Abstract

With the development of railway transportation and the advancement of deep learning, object detection algorithms are increasingly replacing manual inspection of track fasteners. However, current algorithms struggle with low accuracy in complex weather conditions or low-contrast backgrounds. To address this, we propose a track fastener defect detection algorithm based on YOLOv11 (You Only Look Once).First, we incorporate the DHSA (Dynamic-range Histogram Self-Attention) module into the backbone network of YOLOv11 to enhance noise robustness. Second, we introduce the BRA (Bi-Level Routing Attention) sparse attention mechanism into the neck network for improved efficiency. Finally, we add the PPA (Parallelized Patch-Aware Attention) module to the original neck network to enhance multi-scale feature extraction, specifically for small object detection.To validate the model, we created a dataset and conducted experiments. The experimental results show that YOLO-DRPA achieves a mAP@0.5 of 94.6% and a mAP@0.5:0.95 of 80.7%, marking improvements of 1.8% and 4.0% over YOLOv11n, respectively. The model also demonstrates competitive performance compared to other popular object detection algorithms, highlighting its potential to improve both detection accuracy and efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In recent decades, railway transportation has received extensive attention and experienced significant growth, aiming to further boost industrial production efficiency and accelerate socioeconomic development. However, this rapid growth has also led to an increase in potential safety hazards, which pose serious risks to industrial production and social stability. Track fasteners, essential components that connect railway tracks to sleepers, play a crucial role in maintaining track stability. The health of these fasteners directly affects the stability and efficiency of railway transportation. Unfortunately, track fasteners are prone to defects due to factors such as fatigue from prolonged use, uneven stress on the tracks, and adverse weather conditions. Common defects include breaks, lack of fastening, rotation, among others1, which severely hinder the normal operation of railway systems.

Currently, there are various methods for detecting defects in railway track fasteners. Traditional manual inspection relies heavily on the experience and skills of inspectors2, but it is inefficient and subject to human error, leading to missed or false detections. As a result, image-processing-based machine learning methods have emerged as alternatives to manual detection. These methods often use hand-crafted feature extraction algorithms and classifiers such as SIFT3 (Scale-Invariant Feature Transform), SURF4 (Speeded-Up Robust Features), and HOG5 (Histogram of Oriented Gradients). While these approaches offer improved efficiency and stability compared to manual inspection, their performance is still limited by the accuracy and robustness of the algorithms. Consequently, deep-learning-based methods, particularly those employing CNNs6 (Convolutional Neural Networks) and RCNNs7 (Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks), have gained widespread application.

Deep learning-based object detection primarily falls into two categories: two-stage and one-stage algorithms. Two-stage algorithms first generate candidate regions with target probabilities and then process these regions through ROI (Region of Interest) Pooling. Notable examples of this approach include RCNN and Faster RCNN8 (Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Network). In contrast, one-stage algorithms treat detection as a regression task, directly predicting target categories and bounding boxes from images. Examples of one-stage algorithms include YOLO9 and SSD10 (Single Shot MultiBox Detector). Feng Guo et al. developed the YOLOv4-hybrid11 model, which builds upon YOLOv4 to enable portable, high-speed track detection. While two-stage algorithms excel in accuracy, one-stage algorithms are typically faster. Additionally, Feng Guo et al. proposed RailFormer12, a Transformer-based model designed for precise pixel-level RSD (Rail Surface Defects) detection in the railway industry. Furthermore, multi-sensor data fusion13, such as the use of millimeter-wave radar, has been adopted to enhance detection performance, although this approach comes with higher hardware costs.

