Abstract

Data on vector-borne pathogens infecting dogs from sub-Saharan Africa is limited. In this study, we assessed the prevalence of VBPs, their associated risk factors, and pathogen interactions in domestic dogs. Whole blood samples were obtained for 1202 apparently healthy dogs in Chad from September to October 2021, and nucleic acids were extracted and then subjected to a targeted next-generation sequencing (tNGS) assay for detection of 15 VBPs. Overall, 88.7% of the dogs were positive for at least one pathogen, and 62.9% were coinfected with two or more VBPs. The most frequent pathogen detected was Hepatozoon canis in 62.4% of the dogs, Mycoplasma haemocanis in 59.2%, Anaplasma platys in 29.2%, Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum in 21.2%, Ehrlichia canis in 20.3%, Babesia vogeli in 2.0% and Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis in 1.5%. While most of the dogs (62.9%) were co-infected with two or more VBPs, having an infection with three pathogens (30.8%) was more common. According to multivariable logistic regression analysis, being a senior dog and residing in Chari Baguirmi south were identified as potential risk factors for infection by most of the pathogens. Network analyses revealed complex interactions suggesting facilitative associations among VBPs. These results are useful in expanding the knowledge of VBPs in Africa and establishing a baseline for downstream studies into hemotropic mycoplasmas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris) are susceptible to infections with several vector-borne pathogens (VBPs) caused by protozoa, bacteria, viruses, and nematodes transmitted by ticks, fleas, mosquitoes, and biting flies, which can cause significant morbidity and mortality1. In sub-Saharan Africa, most of the domestic dogs, particularly in rural settings, have a relatively unrestricted movement, allowing them access to wilderness environments and close association with humans2. This situation promotes the transmission and dissemination of vector-borne zoonoses3,4. Importantly, even subclinically infected dogs can serve as sentinels for human vector-associated pathogens, indicating geographical areas with increased zoonotic risk3.

Ticks and fleas are the most common ectoparasites of dogs, and both vector a wide array of VBPs such as protozoa and bacteria belonging to the genera Hepatozoon, Rickettsia, Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, Babesia, Borrelia, Bartonella, Yersinia and Mycoplasma (supplementary Table 1). Some ticks are highly adapted to feed and transmit pathogens primarily to domestic dogs, including those belonging to the Rhipicephalus sanguineus complex and Haemaphysalis leachi group5. In fact, most pathogens transmitted to dogs by vectors are linked to infestations by species within the R. sanguineus complex due to its widespread range and specialized feeding on domestic dogs5,6,7. The R. sanguineus complex encompasses at least 16 morphologically and phylogenetically related species8including R. sanguineus tropical lineage recently renamed as R. linnaei9 primarily distributed in the Afrotropics10. Ticks within the R. sanguineus complex are known to transmit B. vogeli11 and Hepatozoon canis12 and rickettsial agents of the genera Anaplasma, Ehrlichia, and Rickettsia, which have been genetically detected in Chad13,14,15. Furthermore, R. sanguineus s.l. is implicated in transmitting hemotropic mycoplasmas, which cause severe hemolytic anaemia16. However, strong evidence suggests that aggressive interactions such as fighting among dogs and vertical passage contribute to additional transmission pathways for hemotropic mycoplasmas in the absence of arthropod vectors17,18. The cat flea, Ctenocephalides felis felis, is regarded as the most dominant flea species associated with dogs and cats worldwide. The cat flea is a vector of numerous emerging zoonotic agents such as Rickettsia felis and Bartonella henselae known to cause febrile illness in sub-Saharan, Africa19,20. In addition, fleas are implicated in hemotropic mycoplasma transmission, including the potentially zoonotic Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum to dogs and cats. However, transmission of canine hemotropic mycoplasmas is not well established21,22. Co-infections with two or more VBPs may complicate disease and clinical presentations especially in tropical and sub-tropical areas where vectors are abundant.

While VBP surveys have been conducted in some regions of sub-Saharan Africa, comprehensive epidemiological studies are lacking in Chad. Previous research has relied on routine diagnostic methods, such as PCR13,14,15,23which were limited to a small number of canine pathogens per test, requiring many individual tests to obtain a comprehensive diagnosis. The latest advancement in diagnostic laboratories is a targeted next-generation-sequencing (tNGS) approach that was explicitly developed for the detection of canine pathogens24,25. This tNGS method is highly sensitive and specific, enabling the detection of multiple canine VBPs in a single test and further identifying species within the same genus24. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) assays have demonstrated the capability to identify a diverse array of pathogens through the utilization of conserved primers, such as those targeting hyper-variable regions of the 16 S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene in bacterial pathogens. These assays are also capable of detecting rare and novel pathogens by sequencing specific regions of interest within the genome. The aim of this study was to (1) integrate targeted NGS and multivariable logistic regression methods to determine the prevalence of VBPs among dogs in Chad and the associated risk factors and (2) apply Yule’s Q statistic, and social network analysis to determine interactions between VBPs in these dogs.

