Abstract

In this study, we investigate the quantum dynamics of spin-0 scalar particles interacting with both scalar and vector potentials in the background of a cosmic string space-time, under the influence of a quantum flux field. The behavior of the scalar particles is governed by the Klein-Gordon equation, with the scalar and vector potentials taken to be equal and modeled using a modified Woods-Saxon potential-widely applicable across various fields of physics. We derive the radial wave equation in a Schrödinger-like form and analyze the corresponding effective potential of the system. This equation is solved using the confluent hypergeometric function, leading to a quartic equation for the relativistic energy spectrum. Due to the analytical complexity of this equation, we employ numerical methods to explore the energy spectrum. Our results show that the presence of the cosmic string significantly alters the quantum behavior of scalar particles, notably breaking the degeneracy of the energy levels. Furthermore, we examine the combined effects of the quantum flux and the modified Woods-Saxon potential on the energy spectrum and wave functions. The findings indicate that the cosmic string, the quantum flux and the potential play essential roles in shaping the energy eigenvalues and wave function, highlighting their importance in the quantum behavior of scalar particles in topologically nontrivial backgrounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum mechanics (QM) in curved space-time is a rich and intricate field that investigates how quantum phenomena are shaped by the curvature of space-time1. This interdisciplinary area bridges the fundamental principles of general relativity2 and quantum mechanics3, offering profound insights into the behavior of quantum particles in non-trivial geometries. While in flat space-time, quantum mechanics follows a well-defined framework governed by Minkowski geometry, the introduction of curvature imposes additional complexities that significantly alter the quantum dynamics. The presence of gravitational fields necessitates modifications to fundamental wave equations, ensuring consistency with curved space-time. For instance, in the case of spin-0 particles, the Klein-Gordon equation must be adapted by replacing partial derivatives with covariant derivatives, allowing for a proper description of particle motion in a gravitationally curved background4. In extreme scenarios, such as black hole physics, quantum effects in curved space-time give rise to striking phenomena like Hawking radiation, where quantum field fluctuations near an event horizon result in the emission of particles5,6,7. This phenomenon plays a crucial role in the ongoing effort to reconcile quantum mechanics with general relativity, offering insights into the behavior of quantum fields in strong gravitational environments. More broadly, the study of quantum mechanics in curved space-time serves as a stepping stone toward a deeper understanding of quantum gravity, illuminating the fundamental nature of space-time at the quantum level.

Among the most intriguing aspects of quantum mechanics in curved space-time is the role of topological defects, such as cosmic strings8,9,10,11. These one-dimensional structures, predicted by grand unified theories (GUTs), arise from phase transitions in the early universe and create localized curvature effects in space-time12,13,14,15,16. Cosmic strings exhibit a conical geometry that modifies the propagation of quantum wave functions, leading to phase shifts and alterations in energy spectra. Numerous authors have been studied the cosmic string in general relativity as well as in quantum mechanical systems (see, for example, Refs.17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35). This behavior shares a striking resemblance to the Aharonov-Bohm effect, where a charged particle moving around a magnetic flux acquires a measurable phase shift without experiencing a local force. The space-time around a cosmic string is described by the metric36,37,38:

where G is the Newtonian gravitational constant, and \(\mu\) represents the mass per unit length of the string. The conical structure introduces a deficit angle, \(\Delta \phi = 2\pi (1 - \alpha ) = 8\,\pi \, G \mu\), which alters particle trajectories, affects wave functions, and influences light propagation near the string. This geometric deformation leads to measurable gravitational lensing effects and modifies quantum interference patterns. Additionally, cosmic strings exhibit strong analogies with condensed matter systems, particularly dislocations in crystalline structures, where similar topological defects influence electron wave functions. This deep connection between high-energy physics and condensed matter theory underscores the universality of topological effects in nature36,37. Investigating quantum mechanics in curved space-time, particularly in the presence of topological defects, provides valuable insights into the fundamental interplay between quantum theory and gravitational effects, advancing our understanding of both quantum field theory and astrophysical phenomena.

In the weak-field approximation, the gravitational influence of a cosmic string is typically encapsulated in the metric39, which provides a more detailed understanding of how space-time curvature affects particle interactions and quantum fields40. When a quantum particle interacts with a cosmic string, the conical geometry of space-time alters the particle’s wave function, leading to unique phase shifts and modifications in its energy spectrum, effects that are distinct from those observed in flat space-time and directly arise from the curvature induced by the cosmic string41. This interaction serves as an excellent theoretical laboratory for exploring the intersection of quantum field theory and general relativity, offering valuable insights into how particles behave in non-trivial geometries and how the curvature of space-time influences quantum states. Beyond their role in fundamental physics, cosmic strings are also significant in cosmology, as they are expected to have formed during symmetry-breaking phase transitions in the early universe, making them potential candidates for explaining certain large-scale structures of the universe42. As such, these topological defects not only serve as intriguing objects for theoretical investigations but also provide crucial insights into the nature of space-time itself. The study of cosmic strings and their effects on quantum particles enhances our understanding of quantum fields in curved space-time, revealing how quantum phenomena manifest in extreme conditions such as those present in the early universe43,44. Additionally, these investigations contribute to a broader comprehension of how fundamental particles and fields behave in regions where the space-time fabric deviates significantly from flatness, thereby pushing the frontiers of both quantum mechanics and general relativity45,46. By studying the impact of cosmic strings on quantum systems, researchers can further explore the nature of quantum-gravitational interactions, potentially uncovering new theoretical frameworks that bridge the gap between quantum field theory and general relativity47,48,49,50.

The q-Woods-Saxon potential51 also known as the modified Woods-Saxon potential, represents an enhancement of the traditional Woods-Saxon potential52, which is used to describe approximately the forces applied on each nucleon, in the nuclear shell model for the structure of the nucleus. The traditional Woods-Saxon potential effectively models the attractive forces that bind nucleons within an atomic nucleus53,54, providing a simple yet powerful description of nuclear binding; however, it has some limitations in fitting experimental data with high precision, particularly in capturing the finer details of nuclear interactions55. To overcome these limitations, the q-Woods-Saxon potential introduces additional parameters that allow for more precise control over the depth, range, and shape of the potential well56,57, enabling a more accurate representation of the nuclear forces that govern the behavior of nucleons and making it possible to model quantum states and energy levels with greater precision58,59,60. One of the key advantages of the q-Woods-Saxon potential is its ability to provide a more detailed and flexible description of the internal structure of a nucleus; by incorporating adjustable parameters, this potential better captures the spatial distribution of bound states within a nucleus, influencing both the position and momentum distributions of nucleons. This more refined modeling is crucial for accurately predicting nuclear phenomena, such as the behavior of nuclei under different energy states, nuclear reactions, and decay processes, and, for instance, the q-Woods-Saxon potential provides a more precise description of the energy spectra and transition probabilities of nucleons within a nucleus. This, in turn, improves the accuracy of predictions related to reaction rates in processes like nuclear fusion and fission, which are fundamental to both energy production and the understanding of stellar processes61.

