Abstract

Malaria remains one of the leading causes of global morbidity and mortality, with millions of cases and fatalities annually. Effective intervention strategies by public health authorities and medical practitioners necessitate a robust understanding of disease transmission dynamics. This study presents a novel framework for modeling malaria transmission dynamics by integrating temperature and altitude-dependent transmission functions into a compartmental SIR-SI model. A key innovation lies in the introduction of a new transmission function that explicitly captures environmental dependencies, enhancing realism in the modeling of disease spread. We conduct steady-state analysis of the system, establishing the stability criteria for both disease-free and endemic equilibria through linearization techniques. We used a novel transmission function to model the dependence on temperature and altitude. To address the challenge of accurate parameter estimation, we develop a comparative learning framework using ANNs, RNNs, and PINNs, with PINNs standing out by embedding epidemiological dynamics into the training process. This enables physics-constrained parameter inference, significantly enhancing predictive performance over purely data-driven approaches. Additionally, we implement Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) to derive a data-driven transmission risk index from infection trajectory data, providing a novel and interpretable metric for real-time risk assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the 2022 report by the World Health Organization (WHO), Africa remains the region most severely affected by malaria globally. Notably, 94% of the world’s 233 million malaria cases and 95% of global malaria-related fatalities (approximately 580,000 deaths) occur on the African continent (Fig. 1). These figures underscore malaria’s disproportionate mortality burden in Africa, emphasizing the critical need for advanced modeling frameworks to enhance healthcare professionals’ understanding of disease transmission dynamics.

In epidemiological research, compartmental models based on ordinary differential equations (ODEs) are widely used to analyze disease spread. These models partition populations into distinct, mutually exclusive compartments, enabling the mathematical study of transitions between health states (e.g., infection, recovery, vaccination, or death). Commonly employed frameworks include the SIR (Susceptible-Infected-Recovered), SIRD (Susceptible-Infected-Recovered-Deceased), and SIRDV (Susceptible-Infected-Recovered-Deceased-Vaccinated) models, which simulate population flows through ODE-derived rates of change. Early mathematical models of malaria laid the foundation for understanding transmission dynamics. Ross introduced a two-compartment model capturing basic interactions between infected humans and mosquitoes but omitted the parasite’s latent period (see1,2,3,4). MacDonald5 later incorporated the mosquito latent phase, while Anderson refined the framework by modeling both human and mosquito susceptibility and infection explicitly. For detailed developments and comparisons of these models, see6.

In the study by Ogueda et al.7, a variant of the physics-informed neural network (PINN), termed the disease-informed neural network (DINN), was employed as a deep learning model. The SIRD compartmental model was utilized to analyze disease dynamics, incorporating the movement of individuals between cities. The primary objective of this work was to predict various parameters, including the rates of transmission, mortality, and recovery for the selected cities, as well as the rate of movement of individuals between them. Several studies have combined compartmental epidemic models with physics-informed and deep learning approaches to model COVID-19 dynamics. These include applications of PINNs to SIR-type models for estimating transmission and recovery rates8,9,10, and the integration of LSTM and DNN with extended compartmental frameworks to forecast short- and medium-term trajectories across different regions11,12,13,14. For a broader overview of related statistical and deep learning models, see15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Several studies have also investigated stochastic models for infectious diseases; for further details, we refer to26,27..

In the study by Bhuju et al.28, the temperature dependence of the transmission rate was analyzed using the SEIR model for humans and the LSEI model for mosquitoes. The authors conducted various mathematical analyses, including the stability of the disease-free equilibrium and the existence of the endemic equilibrium. Numerical simulations across different temperature scenarios revealed that temperature significantly influences the transmission rate. Keno et al.29 examined the temperature dependency of the transmission parameter using the SIR model for humans and the SI model for mosquitoes. Their analysis includes assessments of both local and global stability of equilibrium points. The study demonstrated that when the basic reproduction number is less than one, the disease-free equilibrium is both locally and globally asymptotically stable. Additionally, the impact of temperature on transmission dynamics was investigated, reinforcing the conclusion that temperature plays a critical role in disease transmission.

In the study by Proctor et al.30, Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) was utilized to incorporate control effects and extract low-order models from high-dimensional, complex systems. Alla and Kutz31 implemented DMD to reduce the order of a nonlinear dynamical system. Similarly, Andreuzzi et al.32 extended DMD for forecasting future states of parametric dynamical systems. Watson et al.33 employed a Bayesian time series model in conjunction with random forests to predict the number of cases and deaths using the SIRD compartmental model, conducting a 21-day forecast for three cities: New York, Colorado, and West Virginia. Additional research on mathematical models of malaria and dengue can be found in34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. Most existing studies on malaria transmission dynamics primarily rely on mathematical modeling. In contrast, this work leverages deep learning methods to analyze the dynamics of malaria transmission. One key advantage of using the neural network approach is that these models are designed to emulate the human brain, allowing them to capture complex patterns in data. This capability makes deep learning particularly well-suited for modeling malaria dynamics.