Methods

Ethical statement

All procedures involving the handling of dogs and collection of blood samples were approved by the National Bioethics Committee of Chad (Protocol #005/PR/MESRI/SE/DGM/CNBT/SG/2022) and the University of Georgia’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (A2019 04-005-Y4 A2). Informed consent and permission were granted by the owners of the dogs to obtain blood samples. All experiments and protocols were performed in compliance with relevant guidelines and regulations and are reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Study site and sample collection

From September to October 2021 (corresponding to the end of the rainy season), whole blood samples were collected as part of a larger study assessing the effectiveness of flubendazole for the treatment of Guinea worm in 56 villages across three regions along the Chari River in Chad (Fig. 1.). The dogs were restrained, and blood was drawn via cephalic or sometimes saphenous venipuncture. The blood was placed in 3 mL EDTA vacutainer tubes (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) and stored in a field cooler and kept refrigerated from the field to one of the Carter Center’s field locations. Blood was transferred to labeled tubes and kept refrigerated during transport to N’Djamena and later exportation to the United States (USA). Data on sex, age, and associated village were obtained by field teams by direct observation for village and asking the owner to report the age and sex.

Molecular analysis

The samples were kept frozen, at -80° C, and thawed before processing. After thawing, 50–500 µl of individual whole blood samples were treated in a solution of lysis buffer and proteinase K for at least 5 min, followed by incubation at 56 °C for 30 min. The lysate was used for nucleic acid extraction using a Maxwell® RSC Tissue DNA Kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) in a robot Maxwell® RSC 48 device (Promega) following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Next-generation sequencing

We utilized the targeted next-generation sequencing assay described by Kattoor et al.24. By utilizing primer pools targeting multiple genes for each pathogen, the panel allowed for the simultaneous detection of 15 commonly diagnosed canine VBPs in a single reaction. Automated libraries were prepared with the Ion AmpliSeq™ Kit for Chef DL8 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries were loaded onto Ion 530™ chips using the Ion 510™ & Ion 520 TM & Ion 530 TM Kit – Chef (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and Ion 530 TM chips were sequenced using the Ion GeneStudio™ S5 sequencing system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the recommended protocol. The VBPs targeted by the tNGS include but are not limited to Babesia species, Bartonella species, Borrelia species, Cytauxzoon species, Hepatozoon species, Rickettsiales species, and hemotropic mycoplasmas.

Bioinformatics

Barcode and adapter trimmed raw data were assembled using SPAdes (v5.12.0.0 on the Torrent Suite Server (TSS)) followed by alignment to target sequence regions from reference genomes of the pathogens within the TSS. Geneious Prime v. 2021.1.1 https://www.geneious.com/prime/ was used to evaluate the aligned BAM files for each sample, and the BLAST analysis of potential pathogen reads https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi was performed to confirm the results.

Statistical analysis

Data were managed in an Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using R version 4.4.1 (R: The R Project for Statistical Computing (r-project.org) and RStudio 2024.04.2 Build 764. Based on the tNGS outcomes, a binary variable presence or absence of VBPs was made. The distribution of variables was examined and presented in tables as frequencies and proportions. Defining an average lifespan for African dogs can be challenging, as this number varies from country to country based on various socioeconomic factors. Studies reveal mean life expectancies ranging from as low as 1.1 years in Zimbabwe26,27 to 12 years in Botswana28; thus, the continuous variable age was categorized into three groups: <2 yrs (juvenile), ≥ 2–5 yrs (adult), and ≥ 5 yrs (senior).

The oddsratio function (from the epitools package in R) was used to compute prevalence odd ratios (PORs) along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). The Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were performed to compare positivity to each pathogen. A Fisher’s exact test was used for values below five (age and sex) for B. vogeli and (age, geographic region, and sex) for C. M. turicensis, while all other P-values were calculated with the Chi-square test of independence. A P-value adjustment was performed by using the Bonferroni correction in R to correct for family-wise error rate. The adjusted P-values were then compared to the nominal significance level of 0.05. Logit models were used to quantify relationships between explanatory variables (age, geographic region, and sex) and the prevalence of each VBP. A multiple logistic regression was fitted for each pathogen outcome, and adjusted odds ratios (OR) with their corresponding confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. To correct for familywise error by conducting multiple comparisons, the p.adjust function in R was used to adjust the P-values by the Bonferroni correction method (Table 2).

Co-occurrence network analysis

Associations between pathogen pairs were determined using the igraph package in R based on Yule’s Q values29. The resulting values from the matrix derived by Yule’s Q statistic are presented in a correlogram (Fig. 2). The range of Yule’s Q values is from negative 1 to 1. Perfect positive association is denoted by + 1 and may suggest that the other is always present when one pathogen is present. A value of -1 indicates a perfect negative association, suggesting that the other is always absent when one pathogen is present. A value of 0 indicates no association. Permutation tests were performed to allow the derivation of P-values to elucidate how likely the associations happened by chance. A threshold was determined in the analysis wherein we identified pathogen pairs exhibiting absolute Yule’s Q values exceeding 0.3 in conjunction with P-values ≤ 0.05, thereby delineating significant interactions. The co-occurrence network was generated in R using the computed Yule’s Q and the graphml file loaded into Gephi 0.10.1 (Gephi.org) software30 for further exploration and generation of the final network (Fig. 3). The Force Atlas algorithm was used for node positions in Gephi.

Correlogram of Yule’s Q values showing associations among VBPs detected in dog blood. Each cell represents the Q value between two pathogens, with colors denoting the strength of the correlation: dark red signifies a strong positive correlation (Q values close to 1), light red indicates a moderate correlation, and grey color, weak negative associations and white indicates strong negative correlations.

