Abstract

The challenge of assessing intracellular accumulation represents a major hurdle to the discovery of new antibiotics with Gram-negative activity. To address this, a high-throughput assay was developed to measure compound uptake and retention in Escherichia coli using LC/MS. 13,056 diverse small molecules were screened with two isogenic E. coli strains, a wild-type and a TolC-deleted mutant. Cell-associated concentrations of 8,410 compounds were determined and 6,416 compounds were classified either as retention-positive or -negative, with 45% (2,885) positives in the TolC mutant. Of these, 60% were not retained in the wild-type strain, indicating efficient efflux. No individual structural feature or physicochemical property explained the retention behavior. Machine learning (ML) models were trained using these results, and a gradient-boosted-tree model using 36 physicochemical compound descriptors proved most accurate. The ML model demonstrated robust performance across similar and dissimilar molecule subsets, showcasing its strong generalization and real-world predictive potential. An experimental validation of the tool was performed with a set of 540 new compounds and correctly predicted retention-positive cases in 77.8% and retention-negative in 74.4%. This assay and prediction tool could enhance Gram-negative antibiotic discovery, aiding in screening library design, computational structure-based drug design, and exploration of chemical space before synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria are spreading globally, rendering existing antibiotics less effective and contributing significantly to infection-related morbidity and mortality. No novel classes of Gram-negative antibiotics have reached the market in recent years, raising concerns about the threat of a “post-antibiotic era” in which many bacterial infections could again become untreatable. Therefore, the need to develop novel classes of antibiotics overcoming contemporary Gram-negative bacteria resistance mechanisms has been recognized by scientists and policymakers1,2,3,4.

Gram-negative bacteria possess powerful mechanisms to prevent potential drugs from reaching their molecular target inside the cell. Compounds need to penetrate an asymmetric outer membrane with a viscous, hydrophilic and charged lipopolysaccharide layer and then cross the hydrophobic cytoplasmic membrane. Navigating these hurdles requires orthogonal molecular properties5. Additionally, compounds are exposed to metabolizing enzymes and must evade efflux pumps that can expel many xenobiotic molecules rapidly from the bacterial cell. (For an overview see6,7,8,9).

Despite a wealth of knowledge about uptake mechanisms, accumulation, efflux, and enzymatic modifications of known antibiotics10,11,12,13, there is a lack of efficient methods to measure intracellular compound levels. The failure to predict uptake and retention parameters from a compound structure a priori, is a major hurdle to Gram-negative compound discovery14,15. More than a decade ago, Lewis called for a revival of high-throughput screening (HTS) for antibiotics using compound collections selected according to uptake potential, noting that the indiscriminate application of the “Lipinsky rules of five”16 had a counterproductive effect on antibiotic drug discovery6.

Bacterial compound uptake is often inferred from the difference between a molecule’s in vitro inhibitory potency and its antibacterial activity, limiting the analysis to compounds with a known molecular target that possess measurable antibiotic activity. Recently, techniques to measure whole-cell accumulation of antibiotics and subcellular localization of compounds have been developed by several groups to address this challenge17,18. Davis and co-authors analyzed the accumulation of salicyl-adenosine compounds in a TolC Escherichia coli mutant using MS quantitation and proposed that “correlations between structural/physicochemical properties and accumulation may vary depending on compound classes”19. However, several authors pointed out the need for a larger, systematic analysis to derive broadly predictive models.

Using accumulation predictions based on uptake measurements of 180 compounds, Richter et al. transformed a known Gram-positive antibiotic into a broad-spectrum antibiotic20. They established the eNTRy rules describing properties of compounds likely to lead to accumulation in Gram-negative bacteria. They proposed that rigid and flat molecules containing an ionizable amine are most suitable for accessing intracellular targets21,22. This approach subsequently led to the discovery of FabI inhibitors with significantly improved activity against Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii23, and the expansion of the spectrum of the riboswitch inhibitor ribocil C to Enterobacteriaceae24. The computational analysis of matched molecular pairs derived from a convenience set was performed in another study to identify motifs to improve antibacterial activity. They identified the addition of primary, amines, thiophenes or aryl chlorides as most promising transformations increasing Gram negative activity25.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa was also used to investigate physicochemical properties that drive the classification into permeators and non-permeators26. Machine-learning (ML) identified 7 descriptors with “non-zero importance” but not any simple molecular descriptors such as those proposed by eNTRy. Moreover, these properties are usually not considered when selecting compounds with “hit/lead-like” structures in screening libraries for mammalian targets27.

For this study, an assay was developed to directly measure small-molecule retention and investigate compound characteristics required for intracellular accumulation in Gram-negative bacteria with a large set of diverse compounds. The cell-associated concentration of compounds was determined independently of antibacterial activity to identify physicochemical determinants governing compound retention. The retention data associated with compound properties was used to train a general ML model to enable the design of improved screening libraries for novel compounds with activity against Gram-negatives.

Results

Development of a bacterial compound retention assay

Previous large screening campaigns indicated that only a small fraction of small molecules could enter Gram-negative bacteria and accumulate by evading efflux pumps28,29. Because of extensive prior work, Escherichia coli was chosen as test organism13,18,22,30,31. Compound retention was measured in a strain lacking the tripartite AcrAB-TolC efflux pump and compared to an isogenic wild-type strain.

Quantification by HPLC coupled to mass spectrometry has been widely used to assess compound retention by bacteria due to intracellular uptake, membrane integration, or extracellular adherence since it was first proposed by Cai32. A direct measurement method was chosen to maximize detection of even weakly retained compounds that do not accumulate intracellularly. Small molecules were quantified from cell lysates after removal of supernatant32, but multiple washing steps were required to remove residual compound in the medium which might lead to re-equilibration due to mechanical membrane disruption or diffusion especially for compounds that do not bind with high-affinity to a cellular target. Existing LC/MS/MS protocols typically require optimized methods and rely on calibration for each compound to achieve quantification with sufficient sensitivity, which is impractical for a large-scale screen. Instead, a single-point calibration was done with a reference sample at one concentration on a qTOF mass analyzer employing generic tuning conditions, and a high density of bacteria was used to increase sensitivity.

