Abstract

Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion (MI/R) injury frequently occurs during the clinical management of ischemic heart disease. The underlying mechanism includes neutrophil infiltration, heightened intracellular Ca2+ levels, mitochondrial energy metabolism disorder. This study investigated the pathological role of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor/mitochondrial calcium uniporter (ITPR1/MCU) pathway in regulating disturbances in intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) and mitochondrial calcium ([Ca2+]m) levels during MI/R injury. Furthermore, the study explored the potential of 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane (2-APB) as a cardioprotective agent against MI/R injury. The outcomes of this investigation demonstrated that the ITPR1/MCU pathway was activated after MI/R, leading to [Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m overload, impairing mitochondrial structure and function, and promoting cardiomyocyte death. The administered treatment attenuates myocardial injury after MI/R by reversing the [Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m imbalance, maintaining cardiomyocyte mitochondrial homeostasis and promoting cardiomyocyte survival. Furthermore, the administration of 2-APB exerted a suppressive effect on MCU expression. Notably, the activation of MCU abolished the cardioprotective impact mediated by 2-APB. These results suggest that 2-APB intervenes [Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m balance and maintains mitochondrial function through the ITPR1/MCU pathway. The strategic manipulation of this pathway holds promise as a prospective avenue for the clinical treatment of MI/R injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ischemic cardiac disease has emerged as a severe threat to human well-being and life1. In the realm of therapeutic interventions for acute ischemic heart disease, the most immediate and efficacious strategy, without a doubt, is to swiftly re-establish blood perfusion to ischemic myocardial tissue, thereby maximizing the preservation of cardiomyocytes and mitigating further necrosis and apoptotic processes2. Nonetheless, both clinical investigations and animal trials have revealed that upon the restoration of blood perfusion, the heart’s function and structure do not recuperate; instead, a more severe form of damage ensues. This phenomenon is recognized as MI/R injury3,4. Effectively restoring blood flow to ischemic tissue with minimal concomitant risk of MI/R injury constitutes the pivotal juncture in the therapeutic paradigm for ischemic heart diseases. However, due to numerous pathogenic factors and complicated processes, the pathogenesis of MI/R injury has not been fully elucidated, and there is no effective treatment plan. Therefore, a clear understanding of its pathogenesis becomes the first prerequisite.

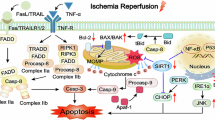

MI/R injury encompasses a multitude of intricate layers, with pivotal mechanisms such as neutrophil infiltration, oxidative stress, inflammatory responses, intracellular calcium ion (Ca2+) overload, and mitochondrial energy metabolic disruptions all playing substantial roles5. Notably, aberrant calcium ion transport mechanisms emerge prominently as one of the essential factors that precipitate MI/R injury6. During the process of MI/R, the delicate intracellular calcium ion balance is disrupted, leading to a rapid increase in [Ca2+]m and resulting in a state of overload. This abnormal accumulation of [Ca2+]m, due to its interaction with mitochondrial phosphate groups, severely impairs the oxidative phosphorylation process, effectively halts the normal synthesis of ATP, and ultimately results in cardiomyocyte necrosis7,8.

Regulating the equilibrium between [Ca2+]i and [Ca2+]m, thereby upholding the functional and structural integrity of mitochondria, engenders a safeguarding influence on MI/R injury9,10,11,12. In cardiomyocytes, intracellular Ca2+ signaling is mainly regulated by ITPR1 and MCU13,14. The enhanced expression of ITPR1 has been identified as a causal factor contributing to decreased viability of cardiomyocytes and subsequent myocardial dysfunction caused by MI/R injury15,16. However, its mechanism is still unclear.

-

2‑APB is a membrane‑permeable small molecule that functions as an antagonist of IP₃ receptors—including ITPR1—with an IC₅₀ around 42 µM, and inhibits store-operated Ca²⁺ entry (SOCE) and various TRP channels (e.g., TRPC/TRPM) at concentrations ≥ 30–50 µM. Beyond channel modulation17 2‑APB also possesses potent antioxidant activity: its unique two-benzene-ring boron structure reacts with extracellular H₂O₂ to form phenolic compounds, thereby directly scavenging ROS18. In vitro studies using cardiomyocytes have shown that pretreatment with 2‑APB protects against H₂O₂-induced Ca²⁺ overload and cell death18,19. In vivo, administration of 2‑APB immediately before reperfusion in murine I/R models markedly reduced myocardial infarct size, oxidative stress, and neutrophil infiltration.

Given that reperfusion is the critical window in MI/R pathogenesis, where mitochondrial Ca²⁺ overload and ROS production peak, administering 2‑APB just before reperfusion places its protective effects optimally. By simultaneously buffering ITPR1-triggered Ca²⁺ dysregulation and neutralizing ROS, 2‑APB acts to preserve mitochondrial integrity, inhibit permeability transition pore opening, and prevent cardiomyocyte death during this vulnerable phase.

