information from typical saline aquifers in the Pearl River Mouth Basin (PRMB). Then, using rock physics theory, we establish relationships between \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation and seismic properties (\(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\)) to construct seismic models. Subsequently, we employ time-lapse seismic techniques to analyze the effects of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation changes on seismic data and quantitatively estimate these effects using the spectral-ratio method. Finally, the workflow developed in this study efficiently addresses challenges associated with varying observational scales and interdisciplinary research. It offers a valuable approach for predicting and detecting early \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage based on known reservoir properties. This dataset will be available as an open-access resource, providing a valuable tool for testing and advancing research in the CCS field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology is an effective method for reducing \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emissions and mitigating the effects of global warming1. In general, suitable formations for \(\hbox {CO}_2\) geological storage (CGS) are located at depths greater than 800 m, with adequate reservoir porosity and permeability, impermeable caprocks to prevent upward migration of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plumes, and suitable formation fluid and mineral compositions to enhance the safety of long-term storage2,3 . Currently, saline aquifers are widely acknowledged as suitable sites for CGS due to their significant storage capacity4,5. The practice of CGS in saline aquifers has been extensively researched6,7. Monitoring \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration and distribution safely and reliably during and after injection is crucial for successful sequestration in saline aquifers8,9. The characteristics of saline aquifers, such as permeability, porosity, pressure, temperature, and caprock integrity, significantly influence storage efficiency, \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration, safety, and stability. A thorough analysis of these aquifer properties is essential for understanding and predicting the post-injection status of \(\hbox {CO}_2\), thereby facilitating the development of safe and efficient \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection and sequestration strategies10.

Furthermore, subsurface \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection entails potential leakage risks, necessitating comprehensive monitoring to assess and ensure the long-term integrity and efficacy of saline aquifers for CGS11. Among various monitoring methods, time-lapse seismic monitoring method provides a reliable approach for large-scale \(\hbox {CO}_2\) monitoring12,13. Moreover, by analyzing seismic responses such as amplitude reduction and phase distortion, it is possible to infer the location of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume. This is because seismic techniques, such as surface seismic acquisition or vertical seismic profiling (VSP), offer extensive spatial coverage and deep penetration capabilities. In traditional oil and gas fields, the time-lapse seismic monitoring method has been proven effective and feasible by numerous research institutions14,15. Currently, time-lapse seismic monitoring has been employed at pilot \(\hbox {CO}_2\) sequestration sites worldwide, including projects in Norway (Sleipner, Snøhvit, and the Northern Lights)13,16,17, the USA (Frio and Cranfield)18,19, Canada (Weyburn, CaMI, and Quest)20,21,22, Algeria (In Salah, e.g.23, Australia (Otway)24, Japan (Tomakomai and Nagaoka)25,26, and Germany (Ketzin)27. These examples highlight the effectiveness and widespread application of time-lapse seismic imaging for monitoring \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage across diverse locations, both offshore and onshore.

Unfortunately, although time-lapse seismic monitoring can provide elastic properties, such as reflectivity, impedance, and velocity, as well as anelastic properties such as seismic attenuation, it cannot directly and precisely quantify the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume saturation distribution. In contrast, reservoir simulation technology can quantitatively predict \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume saturation with high resolution28,29,30. It also enables the estimation of fluid displacement effects, identification of migrating fluid fronts, and prediction of future fluid distributions31,32. However, reservoir simulation techniques cannot directly link \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation to seismic (elastic and anelastic) properties. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a bridge connecting \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation and seismic properties to facilitate the implementation of seismic monitoring techniques.

To more accurately monitor the migration characteristics of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume using time-lapse seismic monitoring technique, some researchers utilize rock physics as a bridge connecting \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation and seismic properties33,34,35. When \(\hbox {CO}_2\) is injected into subsurface formations, it results in both decreased compressional wave velocity (\(V_{\text {p}}\), an elastic property) and increased seismic attenuation (\(Q_{\text {p}}\), an anelastic property), thereby affecting seismic wave propagation characteristics12,36 found that seismic attenuation immediately increases and reaches a peak value even at small \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation, suggesting that attenuation measurements could be a suitable tool for monitoring \(\hbox {CO}_2\) movement and saturation variations. Additionally, minor fluctuations in \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation, as emphasized by37, can significantly influence seismic wave attenuation properties, thereby affecting both amplitude and phase of seismic data. Thus, \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) can effectively indicate \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation. Rock physics serves as an essential tool to establish quantitative relationships between seismic properties derived from seismic data (e.g., \(V_{\text {p}}\), \(Q_{\text {p}}\)) and \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation. Although rock physics can establish the relationship between \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation and \(V_{\text {p}}\), \(Q_{\text {p}}\) to predict \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume saturation distribution, it still faces the challenge of scale differences. Similarly, reservoir simulation data and time-lapse seismic data are acquired at different resolution scales posing a critical challenges for CGS projects. To overcome this challenge, upscaling is very important, because actual reservoirs in \(\hbox {CO}_2\) sequestration projects are often large-scale, requiring more accurate simulates of dynamic \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume migration. Upscaling technology converts rock properties, such as porosity and permeability, from a fine-scale grid to a coarse-scale grid, ensuring the two scales remain equivalent38. This methodology has been successfully applied in numerous \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage studies39,40,41. Therefore, we apply the upscaling technology in \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage simulations to enhance our understanding of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration.

Several integrated workflows have been developed to incorporate reservoir, rock physics, and seismic data, although some limitations remain. For example, 42developed a workflow for \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage in coal beds, which also enhanced coal-bed methane production. Similarly, 43established a workflow for enhanced oil recovery (EOR), integrating simulation-to-seismic methods with seismic reservoir characterization. Furthermore,24proposed a workflow utilizing elastic full waveform inversion (FWI) to detect and quantify time-lapse anomalies in P-wave velocity. Although these workflows have been applied in various domains, relatively few studies have integrated workflows specifically for saline aquifers44,45, and even fewer have addressed the impact of attenuation following \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection. To further quantify attenuation effects caused by \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, we apply the spectral ratio method in \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage monitoring. By comparing the amplitude spectra of baseline and monitor data, we can evaluate attenuation changes resulting from \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection. However, to measure the attenuation effects of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) accurately in seismic imaging, the traditional spectral ratio method in the data domain has become insufficient. Therefore, this new workflow transforms the spectral ratio method from the data domain (time) to the imaging domain ( depth), and further extending from three-dimensional (3D) into four-dimensional (4D) seismic imaging domain to better quantify the seismic response characteristics induced by \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection.

The goal of this work is to propose a new workflow. Compared to previously developed workflows, we incorporate attenuation, rock physics, and spectral ratio methods to study \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume migration. To achieve this, we develop a highly realistic model that accurately simulates and monitors the behavior of injected \(\hbox {CO}_2\) over time, focusing on a typical saline aquifer in the Pearl River Mouth Basin (PRMB), located in the northern South China Sea. This project represents an offshore \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage scenario, making it particularly significant for evaluating the effectiveness of time-lapse seismic monitoring in marine environments. The basin contains thick sedimentary layers with high-porosity and high-permeability reservoirs, which could provide sufficient capacity for storing \(\hbox {CO}_2\) emitted from the large point sources along the coast. To ensure our study accurately reflects realistic \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume migration, we synthesize reservoir and seismic related properties based on the field information, including reservoir characteristics and well logs. Subsequently, we establish the relationship between \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation and seismic properties (\(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\)) using rock physics theory, thereby deriving corresponding \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) models. To address scale differences between reservoir simulation and seismic modelling, we employ upscaling techniques for \(\hbox {CO}_2\) dynamic simulation. Finally, we generate time-lapse seismic data based on the calculated \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) using the viscoacoustic wave equation. We then apply reverse time migration (RTM) and the spectral ratio method in the 4D imaging domain to analyze the attenuation effects caused by \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection within the reservoir. We integrate reservoir modelling, rock physics modelling, and seismic modelling into a tailored workflow for aquifer reservoirs in CCS, aiming to better understand how saline aquifers influence \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration and how time-lapse seismic properties respond to \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume distribution. Additionally, we provide a realistic synthetic model and dataset designed to support future numerical studies in CCS projects. While open access to CCS projects is common in Europe and the United States, it remains rare in Asia. Therefore, this study offers a realistic dataset that will be available as open-access, providing valuable support for testing and advancing CCS research.

