Abstract

Integrating renewable energy sources into the electricity grid requires accurate forecasts of solar power production. With the aim of enhancing the accuracy and reliability of forecasts, this study presents a comprehensive comparative analysis of eight state-of-the-art Deep Learning (DL) architectures—Autoencoder, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), Simple Recurrent Neural Network (SimpleRNN), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN), Transformer, and Lightweight Informer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting (InformerLite)—applied to solar power prediction using a dataset with 4,200 historical records and 20 meteorological and astronomical features. A comprehensive assessment of Root Mean Squared Error \(\:\left(\varvec{R}\varvec{M}\varvec{S}\varvec{E}\right)\), Mean Absolute Error \(\:\left(\varvec{M}\varvec{A}\varvec{E}\right)\), Mean Absolute Percentage Error \(\:\left(\varvec{M}\varvec{A}\varvec{P}\varvec{E}\right)\), and Coefficient of Determination \(\:\left({\varvec{R}}^{2}\right)\) metrics was performed on the training, validation, and test datasets. The TCN model had the greatest performance across all models, achieving a test R² of 0.7786, an \(\:\varvec{R}\varvec{M}\varvec{S}\varvec{E}\) of 429.4863, and a balanced relative standard deviation (\(\:\varvec{R}\varvec{S}\varvec{D}\)) of 0.6827, so exhibiting an exceptional capacity to capture temporal patterns. The Autoencoder achieved a \(\:{\varvec{R}}^{2}\) of 0.7648 and had the greatest overall performance on the entire dataset, resulting in a Whole \(\:{\varvec{R}}^{2}\) of 0.8437. In contrast, the Transformer model demonstrated significantly poorer performance (Test \(\:{\varvec{R}}^{2}\) = 0.0714), underscoring its limitations in this context without any architectural modifications. This study not only demonstrates the best DL models for solar power forecasting as qualified by useful statistical metrics, but also provides a scalable, interpretable, and extensible forecasting framework for real-world energy systems. The findings verify the informed DL integration to smart grid scenarios, laying the foundations for further developments in hybrid modeling, multi-horizon prediction, and deployment in resource-constrained environments with limited computational power and resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The continuously increasing world-wide demand for alternative sources of clean and sustainable energy has placed a bigger emphasis on the accurate forecasting of solar electricity production. One extremely exciting renewable energy source that requires precise prediction models to be included in the energy system as best as possible, enhance energy management, and ensure dependability is solar energy. Traditional time series forecasting methods fail to model well the complex, non-linear patterns present in solar power data1,2,3. As such, using advanced Deep Learning (DL) techniques to improve prediction accuracy has attracted growing attention. The purpose of this study is to evaluate in forecasting solar power generation the efficiency of eight DL algorithms: Lightweight Informer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting (InformerLite), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Autoencoders, Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), Transformer, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN). Several of these models, particularly sequence-based architectures such as LSTM, GRU, RNN, and TCN, have demonstrated strong capabilities in capturing temporal dependencies and non-linear interactions within large-scale time series datasets4. The study aims to identify the most reliable and accurate model for solar power forecasting by comparing several methods, thereby advancing renewable energy technology and its application in sustainable energy systems.

Precise prediction of solar power generation is essential for several reasons. First and foremost, it facilitates the seamless incorporation of solar energy into the electrical grid, thus aiding in the equilibrium of energy supply and demand and diminishing dependence on non-renewable energy sources. Accurate predictions, enable grid managers to properly control the energy storage systems, which reduce impacts due to the solar energy variations5. Furthermore, a reliable and accurate prediction is of great importance to ensure the financial profitability of solar energy by increasing the performance and controllability of solar parks. Thus, although operating expenses of the company have dropped, investment income has grown6. Reliable projections also facilitate the establishment of well-considered and knowledgeable judgments on next solar energy projects, so promoting the switch to renewable and sustainable energy sources. Effective assessments of solar energy generation, as a result, can help decrease the risk of power interruption and establish an available power supply by enhancing power system stability and reliability to the grid. Thus, to help meet global energy targets, support the environmental accountability of developers, and foster the technological advancements for renewable energy, enhancing the solar energy yield prediction capability is of paramount importance.

