Abstract

Drought and heat are major co-occurring stresses that sharply reduce crop yield. This study investigated antioxidant and hormonal responses in 36 barley genotypes (5 cultivated, 31 wild) under two planting dates and two irrigation regimes over two years. Evaluated traits included phenolic compounds, antioxidant enzymes, oxidative markers, DPPH activity, grain yield, and levels of ABA, IAA, and gibberellin. Under normal conditions, cultivated genotypes yielded 71% more than wild genotypes; however, this advantage declined to 12% under combined drought and heat stress. Under this extreme stress, yield reduction averaged 57% in wild genotypes and 72% in cultivated ones. Wild genotypes exhibited stronger antioxidant responses, marked by greater increases in guaiacol peroxidase, total phenolic content, total flavonoid content, and DPPH activity. Under drought and combined heat and drought stress, ABA increased significantly more in wild genotypes (>90%) than cultivated ones (>20%). In contrast, heat stress alone had no significant effect on ABA levels in either genotype. IAA and gibberellin showed a similar pattern, but with a declining trend. Ellagic acid, syringic acid, and rutin were the dominant phenolics contributing to stress tolerance. These results highlight wild barley’s superior stress adaptation through antioxidant and hormonal responses, offering valuable genes for improving cultivated barley.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The loss of plant yield due to the adverse effects of drought and heat stress underscores the urgent imperative to mitigate these losses, making it a central priority for ensuring food security amidst global climate change. In a global warming scenario, heat and drought stress emerges as the most significant abiotic stresses, highlighting the need for drought and thermo-tolerant genotypes capable of maintaining product attributes within agricultural systems1. A wide range of molecular and physiological processes, such as photosynthesis, respiration, translocation, synthesis of stress-related proteins and metabolites, nutrient, carbohydrate metabolism, and hormonal regulation are disrupted by water deficit and heat stress, as demonstrated in a recent study2. Under heat conditions, drought severity increases due to enhanced soil moisture evaporation and elevated plant water consumption1. Conversely, under drought stress, reduced transpiration rates elevate leaf surface temperature, intensifying the combined impact of both stresses compared to their individual effects3,4. Developing crop cultivars with improved tolerance to interconnected stresses of drought and heat is crucial, necessitating a thorough understanding of plant responses to these combined challenges2,4. Drought conditions decrease water availability, leading to turgor loss, inhibited photosynthesis, and impaired long-distance transport, while severe drought causes cellular dehydration, destabilizing membranes, and proteins, ultimately resulting in irreversible cell damage and death5. The response of plants to water scarcity entails a sequence of events that initiate adaptive changes in plant growth, physiological, and biochemical processes. Plants’ strategies to combat drought stress can be classified into avoidance, escape, and tolerance5. These adaptations involve modifications in plant structure, growth rates, tissue osmotic potential, and the enhancement of antioxidant defense mechanisms2.

Heat stress disrupts membrane systems and biochemical pathways, leading to membrane protein dysfunction and metabolic imbalances due to protein denaturation, which can become toxic to the cells; increased transpiration primarily aids in heat stress avoidance6. For short-term survival under severe heat stress, the accumulation of heat shock proteins (HSPs) along with protection of the photosynthetic apparatus and removal of reactive oxygen species (ROS) constitute plant tolerance responses, while metabolic alterations ensure cell protection during long-term stress5.

The time of planting in winter-sown cereals, such as barley, is crucial for effective crop management, particularly in regions confronting environmental challenges, such as high temperatures during the terminal growth stages, typically in spring7. The grain yield of a cereal plant is adversely correlated with the duration of its growth period coinciding with heat stress, especially during one of the most sensitive growth stages like the reproductive stage7. The plant’s dehydration avoidance strategy, exemplified by stomatal closure, aims to reduce water loss from the leaves. However, this response also generates ROS, limits CO2 uptake, damages photosystem II (PSII), and inhibits photosynthesis, ultimately resulting in yield loss2. Drought escape refers to the capability of plants to expedite flowering and complete their life cycle. Early planting could also assist plants in achieving their life cycle before the onset of heat8. The tolerance mechanism involves the activation of ROS scavenging pathways, enhanced compatible solute biosynthesis, and the accumulation of protective molecules2.

Genetic erosion stands as one of the foremost challenges confronting plant breeders globally, highlighting the urgent need to effectively utilize genetic resources to improve plant adaptation to changing environments and strengthen food production6. Wild barley (H. vulgare ssp. spontaneum L.), herein referred to H. spontaneum, serves as an immediate progenitor of cultivated barley (H. vulgare ssp. vulgare L.), and is considered as its subspecies due to their high genome homology and homologous chromosomes, which engage in a complete chromosome pairing during meiosis. This wild species is often valued for its drought and heat-tolerant genes 9,10. Hence, introgression of the wild genome into barley is intriguing for enhancing barley’s genetic resilience to drought and heat, as well as for exploring tolerance mechanisms.

Although numerous studies have examined barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) responses to abiotic stresses, most have been limited to single stress conditions such as drought 11,12 or heat7,13 often comparing stressed plants to controls or focusing solely on warm environments14. Regarding antioxidant responses, prior research has typically concentrated on the effects of drought stress on phenolic compounds and antioxidant enzyme activity in barley under controlled environments15 including growth chambers16 and greenhouses17. These settings, however, do not accurately reflect the complexity and variability of field conditions. Notably, comprehensive evaluations of the full antioxidant defense system—both enzymatic and non-enzymatic—under field-based heat and drought stress, particularly involving diverse H. vulgare germplasm across cultivated and wild subspecies (H. vulgare subsp. spontaneum), remain largely unexplored. Furthermore, in natural agroecosystems, plants are frequently exposed to simultaneous drought and heat stress—a scenario that is increasingly prevalent due to climate change, as emphasized by Sato et al.5 and Vaezi et al.4.

Given that the antioxidant system, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, and key enzymes (e.g., CAT, APX, POX), is a shared mechanism of tolerance for both drought and heat, our study was designed to fill this critical gap. We aimed to systematically investigate the biochemical and hormonal responses (ABA, IAA, GB) of 36 diverse barley genotypes (31 wild and 5 cultivated) under four distinct field conditions: (1) normal, (2) water deficit, (3) delayed planting to induce terminal heat stress, and (4) a combination of drought and heat stress. By simultaneously comparing cultivated and wild genotypes, this work not only provides insights into the differential stress adaptation mechanisms across barley subspecies but also presents a rare field-based study that integrates phenolic profiling, antioxidant activity, hormonal dynamics, and yield-related traits under complex environmental stressors. This contributes significantly to our understanding of barley resilience and offers practical implications for climate-resilient breeding strategies.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

In this study, 36 barley genotypes were used, comprising 31 Hordeum spontaneum genotypes originating from western Iran (specifically, the five provinces of Lorestan, West Azarbaijan, Ilam, Kordestan, and Kermanshah) and five barley cultivars: Mona, Reyhan, Goharan, Yosef, and Fajr30. The geographical origin attributes of the studied genotypes are detailed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Based on grain yield and yield loss criteria, two genotypes (a wild genotype (G28) and a cultivated genotype (G34, ‘Mona’)) were selected for biochemical analysis.

Application of heat stress

To simulate heat stress, two planting dates were used in each growing season. In the first season, sowing was performed on 13 November 2021 (normal) and 1 February 2022 (late); in the second season, on 11 November 2022 (normal) and 2 February 2023 (late). The late sowing exposed plants to higher ambient temperatures during the reproductive stage, particularly during grain filling, which is known to be sensitive to heat. This approach effectively mimicked terminal heat stress (Table S3) under field conditions without using artificial heating systems.

Application of water deficit

Drought stress was imposed using a regulated irrigation strategy based on the maximum allowable depletion (MAD) of soil available water (SAW), as described by Kermani et al.18. Two irrigation regimes were established:

IR1 (Control): Irrigation at 40% depletion of SAW (moderate depletion).

IR2 (Drought Stress): Irrigation at 80% depletion of SAW (severe depletion).

To monitor soil moisture, gravimetric water content was measured by collecting soil samples at three depths (0–20, 20–40, and 40–60 cm) every two days between irrigations. The irrigation schedule was determined based on actual evapotranspiration and moisture loss from the soil.

