Abstract

Microgrid frequency control faces challenges due to load fluctuations and the intermittent nature of Renewable Energy Sources (RESs). The Load Frequency Control (LFC) scheme has been a profoundly investigated matter for decades for achieving a consistent frequency. This study introduces a novel cascaded Integral-Proportional-Proportional Derivative with Filter (I-P)-PDN controller designed to mitigate frequency deviations in microgrids incorporating Photovoltaic (PV) and Wind Turbine Generator (WTG), Fuel Cells (FCs), Electric Vehicles (EVs), Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), and Diesel Engine Generators (DEGs). To optimize the controller’s parameters, the recently introduced Black-winged Kite Algorithm (BKA) is employed for its superior search efficiency and quick convergence. Simulation results show that the (I-P) cascaded PDN controller significantly outperforms existing controllers, such as PID, and PI-based models, by reducing frequency deviations, improving settling time, and minimizing overshoot and error indices. There is notable 77% reduction in overshoot (OSH) and 52% decrease in undershoot (USH) in tie-line power variations. Moreover, the Integral Absolute Error (IAE) is reduced by 42.3%, the Integral Time weighted Absolute Error (ITAE) by 85%, and the Integral Squared Error (ISE) by 98%. The study also examines the role of EVs as flexible energy storage, demonstrating their contribution to system resilience and stability. This approach offers a robust solution for effective frequency regulation in modern microgrids, ensuring reliable performance in dynamic conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and challenges

The growing need of energy utilization globally underlines the insistence of transitioning from limited, non-renewable energy resources such as fossil fuels to RESs, like wind, solar, and hydropower1. These substitutes energy sources offer a consistent and sustainable and supportable solution and impact the reduction in emission of CO2 and control the effects of climate change2. The two common renewable energy sources that is wind and solar are advantageous due to having less operational costs and can be easily use for producing energy locally thus increasing the energy security and resiliency against disturbances and interruptions3. However, RESs’ integration and participation into power grids arose challenges of managing and stabilizing intermittent energy generation. The transition of traditional power sources maintaining the grid inertia to RESs causes frequency excursion and variations4. According to the International Energy Agency’s forecast, which reveals the substantial increase in photovoltaic and wind power capacity, surpassing the traditional energy sources within next decade5. Hence, tackling of frequency variations issues are critical for fruitful integration of RESs. The energy mix of RESs and DGs in the form of microgrid provide resilient power to the system load6. According to International Renewable Energy Agency (IREA) the power generation capacity of RESs globally reached to 2537 GW with share of 1190GW, 623 GW, 586 GW, 124 GW, and 14 GW and 500 MW by hydropower, wind, PVs, bioenergy, geothermal, and marine energy resources7,8. Due to climatic factors solar irradiation and wind speed variations causes unpredictable weather conditions resulting in intermittent power generations by RESs9. Thus, the frequency oscillation occur due to unpredictable power generation of RESs and stochastic nature of loads10,11. Besides renewable energy sources, electric vehicles are an emerging trends in ecosystem-favored cars productions in automotive industry12. EVs technology contribute to gasoline consumption and greenhouse gas emissions reductions. The EVs are linked to microgrid or conventional power grid over distribution network as flexible load allowing two-way power either to or from the grid13,14,15. The EVs batteries serves as mobile energy storage banks support the RESs integration and supplies stored energy during peak load thus improving power system sustainability16. The RESs and energy storage sources and other Distributed Generations (DGs) sources are integrated in the form of islanded microgrid (IµG), grid connected mode or interconnected microgrids. The power in islanded mode is shared to the local loads. The µG integrated with various AC and DC power sources such as PVs, wind turbines, and energy storage banks, permits power sharing in networked multi-microgrids configuration17. These systems boost up the grid reliability, improve resilience and benefiting maximum power accessibility. However, islanded and multi-µGs suffer challenges with specific to frequency stability and regulation issues due to isolation of IµG from main grid, and intricacy in coordination of multi-µGs due to intermittent nature of RESs and EVs. The erratic behavior of power generation of PV and wind turbines results in mismatching the supply and demand in µGs18,19. Hence, the frequency stabilization and inertia response may be lost due to excessive penetration of RESs in µGs. In these scenarios even a minor fluctuation in µG frequency led to disruptions20. Therefore, it appears critical to implement appropriate control strategies in isolated and interconnected µGs to enhance the power system inertia and frequency stability. In order to die out the disturbances in frequency of µG, the two controlling procedures are commonly used for DGs in microgrids. One is primary level of hierarchical or primary loop local control21. The secondary loop control compensates voltage and frequency variations caused by primary loop control and damp tie line power deviations in interconnected µGs22. Therefore, a most sound frequency control strategy is needed for frequency stabilization of microgrids to ensure reliable delivery of electric power. In this research a (I-P)-PDN controller is proposed for secondary level control strategy for islanded and interconnected microgrids. The control strategy employs a novel nature inspired metaheuristic optimization technique, Black-winged Kite Algorithm (BKA) for controllers’ parameters tuning.

Literature review

In order to confront the major challenge of frequency regulation in microgrids, scientists and researchers have provided a lot of assistance and effort. For maintaining frequency within permissible limits and balanced tie line power in interconnected microgrids, load frequency controllers have been required23. In the past, frequency control techniques have utilized controllers such as proportional integrals and proportional integral derivatives due to their simplicity and simplicity to implement. For the investigation of nonlinear and uncertain power systems, the adjustment of a PID controller can be a cumbersome process, and determining the optimum gains involves a lot of computation and experimentation. Improved performance has been achieved through advanced controllers like double derivatives (DD) and integral double derivatives (IDD). Different optimization algorithms such as Bacterial Foraging-based Optimizer Algorithm (BFOA), have been used for fine tuning the parameters, leading to more efficient LFC strategies23,24. Jaya based optimized model predictive control for frequency regulation in multi-area power system under nonlinearities circumstances an TLBO-LMI based optimized PI controller for three areas reported in25,26. A robust FO-Multistage PD/(1 + PI) controller is optimally implemented using an improved Sine Cosine Algorithm for frequency regulation in an isolated AC microgrid facing renewable-induced intermittencies27.Further, control strategy employing like proportional integral-proportional derivative (PI-PD)28, PD-PI29, type-2 (fuzzy-PID)30 controllers are employed to lessen frequency deviation in microgrid. Various cascaded controller types have been used for load frequency regulation31. The Crow Search Algorithm (CSA) based optimization of Type-2 Fuzzy Cascaded PI Fractional Order (T2F-CPIF) controller improving inter areas power and frequency regulation in complicated power grids having disturbances reported in32. The Quassi-Oppositional Path Finder Algorithm (QO-PFA) based optimization of Fractional Order Type-2 Fuzzy Controller (FO-T2FC) results in enhanced frequency regulation against renewable intermittency compared to Type-1 fuzzy and classical PID controllers presented in33. The Type 2-fuzzy (T2F) controller, optimized by discrete water cycle algorithm enhances frequency stability in comparison to classical PID controllers presented in34. A Fuzzy Type-2 PSS tuned with Modified Crow Search Algorithm effectively regulating and stabilizing frequency in isolated microgrids with electric vehicles under renewable uncertainties. It outperforms classical PID and fuzzy based controllers in dynamic circumstances35.

