Abstract

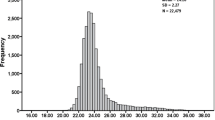

This study investigates the association between dietary lutein and zeaxanthin intake and the prevalence of myopia and astigmatism using data from the NHANES 2007–2008 survey. A total of 3,759 participants aged 12–59 years were analyzed. Myopia was classified into emmetropia, low myopia, and high myopia based on spherical equivalent refraction (SER), while astigmatism was categorized into high, low, and moderate based on right eye cylinder degree. Nutrient intake data, including lutein and zeaxanthin, were analyzed alongside sociodemographic and eye refractive data. Statistical comparisons between groups were conducted using t-tests and chi-square tests. Among participants, 58.7% were emmetropia group, 34.0% had low myopia, and 7.4% had high myopia. For astigmatism, 5.9% had high, 82.2% had low, and 12.9% had moderate levels. Significant differences were observed in sociodemographic factors, refractive measurements, and keratometry parameters across myopia and astigmatism groups (P < 0.05). However, dietary lutein and zeaxanthin intake showed no significant differences among these groups (P > 0.05). This cross-sectional study found no significant association between lutein and zeaxanthin intake and the prevalence of myopia or astigmatism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Myopia is a multifactorial condition influenced by genetic and environmental factors, typically manifesting in childhood or early adulthood, and high myopia is now one of the leading causes of visual impairment globally1,2. With projections indicating that 49.8% of the global population will be myopic by 2050, including 9.8% who may develop high myopia, myopia has become a significant public health concern3. Complications associated with myopia, such as cataracts, glaucoma, and retinal detachment, pose serious threats to ocular health in older adults and impose substantial socioeconomic costs4. Furthermore, myopia often coexists with astigmatism, another refractive error that can further impair visual function, particularly among children5.

Ocular astigmatism is a refractive condition which occurs because of unequal curvatures of the cornea and the crystalline lens, decentration or tilting of the lens, or unequal refractive indices across the crystalline lens, and in some cases, alterations of the geometry of the posterior pole6. Astigmatism is one of the most common refractive conditions in children and can impact both visual acuity and quality of life7,8,9.

Besides optical interventions, low concentration atropine, less screen time, less near work, red light therapy, and more outdoor time, dietary approaches have shown promise as safe, accessible options for myopia management10,11,12,13,14,15. Recent studies have suggested that antioxidants like lutein and zeaxanthin—carotenoids known for their protective roles in eye health—may influence the development of myopia16,17. Hypoxia-induced oxidative damage in myopic eyes can disrupt neuromodulatory pathways involving nitric oxide and dopamine, which are critical regulators of ocular growth, while excessive superoxide or peroxynitrite production may contribute to structural damage in retinal and vitreous tissues16. Lutein, a carotenoid with potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, may have protective effects against oxidative stress in ocular tissues. Its role in age-related macular degeneration is well-established, and preclinical studies suggest that lutein’s ability to neutralize free radicals and modulate inflammatory responses could theoretically mitigate oxidative damage implicated in myopia development17. However, the specific mechanisms linking dietary antioxidants to refractive error regulation remain to be fully elucidated. These nutrients possess anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties that could counteract processes contributing to refractive errors, such as oxidative stress and choroidal blood flow reduction18,19. Evidence has shown that the choroid, responsible for ocular blood supply, thins and experiences reduced perfusion as myopia progresses, which can exacerbate axial elongation and contribute to other refractive changes20,21.

Although several epidemiological studies have suggested potential links between higher lutein and zeaxanthin intake and lower risks of various ocular diseases, their relationship with both myopia and astigmatism remains underexplored. Given these findings, this study aims to examine the association between dietary lutein and zeaxanthin intake and the risk of myopia and astigmatism among adolescents and adults aged 12 to 59 years. Insights from this research may provide valuable dietary recommendations to support clinical strategies for the prevention and management of these prevalent refractive conditions.