Assay optimization

Various assay parameters were optimized to improve the detection of compound retention in E. coli with LC/MS. Although the mechanisms of compound penetration into bacteria and accumulation kinetics are not fully understood, previous data collected for reference compounds suggested that they reach maximum intracellular concentration after approximately 15 min19,32,33,34. The optimal incubation period for compound uptake was evaluated with tetracycline and linezolid as positive controls and atenolol as negative control. While the peak concentration of tetracycline was reached after incubation for 30 min, the level detected after 15 min was already 88% of the peak value, and hence this incubation period was chosen for the assay (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Removing compounds from the incubation buffer or sticking to the cell surface was critical to ensure sensitive detection of compounds retained by E. coli. Using fluorescein as reference, it was determined that 5 consecutive washing steps reduced the concentration in the buffer by 99.96% (Supplementary Fig. S2). Finally, lysis conditions were evaluated and 0.1 M glycine–HCl performed comparably to a commercial lysis kit (Supplementary Fig. S3). The optimized protocol was then used for screening of various sets of compounds.

Classification as bacterial “retention negative” (RN) and “retention positive” (RP)

Atenolol, used as a negative control, was assayed 96 times to calculate the relative compound retention for each replicate. The average relative recovery was 0.31% with a standard deviation of 0.14. Therefore, the threshold for negative compounds was set at 1% of relative retention, calculated from the rounded value of average plus three standard deviations. A peak area of 20 was set as the lower limit of detection for the instrument, and a reference peak area of 2000 was required to allow unambiguous classification of a compound as “Retention Negative” RN (Fig. 1).

Compound classification based on MS signals obtained from peak area in lysate and reference samples. Compounds were classified into four categories based on their MS peak area obtained from bacterial lysate after five washes, relative to their signal in a 250 nM reference solution (relative recovery). Compounds classified as retention positive (RP, green) had a reference peak of at least 500, a lysate peak area in the lysate greater or equal than 100 (lower limit of quantification, LLOQ), and the relative recovery was equal to or greater than 1%. Compounds classified as Retention negative had a reference peak area above 2000 and a relative recovery below 1% (RN, red). Compounds with a signal of less than 500 in the reference sample were classified as “No/Low Detection” (grey). The remaining compounds were classified as Ambiguous (orange). LLOD: Lower limit of detection = 20.

A compound was classified as bacterial “Retention Positive” (RP) with a minimum peak area of 100 (limit of quantification), fivefold above the lower limit of detection, and a relative recovery of ≥ 1% (Fig. 1). To minimize the number of compounds classified as ambiguous, a minimum reference peak area of 500 was deemed acceptable.

The goal was to classify compound retention as a dichotomous outcome. Still, some compounds generated a weak MS signal, or no detectable signal at all. Hence, a zone of ambiguity was defined between the RP and RN areas. Compounds not detected in the reference sample were classified as “No/Low Detection”, and all other compounds as “Ambiguous” (Fig. 1).

The retention assay correctly classifies antibacterial compounds

Since bacterial uptake has only been determined for a small number of compounds using a variety of protocols19,20,26,30, it was not possible to validate the assay described here against a large set of controls. However, one can investigate potential differences between existing antibiotics and other drugs and hypothesize that antibiotics are expected to fall into the RP category more frequently than non-antibiotics.

The validation was performed with two sets of compounds: 140 known antibiotic drugs and 421 non-antibiotic drugs. The experimentally determined bacterial retention classification of the compounds differed significantly between the two sets (Supplementary Tables S1, S2). 84 of 140 antibiotics could be classified using the criteria outlined above and found to be predominantly RP—93% (78/84) in the TolC mutant and 82% (65/79) in the wild-type E. coli strain. In contrast, among the 226 evaluable non-antibiotic drugs, only 56% (127) and 44% (98) were identified as RP in the respective strains. The proportion of retention “ambiguous” and “No/Low Detection” compounds were similar in both sets (Table 1).

There was also a correlation between RP classification and antibacterial activity against a wild-type isolate. The percentage of RP dropped from 93 to 67% for compounds with an MIC of > 8 µg/mL (Table 1). The data suggested that the method could be used to measure retention in bacterial cells, and that most of the known antibiotics are retained in E. coli. While the retention cutoff at 1% of peak area did not discriminate completely against compounds with very weak antibacterial activity, there was a clear trend towards reduced positivity for compounds with MICs of 16 µg/mL or higher further confirming the utility of the method and the protocol for a larger screening campaign.

Large scale screen of chemically diverse compounds

Based on the encouraging data obtained with the focused screen, the study was extended to a large set of ~ 13,000 diverse compounds. With the intention of searching for potential structural determinants of small molecule uptake into bacteria, a diverse library of 11,727 compounds covering a wide chemical space was selected from the in-house screening library (see Material and Methods). One or more electronegative atoms had to be present, the cLogP ≤ 2.5, and the molecular weight between 120 and 600 amu. Additionally, a set of 1,329 macrocyclic and other specialty compounds were also included. This set included also the compounds from the validation experiment, and 46 compounds with antibiotic activity from in-house discovery programs.

Overall, the retention of 13,056 compounds in the TolC mutant E. coli 2350 and the isogenic parent 2122 was experimentally determined and classified according to their relative retention (Table 2). When the TolC mutant 2350 was used, 22% were identified as RP and 27% as RN. 51% compounds were not further evaluated, either because the signal measured in the sample did not reach the limit of quantification (1,995) or there was no signal in the reference sample (1,983) or it was low (2,662).

The observed relative retention values ranged from 0 to 844% with Ec2350 and from 0 to 2886% for Ec2122 (Fig. 2A, B). For many compounds the retention was higher in the TolC strain (Fig. 2C, D). In fact, while 331 compounds exhibited a relative retention of 100% when tested against Ec2350, this was only the case for 69 compounds with the wild-type strain.