This study investigated the pathological roles of [Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m disturbance and ITPR1/MCU pathway in MI/R injury. Furthermore, this study conducted an evaluation aimed at observing and validating the efficacy and safety of the ITPR1 antagonist 2-APB as a potential cardioprotective agent in the treatment of MI/R injury. It is hoped that this research will provide new insights and inspiration for the treatment of ischemic heart disease, and contribute to the continuous advancement in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

Materials and methods

Mouse studies

SPF-grade male C57BL/6 mice weighing 25–30 g were procured from SPF (Beijing) Biotechnology Co.,Ltd. These mice, aged 6–8 weeks, were housed as per conventional animal facility protocols and provided unrestricted availability of food and water. The mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of Avertin (Nanjing Aibei Bio, 2103 A, 200 µl/10 g). They were then connected to a small animal ventilator, their chests were opened to expose the heart, and the left anterior descending coronary artery was ligated 30 min and subsequently reperfused to establish a MI/R model. Mice in the sham-operated group were used as surgical controls, only threaded without ligation, and the rest of the operations were the same as those in the MI/R group. Additionally, 2-APB (TCI, D0281, 10 mg/kg) and spermine (Solarbio, S8310, 5 mg/kg) were intraperitoneally injected 30 min before MI/R20,21. The mice were euthanized 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h after reperfusion, whereupon both blood and cardiac tissue specimens were procured for subsequent analysis. The Animal Care Welfare Committee of Guizhou Medical University approved the experiment. All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Echocardiographic measurements in vivo

Echocardiographic assessments were conducted at distinct intervals post-reperfusion. The transthoracic echocardiography function test was performed by the V6VET small animal ultrasound imaging system (Viinuo Technology). Mice were anesthetized with Avertin (200 µl/10 g), fixed in a supine position, and echocardiographic parameters were recorded, including left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), left ventricular fractional shortening, etc.

In vitro cardiomyocyte culture

Primary cardiomyocytes were isolated from mice using trypsin and type II collagenase. Mouse heart tissue was digested with a mixed digestion solution containing 0.03% type II collagenase and 0.1% trypsin. The supernatant was collected in minimum essential medium (MEM) containing 25% fetal bovine serum (FBS) to inactivate enzymes and protect cell viability, centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min, and the cell pellet was resuspended. Subsequently, the cardiomyocytes were maintained in MEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) procedures were modified from a previous study22. The cardiomyocytes were cultured in an anoxic incubator (5% CO2 / 95% N2) for 6 h. Subsequently, the cells were transferred into a standard incubator (95% O2 / 5% CO2) and maintained in MEM supplemented with 10% FBS for 12 h in an incubator to mimic reperfusion. 2-APB (50 µM) and spermine (2 µM) were administrated 30 min before reoxygenation during the H/R of the mice primary cardiomyocyte model18,23.

Western blotting

Heart tissue or cardiomyocytes were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer containing protein phosphatase inhibitors and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride. The lysates (30 µg/sample) were loaded equally and separated by 12.5% Omni-EasyTM one-step PAGE gel, transferred to polyvinyl difluoride membrane, and blocked with 5% skimmed milk for 1–2 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with the primary antibody at 4 °C for 12–18 h. β-actin was used as an internal control for proteins. After washing three times, they were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, imaging was carried out with super sensitive ECL luminescence reagent and chemiluminescence imaging system. The gray value of protein bands was calculated by Image J software. Antibody applications in this study are as follows: GAPDH (Proteintech, 60004-1-lg, 1:300000), β-ACTIN (Proteintech, 66009-1-lg, 1:100000), ITPR1 (Proteintech, 19962-1-AP, 1:200), IL-6 (Abcam, ab290735, 1:1000), TNF-α (Proteintech, 60291-1-Ig, 1:1000), IL-1β (Abcam, ab234437, 1:1000), OXPHOS (Abcam, ab110413, 1:1000), DRP1 (Proteintech, 68021-1-Ig, 1:5000), p-DRP1 (Cell Signaling, 4494, 1:1000), MFF (Proteintech, 66527-1-Ig, 1: 2000), FIS1 (Proteintech, 66635-1-Ig, 1:2000), MCU (Proteintech, 26312-1-AP, 1:2000), NCX (Abcam, ab177952, 1:1000).

Calciumion double staining

Cardiomyocytes were seeded in six-well plates and underwent a preliminary incubation period of 12 h. The preparation of the Fluo-4/AM (Yeasen, 40704ES50) and Rhod-2/AM (Yeasen, 40776ES50) working solutions was carried out following the provided instructions. Subsequently, the pre-cultured cells were extracted, and the growth medium was replaced. Thorough rinsing of the cells using HBSS solution was performed 3 consecutive times. The cardiomyocytes were then exposed to an incubation process employing the Rhod-2/AM working solution, maintaining a temperature of 37 °C for 30 min. The working solution was then removed, and the cells were washed three times with HBSS solution. Next, a quantity of 2 ml of HBSS solution was added, and the cells were subjected to an incubation period of 20 min at 37 °C. Following this, the cardiomyocytes underwent incubation employing the Fluo-4/AM working solution under conditions mirroring the earlier temperature and duration parameters. After the incubation, the working solution was removed, and the cells were subjected to three cycles of HBSS solution washing. The final stage of this process entailed the addition of 2 ml of HBSS solution, followed by an additional 20 min incubation at 37 °C. The cells were examined using a fluorescence microscope (Shanghai Yuehe). The subsequent analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity was performed utilizing ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence

Cardiomyocytes were introduced into six-well plates and allowed to cultivate within a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for a span of 12 h. Following aspirating and discarding the culture medium, the cells were subjected to rinsing with PBST (1xPBS containing 0.1% Tween-20) thrice. Subsequently, fixation of the cardiomyocytes was accomplished through the application of 4% paraformaldehyde for a duration of 15 min. For permeabilization, 0.5% Triton X-100 was employed for 20 min. Following this, blocking was executed with a solution comprising blocking reagents (PBST containing 1% BSA and 22.52 mg/ml glycine) at room temperature, allowing for an h of blocking. Subsequent to the blocking step, cardiomyocytes were subjected to an overnight incubation at 4 °C with the primary antibody TOM20 (Proteintech, 66777-1-lg, 1:200). Following three washes with PBS, the cells were subjected to incubation with a secondary antibody for a period of 1 h at room temperature, all in the absence of light. Subsequent to this incubation, the cells underwent another three washes with PBS, still in the absence of light. DAPI staining was carried out for 3 min to label the nuclei. The expression of the target protein was then observed using a fluorescence microscope once the anti-fluorescent quencher was added dropwise. The images were captured utilizing ImageView software.