Methods

Study design and population

Data for this cross-sectional study were extracted from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database, a representative program assessing the health and nutritional status of the U.S. population. NHANES collects data through a multistage, stratified sampling design, with approximately 5,000 participants surveyed every two years. For this study, we utilized data from the 2007–2008 NHANES cycle, accessible via the public database (https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/). The study was approved by the Ethics Review Board (ERB) of the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), and informed consent was obtained from all participants. As the data were de-identified, approval from our Institutional Review Board was not required.

A total of 3,759 participants aged 12–59 years who had undergone refraction measurements were included in the analysis. Participants were excluded if they had missing refraction data, incomplete demographic information, or a history of eye surgery or hyperopia.

Interocular agreement analysis demonstrated excellent reliability for spherical power (ICC = 0.920) and moderate reliability for cylindrical power (ICC = 0.701) based on Koo-Li criteria22. The 31% higher agreement for sphere versus cylinder reflects the greater biological stability of axial refractive error compared to corneal toricity. Given the primary focus on myopia (determined by spherical equivalent), the excellent agreement for spherical measurements fully justifies using right-eye data.

Lutein and zeaxanthin intake measurement

Lutein and zeaxanthin intake was assessed using a 24-hour dietary recall method, which records the types and amounts of food consumed. This approach provides reliable estimates of dietary intake and allows for quantification of lutein and zeaxanthin levels from various food sources. Specifically, we used the NHANES 2007–2008 datasets: DR1TOT_E (Day 1 dietary intake), DR2TOT_E (Day 2 dietary intake), DS1TOT_E (Day 1 supplement intake), and DS2TOT_E (Day 2 supplement intake). All data used were publicly available and fully de-identified.

Refractive error measurement and classification of myopia and astigmatism.

Refractive errors were assessed using a non-cycloplegic objective auto-refractor (Nidek ARK-760), with three repeated measurements for each eye. The median of these measurements was used for analysis, provided the confidence level was ≥ 5 (on a scale from 1 to 9). The spherical equivalent refraction (SER) was calculated for the right eye by averaging the refractions along the two principal meridians.

Myopia was defined as an SER value of ≤ − 1.0 diopter (D), with high myopia further defined as an SER of ≤ − 5.0 D. Participants were categorized into three groups based on their SER values: emmetropia group (− 1.0 D < SER ≤ + 0.5 D), low myopia (SER ≤ − 1.0 D), and high myopia (SER ≤ − 5.0 D).

Astigmatism was classified based on the refractive cylinder measurement of the right eye. Participants were categorized as follows: low astigmatism (OR right cylinder ≤ 1.0 D), moderate astigmatism (1.0 < OR right cylinder ≤ 2.0 D), and high astigmatism (OR right cylinder > 2.0 D). These classifications allowed for the examination of the relationship between dietary intake of lutein and zeaxanthin and different levels of refractive errors, including both myopia and astigmatism.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics and the intake of lutein and zeaxanthin across different refractive error categories. Comparisons between groups (emmetropia group, low myopia, high myopia, and different levels of astigmatism) were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Astigmatism was decomposed into vector components using Fourier harmonic analysis as described by Thibos et al.23. The cylindrical power (C) and axis (α) were transformed into orthogonal components: J0 = -(C/2) × cos(2α), representing with-the-rule (0°) or against-the-rule (180°) astigmatism. J45 = -(C/2) × sin(2α), representing oblique astigmatism (45° and 135° meridians). Linear regression models assessed associations between lutein/zeaxanthin intake (per 1000 mcg increase) and vector components, with β coefficients representing diopter change per 1000 mcg intake. All analyses were conducted using the survey analysis module of the R software, accounting for the complex sampling design of the NHANES data.

Results

Characteristics of participants

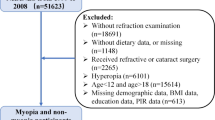

Figure 1 shows the flow chart of data screening. A total of 5,019 participants aged 12–59 years with information on lutein and zeaxanthin intakes from the NHANES database between 2007 and 2008 were initially included. After excluding participants with missing refraction measurements (n = 443) and those with hyperopia(SER > + 0.5 D) or ocular comorbidities (n = 817), 3,759 participants were included in the final analysis.