Relative compound retention in lysates of compounds classified as RP or RN. Relative recovery is plotted vs. compound number. (A.) Retention in Ec2350. (B.) Retention in Ec2122, plot is only shown up to 800% (i.e., eightfold accumulation) removing 5 compounds with higher relative retention. (C.) Comparison of retention in Ec2122 vs. Ec2350. (D.) Percent compounds within a %-Retention bin are shown for both strains. Distribution is shown in a histogram with the % fraction in bins of 10% relative retention (i.e., first bin contains compounds with a relative retention of 0 to 9.99%). Only bins which contain at least 0.15% of total are shown. Compounds that exhibited antibacterial activity in whole-cell screening (vide infra) are shown as blue dots.

A self-nearest neighbor analysis was performed on the 6,416 compounds classified either as RP or RN to assess the chemical diversity of the set. The Tanimoto similarity of each compound was measured against all other compounds from the same training dataset and the similarity value of its closest neighbor was retained. This technique allows to assess the molecular diversity of a dataset. Most of the compounds were distributed across low Tanimoto values, suggesting a high chemical diversity between the compounds (Supplementary Fig. S6).

45% of classified compounds were retained (RP) in the TolC mutant and 19% in the wild-type strain, indicating the importance of tripartite AcrAB-TolC efflux pump system. The data suggest that the retention assay (i) measured accumulation within the cell, and that (ii) efflux of small molecules is indeed a big obstacle as it led to a 58% reduction in compounds that were retained in E. coli under the experimental conditions used.

High confirmation rates

The assay’s reproducibility was confirmed by re-testing a set of 1′858 compounds classified as RP. The relative compound recovery from lysis buffer in those two independent studies correlated well (Fig. 3A). Most compounds (1′669, 89.8%) were classified again as RP while only 49 compounds (2.6%) previously found RP were RN upon repetition. A small number of compounds (7, 0.4%) were not detected the second time in the reference sample, and some compounds (133, 7.2%) were classified “ambiguous” because the relative recovery or the reference sample peak area did not reach the pre-specified threshold (Fig. 3B).

The assay delivers results with good inter-experimental reproducibility. 1,858 compounds classified as Retention-positive in a primary screen with TolC-mutant E. coli were tested again in a confirmation screen. A, Correlation of compound recovery from lysis buffer relative to the reference solution at 250 nM, as obtained in the primary (y-axis) and confirmation screens (x-axis). The red line indicates 100% correlation. B, 1,669 compounds (89.8%) were confirmed as RP. Of the other compounds, 133 appeared as retention “ambiguous”, 49 as RN, and 7 were assigned the “No Detection” label.

Taken together, these results indicated that the assay was robust and suitable for large-scale compound screening.

Low false negative classification rate in an antibacterial whole-cell screen

To be useful in guiding antibacterial drug discovery, a bacterial compound retention assay must yield a low rate of false RN classifications. Growth inhibitory antibiotic activity had been assessed in-house as part of a high-throughput screen against MDR isolates of K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii and a wt P. aeruginosa strain (unpublished data). The inhibition data was used to define a dichotomous classifier (> 50% growth inhibition at 25 µM: Yes/No) to evaluate the correlation of retention data with antibiotic activity.

As indicated in Table 2, only 3 of growth-inhibiting compounds were classified as RN in E. coli Ec2350 (11% for the wt strain), while 96 of those compounds classified as RP were among those with antibiotic activity. Hence, in this simulation of a “typical” industrial whole-cell antibiotic drug discovery screen, none of the novel hits would have been missed by the a priori removal of RN compounds.

No predictive structural or physicochemical compound property for retention

Next, a comprehensive set of physicochemical properties was calculated for the compounds that had been experimentally classified as RP and RN, and their distribution was compared between the two sets (Fig. 4). Although differences could be observed in the distribution of some individual properties, none of these appeared to predict bacterial retention on their own. Moreover, no apparent differences could be observed when comparing RP compounds identified with Ec2350 and Ec2122, either (Supplementary Fig. S7).

No isolated physicochemical property determines bacterial retention. 18 physicochemical properties of 6416 experimentally screened compounds classified as RP (green) or RN (red). Values are displayed as violin plots including a box plot with the median. The y-axis indicates the index for each property, the width of each class shows the number of compounds per index. Note: compounds missing an acidic or basic pKa were not shown in the specific plot. The values on the y-axis of the violin plots are treated as continuous variables for display, even if they are actually discrete numbers. Data plotted with R 4.4.0.

The correlations between all physicochemical properties were investigated and displayed in a correlation plot for both RP (Fig. 5A) and RN (Fig. 5B). Obvious correlations were observed within each set, for example between the molecular weight and the total surface area or basic nitrogen counts with basicity, but no correlations were uncovered that significantly differentiated the two sets. Also, no clusters of correlated variables were observed, indicating that every single variable represented non-redundant, potentially useful information that might be exploited by machine-learning (ML) models.

Correlation of 18 physicochemical properties. Property correlations of all compounds experimentally classified as either bacterial retention positive (RP, A) or retention negative (RN, B). Pearson correlation between individual physicochemical property descriptors: increasing Pearson correlation with increasing marker size and intensity. Blue shades indicate a positive correlation; red shades indicate a negative correlation.

A computational machine-learning model for retention prediction

Given that no key physicochemical parameters correlated with the RP/RN classification, ML models were developed to investigate non-obvious relationships without the need to understand the underlying causal mechanisms. To that end, the training dataset representing the 6,416 compounds was exposed to Supervised ML Classification algorithms.

Molecular Access System (MACCS) keys, capturing 2D molecular structure fingerprints were used as a bit vector that codifies the presence or absence of different substructural features in each bit position35. Additionally, 43 physicochemical properties were calculated for each chemical structure. The 36 most important properties (Supplementary Fig. S13, Supplementary Table S3) were employed for model assessment.

