Abstract

The biological role of urate (uric acid) during primate evolution has been unclear ever since it was discovered over 100 years ago that humans have unusually high levels of the small molecule compared to most other mammals. Humans (including all apes) are uncharacteristically susceptible to the build-up of urate because we no longer have a functional uricase enzyme capable of oxidizing this highly insoluble molecule. We have now utilized CRISPR technology to insert functional ancestral uricase into the genome of human liver cells to address recent metabolic hypotheses that our ancestral primates inactivated uricase as a mechanism to increase triglyceride production in response to fructose and/or starvation. Uricase expression is confirmed in both hepatocyte monolayer and spheroid tissue cultures, and its expression reduces intracellular urate levels. The presence of uricase is also shown to prevent an increase in triglyceride production upon cellular uptake of fructose in both culture conditions. Our results make progress that further describes a potential advantageous biological role of urate during primate evolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urate (the biological form of uric acid) is a highly insoluble small molecule that is responsible for gouty arthritis and organ damage (kidney and liver) in humans when its concentration rises above ~ 7.5 mg/dL (450 µM)1. The majority of urate formation results from purine metabolism and the molecule is thus a contributor to the nitrogenous waste pathway. Our inability to oxidize urate into more soluble molecules means we have to modulate its concentration to ensure we balance any potential advantages or disadvantages of having such an elevated amount of the molecule2,3,4. The higher concentration of urate in humans is associated with human disease. High levels of urate (hyperuricemia) are classically associated with gout - where uric acid crystallizes in the distal tissues. These needle-shaped monosodium urate crystals are deposited in avascular tissues (e.g., cartilage, tendons, ligaments). In severe cases, these crystals are deposited in larger central joints and in the parenchyma of organs such as the kidney.

Human’s sensitivity to high urate levels is a result of the uricase gene mutating to become a nonfunctional pseudogene between 29 − 20 million years ago when our ape ancestors originated5. Prior to pseudogenization, the uricase gene was accumulating mutations in a step-wise manner that slowly diminished its enzymatic activity beginning at a period of time that overlapped with the extinction of the dinosaurs6,7. These mutations do not appear to have arisen from neutral evolution because urate transporters also co-evolved to handle the increase in urate concentrations as the uricase gene itself (de)evolved in primates8. The requirement to slowly adapt to urate levels is consistent with our observation that the majority of uricase-knockout mice suffer from hyperuricemia and lethal renal failure within the first year due to rapid and unmanageable levels of urate9,10,11.

Urate has been recognized as a predictive marker for cardiovascular disease, hypertension and renal disease12. One hypothesis suggests that hyperuricemia is benign (and even advantageous) unless associated with gout or kidney stones13. Another more recent hypothesis, however, argues that urate has a causative effect on the particular human diseases it predicts. In the latter hypothesis, hyperuricemia is associated with hypertension, cardiovascular disease, eclampsia, and progressive renal failure12. Along these lines, hyperuricemia occurs in 25–50% of hypertensive patients, and in up to 90% of those with new onset hypertension14. Some studies suggest that high levels of urate confer a risk equivalent to the risk cholesterol poses for cardiovascular events15. Hyperuricemia is also a reported risk factor for the progression of renal disease; over 95% of patients with gout have interstitial renal disease at autopsy16.

Despite urate’s clinical relevance, little is known about the evolution and characteristics of urate metabolism in apes and humans. For instance, was uricase activity abolished within a ‘neutral’ evolutionary scenario? It is clear from the sequences of different ape uricase pseudogenes that the destruction of uricase did not arise as a single event in primates, but rather occurred in parallel in at least two lineages - the great apes and the lesser apes5. The observation that it happened more than once (multiple times in primates, and also in reptiles & birds) suggests that the loss of uricase, and presumably an increase in the concentration of serum urate, may confer a selective advantage in particular cases. Despite gouty arthritis being recorded in early Egyptian records, and despite gout being nicknamed the ‘disease of kings’ by medieval society, modern science has still not confidently assigned a biological role to this molecule17. Uric acid has chemically been characterized as an antioxidant, a prooxidant, a neurostimulant, an immunostimulant, inter alia. Yet, the over-arching biological role of urate is still unknown. Recent work suggests that uricase evolution may support the thrifty gene hypothesis such that an increase of urate levels may have been required to help our ape ancestors convert fructose to fat in order to survive periods of starvation7,12,14,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. This particular hypothesis suggests that some mutations may be advantageous in conditions of food scarcity because the mutations allow the species to survive episodes of famine. Unfortunately, these hypotheses have been difficult to test at the molecular level in the laboratory because the gene is not functional in human cells so gene-knockout technology is not useful. We can now utilize CRISPR-Cas9 methods to genomically insert an ancestral uricase gene into human liver cells in order to express a functional uricase enzyme. The use of liver cells is important because non-ape mammals express uricase in hepatocyte cells (where it localizes to the peroxisomes) and this is the organ where a substantial amount of excess fructose metabolism and fat synthesis occurs28. We characterize both monolayers and spheroids of liver cells expressing uricase in order to understand the biological role of urate in humans. Spheroid development is useful because these structures provide more metabolic information about hepatocytes29,30,31. Spheroid 3D cultures can exhibit limitations in the transfer of metabolites and oxygen to the spheroid core. Therefore, maintaining cell viability and liver-specific functions requires careful consideration of factors such as spheroid size, cell density, and culture duration32,33,34. Despite these challenges, 3D spheroid cultures promote greater cell–cell interactions compared to 2D cultures and form structures that more closely resemble in vivo tissue architecture. Lastly, we show that expression of uricase in these human liver cells eliminates hyperuricemia by lowering uric acid concentrations to safe levels from as high as 10 mg/dL (600 µM).

