Abstract

Frailty has been linked to adverse health outcomes, but its relationship with stroke remains insufficiently understood in general populations. In this study, we examined the association between frailty and stroke using two nationally representative cohorts: the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Frailty was assessed using a multidimensional frailty index, analyzed both continuously and by category. Weighted logistic regression and restricted cubic spline models were applied. We found that higher frailty index scores were associated with greater odds of stroke in both populations, independent of demographic and clinical risk factors. The association appeared remained consistent in multiple sensitivity and subgroup analyses. Each 0.1-unit increase in the frailty index was associated with a 2.90-fold and 1.78-fold higher odds of stroke in NHANES and CHARLS, respectively. While CHARLS provides prospective evidence supporting the temporal relationship between frailty and stroke, the cross-sectional nature of NHANES limits causal inference. Overall, these findings suggest that frailty may be a useful marker for identifying individuals at higher risk of stroke. Further research is needed to validate its predictive utility and to explore whether modifying frailty can help reduce stroke incidence, particularly in aging populations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is a huge global health concern, significantly impacting morbidity and mortality rates around the globe1. The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that around 15 million individuals experience a stroke each year, resulting in 5 million fatalities and an additional 5 million individuals left with permanent disabilities2. The economic impact is also substantial. In the United States alone, stroke-related healthcare expenses, rehabilitation, and lost productivity amounted to over $46 billion between 2014 and 20153. Given the profound health and financial consequences, it is vital to investigate characteristics linked stroke risk to develop effective preventive strategies and improve health outcomes.

Although several well-established risk factors—such as hypertension, smoking, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia—are strongly associated with stroke, they do not account for all cases4. This gap highlights the necessity of recognizing further modifiable risk factors to enhance early intervention and potentially reduce stroke-related mortality, morbidity, and healthcare costs. Frailty, a clinical syndrome marked by diminished strength, endurance, and physiological function, increases an individual’s susceptibility to negative health consequences, including falls, disability, and death5. It is particularly prevalent among older adults and individuals with chronic diseases. Previous studies have shown that frailty is associated with both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular disease (CVD) outcomes6, as well as increased cardiovascular mortality7. However, while some research has examined components of frailty in relation to stroke, comprehensive investigations of frailty as a predictor of stroke remain limited.

Notably, a study by Daniela Renedo et al. identified a substantial correlation between frailty and stroke, though it relied on the Hospital Frailty Risk Score, a tool mainly designed for hospitalized patients8. In contrast, the frailty index (FI), which assesses the accumulation of health impairments in community settings, offers a more thorough examination of an individual’s health and has proven effective in predicting various negative health outcomes9,10. Despite its value in predicting various adverse events, the relationship between FI and stroke has not been thoroughly investigated in large, nationally representative populations.

To address this research gap, the present study utilized data from two complementary sources: the cross-sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the longitudinal China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). This study aimed to enhance understanding of the potential relationship between frailty and stroke. These findings may inform future hypothesis-driven research and support the development of early identification strategies for individuals at elevated risk, particularly in aging populations.

Methods

Data source and study population

NHANES is a comprehensive, nationally representative health survey conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and administered by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). It collects extensive health-related information through structured interviews and standardized physical examinations. Ethical approval was obtained from the CDC, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participation. CHARLS was used to validate findings longitudinally and explore temporal associations. It is a nationally representative cohort study of Chinese adults aged ≥ 45 years, with baseline data collected in 2011 and biennial/triennial follow-ups, capturing detailed demographic, socioeconomic, and health data through interviews and physical examinations. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University, with written informed consent obtained from all participants.

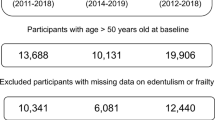

From NHANES 1999–2020 cycles (n = 116,878 initially), we excluded participants with unavailable stroke/frailty data (n = 52,655). All retained participants (n = 64,221) had complete age/sex/race data. After excluding those with zero examination weights (n = 3,358), the final analytical cohort included 60,863 participants (2,528 stroke cases; 58,335 non-cases). For CHARLS 2011–2020 waves (n = 45,111 initially), exclusions comprised those aged < 45 years or with missing stroke/frailty data (n = 1,073), missing sex/nationality (n = 256), and unavailable sampling weights (n = 418), yielding 43,355 participants (2,318 stroke cases; 41,037 non-cases) (Fig. 1).