Co-occurrence network for VBPs detected in the blood of dogs. Node position was determined using the Force Atlas algorithm in Gephi. The nodes represent pathogens and node size indicates the proportional contribution of each pathogen to the pair (the larger the node the stronger the interactions with other pathogens, suggesting more influence in the network. Red edges (connections) indicate negative associations while green edges signify positive associations. Edge thickness indicates the strength of the relationship based on Yule’s Q values. The prevalence % of each pathogen is shown in parentheses.

Results

Molecular findings

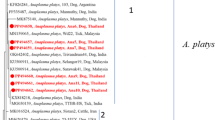

A total of 1202 blood samples were collected from domestic dogs in Mayo Kebbi Est (n = 485), Chari Baguirmi north (n = 356), and Chari Baguirmi south (n = 361) regions along the Chari River. Males represented 65.4% (n = 786) and females 34.6% (n = 416), with ages ranging from six months to 17 years old. The most prevalent protozoan was H. canis, which was detected in 62.4% (750/1202; 95% CI 59.6–65.1%) of the dogs, followed by B. vogeli in 2.0% (24/1202; 95% CI 1.4–3.0%). The most prevalent Rickettsiales species were A. platys 29.2% (351/1202; 95% CI 26.7–31.8%) and E. canis 20.3% (244/1202; 95% CI 18.1–22.7%). We detected a high prevalence of bacterial hemotropic mycoplasmas including M. haemocanis 59.2% (711/1202; 95% CI 56.4–61.9%), C. M. haematoparvum 21.2% (255/1202; 95% CI 19.0–23.6%), and C. M. turicensis 1.5% (18/1202; 95% CI 0.9–2.4%). Overall, 88.7% (1066/1202; 95% CI 86.8–90.4%) of dogs were positive for at least one VBP and 62.9% (756/1202; 95% CI 60.1–65.6%) were coinfected with 2 or more VBPs, with individual dogs being coinfected with up to six pathogens. Using a panel of 15 pathogens, we found seven pathogens, including co-infections, as described above. Other selected pathogens included in the panel were not detected (e.g., Bartonella spp., Leishmania infantum, Borrelia burgdorferi, Rickettsia rickettsii, and Cytauxzoon felis). The prevalence of infection based on age, geographic region, and sex is shown in Table 1.

Risk factor analysis

According to Chi-Square and Fisher’s exact tests, age was significantly associated with all the pathogens detected (P ≤ 0.048) except E. canis and B. vogeli. The variable geographic region showed a statistically significant association with all pathogens except M. haemocanis (χ2 = 0.118; P > 0.99) and C. M. turicensis (χ2 = 23.65; P > 0.99). Sex was only associated with M. haemocanis (χ2 = 14.21; P < 0.001) and C. M. haematoparvum (χ2 = 11.38; P = 0.002) (Table 1). Based on multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 2), being a senior (≥ 5 years) was a potential risk factor for H. canis (OR 1.3, 95% CI 0.9–1.9; P = 0.718). Likewise, these results indicate 3.6 times higher odds of infection with A. platys in seniors (OR 3.6, 95% CI 2.6–5.2; P = 0.025) and 1.6 times higher odds in dogs from Chari Baguirmi south (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2–2.2, P = 0.014). Additionally, the odds of E. canis infection increased with being a senior despite the non-significant P-value (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.4; P = 0.113) and residing in Chari Baguirmi south (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.5–3.0; P < 0.001).

These results show that juvenile dogs had 40% lower odds (OR 0.6, 95% CI, 0.4–0.8; P < 0.003) of having M. haemocanis. The odds of C. M. haematoparvum occurrence were 3.6 times higher for senior dogs (OR 3.6, 95% CI; 2.6–5.2; P < 0.001) as compared to adults. Geographically, dogs in Chari Baguirmi south showed 50% less likelihood of C. M. haematoparvum infection compared to Mayo Kebbi Est (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.7; P < 0.001). Female dogs exhibited 40% less odds of infection with M. haemocanis (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.5–0.8; P < 0.002) and C. M. haematoparvum (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4–0.9; P = 0.03) compared to males (Table 2).

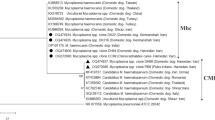

Network analyses and coinfections

Coinfections among VBPs were observed among all pathogen pairs, with the coinfection of H. canis and M. haemocanis as the most prevalent combination. Associations between pathogen pairs revealed both negative and positive associations among pathogens. Details of interactions based on Yule’s Q are shown in Fig. 2.0. A significant node in this analysis was identified as H. canis, which exhibited a statistically significant positive association (P-value ≤ 0.047) with three additional taxa (Table 3). In addition, according to the network, other species such as C. M. turicensis were central players within the social interaction network, exhibiting robust connections with multiple taxa (Fig. 3). Hemotropic mycoplasmas showed strong positive associations among each other based on Yule’s Q values, hinting at a potential facilitative role in the network. We observed that negative interactions did not attain statistical significance at the specified Yule’s Q threshold of 0.3 and a P-value (P ≤ 0.05). Specifically, B. vogeli showed a strong but non significant negative interaction with H. canis, M. haemocanis and A. platys.