Results

Genomic insertion of functional ancestral uricase

As a first step to engineer human liver Huh cells containing an active uricase gene via genomic integration, we evaluated the efficiency to insert donor DNA into human AAVS1 safe harbor locus using a CRISPR/Cas9-mediated system35. AAVS1 permits robust expression of transgenes in the PPP1R12C gene without noticeable phenotypic impairments36.

We generated a CRISPR plasmid by cloning the gRNA sequence in the px458 plasmid (Addgene #48138) based on the published literature to target the human AAVS1 locus37. The CRISPR plasmid was designed to generate gRNA, Cas9 protein, GFP (to visually confirm plasmid transfection only, no genomic integration). A Donor plasmid was assembled to carry flanking homology arms that allow homologous recombination (~ 800 bp, Fig. 1)38 to integrate the puromycin-N-acetyltransferase gene (Puro), the Red-fluorescent protein (RFP) gene, and the ancestral uricase gene (AncUOX) separated by ribosome-skipping protein-domains T2A. When a double-stranded break induced by the Cas9 protein is successful, repair via homology-directed repair (HDR) can occur with the Donor DNA being inserted into AAVS1 locus, and subsequent expression of Puro, RFP and AncUOX. The RFP expression allows visualization of potential positive cells using fluorescence microscopy. Transfections were performed in three independent experiments. 72 h post-transfection we detected GFP signal indicating positive expression of the CRISPR plasmid. Cells were exposed to 2 µg/mL of Puromycin to select for the stable clones with Donor integration. The Puro and RFP positive cells were used for further culturing.

Schematic for CRISPR/Cas9 system into human AAVS1 locus. Top: Human AAVS1 locus. Single guide RNA (sgRNA) is indicated above the AAVS1 locus. Center: Donor DNA with 5’ homology arm (HA) and 3’HA, ∼820 bp on each side (dashed lines), splice acceptor sequence, T2A ribosome-skipping sequences, puromycin resistance sequence, Red Fluorescent Protein sequence (RFP), ancestral uricase sequence (AncUOX), and polyA signal. Bottom: Cas9 cleavage at the cut site allows donor DNA to be integrated via homology directed repair (HDR). After HDR the engineered AAVS1 locus is able to expresses Puromycin-resistance protein, RFP, and AncUOX.

To determine the correct integration of Donor DNA, we performed genotyping by PCR and DNA sequencing (data not shown) of wild-type, control cells (expressing only Puro/RFP) and uricase-positive cells (Puro/RFP/AncUOX). The PCR analyses using primers that anneal immediately upstream of the 5’ homology arm and the puromycin gene confirmed the precise genomic insertion of the Donor sequence. Additionally, a separate PCR reaction showed that the donor was correctly integrated at the AAVS1 locus, by using a set of primers that bind to the AncUOX or RFP gene and immediately downstream of the 3’ homology arm (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). PCR reactions were submitted for sequencing (results not showed). Sequencing analysis confirmed the correct junction between regions upstream and downstream of the insert into the AAVS1 locus. We did not identify any new point mutations in the Donor open reading frame (ORF) post-integration into the genome.

To determine whether the new AAVS1 ORF was able to express the AncUOX gene we performed Western blot analysis from the whole lysate of control wild-type and RFP+ cells. Western blot analysis confirmed AncUOX expression at the expected size (~ 35 kDa) only in RFP+ cells, control cells did not show uricase expression. Catalase and actin proteins were used as loading controls and both proteins were identified in all samples (Supplementary Fig. 3).

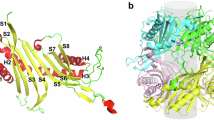

To investigate whether the uricase enzyme was located within peroxisomes, we performed immunofluorescent co-localization analyses. Cells were stained with antibodies specific to either the peroxisomal membrane (PMP70) or uricase (AncUOX). Image overlays demonstrated that AncUOX is appropriately co-localized to peroxisomes (yellow) in Huh cells for both monolayers (Fig. 2a) and spheroids (Fig. 2b). Neither wild-type nor control (Puro+/RFP+) Huh cells showed any uricase localization, confirming the results of the Western blot analyses.

Co-localization studies between AncUOX and peroxisomes. Representative images of nuclei stained with DAPI (blue), peroxisome specific marker, PMP70 (green) and AncUOX (red). Merged images showed co-localization (yellow) after correct integration and expression of Donor DNA into AAVS1 locus. a, Co-localization studies in Huh monolayer. b, Co-localization studies in Huh spheroids. Scale bars are 10 μm for a and 50 μm for b.

