Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between the Inflammatory Burden Index (IBI) and risks of all-cause and cancer-specific mortality, focusing on its potential to enhance risk stratification. The research included a cohort of 14,835 participants from the American National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. IBI was calculated using the formula CRP × (neutrophil / lymphocyte). Cox regression analysis was applied to assess the associations. During 223,719.71 person-years of follow-up, 3483 deaths (23.48%) occurred, including 778 (5.24%) from cancer. Mortality rates were 15.57 (all causes) and 3.48 (cancer) per 1,000 person-years. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed the highest IBI quartile had the lowest survival rates for all-cause and cancer-related mortality (Log-Rank p < 0.001). Adjusted models revealed a 23.4% higher risk of all-cause mortality and a 14.1% higher cancer-specific mortality per standard deviation increase in IBI. Smooth curve fitting confirmed a proportional relationship between IBI and mortality risk. ROC curve and reclassification analyses supported IBI’s role in improving mortality risk prediction. The findings of this study indicate noteworthy associations between IBI and both all-cause and cancer-specific mortality. Moreover, the results highlight the potential of IBI in enhancing risk stratification for incident all-cause and cancer-specific mortality within the general population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer is recognized as one of the major causes of mortality1. Cancer still ranked as the first cause of premature death among the population aged less than 70 years old in over one hundreds counties until 20192. In 2020, there were 19.3 million new cancer cases occurred and nearly 10 million patients deceased due to cancer3. Additionally, the global cancer prevalence is predicted to increase by 47 percents in 20403. Due to the great burden from cancer, it is critical to reduce the impact of cancer via improving the preventive efficacy. For the prevention of cancer, it is of great importance to improve the risk prediction of cancer mortality.

Chronic inflammation plays a crucial role in oncogenesis and tumor progression by creating a pro-oncogenic microenvironment that supports and sustains cancer growth4,5. Inflammation is described as the 7th major emblem of cancer6. From the view of basic mechanism, inflammatory mediators could function similar to genetic mutagens and interfere DNA repair processes and cell cycle checkpoints, resulting in the accumulation of chromosomal abnormalities, which are a significant contributing factor to cancer; Additionally, chronic inflammatory reactions often release free radicals, which can increase the likelihood of DNA accumulating mutations. This, in turn, may result in the translation of proteins with abnormal functions7. Furthermore, the inflammatory mediators in the microenvironment could facilitate tumor cells in proliferation, expansion, and escape from immune recognition and clearance8. Accordingly, monitoring of inflammatory burden could help to improve the risk prediction of cancer and the subsequent complications.

Several inflammatory biomarkers, such as neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR)9platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio10,11C-reactive protein (CRP)12systemic immune-inflammation index13 and systemic inflammation response index14have been widely investigated for their prognostic value in oncology. These markers have been associated with overall survival, recurrence risk, and treatment response across multiple cancer types, including lung, gastric, colorectal, breast, and etc. For instance, elevated NLR has been linked to poorer survival outcomes in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and gastric cancer15,16. Despite their prognostic utility, these indicators often reflect only one facet of the inflammatory process—either immune cell imbalance or acute-phase response.

Recently, a novel index known as the inflammatory burden index (IBI) has been proposed to provide a more comprehensive assessment of systemic inflammation by integrating two key components: C-reactive protein (CRP), reflecting the acute-phase inflammatory response, and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), representing immune cell imbalance; the pilot study has demonstrated its prognostic value in cancer patients17. However, the association between IBI and mortality in general population is still unknown. Therefore, the current study aimed to evaluate the association between IBI and all-cause and cancer mortality in general population, and to estimate the impact of IBI in predicting all-cause and cancer mortality in the general population.