Discussion

VBPs have increased worldwide in prevalence over the last decade21,31,32. When companion animals such as dogs are involved, VBPs are perceived as a significant threat to public health due to the shared proximity between domestic dogs and people. The few studies reporting VBP prevalence in Chad have used PCR techniques14,15,23. While this approach is relatively simple and inexpensive, it requires multiple tests to capture several pathogens at once. Serological studies have also been conducted23; however, one limitation of this approach is the inability to differentiate past and ongoing infections. We chose tNGS because of its ability to extensively amplify pathogen sequences of interest while simultaneously detecting up to 15 pathogens within a single reaction.

Chad is characterized by an arid Saharan desert in the north, sub-tropical and semi-arid Sahel region in central Chad and a tropical savannah in the south with warm and humid climate33, which makes it a suitable landmark for VBPs including some of zoonotic concerns. Domestic dogs in Chad are mostly free-roaming in both rural and urban settings2 and may have close interactions with other dogs and wildlife, so they may serve as sentinels for zoonotic VBPs. Of the 1202 dogs screened, 1066 (88.7%) were positive for at least one pathogen. This rate is consistent with the positive detection rate of 77% from a past study in Nigeria using PCR and sequencing34and a 70% infection rate in six sub-Saharan African countries (i.e., Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda and Namibia) performed using quantitative PCR35.

Hepatozoon canis was the most prevalent pathogen (62.9%). This finding is consistent with the high prevalences of H. canis previously found in Chad and several other African countries35,36,37. This high occurrence of H. canis may be attributed to the high prevalence of infestations by R. sanguineus s.l. ticks which are prevalent in the region6,38. Aside vectorial transmission, vertical H. canis transmission has been confirmed39. This protozoan infection has been reported in various tropical and subtropical areas on most continents; its distribution, which overlaps with that of R. sanguineus s.l., includes northern and southern Africa11,40Asia41Europe42and the Americas43. While the results of this study indicate a low prevalence of B. vogeli (2.0%), this was consistent with 5.1% prevalence reported from Egypt 11 and 6.6% reported from Tunisia44. In contrast, this number was lower than the high infection rate of 10.8% observed in Nigeria45. This difference may reflect various factors such as the experimental design, climatic conditions, season when sampling was performed, animal care and sanitary conditions, and diagnostic tests used11. Babesia rossi, recognized as the most virulent of the large Babesia species affecting dogs, has not been identified in this cohort, despite its known endemic presence across the African continent23,46. This absence could be attributed to the lack of H. elliptica, considered its main tick vector, or the low density of H. leachi previously found on dogs from Chad38,46.

Pathogens belonging to the family Anaplasmataceae, specifically A. platys and E. canis, significantly impact canine health in tropical and subtropical climates, causing canine infectious cyclic thrombocytopenia and canine monocytic ehrlichiosis, respectively. The two infections are considered acute, self-limiting, and sometimes fatal3,47. The frequencies of dogs positive for both pathogens manifest significant regional variability across different parts of the world. In the current study, 29.2% of dogs were found to be infected with A. platys; this rate is considerably higher than those reported in Nigeria (6.6%)34Angola (20.4%)48Malawi (2.4%)37Egypt (1.5%)49 and Ethiopia (2.2%)50. This difference is unexpected, as the brown dog tick is globally widespread, especially in the tropics and sub-tropics6. Similarly, we found a higher prevalence of E. canis (20.3%) than has been reported previously in South Africa (3%)51Nigeria (12.7%)34and Malawi (3.8%)37. These two Rickettsial species are often reported together, which can exacerbate disease in dogs. Notably, high levels of coinfections of A. platys, E. canis, and hemotropic mycoplasmas were observed, adding to the zoonotic risk.

Canine hemotropic mycoplasmas have not been previously reported in dogs from Chad. The current report provides fundamental data for several Mycoplasma species in this population: M. haemocanis was detected in 59.2%, C. M. haematoparvum in 21.2%, and C. M. turicensis in 1.5% of the dogs. The high prevalence suggests that apparently healthy dogs in Chad have been exposed to Mycoplasmas posing health risks and having potential zoonotic implications. Few studies from sub-Saharan African countries have reported a lower prevalence of dog-infecting hemotropic mycoplasmas including Angola52Nigeria53 Tanzania54 and Sudan55. Past studies have reported that the transmission pathways for hemotropic mycoplasmas in dogs largely involve non-vector routes such as vertical transmission and mechanisms such as blood ingestion and transdermal inoculation during aggressive interactions17. The free-roaming and free-foraging nature of rural Chadian dogs, which live outdoors, likely contributes significantly to aggression behavior such as fighting and biting and ultimately to the high prevalence of hemotropic mycoplasma infections in this study17. C. M. turicensis is recognized as the hemotropic mycoplasma species of felids56. Given the interactions between domestic dogs and cats, there is a plausible risk of spill-over, potentially facilitated by vectors such as ticks and fleas22. Notably, C. M. turicensis has been identified among dogs from Chile57. Furthermore, instances of C. Mycoplasma haemominutum, another feline hemotropic mycoplasma, have been documented in puppies, thereby strengthening the evidence for interspecies transmission of cat-infecting mycoplasmas to dogs58. Collectively, these findings warrant further exploration as they raise questions regarding the mechanisms of infection, including the potential for vertical Mycoplasma transmission.