Cellular oxidation of uric acid

To evaluate the enzymatic activity of uricase after genomic integration, we exposed the monolayer cells and spheroids to different uric acid concentrations, samples were collected over five days and the oxidation of uric acid was determined using Uric Acid/Uricase Assay kit. Uricase activity was confirmed in cells containing correctly integrated donor sequence but not in control cells (Fig. 3). For monolayers of Huh cells expressing uricase, nearly complete oxidation of uric acid occurs for cells under low exposure (150 and 300 µM) (Fig. 3a, b) and high exposure (450 and 600 µM) (Fig. 3c, d) to uric acid. These results suggest that uricase oxidation occurs more efficiently in liver cells compared to our previous work expressing uricase in kidney cells39.

Determining uric acid concentrations. Cells and spheroids were exposed to different uric acid concentrations. AncUOX positive cells or spheroids were able to oxidize uric acid. Both wild-type and control (Puro/RFP only) cells were unable to oxidize uric acid. a–d, Huh monolayer. e–h, Huh spheroids. Values of uric acid are means ± SEM of three replicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.005.

We next determined the ability of liver spheroids expressing uricase to oxidize uric acid. The spheroids were able to significantly lower uric acid levels for all four concentrations tested (Fig. 3e–h), however these cellular structures were less efficient than the monolayers of cells when given the same amount of time. This presumably is due to limited diffusion of the small molecule throughout the complex spheroid space and appears to be reflected in the decay rate of the uric acid signal between monolayers and spheroids.

Metabolic characterization of human cells expressing uricase

Monolayers and spheroids of Huh cells expressing uricase were metabolically evaluated for uric acid and triglyceride levels either upon exposure to exogenous fructose (20 mM) or under starvation conditions. Results were compared to Huh cells not expressing uricase, either wild-type or control cells Puro+/RFP+.

Figure 4a and c show that exogenous fructose exposure leads to a significant increase in uric acid levels for wild-type and control Huh cells growing in both monolayer and spheroid cultures. However, expression of uricase prevents any significant increase of uric acid levels upon fructose exposure for both types of cultures. Interestingly, spheroid baseline levels of uric acid in cells expressing uricase were lower pre-fructose exposure than the monolayer cultures.

Determination of intracellular uric acid and triglyceride concentrations, and Western blotting analysis after cells and spheroids are exposed to fructose (0 mM or 20 mM) for 72 h. a Intracellular uric acid levels of Huh monolayer. b Intracellular triglyceride levels of Huh monolayer. c Intracellular uric acid levels of Huh spheroids. d Intracellular triglyceride levels of Huh spheroids. Values of uric acid and triglycerides are means ± SEM of three replicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, and ****p < 0.0001. e Representative images of western blotting analysis of protein lysate of Huh monolayer. f Representative images of western blotting analysis of protein lysate of Huh spheroids. AMP kinase (AMPK), Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), phosphorylated protein (p).

We next measured the increase in triglyceride levels after exposure to exogenous fructose. Wild-type and control Huh cells growing in both monolayer and spheroid cultures show significant increases in triglyceride levels (Fig. 4b and d). Conversely, expression of uricase prevents any significant increase in triglyceride levels upon fructose exposure for both types of cultures. Again, spheroid baseline levels of triglycerides in cells expressing uricase were lower pre-fructose exposure than the monolayer cultures.

Westerns were performed for a number of different proteins to confirm expression levels and proteome quality for both monolayers and spheroids (Fig. 4e and f).

To determine how uricase expression can influence cellular starvation, we subjected spheroids to limited metabolic resources. Figure 5 shows that cells expressing uricase have significantly higher cellular levels of both endogenous ATP and triglycerides compared to cells without uricase, and this difference in ATP and triglycerides tracks with lower levels of cellular uric acid in cells expressing uricase.

Determination of intracellular uric acid-, triglyceride-, ATP-levels after spheroid starvation (0, 48 and 72 h), and Western blot analysis. a Intracellular uric acid levels of Huh spheroids. b Intracellular triglycerides levels of Huh spheroids. c Intracellular ATP levels of Huh spheroids. Values of uric acid, triglycerides and ATP are means ± SEM of three replicates. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, and ****p < 0.0001. d Representative images of western blotting analysis of protein lysate of Huh spheroids. AMP kinase (AMPK), Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), phosphorylated protein (p).