Random 10% subsets of the training data were used to assess each algorithm in a tenfold cross validation method (Supplementary data and Supplementary Fig. S8).

Two Gradient Boosted Trees (GBT) models achieved ~ 75% prediction accuracies. The GBT algorithm using only physicochemical properties performed slightly better in predicting true RP compounds (sensitivity of 75.30% vs. 74.80%; Supplementary Fig. S9). The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC AUC) was 0.87 on the test data (Supplementary Fig. S10) and was selected.

Model validation of the GBT&A1 model (Supplementary methods) using tenfold cross-validation with target shuffling36 revealed that the mean prediction error increased 2.3-fold from 19.9% with real training data to 46% with dummy data. The latter was obtained by shuffling the experimentally determined compound retention classification data column, thus breaking the connection of the outcome variable with the compound descriptors (Supplementary Fig. S11). The model achieved a prediction accuracy of 80.1% for the retention of small molecules by Gram-negative bacteria.

A Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) confirmed the robust performance. LOOCV offers the advantage of generating a prediction for each molecule in the dataset, thereby providing a comprehensive evaluation of model performance. Subsequently, the performance of the ML model for subsets of the 1,000 most similar and the 1,000 most dissimilar molecules according to the diversity assessment described earlier were assessed separately. For the similar set, the model achieved a ROC AUC of 0.87 and minimized false-negative predictions (accuracy 0.80, sensitivity 0.82, and specificity 0.77). For the dissimilar set, the model yielded a ROC AUC of 0.87 and reduced false-positive predictions (accuracy 0.77, sensitivity 0.70, and specificity 0.85). These results indicate strong overall performance across both subsets, and underscore the model’s ability to generalize effectively, demonstrating robust predictive performance not only on data closely resembling the training set but also on more diverse and previously unseen data. Such versatility highlights the potential of the model to make accurate predictions in real-world applications.

The model was applied to 287,154 molecules of the Idorsia screening library. For each prediction, the model also provided a level of confidence (LoC, value between 0 to 1). To validate the predictions, 540 library compounds evenly distributed across confidence levels strata (< 0.6, 0.6–07, 0.7–0.8, 0.8–0.9, and 0.9–1) were then randomly chosen and compound retention experimentally tested in Ec2350. One half of the selected compounds were predicted -positive and the other half predicted -negative. 435 (80%) could be experimentally classified either as RP (212 compounds, 39%) or RN (223, 41%) in the retention assay. 105 compounds (20%) were “Ambiguous”, including 33 compounds with low reference signals.

Among the 213 compounds predicted as negative, 166 compounds (78%) were true negatives. Among the 222 predicted as positive, 165 compounds (74%) were true positives. Overall, the model’s prediction accuracy was 76.1%, consistent with the cross-validation results (Fig. 6). Prediction accuracy strongly correlated with the LoC of the predictions, exceeding 90% for confidence levels > 0.8. Below a LoC of 0.6, predictions became unreliable, with accuracy dropping below 50% (Fig. 6C-E). These trends could be observed for both prediction-positive and -negative compounds.

Three out of four compounds were correctly predicted by the ML model and the prediction accuracy increased with the level of confidence. 540 compounds predicted as either positive or negative were submitted to experimental confirmation. Retention data was obtained for 435 compounds.. A, Categorization of all compounds according to their predicted and experimental classifications. B, Percentage distribution of those 435 compounds into the four statistical categories. False Negative, predicted negative but experimentally positive; False Positive, predicted positive but experimentally negative; True Positive, predicted positive and experimentally positive; True Negative, predicted negative, experimentally negative. Percentages indicate Negative Predictive Value (77.9%), False Omission Rate (22.1%), Positive Predictive Value (74.2%) and False Discovery Rate (25.8%). The mean accuracy was 75.9%. The compounds were also selected to evenly distribute into bins according to the level of confidence of their classification prediction. C, All correctly predicted compounds were categorized as “True”, incorrectly predicted compounds as “False”. Prediction accuracy represents the ratio of the sum of “True” compounds divided by all compounds. D, all positive predicted compounds. Prediction sensitivity represents the ratio of “True” positives compounds divided by the sum of “True” and “False” positives. E, all negative predicted compounds. Prediction specificity represents the ratio of “True” negative compounds divided by the sum of “True” and “False” negatives. Calculations were performed separately for the compounds in each LoC bin.

Application of the ML retention model to HTS-driven antibacterial discovery

364 compounds with growth inhibitory antibiotic activity, which did not originate from antibacterial programs or were designated as bona-fide antibiotics, had been identified in the HTS campaign in-house against three Gram-negative species. The 0.13% hit rate (364/287,154) increased when only compounds with higher prediction-positive probability score were considered (Supplementary Fig. S12), demonstrating that applying the ML model could enhance hit finding. It is important to understand that setting a ML positive class threshold will automatically decrease the number of both positive and negative compounds and many compounds will be excluded. For instance, retention of only 43,661 compounds can be predicted with a positive class probability threshold of 0.95 (Supplementary Fig. S12). Applying a very high probability threshold of 0.964 would allow to pick about 10% of the original screening set (about 28,000 compounds) and with a hit rate of 0.36 is expected to yield about 100 hits. Prospectively, this ML model could be used as a tool to filter and cherry pick compounds from a diverse screening library to accelerate antibacterial discovery.

Discussion

The discovery of new antibacterial compounds active against Gram-negative bacteria is challenging. Identifying a suitable target that is part of an essential pathway is difficult, and success rates of transforming good inhibitors into antibacterial compounds has been notoriously low26,37. However, the availability of sensitive label-free detection methods to determine the concentration of small molecules, including those that do not have any antibacterial activity using high-throughput mass spectroscopy, allow the assessment of compound accumulation inside cells38 and may provide valuable insight into structural and physicochemical properties important for retention39.