In general, defect detection of railway track fasteners involves a variety of methods, with deep learning-based approaches showing promising comprehensive performance and application potential. Considering specific challenges in railway track fastener defect detection, such as the unavoidable impact of weather conditions (e.g., rainy days, nighttime, tunnel environments), the low proportion of fastener targets in input detection images causing inefficient computation in traditional undifferentiated attention mechanisms, and the small size of fastener targets leading to the loss of important details during traditional feature extraction and downsampling, we propose an innovative model, YOLO11-DRPA, based on YOLO11. By incorporating the DHSA module14, BRA module15, and PPA module16, the model’s ability to address these challenges is improved. Specifically, the DHSA module added to the backbone network groups input images by gray levels and applies BHR (Bin-wise Histogram Reshaping) and FHR (Frequency-wise Histogram Reshaping) to enhance sensitivity to both global and local features, reducing weather noise interference and improving adaptability to tunnel environments. The BRA module in the neck network performs spatial division and sparse attention processing on fastener images, filtering out irrelevant information and helping optimize computing power usage. The PPA module, also in the neck network, uses pointwise convolution to partition input data into distinct feature groups, helping mitigate feature loss during downsampling and enhancing the model’s sensitivity to fasteners.

Methods

Dataset

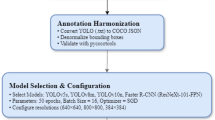

Currently, datasets related to track fastener defects are relatively limited, and due to confidentiality concerns, most railway data are not publicly accessible. As a result, the track fastener dataset used in this study was sourced from Jinhua Railway Station in Zhejiang. It took approximately three months to capture 1,489 fastener images with a resolution of 4032 × 3024 from different angles and heights, under various weather conditions, using a manual camera. These images cover different fastener categories, including normal, rotation, lack, and break, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Additionally, real-world scenarios such as rainy days and low-light tunnel conditions were simulated to account for various lighting and occlusion challenges typically encountered in track detection tasks.

To increase the dataset size and ensure the sample distribution reflects real-world conditions, we applied several data augmentation techniques, including image position transformation, noise addition, and adjustments to brightness and contrast. Subsequent experiments have demonstrated that variations in the sample size do not significantly affect the model’s detection performance. After screening and labeling, the dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets following an 8:1:1 ratio.

Experimental setup

In this study, we used Ubuntu 20.04 as the operating system and the PyTorch framework for model training. The software setup included PyTorch 2.0.1, CUDA 11.8, and CUDNN 8.7.0. The hardware configuration consisted of an AMD Ryzen 9 5900HX with Radeon Graphics x 16 and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 with 6GB of memory. For data augmentation, we utilized Albumentations17. New images were generated by stitching four different images together, along with applying transformations such as rotation, translation, and cropping. The experimental setup was configured with the following parameters: no pre-trained weights, a total of 300 epochs, a batch size of 16, an input image resolution of 640 × 640, and a cosine annealing learning rate strategy18.

YOLO-DRPA

YOLO-DRPA striction

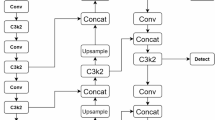

The network structure of YOLO11 is divided into three parts: the backbone network, the neck network, and the output head. The backbone network is composed of four modules, namely Conv, C3k2, SPPF, and C2PSA. It generates rich feature tensors by gradually reducing the spatial resolution of the image and increasing the number of channels, and is mainly responsible for extracting features of the input image and capturing image information. The neck network is located between the backbone network and the output head, and its main part is the PAN (Path Aggregation Network), which is responsible for further enhancing and fusing the feature tensors output by the backbone network to provide better input for the output head. The output head is responsible for receiving the data output by the neck network and generating the final prediction results. It consists of three independent output heads, which respectively process feature maps of large, medium, and small sizes to meet the object detection requirements of different sizes. Finally, the network outputs a high-dimensional tensor containing category, confidence, and position coordinate information.

On this basis, we added the DHSA module to the backbone network and the BRA module and PPA module to the neck network. The specific network structure is shown in Fig. 2.

YOLO-DRPA backbone

In order to enhance the robustness of the model against the degradation factors caused by the inevitable weather environments (such as rainy days, nights, railway track tunnels, etc.) during the detection of railway track fasteners, including image noises like occlusions and changes in brightness19, we have introduced the DHSA module into the backbone network. The network structure of the DHSA module is shown in Fig. 3. It improves the model’s robustness to environmental noises through dynamic range convolution and a dual-path histogram self-attention mechanism.

