Abstract

The global spread of SARS-CoV-2 was significantly impacted by the emergence of Variants of Concern (VOC), with Pakistan experiencing similar trends to other countries. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the genomic epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 strains circulating during Pakistan’s third and fourth pandemic waves, we conducted the largest single sequencing effort in the country to date. Using the GridION platform (Oxford Nanopore Technologies), we performed whole genome sequencing on 1052 confirmed COVID-19 patient samples collected from multiple cities across Pakistan between March and October 2021. Our analysis revealed a clear temporal shift in variant dominance. The Alpha variant (B.1.1.7 lineage) predominated in the first half of 2021, while the Delta variant (B.1.617.2) became most prevalent in the latter half. This transition reflects global trends and provides crucial insights into the timing and dynamics of this shift within Pakistan. Mutational analysis revealed that the most frequent nucleotide mutations in Pakistani SARS-CoV-2 samples were A23403G (associated with the D614G mutation in the spike protein), C3037T, C14408T, and C241T, potentially contributing to increased disease transmission and evasion of host immune responses. The rapid evolution and spread of these circulating variants highlight the possibility of novel variants emerging with enhanced mutational fitness. The AY.108 lineage, which has been reported at relatively low frequencies globally including in Europe and North America, with Pakistan accounting for approximately 34% of global cases, suggesting potential regional evolution or specific introduction events. Our findings underscore the dynamic nature of SARS-CoV-2 and emphasize the critical importance of ongoing, large-scale genomic surveillance in Pakistan. This study demonstrates the feasibility and utility of using nanopore sequencing for comprehensive viral monitoring in Pakistan’s public health context. While we utilized the higher-throughput GridION platform for centralized processing, the Oxford Nanopore technology still provided distinct advantages through its simplified library preparation protocol, flexible run capacities, and reduced computational requirements for base-calling compared to traditional high-throughput sequencers. These benefits enabled efficient processing of our large sample batches collected from distributed sites across the country, demonstrating a scalable approach for genomic surveillance that balances throughput needs with resource availability. This could inform future public health strategies, including vaccine updates and targeted interventions. Continued monitoring and adaptive strategies are essential to keep pace with the evolving viral ecology and to enhance preparedness for future outbreaks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO). As of 2023, there have been over 776 million confirmed COVID-19 cases and more than 7 million deaths reported worldwide1. The causative agent of COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, is a positive-sense RNA virus with a viral quasispecies and a genome size of approximately 30 kb2. By September 2022, several lineages and sub-lineages3along with five major variants of concern (VOCs), had been reported4. These VOCs, named Alpha (B.1.1.7)5Beta (B.1.351)6Gamma (P.1)7Delta (B.1.617.2 )8and Omicron B.1.1.529, including sublineages such as (BA.1, BA.2, BA.3, BA.4, and BA.5), were linked to significant surges in infection rates in the countries where they first emerged. These variants acquired numerous mutations, particularly in the spike (S) glycoprotein, altering the virus’s properties9,10. Compared to the original Wuhan lineage of SARS-CoV-2, the Alpha variant exhibited additional mutations and increased transmissibility. The Beta and Gamma variants not only showed enhanced transmission but also higher rates of reinfection. The Delta variant, in particular, demonstrated 60% greater transmissibility than the Alpha variant and was associated with increased hospitalizations11,12.

When a virus invades a naive population, genomic surveillance is crucial for developing an effective disease prevention and control strategy13. Recent advancements in genome sequencing technologies have significantly improved the connection between human health and the ability to respond quickly to infectious diseases14. During past viral outbreaks, including Ebola virus15SARS-CoV16MERS-CoV17and Zika virus18direct sequencing of patient samples played a crucial role in precisely identifying the source of the virus. This, in turn, helped to eliminate the source and halt further transmission of the disease. In Pakistan, the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in distinct waves. The country reported its first case on February 26, 2020, with subsequent waves peaking in June 2020, December 2020, April 2021, and August 2021. Previous genomic studies in Pakistan have been limited in scope, with one study indicating the dominance of the B.1 lineage during the first wave, B.1.36 in the second wave, and B.1.1.7 in the third wave. However, a comprehensive genomic surveillance effort covering multiple regions and extended time periods has been lacking, limiting the full understanding of SARS-CoV-2 dynamics in the country. In the most recent case of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, continuous monitoring of the virus’s genomic characteristics enabled global health authorities to assess and promptly identify emerging variants of interest (VOIs) and variants of concern (VOCs). This genomic surveillance played a crucial role in guiding scientists and policymakers in enacting measures such as social distancing, quarantine, and the use of face masks, as well as in developing vaccines to better control the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Nanopore sequencing has seen significant growth in both fundamental and applied research19. Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) devices have been effectively used for the surveillance of various viral outbreaks, including Ebola20 and Zika21. Protocols have been established for sequencing SARS-CoV-2 to support research and public health monitoring. Advancements in nanopore technologies, which specialize in sequencing long-read DNA and RNA molecules, have significantly improved both precision and processing capacity. Applications of nanopore sequencing include genome assembly, identification of full-length transcripts, and detection of base modifications. Its use also extends to more specialized areas, such as rapid clinical diagnosis and monitoring of disease outbreaks22.