Responding to the recognized need to measure, understand, and predict which compounds can reach pharmaceutical targets in Escherichia coli, this study introduces an efficient method to experimentally determine and computationally predict bacterial compound retention. The protocol was designed for a high-throughput workflow and to identify compounds that interact with bacteria and are retained in any of the subcellular compartments even at low concentrations. The compound concentration was measured directly after removal of supernatant, short washes, and lysis of the cells. The LC/MS method was not tuned for each compound maintaining compatibility with large compound screens.

A large screen of small molecules spanning a wide chemical space beyond antibiotics was conducted to identify structural features important for compound uptake into Gram-negative bacteria. More than 6,400 compounds could be classified either as retention-positive (RP) or retention-negative (RN). The data analysis revealed that no single physicochemical property or structural feature explained compound retention in efflux-deficient E.coli. However, a machine learning (ML) approach using a Gradient Boosted Trees model revealed that a significant amount of information determining bacterial retention is contained in the combined values of these properties. The top-ranked variables were basic pKa, non-H atoms, and cLogS, but all the other parameters also contributed to the prediction (Supplementary Fig. S13). The model performed well in cross-validation with a sensitivity of 75.3% and specificity of 84%.

In a study with P. aeruginosa, ML analyses of permeators and non-permeators also suggested that a combination of multiple descriptors contributed to the outcome, highlighting that good permeation cannot be described by a single physicochemical property26.

This contrasts with other studies that had identified single features as important. Richter et al.20, identified the presence of an amine, amphiphilicity, structural rigidity, and low globularity as important for compound accumulation in wild-type bacteria. Others found that compounds with Gram-negative activity have smaller size, lower lipophilicity and a zwitterionic state. O’Shea and Moser, in their seminal work, analyzed known antibiotics systematically and concluded that compounds with Gram-negative activity occupied a distinct physicochemical property space with molecular weight MW below 600 Da, increased polarity with significantly lower cLogD7.4 (−2.8), and larger polar surface area (PSA, 165) as important factors40. Researchers from AstraZeneca published that, based on data from more than 20 high-throughput screening campaigns, HTS actives were significantly more hydrophobic than antibacterial project compounds with a higher average clogD and that compounds with low efflux were generally either small and polar, or large and zwitterionic41.

The discrepancies between this study’s findings and previous research may stem from differences in the types of compounds analyzed. Richter focused on compounds that accumulate to high levels in cells with efflux pumps, and many of the previous studies analyzed known antibiotics. In contrast, the present study examined lead-like structures27 and classified compounds as RP even if they did not accumulate to high levels, or were still subject to efflux.

Physicochemical property rules could accelerate optimization especially if they are driven by specific structural motifs, such as the addition of primary amines, as they can be easily implemented23,24,42. Still, the attempt to optimize existing antibiotics using the eNTRy rules have not always been successful, there is no guarantee that Gram-negative active compounds can be identified43,44, or novel scaffolds emerge for optimization45.

An important application of the ML predictions is to guide the design of antibiotic screening compound libraries by excluding “Negative” compounds and enriching with compounds that are more likely to be retained in Gram-negative bacteria. A retrospective analysis of a whole-cell antibacterial screen using three Gram-negative species showed that applying the prediction tool could have reduced the screen by 90%, still identifying 100 hits, thus focusing more quickly on promising starting points. Unfortunately, the learning could not be applied in-house as Idorsia discontinued antibacterial small-molecule discovery programs.

The study used an efflux pump-deficient E. coli TolC mutant in the primary screen to identify compounds that can permeate into bacterial cells. When tested against a wild-type strain, 59% of retention-positive compounds were no longer retained. Some earlier studies focusing on compounds with antibacterial activity had identified either the percentage of carbon atoms that are SP3 hybridized (Fsp3)13, hydrophobicity together with Fsp3 and molecular stability46, or the fractional polar surface area and molecular weight47 as distinguishing properties. Surprisingly, the physicochemical properties of compounds analyzed here appeared not to differ with different efflux propensity (Supplementary Fig. S6), reflecting the fact that no single physicochemical property was found to drive uptake and retention in Gram-negative bacteria.

Despite its success, the method has several limitations. Frozen/thawed cells were used, and the resulting mechanical weakening of the outer membrane could result in increased retention. The protocol measured retention after 15 min and privileged entry mechanisms such as siderophore-mediated uptake or the use of porins were not investigated. Leus and colleagues had pointed out that several antibiotics exhibited slow kinetics of accumulation and that especially in P. aeruginosa the outer membrane barrier seemed to play an important role13. Additionally, 51% of the compounds screened could not be classified as either retention-positive or retention-negative. Several factors potentially contributed to this failure. Firstly, compound solution quality control was not performed as part of this screen and therefore some DMSO solutions might have been of low quality despite regular quality assurance efforts to ensure that compound purity of the solutions is above 85% (determined by UV absorption at 214 nm). Secondly, some of the compounds could have precipitated upon dilution in aqueous buffer or been modified or degraded during the incubation or lysis steps. It would also have been preferrable to perform parameter tuning to optimize detection and reach maximum sensitivity in mass spectrometry. Using a more selective and optimized method of detection (LC/MS/MS) might have significantly reduced the number of unclassified compounds, but it was deemed impractical in context of a high-throughput screen. Further, the low threshold value for the retention-positive class, may result in overestimating retention as only a small fraction of compounds actually accumulated intracellularly.

Finally, some compounds may stick to the bacterial surface or interact with cell membranes in such a way that they cannot be dissociated through the wash procedure, giving potentially rise to compounds with false-positive retention signals. Even compounds that reach intracellular compartments might not be able to interact with relevant targets as was proposed to explain the lack of correlation between cellular retention and antibacterial activity when assessing ligase inhibitors30. Based on our observations and in agreement with others42, it is very unlikely that a single mechanism drives small-molecule uptake and retention in all relevant species given the different compositions of outer membrane porin systems and efflux pumps, or that “privileged” mechanisms could drive uptake or target engagement47.

Overall, this study offers a valuable approach to address the challenge of discovering new antibiotics for Gram-negative bacteria. It provides a comprehensive, mechanism-independent ML model-based tool that can be used to predict compound retention and guide screening efforts. Future work should focus on evaluating an optimized library of diverse compounds with a high probability of retention improving the chances of discovering novel antibiotic classes.