Mitochondrial membrane potential observation

In alignment with established protocols, the culture medium was extracted from the cardiomyocytes inoculated in the six-well plate. Following this, a composite mixture of 1 ml of cell culture medium and 1 ml of JC-1 (Beyotime, C2006) staining working solution were added, ensuring thorough mixing. This mixture was subsequently incubated in the cell culture incubator, maintaining a temperature of 37 °C. The incubation procedure, conducted in the darkness, lasted for a duration of 20 min. After the incubation, the supernatant was aspirated, and two washes were performed using JC-1 staining buffer (1X). Subsequently, 2 ml of cell culture medium was introduced. The mitochondrial membrane potential was then evaluated under a fluorescence microscope, and the images were captured using ImageView software.

Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) staining

Mouse hearts were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. Post-fixation, a dehydration procedure was undertaken, followed by embedding the specimens within paraffin. Subsequently, these embedded tissues were sectioned into segments measuring 3–5 μm in thickness. The use of fluorescein-conjugated wheat germ agglutinin staining facilitated the visualization of the cross-sectional area of the left ventricular cardiomyocytes. The quantification of individual cardiomyocyte cross-sectional areas was facilitated through the application of ImageJ software, which enabled precise measurements and analysis of the observed samples.

Statistical analysis

The data underwent statistical analysis using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (GraphPad Prism software, Inc.) Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Values were analyzed using t-test, two-way analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). A significance threshold was established at P < 0.05, indicating statistically significant differences between groups.

Results

2-APB attenuates myocardial injury after MI/R.

Initially, myocardial tissue samples were collected from mice at various time points subsequent to MI/R specifically at 0 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. Subsequent to extraction, the protein expression levels of ITPR1 were evaluated. Notably, a consistent and elevated expression of ITPR1 was observed commencing from the 24 h mark following MI/R (p < 0.01, Fig. 1A and B). Subsequently, cardiac function was evaluated after cardiac surgery through echocardiography. In the MI/R group, the mice exhibited a decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) at 24 h and 72 h following MI/R. However, treatment with 2-APB, an ITPR1 antagonist, enhanced LVEF, thereby ameliorating the observed decline (p < 0.05, p < 0.01, Fig. 1C and G). Specifically, echocardiography revealed improvements in both ejection fraction (EF%) and fractional shortening (FS%) after 2-APB treatment (Fig. 1D–E), suggesting better systolic function. Moreover, 2-APB attenuated the MI/R-induced increases in left ventricular internal diameters during diastole and systole (LVDd and LVDs), indicating alleviation of adverse ventricular remodeling (Fig. 1F–G). Subsequently, the cross-sectional area of cardiomyocytes was observed using WGA staining. Notably, the utilization of 2-APB reduced myocardial swelling following MI/R (p < 0.01, Fig. 1H and I). Quantification of the WGA-stained area showed that 2-APB significantly reduced cellular hypertrophy compared with the vehicle group at both 24 h and 72 h. Moreover, 2-APB maintained mitochondrial structure, evident from the observed transformation from larger to smaller or absent cristae (Fig. 1J). Electron microscopy further confirmed that mitochondria in the 2-APB group retained more intact cristae and structural integrity, in contrast to the severely swollen and disorganized mitochondria observed in the MI/R group. These outcomes collectively indicate the protective effect of 2-APB on cardiac function, as well as its capacity to mitigate myocardial injury in the context of MI/R.

2-APB can improve myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. (A-B). Western-blot analysis of ITPR1 protein level in myocardial tissue after myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in mice. (C-G). Representative echocardiogram and ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), end-diastolic left ventricular diameter (LVIDd) and end-systolic left ventricular diameter (LVIDs) at 24 and 72 h after reperfusion. (H–I). WGA staining of myocardial tissue, scale bar = 20 μm. J. Myocardial ultrastructure under electron microscopy, scale bar = 2 μm. Experiments were repeated 3–4 times. Data represent mean ± SD. *p < 0. 05, **p < 0. 01, ***p < 0. 001.

2-APB attenuates myocardial inflammation and maintains myocardial cell viability after MI/R

Myocardial inflammation is related to myocardial cell apoptosis and impaired cardiac function24. The expression of pro-inflammatory factors in mice after MI/R was analyzed. In comparison to the sham operation group, the expression of pro-inflammatory factor IL-1β showed an increase at 24 h after MI/R and a significant rise at 72 h after MI/R (p < 0.05, p < 0.001, Fig. 2A, D and F). Pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNFα and IL-6 exhibit a wide range of biological activities, aiding in coordinating the body’s response to infection and fostering inflammation development25. Protein analysis involved the extraction of myocardial tissues from mice subjected to myocardial ischemia and reperfusion for 24 h and 72 h. The results demonstrated elevated protein levels of TNFα and IL-6 in the MI/R group. Remarkably, 2-APB treatment reduced pro-inflammatory protein levels (p < 0.01, Fig. 2A and C).

2-APB improves myocardial inflammation after myocardial ischemia-reperfusion. (A–F). Western-blot analysis of inflammatory proteins in myocardial tissue after myocardial ischemia-reperfusion in mice. (G–H). PI staining of cardiomyocytes after H/R, scale bar = 200 μm. The experiment was repeated three times. Data represent mean ± SD. *p < 0. 05, **p < 0. 01, ***p < 0. 001.