Workflow

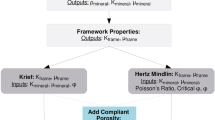

In this section, we design a new tailored workflow that integrates reservoir modelling, rock physics modelling, and seismic modelling specifically for aquifer reservoirs in CCS. This approach aims to enhance our understanding of how saline aquifers affect \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration and how time-lapse seismic properties respond to the attenuation effects caused by the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume. The workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1 and consists of three steps: Step (1) involves conducting fluid dynamic simulations using reservoir modelling and upscaling techniques based on the established porosity and permeability models to obtain \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation at different times. In Step (2), we establish the relationships between \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation and seismic properties (\(V_p\), \(Q_p\)), and generate corresponding \(V_p\) and \(Q_p\) models to obtain time-lapse seismic data. Step (3) uses the time-lapse seismic data obtained in step (2) for RTM imaging to analyze seismic responses resulting from \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection. This step also compares monitoring data with baseline data and quantifies attenuation during and after injection using the spectral ratio method.

Relationship between porosity and depth in the PRMB (revised from48).

Step 1: reservoir modelling

In this section, we establish a realistic CGS model based on the PRMB and simulate \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation within the reservoir more accurately by utilizing field data. We use Eclipse 300 and upscaling techniques to predict \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume migration (Fig. 1, step 1).

Geological model design

The establishment of reservoir simulation models forms the basis for quantifying changes in reservoir properties under varying \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturations46. In this study, we utilize the geological characteristics of typical saline aquifers in the PRMB, located in the Northern South China Sea, for dynamic CGS simulations. We construct porosity and permeability models based on the characteristics of these saline aquifers, with model dimensions of 18 km (x) \(\times\) 4 km (y) \(\times\) 3 km (z). Figure 2 shows its two-dimensional profile, which is extracted at y = 2 km. In the process of model building, the reservoir is characterized by an anticline structure, facilitating the upward migration and storage of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) over time. Based on seismic lines provided from this basin, we include two major fault zones into our models, each with a dip angle of \(55^{\circ }\). The vertical offset between fault planes in the upper and lower layers is 40 m for the left fault and 30 m for the right fault, with the injection well positioned to the right of the 30-meter fault (30 m-distance between upper and lower layers). Faulting is a common feature in CGS projects, such as the Northern Lights47. In Fig. 2(a), we clearly label the location of the injection well, injection point, and along with their permeabilities based on the information presented in Fig. 2. To accurately model porosity within the provided range, we refer to the findings of48. Figure 3 shows that their porosity values decreases with depth (black curve). Similarly, our porosity data align well with their findings, ranging between 10% and 50% (red curve).

The \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation simulation adopts a single-well injection strategy starting in 2024, with injection lasting for 25 years, followed by 75 years of monitoring through shut-in wells. The injection occurs in two layers: Formation A (Fm. A) and Formation B (Fm. B), which are potential reservoirs in the area—one shallow and one deep. Both Fm. A and Fm. B consist of sandstone with high porosity and permeability, and each is overlain by shale layers serving as sealing layers. In the shallow reservoir, a 20-meter-thick layer of mudstone extends into the sandstone, significantly enhancing the sealing effect and reducing the risk of leakage. Throughout the simulation, the annual volume of injected \(\hbox {CO}_2\) is 1 Mt, with an injection rate of 1,394,520 \(\hbox {sm}^{3}/\hbox {day}\). The model also highlights that under normal pressure conditions, the salinity and density of the saltwater are 35 g/L and 1.03 \(\hbox {g/cm}^{3}\), respectively. Table 1 presents the key characteristics and parameters of the upscaled reservoirs and caprocks in Fm. A and Fm. B, which support dynamic simulation of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume behavior. Additionally, Table 1 presents a temperature gradient of \(3.4^{\circ }\hbox {C}/100\,\hbox {m}\), with seawater temperature maintained at \(20^{\circ }\hbox {C}\). The temperatures of Fm. A and Fm. B are computed by multiplying the temperature gradient by their respective depths and subsequently adding the seawater temperature.

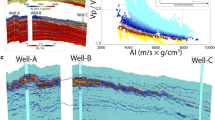

In this area, we observe alternating layers of sand and mud, as determined from the interpreted log data acquired from the PRMB. The log curves plotted from these data are shown in Fig. 4(a). Subsequently, we extract the velocity and density values for all model layers, as shown in Table 2. Figure 4(b) displays the compilation of reservoir layers (Fm. A and Fm. B) and the distinct limestone layers derived from the well logs. Table 2 presents the velocity selection results for all layers, showing an overall trend of increasing velocity and density with increasing reservoir depth. Note that the velocity selection is conducted based on the well logging data (shown in Fig. 4(b)). Figure 4(b) denotes the selection information for Fm. A and Fm. B, with the information for Fm. A shown above and the information for Fm. B shown below. These two sedimentary formations serve as the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection sites in the subsequent reservoir simulation section. Additionally, we observe that the sandstone velocity in Fm. A is higher than that of the adjacent mudstone layers. This occurs because Fm. A sandstone has high porosity and experiences greater compaction compared to mudstone, potentially resulting in higher velocity. Moreover, we also observe that the sandstone velocity in Fm. A is higher than that of the overlying and underlying layers, which may be attributed to its higher porosity and permeability compared to typical cases, as well as the unique geological structure of its caprock, such as a limestone reservoir. Due to their characteristics, Fm. A and Fm. B are well suited for CCS research. Based on the velocity and density values picked from the log data, we construct the velocity model and density model, as shown in Fig. 5. Subsequently, these models are used to perform reservoir simulation and seismic modelling.

Multiphase flow simulation and model upscaling

By considering a \(\hbox {CO}_2\)-water flow scenario in the absence of gravity, we simplify the model by neglecting capillary pressure and fluid compressibility. The mass conservation equation is expressed as follows:

where \(\phi\) is the porosity, t is time, and \(S_{j}\) is the saturation of the displacing fluid phase j (water or \(\hbox {CO}_2\)), \({\textbf{u}}_{j}\) is the viscosity of phase j. Note that for the \(\hbox {CO}_2\)-water system considered here, \(S_{w}+S_{g}=1\). Darcy’s law can be expressed as:

where \(\lambda _j = \frac{k_{rj}}{\mu _j}\) is the mobility of phase \(S_{j}\), \({k_{rj}}\) is the relative permeability to phase \(S_{j}\), \({\mu _j}\) is the viscosity of phase \(S_{j}\), \({\textbf{k}}\) is the absolute permeability tensor, \({\varvec{p}}_{j}\) is the pressure of phase \(S_{j}\). In the presence of capillary pressure effects, the pressures of the nonwetting (gas) phase and the wetting (water) phase are related by:

where \(P_c\) is capillary pressure. According to the Eqs. (2) and (3), Eq. (1) can be expressed as:

However, solving two-phase flow equations based on fine-scale model is very time consuming; hence, upscaling techniques are usually applied in practice to reduce the reservoir model dimension. In this study, we use a simple grid-based sampling approach to obtain the coarse-scale porosity and permeability distributions. Note that more advanced upscaling techniques can also be applied for more accurate flow simulation. For example, the flow-based upscaling approach proposed by40,49,50, and the machine-leaning-assisted upscaling method recently developed for \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage simulation51. The fine-scale transport model is discretized into a grid of 1801 (x) \(\times\) 301 (z) with a spatial interval of 10 m, as shown in Fig. 6(a). Figure 6(b) shows the coarsened Fm. A as a grid of 60 (x) \(\times\) 50 (z), corresponding to the orange dashed box in Fig. 6(a). Similarly, Fig. 6(c) presents the coarsened Fm. B as a grid of 60 (x) \(\times\) 40 (z), corresponding to the blue dashed box in Fig. 6(a). After coarsening, the grid spacing is set to 300 m (x) \(\times\) 10 m (z). Notice that, in our model here, the z-axis is not coarsened.