Recent literature studies36 explore a dual-controller cascade strategy with PIDD2 (Proportional Integral Derivative, Double Derivative) controller framework for frequency fluctuations mitigation in two-area tied power system37. The cascaded control strategy employing Integral-Tilted Proportional Fractional Order Derivative (I-TPFOD) controller was introduced using Satin Bowerbird Optimizer having built in novel integral-square error cost function38. Similarly, a dual-controller method with Particle Swarm Optimizer (PSO) was introduced utilizing an integrator for frequency regulation and proportional-integrator for virtual inertia control of interconnected grids39. The FOPTID + 1 control strategy for LFC employing Global Neighborhood Algorithm (GNA) for parameters optimization was introduced40. For load-frequency regulation and management of power system, numerous control approaches have been adopted using sliding mode controllers41, adaptive model predictive control (AMPC) for two area power system with one isolated microgrid in42 model predictive control reference in43, linear-matrix inequality44, resilient control methods45, data-driven controllers46, impact of simultaneous false data injection attacks (FDIAs) on microgrid’s (LFC), a strategy is implemented that integrates an unknown input observer (UIO) with a Reinforcement Learning-based Policy Gradient controller to ensure frequency security under disturbances in47, and Fuzzy Logic based Control referenced as48. The Fractional Order-Fuzzy power system stabilizer controller, fine-tuned with advanced sine-cosine algorithm significantly enhanced frequency regulation in response to EVs and intermittency of RESs in49. The grid to vehicle (G2V) and vehicle to grid (V2G) services with different conditions lessening the maximum demand, operational costs, and demand mismatches presented in50. The enhanced whale optimization algorithm based tuning of classical PID outperformed compared to simple whale optimization algorithm under several restraints and disturbances51. Cascaded load frequency control technique employing fractional order proportional integral derivative accelerated cascaded fractional order integral derivative with filter (FOPIDA-FOIDN) control was presented52 using hybrid optimizer Artificial Gorilla-Troops (AGTO) and Equilibrium Optimizer (EO) HGTOEO. Additionally, the control strategy for LFC employing hybrid controllers merging fractional order proportional integral derivative (FOPID) and Tilted Integral Derivative (TID), termed Fractional Order Tilted Integral Derivative (FOTID), parameters were refined with Manta-Ray-Foraging (MRFO) algorithm53, and PFOTID with artificial-ecosystem optimizer control strategy developed in54, and FOPID based AGC strategy optimized via imperialist competitive algorithm (ICA) in55. An intelligent- fractional order integrator (iFOI) LFC method with Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) and Fractional Order PID-Accelerated (FOPIDA) controllers for maritime microgrid frequency stability, was introduced in56,57.A new non-linear Proportional Integral LFC strategy with Dandelion Optimizer algorithm (DOA) was employed for single area electric grids58, PI and PID LFC strategy for multiple sourced based microgrid systems using Artificial Rabbit Optimizer algorithm (ARO) for parameters tuning59. A FOPIDN-(1 + PIDN) controller optimized with Grey wolf Optimizer for frequency regulation of power systems integrated with renewable energy sources and electric vehicles with superior performance reported in60. FOPIDN-FOPDN LFC strategy tuned with Selfish Herd Optimizer (SHO), proposing superiority of PSO technique for five area tied grids frequency stabilization by studying impact of redox-flow batteries61. Aforementioned research literature survey reveals that the selection choice of the control is equally important like that of controller parameters. The introduction and implementation of evolutionary algorithms techniques as controller’s parameters optimizers brought significance improvement to handle the frequency regulation problems in the microgrids with different distributed generation sources. Impressive modern optimization methods are implemented for controllers’ parameters tuning to accomplished the obscurity of control techniques. As an illustration, the authors implemented following optimization methods: Self-Tuned Algorithm (STA)24, Bull-Lion Optimization (BLO)62, Chaos Game Optimization (CGO)63, modified multiverse optimizer64, and Sunflower optimization algorithm (SOA) and Ant Colony Optimization (ACO)65. Meta-heuristic optimization techniques are proven as a best solution to complex nature problems having limitations, constraints and other optimization challenges in the microgrid (µG) domain. They are stimulated by natural phenomena such as genetic evolution, and diverse animal behaviors. Meta-heuristic optimization employs random, local, and global search tools to find optimum solution of problem. The present study presents a recently introduced a nature inspired metaheuristic algorithm called the black-winged kite algorithm that draws inspiration from hunting and migration behavioral patterns of small prey bird ‘Black-winged Kite’ for tuning the parameters of proposed (I-P)-PDN controller. The black-winged kite has blue gray upper body and lower white. The algorithm is developed based on the monitoring the hunting strategy, its energy foraging behavior and hovering capabilities. The black -winged kite hovers over specific areas to explore prey, with precisely locating and exploiting the prey prior to diving. The hovering initiates global search phase to explore potential solutions. The algorithm aims to reduce the computational costs by leveling the exploration and exploitation, prevent the redundant computation and dynamically reduce the step size improving the adaptability in the uncertain problems. The Black-winged Kite Algorithm (BKA) incorporates both the Cauchy mutation mechanism and a leader-based strategy to improve its global search capabilities and accelerate convergence. This innovative optimization approach demonstrates an effective balance between global exploration and local exploitation. Empirical evaluations show that BKA outperforms alternative algorithms in 66.7%, 72.4%, and 77.8% of instances when benchmarked against the standardized test of CEC-2022 and CEC-2017. Furthermore, its application to engineering design problems underscores its practical efficacy in addressing constrained real-world challenges, thereby highlighting its strong computational efficiency and competitive performance relative to contemporary optimization methodologies66. The detailed literature survey is shown in Table 1.

Research contribution and motivation

The authors are motivated to propose a novel (I-P)-PDN controller for secondary loop controller for islanded and interconnected microgrids. The proposed controller has an additional signal (Po) support. Moreover, a black-winged kite algorithm is employed for optimization of proposed controller’s parameters. For improving frequency control problem under stochastic nature of RESs, EVs with battery capacity in term of saturation limits are added to the networked microgrids. The communication delay of 1µs is considered for IµG and interconnected microgrid in area-1. The research contribution is summarized as follow;

-

(I-P)-PDN controller optimizes frequency stability in RES and EV-based microgrids.

-

Comparison of proposed controllers with PID and FPDN-FPTID using performance indices.

-

BKA outperforms compared to DO, PSO, and TLBO and other optimization algorithms.

-

Evaluating proposed controller’s resilience and flexibility in worst-case scenario.

-

Introducing BKA for fine-tuning controllers in diverse microgrids configurations.

Organization of paper

The paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 describes structure, block diagram and modeling of IµG and interconnected µGs. Section 3 details about the implementation of proposed control strategy, objective function formulation and development of proposed controller and black-winged kite algorithm. Section 4 covered the simulation results and discussion for proposed controller (I-P)-PDN. Section 5 covered the simulation results of interconnected microgrids, which is followed by sensitivity analysis at Sect. 6. The stability analysis at Sect. 7. The Sect. 8 details about conclusion and future recommendations.

Modeling of islanded and interconnected microgrids

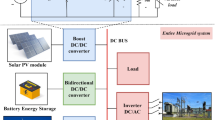

In the proposed islanded microgrid, distributed generations (DGs) including FCs, BESSs, DEGs, PVs, WTGs and EVs are integrated. Figure 1 shows the mathematical modelling of Islanded microgrid. The microgrids parameters and their nominal values are given in appendix A.

Mathematical modeling of battery energy storage source

The battery energy storage system consists of battery banks operating with the nominal operating region irrespective of the constraints. T3 is DC/AC inverter time constant, T1 is the measurement time constant and T2 is the delay time constant67. The change in power of BESS for control signal is given in Eq. (1).

Mathematical modeling of diesel generator

The diesel engine generator provide constant and rapid source for power supply to the load and a typical DEG has constraint like inertia delay (T7), governor time constant (T8) and turbine time constants (T9)67. The transfer function model of DEG is given in Eq. (2).

Mathematical modeling of fuel cell

The fuel cell model has (DC/AC) inverter with time constant (T5), measurement delay (T4) and interconnection blocks (T6). The transfer function model of fuel cell for control signal (\(\:\varDelta\:u)\:\)is expressed as follows in Eq. (3)67.

Mathematical modeling of wind turbine generator

The wind turbine model use wind velocity to produce electric power. The generalized power for wind turbine is defined in Eqs. (4-4c)68.

Where PWTG is wind turbine’s output power, V wind’s rated speed, A is rotor’s swept area, and Cp is performance coefficient of rotor’s blades69. The wind turbine parameters are given in appendix B.

Mathematical modeling of photovoltaic

The photovoltaic generate intermittent power due to variations of solar irradiance (\(\:\varnothing\:\)). However, still it provides resiliency to the power system, supplying the load. The photovoltaics power can be presented as below in Eq. (5)70.

Where Ta is ambient temperature (°C), A is surface area (m2), \(\:\varnothing\:\) is solar irradiance (W/m2), \(\:\gamma\:\) solar panel efficiency, usually in range of 09 to 12%. The modeling parameters for 30 kW PV power71 are given in appendix C.