The q-Woods-Saxon potential offers enhanced capabilities that make it an indispensable tool for theoretical models striving to replicate experimental data with high fidelity. Unlike the traditional Woods-Saxon potential, it accounts for a wider range of physical effects, including higher-order interactions and intricate nuclear configurations, allowing for a more precise depiction of nuclear structure and dynamics62. This added flexibility makes it particularly useful in describing various nuclear phenomena, such as exotic isotopes and extreme nuclear conditions, further solidifying its importance in nuclear research. Moreover, the q-Woods-Saxon potential plays a pivotal role in nuclear astrophysics, where it aids in understanding the intricate forces at play within stellar environments, especially in the context of nucleosynthesis. By providing a more refined and comprehensive framework for nuclear interactions, it enhances models that describe element formation in stars, the energetic processes driving supernovae, and the complex matter interactions within neutron stars and other astrophysical events. Its ability to refine energy levels and reaction rates not only improves the accuracy of theoretical predictions but also opens new pathways for exploring fundamental nuclear forces and their broader implications for the universe. Moreover, the research presented in Ref.63 investigates a cosmological framework where a scalar field, influenced by a Woods-Saxon-like potential, plays a pivotal role in explaining the accelerated expansion of the universe. Quintessence, a dynamic scalar field, offers an intriguing alternative to the traditional cosmological constant in dark energy models. In this context, the Woods-Saxon potential-originally a tool in nuclear physics for describing the distribution of nucleons within an atomic nucleus-is repurposed to model the complex behavior of dark energy. This innovative approach provides a more flexible and evolving explanation for the universe’s acceleration, standing in stark contrast to the fixed nature of the cosmological constant in the widely accepted \(\Lambda\)CDM model. By leveraging the adaptability of the Woods-Saxon potential, this model introduces a dynamic framework that could potentially yield new insights into the nature of dark energy and the evolution of the cosmos.

Our main motivation in the current study is to investigate the effect of conical geometry of four-dimensional cosmic string space-time and a modified Woods-Saxon (WS) potential on spin-0 scalar particles, analyzing how these factors influence the particle dynamics. To achieve this, we solve the Klein-Gordon equation within the context of (3+1)-dimensional cosmic string space-time background, incorporating the modified WS potential. Additionally, our investigation includes the influence of Aharonov-Bohm (AB) flux on the quantum system, where the scalar quantum particles experiences zero magnetic field \(\vec {B}=\vec {\nabla }\times \vec {A}=\textbf{0}\). The radial equation is solved using special functions, like Gaussian hypergeometric function, while the angular solutions involved conical spherical harmonics that depend on the cosmic string parameter. Our findings demonstrate that the presence of the cosmic string, the deformation parameter on WS-potential, and the AB-flux collectively impact the behavior of scalar particles, leading to significant modifications in the results. Specifically, these factors alter the energy spectrum and wave functions of the particles and shifted the results compared Minkowski flat space.

While this study focus into the quantum dynamics of spin-0 scalar particles in a cosmic string space-time under a modified Woods-Saxon potential and quantum flux, several limitations should be noted. First, the background geometry is modeled by a static, axially symmetric space-time metric, where the cosmic string parameter \(\beta \in (0,1]\) encodes the angular deficit introduced by the cosmic string. This simplification effectively models a topological defect but neglects dynamical or non-static effects, such as cosmic string oscillations or back-reaction from the scalar field. Additionally, we assumes equal scalar and vector potentials, limiting the generality of the results. One may consider equal magnitude of scalar and vector potentials but opposite in sign. The fourth-order energy equation derived from the radial wave equation cannot be solved analytically, necessitating numerical computations for the energy spectrum, which may obscure certain physical insights. Future work may address these issues by exploring more general space-time backgrounds, varying scalar-vector couplings, or alternative numerical approaches that yield broader physical insights.

This paper is summarized as follows: In section Dynamics of spin-0 scalar particle: The Klein-Gordon Equation, we solve the Klein-Gordon equation in a cosmic string space-time with a modified WS-potential under the influence of quantum flux field. We tested the influence of the cosmic string parameter on the Woods-Saxon potential and showed how topological defects modify the effective potential experienced by scalar particles. The dependence of the potential on the string parameter introduces a geometric contribution that alters the particle dynamics, providing deeper insight into quantum behavior in curved spacetimes with topological features. In section Numerical Results and Discussions, we analyzed the energy eigenvalue and presented some numerical results. In section Conclusions, we present our conclusions. In this work, we use natural units, \(\hbar =c=G=1\).

Dynamics of spin-0 scalar particle: The klein-gordon equation

In flat Minkowski space-time, the spin-0 scalar particles are represented by the usual Klein-Gordon equation. This equation can be generalized to the curved space-time case. In order to determine the generalization of this relativistic wave equation, one may replace the ordinary derivatives by covariant derivative64,65,66 and the resultant wave equation is

where M is the rest mass of the particles, \(D_{\mu } \equiv (\partial _{\mu }-i\,e\,A_{\mu })\) with e is the electric charge, \(\partial _{\mu }\) is the partial derivative, \(A_{\mu }\) is the electromagnetic four-vector potential that is introduced through minimal coupling, and \(x^{\mu }\) is a four-vector. Here \(g^{\mu \nu }\) is the inverse of the metric tensor \(g_{\mu \nu }\) and \(g=\text{ det }(g_{\mu \nu })\) is the determinant.

An arbitrary scalar potential S(t, r) may be taken into account by making a modification in the mass term as \(M \rightarrow M+S(t,r)\)64,65. Substituting this modified mass term into (2) we obtain the following differential equation:

In this work, we focus on quantum motions of spin-0 scalar particles within the background of topological defect produced by a cosmic string in the presence of a static scalar (S(r)) and vector (V(r)) potentials. In the “Schwarzschild” coordinate \((t, r, \theta , \phi )\), the line-element describing a cosmic string space-time is represented by64,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74

where \(\beta\) is the cosmic string parameter which produces an angular deficit by an amount \(\Delta \phi =2\,\pi \,(1-\beta )\). In the limit \(\beta =1\), there is zero angular deficit and the space-time reduces to flat Minkowski space.

In this analysis, we consider the following electromagnetic potential64,74 (please see Eq. (33) in Ref.74 where \(a' \rightarrow \beta\) in our case):

where \(A_0=V\) is called temporal component of the potential, and \(\Phi _{AB}\) is the flux field. There is zero external magnetic field, \(\vec {B}=\vec {\nabla } \times \vec {A}=0\), experience by the quantum particles. However, the presence of flux field causes a shift in the eigenvalue solution of a quantum mechanical problem and we discuss it in the current study.

The total wave function can be written as \((x^{\mu }=(t, r, \theta , \phi ))\)

where E is the particle’s energy, \(Y(\theta , \phi )\) is the conical spherical harmonics (will explain later on) and \(\psi (r)\) is the radial wave function.

Therefore, the wave equation (3) using Eq. (5) and (6) can explicitly be written as follows:

where we have used the following relations65,75,76,77,78,79

Here \(Y^{m_{(\beta )}}_{\ell _{(\beta )}}(x)\) is called the conical spherical harmonics.

In this analysis, we consider equal scalar and temporal potential, that is \(S=V\). In that case, the above equation (7) becomes

Finally transforming to a new function via

into the Eq. (9), we finds the following second-order differential equation

The Woods-Saxon potential52 is frequently used to explain the neutron interactions with a heavy nucleus. The general form of Wood Saxon potential is as determined as

where \(V_0\) (having dimension of energy) represents the potential well depth, \(r_0\) is a measure of the nuclear size, and \(\delta\) determines the diffuseness of the nuclear surface (or is a length representing the surface thickness of the nucleus).