Drought treatment began at the flowering stage after a uniform irrigation to all plots. Subsequent irrigation was applied when the MAD threshold, calculated using the following formula, was reached:

where θirrig (%) is the MAD threshold value for each treatment, θfc and θpwpare the soil water contents at field capacity (%) and wilting point (%), respectively and ρ is the fraction of SAW (40, and 80%) that can be depleted from the root zone. The depth and the volume of irrigation was estimated based on the soil water content by the following Eq18.:

Where Dirrig (cm) is the depth of irrigation, θfc is the soil water content at field capacity (%) and θavg is the available water content in root zone, Ze is the root depth, ρb is the soil bulk density, Virrig is the volume of irrigation and Afield is the cultivated area. Then, the amount of irrigation water applied to the field was measured by a flow meter.

Experimental design

As a result, the genotypes were evaluated in four environmental conditions including normal irrigation and planting date (N), water stress at normal planting date (WS), normal irrigation with delayed planting, leading to terminal heat stress (HS), and water stress at delayed planting resulting in combined water and heat stress (WS-HS). These environmental conditions are hereafter referred to as normal (N), water stress (WS), heat stress (HS) and combined water and heat stress (WS-HS). A 6 × 6 lattice-square design with two replications was employed for genotype evaluation in each of four experimental conditions within each growing season. Each experimental unit comprised two planting rows with a row spacing of 30 cm and a row length of 150 cm. All plants were subjected to uniform agronomic practices, including irrigation, until the early jointing plant stage, when the water-deficit treatment was initiated.

Antioxidant defense parameters

Enzymatic antioxidants

Protein extraction and quantification

To measure total protein content of the leaves, proteins were extracted from plant tissues at 0–4 °C on ice. For this purpose, one g of frozen plant tissue was ground in a chilled mortar with 3 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) containing 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, and 1% PVP. The resulting extract was centrifuged at 4000 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was used for protein quantification. Aliquots of each extract were stored in microtubes at − 80 °C until analysis. Protein content was determined using the Bradford method19. Briefly, 0.1 mL of protein extract was added to 5 mL of Bradford reagent, vortexed immediately, and the absorbance was measured at 595 nm after 2 min and within one hour using a spectrophotometer. Protein concentration was calculated based on a standard curve generated with bovine serum albumin (BSA) at different concentrations. The Bradford reagent was prepared by dissolving 0.1 g of Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 in 50 mL of 95% ethanol for one hour. Then, 100 mL of 85% phosphoric acid was added dropwise. Finally, the volume was adjusted to one liter with distilled water, the solution was filtered through Whatman No.1 filter paper, and stored in a refrigerator until use.

Enzyme extraction

Fresh leaf samples (0.2 g per treatment) were homogenized using a mortar and pestle to prepare the soluble extract for enzyme activity assays. Subsequently, 2 mL of sodium phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0) containing 50 mM potassium phosphate, one mM EDTA, 2% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), 2 mM α-dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 mM Tris-HCl, and 0.2% Triton X-100 was added to each sample. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 min, and the resulting supernatant was collected for the analysis of antioxidant enzyme activities. Each enzyme assay was performed in two replicates.

Calculation of enzyme activities and normalization based on protein content

To evaluate enzyme activity in a biologically meaningful way, it is important to report not only the absolute activity but also normalize it to the protein content of the sample. This is because young tissues—rich in meristematic cells—contain more soluble proteins and enzyme content than mature tissues, which often have more structural components such as lignin and insoluble proteins20. Therefore, the specific enzyme activity was calculated by dividing the volumetric enzyme activity by the protein concentration in the extract (U/mg protein)18.

The enzyme activity was calculated using the following formula:

Enzyme Activity (U) = \(\:\frac{{\Delta}A \times TV\times D}{{\epsilon\times EV}}\)

Volumetric Activity (U/mL) = \(\:\frac{\text{E}\text{n}\text{z}\text{y}\text{m}\text{e}\:\text{A}\text{c}\text{t}\text{i}\text{v}\text{i}\text{t}\text{y}\:\left(\text{U}\right)}{\text{V}\text{o}\text{l}\text{u}\text{m}\text{e}\:\text{o}\text{f}\:\text{e}\text{x}\text{t}\text{r}\text{a}\text{c}\text{t}\:\text{u}\text{s}\text{e}\text{d}\:\left(\text{m}\text{L}\right)\text{}}\)

Specific Activity (U/mg protein) = \(\:\frac{\text{V}\text{o}\text{l}\text{u}\text{m}\text{e}\text{t}\text{r}\text{i}\text{c}\:\text{A}\text{c}\text{t}\text{i}\text{v}\text{i}\text{t}\text{y}\:(\text{U}/\text{m}\text{L})\text{}}{\text{P}\text{r}\text{o}\text{t}\text{e}\text{i}\text{n}\:\text{c}\text{o}\text{n}\text{c}\text{e}\text{n}\text{t}\text{r}\text{a}\text{t}\text{i}\text{o}\text{n}\:(\text{m}\text{g}/\text{m}\text{L})}\)

∆A: Change in absorbance per minute at specific wave length (nm).

TV: Total volume of the reaction mixture (mL).

D: Dilution factor.

ε: Extinction coefficient for each enzyme.

EV: Volume of enzyme extract used (mL).

For example: one unit (U) of catalase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that decomposes one µmol of hydrogen peroxide per minute at 25 °C under assay conditions.

Guaiacol peroxidase activity

The activity of guaiacol peroxidase (POX) was assessed using a protocol described by Hemeda and Klein21. The reaction mixture consisted of 30 µL of enzyme extract, 2.77 mL of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 100 µL of 1% hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and 100 µL of 4% guaiacol. The enzymatic reaction was initiated by adding H₂O₂, and the oxidation of guaiacol, resulting in the formation of tetraguaiacol, was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 470 nm after one minute. The extinction coefficient of tetraguaiacol (25.5 mM⁻¹·cm⁻¹) was used to calculate enzyme activity. The results were expressed as enzyme activity units per milligram of protein.

Ascorbate peroxidase activity

Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity was measured according to the method of Nakano and Asada22. The reaction mixture contained 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.1 mM hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, and 150 µL of enzyme extract. The oxidation of ascorbic acid was monitored by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 290 nm. APX activity was calculated using an extinction coefficient (ε) of 2.8 mM⁻¹·cm⁻¹. One unit (U) of APX activity is defined as the amount of enzyme required to oxidize 1 µmol of ascorbate per minute. Enzyme activity was expressed as units per milligram of protein.

Catalase activity

Catalase (CAT) activity was determined according to the method of Aebi23. The mixture comprised 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 15 mM hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), and 100 µL of enzyme extract. The decomposition of H₂O₂ was monitored by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 240 nm using a spectrophotometer at 30-second intervals for up to 2 min. CAT activity was calculated using an extinction coefficient (ε) of 40 mM⁻¹·cm⁻¹. One unit (U) of catalase activity was defined as the amount of enzyme required to decompose 1 µmol of H₂O₂ per minute. Enzyme activity was expressed as units per milligram of protein, equivalent to 1 µmol of H₂O₂ decomposed per minute per milligram of protein.

Non-enzymatic antioxidants

Total phenolic content

The total phenolic content (TPC) was quantified using the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, following the method described by Kiani et al.24. To extract methanolic content from barely genotypes, 100 mg of powdered plants underwent extraction with 10 mL of 80% methanol, gently shaken (150 rpm) at 25◦C for 24 h. After filtration, 2.5 mL of diluted Foline-Ciocalteu’s reagent (1:10 dilution with distilled water) and 2 mL of 7.5% sodium carbonate solution were added to 0.5 mL of the methanolic extract. The mixture was incubated at 45 °C for 15 min. Subsequently, the absorbance was measured at 765 nm using a spectrophotometer. Tannic acid served as a standard for quantifying total phenols. The TPC was expressed as milligrams of tannic acid equivalent (TAE) per gram of each extract on a dry weight basis.

Total flavonoid content

The aluminum chloride colorimetric method, as described by Kiani et al.24 was employed to assess the total flavonoid content (TFC). In brief, a diluted extract (125 µL) was combined with 300 µL of a 5% NaNO2 solution and left to incubate for 5 min. Subsequently, this mixture was blended with 600µL of AlCl3 (10% w/v). Finally, the blend was mixed with 2000 µL of NaOH (1 M) and 2000 µL of distilled water to attain the desired final volume. The absorbances were recorded at 510 nm using a spectrophotometer. TFC was expressed as milligrams of quercetin equivalents (QUE) per gram of extract.