Methods

Study design and population

The study subjects originated from the cross-sectional survey conducted in America named National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The population contained subjects from five survey rounds, including 1999–2000, 2001–2002, 2003–2004, and 2005–2006. Detailed descriptions of the study design, protocol, and methods are available at its official website (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analytic guidelines.aspx). The data of NHANES were freely open to researchers at its official website (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm ). In short, the NHANES survey is a continuous cross-sectional survey conducted in America every two years by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS, a department of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). In each round of the NHANES survey, the population was sampled around America, and the survey endorsed a multistage, stratified, and clustered probability sample pattern to optimize its representativity. Furthermore, a series of calibration variables were also provided by the NHANES to improve the representativity of the NHANES survey. NCHS linked the NHANES data to the National Death Index by December 31, 2019. Therefore, the current analysis was a longitudinal analysis with follow-up data. In the present study, the inclusion criterion was NHANES 1999–2006 subjects aged equal to or more than 20 years old. Subjects with incomplete data used in the current analysis were excluded from the analysis. A total of 14,835 subjects with complete data were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). The NCHS institutional Ethics Review Board approved the study design of NHANES. Additional Ethics Review for the current study is unnecessary. Data used in the present study are available to the public at the official website of NHANES. Participants of the current study were drawn from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). The subjects included participants from four survey cycles, specifically the years 1999–2000, 2001–2002, 2003–2004, and 2005–2006. Comprehensive details regarding the study design, protocol, and methodologies can be found on the official NHANES website (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/analytic guidelines.aspx). NHANES data are publicly accessible to researchers through its official site (https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm). In summary, NHANES is a continuous cross-sectional survey carried out biennially by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), a division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Each survey round involved sampling populations from across the United States, utilizing a multistage, stratified, and clustered probability sampling method to enhance representativeness. The NCHS linked NHANES data to the National Death Index by December 31, 2019, enabling a longitudinal analysis with follow-up data. For this study, the inclusion criteria specified that participants from NHANES 1999–2006 must be aged 20 years or older. Subjects with incomplete data were excluded from the analysis, resulting in a final sample of 14,835 participants (Fig. 1). The study design of NHANES received approval from the NCHS Institutional Ethics Review Board, and no further Ethics Review is required for this current analysis. The data utilized in this study are publicly available on the NHANES official website.

Data collection

The interview was carried out at each participant’s home during the survey, while physical and laboratory examinations took place at the Mobile Examination Center (MEC). Race data were obtained from respondents’ answers to questions regarding race and Hispanic origin. Individuals who identified as “Mexican American” were coded accordingly, regardless of any additional race-ethnicity identities they may have had. Those who identified as “Hispanic” but did not specify “Mexican American” were categorized as “Other Hispanic.” All other non-Hispanic respondents were classified based on their self-reported races: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and other non-Hispanic races, which included non-Hispanic multiracial participants. The poverty income ratio (PIR) was calculated as the family income relative to the current poverty threshold. Current smoking status was determined if a participant responded “every day” or “someday” to the question, “Do you now smoke cigarettes?” Current alcohol consumption was verified if a participant reported having consumed at least twelve drinks in the year preceding the survey. Cancer morbidity was defined if a subject answered “yes” to the question “Ever told you have cancer or malignancy” at baseline.

Blood pressure measurement details can be found in the “Physician Examination Procedures Manual” on the official NHANES website (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ContinuousNhanes/manuals.aspx?BeginYear=1999). In summary, blood pressure was measured using a calibrated sphygmomanometer after the participant had sat and rested for a minimum of five minutes, and the mean of three consecutive readings was used in the analysis. For other anthropometric measurements, height was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm, while weight was noted to the nearest 0.1 kg. Waist circumference (WC) was measured at 1 cm above the umbilicus, and results were quantified to the nearest 0.1 cm.

Biosamples were sent to NCHS-certified laboratories. Blood lipids were measured using enzymatic assays on the Roche Modular P and Roche Cobas 6,000 chemistry analyzers. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG) was determined using the oxygen rate method on the Modular Chemistry side of the Beckman DxC800, and CRP levels were quantified through latex-enhanced nephelometry with a Behring Nephelometer. SIEMENS blood auto-analyzer (ADVIA2120i, SIEMENS, Berlin, German) was used to perform the blood routine test. Further details regarding the laboratory examinations are summarized on the NHANES official website (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ContinuousNhanes/labmethods.aspx?BeginYear=1999).