Table 2 presents the characteristics of participants with emmetropia, low myopia, and high myopia. Among the 3,759 participants, 2,206 (58.7%) were emmetropia group, 1,276 (34.0%) had low myopia, and 277 (7.4%) had high myopia. The mean age of the participants was similar across groups, with no significant age differences between the emmetropia, low myopia, and high myopia groups (F = 2.423, P = 0.0888). The gender distribution differed significantly between groups, with the emmetropia group having a higher proportion of males (52.4%) compared to the high myopia group (40.8%) and low myopia group (48.9%) (χ² = 15.069, P = 0.00053). Ethnic composition also varied significantly across groups (χ² = 26.833, P = 0.00076), with a higher percentage of Non-Hispanic Whites in the high myopia group. The poverty income ratio (PIR) was significantly higher in the high myopia group (PIR = 2.91) compared to the low myopia and emmetropia groups (F = 15.048, P = 0).

In terms of refractive characteristics, significant differences were observed across groups for the spherical equivalent refraction (SER), cylinder, and axis of refraction in both eyes (all P < 0.05). The high myopia group had the most negative SER values for both right (− 7.03 D) and left (− 4.74 D) spheres, as well as the highest cylinder values (right eye 1.48 D, left eye 3.31 D). Keratometric measurements also showed significant differences, with the high myopia group having the steepest corneal curvatures in both the flat and steep curves for the right and left eyes (all P < 0.05).

Regarding nutritional intake, there were no significant differences in energy, protein, carbohydrate, fat, or several micronutrients across groups. However, vitamin E intake was significantly higher in the high myopia group (14.27 mg) compared to the low myopia (13.55 mg) and emmetropia groups (12.48 mg) (F = 8.652, P = 0.00018), suggesting a potential association between vitamin E intake and myopia. Lutein and zeaxanthin intake did not differ significantly between the refractive error groups (F = 1.384, P = 0.25061).

Table 3 presents the comparisons of lutein and zeaxanthin intake across different refractive error groups, including high myopia, low myopia, and emmetropia. The mean intake of lutein and zeaxanthin in the high myopia group was 2504.45 ± 257.53 mcg, while the low myopia group had a mean intake of 2239.88 ± 99.01 mcg, and the emmetropia group had a mean intake of 2133.51 ± 78.2 mcg. There were no significant differences in lutein and zeaxanthin intake between any of the groups (P > 0.05), indicating that dietary intake of these carotenoids did not vary substantially with the degree of myopia in this cohort. These findings suggest that lutein and zeaxanthin intake may not be strongly associated with myopia severity based on this cross-sectional analysis.

Table 4 presents the stratified associations between myopia severity (low and high myopia) and lutein/zeaxanthin intake across age and racial/ethnic subgroups. No statistically significant associations were observed between myopia status (low or high) and lutein/zeaxanthin intake in any subgroup. Specifically, across age strata (12–17, 18–39, and 40–59 years), the estimated regression coefficients for low and high myopia remained non-significant (P > 0.05), with 95% confidence intervals overlapping zero. Similarly, within racial/ethnic subgroups (e.g., Mexican American, Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic White), no meaningful differences in lutein/zeaxanthin intake were detected between myopia categories. These findings suggest that demographic factors, such as age or ethnicity, do not modify the relationship between myopia severity and dietary lutein/zeaxanthin intake.

Table 5 presents the characteristics of participants with high astigmatism, low astigmatism, and moderate astigmatism. Among the 3,759 participants, 185 (5.9%) had high astigmatism, 3091 (82.2%) had low astigmatism, and 483 (12.9%) had moderate astigmatism. The average age of the participants varied significantly across the groups, with the high astigmatism group being older (35.51 ± 1.01 years) compared to the low astigmatism group (32.4 ± 0.25 years) and the moderate astigmatism group (34.86 ± 0.65 years) (P < 0.001).