In solar power forecasting, DL has evolved into a powerful tool with clear benefits over more traditional methods. Sometimes the complex, nonlinear links and temporally dependent patterns in solar power data are too difficult for conventional statistical models to adequately depict. Conversely, DL algorithms excel in these fields and consequently have rather great success in time-series prediction. Using large datasets not readily visible with conventional approaches allows DL models to discover intricate patterns and trends7,8,9.

An accurate estimate of solar power output is crucial for achieving the highest level of integration of solar energy into the power system. However, due to the intricate and nonlinear characteristics of solar data, which are impacted by various climatic and environmental factors, existing forecasting algorithms are unable to accurately predict solar power output. Inappropriate grid management, higher running costs, and less reliability of solar power plants follow from this disparity. Finding and appreciating the best DL techniques for handling complex solar power data and generating accurate forecasts is crucial10.

The application of Machine Learning (ML) and DL in Photovoltaic (PV) systems has improved the performance, reliability, and predictability of solar energy applications. ML methods are everywhere utilized to accurately predict solar power generation and ambient conditions influencing PV yield11,12,13. On the other hand, DL approaches have proved to be highly successful for automation problems, for example defect detection in solar cells14, fault detection and performance predication15, surface condition monitoring via image classification16. In addition, advanced image process and computer vision techniques have allowed for accurate PV panel damage detection which further facilitates predictive maintenance and operating optimization17. These developments highlight the importance of smart algorithms in making PV systems smarter, more adaptive and more robust energy conversion tools.

The development of DL has boosted the credibility and accuracy of solar power prediction, mainly in fields like Electric Vehicle (EV) battery swap station, and integrated grid connection of renewable energy. For example, the application of LSTM models to forecast the solar power availability in EV swapping stations can contribute to an optimal scheduling of the battery charging, ultimately decreasing the reliance on the grid and improving energy efficiency18. DL techniques, including LSTM, AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA), and Dual Attention-based RNNs, have been evaluated for solar irradiance forecasting, with LSTM models exhibiting enhanced performance in error reduction and real-time application19. Although solar forecasting is a primary emphasis, the application of ML in infrastructure monitoring has also gained traction. Research employing magnetostrictive sensors alongside decision trees and neural networks has attained elevated classification accuracy for bridge health evaluation, demonstrating the adaptability of ML in sensor-driven predictive modeling20. The amalgamation of Random Forest (RF) and Deep Neural Network (DNN) with frequency domain data has facilitated real-time structural integrity monitoring in prototype beam bridges, demonstrating the wider application of these methods beyond energy sectors21.

Recent hybrid architectures, which combine recurrent with attention-based mechanisms, such as the Transformer-Infused Recurrent Neural Network (TIR), have proved effective in maintaining data complexity and temporal dependence22. Ensemble learning methods have therefore recently been attracting significant attention, such as Stack-based Ensemble Fusion with Meta-Neural Network (SEFMNN) and Extreme Gradient Boosting-Stacked Ensemble (XGB-SE), which have obtained state-of-the-art results in different regions by combining a variety of base-learners23. In addition, decomposition methods for example Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD) have also been widely used for enhancing model interpretability and prediction accuracy by extracting the intrinsic signal modes before inputting them to neural architectures including LSTM and Artificial Neural Network (ANN)24. Recent reviews have clarified the transformative effects of DL and ML technologies have on solar forecasting and potential to counter nonlinearities and uncertainties found in solar irradiance data, which in turn can help improve grid reliability and sustainable energy planning25. Additionally, recent advancements in modified ANN structures and lightweight Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) structures such as Regularized Lightweight Artificial Neural Network (RELAD-ANN) and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) also provide plausible ways to combine computational complexity and predictive performance for real-time world solar energy systems26.

