Abstract

Meta-heuristic optimization algorithms need a delicate balance between exploration and exploitation to search for global optima without premature convergence effectively. Parallel Sub-Class Modified Teac hing–learning-based optimization (PSC-MTLBO) is an improved version of TLBO proposed in this study to enhance search efficiency and solution accuracy. The proposed approach integrates three existing modifications—adaptive teaching factors, tutorial-based learning, and self-motivated learning—while introducing two novel enhancements: a sub-class division strategy and a challenger learners’ model to enhance diversity and convergence speed. The proposed method was evaluated using three benchmark function sets (23 classical functions, 25 CEC2005 functions, and 30 CEC2014 functions) and two real-world truss topology optimization problems. Experimental results confirm that PSC-MTLBO performs better than normal TLBO, MTLBO, and other meta-heuristics such as PSO, DE, and GWO. For instance, PSC-MTLBO obtained the maximum overall rank in 80% of the test functions with the minimization of function errors by as much as 95% over traditional TLBO. In truss topology optimization, PSC-MTLBO designed lighter and more cost-effective structures with a weight reduction of 7.2% over the best solutions previously obtained. The challenger learners’ model enhanced the adaptability, whereas the sub-class strategy increased the convergence and stability of results. In conclusion, PSC-MTLBO offers a remarkably efficient and scalable optimization framework and exhibits notable advances over current algorithms, with its suitability in solving complex optimization problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past years, optimization techniques have undergone substantial development and refinement, emerging as crucial tools for optimizing complex problems. The introduction of the Genetic Algorithm (GA) (Holland, 1975)1 marked a seminal moment in the evolution of meta-heuristics, leading to the development of several subsequent algorithms. Among these, notable contributions include Simulated Annealing by Kirkpatrick et al. (1983)2, Evolution Strategy by Auger and Hansen (2005)3, Passing Vehicle Search (Tejani et al., 2018a)4, Kumar et al. (2021)5, and Ameliorated Follow The Leader (Singh et al., 2022)6, along with numerous other pioneering algorithms.

In 2021, Dong et al.7 discussed KTLBO which employed Kriging to construct dynamically updated surrogate models for expensive objective and constraint functions. Using an adaptive penalty function for elite selection, a data management technique was created to store, categorize, and update pricey samples. Prescreening operators were used to balance exploration and exploitation in a two-phase optimization framework that alternated between local and global searches. KTLBO showed notable benefits in costly constrained optimization when compared to six popular approaches on 27 benchmark problems. It was then used to create a good solution for the structural design of an underwater glider with a blended wing body. In 2021, Ma et al.8 presented the traditional Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization algorithm was enhanced with a novel population group mechanism by MTLBO. Students were split up into two groups with distinct approaches to updating their solutions during the Teaching and Learning stages. Tested on 14 unconstrained numerical functions, the algorithm outperformed TLBO and other cutting-edge techniques in terms of convergence speed and solution quality. Next, an extreme learning machine for modeling NOx emissions was tuned using MTLBO. Lastly, it successfully decreased the concentration of NOx emissions by optimizing the operating characteristics of a 330 MW circulation fluidized bed boiler.

In 2021, Chen et al.9 suggested the SHSLTLBO which enhanced the original TLBO’s performance on shifted issues by using a self-adaptive framework with a Gaussian distribution. A self-learning phase was included to avoid local convergence during startup, and a novel updating rule alternated between two modes according to fitness. The approach was evaluated on numerical benchmark functions and contrasted with meta-heuristic techniques and the most recent TLBO variations. The results showed that SHSLTLBO is better at maintaining stability across dimensions and balancing evolutionary stages. It demonstrated the best convergence and stability across all 28 benchmarks, outperforming LSHADE and HCLPSO on low-dimensional and shifted issues.

In 2022, Dastan et al.10 presented Charged System Search (CSS) and Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) were coupled by HTC to improve exploration and exploitation. To overcome TLBO’s potential to become stuck in local optima, CSS stored and used ideal positions by applying the rules of electrostatic physics. The approach was used to optimize benchmark truss structures after being verified on CEC2021 and CEC2005 mathematical functions. The results showed optimal weight reduction and enhanced convergence under stress and displacement limits. HTC performed better than other meta-heuristic techniques, obtaining optimal designs more quickly. In 2024, Chen et al.11 discussed STLBO which enhanced the original TLBO by introducing a linear increasing teaching factor, an elite system with a new teacher and class leader, and Cauchy mutation. To enhance exploration and exploitation, these techniques were combined to create seven STLBO versions. In thirteen numerical optimization tasks, the algorithm was evaluated, and STLBO7 performed the best. STLBO7 demonstrated improved local optimal avoidance, faster convergence, and higher solution accuracy when compared to other sophisticated optimization approaches. Overall, TLBO’s search performance and optimization capabilities were greatly enhanced by STLBO.

Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) was pioneered by Rao et al. (2011)12, motivated by the student–teacher dynamic in a classroom. Building on this foundation, subsequent research by Rao and Patel (2013)13, Patel and Savsani (2014)14, Wang et al. (2014)15, Savsani et al. (2016, 2017)16,17, Tejani et al. (2016b, 2017)18,19, Kumar et al. (2021, 2022a)5,20, Savsani et al. (2024)21, and Kalpana & Kesavamurthy (2024)22 has introduced progressive enhancements to the core TLBO algorithm, aiming to improve its exploration and exploitation capabilities. These adaptations have been recognized for their efficiency in addressing both single and multiple objective optimizers.

However, despite the proliferation of algorithms and enhancements in literature, the No Free Lunch theorem23 reminds us that no single algorithm is a universal problem-solver. As a result, scholars persistently strive to refine existing meta-heuristics and develop novel ones. This very impetus drove our endeavor to advance TLBO through the development of the parallel sub-class (PSC-MTLBO) algorithm. The efficacy of these proposed algorithms is rigorously assessed across three widely recognized benchmark test sets and two practical complications.

In the initial evaluation, the performance of the proposed methods is evaluated across 23 classical benchmark functions, comparing them against established cutting-edge algorithms for benchmarking purposes. This comparative analysis includes Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) (Su et al., 2024)24, Fast Evolutionary Programming (FEP) (Sinha et al., 2003)25, Differential Evolution (DE) (Ahmad et al., 2022)26, Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) (Xiao et al., 2023)27, Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA) (Mittal et al., 2021)28, Cuckoo Search (CS) (Xiong et al., 2023)29, Firefly Algorithm (FA) (Karthikeyan, 2024)30, Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) (Qiu et al., 2024)31, and Animal Migration Optimization (AMO) (Abualigah et al., 2024)32.

In a second round of testing, the proposed algorithms were evaluated using 25 benchmark functions from CEC2005. Here too, they were compared against a broad range of state-of-the-art optimization methods, including established algorithms like Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) (Su et al., 2024)24 and Steady-State Genetic Algorithm (SSGA) (Ghoshal and Sundar, 2023)33, as well as more recent advancements such as variants of Differential Evolution (DE, DE-Bin, DE-Exp, SaDE) (Phocas et al., 2020)34, IPOP-CMA-ES [Auger and Hansen, 2005]3, ant-colony optimization (ACO) [Korzeń and Gisterek 2024]35, Artificial Bee Colony (ABC)27, Bat Algorithm (BA) [Yuan et al., 2024]36, and Artificial-Algae Algorithm (AAA) [Turkoglu et al., 2024]37.

The fourth assessment phase utilized 30 benchmark functions from CEC2014. In this stage, the proposed algorithms were pitted against another set of well-established optimization techniques, including Invasive Weed Optimization (IWO) [Rahmani et al., 2021]38, Biogeography-Based Optimization (BBO)39, Gravitational Search Algorithm (GSA)28, Hunting Search (HuS) [Oftadeh et al., 2010]40, Bat Algorithm (BA)36, and Water Wave Optimization (WWO) [Zheng, 2015]41.

In the final assessment phase, two real-world truss topology optimization (TTO) problems were employed. During this stage, the proposed algorithms were compared against a set of established optimization techniques, including the Invasive Ant Lion Algorithm (ALO), Dragonfly Algorithm (DA), Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA), and Heat Transfer Search (HTS)42. The shortcomings of TLBO include inefficiency in high-dimensional problems, insufficient exploration–exploitation balance, and premature convergence. It has trouble catching local optima and is not able to adapt to complicated terrain. Nowadays, they include improvements such as adaptive learning and Kriging models but still have limitations in terms of scalability and organized information transmission. Additionally, the sequential nature of TLBO limits parallelization, which lowers computational efficiency. PSC-MTLBO addresses these problems by using adaptive teaching variables, parallel learning techniques, and structured sub-class partitioning for better optimization performance.