With a population of over 240 million, Pakistan is the fifth most populous country in the world. By October 2022, Pakistan had recorded more than 1.5 million SARS-CoV-2 infections resulting in over 30,000 deaths23. The geographic distribution of cases revealed highest numbers in Sindh province (n = 594,417), followed by Punjab (n = 522,243), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (n = 224,312), Islamabad (n = 139,425), and Balochistan (n = 36,002), highlighting regional variation in disease burden across the country. A previous study24 showed that the B.1 lineage was dominant during the first wave of the epidemic in Pakistan, B.1.36 during the second wave, and B.1.1.7 during the third wave. A fourth wave emerged in July 2021, peaking on August 4, 2021, during which 22 sub-lineages of the Delta variant were observed25. The current study aims to conduct genomic sequencing and characterization of a large cohort of SARS-CoV-2 samples using Oxford Nanopore Technologies to better understand the disease dynamics in Pakistan.

Materials and methods

Informed consent

Informed consent was waived by the National Institute of Health (NIH) Pakistan, as samples were collected as part of routine COVID-19 surveillance activities during the pandemic under their authority. Ethical approval was provided by the Khyber Medical University Ethics Committee for the Khyber Medical University samples (PHRL/KMU/2020/Ethics/001). All procedures were conducted in accordance with relevant international and local laws and The Declaration of Helsinki.

Clinical sample collection

Oropharyngeal swab samples from COVID-19 patients, confirmed positive by real-time PCR (with Ct values < 25), were collected from three different public health labs in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province. These labs included the Public Health Reference Laboratory at Khyber Medical University (PHRL-KP) in Peshawar (Lab 1), the Public Health Laboratory in Swat (Lab 2), and the COVID-19 Hospital Lab (Merf Pakistan) in Peshawar (Lab 3). A total of 552 samples were collected from these officially designated labs in KPK for whole genome sequencing. Oropharyngeal swab samples were collected and transported to the lab in Viral Transport Media (VTM; Biogen GmbH). The SARS-CoV-2 virus was detected using commercially available real-time PCR detection kits (TaqPath, Thermo Fisher, USA) and qPCR machines. Patient information was retrieved from the IPMS/KP dashboard, the public database of COVID-19 patients. This included personal and demographic details, sample collection dates, test dates, and, if available, clinical and hospitalization history. An additional 500 samples were provided by the Department of Virology at the National Institute of Health (NIH) in Islamabad, from COVID-19 confirmed patients. RNA was extracted from samples collected in VTM. Amplification was then performed using the one-step Genrui Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Nucleic Acid Detection Kit, specifically designed for the TaqMan Assay. Real-time PCR was conducted on a SYSTAAQ AB QuantGene machine to quantify and analyze the results. Patient personal and demographic data, sample collection and test dates, clinical information, and, where applicable, hospitalization history were retrieved from the LIMS dashboard, the public COVID-19 database. Samples were collected from various cities across Pakistan, including Islamabad, Peshawar, Rawalpindi, Karachi, and others, to ensure broad geographical representation. However, it should be noted that sampling density varied between locations and over time due to logistical constraints and local outbreak dynamics.

RNA extraction

RNA was extracted from oropharyngeal swabs at Khyber Medical University using the Automatic Nucleic Extractor (ASCEND HERO 32, China) and magnetic beads for RNA separation. RNA from the samples collected at NIH Islamabad was extracted using the MagMax™ Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit and the KingFisher™ Flex Purification System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The extracted RNA was stored at -80 °C until it was shipped for Whole Genome Sequencing, using dry ice.