Fluid model

In saline aquifers, brine acts as the wetting phase, whereas \(\hbox {CO}_2\) serves as the non-wetting phase2. This study utilizes Eclipse 300 (E300), a reservoir simulation software developed by Schlumberger, to simulate \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume injection dynamics by upscaling models of Fm. A and Fm. B. To simulate the geological conditions of saline aquifers, the E300 \(\hbox {CO}_2\)STORE option enables the modelling of three phases: the \(\hbox {CO}_2\)-rich phase, the \(\hbox {H}_2\)O-rich phase, and the solid phase. We use the parameters provide in Table 1 for our simulation. At the grid block scale, interactions between the \(\hbox {CO}_2\)-rich and \(\hbox {H}_2\)O-rich phases are depicted by capillary pressure and relative permeability functions52. These functions depend on the fluid saturation within the porous media or the grid block53,54,55. Figure 7 shows the water saturation function (WSF) and gas saturation function (GSF), which are derived from E300. It also illustrates the free \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation (\(S_g=0.7\)) and connate water (\(S_w=0.3\)) in Fm. A and Fm. B, representing extreme scenarios after injection. In Fig. 7, water saturation (\(S_w\)) decreases as \(\hbox {CO}_2\) displaces water in the reservoir. Capillary pressure (\(P_c\)) increases as \(S_w\) decreases, reflecting the growing pressure difference between the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) and water phases (shown by the pink dashed line in Fig. 7). Relative permeabilities (\(K_r\) \(\hbox {CO}_2\) and \(K_r\) water) change as \(S_w\) decreases: \(K_r\) \(\hbox {CO}_2\) increases, enhancing \(\hbox {CO}_2\) mobility (represented by the red solid line in Fig. 7), while \(K_r\) water decreases, reducing water flow capacity (indicated by the green dashed line in Fig. 7). The data originate from the Schlumberger case study56, in particular, the gas-water drainage capillary pressure (\(P_c\)). Moreover, capillary and viscous forces play crucial roles in storage simulations by hindering the upward migration of \(\hbox {CO}_2\)57. Conversely, buoyancy, influenced by density differences between \(\hbox {CO}_2\) and saltwater, accelerates \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage. Balancing buoyancy, viscosity, and capillary forces is thus vital for evaluating the long-term safety of supercritical \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage.

Initial and boundary conditions

When injecting \(\hbox {CO}_2\) into subsurface formations, specific temperature (\(31.1^{\circ }\hbox {C}\)) and pressure (73.82 bar) conditions are required to maintain a supercritical state8,28. The depth of the target \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection layer must exceed 800 m to ensure the injected \(\hbox {CO}_2\) remains in a dry gas state and exists in a supercritical phase. The \(\hbox {CO}_2\)-\(\hbox {H}_2\)O system in E300 operates within a temperature range of 12 to \(100 ^{\circ }\hbox {C}\) and up to 600 bars under typical \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage conditions58. For the simulation, we assign gas diffusion coefficients of 0.001 to the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) components. Additionally, considering the extensive horizontal dimension of our model, we assume the presence of an impermeable boundary. The initial fluid models in the water phase are categorized into \(\hbox {H}_2\)O, NaCl, and \(\hbox {CaCl}_2\)59. In our simulation, we focus on monitoring \(\hbox {CO}_2\) dynamics over a period of up to 100 years. Although chemical reaction simulations are mainly relevant for long-term geological \(\hbox {CO}_2\) sequestration investigations59, within the timeframe considered in this study, we can ignore the impact of chemical reactions.

Step 2: rock physics modelling

Theoretically, the seismic properties (such as seismic velocity and attenuation) of subsurface media will change after the injection of \(\hbox {CO}_2\). In this study, we use rock physics to establish the P-wave velocity and attenuation (i.e., quality factor), based on the simulated \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation. According to the relation between the compressional modules \(M_0\) and the bulk density \(\rho\) , P-wave velocity \(V_{\text {p}}\) can be given by:

where \({M_0}\) is calculated using the fluid substitution equation60 and the \(V_{\text {p}}\)-only approximation61:

where \(M_{mp}\) is the mineral-phase’s compression modulus and \(M_{dry}\) is the compressional modulus of the rock’s dry frame. \(\phi\) is the total porosity, and \(\kappa _{f}\) is the effective fluid bulk modulus, which is calculated from the harmonic average of water and \(\hbox {CO}_2\).

(a) Coarse-scale \(V_{\text {p}}\) model prior to \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection in Fm. A; (b) coarse-scale \(V_{\text {p}}\) during the 25-year injection period; (c) coarse-scale \(V_{\text {p}}\) monitoring of the reservoir after 100 years of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection stops; (d) coarse-scale \(Q_{\text {p}}\) model prior to \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection; (e) 1/\(Q_{\text {p}}\) during the 25-year injection period at coarse scale; (f) coarse-scale 1/\(Q_{\text {p}}\) monitoring of the reservoir after 100 years of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection stops.

(a) Coarse-scale \(V_{\text {p}}\) model prior to \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection in Fm. B; (b) Coarse-scale \(V_{\text {p}}\) during the 25-year injection period; (c) Coarse-scale \(V_{\text {p}}\) monitoring of the reservoir after 100 years of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection stops; (d) Coarse-scale \(Q_{\text {p}}\) model prior to \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection; (e) 1/\(Q_{\text {p}}\) during the 25-year injection period at coarse scale; (f) Coarse-scale 1/\(Q_{\text {p}}\) monitoring of the reservoir after 100 years of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection stops.

Then, we calculate the P-wave quality factor (\(Q_{\text {p}}\)) that is used to quantify the attenuation. We can establish the relationship between \(Q_{\text {p}}\) and the velocity-frequency dispersion62, using the standard linear solid (SLS) theory. Based on the previous studies63,64, the maximum inverse quality factor \(Q_{p_{\text{ max } }}^{-1}\) can be expressed as:

where \(M_{\infty }\) is the compression modulus at an extremely high frequency. When \(M_{0}\) represents the low-frequency compressional modules and loading is slow, it can be used in Eq. (7). Under these conditions, the pore pressure oscillations in fully liquid-saturated patch and nearby partially saturated regions containing both water and \(\hbox {CO}_2\) reach equilibrium.

On the contrary, when the frequency is high and the loading is fast, we should use the patchy saturation equation65, because the water saturated patch and the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) patches are not equilibrate. The \(M_{\infty }\) can be expressed as:

where

where \(S_\zeta\) is the saturation of water or \(\hbox {CO}_2\), depending on the fluid phase. \(M_\zeta\) denotes the compressional modulus of the wet rock, with (\(\zeta =w\)) for water and (\(\zeta =g\)) for \(\hbox {CO}_2\), and \(\kappa _{\zeta }\) is the bulk modulus of water or \(\hbox {CO}_2\).

Step 3: time-lapse Seismic technique

Seismic modelling

In seismic modelling, the wavefield propagation can be simulated using known elastic properties, such as velocity and density, which govern seismic wave propagation in subsurface media. Given known velocity while assuming constant density, the acoustic wave equation can be expressed as:

where \(V_{\text {p}}\) is the P-wave velocity. However, the waves are attenuated when travel through the media due to the presence of \(\hbox {CO}_2\). Therefore, the conventional acoustic equation shown in Eq. (11) cannot meet the requirement. Incorporating attenuation in seismic modelling is essential to accurately simulate the wave propagation through \(\hbox {CO}_2\) zone. To accurately describe wave propagation properties in attenuating media, a series of attenuation theories have been developed over the years64,66,67,68,69,70. One widely used theory is SLS attenuation theory71. Building on the SLS theory, many viscoacoustic wave equations have been derived to simulate the characteristics of seismic wave propagation. In this study, we employ the viscoacoustic wave equation with a single-SLS element to perform forward modelling, which can be expressed as:

where r is the memory variable. The coefficients \({\tau _\varepsilon }\) and \({\tau _\sigma }\) are the strain relaxation time and the stress relaxation, respectively, shown as follows:

where \(Q_{p}\) is the quality factor that characterizes the strength of attenuation, \(\omega _{0}\) is the reference frequency. In Eq. (12), when \(Q_{p} \rightarrow \infty\) , Eq. (12) becomes acoustic wave equation.