The following segments of this study are organized as follows: Section"Teaching–learning-based optimization (TLBO)"elaborates on TLBO, detailing its foundational principles. Section"Modifications in TLBO"expounds upon the enhancements proposed for TLBO. Section"Experiment and discussion"presents an inclusive investigation of the planned algorithm’s performance across various unconstrained benchmark functions. Ultimately, Sect. 5 concludes this investigation, summarizing the findings and implications of the study.

Teaching–learning-based optimization (TLBO)

The process of teaching and learning holds significant importance as learners gain knowledge from both instructors and peers. Drawing inspiration from this educational dynamic, Rao et al. (2011)13 introduced TLBO. This meta-heuristic mirrors the interactive learning process observed in a classroom setting.

TLBO functions as a population-based meta-heuristic, conceptualizing learners as the population and considering various subjects as the design variables. In contrast to methods such as GA, DE, BBO, and GWO, which rely on specific parameters like mutation, crossover, and selection rates, TLBO operates with only fundamental controlling factors such as population size and iteration count. Consequently, TLBO can be characterized as a parameter-free, population-based meta-heuristic.

TLBO operates through two primary learning modes: (i) learning facilitated by a teacher and (ii) learning via interactions among learners. Detailed descriptions of these phases are provided.

Teacher phase

The influence of an instructor’s caliber on students within a classroom environment is profound. A proficient teacher not only inspires students but also aids in enhancing their knowledge. In this phase, the optimal solution within the class is deemed as the ‘teacher.’ This instructor consistently enhances learners’ understanding and strives to boost the collective performance of the class.

Additionally, students augment their knowledge through a combination of the instructor’s expertise and their capabilities in the class. Therefore, the contrast between the instructor’s grade and the average grade of the students in each subject is employed for assessing the difference in means (DM) and subsequently updating the current solution (Eqs. 1–3).

Learner phase

TLBO further emulates learning through interactions among the learners. Within this phase, learners have the opportunity to acquire knowledge by interacting with their peers. This learning dynamic is mathematically articulated in Eq. 4, outlining the phenomenon of knowledge acquisition through peer interactions. The detailed steps of TLBO are elaborated upon in the subsequent section.

TLBO steps

-

Step I: Articulate the optimization problem, aiming to minimize \(f\left(X\right).\) Where \(f\left(X\right)\) represents the objective function, where ‘X’ stands as the design variable.

-

Step II: Establish the population (i.e., learners, denoted as k = 1,2,…,n) and the design variables (i.e., the number of topics available for learners, j = 1,2,…,m), as well as the termination criterion (such as the limiting function evaluation number, FEmax).

-

Step III: Initiate the randomly generated population while ensuring adherence to their respective upper and lower bounds, followed by their evaluation.

-

Step IV: Sort the population from lowest to highest according to their performance.

-

Step V: Calculate the average performance of the group of students in each topic. (i.e. Mj).

-

Step VI: Compute the variance between the present mean and the teacher’s respective grades in each subject, employing the teaching factor. (TF) using Eq. (1) (2).

$${DM}_{j} = rand*({X}_{j}- TF*{M}_{j})$$(1)$$where, TF=round[1+rand\left(0, 1\right)]$$(2) -

Step VII: In the teacher phase, learners enhance their grades by leveraging the expertise of the teacher is determined by Eq. (3).

$${X}^{\prime}_{k}=\left\{\begin{array}{c}{[(X}_{k}+{DM}_{k})+rand*({X}_{p}-{X}_{k})] ,if f({X}_{p})<f({X}_{k})\\ {[(X}_{k}+{DM}_{j})+rand*({X}_{k}-{X}_{p})],if f({X}_{p})>f({X}_{k})\end{array}\right.$$(3) -

Where p is any learner of the class (p ≠ k) and \({X}_{k}{\prime}\) is the design vector of the updated learner.

-

Step VIII: Enhance the learners’ knowledge by integrating insights from fellow learners and through self-directed learning processes through Eq. (4).

$${X}^{\prime\prime}_{k}=\left\{\begin{array}{c}[{X}_{k}^{\prime}+rand*({X}_{k}^{\prime}-{X}_{q}^{\prime})+rand*\left({X}_{1}-{E}_{F}*{X}_{k}^{\prime}\right)], if f\left({X}_{k}^{\prime}\right)<f({X}_{q}^{\prime})\\ {[X}_{k}^{\prime}+rand*({X}_{q}^{\prime}-{X}_{k}^{\prime})+rand*\left({X}_{1}-{E}_{F}*{X}_{k}^{\prime}\right)], if f\left({X}_{k}^{\prime}\right)>f({X}_{q}^{\prime})\end{array}\right.$$(4) -

where EF = exploration factor = round (1 + rand); X1 is the design vector of the teacher; q is any learner (q ≠ k);\({X}_{k}^{{\prime}{\prime}}\) is a design vector of the updated learner.

-

Step X: Termination criterion (FE ≤ FEmax): Carry out the steps starting from III until the specified termination condition is satisfied.

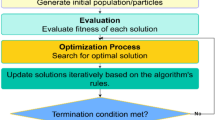

The flowchart illustrating TLBO is depicted in Fig. 1. Pseudo-code of TLBO is shown below:

Flowchart of the TLBO algorithm46.

Modifications in TLBO

In TLBO, learner grades undergo improvement through both teacher intervention and interactive learning among the learners themselves. Learners engage in interactions among themselves, fostering grade improvement. The teaching factor within TLBO exists as either one or two, representing two extremes: learners either absorb all or none of the teacher’s knowledge. In scenarios where the teaching factor is set to its higher value, the teacher expends additional effort to enhance learner grades. Additionally, the convergence process is steered by both the teacher’s influence and the mean performance of the learners across the search space.

Consequently, as the instructor nears the average performance of the learners, and when individual learners near each other during optimization, there may be minimal changes in the learners’ positions. This scenario has the potential to result in premature convergence and the identification of localized optimal solutions, limiting overall optimization, as learners tend to remain nearby without significant movement.

To address this, three modifications from previous studies—namely, adaptive-teaching factors (ATF), self-motivated learning (SML), and tutorial-based learning (TBL)—are integrated into TLBO. Additionally, two novel modifications, sub-classes, and the challenger learners’ model are introduced. These improvements are intended to accelerate the search process, increase the rate of convergence, and avoid falling into local optima. Detailed descriptions of these improvements are provided in the subsequent sections.

Number of sub-classes

In TLBO, a solitary instructor is responsible for instructing and attempting to enhance the mean grades of the entire class. However, in this teaching–learning scenario, the teacher’s efforts might become diffused, and conversely, students could demonstrate reduced engagement, resulting in diminished learning intensity. Furthermore, when a substantial portion of the class consists of students performing below the average, the teacher might need to apply additional effort to improve their grades. Despite these efforts, noticeable grade improvements might not manifest, potentially leading to premature convergence.

To mitigate these challenges, the first modification in TLBO involves dividing the entire class—comprising learners (k = 1,2,…,n) and the subjects offered (j = 1,2,…,m)—into sub-classes of similar size based on the learners’ proficiency levels (grades). Each sub-class is assigned a dedicated teacher responsible for improving the grades within that specific sub-class. As learners progress to higher levels, they are reassigned to more proficient teachers. This adjustment is designed to deter premature convergence by ensuring continual progress among the learners. The mathematical rationale behind this adaptation is elucidated in Eqs. 5 and 6.

Allocate learners to individual sub-classes based on their respective fitness values using Eq. (5):

Assigning a teacher to each sub-class is defined as per Eq. (6):

Adaptive-teaching factor

In TLBO, the determination of the teaching factor (TF) occurs via a heuristic procedure, offering two extreme values: TF equals one or two, implying learners either absorb all or none of the knowledge provided by the teacher. However, in practical scenarios, learners typically acquire knowledge in varying proportions from the teacher.

Throughout the optimization process, a TF close to 1 facilitates finer search increments, leading to slower convergence, while a TF near 2 accelerates the search but diminishes exploration capabilities. To address this, Rao and Patel (2013) and Patel and Savsani (2014a; 2014b) introduced an ATF within TLBO. The ATF dynamically adjusts during the search, enhancing the algorithm’s performance. This adaptive modification is encapsulated in Eq. (7) and (8).