This study employs a feedforward Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to predict trajectories across all five compartments of the epidemiological model. To infer malaria transmission parameters, we implement a comparative analysis using three machine learning architectures: ANNs, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs). RNNs are uniquely suited for this task due to their capacity to capture temporal dependencies in sequential data, enabling robust forecasting by leveraging historical trends. PINNs further enhance parameter estimation by integrating domain-specific physical laws–derived from the governing equations of the SIR-SI system–directly into the neural network’s loss function, ensuring biologically plausible outputs. For risk quantification, Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) is applied to infected population trajectories; unlike conventional deep learning methods, DMD operates as a data-driven modal decomposition technique, extracting dominant spatial-temporal patterns to characterize transmission risks without requiring a priori mechanistic assumptions. Central to this analysis is the multivariate environmental dependence of the transmission rate, which is rigorously evaluated through the concurrent effects of temperature and altitude–a critical advancement over prior univariate approaches.

The remainder of this work is structured as follows: Section Model formulation introduces the mathematical formulation of the compartmental epidemiological model, incorporating environmental dependencies such as temperature and altitude into the transmission dynamics. Section Data-Driven Methods details the analytical and computational framework, beginning with the problem statement, followed by methodology encompassing steady-state stability analysis, parameter estimation using artificial neural networks (ANNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), and concluding with results evaluating trajectory predictions and risk quantification via dynamic mode decomposition (DMD). Finally, Section Concluding remarks synthesizes the findings, discusses their implications for malaria mitigation strategies, and proposes future research directions to enhance model generalizability and real-world applicability.

Model formulation

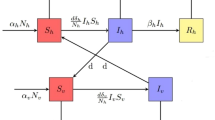

This section presents a compartmental epidemiological model to capture the interdependent dynamics of malaria transmission between human and mosquito populations, a necessity given the disease’s reliance on cross-species interaction. The human population is divided into three compartments: susceptible (\(S_h\)), infected (\(I_h\)), and recovered (\(R_h\)). In parallel, the mosquito population is categorized into susceptible (\(S_m\)) and infected (\(I_m\)) compartments. The model accounts for bidirectional transmission mechanisms: infected mosquitoes (\(I_m\)) transmit the parasite to susceptible humans (\(S_h\)), increasing the \(I_h\) population, while infected humans (\(I_h\)) subsequently infect susceptible mosquitoes (\(S_m\)), driving the rise of \(I_m\). These interactions are governed by density-dependent transmission rates, reflecting real-world contact patterns. The model assumes constant birth and death rates, homogeneous mixing of the population, and no demographic or spatial heterogeneity. Figure 2 schematically represents the coupled transmission pathways, emphasizing the feedback loop central to malaria’s persistence.

For the human population, we consider the standard SIR model, and for the mosquito population, we consider the SI model. The following is the system of differential equations.

The model used in this work is the SIR-SI model. The SIR model is used for the human population, and the SI model is used for the mosquito population. Table 1 and 2 explain the compartments and the parameters used.

Disease-free steady state analysis

In this section, we perform the steady-state analysis. Steady-state solutions play an important role when the analytical solution is not known, and we want to study the qualitative properties of solutions.

We define the basic reproduction number for the model (1) as

Observe that the basic reproduction number depends on recruitment rates, infection rates, recovery rates, and mortality rates.

Theorem 1

If \(R_{0}<1\), the disease-free steady state is locally stable.

Proof

For the analysis of the disease-free steady state, we need to equate the infected and recovered populations of both species to zero. Therefore, we obtain \(S_{h} = \frac{\Gamma _{h}}{\mu _{h}}\), \(I_{h} = 0\), \(R_{h} = 0\), \(S_{m} = \frac{\Gamma _{m}}{\mu _{m}}\), \(I_{m} = 0.\)

Dividing the first three equations \(N_{h}\) and the last two equations with \(N_{m}\) in (1), we get

Now our task is to linearize the system (2) around the disease-free steady state. After linearization, we obtain the following system

Constructing the Jacobian matrix, we get

The characteristic polynomial of the above matrix is

For the system to be stable, all the eigenvalues must have negative real parts. It is clear that three of the eigenvalues are negative; we need to check the roots of the quadratic polynomial for the remaining two eigenvalues. By solving the quadratic equation, we get the roots as

If we observe, the second root is always negative, and thus we need to find out the condition for which the first root is negative, and that is

Rearranging the above inequality, we get the expression

So, if \(R_{0}<1,\) it will ensure us that the disease-free steady state is stable. \(\square\)

Endemic steady state analysis

In this subsection, we aim to study the stability of the endemic steady-state.

The given system of equations is

Before proceeding with the next theorem, it is essential to define the following quantities

where \(S^{*}_{m},S^{*}_{h},I^{*}_{m},I^{*}_{h}\) are the non trivial equilibrium solutions.