Discussion

Our results demonstrate for the first time that HDR-mediated donor integration of recombinant uricase into the AAVS1 locus of human liver cells can be highly specific and efficient. This system has allowed us to address two hypotheses about uricase pseudogenization as it relates to the thrifty hypothesis: (1) a decrease in uricase activity allows cells to increase triglyceride levels when exposed to fructose and (2) a decrease in uricase activity allows cells to better survive starvation conditions18,40,41,42,43,44,45. The results presented above lend support for the first hypothesis but do not yet support the second hypothesis. Why might the first hypothesis be evolutionarily advantageous? Uricase deactivation and urate-transporter re-functionalization were completed simultaneously between 29 − 20 million years ago6,7,8. This coincides with the origins of ape species that were known to have large brains (composed of mostly fat in the form of fatty acids46,47) hypothesized to be based on their frugivorous diets48. It is known that uricase is highly expressed in the liver of most non-ape mammals49,50 and it is known that the liver is where most excess fructose is metabolized and where substantial amounts of fat are synthesized. If our Proconsul ape ancestor required greater fat synthesis from the ingestion of fruit, deactivation of uricase may have been advantageous41,51. However, given that urate can be harmful to a host species, urate transporters and xanthine oxidoreductase may have had to co-evolve in order to ensure urate did not reach high enough levels to precipitate and form insoluble crystals.

It is known that urate inhibits activation of AMPK (by preventing phosphorylation) and that active AMPK is the guardian of mitochondrial biogenesis and stimulates ATP production in HepG2 cells52. Expression of uricase in our Huh cells, however, did not lead to substantially greater pAMPK levels than in wild-type uricase-knockout cells. The immediate metabolic consequences of the difference in cellular ATP and triglycerides is not precisely yet known, however it does suggest that there may be a metabolic cost for the pseudogenization of uricase and thus pseudogenization did not help our ancestors survive starvation19. Additionally, we have subjected our spheroids to excess fructose conditions, and shown that excess fructose increases triglyceride production in uricase-minus cells, while the expression of uricase maintains low levels of cellular triglycerides even when cells are exposed to excess fructose. In the absence of uricase, the increase in triglyceride production tracks with increases in urate levels but a causal relationship has not yet been established53,54. As such, this suggests that pseudogenization of uricase may have had a selective advantage for our frugivorous ancestors.

The biological role of urate in human physiology has historically been difficult to assign. The current study provides some insights into this role, but it cannot definitively rule out other roles as well. Further, we are assaying a single immortalized human cell-line outside the context of both the liver and the whole organism. Primary-cell assays and organismal studies may point to other biological roles. Our results do, however, support the hypothesis that uricase pseudogenization and urate-transporter co-evolution are potentially involved in the ‘thrifty gene hypothesis’12,18,41,55,56,57. While maybe not explicitly responsible for survival during famines, the increase in urate that allows increases in fat synthesis upon excessive fructose ingestion would have been advantageous for developing larger brains given the same amount of nutritional resources as our ancestral monkeys48.

Regardless of the correct evolutionary explanation for why uricase deactivation occurred as apes originated, some humans may directly benefit from our approach. Monolayer and spheroid Huh liver cells expressing uricase were capable of lowering uric acid levels at high concentrations (7.5 mg/dL), which represents early indication of hyperuricemia, and even extremely high concentrations (10 mg/dL), which represents severe hyperuricemia. Patients suffering from hyperuricemia (gout or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease) benefit from therapeutic interventions that lower serum urate, and the repertoire of genes involved in the immune response to hyperuricemia is expanding4. Unfortunately, many patients are not responsive to, or do not tolerate, either xanthine oxidoreductase inhibitors or recombinant uricases58,59,60,61,62. A gene therapy that inserts a functional uricase gene into the liver cells of human patients may be a viable alternative to current therapeutics. This approach would have many benefits: evade the standard immune response seen with recombinant uricases, localizes the uricase enzymatic byproduct of hydrogen peroxide to the peroxisomes where catalase can neutralize the harmful molecule, activity is localized to liver cells, and ensures long-term expression of uricase enzyme. We anticipate that a uricase/CRISPR system such as the one described here can be delivered using the latest lipid nanoparticles that target uptake by hepatocyte cells in liver tissue when injected into blood (for both mice and humans)63,64,65,66,67.

Online methods

Construction of CRISPR and donor vectors

The pX458 plasmid expressing Cas9 protein, gRNA and GFP were purchased from Addgene (#48138) and digested with BbsI enzyme (New England Biolabs)68. AAVS1 target sequence of gRNA oligonucleotides were annealed and cloned into BbsI sites to generate AAVS1 gRNA-CRISPR plasmid. The target sequence of AAVS1 gRNA is identical to our previous work (Supplementary Table 1)37. To generate donor plasmid AAVS1-SA-T2A-Puro-T2A-RFP-T2A-AncUOX-SV40polyA-signal, the sequence for T2A-RFP-T2A-AncUOX-SV40polyA-signal was synthesized by GenScript (Thermo Scientific) as mammalian codon-optimized, and then amplified and cloned into AAVS1-SA-T2A-Puro pA vector (Addgene, #22075) using a Gibson Assembly kit (New England Biolabs). The final donor plasmid was amplified by Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Master Mix (New England Biolabs) and purified by QIAquick PCR Purification kit (QIAGEN). All primers used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 1. We used ancestral uricase An96 from our previous study, but now codon-optimized for human expression in the current study6. This particular ancestral uricase (AncUOX) represents the phylogenetic point immediately prior to the divergence of primates and rodents that occurred ~ 96 million years ago.