This study aims to systematically evaluate the prediction of solar power output using multiple advanced DL algorithms. The particular aim of the study is to assess the accuracy of eight DL models—Autoencoders, GRU, RNN, LSTM, Transformer, CNN, TCN, and InformerLite—in forecasting solar power generation. By means of important performance criteria like Coefficient of Determination (R²) scores, Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), mean, Standard Deviation (SD), and Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) of the predictions generated on the test set, the study aims to evaluate the precision and dependability of these models. The goal of this work is to identify the most suitable DL algorithm for solar power generation prediction. This involves analyzing the models’ ability to faithfully depict complex time-based patterns and nonlinear linkages within the data. Moreover, the study also seeks to deliver actionable insights into the strengths and limitations of each model in the context of renewable energy forecasting, thereby supporting the integration of solar power into the energy grid. Through better understanding of how DL may improve solar power forecasting, the study advances more reliable and effective renewable energy systems. Finally, reaching these targets will offer important new perspectives on the field of renewable energy forecasting, thereby supporting better decision-making and solar power generation optimization.

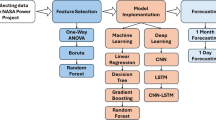

The objectives of the proposed research include the development of a robust and scalable model for accurate solar power prediction using state-of-the-art DL techniques. As shown in Fig. 1, a major contribution of this work is to extend beyond the conventional “Model Training” approach, testing a broad range of neural network architectures, judging them not only on predictive performance but also based on efficiency and deployability. It is intended to be extensible and modular in nature for example researchers should be able to easily add new models and types of data. Moreover, practical aspects such as uncertainty estimation and automatic result generation are emphasized, making the solution viable for real-world energy systems.

Methodology

Data presentation

In this study, this dataset comprises 4200 samples of historical records of solar power generation, and for each record, each annotated with total of 20 meteorological and astronomical input features and as well as one target output, the generated power in kilowatts. The input parameters include the temperature, humidity, pressure, precipitation, cloud cover at multi-levels altitude, solar radiation, wind level at different heights, and pressure levels, solar angle of incidence, solar position angle such as zenith and azimuth.

To analyze inter-feature relationships, this study calculated a correlation matrix as shown in Figure 2. This heatmap illustrates the positive or negative linear correlations between the variables. Shortwave radiation and zenith is correlated most strongly with the output power with the other variables of humidity and azimuth also having moderate correlation. Strong inter-correlations across different wind layers were evident, indicating redundancy that could be reduced by selecting of features.

Besides correlation analysis, Lasso regression was used to perform feature selection and to measure the importance of the independent variables against the target output. A resulting plot of feature importance is displayed in Fig. 3 and shortwave radiation is identified as the most indicative feature value, and then mean sea level pressure, wind speed at 80 m, and wind direction at 80 m also are influential. In contrast, the angle of incidence and azimuth were penalized to very low coefficients in practise, meaning that the angle of incidence and azimuth only weakly contributed to the predictive model under the sparsity constraint of the Lasso. These findings informed the future design of model inputs, allowing the elimination or reduction of low-impact characteristics to optimize training and enhance generalization.

Deep learning algorithms

An evaluation was performed to compare the predictive power of a few DL models in the estimation of solar PV power production. The proposed approach incorporates robust data pre-processing, an exploratory analysis, and several DL techniques to provide accurate solar power generation predictions. The end-to-end system is shown in Fig. 4.

Data Preparation

The work-flow starts by uploading a pre-processed dataset of historical solar plants generation as well as correlated meteorological variables. The dataset is split into training, validation and test sets in the ratio of (70:20:10) % to maintain neutrality while calculating the scores. The input space will be normalized with standardization through feature scaling. The data is restructured into time-sequence for modeling sequences with their temporal dependencies.

Exploratory data analysis and feature engineering

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) is performed prior to model estimation by a correlation matrix analysis which provides insight into the relationships between features and suggests feature selection. The variable names are recoded to have long names for the sake of intelligibility. Lasso regularization is used for feature importance quantification and dimensionality reduction. The interpretations are visualized to help understanding and interpretation of the model decisions.

Model Building

A broad array of DL models is employed to assess the efficacy of different architectures in predicting solar power generation. The configuration features an Autoencoder, designed as a dense feedforward network with a bottleneck layer to acquire compact latent representations of the input characteristics. RNNs, namely Simple Recurrent Neural Network (SimpleRNN), GRU, and LSTM, are used to capture temporal correlations in data because to their memory-based architecture. CNNs use one-dimensional convolutional layers to extract localized temporal patterns. The TCN enhances temporal learning by using dilated causal convolutions and skip connections, which aids in the detection of long-range temporal patterns. The Transformer can handle complex relationships and take sequences into consideration at the same time due to its self-attention mechanisms. InformerLite, a lightweight and efficient variant of Transformer, is well matched to the time series forecasting task. All models are implemented with the Keras Application Programming Interface (API), backend TensorFlow 2.16, and as compared to this model, enhanced compatibility, scalability, and hardware acceleration support are guaranteed.