In the dynamic range convolution, this module conducts convolution within a dynamic range on the input image. For a dynamic input feature \(\:\text{F\:}\in {\text{R}}^{{W\:\times H\:\times C}}\), where \(\:{W\:\times H}\) represents the spatial scale and \(\:C\) represents the number of channels, it is equally divided along the channel dimension into intermediate feature tensors \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{1}} \in {\text{R}}^{{W\:\times H\:\times }\frac{\text{C}}{\text{2}}}\) and \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{2}} \in {\text{R}}^{{W\:\times H\:\times }\frac{\text{C}}{\text{2}}}\). The grayscale values of the data in the \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{1}}\) branch are sorted horizontally and vertically, and then connected with \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{2}}\) to obtain the adaptively processed feature \(\:{\text{F}}^{{\prime\:}}\), as shown in Eq. (1):

where, \(\:{\text{Conv}}_{{1\times 1}}\) denotes the \(\:{1\times 1}\) pointwise convolution operation; \(\:{\text{Conv}}_{{3\times 3}}^{\text{d}}\) represents the\({3\times 3}\) depthwise convolution operation; Concat refers to the operation of concatenating along the channels; Split stands for the operation of splitting along the channels; and \(\:{\text{Sort}}_{\text{i} \in \left(\text{h,\:\:v}\right)}\) indicates the operation of arranging in the horizontal (h) or vertical (v) direction.

Subsequently, through depthwise separable convolution, the convolution operation is enabled to compute across dynamic ranges. This process organizes pixels of varying intensities into regular patterns, allowing convolution kernels to focus on preserving clean information and restoring degraded features respectively, thereby reducing noise interference.

In the dual-path histogram self-attention mechanism, for the output of the dynamic range convolution, the query-key pairs are first sorted and then passed to the two branches based on the index arrangement, which is used to extract local and global features simultaneously, as shown in Eq. (2).

where, \(\:{\text{R}}_{{H\:\times \:W\:\times \:C}}^{{HW\:\times C}}\) represents the reshaping of the feature tensor from \(\:{\text{R}}^{{H\:\times \:W\:\times \:C}}\) to \(\:{\text{R}}^{{HW\:\times \:C}}\), d is the index of the permutation value, and Gather denotes the retrieval of tensor elements from the given indices.

Finally, the dual-branch architecture employs BHR and FHR for feature reshaping. In the BHR branch, the number of bins is denoted as \(\:{\text{B}}_{\text{b}}\), with each bin containing \(\:\frac{\text{HW}}{\text{B}}\) features. Large-scale information is extracted from bins containing a large number of dynamically positioned pixels, covering a broader intensity range to integrate global features and prevent the model from being misled by local noise. In the FHR branch, the frequency per bin is denoted as \(\:{\text{B}}_{\text{f}}\), and the number of bins is set to \(\:\frac{\text{HW}}{\text{B}}\). Fine-grained information is extracted from bins with fewer spatially adjacent pixels, focusing on a limited number of pixels to enhance the perception of detailed features and help identify details obscured by noise. The query-key features from both branches are reshaped accordingly and passed through a self-attention mechanism to capture long-range spatial dependencies and distinguish background from noise. The resulting attention maps \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{b}}\) and \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{f}}\) are multiplied element-wise to obtain the final attention map \(\:\text{A}\), as shown in Eq. (3).

Here, \(\:\text{k}\) represents the number of self - attention heads. \(\:{\text{R}}_{\text{i}\in\left(\text{b,f}\right)}\) stands for the reshaping methods BHR or FHR. \(\:{\text{A}}_{\text{i} \in \left(\text{b,f}\right)}\) denotes the attention maps obtained from the branches. \(\:\text{A}\) is the fusion result of the branch attention maps, and \(\odot\) represents element - wise multiplication.

YOLO11-DRPA nect

The original neck network of YOLO11n uses C3k2 and Conv modules (structure in Fig. 2), enabling bidirectional feature transmission20. However, its simple summation - based fusion treats all image data equally, mixing valid and invalid information. In track fastener detection, this wastes computational resources and reduces efficiency due to large - sized input images. We thus introduce the BRA module with a sparse attention mechanism to boost the model’s real - time performance.