Tiling PCR with ARTIC SARS-CoV-2 panel

For 1052 COVID-19 clinical samples, cDNA was synthesized using Lunascript RT Supermix (NEB BioLabs). To 8 µL of RNA sample, 2 µL of Lunascript RT Supermix was added. The samples were then incubated in a thermocycler under the following conditions: primer annealing at 25 °C for 2 min, cDNA synthesis at 55 °C for 20 min, and heat inactivation of the polymerase enzyme at 95 °C for 1 min. The ARTIC Network SARS-CoV-2 sequencing protocol and V3 primer amplicon set (https://artic.network/ncov-2019) were used for sequencing near full-length SARS-CoV-2 genomes on the GridION platform (Oxford Nanopore). The NEBNext ARTIC SARS-CoV-2 Companion Kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) was used for PCR amplification and sequencing library preparation. For PCR, 9 µL of total cDNA was used (4.5 µL for each of primer panels 1 and 2). After gently mixing the Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity 2X Master Mix, 6.25 µL was added to the PCR mixture, followed by the addition of 1.75 µL of NEBNext ARTIC Primer Mix 1 and 2. A two-step PCR was performed under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 30 s (one cycle), followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, and annealing and extension at 63 °C for 5 min. The reactions with primer panels 1 and 2 were pooled after quantification using the Quantus Fluorometer ONE dsDNA System (Promega, USA) before library preparation. The PCR products were grouped based on concentration, either high (> 10 ng/µL) or low (< 10 ng/µL), for sequencing in separate batches.

Library preparation and sequencing

SPRIselect beads (Beckman Coulter, USA) were used at a 0.4X beads-to-sample ratio to clean up the PCR amplicons. The samples were then processed using the NEBNext End Prep with NEBNext Ultra II End Repair provided in the NEBNext ARTIC SARS-CoV-2 Companion Kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies), following the manufacturer’s protocols. Barcodes were ligated using the Native Barcode Expansion Kit 1–96 (EXP-NBD196, Oxford Nanopore Technologies). Subsequently, the libraries were pooled together, and adapters were ligated. SPRIselect beads (Beckman Coulter, USA) were used to clean the reaction. For each sample, 15 µL of the eluate was recovered and prepared for sequencing by adding Sequencing Buffer (SQB) and Loading Beads (LB) from the SQK-LSK109 kit (Oxford Nanopore Technologies). Libraries were loaded onto flow cells, and sequencing was performed using the Oxford Nanopore GridION platform, following the manufacturer’s instructions. While we utilized the higher-throughput GridION platform for centralized processing, the Oxford Nanopore technology still provided distinct advantages through its simplified library preparation protocol, flexible run capacities, and reduced computational requirements for base-calling compared to traditional high-throughput sequencers. These benefits enabled efficient processing of our large sample batches collected from distributed sites across the country, demonstrating a scalable approach for genomic surveillance that balances throughput needs with resource availability. Low and high concentration samples were run on separate flow cells to obtain a relatively similar number of reads. The sequencing data were analyzed using the EPI2ME workflow ARTIC + Nextclade + Pangolin v2022.07.19–15,399.

Whole genome sequencing data, including information on clades, lineages, mutations, and ambiguous nucleotides (Ns), were obtained through the Nextclade workflow. The consensus sequences generated from the EPI2ME workflow were then submitted to the GISAID database.

Post-sequencing analysis

For the phylogenetic reconstructions, all sequences were subjected to Nextstrain26 pipeline, which mainly consists of Augur, MAFFT27 and IQ-tree28. Of the 1052 samples, 779 high-quality sequences (defined as having > 90% genome coverage, < 5% ambiguous nucleotides, and consistent read depth across the genome) were used to reconstruct the phylogeny. We also investigated whether there were any notable differences between our sample set and other SARS-CoV-2 genomes reported from Pakistan during the same time period (March–October 2021). To contextualize our findings within the broader genomic landscape of SARS-CoV-2 in Pakistan, we conducted an additional phylogenetic analysis incorporating 873 contemporary Pakistani sequences from GISAID, covering the same time period as our study samples. The resulting phylogeny was visualized using the online Auspice web server (https://auspice.us/). Phylogenetic analysis of whole SARS-CoV-2 genomes was conducted to infer the relationships between lineages over time. Pangolin was used to assign lineages to the COVID-19 sequences.

For the mutational analysis, we used the R language based Coronapp (version 1.4.0.2)29. Mutational analysis was conducted on 910 of the 1052 aligned samples that met our inclusion criteria of having at least 75% genome coverage and sufficient read depth for reliable variant calling. The aligned FASTA file was then used with the COVID-19 Genome Annotator tool (available at http://giorgilab.unibo.it/coronannotator/) to examine and identify mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 genomes. A map was generated using the Datawrapper web tool (https://www.datawrapper.de/).