Training and evaluation

Models are constructed with the Adam optimizer and trained with early stopping and learning rate reduction callbacks. After learning, the inference is performed on all the datasets. Predictions are transformed back to the original scale. Evaluation metrics include RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and R2 are computed on training, validation, and test sets. Several visualizations — including loss curves, scatter plots, solar azimuth comparisons, residual histograms, and Confidence Intervals (CIs) — are produced for visual validation.

During testing Monte Carlo dropout is used to calculate uncertainty intervals (95% confidence), contributing to the interpretability of the model.

Result collection

All metrics are stored in a uniform format as CSV files for reproducibility and downstream analysis. Other third-party tests for residual behavior, such as Shapiro–Wilk, Jarque–Bera, and Ljung–Box (if implemented) are also applied. This work also reports model size, training/inference time, and RSD of test predictions for a more complete comparison.

Figure 4 provides a complete overview of the entire methodology pipeline, from raw data ingestion to model evaluation and result export.

Experimental setup and configuration parameters

The experimental design of this work was meticulously organized to guarantee uniformity, repeatability, and dependable model assessment. The solar power generation recovery dataset was preprocessed with standard normalization and divided into training, validation and test sets in a stratified manner. This work trained multiple models with various DL architectures and fixed learning rate Adam optimization method with early stopping to avoid overfitting. To evaluate the performance, this research used RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and R² measures over various data partitions. Furthermore, this research also used Monte Carlo dropout for predicting uncertainty. Table 1 gives a comprehensive overview of the major parameters applied in this study, including the configuration of the data processing, the choice of the model, the options in the training, and the diagnostic tests.

Evaluation metrics

A composite accuracy measure consisting of accuracy, reliability, and statistical consistency measures was adopted to provide a complete characterization to the forecasting performance of the proposed DL models for solar power generation. Equation (1), Eq. (2), and Equation (3) were applied to the aggregate data, training data, and test data to compute R2 for the aggregate, training and test data sets respectively. These scores quantify the proportion of variance in the observed data that is explained by the predictions. To assess prediction accuracy more concretely, standard error-based metrics were applied. The RMSE, which penalizes larger deviations, is presented in Eq. (4). The MAE, which measures the average magnitude of errors without considering their direction, is formulated in Eq. (5). Similarly, Eq. (6) defines the MAPE, a relative metric that expresses errors as a percentage of the actual values. To enhance comprehension of the distributional characteristics of model outputs on the test set, the Mean of Test Predictions is determined as illustrated in Eq. (7), and its SD is derived using Eq. (8). Finally, Eq. (9) delineates the RSD, which provides a standardized measure of variability in relation to the mean. Collectively, these criteria offer a thorough assessment of predictive performance concerning accuracy, stability, and generality.

Results

To evaluate the performance of a number of advanced DNN models for predicting solar power generation, this study performed extensive experiments with a variety of architectures. Model performance was tested on three sets: training, validation, and testing. RMSE, MAE, MAPE, R² were accepted as standard regression measures of performance. In addition, uncertainty quantification and residual analysis were carried out for diagnostic purposes.

Model complexity and efficiency

Table 2 delineates the intricacies of model complexity and runtime. The Autoencoder had the highest computational efficiency, characterized by the minimal parameter count and compact model size (3,537 parameters, approximately 75 KB), with the briefest training duration (around 5.7 s). Conversely, the Transformer and TCN, despite their greater complexity (93,574 and 86,913 parameters respectively), need considerably longer training durations (~ 17.8s and ~ 32.1s).

Model training and convergence behavior

Figure 5 shows the MSE loss of each model on training and validation. From the models, among the models Autoencoder and TCN showed the stable and faster convergence. On the other hand, the Transformer model had large validate loss implying overfitting or not enough feature extraction in this domain.

