Abstract

For locally advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), the combination of cisplatin plus gemcitabine (CisGem) is the standard first-line treatment. However, the outcome remains unsatisfied with the median overall survival (OS) of 11.7 months. We aimed to compare the effect of CisGem regimen and hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) with Folfox 4 for locally advanced ICC. 97 Locally advanced ICC patients treated by CisGem regimen or HAIC with Folfox 4 in our institution from 2017 to 2019 were studied as training group. 43 locally advanced ICCs receiving CisGem chemotherapy or HAIC with Folfox 4 were investigated as validation group. The median OS was 14.5 months among 37 ICC patients from the HAIC group and 10.3 months among 60 ICC cases in the CisGem group. The median PFS in the HAIC group was 8.2 months in contrast to 5.3 months in the CisGem group. Additionally, objective response rate (ORR) in the HAIC group was markedly better than one in the CisGem group (29.7% v 5.0%). Patients from the HAIC group suffered from less AE (particularly 3–4 grade AE) than those in the CisGem group. The prediction nomogram models for OS and PFS were built respectively after Cox multivariate analysis, which were confirmed to be clinically useful by external validation cohort. These data here suggested HAIC with Folfox 4 was a potential first-line treatment option for local advanced ICC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), which was an anatomic subtype of cholangiocarcinoma arises from the intrahepatic bile ducts, is a highly lethal liver neoplasm1. The National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program database reported that the incidence rate of ICC was 0.95 cases per 100,000 adults in the United States2. More ICC patients were diagnosed at the advanced stage than extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ECC) because of the lack of symptoms and the overall outcome was unfavorable in contrast to ECC3. Currently, hepatic resection with the goal to achieve negative-margin (R0) resections is the only curative modality with the 5-year OS rate of 25-31%4,5. However, the relapse rate after radical surgery remains high between 42% and 70%6,7. And most patients were diagnosed at the advanced stage who were not suitable to receive the curative surgery8. For ICC patients with adequate performance status at the advanced stage, cisplatin and gemcitabine (CisGem) have been considered as the current first-line standard treatment due to the favorable survival benefit shown in the ABC-02 clinical trial9. The patients recruited in the ABC-02 trial included intra- or extra-hepatic cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder or ampullary carcinoma, which leaded to determine the effect of CisGem on ICC. Although CisGem therapy leaded to an improved overall survival, the benefit was not obvious which was about 2–3 months (median survival 11.7 in CisGem group vs. 8.3 months in Gemcitabine monotherapy group)4.

Because of limited effect of systemic chemotherapy for advanced ICC, there is growing interest in locoregional treatment. Most of ICC lesion is confined to liver, hence, locoregional therapy, intra-arterial therapy (IAT) particularly, is potential therapy option for unresectable ICC. For unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma patients, several clinical investigation showed the favorable survival benefit over best supportive treatment9,10. Although there are several studies reported about IAT on unresectable ICC which showed well tolerated by ICC patients, the type of IAT used in these studies was different, including TAE, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE)11, drug-eluding bead TACE (DEB-TACE)12 and Yttrium-90 radioembolization13,14, and overall survival from these investigation was similar with CisGem group in the ABC-02 trial.

Recently, hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with Folfox (HAIC-Folfox) regimen showed the satisfied clinical efficacy on unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients15,16,17,18. Due to absence of satisfied treatment option, unresectable ICC patients at our center were given two alternative: CisGem systemic chemotherapy (on days 1 and 8 every 3 weeks) or HAIC-Folfox 4 treatment (every 3 to 4 weeks). Here, we showed the comparable results of two treatments in terms of efficacy and adverse effect on unresectable ICC patients without extrahepatic metastases.

Methods

Patients and eligibility criteria

This is non-randomized controlled trial which was approved by the institutional review board of the First Hospital of Xian Jiaotong University (XJTU1AF2016LSL-034) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 as revised in 1983. This study was also registered at http://www.chictr.org.cn/index.aspx (ChiCTR-INR-17010977). Between August 1, 2017 and October 1, 2019, 163 consecutive unresectable ICC patients treated at our institution were recruited. All patients were informed the details of the HAIC procedures, especially about the uncertain benefits and complication risks associated with HAIC, and the therapeutic effect and AE of the current standard therapy option (CisGem) for unresectable ICC patients. Clinical decision was made together by clinical experts and patients. All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. ICC was diagnosed based on histopathological findings by percutaneous liver biopsy guided by ultrasound. All patients received PET examination in order to exclude the metastatic liver cancer from other organs for example gastrointestinal cancer.