Results

Demographics and age distribution of the study participants

The sample set in our study included patients from multiple cities across Pakistan, with varying sampling densities. The cities represented were Islamabad (Capital area); Rawalpindi, Attock, Lahore, and Chiniot (Punjab); Peshawar, Bannu, Charsadda, D.I. Khan, Dir Upper, Khyber, Kurram Lower, Nowshera, and Swabi (KPK); Muzaffarabad, Kotli, and Jhelum Valley (Azad Jammu and Kashmir); Karachi (Sindh); and Quetta and Gwadar (Balochistan) (Supplementary Table 1). The samples used in this study were collected during the third wave (primarily KPK samples) and the fourth wave (mainly NIH samples) of infection. The sampling was skewed towards males, who comprised 58.7% of the sample set (Supplementary Table 2). The age distribution of the patients was as follows: 11–20 years (9%), 21–30 years (25%), 31–40 years (24%), 41–50 years (17%), 51–60 years (12%), above 60 years (9%), and age unknown or not recorded (6%) (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 3). Most of the adult population (21–40 years) were infected with SARS-CoV-2 (Supplementary Table 3). Detailed information for each sample is available in the GISAID entries (see the Data Availability section).

Map of Pakistan showing the provinces and the cities from where the samples were collected for this study. (n = number of samples from each locality/ main sampling locations). Total number of samples included in the study were 1052; for detailed information about all sampling locations see supplementary Table 1, Gender Information supplementary Table 2, and age group participated in this study supplementary Table 3.

Sequence data analysis

Of the 1052 samples sequenced using GridION, 18% (191/1052) yielded nearly full-length genomes with fewer than 500 ambiguous nucleotides (Ns). Additionally, 49% of the samples contained 500–4000 Ns, 7% exhibited 4000–8000 Ns, and the remaining 26% had more than 8000 Ns. The appearance of ambiguous nucleotides in some samples resulted primarily from areas of low sequencing coverage (below 20x) or regions with high sequence complexity. Nucleotide positions were called only when they achieved a minimum coverage depth of 20x with at least 70% agreement among reads.

Genomic epidemiology of the variants of concern in Pakistan

The most prevalent variants in our data were 21J Delta (52%) and 20I Alpha (34%), followed by 20 A (5%) (). The most abundant lineages within the 20I Alpha and 21J Delta variants were B.1.1.7 (28%) and B.1.617.2 (25%), respectively (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 5).

The stacked plot shows the major lineages, mostly dominated by B.1.1.7 (20I Alpha) in Peshawar and B.1.617.2 (21J Delta) in capital territory Islamabad and other regions as well. The cities with lower number of samples are showed with the “Others”. Unassigned are the sequences with low quality which resulted as “Unassigned” from Artic-Nextclade work-flow.

Samples collected during the first half of 2021 predominantly belonged to the 20I Alpha lineage, while those collected during the second half of 2021 were primarily associated with the 21J Delta and 20 A lineages.

The samples collected from Peshawar predominantly clustered within the 20I Alpha lineage (62%), followed by 21J Delta (23%) and 20 A (9%). In Islamabad, the dominant variants were 21J Delta (89%) and 20I Alpha (3%). In Rawalpindi and Attock, cities adjacent to Islamabad, all collected samples belonged to the 21 J Delta variant. Delta variants also dominated in Karachi (Sindh), Gwadar (Balochistan), and Muzaffarabad (AJK). Other localities were primarily dominated by 21 J Delta (n = 12) and 20I Alpha (n = 10), as shown in Fig. 3a. Among the variants of concern, the B.1.1.7 lineage was the most abundant within the 20I Alpha variant (82%; n = 354), while the B.1.617.2 lineage was dominant within the 21J Delta variant (52%; n = 549). Other major lineages reported during the study period included AY.108, AY.127, and B.1.1 (Table 1).

Spatiotemporal genomic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 during 2021 in Pakistan. (a) represents the percentage distribution of major SARS-CoV-2 variants including VOCs in different regions of Pakistan. (b) the temporal percentage prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 variants across different regions in Pakistan. Variants are denoted with distinctive colors as represented in plots. Unassigned are the sequences with low quality which resulted as “Unassigned” from Artic-Nextclade work-flow.

Temporal trends of SARS-CoV-2 variants in Pakistan during 2021

The temporal distribution of variants revealed a clear shift from Alpha variant dominance in the early months of our study period to Delta variant predominance in the later months. This transition reflects the global trend of Delta outcompeting Alpha, and our data provides specific insights into the timing and dynamics of this shift within Pakistan. In our findings, the Alpha VOC (20I Alpha) was the most dominant variant in March 2021, accounting for 69% of cases, followed by 21J Delta (22%), 20A (4%), and 20B (3%). In a limited sample set collected in April 2021, three out of four samples were identified as 20H Beta. The Delta VOC (21J Delta) was the most dominant variant in May 2021, accounting for 59% of cases, followed by 21A Delta and 20I Alpha, each at 8%. In June 2021, 21J Delta continued to circulate abundantly, making up 54% of cases, followed by 20I Alpha at 23%. An upsurge in SARS-CoV-2 infections was observed in July 2021, predominantly driven by 21J Delta (50%), followed by 20A (21%), while 20I Alpha was detected in approximately 18% of patients. 21J Delta was still dominating in August 2021 (87%), September 2021 (91%), as well as in October 2021 (80%). Hence, the Delta 21J VOC was continuously the dominating VOC in Pakistan from May until October 2021. These results are summarized in Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 6.