A modified form of this WS-potential is considered in80 given by

where \(r \in [0, \infty )\) is the distance between the target core and projectile. Setting \(\exp (-r_0/\delta )=\frac{1}{q}\), one can obtain the modified WS-potential as follows80,81:

Substituting potential (14) into the radial equation (11), one can write the differential equation as follows:

Equation (15) can not solved easily due to the presence of hyperbolic term. Therefore, we choose a suitable approximation into the centrifugal term \(\frac{1}{r^2}\) called Greene-Aldrich approximation82, where \(\frac{1}{r^2}=\frac{4\,d^2}{(e^{d\,r}-e^{-d\,r})^2}\). This approximation has been employed many authors in solving quantum mechanical problems under exponential potential of various kinds (see, for examples,83,84,85). Therefore, we can write the centrifugal term \(\frac{1}{r^2}\) in terms of hyperbolic function as follows:

Using approximation (16), thus, we can rewrite equation (15) as follows:

The above differential equation can be expressed as \(R''(r)+\left( \tilde{E}^2-V_\text {eff}(r)\right) \,R(r)=0\), where \(\tilde{E}^2=E^2-M^2\) and \(V_\text {eff}(r)\) is the effective potential of the system given by

From the expression given in Eq. (18), it is evident that the effective potential (\(V_\text {eff}\)) of the system depends on various factors. These include the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\), magnetic quantum flux \(\Phi\), arbitrary parameter q, strength of the potential \(V_0\), mass of quantum particles M, and changes with the quantum numbers \(\{\ell , m\}\), as well as the surface thickness \(\delta\).

In the limit \(\Phi =0\), corresponding to the absence of the magnetic flux, the effective potential given in Eq. (18) simplifies to:

Moreover, in the limit \(\Phi =0\) (absence of the magnetic flux) and \(\beta =1\) (absence of the cosmic string), the effective potential given in Eq. (18) simplifies to:

which is similar to the expression obtained in Ref.80.

Defining the following parameters

into the Eq. (17), we finds

We perform the following transforming

into the equation (22), we finds

Setting various parameters in Eq. (24) as follows:

Therefore, equation (24) can be rewritten as

The above equation is a second-order linear differential equation with three regular singular points located at \(z = 0\), \(z = 1\), and \(z = \infty\). To simplify this equation, we adopt an appropriate transformation for the radial function R(z) . The key idea is to absorb the dominant singular behaviors at \(z = 0\) and \(z = 1\) using a factorized ansatz. The justification is as follows: (i) Behavior near \(z = 0\): The differential equation contains a singular term of the form \(-\frac{\lambda '(\lambda ' + 1)}{4z},\) which governs the behavior of the solution near \(z = 0\). To eliminate this singularity and ensure regularity, we include a factor \(z^{\frac{\lambda '}{2} + \frac{1}{2}}\) in the ansatz, that is, \(R(z) \sim z^{\frac{\lambda '}{2} + \frac{1}{2}}\), (ii) Behavior near \(z = 1\): Similarly, the singular term near \(z = 1\) is \(-\frac{\zeta '(\zeta ' - 1)}{4(1 - z)}.\) To regularize the solution near this point, we include an additional factor \((1 - z)^{\frac{\zeta '}{2}}\) in the ansatz. This motivates the behavior near \(z=1\) of the form: \(R(z) \sim (1 - z)^{\frac{\zeta '}{2}}\). With these considerations, the substitution absorbs the singular behavior at both points \(z=0\, \& \, 1\), reducing the original equation to a more tractable form that can typically be solved in terms of hypergeometric functions. We therefore propose the following ansatz for the wave function:

where f(z) is expected to satisfy a regular second-order differential equation amenable to standard solution techniques.

Substituting Eq. (27) into the Eq. (26), we arrive at the following equation:

The above equation can be written in the following standard differential equation form:

where

The above second-order differential equation (29) is the well-known form of the Gaussian or ordinary hypergeometric differential equation86,87,88,89,90, and hence, the function f(z) is called the hypergeometric function \({}_2 F_1\) given by

Here \(\textrm{a}\), \(\textrm{b}\) and \(\textrm{c}\) are stated earlier the Pochhammer symbols \((x)_k\) are given as \((x)_k=\frac{\Gamma (x+k)}{\Gamma (x)}\), where \(\Gamma\) is the gamma function.

For bound states, we need polynomial solutions; f(z), in order to keep the wave function regular at the points \(z=0\) and \(z=1\). It is well-known in the literature that the hypergeometric function \({}_2 F_{1}(\textrm{a},\textrm{b},\textrm{c};z)\) becomes a finite degree polynomial of order n provided, we must have the following condition86,87,89:

where the requirement \(\textrm{b}=-n\) is precluded since \(\textrm{b}\) as given in Eq. (30) is a positive definite. This condition \(a=-n\) implies that the Pochhammer symbol \((a)_n\) will become zero for some term in the series expansion. This results in the series truncating at that point, and the function f(z) becomes a polynomial of degree n.

Therefore, simplification of the condition Eq. (32) gives us the following relation

It is worth noting that the original Klein-Gordon equation is derived from the relativistic energy-momentum relation \(E^2 = \vec {p}^{\,2}\, c^2 + m^2\, c^4\). This relation leads to both positive and negative solutions for the energy E, indicating that the Klein-Gordon equation admits both positive and negative energy eigenvalues. The existence of negative energy solutions posed a conceptual challenge in early quantum theory and ultimately motivated the development of quantum field theory (QFT), where these solutions are reinterpreted as corresponding to antiparticles.

The above equation (33) can be expressible in a polynomial form of order 4 given by \(\text {H}(E)=\text {c}_0+\text {c}_1\,E+\text {c}_2\,E^2+\text {c}_3\,E^3+\text {c}_4\,E^4\), where \(c_i\quad \forall \quad i \in [0,5]\) are the coefficients of various related with \(n, m, \Phi , \beta , q\) and \(V_0\). The real valued solution of this polynomial equation gives us the relativistic energy spectrum \(E=E_{n\,m\,\beta \,\Phi }\) of spin-0 scalar particles in cosmic string background. The exact real valued solution of the above polynomial equation is challenging. However, we presented numerical result of this Energy eigenvalue for different values of the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\), the magnetic flux \(\Phi\), the deformed parameter q in the next section 3.

The radial solution is given by

where \(\textrm{b}\) and \(\textrm{c}\) are given in Eq. (30) and \(\mathcal {N}\) is the normalization constant (see the note in Section 4). This normalization constant can be determined using the following relation

Note that the normalization constant in the integral above can be explicitly evaluated only under certain assumptions relating the parameter \(\textrm{c}\) of the hypergeometric function to the exponent of the weight function \((\cosh \left( \frac{r}{2\,\delta }\right) )^{\mathcal {Q}}\). Specifically, a closed-form expression exists when \(\textrm{c} = \mathcal {Q} + 1\), that is satisfied in the current analysis. In the absence of such a relation, the integral generally cannot be evaluated in closed form. In our case, the normalization constant is found to be a real and positive, provided that an appropriate constraint on the parameters \(\ell ,\,m,\,\beta\) and \(\Phi\) is imposed (see the note in Section Conclusions).

One can see that the radial wave function R(z) depends on various factors. These include the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\), the magnetic flux \(\Phi\), the deformed parameter q, and the changes with the quantum numbers \(\{n,m\}\).