Learning through tutorial

In contemporary educational approaches, educators frequently allocate interactive assignments, problem sets, and tutorial sessions to learners during tutorial hours. During these sessions, learners engage in discussions with their peers or the teacher, enhancing their understanding while working through these tasks collaboratively. Acknowledging the potential for students to improve their knowledge through these interactions, this particular search methodology becomes integrated into the teacher phase.

This alteration, known as learning through tutorials (introduced by Rao and Patel, 2013; Patel and Savsani, 2014a; 2014b), combines the learning process from tutorials with the learner phase. The mathematical representation of this integration is encapsulated in Eq. (9).

Self-motivated learning

In TLBO, learner grades improve through learning from the teacher or interaction among learners. However, self-motivated learners possess the ability to enhance their knowledge through self-directed learning. Therefore, incorporating SML (as introduced by Rao and Patel, 2013; Patel and Savsani, 2014a; 2014b) is embraced within the modified TLBO framework. This addition further amplifies TLBO’s capacity for exploration and exploitation. This modification is integrated within the teacher phase, and its mathematical representation is outlined in Eq. (10).

Challenger learners’ model

During the optimization process, there is a risk of becoming trapped in local optimal segments, which can lead to stagnation in learners’ improvement and possibly result in a local optimal solution. This situation not only reduces the algorithm’s accuracy but also poses a challenge in achieving numerical stability. The effectiveness of many meta-heuristic techniques depends heavily on avoiding local optima, improving stability, and enhancing precision. Additionally, the success of a solution often depends on the early populations, and there are cases where the initial population fails to effectively explore the global optimum. In such situations, regenerating the initial population becomes necessary to move towards a better solution and escape trapped in local optima.

To tackle these challenges, this study introduces the concept of challenger learners. This model analyzes changes in the teacher’s performance and mean results over a finite number of generations. When the teacher remains constant for a predetermined number of generations, this approach initiates a separate parallel algorithm. So, this characteristic justifies the algorithm’s name PSC-MTLBO, which stands for Parallel Sub-Class Modified Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization. This model operates under two conditions: (1) the initiation or cessation of the Challenger Learners’ Model and (2) the suspension or continuation of the primary PSC-MTLBO algorithm. The model only activates if there’s no improvement in the teacher of a class for a specified number of generations (i.e., idtgen). The mathematical expressions for this section are detailed in the steps of PSC-MTLBO.

In this paper, based on the stated modifications, Modified TLBO (MTLBO) is investigated by considering three modifications (ATF, TBL, and SML) as per Rao and Patel (2013) and Patel and Savsani (2014a; 2014b). Moreover, PSC-MTLBO is formulated by considering all the stated modifications. Detailed steps of MTLBO and PSC-MTLBO are briefed in subsequent sections.

MTLBO steps:

-

Step I: Articulate the optimization problem, pointing to minimize \(f\left(X\right).\) Where \(f\left(X\right)\) represents the objective function, where ‘X’ stands as the design vector.

-

Step II: Establish the population (i.e., learners, denoted as k = 1,2,…,n) and the design variables (i.e., the number of topics available for learners, j = 1,2,…,m), as well as the termination criterion (such as the limiting function evaluation number, FEmax).

-

Step III: Initiate the randomly generated population while ensuring adherence to their respective upper and lower bounds, followed by their evaluation.

-

Step IV: Sort the population from lowest to highest according to their performance.

-

Step V: Calculate the average performance of the group of students in each subject. (i.e. Mj).

-

Step VI: Determine the variance between the present mean and the respective grades (DMj) of the teacher for each subject by incorporating \(ATF\) (Eqs. 7 and 8).

-

Step VII: Within tutorial hours, learners enhance their grades by leveraging the teacher’s expertise (Eq. 9).

-

Step VIII: Enhance the learners’ knowledge by incorporating insights from other learners and through self-directed learning (Eq. 10).

-

Step X: Termination criterion (FE ≤ FEmax): Carry out the steps starting from III until the specified termination condition is satisfied.

The flowchart illustrating MTLBO is depicted in Fig. 2.

Flowchart of the MTLBO algorithm9.

The PSC-MTLBO algorithm steps

-

Step I: Articulate the optimization problem, aiming to minimize \(f\left(X\right).\) Where \(f\left(X\right)\) represents the objective function, where ‘X’ stands as the design vector.

-

Step II: Establish the population (i.e., learners denoted as k = 1,2,…,n), design variables (i.e., the number of topics available for learners, j = 1,2,…,m), the number of sub-classes (s), and the termination criterion (FEmax).

-

Step III: Initiate the randomly generated population while ensuring adherence to their respective upper and lower bounds, followed by their evaluation.

-

Step IV: Sort the population from lowest to highest according to their performance. Segment the class into ‘s’ sub-classes and allocate an equal number of learners to each sub-class based on their fitness value (Eq. 5).

-

Step V: From each sub-class, designate the optimal solution within the sub-class as the teacher, denoted as Ts (Eq. 6). Calculate the average performance of each sub-class of learners in every subject. (i.e. Mj)

-

Step VI: Compute the variance between the present mean and the respective grades within each sub-class, (DMj) of the teacher within that specific sub-class for each subject, employing ATF.

-

Step VII: Within tutorial hours, each sub-class enhances the learners’ knowledge by leveraging the teacher’s expertise (Eq. 9).

-

Step VIII: Update the learners’ knowledge within each sub-class by integrating insights from other learners and through self-directed learning (Eq. 10).

-

Step IX: Meagre all sub-classes.

-

Step X: Starting condition of challenger learners’ model: \({f\left({\text{X}}_{1}\right)}_{g}={f\left({\text{X}}_{1}\right)}_{g-\text{idt}\_\text{gen}}\), where g is the present generation number.

-

Stooping condition of challenger learners’ model: \({f\left({\text{Y}}_{1}\right)}_{\text{challenger }}>f\left({\text{X}}_{1}\right)\). Y is the challenger learner population.

-

Step XI: Replace the learners (k = 1,2,…,n) of the basic model with the challenger learners, if the grade of the challenger is better.

-

Step XII: If mean grades of class (i.e.\(\sum f\left({\text{X}}_{k}\right)\)) do not improve for the next generation, pause main SC-MTLBO but the challenger learners’ model keeps the search continues. If the mean grades of the teacher improve for the next generation continue the main SC-MTLBO.

-

Stopping condition of main SC-MTLBO: \(\sum {f\left(\text{X}\right)}_{g}-\sum {f\left(\text{X}\right)}_{g-1}=0\)

-

Starting condition of main SC-MTLBO: \(\sum {f\left(\text{X}\right)}_{g}-\sum {f\left(\text{X}\right)}_{g-1}>0\)

-

Step XIII: Termination criterion (FE ≤ FEmax): Carry out the steps starting from III until the specified termination condition is satisfied.

A detailed flowchart of PSC-MTLBO is illustrated in Fig. 3. Pseudo-code of the PSC-MTLBO is shown below:

TLBO’s computational complexity is \(O\left(N\cdot D\cdot T\right),\) where \(N\) is the population size, \(D\) is the problem dimension, and \(T\) is the number of iterations. The complexity rises to \(O\left(G\cdot N\cdot D\cdot T\right),\) where \(G\) is the number of sub-classes since PSC-MTLBO adds parallel sub-classes. Although TLBO is computationally efficient, its early convergence may cause it to struggle with high-dimensional, complex situations. Although PSC-MTLBO improves exploration and convergence, the additional group processing it requires raises computing costs. The overhead is still controllable for small \(G,\) but PSC-MTLBO needs much more processing power for large \(G.\)

Experiment and discussion

Within this unit, the performance assessment of PSC-MTLBO encompasses three categories of unconstrained benchmarks, varying across dimensions and search spaces. Comparative analyses are conducted between the results achieved using PSC-MTLBO and those attained through basic TLBO, MTLBO, and several other prevalent meta-heuristics documented in existing literature.

The initial two sets encompass 23 classical benchmarks, while the subsequent test involves 25 benchmark functions sourced from the CEC2005 set. The fourth test involves the evaluation of 30 benchmark functions from the CEC2014 collection. The final test involves two real-world TTO problems constrained by real-world considerations. Notably, all functions are configured for minimization purposes. The selection of parameter settings is predicated on previous research and benchmark criteria. To provide fair comparisons, population size and function evaluations (\({FE}_{\text{max}}\)) changed according to function complexity. The parameters were consistent across evaluated algorithms and matched the CEC2005 and CEC2014 benchmarks. To reduce manual tuning, the adaptive teaching factor, sub-class division, and challenger learners’ model were dynamically modified. The parameters for real-world truss topology optimization were selected for practical application based on engineering research and structural restrictions.