The prevalence of A. platys and C. M. haematoparvum was significantly associated with increased odds in senior dogs (P < 0.05). Moreover, even though non-significant, the odds of infection with other pathogens, including H. canis and E. canis, were still higher in senior dogs. Aging might induce a weakened immune system that declines the ability to clear infections, increasing coinfection rates with other VBPs, and an increased risk of mortality in susceptible individuals59. Furthermore, inadequate veterinary care and lack of regular acaricidal treatment for dogs in this region may aggravate vector infestations. Heavy tick infestations might increase the risk of coinfections, especially if infections are not cleared by the immune system. Geographically, multivariable logistic regression indicated that the prevalence of A. platys, E. canis, and C. M. haematoparvum was associated with residence in Chari Baguirmi south. Studies have revealed that tropical climates are favorable environments for vector survival31. Ticks adapt better to cooler climates with higher precipitation, such as the subtropical steppe climate of Chari Baguirmi south, contrary to desert climates characterized by arid climate, extreme heat, and less humidity, such as Chari Baguirmi north60. Specifically, the heightened likelihood of these pathogens in dogs from the south could be due to conducive climatic conditions that facilitate sustained exposure of dogs to recurrent tick infestations. The life cycle and developmental stages of their tick vector R. sanguineus s.l. depends on specific temperature and humidity thresholds to thrive and maintain infections6. In this population, most of the hemotropic mycoplasmas were significantly associated with decreased odds in female dogs (P < 0.05) compared to male dogs. This finding is consistent with another study on canine VBPs61. The reason for this outcome could be behavioral and physiological. According to previous studies, male dogs are likely to roam more frequently and extensively, predisposing them to recurrent vector infestations, coinfestations and coinfections, including by vectors and VBPs commonly found in cattle and wildlife. Empirical observations and the scientific literature show that aggression in male dogs is remarkably higher than in their female counterparts. Specifically, there is a pronounced correlation between elevated levels of testosterone and aggressive behavior in male dogs, which may intensify the transmission of hemotropic mycoplasma species62,63.

A complex social interaction between VBPs was observed through the co-occurrence network analysis. The positive associations identified highlight the potential facilitative nature of coinfecting pathogens with each other within the vertebrate hosts and possibly within the vector microbiome64. These interactions ultimately shape transmission and virulence dynamics in VBP ecology. Notably, H. canis was found as a strongly interconnected node exhibiting strong statistically significant associations with several other pathogens (P ≤ 0.047) (Table 3). According to the network (Fig. 3), other species such as C. M. turicensis were central players within the social interaction network, exhibiting robust connections with multiple taxa (Fig. 3) and highlighting a potential synergistic relationship (Table 3). However, considering the small number of C. M. turicensis detections, these associations should be interpreted with caution. The strong positive associations between hemotropic mycoplasmas suggest a synergistic relationship facilitating their coexistence within canine hosts. Pathogens may directly facilitate others when their by-products are useful resources for another member, enhancing the fitness of co-occurring species in a shared niche65. In contrast, negative interactions were observed between B. vogeli and most pathogens, including H. canis, but these were non-significant and may not suggest actual competitive interactions. A possible explanation for this could be protective effects on the host against highly pathogenic organisms such as B. vogeli through colonization with less pathogenic species such as H. canis, particularly at high parasitemia levels66. Mechanisms of competition involve various processes, including resource competition and interference competition. Interference competition occurs indirectly via host-mediated immunity, where the host immune responses activated towards one pathogen may inadvertently promote susceptibility towards another, such as in the case of cross-immunity, where antibodies produced to harm one pathogen counteract another67. As such, these findings underscore the need for further exploration into inter-species coinfections and their role in virulence and disease progression68.

Taken together, these findings provide new data on prevalence patterns, associated risk factors, and interactions behind the epidemiologic risk of vector-borne protozoa and bacteria in this population. In Chad, the tropical climate and the large dog populations in rural areas promote the life cycle of R. sanguineus s.l., the most commonly reported tick worldwide, and an exclusive, possible, or putative vector of several tick-borne pathogens reported here6. Importantly, the brown dog tick can occasionally feed on humans and other animals, including production animals and wildlife, posing the risk of zoonotic transmission.

Some pathogen species were not detected at both the genus-specific and species-specific levels in any of the canine samples analyzed. A possible explanation for the negative results is that some pathogen targets included in the assay may be non-endemic in Chad (e.g., Borrelia burgdorferi) or may circulate at low ct values. In addition, due to the comprehensive nature of the tNGS test, the targeted panel includes diversity of VBPs, including those that infect other species (e.g., Cytauxzoon felis infects cats) and not just canine VBPs. Finally, the whole blood as utilized in this study may not be the ideal sample for Leishmania testing, as the parasite load in blood is often low, challenging detection. Tissue samples such as bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes should be used instead. We acknowledge a few limitations in this study. First, the samples were collected once, therefore, the prevalence data provided here would have benefited from multiple sampling events over different seasons. Second, the tNGS method used here is known to have a slight reduction in analytical sensitivity as compared to real-time PCR24. When VBPs are in circulation at low amounts (Ct values ≥ 35), detection may be missed with this technique. Finally, it must be noted that the age of the dogs included in the study was reported by their owner, and could have been inaccurate, potentially impacting our analyses.