Utilizing in vitro PI staining, it was found that the number of PI-positive cardiomyocytes after H/R was higher than that of the sham operation group, and the number of PI-positive cardiomyocytes was significantly reduced after 2-APB treatment (p < 0.001,Fig. 2G and H). It indicated that cardiomyocytes died after H/R, and 2-APB was beneficial to the survival of cardiomyocytes. Therefore, the findings suggest that 2-APB attenuates myocardial inflammation and promotes cardiomyocyte survival after MI/R, which may explain its cardioprotective effect during MI/R.

2-APB protects mitochondrial homeostasis in cardiomyocytes after H/R

Mitochondria, recognized as the energy centers of cardiomyocytes, are crucial organelles. Investigations have substantiated that the process of MI/R engenders detrimental impacts on the mitochondrial respiratory chain26. Consequently, this disruption incites the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) within mitochondria, consequently setting off a cascade of events encompassing myocardial inflammation and resultant myocardial impairment27. Pertinently, the investigations have unveiled a decline in the levels of electron respiratory complex protein (p < 0.05–0.01, Fig. 3A and F) and mitochondrial membrane potential (assessed by JC-1 assay) (p < 0.001, Fig. 3G and H) subsequent to H/R stress in cardiomyocytes. However, it is important to note that the incorporation of 2-APB exhibited a remarkable capability to revert this decline in treated cardiomyocytes.

2-APB maintains mitochondrial function in cardiomyocytes after hypoxia/reoxygenation. (A–F). Protein levels of electron respiratory complexes after H/R in cardiomyocytes. (G–H). Mitochondrial membrane potential changes after H/R detected by JC-1 probe, scale bar = 100 μm. (I). Observation of mitochondrial structure by immunofluorescence, scale bar = 25 μm; enlarged scale bar = 10 μm. (J–M). Western-blot analysis of protein levels of mitochondrial fission proteins after H/R. The experiment was repeated three times. Data represent mean ± SD. *p < 0. 05, **p < 0. 01, ***p < 0. 001.

Mitochondrial structural disruption during MI/R generates excess ROS and accelerates cell death28. Mitochondrial TOM20 immunofluorescence revealed that H/R induced mitochondrial cleavage from elongated networks into small spheres or rods, and 2-APB treatment prevented mitochondrial fission (Fig. 3I). Mitochondrial fission is primarily regulated by the cytosolic GTPase dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), which translocates to the outer mitochondrial membrane and interacts with adaptor proteins such as mitochondrial fission factor (Mff) and fission protein 1 (Fis1). This recruitment facilitates mitochondrial constriction and division, processes that are often activated under cellular stress conditions including oxidative stress and ischemia-reperfusion injury. Phosphorylation of Drp1 at Ser616 promotes its activation and enhances fission, contributing to mitochondrial fragmentation and cell death. Mff and Fis1 act as anchoring receptors on the mitochondrial surface, coordinating the recruitment and activity of Drp129,30. It was found that H/R induced the phosphorylation of Drp1 and increased the expression of its receptors Mff and Fis1. Notably, the introduction of 2-APB inhibited the phosphorylation of Drp1 and reduced the expression levels of Mff and Fis1, restoring their levels to near-normal values (p < 0.01, Fig. 3J and M). These results indicated that 2-APB simultaneously targets mitochondrial function and structure in cardiomyocytes and protects mitochondrial homeostasis after H/R. To further evaluate oxidative stress, we performed ROS imaging using DCFHA-DA. The results showed that ROS levels significantly increased at 3 h and 6 h after H/R injury, and treatment with 2-APB notably reduced ROS accumulation. These results were consistent with the preservation of mitochondrial structure and function by 2-APB.

2-APB reduces H/R mediated cytoplasmic and [Ca2+]m overload in cardiomyocytes

It has been suggested that oxidative stress injury triggered by MI/R activates ITPR1 activation. This, in turn, facilitates the release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) into the cytoplasm, resulting in [Ca2+]i overload. Furthermore, the excessive cytoplasmic calcium is absorbed by the mitochondria, leading to [Ca2+]m overload, ultimately reducing ATP production15. Moreover, the reduction of ATP contributes to the attenuation of the calcium cycle facilitated by the ER. This, in turn, fosters a mutual aggravation of [Ca2+]i overload and [Ca2+]m overload, resulting in the death of cardiomyocytes31. Double staining for [Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m depicted that H/R in cardiomyocytes resulted in a significant increase in [Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m (p < 0.01, p < 0.001,Fig. 4A and C). MCU is known to be critical for maintaining [Ca2+]i homeostasis by regulating [Ca2+]m uptake. Mitochondria take up Ca2+ through MCU, and NCX (Na+/Ca2+ exchanger) pumps out the accumulated Ca2+. The data revealed that the level of MCU protein was upregulated in the cardiomyocytes of the H/R group, and 2-APB treatment decreased the MCU protein level, but NCX remained unchanged after H/R and after 2-APB treatment (p < 0.01, Fig. 4D and F).

2-APB ameliorates [Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m overload in cardiomyocytes after hypoxia/reoxygenation. (A–C). Fluo-4 cellular calcium and Rhod-2 mitochondrial calcium staining in cardiomyocytes after H/R, scale bar = 50 μm. (D–F). Western-blot analysis of MCU and NCX protein levels in cardiomyocytes after H/R. The experiment was repeated three times. Data represent mean ± SD. **p < 0. 01, ***p < 0. 001.