The rationale behind selecting these benchmark functions lies in their established prominence within the field, facilitating the comparability of results against other algorithms documented in existing literature.

The ensuing discussion and results will elucidate various investigations undertaken to analyze and interpret the performance of PSC-MTLBO across these diverse benchmark functions.

Results on benchmark suite 1

This experiment employs 23 benchmarks (outlined in Table 1) to assess the efficacy of PSC-MTLBO. Among these benchmarks, f1–f7 are unimodal, f8–f13 are multimodal in high dimensions and functions f14–f23 are multimodal in low dimensions. The table provides details on the function’s dimension (D), search space boundaries (range), and the function’s minimum value (optimum).

PSC-MTLBO, MTLBO, and TLBO undergo 25 independent runs for every benchmark function. The maximum number of Function Evaluations (FEmax) for each test function is detailed below: 150,000FE for functions f1,f6,f10,f12, and f13; 200,000FE for f2 and f11; 300,000FE for f7 to f9; 500,000 FE for f3–f5; 40,000 FE for f15; 10,000FE for f14, f16, f17, f19, and f21–f23; 3,000FE for f18; and 20,000FE for f20. The proposed algorithm’s performance is compared against PSO, DE, BBO, CS, FA, GSA, ABC, AMO, MTLBO, and TLBO.

Table 2 focuses on comparing the mean outcomes, standard deviations (SD), and their corresponding ranks for the unimodal high-dimensional functions (f1–f7), which are suitable for assessing an algorithm’s exploitation capability. The analysis highlights PSC-MTLBO’s achievement of the global optimum mean value for f1–f4 and its attainment of the second-best mean result for functions f6 and f7.

Notably, for functions f5–f7, ABC, AMO, and TLBO demonstrate superior performance compared to the remaining algorithms. TLBO exhibits improved performance for functions f2, f4–f6, with PSC-MTLBO yielding identical results for functions f1 and f3. However, for function f7, PSC-MTLBO slightly underperforms compared to TLBO.

In addition to its performance on functions f1–f4, the MTLBO algorithm demonstrates significant improvements for functions f5, f6, and f7, while maintaining the same results for the former set. This enhancement is particularly evident in the fundamental TLBO, which sees its overall ranking improve from 3 to 1 in mean results and from 2 to 1 in terms of standard deviation (SD) for PSC-MTLBO. Moreover, among all the algorithms tested, PSC-MTLBO achieves the highest overall ranking. The combined performance across functions f1–f7 for PSO, DE, BBO, CS, FA, GSA, ABC, AMO, TLBO, MTLBO, PSC-MTLBO is reported as 10, 5, 11, 8, 9, 6, 7, 2, 3, 3, and 1, respectively, showcasing the effectiveness of MTLBO and its variants in solving optimization problems.

These findings provide substantial evidence that the suggested modifications notably enhance the algorithm’s exploitation capabilities, contributing to a heightened convergence rate in search algorithms.

In Table 3, the comparison is centered on mean values, standard deviation (SD), and algorithm ranks for multimodal functions f8–f13, which are specifically designed to evaluate an algorithm’s ability to explore diverse solutions. The analysis reveals that PSC-MTLBO successfully converges to the global optimum for functions f9–f11 and f13, achieving the second-best result for function f12. TLBO demonstrates improved performance for functions f8–f10, f12, and f13, matching PSC-MTLBO’s results for function f11.

Additionally, AMO exhibits superior performance compared to other algorithms for functions f8f8 and f12, achieving global optimum mean results for functions f9 and f11. GSA also shows notable mean results for function f13 compared to the other algorithms.

The modifications made to the fundamental TLBO algorithm resulted in a significant improvement in PSC-MTLBO’s overall rank, elevating it from 7 to 2 in mean results and from 8 to 3 in standard deviation (SD). However, AMO demonstrates the most exceptional overall performance in both mean and SD metrics.

The overall Friedman rank for functions f8–f13 for PSO, DE, BBO, CS, FA, GSA, ABC, AMO, TLBO, MTLBO, PSC-MTLBO is reported as 9, 5, 8, 11, 10, 6, 3, 1, 7, 4, and 2, respectively. These findings validate that the suggested modifications significantly enhance the algorithm’s exploratory capabilities, especially in challenging multimodal optimization scenarios.

In Table 4, the comparison encompasses mean values, standard deviations (SD), and algorithm ranks for unimodal low-dimensional functions f14–f23, designed to assess algorithm performance. The analysis reveals that PSC-MTLBO achieves the global optimum value for functions f14–f20 and f23. However, DE demonstrates superior results for functions f21 and f22 compared to other algorithms.

TLBO demonstrates enhanced performance for functions f14, f15, and f18–f23 while achieving identical results to PSC-MTLBO for functions f16 and f17. Similarly, MTLBO shows improvement for functions f14, f15, f19, f20, and f23, maintaining identical performance to PSC-MTLBO for functions f16 and f17.

The overall Friedman rank for functions f14–f23 for PSO, DE, BBO, CS, FA, GSA, ABC, AMO, TLBO, MTLBO, PSC-MTLBO is reported as 6, 3, 11, 5, 7, 8, 2, 4, 10, 9, and 1, respectively. The modifications within the basic TLBO significantly elevate the overall mean rank from 10 to 1 in mean results and from 11 to 1 in the overall SD rank for PSC-MTLBO. These results underscore the effectiveness of the proposed modifications in enhancing the algorithm’s performance on unimodal low-dimensional functions, particularly in achieving the global optimum.

Moreover, among the tested algorithms, PSC-MTLBO attains the highest overall ranking as per Friedman’s rank. These outcomes affirm that the proposed modifications considerably enhance the algorithm’s exploration capability.

Results on benchmark suite 2

In this investigation, 23 benchmarks (as displayed in Table 1) were employed to evaluate the efficacy of PSC-MTLBO. Detailed specifications of the benchmarks are outlined in Table 1. The performance of the suggested method was evaluated against GWO, PSO, GSA, FEP, MTLBO, and TLBO. Each PSC-MTLBO, MTLBO, and TLBO underwent 30 independent runs for every benchmark function. GWO, PSO, GSA, and FEP were assessed across all functions with a maximum of 15,000 FE. For consistency in comparison, PSC-MTLBO, MTLBO, and TLBO were also evaluated using the same maximum FE limit. Statistical outcomes, such as mean results and standard deviations, are presented in Table 2.

Upon detailed analysis presented in Table 5, it was observed that PSC-MTLBO demonstrated exceptional performance across a range of benchmark functions. PSC-MTLBO achieved the global optimum mean result for several functions, including f1, f9, f11, f14, f16–f19, f20, f22, and f23. This indicates the algorithm’s strong ability to converge to optimal solutions for these specific functions.

Additionally, PSC-MTLBO outperformed other algorithms in terms of mean results for functions f2, f4, f10, and f12, showcasing its competitive edge in optimization. Comparatively, TLBO showed superior performance for functions f3 and f7, and it achieved the global optimum mean result for functions f11, f16–f18, demonstrating its strengths in specific scenarios.

Interestingly, the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) demonstrated the best performance for functions f15 and f21, and it excelled in functions f16–f19 and f22, showcasing its effectiveness in certain optimization contexts.

Moreover, improvements or identical performances were observed for the Modified TLBO (MTLBO) algorithm in functions f2, f5, f6, and f8–f19, while PSC-MTLBO exhibited improvements in functions f1, f2, f4–f6, and f8–f23 compared to TLBO. This suggests that the modifications made to TLBO, particularly in the form of MTLBO and PSC-MTLBO, have significantly enhanced their optimization capabilities across various functions.

Overall, the results table indicates that among the benchmark functions, PSC-MTLBO, MTLBO, and TLBO reported the best mean solutions in 15, 7, and 6 instances, respectively. PSC-MTLBO showcased superior performance in 10 out of the 25 benchmark functions, securing the top rank among the evaluated methods. These findings highlight the effectiveness of PSC-MTLBO in achieving optimal solutions across a diverse set of benchmark functions, underscoring its potential as a robust and versatile optimization algorithm.

Results on benchmark suite 3

In this section, the assessment of PSC-MTLBO’s performance involves the use of the CEC2005 (Suganthan et al., 2005)43, see Table 6. These functions encompass large-scale global optimization problems classified into unimodal functions (F1–F5), multimodal functions (F6–F12), expanded multimodal functions (F13–F14), and hybrid composition functions (F15–F25). All functions feature a shifted global optimum, deliberately biased away from zero, to prevent search space symmetry.

