Abstract

Benefiting from the tourists’ booming demand of rural tourism, rural homestay industry in Mainland China has enjoyed significant growth in recent years. While limited attention has been paid to rural homestay industry, especially on the mechanism of enhancing tourists’ intention to stay in rural homestays. Based on SOR model, this study examined the impact of physical servicescape on tourists’ intention to stay in rural homestays as well as the mediating role of perceived service quality. Using PLS-SEM on data from 341 respondents in China, findings confirmed that physical servicescape positively influenced both perceived service quality and tourists’ intention to stay in rural homestays. Additionally, perceived service quality mediated this relationship. The study provided practical insights for tourism stakeholders to enhance rural homestay appeal, fostering local economic growth and financial stability while promoting rural areas as viable tourist accommodations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since urban life is fast-paced and stressful, people have a growing desire for a more relaxed country lifestyle and are searching for a little paradise to escape to during their hectic days. As a result of the growth of rural tourism, rural homestays have gained more attention from the public1. By utilizing vacant residential spaces in rural areas to provide tourists with lodging, meals, leisure, and other relevant services2, rural homestays not only fulfill guests’ personalized accommodation needs, but also contribute to the preservation of local culture, traditional arts, and rural economies3. Driven by the growing demand for unique lodging options and authentic countryside experiences, the rural homestay industry in Mainland China has witnessed significant growth in recent years. According to the Rural Tourism Revitalization White Paper (2023) released by Trip.com Group—one of China’s largest online travel agencies—the number of rural homestay rooms listed on its platform increased from 228,751 in 2022 to 330,712 in 2023.

However, despite the rapid expansion, many rural homestays are now facing declining repurchase rates which are largely attributed to product homogenization and inconsistent service quality. Therefore, enhancing tourists’ perceived service quality and fostering positive behavioral intentions have become key priorities for homestay practitioners. As previous studies have highlighted the impact of physical servicescape on perceived service quality in restaurants4,5,6,7, and hotels8,9, as well as on consumer reuse behavior10 and revisit intentions11, it is also crucial to examine the significance and role of physical servicescape in rural homestay industry, a context that has been under-explored.

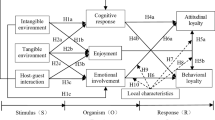

To address this gap, this study relied on the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) model which explains the process by which external stimuli (S) elicit internal evaluations (O) and ultimately influence behavioral responses (R) to achieve the following research objectives: (1) to examine the relationship between physical servicescape (S) and perceived service quality (O); (2) to investigate the effect of physical servicescape (S) on tourists’ intention to stay in rural homestay (R); (3) to investigate the effect of perceived service quality (O) on tourists’ intention to stay in rural homestay (R)and (4) to explore the mediating role of perceived service quality (O) in this relationship.

Literature review

Stimulus–organism–response (SOR) model

The Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) model originally developed by Mehrabian and Russell12 in the field of environmental psychology, has become a widely adopted theoretical model in servicescape research. It helps explain customers’ internal cognitive and emotional assessments of external stimuli and their subsequent approach or avoidance behavior13. Numerous studies have applied the SOR model to restaurant and hotel scenarios to examine how physical servicescape influences customer responses. In these studies, physical servicescape elements such as design, cleanliness, layout, and ambient conditions are conceptualized as stimuli and customer responses include customer loyalty14,15, word of mouth intention16,17 and revisiting intention18. The mediating role of organism like perceived value19,20, image perception19, customer emotion21,22 and customer satisfaction23 has also been validated.

Rural homestay

The rural homestay industry in China initially emerged in Taiwan Province in 1980 s and then appeared in in Sichuan Province in the form of “Nong Jia Le”24. Unlike standardized accommodation products, rural homestays enable tourists to experience local culture, cuisine, and activities by living with local families in rural areas25. Through the commercialization of unique local traditions, rural homestays not only provide tourists with a blend of authenticity and comfort but also contribute to rural community development and income generation26. As the core philosophy of rural homestay is treating guests as family members and creating a home-like atmosphere27, it exhibits differences in various aspects like scale and room quantity, facilities and services, and cultural ambiance, compared to many other accommodation modes28. Therefore, servicescape design and management strategies derived from hotel contexts may not be directly applicable to rural homestay industry. This underscores the need to explore how physical servicescape in rural homestays influence tourists’ internal evaluations and behavior.

