Abstract

Thoracolumbar kyphosis (TLK) secondary to Scheuermann’s disease often leads to low back pain, which may be related to altered biomechanical properties of the spine. However, There is a lack of biomechanical studies in the literature that comprehensively evaluate tissue-level stresses and strains in the thoracolumbar spine affected by Scheuermann’s kyphosis, particularly during functional motions such as forward flexion. This study analyzed biomechanical changes during forward flexion in TLK patients using musculoskeletal dynamics and finite element modeling. Twenty TLK patients and twenty healthy individuals were recruited. Kinematic data (joint angles), kinetic data (joint reaction forces and moments), and electromyographic (EMG) data were collected at different bending angles using Vicon 3D motion capture and surface electromyography. Physiologic motions captured from in vivo experiment was simulated using OpenSim, with inverse dynamics and optimization used to calculate vertebral joint angles, muscle forces, and intervertebral reaction forces, serving as boundary conditions for ANSYS finite element models. Subject-specific finite element models for both groups were constructed in ANSYS using computed tomography (CT) DICOM files. The CT-based finite element models were used to compute von Mises stress distributions—a mechanical parameter indicating combined tissue stress and potential risk of overload—in the vertebral body, intervertebral discs, and articular cartilage at different forward flexion angles under the applied loadig conditions. At different forward bending angles, TLK patients exhibited high stress distribution in the L1-S1 segment vertebral articular processes. Compared with healthy individuals, the stress distribution in the S1 segment was uneven, with peak stress reaching up to to 2.8 times higher (180% increase) than that of healthy individuals. TLK patients exhibit stress concentration in the annulus fibrosus region of the intervertebral disc, while the stress distribution in the nucleus pulposus region is relatively uniform. The peak stress in the intervertebral disc during different movements can be up to 2.33 times higher (133% increase) than in healthy individuals. In TLK patients, stress concentration was observed in the articular cartilage of all segments except for the L5/S1 segment. The peak stress in the articular cartilage during different movements was up to 12.02 times higher (1,102% increase) than in healthy individuals. These results suggest that TLK patients experience elevated and uneven spinal tissue stress during forward flexion, which may contribute to increased risk of degeneration and back pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Scheuermann’s disease is a structural kyphotic deformity of the thoracic or thoracolumbar spine, characterized by a rigid and non-correctable curvature, with a prevalence of 1%−8%1. Thoracolumbar kyphosis (TLK) is a common symptom of Scheuermann’s disease which not only affects posture and appearance, but is also the most important pathologic modifier of low back pain in adolescence2. Patients with TLK have 2.5 times the risk of having lower back pain and 2.6 times the risk of being unable to live a normal life due to lower back pain within 5 years3. The mechanisms associated with lower back pain due to TLK remain unclear. Mechanical factors are one of the pathogenic mechanisms of TLK4. The kyphosis affects the sagittal alignment of the vertebrae and alters the line of gravity, resulting in elevated pressure on the vertebrae and surrounding soft tissues, which in turn increases the risk of secondary low back pain5. High rates of pain in TLK patients may also relate to spinopelvic instability6 and compensatory lumbar hyperlordosis, which induces muscle fatigue7. The negative gravity line in the sagittal position after a posterior convex deformity in patients with TLK changes accordingly, which leads to abnormal stress effects on structures, such as the vertebral body and attached soft tissues, the increased risk of lower back pain and other injury symptoms. However, despite various hypotheses suggesting that TLK alters the biomechanical properties of the spine and contributes to lower back pain, there is currently a lack of direct biomechanical evidence to substantiate these claims.

Finite element modeling (FEM) enables the simulation of the response of complex spinal biomechanical structures under various loading conditions and provides a strong technical support for clinical studies of TLK deformity8. However, while earlier FEM often relied on simplified loading scenarios and lacked dynamic realism, more recent studies—including those by Hadagali et al. (2024) at the University of Waterloo-have demonstrated that finite element models can realistically simulate complex physiologic motions, particularly in the head and neck regions, using in vivo-based kinematics and validated boundary conditions9,10. In spine biomechanics research, the approach of musculoskeletal modeling coupled with finite elements has gradually gained popularity. This coupled model is used to analyze the stress–strain distribution of hard and soft tissues in the model using the joint force and muscle force output from the musculoskeletal model as loading boundary conditions to further evaluate the internal mechanical response of the musculoskeletal system11,12,13. Rajaee et al.14 compared the intervertebral disc pressures predicted by the coupled model during torso forward flexion with human experimental data measured via an in vivo pressure transducer through the construction of a coupled spinal musculoskeletal–finite element model. The results showed a high concordance between the two with a coefficient of determination (R²≌0.97) and a root mean square error (RMSE≌ 0.14 MPa) at the L4-L5 level. This method holds promise for applications such as surgical planning, injury management, and personalized spinal analysis.