The total wave function is therefore from Eq. (6) given by

and \(\mathcal {C}_{n\,m\,\beta \,\Phi }\) is the normalization constant.

Equation (31) can be written as

Since \(a=-n\), where \(n=0,1,2,...\), we find a few functions as follows:

and others are in the same way. It is worth noting that the values of \(\textrm{b}\) and \(\textrm{c}\) are not same for different values of n. This is because parameters \(\textrm{b}\) and \(\textrm{c}\) from Eq. (30) can be re-written using Eq. (21) as follows:

which are now changes with \(E_{n\,m\,\beta \,\Phi }\) for \(n=0,1,2,...\) and the condition \(M>E\) must holds good.

Now, we discuss few special cases of the relativistic energy eigenvalue given in Eq. (33).

-

The first case corresponds to zero flux field, \(\Phi _{AB}=0\). In that case, the relativistic energy eigenvalue given in Eq. (33) simplifies to:

$$\begin{aligned} E=\pm \,\sqrt{M^2-\frac{\left[ 2\,n+2\,\sqrt{\frac{1}{4}+2\,\delta ^2\,q\,V_0\,(E+M)}+\ell +\left( \frac{1}{\beta }-1\right) \,|m|+\frac{1}{2}\right] ^2}{4\,\delta ^2}}. \end{aligned}$$(40)The real valued solution of this polynomial equation (40) gives us the relativistic energy spectrum of spin-0 scalar particles without any flux field in a cosmic string space-time background under the effects of equal scalar and vector potential.

-

The second special case corresponds to the absence of the cosmic string effects (\(\beta =1\)) but nonzero flux field \(\Phi _{AB} \ne 0\). In that case, the relativistic energy eigenvalue given in Eq. (33) simplifies to:

$$\begin{aligned} E=\pm \,\sqrt{M^2-\frac{\left[ 2\,n+2\,\sqrt{\frac{1}{4}+2\,\delta ^2\,q\,V_0\,(E+M)}+\ell +|m-\Phi |-|m|+\frac{1}{2}\right] ^2}{4\,\delta ^2}}. \end{aligned}$$(41)The real valued solution of the polynomial equation (41) gives us the energy spectrum of spin-0 scalar particles in Minkowski space-time background with a magnetic flux field under the effects of equal scalar and vector potential.

-

The final case corresponds to the absence both the cosmic string effects (\(\beta =1\)) and the magnetic flux (\(\Phi _{AB} =0\)). In that case, the relativistic energy eigenvalue given in Eq. (33) simplifies to:

$$\begin{aligned} E=\pm \,\sqrt{M^2-\frac{\left[ 2\,n+2\,\sqrt{\frac{1}{4}+2\,\delta ^2\,q\,V_0\,(E+M)}+\ell +\frac{1}{2}\right] ^2}{4\,\delta ^2}}. \end{aligned}$$(42)The real valued solution of the polynomial equation (42) gives us the energy spectrum of spin-0 scalar particles in Minkowski flat space under the effects of equal scalar and vector potential, as discussed in80. Noted that the energy eigenvalue expression presented in Ref. 80 appears to be incorrect, stemming from a misapplication of the properties of the hypergeometric function \({}_2F_1(a', b', c'; z)\). Specifically, the derivation assumed that the hypergeometric function reduces to a polynomial of finite degree, which is only valid when either \(a'\) or \(b'\) is a non-positive integer. Since \(a'\) given in Eq. (32) in80 is positive, and thus, only \(b' = -n\) is valid. Thereby, simplification of the condition \(b' = -n\) will give us a correct expression of the energy eigenvalue. Without satisfying this condition, \({}_2F_1\) remains an infinite series and does not yield discrete quantized solutions. Consequently, the energy quantization condition derived under this incorrect assumption lacks mathematical justification, and the resulting eigenvalues do not correspond to physically admissible solutions of the Klein-Gordon equation.

By comparing equation (31) with equations (40)–(42), it becomes apparent that the presence of the flux field, denoted as \(\Phi _{AB}\), and the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\) lead to significant modifications in the relativistic energy expression E. These modifications shift the energy spectrum compared to the flat space scenario, where no flux field or cosmic string is present, under the influence of the modified Woods-Saxon potential. Specifically, the flux field \(\Phi _{AB}\) introduces additional complexities to the quantum system, influencing both the spatial distribution and the dynamics of the scalar particles, while the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\) alters the space-time geometry, which in turn modifies the behavior of the particles.

The modified Woods-Saxon potential V(r), which serves as a more accurate representation of the nuclear potential, plays a crucial role in determining the energy eigenvalues. The combination of this potential with the topological defect parameter \(\beta\) and the flux field \(\Phi _{AB}\) leads to a noticeable shift in the energy spectrum of spin-0 scalar particles, highlighting the profound impact that curvature, topological defects, and external fields have on the quantum properties of particles in such non-trivial geometries.

This shift in the energy eigenvalues, when compared to the Minkowski flat space case (as discussed in Ref.80), illustrates how the interactions between quantum fields, gravitational effects, and topological features such as cosmic strings profoundly influence the quantum states of particles. The influence of the modified Woods-Saxon potential, in conjunction with the cosmic string and flux field, modifies the energy levels, leading to distinct differences from those found in flat space.

Now, we discuss solution of the angular equation given in Eq. (8). Writing the conical spherical harmonics as follows:

Substituting Eq. (43) into the Eq. (8) and after separating the variables, we find

where \(m^2_{(\beta )}\) is the separation constant.

We focus into azimuthal equation which is as follows:

Let us consider a possible solution as

Substituting Eq. (46) into the Eq. (45) and after simplification, we find

The angular equation from Eq. (44) can be rewritten as

Transforming to a new variable via \(x=\cos \theta\) into the Eq. (48) yields:

which is the associated Legendre equation of degree \(\ell _{(\beta )}\) and order \(m_{(\beta )}\) and its solutions are well-known86,91. Therefore, \(\mathcal {A}(x)\) is the associated Legendre polynomials given by

The above polynomials has nonzero values provided we have the condition

Substituting \(m_{(\beta )}\) from Eq. (47), we find

Thus, it is evident that the presence of the cosmic string characterized by the parameter \(\beta\) as well as the magnetic flux \(\Phi\) shifts the magnetic quantum number \(m \rightarrow m_{(\beta )}\), as shown in Eq. (47). Consequently, the orbital quantum number changes to \(\ell \rightarrow \ell _{(\beta )}\). Notably, in the limit where \(\beta =1\), that is, without cosmic string and zero magnetic flux, \(\Phi =0\), we recover \(m_{(\beta )} \rightarrow m\) and \(\ell _{(\beta )} \rightarrow \ell\). This leads to \(\ell _{(\beta )}\,(\ell _{(\beta )}+1) \rightarrow \ell \,(\ell +1)\), which is a well-known result presented in many quantum mechanics textbooks. Therefore, the un-normalized conical spherical harmonics solutions are given by

Numerical results and discussions

Before presenting the numerical results and discussion, we note that throughout this manuscript, we adopt natural units by setting \(c = \hbar = G = 1\), so that all physical quantities become dimensionless.

As stated earlier, the effective potential \(V_\text {eff}\) of the quantum system given in Eq. (18) depends on the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\), the magnetic flux \(\Phi\), the deformed parameter q, and the changes with the magnetic quantum number m.

