Abstract

Environmental contamination has grown to be a major issue for policymakers in recent years. This proposed study fills this void by presenting an empirical analysis that considers the effects of different green (hydropower, geothermal, solar, nuclear, and wind energy) and non-green (coal, oil, and gas) energy productions on ecological and carbon footprints. Fully Modified Ordinary Least Square is used to estimate the long-term associations among selected variables in the top ten nations that export electricity with data spanning 1990 to 2021. The findings demonstrate that geothermal and hydro energy production is expanding, which has raised ecological and carbon footprints. Additionally, it is discovered that the rise in energy production from nuclear, solar, and wind resources decreased the ecological and carbon footprints. In contrast, results show that oil production minimized environmental deterioration while coal and gas production increased it. This research also discovered that research and development (R&D) negatively correlated with ecological and carbon footprints within economies. These findings hold significant policy implications, particularly for nations aiming to modernize their green energy sectors. Promoting environmentally sustainable geothermal and hydropower technologies, alongside increased investment in R&D, emerges as a strategic pathway toward sustainable development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental degradation is accelerated by increased economic activities1. So, the development of economies is greatly influenced by the energy sectors, which is viewed as a crucial element of economic progress2. Green energy sources generally have lower environmental footprints compared to non-green sources, primarily due to reduced greenhouse gas emissions. In 2021, green energy sources including wind, solar, hydropower, and others provided 13.47% of the world’s energy. However, most sources of energy come from fossil fuels (coal, gas, and oil). In 2021, 82.28% of the world’s primary energy came from coal, oil, and gas, leading to an increase in habitat loss3. Therefore, a shift in the energy industry is necessary to protect the environment while limiting the effects on sustainable development.

Numerous scholars have attempted to compare how well non-green and green energies affect the environmental quality. Studies on green energy demonstrated ecologically sound behavior in some studies, while the opposite was demonstrated in others4,5,6. Lack of advanced technologies contributes significantly to the damaging effects of energy on the environment7. Green energy sources with great performance on the production side can combat environmental deterioration8,9. As a result, governments have been paying close attention to the expansion of green energy sources in order to reduce environmental devastation10,11. Switching from conventional to contemporary energy sources is the only feasible solution12. Production of green energy is crucial for environmental protection and social well-being13.

This study focused on the top ten electricity exporting countries, namely Germany, France, Switzerland, Spain, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Canada, Sweden, Norway, and Austria. In terms of value, the aforementioned ten countries exported 63.6% of the world’s electricity in 202114. France increased electricity exports by 235%, Spain increased by 328%, Belgium rose 495%, and Norway increased 543% since 202014. Various governments have established goals to reach financial prosperity but these have an impact on the environment, which can be crucial for achieving environmental sustainability15,16. Norway is one of the top ten countries that export electricity, and it has invested more in green energy than it has in coal, gas, and oil. In Norway, 0.46% of energy came from fossil fuels in 2021, compared to 71.56% from green sources. Climate specialists believe Norway will reach all its goals for limiting environmental damage by moving through with this investment in green energy generation. Similar to other major economies, the Czech Republic’s economy also contributes significantly to environmental devastation, with 6.50% of its energy coming from green resources and 50.13% from fossil fuels3. However, the Czech Republic has also established rules to produce green energy. So, the focus of world economies is moving toward the production of green energy, which has less of an influence on the environment17.

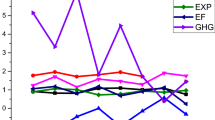

The energy landscape from 1990 to 2021 has shifted significantly in recent years, with a rising focus on green energy sources like solar, wind, and hydroelectric power, while non-green sources such as coal and oil continue to be used. Figure 1 depicts yearly developments in green and non-green energy production from 1990 to 2021, demonstrating a moderate but steady growth in green energy adoption. Despite this, non-green energy continues to dominate the total energy mix, highlighting this region’s unstable energy industry. Figure 1 shows Germany, Spain, and the Czech Republic produce more coal than other types of energy. While hydropower produces the most energy in Sweden, Austria, and Switzerland, nuclear energy produces the most energy in Belgium.

This research focuses on top ten electricity exporting countries because of three reasons: (i) Emissions intensity, electricity trade volume, and energy index demonstrate that electricity-exporting economies tend to have distinct structural characteristics, such as higher investment in cross-border transmission infrastructure, stronger technological capabilities in energy storage and grid management, and in many cases, lower emission intensities due to higher reliance on renewable sources; (ii) the chosen nations cover a wide variety of energy policy structure, from a significant dependence on nuclear and hydropower (e.g., France, Canada) to highly developed implementation of renewables (e.g., Norway, Sweden), as well as strong national grid linking (e.g., Germany and Switzerland). This range enables us to investigate how different energy techniques influence the ecological effects of power exports; (iii) the ecological intensity of producing electricity differs significantly across these nations. Norway for example, depends almost entirely on hydroelectricity, but Germany and the Czech Republic used to burn more fossil fuels. This diversity presents an important framework to analyze the ecological effects of energy trade; (iv) all chosen nations have access to outstanding continuous data for the required research variables. Data were gathered from credible worldwide databases produced by OECD, OWID, and Global Footprint.

Each green and non-green energy source does, however, bring distinct environmental difficulties that must be carefully considered. Therefore, researchers are now paying substantial attention to the association among economic expansion, green energy, and environmental destruction. Some experts have also attempted to investigate how environmental technology and eco-friendly environments are related. Hence, the environmental footprint impacts of various non-green and green energy production, and R&D has been widely ignored. Novelty of this study is how the inclusion of both ecological and carbon footprints adds to the existing literature. Using electricity-exporting countries offer a unique lens not explored in earlier studies. The novel integration of R&D with disaggregated energy sources (geothermal, nuclear, wind, etc.) The objective of this research is to examine the cumulative influences of geothermal, hydropower, nuclear, wind, and fossil fuel energy production on ecological footprint and carbon footprint in the top ten electricity exporting countries between 1990 and 2021, while accounting for research and development (R&D). Moreover, little to no research has ever attempted to combine R&D, technological advancement, and production-side energy in selected countries. Using R&D and technical innovation, a high level of environmental sustainability may be attained. Therefore, R&D has been included in this study as a crucial element that can reduce the ecological footprint by investing more in the energy production sector. Thus, it is assumed that R&D is substantially lowering the rate of environmental degradation in electricity exporter countries. The research questions that follow from the identified research gap are:

-

(i)

How do disaggregated green and non-green energy production influence ecological and carbon footprints in electricity-exporting countries?