Due to the relative rarity of TLK resulting from Scheuermann’s disease, recruiting sufficient patient participants and obtaining comprehensive biomechanical data are challenging, which has limited the number of in-depth biomechanical studies in this population. While numerous finite element models of the spine exist, there is a lack of validated, patient-specific FEMs focused on Scheuermann’s kyphosis that incorporate realistic physiologic motions and individualized loading conditions, which limits their clinical applicability. This study combines in vivo motion capture and EMG data from TLK patients to build subject-specific musculoskeletal models, which are then used to generate individualized muscle and joint forces for driving CT-based finite element models, thereby achieving more physiologically realistic simulations tailored to this specific patient population. While many spinal FEM studies use generic loading conditions such as standard flexion or extension postures15, our approach applies subject-specific, experimentally captured forward flexion motion and forces to simulate more realistic biomechanical conditions in TLK patients. Previous studies have shown that movement of the spine in the sagittal plane often results in higher stresses borne on the small joints16. And forward bending at different angles tends to cause regular changes in lower back loading17. Dandumahanti et al. used 0°, 15°, 30°, 45° and 60° for biomechanical analysis of forward flexion of the cervical segment of the spine18. In this study, we applied an integrated musculoskeletal–finite element modeling approach to investigate spinal loading in patients with thoracolumbar kyphosis (TLK) during forward flexion at 30°, 60°, and 90°. Although this modeling strategy has been used in other spinal disorders, its application to TLK remains scarce, and our study aims to fill this knowledge gap by capturing subject-specific biomechanical responses across a range of functional postures.

In summary, objective data on musculoskeletal risk factors for low back pain in TLK patients is limited. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to apply a coupled musculoskeletal-FEM simulation framework using subject-specific motion data to evaluate biomechanical responses in Scheuermann’s thoracolumbar kyphosis during forward flexion. This integrated approach provides new insights into external load patterns and internal tissue stress distribution in TLK patients, which is critical for clinical planning and risk assessment.

Methods

Participants

Twenty TLK patients and twenty asymptomatic individuals were recruited. There were no statistical differences between the two groups in terms of general demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, height, weight and body mass index (BMI) (Table 1). Inclusion criteria: (1) TLK diagnosis or absence of thoracolumbar kyphosis; (2) no thoracolumbar fracture, scoliosis, lumbar disc herniation, spondylolisthesis, spinal stenosis, infection, tumor, or other spinal disorders; (3) no history of lower-extremity injuries. Exclusion criteria: (1) major systemic or congenital diseases (e.g., cardiopulmonary disease, diabetes, osteoporosis); (2) intense physical activity within 24 h before testing. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital with Nanjing Medical University and followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for participation and publication of anonymized data and images in an online open-access journal. All procedures were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data collection

Data were collected using a 3D motion capture system. A static trial was conducted with 50 passive reflective markers placed on anatomical landmarks: spinous processes of C7, T3, T6, T9–T12, L1, L2; bilateral acromion, medial/lateral elbows and wrists; xiphoid process; posterior and anterior superior iliac spines; greater trochanters; medial/lateral femoral condyles; medial/lateral malleoli; heels; and first and fifth metatarsals. Additional tracking markers were placed near T10, T12 and L2 (Fig. 1).

3D Motion capture data acquisition schematics. The trajectories of markers were captured during the landing process by 12 Vicon motion capture cameras (100 Hz, Vicon Motion Analysis Inc., Vantage 5, Oxford, United Kingdom). Two fully integrated three-dimensional force platforms (1000 Hz, AMTI, Watertown, Massachusetts, United States) synchronously captured the dynamic ground-reaction force signal with the motion capture system. Raw EMG signals from the erector spinae near the T11, T12, L2, and L3 vertebrae were acquired by a synchronized FIEXCOMP-type wired surface EMG analyzer feedback instrument (14bits, 512 Hz, 2048 samples/second, Thought Technology Ltd., Quebec, Canada).

Prior to testing, subjects stood upright on two ergometers. They were then instructed to tilt forward to 30°, 60°, and 90°, holding each position for 3 s at the lowest point.

Data analysis

Demographic data were presented as Mean ± Standard Deviation (Mean ± SD). Independent samples t-tests were used to compare continuous variables (e.g., age, height, weight, and BMI) between groups, while the chi-square test was applied to categorical variables (e.g., sex). A significance level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests. The kinematics and dynamics data of the trials were filtered using a low-pass filter (Butterworth 4th order) and run with a cutoff frequency of 10 Hz19 for the motion capture system and 100 Hz20 for force signal. The electromyography (EMG) signals were normalized to their peak filtered value for each trial for each participant. EMG signals were band-pass filtered, rectified, and low-pass filtered to obtain the linear envelope, then normalized by dividing each muscle’s signal by its peak value across all trials for that participant. This yielded normalized muscle activity ranging from 0 (no activity) to 1 (maximum activity), which was compared to the predicted activation (0–1 scale) from the musculoskeletal model. Kinematic data, kinetic data and EMG data are presented as mean values. The above steps were completed in MATLAB (MATLAB R2018a, The MathWorks, MA, United States) software.