DPPH radical scavenging assay

The antioxidant activity of the samples was evaluated using the DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) free radical scavenging assay, following the method described by Brand-Williams et al.25. Briefly, 0.1 mL of each plant extract, prepared at different concentrations (50, 100, and 300 ppm), was mixed with 5 mL of 0.1 mM DPPH solution in methanol. The mixture was thoroughly shaken and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the samples was measured at 517 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer, with 80% methanol serving as the blank.

For comparison, a control solution (negative control) consisting of methanol and DPPH solution was included. Additionally, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) at varying concentrations was used as a positive standard. A volume of 1 mL of 0.2 mM DPPH solution in methanol was prepared for the BHT standard, and its absorbance was measured at 517 nm against the blank.

The percentage of DPPH scavenging activity in the samples was calculated using the following formula:

where, AA and AB are the absorbance values of the DPPH radical in the presence of the plant extract sample and the control, respectively.

Oxidative stress indicators

Malondialdehyde

The malondialdehyde (MDA) content, serving as an indicator of lipid peroxidation, was assessed using the thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reactive substances method as described by Taulavuori et al.26. Briefly, 0.5 g of powdered leaf samples were mixed with 5 mL of potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH = 7). After centrifuging the homogenate at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, 1.5 mL of TBA solution with a concentration of 0.5% in trichloroacetic acid (TCA) at 20% (w/v) was mixed with 0.5 mL of the supernatant. The mixture was then heated at 95 °C for 30 min. Following this, the reaction was halted by incubating the mixture on ice for 30 min. Subsequently, the absorbance was measured at 532 and 600 nm to correct for nonspecific turbidity. The MDA content was expressed as nmol per gram of sample.

Hydrogen peroxide

The hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content was measured following the method outlined Velikova et al.27. In brief, 0.1 g leaf sample was homogenized in 3 mL of 0.5% (w/v) TCA, followed by centrifugation. Then, 500 µL buffer phosphate 10 mM (pH = 7.5) and 2mL potassium iodide (KI) 1 M were added to the 500 µL of the supernatant. The mixture was held in darkness for 1 h at room temperature. Absorbance readings were taken at 410 nm, and the H2O2 content data were expressed in nmol per gram.

HPLC and quantification of phenolic composition

The phenolic compounds were assessed in two genotypes, no. 28 (wild, tolerant) and no. 34 (‘Mona’ cultivar, sensitive), selected based on the grain yield and grain yield loss criteria. The leaf samples from these genotypes, cultivated under two planting dates and two irrigation regimes, were used in this study. A total of 250 mg of dried leaf samples underwent extraction utilizing 25 mL of 80% methanol and agitated at 25 °C for 24 h. Following this, the extracts were filtered through a 0.22 μm disk, and then injected for analysis (20 µL) into an Agilent 1090 system, with detection wavelengths set at 260 and 350 nm. The high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) followed the protocol described by Roby et al.28. A 250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm, symmetry C18 column (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) accompanied with a guard column (10 × 4.6 mm ID, 5 μm) was employed for the analysis. The mobile phase consisted of a mixture of water and formic acid (99.9: 0.1) as solution A, and acetonitrile with formic acid (99.9: 0.1) as solution B, employing gradient elution at 25 °C and a flow rate of 0.8 mL min−1. The gradient commenced with a ratio of A: B (90:10) and was sustained for 1 min. Subsequently, there was a gradual increase from 10 to 26% B over 40 min, followed by an elevation from 26 to 65% B over 30 min. Finally, there was a progression from 65 to 100% B over 5 min, succeeded by an equilibration phase with 0–90% A for 4 min. Compound identification was performed by comparing retention times and UV spectra with pure standards sourced from Phytolab, Germany, with a purity exceeding 98%. The results were expressed in milligrams per 100 g of dry sample weight.

Abscisic acid extraction and quantification

To extract abscisic acid (ABA), 10 mL of 80% methanol and 0.1 g of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) were added to one g of fresh plant tissue, followed by homogenization at 4 °C. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 4000 g for 15 min. The supernatant was collected, and its pH was adjusted to 8. Methanol was evaporated under vacuum, and the residue was dissolved in 5 mL of deionized water. This process was repeated twice. In the final step, ethyl acetate was added to the extract, which was again subjected to evaporation. The remaining precipitate was dissolved in one mL of a solution containing 3% methanol and 0.1 M acetic acid29. The resulting solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane filter and injected into a reversed-phase HPLC column (Diamonsil C18, 5 μm, 25 cm × 4.6 mm) using an HPLC system (Unicam-Crystal-200, UK). A gradient mobile phase consisting of methanol and acetic acid (3–97%) was applied at a flow rate of 4 mL/min, and detection was carried out using a diode array detector. A standard solution of ABA (purity: 99.97%, Sigma) was used to calibrate the retention time and peak area. Quantification of ABA in the extracted samples was based on the calibration curve derived from the standard and the area under the corresponding peaks.

Extraction and quantification of IAA and GB

Extraction

A total of 2 g of plant tissue was ground in cold 80% (v/v) aqueous methanol and homogenized thoroughly. The homogenate was then extracted with 30 mL of cold 80% aqueous methanol under dark conditions at 4 °C. The resulting extract was centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was carefully collected30. The supernatant was subsequently filtered through filter paper to remove suspended particles. The retained solids were sequentially washed with the following solvents: methanol–acetic acid (100:1, v/v), methanol–water–acetic acid (50:50:1, v/v/v), methanol–water–acetic acid (30:70:1, v/v/v), and finally distilled water.

A volume of 100 mL of the combined filtrate was then passed through ten C18 solid-phase extraction (SPE) columns (J.T. Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA; 500 mg, 3 mL). The columns were preconditioned and washed with 10 mL of acidified water (pH adjusted to 3 with acetic acid), after which the phytohormones were eluted using 5 mL of an ethanol–water–acetic acid mixture (80:20:1, v/v/v). The eluent was evaporated to dryness under vacuum at room temperature. The dried residue was reconstituted in 1 mL of methanol and filtered through a 0.45 μm Whatman glass microfiber filter prior to HPLC analysis.

Quantification (HPLC analysis) of IAA and GA

Phytohormone analysis was performed following the protocols described by Zhen et al.31 (2008) and Liya et al.32 (2014), using HPLC system (Unicam Crystal 200, UK) equipped with a photodiode array (PDA) detector. A 10 µL aliquot of the prepared sample was injected into a reversed-phase C18 column (Zorbax SB-C18 100Å, 3.5 μm, 150 mm × 2.1 mm). The column temperature was maintained at 25 °C, and the flow rate was set to 0.3 mL/min.

The chromatographic separation was initiated with an isocratic elution using methanol–formic acid buffer (10:90, v/v) for 5 min, followed by a linear gradient to methanol–formic acid buffer (30:70, v/v) over 5 min. This condition was maintained isocratically for an additional 10 min, followed by a gradient to methanol–formic acid buffer (45:55, v/v) over 35 min, and finally held isocratically at 45:55 (v/v) for 15 min. Under these conditions, IAA and GA phytohormones were effectively separated within 45 min.

After each run, the column was washed with methanol–formic acid buffer (95:5, v/v) for 5 min, and then re-equilibrated using formic acid buffer–methanol (90:10, v/v) for 30 min. Quantification was based on the peak area of authentic standards under identical chromatographic conditions.

Grain yield

At physiological maturity, the middle plants of each plot were harvested, leaving a 25 cm margin at both ends of the rows. The grain yield was expressed as kilograms per hectare at approximately 14% grain moisture content. Grain loss attributable to water-deficit stress was calculated by subtracting the data obtained in water-deficit conditions from those in normal one.

Statistical analysis

The efficiency of the lattice design (LD) relative to the randomized complete block design (RCBD) was determined by calculating the ratio of error mean square in LD the RCBD. Due to minor distinctions between these two designs, we opted to employ the RCBD approach for data analysis in the experiments. In the current study, a combined analysis of variance (ANOVA) over the environments was conducted using the SAS statistical program version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). For mean comparisons, the least significant difference (LSD) test at a 95% confidence level (p < 0.05) was employed. The PROC CORR of SAS was used to calculate the correlation coefficients. A stepwise regression analysis was conducted using grain yield as the dependent variable and POX, APX, CAT, TPC, TFC, DPPH, MDA, and H2O2 as independent variables. Principal component analysis (PCA) was done to explore the associations between barley genotypes and variables. Subsequently, the biplot graph was generated using the Stat Graphics software (version 17.2).