Mathematical modeling of electric vehicle

The present study explores the strategic deployment of electric vehicles (EVs) as dynamic, flexible loads within the broader framework of frequency regulation. Rather than isolating individual charging strategies, the focus is placed on the collective behavior of EVs, which can be effectively modeled as a distributed network of Mobile Energy Storage Units (MESUs). This abstraction enables a system-level perspective where EVs contribute meaningfully to demand-side energy management and grid stability. Through Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) integration, EVs can discharge stored energy back into the grid, thereby providing ancillary services such as frequency stabilization. The efficacy of V2G operations depends significantly on the state of charge (SoC) of each vehicle’s battery. In this context, a standard operating SoC of 85% is maintained, allowing a ± 5% tolerance range to ensure consistent availability for grid services. Furthermore, to safeguard battery health over time, a target SoC ceiling of 90% is respected to mitigate degradation caused by frequent deep cycling72. For practical utility, particularly to accommodate imminent travel needs, the SoC is never permitted to fall below 80%, ensuring sufficient charge for mobility purposes while allowing limited discharge flexibility for V2G support. In addition to discharging capabilities, EVs are also exploited as flexible charging loads, referred to as Grid-to-Vehicle (G2V) interactions. This controlled charging mechanism enables EVs to absorb surplus grid energy during periods of low demand or high generation, effectively acting as an energy sink. The aggregate effect of coordinated EV fleets becomes a powerful tool in managing load profiles, especially in complex power systems incorporating multiple sources. To facilitate this role, an aggregated microgrid model is employed, wherein a fleet of EVs responds to centralized load frequency control (LFC) signals that regulate SoC targets in real-time. EVs support frequency regulation through bidirectional power flow. Load frequency control signal is input to the EVs and the discharging and charging power is the output represented by ∆PEVs1 and ∆PEVs2 in area-1 and 2 respectively. The detail model of PEVs is presented35,72. They function as flexible loads, enabling real-time energy adjustments. The process is governed by the energy control signal Econtrol (t). This represents the total controllable energy of the EV fleet, based on the Total Energy Model. EVs participate in frequency regulation as long as Econtrol satisfies below condition in Eq. (6)49.

The Econtrol is controlled energy of PEVs. The minimum and maximum energy control can be expressed in term of battery capacity (CkWh) and Ncontrol by Eqs. (7) and (8).

Where Ncontrol indicates the quantity of EVs managed. The Ncontrol can be expressed below;

Ninitial denotes initial counting of PEVs and Ncontrol_in denotes number of EVs transit from charging condition to controllable condition, Nplug_out denotes number of EVs fully charged and in driving condition. The transfer function for EVs model is given as follows in Eq. (10).

Where Tev and Tinv are EVs and inverter time constants respectively. The inverter capacity is denoted by CkW.

Proposed control strategy

This section explains the proposed control strategy, proposed controller structure and its parameters optimization using BKA optimization and the advantages of dual loop controllers over single loop controllers like PI, PID etc. Conventional PID controller is one of the most flexible controllers providing the robustness and effective response34. Attaining the stability and reliability of power system to regulate the frequency, it is necessary to fine tune the controller with appropriate optimization technique. A controller should be designed such that it can handle disturbances35, show robustness to intermittent sources. Equation (11) illustrates transfer function model of classical PID controller in s-domain73. In comparison to one loop controllers, the dual loop controllers are superior in sense that inner loop not only set points, for second stage controller but it regulates the system inner process38. The two-loop process occur in sequential way.

The proposed controller consists of an (I-P) controller making an inner loop with support input signal (Po) as feedback to the PDN controller and stage two loop of final output feedback to (I-P) controller. The proportional gain is placed in feedback and integral controller in feed-forward path. The transfer function model of (I-P) controller is given by Eq. (12)74. The I-P controller has two gains, Kp1 and Ki. The second stage controller PDN has three gains Kp2, Kd and filter coefficient N. The controlled signal \(\:{\text{u}}_{1-\text{P}\left(\text{s}\right)}\) of (I-P) controller, transfer function of PDN controller and final controlled signal C(s) of two stage controller is given by Eqs. (12), (13) and (14) respectively75. Figure 2, shows the proposed controller block.

Objective function and problem formulation

The LFC controller performance dependent on the selection of the objective function (OF). Different multi-objective functions have been proposed in previous studies for reduction in frequency deviations for islanded and interconnected µGs. In this research performance indices ITAE, ISE, ITSE and IAE are used to demonstrate the efficacy of the proposed control strategy using three metaheuristic algorithms, Lyrebird Optimization Algorithm (LOA), Jellyfish Searching Optimization (JSO) and Black-winged Kite Algorithms. Population size of 30 No’s of Lyrebirds, crossover of 0.8, mutation rate and standard deviation of 0.1 is used for LOA. The population size for JSO and search agents for BKA is set to 30 No’s. The iterations are taken 500 kept same for optimization process.

The LOA and JSO can rapidly reach near the optimal solutions in the premature stages of optimization process. Thus, attaining the fast convergence. However, this premature convergence makes the algorithm getting trapped in local optima without the thorough exploration of global search space. In comparison the BKA, slowly converges, maintaining the better equilibrium between exploration and exploitation. The BKA maintains population diversity and integrates strategies to escape local optima, thus making it able to search the solution space more thoroughly. This led to final superior solutions, specifically, in complex or multimodal optimization problems. In this context, although BKA may take slightly more time than LOA and JSO to reach convergence, however, it often outperforms LOA and JSO in terms of solution quality, making it a more robust choice for finding the global optimum. The performance indices and controller’s gain maximum and minimum range are given by Eqs. (15), (16), (17), (18) and (19)76,77,78.

The lower bound limit for (\(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}},\:{\text{K}}_{\text{p}1}^{\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}},{\text{K}}_{\text{p}2}^{\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}},{\:{\text{K}}_{\text{d}}^{\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}}\:,\text{N}}^{\text{m}\text{i}\text{n}})\:\)is (0, 0, 0, 0) and upper bound for (\(\:{\text{K}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}},\:{\text{K}}_{\text{p}1}^{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}},\:\:{\text{K}}_{\text{p}2}^{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}\:,\:\:{\text{K}}_{\text{d}}^{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}},\:{\text{N}}^{\text{m}\text{a}\text{x}}\)) is (11, 5, 4, 0.3, 1000).

The black-winged kite algorithm

The black-winged kite (BK) is a bird characterized with upper body blue-gray in color, lower body part is white. The predator prey relation and migration behavior are their prominent characteristics. They eat and survive on tiny mammal, birds and reptiles and strong flying potentials, and can get an unexpected success in hunting process79. The author introduced a new algorithm modeled based on inspiration from migration and hunting skills of the black-winged kites66. The Black-winged Kites algorithm consists of three phases initialization, attacking and migration.

Initialization phase

While initialization of population in BKA, the primary stage is a set of random solution. The location of each black-winged kite can be given in matrix form by Eq. (20). While Eqs. (21), (22) and (23) represents the random populations, the best solution and the initial populations respectively.

Where BKub and BKlb are upper and lower bounds of ith black-winged kites, the potential solutions can be represented by pop. The dim is given problem’s dimension and initial population can be represented by XL.

Attacking behavior

Black-winged kites (BKs) adjust their position in accordance to the wind speed, during fight and flying at high altitude for searching the prey, and abruptly dive and attacking on prey. The This attacking approach comprises of several attacking actions and behaviors for global exploration and search. The BKs attacking behavior can be represented by mathematical expression by Eqs. (24) and (25)66.

Among them, \(\:{\text{y}}_{\text{t}}^{\text{i}\text{j}}\) and \(\:{\text{y}}_{\text{t}+1}^{\text{i}\text{j}}\), denote the position of ith (BK), in the jth dimension in tth and iterations (t + 1) th, r can be any random value between 0 and 1, p = 0.9, T is maximum iterations, and t is current iteration number.

Migration behavior

The BKA imitates complicated migration behavior of BKs in exploitation phase. Birds migrate due to climate change and availability of food and other factors. Lead birds often play vital role in migration initiation to accomplishment. The Mathematical expression for migration action of (BKs) is given by Eqs. (26) and (27)66.

\(\:{\text{L}}_{\text{t}}^{\text{i}}\) is BKs leading scorer in jth dimension in tth iteration, and \(\:{\text{y}}_{\text{t}}^{\text{i}\text{j}}\) and \(\:{\text{y}}_{\text{t}+1}^{\text{i}\text{j}}\:\)are the location/position of the ith BKs in jth dimension in t and (t + 1) th iteration steps, respectively. Where C(0,1) is Cauchy’s mutation80. Fi is current position by any BK in jth dimension in t iteration. Fri is fitness value of random position obtained by any BKs in t iteration in jth dimension. The mono-dimensional Cauchy distribution with probability density function is given by Eqs. (28) and (29)66.