Phylogenetic and mutational analyses

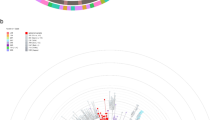

Our mutational analysis focused primarily on the Alpha and Delta variants, reflecting their prevalence in our dataset. We constructed phylogeny based on the country of origin of the samples, clades as well as lineages. Figure4 shows the phylogenetic affiliation of our sample set (915 samples; Pakistan_Group1) with other samples reported from Pakistan (2354 samples; Pakistan_Group2), India (2945 samples) and China (1270 samples). All these samples have been reported in the GISAID database. Attributes of these samples to clades and lineages is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. While we observed the expected constellation of mutations characteristic of these lineages, we also identified some less common mutations that may be of interest for further investigation. The phylogenetic analysis revealed distinct clustering of Alpha and Delta variants within Pakistan, with their temporal appearance coinciding with global emergence patterns of these variants. We observed some geographic clustering, particularly among samples from Peshawar and Islamabad, suggesting localized transmission chains. The tree structure also indicates a clear transition from Alpha to Delta dominance over time, consistent with our prevalence data (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Time-resolved phylogeny tree is used to show the association of our sample set (Pakistan_Group1) with other samples reported from Pakistan (Pakistan_Group2), India and China during the same time period. The tree comprises of 7484 samples taken from GISAID. Lineage attributes of the samples are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. Tree is shown here by web ( https://auspices.us ) software.

Mutational analysis was performed on 910 samples that were deposited in the GISAID database. Among these, the top 10 most mutated samples belonged to the Delta variant lineage AY.127 (Fig. 5). Most of the samples accumulated more than 20 mutations each, with some containing as many as 50 mutations. Interestingly, non-synonymous substitutions (SNPs) were the most frequent type of mutation. The most frequent polymorphisms were A23403G and C3037T. The most common protein mutation occurred in the Spike protein (D614G) in the dataset, followed by a mutation at the 106th position of NSP3 (Fig. 5).

Mutational analysis was done with 910 samples uploaded to GISAID and aligned. (a) 10 most mutated samples were from Delta variant lineage AY.127. The X-axis denotes the samples names while y-axis represents the number of mutations. The all 10 samples show the AY.127 pango lineage (b) Overall mutations per samples are represented, the x-axis shows the no. of mutations while y-axis represents the number of samples, indicating the distributions of mutations per sample. (c) Most frequent event observed was SNP: a change of one or more nucleotides, determining a change in amino acid sequence. SNP_silent: a change of one or more nucleotides with no effect in a protein sequence. Extragenic: a mutation affecting intergenic or UTR regions. Deletion: the deletion of three (or multiples of three) nucleotides, causing the removal of one or more amino acids to the protein sequence. Deletion_frameshift: the deletion of nucleotides not as multiples of three, causing a frameshift mutation. (d) The most frequent events per type. Individual mutation types are represented as nucleotide events. Cytosine to thymidine transitions (C > T) were the most abundant. (e) The most common events, either in nucleotide or aminoacidic coordinates. Four major mutations were observed; these mutations are A23403G (associated with D614G the mutation in the spike protein), C3037T, C14408T, and C241T. (f) The frequent mutations in proteins were abundantly present in spike protein S: D614G.

Discussion

Our study makes several significant contributions to understanding the genomic epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 in Pakistan. First, with 802 high-quality genomes, it represents the largest single sequencing effort in the country to date. Second, our sampling spans multiple cities, providing a more comprehensive national perspective compared to previous studies that focused on fewer locations. Third, our extended sampling period from March to October 2021 captures the critical transition from Alpha to Delta variant dominance. Lastly, we demonstrate the feasibility and utility of using the GridION platform for large-scale genomic surveillance in Pakistan, which could inform future public health strategies.