Results

The influence of environmental conditions on traits

The results of the combined analysis of variance (ANOVA) are summarized in Table 1. Significant effects were observed for genotype, irrigation regime (drought), planting date (heat), and their interactions on most of the traits. However, the season (year) did not significantly affect most traits, although its interaction with other sources of variation was significant for a few traits. Supplementary Tables S4–S9 present mean trait values for 36 barley genotypes, including TPC, TFC, POX, APC, CAT, MDA, H₂O₂, DPPH activity, and grain yield. Table S10 presents the quantities of 14 phenolic compounds identified by HPLC in two contrasting genotypes (one wild and one cultivated) in response to WS, HS, and combined WS-HS stress.

Antioxidant defense parameters

Enzymatic antioxidants

The activities of the antioxidant enzymes CAT, APX, and POX increased significantly under all stress conditions across two agronomic seasons (Table 2, Tables S4 and S7). As illustrated in Fig. 1, the mean enzyme activities for wild and cultivated barley genotypes under the four environmental treatments (control, water stress, heat stress, and combined stress) revealed that wild genotypes consistently exhibited higher antioxidant enzyme activity under stress conditions compared to cultivated ones. This trend suggests that wild barley may possess more effective oxidative stress mitigation mechanisms, contributing to greater tolerance to abiotic stress.

Mean comparison of enzymatic antioxidants (a) POX: Guaiacol peroxidase, (b) APX: Ascorbate peroxidase, and (c) CAT: Catalase) of wild and cultivated barley grown under normal (N), water stress (WS), heat stress (HS), and combined water and heat stress (WS-HS) conditions. Bars represent means ± SE, and bars with the same letter do not significantly differ at p < 0.05 among the genotypes.

Among the enzymes, CAT and POX displayed the most pronounced increases under combined water and heat stress (WS-HS). Specifically, CAT activity increased by 128% in wild genotypes and by 148% in cultivated genotypes compared to control conditions. However, under the WS-HS condition, CAT activity was 82% higher in wild genotypes than in cultivated ones, indicating a potentially more robust catalase-based detoxification system in wild barley (Fig. 1c). Similarly, POX activity increased by 213% in wild genotypes and 124% in cultivated genotypes compared to the control, with a 41% higher activity observed in wild genotypes than in cultivated genotypes under WS-HS (Fig. 1a).

The activity of APX was highest under water stress (WS) alone (Fig. 1b). Wild genotypes exhibited a 135% increase in APX activity relative to the control, while cultivated genotypes showed an even greater increase of 256%. However, when comparing the two genotypes under WS, APX activity in wild barley was still 71% higher than in cultivated barley, suggesting a differential regulatory response in the ascorbate-glutathione cycle.

Overall, CAT, APX, and POX activities were more strongly induced under water deficit than heat stress alone, indicating that drought imposes a greater oxidative challenge on barley plants. Furthermore, under heat stress, wild genotypes still showed higher enzymatic activity levels compared to cultivated ones, with increases of 156%, 77%, and 18% for CAT, APX, and POX, respectively. These findings collectively support the notion that wild barley genotypes have more efficient enzymatic antioxidant defense systems, which may contribute to their superior tolerance to combined abiotic stresses.

Non-enzymatic antioxidants

Wild genotypes generally exhibited higher levels of TPC and TFC under all stress conditions compared to cultivated genotypes (Fig. 2, Tables S5 and S8). Under combined water and heat stress, heat stress, and water stress, the TPC in wild genotypes was 28%, 45%, and 30% higher, respectively, than in cultivated genotypes. Similarly, TFC levels in wild genotypes were 61%, 51%, and 66% higher than those in cultivated genotypes under the same respective conditions. These findings indicate that wild barley genotypes possess a greater capacity to accumulate phenolic and flavonoid compounds, which likely contribute to their enhanced tolerance to environmental stresses.

Mean comparison of (a) total phenolic content (TPC) and (b) total flavonoid content (TFC) of wild and cultivated barleys under normal (N), water stress (WS), heat stress (HS), and combined water and heat stress (WS-HS) conditions. Bars represent means ± SE and bars with the same letter do not significantly differ at p < 0.05 among the genotypes.

Among the wild barley genotypes, genotypes no. 28 and 4 showed the highest TPC levels under combined drought and heat stress conditions (Tables S5 and S8). In general, all genotypes—wild and cultivated—showed increased TPC and TFC in response to drought, heat, and combined stress treatments. Among cultivated genotypes, the drought-tolerant cultivars ‘Yosef’ and ‘Goharan’ exhibited the greatest increases in TPC and TFC levels.

The most significant accumulation of TPC was observed under combined water and heat stress, where wild and cultivated genotypes showed increases of 303% and 288%, respectively, compared to the control (Fig. 2a). Heat stress alone induced a greater increase in TPC (211% in wild and 163% in cultivated genotypes) than water stress (126% in wild and 113% in cultivated genotypes), suggesting that TPC plays a more substantial role in heat stress tolerance than in water deficit conditions.

In contrast, the highest TFC levels were observed under combined water and heat stress, with increases of 132% in wild and 74% in cultivated genotypes compared to the control (Fig. 2b). Under water stress, TFC increased by 75% in wild and 27% in cultivated genotypes, while under heat stress, the increases were 42% and 14%, respectively. These results suggest that TFC may contribute more significantly to tolerance against water deficit stress than to heat stress.

DPPH radical scavenging capacity

Antioxidant activity, assessed using the DPPH radical scavenging assay, increased significantly under various abiotic stress conditions in both agronomic seasons (Fig. 3, Tables S6 and S9). Specifically, heat stress led to increases of 40% and 34% in wild and cultivated genotypes, respectively, while drought stress resulted in increases of 62% in wild and 46% in cultivated genotypes. Under combined drought and heat stress, antioxidant activity rose even more markedly (by 86% in wild genotypes and 64% in cultivated genotypes) relative to the control (Fig. 3).

Mean comparison of free radical scavenging capacity (DPPH) of wild and cultivated barley under normal conditions (N), water stress (WS), heat stress (HS), and combined water and heat stress (WS-HS) conditions. Bars represent means ± SE and bars with the same letter do not significantly differ at p < 0.05 among the genotypes.

These findings demonstrate that both wild and cultivated barley genotypes activate antioxidant defense mechanisms in response to environmental stresses, with wild genotypes consistently showing a greater antioxidant capacity. This trend was clearly reflected in the overall mean values across genotypes, where wild barley exhibited significantly higher DPPH activity than cultivated barley under all stress conditions (Tables 2 and 3). Specifically, antioxidant activity in wild genotypes was 48%, 37%, and 45% higher than in cultivated genotypes under combined, heat, and water stress conditions, respectively (Fig. 3).

The greater antioxidant activity observed in wild genotypes suggests the presence of more robust oxidative stress mitigation mechanisms, which may contribute to their enhanced tolerance to combined and individual environmental stressors. These results further support the potential utility of wild barley germplasm in breeding programs aimed at improving stress resilience in cultivated varieties.

Oxidative stress indicators

To assess the extent of oxidative damage induced by abiotic stress, MDA and H₂O₂ levels were measured in the leaves of barley genotypes. These biochemical markers are widely recognized as indicators of ROS accumulation and lipid peroxidation under stress conditions. The results revealed significant differences among genotypes, with cultivated barley generally exhibiting higher MDA and H₂O₂ levels than wild genotypes across all stress treatments (Fig. 4, Tables S6 and S9).

Mean comparison of (a) MDA: Malondialdehyde, and (b) H2O2: Hydrogen peroxide of wild and cultivated barley under normal (N), water stress (WS), heat stress (HS), and combined water and heat stress (WS-HS) conditions. Bars represent means ± SE and bars with the same letter do not significantly differ at p < 0.05 among the genotypes.

Under combined water and heat stress (WS-HS), MDA levels increased by 21%, 16%, and 28% in cultivated barley compared to wild barley under combined, heat, and water stress, respectively. Similarly, H₂O₂ accumulation in cultivated genotypes was 33%, 25%, and 33% higher than in wild genotypes under the same respective stress conditions (Fig. 4). These findings indicate that cultivated barley is more prone to oxidative damage than wild barley under adverse environmental conditions.