Frailty index assessment

In this study, frailty was assessed using a frailty index (FI) based on the standard deficit accumulation approach proposed by Rockwood and Mitnitski11. The FI was constructed separately for NHANES and CHARLS datasets using available health-related variables across multiple domains.

In NHANES, the FI included 49 variables, encompassing physical functioning, cognitive status, depressive symptoms, comorbidities, healthcare utilization, physical performance, anthropometric measurements, and laboratory biomarkers. Each variable was coded as 0 (absence of deficit) or 1 (presence of deficit), and the FI was calculated by dividing the number of deficits present by the total number of considered variables, yielding a score between 0 and 112. In CHARLS, the FI was based on 35 variables, including limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) and instrumental ADLs, self-reported chronic conditions, psychological distress indicators, and self-rated health13. The index was constructed using the same procedure as in NHANES. The complete list of variables used in NHANES and CHARLS is presented in Supplementary Table 1. For both datasets, the FI was subsequently categorized into three groups for analysis: robust (FI ≤ 0.10), pre-frail (0.10 < FI < 0.25), and frail (FI ≥ 0.25)14.

Stroke diagnostic criteria

Stroke diagnoses in NHANES were ascertained based on participants’ responses to the questions, “MCQ160F: Have you ever been told you had a stroke?” or “SPQ070D: Have you ever been told you had a stroke?”15. In the CHARLS dataset, self-reported stroke was determined by participants’ answers to the question: “Have you ever been diagnosed with stroke by a doctor?”16.

Covariates

Based on prior literature and clinical relevance, covariates included: (1) Demographic and lifestyle factors: sex, age, household income/PIR, marital status, educational attainment, smoking and drinking status17; (2) body mass index (BMI, kg/m²); (3) Medical history: depressive symptoms, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus (DM); and (4) Laboratory biomarkers: C-reactive protein18, fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, low-density lipoprotein, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR)19.

To ensure comparability between NHANES and CHARLS datasets, age was treated as a continuous variable in multivariable logistic regression models, and as a categorical variable (< 65 and ≥ 65 years) in subgroup analyses. Sex was categorized as male or female. Educational attainment was grouped into two levels: below high school, and high school or above. Marital status was classified as married/partnered or other (including never married, separated, divorced, or widowed). Smoking and drinking statuses were categorized as never, former, or current, based on previous classifications. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared20,21.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using PHQ-9 (NHANES) and CES-D10 (CHARLS), with a cutoff of ≥ 10 indicating clinically relevant symptoms22,23. Hypertension was defined by physician diagnosis, antihypertensive medication use, or measured blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg24. Hyperlipidemia was defined based on lipid thresholds or lipid-lowering therapy. Diabetes was defined by self-reported diagnosis, medication use, or elevated glucose/HbA1c levels25.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics by stroke status. Continuous variables were presented as means with standard errors (SE), and categorical variables were reported as unweighted counts and percentages. To compare baseline characteristics among groups, t-tests were used for continuous variables, while chi-square (χ²) tests were applied to categorical variables.

To assess the association between frailty and stroke, we used logistic regression models to estimate odds ratios (ORs) as the primary analysis. The frailty index (FI) was modeled both as a categorical variable (robust, pre-frail, frail) and as a continuous variable scaled by a factor of 10, such that the ORs reflected the change in stroke risk per 0.1-unit increase in the FI score9. Weighted multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted using three models. The crude model was unadjusted. Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Model 2 further adjusted for additional covariates, including education level, marital status, household income or PIR, body mass index (BMI), smoking and drinking status, depressive symptoms, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose, C-reactive protein, hemoglobin, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL, and eGFR. To assess potential non-linear associations between FI and stroke, we performed restricted cubic spline (RCS) regression using Model 2, with four knots placed at the 5th, 35th, 65th, and 90th percentiles of the FI distribution.