Exposure

IBI was calculated for each participant by multiplying the CRP level by the neutrophil count and then dividing by the lymphocyte count. This relationship can be expressed as IBI = CRP × (neutrophil / lymphocyte), where a higher IBI score indicate a greater inflammatory burden17.

Outcomes

The study’s outcome was determined by the final mortality status obtained from the National Death Index (NDI), a highly reliable tool for identifying death(https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-linkage/mortality-public.htm). Disease-specific mortality was classified using the ICD-10 system, with cancer-related deaths defined by ICD-10 codes C00-C97. In total, the study recorded 3,483 deaths, of which 778 were attributed to cancer.

Covariates

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m²). The use of antihypertensive medication was defined as taking antihypertensive drugs within the past two weeks. Antidiabetic therapy was indicated by answering “yes” to either “Do you take diabetic pills to lower blood sugar?” or “Are you currently taking insulin?” Hypertension was defined as a mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) of 140 mmHg or higher, with or without a mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) of 90 mmHg or higher. Additionally, participants who reported using antihypertensive medications in the past two weeks were classified as hypertensive patients18. Diabetes was identified with a fasting plasma glucose (FPG) level of 7 mmol/L or higher and/or self-reported antidiabetic therapy19. Cancer morbidity was confirmed if a subject answered “Yes” to the question “Ever told you had cancer or malignancy”.

Statistical analysis

Due to the NHANES survey design, all data were statistically weighted for analysis (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/tutorials/Weighting.aspx). Since our analysis included FPG data, we used the appropriate NHANES subsample weight “WTSAF4YR” and “WTSAF2YR”, which is designed for the fasting subsample. To account for the combination of four 2-year NHANES cycles (1999–2006), we followed NHANES analytic guidelines and constructed the final weights variate by the following formula: 2/4 * WTSAF4YR for 1999–2002, 1/4 * WTSAF2YR for 2003–2006. The complex survey design was incorporated using SDMVPSU (primary sampling units), SDMVSTRA (sampling strata), and the adjusted weights variate in all weighted analyses to ensure nationally representative estimates. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies with 95% confidence intervals (CI), while continuous variables were summarized as mean or median values with 95% CI. The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. For comparisons of continuous variables with normal distributions between groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied, while the Rank-sum (Kruskal–Wallis) test was used for continuous variables with skewed distributions. Kaplan–Meier curves and Log-Rank tests were employed to assess differences in mortality survival rates across IBI quartile groups. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to examine the independent association between IBI and the mortality risk, with results expressed as hazard ratios (H.R.) and 95% CIs. Since no standardized clinical cut-off values for IBI have been established, participants were categorized into quartiles based on the distribution of IBI within the study population. This data-driven grouping approach is commonly used in epidemiologic studies to facilitate relative risk comparisons across exposure levels20,21. Proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals. The crude model explored the association between IBI and mortality risk without adjusting covariates; Model 1 adjusted common demographical covariates (including age, sex, race, current smoking, current drinking, PIR); Model 2 adjusted more anthropometric, laboratory, and medical history data (including BMI, WC, TC, triglycerides, Scr, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer morbidity). The selection of covariates for the Cox models was based on the following three criteria (meeting at least one): (1) Variables that showed a potential association with all-cause mortality in univariate Cox regression (p < 0.1); (2) Variables that have been consistently associated with all-cause mortality in prior published studies; (3) Variables recognized as clinically relevant risk factors for all-cause mortality based on expert knowledge and routine clinical practice. To account for competing risks from non-cancer causes of death, we additionally performed a Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard analysis. Additionally, the study used a generalized additive model with a spline smoothing function to evaluate whether the relationship between IBI and the mortality risk was linear across the full range of IBI values. Lastly, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis and reclassification metrics (including the continuous net reclassification index, NRI, and integrated discrimination index, IDI) were performed to assess the value of CTI in enhancing risk stratification for cancer mortality. All statistical analyses were conducted using R (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation), EmpowerStats (http://www.empowerstats.com, X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, MA, USA), Stata Statistical Software (version 15.0; StataCorp LLC), and MedCalc (Version 20, MedCalc Software Ltd). Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P value of less than 0.05.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the enrolled subjects were summarized in Table 1. Age increased progressively from IBI quartile 1 to quartile 4, while the percentage of males decreased across the same quartiles. There were no statistically significant differences in race distribution or PIR between the groups. The rate of current smoking increased, whereas the rate of current drinking decreased from the lowest to the highest IBI quartile. Regarding anthropometric parameters, weight, BMI, WC, SBP, and DBP increased, while height decreased from quartile 1 to quartile 4. In terms of laboratory results, Scr and TC showed significant differences between groups, but no clear upward or downward trend was observed. However, triglycerides, CRP, and neutrophils increased, while lymphocytes decreased significantly from quartile 1 to quartile 4. In the medical history data, the use of anti-hypertensive therapy, anti-diabetic therapy, and cancer incidence consistently rose from the lowest to the highest quartile. Consequently, the prevalence of hypertension and diabetes also increased from quartile 1 to quartile 4. Finally, the IBI value significantly increased from 0.09 in quartile 1 to 3.79 in quartile 4 (P < 0.001).