Material and methods

Bacterial strains and growth

E. coli strain 2122 is derived from E. coli MG1655. It contains resistance cassettes for ampicillin, chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, rifampicin, streptomycin, streptothricin, and tetracycline, but is “wild type” regarding efflux pump genes. (K-12 ilvG rfb−50 rph1 rpsL150 gyrA83 araC..cat rpoB(rifR) ydiON::Tn10 bglA::sat1 bglFB::shv5). E. coli strain 2350 is a TolC mutant (tolC::kan) of strain 2122.

E. coli from a frozen glycerol stock was plated on LB broth agar without selection and grown overnight at 37 °C. A single colony was used to inoculate 2L of LB broth (Luria/Miller, Carl Roth GmbH & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany). The culture was incubated while shaking at 220 rpm at 37 °C until the end of the logarithmic growth phase. 10% (v/v) of glycerol was then added to the culture and the suspension was aliquoted, centrifuged at 2704 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The bacteria pellets were stored at −80 °C until use.

Compounds

Compounds were selected from the high-throughput screening library of Actelion (now Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd). This collection, which is continuously updated, consists largely of catalog compounds purchased from commercial sources, including Enamine, ChemDiv, Chembridge, Asinex and VitasMLab. It also contains specialty collections from internal and external sources which are not commercially available. Although proprietary, this compound collection can be considered fairly representative of modern industrial screening libraries, with a focus on mammalian targets27.

Inclusion criteria restrict the physicochemical and structural properties to the desired hit- and “lead-like chemical space” for the bulk of the collection. These criteria are not applied to some sections of the library, such as macrocyclic and natural compounds. For this study, 13′000 compounds were chosen as a maximally diverse set of compounds from this library to cover the widest chemical space possible.

All compounds were dissolved at 10 or 4 mM in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, United States) and stored at −20 °C under nitrogen. Compounds were further diluted in DMSO, and equal volumes were added to each assay per well.

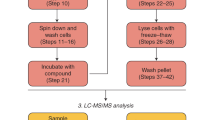

Bacterial compound retention assay

The assay procedure is outlined in Supplementary Fig. S5. The freeze/thawed bacteria pellet was resuspended in 15 mL of incubation buffer (0.9% (w/v) NaCl, 1% (w/v) glucose, 0.5% (v/v) glycerol) to a density corresponding to OD600 of 50. 100µL of bacteria suspension was transferred into each well of a polypropylene 96-well plate (Greiner Bio-One International GmbH). In a control experiment it was confirmed that freeze/thawing did not impact the metabolic activity of the bacterial cultures (Supplementary Fig. S1). Then, 100µL of each test compound diluted to 20 µM in incubation buffer was added and incubated for 15 min at room temperature to allow for uptake. Therefore, each well contained compounds at 10 µM in a volume of 200 µL of bacterial cell suspension corresponding an OD600 of 25. Each screening plate included both positive and negative in-plate controls. Tetracycline (positive control) and Atenolol (negative control) were each incubated with bacteria eight times on each plate, following the procedure described above.

Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 4 °C (3 min at 1′882 g). The supernatant was discarded, and bacteria resuspended in 600µL of ice-cold wash buffer (0.9% (w/v) NaCl, 0.5% (v/v) glycerol).

The wash procedure was repeated 4 times at 4 °C as quickly as possible to minimize compound depletion during washing. After the final spin, the bacteria suspensions were transferred into a fresh 96 well plate and spun once more (3 min at 4 °C at 1,882 g). 80µL of “wash 5” supernatant was kept for later LC/MS analysis.

Bacteria were then resuspended in 200 µL of lysis buffer (0.1 M glycine (w/v), 0.1 M HCl). Several lysis buffers were evaluated using ciprofloxacin as reference compound (Supplementary Fig. S3) and incubated 4 h at RT. Cell debris were removed by centrifugation at RT (10 min at 3,345 g) and 60 µL of the cleared lysate transferred to the LC/MS plate for quantification. In parallel, a second compound sample was prepared at 250 nM in lysis buffer as detection reference.

LC/MS compound measurement

Chromatographic separation and detection were performed using a UPLC coupled to a qTof Synapt G2 mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization (ESI) interface (Waters, Mildford, MA, USA). The UPLC system consisted of an autosampler, binary pumps and a column oven. The column used was an Acquity HSS T3 C18, 2.1 mm I.D., 50 mm length, 1.8 µm particle size (Waters). The HPLC mobile phase A was formic acid in water (0.1%) and mobile phase B was formic acid in acetonitrile (0.1%) The separation was done using a linear gradient from 2 to 95% B over 1.4 min and held at 95% B for 0.4 min before re-equilibration to the initial conditions. The flow rate was 0.6 mL/min and the column was kept at 60 °C. Data was acquired in sensitivity mode, the capillary voltage was set to 2 kV, sampling cone voltage to 25 V, extraction cone to 5 V, and source temperature to 150 °C. A MS/MS scan was performed at 6.66 Hz using sample list MASS_A as precursor ion, but no collision energy was applied to keep the molecular ion intact.

To account for the different MS detection efficiencies of every compound tested, the signal obtained from a sample of the bacterial lysate was calibrated against that of a reference sample of the same compound at a single concentration, incubated without bacteria. Based on a test with 96 random compounds spiked into bacteria lysate in lysis buffer a positive matrix effect of an average of 60% was observed. The concentration was fixed arbitrarily at 250 nM, which is about twice the expected concentration in the lysate if a compound present at 10 µM during the incubation reaches the same concentration in the bacteria but does not accumulate.

The concentration for a compound that passively diffuses into bacterial cells until equilibrium is reached (i.e., no accumulation occurs) was estimated based on the expected concentration found in the lysate assuming that the cell volume of E. coli is 1 µm3 and that there are 1.25*1010 cells/mL at OD600 of 2532. Assuming complete compound recovery upon lysis, a compound concentration of 123 nM in the lysis buffer could be expected.