Theorem 2

If \(R_{0}>1\) and \(b, c, d, bc-d >0\), the endemic steady state is locally stable.

Proof

The equilibrium points will be obtained by equating all of the above time derivatives to zero, and solving them for non-trivial solutions, we obtain the solutions as

Linearizing the model (2) around the endemic equilibrium point, we get the following system

Writing the Jacobian matrix, we get

The characteristic polynomial of the above matrix is

From the above equation, we can see that we have two linear factors and a cubic factor. To analyze the cubic factor, let us state the following lemma:

Lemma 1

Let \(f(x) = ax^3 + bx^2 + cx + d\) be a cubic polynomial. For f(x) to have all negative roots or complex roots with negative real parts, the following conditions are necessary:

Now, by using the above-stated lemma, we can arrive at our required result. \(\square\)

Remark 1

Equilibrium points are crucial for evaluating malaria control efforts. A disease-free equilibrium indicates that transmission can be halted through vector control and drug administration, while an endemic equilibrium suggests sustained transmission, requiring ongoing interventions. Stability analysis helps identify critical thresholds, such as intervention coverage or mosquito density, to guide effective control strategies.

Numerical validation of the stability theorems

In the previous section, we established that the disease-free steady state is attained when \(R_0 < 1\). Accordingly, we selected \(R_0 = 0.04, 0.16,\) and \(0.51\), ensuring \(R_0 < 1\). As shown in Figs. 3, 4, and 5, the infected populations of humans and mosquitoes decline over time.

From Figs. 3, 4, and 5, we observe that the proposed model for malaria spread exhibits stable dynamics when the reproduction number remains below 1. Furthermore, as the reproduction number increases, the peak infection level intensifies, indicating a heightened disease burden within the population.

Importance of steady-state analysis and equilibrium points

Steady-state analysis in malaria modeling provides insights into the long-term behavior of transmission dynamics, focusing on equilibrium points where the rate of new infections and recoveries stabilizes. These equilibrium points are critical in understanding malaria persistence and eradication potential in specific regions. Identifying whether the system reaches a disease-free equilibrium or a sustained endemic state allows for targeted intervention strategies.

For malaria control, equilibrium points are essential for assessing the effectiveness of interventions. A disease-free equilibrium indicates that malaria transmission can be halted, typically through a combination of vector control measures such as insecticide-treated nets, indoor spraying, and mass drug administration. Conversely, an endemic equilibrium suggests that transmission is sustained within the population despite interventions, indicating that continuous, long-term strategies such as routine treatment, surveillance, and seasonal control programs are needed to keep malaria prevalence low. Stability analysis of these equilibrium points helps to identify critical thresholds, such as coverage levels for interventions or mosquito density, that determine whether malaria transmission will be suppressed or continue to persist, guiding the implementation of more effective control measures.

This inequality indicates that if the basic reproduction number \(R_0\) is less than 1, it ensures that the disease-free steady state is stable, further supporting the potential for malaria eradication through effective control strategies.

Temperature and altitude dependence of the transmission rate

Several factors influence malaria transmission; however, Patz et al.44 identify temperature and altitude as among the most significant. Therefore, we model transmission as a function of temperature and altitude as follows:

where \(\beta _{0}\) is the transmission constant of the region, T is the temperature of the region, h is the altitude, \(\eta\) and \(\xi\) are the constants associated with the region’s temperature and height, respectively. The Gaussian function is centered at \(25^{\circ }C\), as this temperature is biologically optimal for mosquito survival, leading to maximum transmission. This aligns with the findings of Shapiro et al.45, which also identify a similar optimal temperature for malaria mosquito breeding.

Here \(e^{-\frac{(T-25)^{2}}{\eta ^{2}}}\) is used to model the temperature and \(e^{-\frac{h^{2}}{\xi ^{2}}}(1-e^{-\frac{h^{2}}{\xi ^{2}}})\) is used to model the height. Malaria transmission will be very minimal when the temperature is either extremely high or it is extremely low and thus to model this variation, the Gaussian function is used and the reason for shifting it by 25 is because the optimum temperature for mosquito’s existence and malaria transmission is \(25\,^\circ \textrm{C}\). Also, malaria transmission is completely zero when the altitude is zero since there won’t be any mosquitoes in the sea and in the same way when the altitude is extremely high again the transmission is completely zero since there are no mosquitoes in the space and thus to model both of these conditions the negative exponential function is used in this manner.

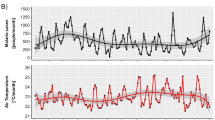

At a constant altitude of 75 meters, temperature variations above and below \(25^\circ \textrm{C}\) were rigorously assessed to determine their influence on transmission dynamics. Our analysis reveals that \(25^\circ \textrm{C}\) serves as the optimal temperature for maximizing transmission rates. Analysis demonstrates a consistent decline in both infected mosquito and human populations as temperatures rise beyond this threshold. Furthermore, population trends for infected mosquitoes and humans align with a Gaussian distribution, reflecting a symmetrical, bell-shaped relationship with temperature. These findings underscore the critical role of temperature regulation in transmission mitigation strategies.