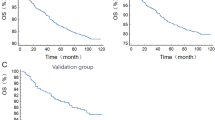

The results of the KM curve were depicted in Fig. 2 and the follow-up data were summarized in Figure S1. In panel A, we observed a clear difference between each group, quartile 1 had the highest all-cause survival throughout the follow-up, and quartile 2 to 4 had lower all-cause survival rate than their previous quartile. The Log Rank test revealed a significant difference of all-cause survival rate between groups (P < 0.001). In panel B, we also observed a highest cancer-caused mortality in quartile 4 and a lowest cancer-caused mortality in quartile 1. But the mortality rate did not differ clearly between quartile 2 and 3. Nevertheless, the Log Rank test also demonstrated that the cancer mortality rate was significantly differed between IBI quartile groups (P < 0.001).

Kaplan-Meier curve of the cancer-caused death survival rate across IBI quartile groups. Panel (A) Free of all-cause mortality across IBI quartile groups; Panel (B) Free of cancer-caused mortality across IBI quartile groups. The phrase “free of” in the figure legend refers to individuals who did not experience the event (either all-cause mortality or cancer mortality) during the study period. In this context, being “free of all-cause mortality” means that the individuals remained alive and did not die from any cause throughout the observation period. Similarly, “free of cancer mortality” indicates that individuals did not die from cancer during the follow-up. “Number at risk” refers to the number of individuals who are still at risk of experiencing the event (all-cause mortality or cancer-specific mortality in our analysis) at a particular time point. Therefore, subjects had event or completed the follow-up will be eliminated from the group of “Number at risk”. Because our subjects were enrolled from different circle of NHANES survey, the follow-up time for subjects from different circles should be different. Subjects enrolled between 1999–2000 had the longest follow-up time (average 216.75 months), while those from 2005–2006 had shortest follow-up time (average 159.48 months). Accordingly, the values of number at risk showed a significant decease after 150 months of follow-up in every quartile. Only 1 subject in the 2nd quartile of IBI reached the line of 250 months. Therefore, Number at risk in this point should be 1 in the 2nd quartile and 0 in other quartiles.