Cell culture and transfection

Human hepatocellular carcinoma, Huh-7D 12 cells were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (cat. no. 01042712) and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Corning) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Corning) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Corning). The cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Huh-7D 12 cells were seeded into a 12-well plate to achieve a confluency of 70–80% in the day of transfection. The cells were transfected with TransfeX Reagent (ATCC) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For each transfection, 1.5 µg of AAVS1 gRNA-CRISPR plasmid plus 2.5 µg of donor plasmid in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) plus 10 µL of TransfeX Reagent was gently mixed. The DNA complexes were incubated at room temperature for 15 min and mixed into the wells containing the cells. 5 µM of L755,507 reagent was added in each well. The GFP fluorescence from AAVS1 gRNA-CRISPR plasmid was checked 72 h post-transfection under a microscope. Five days after transfection, cells were selected using 2 µg/mL of Puromycin, cells were monitored each day under the microscope for RFP fluorescence.

Genomic DNA extraction, PCR and Sanger sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (QIAGEN) following the manufacturer’s protocol. To detect and confirm the correct donor integration into the AAVS1 locus, genomic DNA was utilized as a template for PCR using Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Master Mix (New England Biolabs). PCR products were purified with QIAquick Gel Extraction kit (QIAGEN), and sequenced. Gel images were captured using auto exposure and analyzed with a ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad). The whole gel images are shown in Supplementary Information 1.

Spheroid assembly

Huh-7D 12 wild-type and transfected cells were treated with trypsin and then seeded with 5 × 104, 2 × 105 or 1 × 105 cells in a Corning® Elplasia® 96-, 24- or 6-well Black/Clear Round Bottom Ultra-Low Attachment, microcavity plate, respectively. Before seeding the cells, plates were pre-incubated with 50, 500 or 1,000 µL of DMEM per well and centrifuged at 500× g for 2 min, to remove all trapped air and/or bubbles. The plates were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2, and spheroid formation was checked using a microscope. Spheroids were generated between 12 and 15 days. The ½ volume of medium was replaced every 2–3 days with fresh media to maintain healthy cultures.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

1 × 105 Huh-7D 12 wild-type and transfected cells were seeded into 24-well plates under glass coverslips. SelectaFX Alexa Fluor 488 Peroxisome Labeling Kit (Invitrogen, Molecular Probes) following manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, to determine the co-localization of peroxisomes and AncUOX cells were fixed, permeabilized, blocked and stained with anti-peroxisomal membrane protein 70 (PMP70) and Alexa Fluor 488. Cells were rinsed and stained with anti-uricase antibody (sc-166070, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo Fisher). DAPI was used to stain the nuclei.

Spheroids were transferred 1.5 mL microcentrifuges tubes and immunofluorescence were performed as previously published69 using anti-peroxisomal membrane protein 70 (PMP70) and Alexa Fluor 488, and anti-uricase antibody (sc-166070, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and Alexa Fluor 647 (Thermo Fisher). Nuclei was stained with DAPI. Slides for both, cells and spheroids were prepared using Fluoromount Aqueous Mounting Medium (Sigma-Aldrich). Images were captured using with a 63x oil immersion objective by using a LSM 700 laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss). The wavelength of the RFP protein from Donor DNA is 594 nm, yet for the colocalization experiments we used the Far-Red secondary antibody against the uricase primary with a wavelength 647 nm, thus filtering out most RFP signal.

Uric acid consumption

Uric acid was added to cells and spheroids at different concentrations: 150 µM (2.5 mg/dL), 300 µM (5.0 mg/dL), 450 µM (7.5 mg/dL) or 600 µM (10.0 mg/dL). Cells and spheroids were cultured for 5 days in the presence of uric acid, supernatant was collected every 24 h and uric acid was determined using Uric Acid/Uricase Assay kit (STA-375, Cell Biolabs) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Determination of intracellular uric acid, triglycerides and ATP levels

Cells and spheroids were exposed to fructose to determine the intracellular levels of uric acid and triglycerides. Zero or 20 mM of fructose was added to low-glucose DMEM (5.5 mM) and incubated for 72 h, and the medium was changed twice per day. Intracellular uric acid levels and triglycerides were determined using Uric Acid/Uricase Assay kit (STA-375, Cell Biolabs) and Serum Triglyceride Quantification Kit – Fluorometric (STA-397, Cell Biolabs), respectively following to manufacturer’s instructions.

For starvation experiments, spheroids were grown in the absence of glucose and FBS for 0, 48 and 72 h. Spheroids were collected, lysate and intracellular uric acid, triglycerides and ATP levels were determined using Uric Acid/Uricase Assay kit (STA-375, Cell Biolabs), Serum Triglycerides Quantification Kit – Fluorometric (STA-397, Cell Biolabs) and ATP Assay Kit (MAK190, Sigma-Aldrich), respectively according to manufacturer’s instructions. Protein concentration was determined by the BCA Protein Assay kit (Pierce, Thermo Scientific).