To perform forward modelling of wave propagation in attenuating media associated with the injection of \(\hbox {CO}_2\), it is necessary to numerically solve Eqs. (12) and (13). Here, we adopt an eight-order finite difference method, whose discretization can be expressed as:

where \(c_m\) are the finite-difference coefficients of the second derivative, and i, j, k denotes the discretization in \(x-\), \(y-\), and \(z-\)direction, respectively. The superscript n denote time variable. Through time-lapse seismic modelling, we can observe the seismic data changes caused by the injection of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) over time. This result can be verified in the subsection time-lapse seismic imaging in fine-scale.

Seismic imaging

To image the geologic structure in subsurface media, reverse time migration (RTM) is one of effective seismic imaging techniques. The implementation of RTM mainly can be summed up in three steps72 as follows: first, computing the source wavefield by forward propagation based on equation (13). Second, backward propagating the receiver wavefield using recorded seismic waveforms as the boundary condition. Finally, applying the source-normalized zero-lag cross-correlation imaging condition to obtain imaging results. In this study, the source normalized zero-lag correction imaging condition used to implement RTM, which can be expressed as:

where \(S \left( {\textbf{x}},t \right)\) and \(R \left( {\textbf{x}},t \right)\) denote source wavefield and receiver wavefield, respectively, and \(I\left( {\textbf{x}} \right)\) represents the imaging results. The denominator of Eq. (20) is the cross-correlation of source wavefield, which is used as an illumination for enhancing the imaging quality. T is the propagation length, and dt is the time step. Based on the RTM technique, when we monitor the seismic imaging over time, the time-lapse changes can be quantified.

Spectral ratio method

To examine the time-lapse seismic response to the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume distribution more accurately, we note that \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection increases attenuation within the reservoir. This leads to significant reductions in wave amplitude and resolution, as well as phase distortions, potentially resulting in the mis-interpretation of time-lapse seismic data. A common method to quantify attenuation effects is to measure the spectral changes in seismic data. The spectral ratio method, first proposed by73, uses spectral ratios of two body waves to eliminate source effect and the effect of wave front divergence.74 evaluated the spectral ratio method alongside nine other Q-estimation techniques, highlighting its ability to quantify cumulative attenuation along a propagation path by comparing the relative loss of high- and low-frequency energy in recorded waves. Subsequently,75 established the central frequency method. Both methods quantify the attenuation effects on seismic data through spectral analysis. Among these two methods, the spectral ratio method can better handle the noisy data. According to the spectral ratio method, after calculating two amplitude spectra in the frequency domain, the logarithm of spectra ratio ideally can be given as:

where \(R_{a}(f)\) and \(R_{0}(f)\) denote the amplitude spectra in attenuated and non-attenuated media, respectively. \(G_{0}\) is the intercept term, which is usually a constant and is not related to the frequency band. \(G_{0}\) typically includes geometric spreading, instrument response, source /receiver inconsistency, radiation pattern, and reflection /transmission coefficients. \(\eta\) represents the seismic accumulative attenuation effects, and is proportional to the quality factor, shown as below:

To measure the attenuation effects from time-lapse seismic imaging, we need to convert the equation from frequencies-domain in time to image-domain in depth. In this study, we adopt the spectral ratio method used by69,70 to compute the ratio between monitoring spectra \(R_{2}(k)\) and base spectra \(R_{1}(k)\). \(R_{2}(k)\) and \(R_{1}(k)\) represent the spectra after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection and the spectra before \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, respectively. Similar to Eq. (21), the logarithm of spectra ratio of time-lapse seismic signals can be expressed as:

where, k is the local wavenumber of a migrated event and \(\eta\) is calculated as:

where the integration proceeds along the wave path dl, and quantifies the accumulated attenuation on the time-lapse seismic images. Therefore, it can be well used to quantify the attenuation caused by the injection of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) within in a given monitoring time range.

Results

Reservoir simulation results

Figure 8 illustrates the migration and distribution of supercritical \(\hbox {CO}_2\) following injection into a single well, along with plume simulations. These figures depict the changes in \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation over 25 years of injection and subsequent monitoring over 100 years for the coarsened Fm. A model, as shown in Fig. 8(a-b). Both Fm. B and Fm. A exhibit similar trends, with areas of high saturation gradually ascending over time, as shown in Fig. 8(c-d). Because of the density differences between \(\hbox {CO}_2\) and brine, the low-viscosity \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migrates toward the top of the geological structure75. Despite the expansion of the plume, it becomes apparent that the concentration decreases as \(\hbox {CO}_2\) dissolves into the reservoir water over time. Figure 8 shows that the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation for both Fm. A and Fm. B reaches a maximum of about 0.3 after 25 years. However, the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation decreases after 100 years compared to the 25-year value, with the minimum \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation at approximately 0.1.

Two-dimensional fine-scale seismic models: (a) and (c) show the \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) models 100-year after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection ceases in Fm. A, respectively. (b) and (d) present the \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) models 100-year after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection ceases in Fm. B. Arrows indicate the injection points for \(\hbox {CO}_2\) during the injection period.

Comparison between baseline data and monitor data Fm. A and Fm. B 100 years after the cessation of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection. (a) Fm. A and (b) Fm. B differences between baseline and monitor data. (c) Fm. A and (d) Fm. B trace comparison between baseline and monitor data. The baseline data represents the state without \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection (Fig. 14(a), while the monitor data is shown in Fig. 14(b) and Fig. 14(c), respectively. The trace is extracted from the same location at a distance of \(x=11.5\) km in the baseline data, as well as the 100-year monitoring data for Fm. A and Fm. B. The black box represents the attenuation changes occurring in the 100 years after the cessation of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection.

Comparison of single-trace extracted from Fig. 16: (a) the Fm. A and (b) the Fm. B. This rectangular box represents the attenuation effects generated during the 25th year of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection and the 100th year after injection cessation.

The RTM results illustrating the effects of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection on shallow and deep formations are as follows: (a) and (b) represent the differences between the 25th year during \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection and the 100th year after injection cessation for shallow Fm. A’s monitor seismic data and baseline seismic data, respectively. Similarly, (c) and (d) show the differences for deep Fm. B. The selected rectangular box indicates the area used for spectrum calculation to quantify the attenuation effects caused by \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection using the spectrum ratio method.

The wavenumber spectrum and spectral ratio results for regions I and II in Fm. A and region III in Fm. B are shown as follows: In Fm. A, region I shows the attenuation effects in (a) the wavenumber spectrum and (b) the spectral ratio, while region II shows them in (c) the wavenumber spectrum and (d) the spectral ratio. In Fm. B, region III shows the attenuation effects in (e) the wavenumber spectrum and (f) the spectral ratio. Regions I–III originate from Fig. 18.

The slope map of Fig. 16 calculated using the wavenumber domain spectral ratio method. Here, the \(Q_{\text {p}}\) models have been overlaid on the slope map background. (a) Slope of Fm. A at the 25th year during \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection period, (b) slope of Fm. A at the 100th year after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection cessation. Similarly, (c) slope of Fm. B at the 25th year during \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection period, (d) slope of Fm. B at the 100th year after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection cessation.

(a) The two-dimensional RTM imaging results from a fine-scale seismic model, 100 years after the leakage occurred. (b) The RTM results showing the difference between the 100-year monitoring data and the baseline data for Fm. A with leakage. The attenuation effect in region IV of Fm. A appears through (c) the wavenumber spectrum and (d) the spectral ratio. Similarly, the attenuation effect in region II shows through (e) the wavenumber spectrum and (f) the spectral ratio. Regions II and IV from Fig. 18(b) serve as references for the 100th year without leakage (the red curves in Fig. 22), while the black curves represent regions II and IV from Fig. 22(b) under leakage conditions at the 100th year. The blue curves show the baseline condition without \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection.

Furthermore, our observations reveal that Fm. B exhibits a broader range of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation plumes compared to Fm. A, both at 25 and 100 years. Additionally, the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume distribution across the fault in Fm. B spans a significantly wider range than the plume in Fm. A. This difference can be attributed to the presence of a thin mudstone layer within the Fm. A reservoir, which partially impedes the migration of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume, thereby reducing the risk of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage.