Assuming the temperature is from \(T_1\) to \(T_2\) and the height is from \(h_1\) to \(h_2\), we can write

Here, the effect of transmission rate is studied (Figs. 6 - 8) by changing the temperature values for a fixed height. The parameters considered are the following: \(\beta _{0} = 10\), and for human we have taken \(\eta =200 ,\xi = 20000\) and for mosquitoes, \(\eta = 400 , \xi = 40000\). The different temperature values which we used are \(25^\circ\), \(30^\circ\), \(35^\circ\), \(40^\circ\), \(45 ^\circ\).

When the altitude was maintained at \(100\; m\), temperature variations were analyzed to assess their impact on transmission dynamics. The findings confirm that \(25^\circ \textrm{C}\) is the optimal temperature for maximizing the transmission rate. Additionally, the population density of infected mosquitoes was higher compared to an altitude of \(75\; m\), though the variation was marginal.

At a fixed altitude of \(125\; m\), the impact of temperature variations on transmission dynamics was analyzed. The findings consistently indicate that \(25^\circ \textrm{C}\) remains the optimal temperature for maximizing the transmission rate. A similar trend was observed, with a slight variation in the population of infected mosquitoes, reaching its peak at a higher point.

At a constant temperature of \(28^\circ \textrm{C}\), altitude variations were studied. Population density trends for infected mosquitoes and humans exhibit a Gaussian distribution, reflecting a symmetrical, bell-shaped relationship with altitude. These findings highlight the significant impact of altitude on disease transmission and emphasize the importance of considering elevation in vector control strategies.

The impact of altitude variations on transmission dynamics was further analyzed at a fixed temperature of \(42^\circ \textrm{C}\). In this case, a more significant decline in the population of infected mosquitoes was observed. These findings highlight the critical role of altitude in shaping transmission patterns and optimizing intervention strategies.

From Figs. 9 to 11, we observe that the transmission rate is highest when the altitude is 150. This represents the maximum value among the altitudes considered. Therefore, we conclude that \(h = 150\) may serve as a threshold value for altitude in the model. The function \(f(h) = e^{-\frac{h^{2}}{\xi ^{2}}}(1-e^{-\frac{h^{2}}{\xi ^{2}}})\) achieves its highest value when \(h = \xi {\sqrt{\ln (2)}}\), and thus the transmission rate increases as the height value approaches \(h = {\xi \sqrt{\ln (2)}}\). By substituting both values of \(\xi\) and taking the average, we get approximately 142.1; thus, the optimal value for altitude can be concluded to be in the range \(140 - 150\), and since it can be observed that the trajectory for all of these values is nearly the same.

Data-driven methods

Unlike conventional epidemic modeling approaches grounded in deterministic differential equations, this work adopts a data-driven paradigm to analyze malaria transmission dynamics. Our methodology integrates machine learning techniques, specifically artificial neural networks (ANNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), to infer system parameters and predict trajectories directly from observational data. This shift eliminates the need for explicit implementation of complex mathematical formulations; instead, neural architectures autonomously learn latent patterns and adapt their computations through iterative training. We systematically evaluate these architectures for parameter estimation, with PINNs further constrained by epidemiological principles to ensure biological fidelity. The derived parameters are then used to forecast the infection trajectories, demonstrating how hybrid data-driven and mechanistic approaches can advance predictive modeling of malaria transmission under heterogeneous environmental conditions.

Parameter estimation

An important factor influencing disease transmission is the parameters associated with transmission dynamics. Understanding these parameters is crucial for medical professionals, as it allows them to assess the severity of the disease and implement appropriate interventions. This section presents three distinct neural network models. Artificial neural networks (ANNs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), and physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) to estimate these parameters. Using the predicted parameters, we can forecast the trajectories of the various compartments involved in the disease dynamics. We used synthetic data generated from the system (1) to ensure consistency with the governing equations (critical for PINNs), enable controlled training of ANN and RNN models, and provide a clean benchmark for comparison using realistic parameters that isolate core transmission dynamics.

The architecture of Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) employed in this study consisted of five layers, including three hidden layers. Each hidden layer comprised 15 dense units utilizing the sigmoid activation function, while the output layer contained seven dense units without an activation function. The Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) framework implemented in this work featured three layers: an input layer, a dropout layer, and an output layer. The input layer consisted of 50 Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) units with the ReLU activation function, followed by a dropout layer with a 20% dropout rate to mitigate overfitting, and an output layer with seven dense units without an activation function. The Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) architecture closely followed the ANN structure, with the primary distinction being the number of nodes in the input and output layers, which were set to one and five, respectively. This modification enabled the PINNs to incorporate physical constraints into the learning process, enhancing predictive accuracy and model generalizability.