The gender distribution was similar across the three groups, with a roughly equal proportion of males and females in each category (all P = 0.558). Ethnic composition also showed some differences, but these were not statistically significant (P = 0.090).

Significant differences were observed in several refractive parameters, including the right eye sphere, cylinder, and axis values. The high astigmatism group had the highest right eye cylinder value (3.27 ± 0.09 D), followed by the moderate astigmatism group (1.5 ± 0.01 D), with the low astigmatism group having the lowest value (0.48 ± 0.00 D), reflecting the severity of astigmatism across groups (P < 0.001). Similarly, the axis of astigmatism in the right eye differed significantly between groups (P = 0.002), with the high astigmatism group showing the largest mean axis value (95.04 ± 3.19°).

Keratometry measurements also varied significantly, with the high astigmatism group having the steepest curvature in both the right (46.06 ± 0.28 D) and left (46.52 ± 0.46 D) corneas (P < 0.001). These results are consistent with the higher severity of astigmatism in this group.

However, there were no significant differences in the intake of lutein and zeaxanthin, vitamin A, vitamin C, or vitamin E among the three astigmatism groups (all P > 0.05). Similarly, nutrient intake for energy, protein, carbohydrates, total fat, zinc, magnesium, selenium, and copper showed no significant variations across the groups, suggesting that dietary factors may not be closely linked to astigmatism severity in this population.

In summary, this analysis highlights significant differences in age and refractive parameters across the astigmatism severity groups, while showing no significant association between dietary intake and astigmatism severity.

Table 6 presents the comparison of lutein and zeaxanthin intake among participants with different levels of astigmatism: high astigmatism, low astigmatism, and moderate astigmatism. The table shows that there are no significant differences in lutein and zeaxanthin intake between any of the astigmatism severity groups. Specifically, the average intake of lutein and zeaxanthin was 2477.43 ± 306.63 mcg for the high astigmatism group, 2178.89 ± 64.99 mcg for the low astigmatism group, and 2205.13 ± 176.4 mcg for the moderate astigmatism group. The statistical comparisons across all groups showed P-values of 0.342, 0.889, and 0.442, respectively, indicating no significant association between lutein and zeaxanthin intake and the severity of astigmatism. These findings suggest that lutein and zeaxanthin intake does not vary meaningfully across different levels of astigmatism severity in this population.

Table 7 details the clinical interpretation of astigmatism vector parameters. The negative mean J0 component (−0.028 D) indicates predominant against-the-rule astigmatism, where the steepest corneal meridian is near horizontal (180°). This pattern aligns with the mean axis of 87.6°, approaching vertical orientation (90°). The near-zero J45 value (−0.009 D) confirms minimal oblique astigmatism in this cohort. Substantial standard deviations (J0 SD = 0.477 D; J45 SD = 0.263 D) reflect clinically important heterogeneity in astigmatism magnitude and orientation across participants. The mean cylindrical power of −0.781 D confirms moderate myopic astigmatism, consistent with our inclusion criteria.

Table 8 presents the descriptive statistics and association analysis of astigmatism vector components. Fourier decomposition revealed a predominance of against-the-rule astigmatism, evidenced by negative mean J0 values (−0.028 ± 0.477 D). The near-zero J45 component (−0.009 ± 0.263 D) indicated minimal oblique astigmatism. The axis distribution (mean 87.6°) further confirmed vertical steepening patterns consistent with ATR astigmatism. No significant associations emerged between lutein/zeaxanthin intake and astigmatism vector components. For orthogonal astigmatism (J0), each 1000 mcg intake increase corresponded to a 0.00128 D change (95% CI: −0.0029 to 0.0055; p = 0.546). For oblique astigmatism (J45), the effect size was 0.00103 D (95% CI: −0.0013 to 0.0034; p = 0.378) per 1000 mcg intake. These effect magnitudes are clinically insignificant, being < 0.5% of the 0.25 D threshold for clinically detectable refraction changes.