The eligibility criteria for inclusion was listed here: (1) age 18–75 years old; (2) Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Score (ECOG-PS) 0–1; (3) histologically confirmed ICC unsuitable for curative resection without extrahepatic tumor metastases; (4) bi-dimensionally measurable liver lesions; (5) no previous treatment for ICC; (6) estimated life expectancy of more than 3 months; (7) total bilirubin ≤ 30 mmol/L, and serum albumin ≥ 32 g/L; (8) platelet count ≥ 75,000/µL, leukocyte count ≥ 3000/uL; (9) the absence of cirrhosis or the cirrhotic status of Child–Pugh class A only; (10) Complete medical and follow-up data. Patients were excluded from the study according to the following criteria: (1) distant metastasis; (2) patients with severe underlying cardiac or renal diseases who were unsuitable HAIC treatment; (3) complete follow-up data were unavailable; (4) any previous treatment for other cancer; (5) accompanied by other primary malignancy.

Treatment protocol

For the patients from the CisGem group, each cycle comprised cisplatin (25 mg/m2 of body-surface area) which was followed by gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2), each administered on day 1 and 8 every 21 days, initially for 4 cycles. For patents from the HAIC group, femoral artery puncture was conducted using Seldinger’s technique and catheterization was performed routinely. A 5 French RH catheter and 2.6 French microcatheter were both used in HAIC. After microcatheter was inserted into the tumor-feeding hepatic artery under the guidance of digital subtraction angiography, the following regimen was carried out through the microcatheter: oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 for 2 hours; leucovorin 200 mg/m2 for 2 hours; fluorouracil, 400 mg/m2 for 2 hours day 1 and day 2; and fluorouracil, 600 mg/m2 for 22 h day 1 and day 2. After HAIC was completed, RH catheter and microcatheter were removed and no implanted port system was used. The HAIC therapy regimen was carried out on a tri-weekly basis. The criteria for dose reduction and delay/discontinuation of treatment are listed in the Supplementary Table 1.

Follow-up and survival assessment

All patients received the follow-up evaluation at the start of every cycle including physical examination, monitoring of symptoms, adverse events, CEA, CA199, and laboratory test. Tumor response was assessed by contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance examination (MR) according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor 1.1 criteria (RECIST 1.1) every 6 weeks (2 cycles). Once the diagnosis of the progressive illness was made, the subsequent treatment was administered and the follow-up interviews persisted. The primary endpoint of this trial was to measure overall survival (OS), which was calculated from the date of HAIC or CisGem treatment to the date of death from any cause. The secondary endpoints were progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR) and disease control rate (DCR). PFS was defined as the time from the first HAIC or CisGem treatment to either liver cancer lesion progression or progression of lymph-node metastases or distant organ metastases. The metastases of lymph-node was defined as enlarged lymph-node with the minimum diameter larger than 15 mm as detected by contrast-enhanced CT or MR. ORR was defined as the percentage of patients diagnosed with complete response (CR) or partial response (PR). DCR was defined as the percentage of CR, PR and SD. Adverse events were classified according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) version 5.019. The final follow-up visit was taken in January 15, 2021.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS software (version 13.0) and GraphPad Prism 8.0 were used for statistical analysis. Categorical variables was analyzed by χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Quantitative variables are described as median with interquartile range and were compared by Student’s t test (for continuous variable) or nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test for skewed values. Time-to-event variables were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and were compared by log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were carried out to determine factors related with survival outcomes. Factors with the P value less than 0.05 in the univariate analysis were analyzed by the multivariate analysis. A two-sided P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Sangerbox platform’s tools (http://sangerbox.com/home.html) were employed to develop a Nomogram-based predictive model, with subsequent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis for model validation.