Physical servicescape

Physical servicescape refers to the built surroundings consisting of rich physical cues that evoke consumers’ responses and influence their behavior intention in business environment where the transaction and service occur29. It is a multidimensional concept that can be measured both from tangible dimensions such as furniture, signage and decorations and intangible dimensions components such as temperature, noise, and odor11. While customers often see physical servicescape as a source of evaluating the service sector as a whole and it is perceived as a crucial component of the consumer’s perception30. Equipment, design, space, ambiance, and hygiene are mentioned by Hooper et al.31 as aspects of physical servicescape. Accordingly, well-designed physical servicescape materialize as elegant physical spaces with enticing interior designs, soothing lighting and audio, and distinctive scents that draw consumers into created environments that meet their requirements and expectations6.

Perceived service quality

Service quality refers to the objective performance of services and the extent to which they meet or exceed customer expectations32. Prior research has demonstrated that high service quality enhances guest satisfaction, fosters customer loyalty, and reduces advertising and operating costs32,33. In contrast, poor service quality can negatively affect business performance and damage an organization’s reputation. Perceived service quality is the comparison between the actual and expected quality of the services34,35. Given the varying research perspectives and industry contexts, scholars have developed different models to measure perceived service quality. Based on Oliver’s36 disconfirmation model, Parasuraman et al.37 proposed the SERVQUAL model, which includes five dimensions: tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy. Knutson et al.38 later adapted this model to the lodging context by developing the LODGSERV index. Meanwhile, Cronin and Taylor39 introduced the SERVPERF model, which focuses solely on performance-based measures.

Tourists’ intention to stay

Intentions refer to the extent to which an individual has developed deliberate plans for their future actions6, and behavioral intentions are seen as a predictor of actual action40. Many studies have proven that tourists’ intention to stay in hotels can be impacted by both hotel-related factors like brand personality41 and hotel attributes42,43 and tourists’ subjective factors like satisfaction44,45 and perceived value46. To rural homestay tourists, the determinants of their intention to stay also include rural destination attractiveness25.

Hypotheses development

Physical servicescape and tourists’ intention to stay

As stated above, physical servicescape refers to the perceived physical settings of accommodation and plays a significant role in determining people’s intention to stay in accommodation. Grounded in the Stimulus–Organism–Response (SOR) paradigm12,13, the physical servicescape functions as an environmental stimulus that triggers guests’ cognitive and emotional organism states, ultimately guiding their behavioral response—in this case, the intention to stay. Consumers can be greatly impacted by physical servicescape because they can create strong first impressions in their minds. An et al.11 also point out that by fostering a favorable environment, the physical surroundings in the service management sector might encourage purchases. The cleanliness of the physical environment is one of the top determinants of people’s intention to reuse a service35. For instance, in one of the study, Alhothaili et al.47 found that physical servicescape plays a crucial role in shaping service experiences, which in turn impacts the intention to revisit destinations. According to Jiang et al.3, homestay authenticity, quest and host interaction, and innovation create positive accommodation memories for homestay guests, which in turn enhance their intention to stay in the homestay. Cleanliness in rural homestays contributes significantly to guest satisfaction and therefore increases the likelihood of a repeat visit48. In a quantitative study, Zhang et al.49 found that homestay ambiance, layout, decor, signage, image, and cleanliness along with social relationship factors such as attentiveness, professionalism, host-guest interaction, and reliability are some of the important factors that affect customer satisfaction and word of mouth. Lee and Kim10 argue that attractiveness, cleanliness, layout, and comfort are major factors of physical servicescape that play a role in affecting customer behavioral intention. For example, Alhothaili47 study the impact of religious servicescape and found that religious servicescape positively influenced their revisit intention, because elements like ambience, design, and social factors within the servicescape contribute to creating a favorable experience, thus impacting the intention to revisit. Following this, we argue that if the physical servicescape of the rural homestay meets the expectations of the guests, they are more likely to stay in the rural homestay. Consistent with this SOR logic, when the stimulus (physical servicescape) aligns with guests’ expectations and evokes favorable internal evaluations, the resulting response is a stronger intention to stay. Thus, we predict that.