To test the robustness of our findings, we conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, stratified analyses were performed by subgroups of age, sex, marital status, education level, smoking status, drinking status, depressive symptoms, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes. Second, given the potential overestimation of risk when the outcome is common, we additionally performed sensitivity analyses using modified Poisson regression with robust error variance to obtain prevalence ratios (PRs). Finally, we performed a complete-case analysis restricted to participants with no missing covariate data.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.2.0). A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.

Results

Participants characteristics

In the US-based NHANES cohort, participants with stroke were significantly older (64.50 ± 0.42 years vs. 46.42 ± 0.18 years, p < 0.001), had a higher frailty index (0.30 ± 0.00 vs. 0.13 ± 0.00, p < 0.001), and were more likely to be female (56.27% vs. 51.84%, p = 0.003). The stroke group exhibited a higher prevalence of being unmarried (44.47% vs. 36.50%, p < 0.001) and lower educational attainment (41.10% high school graduates vs. 59.24% in non-stroke, p < 0.001). Clinically, the stroke group had higher BMI (29.84 ± 0.20 kg/m² vs. 28.79 ± 0.06 kg/m², p < 0.001), greater rates of diabetes (29.77% vs. 9.25%, p < 0.001), hypertension (77.50% vs. 35.53%, p < 0.001), hyperlipidemia (83.16% vs. 67.56%, p < 0.001), and depression (18.15% vs. 7.48%, p < 0.001). Biomarker analysis revealed significantly elevated fasting glucose, triglycerides, C-reactive protein, and lower hemoglobin, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and eGFR in the stroke group (all p ≤ 0.02) (Table 1).

In the China-based CHARLS cohort, participants with stroke were also older (61.56 ± 9.26 years vs. 57.53 ± 8.58 years, p < 0.001) and had a higher frailty index (0.16 ± 0.12 vs. 0.10 ± 0.08, p < 0.001). Sex distribution differences were smaller but significant (49.53% male stroke vs. 46.66% male non-stroke, p < 0.01). The stroke group had lower rates of being married (86.54% vs. 90.34%, p < 0.001) and higher rates of education below high school (75.24% vs. 66.60%, p < 0.001). Lifestyle factors differed significantly, with lower rates of current drinking (75.85% vs. 78.72%) and current smoking (57.75% vs. 61.87%) in the stroke group (p < 0.001). The stroke group had higher BMI (24.03 ± 3.94 kg/m² vs. 23.49 ± 3.85 kg/m², p < 0.001) and greater prevalence of diabetes (16.48% vs. 10.44%, p < 0.001), hypertension (53.50% vs. 32.76%, p < 0.001), hyperlipidemia (38.25% vs. 30.12%, p < 0.001), but lower prevalence of depression (48.59% vs. 64.15%, p < 0.001). Biomarkers showed higher fasting glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, C-reactive protein, and hemoglobin, alongside lower HDL cholesterol and eGFR in the stroke group (all p ≤ 0.05) (Table 1).

Association between frailty index and the risk of stroke

As shown in Table 2, higher frailty index scores were significantly associated with an increased risk of stroke in both NHANES and CHARLS populations. In the crude model, each 0.1-unit increase in the frailty index was associated with a 2.83-fold (95% CI: 2.72–2.94) higher odds of stroke in NHANES and a 1.69-fold (95% CI: 1.61–1.78) increase in CHARLS. This association remained robust in Model 1, as well as in full adjusted Model 2, with fully adjusted ORs of 2.90 (95% CI: 2.35–3.57) in NHANES and 1.78 (95% CI: 1.63–1.95) in CHARLS.

When frailty was categorized, a graded association with stroke risk was observed. Compared to robust individuals, pre-frail participants had significantly increased stroke risk in both cohorts, even after full adjustment (NHANES: OR = 3.38, 95% CI: 1.04–11.03, p = 0.04; CHARLS: OR = 2.05, 95% CI: 1.70–2.48, p < 0.001). The association was even stronger among frail individuals, with fully adjusted ORs of 11.07 (95% CI: 3.78–32.39) in NHANES and 4.63 (95% CI: 3.61–5.93) in CHARLS. These findings highlight a strong, dose-dependent relationship between frailty status and stroke risk across two independent populations. To further evaluate the robustness of our findings, we conducted two additional sensitivity analyses using both NHANES and CHARLS datasets.