Table 9 presents the association between dietary lutein and zeaxanthin intake (stratified by median levels) and the risk of low and high myopia compared to emmetropia. After adjustment for covariates including age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, and nutritional factors (vitamin A/C/E, energy, and fat intake), higher lutein and zeaxanthin intake (≥ median) was associated with an increased risk of low myopia (OR = 1.19, 95% CI: 1.02–1.39, P = 0.027). In contrast, no significant association was observed between lutein and zeaxanthin intake and the risk of high myopia (OR = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.76–1.35, P = 0.913). While lutein and zeaxanthin are hypothesized to protect against oxidative stress in ocular tissues, their role in myopia progression remains inconclusive.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study, we explored the association between lutein and zeaxanthin intake and the occurrence of myopia and astigmatism. Our findings indicate that there were no statistically significant differences in the prevalence or severity of myopia between the groups with varying levels of lutein and zeaxanthin intake. This outcome suggests that, at least within the scope of this study, these carotenoids may not have a direct effect on the risk of developing myopia.

The vector analysis provides nuanced insights beyond conventional cylinder metrics24. The predominance of against-the-rule astigmatism (J0 = −0.028 D) aligns with age-related corneal changes in our adult-predominant cohort (mean age 32.5 years), consistent with the ATR shift25,26. The null associations for both J0 and J45 components (β ≈ 0.001 D/1000 mcg) reinforce our primary conclusion: lutein intake does not meaningfully influence astigmatism magnitude or orientation. The effect sizes are orders of magnitude below the 0.25 D clinical relevance threshold, suggesting that even unrealistically high intake increments (> 10,000 mcg/day) would produce < 0.01 D changes—undetectable in clinical practice.

Previous studies have highlighted the potential benefits of lutein and zeaxanthin in eye health, particularly their roles in protecting the retina through mechanisms such as the enhancement of macular pigment optical density (MPOD) and their antioxidant properties27,28. For instance, a systematic review indicated that higher MPOD levels, which are influenced by lutein and zeaxanthin intake, were positively associated with cognitive function, suggesting that these carotenoids play a significant role in retinal and brain health27. However, our study did not find evidence that increased lutein and zeaxanthin intake is associated with a reduction in myopia or astigmatism in the population we studied, which aligns with the conclusions of several studies showing mixed or null effects on refractive error outcomes29,30,31,32.

Additionally, our findings are consistent with studies on macular pigment density (MPOD) responses to supplementation, where significant increases in MPOD were often observed in patients with retinal diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD), rather than in those with refractive errors like myopia31,32. Furthermore, research examining lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation in healthy subjects has shown varying responses, with some individuals demonstrating increased MPOD levels while others showed little to no change, suggesting individual variability in carotenoid absorption and efficacy30,33.

In Table 6, the observed positive association between higher lutein and zeaxanthin intake (≥ median) and low myopia risk (OR = 1.19, P = 0.027) in adjusted models warrants further consideration. One plausible explanation is reverse causality: individuals with early-stage refractive errors, such as low myopia, might proactively adopt dietary modifications, including increased intake of lutein-rich foods or supplements, due to perceived benefits for eye health. However, if lutein and zeaxanthin lack substantial efficacy in mitigating myopia progression, this behavioral response could artifactually inflate the OR above 1. Additionally, residual confounding by unmeasured lifestyle factors, such as reduced outdoor time or prolonged near work—both established risk factors for myopia—might partially explain this association. For instance, individuals with higher socioeconomic status (correlated with healthier diets) may also engage in more near-work activities (e.g., reading or screen use), inadvertently elevating myopia risk despite increased lutein intake. The attenuation of the OR and the rising P-values across sequential adjustments (from Model 1 to Model 3) further suggest that demographic and nutritional confounders (e.g., age, race, and vitamin intake) contribute to the initial association, diluting its statistical significance as these variables are accounted for. This pattern underscores the likelihood of unmeasured confounders influencing the results.