H1

Physical servicescape is positively related to the intention to stay in a rural homestay.

Physical servicescape and perceived service quality

Service quality is the customer’s overall appraisal of the excellence of a service encounter10. In the accommodation context, that appraisal is heavily shaped by tangible cues in the servicescape, which communicate reliability, assurance, and empathy even before any human interaction takes place. First, cleanliness functions as a baseline signal of professionalism; studies consistently show that spotless rooms and common areas elevate perceived service quality and, by extension, satisfaction10,35. Second, spatial layout and physical comfort—how furniture is arranged, how easy it is to navigate, how restful the sleeping area feels—help guests judge operational efficiency and responsiveness, thereby influencing quality judgments35. Third, décor and ambience (lighting, colour schemes, local aesthetic touches) create an emotional atmosphere that augments perceived value and fosters positive word of mouth49. When these three facets of the physical servicescape align, guests form a favourable holistic impression of service performance. Accordingly, we posit:

H2

Physical servicescape is positively related to perceived service quality.

Service quality and tourists’ intention to stay in rural homestay

High perceived service quality in the accommodation sector reliably drives repeat bookings and favourable online reviews32,35,48. Conceptually, it reflects guests’ judgements of reliability, responsiveness, assurance, empathy and tangibles10. Expectancy-disconfirmation theory (EDT) posits that when perceived performance surpasses pre-stay expectations, positive disconfirmation generates satisfaction, which then triggers approach intentions such as repurchase or extended stay36. Numerous hospitality studies confirm this cascade: Batra and Taneja50 show that an appealing servicescape lifts perceived quality and, through satisfaction, strengthens revisit plans; De Nisco51 likewise find that functional space and store appearance shape quality perceptions that ultimately guide choice of venue. In rural homestay contexts, cleanliness, ambience and décor enhance perceived value, translating into satisfaction and positive word of mouth49 and boosting repurchase likelihood Spr et al.48. Positive stay memories reinforce this pathway, as satisfied guests intend to return to the same property3. Specific quality attributes—reliability, assurance, responsiveness and empathy—also stimulate recommendation intentions52, while overall service excellence elevates both satisfaction and the desire to stay35. Guided by EDT logic and these empirical patterns, we hypothesize:

H3

Service quality is positively related to the intention to stay in a rural homestay.

Mediation role of perceived service quality between servicescape and tourists’ intention to stay in rural homestay

Following Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model, this study argues that perceived service quality mediates the relationship between physical servicescape and tourist intention to stay in rural homestay. SOR posits that stimuli influence organisms, which in turn generate responses. In the context of servicescape, the physical servicescape as a stimulus plays a crucial role in shaping the service experience of tourists (organisms)47. The servicescape, including elements like ambience, design, and social factors, can impact customers’ perceptions and behaviors, ultimately influencing their peace of mind and satisfaction. Furthermore, responsiveness from hosts in peer-to-peer accommodations is highlighted as a key element that influences guests’ perceptions of service quality and satisfaction, leading to positive reviews. Therefore, in hospitality settings, the SOR model illustrates how stimuli, such as the servicescape can shape the experiences and perceptions of individuals regarding the quality of the services, which, in turn, determine their behavioral intentions. Prior studies also elaborate that servicescape is an antecedent for service experience and service experience has a positive influence on the intention to revisit47. According to Lee and Kim10, physical servicescape enhances perceived service, which, in turn, influences loyalty and intention to reuse. Likewise, enhancing service quality in accommodation can lead to increased customer satisfaction, trust, and ultimately, a higher likelihood of repeat purchases, benefiting both tourists and the hospitality industry.

H4

Perceived service quality mediates the relationship between physical servicescape and intention to stay in rural homestay.

The conceptual model of this study is proposed, as shown in Fig. 1.