First, given that odds ratios can overestimate risk when the outcome is common, we re-analyzed the association between frailty and stroke using modified Poisson regression with robust error variance to estimate prevalence ratios (PRs). The results remained consistent with those of the main analysis. For each 0.1 increase in frailty index, the adjusted PR for stroke was 2.35 (95% CI: 2.02–2.73) in NHANES and 1.64 (95% CI: 1.53–1.76) in CHARLS. Similar graded associations were observed across frailty categories, with higher stroke risk in pre-frail and frail groups compared to robust individuals in both cohorts (Supplementary Table 2).

Second, we conducted a complete-case analysis, restricted to participants with no missing data on covariates. The associations between frailty and stroke remained robust and consistent. In fully adjusted models, the odds ratios for frail vs. robust individuals were 11.07 (95% CI: 3.78–32.39) in NHANES and 4.63 (95% CI: 3.61–5.93) in CHARLS (Supplementary Table 3).

Restricted cubic spline analyses

Restricted cubic spline (RCS) models were employed to explore the nonlinear association between frailty and the predicted probability of stroke in both the NHANES and CHARLS populations.

In the NHANES cohort, a strong positive and nonlinear association was observed between frailty and stroke risk. The overall association was statistically significant (P-overall < 0.001), with evidence of nonlinearity (P-nonlinear = 0.006). The predicted stroke probability increased sharply with higher frailty index values, especially beyond a frailty index of approximately 3 (equivalent to 0.3 in the original scale). In contrast, the CHARLS cohort also demonstrated a significant overall association between frailty and stroke probability (P-overall < 0.001), but the relationship appeared linear (P-nonlinear = 0.328). The increase in predicted stroke probability was more gradual across the frailty continuum in the CHARLS population. (Fig. 2).

Restricted cubic spline model illustrating the association between frailty and predicted stroke probability in the NHANES and CHARLS population. The x-axis represents the frailty index multiplied by 10, with tick marks spaced at 1-unit intervals (corresponding to 0.1-unit increments in the original frailty index). The blue solid line shows the estimated stroke probability across the frailty spectrum, while the shaded area indicates the 95% confidence interval.

Subgroup analysis

The association between frailty and stroke risk remained consistent across all examined subgroups in both the NHANES and CHARLS cohorts (Table 3). In NHANES, frailty was significantly associated with increased stroke risk in both younger (< 65 years, OR: 2.60; 95% CI: 1.74–3.88) and older participants (≥ 65 years, OR: 3.05; 95% CI: 2.43–3.82). Similar associations were observed in CHARLS, though with lower effect sizes (OR: 1.77 and 1.44, respectively). The relationship was also evident across sexes, marital status, and education levels. Notably, in CHARLS, the association strengthened with higher educational attainment, with the highest OR observed among participants with college education or above (OR: 3.78; 95% CI: 2.26–6.86).

Across lifestyle and clinical subgroups, frailty remained a significant predictor of stroke. In NHANES, participants with dyslipidemia showed a particularly strong association (OR: 5.94; 95% CI: 2.90–12.19) compared to those without (OR: 2.76; 95% CI: 2.22–3.45). While the association persisted across smoking and drinking categories in both cohorts, a marginal association was observed among former drinkers in CHARLS (OR: 1.59; 95% CI: 0.96–2.50; p = 0.05). Overall, these findings suggest a robust and consistent link between frailty and elevated stroke risk across diverse demographic and health-related subgroups.

Discussion

This study demonstrates a significant and independent association between frailty and stroke risk across both American and Chinese populations. Utilizing two nationally representative datasets—NHANES and CHARLS—we consistently observed that higher frailty index scores, whether modeled continuously or categorically, were associated with increased stroke risk. These findings suggest that frailty, typically conceptualized as a multidimensional marker of biological aging, may serve as an important risk stratification tool in stroke prevention.