Among the stress treatments, drought stress led to the most pronounced increases in both MDA and H₂O₂ contents. Under WS-HS, MDA content increased by 215% in wild and 237% in cultivated genotypes relative to control conditions (Fig. 4a). In parallel, H₂O₂ levels rose by 139% and 244% in wild and cultivated genotypes, respectively (Fig. 4b). Under drought stress alone, H₂O₂ increased by 77% in wild and 156% in cultivated genotypes, while under heat stress, respective increases were 53% and 97%. For MDA, drought stress also induced greater lipid peroxidation than heat, with increases of 145% and 156% in wild barley and 189% and 160% in cultivated barley under water deficit and heat stress, respectively, compared to controls.

The early-maturing cultivar ‘Mona,’ known for its sensitivity to abiotic stress, exhibited the highest MDA levels under drought and combined stress conditions, reinforcing its vulnerability to ROS-induced membrane damage. These data collectively suggest that drought stress imposes greater oxidative and cellular damage on barley than heat stress, as evidenced by the elevated accumulation of both MDA and H₂O₂, particularly in cultivated genotypes.

Overall, the higher oxidative damage under drought compared to heat stress underscores the greater destructive potential of water deficit on barley physiology. The lower MDA and H₂O₂ levels observed in wild genotypes support the hypothesis that wild barley possesses more robust antioxidant defense systems, limiting ROS accumulation and lipid peroxidation under stress conditions.

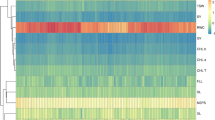

Phenolic composition analysis

Table 3 presents the mean concentrations of phenolic compounds, including both phenolic acids and flavonoids, extracted from the leaves of barley genotypes cultivated under four distinct environmental conditions, as analyzed by HPLC. A total of 14 phenolic compounds were identified and quantified (Table S10), including phenolic acids—p-coumaric, gallic, syringic, ellagic, ferulic, vanillic, caffeic, 4-hydroxybenzoic, chlorogenic, and rosmarinic acids—and flavonoids such as apigenin, luteolin, quercetin, and rutin.

Significant genotype-specific differences were observed in the accumulation of phenolic compounds between wild and cultivated barley genotypes under both normal and stress conditions, across two planting dates. Syringic acid was identified as the most abundant phenolic acid, followed by ellagic acid and the flavonoid rutin. Except for p-coumaric acid, the concentration of all identified phenolic components increased in response to abiotic stress, particularly under heat and combined heat and drought stress (WS-HS). In general, these compounds accumulated to a greater extent in wild genotypes compared to cultivated ones, with the exceptions of vanillic acid and rosmarinic acid, which were more prevalent in cultivated barley.

A more pronounced increase in phenolic compound accumulation was observed under heat stress than under water deficit, indicating that high temperatures may exert a stronger stimulus on phenolic biosynthesis pathways than drought alone. Quantitative differences among genotypes were considerable. The syringic acid content ranged from 487 to 1935 mg 100 g−1 DW in wild genotypes, compared to 97 to 240 mg 100 g−1 DW in cultivated ones. The highest concentration of ellagic acid was observed in wild barley under drought stress during the second planting date, where its level was 47% higher than that of the corresponding cultivated genotype.

The p-coumaric acid content exhibited a variable trend, ranging from 120 to 590 mg 100 g−1 DW under combined stress conditions and normal in wild barley, and from 147 to 561 mg 100 g−1 DW under the same conditions in cultivated barley. Ferulic acid levels were highest under WS-HS conditions, showing a 36% increase in wild and a notable 332% increase in cultivated genotypes, indicating a substantial stress-induced upregulation in phenolic acid biosynthesis, particularly in cultivated barley. Gallic acid also showed a marked response to combined stress, with increases of 170% and 212% in wild and cultivated genotypes, respectively. These increases suggest that gallic acid plays a key protective role under simultaneous drought and heat stress conditions. Other phenolic acids (vanillic, caffeic, 4-hydroxybenzoic, chlorogenic, and rosmarinic acids) were present in lower concentrations relative to the major phenolics. A similar trend was noted for less abundant flavonoids such as luteolin and quercetin, which showed relatively minor fluctuations under stress (Fig. 5).

Mean comparison of wild and cultivated barleys for grain yield (kg ha−1) under normal conditions (N), water stress (WS), heat stress (HS), and combined water and heat stress (WS-HS) conditions. Bars represent means ± SE and bars with the same letter do not significantly differ at p < 0.05 among the genotypes.

Among the flavonoids, rutin concentrations ranged from 101 to 179 mg 100 g−1 DW in wild genotypes and 87 to 359 mg 100 g−1 DW in cultivated ones. Interestingly, rutin content was significantly higher in cultivated genotypes under heat (13% higher) and combined stress (101% higher) compared to wild types, suggesting possible genotype-specific regulation of flavonoid synthesis pathways. The accumulation of apigenin, another important flavonoid, also significantly increased under combined stress, with 264% and 187% increases observed in wild and cultivated genotypes, respectively.

Collectively, these results suggest that wild barley genotypes possess a more robust and diverse phenolic profile in response to environmental stress, contributing to their enhanced oxidative stress tolerance. Moreover, the stronger induction of specific phenolics under heat and combined stresses emphasizes the potential adaptive role of these secondary metabolites in plant defense.

Hormone analysis

The concentrations of key phytohormones (ABA, IAA, and GA) varied significantly between wild and cultivated barley genotypes under different environmental conditions (Fig. 6). ABA levels increased markedly under all stress treatments in both genotypes, consistent with its known function as a central stress-response hormone (Fig. 6a). The highest ABA concentration was recorded under combined drought and heat stress (WS-HS) in the cultivated genotype, which was approximately 10% higher than in the wild genotype under the same condition. Notably, under control (non-stress) conditions, the cultivated genotype exhibited 58% more ABA than the wild genotype, indicating a constitutively higher basal level. Overall, the cultivated genotype consistently showed higher ABA levels than the wild genotypes across all treatments.

Mean comparison of wild and cultivated barleys for phytohormones [ABA (a), IAA (b), and GB (c)] under normal conditions (N), water stress (WS), heat stress (HS), and combined water and heat stress (WS-HS) conditions. Bars represent means ± SE. Bars with the same letter do not significantly differ at p < 0.05 among the genotypes.

The greatest increase in ABA compared to the control was observed under WS-HS conditions, where levels rose by 81% in the wild and 26% in the cultivated genotype. The ABA increase under water stress alone was more pronounced than under heat stress in both genotypes. Specifically, ABA increased by 74% in the wild and 21% in the cultivated genotype under water stress, while increases under heat stress were 10% and 8%, respectively. These findings underscore the critical role of ABA in mediating drought responses, with more moderate induction under thermal stress.

IAA exhibited a more complex pattern of regulation (Fig. 6b). The sharpest decline in IAA content occurred under drought stress, with reductions of 31% in the wild and 29% in the cultivated genotype. Interestingly, under heat stress, IAA levels increased by 11% in the cultivated genotype, whereas it decreased by 9% in the wild genotype, suggesting genotype-specific hormonal plasticity in response to thermal conditions. Under combined WS-HS stress, both genotypes experienced IAA reductions, with the wild genotype exhibiting a greater decline than the cultivated one. In general, the wild genotype maintained higher IAA concentrations than the cultivated genotype across all treatments, with the largest difference (45%) observed under normal conditions.

GA followed a contrasting trend to ABA, showing reduced levels under stress (Fig. 6c). The cultivated genotype consistently exhibited higher GA concentrations than the wild genotype. The most substantial genotype difference was recorded under drought stress, where the cultivated genotype had 135% more GA than the wild genotype, followed by 98% more under heat stress. The highest GA level was observed under control conditions in the cultivated genotype (139 ng/g DW), followed by heat stress (130 ng/g DW).

The greatest GA decline occurred in the wild genotype under drought stress (37% decrease compared to control), while in the cultivated genotype, the largest decrease was under combined WS-HS stress (25% decrease). These results indicate that drought imposed a stronger suppressive effect on GA biosynthesis than heat stress in both genotypes, aligning with the role of GA suppression in stress avoidance strategies, such as growth inhibition.

In summary, the hormonal profiling revealed distinct stress-response strategies between wild and cultivated barley genotypes. The cultivated genotype exhibited a stronger ABA response and higher GA baseline levels, potentially supporting faster growth and stress perception. In contrast, the wild genotype maintained higher IAA levels and displayed greater plasticity in GA and IAA regulation, suggesting a more conservative and adaptable hormonal response to environmental stress.