Methodology

This study was approved by the relevant ethics committee (Approval Number: EA-L1-01-GSM-2024-01-013) and conducted in accordance with all applicable guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all participants covering the voluntary nature of participation, the confidentiality of their responses, and their right to withdraw at any time. Convenience sampling was employed to recruit eligible participants who had stayed in rural homestays. Although this non-probability approach can introduce selection bias and limit generalizability, probability sampling was impractical because (i) advance guest lists were unavailable and (ii) guests’ checkout times varied unpredictably, precluding a systematic frame. “Upscale rural homestay guests” refers here to short-stay leisure tourists—non-resident travelers who book premium countryside accommodation for recreation rather than local residents. The study was conducted in nine rural homestays located in Lu’an, China. Questionnaires were placed in guest rooms, inviting tourists to complete them prior to check-out. This approach allowed respondents to reflect on their stay and evaluate the physical servicescape based on their immediate and most authentic experiences. The survey was pre-tested with 30 comparable guests to verify item clarity and scale reliability. The sample size of the study was determined using G*Power53 analysis, Fig. 2 illustrates the GPower analysis results. Using an alpha of 0.05, a power of 0.80, an effect size of 0.10, and a two-tailed test with two predictors, the minimum required sample was 132. However, to enhance generalizability, 450 questionnaires were distributed and 367 were collected, yielding a response rate of 81.55%. These 367 questionnaires were screened; 26 with suspicious responses or missing values were deleted, leaving 341 for analysis. The demographic details of the respondents are shown in Table 1.

Measurement scales

The survey questionnaires of the study were rated on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). “Physical servicescape” is treated here as the tangible, built-environment component of the broader “servicescape” construct; no overlapping items from social or ambient subdimensions were used. The 15-item scale for measuring physical servicescape was adopted from An et al.11. The sample item of the scale is “the equipment was modern looking.” Perceived service quality was measured with 21 items adopted from the work of Bhattacharya et al.54. One of the items of the scale is “Interiors are professionally designed and maintained.” Likewise, tourists’ intention to stay in rural homestays was measured with a three-item scale adapted from Tussyadiah55. One of the items of the scale is “I can see myself using rural homestay accommodation in the future.” To minimize acquiescence bias, three items (one in each construct) were reverse-coded before analysis. The questionnaire was administered in Chinese; when translation was required, a bilingual expert performed forward translation, and a second independent translator conducted back-translation to ensure conceptual equivalence.

Results and findings

The study’s model was assessed using SmartPLS (Version 4.0; https://www.smartpls.com), a software tool for partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM)56. PLS-SEM was preferred over covariance-based SEM because the data showed mild non-normality, the analysis focused on prediction rather than strict theory confirmation, and the modest sample size (n = 341) fits well within PLS efficiency guidelines. The present study model was assessed in two stages. Variance-inflation factors (VIF) for all indicators were below the commonly accepted threshold of 3.3, indicating no multicollinearity concerns. According to Hair et al.56, for an item to be reliable, the values of factor loading shall exceed 0.70. Likewise, for the internal consistency reliability of the construct, the values of Cronbach Alpha and composite reliability shall be greater than 0.7056. As shown in Table 2; Fig. 3, the values of factor loading, Cronbach Alpha, and composite reliability are greater than the required minimum thresholds.

To test the convergent validity of the data, we used an average variance extracted (AVE). The results of the study revealed that all constructions are valid, as the AVE values are higher than 0.50 (Table 2). The investigation of discriminant validity indicates that there are differences between the constructions. We used Fornell and Larcker57 criteria to measure the differences between the constructs. The results show that all values of the square root of AVE (diagonal) are greater than the inter factorial correlations (Table 3). We also used Henseler et al.58 Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) for the presence of discriminant validity, and this approach has been widely used in the literature59. The results of the HTMT are shown in Table 4 and results revealed that all HTMT values are less than the required thresholds of 0.90. Thus, the results revealed that all constructions are convergently and discriminately valid and reliable.