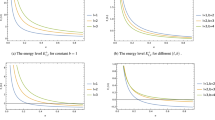

The behavior of the effective potential (18) with r for different values of \((\beta , \Phi )\). Here, \(V_0 = 0.1, \delta = 0.2, M = 1, n = 1, m = 1, E = 0.5, \ell =1, \text{ and }\, q=0.1\) in the natural units \(\hbar =1=c=G\).

The behavior of the effective potential (18) with r for different values of of the potential strength \(V_0\). Here, we set \(\delta = 0.2; M = 1; n = 1; m = 1; E= 0.5; \ell = 1; \beta = 0.9; \Phi = 0.5; q = 0.1\) in the natural units.

A comparison of the effective potential (18) with r in different scenario. Here, \(V_0 = 0.1, \delta = 0.2, M = 1, n = 1, m = 1, E = 0.5, \ell =1, \text{ and }\, q=0.1\) in the natural units \(\hbar =1=c=G\).

In Fig. 1b a , we present a graphical representation of the effective potential \(V_\text {eff}\) and examine its behavior for varying values of the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\), and the magnetic flux \(\Phi\), while maintaining the other system parameters constant at \(V_0 = 0.1\), \(\delta = 0.2\), \(M =1\), \(n=1\), \(m=1\), \(E=0.5\), \(q=0.1\), and \(\ell =1\). This Figure provides a comprehensive understanding of how each of these key parameters influences the shape and characteristics of the effective potential. By varying \(\beta\), the cosmic string parameter, we explore how the spacetime geometry affects the potential, while changing \(\Phi\) allows us to assess the impact of the magnetic flux on the system. The fixed parameters \(V_0\), \(\delta\), M, n, m, E, q, and \(\ell\) serve as a reference point, ensuring that the observed variations in the effective potential are primarily due to the changes in \(\beta\), and \(\Phi\). The resulting plots provide valuable insights into the interplay between these physical parameters and their collective impact on the effective potential, shedding light on the underlying dynamics of the system. This investigation not only deepens our understanding of how cosmic strings, and the magnetic flux field affect the system but also offers a clear picture of the potential landscape under different physical conditions. In Figure 2, we present a graphical representation of the effective potential \(V_\text {eff}\) showing its behavior for different values of the potential strength \(V_0\) keeping fixed other parameters \(\delta = 0.2,\, M = 1,\, n = 1,\, m = 1,\, E= 0.5,\, \ell = 1,\, \beta = 0.9,\, \Phi = 0.5,\, q = 0.1\) in the natural units.

In Fig. 3, we present a comparison of the effective potential under different scenarios: with and without the presence of both the cosmic string and the magnetic flux.

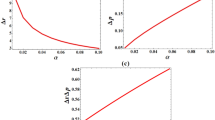

The radial wave function \(R_{n\,m\,\beta \,\Phi }\), as expressed in Eq. (34), depends on several parameters, including the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\), the magnetic flux \(\Phi\), parameter q, and changes with the quantum numbers n, \(\ell\) and m. In Fig. 4, we present the variation of the radial wave function R(z) as defined in Eq. (34) for different values of the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\), the magnetic flux \(\Phi\) and/or their combination, while keeping other parameters fixed at \(V_0 = 1\), \(\delta = 0.2\), \(M =1\), \(q = 1\), \(E =0.5\), and \(\ell = 1=m\). The choice of these fixed parameters ensures that the changes in the radial wave function are primarily due to the variations in the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\), the magnetic quantum number m, and the magnetic flux \(\Phi\), allowing us to isolate and study their individual effects. The results from this investigation demonstrate how the cosmic string and magnetic flux influence the radial distribution of the wave function, altering its behavior. Additionally, the deformation parameter q further complicates the structure of the wave function, and understanding this dependency is crucial for uncovering the underlying physics of the system. By varying these parameters systematically, we gain insights into how the geometry of space-time, the magnetic field, and quantum effects combine to shape the characteristics of the system. We summarize Fig. 4 as follows:

-

In Fig. 4 (a) and (b), the radial wave function R(z) is plotted for \(\Phi = 0.5\), illustrating the effect of the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\) on the particles’ dynamics for \(n=0\) and 1. The presence of a non-zero magnetic flux \(\Phi\) introduces additional complexities, including the influence of a topological defect, which modifies the wave function’s amplitude and structure.

-

In Fig. 4 (c) and (d), for \(\beta =0.9\), the radial wave function demonstrates how the magnetic flux \(\Phi\) affects the particle’s behavior for \(n=0\) and 1. As \(\Phi\) increases, the amplitude of the wave function decreases, indicating a reduction in the particle’s localization. This suggests that higher magnetic flux weakens the particle’s confinement, leading to a more delocalized state, which reflects the significant influence of the magnetic field on the quantum system.

-

In Fig. 4 (e) and (f), we show the combined effects of \(\beta\) and \(\Phi\) on the wave function for \(n=0\) and 1.

In Fig. 5, we present the variation of the radial wave function R(z) as defined in Eq. (34) for different values of the potential strength \(V_0\) keeping fixed other parameters \(\delta = 0.2,\, M = 1,\, E = 0.5,\, q = 1,\, \ell = 1,\, \beta =0.8,\, \Phi = 0.5,\, m = 1\) in the natural units. Panel (a) corresponds to the quantum number \(n=0\), while panel (b) for \(n=1\).

A comparison of the Radial wave function R(z) plotted as a function of z under different scenario: flat space \(\beta =1, \Phi =0\); cosmic string effects alone \(\beta \ne 1, \Phi =0\); and both the cosmic string and quantum flux effects \(\beta \ne 1, \Phi \ne 0\). Here, we set \(V = 1,\, \delta = 0.2,\, M = 1,\, E = 0.5,\, q = 1\).

Figure 6 presents a comparative analysis of the radial wave function R(z) for the ground (\(n = 0\)) and first excited (\(n = 1\)) states, illustrating the effects of the cosmic string and quantum flux. In both panels, three different scenarios are depicted for comparison. The dotted curve represents the reference case where both the cosmic string (\(\beta = 1\)) and the quantum flux (\(\Phi = 0\)) are absent. The dashed curve corresponds to the presence of the cosmic string alone (\(\beta \ne 1\)) with no quantum flux (\(\Phi = 0\)). The solid curve shows the scenario where both the cosmic string (\(\beta \ne 1\)) and quantum flux (\(\Phi \ne 0\)) are present. This figure demonstrates that the inclusion of both the cosmic string and quantum flux leads to an increase in the amplitude of the radial wave function, indicating enhanced localization and altered spatial structure of the quantum states due to the combined topological and electromagnetic effects.

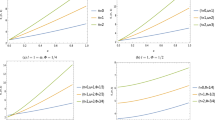

In Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4, we have presented numerical values of the energy eigenvalue E for different values of the topological parameter \(\alpha\), amount of magnetic flux \(\Phi\), and the deformed parameter q.

-

1.

Analysis of Energy Eigenvalues with Varying Cosmic String Parameter \(\beta\):

In Table 1, the energy eigenvalues \(E_{\pm }\) are presented for different values of the cosmic string \(\beta\), while keeping the potential strength \(V_0=0.1\), deformed parameter \(q=0.1\), screening parameter \(\delta =0.5\), rest mass of the charged particles \(M=5\), radial quantum number \(n=1\), orbital quantum number \(\ell =1\), magnetic quantum number \(m=1\), and the magnetic quantum flux \(\Phi =0.5\) constant. We observe that as the values of \(\beta\) increase, the positive values of the energy (\(E_{+}\)) also increase, while the negative values of the energy (\(E_{-}\)) decrease. Noted that the energy becomes imaginary values in the interval \(0<\beta < 0.4\).

