Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative condition characterized by cognitive decline and associated metabolic disturbances, including altered amino acid profiles. This study investigated the effects of probiotic supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus HA-114 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175 on serum amino acid levels in adults with mild to moderate AD. In a 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 60 participants (aged 50–90 years) were assigned to three groups: L. rhamnosus (n = 20), B. longum (n = 20), or placebo (n = 20). Serum amino acids were analyzed using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (LC). Changes in total amino acids, Branched Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs), and aromatic amino acids (AAAs) were assessed as the primary outcomes. A significant interaction effect was found between time and group for serum amino acids. Compared to placebo, the B. longum group showed a significant increase in total amino acids (difference: 2132.67 µmol/L, 95% CI: 464.06–3801.28; p = 0.01), BCAAs (difference: 255.15 µmol/L, 95% CI: 53.01–457.30; p = 0.01), and AAAs (difference: 374.34 ng/ml, 95% CI: 57.45–691.23; p = 0.02). The L. rhamnosus group also showed a significant increase in BCAAs compared to placebo (difference: 206.08 µmol/L, 95% CI: 3.94–408.23; p = 0.04). The greatest improvements were consistently observed in the B. longum group across all primary outcome measures. Probiotic supplementation, particularly with B. longum, significantly improved serum amino acid profiles in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. These findings support the potential of specific probiotic strains to address metabolic imbalances in AD through gut-brain axis modulation. Trial Registration: IRCT number: 20210513051277N1 (2021-05-27).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the accumulation of amyloid-beta plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, leading to cognitive impairment and functional decline. It is the most common form of dementia, accounting for 60–80% of cases globally1. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 55 million people live with dementia worldwide, a number projected to reach 139 million by 20502. AD not only imposes a heavy emotional burden on patients and caregivers but also presents a significant economic challenge. In 2023, the global cost of dementia was estimated at over $1.3 trillion, a figure that is expected to double in the next two decades3. Complications associated with AD include progressive memory loss, behavioral disturbances, malnutrition, and increased susceptibility to infections, all of which contribute to high morbidity and mortality. It is the seventh leading cause of death globally and the fifth among individuals aged 65 and older4.

The etiology of AD is multifactorial and involves a complex interplay between genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors. In addition to well-established mechanisms such as amyloid-beta aggregation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and oxidative stress, growing evidence suggests that metabolic disturbances, particularly in amino acid metabolism, play a crucial role in disease progression5,6. Altered levels of serum amino acids—including branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and aromatic amino acids (AAAs)—have been observed in patients with AD and are associated with cognitive decline, mitochondrial dysfunction, and impaired neurotransmitter synthesis7,8. Amino acids serve as critical precursors for neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, norepinephrine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), all of which are implicated in cognitive and emotional regulation9.

In recent years, the gut-brain axis has emerged as a key player in AD pathophysiology, linking the intestinal microbiota to central nervous system function. Probiotics—defined as live microorganisms that confer health benefits when administered in adequate amounts—are increasingly being explored as therapeutic agents for neurological conditions, including AD10,11. Among the most studied probiotic strains are Bifidobacterium longum and Lactobacillus rhamnosus, both of which have demonstrated anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective, and metabolic effects12,13. Notably, these strains are capable of modulating the composition and function of the gut microbiota, enhancing gut barrier integrity, and influencing amino acid synthesis and absorption14. Preclinical and clinical studies have shown that supplementation with B. longum can improve cognitive performance, increase serotonin production, and normalize tryptophan metabolism in models of neurodegeneration10,15. Similarly, L. rhamnosus has been reported to impact GABAergic signaling, reduce anxiety-like behaviors, and support metabolic homeostasis16.

Despite promising findings, the literature on the effects of probiotic supplementation on serum amino acid profiles in AD patients remains limited and inconclusive. Some studies have reported significant increases in BCAAs and AAAs levels following probiotic intake, suggesting potential cognitive benefits17,18. Others, however, have found no significant metabolic changes, possibly due to differences in probiotic strains, dosages, treatment durations, and participant characteristics19,20. Furthermore, few studies have directly compared the effects of individual probiotic strains on amino acid profiles, making it difficult to determine which strains may offer the most therapeutic benefit. These inconsistencies highlight the need for well-controlled, strain-specific clinical trials to clarify the metabolic and neurochemical effects of probiotics in AD.