-

(ii)

What is the role of R&D in mitigating environmental degradation across these countries?

-

(iii)

Are the impacts symmetric across countries with different energy portfolios?

The next Sect. 2 provides a literature review, dataset and methodology are presented in Sect. 3, discussion of results are in Sect. 4, and Sect. 5 contains conclusions and policy suggestions.

Review of previous studies

Both the advantages and disadvantages that energy consumption has on the environment have been pointed out in the literature. For instance, Sanli et al.,18 demonstrated that the long-term impacts of green and non-green energy sources on emissions are asymmetric. In OECD nations, environmental pollution is decreased by both positive and negative shocks related to green energy consumption, while it is significantly increased by asymmetric shocks related to non-green energy use. It is evident that increasing the supply of green energy reduces emissions. Green energy consumption, non-green energy consumption, employed labor force, and capital creation considerably contribute to long-term economic growth. Additionally, a study revealed that green energy consumption considerably lowers long-term carbon emissions compared to non-green energy consumption, which leads to a massive rise in long-term environmental pollution19.

Christoforidis & Katrakilidis20, for OECD economies, attempted to determine the connection between environmental pollution, green and non-green energy and discovered that green energy is an environmentally friendly indicator, obtaining a two-way causality among non-green energy and eco-system. According to Apergis et al.,21, hydropower energy consumption has a negative, unidirectional causal influence on environmental pollution over the long term. Natural gas and oil use have a favorable long and short-term effect on environmental pollution when it comes to non-green energy consumption. In the short term, coal usage reduces environmental pollution; but, over time, the effects are negative. In South Asia, commerce and the use of green energy sources short-term reduce environmental pollution, while long-term environmental pollution is increased by non-green energy use and economic expansion. While green energy consumption seems to cut environmental pollution, economic expansion, non-green energy consumption, trade, and urbanization all raised environmental pollution in East Asia over the medium and long term22. Solar and wind energy are negatively correlated with ecological footprint in India23,24, while solar energy have no significant effect on the environment25. Adebayou et al.,26 demonstrated that solar energy innovation, digitization, and globalization, has a detrimental impact on the ecological footprint, but natural resources have a beneficial effect. WQR analysis shows that renewable energy shrinks ecological footprint27.

In contrast, non-green energy consumption and commerce have a large and positive long-term influence on ecological footprints; FDI, green energy, and GDP have a negative and major impact on ecological footprints28. According to Zeraibi et al.,29 although technical advancement and increased green electricity generating capacity lower ecological footprints, economic expansion and increased financial development enhance them. Urbanization, aside from its impact on air pollution, is not particularly destructive to the environment. However, hydroelectricity has been shown to greatly lessen destruction of the environment. Zhang, Shah, & Yang30, discovered that rising environmental pollution is a result of higher hydropower and geothermal energy production. Furthermore, it is also revealed that energy production from nuclear and wind sources decreased the environmental pollution. In N11 countries’ energy consumption and trade has positive correlation with ecological footprints31. Biomass and coal contribute positively to economic growth, but natural gas appears to have a detrimental impact on economic growth32. Eweade et al.,24 established a unidirectional causal link between GDP, transportation energy use, renewable energy, globalization, and trade, and the ecological footprint. Economic growth and fossil fuel consumption lead to ecological degradation, while foreign direct investment improves environmental conditions33,34.

U. K. Pata & Kartal35 examined the effects of nuclear energy consumption on ecological footprints, load capacity factors, and carbon dioxide emissions. The results showed that nuclear energy improves environmental quality; green energy has negligible long-term environmental effects. With data for the European Union, Kuşkaya & Bilgili36 attempted to quantify the influences of wind energy on environment, and revealed a negative association among environmental deterioration and wind energy. Saidi & Omri37 studied the economies of the OECD and show the significant reduction in environmental deterioration brought on by upswing in nuclear energy production, but nuclear energy, geothermal, hydro, and wind energies come at a cost to the ecosystem. Similarly, Mahmood, Wang, & Zhang38 demonstrated the influence of nuclear energy on environment in Pakistan and discovered a decrease in environmental pollutants as a result of increased use of nuclear energy.

Utilizing green energy improves environmental quality whereas using non-green energy tends to worsen the environment39. Applying the Quantile Autoregressive Distributed Lag model40, demonstrated that the generation of power from nuclear, oil, and coal had a positive relationship with environmental pollution. The results also showed a significant correlation between environmental pollution and energy consumption. Yu et al.,41 elaborated how the use of natural resources and green energy affects the recovery of the green economy in the top ten countries using non-green energy. It concluded that the development of natural resources has the potential to play a major role in promoting the green economy. Furthermore, according to Bilgili et al.,42 geothermal energy usage significantly contributes to environmental deterioration in the United States. Hassan, Baloch, & Tarar43, found a substantial decrease in environmental degradation caused by nuclear power in BRICS economies.

-

a.

S. K. Pata & Pata44 investigated the impact of disaggregated renewable energy sources (hydropower, solar, wind, and biofuel) on the load capacity factor and sustainable development in the United States. The findings indicate that biofuel, solar, and wind are effective contributions to sustainable development. Furthermore, hydropower has little impact on sustainable development. Özkan, Alola, & Eluwole45 discovered that in the long run nuclear energy enhancement and constitutional changes both boost the quality of the environment by raising the country’s ratio of biocapacity over its ecological footprint. Nuclear energy and energy storage are substantially associated with a decrease in CO2 emissions, but natural resources and oil usage increase the amount of CO2 emissions. The impacts of nuclear energy, energy storage innovation, oil consumption, and natural resources are varied, resulting in an uneven pattern over the quantile distribution46. Bekun, Gyamfi, Bamidele, & Udemba47 indicated that a rise in renewable energy, transportation energy consumption, and globalization are associated with a decline in environmental pollution. Eweade, Joof, & Adebayo48 Indicated that biomass and coal contribute positively to economic growth, but natural gas appears to have a negative impact on economic growth.

-

b.