Prediction accuracy on training data

Figure 6 illustrates the prediction performance of the models on the training set. The Autoencoder, TCN, and SimpleRNN models exhibited a high correlation between anticipated and actual values, signifying robust learning capability. Table 3 corroborates this, indicating that the Autoencoder attained the greatest R² of 0.8677, with the TCN closely following at R² = 0.8374. Conversely, the Transformer had a markedly worse performance, achieving a R² of just 0.1551.

Generalization to validation set

For comparisons the model predictions on the test set are depicted in Fig. 7, revealing that models such as the Autoencoder and TCN did well on data it had experienced before. This is reinforced by Table 4, it is shown that the Autoencoder obtains R² of 0.7978 and the TCN follows with 0.7853. These results demonstrate strong generalization.

Azimuthal feature interpretability

Figures 8 and 9 analyze how model predictions vary with solar azimuth, a key feature in solar forecasting. Across both training and test sets, models like the Autoencoder and TCN consistently tracked the real values, reinforcing their robustness and capacity to incorporate temporal and directional features effectively.

Residual error distribution

The residual distributions shown in Fig. 10 provide further insights into model reliability. The Autoencoder and TCN had relatively symmetric and narrow error distributions, suggesting minimal bias and lower variance in predictions. The Transformer, on the other hand, exhibited a broader spread and signs of skewness, aligning with its poor test performance.

Uncertainty Estimation with Monte Carlo dropout

Figure 11 shows that the 95% CIs produced with Monte Carlo dropout applied to the test predictions. The TCN and Autoencoder models come out on top in terms of providing accurate predictions and also relatively tight confidence bands, indicating high prediction confidence and robustness. The high degree of reliability is essential in real-world applications, for example in grid management of solar energy, where the uncertainty estimation has a significant impact for the operational decision process.

Test set performance comparison

Table 5 presents test set performance, ordered by R². The TCN led with an R² of 0.7786, followed by the Autoencoder (0.7648) and SimpleRNN (0.7303). The Transformer again performed the worst (R² = 0.0714), affirming its unsuitability in this context without significant tuning or architectural adaptation.

Extended model evaluation

Further insight into model behaviour is studied with other metrics, such as RSD and global R² over the entire dataset as shown in Table 6. The Autoencoder obtained the highest R² (Whole), overall (0.8437), indicating good performance over all partitions. In addition, the RSD of (RSD = 0.7499) was in reasonable limits between variability and accuracy.

Predicted versus actual solar power generation (in kW) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the first 200 samples from the test dataset, using Monte Carlo dropout-based uncertainty estimation for different deep learning models: (a) Transformer, (b) LSTM, (c) GRU, (d) CNN, (e) InformerLite, (f) SimpleRNN, (g) Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN), and (h) Autoencoder.

Future work

Future studies should focus on the scalability, robustness, and adaptability of DL models for solar power prediction. One interesting bracket includes hybrid architectures that merge convolutional layers with temporal models such as LSTM or attention-based transformers. This kind of hibridization could allow for the simultaneous modeling of short-term characteristics and long-range dependence in solar power data. Similarly, ensemble methods such as model averaging or stacking, which could combine the power of different architectures and make more accurate and smoother predictions, are also worth investigating. Validation across geographic locations with varying climates would be needed to ensure the models generalize well across sites. This could be achieved with domain adaptation approaches or federated learning methodologies in order to diminish the necessity of remedial training on a per-site basis. Furthermore, include satellite-derived variables such as cloud drift, irradiance maps and atmospheric transparency from products like Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) or Himawari can be a great help for the model in order to address fast weather transitions. Future efforts will also explore extending the models to support multi-horizon forecasting, enabling predictions several hours ahead to better support grid operations and energy storage management. Lastly, optimizing the computational efficiency of models—especially those based on transformers—will be important for enabling real-time deployment in embedded systems or edge computing environments, where resource constraints are a key consideration.