Hypothesis testing and structural equation modeling

A structural equation model was created using SmartPLS to test the hypotheses. As shown in Table 5; Fig. 4, the effect of physical servicescape on intention to stay in rural homes is positive and significant (β = 0.140, t-value = 2.783, p-value = 0.006), thus, H1 is supported. The effect of physical servicescape on perceived service quality is positive and significant (β = 0.354, t-value = 7.337, p-value = 0.000), supporting H2. The results also supported H3, which showed a positive and significant relationship between perceived service quality and intention to stay at a rural home (β = 0.626, t-value = 15.132, p-value = 0.000). Finally, the results of the study provided support for the mediating role of perceived service quality in the relationship between physical servicescape and intention to stay in rural homes (β = 0.222, t-value = 5.936, p-value = 0.000).

Discussion and conclusions

This study investigated the predictors of tourist intention to stay at rural homestays in China and the mediating role of perceived service quality on the relationship between physical servicescape and intention to stay in rural homestay. The findings reinforce SOR logic by showing that the stimulus (servicescape) acts through the organism (service-quality appraisal) to trigger the response (stay intention), and they dovetail with Expectation-Confirmation Theory36, in which positive disconfirmation of service expectations translates into approach behavior The findings reinforce SOR logic by showing that the stimulus (servicescape) acts through the organism (service‐quality appraisal) to trigger the response (stay intention), and they dovetail with Expectation-Confirmation Theory36, in which positive disconfirmation of service expectations translates into approach behavior. Through a PLS-SEM approach, physical servicescape was found to be a significant predictor of intentions to stay in a rural homestay. This suggests that tourists are more likely to stay once they perceive that physical servicescape, that is the souring environment is to meets their expectation. For instance, when they perceive that the ambience, the layout, the hygiene, and the quality of the service offered by the homestay are good, they are more likely to stay. This finding coincided with a study conducted by Lee & Kim10 in terms of reusing public service. The study outcome also is in line with the work of Alotaibi et al. and Lee & Kim10,47 that the physical servicescape attributes such as cleanliness and layout affect customer loyalty and satisfaction, which in turn affect their intention to use service. In addition, the findings revealed that physical servicescape is also a strong predictor of perceived quality. This finding suggests that tourist perceptions of service will change with the physical servicescape. For instance, if the physical servicescape such as the physical and social surroundings is appealing, tourists are more likely to have a positive perception of the services provided by rural homestay owners. This outcome corroborates the work of Hooper et al. and Lee & Kim10,31 who found that cleanliness, easy layout, and comfort are key factors that directly impact service quality perception and satisfaction in public service facilities. Viewed through the SERVQUAL lens37, cleanliness and layout act chiefly on the ‘tangibles’ and ‘reliability’ dimensions, explaining why they dominate tourists’ quality judgements.

In addition, perceived service quality was also proved as an antecedent leading to the tourist intention to stay at rural homestays. The strength of this link aligns with Bhattacharya et al.’s54 Himalayan study but exceeds the medium effect reported by Hooper et al.31, highlighting a context-sensitive quality threshold in Chinese rural hospitality. It implies that Chinese consumers will intend to stay at rural homestays as an accommodation if they believe that the perceived services are of high quality. This finding is in line with the work of Spr et al.48 who found that service quality positively affects customers’ selection of accommodation and their purchasing decisions. Likewise, our study findings also concur with the work of Wong and Chan32 who found that service quality attributes such as property/accommodation, hosts, local culture, location, customer expectations, emotions, and past experiences are the key drivers of customer accommodation selection. Similarly, Hooper et al.31 found that physical servicescape is an antecedent of perceived service quality, which in turn shapes customer behavior intention. The work of Untachai60 also substantiated our study findings that perceived service quality is a mediating mechanism in the relationship between physical servicescape and word of mouth. Localized factors—such as Lu’an’s emphasis on angertainment, collectivist guest–host norms, and variable infrastructure—may amplify the salience of service warmth and dampen the influence of pure aesthetics, limiting generalizability to other rural regions. Taken together, the results extend servicescape and SERVQUAL theories by demonstrating that, in upscale rural Chinese homestays, physical cues matter chiefly through the prism of perceived service quality.