Results

Patient characteristics

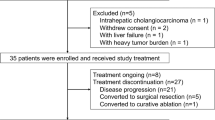

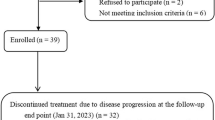

We assessed the eligibility of 163 patients with unresectable ICC who received either CisGem or HAIC treatment. Among them, 12 had received previous treatment for ICC and 25 suffered from ICC distant metastases. 6 had severe cardiac diseases who were not suitable to receive HAIC treatment and 2 were accompanied by other primary malignancy. Additionally, 21 were lost to follow-up. There was a total of 97 eligible patients included in this study based according to inclusion/exclusion criteria (Fig. 1).

The baseline demographics and the clinical characteristics data of these patients recruited were comparable between the two groups (Table 1). The patients in CisGem group had worse performance status and less total bilirubin in blood serum compared to those in HAIC group. The baseline of other demographic and disease characteristics were well-balanced between the both groups. Curative resection was performed for 3 ICC patients (8.1%) in HAIC group, whereas 2 ICC patients (3.3%) in CisGem group underwent surgical resection (P = 0.366).

Antitumor activity

The patients in the HAIC group had better median OS of 14.5 months (95% CI, 0.805 to 2.461) than 10.3 months (95% CI, 0.406 to 1.242) for those from CisGem group (HR 0.503 [95% CI, 0.299 to 0.846]; P = 0.013; Fig. 2A). The OS rates at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months were 97.3%, 59.5%, 10.8% and 2.7% in HAIC group, and 96.7%, 28.3%, 5% and 1.7% in CisGem group, respectively. Patients in HAIC group had a significantly longer median PFS (8.2 months; 95% CI, 0.881 to 2.718) than those in CisGem group (5.3 months; 95% CI, 0.368 to 1.135; HR 0.463 [95% CI, 0.278 to 0.773]; P = 0.005, Fig. 2B).

The subgroup analyses to determine OS and PFS were performed and the results were shown in Figs. 3 and 4. HAIC showed a significant clinical benefit on OS for patients with one of the following features: male, ECOG status of 0, Child-Pugh A class liver function, no liver cirrhosis, multiple liver tumor lesion, maximum tumor diameter of more than 5 cm, lymph node metastasis, higher serum CA199 level, higher NLR and lower PLR (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4). HAIC treatment appeared to specifically increase overall survival of ICC patients with Child-Pugh A class liver function or no liver cirrhosis (Supplementary Fig. 2A and B). As shown in Supplementary Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8, in the subgroup study, HAIC treatment was found to provide a clinical benefit on PFS for ICC patients with age less than 50 years old, male, ECOG status of 0, Child-Pugh A class liver function, no liver cirrhosis, multiple liver tumor lesion, maximum tumor diameter of more than 5 cm, lymph node metastasis, higher serum CA199 level, higher serum CEA level, lower NLR and higher PLR.

The results of univariate analysis for OS were listed in Table 2. Multivariate survival analysis about over-all survival showed that favorable independent risk factors of survival were no liver cirrhosis, single liver tumor lesion, tumor size of less than 5 cm, no lymph node metastasis and HAIC treatment. And we also built diagnostic nomogram for predicting OS of ICC based on the results of multivariate survival analysis Fig. 5A. ROC (receiver operating characteristic) analysis displayed that the one-year AUC (area under curve) of this diagnostic nomogram reached 0.85 (95% CI: 0.93 to 0.77, Fig. 5B). The one-year AUC of the validation cohort was 0.960 (95% CI: 1.00 to 0.91, Fig. 6A). For external validation cohort, patients were divided into low risk group (lower nomogram score) and high risk group (higher nomogram score) using the median nomogram score (155) as the cut-off value. As shown in Fig. 6B, patients from the low risk group had the better OS than those from the high risk group (P = 0.002; HR = 0.342, 95%CI (0.157–0.744)), which showed the good predictive performance of OS nomogram model for locally advanced ICC patients.

A diagnostic nomogram for predicting OS of ICC in study cohort based on the results of multivariate survival analysis; B ROC (receiver operating characteristic) curves of the diagnostic nomogram for predicting OS of ICC in study cohort; C diagnostic nomogram for predicting PFS of ICC in study cohort based on the results of multivariate survival analysis; D ROC curves of the diagnostic nomogram for predicting PFS of ICC in study cohort.

A ROC curves of this diagnostic nomogram for predicting OS of ICC in the validation cohort; B Kaplan-Meier Curves for OS of both the low risk group and high risk group from the validation cohort divided by the OS-related diagnostic nomogram model; C ROC curves of this diagnostic nomogram for predicting PFS of ICC in the validation cohort; D Kaplan-Meier Curves for PFS of both the low risk group and high risk group from the validation cohort divided by the PFS-related diagnostic nomogram model.