10 µL of both lysate and reference samples were injected consecutively. Peak areas were calculated after integration. The MS response was assumed to be linear to dose at low compound concentrations. A peak area of 20 was defined as lower limit of detection for these experiments The ratio of lysate sample peak area versus reference sample peak area was reported as “relative recovery” (% Ret).

Prediction of compound retention based on machine learning

Software and algorithms

The open-source software KNIME Analytics Platform (Zurich, Switzerland) was used to evaluate and create supervised ML models. The selected predictive model was based on Gradient Boosted Trees48 using physicochemical properties as input.

The calculation of 43 physicochemical properties of compounds was performed with an in-house developed Knime node based on OpenChemLib (publicly available from https://github.com/Actelion/openchemlib-knime) and the RDKit Descriptor Calculation node. LogD, acidic pKa and basic pKa calculations required a Chemaxon license. They can be estimated with OpenChemLib Knime nodes or the opensource software DataWarrior. The list of properties used as variables for the model and the calculated data for all classified compounds used to train the model is shown in Supplementary Table S3.

k-fold cross-validation

Based on the experimental data obtained with the compounds from our screening library, 6,416 compounds were sorted into two output classes:“retention positive”(RP) and“retention negative”(RN). Input data were physicochemical properties and structure fingerprints. Input and output were paired and presented to the supervised ML learning model.

Validation of the model was performed by using a k-fold cross-validation protocol. The data set was randomly divided into k subsets, and the holdout method was repeated k times. Each time, one of the k subsets was used as the test set and the other k-1 subsets were put together to form a training set. Then the average error or accuracy across all k trials was computed.

Leave-one-out cross validation

Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV) is a cross-validation technique where a single sample is excluded from the training set, and the remaining samples are used to train the model. This process is repeated for each sample in the dataset, with the model’s performance assessed based on its ability to predict the excluded sample.

Test set

540 compounds not previously tested in the retention assay were randomly chosen from the in-house collection to determine the predictive performance of the ML model described. Retention in E. coli was measured, 435 could be classified and the experimentally obtained values were compared with those predicted by the model.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Wernli, D. et al. Antimicrobial resistance: The complex challenge of measurement to inform policy and the public. PLoS Med 14, e1002378. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002378 (2017).

O’Neill, J., Resistance, R. o. A. & Trust, W. Tackling Drug-resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. (Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, 2016).

Council of the European Union. Council Recommendation on stepping up EU actions to combat antimicrobial resistance in a One Health approach 2023/C 220/01. Off. J. Eu. Union 220, 20 (2023).

World Health Organization. in WHO strategic and operational priorities to address drug-resistant bacterial infections in the human health sector, 2025–2035 EB154 8 (2024).

Kakoullis, L., Papachristodoulou, E., Chra, P. & Panos, G. Mechanisms of Antibiotic Resistance in Important Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Pathogens and Novel Antibiotic Solutions. Antibiotics (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10040415 (2021).

Lewis, K. Platforms for antibiotic discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 12, 371–387. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3975 (2013).

Nikaido, H. Prevention of drug access to bacterial targets: permeability barriers and active efflux. Science 264, 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.8153625 (1994).

Masi, M., Refregiers, M., Pos, K. M. & Pages, J. M. Mechanisms of envelope permeability and antibiotic influx and efflux in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17001. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.1 (2017).

Pandey, D., Kumari, B., Singhal, N. & Kumar, M. BacEffluxPred: A two-tier system to predict and categorize bacterial efflux mediated antibiotic resistance proteins. Sci. Rep. 10, 9287. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65981-3 (2020).

Pages, J. M., James, C. E. & Winterhalter, M. The porin and the permeating antibiotic: A selective diffusion barrier in Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6, 893–903. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1994 (2008).

Nikaido, H. & Pages, J. M. Broad-specificity efflux pumps and their role in multidrug resistance of Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 36, 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00290.x (2012).

Du, D., van Veen, H. W., Murakami, S., Pos, K. M. & Luisi, B. F. Structure, mechanism and cooperation of bacterial multidrug transporters. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 33, 76–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbi.2015.07.015 (2015).

Leus, I. V. et al. Functional diversity of gram-negative permeability barriers reflected in antibacterial activities and intracellular accumulation of antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 67, e0137722. https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.01377-22 (2023).

Prajapati, J. D., Kleinekathofer, U. & Winterhalter, M. How to enter a bacterium: Bacterial porins and the permeation of antibiotics. Chem. Rev. 121, 5158–5192. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c01213 (2021).

Silver, L. L. A Gestalt approach to Gram-negative entry. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 24, 6379–6389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bmc.2016.06.044 (2016).

Lipinski, C. A. Lead- and drug-like compounds: The rule-of-five revolution. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 1, 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ddtec.2004.11.007 (2004).

Cama, J., Henney, A. M. & Winterhalter, M. Breaching the barrier: Quantifying antibiotic permeability across gram-negative bacterial membranes. J. Mol. Biol. 431, 3531–3546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2019.03.031 (2019).

Prochnow, H. et al. Subcellular quantification of uptake in gram-negative bacteria. Anal. Chem. 91, 1863–1872. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.8b03586 (2019).

Davis, T. D., Gerry, C. J. & Tan, D. S. General platform for systematic quantitative evaluation of small-molecule permeability in bacteria. ACS Chem. Biol. 9, 2535–2544. https://doi.org/10.1021/cb5003015 (2014).

Richter, M. F. et al. Predictive compound accumulation rules yield a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Nature 545, 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22308 (2017).

Richter, M. F. & Hergenrother, P. J. The challenge of converting Gram-positive-only compounds into broad-spectrum antibiotics. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1435, 18–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13598 (2019).

Geddes, E. J., Li, Z. & Hergenrother, P. J. An LC-MS/MS assay and complementary web-based tool to quantify and predict compound accumulation in E. coli. Nat. Protoc. 16, 4833–4854. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41596-021-00598-y (2021).