Theoretical and practical implications

Theoretically, this study brings about a comprehensive understanding of physical servicescape, perceived service quality, and intention to stay in rural homestays in the context of the Chinese tourism industry. More precisely, the findings speak directly to Bitner’s29 physical-servicescape theory and to SERVQUAL’s ‘tangibles’ dimension, confirming that ambience, hygiene, space, and décor work in concert to form guests’ quality appraisals. From a theoretical perspective, this study contributed to the integration of SOR and perceived service quality as mediating variables in the relationship between physical servicescape and intention to stay in rural homes, which, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, has not been investigated. Because upscale rural homestays combine modern amenities with vernacular architecture, they create a hybrid servicescape that tests these theories in a novel socio-cultural niche. The data reveals that hygiene and spatial layout jointly underpin perceived reliability, whereas décor and ambience elevate emotional resonance, suggesting a two-tier structure that extant models have not fully recognized. This integration reinforces the SOR cascade while also dovetailing with Expectation-Confirmation logic: favorable disconfirmation under high-quality physical cues translates into stronger approach intentions. The data analysis through PLS-SEM revealed that all relationships were statistically significant. Consequently, the study extends servicescape theory into China’s upscale rural segment—a setting scarcely examined—thus sharpening its boundary conditions.

Practically, this research provides tourism service providers with practical guidelines for considering the rural homestay as an alternate form of accommodation for tourists from all over the world. In that, the tourism industrialist can refer to the findings of the study, by enhancing the attributes of the physical servicescape to enhance the inflow of tourists in rural homestay. The study finding suggests that investing in the ambiance, cleanliness, and layout of rural homestays can enhance the overall satisfaction of the customer and as a result, their intention to stay in rural homes. The mediating role of perceived service quality in the relationship between physical servicescape and tourist intention to stay in rural home implies that tourist organization and government should not only enhance the physical surroundings but also focus on intangible aspects of the rural homestay such as providing quality food, a nice and clean environment, high-quality services, tourist interaction with the local community, and high social interaction with tourists. In doing so, the tourist organizer will not only enhance the experience and satisfaction of the tourists but also enhance their probability of living in the rural homestay. The study also provides guidelines for the rural homestay owners that provide favorable physical servicescape and ensure that high service quality services will provide them with a competitive advantage in the tourism industry.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy concerns but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Xing, B., Li, S. & Xie, D. The effect of fine service on customer loyalty in rural homestays: the mediating role of customer emotion. Front. Psychol. 13, 964522 (2022).

Fei, L. et al. The evaluation system and application of the homestay agglomeration location selection. J. Resour. Ecol. 10 (3), 324–334 (2019).

Jiang, G. X. et al. How to impress guests: key factors and strategy configurations for the accommodation memories of homestay guests. J. Hospitality Tourism Manage. 50, 267–276 (2022).

Reimer, A. & Kuehn, R. The impact of servicescape on quality perception. Eur. J. Mark. 39 (7/8), 785–808 (2005).

Kim, W. G. & Moon, Y. J. Customers’ cognitive, emotional, and actionable response to the servicescape: A test of the moderating effect of the restaurant type. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 28 (1), 144–156 (2009).

Chang, J. C. The impact of servicescape on quality perception and customers’ behavioral intentions. Adv. Manage. Appl. Econ. 6 (4), 67 (2016).

Agnihotri, D. & Chaturvedi, P. A study on impact of servicescape dimensions on perceived quality of customer with special reference to restaurant services in Kanpur. Int. J. Manage. Stud. 3 (7), 115–124 (2018).

Kim, Y. A study of understanding the impact of physical environment on perceived service quality in the hotel industry (2007).

Kirillova, K. & Chan, J. What is beautiful we book: hotel visual appeal and expected service quality. Int. J. Contemp. Hospitality Manage. 30 (3), 1788–1807 (2018).

Lee, S. Y. & Kim, J. H. Effects of servicescape on perceived service quality, satisfaction and behavioral outcomes in public service facilities. J. Asian Archit. Building Eng. 13 (1), 125–131 (2014).

An, S., Lee, P. & Shin, C. H. Effects of servicescapes on interaction quality, service quality, and behavioral intention in a healthcare setting. Healthcare 11(18) (2023).

Mehrabian, A. & Russell, J. A. An approach to environmental psychology (1974).

Donovan, R. J. & Rossiter, J. R. Store atmosphere: an environmental psychology approach. J. Retail. 58 (1), 34–57 (1982).