Musculoskeletal simulation and coupled finite element modeling

This study was based on the Christophy lumbar spine model in OpenSim 4.1 (OpenSim, Stanford, California, United States), and was refined by integrating upper body components (C7-T9 vertebrae, sternum, ribs, cranial bones) from Marco’s model and lower-limb segments from the Full-Body Lumbar Spine (FBLS) model21,22. Key muscle definitions and parameters were also adopted from Marco’s model, with modifications to iliac rib (IL), longest piriformis (LTPT), and multifidus (MF) muscles to match the Christophy model’s dimensions. Full details are provided in Supplementary Material 1 (Appendix A). Muscle forces were estimated at discrete flexion angles (30°, 60°, and 90°) using OpenSim’s static optimization tool. Time-varying muscle activations were not computed in this study, as our goal was to capture representative loading conditions at specific postures for subsequent finite element modeling. Simulation analysis of lumbar flexion movement was performed based on the established musculoskeletal model. To ensure that the OpenSim model is accurately coupled with the finite element model, we used scaling techniques to adjust the model. First, the geometric features of the spine of the TLK patient were extracted based on the CT image data, including the shapes and sizes of the vertebral bodies, intervertebral discs, and articular cartilage, etc. The geometric parameters of the OpenSim model were matched with these features, and the overall size of the model was adjusted by scaling to fit the actual anatomical structure of the patient. Second, the muscle attachment points in the OpenSim model were repositioned and adjusted according to the specific anatomical structure of the patient. Through the scaling technique, the muscle attachment points were precisely placed in geometric positions corresponding to the actual muscle attachment locations of the patient to ensure that the muscle force transmission paths corresponded to the actual physiological conditions. Finally, the force arm length attributes of the muscles are recalculated based on the scaled geometric model. By adjusting the moment arm length of the muscle to match the geometry of the scaled model, we ensure that the moments generated by the muscle at different joint angles are consistent with the actual physiological and mechanical behavior. Through the above scaling technique, we effectively reduce the geometric and mechanical errors when coupling OpenSim with the finite element model, and improve the accuracy and reliability of the model. The details of simulation and modeling of musculoskeletal dynamics are given in Supplementary Material 1 (Appendix A).

The average values of joint angles, muscle forces and joint reaction forces of the two groups of participants (20 cases each in the TLK and control groups) were calculated based on OpenSim and loaded into the finite element model as boundary conditions. Outliers—defined as values exceeding 1.5 interquartile ranges from the median—were excluded to ensure representative inputs. While the model was scaled to each participant’s anthropometry to reflect subject-specific segment lengths and muscle attachment locations, the intrinsic muscle-tendon properties and joint stiffness parameters were retained from the validated generic model. This approach ensures comparability and avoids introducing uncertainties due to the lack of subject-specific in vivo muscle parameter measurements.

One participant from the TLK group (age: 26, height: 178 cm, weight: 82 kg, TLK angle: 16°), whose kyphosis angle closely represented the group average, was deliberately selected to ensure that the case analysis reflected typical patient characteristics. A control participant (age: 30, height: 180 cm, weight: 83 kg) with similar demographics was then chosen to minimize confounding factors. Musculoskeletal modeling coupled with finite element analysis was performed on these two individuals. While this case-based approach may limit generalizability, it reduces model oversimplification, controls external variables, and enables in-depth analysis. Preprocessing steps for finite element modeling were completed prior to simulation Supplementary Material 1 (Appendix B).

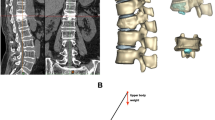

The 3D finite element mesh of the vertebral body, intervertebral discs, and endplates is shown in Fig. 2. Material properties, including Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and cross-sectional area, are listed in Table 223,24,25. Static simulations were conducted in ANSYS 19.0 (ANSYS, Ltd, USA) for 30°, 60°, and 90° lumbar flexion. Hip flexion angles from OpenSim inverse kinematics were used as displacement boundary conditions, reflecting the hip’s primary role in forward flexion. Muscle forces of the iliac rib (IL), longest piriformis (LTPT), and multifidus (MF), estimated via OpenSim, were applied as loading conditions. The sacral S1 surface was fully constrained to restrict translation and rotation along all axes. Preloads were applied along the X and Z axes on the T8 vertebral surface to simulate vertical compression and lateral shear. A physiologically realistic preload of 500 N was applied vertically (Z-axis) to simulate upper body weight. Anterior shear force in the X-axis was also applied based on joint reaction forces derived from musculoskeletal simulation data across 40 participants, reflecting realistic forward bending conditions. These loading magnitudes and directions were chosen in accordance with previous biomechanical literature and to replicate in vivo lumbar spine loading patterns. Finally, IL, LTPT, and MF forces were applied to spinous processes, pedicles, and vertebral surfaces (Fig. 3), and von Mises stress distributions were computed under each bending condition. Stress, in this study, refers specifically to von Mises stress (σ_vm), a scalar quantity derived from the stress tensor and widely used in solid mechanics to assess yielding criteria in ductile materials. It provides an estimate of the intensity of internal forces per unit area acting within a deformable body under load26. The von Mises stress (σ_vm), also known as Huber–von Mises stress, was computed in ANSYS based on the following equation:

Schematic diagram of finite element model construction. (a). 3D reconstruction model of the spine; (b). model of the intervertebral discs, upper and lower cartilage endplates and endplates; (c). surface fitting and solid model of the spinal T8-S1 segment; (d). vertebral body mesh delineation model; (e). 3D finite element body mesh model of the T8-S1 segment.

where σ1, σ2, and σ3 correspond to the principal stresses extracted from the finite element model for each cell.This method can effectively reflect the equivalent stress level of the material under complex stress conditions, which provides an important basis for studying the biomechanical behavior of spinal structures in TLK patients. Von Mises stress was used to provide a scalar measure of the equivalent stress magnitude for visualization and comparative analysis. Although bone is an anisotropic material, von Mises stress is commonly adopted in spinal biomechanics studies27,28 to enable regional comparisons of stress concentration and distribution patterns under multi-directional loading.

Mesh convergence analysis

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the finite element modeling results, we performed a mesh convergence validation. By testing three different element sizes, 1 mm, 1.5 mm and 2 mm, it is found that the von Mises stress error decreases from 5 to 2% when the element size is reduced from 2 mm to 1 mm, which indicates that the mesh density has a significant effect on the calculation results(Table 3). Based on this, 1 mm is finally chosen as the main element size, and the model contains about 1,353,323 nodes and 882,698 elements, and the calculation results are stable and the accuracy meets the research requirements.

Model validation

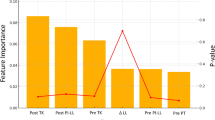

To verify the accuracy of the OpenSim simulation results, we compared the simulated erector spinae (IL + LTPT) muscle activation levels with surface EMG data for 30°, 60°, and 90° lumbar flexion postures. We also extracted the peak hip joint angles, muscle forces of the erector spinae and multifidus (MF), and T7/8 segment reaction forces for use as boundary conditions in the finite element model (Fig. 4a–d). In addition, to validate the accuracy of the OpenSim model, we performed a Pearson’s correlation coefficient analysis between the EMG data and the muscle activation calculated by OpenSim.

For the finite element model, the boundary and loading conditions were defined as follows: (1) the bilateral auricular surfaces of the sacrum were constrained; (2) a vertically downward preload of 500 N was applied to the superior endplate of L1, and a 7.5 Nm torque was applied to induce flexion, extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation. Lumbar segmental range of motion (ROM) was then calculated under these load conditions using the Ansys solution module.

Results

Model validation

The OpenSim simulation results showed that the peak erector spinae (IL + LTPT) activation levels at 30°, 60°, and 90° of lumbar flexion were consistent with the corresponding peaks in surface EMG data, supporting the accuracy of the musculoskeletal model (Fig. 4a). The hip joint angles at each flexion angle were also in line with expected kinematic patterns (Fig. 4b). During 30–90 degrees of forward flexion, iliac rib muscle peak stress was 300 N ~ 520 N, longest piriformis muscle peak stress was at 600 ~ 520 N, and multifidus muscle peak stress was at 380 ~ 500 (Fig. 4c). The T7/8 segmental reaction forces used as input to the FE model ranged from 160 N to 300 N across flexion conditions (Fig. 4d). The correlation analysis between the EMG data and the muscle activation calculated by OpenSim showed that the correlation coefficient calculated for the 60° group was 0.87, with a p-value of less than 0.01, indicating that there was a significant positive correlation between the two; and the correlation coefficient calculated for the 90° group was 0.95, with a p-value of less than 0.01, indicating that there was a significant positive correlation between the two. However, the correlation was not strong in the 30° forward body flexion exercise condition, with a correlation coefficient lower than 0.6, which may be related to the complex physiological properties of the muscle or the simplification of the model. This result generally indicates that the OpenSim model is able to simulate muscle activities better and is highly consistent with the actual EMG data, thus validating the reliability of the model.

The effectiveness of the finite-element model was validated through comparison of the model validation finding with the range of motion (ROM) results of the lumbar spine under various working conditions in classical biomechanical studies29. As shown in Table 4, the ROM predictions for flexion, extension, lateral bending, and axial rotation were within the physiological range reported in the literature, confirming the reliability of the FE model for biomechanical analysis.