The working process of the BRA module, as depicted in Fig. 4, mainly encompasses region division and input projection, region-to-region routing, and token-to-token attention. For an input image \(\:\text{F}\in{\text{R}}^{{H\:\times \:W\:\times \:C}}\), region division splits it into \(\:\text{S}\times \text{S}\) non-overlapping regions. Different spatial scales such as \({4\times 4}\), \(\:\text{7}\times \text{7}\), and \(\:1\text{4}\times \text{1}\text{4}\) are commonly used for region division. Smaller scales provide more detailed local information, but an excessive number of regions increases routing overhead and may neglect long-range dependencies. Larger scales reduce computational load, yet information redundancy within regions may weaken feature representation. Therefore, a \(\:\text{7}\times \text{7}\) size is typically chosen to balance local details and global context. Following this, the image data of each region \(\:{\text{F}}^{{\prime\:}} ={\text{R}}^{\frac{\text{H}}{\text{S}}\times \frac{\text{W}}{\text{S}}\times \text{C}}\) undergoes input projection using the projection matrices \(\:\omega _{{0\:~\:S\:\times \:S}}^{\text{V}}\), \(\:\omega _{{0\:~\:S\times S}}^{\text{K}}\), and \(\:\omega _{{0\:~\:S\:\times S}}^{\text{Q}}\) to generate value, key, and query tensors \(\:\text{V\:}\in {\text{R}}^{{S\:\times \:S}}\), \(\:\text{K\:}\in{\text{R}}^{{S\:\times \:S}}\), and \(\:\text{Q\:}\in {\text{R}}^{{S\:\times \:S}}\). Subsequently, for region-to-region routing, a region affinity matrix is calculated and pruned to retain only the top k connections of each region, adaptively determining the regions of interest and routing indices, which significantly cuts down computation compared to traditional routing methods. Finally, in the token-to-token attention stage, key-value pairs from regions with higher affinity are collected and fused, yielding tensors \(\:{\text{V}}^{\text{g}} \in {\text{R}}^{\frac{\kappa \text{H\:W}}{{\text{S}}^{\text{2}}}}\), \(\:{\text{K}}^{\text{g}} \in {\text{R}}^{\frac{\kappa \text{H\:W}}{{\text{S}}^{\text{2}}}}\), and \(\:\text{Q\:}\in {\text{R}}^{{S\:\times \:S}}\) to effectively tackle the issues of low-resolution targets and spatial ambiguity in track fastener detection.

By collecting key-value pairs from regions with high affinity and filtering out most irrelevant ones at the coarse-grained region level, fine-grained token-to-token attention calculation is performed only within a few relevant regions. This enables the model to precisely focus on semantically relevant key-value pairs, effectively addressing the challenges of low target resolution ratios and spatial ambiguity in fastener detection engineering.

To address the issue that key information of small fastener targets is likely to be lost during multiple downsampling operations21, we further introduce the PPA module into the original neck network. The PPA module employs a multi-branch parallel feature extraction method at different levels, and the complete network is shown in Fig. 5.