The majority of VOCs (Alpha and Delta) gained prominence in Pakistan during 2021 (Fig. 4). The analysis of Pakistani SARS-CoV-2 genomes reveals trends similar to those seen worldwide, with all VOCs tracing their origins to a common ancestor (Wuhan). However, despite these similarities, Pakistan experienced a lower number of COVID-19 cases and fatalities compared to its neighboring country, India. In 2021, a surge in infections was observed due to the emergence of new variants such as Alpha and Delta, which were linked to the third and fourth waves of infection in Pakistan. The third wave lasted for nearly four months, from mid-February to mid-June 2021. Following this, the country was hit by a fourth devastating wave from July to October 2021. This wave resulted in 314,786 infections and over 6000 deaths, further straining the already weakened healthcare system23.

Sampling was conducted in 2021, during the peak of the epidemic, when a large number of cases were reported. The Alpha variant was the primary driver of the third major wave of SARS-CoV-2 infections in the first half of 2021. However, in the latter half of 2021, the Delta variant became the most prevalent VOC of SARS-CoV-2. Our findings indicate that during the third wave of COVID-19, the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7 lineage) was the leading cause of infection. The rapid transmission rate contributed to the dominance of the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7 lineage)30 making it the most prevalent variant in local populations during the third wave in Pakistan, as it was globally. This spread in Pakistan is attributed to cross-border travelers during the period from December 2020 to February 202130. Subsequently, the Delta variant (21J) with its B.1.617.2 lineage became dominant during the fourth wave of spread in Pakistan. The phylogenetic analysis of 7,484 samples from Pakistan, India, and China revealed distinct clustering patterns suggesting multiple independent introductions of both Alpha and Delta variants into Pakistan. Geographic clustering was particularly evident among samples from major urban centers, with clear temporal stratification corresponding to wave dynamics. We also identified other lineages of the Delta variant, including AY.108, AY.127, AY.126, and AY.43. Notably, a significant number of AY.108 cases (n = 79/1052) were found in our study. Globally, only 885 cases of this lineage had been reported as of November 17, 2022, with approximately 34% (n = 299) of those cases originating from Pakistan32. The dominance of Delta variants has been associated with specific mutations, including P681H/R substitutions and additional mutations in the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene33. These mutations enhance the replication rate, contributing to a significant increase in the number of COVID-19 cases.

Phylogeographic analysis revealed distinct patterns of SARS-CoV-2 spread across Pakistan. The Alpha variant showed a Peshawar-centered introduction pattern, consistent with its timing during peak international travel restrictions and the city’s position as a major border crossing. In contrast, Delta variants demonstrated multiple introduction pathways primarily through Islamabad, reflecting the capital’s role as an international transportation hub.

The finding that Pakistan accounts for 34% of global AY.108 lineage cases suggests either preferential circulation conditions or specific introduction events that require further investigation. This highlights the importance of continued genomic surveillance in identifying regionally significant variants.

While robust epidemiological data collection remains the foundation of effective outbreak management, genomic surveillance provides complementary insights that enhance our understanding of pathogen evolution and transmission dynamics. In the context of Pakistan’s COVID-19 response, we strategically implemented genomic sequencing to maximize cost-effectiveness by focusing on representative sampling from some high-incidence areas during established outbreak waves. This approach allowed us to characterize circulating variants while acknowledging the resource constraints inherent in large-scale sequencing efforts. The integration of genomic data with traditional epidemiological indicators provided a more comprehensive picture of the outbreak than either approach alone, though we recognize that the cost-benefit equation of extensive sequencing varies by context and outbreak stage.

Our analyses reveal a higher number of mutations in the Delta variant lineage AY.127 (Fig. 5). Notably, this lineage has been linked to a hamster-specific origin, as it was originally transmitted to individuals working in hamster facilities in Hong Kong34,35. These findings underscore the importance of monitoring animal-human interactions to better understand the genetic diversity and epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2. We identified the highest number of mutations in the D614G mutation, located in the S-protein of SARS-CoV-2, which has been associated with increased transmission among humans. This mutation not only enhances the incorporation of the functional S-protein into SARS-CoV-2 virus-like particles (VLPs) but also improves the infectivity of retroviral pseudoviruses (PVs)36. The rapid rate of mutations observed in our study suggests that the risk of another outbreak cannot be entirely ruled out, making continuous monitoring and surveillance imperative to prevent further spread of the virus. Our study demonstrates the feasibility and importance of large-scale genomic surveillance in Pakistan. Ongoing monitoring will be crucial for the early detection of new variants and to inform public health responses, including potential updates to vaccine strategies. Additionally, the study highlights the utility of nanopore sequencing, which could be an affordable option for many labs involved in viral surveillance.