The data indicate a possibility that 2-APB may ameliorate [Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m overload in cardiomyocytes following H/R through inhibition of MCU.

MCU activation attenuates the protective effect of 2-APB on mitochondria

At the subcellular level, 2-APB sustained mitochondrial function subsequent to H/R in cardiomyocytes. When 2-APB was present, the introduction of the MCU activator spermine (Spe) led to a surge in mitochondrial fission (Fig. 5A). A significant reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential was observed (p < 0.01, Fig. 5B and C), indicating that MCU activation attenuated the protective impact of 2-APB on mitochondrial function. Western blot analysis yielded findings where the levels of mitochondrial fission proteins Drp1, Mff, and Fis1 underwent an increase upon MCU activation (p < 0.05–0.01, Fig. 5D and G).

2-APB protects mitochondrial function by regulating the ITPR1-MCU signaling pathway. (A). Mitochondrial TOM20 immunofluorescence observation of mitochondrial structural changes after 2-APB and Spe treatment, scale bar = 25 μm; enlarged scale bar = 10 μm. (B–C). JC-1 probe detects changes in mitochondrial membrane potential after 2-APB and Spe treatment, scale bar = 100 μm. (D–G). Western-blot analysis of protein levels of mitochondrial fission proteins after MCU activation. The experiment was repeated three times. Data represent mean ± SD. *p < 0. 05, **p < 0. 01, ***p < 0. 001.

These findings suggest that 2-APB safeguards mitochondrial function by inhibiting the ITPR1-MCU signaling pathway.

Discussion

Ischemic heart disease stands as the primary contributor to cardiovascular mortality. While thrombolysis and percutaneous coronary intervention have demonstrated their effectiveness in addressing ischemia and reperfusion injury and elucidating the underlying pathological process of ischemic heart disease, laboratory studies suggest further protection is possible. Consequently, extensive research is dedicated to ushering fresh therapeutic avenues into clinical practice. Mitochondrial dysfunction plays a key role in the pathogenesis of ischemia, reperfusion injury, and cardiomyopathy8. This investigation presents novel findings that elucidate the protective influence of 2-APB in the context of MI/R injury. Dysregulation of mitochondrial energy metabolism and [Ca2+]i may impair cardiomyocyte function.

Consequently, advocating the augmentation of mitochondrial function emerges as a therapeutic strategy to minimize MI/R injury. Preserved function of complex I is associated with improved cardiac function. The findings of this study demonstrated that ITPR1 is activated after MI/R and leads to [Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m overload through the ITPR1-MCU pathway, whereas 2-APB reverses calcium imbalance and maintains cardiomyocyte function. This highlights the critical interplay between intracellular organelles during MI/R, where ITPR1-mediated calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the cytoplasm, coupled with mitochondrial MCU uptake, serves as a central axis in cardiomyocyte fate determination. Targeting this axis provides an opportunity to both preserve mitochondrial function and attenuate cellular stress, a strategy increasingly validated across diverse pathological contexts32,33,34. The excessive accumulation of [Ca2+]m holds a pivotal position in developing heart ailments, such as MI/R injury. Consequently, the regulation of [Ca2+]m influx is a determining factor influencing the destiny of cardiomyocytes during MI/R periods35. Likewise, the data of this study suggests that 2-APB attenuates myocardial mitochondrial damage caused by calcium imbalance through the ITPR1-MCU pathway. The dual regulation of calcium flux and mitochondrial bioenergetics by 2-APB is particularly notable. Beyond attenuating [Ca2+]m overload, 2-APB appears to normalize mitochondrial fusion-fission dynamics, a balance crucial for maintaining mitochondrial homeostasis and function under stress conditions33,36,37. This dual role emphasizes 2-APB’s potential to address multifactorial damage pathways in MI/R injury. In addition, we observed that H/R induced a significant increase in ROS production in cardiomyocytes, which was markedly suppressed by 2-APB treatment, as confirmed by DCFHA-DA fluorescence imaging. These findings suggest that 2-APB not only mitigates mitochondrial Ca²⁺ overload but also attenuates oxidative stress, further contributing to the preservation of mitochondrial function during I/R injury. Although this study primarily focused on Ca²⁺-mediated mitochondrial stress, additional mechanisms—such as ER stress, mitophagy, mitochondrial biogenesis, and inflammasome activation—are also recognized contributors to ROS production and cardiomyocyte injury following MI/R. These aspects warrant further investigation in future studies to provide a more comprehensive understanding. The MCU-mediated Ca2+ uptake orchestrates Ca2+ handling among mitochondria and cytosol to ameliorate cytosolic Ca2+overload–induced cardiomyocyte death38 thereby exerting cardioprotective effects during MI/R, providing new targets for the treatment and prevention of MI/R injury direction. However, it remains crucial to explore the tissue-specific dynamics of MCU expression and its potential compensatory mechanisms in chronic settings. For example, sustained MCU activation in non-cardiomyocytes during chronic ischemia could exacerbate systemic energy imbalances and promote pathological remodeling39. This underscores the need for tissue-specific drug delivery strategies to optimize therapeutic outcomes.