The overall workflow is as follows: For the input feature tensor \(\:\text{F}\in{\text{R}}^{{H\times \:W\times \:C}}\), three parallel branches are constructed via point convolution adjustment to capture local features, global features, and perform multi-level convolution, respectively. In the local and global branches, feature extraction at different scales is achieved by controlling the patch size parameter \(\:\text{p}\), involving operations such as partitioning \(\:\text{F}\), channel averaging, linear computation, activation function processing, and feature selection. The serial convolution branch employs three \(\:{3\:\times 3}\) convolutional layers instead of traditional convolutions to generate outputs. The resulting three-branch feature tensors \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{local}}\in{\text{R}}^{{H\times \:W\times C}}\), \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{global}}\in{\text{R}}^{{H\times \:W\times \:C}}\), and \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{conv}}\in{\text{R}}^{{H\times \:W\times \:C}}\) are summed to form the intermediate feature tensor \(\:{\text{F}}^{{\prime\:}}\in{\text{R}}^{{H\times \:W\times \:C}}\). Finally, unlike the traditional FPN(Feature Pyramid Network) structure that simply fuses features across layers, the PPA module enhances the summed result with dedicated attention mechanisms for adaptive feature enhancement, emphasizing features relevant to small targets. The attention mechanism operates as follows: \(\:{\text{F}}^{{\prime\:}}\) first passes through the Channel Attention Module (CAM) to generate a one-dimensional channel attention map, denoted as \(\:{\text{M}}_{\text{c}}\left({\text{F}}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\). This map is then multiplied element-wise with \(\:{\text{F}}^{{\prime\:}}\) to produce the channel attention tensor \(\:{\text{F}}^{{\prime\prime}}\), as shown in Eq. (4). Subsequently, \(\:{\text{F}}^{{\prime\prime}}\) serves as the input to the Spatial Attention Module (SAM). After processing through SAM, a two-dimensional spatial attention map \(\:{\text{M}}_{\text{s}}\left({\text{F}}^{{\prime\prime}}\right)\) is obtained. This map is multiplied element-wise with \(\:{\text{F}}^{{\prime\prime}}\) to yield the final output feature \(\:{\text{F}}_{\text{o}}\), as expressed in Eq. (5).

The PPA module captures multi-scale features of objects through a multi-branch feature extraction strategy and enhances these features using dedicated attention mechanisms. This ensures that the information of small fastener objects is better preserved and enhanced within the network, thereby improving the accuracy of defect detection for track fasteners.

Here, \(\:{\text{F}}^{{\prime\prime}}\) represents the image data output by the addition of parallel branches. \(\:{\text{M}}_{\text{c}}\in{\text{R}}^{{1\times \:1\times \:}{\text{C}}^{{\prime\:}}}\) represents the operation of generating a one - dimensional channel attention map through the CAM22. \(\:{\text{M}}_{\text{s}}\in{\text{R}}^{{\text{H}}^{{\prime\:}}\times {\text{W}}^{{\prime\:}}\times \text{1}}\) represents the operation of generating a two - dimensional spatial attention map through the SAM23. \(\:\otimes\:\) represents the element - wise multiplication calculation.

Loss function

YOLO11 - DRPA adopts a comprehensive loss function24, which includes bounding box regression loss, classification loss, and confidence loss. As shown in Eq. (8).

Here, Loss represents the total loss function. \(\:{\text{Box}}_{\text{loss}}\) denotes the bounding box regression loss, \(\:{\text{Cls}}_{\text{loss}}\) represents the classification loss, and\(\:{\text{Dfl}}_{\text{loss}}\) indicates the confidence loss.

Bounding box regression loss optimizes the difference between predicted and ground - truth bounding boxes. It has two components: center point coordinate loss and width - height loss, with the principle in Eq. (9).

where, S is the grid size, B is the number of bounding boxes per grid cell. \(\:{\text{1}}_{\text{ij}}^{\text{obj}}\) indicates if the j - th box in the i - th cell predicts an object. x and \(\:y\) are are box center coords, w and h are its width and height, and \(\:{\lambda}_{\text{coord}}\) is a weight coefficient for balancing losses.

The classification loss is typically calculated using the cross - entropy loss. It is used to measure the difference between the probability distribution predicted by the model and the true labels, aiming to determine which category the target belongs to. The specific form is shown in Eq. (10).

Here, \(\:{\text{p}}_{\text{i}}\left(\text{c}\right)\) is the probability that the model predicts the target in the i - th grid cell belongs to class c, and \(\:{\text{p}}_{\text{i}}^{{\prime\:}}\left(\text{c}\right)\) is the true label, indicating whether the target in the i - th grid cell belongs to class c. \(\:{\text{y}}_{\text{ic}}\) is the true label of the i - th sample, and \(\:{\text{p}}_{\text{ic}}\) is the probability that the i - th sample belongs to class c. \(\alpha\) is the balancing factor used to adjust the weights between positive and negative samples, and \(\gamma\) is the focusing parameter used to control the degree of attention to difficult samples.