Since three distinct neural network architectures are utilized in this study, the methodological approach differs for ANN, RNN, and PINN. For ANN and RNN, both models were trained on a dataset comprising 1000 data points, where the input consisted of the first 10 points of the trajectories for all compartments, and the output corresponded to the estimated parameters. The estimated parameters from ANN and RNN are shown in Table 3 and 4. The ANN and RNN models showed poor parameter estimation performance (errors \(>200 \%\) for some parameters), highlighting their sensitivity to hyperparameters and training. While tuning might improve results, it is time-consuming and uncertain. In contrast, the methodology for PINN diverges significantly from these conventional models, as it does not rely on a predefined training dataset. Instead, an initial set of assumed parameters is iteratively refined by minimizing the loss function, thereby ensuring convergence to the actual parameter values through a comparison between the predicted and true trajectories. Here, the input variable is time, while the output consists of the trajectories of all five compartments. The selection of parameter values in this preliminary study was deliberately generic to evaluate the PINN framework’s capability in recovering parameters under idealized conditions. While these values are not empirically derived, this approach allowed us to assess the algorithm’s performance independently of confounding factors such as data noise or parameter interdependencies. Moving forward, parameter refinement will be guided by region-specific epidemiological literature–such as African mosquito mortality rates sourced from the Malaria Atlas Project, and sensitivity analyses to identify the most influential parameters. The ability of PINNs to effectively address inverse problems will further facilitate the integration of sparse field data, such as monthly case reports, enabling a more robust and data-driven parameter estimation process in future research.

For a novel comparison between the models, each model is simulated for 20000 epochs. Details of actual and predicted parameters are given in the tables below.

From Fig. 12 and Fig. 13, it can be observed that the predictions made by PINN closely align with the actual values, demonstrating its effectiveness in parameter estimation for the SIR-SI compartment model with trajectory prediction. Additionally, the trend analysis reveals that PINN effectively captures the underlying dynamics of the system, accurately reflecting the growth and decline patterns of infections over time. The model consistently follows the expected trajectory, reinforcing its reliability in forecasting epidemic progression.

PINNs outperform traditional ANN and RNN models by integrating epidemiological equations directly into the learning process. Unlike purely data-driven approaches, PINNs enforce physical consistency through a dual loss function–combining data loss with physics-informed loss–leading to better generalization, especially under sparse data. This makes them particularly effective for parameter estimation and predictive modeling in disease dynamics, where data may be limited but underlying processes are well-understood. Loss function in PINNs involves both data loss and physics loss, which gives better estimates for parameters. Mathematically,

where:

-

\(\mathscr {L}_{physics}\) - Physics-informed loss, ensuring that the learned function satisfies the governing physical laws.

-

\(\mathscr {L}_{data}\) - Data loss, ensuring that the learned function closely matches observed data.

-

\(\mathscr {L}\) - Total loss function combining physics and data losses.

-

\(\mathscr {F}(t_i)\) - Residual of the governing physical equation at time \(t_i\).

-

\(u_{\theta }(t_i)\) - Neural network approximation of the true solution at time \(t_i\).

-

\(u_i^{true}\) - True observed data value at time \(t_i\).

-

\(\lambda _{physics}\) - Weighting factor for the physics-informed loss.

-

\(\lambda _{data}\) - Weighting factor for the data loss.

The parameters predicted by PINNs for all five compartments are presented in Table 5. The temporal evolution of the human population is depicted in Fig. 12, while the mosquito population dynamics are shown in Fig. 13. Previous studies have predominantly relied on traditional time-series or statistical methods, such as LSTM, for epidemic forecasting. For example, Wang et al.46 applied LSTM to predict COVID-19 trends, Chandra et al.47 explored ARIMA for dengue incidence modeling, Yadav et al.48 used regression frameworks for malaria risk assessment, and Elshafee et al.49 employed Bayesian statistical approaches. In contrast to these data-driven methods, our work leverages PINNs to integrate mechanistic epidemiological principles (e.g., transmission dynamics and compartmental interactions) directly into the parameter estimation process. This physics-informed approach achieves minimal error across nearly all compartments (Table 5), demonstrating its ability to reconcile observed data with domain knowledge. These results highlight the advantages of PINNs for epidemic modeling, as they inherently encode the biophysical processes governing disease spread, enabling robust parameter inference even with sparse or noisy datasets. While Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) showed promising results in our study, it is important to acknowledge their limitations. The superior performance of PINNs is largely attributed to the integration of known physical laws into the learning process. However, in scenarios where the governing dynamics are poorly understood, highly stochastic, or where the data-generating process deviates significantly from the assumed model structure, as may be the case with real, noisy malaria data, PINNs may underperform compared to conventional data-driven approaches like ANN or RNN. Thus, their applicability is inherently constrained by the availability and accuracy of the underlying physical model.