U. K. Pata, Kartal, Erdogan, & Sarkodie49 studied how R&D spending on nuclear energy and green energy affects the environment and concludes that nuclear energy-related R&D spending has no positive environmental effects as well as R&D spending on green energy lowers CO2 emissions. Prokopenko et al.,50 demonstrated how expenditures and investments in R&D had a favorable impact on a company’s profitability metrics, including net income, return on investment, and profits before tax and interest. According to Uyar, Kuzey, Gerged, & Karaman51, R&D intensity of energy companies encourages eco-friendly behaviors in three areas: reduction of resource use, eco-innovation, and decrease of emissions. Moreover, moderation research showed that while the relationship between R&D intensity and eco-innovation adds value, it does not when it comes to reducing resource use and emissions. Meng, Fan, Huang, & He52 examined the effects of energy R&D, financial inclusion, financial risk index, the political-economic- and energy-related inflation on the energy efficiency of the G7 economies between 2004 and 2020. The results showed that all the factors taken into consideration had a positive impact on the region’s energy efficiency. Ecological innovations, green energy sources, and environmental taxation have a negative impacts on PM2.5 and carbon emissions53. Energy efficiency benefits greatly from a positive shock to research and development investment on green energy sources in the short and long term. There is no substantial evidence that a surge in R&D investment in both nuclear and fossil energy portfolios offers energy efficiency improvement, as would be expected given the associated costs and environmental concerns54. The study revealed that the confluence of R&D intensity, environmental regulation, and energy consumption is a contributing factor to the rise in carbon emissions observed in various regions of China55. The relationship between technical innovation and quality governance, research and development and quality governance, and industrialization and quality governance all reduce carbon emissions56.

The primary goal of this research is to investigate the relationship between green/non-green energy production and the carbon footprint in the top ten electricity export countries, employing FMOLS. While prior research has investigated energy-environment linkages, they mainly concentrated on either green or non-green energy alone or lacked geographical specificity. In contrast, this research provides a comparative assessment of each of the energy forms within a single statistical framework, utilizing current and detailed data unique to 1990 to 2021. By doing so, the article adds to a deeper awareness of the energy transition procedure while offering context-dependent policy suggestions which currently lack in the research.

Material & methods

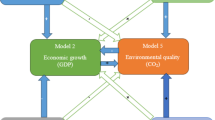

Researchers found discrepancies in the research that has ignored the production side of green and non-green energy. To close the aforesaid gap, data from the ten electricity exporting countries was obtained for an empirical assessment from 1990 to 2021. The impact of separate green and non-green energy production, as well as R&D on carbon and ecological footprints, are the focus of this research. Data for R&D is derived from the57 OECD database. Moreover, environmental footprint data is taken from the global footprint network58 and data for various non-green energy production (oil, coal, and gas) and green energy production (nuclear, hydro power, solar, geothermal, and wind energy) is taken from Our World in Data3. Table 1 explains the variables’ definitions. Figure 2 explain conceptual framework.

Natural resources are used to produce energy in economies that follow the pattern of electricity-exporting nations. Such a move led to an increase in the trend of environmental deterioration. However, in recent decades, these nations have changed the way they consume energy to promote green sources. However, these energies have a significant effect on environmental degradation. Regardless of whether all economies use green energy, the issue of environmental degradation persists. Therefore, it is crucial to understand why this issue has not yet been solved. As a result, the production of green and non-green energies regarding R&D is the main topic of this research. The model is expressed as:

ECP signifies ecological footprint; REP is for green energy production, which includes solar, hydropower, nuclear, geothermal, and wind energy; NREP is for non-green energy production, which includes oil, coal, and gas; and R&D is research & development. Equation (1) may be modified as follows:

All variables are transformed into natural logarithms before the model is estimated in order to standardize the data and produce more accurate estimates by supporting the evaluation of the regression coefficient elasticity. As a result, Eq. (2)’s panel log-linear econometric functions may now be written as:

The dependent variable ECP indicates ecological footprint, and the explanatory variables HPP, GTP, NEP, SEP, WEP, OP, CP, GP, and R&D signify hydro-power production, geothermal energy production, nuclear energy production, solar energy production, oil production, coal production, gas production, and research & development. The factors a1 to a9 are the long-run coefficients of variables HPP, GTP, NEP, SEP, WEP, OP, CP, GP, and R&D, while a0 represents the interception term. i signifies the number of countries (1–10), t indicates the research period (1990–2021), and ε represents the normally distributed error term.

For robustness checks using Eq. (4) below, this research explores the impacts of given variables on carbon footprint (CFP) as additional proxies of environmental degradation:

These nations’ common economic and industrial traits could lead to cross-sectional dependence. So, when employing panel data sets, it is crucial to consider the risk of cross-sectional dependence. Four tests—the Pesaran CD test59, Breusch and Pagan LM test60, Pesaran LM test59, and Baltagi, Feng, and Kao LM test61 - have been commonly employed to confirm cross-sectional dependency.

The following approach was presented to examine Breusch & Pagan cross-sectional dependence:

Where, cross-sectional dependency is indicated by \(\:{CD}_{BP}\), \(\:{\widehat{P}}_{LK}^{2}\) indicated the pairwise cross-sectional residuals, and n represents panel’s cross-sectional dimensions.

Where, \(\:{CD}_{LM}\) is the cross-sectional dependency of Pesaran, n denotes cross-sectional measurements of the panel.

Baltagi, Feng, and Kao61 propose the following basic empirical bias modifications for scaled LM test statistics:

Where, cross-sectional dependency is denoted by CD, pairwise cross-sectional correlation is indicated with \(\:{\widehat{P}}_{LK}^{2}\), n represents the cross-sectional dimensions of the panel, and T denotes time period.

IPS62, Breitung63, LLC64 are used in this analysis to determine whether the variables were stationary.

Breitung contemplates the given equation:

However, the alternative hypothesis states that this panel series is stationary. By using the modified vectors below, Breitung (2001)63 uses them. \(\:{Yi}^{*}=Ayi=[{Yit}^{*}.....{YiT}^{*}\:and\:{Z1}^{*}=Azi={ziT}^{*}]\:\)to hypothesis the following test.

Levin et al. (2002)64 equation is as follows:

Where mean and standard deviation adjustment factors are given by \(\:\mu\:\dot{t}\:and\:\sigma\:\dot{t}\). \(\:{\widehat{S}}_{n}\) is equal to (1/n) \(\:\sum\:_{i=1}^{n}{\widehat{\sigma\:}}_{yi}/{\widehat{\sigma\:}}_{\epsilon\:j},\:\)where for the country i, \(\:{\widehat{\sigma\:}}_{yi}\) specifies estimator of long run.