Conclusion

This study evaluated a set of advanced DL models—including RNN variants (SimpleRNN, GRU, LSTM), CNN, Transformer, Informer, Autoencoder, and TCN —for the task of solar power forecasting using a diverse range of meteorological and solar positional features. The TCN architecture achieved the best predictive performance according to performance metrics in general, particularly on the test data, which reflected its strong capacity for capturing the significant temporal patterns in an organized, robust and general manner. The Autoencoder model also exhibited good performance across the board, as marginally the best sequence-based model and in terms of clustering representing low-dimensional temporal features. On the other hand, the Transformer model did much worse than anticipated, by achieving the lowest R² on the test data, and the findings suggest it may not be suitable for this forecasting task given the input feature set and length of sequence, at least. GRU and LSTM based models had moderate success but appeared to underfit to longer dependencies without the presence of further attention mechanisms or architectural modifications. Reasonable level of the test performance on InformerLite and CNN’s better to capture short-term and mid-term of the temporal dependency. Nevertheless, this study is not without limitations. This dataset is geographically limited, and the generalization of these models in different climatic zones or terrains may be limited. The experiments only consider the next single time step prediction and do not encompass the multi-horizon complexity that is relevant to energy planning and control. Additionally, no satellite imagery or real-time sky state information are included in the model inputs, which could be useful to enhance forecast accuracy under overcast conditions. Overall, the models exhibit very strong performance in the present settings but more improvements and wider testing are necessary for deployment in practice.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Abbreviation:

-

Full Form

- AI:

-

Artificial Intelligence

- ANN:

-

Artificial Neural Network

- API:

-

Application Programming Interface

- ARIMA:

-

AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- CNN:

-

Convolutional Neural Network

- DL:

-

Deep Learning

- DNN:

-

Deep Neural Network

- EDA:

-

Exploratory Data Analysis

- EEMD:

-

Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition

- EV:

-

Electric Vehicle

- GBM:

-

Gradient Boosting Machine

- GOES:

-

Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite

- GRU:

-

Gated Recurrent Unit

- InformerLite:

-

Lightweight Informer for Long Sequence Time-Series Forecasting

- LightGBM:

-

Light Gradient Boosting Machine

- LSTM:

-

Long Short-Term Memory

- MAE:

-

Mean Absolute Error

- MAPE:

-

Mean Absolute Percentage Error

- ML:

-

Machine Learning

- MSE:

-

Mean Squared Error

- PV:

-

Photovoltaic

- RELAD-ANN:

-

Regularized Lightweight Artificial Neural Network

- RF:

-

Random Forest

- RMSE:

-

Root Mean Squared Error

- RNN:

-

Recurrent Neural Network

- RSD:

-

Relative Standard Deviation

- R²:

-

Coefficient of Determination

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SEFMNN:

-

Stack-based Ensemble Fusion with Meta-Neural Network

- SimpleRNN:

-

Simple Recurrent Neural Network

- TCN:

-

Temporal Convolutional Network

- TIR:

-

Transformer-Infused Recurrent Neural Network

- XGB-SE:

-

Extreme Gradient Boosting - Stacked Ensemble

References

Abdelsattar, M., AbdelMoety, A. & Emad-Eldeen, A. in 2023 24th International Middle East Power System Conference (MEPCON). 1–6 (IEEE).

Abdelsattar, M., AbdelMoety, A. & Emad-Eldeen, A. Comparative analysis of machine learning techniques for fault detection in solar panel systems. SVU-International J. Eng. Sci. Appl. 5, 140–152 (2024).

Elsaraiti, M. & Merabet, A. Solar power forecasting using deep learning techniques. IEEE Access. 10, 31692–31698 (2022).

Khortsriwong, N. et al. Performance of deep learning techniques for forecasting PV power generation: a case study on a 1.5 mwp floating PV power plant. Energies 16, 2119 (2023).

Kavakci, G., Cicekdag, B. & Ertekin, S. Time series prediction of solar power generation using trend decomposition. Energy Technol. 12, 2300914 (2024).

Rangaraju, S., Bhaumik, A. & Le Vo, P. A novel SGD-DLSTM-based efficient model for solar power generation forecasting system. Energy Harvesting Syst. 10, 349–363 (2023).

Dehghan, F., Moghaddam, M. P. & Imani, M. in 2023 8th International Conference on Technology and Energy Management (ICTEM). 1–5 (IEEE).

Li, J., Zhang, C. & Sun, B. Two-stage hybrid deep learning with strong adaptability for detailed day-ahead photovoltaic power forecasting. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy. 14, 193–205 (2022).