Finding the risk of a disease

The most important aspect of a disease is the determination of risk, which we define as the number of infected people in a particular region. Whenever there is a disease outbreak in a country, there are some regions where there is more risk compared to the other regions; thus, it is essential to calculate the risk of every region. This problem statement is addressed using the method of DMD (dynamic mode decomposition), and the main reason for using this method is that DMD can make exact predictions from raw data, unlike other deep learning methods. The complete methodology of the problem statement can be seen in Fig. 14.

Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) extracts spatiotemporal coherent structures from high-dimensional dynamical systems30,31,32. Given a sequence of \(m+1\) state vectors \(\textbf{x}_k \in \mathbb {R}^n\) sampled at intervals \(\Delta t\), we construct snapshot matrices:

DMD seeks a best-fit linear operator \(A \in \mathbb {R}^{n \times n}\) satisfying: \(X' \approx A X\). The solution proceeds via truncated singular value decomposition (SVD):

Solving the eigenvalue problem for \(\tilde{A}:~~~~~~ \tilde{A} W = W \Lambda , \quad \Lambda = \textrm{diag}(\lambda _i)~~\) yields full-state DMD modes:

The continuous-time eigenvalues \(\omega _i = \ln (\lambda _i)/\Delta t\) determine mode dynamics (growth/decay rates and frequencies). The reconstructed solution is: \(\textbf{x}(t) \approx \sum _{i=1}^{r} \phi _i \exp (\omega _i t) b_i, \quad \textbf{b} = \Phi ^\dagger \textbf{x}_1,\) where \(\phi _i\) are columns of \(\Phi\) and \(\textbf{b}\) contains mode amplitudes.

In this work, Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) is used to calculate the disease risk in a particular region. DMD provides early detection by identifying patterns in time-series data, facilitating timely intervention. Additionally, it performs dimensionality reduction by extracting dominant modes from large datasets, preserving essential dynamical features while reducing computational complexity. Its forecasting capability allows for accurate predictions of disease progression, aiding in proactive decision-making. Moreover, while standard DMD operates linearly, extended DMD (eDMD) can approximate nonlinear disease dynamics, making it adaptable to complex epidemiological models. DMD also captures the oscillations of the dynamics, and by analyzing its peak values, we obtain a measure of risk. The DMD plot and the eigenvalue spectrum can be found in Fig. 15.

From the eigenvalue spectrum, we can observe that all the points are either on or within the unit circle. This shows that the transmission of malaria in Africa is stable. African map with the corresponding color coding based on the risk can be found in Fig. 16.

From Sub Fig. 15b we can observe that the disease spread is not severe since all of the infections are within the unit circle. DMD extracts governing dynamics directly from observational data, making it advantageous for rapidly evolving outbreaks where mechanistic understanding is incomplete50. Unlike machine learning approaches (e.g., LSTM), which excel at long term prediction but acts as ’black boxes’, DMD provides interpretable spatial-temporal modes, albeit with trade-offs in modeling strongly nonlinear interactions. This balance positions DMD as a complementary tool for real-time risk assesment alongside established methods.

Concluding remarks

In this work, an attempt is made to understand the dynamics of malaria transmission using various mathematical and machine-learning techniques. The proposed theorems related to steady states were validated using numerical simulations. We also examined the influence of temperature and altitude on malaria transmission. Subsequently, parameter estimation was performed using three neural network architectures–ANNs, RNNs, and PINNs–where the best-performing model’s predicted parameters were utilized to forecast the trajectories of all compartments. Finally, the study assessed the measure of risk using Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD), providing valuable insights into malaria dynamics and prediction.

While these results are preliminary and based solely on synthetic data, they demonstrate the potential of the proposed methodology as a step toward developing actionable tools for policymakers. By accurately quantifying transmission dynamics in controlled settings, this approach lays the groundwork for future integration with real-world data. In particular, incorporating PINNs with real-time surveillance systems could, in principle, support the identification of transmission hotspots and inform scenario-based planning under climatic uncertainties. Such extensions, once validated with empirical data, may ultimately assist in optimizing resource allocation and enhancing outbreak preparedness in climate-sensitive regions.

In the future, we aim to enhance malaria transmission modeling by incorporating advanced physics-informed machine learning techniques. Sparse Identification of Nonlinear Dynamics (SINDy) can help discover parsimonious governing equations from data, potentially uncovering key drivers of transmission. Neural ODEs provide a flexible framework to model continuous-time disease dynamics from irregular time series data. Variants such as VPINNs (Variational PINNs) and Recurrent PINNs can improve model accuracy and scalability, particularly in capturing spatiotemporal variability and memory effects.

Data availability

This study uses only synthetic data, which was generated for the purpose of this research. The synthetic data are not based on real-world observations and can be made available upon request to the corresponding author at : a-tridane@uaeu.ac.ae

References

Ross, R. The prevention of malaria (John Murray, 1911).