Study limitations

We acknowledge a few limitations in our study. The geographical and temporal distribution of our samples was not uniform, with a higher proportion coming from Islamabad and Peshawar, and some temporal skew in sampling between locations. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to other regions or specific time points. Additionally, like many genomic surveillance efforts, our sampling was biased toward PCR-positive cases and may not fully represent mild or asymptomatic infections. Despite these limitations, the consistency of our findings with broader trends observed in Pakistan and globally suggests that our data accurately captures the key features of SARS-CoV-2 evolution during this critical period. This assertion is supported by Supplementary Fig. 1, which shows that incorporating additional genomes from Pakistan within the same sampling timeframe did not significantly alter the topology of the phylogenetic tree.

Technical limitations

The ARTIC amplicon-based protocol, while effective for SARS-CoV-2 surveillance, can result in uneven coverage due to amplicon dropout in regions with primer binding site mutations, limited detection of large structural variants due to ~ 400 bp amplicon size constraints, primer bias leading to potential underrepresentation of certain variants, and coverage gaps in specific genomic regions resulting in ambiguous nucleotide calls. Oxford Nanopore Technology limitations include higher per-read error rates compared to short-read sequencing (particularly in homopolymer regions), systematic biases affecting certain sequence contexts, significant quality variability within and between sequencing runs, and substantial computational requirements for real-time base-calling and consensus generation, although many of these limitations have been addressed in the recent upgrades in ONT Technologies (both hardware as well as software, including base-calling). Data analysis was constrained by limiting phylogenetic reconstruction to high-quality sequences, potentially excluding important evolutionary information from lower-quality samples. Despite our extended sampling period, temporal gaps may have resulted in missing intermediate evolutionary steps or brief circulation of minor variants. These limitations primarily affect the precision of our estimates rather than overall conclusions, and were mitigated through conservative quality control measures, statistical validation approaches, and consistency checking with global datasets.

Future genomic surveillance efforts in Pakistan would benefit from systematic temporal sampling and quantitative phylogeographic analysis to further elucidate transmission dynamics between cities and provinces.

Data availability

All the sequences generated in this study are submitted to the GISAID that are available at https://gisaid.org/ under the virus names (hCov-19/Pakistan/KRISS0002 to hCov-19/Pakistan/KRISS1052) and Accession ID (EPI_ISL_15171526 to EPI_ISL_15172344).

References

WHO. World Health Organization. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard (2024).

Kim, D. et al. The architecture of SARS-CoV-2 transcriptome. Cell 181, 914–921e10 (2020).

Cella, E. et al. SARS-CoV-2 lineages and sub-lineages circulating worldwide: A dynamic overview. Chemotherapy 66, 3–7 (2021).

World Health Orginization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. (2022). https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/

Volz, E. et al. Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Nature 593, 266–269 (2021).

Tegally, H. et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature 592, 438–443 (2021).

Faria, N. R. et al. Genomics and epidemiology of the P.1 SARS-CoV-2 lineage in Manaus, Brazil. Science 372, 815–821 (2021).

Vaidyanathan, G. Coronavirus variants are spreading in India—what scientists know so far. Nature 593, 321–322 (2021).

Harvey, W. T. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19(7), 409–424 (2021).

Ramanathan, M., Ferguson, I. D., Miao, W. & Khavari, P. A. SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.7 and B.1.351 spike variants bind human ACE2 with increased affinity. Lancet Infect. Dis. 21, 1070 (2021).

Mandal, N., Padhi, A. K. & Rath, S. L. Molecular insights into the differential dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. J. Mol. Graph Model. 114, 108194 (2022).

Duong, D. Alpha, Beta, Delta, Gamma: What’s important to know about SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern? CMAJ 193, E1059–E1060 (2021).

Ladner, J. T., Grubaugh, N. D., Pybus, O. G. & Andersen, K. G. Precision epidemiology for infectious disease control. Nat. Med. 25, 206–211 (2019).

Gardy, J. L. & Loman, N. J. Towards a genomics-informed, real-time, global pathogen surveillance system. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19(1), 9–20 (2017).

Baize, S. et al. Emergence of Zaire Ebola virus disease in Guinea. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1418–1425 (2014).

Ksiazek, T. G. et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 348, 1953–1966 (2003).

Zaki, A. M., van Boheemen, S., Bestebroer, T. M., Osterhaus, A. D. M. E. & Fouchier, R. A. M. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 1814–1820 (2012).

Grubaugh, N. D., Faria, N. R., Andersen, K. G. & Pybus, O. G. Genomic insights into Zika virus emergence and spread. Cell 172, 1160–1162 (2018).

Jain, M., Olsen, H. E., Paten, B. & Akeson, M. The Oxford nanopore MinION: Delivery of nanopore sequencing to the genomics community. Genome Biol. 17(1), 1–11 (2016).