IPS62 proposed the t-bar check by using following Eq.

Where panel dimension is shown by n, \(\:{T}_{a}\) denotes the cross-sectional unit’s normal of the different ADF t- statistics, both with and without a trend, \(\:{k}_{t}\:and\:{v}_{t}\) provide estimations of the mean and variance of each \(\:{t}_{ai}\) statistics.

The cross-sectional augmented Dickey-Fuller (CADF) regression used by Pesaran65 is as follows:

Whereas the cross-sectional averages and primary differences are showed by \(\:{\stackrel{-}{y}}_{t-1}\) and \(\:\varDelta\:{\stackrel{-}{y}}_{it-1}\), individually. The cross-sectionally augmented created the following CADF statistics62.

This research used both first- and second-generation unit root tests because first-generation tests assume cross-sectional independence, which may not hold given the potential spillover effects and interconnectedness among the selected countries, especially in global electricity trade. Therefore, second-generation tests, which account for cross-sectional dependence, are included to complement and validate the findings. This dual approach enhances the reliability of our inference regarding the order of integration.

The following step is to determine Pedroni’s co-integration based on residuals:

Where W and Y is order one level integration. If allowed, one may set the individual and temporal effects’ respective parameters, \(\:{\alpha\:}_{i}\:\)and \(\:{\beta\:}_{i}\) set to zero.

Pedroni employs the panel data cointegration system described below:

Where Z and X are level of order one and \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{it}\) is residual.

Afterwards, this study employed the FMOLS estimate to examine the long-term connection among the selected variables after validating the co-integration of the variables. The FMOLS panel provides a number of benefits. It supports serial correlation, heterogeneity, and endogeneity. It also offers suggestions for both within and between dimensions. The following equation is used to find the distance between the dimensions:

Where, \(\:{\widehat{Z}}_{it}={N}^{-1}\sum\:_{i=1}^{N}{Z}_{FMi}\times\:{Z}_{FMi}\:\)is the FMOLS estimator for different variable.

The heterogeneous panel causality test is checked as the final stage66. In panel data, the following model determines causality:

Where \(\:{\tau\:}_{i}^{J}\) is the auto-regressive parameter, t, j is the lag length, \(\:{X}_{i,\:\:t}\) and \(\:{Z}_{i,\:\:t}\) are the observations of two stationary variables for nation i, and regression coefficient is represented by \(\:{\beta\:}_{i}^{J}\) that changes across groups.

Results and discussion

Figure 3 shows descriptive statistical analysis. The mean (median) values of the ecological footprint (ECP), hydro-power production (HPP), geothermal energy production (GTP), solar energy production (SP), nuclear energy production (NP), wind energy production (WP), coal production (CP), gas production (GP), oil production (OP), and research and development (R&D) are 1.783 (1.762), 3.204 (3.614), 0.909 (1.020), -2.412 (-3.352), 4.189 (4.109), -0.275 (-0.056), 4.276 (4.814), 3.422 (3.071), 3.958 (3.343), and 0.667 (0.691) respectively. Figure 1 explains the trend of energies.

Figure 4 explains data for ecological footprint, carbon footprint, and bio capacity in global hectors per capita. Sweden, Norway, and Canada have greater bio capacity than they do ecological and carbon footprints.

The estimated procedure may provide inaccurate and biased results if cross sectional dependency is not considered. As a result, CD tests were conducted for this investigation, and the results are shown in Table 2. Cross-sectional dependence was discovered in the data. The results of the first-generation unit root test might be skewed and deceptive in the existence of cross-sectional dependence. In order to overcome the problem of cross-sectional dependency, this discovery compels us to utilize a different unit root test strategy, namely the second-generation unit root analysis devised by65, also recognized as the CADF and CIPS.

Table 3 summarizes the results of the Breitung, LLC, CIPS, and CADF panel unit root tests. Results indicate that all variables are integrated at the first difference. These results call for more effective methods than those used in this research.

This research executed the Pedroni & Kao panel co-integration tests after performing the second-generation panel unit root test to produce the intended results. Using67,68,69 panel co-integration tests, this study examines all potential long-term associations among dependent and independent variables. The results of the panel co-integration tests are displayed in Table 4. The results of the panel co-integration tests are displayed in Table 4. The long-term co-integration of the variables is demonstrated by the Pedroni test, where four out of the seven estimates are significant at 1%, and the Kao Co-integration test has a significant level of 1%. This suggests that the null hypothesis H0 of no co-integration be rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis H1 of co-integration among the variables.

Therefore, because of co-integration, we must proceed using panel fully modified ordinary least square (FMOLS) long-term estimators. For a better understanding of environmental variables, we used carbon footprint variables for robust results. The FMOLS estimates for ECP and CFP show that all of the long-run coefficients of the examined variables are statistically significant at a 1% level of significance (Table 5).

All nations’ primary energy source is hydropower. Depending on the provided hydropower production coefficients, such a form of energy increases environmental pollution in the panel countries, Germany, Sweden, and Norway. Using FMOLS, a 1% growth in hydropower output cause a rise in ecological and carbon footprints of 0.10% and 0.03% for the panel group, 0.03% and 0.04% for Germany, 0.21% and 0.02% for Sweden, and 0.14% and 0.282% for Norway, respectively. Hydro power is thus yet another element contributing to the deterioration of the environment. This result is consistent with that of Zhang et al.,30. They discovered that the production of hydropower increases the environmental impact of a panel of the E5 economies. According to Table 5, hydropower generation increases environmental sustainability by reducing ecological impact in Canada, France, Switzerland, Spain, Belgium, Czech Republic, and Austria. As a result, it’s important to concentrate on power generation initiatives to safeguard the environment. These results are same as Adebayo et al.,70 and Xu et al.,71. The government’s capacity to monitor hydro energy output to stop environmental damage is, however, severely constrained.