Protein extraction and Western blotting analysis

Cells and spheroids exposed to fructose, or spheroids under starvation, were lysed in cold RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) in the presence of protease/phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific) and sonicated. Samples were centrifuged at 13,000× g for 5 min at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were determined with the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Thermo Scientific). 20 µg of total protein was loaded into SDS-PAGE gels (Tris-glycine buffer), BLUEstain™ 2 protein ladder 5-245 kDa (Gold Biotechnology), then transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Bio-Rad) and blocked in the presence of 5% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies: anti-phosphorylated Acetyl-CoA carboxylase (pACC; 11818 S, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-ACC (3676 S, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phosphorylated AMP Kinase (pAMPK; 2535 S, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-AMPK (5832 S, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-uricase (sc-166070, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), anti-beta-actin (sc-47778, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). After the antibodies for pACC and pAMPK were assay and imaged, the membranes were stripped using mild stripping buffer [1.5% Glycine (w/v), 1% SDS (w/v) and 1% Tween 20 (w/v)]. Briefly, the membranes were covered with the buffer and incubated at room temperature for 5 min. This step was repeated, and the membranes were washed three times with TBST for 5 min each at room temperature. Membranes were then blocked again and the antibodies for uricase, actin and AMPK, and lastly ACC, were applied and imaged. Membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies. Signal was detected after incubation with Clarity Western ECL Substrate kit (Bio-Rad) and captured using auto exposure and analyzed with a ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad). The whole membranes images are shown in Supplementary Information 1.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate and data are presented as the mean±SEM. Data graphics and statistical analyses were performed using Prism10 (Graph-Pad). Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, Tukey’s post hoc t-test. A value of p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Data availability

The DNA CRISPR Donor sequence generated and analyzed during the current study is available in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at the National Institutes of Health, Accession PQ792649. Direct link to the nucleotide sequence is: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/PQ792649.1/.

References

Hershfield, M. S. et al. Treating gout with pegloticase, a pegylated urate oxidase, provides insight into the importance of uric acid as an antioxidant in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 107, 14351–14356. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1001072107 (2010).

Ramazzina, I., Folli, C., Secchi, A., Berni, R. & Percudani, R. Completing the uric acid degradation pathway through phylogenetic comparison of whole genomes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 144–148 (2006).

Keebaugh, A. C. & Thomas, J. W. The evolutionary fate of the genes encoding the purine catabolic enzymes in hominoids, birds, and reptiles. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 1359–1369. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msq022 (2010).

Major, T. J. et al. A genome-wide association analysis reveals new pathogenic pathways in gout. Nat. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-024-01921-5 (2024).

Wu, X. W., Muzny, D. M., Lee, C. C. & Caskey, C. T. Two independent mutational events in the loss of urate oxidase during hominoid evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 34, 78–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00163854 (1992).

Li, Z., Hoshino, Y., Tran, L. & Gaucher, E. A. Phylogenetic Articulation of Uric Acid Evolution in Mammals and How It Informs a Therapeutic Uricase. Mol. Biol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab312 (2022).

Kratzer, J. T. et al. Evolutionary history and metabolic insights of ancient mammalian uricases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111, 3763–3768. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1320393111 (2014).

Tan, P. K., Farrar, J. E., Gaucher, E. A. & Miner, J. N. Coevolution of URAT1 and uricase during primate evolution: implications for serum urate homeostasis and gout. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 2193–2200. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msw116 (2016).

Kelly, S. J. et al. Diabetes insipidus in uricase-deficient mice: a model for evaluating therapy with poly(ethylene glycol)-modified uricase. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 12, 1001–1009 (2001).

Tran, L., Das, S., Zhao, L., Finn, M. G. & Gaucher, E. A. Oral delivery of nanoparticles carrying ancestral uricase enzyme protects against hyperuricemia in knockout mice. Biomacromolecules 24, 2003–2008. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.biomac.2c01388 (2023).

Lu, J. et al. Knockout of the urate oxidase gene provides a stable mouse model of hyperuricemia associated with metabolic disorders. Kidney Int. 93, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2017.04.031 (2018).

Johnson, R. J., Lanaspa, M. A. & Gaucher, E. A. Uric acid: a danger signal from the RNA world that May have a role in the epidemic of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiorenal disease: evolutionary considerations. Semin Nephrol. 31, 394–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semnephrol.2011.08.002 (2011).

Alvarez-Lario, B. & Macarron-Vicente, J. Uric acid and evolution. Rheumatol. (Oxford). 49, 2010–2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/keq204 (2010).

Johnson, R. J. et al. Lessons from comparative physiology: could uric acid represent a physiologic alarm signal gone awry in Western society? J. Comp. Physiol. B. 179, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-008-0291-7 (2009).

Chen, R. et al. Associations of serum uric acid, risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and mortality: results from NHANES. Eur. J. Med. Res. 30, 283. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-025-02548-w (2025).

Feig, D. I., Kang, D. H. & Johnson, R. J. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N Engl. J. Med. 359, 1811–1821. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra0800885 (2008). [pii].