Results of stress analysis

Vertebral stress analysis

At different forward flexion angles, the stress of L1-S1 in both TLK patients and healthy subjects showed an increasing trend, and the S1 stress in TLK patients was significantly higher than that in healthy subjects at 60 degrees and 90 degrees of forward flexion, which were 45.0 and 41.0 MPa, respectively, and 2.06 and 2.8 times higher than that of the healthy subjects (Fig. 5). Detailed vertebral stress results at different angles are shown in Supplementary Material 2 (Table S1).

The vertebral stress cloud revealed a high stress distribution in the superior articular process position of the L1-S1 segments of the TLK patients during the 30°, 60°, and 90° forward flexion. Compared with healthy individuals, the stress distribution in the S1 segment of TLK patients showed greater asymmetry and regional concentration, particularly in the posterior elements and superior endplate. The vertebral stress cloud demonstrated qualitatively higher stress concentration at the articular eminence regions of the L1–S1 segments in TLK patients during 30°, 60°, and 90° forward flexion. Compared with healthy individuals, the stress distribution in the S1 segment of TLK patients was more asymmetric and heterogeneous Supplementary Material 1 (Appendix C).

Disc stress analysis

Stress analysis showed that at 30° flexion, TLK patients had stress concentrated in the left annulus fibrosus of the T12/L1 disc, with no significant stress in controls. At 60°, stress localized beneath the right nucleus pulposus in both groups, but TLK patients exhibited twice the stress levels. At 90°, stress focused above the fibrous ring in both groups, with TLK patients showing 1.35 times higher stress. In the L1/2 segment, TLK patients had stress in the lower annulus fibrosus at 30° and 60°, with peak values 2.33 and 2.1 times those of controls. At 90°, stress remained in the lower annulus but showed no marked group difference. In L5/S1, stress appeared in the bilateral upper annulus fibrosus, with TLK patients showing 1.28 and 1.32 times higher peak stresses at 30° and 60°, respectively.

At 90° of forward flexion, TLK patients exhibited stress concentration at the left lower annulus fibrosus, with peak stress about 2.06 times higher than in healthy subjects. While stress distribution in the L2-L5 discs did not differ significantly between the two groups. TLK patients had consistently higher stress values, ranging from 1.07 to 1.69 times higher. Significant stress concentrations were observed in the annulus fibrosus at the T12/L1, L1/2, and L5/S1 segments, with peak stresses up to 2.33 times higher than in healthy subjects. These findings suggest that abnormal stress in TLK patients may accelerate degenerative disc lesions and annulus fibrosus damage, potentially leading to disc herniation and increased risk of low back pain (Fig. 6and Supplementary Material 1 (Appendix D)). Detailed disc stress results at different angles are shown in Supplementary Material 2 (Table S2).

Articular cartilage stress analysis

The articular cartilage stress cloud maps (Supplementary Material 1 (Appendix E)) unveiled that during the 30° lumbar flexion, higher peak articular cartilage stresses were observed in all segments in patients with TLK than in healthy individuals, except the L4/5 (disc-4) segment. During 60° lumbar flexion, higher peak articular synchondral cartilage stresses were detected in all segments in patients with TLK than in healthy patients except the L5/S1 segment (disc 5). Under 90° lumbar flexion, the peak stress of the articular process cartilage in all segments of TLK patients was higher than that in healthy individuals.

Figure 7 reveals that the peak stress in the articular cartilage of the L1/2 (disc 2) segment reached 2.57 MPa in healthy persons at 30° body pronation and 30.89 MPa in TLK patients, which is 12.02 times higher than that of healthy persons. At 90° forward body flexion, compared with healthy individuals, the peak cartilage stress in the L5/S1 segment (disc 5) of the articular eminence was approximately 1.25 and 9.2 times higher in TLK patients and in the L2/3 (disc 2) segment, respectively.

Discussion

This study was the first to establish a personalized musculoskeletal dynamics model for patients with TLK and to analyze the differences in biomechanical properties of the spine and its attached soft tissues between TLK patients and healthy individuals at different forward flexion angles. Our findings provide insight into why TLK patients are more prone to spinal degeneration and low back pain, by exploring the internal loading behavior of the vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and articular cartilage. In this study, the term ‘stress’ specifically refers to von Mises stress, a widely accepted scalar quantity in solid mechanics that reflects the intensity of internal forces and is commonly used to assess the risk of material yielding under complex loading conditions.