Quick, J. et al. Real-time, portable genome sequencing for Ebola surveillance. Nature 530(7589), 228–232 (2016).

Quick, J. et al. Rapid draft sequencing and real-time nanopore sequencing in a hospital outbreak of Salmonella. Genome Biol. 16(1), 1–14 (2015).

Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Bollas, A., Wang, Y. & Au, K. F. Nanopore sequencing technology, bioinformatics and applications, Nat. Biotechnol. 39(11), 1348–1365 (2021).

Covid.gov.pk. COVID-19 health advisory platform by ministry of national health services regulations and coordination. https://covid.gov.pk/

Basheer, A. & Zahoor, I. Genomic epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2 divulge B.1, B.1.36, and B.1.1.7 as the most dominant lineages in first, second, and third wave of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Pakistan. Microorganisms 9, 2609 (2021).

Umair, M. et al. Genomic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 in Pakistan during the fourth wave of pandemic. J. Med. Virol. 94, 4869–4877 (2022).

Hadfield, J. et al. Nextstrain: Real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 34, 4121–4123 (2018).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. I. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

Nguyen, L. T., Schmidt, H. A., Von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Mercatelli, D., Triboli, L., Fornasari, E., Ray, F. & Giorgi, F. M. Coronapp: A web application to annotate and monitor SARS-CoV-2 mutations. J. Med. Virol. 93, 3238–3245 (2021).

Lyngse, F. P. et al. Increased transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 by age and viral load. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–8 (2021).

Nasir, A. et al. Evolutionary history and introduction of SARS-CoV-2 alpha VOC/B.1.1.7 in Pakistan through international travelers. Virus Evol. 8, veac020 (2022).

Alaa Abdel, L. et al. &. AY.108 lineage report.outbreak.info. Accessed November 21 (2022). https://outbreak.info/situation-reports?pango=AY.108%26loc%3DIND%26loc%3DGBR%26loc%3DUSA%26selected&selected=PAK&loc=USA&loc=USA_US-CA&loc=PAK&overlay=false.

Tan, C. W. et al. Pan-sarbecovirus neutralizing antibodies in BNT162b2-Immunized SARS-CoV-1 survivors. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1401–1406 (2021).

Yen, H. L. et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 delta variant (AY.127) from pet hamsters to humans, leading to onward human-to-human transmission: A case study. Lancet 399, 1070–1078 (2022).

Tong, C., Shi, W., Siu, G. K. H., Zhang, A. & Shi, Z. Understanding spatiotemporal symptom onset risk of Omicron BA.1, BA.2 and hamster-related Delta AY.127. Front. Public Health 10, 978052 (2022).

Zhang, L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike-protein D614G mutation increases virion spike density and infectivity. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–9 (2020).

Funding

This research was supported by a National Research Council of Science and Technology Grant by the Ministry of Science and ICT (CRC-16‐01‐KRICT and Global-22-014). This research was also supported by the “Establishment of measurement standards for microbiology,” Grant No. GP2023-0006-11, “Development of Rapid Diagnosis of Rift Valley Fever Virus based on Whole Genome Analysis,” Grant No. HI20C0558, and “Development of Rift valley fever virus RNA reference materials,” Grant No. 20015205, funded by the Korea Research Institute of Standards and Science, Ministry of Health and Welfare, and Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy. This work was also supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea and funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2022K1A4A8A02077396 and RS-2023-00223245).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.U.H. carried out Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original Draft, Visualization. M.P. carried out Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation. D.P. carried out Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation. H.A. carried out Analysis, Visualization. I.A. carried out Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation. N.B. carried out Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation. A.A. carried out Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation. M. S. carried out Sampling, Resources, Data Curation. M.U. carried out Methodology, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation. H.A.M. carried out Sampling, Data Curation. A.A. carried out Sampling, Data Curation. M.M. carried out Sampling, Data Curation. F.F. carried out Sampling, Data Curation. S.B. carried out Sampling, Data Curation. M.I. carried out Sampling, Data Curation. Y.M.Y. carried out Sampling, Data Curation. S.S. carried out Sampling, Data Curation. M.Z. carried out Sampling, Data Curation. Z.H. carried out Sampling, Data Curation. S.K. provided the overall directions for the research, Conceptualization, Resources, Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision, Project administration, and Funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, Z., Park, M., Park, D. et al. Nanopore sequencing reveals the genomic diversity of the variants of concern of SARS-CoV-2 during 2021 disease outbreak in Pakistan. Sci Rep 15, 28129 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12774-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12774-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Process and analytical strategies for the safe production of mRNA vaccines and therapeutics

Molecular Biology Reports (2026)