MI/R injury is a common clinical, pathophysiological phenomenon affected by various complex pathological mechanisms40,41. The research on the pathogenesis of MI/R injury, such as Ca2+ overload and mitochondrial energy metabolism disorder, has received more attention in recent years42,43. Recent research has revealed that mitochondrial permeability transition holds relevance in the developmental stages and during instances of regulated necrosis within cardiac pathologies. The regulatory control governing permeability transition occurs through calcium homeostasis, thereby underlining its pivotal role in cardiomyocytes. Consistent with this perspective, the findings of this study showed that there exists an elevation in ITPR1 protein levels during MI/R, which may promote the release of [Ca2+]m into the cytoplasm, resulting in a baseline [Ca2+]i overload.This study aligns with previous findings linking ITPR1 hyperactivation to both mitochondrial calcium overload and oxidative damage32,44. Notably, the interplay between ITPR1 and MCU is emerging as a critical modulator of cellular stress response, with potential implications extending beyond acute MI/R to chronic heart failure and metabolic syndromes39. MCU controls [Ca2+]i entry into mitochondria, and MCU overexpression improved sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ loading and mitochondrial energetics45. Increased MCU expression levels lead to mitochondrial metabolic arrest and fission46,47. Mitochondrial fusion and fission are the key to maintaining functional mitochondria. The intricate equilibrium between fission and fusion processes plays a pivotal role in upholding the functionality of mitochondria. This equilibrium is instrumental in functions such as sustaining the membrane potential (ΔΨm), fostering ATP production, and generating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (mtROS), among other functions48,49. It is clear that an optimal level of mitochondria Ca2+ assumes significance in preventing the onset of mitochondrial dysfunction and the ensuing cardiac pathologies amid episodes of cardiac stress. After MI/R, the MCU protein level is upregulated. The 2-APB inhibits ITPR1 while reducing MCU protein level, controls [Ca2+]i transport, and reduces myocardial cell injury caused by abnormal calcium signals. Future studies could explore the synergistic effects of 2-APB with antioxidant therapies or modulators of mitochondrial biogenesis, aiming to achieve a more comprehensive restoration of cellular function39,50. Since the isolation of primary cardiomyocytes may affect their viability and induce oxidative stress, these effects may underestimate the damage caused by MI/R injury and the protective effect of 2-APB on the heart.

In conclusion, the study has revealed that 2-APB plays a regulatory role in balancing [Ca2+]i/[Ca2+]m and mitigating mitochondrial damage via the ITPR1-MCU pathway. This discovery introduces a potential novel approach to addressing cardiac dysfunction induced by MI/R injury in myocardial infarction. Specifically, 2-APB treatment significantly improved left ventricular systolic function, as evidenced by enhanced ejection fraction EF% and FS%, and alleviated adverse ventricular remodeling indicated by reduced LVDd and LVDs. Additionally, 2-APB attenuated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and maintained mitochondrial ultrastructure, demonstrating its multifaceted protective effects on cardiac morphology and organelle integrity post-MI/R. While 2-APB demonstrates promise, a broader investigation into alternative MCU inhibitors, their pharmacokinetics, and their potential combinatory use in clinical settings is warranted. Additionally, leveraging advanced bioinformatics and high-throughput screening could accelerate the identification of novel ITPR1-MCU modulators for translational research. To support this translational goal, a deeper understanding of 2-APB’s pharmacological profile is required, the present study employed a single-dose protocol based on previous literature, and did not evaluate dose-response relationships or alternative timing strategies. Future investigations will be necessary to systematically assess the optimal dose and therapeutic time window of 2-APB for maximal cardioprotection and clinical translation. Moreover, while our findings demonstrate the acute benefits of 2-APB within 72 h post-MI/R, cardiac remodeling is a long-term process. The sustained effects of 2-APB on myocardial structure and function beyond the acute phase remain to be elucidated. And targeting the MCU-complex therapeutically, even days after infarction, could yield benefits if a suitable, permeable, and non-toxic MCU-complex inhibitory drug is identified51.Investigating 2-APB long-term therapeutic potential, as well as its efficacy in combination with other modulators of the MCU complex, will be critical for advancing 2-APB toward clinical application. Future studies should also determine whether the acute benefits observed here translate into improved outcomes in chronic MI/R injury.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

12 December 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-31395-2

Abbreviations

- MI/R :

-

Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion

- ITPR1:

-

Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor

- 2-APB :

-

2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane

- MCU:

-

Mitochondrial calcium uniporter

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- MEM:

-

Minimum essential medium

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- H/R:

-

Hypoxia/reoxygenation

- WGA:

-

Wheat germ agglutinin

- ROS :

-

Reactive oxygen species

- Spe :

-

Spermine

- ER :

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- EF:

-

Ejection fraction

- FS :

-

Fractional shortening

- LVIDd:

-

End-diastolic left ventricular diameter

- LVIDs :

-

End-systolic left ventricular diameter

- NCX:

-

Na+/Ca2+ exchangers

References

Quan, W. et al. Cardioprotective effect of Rosmarinic acid against myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury via suppression of the NF-κB inflammatory signalling pathway and ROS production in mice. Pharm. Biol. 59, 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/13880209.2021.1878236 (2021).

Mancini, G. B. et al. Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of stable ischemic heart disease. Can. J. Cardiol. 30, 837–849. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2014.05.013 (2014).

Cao, Y. et al. Activation of γ2-AMPK suppresses ribosome biogenesis and protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circ. Res. 121, 1182–1191. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.117.311159 (2017).

Quan, X. et al. The role of LR-TIMAP/PP1c complex in the occurrence and development of no-reflow. EBioMedicine 65, 103251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2021.103251 (2021).

Huyut, Z., Yildizhan, K. & Altındağ, F. The effects of Berberine and Curcumin on cardiac, lipid profile and fibrosis markers in cyclophosphamide-induced cardiac damage: the role of the TRPM2 channel. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 38, e23783. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbt.23783 (2024).

Ma, X. H. et al. ALOX15-launched PUFA-phospholipids peroxidation increases the susceptibility of ferroptosis in ischemia-induced myocardial damage. Signal. Transduct. Target. Therapy. 7, 288. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01090-z (2022).