The confidence loss function is often combined with traditional cross - entropy loss to boost the model’s learning of hard samples. Its core is to weight category prediction probabilities, making the model focus more on misclassifiable samples. The specific formula is in Eq. (11).

Results

Evaluation method

In our study, to rigorously evaluate the model’s performance, we sampled 50 datasets for each experiment and conducted statistical analysis after removing the highest and lowest values. The metrics employed include Precision (P), Recall (R), Average Precision (AP), mean Average Precision (mAP)25, Standard Deviation (SD), model size parameters, and Frames Per Second (FPS). P represents the accuracy of target recognition, R denotes the recall rate, AP is the average precision calculated as the area under the Precision-Recall curve for each class, and mAP is the mean of individual APs across all classes. SD measures the standard deviation of mAP values. Additionally, we used a representative GPU device, the NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 GPU (NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA), which aligns with the computational capabilities of modern edge devices, to assess model size and FPS, thereby quantifying the model’s lightweight characteristics for downstream applications such as embedded systems. The mathematical formulations of P, R, AP, and mAP are presented in Equations (12) to (15).

Here, \(\:\text{TP}\) represents the correctly predicted true positive instances, \(\:\text{FP}\) represents the false positive instances with inaccurate predictions, \(\:\text{FN}\) represents the falsely predicted false negative instances, and \(\:\text{C}\) represents the classes in the dataset.

Ablation and comparative experiment

In this stage, we first carried out a series of ablation experiments by combining various modules differently to verify the collaborative optimization among them. The experimental results show that whether added individually or in combination, each module can improve the model’s performance in different dimensions to some extent. For example, the PPA module optimizes the problem of information loss during traditional multiple downsampling through parallel multi-branch feature extraction. The BRA module introduces a sparse attention mechanism, constructs a region-level affinity graph, and performs pruning to improve the efficiency of attention calculation. The DHSA module convolves pixel features of images within a dynamic range to extract large-scale and fine-grained information and fuses the outputs. All these modules enable the model to extract and retain rich spatial features, effectively improving the model’s detection accuracy. However, there are still some deficiencies in the engineering of fastener detection. The detailed experimental data are presented in Table 1.

Combination of single modules. The PPA module has the greatest improvement on the model precision P, increasing by 2.6% to reach 97.0%. However, the recognition accuracy for the target objects of Rotation and Lack decreases to 97.6% and 73.2%, respectively. In contrast, the BRA module has almost no improvement on the model precision P, but it enhances the recognition accuracy for various categories. Specifically, the recognition accuracy for the Lack category increases to 76.8%. Additionally, the DHSA module reduces the overall precision P, but it significantly improves the mean Average Precision (mAP) in the range of 0.5 to 0.95 for target recognition, reaching 80.1%, thus enhancing the confidence in the detection of fastener targets. In conclusion, the three modules all have a certain promoting effect on YOLO11, but they also have their own limitations.

For the fusion of dual modules, the combination of the PPA module and the BRA module further improves the model precision to 98.6%. It also enhances the recognition accuracy for Lack instances, reaching 76.5%. However, the average confidence of the fastener detection results decreases. The combinations of the other two groups also yield results similar to the above, indicating that the simple stacking of modules does not always improve the model performance, and an organic combination is required.

Finally, the joint effect of the three modules achieves the overall best performance. Although the standard deviation of each group of data is similar, and the improvement effect of our model in terms of overall recognition accuracy is relatively low, it reaches the best upper level in the recognition accuracy of each category. Moreover, it has the highest improvement in mAP0.5 and mAP0.5:0.95, increasing by 1.8% and 4.0% respectively compared with the original YOLO11 network, reaching 94.6% and 80.7%. While increasing the model size slightly, it improves the comprehensive performance of the model. The specific detection results are shown in Fig. 6.