Regarding the production of nuclear energy, an interesting conclusion has been reached. Nuclear energy’s coefficient value indicates that it is negatively correlated with the ecological footprint, which suggests that a 1% increase in nuclear energy would result in a 0.085% and 0.0098% decrease in the ecological footprint and carbon footprint, respectively, in the panel nations. As a result, the generation of nuclear energy might be seen as a measure of low carbon footprint. The results of tests indicate that nuclear energy production may be required as a replacement for other sources of energy to ensure a healthier environment. As a result, it is concluded that the reduction in environmental pollution is greatly supported by the green energy generated by nuclear energy sources. Even though nuclear energy is a clean energy source, its sustainability relies on the manufacturing method used. This finding is in line with the case study of72,73.

In the panel group, Canada, France, Germany, Switzerland, Spain, Belgium, Czech Republic, Sweden, Norway, and Austria, wind energy has a negative correlation with environmental degradation. This research concludes that a 1% increase in wind energy production would result in 0.185% and 0.289% decreases in ecological and carbon footprints, respectively. Likewise, solar energy production has an inverse association with environmental deterioration in all countries. Our study concluded that a 1% increase in solar energy production minimizes ecological and carbon footprints by 0.043% and 0.044%, respectively. The conclusion demonstrates that the generation of wind and solar energy is a green indicator. A frequently used method to quantify the reduction in environmental pollution is the method that wind, and solar energy output are now responding to environmental protection. To protect the environment globally, wind energy and solar energy have therefore replaced the majority of filthy technologies. Wind and solar energy production in response to the current situation is much appreciated, but not in the long run, as most of the nations’ energy mix decarbonizes more and more because of energy and climate change. As a result, for these countries, the use of energy from wind sources is highly recommended. Our findings back up74,75.

In the panel group of countries, including Canada, Spain, Belgium, and Norway, geothermal energy generation is considered as another indicator of environmental deterioration. The fact that the geothermal energy production coefficients are strongly correlated with ecological and carbon footprints suggests that geothermal energy generation degrades the ecosystem. The ecological and carbon footprints would grow by 0.026% and 0.160%, respectively, with every 1% increase in geothermal energy output. Therefore, despite adopting green energy sources, our study’s main issue is why governments are incapable of establishing a sustainable environment. The production of green energy from non-green sources and the resulting environmental harm are hence the key obstacles to this. When geothermal energy is produced, its pollution affects human beings, which is consistent with Bashir et al.,76. When geothermal energy facilities are being built and steam rises from well-drilling equipment, noise may be a concern. The geothermal energy equipment, including fluid flow, pumps, transportation, fans, turbines, the Collin tower, and generators, are the major causes of this problem77. High-pressure steam is emitted during this operation that also contributes to serious noise problems78. One other negative effect of geothermal energy production on the environment is that of geothermal fluid. It cannot be used since it comprises a mixture of several substances that are hazardous to the environment. The fluid in the process should ideally be returned to the ground, but owing to technological and financial challenges, this cycle is broken, and it is dumped into the deep ocean instead. Additionally, because of the operation of geothermal energy plants during this process, certain gases are emitted, contaminating the surface water and soil with rain. As a result, geothermal energy plants produce a lot of solid waste, which raises ecological threats77. These findings are same as79. Geothermal energy, according to80, is sustainable since water is injected back into the ground after serving its main purpose and no extra fuel is needed to create electricity.

Moreover, coal and gas production are other indicators of environmental degradation. This research found the conclusion that a 1% increase in coal and gas production boosts the ecological footprint by 0.119% and 0.065%, respectively, these findings are consistent with Adebayo et al.,81,82. While oil production is negatively correlated with ecological and carbon footprint in the panel group, Canada, Germany, and Spain. Hence, in Spain and Germany, production of oil effects on the environment are not significant as83.

Finally, R&D has been utilized in this study and it prevents environmental degradation. It demonstrates that a 1% increase in R&D will reduce ecological and carbon footprint in the panel group by 0.084% and 0.075%, respectively. This result is in line with53,84. R&D is negatively correlated with environmental degradation in all countries. In order to secure the use of clean energies, a rise in R&D in the energy industry gives concerned economies a significant advantage. Such activity increases the biosphere’s capacity for sustainability and, more crucially, encourages the production of green energy, which further slows down destruction of the environment.

Considering that the FMOLS do not explain the causal connection between variables, The D-H panel causality test was used in this research to ascertain the causality between chosen variables in Fig. 5; Table 6. Additionally, given cross-sectional dependency and heterogeneity, the D-H panel causality analysis seems to be more suitable than that of the conventional one. In Table 6, the results of the D-H panel causality test are shown. The D-H test identifies a bidirectional causality between wind energy production, R&D, and ecological footprint, suggesting that these variables influence each other over time. This implies that, in some countries, wind energy and R&D have contributed to mitigating ecological degradation, while environmental conditions also feedback into energy innovation and deployment decisions. Similar two-way causal linkages are observed between the development of geothermal energy and wind, nuclear, and solar energy, as well as between R&D and geothermal energy, indicating dynamic and interdependent relationships among advanced energy technologies.

In contrast, unidirectional causality is found from several energy sources to ecological footprints. Specifically, increases in geothermal, hydropower, nuclear, and solar energy production, as well as oil and coal output, all lead to changes in ecological footprint without reverse causality. These one-way relationships imply that environmental degradation in these cases is primarily driven by energy production, not vice versa.

These causality results deepen our understanding of how different forms of energy and innovation interact with environmental outcomes, and they underscore the need for context-sensitive policies that recognize both direct and feedback effects across countries.

Conclusion and future policy implications

At the expense of environmental devastation, advanced economies significantly contribute to global economic development. No study has been done on electricity exporter economies to assess the impact on the ecological footprint through taking production-side green and non-green energies into consideration with R&D. To get more reliable results, this study employs panel dynamic FMOLS, which is beneficial for heterogeneity, cross-sectional dependence, and endogeneity. As a result, this research examines the multiple effects of production-side green energies (hydropower, solar, nuclear, wind, and geothermal energy), non-green energies (coal, gas, and oil), and R&D on the environmental footprints in the top ten electricity exporting nations for the period of 1990–2021. To examine the integration of data, the current study utilized diagnostic checks such as cross-sectional dependence and second-generation unit root tests. The long-term co-integration has been examined using the Pedroni and Kao tests. The results confirmed that the dataset is appropriate for FMOLS to investigate the long-term correlation amongst some of the relevant variables. Utilizing both criteria—ecological and carbon footprint—the results are identical to one another. Geothermal and hydro energy generation have a positive and significant relationship with ecological degradation in selected countries. It demonstrates that both kinds of energy generation still employ outdated methods that pollute the environment. In contrast, the generation of wind and nuclear energy has a negative relationship with environmental hazards. It implies that if additional energy is produced from nuclear, solar, and wind energy sources in particular countries, the rate of environmental deterioration may be reduced. Finally, the effects of R&D on environmental deterioration are detrimental and statistically significant. It implies that the administration’s focus related to R&D should be on green initiatives like green energy that eventually lead to a reduction in environmental pollution.