To further assess storage effectiveness and leakage risk after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, it is crucial to analyze pressure changes during the injection process. In this study, we analyze bottom-hole pressure (BHP), average reservoir pressure, \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection rate, and cumulative \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection volume for the Fm. A and Fm. B, as shown in Fig. 9. Figure 9(a), illustrates that during the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection period (25 years, indicated by the orange arrow), reservoir internal pressure gradually increases, leading to an increase in BHP. After injection stops, BHP rapidly decreases and stabilizes, while the reservoir pressure reaches saturation and remains constant. Additionally, we observe that the Fm. B exhibits significantly higher BHP compared to Fm. A, attributed to its approximately double depth relative to Fm. A. Greater formation pressure and rock gravity are experienced at deeper wells, contributing to increase BHP. Moreover, BHP distribution is influenced by the permeability and porosity of the formation: formations with high permeability and porosity typically exhibit lower BHP (Fig. 9(a), red line), whereas formations with lower permeability and porosity show higher BHP (Fig. 9(a), blue line). Before the 25th year, as \(\hbox {CO}_2\) is injected, BHP increases, the average reservoir pressure rises (Fig. 9(b)), and the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) volume accumulates rapidly (Fig. 9(d)). After the 25th year, when \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection stops, BHP rapidly decreases and gradually approaches zero, while the average reservoir pressure stabilizes, and the accumulated \(\hbox {CO}_2\) volume reaches saturation. This is mainly because the area of the reservoir is fixed, and the injection volume during the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection period is also limited (Fig. 9(c)). In Fig. 9(c), the injection rate of Fm. B (blue line) begins to decline earlier compared to Fm. A (red line) and significantly decreases after injection stops in the 25th year, aligning with the decline of the red line. The primary reason for this is that Fm. B is located at greater depth, resulting in higher BHP and average reservoir pressure compared to the shallower Fm. A.

Rock physics model

In this section, we compute \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) using Eqs. (6)-(10). In theory, the relationships between \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) and \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation are shown in Fig. 10(a). Within the 100-year study period, Fig. 10(a) presents a critical point on both the red dashed line and the blue line, where the black pentagram marks the critical point for \(1/V_{\text {p}}\) and the yellow pentagram marks the critical point for \(1/Q_{\text {p}}\). At this critical point, both \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) reach their minimum values as saturation increases. During the reservoir simulation of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume migration, the initial gas saturation (Sg) is 0.7. Over time, \(\hbox {CO}_2\) gradually dissolves into the formation water, reducing \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation to approximately 0.1 by 100 years. The key years–0, 25, and 100–are labeled in Fig. 10. In Fig. 10(a) (red dashed line), it can be observed that theoretically, attenuation initially increases as \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation decreases, reaching a maximum at the critical point and subsequently decreasing. However, since this study focuses on \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration distribution over a 100-year period, attenuation gradually increases as \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation decreases throughout the study duration. At the beginning of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, velocity initially decreases. After injection ceases (25-100 years), velocity slowly recovers, as illustrated by the blue line in Fig. 10(a). This occurs primarily because the modulus of the rock decreases during injection due to \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, simultaneously reducing density. However, after injection ceases, the reduction in density becomes the dominant factor, causing the velocity to recover gradually. Nevertheless, over the entire study period, the overall velocity after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection remains lower than pre-injection levels. Consequently, both density and impedance increase throughout the study period, as shown in Fig. 10(b). Generally, velocity tends to decrease while attenuation (proportional to 1/\(Q_{\text {p}}\)) increases, and vice versa. However, Fig. 10(a) shows both increasing velocity and increasing attenuation during a period (25-100 years). This occurs because, at year 25, \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation in the velocity profile reaches a maximum of 0.3, located on the left side of the critical point. As \(\hbox {CO}_2\) progressively dissolves into the formation water, the saturation decreases and eventually stabilizes at approximately 0.1 by 100 years, as shown in Fig. 10(a). Meanwhile, after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection ceases, \(1/Q_{\text {p}}\) consistently increases from 25 years to 100 years, as depicted by the red dashed line in Fig. 10(a).

The Formation A coarse-scale rock physics analysis

For the Fm. A model, we utilize the baseline velocity values extracted from well logging data as follows: the first layer corresponds to the caprock of the Fm. A with a \(V_{\text {p}}=2502\) m/s; the second layer represents the Fm. A reservoir with a \(V_{\text {p}}=3028\) m/s; and the third layer comprises a thin mudstone layer within the reservoir with a \(V_{\text {p}}=2540\) m/s. The fourth layer is the bottom layer of the Fm. A with a \(V_{\text {p}}= 2680\) m/s. For \(Q_{\text {p}}\) the baseline value is established at 100000, indicating no attenuation within the seismic frequency range before \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection.

Figures 11(a-c) depict the coarse-scale Fm. A \(V_{\text {p}}\) model before \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, during 25 years of injection, and after 100 years of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) monitoring, respectively. Figures 11(d-f) illustrate the coarse-scale Fm. A 1/\(Q_{\text {p}}\) models before \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, during 25 years of injection, and after 100 years of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) monitoring, respectively. Following \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, the velocity around the injection well notably decreases (Fig. 11(b)). Specifically, the velocity observed at year 25 is significantly lower than that at 100 years (see Fig. 11(b-c)). Concurrently, continuous \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection from 0 to 25 years leads to a gradually increase \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation within the reservoir, accompanied by increased attenuation, while porosity remains unchanged (Fig. 11(e)). After injection ceases, the previously injected \(\hbox {CO}_2\) continues to displace water further within the reservoir, expanding the range of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation (Fig. 8(b)). This expansion leads to a subsequent increase in attenuation (Fig. 11(f)). Notably, the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation range of the simulated plume lies between 0.1 and 0.3, with attenuation continuing to increase, as shown in Fig. 10(a). Conversely, velocity decreases at year 25 and subsequently increases. In Fig. 10(a), from year 25 to year 100, saturation decreases and surpasses the critical point. Therefore, the increased velocity at year 100 compared to year 25 is evident in Fig. 11(c).

The Formation B coarse-scale rock physics analysis

Same as above, for the Fm. B model, baseline velocity values extracted from well logging data are as follows: the first layer corresponds to Fm. B caprock with a \(V_{\text {p}}\)=3398 m/s; the second layer represents Fm. B reservoir with a \(V_{\text {p}}\)=3200 m/s; and the third layer represents the bottom layer of B with a \(V_{\text {p}}\)=3660 m/s. The baseline value for \(Q_{\text {p}}\) is set to 100000, consistent with the value used for Fm. A model. Similarly, \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection into the Fm. B followed a pattern consistent with that observed in Fm. A. Initially, we observe a trend where the Fm. B velocity decreases before increasing during \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection (Fig. 12(a-c)), which aligns with the relationship between \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation and velocity at 0, 25, and 100 years shown in Fig. 10(a). Following \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection into Fm. B, increased \(\hbox {CO}_2\) content in the reservoir leads to enhanced attenuation, which continues to rise even after 100 years (Fig. 12(d-f)). In summary, \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection consistently impacts the elastic and anelastic properties of both Fm. A and Fm. B, regardless of injection depth. After injection, we note a consistent pattern in velocity and attenuation: velocity initially decreases and then increases, while attenuation continues to rise.