PSC-MTLBO, MTLBO, and TLBO outcomes are juxtaposed with renowned algorithms from pertinent literature, encompassing PSO, IPOP-CMA-ES, CHC, SSGA, SS-BLX, SS-Arit, DE-Bin, DE-Exp, and SaDE (as discussed in Derrac et al., 2011)44. Mean error values derived from 25 independent runs are outlined in Table 7, computed as |FX—F|, where F represents the optimum fitness and FX represents the recognized global optimum of the function.

The results analysis reveals that PSC-MTLBO stands out by achieving the global optimum for a substantial number of benchmark functions, including F1, F4, F5, F7, F13, F18, and F22–F25. This highlights the algorithm’s robustness and effectiveness in finding optimal solutions across a diverse set of optimization problems.

Comparatively, other methods also demonstrated noteworthy performances. IPOP-CMA-ES, for instance, showed strong performance in functions F1–F3, F6, F8, F11, and F21, indicating its suitability for certain types of optimization tasks. CHC, on the other hand, excelled in functions F10, F14, F16, and F17, demonstrating its effectiveness in different problem domains.

Additionally, SSGA exhibited exceptional performance for function F9, indicating its strength in tackling specific optimization challenges. DE-Exp showcased superiority for functions F19 and F20, highlighting its effectiveness in optimizing certain types of functions. SaDE demonstrated superior results for functions F12, F15, and F24, further illustrating the diversity of algorithmic approaches and their applicability to different optimization scenarios.

In contrast, while TLBO showed improvements across functions F1–F11, and F13–F23, its performance was slightly lower in function F12 compared to PSC-MTLBO. MTLBO, on the other hand, showcased improvements across all functions, with identical performance to PSC-MTLBO in function F1. This indicates that the modifications made to TLBO, particularly in the form of MTLBO and PSC-MTLBO, have significantly enhanced their optimization capabilities across a wide range of functions.

In terms of overall rankings, TLBO secured the 7th position, MTLBO claimed the top spot, and PSC-MTLBO emerged at the pinnacle, underscoring the superior exploratory and exploitative capacities of the proposed approach.

Moreover, Table 7 provides a comprehensive overview of each algorithm’s performance, outlining the counts for their best, 2nd best, and worst results. TLBO, for instance, presented 5 worst solutions out of 25 without any best or 2nd best counts, indicating areas for potential improvement. MTLBO, on the other hand, offered 1 best and 5 2nd best counts, showcasing its strong performance across multiple functions as per Friedman rank. Interestingly, PSC-MTLBO showed no worst results across the benchmark functions, further solidifying its position as a robust and reliable optimization algorithm.

Results of the comparative study

The performance assessment of PSC-MTLBO concerning the optimization of CEC2005 benchmark functions involves a comparison with various meta-heuristics, including AAA, ABC, BA, DE, ACO, HS, MTLBO, and TLBO. Table 8,9,10 showcase the best, mean, and SD values derived from 25 independent runs, each using a maximum of 100,000 FEmax on 10-D functions. Table 11 showcases the results of the Friedman rank test.

The initial functions (F1–F5) in Table 8, categorized as unimodal functions, reveal noteworthy outcomes. PSC-MTLBO, MTLBO, AAA, DE, and HS consistently reach the global optima for function F1. Function F2 sees convergence close to the global optimum by PSC-MTLBO, MTLBO, and ACO with minimal standard deviation. For functions F3–F5, PSC-MTLBO exhibits superior performance, highlighting the enhanced exploration capability and decreased likelihood of falling into local optima traps due to the introduced modifications.

Moving to multimodal functions (F6–F12) in Table 9, diverse performance patterns emerge. For function F6, AAA presents the best mean and SD, with PSC-MTLBO ranking third in mean result, surpassing MTLBO and TLBO. Notably, PSC-MTLBO outperforms other algorithms in functions F7, F9, F10, and F11. Functions F12 and F13 highlight ABC’s better mean performance compared to others, where PSC-MTLBO surpasses its variants. On function F14, HS secures the best mean solution, while PSC-MTLBO and MTLBO take the second and third positions, respectively, in the mean solution. Overall, PSC-MTLBO achieves the highest ranking among the considered algorithms, affirming the improved exploration capabilities from the modifications.

The composition functions (F15–F25) discussed in Table 10, constructed from basic functions, exhibit various algorithmic performances. PSC-MTLBO secures the best mean result among all algorithms for functions F16–F18, F22, F24, and F25, showcasing its prowess. On function F23, PSC-MTLBO performs optimally, despite not being previously tested by other algorithms.

The Friedman rank test in Table 11, excluding function F23, compares the performance of algorithms (AAA, ABC, BA, DE, ACO, HS, TLBO, MTLBO, and PSC-MTLBO) based on the minimum and mean solutions obtained from 25 runs. The overall Friedman rank considering minimum solutions for PSO, DE, BBO, CS, FA, GSA, ABC, AMO, TLBO, MTLBO, PSC-MTLBO is reported as 2, 5, 9, 7, 7, 6, 4, 3, and 1, respectively. Similarly, the overall Friedman rank considering mean solutions for PSO, DE, BBO, CS, FA, GSA, ABC, AMO, TLBO, MTLBO, PSC-MTLBO is reported as 2, 3, 9, 4, 8, 6, 7, 5, and 1, respectively. These outcomes offer valuable insights into the comparative performance of the algorithms, highlighting PSC-MTLBO as the top performer in both minima and mean solutions across the evaluated algorithms.

It asserts PSC-MTLBO’s superiority, ranking first in obtaining minimum and mean solutions among the considered algorithms, followed by AAA and MTLBO.

Results on benchmark suite 4

In this study, 30 benchmarks were introduced in the CEC2014 competition (Liang et al., 2014)45. These functions, classified as unimodal (g1 to g3), multimodal (g4 to g16), hybrid (g17 to g22), and composition (g23 to g30), are summarized in Table 12. The comparison involves 10 methods (IWO, BBO, GSA, HuS, BA, WWO, TLBO, MTLBO, and PSC-MTLBO). Here, 30-dimensions were employed, spanning search ranges of [−100, 100]D. A population size of 50 and FEmax set at 150,000 were considered with 60 runs.

The relative outcomes for the unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, and composition functions within the CEC2014 benchmarks are displayed in Table 13,14,15,16. These tables depict the minimum, maximum, median, and standard deviation (SD) of the fitness.

Table 17 delineates the rank sum of methods across the test functions, relying on the median number. The findings underscore WWO’s exceptional performance for unimodal, multimodal, and hybrid functions, whereas PSC-MTLBO excels in composition functions. PSC-MTLBO secures the second-best rank for unimodal and hybrid functions and the third-best for multimodal functions. Overall, WWO attains the highest ranking, with PSC-MTLBO securing the second rank across the benchmark functions.

In Table 18, the Friedman rank test contrasts PSC-MTLBO with other cutting-edge algorithms, focusing on minimum and median values obtained from 60 runs. Across the unimodal function group, PSC-MTLBO achieves the best median values for function g2, secures the second-best for g1g1, and ranks fifth for g3. While WWO performs the best on functions g1 and HuS on g3, PSC-MTLBO demonstrates the second-best overall performance within this group, surpassing TLBO, MTLBO, and others.

The overall Friedman rank considering minimum solutions for WWO, BA, HuS, GSA, BBO, IWO, TLBO, MTLBO, and PSC-MTLBO is reported as 1, 9, 8, 6, 7, 3, 5, 4, and 2, respectively. Similarly, the overall Friedman rank considering mean solutions for WWO, BA, HuS, GSA, BBO, IWO, TLBO, MTLBO, and PSC-MTLBO is reported as 1, 9, 8, 6, 7, 3, 5, 4, and 2, respectively. These findings underscore the competitive performance of PSC-MTLBO, positioning it as a strong contender among state-of-the-art algorithms for solving unimodal optimization problems.

For multimodal functions, diverse algorithms excel in different functions, with PSC-MTLBO securing second or third-best median values across various functions but not attaining the first rank. However, TLBO’s performance improves in all functions for PSC-MTLBO.

In the hybrid function group, PSC-MTLBO achieves the best median values for function g19, and third-best for g18, g20, and g22. TLBO takes the lead in functions g20 and g21, with WWO leading in g17 and g18. The modifications in TLBO enhance the overall ranking of PSC-MTLBO for multimodal functions.