The flow chart for the BKA algorithm is shown in Fig. 3.

Simulation results and discussions

In this research, a load frequency response model for a microgrid in Fig. 1 is simulated in MATLAB R2024/Simulink environment with Intel Core i5-1235U, 12th Generation RAM: 16 GB, Windows pro-11). Initially, the simulation is conducted with the controllers already proposed and presented in the literature. The performance comparison of proposed controller (I-P)-PDN in term of performances indices (IAE, ITAE, ISE and ITSE) and reliability is carried out. The ITSE is used as objective function given in Eq. (31) in optimization process via BKA. The convergence curves for objective function for Lyrebird optimization, Jellyfish search algorithm and Black-winged Kite Algorithm are given in in Fig. 4.

This research considers four cases and five distinct scenarios for IµG to completely assess the controller’s efficacy in diverse conditions. Finally, the robustness and stability analysis are carried out. The simulation results for different scenarios are presented in Tables 2, 3 and 4.

Case-I: step load of 4% to IµG

In this case a step load of 0.04pu is applied to the IµG. The three Lyrebird optimization (LOA), Jellyfish Searching optimization (JSO) and Black-winged Kite Algorithms (BKA) are used for optimization of proposed controller. The proposed controller with BKA optimizer outperformed with minimum ITSE and ISE values of 0.00000499pu and 0.00009638pu respectively. The LOA and JSO have ITSE values 0.004pu and 0.0003pu, and ISE values of 0.000109pu and 0.00013336pu respectively. Figures 5 and 6 show the frequency deviation in islanded microgrid when the ITSE and ISE are used as fitness functions in the optimization process. It is much clear from the Figs. 5 and 6 that there is very less OSH and USH in frequency deviation while using the BKA is an optimizer, clearly dominating the efficacy of the BKA over LOA and JSO. The BKA has reduced the ITSE up to 99.8% from 0.004pu to 0.00000499pu, and 28% reduction in ISE from 0.00013336pu to 0.00009638pu. Thus, the BKA demonstrates its superiority over LOA and JSO.

Case-II: load fluctuations with lack of RESs

-

Scenario-1: Step-up load of 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%.

-

Scenario-2: Severe dynamic load (disturbance at t = 2s, t = 4s, t = 6s and t = 8s).

Scenario-1: Step-up load of 5%, 10%, 15%, 20%.

In this first scenario, the efficacy of proposed controller (I-P) cascade PDN for IµG is evaluated by applying stepping up load of 5%, 10%, 15% and 20% at time t = 2s. The results for different performance parameters are presented in the Table 2, illustrates that the proposed (I-P)-PDN controller performed better than other controllers due to quick response to perturbations with quick settling and no OSH. The lowest OSH and USH values are − 0.00\(\:{\times\:10}^{-5}\) and − 0.011pu at step load 5% and 0.00\(\:{\times\:10}^{-5}\) and − 0.018pu at 10%. The proposed controller’s response settles 0.019s, 0.01, 0.015s and 0.016s faster than other controllers at the four distinct step load. The frequency response of scenario-1 for each step load at t = 2s is given in Fig. 7, (a), (b), (c) and (d).

Scenario-2: Severe Dynamic load at t = 2s, t = 4s, t = 6s and t = 8s

In this scenario a random load with initial stepping at time t = 2s, then 2s delay between consecutive steps of Fig. 8 is applied to islanded microgrid. The first load disturbance (0 to -5% at t = 2s), second disturbance at (-5–10% at t = 4s), third disturbance at (10% to -2.5% at t = 6s) and fourth at (-2.5 to 7.5% at t = 8s). Figure 9, shows the frequency response of each controller against the load disturbances and Table 3. results illustrate that the (I-P)-PDN attains ISE value of 317 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-6}\)pu and Ts of 0.35s for disturbance (-2.5 to 7.5% at t = 8s) and minimal Ts of 0.3s for (-5 to 10% at t = 4s) and the first disturbance (0 to -5% at t = 2s) is settled just in 0.344s.

Case-III: presence of RESs and different loading conditions

-

Scenario-1: Presence of RESs power and absence of load disturbances.

-

Scenario-2: Presence of RESs power and step-up load of 20% at t = 55s.

-

Scenario-3: Presence of RESs and additional step load of 8% at t = 65s.

Scenario-1: Presence of RESs power and absence of load disturbances

In case-III (scenario-1), the islanded microgrid is subjected to load without any change in load or addition of any disturbance. The µG response is simulated for 60 s. From the Table 4 it is reveals that the controller performs well compared to other controllers with lowest performance index ISE of 1.74\(\:{\times\:10}^{-6}\) pu and OSH of 13 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-4}\)pu. The response of the proposed controller is indicated in red color in zoomed view in Fig. 10. It is clear that the controller performed well in reduction in Ts.

Scenario-2: Presence of RESs power and step load of 20% at t = 55s.

This scenario is implemented with application of step load of 20% at time t = 55s for stability analysis of the controller. The Fig. 11, reveals that the controller outperformed with no OSH and quick settling time with high reliability.

Scenario-3: Presence of RESs and additional step load of 8% at t = 65s.

In this scenario, the proposed microgrid with the proposed controller is subjected to step light load of 8% at t = 65s in addition to 10% load (case-II, scenario-1) to analyze the efficacy of controller in term of under frequency. Again, as shown in the Fig. 12, the under frequency has attain the value of -0.0398pu almost same value for individual load of 0.1pu without any variation or change in frequency response.

Case-IV: Variable RESs (PV, Wind) and irregular load.

In this scenario an irregular load81 of 15% is modeled for IµG. The stability and reliability analysis of proposed controller against uncertain RESs and irregular load. It is illustrated from the Fig. 13, that over frequency has value of 1.8\(\:{\times\:10}^{-3}\)pu at t = 2.5s and 1.6\(\:{\times\:10}^{-3}\)pu at t = 5.1s and under frequency with a value of -6\(\:{\times\:10}^{-3}\)pu at t = 10s. The response after 10s is almost linear, it is straightforward that suggested controller performed better irregular nature of load. The performance error indices for interconnected µGs in scenario-1 indicates that our proposed (I-P)-PDN controller perform very well as compared to other controllers.

Performance analysis of the proposed control strategy for two interconnected µGs

In this section, the proposed LFC strategy is tested over 02-areas interconnected µGs network as shown in Fig. 14. The RES wind turbine is dedicated to area-1 and PV source supplies power to area-2. The interconnected microgrid parameters are defined in appendix D.

The simulation of two area interconnected microgrid is carried out with optimized parameters of proposed controller are given in appendix E. \(\:\:\varDelta\:{\text{f}}_{1},\:\:\:\:\varDelta\:{\text{f}}_{2}\)are the frequency responses of area-1 and area-2 and \(\:\Delta{\text{P}}_{\text{t}\text{i}\text{e}}\) is the tie line power. The objective functions ITSE and ISE for the interconnected µGs are given in77. The minimum objective function values are obtained for ITSE of 49.9×\(\:{10}^{-7}\), 96.3×\(\:{10}^{-6}\) for ISE, 53.96\(\:{\times\:10}^{-5}\) for ITAE and 41.36\(\:4\) \(\:{\times\:10}^{-4}\:\)in comparison to its contemporary optimization algorithm, Dandelion Optimizer as reported in the literature.

The interconnected microgrid is tested over four scenarios.

-

Scenario-1: step load of 10% for both areas with lack of RESs and EVs.

-

Scenario-2: step load of 10% for both areas with RESs and lack of EVs.

-

Scenario-3: step load of 10% for both areas in presence of EVs and RESs.

-

Scenario-4: Irregular load of 15% for both areas with intermittent RESs and EVs.

Scenario-1: Step load of 10% for both areas with lack of RESs and EVs.

In the first scenario, a step load of 10% is applied to both areas, in the absence of RESs. As indicated from the Tables 5 and 6, the suggested controller outperformed with (I-P)-PDN controller. The area-1 has frequency response with minimum OSH of 0.0227\(\:{\times\:10}^{-4}\)pu and USH of -1.285\(\:{\times\:10}^{-3}\)pu for ∆f1 and OSH of 0.00917\(\:{\times\:10}^{-4}\)pu and USH of -1.200\(\:{\times\:10}^{-3}\)pu for ∆f2. The two responses in the area-1 and 2 settled faster than other controllers with settling period of 0.75s and 0.98s respectively. Additionally, the tie line power response settled in only 1.189s with minimum ITSE of 0.499\(\:{\times\:10}^{-5}\text{p}\text{u}\). In comparison of two stage controllers, the FPID performed well among all the remaining controllers with settling time of 2.7s and 2.4s for area-1 and area-2 respectively. Among the single stage controllers FPID responses settled faster with 3.7s and 4.3s for area-1 and 2 than other remaining single stage controllers. The frequency and tie-line power responses are given in Fig. 15.