The results of the Cox proportional hazards model were summarized in Table 2. Proportional hazards assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals. The global test and all covariate-specific tests yielded p-values > 0.05, indicating that the proportional hazards assumption was not violated. For the all-cause mortality, the total mortality rate was 23.48% (3483 death), and the incidence was 15.57 per 1000 person-years. From IBI quartile 1 to quartile 4, the mortality rate and incidence increased gradually. In the crude model, each SD increase of IBI could cast an additional 46.8% risk of all-cause mortality. After adjusting for age, sex, race, current smoking and drinking conditions, and PIR, the additional risk from each SD increase of IBI diminished to 27.6%. With further adjustment of BMI, WC, TC, triglycerides, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer morbidity, the risk further reduced to 23.4% for each SD increase of IBI. After dividing IBI into quartiles, the top quartile had a 1.555 times risk of all-cause mortality than the bottom quartile, and the risk increasing trend was significant across quartiles (P for trend < 0.001). Similar results were also observed when set cancer-caused mortality as outcome. The overall cancer-caused mortality was 5.24% (778 death), with an incidence of 3.48 per 1000 person-years. The mortality and incidence also increased from quartile 1 to quartile 4. Noticeably, the mortality and incidence were only marginally different between quartile 2 and 3. In the Cox model, the risk increment for each SD increase of IBI was 34.8% in the crude model. In model 1, the risk increase reduced to 17.8%; and in the fully adjusted model, the risk further minimized to 14.1%. In the quartile analysis, the 4th quartile had a 1.295 times risk of cancer-caused mortality than the 1st quartile, and the increasing trend was also significant (P for trend = 0.017). After excluding subjects with existed cancer (n = 1211), the association between IBI and cancer mortality was also significant and similar to the results in Table 2 (Table S1). Moreover, results from the Fine-Gray competing risk models (Table S2) were consistent with those from the Cox regression. The direction and magnitude of the associations remained similar, suggesting that the impact of competing risks (non-cancer deaths) on the estimated effect of IBI on cancer mortality was limited. Furthermore, smooth curve fitting analysis confirmed the linear increasing trend of the mortality risk (Fig. 3); after excluding covariate (WC) with potential collinearity issue (Table S3 and S4), the results of smooth curve fitting remained consistent (Figure S2). The risk of mortality increased linearly with the rise in IBI levels. The fitness statistics of generalized additive models were summarized in Table S5.

Smooth curve fitting of the association between IBI and the risk of incident mortality. Smooth curve fitting was performed through the generalized additive model with the adjustment of age, sex, race, current smoking, current drinking, PIR, BMI, WC, TC, triglycerides, Scr, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer morbidity. Panel (A) Linear association between IBI and the risk of all-cause mortality; Panel (B) Linear association between IBI and the risk of cancer-caused mortality. Abbreviations: IBI: inflammatory burden index; BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; TC: total cholesterol; Scr: serum creatinine.

ROC and reclassification analysis supported the value of IBI in predicting mortality (Table 3). Regarding all-cause mortality, the AUC of IBI alone was 0.708 (95% CI: 0.701–0.716, P < 0.001), when adding IBI into conventional risk factors (including age, sex, race, current smoking, current drinking, PIR, BMI, WC, TC, triglycerides, Scr, hypertension, diabetes, cancer morbidity), the AUC of the whole model significantly improved ( 0.807 vs. 0.808, P for comparison = 0.012). Furthermore, the continuous NRI (0.200, 95% CI: 0.167–0.234, P < 0.001) and IDI (0.003, 95% CI: 0.002–0.005, P < 0.001) also confirmed the value of IBI in refining the prediction of all-cause mortality. Considering cancer-caused mortality, the AUC of IBI alone was 0.632 (95% CI: 0.625–0.640, P < 0.001), and the predicting ability of the whole model also enhanced when introducing IBI into conventional risk factors (AUC: 0.791 vs. 0.799, P for comparison < 0.001). Moreover, the continuous NRI (0.138, 95% CI: 0.103–0.279, P < 0.001) and IDI (0.008, 95% CI: 0.005–0.010, P < 0.001) also demonstrated the usefulness of IBI in predicting cancer-caused mortality.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that higher IBI levels were significantly and linearly associated with increased risks of both all-cause and cancer-specific mortality in a nationally representative U.S. population. After adjustment for a comprehensive set of demographic, clinical, and laboratory variables, each SD increase in IBI was associated with a 23.4% increase in all-cause mortality and a 14.1% increase in cancer-specific mortality. Although IBI alone showed limited predictive ability, its inclusion alongside traditional risk factors significantly improved mortality risk prediction, as confirmed by both ROC and reclassification analyses. These findings highlight the potential value of IBI as a complementary biomarker to enhance mortality risk stratification in the general population.