Studies show that forward flexion increases spinal loading, with greater angles further elevating vertebral and muscle loads30. At the L1–L4 segments, stress distribution was similar between TLK patients and healthy controls, likely due to preserved vertebral alignment and load-sharing capacity in these mid-lumbar segments. The relative structural symmetry and less pronounced influence of thoracolumbar curvature in this region may help maintain normal mechanical load paths. However, differences became evident at L5 during 60° and 90° forward flexion, which may be attributed to the increased demand for pelvic compensation in TLK patients. The excessive posterior pelvic tilt and altered sacral alignment during deep flexion likely change the lumbosacral angle and shift load concentrations to the inferior lumbar vertebrae. This mechanical adaptation may explain the more localized and asymmetric stress in the superior articular processes and pedicle plates in TLK patients. In contrast, healthy individuals maintained a more balanced posture with consistent curvature, resulting in more uniform stress distribution across load-bearing structures. The uneven stress patterns in TLK patients may signal early degenerative risk due to repetitive, localized overloading of facet joints and surrounding bone. Bridwell et al.31found that lumbar facet joints are crucial for stress transmission, and prolonged high stress can cause degeneration. Thus, abnormal stress in TLK patients’ superior articular processes may impair spinal function and increase degeneration risk.

In the S1 segment, stress distribution differed significantly between TLK patients and healthy individuals. In healthy subjects, stress concentrated at the articular eminence, while in TLK patients, it was more localized to the medial eminence, with peak stresses2.06, and 2.8 times higher at 60°, and 90° forward flexion, respectively. The increased asymmetry and regional concentration of stress observed in the S1 segment of TLK patients may be related to pelvic retroversion and compensatory sacral alignment in response to thoracolumbar kyphosis. These compensations alter load transmission through the lumbosacral junction, potentially leading to non-uniform stress distributions and increased risk of local degeneration. TLK patients also showed more concentrated stress in the T12-L5 articular cartilage at all angles, with peak stresses up to 12.02 times higher than in healthy subjects. Over time, this may lead to bone resorption, cartilage degeneration, and damage to articular surfaces, causing localized pain.

Stress on the articular cartilage (T12–L5) was markedly elevated in TLK patients, up to 12-fold higher at certain segments. The increased loading may result from greater posterior shear forces due to kyphotic curvature and altered joint orientation. Over time, such stress may impair cartilage integrity, triggering subchondral bone remodeling and facet joint arthritis. This provides a plausible explanation for the higher incidence of facet-mediated pain in kyphotic populations. In TLK patients, increased thoracolumbar kyphosis elevates disc tension, exacerbating herniation and spinal cord compression32, aligning with our findings. In this study, disc stress distribution patterns also differed between groups. In TLK patients, the annulus fibrosus in T12/L1, L1/2, and L5/S1 segments experienced significantly elevated and directionally skewed stress under flexion—often exceeding double that of healthy controls. These mechanical loads likely stem from the forward displacement of the upper trunk and increased flexion torque in TLK spines. Over time, excessive annular loading may lead to radial tears, accelerated degeneration, and herniation, especially in the upper lumbar segments where stress peaks were most pronounced. Our results suggest that abnormal spinal curvature in TLK alters the orientation of compressive vectors and shifts bending moments away from physiologic axes. This causes certain anatomical regions (e.g., posterior annulus, facet joints, and superior endplates) to bear disproportionate load. These stress concentrations may not only accelerate mechanical fatigue but also initiate inflammatory cascades, contributing to chronic pain.

The findings highlight the importance of early intervention in TLK patients. Therapeutic strategies should target restoring sagittal alignment and reducing compensatory pelvic tilt to offload vulnerable structures. Additionally, understanding the localized stress risks can inform surgical planning and rehabilitation strategies aimed at preserving disc and joint health.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the small sample size, due to the relative rarity of TLK secondary to Scheuermann’s disease, may limit the generalizability of the findings and the robustness of statistical analyses. While such sample sizes are common in biomechanical research due to the complexity and resource intensity of motion capture and musculoskeletal modeling, they may affect the validity of assumptions underlying certain parametric tests (e.g., the central limit theorem). Future studies with larger cohorts are recommended to enhance statistical power and generalizability. Second, certain anatomical and biomechanical assumptions-such as homogeneous material properties, simplified ligament and facet joint modeling, and quasi-static loading-may not fully capture the complexity of spinal biomechanics in pathological conditions. Third, EMG signal normalization relied on prior studies, as full MVC data were not collected, potentially affecting accuracy in assessing full muscle activation. While this approach may introduce some variability in the absolute quantification of muscle activation levels, it remains a valid method for relative comparisons within and between subjects under standardized task conditions. Importantly, our study focuses on comparing normalized muscle activation patterns rather than absolute activation magnitudes. Thus, despite the absence of MVC normalization, the methodology reliably captures relative changes and trends in muscle activity across different lumbar flexion angles and between healthy and TLK groups. Fourth, Although the finite element model was validated using segmental range of motion, internal metrics such as intradiscal pressure and facet joint loads were not compared to in vivo or cadaveric benchmarks. Future studies incorporating these parameters could provide additional validation of model fidelity. Fifth, the models focused on sagittal-plane postures and did not consider dynamic or multiplanar movements commonly experienced in daily life. Lastly, individual variations in muscle recruitment strategies and neuromuscular control were not modeled, which may influence load distribution in real-world scenarios.