Conclusion

The epidemiological analysis performed in this study has confirmed the high prevalence of canine VBPs in this population of dogs using tNGS. This diagnostic method allowed for comprehensive and simultaneous detection of multiple agents, including hemotropic mycoplasmas which had not been previously reported in Chad. Furthermore, the results suggest that clinicians and diagnostic labs should not exclude bacteria belonging to Mycoplasmataceae during VBP surveillance. Multivariable logistic regression revealed a strong association between the prevalence of A. platys, E. canis and C. M. haematoparvum with seniors and residents in Chari Baguirmi south. Network analysis revealed a complex web of antagonistic and synergistic interactions among pathogens within dogs in Chad with potential public health implications. It is imperative for health professionals in Chad to strengthen awareness of these pathogens circulating in dogs, and possibly in humans. Risk of exposure to these VBPs can be minimized through the availability of veterinary care, appropriate use of ectoparasiticidal treatment, and continued pathogen and vector surveillance. Nevertheless, we believe that this work provides an in-depth and standardized VBP report from Chad and that the information provided in this study will serve as baseline data for future investigations in this region.

Data availability

Data availability: The fasta file and bed file used for the analysis can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pathogens13040335/s1, File S1: A FASTA file containing the genomic sequence of the targeted pathogens; File S2: Gene target BED file of all the targeted pathogens. Raw data is available on request through the corresponding author.

References

Davitt, C. et al. Next-generation sequencing metabarcoding assays reveal diverse bacterial vector-borne pathogens of Mongolian dogs. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 5, 100173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpvbd.2024.100173 (2024).

Kayali, U. et al. Incidence of canine rabies in n’djaména, Chad. Prev. Vet. Med. 61, 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2003.07.002 (2003).

Shaw, S. E., Day, M. J., Birtles, R. J. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. Tick-borne infectious diseases of dogs. Trends Parasitol. 17, 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1471-4922(00)01856-0 (2001).

Colwell, D. D., Dantas-Torres, F. & Otranto, D. Vector-borne parasitic zoonoses: emerging scenarios and new perspectives. Vet. Parasitol. 182, 14–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.07.012 (2011).

Walker, A. R. Ticks of domestic animals in Africa: a guide to identification of species. Biosci. Rep. 74 (2003).

Dantas-Torres, F. Biology and ecology of the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus. Parasit. Vectors. 3, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-3-26 (2010).

Saleh, M. N. et al. Show us your ticks: A survey of ticks infesting dogs and cats across the USA. Parasit. Vectors. 12, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3847-3 (2019).

Dantas-Torres, F., de Sousa-Paula, L. C. & Otranto, D. The Rhipicephalus sanguineus group: updated list of species, geographical distribution, and vector competence. Parasit. Vectors. 17, 540 (2024). https://doi.org/https://rdcu.be/ebRBD

Šlapeta, J., Chandra, S. & Halliday, B. The “tropical lineage” of the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato identified as Rhipicephalus linnaei (Audoin, 1826) Int. J. Parasitol. 51, 431–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2021.02.001 (2021).

Latrofa, M. S., Dantas-Torres, F., Annoscia, G., Cantacessi, C. & Otranto, D. Comparative analyses of mitochondrial and nuclear genetic markers for the molecular identification of Rhipicephalus spp. Infect. Genet. Evol. 20, 422–427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2013.09.027 (2013).

Selim, A., Megahed, A., Ben Said, M., Alanazi, A. D. & Sayed-Ahmed, M. Z. Molecular survey and phylogenetic analysis of Babesia vogeli in dogs. Sci. Rep. 12, 6988. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-11079-x (2022).

Ramos, R. A. N. et al. Occurrence of Hepatozoon canis and Cercopithifilaria bainae in an off-host population of Rhipicephalus sanguineus sensu lato ticks. Ticks Tick. Borne Dis. 5, 311–314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2013.12.005 (2014).

Fournier, P. E., Xeridat, B. & Raoult, D. Isolation of a Rickettsia related to Astrakhan fever Rickettsia from a patient in Chad. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 990, 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb07356.x (2003).

Mura, A. et al. Molecular detection of spotted fever group Rickettsiae in ticks from Ethiopia and Chad. Trans. R Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 102, 945–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.03.015 (2008).

Osip, S. et al. Prevalence and diversity of spotted fever group Rickettsia species in Ixodid ticks from domestic dogs in Chad, Africa. Ticks Tick. Borne Dis. 15, 102405. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2024.102405 (2024).

Barker, E. N. & Tasker, S. in Greene’s Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat 690–703 (Elsevier, 2021).

Huggins, L. G. et al. Transmission of haemotropic Mycoplasma in the absence of arthropod vectors within a closed population of dogs on ectoparasiticides. Sci. Rep. 13, 10143. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-37079-z (2023).

Lashnits, E., Grant, S., Thomas, B., Qurollo, B. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. Evidence for vertical transmission of Mycoplasma haemocanis, but not Ehrlichia ewingii, in a dog. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 33, 1747–1752. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.15517 (2019).

Huang, H. H. H. et al. Cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis clade ‘Sydney’) are dominant fleas on dogs and cats in New South Wales, Australia: presence of flea-borne Rickettsia felis, Bartonella spp. but absence of Coxiella burnetii DNA. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector Borne Dis. 1, 100045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpvbd.2021.100045 (2021).

Moonga, L. C. et al. Molecular detection of Rickettsia felis in dogs, rodents and cat fleas in Zambia. Parasit. Vectors. 12, 168. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3435-6 (2019).

Beus, K., Goudarztalejerdi, A. & Sazmand, A. Molecular detection and identification of hemotropic Mycoplasma species in dogs and their ectoparasites in Iran. Sci. Rep. 14, 580. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-51173-w (2024).