Table 3 showed that univariate and multivariate analysis about PFS. Multivariate survival analysis revealed favorable independent risk factors for PFS were male, tumor size of less than 5 cm, no lymph node metastasis, and HAIC. Figure 5C showed the nomogram for predicting PFS of ICC based on the results of multivariate survival analysis with the 6-month AUCs of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.91 to 0.74, Fig. 5D). The 6-month AUC of the PFS-prediction model was 0.89 (95% CI: 1.00 to 0.77, Fig. 6C). We also divided the patients in external validation cohort into low risk group (low score) and high risk group (high score) using the media nomogram score (220) as the cut-off value. The PFS of ICC patients from the low risk group was significantly better than those from the high risk group (P < 0.001; HR = 0.327, 95%CI (0.164–0.651), Fig. 6D). These also supported that the PFS-prediction model for locally advanced ICC patients had the good performance.

The tumor responses of ICC patients were presented in Table 4. On the basis of RECIST 1.1, ICC patients in the HAIC group achieved a higher ORR (29.7% v 5.0%, Χ2 = 11.3, P < 0.001) than those in the CisGem group. And DCR in HAIC group seemed higher than that in CisGem group, although no significant difference was found in both group (P = 0.632).

Safety

The incidence of treatment-related adverse event (TRAE) was 89.2% in HAIC group and 91.7% in CisGem, which was not significantly different (P = 0.683). More serious adverse events (Grade 3 and 4, SAE) were observed in CisGem group (61.7%) than in HAIC group (40.5%, P = 0.043). Among them, the frequencies of grade 3–4 fatigue, leukopenia, Thrombocytopenia, elevated ALT, and hypoalbuminemia were significantly higher in CisGem group than in HAIC group (Table 5). Notably, more abdominal pain was found in HAIC group when oxaliplatin was injected (Grade 1 + 2, 51.4%; Grade 3 + 4, 16.2%), and the abdominal pain was relieved by injecting 200 mg lidocaine. Hence, in this study, there was no abdominal pain related dose reduction or interruption found in HAIC group.

Significantly more dose reductions were found in CisGem group than in HAIC group (P < 0.001, Supplementary Table 1), which could be caused by more SAE in CisGem group. The frequencies of treatment delay of HAIC group (35.1%) seemed higher than those in CisGem group (26.7%). There was more treatment discontinuation in HAIC group than CisGem group (16.2% vs. 0, P = 0.001).

Discussion

ICC is the second most common malignant liver tumor which accounts for about 3% of gastrointestinal cancers20. Because that only 20 − 30% of ICC patients received curative-intent operation systemic chemotherapy is the most common therapeutic option for ICC patients21. Recent studies have identified several key genomic alterations that have prognostic and therapeutic implications. For instance, mutations in TP53, KRAS, CDKN2A/B, and ARID1A are commonly observed across BTC subtypes, with TP53 and KRAS mutations associated with significantly poorer overall survival (OS)4. On the other hand, FGFR mutations, predominantly found in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), have a positive prognostic association and serve as potential therapeutic targets. FGFR2 rearrangements, in particular, are considered to define a unique molecular subtype of cholangiocarcinoma and are mutually exclusive with IDH mutations. IDH1/2 mutations are also frequently detected in ICC and can influence treatment strategies, such as the use of IDH inhibitors22. Understanding these molecular features is crucial for advancing personalized medicine in BTC and improving patient outcomes. Based on ABC-02 clinical trial reported in 20109, CisGem regimen has been considered as the preferred first-line therapy for advanced ICC patients with 11.7 months of OS. In this study, we reported the primary data from open-label, parallel-group phase II trial of HAIC (Folfox 4 regimen) versus CisGem treatment for locally advanced ICC patients (liver-confined and unresectable). As the first-line therapy, HAIC-Folfox 4 displayed a notable improvement in OS, tumor treatment response, and PFS which also had fewer AE compared with CisGem. Additionally, we built an effective nomogram model to predict the outcome of locally advances ICC.