-

2.

Influence of Magnetic Flux \(\Phi\) on Energy Eigenvalues:

In Table 2, the variation of the energy eigenvalues \(E_{\pm }\) with changes in the amount of magnetic flux \(\Phi\) is shown, with the other parameters held constant: potential strength \(V_0=0.1\), deformed parameter \(q=0.1\), screening parameter \(\delta =0.5\), rest mass of the charged particles \(M=5\), the radial quantum number \(n=1\), the orbital quantum number \(\ell =1\), the magnetic quantum number \(m=1\), and the cosmic string parameter \(\beta =0.9\). An increase in the quantum flux \(\Phi\) results in an increase in positive values of the energy (\(E_{+}\)), while the negative values of the energy (\(E_{-}\)) decrease.

-

3.

Impact of Deformed Parameter q on Energy Eigenvalues:

In Table 3, the energy eigenvalues E are calculated for varying values of the deformed parameter q. The other parameters remain fixed: potential strength \(V_0=0.1\), screening parameter \(\delta =0.5\), rest mass of the charged particles \(M=5\), radial quantum number \(n=1\), orbital quantum number \(\ell =1\), magnetic quantum number \(m=1\), global monopole parameter \(\alpha =0.9\), and amount of quantum flux \(\Phi =0.9\). An increase in q results in a decrease in the positive values of the energy (\(E_{+}\)), while the negative values of the energy (\(E_{-}\)) increases.

-

4.

Combined Effects of Cosmic String Parameter \(\beta\), Magnetic Flux \(\Phi\), and Deformed Parameter q:

Finally, Table 4 explores the combined effects of varying the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\), amount of magnetic flux \(\Phi\), and the deformed parameter q on the energy \(E_{\pm }\). The potential strength \(V_0=0.1\), rest mass of the charged particles \(M=5\), radial quantum number \(n=1\), orbital quantum number \(\ell =1\), and magnetic quantum number \(m=1\) are kept constant. The results show that increasing these parameters together leads to an increases in the positive values of the energy (\(E_{+}\)), while the negative values of the energy (\(E_{-}\)) decreases. Noted that the energy becomes imaginary values in the interval \(0<\beta < 0.4\).

Conclusions

In this work, we investigated the relativistic quantum dynamics of spin-0 scalar bosonic particles in the presence of a topological defect produced by a cosmic string space-time, subject to the influence of a modified Woods-Saxon potential and quantum flux field. By solving the Klein-Gordon equation in this curved background, we derived a fourth-degree polynomial equation for the relativistic energy eigenvalues, showing the significant roles played by the cosmic string parameter \(\beta\) and the magnetic flux \(\Phi _{AB}\). We also examined the limiting case corresponding to Minkowski space, where \(\beta = 1\) and \(\Phi _{AB} = 0\), recovering the standard form of the energy expression without topological or flux effects. Our numerical analysis demonstrated how variations in the parameters \(\beta\), \(\Phi _{AB}\), and the deformation parameter q modify the energy spectrum and quantization conditions. The numerical results of the relativistic energy spectrum, summarized in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 and the radial wave function plotted in Figures 4, 5, and 6 underscore the sensitivity of the system’s bound states to the presence of topological defects and quantum flux, even in the absence of a classical magnetic field. In particular, the flux induces nontrivial modifications to the energy levels, reflecting the topological nature of the interaction, while the cosmic string spacetime alters the effective geometry experienced by the particles. Also, these results contribute to a deeper understanding of how curved space-time geometries, topological structures, and external field effects govern the quantum behavior of particles. The study offers relevant insights for models of particle physics in the early universe and condensed matter analogs, such as graphene systems and quantum rings. As an outlook for future research, it would be valuable to extend the current analysis to include scattering states, allowing for a deeper investigation into phase shifts and resonant behavior under topological and flux influences. Additionally, testing the thermal and magnetic properties of the system could provide further insight into quantum statistical behaviors in curved backgrounds. Introducing uniform and mixed magnetic fields may help examine the interplay between classical and topological magnetic effects. Finally, applying this framework to model diatomic molecular systems could reveal how curvature and topological features influence vibrational and rotational spectra, opening avenues for quantum control in molecular and nanoscale systems.

NOTE: Using R(r) given in Eq. (34), one can determine the integral \(\int ^{\infty }_{0}\,|R(r)|^2\,dr\) as follows:

where \(\tilde{\alpha }=\frac{1}{2}+\ell +\frac{|m-\Phi |}{\beta }-|m|\) and we have used the orthogonality condition of the hypergeometric function given in86,87,88,89.

Therefore, the normalization constant is given by

which is real and positive provided we impose the constraint \(\left( \ell +\frac{|m-\Phi |}{\beta }-|m|\right) \in \mathbb {Z}_\text {odd}\). It is important to note that the parameters \(\ell \in \{0\,\pm \,1,\pm \,2,...,\},\, m \in \{0\,\pm \,1,\pm \,2,...\},\, 0< \beta <1\) and \(\Phi >1\,(\text{ or }\,\, \Phi <1)\) must be carefully chosen so that the constraint above is satisfied. As an illustrative example, take: \(\ell =1=m\), \(\Phi =(1-k\,\beta )<1\), \(k \in \mathbb {Z}^{+}_\text {odd}\), \(k < 1/\beta\). In this case, the constraint simplifies to: \(1+\frac{|1-\Phi |}{\beta }-1=k\), which clearly yields odd integer values for \(k=1,3,5,...\) . There are, in fact, numerous combinations of parameter values that satisfy the constraint and produce valid odd outputs. By appropriately tuning \(\ell ,\,m,\,\beta\) and \(\Phi\), one can generate a variety of such valid cases.

The normalized radial wave function \(\psi (r)\) is thus given by

Since both parameters \(\textrm{b}, \textrm{c}\) given in Eq. (39) depend on the energy eigenvalue \(E_{n,m,\beta ,\Phi }\), they are not constants but rather variables that vary with the quantum state \(\{n, m\}\). Consequently, the normalization constant \(|\mathcal {N}_{n,m,\beta ,\Phi }|\) must be determined individually for each specific quantum state, as it is directly related to the corresponding energy eigenvalue. Given this dependency, a graphical representation of the normalized radial functions \(\psi (r)\) given in Eq. (56) becomes a rather tedious and technically demanding task. Therefore, we have not included a figure for the normalized radial function \(\psi (r)\). Instead, in Figures 4 to 6, we have plotted the function R as a function of z, rather than in terms of r.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Audretsch, J., & V. De Sabbata, Quantum mechanics in curved space-time 230, Springer Science (2012).

Einstein, A. Die Grundlagen der allgemeinen. Ann. Phys. (Berlin) 49, 769 (1916).

Greiner, W. Quantum mechanics: an introduction, Springer Science (2011).

Fronsdal, C. Elementary particles in a curved space. II. Phys. Rev. D 10, 589 (1974).

Hawking, S. W. Black hole explosions?. Nature 248, 30 (1974).

Schwarzschild, K. On the gravitational field of a mass point according to Einstein’s theory. Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 35, 951 (2003).