Despite these limitations, our boundary conditions were derived from musculoskeletal parameters averaged across 40 participants rather than from a single individual. This approach helps to reduce the impact of random errors, such as marker artifacts, by treating them as noise that is averaged out in the larger sample, thereby improving the robustness and generalizability of the model inputs. Of course, the lack of formal sensitivity analyses limits our ability to quantify how anatomical or mechanical variation affects outcomes. Future studies should incorporate sensitivity analyses to enhance model robustness. Moreover, reflective markers combined with motion capture provide a cost-effective, reusable, and noninvasive tool. In addition, the study provides a novel, patient-specific approach to investigating biomechanical alterations in TLK, addressing a gap in the existing literature and laying the groundwork for future model refinement and clinical translation.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that patients with TLK exhibit elevated and uneven von Mises stress distributions in peri-spinal tissues during forward flexion. This altered mechanical loading may increase the risk of accelerated degeneration, tissue injury, and the development of chronic low back pain. These biomechanical insights can inform early clinical screening, personalized rehabilitation strategies, and surgical planning to better manage and mitigate risks associated with thoracolumbar kyphosis.

Data availability

The datasets associated with the study are not publicly available due patient data protection policy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zhu, W. et al. Curve patterns deserve attention when determining the optimal distal fusion level in correction surgery for Scheuermann kyphosis. Spine J. 19 (9), 1529–1539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2019.04.007 (2019).

Lorente, A., Barrios, C., Lorente, R., Tamariz, R. & Burgos, J. Severe hyperkyphosis reduces the aerobic capacity and maximal exercise tolerance in patients with Scheuermann disease. Spine J.19(2), 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2018.07.002 (2019).

Ristolainen, L. et al. Untreated Scheuermann’s disease: A 37-year follow-up study. Eur. Spine J.21(5), 819–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-011-2075-0 (2012).

Bezalel, T., Carmeli, E., Been, E. & Kalichman, L. Scheuermann’s disease: Current diagnosis and treatment approach. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil.27(4), 383–390. https://doi.org/10.3233/BMR-140483 (2014).

Diaremes, P., Braun, S. & Meurer, A. Morbus Scheuermann [Scheuermann’s disease]. Orthopade 51 (4), 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-1771334 (2022).

Lonner, B. et al. Effect of spinal deformity on adolescent quality of life: Comparison of operative Scheuermann kyphosis, adolescent idiopathic scoliosis, and normal controls. Spine38(12), 1049–1055. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182893c01 (2013).

Schwab, F., Lafage, V., Patel, A. & Farcy, J. P. Sagittal plane considerations and the pelvis in the adultpatient. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976)34(17), 1828–1833. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181a13c08 (2009).

Lin, G. et al. The effect of pedicle subtraction osteotomy for the correction of severe Scheuermann thoracolumbar kyphosis on sagittal spinopelvic alignment. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord.22(1), 165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03942-7 (2021).

Hadagali, P., Fischer, S. L., Callaghan, J. P. & Cronin, D. S. Quantifying the importance of active muscle repositioning a finite element neck model in flexion using kinematic, kinetic, and Tissue-Level responses. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 52 (3), 510–525 (2024). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37923814/

Hadagali, P. Assessing the Tissue-Level Response and the Risk of Neck Pain in Rotary-Wing Aircrew using a Finite Element Model of the Neck. University of Waterloo. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada. (2024). https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/items/e561b47d-03a1-48e5-a369-bf9d513f711a

Liu, T., Khalaf, K., Adeeb, S. & El-Rich, M. Effects of lumbo-pelvic rhythm on trunk muscle forces and disc loads during forward flexion: A combined musculoskeletal and finite element simulation study. J. Biomech.82, 116–123 (2019).

Liu, T., Khalaf, K., Adeeb, S. & El-Rich, M. Numerical investigation of intra-abdominal pressure effects on spinal loads and load-sharing in forward flexion. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.17, 7428 (2019).

Samir, Z. et al. Biomechanical evaluation of two posterior lumbar intervertebral fusion surgical scenarios reinforced by a rigid posterior fixation system in the vertebral column analyzed by the finite element methods. Nano Biomed. 10 (3), 258–278 (2018).

Rajaee, M. A., Arjmand, N. & Shirazi-Adl, A. A novel coupled musculoskeletal finite element model of the spine - Critical evaluation of trunk models in some tasks. J. Biomech.119, 110331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2021.110331 (2021).

Couvertier, M. et al. Biomechanical analysis o the thoracolumbar spine under physiological loadings: Experimental motion data corridors for validation of finite element models. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H231(10), 975–981. https://doi.org/10.1177/0954411917719740 (2017).