Although the improved model has a decrease of 9.7 in terms of FPS, it reaches 38.5 and still meets the work requirements in the fastener detection project26. Moreover, in the fastener detection project, higher precision can better identify potential risks. In addition, with the enhancement of the computing power of edge devices, it is sufficient to optimize the calculation speed of the model.

To verify the performance and generalization of YOLO11-DRPA, we tested it on the training dataset and an unseen one, comparing it with Rtdetr27, PP-YOLOE-S28, and YOLOX variants, which are current mainstream object detection models. On the training dataset, YOLO11-DRPA achieved 95.4% accuracy and 93.5% regression rate, with a notable boost in regression rate over other models. It excelled in detecting rotation, normal, and damaged fasteners, and despite slightly lower performance in missing fastener detection than YOLO10n, it outperformed YOLO10n in regression rate and mAP0.5:0.95 by 3.2% and 3.4%, respectively, indicating higher stability. In the external dataset, its mAP0.5 reached 86.5%, the highest among all models, demonstrating strong generalization. The detailed experimental data are presented in Table 2.

Notwithstanding a marginal increment in model size and computational parameters, YOLO11-DRPA appears to yield discernible improvements in detection accuracy. Collectively, the results of this study indicate that the proposed YOLO11-DRPA model could potentially offer enhanced precision and comprehensive detection performance for railway track fastener inspection. It is hoped that this research can serve as a meaningful contribution to the ongoing efforts in advancing the methodologies within this specialized domain.

Conclusions

In this study, we propose the YOLO11-DRPA detection algorithm, an enhancement based on YOLO11n. By introducing the DHSA module into the backbone network, the model effectively fuses multi-scale image features and local-global information, improving its robustness against adverse weather conditions and environmental noise. The BRA module is integrated before the upsampling operation in the neck network, utilizing spatial scale segmentation and a regional self-attention mechanism to enhance operational efficiency. The PPA module is gradually added within the neck network. By leveraging weighted image attention in parallel branches, this module strengthens the model’s ability to detect small targets. Ablation experiments show that the synergistic integration of these modules achieves an optimal balance in network structure, leading to outstanding performance in the evaluation metrics of mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95. Comparative experiments with leading detection models demonstrate that, despite a moderate increase in model size, the proposed approach results in significant improvements in detection accuracy and stability. These findings suggest that the model strikes a promising balance between complexity and recognition performance when compared to similar algorithms.

Experimental results on the railway track fastener dataset show that the YOLO11-DRPA algorithm effectively addresses the challenges of improving both defect detection efficiency29 and accuracy30. While the model size increases moderately, future research will focus on optimizing model parameters to reduce complexity, computational costs, and enhance operational efficiency, all while maintaining detection accuracy and stability. These improvements are aimed at enabling the efficient deployment of the algorithm on resource-constrained embedded devices.

Data availability

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available. Due to the confidentiality agreements with our collaborating partners, sharing these data is restricted. However, further information or additional details may be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to approval from the collaborating partners and compliance with the terms of the confidentiality agreements.

References

Poveda, E., Rena, C. Y., Lancha, J. C. & Ruiz, G. A numerical study on the fatigue life design of concrete slabs for railway tracks. Eng. Struct. 100, 455–467 (2015).

Resendiz, E., Hart, J. M. & Ahuja, N. Automated visual inspection of railroad tracks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 14 (2), 751–760 (2013).

Cheung, W. & Hamarneh, G. N-sift: N-dimensional scale invariant feature transform for matching medical images. In 2007 4th IEEE international symposium on biomedical imaging: from nano to macro (pp. 720–723). IEEE. (2007), April.

Bay, H., Tuytelaars, T. & Van Gool, L. Surf: Speeded up robust features. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2006: 9th European Conference on Computer Vision, Graz, Austria, May 7–13, 2006. Proceedings, Part I 9 (pp. 404–417). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. (2006).

Dalal, N. & Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In 2005 IEEE computer society conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (CVPR’05) (Vol. 1, pp. 886–893). Ieee. (2005), June.

O’shea, K. & Nash, R. An introduction to convolutional neural networks. arxiv preprint arxiv:1511.08458. (2015).