To acquire a more comprehensive understanding of the consequences of measures of ecological footprint in selected economies, the study also included some policy recommendations. Non-green energy production and ecological deterioration are positively correlated, suggesting that top ten electricity exporting countries are harming the environment more. As a result, using conventional energy at the targeted output level will result in increased environmental harm85. Additionally, public-private cooperation is required to raise awareness of the natural ecosystem and how individuals may protect it via everyday economic activity. It is necessary to switch from conventional patterns of geothermal and hydroelectric energy generation to more sophisticated ones since these sources of power contribute to ecological harm. Compared to solar, nuclear, and wind power technologies, the ecosystem is valued highly for meeting peak energy demand. Once developed, that type of energy can also provide cheaper energy than that produced by non-green energy sources. It acts as a source of green energy. Further, the hydro production line needs to be examined, and the expense of damage to the environment should be kept to a minimum. Consequently, the rate of environmental degradation will decline because it has a smaller environmental impact. Therefore, these economies must increase their investment in the generation of nuclear, solar, and wind energy. The generation of energy necessitates close attention to safety issues, even though nuclear energy has minimal environmental consequences. Accordingly, to prevent an unintended disaster that might affect the environment, government officials should control the management of radioactive waste and nuclear plants. By taking the ecological footprint into account as an explicated variable, wind energy also exhibits characteristics of a source of clean energy. Finally, the outcomes of this research highlight the necessity for varied R&D plans for the top power exporting countries, according to their present energy portfolios and the environmental implications found in our analysis. While geothermal and hydropower production are renewable sources, their development has been linked to higher ecological and carbon footprints, most likely due to obsolete infrastructure, inefficient land-use practices, and environmental externalities. Therefore, these sources should emphasize R&D expenditures in geothermal and hydropower technology to avoid environmental impact and improve sustainability. On the contrary, this research also discovers that nuclear, solar, and wind energy help to reduce environmental deterioration, emphasizing the need for ongoing R&D assistance to grow these cleaner technologies.

Future studies in the area should focus on various countries with various determinants of environmental degradation, such as eco-innovation and financial development, with stratified green and non-green energy production in order to verify the relevance of obtained results and the reaction of different indicators towards degradation of the environment. Due to its long-term cost reduction, eco-innovation has enormous promise in several economies. There is a possibility that certain technologies could contribute significantly to the creation of green energy and result in a decrease in environmental degradation.

Data availability

Data will be available from corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adebayo, T. S. & Kirikkaleli, D. Impact of renewable energy consumption, globalization, and technological innovation on environmental degradation in japan: application of wavelet tools. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 23 (11), 16057–16082 (2021).

Baloch, M. A. et al. Modeling the dynamic linkage between financial development, energy innovation, and environmental quality: does globalization matter? Bus. Strategy Environ. 30 (1), 176–184 (2021).

OWID, Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/, (2022).

Shao, X. et al. Modeling the effect of green technology innovation and renewable energy on carbon neutrality in N-11 countries? Evidence from advance panel estimations. J. Environ. Manage. 296, 113189 (2021).

Sun, H. et al. Evaluating the environmental effects of economic openness: evidence from SAARC countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26 (24), 24542–24551 (2019).

Tariq, G. et al. Energy consumption and economic growth: evidence from four developing countries. Am. J. Multidisciplinary Res., 7(1). (2018).

Yasmeen, R. et al. Exploring the role of biomass energy consumption, ecological footprint through FDI and technological innovation in B&R economies: A simultaneous equation approach. Energy 244, 122703 (2022).

Tariq, G., Sun, H. & Ali, S. Environmental footprint impacts of green energies, green energy finance and green governance in G7 countries. Carbon Footprints. 3, 5 (2024).

Tariq, G., Ding, G. & Hussain, M. A. Pathways to carbon neutrality: the impact of hydropower, nuclear energy, economic complexity, financial development, and Eco-Innovation. Environ. Qual. Manage. 34 (3), e70038 (2025).

Sun, Y. et al. Transition towards ecological sustainability through fiscal decentralization, renewable energy and green investment in OECD countries. Renew. Energy. 190, 385–395 (2022).

Saqib, N. Green energy, non-renewable energy, financial development and economic growth with carbon footprint: heterogeneous panel evidence from cross-country. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 1–20. (2022).

Nouri, A. et al. Identification of gaps and barriers in regulations, standards, and network codes to energy citizen participation in the energy transition. Energies 15 (3), 856 (2022).

Olabi, A. & Abdelkareem, M. A. Renewable energy and climate change. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 158, 112111 (2022).

WTE. World Top exports. (2022). https://www.worldstopexports.com/electricity-exports-country/.

Sarkodie, S. A. et al. Energy–climate–economy–population nexus: an empirical analysis in kenya, senegal, and Eswatini. Sustainability 12 (15), 6202 (2020).

Sun, H. et al. Nexus between environmental infrastructure and transnational cluster in one belt one road countries: role of governance. Bus. Strategy Dev. 1 (1), 17–30 (2018).

Aized, T. et al. Energy security and renewable energy policy analysis of Pakistan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 84, 155–169 (2018).

Sanli, D. et al. The asymmetric effect of renewable and non-renewable energy on carbon emissions in OECD: new evidence from non-linear panel ARDL model. Front. Environ. Sci. 11, 1228296 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. A dynamic relationship between renewable energy consumption, non-renewable energy consumption, economic growth and CO2 emissions: evidence from Asian emerging economies. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 2721 (2023).

Christoforidis, T. & Katrakilidis, C. T28he Dynamic Role of Institutional Quality, Renewable and non-renewable Energy on the Ecological Footprint of OECD Countries: Do Institutions and Renewables Function as Leverage Points for Environmental Sustainability?? 53888–53907 (Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2021).