Peralta, J. A., Carithers, D. S., Beugnet, F. & Lappin, M. R. Fipronil and (S)-methoprene can lessen the risk of transmission of Bartonella clarridgeiae among cats with exposure to Ctenocephalides felis. Am. J. Vet. Res. 1, 1–6 (2024).

Haynes, E. et al. Surveillance of tick-borne pathogens in domestic dogs from Chad, Africa. BMC Vet. Res. 20, 417. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-024-04267-6 (2024).

Kattoor, J., Nikolai, E., Qurollo, B. & Wilkes, R. Targeted next-generation sequencing for comprehensive testing for selected vector-borne pathogens in canines. Pathogens 11, 964. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11090964 (2022).

Daniel, I. K. et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing reveals hemotropic mycoplasmas, Bartonella spp., and Babesia in shelter dogs from Texas, USA. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 63, 101297 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vprsr.2025.101297 (2025).

Butler, J. & Bingham, J. Demography and dog-human relationships of the dog population in Zimbabwean communal lands. Vet. Rec. 147, 442–446. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.147.16.442 (2000).

Czupryna, A. M. et al. Ecology and demography of free-roaming domestic dogs in rural villages near Serengeti National park in Tanzania. PLoS One. 11, e0167092. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167092 (2016).

Hovorka, A. & Van Patte, L. The lives of domestic dogs (Canis africanis) in Botswana. Pula: Botsw. J. Afr. Stud. 31, 53–64 (2017).

Csardi, G. & Nepusz, T. The Igraph software. Complex. Syst. 1695, 1–9 (2006).

Bastian, M., Heymann, S. & Jacomy, M. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. 361–362.

de Souza, W. M. & Weaver, S. C. Effects of climate change and human activities on vector-borne diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 476–491. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-024-01026-0 (2024).

Molaei, G., Eisen, L. M., Price, K. J. & Eisen, R. J. Range expansion of native and invasive ticks: A looming public health threat. J. Infect. Dis. 226, 370–373. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiac249 (2022).

Pattnayak, K. C. et al. Changing climate over Chad: is the rainfall over the major cities recovering? Earth Space Sci. 6, 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019EA000619 (2019).

Kamani, J. et al. Molecular detection and characterization of tick-borne pathogens in dogs and ticks from Nigeria. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7, e2108. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002108 (2013).

Heylen, D. et al. A community approach of pathogens and their arthropod vectors (ticks and fleas) in dogs of African sub-Sahara. Parasit. Vectors. 14 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-05014-8 (2021).

Aikaterini Alexandra, D., Angela Monica, I., Keshav, J., Călin Mircea, G. & Andrei Daniel, M. Molecular confirmation of Hepatozoon canis in Mauritius. Acta Trop. 177, 116–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.10.005 (2018).

Chatanga, E. et al. Molecular detection and characterization of tick-borne hemoparasites and Anaplasmataceae in dogs in major cities of Malawi. Parasitol. Res. 120, 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-020-06967-y (2021).

Cleveland, C. A. et al. Multi-season survey of Ixodid tick species collected from domestic dogs in Chad, Africa. Vet. Parasitol. Reg. Stud. Rep. 57, 101165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vprsr.2024.101165 (2025).

Schäfer, I. et al. First evidence of vertical Hepatozoon canis transmission in dogs in Europe. Parasit. Vectors. 15, 296. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05392-7 (2022).

Matjila, P., Penzhorn, B., Bekker, C., Nijhof, A. & Jongejan, F. Confirmation of occurrence of Babesia canis vogeli in domestic dogs in South Africa. Vet. Parasitol. 122, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.03.019 (2004).

Inokuma, H. et al. Epidemiological survey of Babesia species in Japan performed with specimens from ticks collected from dogs and detection of new Babesia DNA closely related to Babesia odocoilei and Babesia divergens DNA. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 3494–3498. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.41.8.3494-3498.2003 (2003).

Criado-Fornelio, A., Martinez-Marcos, A., Buling-Saraña, A. & Barba-Carretero, J. Molecular studies on Babesia, Theileria and Hepatozoon in Southern Europe: part I. Epizootiological aspects. Vet. Parasitol. 113, 189–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4017(03)00078-5 (2003).

Birkenheuer, A. J., Levy, M. G. & Breitschwerdt, E. B. Development and evaluation of a seminested PCR for detection and differentiation of Babesia gibsoni (Asian genotype) and B. canis DNA in canine blood samples. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 4172–4177. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.41.9.4172-4177.2003 (2003).

M’ghirbi, Y. & Bouattour, A. Detection and molecular characterization of Babesia canis vogeli from naturally infected dogs and Rhipicephalus sanguineus ticks in Tunisia. Vet. Parasitol. 152, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.12.018 (2008).

Obeta, S. S. et al. Prevalence of canine babesiosis and their risk factors among asymptomatic dogs in the federal capital territory, Abuja, Nigeria. Parasite Epidemiol. Control. 11, e00186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parepi.2020.e00186 (2020).

Kamani, J. Molecular evidence indicts Haemaphysalis leachi (Acari: Ixodidae) as the vector of Babesia rossi in dogs in Nigeria, West Africa. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 12, 101717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ttbdis.2021.101717 (2021).