ÇEtİNsÖZ, B. C. Influence of physical environment on customer satisfaction and loyalty in upscale restaurants. J. Tourism Gastronomy Stud. 7 (2), 700–716 (2019).

Idrus, N. L. & Yendra, Y. The link between physical evidence, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty: an empirical analysis. Adv. Bus. Industrial Mark. Res. 3 (1), 1–15 (2025).

To, W. M. & Leung, V. W. The effects of diningscape on customer satisfaction and word of mouth. Br. Food J. 125 (9), 3334–3350 (2023).

Chao, R. F., Fu, Y. & Liang, C. H. Influence of servicescape stimuli on word-of-mouth intentions: an integrated model to Indigenous restaurants. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 96, 102978 (2021).

Meng, B. & Choi, K. An investigation on customer revisit intention to theme restaurants: the role of servicescape and authentic perception. Int. J. Contemp. Hospitality Manage. 30 (3), 1646–1662 (2018).

Durna, U., Dedeoglu, B. B. & Balikçioglu, S. The role of servicescape and image perceptions of customers on behavioral intentions in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hospitality Manage. 27 (7), 1728–1748 (2015).

Dedeoğlu, B. B. et al. The impact of servicescape on hedonic value and behavioral intentions: the importance of previous experience. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 72, 10–20 (2018).

Ali, M. A. et al. Physical and social servicescape: impact on customer affection and behavior at full-service restaurants. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 1–28 (2024).

Ellen, T. & Zhang, R. Measuring the effect of company restaurant servicescape on patrons’ emotional States and behavioral intentions. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 17 (2), 85–102 (2014).

Asghar Ali, M. et al. Influence of servicescape on behavioural intentions through mediation and moderation effects: a study on malaysia’s full-service restaurants. Cogent Bus. Manag. 8 (1) (2021).

Wu, L. & Tao, Y. The development of Taiwan B&B industry and its enlightenment on countryside tourism of Mainland. J. Jiangsu Normal Univ. (Philosophy Social Sci. Edition). 42 (2), 154–158 (2016).

Dey, B., Mathew, J. & Chee-Hua, C. Influence of destination attractiveness factors and travel motivations on rural homestay choice: the moderating role of need for uniqueness. Int. J. Cult. Tourism Hospitality Res. 14 (4), 639–666 (2020).

Bachok, S., Hasbullah, H., Ab, S. A. & Rahman Homestay operation under the purview of the ministry of tourism and culture of malaysia: the case of Kelantan homestay operators. Plann. Malaysia 16 (2018).

Yasami, M., Awang, K. W. B. & Teoh, K. Homestay tourism: from the distant past up to present. PEOPLE: Int. J. Social Sci. 3 (2), 1251–1268 (2017).

Lynch, J. G. Theory and external validity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 27 (3), 367–376 (1999).

Bitner, M. J. Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J. Mark. 56 (2), 57–71 (1992).

Guo, Z., Yao, Y. & Chang, Y. C. Research on customer behavioral intention of hot spring resorts based on SOR model: the multiple mediation effects of service climate and employee engagement. Sustainability 14 (14), 8869 (2022).

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J. & Mullen, M. R. The servicescape as an antecedent to service quality and behavioral intentions. J. Serv. Mark. 27 (4), 271–280 (2013).

Wong, T. S. & Chan, J. K. L. Experience attributes and service quality dimensions of peer-to-peer accommodation in Malaysia. Heliyon 9(7) (2023).

Bowen, J. T. & Chen, S. The relationship between customer loyalty and customer satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hospitality Manage. 13 (5), 213–217 (2001).

Kadiresan, V. et al. Perceived HR practices and intention to quit of generation X and Y in unionize organization. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 7 (4.15), 505–509 (2018).

Tian, Y. et al. Moderating role of perceived trust and perceived service quality on consumers’ use behavior of Alipay e-wallet system: the perspectives of technology acceptance model and theory of planned behavior. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. (2023).

Oliver, R. L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 17 (4), 460–469 (1980).

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A. & Berry, L. L. Servqual: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer perc. J. Retail. 64 (1), 12 (1988).