Apergis, N. et al. Investigating the association among CO2 emissions, renewable and non-renewable energy consumption in uzbekistan: an ARDL approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (14), 39666–39679 (2023).

Amin, N. & Song, H. The Role of Renewable, non-renewable Energy Consumption, Trade, Economic Growth, and Urbanization in Achieving Carbon Neutrality: A Comparative Study for South and East Asian Countries30. 12798–12812 (Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2023).

Karlilar, S. & Emir, F. Exploring the role of coal consumption, solar, and wind power generation on ecological footprint: evidence from India using fourier ADL cointegration test. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (9), 24077–24087 (2023).

Eweade, B. S., Güngör, H. & Karlilar, S. The Determinants of Ecological Footprint in the UK: the Role of Transportation Activities, Renewable Energy, Trade Openness, and Globalization 30 122153–122164 (Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2023).

Pata, U. K. & Kartal, M. T. Testing the ecological effect of wind and solar energy consumption: A novel regularized common correlated effect approach for top oil-importing countries. in Natural Resources Forum. (Wiley Online Library, 2024).

Adebayo, T. S. et al. Analyzing the effects of solar energy innovations, digitalization, and economic globalization on environmental quality in the united States. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy. 26 (12), 4157–4176 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Transforming Costa rica’s environmental quality: the role of renewable energy, rule of law, corruption control, and foreign direct investment in Building a sustainable future. Renew. Energy. 239, 121993 (2025).

Roy, A. The impact of foreign direct investment, renewable and non-renewable energy consumption, and natural resources on ecological footprint: an Indian perspective. Int. J. Energy Sect. Manage., (2023).

Zeraibi, A., Balsalobre-Lorente, D. & Murshed, M. The influences of renewable electricity generation, technological innovation, financial development, and economic growth on ecological footprints in ASEAN-5 countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28 (37), 51003–51021 (2021).

Zhang, Q., Shah, S. A. R. & Yang, L. Modeling the effect of disaggregated renewable energies on ecological footprint in E5 economies: do economic growth and R&D matter? Appl. Energy. 310, 118522 (2022).

Nathaniel, S. P., Murshed, M. & Bassim, M. The nexus between economic growth, energy use, international trade and ecological footprints: the role of environmental regulations in N11 countries. Energy Ecol. Environ. 6 (6), 496–512 (2021).

Eweade, B. S., Joof, F. & Adebayo, T. S. Analyzing India’s coal, natural gas, and biomass energy consumption: Evidence from a Fourier technique to promote sustainable development. in Natural resources forum (Wiley Online Library, 2025).

Eweade, B. S. et al. Examining the asymmetric effects of fossil fuel consumption, foreign direct investment, and globalization on ecological footprint in M Exico. Sustain. Dev. 32 (4), 2899–2909 (2024).

Tariq, G., Sun, H. & Ali, S. Environmental footprint impacts of green energies, green energy finance and green governance in G7 countries. Carbon Footprints, 3(1), N/A-N/A. (2024).

Pata, U. K. & Kartal, M. T. Impact of nuclear and renewable energy sources on environment quality: testing the EKC and LCC hypotheses for South Korea. Nuclear Eng. Technol. 55 (2), 587–594 (2023).

Kuşkaya, S. & Bilgili, F. The wind energy-greenhouse gas nexus: the wavelet-partial wavelet coherence model approach. J. Clean. Prod. 245, 118872 (2020).

Saidi, K. & Omri, A. Reducing CO2 emissions in OECD countries: do renewable and nuclear energy matter? Prog. Nucl. Energy. 126, 103425 (2020).

Mahmood, N., Wang, Z. & Zhang, B. The role of nuclear energy in the correction of environmental pollution: evidence from Pakistan. Nuclear Eng. Technol. 52 (6), 1327–1333 (2020).

Fakher, H. A. et al. Renewable energy, nonrenewable energy, and environmental quality nexus: an investigation of the N-shaped environmental Kuznets curve based on six environmental indicators. Energy 263, 125660 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. The Impact of non-renewable Energy Production and Energy Usage on Carbon Emissions: Evidence from China 0958305X221150432 (Energy & Environment, 2023).

Yu, C. et al. Impact of non-renewable energy and natural resources on economic recovery: empirical evidence from selected developing economies. Resour. Policy. 80, 103221 (2023).

Bilgili, F. et al. The co-movements between geothermal energy usage and CO2 emissions through high and low frequency cycles. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28 (45), 63723–63738 (2021).

Hassan, S. T., Baloch, M. A. & Tarar, Z. H. Is nuclear energy a better alternative for mitigating CO2 emissions in BRICS countries? An empirical analysis. Nuclear Eng. Technol. 52 (12), 2969–2974 (2020).

Pata, S. K. & Pata, U. K. Comparative analysis of the impacts of solar, wind, biofuels and hydropower on load capacity factor and sustainable development index. Energy, 134991. (2025).

Özkan, O., Alola, A. A. & Eluwole, K. K. Dynamic Environmental Quality Effect of Nuclear Energy Intensity, Structural Changes, and Natural Resources in Pakistan: Testing Load Capacity Factor Hypothesis Evidence 1–18 (Environment, 2024).

Usman, O., Ozkan, O. & Ike, G. N. Global evidence of multi-dimensional asymmetric effect of energy storage innovations on environmental quality: delineating the role of natural resources, nuclear energy and oil consumption. J. Clean. Prod. 451, 142070 (2024).

Bekun, F. V. et al. Tourism-induced emission in Sub-Saharan africa: A panel study for oil-producing and non-oil-producing countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29 (27), 41725–41741 (2022).

Eweade, B. S., Joof, F. & Adebayo, T. S. Analyzing India’s coal, natural gas, and biomass energy consumption: Evidence from a Fourier technique to promote sustainable development. in Natural resources forum (Wiley Online Library, 2024).

Pata, U. K. et al. The role of renewable and nuclear energy R&D expenditures and income on environmental quality in germany: scrutinizing the EKC and LCC hypotheses with smooth structural changes. Appl. Energy. 342, 121138 (2023).

Prokopenko, O. et al. Impact of investments and R&D costs in renewable energy technologies on companies’ profitability indicators: assessment and forecast. Energies 16 (3), 1021 (2023).