Stoll, S. et al. The Valosin-Containing protein protects the heart against pathological Ca2+ overload by modulating Ca2+ uptake proteins. Toxicol. Sci. 171, 473–484. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfz164 (2019).

Mughal, W. et al. Myocardin regulates mitochondrial calcium homeostasis and prevents permeability transition. Cell Death Differ. 25, 1732–1748. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41418-018-0073-z (2018).

Zhu, F. et al. Protective effects of Nicorandil against cerebral injury in a swine cardiac arrest model. Exp.Ther. Med. 16, 37–44. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2018.6136 (2018).

Wu, Q. et al. Sufentanil preconditioning protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via miR-125a/DRAM2 axis. Cell. Cycle (Georgetown Tex). 20, 383–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384101.2021.1875668 (2021).

Zhu, H. et al. Melatonin protected cardiac microvascular endothelial cells against oxidative stress injury via suppression of IP3R-[Ca(2+)]c/VDAC-[Ca(2+)]m axis by activation of MAPK/ERK signaling pathway. Cell. Stress Chaperones. 23, 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12192-017-0827-4 (2018).

Hu, S., Zhu, P., Zhou, H., Zhang, Y. & Chen, Y. Melatonin-Induced protective effects on cardiomyocytes against reperfusion injury partly through modulation of IP3R and SERCA2a via activation of ERK1. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 110, 44–51. https://doi.org/10.5935/abc.20180008 (2018).

Kwong, J. Q. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter in the heart: energetics and beyond. J. Physiol. 595, 3743–3751. https://doi.org/10.1113/jp273059 (2017).

Viola, H. M. & Hool, L. C. How does calcium regulate mitochondrial energetics in the heart? - new insights. Heart Lung Circ. 23, 602–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2014.02.009 (2014).

Zhou, H., Wang, J., Zhu, P., Hu, S. & Ren, J. Ripk3 regulates cardiac microvascular reperfusion injury: the role of IP3R-dependent calcium overload, XO-mediated oxidative stress and F-action/filopodia-based cellular migration. Cell. Signal. 45, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.01.020 (2018).

Zhu, P. et al. Ripk3 promotes ER stress-induced necroptosis in cardiac IR injury: A mechanism involving calcium overload/xo/ros/mptp pathway. Redox Biol. 16, 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2018.02.019 (2018).

Yıldızhan, K. & Nazıroğlu, M. Protective role of selenium on MPP(+) and homocysteine-induced TRPM2 channel activation in SH-SY5Y cells. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 42, 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/10799893.2021.1981381 (2022).

Shen, Y. C. et al. Two benzene rings with a Boron atom comprise the core structure of 2-APB responsible for the Anti-Oxidative and protective effect on the Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced rat heart injury. Antioxid. (Basel Switzerland). 10 https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox10111667 (2021).

Yıldızhan, K. & Nazıroğlu, M. N. M. D. A. Receptor activation stimulates Hypoxia-Induced TRPM2 channel activation, mitochondrial oxidative stress, and apoptosis in neuronal cell line: modular role of memantine. Brain Res. 1803, 148232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2023.148232 (2023).

Morihara, H. et al. 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl Borate provides an anti-oxidative effect and mediates cardioprotection during ischemia reperfusion in mice. PloS One. 12, e0189948. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189948 (2017).

Wang, J., Toan, S., Li, R. & Zhou, H. Melatonin fine-tunes intracellular calcium signals and eliminates myocardial damage through the IP3R/MCU pathways in cardiorenal syndrome type 3. Biochem. Pharmacol. 174, 113832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113832 (2020).

Wang, M. et al. Myricitrin protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury: involvement of heat shock protein 90. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 353. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2017.00353 (2017).

Wu, L., Tan, J. L., Chen, Z. Y. & Huang, G. Cardioprotection of post-ischemic moderate ROS against ischemia/reperfusion via STAT3-induced the Inhibition of MCU opening. Basic Res. Cardiol. 114, 39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00395-019-0747-9 (2019).

Huang, K. Y. et al. Metformin suppresses inflammation and apoptosis of myocardiocytes by inhibiting autophagy in a model of ischemia-reperfusion injury. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 16, 2559–2579. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.40823 (2020).

Aliyu, M. et al. Interleukin-6 cytokine: an overview of the immune regulation, immune dysregulation, and therapeutic approach. Int. Immunopharmacol. 111, 109130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109130 (2022).

Andrieux, P., Chevillard, C., Cunha-Neto, E. & Nunes, J. P. S. Mitochondria as a cellular hub in infection and inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111338 (2021).

Hao, T. et al. An injectable Dual-Function hydrogel protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by modulating ROS/NO disequilibrium. Advanced science (Weinheim, Baden-Wurttemberg. Germany) 9, e2105408. https://doi.org/10.1002/advs.202105408 (2022).

Jiang, L. et al. Proteomic analysis reveals ginsenoside Rb1 attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through inhibiting ROS production from mitochondrial complex I. Theranostics 11, 1703–1720. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.43895 (2021).

Otera, H. et al. Mff is an essential factor for mitochondrial recruitment of Drp1 during mitochondrial fission in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 191, 1141–1158. https://doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201007152 (2010).

Losón, O. C., Song, Z., Chen, H. & Chan, D. C. Fis1, mff, MiD49, and MiD51 mediate Drp1 recruitment in mitochondrial fission. Mol. Biol. Cell. 24, 659–667. https://doi.org/10.1091/mbc.E12-10-0721 (2013).

Zuo, S. et al. CRTH2 promotes Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through m-calpain. EMBO Mol. Med. 10 https://doi.org/10.15252/emmm.201708237 (2018).