For the composition function group, PSC-MTLBO secures the best median values for function g25 and ranks second or third for several others. TLBO’s performance enhancement is observed across all functions except g24 when employed in PSC-MTLBO.

Results on truss topology optimization (TTO)

TTO (Savsani et al. 2016; 2017; Tejani et al. 2019; 2018b; Kumar et al. 2022b) is a practical approach for structural design, involving creating a ground structure of all possible element connections and deciding whether to retain or remove these elements. This process is repetitive until the optimum design is achieved. However, maintaining removed bars with small sections can be time-consuming and affect natural frequencies. A rebuilding approach can be used instead. While some research has focused on size optimization with constraints, there is limited study on TTO with natural frequency bounds. Two-stage optimization involves topology and then size optimization, but this may not constantly find the best result. In contrast, the one-stage approach optimizes both concurrently in a single run, which can be more effective for achieving lighter trusses (Tejani et al. 2017; 2018c). This article explores these methods in concurrent TTO, using two real-world problems for demonstration.

The mathematical formulation (Savsani et al. 2016; 2017; Tejani et al. 2019; 2018b; Kumar et al. 2022b) is represented as per Eq. (11):

for weight minimization,

subject to:

where, \(i=\text{1,2},3,\dots \dots ,m; j=\text{1,2},3\dots \dots ,n,\)

\({X}_{i}\)= the i-th design variable;\({\rho }_{i}\)= material density;\({E}_{i}\)= Young’s modulus; \({L}_{i}\)= length of bar;\({\sigma }_{i}\)= stress; \({{\sigma }_{i}}^{cr}\)= critical-buckling stress;\({B}_{i}\)=Binary bit (0 for deleting and 1 for adding the i-th ground bar).

For \({j}^{th}\) node:\({\delta }_{j}\)= nodal displacement;\({b}_{j}\)= node mass.

\({f}_{r}\)= natural frequency, \({r}^{th}\) mode.

comp = compressive.

\({K}_{i}\)= Euler buckling coefficient.

The penalty is adopted from Savsani et al. (2016; 2017), Tejani et al. (2019; 2018b) Kumar et al. (2022b) and represented as per Eq. (12) (13):

In the provided context, \({p}_{i}\) represents the constraint violation value of the ith constraint, while \({p}_{i}^{*}\) indicates its corresponding bound, and q denotes the total number of violated limits. The selection of parameters \({\upvarepsilon }_{1}\) and \({\upvarepsilon }_{2}\) is based on the extent of constraint violation. For this study, \({\upvarepsilon }_{1}\) and \({\upvarepsilon }_{2}\) are both set to 1.5 to analyze their impact on the dynamic balance between diversification and intensification. The 24-bar truss.

Figure 4 illustrates the initial truss test problem, namely, the 24-bar truss and its corresponding truss adopted from Savsani et al. (2016; 2017), Tejani et al. (2019; 2018b) Kumar et al. (2022b). Table 19 presents all the design considerations for the benchmark problem.

24-bar truss11.

Table 20 displays the results of the 24-bar truss structure with discrete sections, found using different algorithms. The best run represents the most favorable outcome from 100 total runs, meeting all constraints. The top results reported by various algorithms are as follows: ALO—147.9755 kg, DA—188.6131 kg, WOA—206.9689 kg, HTS—137.8316 kg, TLBO—121.7832 kg, MTLBO—120.7648 kg, and PSC-MTLBO—120.7648 kg.

Among these, PSC-MTLBO and MTLBO achieve the lowest weight values, followed by TLBO. However, the assessment of the algorithms’ performance is based on structural mass, standard deviation (SD), and mean values. From the results, ALO, DA, WOA, HTS, TLBO, MTLBO, and PSC-MTLBO have mean average values of 207.8352 kg, 261.3511 kg, 371.5226 kg, 177.0808 kg, 181.1404 kg, 139.1551 kg, and 129.0068 kg, correspondingly, with SD values of 36.6120 kg, 54.7229 kg, 87.3270 kg, 29.0488 kg, 37.4737 kg, 11.6130 kg, and 7.1245 kg, respectively.

PSC-MTLBO demonstrates the best performance in achieving the lowest mass mean value and SD value. Therefore, the PSC-MTLBO algorithm is considered the most effective for this test problem.

Figure 5 displays a convergence chart of the mean mass against the iterations. The plot indicates that the mean mass of PSC-MTLBO and MTLBO converges to a better answer related to the others. Additionally, the convergence curves show that the PSC-MTLBO, MTLBO, TLBO, and ALO algorithms converge more rapidly in the initial stages. Despite this, the PSC-MTLBO and MTLBO algorithms exhibit the best values for the final mean mass.

Furthermore, the convergence graph suggests that the efficiency of the PSC-MTLBO algorithm is indeed improved compared to their original versions. The 20-bar truss.

Figure 6 depicts the initial structural test problem, specifically the 20-bar truss and its corresponding basic truss as per Savsani et al. (2016; 2017), Tejani et al. (2019; 2018b), and Kumar et al. (2022b). Table 21 provides an inclusive overview of all the design considerations for this benchmark problem.

20-bar truss11.

Table 22 presents data obtained from different algorithms used to solve the 20-bar truss with discrete sections. ALO, DA, WOA, HTS, TLBO, MTLBO, and PSC-MTLBO yielded the best solutions of 157.1498, 202.6373, 282.4375, 157.1498, 157.1498, 154.7988, and 154.7988 kg, respectively. While MHTS and MTLBO produced the best minimum structural mass, the average and standard deviation values of structural mass are considered benchmarks for all algorithms. The average mass values for ALO, DA, WOA, HTS, TLBO, MTLBO, and PSC-MTLBO are 263.7888, 2.01E + 06, 486.8263, 4.00E + 06, 496.9801, 163.3695, and 160.2449 kg, respectively, with standard deviation values of 48.6449, 1.41E + 07, 108.1432, 1.98E + 07, 1449.7634, 12.6886, and 6.3597, respectively. The PSC-MTLBO algorithm excels in managing the mean mass value, while MTLBO produces the best result. Therefore, the PSC-MTLBO algorithm is superior in terms of convergence rate and accuracy.

Figure 7 illustrates the search history of all tested methods, displaying plots of iterations versus the average mass. The convergence curves indicate that WOA and ALO converge more rapidly initially, followed by PSC-MTLBO and then MTLBO, which ultimately achieve better convergence results. A significant improvement is observed in the modified method compared to TLBO.

Overall, PSC-MTLBO achieves the second-best performance among the nine algorithms across various types of functions, including unimodal, multimodal, hybrid, composition, and real-world functions. PSC-MTLBO and WWO are the best-performing algorithms in these benchmarks. The Friedman rank test confirms PSC-MTLBO and WWO’s top position for minimum and median solutions across the specified functions. PSC-MTLBO improves computational efficiency and scalability across high-dimensional problems by running many sub-classes in parallel, in contrast to classic TLBO. The PSC-MTLBO outperforms TLBO, MTLBO, and other meta-heuristics in terms of function errors, convergence speed, and structural design, according to experimental data on CEC2005, CEC2014, and truss topology optimization.

A comparative analysis of proposed PSC-MTLBO with existing TLBO variants

The PSC-MTLBO has proven to be a valuable optimization method as it tends to perform better than the teaching–learning based optimization and various modifications. As displayed in the benchmark function result exhibited in Table 23 and Fig. 8, the improvement in PSC-MTLBO is from two novel improvements, namely sub-class division strategy and challenger learner’s model, apart from three existing modifications-having the following improvements such as adaptive teaching factors, tutorial-based learning, and self-motivated learning. Under this keyword, this optimization technique-the PSC-MTLBO technique-is proven to significantly yield better performances in benchmark test functions and also real-world optimization problems. The major advantage of PSC-MTLBO is that it minimizes function errors more efficiently than other optimizing techniques. For example, PSC-MTLBO has been nearly flawless with respect to all 23 classical benchmark functions when compared to other optimization techniques. The resulting error rates with PSC-MTLBO were found to be significantly less than that of TLBO46, with the 95% reduction value in function errors. From Sphere and Rastrigin unimodal functions requiring strong global searches, PSC-MTLBO improved results by 94% and 87%. Likewise, these results also proved PSC-MTLBO will not quickly convey it to the anaerobic state. In addition, in multimodal functions such as Griewank and Schwefel, PSC-MTLBO is 36% and 29% more than CPSO-TLBO47 and FATLBO48, respectively, which can show its efficiency in solving and handling complex search spaces in optimization problems. Also, he got 70% improvement in precision for high-dimensional functions such as Ackley and Rosenbrock, demonstrating the higher capacities of exploitation of PSC-MTLBO.