Chang, B. S. Ancient insights into uric acid metabolism in primates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 111, 3657–3658. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1401037111 (2014).

Johnson, R. J. et al. Fructose metabolism as a common evolutionary pathway of survival associated with climate change, food shortage and droughts. J. Intern. Med. 287, 252–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12993 (2020).

Cicerchi, C. et al. Uric acid-dependent Inhibition of AMP kinase induces hepatic glucose production in diabetes and starvation: evolutionary implications of the uricase loss in hominids. FASEB J. 28, 3339–3350. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.13-243634 (2014).

Choi, Y. J. et al. Uric acid induces fat accumulation via generation of Endoplasmic reticulum stress and SREBP-1c activation in hepatocytes. Lab. Invest. 94, 1114–1125. https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2014.98 (2014).

Lanaspa, M. A. et al. Endogenous Fructose production and metabolism in the liver contributes to the development of metabolic syndrome. Nat. Commun. 4, 2434. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3434 (2013).

Johnson, R. J., Andrews, P. & Fructose Uricase, and the Back-to-Africa hypothesis. Evol. Anthropol. 19, 250–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/Evan.20266 (2010).

Johnson, R. J. et al. Hypothesis: could excessive Fructose intake and uric acid cause type 2 diabetes? Endocr. Rev. 30, 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1210/er.2008-0033 (2009). [pii].

Johnson, R. J. et al. The planetary biology of ascorbate and uric acid and their relationship with the epidemic of obesity and cardiovascular disease. Med. Hypotheses. 71, 22–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2008.01.017 (2008).

Sautin, Y. Y. & Johnson, R. J. Uric acid: the oxidant-antioxidant paradox. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 27, 608–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/15257770802138558 (2008).

Watanabe, S. et al. Uric acid, hominoid evolution, and the pathogenesis of salt-sensitivity. Hypertension 40, 355–360 (2002).

Lanaspa, M. A. et al. Uric acid stimulates fructokinase and accelerates Fructose metabolism in the development of fatty liver. PLoS One. 7, e47948. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0047948 (2012).

Jensen, T. et al. Fructose and sugar: A major mediator of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 68, 1063–1075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.019 (2018).

Ouchi, R. et al. Modeling steatohepatitis in humans with pluripotent stem Cell-Derived organoids. Cell. Metab. 30, 374–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.007 (2019). e376.

Prior, N., Inacio, P. & Huch, M. Liver organoids: from basic research to therapeutic applications. Gut 68, 2228–2237. https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319256 (2019).

de Collin, A. et al. Generation of Human Fatty Livers Using Custom-Engineered Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells with Modifiable SIRT1 Metabolism. Cell Metab 30, 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.06.017 (2019).

Grimes, D. R., Kelly, C., Bloch, K. & Partridge, M. A method for estimating the oxygen consumption rate in multicellular tumour spheroids. J. R Soc. Interface. 11, 20131124. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2013.1124 (2014).

Curcio, E. et al. Mass transfer and metabolic reactions in hepatocyte spheroids cultured in rotating wall gas-permeable membrane system. Biomaterials 28, 5487–5497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.033 (2007).

Bialkowska, K., Komorowski, P., Bryszewska, M. & Milowska, K. Spheroids as a Type of Three-Dimensional Cell Cultures-Examples of Methods of Preparation and the Most Important Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176225 (2020).

Sadelain, M., Papapetrou, E. P. & Bushman, F. D. Safe harbours for the integration of new DNA in the human genome. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 12, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3179 (2011).

Oceguera-Yanez, F. et al. Engineering the AAVS1 locus for consistent and scalable transgene expression in human iPSCs and their differentiated derivatives. Methods 101, 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.12.012 (2016).

Chu, V. T. et al. Increasing the efficiency of homology-directed repair for CRISPR-Cas9-induced precise gene editing in mammalian cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 543–548. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.3198 (2015).

Liu, W. et al. IBS: an illustrator for the presentation and visualization of biological sequences. Bioinformatics 31, 3359–3361. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv362 (2015).

de Lima Balico, L. & Gaucher, E. A. CRISPR-Cas9-mediated reactivation of the uricase pseudogene in human cells prevents acute hyperuricemia. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 25, 578–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2021.08.002 (2021).

Johnson, R. J. et al. The Fructose survival hypothesis for obesity. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 378, 20220230. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2022.0230 (2023).

Andrews, P. & Johnson, R. J. Evolutionary basis for the human diet: consequences for human health. J. Intern. Med. 287, 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.13011 (2020).

Wen, S., Arakawa, H. & Tamai, I. Uric acid in health and disease: from physiological functions to pathogenic mechanisms. Pharmacol. Ther. 256, 108615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2024.108615 (2024).

Liu, D. et al. What Is the Biological Function of Uric Acid? An Antioxidant for Neural Protection or a Biomarker for Cell Death. Dis. Markers https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/4081962 (2019).

El Ridi, R. & Tallima, H. Physiological functions and pathogenic potential of uric acid: A review. J. Adv. Res. 8, 487–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2017.03.003 (2017).