Ross, R. Some a priori pathometric equations. Br. Med. J. 1, 546 (1915).

Ross, R. An application of the theory of probabilities to the study of a priori pathometry.part i. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing papers of a mathematical and physical character 92, 204–230 (1916).

Ross, R. & Hudson, H. P. An application of the theory of probabilities to the study of a priori pathometry.part iii. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series A, Containing papers of a mathematical and physical character 93, 225–240 (1917).

Macdonald, G. The epidemiology and control of malaria (Oxford University Press, 1957).

Mandal, S., Sarkar, R. R. & Sinha, S. Mathematical models of malaria-a review. Malar. J. 10, 1–19 (2011).

Ogueda, A., Martinez, E., Arunachalam, V. & Seshaiyer, P. Machine learning for predicting the dynamics of infectious diseases during travel through physics informed neural networks. Journal of Machine Learning for Modeling and Computing (2023).

Schiassi, E., De Florio, M., D’Ambrosio, A., Mortari, D. & Furfaro, R. Physics-informed neural networks and functional interpolation for data-driven parameters discovery of epidemiological compartmental models. Mathematics 9, 2069 (2021).

Ning, X., Guan, J., Li, X.-A., Wei, Y. & Chen, F. Physics-informed neural networks integrating compartmental model for analyzing covid-19 transmission dynamics. Viruses 15, 1749 (2023).

Ning, X., Li, X.-A., Wei, Y. & Chen, F. Euler iteration augmented physics-informed neural networks for time-varying parameter estimation of the epidemic compartmental model. Front. Phys. 10, 1062554 (2022).

Deng, Q. Dynamics and development of the covid-19 epidemics in the us–a compartmental model with deep learning enhancement. medRxiv 2020–05 (2020).

Bousquet, A., Conrad, W. H., Sadat, S. O., Vardanyan, N. & Hong, Y. Deep learning forecasting using time-varying parameters of the sird model for covid-19. Sci. Rep. 12, 3030 (2022).

Deng, Q. Modeling the omicron dynamics and development in china: with a deep learning enhanced compartmental model. medRxiv 2022–06 (2022).

Deng, Q. & Wang, G. A deep learning-enhanced compartmental model and its application in modeling omicron in china. Bioengineering 11, 906 (2024).

Baccega, D., Castagno, P., Fernández Anta, A. & Sereno, M. Enhancing covid-19 forecasting precision through the integration of compartmental models, machine learning and variants. Sci. Rep. 14, 19220 (2024).

Chen, W., Luo, H., Li, J. & Chi, J. Long-term trend prediction of pandemic combining the compartmental and deep learning models. Sci. Rep. 14, 21068 (2024).

Ma, J. et al. Rnn enhanced compartmental model for infectious disease prediction. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Digital Health (ICDH), 225–236 (IEEE, 2024).

Millevoi, C., Pasetto, D. & Ferronato, M. A physics-informed neural network approach for compartmental epidemiological models. PLoS Comput. Biol. 20, e1012387 (2024).

Islam, M. S., Shahrear, P., Saha, G., Ataullha, M. & Rahman, M. S. Mathematical analysis and prediction of future outbreak of dengue on time-varying contact rate using machine learning approach. Comput. Biol. Med. 178, 108707 (2024).

Xue, D., Wang, M., Liu, F. & Buss, M. Time series modeling and forecasting of epidemic spreading processes using deep transfer learning. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 185, 115092 (2024).

Shukla, S. S. P., Jain, V. K., Yadav, A. K. & Pandey, S. K. Fourth wave covid19 analyzing using mathematical seirs epidemic model & deep neural network. Multimed. Tools Appl. 83, 27507–27526 (2024).

Juneja, M., Saini, S. K., Kaur, H. & Jindal, P. Statistical machine and deep learning methods for forecasting of covid-19. Wireless Personal Communications 138, 497–524 (2024).

Cumbane, S. P. & Gidófalvi, G. Deep learning-based approach for covid-19 spread prediction. International Journal of Data Science and Analytics 1–17 (2024).

Hu, H., Kennedy, C. M., Kevrekidis, P. G. & Zhang, H.-K. A modified pinn approach for identifiable compartmental models in epidemiology with application to covid-19. Viruses 14, 2464 (2022).

Anwar, N. et al. Stochastic supervised neuro-architecture design for analyzing vector-borne plant virus epidemics with latency and incubation effects. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 139, 1–34 (2024).

Anwar, N. et al. Intelligent bayesian neural networks for stochastic svis epidemic dynamics: Vaccination strategies and prevalence fractions with wiener process. Fluctuation and Noise Letters 24, 2550020–198 (2025).

Anwar, N. et al. Dynamical analysis of hepatitis b virus through the stochastic and the deterministic model. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 1–17 (2025).