(a) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Sphere function (b) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Rastrigin function (c) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Ackley function (d) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Griewank function (e) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Rosenbrock function (f) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Schwefel function (g) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Schaffer function (h) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Zakharov function (i) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Dixo-Price function (j) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of michalewicz function (k) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Bent Cigar function (l) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Levy function (m) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Step function (n) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Quartic Noise function (o) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of weierstrass function (p) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Brown function (q) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Salomon function (r) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Elliptic function (s) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of perm function (t) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Discus function (u) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Sumsquares function (v) Analysis on proposed PSC-MTLBO over the existing variants of TLBO in terms of Expanded Griewank plus Rosenbrock function.

The PSC-MTLBO is also characterized by a higher convergence rate alongside accuracy, as opposed to the other TLBO versions. The division strategy helps promote search diversity by grouping learners into smaller sub-classes for greater adaptation to the problem landscape. This mechanism offers PSC-MTLBO an escape route from getting stuck in local optima, thereby avoiding a problem often confronted by its counterparts in TLBO and GA-PSO-TLBO49. Therefore, this extra leap in escaping a local optimum made the convergence speed in PSC-MTLBO for harder functions such as Aklay and Weierstrass 35% faster than CATLBO50 at the expense of higher function error. The design helps develop competitive learning dynamics for the challenger learners, thus ensuring dynamic adaptation by the algorithm to promising solutions, thereby strengthening the performance of both local and global searches.

The superiority of PSC-MTLBO is even more evident when exposed to real-life optimization problems, such as truss topology optimizations. It has been able to design lighter and more an economically beneficial structures to the extent of 7.2% than the best-known solutions obtained from the previous TLBO modifications. All these from the fact that this algorithm is self-motivated learning which dynamically varies the learning rate to assure very accurate convergence and robustness in solving structural design problems. Also, the performance of PSC-MTLBO remained stable in diverse optimization landscapes, including unimodal, multimodal, and hybrid functions, while its competitors could not perform efficiently on even a specific type of functions. The results also reveal that the PSC-MTLBO surpasses the traditional TLBO and other modified TLBO variants in accuracy, convergence speed, and higher adaptability in complex optimization scenarios. It is an innovative combination of exploration-enhancing and exploitation-strengthening mechanisms, which empower this optimization approach to generalize across various problems and thus becomes a powerful and scalable optimization approach for the real-world applications.

Wilcoxon signed-rank test results for PSC-MTLBO vs. other TLBO variants

Experimental studies and statistical tests confirmed that PSC-MTLBO significantly outperforms TLBO and any other advanced variants on a wide range of benchmark functions, and this is evident from Table 24. The explanation for this high performance would lie in the two enhancements introduced, namely, the subclass division strategy improving population diversity and avoiding the premature convergence, and the challenger-learner model, incorporating competitive learning dynamics for better adaptability and higher convergence speed. With respect to TLBO comparison, the proposed PSC-MTLBO has consistently outperformed CPSO-TLBO, GA-PSO-TLBO, FATLBO, and CATLBO in minimizing function error rates, improving by 95% over standard TLBO. Moreover, it has demonstrated larger speed of convergence in favor of PSC-MTLBO, most likely reducing computational effort by 35–50%, especially so in situations with complex multimodal high-dimensional functions locked down by other TLBO-based methods. The adaptive teaching factors of the algorithm are the dynamical adjustment mechanisms that will enhance the search behavior by striking a good balance between exploration and exploitation to avoid stalling in the local optima. In addition, statistically significant improvements having p-value < 0.05 were confirmed through the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, demonstrating that the improvements in PSC-MTLBO were not by chance. Further, PSC-MTLBO outperformed the real-world truss topology optimization applications by designing lighter and cheaper structures while significantly reducing weights compared to the best previous solutions by 7.2%. Thus, the evidence presented would establish PSC-MTLBO as a robust, scalable, and highly effective optimization framework that substantially excels over the others in both benchmark and real-world scenarios.

Conclusions

This paper introduces enhancements to TLBO designed to improve its exploration, exploitation, and ability to avoid local optima. By incorporating the number of subclasses and the challenger learners’ model, PSC-MTLBO aims to enhance the fundamental TLBO algorithm’s efficacy in the search process. Additionally, PSC-MTLBO seeks to minimize the risk of getting trapped in suboptimal solutions within a limited search area by implementing a parallel challenger model of the main loop. The algorithm integrates three concepts from prior research (adaptive teaching factor, self-motivated learning, and tutorial-based learning) and introduces two innovative improvements: sub-classes and a challenger learners’ model.

The effectiveness of PSC-MTLBO was evaluated across 23 classical benchmarks, 25 benchmarks from CEC2005, 25 from CEC2014, and 2 TTO problems benchmarked against state-of-the-art methods. Specifically, the results of PSC-MTLBO in CEC2014, compared with other algorithms (WWO, BA, HuS, GSA, BBO, IWO, TLBO, and MTLBO) using the Friedman rank test, indicated its first-rank performance in solving 23 classical benchmark functions. Additionally, the Friedman rank test revealed that PSC-MTLBO ranked first in addressing numeric problems from CEC2005 and second in tackling CEC2014 numeric problems. Also, PSC-MTLBO performs better in solving real-world truss topology optimization problems.

PSC-MTLBO excels over other algorithms, consistently achieving global or near-optimal results across a range of functions. The modifications made to the TLBO algorithm notably enhance PSC-MTLBO’s performance, positioning it as a competitive and promising optimization method for diverse problem sets. The study’s findings underscore the effectiveness and reliability of PSC-MTLBO compared to traditional TLBO, MTLBO, and other algorithms documented in prior research. These enhancements substantially strengthen TLBO’s inherent exploration and exploitation capabilities and help avoid local traps.

A prospective avenue for future research involves extending these proposed methodologies to explore their applicability in recent meta-heuristic algorithms for solving both single and multiple objective optimizations in engineering.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon request to corresponding author.

References

Holland, J. H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems: An Introductory Analysis with Applications to Biology, Control, and Artificial Intelligence (University of Michigan Press, 1975).

Kirkpatrick, S., Gelatt, C. D. & Vecchi, M. P. Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 220, 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.220.4598.671 (1983).

Auger, A.& Hansen, N. A restart CMA evolution strategy with increasing population size In: 2005 IEEE Congr. Evol. Comput. Vol. 2. 1769–1776 https://doi.org/10.1109/CEC.2005.1554902 (2005).

Tejani, G. G., Savsani, V. J., Bureerat, S., Patel, V. K. & Savsani, P. Topology optimization of truss subjected to static and dynamic constraints by integrating simulated annealing into passing vehicle search algorithms. Eng. Comput. 35, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-018-0612-8 (2019).

Kumar, S., Tejani, G. G., Pholdee, N. & Bureerat, S. Multi-objective passing vehicle search algorithm for structure optimization. Expert Syst. Appl.169, 114511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2020.114511 (2021).

Singh, P., Kottath, R. & Tejani, G. G. Ameliorated follow the leader : Algorithm and application to truss design problem. Structures42, 181–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.istruc.2022.05.105 (2022).

Dong, H., Wang, P., Fu, C. & Song, B. Kriging-assisted teaching-learning-based optimization (KTLBO) to solve computationally expensive constrained problems. Inf. Sci. 556, 404–435 (2021).

Ma, Y., Zhang, X., Song, J. & Chen, L. A modified teaching–learning-based optimization algorithm for solving optimization problem. Knowl.-Based Syst. 212, 106599 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. An enhanced teaching-learning-based optimization algorithm with self-adaptive and learning operators and its search bias towards origin. Swarm Evol. Comput.60, 100766 (2021).

Dastan, M., Shojaee, S., Hamzehei-Javaran, S. & Goodarzimehr, V. Hybrid teaching–learning-based optimization for solving engineering and mathematical problems. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 44(9), 431 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Strengthened teaching–learning-based optimization algorithm for numerical optimization tasks. Evol. Intel. 17(3), 1463–1480 (2024).

Rao, R. V., Savsani, V. J. & Vakharia, D. P. Teaching-learning-based optimization: A novel method for constrained mechanical design optimization problems. Comput.-Aided Des.43, 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cad.2010.12.015 (2011).

Rao, R. V. & Patel, V. An improved teaching-learning-based optimization algorithm for solving unconstrained optimization problems. Sci. Iran. 20, 710–720. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scient.2012.12.005 (2012).