While our study did not detect a significant effect of lutein and zeaxanthin intake on myopia risk, it is important to consider several potential explanations. One possible explanation is that genetic factors might play a more significant role in the early development of refractive errors, potentially limiting the impact of diet and other environmental influences34,35,36,37. Then, the lack of significant findings could be due to the cross-sectional nature of the study, where causality cannot be established. Furthermore, the measures of lutein and zeaxanthin intake and refractive error may not fully capture the complexity of the relationship between these carotenoids and myopia. Studies with larger sample sizes, longer follow-up periods, and more precise measurements of both carotenoid intake and refractive changes are needed to more accurately assess any potential protective effect of lutein and zeaxanthin against myopia progression.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study found no significant association between lutein and zeaxanthin intake and the prevalence or severity of myopia or astigmatism in participants. Despite previous suggestions that these carotenoids may play a protective role in ocular health, our findings indicate that their intake does not appear to significantly influence refractive error outcomes in this population. Further longitudinal studies are needed to explore whether long-term dietary intake of lutein and zeaxanthin could have a meaningful impact on the development or progression of myopia and astigmatism. Additionally, future research should consider other dietary factors, genetic influences, and environmental exposures that may contribute to refractive error outcomes. Understanding the complex interplay between diet, genetics, and environmental factors is crucial for developing effective strategies for myopia and astigmatism prevention and management.

Data availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. These data can be found here: NHANES database, https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/.

References

Morgan, I. G. et al. IMI risk factors for myopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62 (5), 3 (2021).

Du, Y. et al. Complications of high myopia: an update from clinical manifestations to underlying mechanisms. Adv. Ophthalmol. Pract. Res. 4 (3), 156–163 (2024).

Holden, B. A. et al. Global prevalence of myopia and high myopia and Temporal trends from 2000 through 2050. Ophthalmology 123 (5), 1036–1042 (2016).

Sankaridurg, P. et al. IMI impact of myopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 62 (5), 2 (2021).

Tang, Y. et al. Prevalence and time trends of refractive error in Chinese children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Glob Health. 11, 11 (2021).

Nunez, M. X. et al. Consensus on the management of astigmatism in cataract surgery. Clin. Ophthalmol. 13, 311–324 (2019).

Tajbakhsh, Z. et al. The prevalence of refractive error in schoolchildren. Clin. Exp. Optom. 105 (8), 860–864 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for astigmatism in 7 to 19-year-old students in xinjiang, china: a cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 24 (1), 13 (2024).

Bastias, G., Villena, M., Dunstan, M. R. & Zanolli, E. J. Myopia and myopic astigmatism in school-children. Andes Pediatrica: Revista Chil. De Pediatria. 92 (6), 896–903 (2021).

Chia, A., Lu, Q. S. & Tan, D. Five-Year clinical trial on Atropine for the treatment of myopia 2: myopia control with Atropine 0.01% Eyedrops. Ophthalmology 123 (2), 391–399 (2016).

Huang, H. M., Chang, D. S. & Wu, P. C. The association between near work activities and myopia in Children-A systematic review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 10(10), e0140419.1-15 (2015).

Xu, Y. et al. Repeated Low-Level red light therapy for myopia control in high myopia children and adolescents: A randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology 131 (11), 1314–1323 (2024).

He, M. et al. Effect of time spent outdoors at school on the development of myopia among children in china: A randomized clinical trial. Jama 314 (11), 1142–1148 (2015).

Zhou, Z. et al. Association of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intakes with juvenile myopia: A cross-sectional study based on the NHANES database. Front. Pediatr. 11, 1122773 (2023).

Pan, M. et al. Dietary ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids are protective for myopia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 118, 43 (2021).

Francisco, B. M., Salvador, M. & Amparo, N. Oxidative Stress in Myopia. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2015. (2015).

Buscemi, S. et al. The effect of lutein on eye and Extra-Eye health. Nutrients 10, 9 (2018).

Nagai, N. et al. Correlation between macular pigment optical density and neural thickness and volume of the retina. Nutrients 12 (4), 10 (2020).

Xiao, K. H. et al. Association between micronutrients and myopia in American adolescents: evidence from the 2003–2006 National health and nutrition examination survey. Front. Nutr. 11, 8 (2024).