Our results were consistent with several published studies. In the pilot study of IBI, Xie et al. constructed IBI, their data showed that the risk of mortality increased along with the elevation of IBI level in a cancer population17. Later, another study revealed that a higher IBI is independently associated with death and other related outcomes in patients with non-small cell lung carcinoma20. Simultaneously, a research letter published by Ding et al. enrolled 103 patients with locally advanced gastric cancer22; With a median follow-up period was 75.5 months, the results displayed that IBI successfully predicted overall survival and progression-free survival in these patients, providing a solid external validation for IBI. Recently, He et al. further discovered a linear and positive association between IBI and all-cause mortality among 8827 American subjects aged over 45 years21. Our findings were in strong agreement with previous studies that have examined the prognostic role of the IBI. In our analysis of a large, nationally representative American adult cohort, we found that elevation of IBI level was associated with significant increases in both all-cause mortality and cancer-specific mortality, even after adjusting for demographic, clinical, and laboratory variables. These results align with those reported by Xie et al. and He et al., who observed linear associations between IBI and mortality risk in cancer patients and in older adults from the general population, respectively17,21. Furthermore, our findings regarding the predictive value of IBI for mortality risk are consistent with those reported by Ding et al. In their study involving patients with locally advanced gastric cancer, IBI significantly improved the prediction of both overall survival and progression-free survival22. Similarly, our analysis demonstrated that incorporating IBI alongside traditional risk factors enhanced the predictive performance for both all-cause and cancer-specific mortality in the general population, thereby supporting IBI as a valuable addition to existing mortality risk prediction models. In summary, our findings are consistent with prior studies, confirming the linear association between IBI and mortality risk, and further demonstrating that IBI enhances mortality prediction when added to traditional risk models.

Inflammation promotes cancer formation and progression through several inter-related mechanisms23,24. First, persistent inflammatory signaling drives genomic instability: reactive oxygen and nitrogen species released by activated neutrophils and macrophages induce oxidative DNA lesions and error-prone repair, thereby accelerating the accumulation of oncogenic mutations25,26. Second, pro-inflammatory transcription factors—chiefly NF-κB and STAT3—remain chronically active in inflamed tissues, up-regulating cyclins and anti-apoptotic proteins, which foster unrestrained proliferation and resistance to cell death27,28. Third, tumor-associated macrophages promote tumor angiogenesis by releasing pro-angiogenic factors and matrix metalloproteinases, thereby facilitating neovascularization and ensuring nutrient supply and metastatic potential29. Fourth, inflammation reshapes host immunity in favor of tumor immune evasion through signaling pathways like transforming growth factor-β30,31. A high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio—reflected in IBI—reflects expansion of pro-tumor neutrophils and depletion or dysfunction of cytotoxic T and NK cells, weakening immune surveillance. Fifth, inflammation serves as an incubator for the tumor microenvironment. For instance, myeloid-derived H2O2 stimulates cancer cells to secrete tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which subsequently enhances the release of pro-inflammatory and carcinogenic factors. As a result, the tumor and the immune system create a feedback loop that promotes cancer progression32. These mechanisms help explain the association between elevated IBI and increased cancer mortality. IBI reflects both systemic inflammation (CRP) and immune imbalance (neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio), which drive tumor progression via genomic instability, angiogenesis, and immune evasion. These processes are reinforced by cytokine-mediated feedback loops and immunosuppressive cells, further promoting a hostile tumor microenvironment. Thus, higher IBI levels indicate a pro-tumor inflammatory state, supporting its role as a biologically meaningful predictor of cancer-related mortality.

Our study still has some novelties compared to previous studies. First, previous studies mainly studied the value of IBI in cancer population, but our study was conducted based on a general population. Second, published related studies focused on the association between IBI and mortality, while our current analysis further assessed the clinical value of IBI by employing ROC and reclassification analysis, and the results supported the potential clinical usefulness of IBI, especially in the primary care conditions. Third, compared to Ding et al.’s work21our study based on a more general adult population without age restriction, thereby broaden the applicable condition of IBI; Furthermore, our study also revealed a significant association between IBI and cancer-specific mortality in addition to the association with all-cause mortality in the general population. Overall, our findings showed similarities with established articles, but also provided new evidence to broaden the clinical utility of IBI, especially in the primary care conditions.