Ke, S. et al. The Biomechanical influence of facet joint parameters on corresponding segment in the lumbar spine: a new visualization method. Spine J. 21 (12), 2112–2121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2021.05.024 (2021).

Coenen, P. et al. Cumulative low back load at work as a risk factor of low back pain: A prospective cohort study. J. Occup. Rehabil.23(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-012-9375-z (2013).

Dandumahanti, B. P. & Subramaniyam, M. Biomechanical analysis of cervical spine (C2-C7) at different flexed postures. Int. J. Artif. Organs. 47 (3), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/03913988241229625 (2024).

Decker, M. J., Torry, M. R., Wyland, D. J., Sterett, W. I. & Richard Steadman, J. Gender differences in lower extremity kinematics, kinetics and energy absorption during landing. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol). 18 (7), 662–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0268-0033(03)00090-1 (2003).

Sell, T. C. et al. Predictors of proximal tibia anterior shear force during a vertical stop-jump. J. Orthop. Res.25(12), 1589–1597. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.20459 (2007).

Raabe, M. E. & Chaudhari, A. M. W. An investigation of jogging biomechanics using the full-body lumbar spine model: Model development and validation. J. Biomech.49(7), 1238–1243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.02.046 (2016).

Senteler, M., Weisse, B., Rothenfluh, D. A. & Snedeker, J. G. Intervertebral reaction force prediction using an enhanced assembly of OpenSim models. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin.19(5), 538–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/10255842.2015.1043906 (2016).

Lee, Y. H. et al. Computational comparison of three posterior lumbar interbody fusion techniques by using porous titanium interbody cages with 50% porosity. Comput. Biol. Med.71, 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2016.01.024 (2016).

Yu, C. C. et al. A new cervical artificial disc prosthesis based on physiological curvature of end plate: a finite element analysis. Spine J. 16 (11), 1384–1391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2016.06.019 (2016).

Alizadeh, M. et al. The use of X-shaped cross-link in posterior spinal constructs improves stability in thoracolumbar burst fracture: A finite element analysis. J. Orthop. Res.31(9), 1447–1454. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.22376 (2013).

Abdelkader, M., Samir Z, Nourddine, Z. & Ahmed, B. Development and validation of a numerical model for the mechanical behavior of knee prosthesis analyzed by the finite elements method. J. Biomim. Biomater. Biomed. Eng. 37, 12–42 (2018).

Wang, D. H. et al. Biomechanical analysis of adjacent segments after correction surgery for adult idiopathic scoliosis: A finite element analysis. Sci. Rep.14(1), 13181. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-63113-9 (2024).

Lin, M. et al. Effect of graded posterior element and ligament removal on annulus stress and segmental stability in lumbar spine stenosis: A finite element analysis study. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.11, 1237702. https://doi.org/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1237702 (2023).

Dreischarf, M. et al. Comparison of eight published static finite element models of the intact lumbar spine: Predictive power of models improves when combined together. J. Biomech.47(8), 1757–1766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.04.002 (2014).

Takahashi, I., Kikuchi, K., Sato, S. & Sato, N. Mechanical load of the lumbar spine during forward bending motion of the trunk-a biomechanical study. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976)31(1), 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000192636.69129.fb (2006).

Bridwell, K. H. et al. Complications and outcomes of pedicle subtraction osteotomies for fixed sagittal imbalance. Spine28(18), 2093–2101. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.BRS.0000090891.60232.70 (2003).

Liu, N., Chen, Z., Qi, Q. & Shi, Z. The relationship of symptomatic thoracolumbar disc herniation and Scheuermann’s disease. Eur. Spine J.23(5), 1059–1066. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-013-3108-7 (2014).

Funding

This project has received funding from the National Clinical Medical Research Centre Cultivation Program of Nanjing (No. 303103136AA22), Major sports research projects of Jiangsu Sports Bureau (No. ST242102), Jiangsu Province Hospital clinical diagnosis and treatment of technological innovation “Open bidding for selecting the best candidates” project (No. JBGS202414) and Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation Joint Fund Project (No. 2022-PJLH-5).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology and Conceptualization: CL.W, YT. Z and YQ.L. Biomechanical modeling: XX.W, J.S and RP.Z. Statistical analysis: C.Y, Y.S and XX.W. Investigation: C.Y and XW.S. Writing—original draft: CL.W and XX.W. Writing—review and editing: JA.L, YT. Z and YQ.L. CL.W, XW. S and XX.W contributed equally to this work. YQ. L and YT. Z are corresponding authors. All authors have reviewed the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wan, C., Shen, X., Wu, X. et al. Assessing the biomechanics of scheuermann’s kyphosis affected thoracolumbar spine in forward flexion at the tissue-level using a finite element model. Sci Rep 15, 27408 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12968-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-12968-7