Katona, M. et al. Capture at the ER-mitochondrial contacts licenses IP(3) receptors to stimulate local Ca(2+) transfer and oxidative metabolism. Nat. Commun. 13, 6779. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-34365-8 (2022).

Xiao, Z. et al. Trimetazidine affects mitochondrial calcium uniporter expression to restore ischemic heart function via reactive oxygen Species/NFκB pathway Inhibition. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 82 (2), 104–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0000000000001434 (2023).

Ahumada-Castro, U. et al. In the right place at the right time: regulation of cell metabolism by IP3R-Mediated Inter-Organelle Ca(2+) fluxes. Front. Cell. Dev. Biol. 9, 629522. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2021.629522 (2021).

Wang, P. et al. Elevated MCU expression by CaMKIIδB limits pathological cardiac remodeling. Circulation 145, 1067–1083. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.121.055841 (2022).

Yıldızhan, K., Huyut, Z. & Altındağ, F. Involvement of TRPM2 channel on Doxorubicin-Induced experimental cardiotoxicity model: protective role of selenium. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 201, 2458–2469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12011-022-03377-2 (2023).

Kadier, T. et al. MCU Inhibition protects against intestinal ischemia–reperfusion by inhibiting Drp1-dependent mitochondrial fission. Free Radic Biol. Med. 221, 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2024.05.024 (2024).

Liu, T., Yang, N., Sidor, A. & O’Rourke, B. M. C. U. Overexpression rescues Inotropy and reverses heart failure by reducing SR Ca(2+) leak. Circul. Res. 128, 1191–1204. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.120.318562 (2021).

Wang, J., Jiang, J., Hu, H. & Chen, L. MCU complex: exploring emerging targets and mechanisms of mitochondrial physiology and pathology. J. Adv. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2024.02.013 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Exosomal miR-17-3p alleviates programmed necrosis in cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating TIMP3 expression. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2022 (2785113). https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/2785113 (2022).

Xu, L. et al. H3K14 hyperacetylation–mediated c–Myc binding to the miR–30a–5p gene promoter under hypoxia postconditioning protects senescent cardiomyocytes from hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. Mol. Med. Rep. 23 https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2021.12107 (2021).

Cai, W. et al. Alox15/15-HpETE aggravates myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion injury by promoting cardiomyocyte ferroptosis. Circulation 147, 1444–1460. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.122.060257 (2023).

Subramani, J., Kundumani-Sridharan, V. & Das, K. C. Chaperone-Mediated autophagy of eNOS in myocardial Ischemia-Reperfusion injury. Circul. Res. 129, 930–945. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.120.317921 (2021).

Berridge, M. J. The inositol trisphosphate/calcium signaling pathway in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 96, 1261–1296. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00006.2016 (2016).

Huo, J. et al. MCUb induction protects the heart from postischemic remodeling. Circul. Res. 127, 379–390. https://doi.org/10.1161/circresaha.119.316369 (2020).

Belosludtsev, K. N., Dubinin, M. V., Belosludtseva, N. V. & Mironova, G. D. Mitochondrial Ca2+ transport: mechanisms, molecular structures, and role in cells. Biochem. Biokhimiia. 84, 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1134/s0006297919060026 (2019).

Pallafacchina, G., Zanin, S. & Rizzuto, R. Recent advances in the molecular mechanism of mitochondrial calcium uptake. F1000Research 7 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.15723.1 (2018).

Mao, C. et al. MiRNA-30a inhibits AECs-II apoptosis by blocking mitochondrial fission dependent on Drp-1. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 18, 2404–2416. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.12420 (2014).

Chen, J. et al. T cells display mitochondria hyperpolarization in human type 1 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 7, 10835. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11056-9 (2017).

D’Angelo, D. & Rizzuto, R. The mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU): molecular identity and role in human diseases. Biomolecules 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/biom13091304 (2023).

Banavath, H. N. et al. miR-181c activates mitochondrial calcium uptake by regulating MICU1 in the heart. J. Am. Heart Association. 8, e012919. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.119.012919 (2019).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81960085, 81960047, 82160086, 32460222), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2022MD723769), Guizhou Medical University Doctoral Research Initiation Fund (gyfybsky-2022-44), the Science and Technology Fund of Guizhou Provincial Health Department (No.qiankehepingtairencai-GCC[2022]040 − 1, qiankehezhicheng[2019]2800, qiankehezhicheng[2021]yiban063, qiankehejichu-ZK[2022]zhongdian043, qiankehechengguo-LC[2022]013, qiankehejichu-ZK[2023]yiban372), the Health and Family Planning Commission of Guizhou Province (qianweijianhan[2021]160, gzwkj2021-112), Provincial Key Medical Subject Construction Project of Health Commission of Guizhou Province and the National Key Medical Subject Construction Project of National Health Commission of China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZRC, WL, RZH, HLB made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. HLB, XC and BXC performed the experiments. RZH, HLB, and XC drafted the manuscript. ZRC, RZH, ZXC and XH revised the manuscript. XC, XH and WZ analyzed the data. WL, RZH, FW and FJL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care Welfare Committee of the Guizhou Medical University (No. 2201027). The study was reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent to participate

All authors are involved and aware of the study.

Consent for publication

All authors agree to the publication of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional Information

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, panels A-F were omitted from Figure 2.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bao, H., Chen, X., Hu, X. et al. 2-aminoethoxydiphenylborane intervenes intracellular calcium signaling and attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice through ITPR1/MCU pathway. Sci Rep 15, 29469 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14822-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14822-2