Grain yield

The impact of abiotic stresses on grain yield was notably less severe in wild barley genotypes compared to cultivated ones. Specifically, grain yield reductions in wild genotype were 11%, 27%, 32%, and 41% than those in cultivated genotype under combined heat and drought stress, heat stress, water stress, and non-stress respectively (Fig. 5). These findings highlight the superior resilience of wild genotypes in maintaining grain production under adverse environmental conditions.

A significant variation in grain yield was observed among the barley genotypes, and more importantly, it was confirmed that these stress conditions substantially affect traits associated with the antioxidant defense system.

Plant growth attributes, such as grain yield and plant dry weight, are key indicators of plant performance under environmental stress. When one of these parameters is significantly influenced, it becomes critical to explore related physiological and biochemical traits to understand the underlying mechanisms of stress adaptation. Grain yield data for the 36 barley genotypes under four distinct environmental conditions (non-stress (N), water stress (WS), heat stress (HS), and combined water and heat stress (WS-HS)) are provided in Supplementary Tables S3–S9. Across both growing seasons, all genotypes exhibited yield reductions under stress conditions, whether imposed by terminal drought, heat, or their combination. The genotypes ‘Goharan’ and ‘Yosef’ consistently recorded the highest grain yields under drought stress during the normal planting period, suggesting their greater drought adaptability among cultivated types.

Overall, yield losses were markedly higher in cultivated genotypes than in wild types. Under drought stress, grain yield declined by 24% in wild and 34% in cultivated genotypes; under heat stress, the reductions were 45% and 56%, respectively; and under combined drought and heat stress, yield losses reached 57% in wild and 72% in cultivated genotypes (Fig. 5). These results confirm that wild barley genotypes possess a higher tolerance to abiotic stress, which may be attributed to their inherent physiological and biochemical defense mechanisms.

Relationships of traits

Correlation coefficients among the studied traits under water stress (WS), heat stress (HS), and combined water and heat stress (WS-HS) conditions are presented in Table 4. Grain yield showed a significant positive correlation with POX, CAT, TPC, and DPPH, while it exhibited a negative correlation with H2O2 across all stress treatments. Additionally, enzymatic antioxidant activities were positively correlated with phenolic compounds and negatively correlated with MDA and H2O2. As expected, a strong positive correlation was found between TPC and TFC (r = 0.80, r = 0.53, r = 0.60 under WS, HS, and WS-HS, respectively). TPC and TFC exhibited positive correlations with DPPH radical scavenging activity under heat stress (HS, r = 0.44) and combined water and heat stress (WS-HS, r = 0.38). A strong negative correlation was observed between TFC and H2O2 (r = − 0.77). Furthermore, H2O2 accumulation showed negative correlations with antioxidant enzyme activities and secondary metabolites, while positively correlating with MDA across all treatments. Notably, a strong positive correlation between TFC and CAT was detected under water-deficit conditions (r = 0.80). Stepwise regression analysis was conducted to identify the most influential variables contributing to grain yield under water stress, heat stress, and combined water and heat stress (Table 5). The results indicated that POX, followed by TPC and DPPH, were the strongest predictors of grain yield under water stress, explaining 78% of the variation in grain yield. Under heat stress due to delayed planting, CAT, followed by H2O2 and POX, emerged as key predictors, explaining 81% of the variation. For combined WS-HS, DPPH and CAT were the most reliable predictors of grain yield.

The results of antioxidant capacity and phenolic compound analyses indicated that stress affects the plant’s defense mechanisms, with different genotypes exhibiting varied responses to these stresses. Notably, catalase activity across all treatments, and DPPH in drought stress and combined drought and heat stress, accounted for a significant proportion of the variance. Therefore, these traits can be considered reliable selection criteria for identifying stress-tolerant genotypes.

Principal component analysis

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to differentiate genotypes and assess the relationships among traits under normal and drought conditions, as well as varying planting dates and the interaction between drought and planting date. The analysis utilized all genotypes and evaluated traits, and biplots were constructed using the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) for each condition (Fig. 7a-d). Under water stress, three distinct genotypic groups were identified, with cultivated and wild genotypes such as G4, G7, G8, G10, G13, G18, and G28 showing high values for TFC, TPC, APX, POX, and grain yield (Fig. 7b). For planting dates, wild genotypes G2, G4, G6, G7, G8, G10, G18, G20, G21, G26, and G28 exhibited high values for TPC, TFC, DPPH, POX, APX, and grain yield (Fig. 7c).

Biplot of barley genotype based on the mean values obtained from each trait during the 2-year study period for the (a) normal, (b) water stress, (c) heat stress, and (d) combined water and heat stress conditions; GY: Grain yield per plot; POX: Guaiacol peroxidase; APX: Ascorbate peroxidase; CAT: Catalase; TPC: Total phenolic contents, TFC: Total flavonoid contents, DPPH: Free radical scavenging capacity, MDA: Malondialdehyde, H2O2: Hydrogen peroxide.

Figure 7d presents a biplot depicting the interrelationships among genotypes and traits under water deficit and heat stress conditions (WS-HS). The first two principal components explained 73.61% of the total variation. According to the biplot, genotypes G3, G4, G8, G10, G13, G18, G21, G26, and G28 exhibited relatively higher PC1 values but lower PC2, indicating that these genotypes may be considered superior candidates for breeding cultivars suited for both drought and heat stress conditions.

Discussion

Enzymatic antioxidants

Stress conditions such as drought, heat, and particularly their combination, are known to induce overproduction of ROS, as supported by our findings. In the present study, CAT activity showed the highest increase under combined stress, followed by drought stress, in both wild and cultivated barley genotypes. This suggests that CAT plays a more prominent role in mitigating oxidative damage during combined or drought stress compared to heat stress alone. Interestingly, both genotypes exhibited a similar pattern of CAT induction under stress conditions, although the wild genotype demonstrated a greater capacity to enhance CAT activity. This aligns with the findings of Hard et al.33 who reported upregulation of CAT-related genes after 9 days of drought exposure. Zhanassova et al.34 also observed increased CAT and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in barley roots (but not shoots) under combined drought and heat stress.

APX activity was most strongly induced under drought stress in both genotypes, which is noteworthy considering that drought stress resulted in the least grain yield reduction. This suggests a critical role of APX in stress tolerance mechanisms. Although APX levels were higher in the cultivated genotype, the wild genotype experienced less yield loss, implying that additional protective mechanisms may be more active in the wild genotype. Barley genotypes respond differently to drought stress; for example, APX gene expression was upregulated in the Run and Yarmouk genotypes after 16 and 2 days of drought treatment, respectively33. While APX induction under heat stress was lower than in drought, its activity was elevated under combined stresses, indicating its dual but stress-specific role. However, previous studies have suggested that APX responds less intensely to stress compared to other antioxidant enzymes35.

POX activity followed a trend similar to that of CAT, with its highest increase observed under combined stress conditions. Like CAT, POX activity was higher in the wild genotype. However, under heat stress, POX showed a stronger response than CAT, suggesting that POX may play a more significant role in heat stress tolerance, while CAT is more effective under drought conditions. Both enzymes contribute synergistically to antioxidant defense under combined stress. CAT, a heme-containing enzyme, is particularly important in detoxifying H₂O₂ by converting it to water, thus limiting oxidative damage36. Enhanced CAT activity under drought has been widely documented in various crops, including barley37 wheat38 and maize39. Consistent with these findings, our results indicate that genotypes with superior ROS-scavenging capacities (reflected by increased CAT and POX activities) exhibited greater resilience under combined stress conditions.