Parker, E. N. et al. Implementation of permeation rules leads to a FabI inhibitor with activity against Gram-negative pathogens. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0604-5 (2020).

Motika, S. E. et al. Gram-Negative antibiotic active through inhibition of an essential riboswitch. J. Am. Chem .Soc. 142, 10856–10862. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.0c04427 (2020).

Gurvic, D., Leach, A. G. & Zachariae, U. Data-driven derivation of molecular substructures that enhance drug activity in gram-negative bacteria. J. Med. Chem. 65, 6088–6099. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c01984 (2022).

Leus, I. V. et al. Property space mapping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa permeability to small molecules. Sci. Rep. 12, 8220. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12376-1 (2022).

Boss, C. et al. The screening compound collection: A key asset for drug discovery. Chimia (Aarau) 71, 667–677. https://doi.org/10.2533/chimia.2017.667 (2017).

Payne, D. J., Gwynn, M. N., Holmes, D. J. & Pompliano, D. L. Drugs for bad bugs: Confronting the challenges of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd2201 (2007).

Tommasi, R., Brown, D. G., Walkup, G. K., Manchester, J. I. & Miller, A. A. ESKAPEing the labyrinth of antibacterial discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 14, 529–542. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4572 (2015).

Iyer, R. et al. Evaluating LC-MS/MS To measure accumulation of compounds within bacteria. ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 1336–1345. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsinfecdis.8b00083 (2018).

Zhao, S. et al. Defining new chemical space for drug penetration into Gram-negative bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 1293–1302. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-020-00674-6 (2020).

Cai, H., Rose, K., Liang, L. H., Dunham, S. & Stover, C. Development of a liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry-based drug accumulation assay in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Anal. Biochem. 385, 321–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ab.2008.10.041 (2009).

Zhou, Y. et al. Thinking outside the “bug”: A unique assay to measure intracellular drug penetration in gram-negative bacteria. Anal. Chem. 87, 3579–3584. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac504880r (2015).

Ferreira, R. J. & Kasson, P. M. Antibiotic uptake across gram-negative outer membranes: Better predictions towards better antibiotics. ACS Infect. Dis. 5, 2096–2104. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00201 (2019).

Vilar, S. et al. Similarity-based modeling in large-scale prediction of drug-drug interactions. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2147–2163. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2014.151 (2014).

Nisbet, R., Miner, G., Yale, K., Elder, J. F. & Peterson, A. F. Handbook of statistical analysis and data mining applications (Academic Press, 2018).

Payne, D. J., Miller, L. F., Findlay, D., Anderson, J. & Marks, L. Time for a change: addressing R&D and commercialization challenges for antibacterials. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 370, 20140086. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0086 (2015).

Gordon, L. J. et al. Direct measurement of intracellular compound concentration by RapidFire mass spectrometry offers insights into cell permeability. J. Biomol. Screen 21, 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087057115604141 (2016).

Six, D. A., Krucker, T. & Leeds, J. A. Advances and challenges in bacterial compound accumulation assays for drug discovery. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 44, 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.05.005 (2018).

O’Shea, R. & Moser, H. E. Physicochemical properties of antibacterial compounds: Implications for drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 51, 2871–2878. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm700967e (2008).

Brown, D. G., May-Dracka, T. L., Gagnon, M. M. & Tommasi, R. Trends and exceptions of physical properties on antibacterial activity for Gram-positive and Gram-negative pathogens. J. Med. Chem. 57, 10144–10161. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm501552x (2014).

Stoorza, A. M. & Duerfeldt, A. S. Guiding the way: Traditional medicinal chemistry inspiration for rational gram-negative drug design. J. Med. Chem. 67, 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c01831 (2024).

Ropponen, H. K. et al. Assessment of the rules related to gaining activity against Gram-negative bacteria. RSC Med. Chem. 12, 593–601. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0md00409j (2021).

Saxena, D. et al. Tackling the outer membrane: Facilitating compound entry into Gram-negative bacterial pathogens. NPJ Antimicrob. Resist. 1, 17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44259-023-00016-1 (2023).

Blasco, B. et al. High-throughput screening of small-molecules libraries identified antibacterials against clinically relevant multidrug-resistant A. baumannii and K. pneumoniae. EBioMedicine 102, 105073. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105073 (2024).

El Zahed, S. S., French, S., Farha, M. A., Kumar, G. & Brown, E. D. Physicochemical and structural parameters contributing to the antibacterial activity and efflux susceptibility of small-molecule inhibitors of escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01925-20 (2021).

Manchester, J. I., Buurman, E. T., Bisacchi, G. S. & McLaughlin, R. E. Molecular determinants of AcrB-mediated bacterial efflux implications for drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 55, 2532–2537. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm201275d (2012).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy function approximation: A gradient boosting machine. Ann. Stat. 29, 1189--1232 (2001).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank João Silva, Raphael Lieberherr and Laksmei Goglia for technical support and are indebted to Modest von Korff for the help with the computational analysis of compound properties and Aengus Mac Sweeney for proofreading the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OP, FLG and DR designed the study and were supervising progress. FLG, JH, LC, GB, GP, RL, GR, OP and DR contributed to the methodology. FLG, LC and GB established and performed the retention screen, the LC–MS data collection and initial data analysis as well as validation. JH developed the ML models. JH and GP performed the ML evaluation and resulting data analysis. FLG, JH, LC, RL, PP, CZ and GR were contributing to data curation and interpretation. FLG, LC, JH, GP and DR were preparing graphs and tables. OP and DR were providing intellectual input and drafted the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors were employees of Idorsia Pharmaceuticals Ltd. at the time the study was performed. FLG, JH GB RL PP, GR and DR own equity of Idorsia.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Le Goff, F., Hazemann, J., Christen, L. et al. Measurement and prediction of small molecule retention by Gram-negative bacteria based on a large-scale LC/MS screen. Sci Rep 15, 25431 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10208-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10208-6