Amreen, T. S., Panigrahi, R. & Patne, N. in 5th International conference on energy, power and environment: towards flexible green energy technologies (ICEPE). 1–6 (IEEE). (2023).

Devi, K. & Srivenkatesh, M. An advanced hybrid Meta-Heuristic model for solar power generation forecasting via ensemble deep learning. Ingénierie des. Systèmes d’Information 28, 1395 (2023).

Abdelsattar, M., AbdelMoety, A. & Emad-Eldeen, A. Comparative analysis of machine learning techniques for temperature and humidity prediction in photovoltaic environments. Sci. Rep. 15, 15650 (2025).

Abdelsattar, M., AbdelMoety, A. & Emad-Eldeen, A. Machine Learning-Based prediction of illuminance and ultraviolet irradiance in photovoltaic systems. International J. Holist. Research, 1–14 (2024).

Abdelsattar, M., Ismeil, M. A., Azim, M. A. & AbdelMoety, A. & Emad-Eldeen, A. Assessing machine learning approaches for photovoltaic energy prediction in sustainable energy systems. IEEE Access 12 (2024).

Abdelsattar, M., AbdelMoety, A. & Ismeil, M. A. & Emad-Eldeen, A. Automated defect detection in solar cell images using deep learning algorithms. IEEE Access 13 (2025).

Abdelsattar, M., AbdelMoety, A. & Emad-Eldeen, A. Advanced machine learning techniques for predicting power generation and fault detection in solar photovoltaic systems. Neural Comput. Applications 37, 1–20 (2025).

Abdelsattar, M., Rasslan, A. A. A. & Emad-Eldeen, A. Detecting dusty and clean photovoltaic surfaces using MobileNet variants for image classification. SVU-International J. Eng. Sci. Appl. 6, 9–18 (2025).

Abdelsattar, M., AbdelMoety, A. & Emad-Eldeen, A. Applying image processing and computer vision for damage detection in photovoltaic panels. Mansoura Eng. J. 50, 2 (2025).

Chawrasia, S., Hembram, D., Bose, D. & Chanda, C. Design of solar battery swapping station for EV using LSTM-assisted solar power forecasting. Microsyst. Technol. 30, 1087–1098 (2024).

Kumar Chawrasia, S., Hembram, D., Bose, D. & Chanda, C. K. Deep learning assisted solar forecasting for battery swapping stations. Energy Sour. Part A Recover. Utilization Environ. Eff. 46, 3381–3402 (2024).

Dolui, C., Devi, S. F., Dasadhikari, S. & Roy, D. in IEEE Pune Section International Conference (PuneCon). 1–6 (IEEE). (2023).

Dolui, C. & Roy, D. Advancement of Bridge health monitoring using magnetostrictive sensor with machine learning techniques. Nondestructive Test. Evaluation, 1–22 (2024).

Naveed, M. S. et al. Leveraging advanced AI algorithms with transformer-infused recurrent neural networks to optimize solar irradiance forecasting. Front. Energy Res. 12, 1485690 (2024).

Naveed, M. et al. Enhanced accuracy in solar irradiance forecasting through machine learning stack-based ensemble approach. International J. Green. Energy 22, 1–24 (2025).

Guo, Y. et al. Ensemble-Empirical-Mode-Decomposition (EEMD) on SWH prediction: the effect of decomposed imfs, continuous prediction duration, and data-driven models. Ocean Eng. 324, 120755 (2025).

Nadeem, A. et al. AI-Driven precision in solar forecasting: breakthroughs in machine learning and deep learning. AIMS Geosci. 10, 684–734 (2024).

Hanif, M. F. et al. Advancing solar energy forecasting with modified ANN and light GBM learning algorithms. AIMS Energy. 12, 350–386 (2024).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

“Montaser Abdelsattar , Mohamed A. Azim , Ahmed AbdelMoety and Ahmed Emad-Eldeen wrote the main manuscript text and prepared figures 1-11. All authors reviewed the manuscript.”

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdelsattar, M., Azim, M.A., AbdelMoety, A. et al. Comparative analysis of deep learning architectures in solar power prediction. Sci Rep 15, 31729 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14908-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-14908-x