Non-enzymatic antioxidants

Phenolic compounds, including flavonoids, lignans, and tannins, are among the most prevalent phytochemicals in plants. They modulate cellular signaling pathways to activate cellular defense mechanisms that protect cells against ROS and act as antioxidants by scavenging ROS24,40,41. Studies, such as those on Amaranthus species, have shown that drought, heat, and their combination stimulate the accumulation of bioactive compounds like phenolics and flavonoids42. However, the effects of these stresses on the concentration and biological activity of phenolic compounds vary depending on the genotype’s tolerance or sensitivity, as observed by Laddomada et al.43 in their study on durum wheat. El Haddad et al.44 reported higher flavonoid and phenolic contents in drought-tolerant lentil genotypes subjected to heat and drought stress. Under elevated temperature and drought stress conditions, the increased antioxidant capacity observed in tolerant genotypes helps mitigate oxidative damage to membranes and proteins. Tolerant species were found to accumulate more non-enzymatic antioxidants compared to sensitive species, as demonstrated in this study. According to Hassan et al.45 the accumulation of total phenolic and flavonoid compounds is strongly linked to drought stress tolerance, owing to their potent antioxidant properties. Kowalczewski et al.15 demonstrated that radiation and drought stress significantly affect the polyphenolic profile of green barley, enhancing its antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. They found that the chemical profile of the samples was more influenced by barley genotype and watering period than by radiation intensity. They also reported that sinapic acid, ferulic acid, and sinapoyl-beta-glucose were the most discriminative phenolic compounds under abiotic stress conditions in barley grains (H vulgare L)15. Heat stress has been shown to increase phenolic compounds in wheat grains, including total polyphenols, flavonols, phenolic acids, proanthocyanidins, and anthocyaninsmade46. Additionally, Sayed et al.47 found that flavonoids provide photoprotection against high temperatures and drought stress. Consistent with these findings, higher accumulation of flavonoids, saponins, and tannins has also been reported in wheat exposed to drought and heat stress48.

Previous studies have shown that antioxidant defenses, including enzymatic (e.g., CAT, POX) and non-enzymatic (e.g., phenols) compounds, play important roles in alleviating oxidative damage caused by environmental stresses like drought2 and heat4. Wild genotypes often possess higher antioxidant capacity, which enables them to better cope with combined stresses. Additionally, the observed reduction in yield under heat stress has been widely documented, as heat stress directly impacts photosynthetic efficiency and cell integrity, leading to a more pronounced decrease in productivity compared to other stress factors like water deficit15.

DPPH radical scavenging capacity

The scavenging of DPPH free radicals serves as a common antioxidant assay and acts as a protective mechanism against stress in plant cells49. Consequently, the current study supports the role of DPPH radical scavenging activity, which was closely correlated with the concentration of polyphenols in plant tissues and, by extension, with stress tolerance. A similar observation was reported by Kiani et al.24 in wheat. The combined effects of heat and drought stress are believed to enhance the scavenging capacity of antioxidants triggered by both stressors, thereby increasing the plant’s ability to cope with environmental challenges50. This synergistic interaction highlights the importance of antioxidants in mitigating oxidative damage caused by stress, which is crucial for maintaining plant health and sustaining growth. Studies suggest that the activity of these enzymes and polyphenol antioxidants varies widely both within and among species, yet consistently plays a critical role in plant adaptation to abiotic stress2. Enhanced antioxidant capacity helps mitigate oxidative damage to membranes and proteins, thereby preserving cellular and organelle function and overall plant performance. The types and quantities of antioxidant enzymes significantly varies among plant species.

Oxidative stress indicators

Oxidative damage is a natural byproduct of aerobic respiration in plants and is exacerbated by environmental stressors such as high temperatures and drought, which caused an increased accumulation of ROS34. MDA, a well-established indicator of oxidative damage in various crops, including barley51 aligns with the findings of our study Our results also revealed a positive correlation between higher MDA concentrations and increased H2O2 levels under drought stress conditions. High concentrations of H2O2 are known to cause cellular damage. As a key mediator of oxidative stress, H2O2 interacts with superoxide to generate reactive oxygen species, exacerbating cellular damage51. The lower accumulation of MDA and H2O2 in H. spontaneum compared to cultivated barley under heat, drought, and their combined stress conditions may be attributed to the enhanced activation of antioxidant defenses, including enzymes and polyphenols. These defenses play a crucial role in detoxifying MDA and H2O2, thereby mitigating their harmful effects2.

As a marker of lipid peroxidation, MDA indicates oxidative damage via free radical-induced oxidation of membrane polyunsaturated fatty acids44,51. Among the genotypes, cultivated barley cultivars ‘Mona’ and ’Reyhan’ showed the highest H2O2 levels. These cultivars have been previously identified as sensitive to heat7,13 stress and salinity51. Similar increases in MDA and H2O2 under salinity stress have been reported in wild and cultivated wheat genotypes, reinforcing the association of these markers with abiotic stress tolerance24.

Recent studies have highlighted the potential role of plant growth regulators (PGRs) in modulating stress responses and improving plant resilience52. In the present study, phytohormonal responses, including those of ABA, GB, and IAA, exhibited significant alterations under individual and combined stress conditions. Notably, ABA content increased substantially in both genotypes under all stress treatments, with the highest accumulation observed under combined water and heat stress (WS-HS). This response was more pronounced in the wild genotypes, indicating a stronger stress-adaptive mechanism, possibly reflecting its evolutionary adaptation to harsh environments.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that ABA plays a central role in mediating drought tolerance by inducing stomatal closure, reducing water loss, and activating antioxidant defense systems52,53. It has also been shown that ABA levels increase more sharply under drought than heat stress, which aligns with our results showing the greatest ABA increase under drought-related treatments. Interestingly, while the cultivated genotype had higher baseline ABA levels under control conditions, the wild genotype showed a greater fold increase under stress.

GA, traditionally known for promoting growth, was found to decrease under all stress conditions in our study, with the greatest reduction observed under drought stress in the wild genotype and under combined stress in the cultivated genotype. These results are in line with earlier reports indicating that abiotic stress suppresses GA biosynthesis to prioritize survival over growth54. Additionally, exogenous application of GA has been shown to restore growth and enhance drought tolerance through improved photochemical efficiency and ROS scavenging. The cultivated genotype maintained GA levels more effectively than the wild type, possibly due to domestication-related selection for growth stability under mild stress. Moreover, both ABA and GA were more abundant in the cultivated genotype under control conditions, likely reflecting hormonal regulation selected through breeding for high-yield performance under optimal environments.

In contrast, IAA levels displayed a unique pattern. Under drought stress, both genotypes showed a reduction in IAA content, with the wild genotype exhibiting a more substantial decrease. However, under heat stress, IAA levels slightly increased in the cultivated genotype while decreasing in the wild genotype. These observations suggest that IAA-mediated stress responses are genotype-specific and stress-type dependent. Previous studies have reported that drought-induced repression of IAA biosynthesis and signaling genes correlates with developmental inhibition and spikelet sterility, particularly in cereals such as rice55,56. Interestingly, our results revealed that wild barley consistently had higher IAA levels than the cultivated genotype, particularly under non-stressed conditions, implying that IAA may play a more prominent role in the intrinsic stress tolerance mechanisms of wild barley.

Taken together, our findings demonstrate that the differential modulation of ABA, GA, and IAA under stress is genotype-specific and closely associated with adaptive responses. The strong ABA induction and more stable IAA levels in the wild genotype, along with better GA retention in the cultivated genotype, highlight potential targets for improving stress resilience through phytohormone-based breeding strategies. Future efforts to manipulate the biosynthesis, catabolism, or signaling pathways of these key hormones could offer promising avenues for engineering abiotic stress tolerance in barley and related cereals.

Grain yield

The grain yield loss due to water stress, heat stress, and their combined effects was significantly lower in wild genotypes compared to their cultivated relative. This observation is consistent with previous studies indicating that H. spontaneum genotypes exhibit milder responses to drought57 and heat8 stress compared to cultivated barley. Wild genotypes, particularly those adapted to extreme climates, are believed to possess inherent tolerance mechanisms, likely a result of their evolutionary history in environments characterized by water scarcity and temperature fluctuations. These findings are valuable for breeding programs focused on enhancing drought and heat tolerance in cultivated barley.

Additionally, a delayed planting resulted in heat stress during terminal growth stages, leading to a significant reduction in grain yield across both wild and cultivated genotypes. This emphasizes the critical role of planting date selection in regions with arid climates, such as Iran, where proper timing can mitigate the adverse effects of both drought and heat stress. Our findings underline the importance of considering environmental factors, particularly in the context of climate change, when determining optimal planting schedules. One key finding from this study is that the timing of planting is more critical to barley grain yield than the influence of irrigation (water stress). Delaying planting impedes proper growth and reduces the time available for plant development, potentially leading to inadequate grain formation during the grain-filling period and, ultimately, lower yields. Grain yield reductions can also be linked to disruptions in meiosis, pollen infertility, and seed abortion, which are induced by high temperatures during critical stages of pollen development and grain filling8,58. Winter cereal crops, such as wheat and barley, are vulnerable to high-temperature stress during their reproductive stages, which negatively impacts their reproductive organs and restricts carbon availability during grain filling8. It is suggested that wild relatives of cereal species, particularly those from centers of origin such as the Fertile Crescent, may possess unique tolerance genes for abiotic stress that differ from those found in domesticated species, having evolved through diverse mechanisms8. Our results support this hypothesis, as wild barley genotypes exhibited significant genetic variation in their tolerance to water stress, heat stress, and combined water and heat stress.