Previous research has linked frailty to cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality, but its relationship with stroke has been less extensively explored26. Notably, prior studies have often used clinical frailty measures such as the Hospital Frailty Risk Score, which may not generalize well to community settings27. Our study contributes novel insights by applying the validated Frailty Index (FI), based on the deficit accumulation model, in two general population-based cohorts. Unlike earlier work, our approach allows for both a granular and population-scalable assessment of frailty. Furthermore, our subgroup and restricted cubic spline analyses reinforce the robustness and nonlinearity of this association, highlighting that stroke risk increases even within sub-threshold levels of frailty.

Several plausible mechanisms may underlie the observed association. Frailty is associated with vascular aging, impaired cerebral autoregulation, and elevated levels of systemic inflammation, all of which are implicated in the pathogenesis of stroke28. Reduced physical activity, malnutrition, and the presence of multimorbidity among frail individuals further increase cerebrovascular vulnerability29,30,31. Additionally, chronic inflammation—a hallmark of frailty—may exacerbate endothelial dysfunction and thrombotic risk32,33. Importantly, prior interventional studies have shown that targeted resistance training, protein supplementation, and omega-3 fatty acids may not only reverse frailty to some extent but also reduce cerebrovascular event risk, suggesting shared modifiable pathways34,35,36,37,38,39.

From a public health perspective, our findings support the integration of frailty screening into stroke risk assessment frameworks, particularly in community-dwelling older adults. Given the increasing global burden of stroke and the aging population, identifying frailty as a modifiable preclinical marker offers a strategic opportunity for early intervention. The consistency of results across CHARLS and NHANES suggests that FI could be used in culturally diverse settings to support risk stratification and resource allocation. Moreover, frailty’s continuous nature provides a valuable gradient for tailoring individualized prevention strategies.

Importantly, the inclusion of CHARLS—a longitudinal, population-based cohort from China—greatly strengthens the robustness and generalizability of our findings. While NHANES provided cross-sectional evidence of the association between frailty and stroke risk, CHARLS enabled temporal sequencing by capturing incident stroke cases during follow-up. This allowed us to assess whether baseline frailty independently predicts future stroke events. The consistency of associations across both datasets, despite differing geographic, cultural, and healthcare contexts, lends further credibility to our results. Moreover, the use of CHARLS helps mitigate—but not eliminate—the possibility of reverse causation, offering initial longitudinal support for frailty as a potential precursor rather than merely a consequence of stroke.

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be considered. First, stroke diagnosis in both NHANES and CHARLS relied on self-report of physician diagnosis, which may be subject to recall bias or misclassification. Although prior validation studies have demonstrated acceptable specificity for self-reported stroke40,41, we acknowledge the possibility of measurement error. Second, the cross-sectional design of NHANES inherently limits causal inference. It is possible that stroke preceded the development of frailty in some participants, a scenario supported by prior studies reporting high frailty prevalence in stroke survivors42. Additionally, survival bias may have led to underestimation or distortion of true associations, as individuals who died soon after stroke onset—possibly those with severe frailty—would not be captured in the NHANES sample. Nevertheless, the longitudinal nature of CHARLS partially addresses these concerns by allowing assessment of incident stroke events following baseline frailty assessment. Furthermore, recent Mendelian Randomization (MR) studies provide genetic evidence suggesting a directional link from frailty to stroke, thus strengthening the biological plausibility of our findings8. Third, a substantial number of NHANES participants were excluded due to missing stroke data, primarily as a result of the survey design. While this exclusion may limit the generalizability of our findings, it was methodologically necessary, as stroke status served as the primary outcome and cannot be reliably imputed. Including participants without this essential outcome variable would have compromised the validity and integrity of the analysis. Finally, although our study incorporated two large and nationally representative cohorts from the United States and China, the generalizability of these findings to other populations remains uncertain. Further validation in ethnically and geographically diverse cohorts is warranted.