This study offers important insights into the association between the IBI and mortality, especially cancer-specific mortality, highlighting its potential utility in cancer risk stratification. Chronic inflammation plays a key role in cancer progression and prognosis, and IBI—by integrating C-reactive protein and the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio—offers a simple, cost-effective proxy for systemic inflammation and immune imbalance. As a readily available biomarker derived from routine blood tests, IBI could be feasibly incorporated into clinical risk assessments, particularly in primary care setting where early identification of high-risk individuals is critical. Integrating IBI into standard screening protocols may support earlier identification of people at elevated risk of cancer-related mortality, enabling more personalized follow-up strategies, closer monitoring, and timely referral to oncology services. However, while our findings support the use of IBI as a prognostic marker for cancer mortality, it is important to acknowledge its limitations. As an indirect, non-specific indicator of inflammation, IBI may be influenced by a variety of non-malignant conditions, such as infections, autoimmune diseases, or metabolic disorders, which could confound its interpretation. Therefore, over-reliance on IBI in isolation may lead to unnecessary anxiety or interventions. Instead, IBI should be viewed as an adjunctive tool that complements existing risk stratification methods, helping to identify individuals who may benefit from more comprehensive clinical evaluation or targeted surveillance.

The study has several limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. First, the data were sourced from the NHANES database, which utilized a cross-sectional design. Researchers from the American CDC linked the survey data to the national death index database for follow-up on mortality; However, this linkage process may introduce some information bias. Thus, further validation through new cohort studies is needed. Second, the findings are based on the American population, and it remains uncertain whether the conclusions are applicable to individuals from different geographical and socioeconomic backgrounds, which requires additional research. Finally, like other observational studies, some variables may have been omitted, potentially biasing the results. The current study examined the relationship between IBI and all-cause and cancer-caused mortality risk, but unidentified confounders, such as cancer type and healthcare access, could also impact this risk. Therefore, conclusions should be drawn cautiously, and future studies with more comprehensive data collection are necessary to validate these findings.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article is available from the corresponding authors on appropriate request. All the data could be downloaded from the NHANES official website (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/ContinuousNhanes/Default.aspx?BeginYear=1999).

References

Bray, F., Laversanne, M., Weiderpass, E. & Soerjomataram, I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer 127, 3029–3030. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.33587 (2021).

WHO. Global Health Estimates. Deaths by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2019. (2020). https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortalityandglobalhealthestimates/gheleadingcausesofdeath (2020).

Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 71, 209–249. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21660 (2021).

Qian, S., Golubnitschaja, O. & Zhan, X. Chronic inflammation: Key player and biomarker-set to predict and prevent cancer development and progression based on individualized patient profiles. Epma J. 10, 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13167-019-00194-x (2019).

Afify, S. M., Hassan, G., Seno, A. & Seno, M. Cancer-inducing niche: The force of chronic inflammation. Br. J. Cancer 127, 193–201. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01775-w (2022).

Colotta, F., Allavena, P., Sica, A., Garlanda, C. & Mantovani, A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: Links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis 30, 1073–1081. https://doi.org/10.1093/carcin/bgp127 (2009).

Li, Z., Zheng, Z., Ruan, J., Li, Z. & Tzeng, C. M. Chronic inflammation links cancer and parkinson’s disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 8, 126. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2016.00126 (2016).

Ritter, B. & Greten, F. R. Modulating inflammation for cancer therapy. J. Exp. Med. 216, 1234–1243. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20181739 (2019).

Cupp, M. A. et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and cancer prognosis: An umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. BMC Med. 18, 360. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01817-1 (2020).

Tian, C., Song, W., Tian, X. & Sun, Y. Prognostic significance of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in patients with ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 48, e12917. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12917 (2018).

Tan, S. et al. Prognostic value of inflammatory markers NLR, PLR, and LMR in gastric cancer patients treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Front. Immunol. 15, 1408700. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2024.1408700 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Hs-CRP and all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality risk: A meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 259, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.02.003 (2017).