Hawking, S. W. & Penrose, R. The singularities of gravitational collapse and cosmology. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 314, 529 (1970).

Brandenberger, R. H. Topological defects and structure formation. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 9, 2117 (1994).

Hindmarsh, M. B. & Kibble, T. W. B. Cosmic strings. Rep. Progr. Phys. 58, 477 (1995).

Hradil, Z. Quantum-state estimation. Phys. Rev. A 55, R1561 (1997).

Vilenkin, A. Cosmic strings and domain walls. Phys. Rep. 121, 263 (1985).

Ahmed, F. & Bouzenada, A. Quantum dynamics of spin-0 particles in a cosmological space-time. Nucl. Phys. B 1000, 116490 (2024).

Ahmed, F. & Bouzenada, A. Study of scalar particles through the Klein-Gordon equation under rainbow gravity effects in Bonnor–Melvin-Lambda space-time. Commun. Theor. Phys. 76(4), 045401 (2024).

Ahmed, A. & Bouzenada, A. Relativistic spin-0 Duffin-Kemmer-Petiau equation in Bonnor-Melvin-Lambda solution. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 39(05n06), 2450032 (2024).

Ahmed, F. & Bouzenada, A. Scalar fields in Bonnor-Melvin-Lambda universe with potential: a study of dynamics of spin-zero particles-antiparticles. Phys. Scr. 99, 065033 (2024).

Ahmed, F. & Bouzenada, A. PDM relativistic quantum oscillator in Einstein-Maxwell-Lambda space-time. Int. J. Geom. Meths. Mod. Phys. 22, 2450253 (2025).

Bezerra de Mello, E. R., Bezerra, V. B., Saharian, A. A. & Harutyunyan, H. H. Vacuum currents induced by a magnetic flux around a cosmic string with finite core. Phys. Rev. D 91, 064034 (2015).

Mota, H. F., Bezerra de Mello, E. R., Bessa, C. H. G. & Bezerra, V. B. Light-cone fluctuations in the cosmic string spacetime. Phys. Rev D 94, 024039 (2016).

Bezerra, V. B., Mota, H. F. & Muniz, C. R. Thermal Casimir effect in closed cosmological models with a cosmic string. Phys. Rev. D 89, 024015 (2014).

Cunha, M. S., Muniz, C. R., Christiansen, H. R. & Bezerra, V. B. Relativistic Landau levels in the rotating cosmic string spacetime. Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 512 (2016).

Bezerra de Mello, E. R., Bezerra, V. B., Saharian, A. A. & Tarloyan, A. S. Vacuum polarization induced by a cylindrical boundary in the cosmic string spacetime. Phys. Rev. D 74, 025017 (2006).

Muniz, C. R., Bezerra, V. B. & Cunha, M. S. Landau quantization in the spinning cosmic string spacetime. Ann. Phys. (NY) 350, 105 (2014).

Bezerra, V. B. & Ferreira, C. N. Gravitational field around a screwed superconducting cosmic string in scalar-tensor theories. Phys. Rev. D 65, 084030 (2002).

Bezerra, V. B., Cuesta, H. M. & Ferreira, C. N. Cosmic optical activity in the spacetime of a scalar-tensor screwed cosmic string. Phys. Rev. D 67, 084011 (2003).

Bezerra, V. B., Ferreira, C. N., Fonseca-Neto, J. B. & Sobreira, A. A. R. Gravitational field around a timelike current-carrying screwed cosmic string in scalar-tensor theories. Phys. Rev. D 68, 124020 (2003).

Bezerra, V. B., Lobo, I. P., Mota, H. F. & Muniz, C. R. Landau levels in the presence of a cosmic string in rainbow gravity. Ann. Phys. 401, 162 (2019).

Bezerra, V. B., Ferreira, C. N. & Marques, G. de A. Cosmic string configuration in a five dimensional Brans-Dicke theory. Phys. Rev. D 81, 024013 (2010).

Bezerra de Mello, E. R., Bezerra, V. B., Saharian, A. A. & Tarloyan, A. S. Fermionic vacuum polarization by a cylindrical boundary in the cosmic string spacetime. Phys. Rev. D 78, 105007 (2008).

dos Santos, W. O. & de Mello, E. B. Vacuum polarization induced by a cosmic string and a brane in AdS spacetime. Eur. Phys. J. C 83, 726 (2023).

Bezerra de Mello, E. R., Bezerra, V. B. & Grats, Y. V. Self-Action on a Current with Internal Structure in Cosmic String Space–Times. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 13, 1427 (1998).

de Mello, E. B., Bezerra, V. B. & Saharian, A. A. Electromagnetic Casimir densities induced by a conducting cylindrical shell in the cosmic string spacetime. Phys. Lett. B 645, 245 (2007).

Muniz, C. R. & Bezerra, V. B. Self-force on an electric dipole in the spacetime of a cosmic string. Ann. Phys. (NY) 340, 87 (2014).

Bezerra, V. B., Ferreira, C. N. & Cuesta, H. M. Supermassive screwed cosmic string in dilaton gravity. Class. Quantum Grav. 23, 4111 (2006).

Linet, B. Force on a charge in the space-time of a cosmic string. Phys. Rev. D 33, 1833 (1986).

Souradeep, T. & Sahni, V. Quantum effects near a point mass in (2+ 1)-Dimensional gravity. Phys. Rev. D 46, 1616 (1992).

Vilenkin, A. Gravitational field of vacuum domain walls and strings. Phys. Rev. D 23, 852 (1981).

Vilenkin, A. Cosmic strings. Phys. Rev. D 24, 2082 (1981).

Hiscock, W. A. Exact gravitational field of a string. Phys. Rev. D 31, 3288 (1985).

Verbiest, G. & Achucarro, A. High speed collision and reconnection of Abelian Higgs strings in the deep type-II regime. Phys. Rev. D 84, 105036 (2011).

Matzner, R. Interaction of U(1) cosmic strings: Numerical intercommutation. Comput. Phys. 2, 51 (1988).

Shellard, E. Cosmic string interactions. Nucl. Phys. B 283, 624 (1987).

Salmi, P. et al. Kinematic constraints on formation of bound states of cosmic strings: Field theoretical approach. Phys. Rev. D 77, 041701 (2008).

Jacobs, L. & Rebbi, C. Interaction energy of superconducting vortices. Phys. Rev. B 19, 4486 (1979).

Bogomolny, E. et al. Calculation of the monopole mass in gauge theory. Nucl. Phys. 24, 449 (1976).

Everett, A. E. Cosmic strings in unified gauge theories. Phys. Rev. D 24, 858 (1981).

Copeland, E., Kibble, T. & Steer, D. A. Collisions of strings with Y junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 021602 (2006).

Dvali, G. & Vilenkin, A. Formation and evolution of cosmic D strings. JCAP 0403, 010 (2004).

Bennett, D. P. & Bouchet, F. R. High-resolution simulations of cosmic-string evolution. I. Network evolution. Phys. Rev. D 41, 2408 (1990).

Vachaspati, T. & Vilenkin, A. Formation and evolution of cosmic strings. Phys. Rev. D 30, 2036 (1984).

Kibble, T. W. B. Topology of cosmic domains and strings. J. Phys. A 9, 1387 (1976).

Gönül, B. & Köksal, K. Solutions for a generalized Woods-Saxon potential. Phys. Scr. 76, 565 (2007).