Scenario-2: Step load of 10% for both areas with RESs and lack of EVs.

In second scenario, the intermittent RES wind power is connected to area-1 and PV power to area-2 with step load of 10% for both areas. The Fig. 16a-c, and Table 7, reveals that the suggested controller performed well in compassion to all other controllers with minimum integral weighted square error of 1.60 × 10− 5 pu. The commonly used evaluation criterion ITAE has attain minimum value of 3.88 × 10− 5 pu. The frequency responses have minimum OSH of 4.18 × 10− 4 pu and USH of -4.31 × 10− 6 pu for ∆f1 and OSH of 1.4 × 10− 3 pu, USH of -1.3 × 10− 3pu for ∆f2.

Scenario-3: step load of 10% for both areas in presence of RESs and EVs.

The impact of electric vehicle as flexible load is investigated with proposed controller (I-P)-PDN. In this case a 10% step load at t = 0 s is applied to the area-1 and area-2 in the presence of RESs (PV, WTG). Table 7, and 8, illustrate that the performance indices are improved with the addition of electric vehicles as flexible load. The same electric vehicle model is added to both the area of interconnected microgrid. The performance comparison of the (I-P)-PDN and FPDN-FPTID controllers is carried out with same gains for network microgrid with EVs as flexible load. There is 77% reduction in tie line power OSH (-0.35\(\:{\times\:10}^{-6}\) to -0.804\(\:{\times\:10}^{-7}\)) and 52% USH (-0.85 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-4}\) to -0.4012 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-4}\)) for proposed controller with inclusion of electric vehicles in both areas respectively. The integral weighted absolute error is reduced by 64% (15.5 to 5.49) and 48% (18.5 to 10.3), ITAE by 93% (43.2 to 2.98) and 95% (448 to 20.29), ISE by 98% (1.55 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-5}\) to 3.011 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-7}\)) and 98% (2.2 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-5}\) to 3.019 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-7}\)) and ITSE by 92% (3.88 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-5}\) to 3.69 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-6}\)) and 97% (29.8 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-5}\) to 7.731 \(\:{\times\:10}^{-6}\)) for (I-P)-PDN and FPDN-FPTID controllers respectively. Moreover, the electric vehicles power OSH decreases about 1.94% and USH by 0.05 to 1%. The electric vehicles as source have significance change in power in area-2 for FPDN-FPTID controller. The EVs power ∆PEVs1 and ∆PEVs2 attained faster steady state response with proposed (I-P)-PDN controller as illustrated in Fig. 17a-b. The PV power is slightly changed at almost 10s and 18s from 0.015pu to 0.01213pu and ∆PBESS2 from 0.0425pu to 0.0422pu in area-2 due to loading behavior of EVs. The proposed controller performed well with the incorporation of EVs as flexible load as indicated from Table 8; Fig. 17 (a-b), and Fig. 18.

Scenario-4: Irregular load of 15% for both areas with intermittent RESs and EVs

In this scenario stochastic load of 0.15pu approximately is connected to area-1 and area-2 simultaneously and WTG of 100 kW is dedicated to the area-1 and PV of 30 kW is to area-2. The intermittency of wind (speed= [0 5 10 12 15 14], time= [0 10 15 20 25 30]) to WTG and of solar irradiance (G= [300 500 300 200 350], time= [0 10 15 20 30]) to PV is applied. For inter-relation of intermittency of RESs and availability or non-availability of EVs in area-1 or 2, four conditions have been studied.

Condition-I: Availability of EVs in both areas: In this condition, EVs in both areas are present and connected. At almost 5s both the EVs in area-1 and area-2 comes into contribution of power of 9.064 × 10-6pu and 3.25 × 10-5pu, while PWTG is 0 pu, while Ppv is 0.01234pu at about 6s. The WTG supplies its power of almost 0.003488pu and PV of 0.0158pu, the EVs power at this time becomes 2.6 × 10-6pu and 7.9 × 10-6pu respectively. This power is supplied by RESs at time 10s. At internal 10.58s the EVs1 power cutoff raising PV and WTG power to 0.01707 pu and 0.00248pu respectively. At 10.815s the EVs1, EVs2 cutoff their power and PV power raised to 0.01852pu. At 12.576s, EVs1 power goes up to 6.185 × 10-7pu, and EVs2 of 0.047pu and PV power reaches to 0.02088 pu. At 12.35s again EVs1 = EVs2 = 0.04u and the Ppv of 0.02077pu. At 15.385s, the EVs2 is of 1.5 × 10-8pu and EVs1 is of 0.04pu and the PWTG is 0.0198pu and Ppv of 0.009213pu. The EVs power in both the areas become equal to zero at time nearly equal to 17.5s, at the same time WTG supplies the power of 0.01988pu and PV contribute to 0.01222pu. Similarly, at 18s the EVs in area-1 have power of 1.1 × 10-6pu, but WTG supplies 0.01988pu, thus, the power of EVs in area-1 is decreasing till become zero at 20s and EVs power in area-2 has also goes down to zero. At 22s the PWTG and Ppv is recorded 0.03432pu and 0.00789pu respectively. After this again, at 28s EVs in area-1 going to decrease that is 1.36 × 10-6pu and EVs in area-2 become zero, the PWTG at this time has highest value of 0.06pu and Ppv of 0.0067pu. The minimum power of EVs in area-1 becomes 7.9 × 10-8pu till 30s. The OSH and USH values for ∆f1 are 1.75 × 10-6pu and − 1.40 × 10-3pu, for ∆f2 are 8.5 × 10-5pu, and − 1.7 × 10-2pu, and for ∆Ptie are 1.02 × 10-6pu and − 2.93 × 10-6pu respectively.

Condition-II: Availability of electric vehicles in area-2 only: In this condition, the electric vehicles in area-2 are made available and area-1 have no connectivity of EVs. At time of 10s the WTG power shows connectivity and supplies power of 0.002488pu, as the intermittency of the WTG is taken as (time = [0 10 15 20 25 30], speed= [0 5 10 12 15 14]). Hence, at 5s the EVs in area-2 have power of 1.5e-5pu with PWTG of 0pu. Similarly, the intermittent nature of renewable sources is directly reflected and according to that change, the EVs in the specific area show connectivity or discontinuity due to the intermittency. Similarly, at 15s the solar irradiance has value of 300 W/m2 and wind velocity is 10 m/s, the EVs in area-2 supplies power of 7.2e-8pu, WTG of 0.02pu and PV of 0.008pu. The EVs in specific areas shows the appearance with the intermittency time for RESs in interconnected microgrid system. The EVs in area-2 power starting decreasing and become zero at 30s. The OSH and USH values recorded for ∆f1 are 1.70 × 10-6pu and − 1.402 × 10-3pu, for ∆f2 are 8.509 × 10-5pu and − 1.732 × 10-2pu, and for ∆Ptie are 1.028 × 10-6pu and − 2.393 × 10-6pu respectively.

Condition-III: Availability of EVs in area-1 only: In this condition, the EVs in area-1 are present only such that WTG and PV sources are connected to area-1 and area-2 respectively. Considering the intermittent behavior of WTG and PV power due to weather variability, the PWTG is 0pu because of no wind speed at time 0s, and the Ppv is 0.012pu due to availability of solar irradiance of 300 W/m2. At 10s the WTG deliver power due to wind speed of 5 m/s and at 11s, the PWTG touches 0.002pu, Ppv of 0.0193pu. At 13s the EVs power in area-2 becomes zero per unit, while WTG and PV are delivering power of 0.002pu and 0.0271pu respectively. At 28s the EVs power in area-1 decline to 7.7 × 10-6pu. The OSH and USH values for ∆f1 are 1.74 × 10-6pu and − 1.402 × 10-3pu, for ∆f2 are 8.51 × 10-5pu, and − 1.72 × 10-2pu and for ∆Ptie are 1.028 × 10-6pu and − 2.39 × 10-6pu respectively.