Girshick, R., Donahue, J., Darrell, T. & Malik, J. Region-based convolutional networks for accurate object detection and segmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 38 (1), 142–158 (2015).

Siradjuddin, I. A. & Muntasa, A. Faster region-based convolutional neural network for mask face detection. In 2021 5th international conference on informatics and computational sciences (ICICoS) (pp. 282–286). IEEE. (2021).

Jiang, P., Ergu, D., Liu, F., Cai, Y. & Ma, B. A review of Yolo algorithm developments. Proc. Comput. Sci. 199, 1066–1073 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, October 11–14, 2016, Proceedings, Part I 14 (pp. 21–37). Springer International Publishing. (2016).

Feng Guo, Y. & Qian Yuefeng Shi.Real-time railroad track components inspection based on the improved YOLOv4 framework. Autom. Constr. 125, 10359 (2021).

Feng Guo, J., Liu, Y. & Qian Quanyi xie.rail surface defect detection using a transformer-based network. J. Ind. Inform. Integr. 38, 100584 (2024).

Abdu, F. J., Zhang, Y., Fu, M., Li, Y. & Deng, Z. Application of deep learning on millimeter-wave radar signals: A review. Sensors 21(6), 1951. (2021).

Zhou, F., Fu, Z. & Zhang, D. High dynamic range imaging with context-aware transformer. In 2023 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) (pp. 1–8). IEEE. (2023), June.

Zhu, L., Wang, X., Ke, Z., Zhang, W. & Lau, R. W. Biformer: Vision transformer with bi-level routing attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 10323–10333). (2023).

Xu, S. et al. Hcf-net: Hierarchical context fusion network for infrared small object detection. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. (2024), July.

Buslaev, A. et al. Albumentations: fast and flexible image augmentations. Information 11 (2), 125 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. The WuC-Adam algorithm based on joint improvement of warmup and cosine annealing algorithms. Math. Biosci. Eng. 21, 1270–1285 (2024).

Gupta, H., Kotlyar, O., Andreasson, H. & Lilienthal, A. J. Robust object detection in challenging weather conditions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (pp. 7523–7532). (2024).

Lavin, A. On the Efficiency of Convolutional Neural Networks. arxiv preprint arxiv:2404.03617. (2024).

Dumitrescu, D. & Boiangiu, C. A. A study of image upsampling and downsampling filters. Computers 8 (2), 30 (2019).

Wang, Q. et al. ECA-Net: Efficient channel attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 11534–11542). (2020).

Zhu, X., Cheng, D., Zhang, Z., Lin, S. & Dai, J. An empirical study of spatial attention mechanisms in deep networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision (pp. 6688–6697). (2019).

He, Y. et al. Bounding box regression with uncertainty for accurate object detection. In Proceedings of the ieee/cvf conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 2888–2897). (2019).

Kyriakis, J. M. et al. Raf-1 activates MAP kinase-kinase. Nature 358 (6385), 417–421 (1992).

Song, Q., Guo, Y., Jiang, J., Liu, C. & Hu, M. High-speed Railway Fastener Detection and Localization Method based on convolutional neural network. arxiv preprint arxiv:1907.01141. (2019).

Wang, S. et al. Phsi - rtdetr: A lightweight infrared small target detection algorithm based on UAV aerial photography. Drones 8 (6), 240 (2024).

Xu, S. et al. PP-YOLOE: An evolved version of YOLO. arxiv preprint arxiv:2203.16250. (2022).

Feng, H. et al. Automatic fastener classification and defect detection in vision-based railway inspection systems. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 63 (4), 877–888 (2013).

Wei, X. et al. Railway track fastener defect detection based on image processing and deep learning techniques: A comparative study. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 80, 66–81 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chengwei Zhang completed the vast majority of the research. Jiawei Zhu and Yihao Ma created the experimental dataset. Qingmei Huang finished the layout work of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Zhu, J., Ma, Y. et al. Studying the performance of YOLOv11 incorporating DHSA BRA and PPA modules in railway track fasteners defect detection. Sci Rep 15, 27698 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13435-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-13435-z