Bhuju, G., Phaijoo, G. & Gurung, D. Mathematical study on impact of temperature in malaria disease transmission dynamics. Advances in Computer Sciences 1, 1–8 (2018).

Keno, T. D., Makinde, O. D. & Obsu, L. L. Impact of temperature variability on sirs malaria model. Journal of Biological Systems 29, 773–798 (2021).

Proctor, J. L., Brunton, S. L. & Kutz, J. N. Dynamic mode decomposition with control. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 15, 142–161 (2016).

Alla, A. & Kutz, J. N. Nonlinear model order reduction via dynamic mode decomposition. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 39, B778–B796 (2017).

Andreuzzi, F., Demo, N. & Rozza, G. A dynamic mode decomposition extension for the forecasting of parametric dynamical systems. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 22, 2432–2458 (2023).

Watson, G. L. et al. Pandemic velocity: Forecasting covid-19 in the us with a machine learning & bayesian time series compartmental model. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1008837 (2021).

Traoré, B., Koutou, O. & Sangaré, B. A global mathematical model of malaria transmission dynamics with structured mosquito population and temperature variations. Nonlinear Analysis: Real World Applications 53, 103081 (2020).

Koella, J. C. On the use of mathematical models of malaria transmission. Acta tropica 49, 1–25 (1991).

Chitnis, N., Hyman, J. M. & Cushing, J. M. Determining important parameters in the spread of malaria through the sensitivity analysis of a mathematical model. Bull. Math. Biol. 70, 1272–1296 (2008).

Chitnis, N., Cushing, J. M. & Hyman, J. Bifurcation analysis of a mathematical model for malaria transmission. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 67, 24–45 (2006).

Osman, M. & Adu, I. Simple mathematical model for malaria transmission. Journal of Advances in Mathematics and Computer Science 25, 1–24 (2017).

Dudley, H. J., Goenka, A., Orellana, C. J. & Martonosi, S. E. Multi-year optimization of malaria intervention: a mathematical model. Malar. J. 15, 1–23 (2016).

Gebremeskel, A. A. & Krogstad, H. E. Mathematical modelling of endemic malaria transmission. American Journal of Applied Mathematics 3, 36–46 (2015).

Eikenberry, S. E. & Gumel, A. B. Mathematical modeling of climate change and malaria transmission dynamics: a historical review. J. Math. Biol. 77, 857–933 (2018).

Yacheur, S., Moussaoui, A. & Tridane, A. Modeling the imported malaria to north africa and the absorption effect of the immigrants. Math. Biosci. Eng. 16, 967–989 (2019).

Raza, A., Arif, M. S. & Rafiq, M. A reliable numerical analysis for stochastic dengue epidemic model with incubation period of virus. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2019, 1–19 (2019).

Patz, J. A. & Olson, S. H. Malaria risk and temperature: influences from global climate change and local land use practices. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 5635–5636. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0601493103 (2006).

Shapiro, L. L., Whitehead, S. A. & Thomas, M. B. Quantifying the effects of temperature on mosquito and parasite traits that determine the transmission potential of human malaria. PLoS Biology 15, e2003489 (2017).

Wang, P., Zheng, X., Ai, G., Liu, D. & Zhu, B. Time series prediction for the epidemic trends of covid-19 using the improved lstm deep learning method: Case studies in russia, peru and iran. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 140, 110214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110214 (2020).

Chandra, R., Jain, A. & Singh Chauhan, D. Deep learning via lstm models for covid-19 infection forecasting in india. PLoS One 17, e0262708. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262708 (2022).

Yadav, S. K. & Akhter, Y. Statistical modeling for the prediction of infectious disease dissemination with special reference to covid-19 spread. Front. Public Health 9, 645405 (2021).

ElShafee, A., El-Shafai, W., Algarni, A. D., Soliman, N. F. & Aly, M. H. Statistical time series forecasting models for pandemic prediction. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 47 (2023).

Proctor, J. L. & Eckhoff, P. A. Discovering dynamic patterns from infectious disease data using dynamic mode decomposition. Int. Health 7, 139–145 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contribute equally conception and design of the work; modeling, analysis: A.R. and M.K.; visualization and interpretation of the results: A.R., M.K., A.T.; funding and supervising: A.T.; wrote the paper: A.R., M.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rajnarayanan, A., Kumar, M. & Tridane, A. Analysis of a mathematical model for malaria using data-driven approach. Sci Rep 15, 27272 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12078-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12078-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Modeling NRTIs and PIs class drug therapy on the dynamics of HIV infection with real patient data analysis and optimized control strategy

Scientific Reports (2026)

-

Advanced ANN-LMB modeling of hepatitis B transmission across sexual networks and its disability burden

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Nonlinear modeling of cerebral malaria transmission with neuro-disability via ANN-LMB enhanced SITRM model

Journal of Applied Mathematics and Computing (2025)