Condition-IV: Non-availability of Electric vehicles in area-1 and area-2: In this condition, the interconnected microgrid is operated without the connectivity of EVs in both the areas. The RESs, WTG and PV deliver power to each respective areas taking the intermittency of solar irradiance Watt/m2 and wind speed. The WTG and PV give full contribution of, 0.05457pu and 0.1475pu respectively. Figure 19a,b and c show the intermittency and uncertainty in the wind turbine power in area-1 due to variation in wind speed (mentioned in spikes at 10s, 15s, 20s and 25s) and photovoltaic power intermittency in area-2 at (0s, 10s, 15s and 20s). The OSH and USH values noted for ∆f1 are 1.73 × 10-6pu and − 1.40 × 10-3pu, for ∆f2 are 8.4 × 10-5pu and − 1.7 × 10-2pu, and for ∆Ptie are 1.02 × 10-6pu and − 2.393 × 10-6pu respectively. From the Fig. 19a-c, the flexible load behavior of EVs in aea-2 is depicted and is photovoltaic power is represented by light green color, in the absence of EVs in area-2 there is slight increase in Photovoltaic power. However, the same power is absorbed by EVs in area-2 depicted by dark blue (photovoltaic power) showing the grid to vehicle (G2V) behavior.

Sensitivity analysis

The controller must demonstrate consistent performance even in the face of uncertain parameters, as the system models it employs are mathematically versatile. Additionally, the system’s configuration and parameters may evolve over time due to factors such as component degradation. Moreover, the system’s configuration and parameters are subjected to alterations over period due to the factors such as component wear and tear, and degradation. The stability of the system may be conceded if the proposed control strategy fails to accommodate system’s parameters variations. To validate the robustness of the proposed controller, parameters such as (R) and system inertia coefficient (M), have been altered by approximately ± 40% relative to their actual parameter responses. The results, which are illustrated in Figs. 20, 21 and 22, and Table 9, demonstrate the controller’s performance under conditions of parametric variation. As seen in Table 9, many parameters exhibit responses that are closely aligned with their nominal values. This data confirms that the BKA-(I-P)-PDN controller delivers consistent performance across a ± 40% of system inertia (M) and (R). Moreover, the controller’s optimal settings remain effective without the need for re-tuning when applied with real parameters at their nominal values.

Stability analysis

From the Bode diagram in Fig. 23, it is illustrated that the proposed controller can endure further increase in gain of 32.1 dB prior to becoming unstable. Moreover, the gain margin has positive value indicating the robustness in stability with respect to variations in gain. The system can endure phase lag of 108 degree prior to crossing instability. Furthermore, the closed loop system is well damped and have good stability with delay margin of 0.446s. There is steady drop in gain as indicated ensuring that the system is stable. The closed loop system stability is obviously marked as “Yes”. The proposed (I-P)-PDN controller exhibits superior gain and phase margins, reflecting stronger robustness and enhanced stability under uncertainties and external disturbances. Unlike conventional methods, the (I-P)-PDN controller maintains higher resilience during large load variations and system parameter changes. These improved stability margins imply that the system can better withstand real-world fluctuations without compromising performance.

Overall, the system has potential to tolerate significant variations in both gains and delay indicate well-tuning, smooth transient responses and can handle the uncertainties in real-world applications.

Conclusion and future recommendations

This study presents a novel two-stage cascaded (I-P)-PDN controller, optimized using the Black-winged Kite Algorithm (BKA), for load frequency regulation in islanded and interconnected microgrid systems. The proposed strategy effectively mitigates frequency deviations caused by the stochastic nature of renewable energy sources (RESs) and dynamic load variations, significantly outperforming conventional controllers. Simulation results demonstrate that the (I-P)-PDN controller achieves a 77% reduction in overshoot (OSH) and a 52% decrease in undershoot (USH) in tie-line power variations compared to existing controllers. Additionally, the Integral Absolute Error (IAE) is reduced by 42.3%, Integral Time Absolute Error (ITAE) by 85%, and Integral Square Error (ISE) by 98%, highlighting the controller’s superior stability and robustness. The impact of Electric Vehicles (EVs) as flexible loads further enhances system performance, leading to a 93% reduction in ITAE and a 95% reduction in ITSE for interconnected microgrids. The stability analysis via Bode plots confirms that the proposed control strategy maintains stability with a gain margin of 32.1 dB and a phase margin of 108 degrees, ensuring resilience against uncertainties. Generally, the (I-P)-PDN controller with BKA tuning provides a reliable solution for microgrid frequency regulation with the limitation of moderate computational demand during the offline tuning stage when scaling to high dimension search space. However, this demand remains manageable with standard computing resources and does not hinder practical applicability. Future work can explore real-time hardware implementation and cybersecurity aspects of microgrid communication delays to further enhance the practicality of the proposed control strategy. Furthermore, addressing cybersecurity concerns, as microgrids are increasingly reliant on communication networks for monitoring and control, making them vulnerable to cyber-attacks such as data spoofing, denial of service, and false data injection.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Abbreviations

- ARES:

-

Alternative renewable energy sources

- IRENA:

-

International renewable energy agency

- LFC:

-

Load frequency control

- EVs:

-

Electric vehicles

- EVs1:

-

Electric vehicles in area-1

- EVs2:

-

Electric vehicles in area-2

- DEGs:

-

Disease engine generators

- BKA:

-

Black-winged kite algorithm

- GA:

-

Genetic algorithm

- (I-P):

-

Integral-proportional

- PID:

-

Proportional-integral-derivative

- WTs:

-

Wind turbines

- IAE:

-

Integral absolute error

- DE:

-

Deferential evolution

- ESSs:

-

Energy storage systems

- BESSs:

-

Battery energy storage systems

- ΔPBESS:

-

Change in power of battery energy storage sources

- ΔPWT:

-

Change in power of wind turbine

- ΔPEVs:

-

Change in power of electric vehicles

- ΔPEVs1:

-

Variation in power of electric vehicles in the area-1

- ΔPEVs2:

-

Change in power of electric vehicles in the area-2

- ΔPPV:

-

Variation in photovoltaic power

- ΔPFC:

-

Change in fuel cell power

- ΔPs:

-

Change in power of different sources

- ΔF:

-

Change in frequency

- FPDN:

-

Fractional order proportional derivative with filter coefficient N

- FPID:

-

Fractional order PID

- FPTID:

-

Fractional-order proportional-tilted-integral-derivative

- FCs:

-

Fuel cells

- AGC:

-

Automatic generation control

- ISE:

-

Integral square error

- ITAE:

-

Integral time weighted absolute error

- ITSE:

-

Integral time weighted square error

- NISE:

-

Novel integral weighted square error

- IµGs:

-

Islanded Microgrids

- µGs:

-

Microgrids

- V2G:

-

Vehicle to Grid

- OS:

-

Overshoot

- US:

-

Undershoot

- PV:

-

Photovoltaics

- PDN:

-

Proportional derivative with N filter

- DC:

-

Direct current

- AC:

-

Alternating current

- DD:

-

Double derivatives

- IDD:

-

Integral double derivative

- VIC:

-

Virtual inertia control

- STA:

-

Self-tuned algorithm

- SBO:

-

Satin bowerbird optimizer

- ΔU:

-

Control signal of controller

- D:

-

Load-damping coefficient

- M:

-

Overall system inertia constant

- ARO:

-

Artificial rabbit optimizer algorithm

- P0:

-

Output power

- ΔPL:

-

Change in load

References

Faheem, M., Kuusniemi, H., Eltahawy, B., Bhutta, M. S. & Raza, B. A lightweight smart contracts framework for blockchain-based secure communication in smart grid applications. IET Generation Transmission Distribution. 18 (3), 625–638 (2024).

Zeynali, S., Rostami, N. & Feyzi, M. Multi-objective optimal short-term planning of renewable distributed generations and capacitor banks in power system considering different uncertainties including plug-in electric vehicles. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 119, 105885 (2020).

Blaabjerg, F., Yang, Y., Kim, K. A. & Rodriguez, J. Power electronics technology for large-scale renewable energy generation, Proceedings of the IEEE,111, 4, 335–355, (2023).

Zografos, D. & Ghandhari, M. Power system inertia estimation by approaching load power change after a disturbance, in IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting, 2017.

Renewables, I. Analysis and Forecast to 2027. 2023, ed, (2022).