Woods, R. D. & Saxon, D. S. Diffuse surface optical model for nucleon-nuclei scattering. Phys. Rev. 95, 577 (1954).

Romaniega, C., Gadella, M., Betan, R. M. Id & Nieto, L. M. An approximation to the Woods–Saxon potential based on a contact interaction. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 135, 372 (2020).

Lütfüoğlu, B. C. Comparative Effect of an Addition of a Surface Term to Woods-Saxon Potential on Thermodynamics of a Nucleon. Commun. Theor. Phys. 69, 23 (2018).

Freitas, A. D. S. et al. Woods-Saxon equivalent to a double folding potential. Braz. J. Phys. 46, 120 (2016).

Dudek, J., Nazarewicz, W. & Werner, T. Discussion of the improved parametrisation of the Woods-Saxon potential for deformed nuclei. Nucl. Phys. A 341, 253 (1980).

Ogloblin, A. A. et al. New measurement of the refractive, elastic 16O+12C scattering at 132, 170, 200, 230, and 260 MeV incident energies. Phys. Rev. C 62, 044601 (2000).

Bentez, J., Martinezy-Romero, R. P., Nunez-Yepez, H. N. & Salas-Brito, A. L. Solution and hidden supersymmetry of a Dirac oscillator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 1643 (1990).

Rozmej, P. & Arvieu, R. The Dirac oscillator. A relativistic version of the Jaynes-Cummings model. J. Phys. A 32, 5367 (1999).

Ginocchio, J. N. Relativistic harmonic oscillator with spin symmetry. Phys. Rev. C 69, 034318 (2004).

Moller, P., Nix, J. R., Myers, W. D. & Swiatecki, W. J. Nuclear ground-state masses and deformations. Atom. Data Nucl. Data Tabl. 59, 185 (1995).

Bengtsson, R., Dudek, J., Nazarewicz, W. & Olanders, P. A systematic comparison between the Nilsson and Woods-Saxon deformed shell model potentials. Phys. Scr. 39(2), 196 (1989).

Radhakrishnan, S., Nelleri, S. & Poonthottathil, N. Scalar field dominated cosmology with Woods-Saxon like potential. arXiv:2405.06750 [astro-ph.CO].

Medeiros, E. R. F. & Bezerra de Mello, E. R. Relativistic quantum dynamics of a charged particle in cosmic string spacetime in the presence of magnetic field and scalar potential. Eur. Phys. J. C 72, 2051 (2012).

de Oliveira, A. L. C. & Bezerra de Mello, E. R. Exact solutions of the Klein-Gordon equation in the presence of a dyon, magnetic flux and scalar potential in the spacetime of gravitational defects. Class. Quantum Gravity 23, 5249 (2006).

Birrell, N. & Davies, P. Quantum Fields in Curved Space, Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1984).

Vilenkin, A. Cosmic strings. Phys. Rev. D 24, 2082 (1981).

Vilenkin, A. Cosmic strings and domain walls. Phys. Rep. 121, 263 (1985).

Kibble, T. W. B. Topology of cosmic domains and strings. J. Phys. A Meth. Gen. 9, 1387 (1976).

Marques, G. de A. & Bezerra, V. B. Non-relativistic quantum systems on topological defects spacetimes. Class. Quantum Grav. 19, 985 (2002).

Marques, G. de A. & Bezerra, V. B. Hydrogen atom in the gravitational fields of topological defects. Phys. Rev. D 66, 105011 (2002).

Marques, G. de A., de Assis, J. G. & Bezerra, V. B. Some effects on quantum systems due to the gravitational field of a cosmic string. J. Math. Phys. 48, 112501 (2007).

Wang, Z., Long, Z., Long, C. & Teng, J. Exact solutions of the Schrödinger equation with a coulomb ring-shaped potential in the cosmic string spacetime. Phys. Scr. 90, 055201 (2015).

Boumali, A. & Aounallah, H. Exact Solutions of Scalar Bosons in the Presence of the Aharonov-Bohm and Coulomb Potentials in the Gravitational Field of Topological Defects. Adv. High Energy Phys. 2018, 1031763 (2018).

Kurbah, M. G. & Ahmed, F. Electromagnetic wave propagation in Eddington-inspired Born-Infeld gravity space-time with topological defects. Eur. Phys. J C 84, 903 (2024).

Kurbah, M. G. & Ahmed, F. Electromagnetic fields in topologically charged traversable wormholes. Eur. Phys. J C 84, 1205 (2024).

Kurbah, M. G. & Ahmed, F. Maxwell equations in Schwarzschild black hole with topological defects and the gravitational magnetoelectric effect. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 39, 2450172 (2024).

Kurbah, M. G. & Ahmed, F. Electromagnetic field tensor and maxwell’s equations in topological defect space-times. Indian-J Phys. 99, 1401 (2025).

Kurbah, M. G. & Ahmed, F. Maxwell equations in rotating cosmic string space-time and the gravitational magnetoelectric effect. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 40, 2550064 (2025).

Andaresta, W., Suparmi, A., Cari, C. & Permatahati, L. K. Study of Klein Gordon equation for modified Woods-Saxon potential using hypergeometric method. AIP Conf. Proc. 2296, 020132 (2020).

Ahmed, F. & Bouzenada, A. Relativistic quantum motions of spin-0 scalar particles in point-like defect under modified Woods-Saxon potential. Int. J. Geom. Meths. Mod. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219887825501762 (2025).

Greene, R. & Aldrich, C. Variational wave functions for a screened Coulomb potential. Phys. Rev. A 14, 2363 (1976).

Dong, S. H., Qiang, W. C., Sun, G. H. & Bezerra, V. Analytical approximations to the \(\ell\)-wave solutions of the Schrödinger equation with the Eckart potential. J. Phys. A: Math. Gen. 40, 10535 (2007).

Kumar, V., Bhardwaj, S. B., Singh, R. M. & Chand, F. On the solutions and applications of the generalised Cornell potential. Mol. Phys. 120, e2132185 (2022).

Kumar, V., Bhardwaj, S. B., Singh, R. M. & Chand, F. Energy eigenvalue spectra and applications of the sextic and the Coulomb perturbed potentials. Phys. Scr. 97, 055301 (2022).

Abramowitz, M., & Stegun, I. A. Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Dover Publications (1965).

Andrews, G. E., Askey, R. & Roy, R. Special functions, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications Vol. 71 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1999).

Koekoek, R., Lesky, P. A., & Swarttouw, R. F. Hypergeometric Orthogonal Polynomials and Their q-Analogues (Springer Monographs in Mathematics), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg (2010).

Bailey, W. N. Generalized Hypergeometric Series (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1935).

Spiegel, M. R., Lipschutz, S. & Liu, J. Schaum’s Outlines: Mathematical Handbook of Formulas and Tables (The McGraw-Hill Companies, USA, 2009).

Arfken, G. B., Weber, H. J. & Harris, F. E. Mathematical Methods for Physicists (Academic Press, Elsevier, 2012).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the anonymous referees for their valuable comments and helpful suggestions. F.A acknowledges the Inter University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA), Pune, India for granting visiting associateship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

1-Writing – review & editing, Supervisor, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization. 2-Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, F., Bouzenada, A. Effects of modified woods saxon potential on quantum dynamics of spin 0 scalar particle in a cosmic string spacetime. Sci Rep 15, 34177 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15338-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15338-5