Time-lapse Seismic imaging in fine-scale

Based on the analysis provided above, \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation was simulated using coarse-scale models of Fm. A and Fm. B. Subsequently, we use the rock physics theory to establish \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) models. In order to better simulate the seismic response of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume at the original model scale, we interpolate the changes in \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) caused by \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection from the coarse grid to the fine-scale grid, obtaining \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) models on the fine-scale grid. The results from reservoir simulation and rock physics modelling indicate that the changes in \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation, \(V_{\text {p}}\), and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) at the 100th year after injection stop are more significant compared to those observed at year 25 during injection. Therefore, using year 100 as an example, we interpolate the coarsened \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) obtained from rock physics at year 100 to the fine-scale models. This yielded the fine-resolution \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) models for Fm. A and Fm. B at year 100 after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection cessation, as shown in Fig. 13. Figure 13 depicts the \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) models at 100 years after the cessation of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, where Fig. 13(a-b) and Fig. 13(c-d) show the seismic properties of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume after 100 years for Fm. A and Fm. B, respectively. Figure 13 provides insights into the distribution of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume and the location of the injection well. Notably, the results reveal that the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume distribution in both fine-scale (Fig. 13) and coarse-scale (Fig. 11 and Fig. 12) models exhibits similar patterns. Upon closer examination of Fig. 8, we observe that Fm. A and Fm. B exhibit the same plume migration patterns. In general, greater formation depths correspond to higher formation pressures. According to Henry’s law, under specific temperature and equilibrium conditions, the solubility of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) in a liquid is directly proportional to the equilibrium pressure of \(\hbox {CO}_2\). Consequently, considering the relatively shallow depth of Fm. A, one might expect the lateral migration distance of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume to be much greater compared to Fm. B. However, the simulations indicate the contrary. This difference can be attributed to the presence of a 20-meter-thick mudstone layer within Fm. A, which exerts a trapping effect on the injected \(\hbox {CO}_2\).

In this section, based on the above analysis, we utilize the viscoacoustic wave Eqs. (12)-(14) to conduct seismic forward modelling and RTM. The forward modelling of time-lapse data considers both velocity and attenuation changes over time. However, it should be pointed out that the attenuation caused by the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume is not compensated during the implementation of the viscoacoustic RTM. Figure 14(a) shows the shot gathers of the baseline seismic models. Figure 14(b-c) show the shot gathers of the Fm. A and Fm. B models at 100 years after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, respectively. The effects of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume cannot be directly observed in Fig. 14, because the impacted region is minimal. To address this concern, Fig. 15(a-b) show the differences between the baseline data and monitor data, and Fig. 15(c-d) compare single-trace shots between baseline data and monitor data. In Fig. 15, the shot gathers of Fm. A exhibit noticeable amplitude loss and phase distortion compared to the baseline data. Moreover, the difference between baseline data and monitor data shows that the attenuation caused by the injection of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) into Fm. A is more significant than that in Fm. B, indicating that the appearance of the fault promotes the migration of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume. As a result, this experiment reveals that the migration of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume causes significant attenuation in the seismic data.

Then, we conduct RTM based on the modeled shot gather data. The numerical simulation results indicate that after 75 years of monitoring, the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume migrates farther and covers a larger area compared to that observed after the 25-year injection period. Figure 16 shows the RTM results of the fine-scale models of Fm. A and Fm. B, indicating that the attenuation zone 100 years after the cessation of injection is larger than that observed at year 25 during injection. The red solid arrows indicate the leftward migration of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume across the fault, with the horizontal extent after 100 years surpassing that after 25 years. A comparison between Fig. 16(a) and Fig. 15(b) highlights that the results at 100 years (Fig. 16(b)) exhibit more pronounced and extensive attenuation due to \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume migration. This similar result can also be observed in the Fm. B (Fig. 16(c) and Fig. 16(d)). Additionally, Fig. 16 illustrates that \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection results in reduced seismic amplitudes and degraded resolution, which can be verified by comparing Fm. A between in Fig. 16(a) and Fig. 16(b). This phenomenon arises from \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation within the reservoir, causing significant attenuation.

To clearly show the seismic response of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume, we extract single-traces from the baseline image as well as the images after 25 and 100 years, respectively and show them in Fig. 17. In Fig. 17, it is evident that \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection results in seismic images with weaker amplitudes and distorted phases compared to the baseline image, indicating significant attenuation due to \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection. In addition, by comparing the red dashed lines with the cyan dashed lines in Fig. 17, it is observed that seismic events after 100 years exhibit more pronounced phase distortion and amplitude loss (indicated by the red arrow). This finding suggests that attenuation within the formation intensifies with \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration.

Moreover, using the baseline data as reference, Fig. 18 depicts differences between the baseline migrated images and Fig. 16, allowing for the estimation of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) distribution. As shown in Fig. 18, the difference clearly illustrates the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) response in seismic imaging, indicating that seismic imaging techniques can effectively monitor \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration. In Fig. 18, we mark the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection points for the shallow layer Fm. A and deep layer Fm. B. Additionally, we mark two regions, I and II, at the same location and window size at year 25 and year 100 in Fm. A, as shown in Fig. 18(a-b). Similarly, we mark region III at the same location and window size for 25-year and 100-year in Fm. B, as shown in Fig. 18(c-d). These regions will be used in the section “attenuation quantification using the spectra ratio method” to analyze the attenuation effects at 25-year during \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection and at year 100 after injection ceases. In Fig. 18(b), we mark region IV to compare the attenuation effects in Fm. A at year 100, where no leakage occurs (Fig. 18(b)), with those where leakage occurs, using the same location and window size, as described in the section “\(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage detection”.

Attenuation quantification using the spectra ratio method

In this study, we use a narrow and elongated window for data selection. The narrow horizontal dimension allows for extracting neighboring traces, enabling averaging to reduce noise and migration artifacts in the spectra. The vertical elongation ensures that the spectral variations within each window, caused by structural differences, remain statistically consistent, especially since the compared and reference windows are at the same depth76. The selection of the frequency range is also important for the spectral ratio results. We choose the middle range of frequencies, avoid both too-low and too-high frequencies. The input wavelet lacks sufficient low-frequency content, and high frequencies are dominated by noise due to attenuation. In practice, we pick several windows over the region of interest and design the frequency range accordingly. We find that the frequency range we choose consistently provides a good signal-to-noise ratio across the region. The selection of the window size and wavenumber band range was done on a case-by-case basis. First, we examine the valid frequency range and determine the corresponding wavelength. The window length should be larger than the wavelength to capture the relevant features of the signal. In practical applications, it is not feasible to window each event individually, as each window often contains multiple reflectors. These reflectors can interact with the spectrum, introducing uncertainty into the spectral analysis for attenuation. However, we believe that by increasing the window size, the impact of individual reflectors diminishes due to the statistical averaging effect. On the other hand, if the window is too large, it can lose the ability to localize interval attenuation effects. To determine the best window size, we systematically adjust the window width at a selected location and observe how much the estimated \(Q_{\text {p}}\) value changes. Through testing, we find that the \(Q_{\text {p}}\) value remains stable after a 45 m window size, suggesting that window lengths larger than this would result in reduced uncertainty. Based on this analysis, we chose a 50 m window size for our study.

To better assess the attenuation effect, we compute the wavenumber spectrum spectral ratio corresponding to the black dashed boxes in regions I-III, as shown in Fig. 18. The results are shown in Fig. 19, where the wavenumber spectrum is shown in Fig. 19(a), (c), and (e), and the spectral ratio is shown in Fig. 19(b), (d), and (f). Notably, we can observe a pronounced decrease in amplitude, particularly at higher frequencies. During the 0-25 year \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection period, the high-frequency amplitude in both Fm. A and Fm. B decreases significantly as \(\hbox {CO}_2\) is injected, and the rate of decrease slows after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection stops. In Fig. 19(a), the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume spectrum in region I Fm. A shows attenuation effects from 25 to 100 years, but these effects are not very pronounced. This happens because only a small portion of the plume migrates to region I after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection ceases, as shown in Fig. 18(b). Regions I (Fm. A) and III (Fm. B) show similar outcomes, with significant attenuation effects in the spectrum from 25 to 100 years after the cessation of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, as shown in Fig. 19(a) and (e). However, the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume spectrum for region II in Fm. A, located in a shallow layer near the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection wells, remains relatively stable throughout the 25-100-year monitoring period, as shown in Fig. 19(c). This stability is primarily attributed to the cessation of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection after 25 years.