Farsizadeh, H., Gheisarnejad, M., Mosayebi, M., Rafiei, M. & Khooban, M. H. An intelligent and fast controller for DC/DC converter feeding CPL in a DC microgrid. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs. 67 (6), 1104–1108 (2019).

Kang, W. et al. Distributed secondary control method for islanded microgrids with communication constraints. IEEE Access. 6, 5812–5821 (2017).

Olabi, A. & Abdelkareem, M. A. Renewable energy and climate change. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 158, 112111 (2022).

Bakeer, A., Magdy, G., Chub, A. & Bevrani, H. A sophisticated modeling approach for photovoltaic systems in load frequency control. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 134, 107330 (2022).

Qin, B., Wang, M., Zhang, G. & Zhang, Z. Impact of renewable energy penetration rate on power system frequency stability. Energy Rep. 8, 997–1003 (2022).

Nazir, M. S. et al. Optimized economic operation of energy storage integration using improved gravitational search algorithm and dual stage optimization. J. Energy Storage. 50, 104591 (2022).

Zand, M., Nasab, M. A., Padmanaban, S., Maroti, P. K. & Muyeen, S. Sensitivity analysis index to determine the optimal location of multi-objective UPFC for improvement of power quality parameters. Energy Rep. 10, 431–438 (2023).

Nasab, M. A. et al. Uncertainty compensation with coordinated control of EVs and DER systems in smart grids. Sol. Energy. 263, 111920 (2023).

Hosseini, S. A. Frequency control using electric vehicles with adaptive latency compensation and variable speed wind turbines using modified virtual inertia controller. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 155, 109535 (2024).

Tripathi, S., Singh, V. P., Kishor, N. & Pandey, A. Load frequency control of power system considering electric vehicles’ aggregator with communication delay. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 145, 108697 (2023).

Liang, J. et al. An energy-oriented torque-vector control framework for distributed drive electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification. 9 (3), 4014–4031 (2023).

Smith, C. et al. Comparative life cycle assessment of a Thai island’s diesel/pv/wind hybrid microgrid. Renew. Energy. 80, 85–100 (2015).

Fathollahi, A., Kargar, A. & Derakhshandeh, S. Y. Enhancement of power system transient stability and voltage regulation performance with decentralized synergetic TCSC controller. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 135, 107533 (2022).

Abubakr, H. et al. Adaptive LFC incorporating modified virtual rotor to regulate frequency and tie-line power flow in multi-area microgrids. IEEE Access. 10, 33248–33268 (2022).

d., P. I., Barbalho, N., Lacerda, V., Fernandes, R. & Coury, D. V. Deep reinforcement learning-based secondary control for microgrids in islanded mode. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 212, 108315 (2022).

Oshnoei, S., Aghamohammadi, M., Oshnoei, S., Oshnoei, A. & Mohammadi-Ivatloo, B. Provision of frequency stability of an islanded microgrid using a novel virtual inertia control and a fractional order cascade controller, Energies, 14,14, 4152, (2021).

Oshnoei, S., Oshnoei, A., Mosallanejad, A. & Haghjoo, F. Contribution of GCSC to regulate the frequency in multi-area power systems considering time delays: A new control outline based on fractional order controllers. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 123, 106197 (2020).

Ali, E. S. & Abd-Elazim, S. M. Bacteria foraging optimization algorithm based load frequency controller for interconnected power system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 33 (3), 633–638 (2011).

Hasan, N., Alsaidan, I., Sajid, M., Khatoon, S. & Farooq, S. Robust self tuned AGC controller for wind energy penetrated power system. Ain Shams Eng. J. 13 (4), 101663 (2022).

Gbadega, P. A. & Sun, Y. Multi-area automatic generation control of a renewable energy-based hybrid power systems using JAYA optimized model predictive control. Energy Rep. 9, 74–84 (2023).

Gbadega, P. A., Sun, Y. & Zhang, H. Robustness and stability analysis for parametric uncertainties in a three-area AGC power system using TLBO-LMI-tuned PI controller. Energy Rep. 9, 153–164 (2023).

Sahu, P. C., Prusty, R. C. & Panda, S. Optimal design of a robust FO-Multistage controller for the frequency awareness of an islanded AC microgrid under i-SCA algorithm. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 43 (1), 2681–2693 (2022).

Khokhar, B., Dahiya, S. & Singh Parmar, K. A robust cascade controller for load frequency control of a standalone microgrid incorporating electric vehicles. Electr. Power Compon. Syst. 48, 6–7 (2020).

Alhejji, A., Ahmed, N., Ebeed, M., Sayed, K. & Refai, A. A robust cascaded controller for load frequency control in renewable energy integrated microgrid containing PEV. Int. J. Renew. Energy Res. (IJRER). 13 (1), 423–433 (2023).

Mishra, D., Sahu, P. C., Prusty, R. C. & Panda, S. A fuzzy adaptive fractional order-PID controller for frequency control of an islanded microgrid under stochastic wind/solar uncertainties. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 43 (1), 4602–4611 (2022).

Arya, Y. AGC of PV-thermal and hydro-thermal power systems using CES and a new multi-stage FPIDF-(1 + PI) controller. Renew. Energy. 134, 796–806 (2019).

Sahu, P. C. & Samantaray, S. R. Resilient frequency stability of a pv/wind penetrated complex power system with CSA tuned robust Type-2 fuzzy cascade PIF controller. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 225, 109815 (2023).

Bhatta, S. K., Mohapatra, S., Sahu, P. C., Swain, S. C. & Panda, S. Novel QO-PFA governed FO-type-II fuzzy controller for LFC of thermo-electric generator based hybrid power system, e-Prime-Adv. Electrical Eng., Electronics and Energy, 5, 100249, (2023).

Routray, S. K., Choudhury, S., Sahu, P. C. & Mohapatra, S. A review analysis on various approaches for LFC of multi area power system: Robust t2 fuzzy controller, in 2023 International Conference in Advances in Power, Signal, and Information Technology (APSIT), IEEE, 1–5. (2023).

Sahu, P. C. Modelling of an EV based AC microgrid for frequency profile improvement by M-CSA designed Fuzzy-T2-PSS controller. Progress Eng. Sci., 100057, (2025).

Elkasem, A. H., Khamies, M., Hassan, M. H., Agwa, A. M. & Kamel, S. Optimal design of TD-TI controller for LFC considering renewables penetration by an improved chaos game optimizer. Fractal Fract. 6 (4), 220 (2022).

Saikia, L. C. & Sinha, N. Automatic generation control of a multi-area system using ant Lion optimizer algorithm based PID plus second order derivative controller. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 80, 52–63 (2016).

Chinta, D. P., Jatoth, R. K. & Biswal, M. Power system frequency profile improvement using satin Bowerbird optimized Tilt fractional cascade controller with reduced data based cost function. J. Eng. Res. 11 (4), 414–424 (2023).

Bakeer, M., Magdy, G., Bakeer, A. & Aly, M. M. Resilient virtual synchronous generator approach using DC-link capacitor energy for frequency support of interconnected renewable power systems. J. Energy Storage. 65, 107230 (2023).

Choudhary, R., Rai, J. & Arya, Y. FOPTID + 1 controller with capacitive energy storage for AGC performance enrichment of multi-source electric power systems. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 221, 109450 (2023).

Jagatheesan, K., Anand, B., Dey, N., Ashour, A. S. & Balas, V. E. Load frequency control of multi-area interconnected thermal power system: artificial intelligence-based approach. Int. J. Autom. Control. 12 (1), 126–152 (2018).

Gbadega, P. A. & Saha, A. K. Load frequency control of a two-area power system with a stand-alone microgrid based on adaptive model predictive control. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 9 (6), 7253–7263 (2020).

Lv, X., Sun, Y., Wang, Y. & Dinavahi, V. Adaptive event-triggered load frequency control of multi-area power systems under networked environment via sliding mode control. IEEE Access. 8, 86585–86594 (2020).

Eltamaly, A. M., Zaki Diab, A. A. & Abo-Khalil, A. G. Robust control based on H ∞ and linear quadratic Gaussian of load frequency control of power systems integrated with wind energy system. Control Operation grid-connected Wind Energy Systems, 73–86, (2021).

Bu, X., Yu, W., Cui, L., Hou, Z. & Chen, Z. Event-triggered data-driven load frequency control for multiarea power systems. IEEE Trans. Industr. Inf. 18 (9), 5982–5991 (2021).