Li, W. et al. Systemic immune inflammation index with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A meta-analysis. Inflamm. Res. 73, 2199–2216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-024-01959-5 (2024).

Zhang, S. & Cheng, T. Prognostic and clinicopathological value of systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) in patients with breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 56, 2337729. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2024.2337729 (2024).

Diem, S. et al. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte ratio (PLR) as prognostic markers in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with nivolumab. Lung Cancer 111, 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.07.024 (2017).

Miyamoto, R. et al. The neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) predicts short-term and long-term outcomes in gastric cancer patients. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 44, 607–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2018.02.003 (2018).

Xie, H. et al. Inflammatory burden as a prognostic biomarker for cancer. Clin. Nutr. 41, 1236–1243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2022.04.019 (2022).

McEvoy, J. W. et al. 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 45, 3912–4018. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae178 (2024).

ElSayed, N. A. et al. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: Standards of care in diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care 46, S19–S40. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc23-S002 (2023)

Xie, H. et al. The inflammatory burden index is a superior systemic inflammation biomarker for the prognosis of non-small cell lung cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 14, 869–878. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.13199 (2023).

He, C. et al. Association between inflammatory burden index and all-cause mortality in the general population aged over 45 years: Data from NHANES 2005–2017. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 34, 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.numecd.2023.10.006 (2024).

Ding, P. et al. The inflammatory burden index: A promising prognostic predictor in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. Clin. Nutr. 42, 247–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2023.01.005 (2023).

Fernandes, Q. et al. Chronic inflammation and cancer; the two sides of a coin. Life Sci. 338, 122390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2023.122390 (2024).

Sohrab, S. S. et al. Chronic inflammation’s transformation to cancer: A nanotherapeutic paradigm. Molecules 28 https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules28114413 (2023).

Canli, Ö. et al. Myeloid cell-derived reactive oxygen species induce epithelial mutagenesis. Cancer Cell. 32, 869–883. .e865 (2017).

Kay, J., Thadhani, E., Samson, L. & Engelward, B. Inflammation-induced DNA damage, mutations and cancer. DNA Repair. (Amst) 83, 102673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102673 (2019).

Zhao, H. et al. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal. Transduct. Target. Ther. 6, 263. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-021-00658-5 (2021).

Bharadwaj, U., Kasembeli, M. M., Robinson, P. & Tweardy, D. J. Targeting Janus kinases and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 to treat inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer: Rationale, progress, and caution. Pharmacol. Rev. 72, 486–526. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.119.018440 (2020).

Fu, L. Q. et al. The roles of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor angiogenesis and metastasis. Cell. Immunol. 353, 104119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellimm.2020.104119 (2020).

Tauriello, D. V. F., Sancho, E. & Batlle, E. Overcoming TGFβ-mediated immune evasion in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 22, 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-021-00413-6 (2022).

Nihira, N. T., Kudo, R. & Ohta, T. Inflammation and tumor immune escape in response to DNA damage. Semin Cancer Biol. 110, 36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2025.02.005 (2025).

Denk, D. & Greten, F. R. Inflammation: the incubator of the tumor microenvironment. Trends Cancer 8, 901–914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trecan.2022.07.002 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the NHANES participants, staff, and investigators.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L. designed the current study. D.Z. and W.L. integrated and analyzed the data. D.Z. and W.L. drafted the manuscript. W.L. revised the manuscript according to reviewers’ comments. W.L. revised the manuscript and proofread it for publication. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The NCHS institutional Ethics Review Board approved the study design of NHANES; an additional Ethics Review for the current study is unnecessary. All methods were carried out in accordance with the NHANES analysis guideline. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Zhao, D. & Li, W. Inflammatory burden index predicts long term mortality in a nationally representative population from NHANES. Sci Rep 15, 25034 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09574-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09574-y

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association between the inflammatory burden index and erectile dysfunction: a cross-sectional study based on NHANES 2001–2004

Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition (2025)