Yabsley, M. J. et al. Prevalence of Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma platys, Babesia canis vogeli, Hepatozoon canis, Bartonella vinsonii berkhoffii, and Rickettsia spp. in dogs from Grenada. Vet. Parasitol. 151, 279–285 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.11.008 (2008).

Cardoso, L. et al. Molecular investigation of tick-borne pathogens in dogs from Luanda, Angola. Parasit. Vectors. 9, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-016-1536-z (2016).

Abdullah, H. H. et al. Multiple vector-borne pathogens of domestic animals in Egypt. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 15, e0009767. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0009767 (2021).

Tadesse, H. et al. Epidemiological survey on tick-borne pathogens with zoonotic potential in dog populations of Southern Ethiopia. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 8, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8020102 (2023).

Wyk, C. L. et al. Detection of ticks and tick-borne pathogens of urban stray dogs in South Africa. Pathogens 11, 862. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens11080862 (2022).

Mesquita, J. R. et al. Hemotropic Mycoplasma and Bartonella species diversity in free-roaming canine and feline from Luanda, Angola. Pathogens 10, 735 (2021).

Aquino, L. C. et al. Analysis of risk factors and prevalence of haemoplasma infection in dogs. Vet. Parasitol. 221, 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2016.03.014 (2016).

Barker, E. et al. Development and use of real-time PCR to detect and quantify Mycoplasma haemocanis and Candidatus Mycoplasma haematoparvum in dogs. Vet. Microbiol. 140, 167–170 (2010).

Inokuma, H. et al. Epidemiological survey of Ehrlichia canis and related species infection in dogs in Eastern Sudan. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1078, 461–463. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1374.085 (2006).

Novacco, M. et al. Chronic Candidatus Mycoplasma turicensis infection. Vet. Res. 42, 59. https://doi.org/10.1186/1297-9716-42-59 (2011).

Soto, F. et al. Occurrence of canine hemotropic Mycoplasmas in domestic dogs from urban and rural areas of the Valdivia province, Southern Chile. Comp. Immunol. 50, 70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cimid.2016.11.013 (2017).

Obara, H., Fujihara, M., Watanabe, Y., Ono, H. K. & Harasawa, R. A feline hemoplasma, Candidatus Mycoplasma haemominutum, detected in dog in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 73, 841–843. https://doi.org/10.1292/jvms.10-0521 (2011).

Alexander, J. E., Colyer, A., Haydock, R. M., Hayek, M. G. & Park, J. Understanding how dogs age: longitudinal analysis of markers of inflammation, immune function, and oxidative stress. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 73, 720–728. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glx182 (2018).

Maharana, P., Abdel-Lathif, A. Y. & Pattnayak, K. C. Observed climate variability over Chad using multiple observational and reanalysis datasets. Glob Planet. Change. 162, 252–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloplacha.2018.01.013 (2018).

Hazelrig, C. M. et al. Spatial and risk factor analyses of vector-borne pathogens among shelter dogs in the Eastern United States. Parasit. Vectors. 16, 197. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-05813-1 (2023).

Scandurra, A., Alterisio, A., Di Cosmo, A. & D’Aniello, B. Behavioral and perceptual differences between sexes in dogs: an overview. Animals 8, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8090151 (2018).

Borchelt, P. L. Aggressive behavior of dogs kept as companion animals: classification and influence of sex, reproductive status and breed. Appl. Anim. Ethol. 10, 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3762(83)90111-6 (1983).

Narasimhan, S. & Fikrig, E. Tick microbiome: the force within. Trends Parasitol. 31, 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pt.2015.03.010 (2015).

Gomez-Chamorro, A., Hodžić, A., King, K. C. & Cabezas-Cruz, A. Ecological and evolutionary perspectives on tick-borne pathogen co-infections. Curr. Res. Parasitol. Vector-Borne Dis. 1, 100049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpvbd.2021.100049 (2021).

Sevinc, F. et al. Haemoparasitic agents associated with ovine babesiosis: A possible negative interaction between Babesia ovis and Theileria ovis. Vet. Parasitol. 252, 143–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2018.02.013 (2018).

Bashey, F., Hawlena, H. & Lively, C. M. Alternative paths to success in a parasite community: within-host competition can favor higher virulence or direct interference. Evolution 67, 900–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01825.x (2013).

Díaz-Corona, C. et al. Microfluidic PCR and network analysis reveals complex tick-borne pathogen interactions in the tropics. Parasit. Vectors. 17, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-023-06098-0 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank The Carter Centre for financing this work. The authors also acknowledge the statistical insights provided by the TAMU Department of Statistics. We also would like to thank Dr. Ana Clara M. Pessoa Monteiro for her insights on QGIS software.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization and study design, G. G.V, R.G., L.T., and M.N.S. Methodology including bioinformatics, R.A.N., H.H., J.K., R.W., P.T.O., R.N.B.N. Statistical analysis and preparation of the first draft, I.K.D. Manuscript writing – original draft, I.K.D. Manuscript writing – editing and review I.K.D., R.A.N., H.H., J.K., R.W., R.G., L.T., M.N.S., and G.V. Funding acquisition G.G.V. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Daniel, I.K., Hakimi, H., Ramos, R.A.N. et al. High prevalence of vector-borne protozoa and bacteria in dogs from Chad determined using a targeted next-generation sequencing approach. Sci Rep 15, 28215 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13431-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13431-3