Yakout, A. H., Kotb, H., Hasanien, H. M. & Aboras, K. M. Optimal fuzzy PIDF load frequency controller for hybrid microgrid system using marine predator algorithm. IEEE Access. 9, 54220–54232 (2021).

Abouzeid, S. I. et al. Load frequency control based on reinforcement learning for microgrids under false data attacks. Comput. Electr. Eng. 123, 110093 (2025).

Danaeefar, H., Barati, H. & Shirmardi, S. A. Optimal Control of PID-FUZZY Based on Gravitational Search Algorithm for Load Frequency Control Ed (IJERT, 2019).

Sahu, P. C. Impact and integration of electric vehicles on renewable energy based microgrid: frequency profile improvement by a-SCA optimized FO-Fuzzy PSS approach. Green. Energy Intell. Transp. 4 (2), 100191 (2025).

Yang, C., Zhao, Y., Li, X. & Zhou, X. Electric vehicles, load response, and renewable energy synergy: A new stochastic model for innovation strategies in green energy systems. Renew. Energy. 238, 121890 (2025).

Gbadega, P. A. & Sun, Y. Multi-area load frequency regulation of a stochastic renewable energy-based power system with SMES using enhanced-WOA-tuned PID controller, Heliyon, 9, 9, (2023).

Ahmed, N. M. et al. A new optimized FOPIDA-FOIDN controller for the frequency regulation of hybrid Multi-Area interconnected microgrids. Fractal Fract. 7 (9), 666 (2023).

Mohamed, E. A. et al. An optimized hybrid fractional order controller for frequency regulation in multi-area power systems. IEEE Access. 8, 213899–213915 (2020).

Ahmed, E. M., Mohamed, E. A., Elmelegi, A., Aly, M. & Elbaksawi, O. Optimum modified fractional order controller for future electric vehicles and renewable energy-based interconnected power systems. IEEE Access. 9, 29993–30010 (2021).

Arya, Y. A novel CFFOPI-FOPID controller for AGC performance enhancement of single and multi-area electric power systems. ISA Trans. 100, 126–135 (2020).

Zaid, S. A. et al. A new intelligent fractional-order load frequency control for interconnected modern power systems with virtual inertia control. Fractal Fract. 7 (1), 62 (2023).

Almasoudi, F. M., Magdy, G., Bakeer, A., Alatawi, K. S. S. & Rihan, M. A new load frequency control technique for hybrid maritime microgrids: sophisticated structure of fractional-order PIDA controller. Fractal Fract. 7 (6), 435 (2023).

Almasoudi, F. M. et al. Nonlinear coordination strategy between renewable energy sources and fuel cells for frequency regulation of hybrid power systems. Ain Shams Eng. J. 15 (2), 102399 (2024).

Khalil, A. E., Boghdady, T. A., Alham, M. & Ibrahim, D. K. Enhancing the conventional controllers for load frequency control of isolated microgrids using proposed multi-objective formulation via artificial rabbits optimization algorithm. IEEE Access. 11, 3472–3493 (2023).

Ojha, S. K. & Maddela, C. O. A FOPIDN-(1 + PIDN) controller design and optimization for load frequency control system integrated with renewables and electric vehicles. Electrical Engineering, 1–27, (2025).

Jena, N. K. et al. Impact of a redox flow battery on the frequency stability of a five-area system integrated with renewable sources, Energies, 16, 14, 5540, (2023).

Singh, B., Slowik, A. & Bishnoi, S. K. A Dual-stage controller for frequency regulation in a two-area realistic diverse hybrid power system using bull–lion optimization, Energies 15, 21, 8063, (2022).

Barakat, M. Novel chaos game optimization tuned-fractional-order PID fractional-order PI controller for load-frequency control of interconnected power systems. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 7 (2), 1–20 (2022).

Mishra, S., Nayak, P. C., Prusty, R. C. & Panda, S. Modified multiverse optimizer technique-based two degree of freedom fuzzy PID controller for frequency control of microgrid systems with hydrogen aqua electrolyzer fuel cell unit. Neural Comput. Appl. 34 (21), 18805–18821 (2022).

Kreishan, M. Z. & Zobaa, A. F. Mixed-integer distributed ant colony optimization of dump load allocation with improved islanded microgrid load flow, Energies, 16 1, 213, (2022).

Wang, J., Wang, W., Hu, X., Qiu, L. & Zang, H. Black-winged kite algorithm: a nature-inspired meta-heuristic for solving benchmark functions and engineering problems. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57 (4), 98 (2024).

Abazari, A., Monsef, H. & Wu, B. Coordination strategies of distributed energy resources including FESS, DEG, FC and WTG in load frequency control (LFC) scheme of hybrid isolated micro-grid. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 109, 535–547 (2019).

Chen, Q., Wang, L., Sun, Y., Xie, S. & Wang, R. Adaptive integral sliding mode MPPT control for wind turbines with fixed-time convergence. IET Renew. Power Generation, (2024).

Ahmed, M., Magdy, G., Khamies, M. & Kamel, S. Modified TID controller for load frequency control of a two-area interconnected diverse-unit power system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 135, 107528 (2022).

Prusty, U. C., Nayak, P. C., Prusty, R. C. & Panda, S. An improved moth swarm algorithm based fractional order type-2 fuzzy PID controller for frequency regulation of microgrid system. Energy Sources Part. A: Recovery Utilization Environ. Effects, 1–23, (2022).

Fauzi, F., Yasin, N., Leong, J. & Ismail, B. Design of 30 kW three-phase string inverter using simulink, in J. Phys. Conference Series 1432 1 IOP Publishing, 012029. (2020).

Davoudkhani, I. F., Zare, P., Abdelaziz, A. Y., Bajaj, M. & Tuka, M. B. Robust load-frequency control of islanded urban microgrid using 1PD-3DOF-PID controller including mobile EV energy storage. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 13962 (2024).

Patil, R. S., Jadhav, S. P. & Patil, M. D. Review of intelligent and Nature-Inspired Algorithms-Based methods for tuning PID controllers in industrial applications. J. Rob. Control (JRC). 5 (2), 336–358 (2024).

Ali, T. et al. Load frequency control and automatic voltage regulation in four-area interconnected power systems using a gradient-based optimizer, Energies, 16, 5 ,2023. (2086).

Ekinci, S., Izci, D., Can, Ö., Bajaj, M. & Blazek, V. Frequency regulation of PV-reheat thermal power system via a novel hybrid educational competition optimizer with pattern search and cascaded PDN-PI controller. Res. Eng. 102958, (2024).

Irfan, M., Deilami, S., Huang, S., Tahir, T. & Veettil, B. P. Optimizing load frequency control in microgrid with vehicle-to-grid integration in australia: based on an enhanced control approach. Appl. Energy. 366, 123317 (2024).

Ahmed, E. M. et al. Improving load frequency control performance in interconnected power systems with a new optimal high degree of freedom cascaded FOTPID-TIDF controller. Ain Shams Eng. J. 14 (10), 102207 (2023).

Shafei, M. A. R., Ibrahim, D. K. & Bahaa, M. Application of PSO tuned fuzzy logic controller for LFC of two-area power system with redox flow battery and PV solar park. Ain Shams Eng. J. 13 (5), 101710 (2022).

Wu, C. F., Lai, J. H., Chen, S. H. & Trac, L. V. T. Key factors promoting the niche establishment of black-winged kite Elanus caeruleus in farmland ecosystems. Ecol. Ind. 149, 110162 (2023).

Jiang, M., Feng, X., Wang, C. & Zhang, H. Robust color image watermarking algorithm based on synchronization correction with multi-layer perceptron and cauchy distribution model. Appl. Soft Comput. 140, 110271 (2023).

Magdy, G., Shabib, G., Elbaset, A. A. & Mitani, Y. Renewable power systems dynamic security using a new coordination of frequency control strategy based on virtual synchronous generator and digital frequency protection. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 109, 351–368 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The author is thankful to NGCPL/formerly National Transmission and Despatch Company (NTDC) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Imran Khan (I.K): Conceptualization, Methodology, Paper Writing and original draft. Amil Daraz (A.D): data correction, review and editing. Suheel Abdullah Malik (S.A.M): Supervision, Resources, Reviewing and Editing. Baitullah Bareer (B.B): Methodology, Software, Review and Editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, I., Malik, S.A., Daraz, A. et al. Enhanced load frequency regulation in microgrids with renewable energy sources and electric vehicles. Sci Rep 15, 26634 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10835-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10835-z