To quantify the attenuation caused by \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, we employ the spectral ratio method74. Based on the spectral ratio theory, we utilize Eq. (24) to compute the attenuation resulting from \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection at year 25 during injection and at year 100 after injection cessation. Subsequently, we generate the logarithm of the ratio, revealing a linear trend across frequencies, as shown in Fig. 19(b), (d) and (f). The curves are approximately linear, each demonstrating a distinct negative slope, indicating significant attenuation effects induced in the formation during the 25-year \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection period and 100 years after the injection stops. Generally, the wavenumber interval for linear fitting is chosen empirically on a case-by-case basis. In this study, based on our practical tests, we use a wavenumber interval of 0.014 1/m for the linear fit in Fig. 19. Furthermore, the distinction in spectral attenuation effects between 25 and 100 years can be effectively quantified by calculating the quality factor (\(Q_{\text {p}}\)). In Fig. 19(b), the calculated \(Q_{\text {p}}\) values are 23.98 (red curve) and 19.32 (black curve); in Fig. 19(d), they are 15.52 (red curve) and 12.79 (black curve); and in Fig. 19(f), they are 12.35 (red curve) and 10.41 (black curve), respectively. Basing on the calculated \(Q_{\text {p}}\) values, we observe that stronger attenuation occurs with the migration of the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume. In addition, as illustrated in “spectral ratio theory” in the previous section, the slope of the logarithm of the ratio between the reference image and monitor image can be used to vividly describe the attenuation caused by the injection of \(\hbox {CO}_2\). Following the work of69,70, we calculate the slope maps corresponding to Fig. 16, as shown in Fig. 20. In Fig. 20, the formation directly below the \(Q_{\text {p}}\) anomaly shows an obvious attenuation effect, while the attenuation effect becomes weaker further away from the \(Q_{\text {p}}\) anomaly. When the initial attenuation is nearly negligible, the attenuation quantified using the spectral ratio method represents an absolute estimation. Since we use the baseline image as the reference, this approach quantifies the real attenuation value caused by \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection. This result suggests that the injection of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) can be well described by the spectral ratio method. As a result, based on the above analysis, the seismic imaging technique can be used as a useful tool for monitoring the status of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration.

\(\hbox {CO}_2\) Leakage detection

As shown in Figs. 13-20 the proposed method effectively enables the quantitative characterization of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume analyzing the seismic response due to the attenuation caused by the injection of \(\hbox {CO}_2\). Therefore, our method provides an opportunity to predict \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage using known reservoir properties. Additionally, we can employ our previously illustrated image-domain spectral ratio method to detect \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage from seismic images, allowing us to monitor safety hazards based on time-lapse seismic datasets.

To make predictions, we conduct reservoir modelling simulations and observe that \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume migration led to leakage. Effective sealing is essential for \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage in saline aquifers, as it well prevents the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume from leaking. Our workflow allows us to understand and predict how the properties of saline aquifers influence \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage. When the permeability and porosity of the caprock are high or the dip separation is significant, \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage can easily occur. Using Fm. A as an example, we increased the permeability of its caprock to simulate leakage and applied this new workflow for monitoring. Figure 21(a) shows the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation in Fm. A after 100 years, which is simulated using the modified permeability and porosity, and Fig. 21(b-c) show the corresponding velocity model and attenuation model, respectively. In Fig. 21, it is clear that the velocity and attenuation exhibit obvious anomalies, and we observe that leakage results in significant attenuation above the injected reservoir as \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migrates into the sealing layer, when leakage occurs.

Then, using the \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) models shown in Fig. 21, we perform seismic modelling to obtain seismic data. Figure 22(a) illustrates the RTM imaging result for leakage in Fm. A at 100-year, while Fig. 22(b) highlights the difference between the monitoring data at 100-year and the baseline data. By comparing Fig. 22(a) and Fig. 16(b), we observe that the RTM imaging result with \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage shows larger attenuation areas than the RTM imaging result without \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage, particularly in deep layers. This result can be further observed in imaging difference (Fig. 22(b)). Figure 22(b) shows that the cap rock of Fm. A exhibits attenuation effects, highlighting that seismic imaging method gives a preliminary demonstration of the leakage effects. To better illustrate the proposed method in detecting \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage, we perform spectral analysis of imaging results using the image-domain spectral ratio method. Regions II and IV from Fig. 18(b) serve as references for the 100th year without leakage (the red curves in Fig. 22), while the black curves represent regions II and IV from Fig. 22(b) under leakage conditions at the year 100. In Fig. 22, the blue curves show the baseline condition without \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection. Figure 22(c-d) and Fig. 22(e-f) display the spectrum of regions II and IV, respectively. First, we focus on the mudstone sediments (the cap rock of Fm. A, i.e. region IV), using the baseline (blue line) as a reference. Figure 22(c) shows the spectrum comparison between Fm. A with leakage (black lines) and without leakage (red and blue lines), and Fig. 22(d) is the corresponding spectral ratio. In Fig. 22(c-d), we find that Fm. A without leakage shows a similar result to the baseline imaging result (blue lines), while Fm. A with leakage shows significantly attenuated spectrum. Additionally, the spectral ratio in Fig. 22(d) (black lines) displays a linear decreasing trend after leakage. This result illustrates that after \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage, we can observe that the spectrum of imaging result exhibits significantly reduced amplitude. Then, we focus on region II (Fig. 22(e-f)), which is the reservoir of Fm. A. In Fig. 22(e-f), compared with the baseline imaging result (blue lines), the spectrum of both the imaging result with leakage and without leakage shows attenuation. The spectrum of imaging result with leakage exhibits stronger attenuation, and its spectral ratio has a larger decrease trend, in comparison to the imaging result without leakage. In summary, the above findings demonstrate that the proposed approach can effectively characterize the status of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume, providing the potential for monitoring \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage from seismic datasets.

Discussion

Compared to previous workflows42,43, our new approach offers two key advantages. First, it integrates the analysis of attenuation caused by \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection, specifically tailored to the typical saline aquifer in the Pearl River Mouth Basin (PRMB). Second, this method transitions from the data domain in time to the imaging domain in depth, further expanding from the 3D to the 4D seismic imaging domain. This enhances the overall accuracy of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) sequestration monitoring by quantifying the attenuation effects in time-lapse seismic imaging through the introduction of the spectral ratio method, thereby broadening its applicability.

Analyzing the attenuation caused by injected \(\hbox {CO}_2\) is crucial33,34,35,77, as it alters the elastic and anelastic properties of the reservoir and significantly impacts the resolution and signal-to-noise ratio of seismic imaging. A thorough understanding of these attenuation effects can enhance the monitoring accuracy of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) sequestration projects, ensuring injection safety and reservoir stability. Although previous studies indicated that attenuation can effectively describe changes in \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation, they did not close the loop with reservoir simulation. In seismic imaging for exploration, this spectral ratio method can be employed to analyze the intensity of attenuation in migrated images. Notably,69,70have advanced this method to enhance post-stack migration results. Considering the benefits of the spectral ratio method, we propose its application for monitoring \(\hbox {CO}_2\) time-lapse seismic data and extend it to the 4D seismic domain. Figure 16 and Fig. 18 illustrate the differences between the RTM imaging results for the baseline and monitor seismic data, respectively. The seismic response following \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection appears subtle, as shown in Fig. 14. However, Fig. 19 and Fig. 20 demonstrate that the spectral ratio method can be effectively utilized for the quantitative analysis of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) attenuation, revealing significant changes between the baseline and monitoring data. Thus, this new workflow not only establishes a complete closed loop but also analyzes the attenuation following \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection and employs the spectral ratio method to more effectively quantify its attenuation effect.

Additionally, based on the geological model, we embed a 20-meter-thick mudstone layer in Fm. A, mainly due to the presence of faults in the synthetic model and the high permeability and porosity of Fm. A, which makes it prone to leakage. The addition of the mudstone layer significantly reduces the likelihood of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage. Figures 8, 11, 12, 13, 18, and 20 show that the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation, elastic and anelastic parameters, and seismic response in the area with the embedded mudstone layer within Fm. A are considerably less impacted than those in Fm. B. This finding further confirms that the presence of the mudstone layer significantly improves the sealing capacity for \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage. Then, we conduct a test on the leaked \(\hbox {CO}_2\), demonstrating that the proposed new workflow effectively monitors its attenuation effect, as shown in Figs. 21 and 22.