Conclusion

This study provides strong evidence that higher frailty, as measured by the frailty index, is independently associated with increased stroke risk in both U.S. and Chinese populations. Prospective studies are warranted to confirm causality and evaluate whether reducing frailty can effectively lower stroke incidence.

Data availability

Data from the NHANES are publicly available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes. Data from the CHARLS are accessible at https://charls.pku.edu.cn. Additional data underlying this article are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Feigin, V. L. et al. World stroke organization (WSO): global stroke fact sheet 2022. Int. J. Stroke. 17 (1), 18–29 (2022).

Chohan, S. A., Venkatesh, P. K. & How, C. H. Long-term complications of stroke and secondary prevention: an overview for primary care physicians. Singap. Med. J. 60 (12), 616–620 (2019).

Bettger, J. P. & Cadilhac, D. A. Stroke care costs and Cost-Effectiveness to inform health policy. Stroke 53 (6), 2078–2081 (2022).

Bangad, A., Abbasi, M. & de Havenon, A. Secondary Ischemic Stroke Prev. Neurother., 20 (3): 721–731. (2023).

Guo, Y. et al. Summary of best evidence for prevention and management of frailty. Age Ageing 53(2), afae001 (2024).

He, D. et al. Changes in frailty and incident cardiovascular disease in three prospective cohorts. Eur. Heart J. 45 (12), 1058–1068 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Mortality from all-cause and cause-specific in the elderly: joint implications of anemia and frailty. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 115, 105213 (2023).

Renedo, D. et al. Higher hospital frailty risk score is associated with increased risk of stroke: observational and genetic analyses. Stroke 54 (6), 1538–1547 (2023).

Ward, D. D. et al. Frailty, lifestyle, genetics and dementia risk. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 93 (4), 343–350 (2022).

Jayanama, K. et al. Frailty, nutrition-related parameters, and mortality across the adult age spectrum. BMC Med. 16 (1), 188 (2018).

Searle, S. D. et al. A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatr. 8, 24 (2008).

Yang, Y. et al. Association between nut consumption and frailty in the elderly: a large sample cross-sectional study. J. Hum. Nutr. Dietetics. 36 (5), 1845–1856 (2023).

Qing, L. et al. Exploring the association between frailty index and low back pain in middle-aged and older Chinese adults: a cross-sectional analysis of data from the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). BMJ Open. 14 (5), e085645 (2024).

Hoover, M. et al. Validation of an index to estimate the prevalence of frailty among community-dwelling seniors. Health Rep. 24 (9), 10–17 (2013).

Tan, M. Y. et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome on bone mineral density in men over 50 and postmenopausal women according to U.S. Survey results. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 7005 (2024).

Huo, G. et al. Association between C-reactive protein-triglyceride glucose index and stroke risk in different glycemic status: insights from the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 24 (1), 142 (2025).

Sun, Y. et al. Association between usual alcohol consumption and risk of falls in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. BMC Geriatr. 22 (1), 750 (2022).

Zhang, H. et al. Association of two novel systemic inflammatory biomarkers and frailty based on NHANES 2007–2018. Front. Public. Health. 12, 1377408 (2024).

Duggal, V. et al. National estimates of CKD prevalence and potential impact of estimating glomerular filtration rate without race. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 32 (6), 1454–1463 (2021).

Zhu, S. et al. Association of smoking and osteoarthritis in US (NHANES 1999–2018). Sci. Rep. 13 (1), 3911 (2023).

Zhou, Z. et al. Association between alcohol consumption and kidney stones in American adults: 2007–2016 NHANES. Front. Public. Health. 11, 1156097 (2023).

Park, L. T. & Zarate, C. A. Jr. Depression in the primary care setting. N Engl. J. Med. 380 (6), 559–568 (2019).

Cheng, H. G. et al. Prospective relationship of depressive symptoms, drinking, and tobacco smoking among middle-aged and elderly community-dwelling adults: results from the China health and retirement longitudinal study (CHARLS). J. Affect. Disord. 195, 136–143 (2016).

Cai, Y. et al. Interaction between trouble sleeping and depression on hypertension in the NHANES 2005–2018. BMC Public. Health. 22 (1), 481 (2022).