Conclusion

This study comprehensively evaluated the responses of wild and cultivated barley genotypes to drought, heat, and combined stress conditions by assessing key enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants, and hormones. The results revealed that wild genotypes exhibited superior tolerance to abiotic stress compared to cultivated ones, as evidenced by lower reductions in grain yield, as well as better maintenance of phytohormone balance and antioxidant defense. Wild genotypes accumulated significantly less MDA and H₂O₂, indicating reduced oxidative damage. Enhanced activities of antioxidant enzymes such as CAT, POX, and APX, along with higher TPC, TFC, and radical scavenging activity (DPPH), contributed to the improved oxidative stress management in wild barley. Additionally, stress-induced increases in ABA were more regulated in wild genotypes, while IAA and GB levels were better maintained, supporting continued growth and development under stress.

Phenolic profiling via HPLC identified syringic acid and ellagic acid as dominant phenolic acids, and apigenin and rutin as key flavonoids, with significantly higher accumulation in wild genotypes under stress conditions, especially under combined drought and heat stress. Notably, most phenolic compounds increased more under heat than drought stress, while ABA accumulation and oxidative damage were more pronounced under drought. These findings highlight the key role of ABA in drought and phenolic compounds in scavenging ROS during heat stress. The combined stress conditions triggered the highest antioxidant response, indicating a synergistic effect of drought and heat. Overall, the superior antioxidant and hormone responses of wild barley genotypes underscore their potential as valuable genetic resources for improving abiotic stress tolerance in cultivated barley through breeding and biotechnology.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- ABA:

-

Abscisic acid

- APX:

-

Ascorbate peroxidase

- CAT:

-

Catalase

- DPPH:

-

2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- GB:

-

Gibberellin

- POX:

-

Guaiacol peroxidase

- HT:

-

Heat stress

- H2O2 :

-

Hydrogen peroxide

- HPLC:

-

High-performance liquid chromatography

- IAA:

-

Indole-3 acetic acid

- MDA:

-

Malondialdehyde

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- TFC:

-

Total flavonoid content

- TPC:

-

Total phenolic content

- WS:

-

Water stress

- WS-HT:

-

Combined water and heat stress

References

Farhad, M. et al. Heat stress in wheat: A global challenge to feed billions in the current era of the changing climate. Front. Sustainable Food Syst. 7, 1203721. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2023.1203721 (2023).

Haghpanah, M., Hashemipetroudi, S., Arzani, A. & Araniti, F. Drought tolerance in plants: physiological and molecular responses. Plants 13, 2962. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants13212962 (2024).

Zandalinas, S. I., Mittler, R., Balfagón, D. & Arbona, V. Gómez-Cadenas, A. Plant adaptations to the combination of drought and high temperatures. Physiol. Plant. 162, 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppl.12540 (2018).

Vaezi, B., Arzani, A. & RobertsT. H. How do drought, heat stress, and their combination impact stem reserve mobilization in wheat genotypes? Agronomy 14, 1867. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy14081867 (2024).

Sato, H., Mizoi, J., Shinozaki, K. & Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Complex plant responses to drought and heat stress under climate change. Plant J. 117, 1873–1892. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.16612 (2024).

Gommers, C. Keep cool and open up: temperature-induced stomatal opening. Plant Physiol. 182, 1188–1189. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.20.00158 (2020).

Bahrami, F., Arzani, A. & Rahimmalek, M. Tolerance to high temperature at reproductive stage: Trade-offs between phenology, grain yield and yield‐related traits in wild and cultivated barleys. Plant. Breed. 140, 812–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbr.12953 (2021).

Arzani, A. & Ashraf, M. Smart engineering of genetic resources for enhanced salinity tolerance in crop plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 35, 146–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352689.%202016.1245056 (2016).

Jedmowski, C., Ashoub, A., Momtaz, O. & Brüggemann, W. Impact of drought, heat, and their combination on chlorophyll fluorescence and yield of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum). J. Bot. 2015 (120868). https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/120868 (2015).

Lakew, B. et al. The potential contribution of wild barley (Hordeum vulgare ssp. spontaneum) germplasm to drought tolerance of cultivated barley (H. vulgare ssp. vulgare). Field Crops Res. 120, 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2010.09.011 (2011).

Cai, K. et al. Screening of worldwide barley collection for drought tolerance: the assessment of various physiological measures as the selection criteria. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 1159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.01159 (2020).

Saed-Moucheshi, A. et al. Screening barley varieties tolerant to drought stress based on tolerant indices. J. Plant Nutr. 45, 739–750. https://doi.org/10.1080/01904167.2021.1963773 (2022).

Bahrami, F., Arzani, A. & Rahimmalek, M. Photosynthetic and yield performance of wild barley (Hordeum vulgare ssp. spontaneum) under terminal heat stress. Photosynthetica 57 https://doi.org/10.32615/ps.2019.009 (2019).

Pour-Aboughadareh, A. et al. Identification of high-yielding genotypes of barley in the warm regions of Iran. Plants 12, 3837. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants12223837 (2023).

Kowalczewski, P. Ł. et al. Influence of abiotic stress factors on the antioxidant properties and polyphenols profile composition of green barley (Hordeum vulgare L). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21020397 (2020).

Islam, M. Z. et al. Assessment of biochemical compounds and antioxidant enzyme activity in barley and wheatgrass under water-deficit condition. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 102, 1995–2002. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa%20.11538 (2022).

Piasecka, A. et al. Phenolic metabolites from barley in contribution to phenome in soil moisture deficit. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 6032. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21176032 (2020).

Kermani, S. G., Saeidi, G., Sabzalian, M. R. & Gianinetti, A. Drought stress influenced Sesamin and Sesamolin content and polyphenolic components in Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) populations with contrasting seed coat colors. Food Chem. 289, 360–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.03.004 (2019).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3 (1976).

Yousefzadeh Najafabadi, M. & Ehsanzadeh, P. Photosynthetic and antioxidative upregulation in drought-stressed Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) subjected to foliar-applied Salicylic acid. Photosynthetica 55, 611–622. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11099-017-0673-8 (2017).

Hemeda, H. M. & Klein, B. P. Effects of naturally occurring antioxidants on peroxidase activity of vegetable extracts. J. Food Sci. 55, 184–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.13652621.1990.tb06048.x (1990).

Nakano, Y. & Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant Cell Physiol. 22, 867–880. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a076232 (1981).

Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 105, 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(84)05016-3 (1984).

Kiani, R., Arzani, A. & Mirmohammady Maibody, S. A. M. Polyphenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity involved in salt tolerance in wheat, Aegilops cylindrica and their amphidiploids. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 646221. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.646221 (2021).

Brand-Williams, W., Cuvelier, M. E. & Berset, C. Use of free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 28, 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5 (1995).

Taulavuori, E., Hellstrom, E., Taulavuori, K. & Laine, K. Comparison of two methods used to analyse lipid peroxidation from Vaccinium myrtillus (L.) during snow removal, reacclimation and cold acclimation. J. Exp. Bot. 52, 2375–2380. https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/52.365.2375 (2001).

Velikova, V., Yordanov, I. & Edreva, A. J. P. S. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants: protective role of exogenous polyamines. Plant Sci. 151, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00197-1 (2000).

Roby, M. H., Sarhan, M. A., Selim, K. A. & Khalel, K. I. Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of essential oil and extracts of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare L.) and chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla L). Ind. Crops Prod. 44, 437–445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.10.012 (2013).

Li, X. J. et al. Abscisic acid pretreatment enhances salt tolerance of rice seedlings: proteomic evidence. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 1804, 929–940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbapap.2010.01.004 (2010).

Shindy, W. W. & Smith, O. E. Identification of plant hormones from cotton ovules. Plant Physiol. 55, 550–554. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.55.3.550 (1975).

Ma, Z. et al. Simultaneous analysis of different classes of phytohormones in coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) water using high-performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry after solid-phase extraction. Anal. Chim. Acta. 610, 274–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2008.01.045 (2008).