Conclusions

In this study, we develop a new integrated workflow for time-lapse seismic monitoring of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage in saline aquifers. First, we synthesize reservoir and seismic properties of the typical saline aquifer, based on field information. Then, we successfully establish a workflow to characterize the distribution and migration of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) in a saline aquifer by integrating reservoir modelling, rock physics analysis, and time-lapse seismic techniques. The following conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

In the context of the well logging data from the PRMB, we establish a typical saline aquifer velocity and density models for \(\hbox {CO}_2\) research. In this model, the sandstone velocity of Fm. A is higher than that of surrounding mudstone layers, while Fm. B shows opposite result. The PRMB contains thick sedimentary layers with high-porosity, high-permeability reservoirs, complemented by low-permeability caprock that ensures efficient injection and secure long-term storage.

-

(2)

To address the scale differences between reservoir simulation and seismic modelling, we employ upscaling scheme for \(\hbox {CO}_2\) dynamic simulation. Through the reservoir simulation, we observe that \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation gradually increased over time. However, \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation significantly decreased as it dissolved into the reservoir water. Additionally, the presence of a thin mudstone layer in the reservoir hinders the migration of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume to some extent, thereby reducing the risk of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) leakage.

-

(3)

Using the rock physics theory, we build relationships between the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation and seismic properties, and establish the seismic models (\(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\)). The rock physics analysis indicates that as \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation decreases, the velocity intensity first decreases, reaches a minimum at the critical saturation point, and then increases with further \(\hbox {CO}_2\) depletion. In contrast, the attenuation consistently increases as \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation decreases. However, because this study focuses on the 100-year \(\hbox {CO}_2\) migration distribution, attenuation steadily increases as \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation decreases. This is mainly because \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection reduces the rock’s modulus and density. After injection stops, the ongoing density reduction becomes the dominant factor, allowing velocity to recover gradually. Nevertheless, throughout the 100-year period, the overall post-injection velocity remains below its pre-injection level. At the same time, 1/\(Q_{\text {p}}\) continues to increase over the entire 100 years.

-

(4)

To analyze the seismic response of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation on seismic data, we employ a viscoacoustic wave equation to perform time-lapse seismic modelling and RTM without attenuation compensation, using the established \(V_{\text {p}}\) and \(Q_{\text {p}}\) models. The analysis of calculated seismic data demonstrate that the attenuation caused by \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation can be observed using the time-lapse seismic technique. Additionally, to effectively quantify this attenuation, we perform spectral analysis and the spectral-ratio method on seismic data, and numerical experiments verify the effectiveness of this technique.

-

(5)

This workflow can predict the \(\hbox {CO}_2\) plume migration and leakage. The spectral analysis on the seismic image can effectively monitor \(\hbox {CO}_2\) injection and leakage. Meanwhile, we can measure the associated attenuation effects during storage. Our developed workflow not only enhances our understanding of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) behavior within the reservoir but also provides a reliable approach for prediction and early detection of potential leakage, ensuring the safety and effectiveness of \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage efforts.

In conclusion, our study models time-lapse seismic data from reservoir simulations, using rock physics as a bridge to connect petrophysical properties with seismic properties. Our approach can calculate \(\hbox {CO}_2\) saturation changes after injection, and the resulted changes in seismic properties, such as seismic image responses and attenuation effects. This approach enables the characterization of subsurface \(\hbox {CO}_2\) storage in saline aquifers and addresses the challenges associated with varying scales and interdisciplinary research. Utilizing geological information from the PRMB region in China, we develop a realistic dataset that accurately reflects local geological conditions. This dataset will be made available as an open-access resource, providing as a valuable tool for validating and advancing CCS research.

Data availability

The reservoir model, \(V_{\text {p}}\) model, \(Q_{\text {p}}\) model, permeability model, porosity model, and density model related to this article can be found at the following link Reservoir-rock-physics-and-Seismic-Modelling.

References

Davis, T. L., Landrø, M. & Wilson, M. Geophysics and geosequestration (Cambridge University Press, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316480724.

Wang, Z. et al. Risk evaluation of co2 leakage through fracture zone in geological storage reservoir. Fuel 342, 127896. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2023.127896 (2023).

Haszeldine, R. S. Deep geological co 2 storage: Principles reviewed, and prospecting for bio-energy disposal sites. Mitig.Adapt. Strateg. for Glob. Chang. 11, 377–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-005-9005-6 (2006).

Hu, Q., Grana, D. & Innanen, K. A. Feasibility of seismic time-lapse monitoring of co2 with rock physics parametrized full waveform inversion. Geophys. J. Int. 233, 402–419. https://doi.org/10.1093/gji/ggac462 (2023).

Sundal, A., Miri, R., Ravn, T. & Aagaard, P. Modelling co2 migration in aquifers; considering 3d seismic property data and the effect of site-typical depositional heterogeneities. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 39, 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2015.05.021 (2015).

Ma, W., Jafarpour, B. & Qin, J. Dynamic characterization of geologic co2 storage aquifers from monitoring data with ensemble kalman filter. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 81, 199–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2018.10.009 (2019).

Bourne, S., Crouch, S. & Smith, M. A risk-based framework for measurement, monitoring and verification of the quest ccs project, alberta, canada. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 26, 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2014.04.026 (2014).

Bachu, S. Co2 storage in geological media: Role, means, status and barriers to deployment. Prog. Energy combustionSci. 34, 254–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecs.2007.10.001 (2008).

Goodman, A., Sanguinito, S. & Levine, J. S. Prospective co2 saline resource estimation methodology: Refinement of existing us-doe-netl methods based on data availability. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 54, 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2016.09.009 (2016).

Li, S., Zhang, Y. & Zhang, X. A study of conceptual model uncertainty in large-scale co2 storage simulation. Water Resour. Res. 47 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1029/2010WR009707.

Lackner, K. S. A guide to co2 sequestration. Science 300, 1677–1678 (2003). https://www.science.org/doi/abs/10.1126/science.1079033.

Arts, R. et al. Monitoring of co2 injected at sleipner using time-lapse seismic data. Energy 29, 1383–1392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2004.03.072 (2004).

Chadwick, R., Williams, G. & Falcon-Suarez, I. Forensic mapping of seismic velocity heterogeneity in a co2 layer at the sleipner co2 storage operation, north sea, using time-lapse seismics. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 90, 102793. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2019.102793 (2019).

Cairns, G., Jakubowicz, H., Lonergan, L. & Muggeridge, A. Using time-lapse seismic monitoring to identify trapping mechanisms during co2 sequestration. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 11, 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2012.08.014 (2012).

Will, R. et al. Time-lapse integration at fwu: Fluids, rock physics, numerical model integration, and field data comparison. Energies 14, 5476. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14175476 (2021).

Fawad, M. & Mondol, N. H. Monitoring geological storage of co2 using a new rock physics model. Sci. Rep. 12, 297 (2022). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-04400-7.

Grude, S., Landrø, M. & Osdal, B. Time-lapse pressure-saturation discrimination for co2 storage at the snøhvit field. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 19, 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2013.09.014 (2013).

The frio brine pilot project. Al Hosni, M., Vialle, S., Gurevich, B. & Daley, T. M. Estimation of rock frame weakening using time-lapse crosswell. Geophysics 81, B235–B245. https://doi.org/10.1190/geo2015-0684.1 (2016).

Zhang, R., Ghosh, R., Sen, M. K. & Srinivasan, S. Time-lapse surface seismic inversion with thin bed resolution for monitoring co2 sequestration: A case study from cranfield, mississippi. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 18, 430–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2012.08.015 (2013).

White, D. Seismic characterization and time-lapse imaging during seven years of co2 flood in the weyburn field, saskatchewan, canada. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 16, S78–S94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2013.02.006 (2013).

Harvey, S., Hopkins, J., Kuehl, H., O’Brien, S. & Mateeva, A. Quest ccs facility: Time-lapse seismic campaigns. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control. 117, 103665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijggc.2022.103665 (2022).

Amundaray, N., Innanen, K., Macquet, M. & Lawton, D. Time-lapse acoustic fwi of vsp data with applications to monitoring co2 at the cami field research station: A feasibility study (2021).