Knutson, B. et al. LODGSERV: A service quality index for the lodging industry. Hospitality Res. J. 14 (2), 277–284 (1990).

Cronin, J. J. Jr & Taylor, S. A. Measuring service quality: a reexamination and extension. J. Mark. 56 (3), 55–68 (1992).

Kakar, A. S. et al. Person-organization fit and turnover intention: the mediating role of need-supply fit and demand-ability fit. Glob. Bus. Organ. Excell. (2023).

Tsaur, S. H., Hsu, F. S. & Ching, H. W. The impacts of brand personality and self-congruity on consumers’ intention to stay in a hotel: does consumer affinity matter? J. Hospitality Tourism Insights. 6 (1), 246–262 (2023).

Mohd Noor, N. A., Hasan, H. & Kumar, D. Exploring tourists intention to stay at green hotel: the influences of environmental attitudes and hotel attributes. Macrotheme Rev. 3 (7), 22–33 (2014).

Ahmad, N. F., Hemdi, M. A. & Othman, D. N. Boutique hotel attributes and guest behavioral intentions. J. Tourism Hospitality Culin. Arts. 9 (2), 257–266 (2017).

Wang, K. Y., Ma, M. L. & Yu, J. Understanding the perceived satisfaction and revisiting intentions of lodgers in a restricted service scenario: evidence from the hotel industry in quarantine. Service Bus. 15 (2), 335–368 (2021).

Raza, M. A. et al. Relationship between service quality, perceived value, satisfaction and revisit intention in hotel industry. Interdisciplinary J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 4 (8), 788–805 (2012).

Chaulagain, S. et al. Understanding the determinants of intention to stay at medical hotels: A customer value perspective. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 112, 103464 (2023).

Alhothali, G. T., Elgammal, I. & Mavondo, F. T. Religious servicescape and intention to revisit: potential mediators and moderators. Asia Pac. J. Tourism Res. 26 (3), 308–328 (2021).

Spr, C. R. et al. Factors affecting domestic tourists’ repeat purchase intention towards accommodation in Malaysia. Front. Psychol. 13, 1056098 (2023).

Zhang, T. et al. Examining a perceived value model of servicescape for bed-and-Breakfasts. J. Qual. Assur. Hospitality Tourism. 24 (4), 359–379 (2023).

Batra, M. & Taneja, U. Examining the effect of servicescape, perceived service quality and emotional satisfaction on hospital image. Int. J. Pharm. Healthc. Mark. 15 (4), 617–632 (2021).

De Nisco, A. & Warnaby, G. Shopping in downtown: the effect of urban environment on service quality perception and behavioural intentions. Int. J. Retail Distribution Manage. 41 (9), 654–670 (2013).

Jang, D. H. The effect of service quality of rural stay on customer satisfaction and recommendation intention. J. Korean Soc. Rural Plann. 24 (1), 89–97 (2018).

Faul, F. et al. G* power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods. 39 (2), 175–191 (2007).

Bhattacharya, P. et al. Perception-satisfaction based quality assessment of tourism and hospitality services in the Himalayan region: an application of AHP-SERVQUAL approach on Sandakphu trail, West bengal, India. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks. 11 (2), 259–275 (2023).

Tussyadiah, I. P. Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. Int. J. Hospitality Manage. 55, 70–80 (2016).

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19 (2), 139–152 (2011).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18 (1), 39 (1981).

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M. & Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43 (1), 115–135 (2014).

Kakar, A. S. & Khan, M. Exploring the impact of green HRM practices on pro-environmental behavior via interplay of organization citizenship behavior. Green. Finance. 4 (3), 274–294 (2022).

Untachai, S. Service quality: mediating role in servicesape and word-of-mouth. Kasetsart J. Social Sci. 40 (2), 395–401 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y. conceived and designed the research, performed the initial data analysis, and drafted the first version of the manuscript. L.W. contributed to data collection, formal analysis, and manuscript revision. J.Y. provided conceptual direction, secured funding, and further refined the methodology. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Y., Wang, L. & Yan, J. Perceived service quality mediates the effect of physical servicescape on tourists’ intention to stay in rural homestays. Sci Rep 15, 29506 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14695-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14695-5