Several local treatments have been performed for locally advanced ICC patients including transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), transarterial radioembolization (TARE), thermal ablation, and external-beam radiotherapy. Because of dual blood supply of the liver, TACE has been considered as the favorable therapy choice for unresectable malignant liver tumor. But there was controversy on TACE for ICC. The previous studies using cisplatin, doxorubicin, mitomycin, irinotecan, or a combination of these agents showed ORRs ranging from 10 − 50%23,24,25,26. Y-90 selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT), also called as TARE was also used popular locoregional therapy for unresectable ICC. The preliminary studies showed that SIRT got an ORR between 6% and 50% and the median OS with 29 months, and facilitated downstaging to resection27,28,29. Additionally, combination SIRT and CisGem chemotherapy was found to have favorable anti-tumor effect as first-line treatment of advanced ICC patients and get a high ratio of downstaging to surgical intervention in a phase 2 trial30. However, ICC is not the indication of Y-90 indication in China.

Due to liver’s dual blood supply, HAIC delivers high doses of chemotherapeutic agents to liver cancer preferentially with limited damage to liver tissues. The study showed that chemotherapy administered by hepatic artery directly got drug concentrations in the liver that were 400-fold higher than those by systemic administration31. Because the liver clears the chemotherapy via first-pass metabolism, chemotherapy by HAIC diminishes systemic toxic effects. Hepatic artery infusion pump chemotherapy in advanced ICC was reported by several previous studies, which showed good therapeutic effect32,33. In this study, we compared the treatment effect and adverse effect of between HAIC-Folox 4 and systemic CisGem chemotherapy for locally advanced ICC patients. It was found here that the ORR per RECIST 1.1 of the HAIC group was more than five times that of the CisGem group (29.7% vs. 5.0%). The median OS of patients from the HAIC group was 14.5 months, which was higher than 10.3 months in CisGem group. Similarly, there was a significantly longer median PFS in HAIC group (8.2 months) than those in CisGem group (5.3 months). It indicated that HAIC-Follfox 4 regimen had better anti-tumor effect for locally advanced ICC patients than systemic CisGem chemotherapy. Subgroup analysis of OS and PFS were carried out on the basis of various clinical features. HAIC provided the significant benefit in ICC patients with the following features: male, ECOG status of 0, Child-Pugh A class liver function, no liver cirrhosis, multiple liver tumor lesion, maximum tumor diameter of more than 5 cm, lymph node metastasis, higher serum CA199 level, higher NLR and lower PLR. On PFS, HAIC provided the clinical benefit for ICC patients with age less than 50 years old, male, ECOG status of 0, Child-Pugh A class liver function, no liver cirrhosis, multiple liver tumor lesion, maximum tumor diameter of more than 5 cm, lymph node metastasis, higher serum CA199 level, higher serum CEA level, lower NLR and higher PLR. It indicated that HAIC-Folfox 4 regimen could be more suitable for locally advanced ICC patients with the clinical characteristics mentioned above.

Cox multivariate survival analysis revealed that favorable independent risk factors of OS were no liver cirrhosis, single liver tumor lesion, tumor size of less than 5 cm, no lymph node metastasis and HAIC treatment. Based on these data, we built the nomogram model with the good AUC value to predict the 12-month OS of locally advanced ICC patients via SangerBox internet tool (http://sangerbox.com/home.html). This model was confirmed by the data of the external validation cohort, which showed a good predictive performance. On the same way, we also built the PFS-relevant prediction nomogram model, which was confirmed well by the external validation. These prediction model could help us to predict the outcome of locally advanced ICC before starting treatment.

The rate of TRAE was found no significant difference between HAIC group and CisGem group. However, there were more SAE in CisGem group (61.7%) than in HAIC group (40.5%). In CisGem group, more patients suffered from grade 3–4 fatigue, leukopenia, Thrombocytopenia, elevated ALT, and hypoalbuminemia compared with those in HAIC group. Notably, when oxaliplatin was injected, a considerable percentage of patients suffered from the abdominal pain (Grade 1 + 2, 51.4%; Grade 3 + 4, 16.2%) which was relieved by injecting 200 mg lidocaine immediately. Hence, no patients refused to receive the following HAIC treatment due to abdominal pain, and there was need to reduce the dose of oxaliplatin.