Ostrin, L. A. et al. IMI-The dynamic choroid: new insights, challenges, and potential significance for human myopia. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 64 (6), 4 (2023).

Liu, Y., Wang, L., Xu, Y., Pang, Z. & Mu, G. The influence of the choroid on the onset and development of myopia: from perspectives of choroidal thickness and blood flow. Acta Ophthalmol. 99 (7), 730–738 (2021).

Koo, T. K. & Li, M. Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 15 (2), 155–163 (2016).

Thibos, L. N., Applegate, R. A., Schwiegerling, J. T. & Webb, R. Standards for reporting the optical aberrations of eyes. J. Refractive Surg. (Thorofare N J. : 1995). 18 (5), S652–S660 (2002).

Thibos, L. N., Wheeler, W. & Horner, D. Power vectors: an application of fourier analysis to the description and statistical analysis of refractive error. Optometry Vis. Science: Official Publication Am. Acad. Optometry. 74 (6), 367–375 (1997).

Elliott, D. B., Yang, K. C. & Whitaker, D. Visual acuity changes throughout adulthood in normal, healthy eyes: seeing beyond 6/6. Optometry Vis. Science: Official Publication Am. Acad. Optometry. 72 (3), 186–191 (1995).

Ueno, Y. et al. Age-related changes in anterior, posterior, and total corneal astigmatism. J. Refractive Surg. (Thorofare N J. : 1995). 30 (3), 192–197 (2014).

García-Romera, M. C. et al. Effect of macular pigment carotenoids on cognitive functions: A systematic review. Physiol. Behav. 254, 14 (2022).

Ma, L. et al. Lutein, Zeaxanthin and Meso-zeaxanthin supplementation associated with macular pigment optical density. Nutrients 8 (7), 14 (2016).

Zhang, Y. et al. Macular pigment optical density responses to different levels of Zeaxanthin in patients with high myopia (Jan, 10.1007/s00417-021-05532-2, 2022). Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 260 (7), 2387–2387 (2022).

Tanito, M. et al. Macular pigment density changes in Japanese individuals supplemented with lutein or zeaxanthin: quantification via resonance Raman spectrophotometry and autofluorescence imaging. Jpn J. Ophthalmol. 56 (5), 488–496 (2012).

Korobelnik, J. F. et al. Effect of dietary supplementation with lutein, zeaxanthin, and ω-3 on macular pigment A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol. 135 (11), 1259–1266 (2017).

Obana, A. et al. Changes in macular pigment optical density and serum lutein concentration in Japanese subjects taking two different lutein supplements. PLoS One. 10 (10), 16 (2015).

Azar, G., Maftouhi, M. Q. E., Masella, J. J. & Mauget-Faÿsse, M. Macular pigment density variation after supplementation of lutein and Zeaxanthin using the Visucam < SUP>(R) 200 pigment module: impact of age-related macular degeneration and lens status. J. Fr. Ophthamol. 40 (4), 303–313 (2017).

Chua, S. Y. L. et al. Growing Up Singapore Towards, H., Relative Contribution of Risk Factors for Early-Onset Myopia in Young Asian Children. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56 (13), 8101–8107. (2015).

Chua, S. Y. L. et al. Diet and risk of myopia in three-year-old Singapore children: the GUSTO cohort. Clin. Exp. Optom. 101 (5), 692–699 (2018).

Li, M. J. et al. Dietary intake and associations with myopia in Singapore children. Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt. 42 (2), 319–326 (2022).

Vongphanit, J., Mitchell, P. & Wang, J. J. Prevalence and progression of myopic retinopathy in an older population. Ophthalmology 109 (4), 704–711 (2002).

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Keyu Chen wrote the main manuscript text and prepared Tables 2, 3 and 4. Lianhong Pi and Haibo xiong prepared figures 1; Table 1. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, K., Pi, L. & Xiong, H. Association of nutritional intake with myopia and astigmatism. Sci Rep 15, 27151 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13203-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13203-z