Uyar, A. et al. Research and development intensity, environmental performance, and firm value: unraveling the nexus in the energy sector worldwide. Bus. Strategy Environ. 32 (4), 1582–1602 (2023).

Meng, G. et al. Research methods on the role of financial inclusion, energy efficiency and energy R&D: evidence from G7 economies. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja. 36 (2), 2106508 (2023).

Li, P. et al. Do environmental taxes reduce air pollution? Evidence from fossil-fuel power plants in China. J. Environ. Manage. 295, 113112 (2021).

Obekpa, H. O. & Alola, A. A. Asymmetric response of energy efficiency to research and development spending in renewables and nuclear energy usage in the united States. Prog. Nucl. Energy. 156, 104522 (2023).

Dabuo, F. T. et al. Influence of research and development, environmental regulation, and consumption of energy on CO2 emissions in China—novel Spatial Durbin model perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (11), 29065–29085 (2023).

Baba Ali, E. et al. The role of technology innovation, R&D, and quality governance in pollution mitigation for EU economies: fresh evidence from method of moment quantile regression. Int. J. Sustainable Dev. World Ecol. 30 (3), 244–261 (2023).

OECD (2022). https://data.oecd.org/.

GFN. Global footprint network. (2022). https://data.footprintnetwork.org/#/.

Pesaran, M. H. General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels (IZA Discussion Paper No. 1240). Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), (2004).

Breusch, T. S. & Pagan, A. R. The Lagrange multiplier test and its applications to model specification in econometrics. Rev. Econ. Stud. 47 (1), 239–253 (1980).

Baltagi, B. H., Feng, Q. & Kao, C. A Lagrange multiplier test for cross-sectional dependence in a fixed effects panel data model. J. Econ. 170 (1), 164–177 (2012).

Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H. & Shin, Y. Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J. Econ. 115 (1), 53–74 (2003).

Breitung, J. The Local Power of some Unit Root Tests for Panel Data (Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2001).

Levin, A., Lin, C. F. & Chu, C. S. J. Unit root tests in panel data: asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J. Econ. 108 (1), 1–24 (2002).

Pesaran, M. H. A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. J. Appl. Econom. 22 (2), 265–312 (2007).

Dumitrescu, E. I. & Hurlin, C. Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ. Model. 29 (4), 1450–1460 (2012).

Pedroni, P. Critical values for cointegration tests in heterogeneous panels with multiple regressors. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 61 (S1), 653–670 (1999).

Pedroni, P. Panel cointegration: asymptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series tests with an application to the PPP hypothesis. Econom. Theory. 20 (3), 597–625 (2004).

Kao, C. Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. J. Econ. 90 (1), 1–44 (1999).

Adebayo, T. S., Kartal, M. T. & Ullah, S. Role of hydroelectricity and natural gas consumption on environmental sustainability in the united states: evidence from novel time-frequency approaches. J. Environ. Manage. 328, 116987 (2023).

Xu, R. et al. A global-scale framework for hydropower development incorporating strict environmental constraints. Nat. Water. 1 (1), 113–122 (2023).

Sarkodie, S. A. & Adams, S. Renewable energy, nuclear energy, and environmental pollution: accounting for political institutional quality in South Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 643, 1590–1601 (2018).

Lau, L. S. et al. Is nuclear energy clean? Revisit of environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis in OECD countries. Econ. Model. 77, 12–20 (2019).

Hernández, C. V., González, J. S. & Fernández-Blanco, R. New method to assess the long-term role of wind energy generation in reduction of CO2 emissions–case study of the European union. J. Clean. Prod. 207, 1099–1111 (2019).

Hussain, B. et al. Effect of wind and solar energy production, and economic development on the environmental quality: is this the solution to climate change? Gondwana Res. 119, 27–44 (2023).

Bashir, M. A. et al. Does geothermal energy and natural resources affect environmental sustainability? Evidence in the lens of sustainable development. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (8), 21769–21780 (2023).

Bošnjaković, M., Stojkov, M. & Jurjević, M. Environmental impact of geothermal power plants. Tehnički Vjesn. 26 (5), 1515–1522 (2019).

Kristmannsdóttir, H. & Ármannsson, H. Environmental aspects of geothermal energy utilization. Geothermics 32 (4–6), 451–461 (2003).

Soltani, M. et al. Environmental, economic, and social impacts of geothermal energy systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 140, 110750 (2021).

Kumar, S., Gupta, S. K. & Rawat, M. Resources and utilization of geothermal energy in India: An eco–friendly approach towards sustainability. Materials Today: Proceedings, 26: pp. 1660–1665. (2020).

Adebayo, T. S. Trade-off between environmental sustainability and economic growth through coal consumption and natural resources exploitation in china: new policy insights from wavelet local multiple correlation. Geol. J. 58 (4), 1384–1400 (2023).

Wenlong, Z. et al. Impact of coal rents, transportation, electricity consumption, and economic globalization on ecological footprint in the USA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30 (15), 43040–43055 (2023).

Hao, F. & Van Brown, B. L. An Analysis of Environmental and Economic Impacts of Fossil Fuel Production in the US from 2001 To 201532p. 693–708 (Society & Natural Resources, 2019). 6.

Xu, Q. & Khan, S. How do R&D and renewable energy consumption lead to carbon neutrality?? Evidence from G-7 economies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20 (5), 4604 (2023).

Destek, M. A. & Sinha, A. Renewable, non-renewable energy consumption, economic growth, trade openness and ecological footprint: evidence from organisation for economic Co-operation and development countries. J. Clean. Prod. 242, 118537 (2020).

Acknowledgments

This research is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (72243005, 72350410488) and the Key Program of National Social Science Fund of China (21AZD067).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gulzara Tariq: Conceptualization, Methodology, and analysis, Muhammad Azhar Hussain: Conceptualization, Methodology, Mohammad Al-Shboul : Validation and investigation, Supervision, Guoping Ding: Investigation and visualization, Huaping Sun: Formal analysis, Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tariq, G., Hussain, M.A., Al-Shboul, M. et al. Impacts of green and non-green energies production and R&D on ecological and carbon footprints. Sci Rep 15, 43412 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11839-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-11839-5

Showed negative relationship,

Showed negative relationship,  showed positive relationship,

showed positive relationship,  Showed bi-directional relationship, and

Showed bi-directional relationship, and  Uni-directional relationship is signified by .

Uni-directional relationship is signified by .