One of the limitations was that this was a non-randomized, open-label, parallel-group phase II trial, which could influenced the accuracy of the results. However, this study showed HAIC-Folfox 4 regimen had the significant advantage on both anti-tumor activity and treatment treatment-related adverse event over traditional systemic CisGem chemotherapy as the first-line therapeutic option. It should be confirmed further by a phase 3 randomized clinical trial with large sample size whether HAIC-Folfox 4 regimen is a better first-line treatment for locally advanced ICC patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BTC:

-

Biliary tract cancer;

- ICC:

-

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma;

- OS:

-

Overall survival;

- PFS:

-

Progression-free survival;

- AE:

-

Adverse events;

- RFA:

-

Radiofrequency ablation;

- TACE:

-

Transcatheter arterial chemotherapy and embolization;

- HAIC:

-

Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy;

- CisGem:

-

Cisplatin plus gemcitabine;

- ECC:

-

Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma;

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma;

- SEER:

-

National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results;

- IAT:

-

Intra-arterial therapy;

- CT:

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography;

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance examination;

- RECIST:

-

Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumor;

- NCI-CTCAE:

-

National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events;

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group;

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen;

- CA-199:

-

Carbohydrate antigen 199;

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase;

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase;

- CR:

-

Complete response;

- PR:

-

Partial response;

- SD:

-

Stable disease;

- PD:

-

Progressive disease;

- DCR:

-

Disease control rate;

- ORR:

-

Objective response rate;

- NLR:

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio;

- PLR:

-

Platelet to lymphocyte ratio;

- TARE:

-

Transarterial radioembolization;

- SIRT:

-

Selective internal radiation therapy;

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic;

- AUC:

-

Area under curve

References

Gad, M. M. et al. Epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma; united States incidence and mortality trends. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 44 (6), 885–893 (2020).

Zhang, H., Yang, T., Wu, M. & Shen, F. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: epidemiology, risk factors, diagnosis and surgical management. Cancer Lett. 379 (2), 198–205 (2016).

Burger, I. et al. Geschwind. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization in unresectable cholangiocarcinoma: initial experience in a single institution. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 16(3):353 –61. (2005).

Bridgewater, J. et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hepatol. 60 (6), 1268–1289 (2014).

Yoh, T. et al. Is surgical resection justified for advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma? Liver Cancer. 5 (4), 280–289 (2016).

John, N. et al. Capecitabine compared with observation in resected biliary tract cancer (bilcap): a randomised, controlled, multicentre, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 20(5):663–673. (2019).

Lamarca, A. et al. Current standards and future perspectives in adjuvant treatment for biliary tract cancers. Cancer Treat. Rev. 84, 101936 (2020).

Tan, J. C., Coburn, N. G., Baxter, N. N., Kiss, A. & Law, C. H. Surgical management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma–a population-based study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 15 (2), 600–608 (2008).

Valle, J. et al. ABC-02 trial investigators. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl. J. Med. 362 (14), 1273–1281 (2010).

Lo, C. M., Ngan, H., Tso, W. K., Liu, C. L. & Lam, C. M. Ronnie Tung-Ping poon, Sheung-Tat fan, John wong. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 35 (5), 1164–1171 (2002).

Niraj, J. et al. Treatment of unresectable cholangiocarcinoma with gemcitabine-based transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (tace): a single-institution experience. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 12 (1), 129–137 (2008).

Jan, B. et al. Fischer. Treatment of unresectable cholangiocarcinoma: conventional transarterial chemoembolization compared with drug eluting bead-transarterial chemoembolization and systemic chemotherapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 24(4):437 – 43. (2012).

Saxena, A., Bester, L., Chua, T. C., Chu, F. C. & Morris, D. L. Yttrium-90 radiotherapy for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a preliminary assessment of this novel treatment option. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 17 (2), 484–491 (2010).

Shoaib Rafi, S. M. et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for unresectable standard-chemorefractory intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: survival, efficacy, and safety study. Cardiovasc. Intervent Radiol. 36 (2), 440–448 (2013).

Kazuomi Ueshima, S. et al. Kengo nagashima, Yoshihiko ooka, Masahiro takita, Masayuki kurosaki, Kazuaki chayama, Shuichi kaneko, Namiki izumi, Naoya kato, Masatoshi kudo, Masao omata. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy versus Sorafenib in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 9 (5), 583–595 (2020).