Kanbay, M. et al. The role of uric acid in the pathogenesis of human cardiovascular disease. Heart 99, 759–766. https://doi.org/10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302535 (2013).

Chang, C. Y., Ke, D. S. & Chen, J. Y. Essential fatty acids and human brain. Acta Neurol. Taiwan. 18, 231–241 (2009).

Singh, M. Essential fatty acids, DHA and human brain. Indian J. Pediatr. 72, 239–242 (2005).

DeCasien, A. R., Williams, S. A. & Higham, J. P. Primate brain size is predicted by diet but not sociality. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 112. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0112 (2017).

Christen, P., Peacock, W. C., Christen, A. E. & Wacker, W. E. Urate oxidase in primate phylogenesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 12, 3–5 (1970).

Nakajima, Y. & Bourne, G. H. Histochemical studies on urate oxidase in several mammals with special reference to uricolytic ability of primates. Histochemie 22, 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00310545 (1970).

Andrews, P. Last common ancestor of apes and humans: morphology and environment. Folia Primatol. (Basel). 91, 122–148. https://doi.org/10.1159/000501557 (2020).

Herzig, S. & Shaw, R. J. AMPK: guardian of metabolism and mitochondrial homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm.2017.95 (2018).

Jordan, D. M. et al. No causal effects of serum urate levels on the risk of chronic kidney disease: A Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 16, e1002725. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002725 (2019).

Rasheed, H., Hughes, K., Flynn, T. J. & Merriman, T. R. Mendelian randomization provides no evidence for a causal role of serum urate in increasing serum triglyceride levels. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 7, 830–837. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.000556 (2014).

Neel, J. V. Diabetes mellitus: a thrifty genotype rendered detrimental by progress? Am. J. Hum. Genet. 14, 353–362 (1962).

Fini, M. A. et al. Brief report: the uricase mutation in humans increases our risk for cancer growth. Cancer Metab. 9, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40170-021-00268-3 (2021).

Johnson, R. J., Andrews, P., Benner, S. A., Oliver, W. & Theodore, E. Woodward award. The evolution of obesity: insights from the mid-Miocene. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol Assoc. 121, 295–305 (2010). discussion 305 – 298.

Perez-Ruiz, F. et al. Treatment of chronic gout in patients with renal function impairment: an open, randomized, actively controlled study. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 5, 49–55 (1999).

Wen, C. C. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies ABCG2 (BCRP) as an allopurinol transporter and a determinant of drug response. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 97, 518–525. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpt.89 (2015).

Sundy, J. S. et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pegloticase for the treatment of chronic gout in patients refractory to conventional treatment: two randomized controlled trials. JAMA 306, 711–720. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1169 (2011). [pii].

Lyseng-Williamson, K. A. Pegloticase: in treatment-refractory chronic gout. Drugs 71, 2179–2192. https://doi.org/10.2165/11202830-000000000-00000 (2011). [pii].

Lipsky, P. E. et al. Pegloticase immunogenicity: the relationship between efficacy and antibody development in patients treated for refractory chronic gout. Arthritis Res. Ther. 16, R60. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar4497 (2014).

Villiger, L. et al. Treatment of a metabolic liver disease by in vivo genome base editing in adult mice. Nat. Med. 24, 1519–1525. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-018-0209-1 (2018).

Lee, J. H. et al. In vivo genome editing for hemophilia B therapy by the combination of rebalancing and therapeutic gene knockin using a viral and non-viral vector. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 32, 161–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2023.03.008 (2023).

Han, J. P. et al. In vivo genome editing using 244-cis LNPs and low-dose AAV achieves therapeutic threshold in hemophilia A mice. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids. 34, 102050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2023.102050 (2023).

He, X. et al. Low-dose AAV-CRISPR-mediated liver-specific knock-in restored hemostasis in neonatal hemophilia B mice with subtle antibody response. Nat. Commun. 13, 7275. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34898-y (2022).

Yin, H. et al. Genome editing with Cas9 in adult mice corrects a disease mutation and phenotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 551–553. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2884 (2014).

Ran, F. A. et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2013.143 (2013).

Bergdorf, K. N. et al. Immunofluorescent staining of cancer spheroids and fine-needle aspiration-derived organoids. STAR. Protoc. 2, 100578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100578 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Human Frontier Science Program grant RGP0041/2017, National Science Foundation grant 2032315, Department of Defense grant MURI W911NF-16-1-0372, National Institutes of Health grant R01AR069137. Confocal images were acquired using the instruments and services in the Imaging Core Facility at GSU and managed by Prof. Kuangcai Chen and Claudia Sanabria. We thank Prof. Geert de Vries, Ze ‘Lake’ Li, Lily Tran, Department of Biology GSU for support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.B. and E.G. conceived the project, L.B. conducted the research, L.B. and E.G. reviewed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Lima Balico, L., Gaucher, E.A. Genomic insertion of ancestral uricase into human liver cells to determine metabolic consequences of pseudogenization. Sci Rep 15, 26093 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10551-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10551-8