Mahemuti, N. et al. Association between systemic Immunity-Inflammation index and hyperlipidemia: A Population-Based study from the NHANES (2015–2020). Nutrients 15(5), 1177 (2023).

Ning, N. et al. Joint association of cardiovascular health and frailty with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: a prospective study. Age Ageing, 53(7), afae156 (2024).

Street, A. et al. The use of linked routine data to optimise calculation of the hospital frailty risk score on the basis of previous hospital admissions: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2 (3), e154–e162 (2021).

Lutski, M. et al. Impaired cerebral hemodynamics and frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. J. Gerontol. Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 73 (12), 1714–1721 (2018).

Hirase, T. et al. Impact of frailty on chronic pain, activities of daily living and physical activity in community-dwelling older adults: A cross-sectional study. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 18 (7), 1079–1084 (2018).

Li, N. et al. Geriatric syndromes, chronic inflammation, and advances in the management of frailty: A review with new insights. Biosci. Trends. 17 (4), 262–270 (2023).

Evans, N. R. et al. Frailty and cerebrovascular disease: concepts and clinical implications for stroke medicine. Int. J. Stroke. 17 (3), 251–259 (2022).

Ferrucci, L. & Fabbri, E. Inflammageing: chronic inflammation in ageing, cardiovascular disease, and frailty. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 15 (9), 505–522 (2018).

Kelly, P. J., Lemmens, R. & Tsivgoulis, G. Inflammation and stroke risk: A new target for prevention. Stroke 52 (8), 2697–2706 (2021).

Tong, T. Y. N. et al. Dietary amino acids and risk of stroke subtypes: a prospective analysis of 356,000 participants in seven European countries. Eur. J. Nutr. 63 (1), 209–220 (2024).

Prior, P. L. & Suskin, N. Exercise for stroke prevention. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 3 (2), 59–68 (2018).

Miao, Z. et al. Role of polyunsaturated fatty acids in ischemic stroke - A perspective of specialized pro-resolving mediators. Clin. Nutr. 40 (5), 2974–2987 (2021).

Tomata, Y. et al. Fatty acids and frailty: A Mendelian randomization study. Nutrients 13(10), 3539 (2021).

Cai, Y. et al. The effects of vitamin D supplementation on frailty in older adults at risk for falls. BMC Geriatr. 22 (1), 312 (2022).

Angulo, J. et al. Physical activity and exercise: strategies to manage frailty. Redox Biol. 35, 101513 (2020).

Okura, Y. et al. Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 57 (10), 1096–1103 (2004).

Engstad, T., Bonaa, K. H. & Viitanen, M. Validity of self-reported stroke: the Tromso study. Stroke 31 (7), 1602–1607 (2000).

Burton, J. K. et al. Prevalence and implications of frailty in acute stroke: systematic review & meta-analysis. Age Ageing 51(3), afac064 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study is based on data from the NHANES and CHARLS. We sincerely thank all participants and the research staff involved in these surveys for their valuable contributions.

Funding

Funding was provided by Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (Grant Nos. LGF21H170005), Project of Zhejiang Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Grant No. 2024ZL269), and the Medical Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (No. 2021KY457, 2023KY481).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.F.Z. conceptualized the study. Data curation was carried out by L.J.Y., Z.H.J., H.Y.X., W.S.W., and W.L.L. Formal analysis was conducted by X.F.Z., L.J.Y., Z.J. H.Y.X., W.S.W.,and F.L. Methodology was developed by X.F.Z. X.F.Z. wrote the original draft of the manuscript, and the review and editing were performed by X.F.Z., L.J.Y., Z.H.J., W.L.L.H.Y.X., W.S.W., and F.L. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study protocol for NHANES was reviewed and approved by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Research Ethics Review Committee, and all participants provided written informed consent. Similarly, all participants in the CHARLS survey provided informed consent, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052-11015).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Yang, L., Jin, Z. et al. Frailty index is positively associated with stroke risk in nationally representative cohorts from the united States and China. Sci Rep 15, 28440 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14116-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14116-7