Li, Q. J. et al. Ming shi. Hepatic arterial infusion of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus transarterial chemoembolization for large hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized phase Iii trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 40 (2), 150–160 (2022).

Ning Lyu, X. et al. Ming zhao. Arterial chemotherapy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil versus Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a biomolecular exploratory, randomized, phase Iii trial (fohaic-1). J. Clin. Oncol. 40 (5), 468–480 (2022).

Abdelmaksoud, A. H. K. et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy in the treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis: a case-control study. Clin. Radiol. 76 (9), 709e1–709e6 (2021).

Freites-Martinez, A., Santana, N., Arias-Santiago, S. & Viera, A. Using the common terminology criteria for adverse events (ctcae - version 5.0) to evaluate the severity of adverse events of anticancer therapies. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl Ed). 112 (1), 90–92 (2021).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72 (1), 7–33 (2022).

Itaru Endo, M. et al. Lawrence schwartz, Nancy kemeny, Eileen o’reilly, Ghassan K Abou-Alfa, Hiroshi shimada, Leslie H blumgart, William R jarnagin. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: rising frequency, improved survival, and determinants of outcome after resection. Ann. Surg. 248 (1), 84–96 (2008).

Woods, E., Le, D., Jakka, B. K. & Manne, A. Changing landscape of systemic therapy in biliary tract cancer. Cancers (Basel). 14 (9), 2137 (2022).

Kim, J. H. et al. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization or chemoinfusion for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: clinical efficacy and factors influencing outcomes. Cancer 113 (7), 1614–1622 (2008).

Matthew, V. et al. Chemoembolization of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with cisplatinum, doxorubicin, mitomycin c, ethiodol, and Polyvinyl alcohol: a 2-center study. Cancer 117 (7), 1498–1505 (2011).

Thomas, J. et al. Jörg trojan, Tatjana Gruber-Rouh. Transarterial chemoembolization in the treatment of patients with unresectable cholangiocarcinoma: results and prognostic factors governing treatment success. Int. J. Cancer. 131 (3), 733–740 (2012).

Park, S. Y. et al. Transarterial chemoembolization versus supportive therapy in the palliative treatment of unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin. Radiol. 66 (4), 322–328 (2011).

Mosconi, C. et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for unresectable/recurrent intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a survival, efficacy and safety study. Br. J. Cancer. 115 (3), 297–302 (2016).

Mosconi, C. et al. Update of the Bologna experience in radioembolization of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 22, 15330338231155690 (2023).

Nancy, E. K. et al. 1,, Peter Allen, William R Jarnaginintrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with yttrium-90 radioembolization: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 41(1):120-7. (2015).

Edeline, J. et al. Radioembolization plus chemotherapy for first-line treatment of locally advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 6 (1), 51–59 (2020).

Ensminger, W. D. & Gyves, J. W. Clinical Pharmacology of hepatic arterial chemotherapy. Semin Oncol. 10 (2), 176–182 (1983).

Jarnagin, W. R. et al. Regional chemotherapy for unresectable primary liver cancer: results of a phase Ii clinical trial and assessment of dce-mri as a biomarker of survival. Ann. Oncol. 20 (9), 1589–1595 (2009).

Nancy, E. et al. Peter allen, William R jarnagin. Treating primary liver cancer with hepatic arterial infusion of Floxuridine and dexamethasone: does the addition of systemic bevacizumab improve results? Oncology 80 (3–4), 153–159 (2011).

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Key Clinical Research Project of the First Hospital of Xian Jiaotong University (No.: XJTU1AF-CRF-2016-002).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lin Liu: Investigation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Writing-original draft; Methodology Huanhuan Wang: Data curation; Investigation; Methodology; Project administrationLiang Sun: Data curation; InvestigationYufang Liu: Data curation; InvestigationYujing Zhang: Data curationXutian Wang: Methodology; Project administrationXin Zheng: Conceptualization; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Writing–review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment. This is non-randomized controlled trial which was approved by the institutional review board of the First Hospital of Xian Jiaotong University (Approval number: XJTU1AF2016LSL-034) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of 1975 as revised in 1983. This study was also registered at http://www.chictr.org.cn/index.aspx (ChiCTR-INR-17010977).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Wang, H., Sun, L. et al. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with Folfox 4 regimen versus cisplatin and gemcitabine for locally advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 21588 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09586-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-09586-8