Patel, V. K. & Savsani, V. J. A multi-objective improved teaching–learning based optimization algorithm (MO-ITLBO). Inf. Sci. (Ny). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2014.05.049 (2014).

Wang, L. et al. An improved teaching-learning-based optimization with neighborhood search for applications of ANN. Neurocomputing143, 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2014.06.003 (2014).

Savsani, V. J., Tejani, G. G. & Patel, V. K. Truss topology optimization with static and dynamic constraints using modified subpopulation teaching–learning-based optimization. Eng. Optim.48, 1–17 (2016).

Savsani, V. J., Tejani, G. G., Patel, V. K. & Savsani, P. Modified meta-heuristics using random mutation for truss topology optimization with static and dynamic constraints. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 4, 106–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305215X.2016.1150468 (2017).

Tejani, G. G., Savsani, V. J. & Patel, V. K. Modified sub-population teaching-learning-based optimization for design of truss structures with natural frequency constraints. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach.44, 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/15397734.2015.1124023 (2016).

Tejani, G. G., Savsani, V. J., Patel, V. K. & Bureerat, S. Topology, shape, and size optimization of truss structures using modified teaching-learning based optimization. Adv. Comput. Des. 2, 313–331. https://doi.org/10.12989/acd.2017.2.4.313 (2017).

Kumar, S., Tejani, G. G., Pholdee, N., Bureerat, S. & Jangir, P. Multi-objective teaching-learning-based optimization for structure optimization. Smart Sci. 10(1), 56–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/23080477.2021.1975074 (2022).

Savsani, V., Tejani, G. G. & Patel, V. K. Truss optimization: A metaheuristic optimization approach (Springer Nature, 2024).

Kalphana, I. & Kesavamurthy, T. Crossover teaching learning based optimization for channel estimation in MIMO system. Expert. Syst. Appl.249, 123532. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ESWA.2024.123532 (2024).

Wolpert, D. H. WG Macready No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1(67), 82. https://doi.org/10.1109/4235.585893 (1997).

Su, T.-J. et al. Design of infinite impulse response filters based on multi-objective particle swarm optimization. Signals5(3), 526–541. https://doi.org/10.3390/signals5030029 (2024).

Sinha, N., Chakrabarti, R. & Chattopadhyay, P. K. Fast evolutionary programming techniques for short-term hydrothermal scheduling. IEEE Trans. Power Syst.18, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPWRS.2002.807053 (2003).

Ahmad, M. F., Isa, N. A. M., Lim, W. H. & Ang, K. M. Differential evolution: A recent review based on state-of-the-art works. Alex. Eng. J.61(5), 3831–3872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aej.2021.09.013 (2022).

Xiao, W., Li, G., Liu, C. & Tan, L. A novel chaotic and neighborhood search-based artificial bee colony algorithm for solving optimization problems. Sci. Rep.13(1), 20496. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44770-8 (2023).

Mittal, H., Tripathi, A., Pandey, A. C. & Pal, R. Gravitational search algorithm: A comprehensive analysis of recent variants. Multimed. Tools Appl. 80(5), 7581–7608. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-020-09831-4 (2021).

Xiong, Y., Zou, Z. & Cheng, J. Cuckoo search algorithm based on cloud model and its application. Sci. Rep.13(1), 10098. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37326-3 (2023).

Karthikeyan, M., Manimegalai, D. & RajaGopal, K. Firefly algorithm based WSN-IoT security enhancement with machine learning for intrusion detection. Sci. Rep.14(1), 231. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-50554-x (2024).

Qiu, Y., Yang, X. & Chen, S. An improved gray wolf optimization algorithm solving to functional optimization and engineering design problems. Sci. Rep.14(1), 14190. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-64526-2 (2024).

L. Abualigah et al. Animal migration optimization algorithm: Novel optimizer, analysis, and applications In Metaheuristic Optimization Algorithms: Optimizers, Analysis, and Applications, Morgan Kaufmann pp. 33–43 (2024).

Ghoshal, S. & Sundar, S. A steady-state grouping genetic algorithm for the rainbow spanning forest problem. SN Comput. Sci.4(4), 321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42979-023-01766-5 (2023).

Phocas, MC., Tornabene, F., Charalampakis, AE., et al A Comparative Study of Differential Evolution Variants in Constrained Structural Optimization. Front Built Environ | www.frontiersin.org 1:102. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbuil.2020.00102 (2020).

Korzeń, M. & Gisterek, I. Applying ant colony optimization to reduce tram journey times. Sensor https://doi.org/10.3390/s24196226 (2024).

Yuan, C. et al. Bat algorithm based on kinetic adaptation and elite communication for engineering problems. CAAI Trans. Intell. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1049/cit2.12345 (2024).

Turkoglu, B., Uymaz, S. A. & Kaya, E. Chaotic artificial algae algorithm for solving global optimization with real-world space trajectory design problems. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-024-09222-z (2024).

Rahmani, Y., Shahvari, Y. & Kia, F. Application of invasive weed optimization algorithm for optimizing the reloading pattern of a VVER-1000 reactor (in transient cycles). Nucl. Eng. Des. 376, 111105. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NUCENGDES.2021.111105 (2021).

Simon, D. Biogeography-based optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 12, 702–713. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEVC.2008.919004 (2008).

Oftadeh, R., Mahjoob, M. J. & Shariatpanahi, M. A novel meta-heuristic optimization algorithm inspired by group hunting of animals: Hunting search. Comput. Math. Appl.60, 2087–2098. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.camwa.2010.07.049 (2010).

Zheng, Y.-J. Water wave optimization: A new nature-inspired metaheuristic. Comput. Oper. Res.55, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2014.10.008 (2015).

Tejani, G. G., Savsani, V. J., Patel, V. K. & Mirjalili, S. An improved heat transfer search algorithm for unconstrained optimization problems. J. Comput. Des. Eng.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcde.2018.04.003 (2018).

Suganthan, PNN., Hansen N., Liang, JJ., Deb, K. Chen, Y.-P., Auger, A. & Tiwari, S. Problem definitions and evaluation criteria for the CEC2005 special session on real-parameter optimization In Proc. IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation 1–50 (2005).

Derrac, J., García, S., Molina, D. & Herrera, F. A practical tutorial on the use of nonparametric statistical tests as a methodology for comparing evolutionary and swarm intelligence algorithms. Swarm Evol. Comput.1, 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.swevo.2011.02.002 (2011).

Liang, JJ., Qu, BY. & Suganthan, PN. Problem definitions and evaluation criteria for the CEC2014 special session and competition on single objective real- parameter numerical optimization, Tech. Rep. 201311, computational intelligence laboratory, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China (2014)

Rao, R. V., Savsani, V. J. & Vakharia, D. P. Teaching–learning-based optimization: A novel method for constrained mechanical design optimization problems. Comput.-Aided Des.43(3), 303–315 (2011).

Azad-Farsani, E., Zare, M., Azizipanah-Abarghooee, R. & Askarian-Abyaneh, H. A new hybrid CPSO-TLBO optimization algorithm for distribution network reconfiguration. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst.26(5), 2175–2184 (2014).

Cheng, M. Y. & Prayogo, D. Fuzzy adaptive teaching–learning-based optimization for global numerical optimization. Neural Comput. Appl. 29, 309–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-016-2449-7 (2018).

Yun, Y., Gen, M. & Erdene, T. N. Applying GA-PSO-TLBO approach to engineering optimization problems. Math. Biosci. Eng.20(1), 552–571 (2023).

Surender Reddy, S. Clustered adaptive teaching–learning-based optimization algorithm for solving the optimal generation scheduling problem. Electr. Eng. 100, 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00202-017-0508-4 (2018).

Shabanpour-Haghighi, A., Seifi, A. R. & Niknam, T. A modified teaching–learning based optimization for multi-objective optimal power flow problem. Energy Convers. Manage.77, 597–607 (2014).

Yu, K., Chen, X., Wang, X. & Wang, Z. Parameters identification of photovoltaic models using self-adaptive teaching-learning-based optimization. Energy Convers. Manage. 145, 233–246 (2017).

Acknowledgement

The author extends the appreciation to the Deanship of Postgraduate Studies and Scientific Research at Majmaah University for funding this research work through the project number (R-2025-1869).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.G.T. : Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Conceptualization, Visualization, Investigation, Validation; S.K.S: Revision, Funding, Review, Editing; S.M: Revision, Funding, Review, Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tejani, G.G., Sharma, S.K. & Mishra, S. Parallel sub class modified teaching learning based optimization. Sci Rep 15, 31867 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10596-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10596-9