To address these gaps, this study investigates the effects of two specific probiotic strains—Lactobacillus rhamnosus HA-114 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175—on serum amino acid concentrations in adults with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease.

Materials and methods

Participants

This study was a 12-week, placebo-controlled, double blind, randomized trial that performed on sixty patients with the mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease at four neurological clinics under the supervision of the Tehran University of Medical Science (TUMS), Iran. The trial was done according to the Helsinki Declaration of 197521, also approved by the ethics committee of TUMS (IR.TUMS.MEDICINE.REC.1400.334) and registered on the Iranian Website for Registration of Clinical Trials IRCT (IRCT20210513051277N1; 2021-05-27). All of the participants were assured that they could withdraw from the trial at any time after being advised of the study’s advantages and hazards. We obtained informed consent in writing from all participants or their caregivers. The intervention began in October 2021 and concluded with the final observation in May 2022. The diagnosis of AD was based on the criteria outlined by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke (NINCDS) in partnership with the Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA)5 as well as the recommendations from the National Institute on Aging Alzheimer’s Association22. Additionally, MRI scans are utilized to assess hippocampal volume. Patients must have mild or moderate AD according to the Functional Assessment Staging Tool (FAST)23.

Sixty adults aged 50 to 90 years old with mild and moderate Alzheimer’s disease took part in this clinical trial. They were assigned to three groups (one group received L. rhamnosus, the other one received B. longum and the last one took a placebo). Ages 50–90 years, oral medication tolerance, and mild or moderate AD were the inclusion criteria. The list of exclusion criteria includes probiotic allergy, unwillingness to comply with study instructions, dietary changes that are substantial, inflammatory conditions that require extended (more than two weeks) use of anti-inflammatory medications, current use of antibiotics, pre- or probiotic products, or multivitamin and mineral supplements, the existence of any infections or diseases such as COVID-19, changes in medication during the study period, and participation in any other clinical trials. Participants may continue receiving any pharmaceutical treatments prescribed by their physician as long as they are taken concurrently.

Randomization and blinding

Stratified permute block randomization was performed and the random number was stratified by age and sex using www.randomization.com, Randomization was conducted in six blocks, with each block randomly assigning patients to one of three study groups (1:1:1 ratio) labeled as A, B, or C. the intervention consisted of participants being randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio, ensuring equal distribution of participants across groups. Product provider concealed the allocation sequence and blinding was maintained for participants, caregivers, investigators, and data analysts.

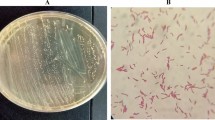

Interventions

Participants who met the requirements were randomly assigned to receive either L. rhamnosus, B. longum (109 CFU dosage), or a placebo capsule (composed of xylitol, maltodextrin, and malic acid). Two capsules were given to each patient daily after lunch and dinner by the caregivers throughout the study period. The supplements, which were supplied by Lallemand Company in Canada (Product Code: HA-114, Batch No: LHS-HA114-2021-01, Bifidobacterium longum R0175 – Product Code: R0175, Batch No: LHS-R0175-2021-02), looked and tasted the same. Caregivers kept track of compliance, considering consumption below 80% as non-compliant.

Eligible participants received one of two interventions [a probiotic capsule containing L. rhamnosus (each capsule containing 109 CFU of probiotic) or a probiotic capsule containing B. longum (each capsule containing 109 CFU of probiotic) twice daily] or in a 1:1 ratio the placebo (one capsule twice daily with xylitol, maltodextrin and malic acid). Color, taste, smell, and size of all the supplements were comparable, according to Lallemand Company in Canada. Two capsules per day, one after lunch and one after dinner, were given to patients by their caregivers, who were told to store the supplements in the refrigerator. Each month, the caregivers received their supply of nutritional supplements. Reminders to take supplements on a daily basis were sent to caregivers. Caregivers were asked to return the medication box, and consuming less than 80% of the supplement at the end of each month was considered noncompliant.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the change in serum amino acid profiles before and after the 12-week probiotic supplementation. Secondary outcomes included weight, BMI, food intake and physical activity. We also assessed cognitive function using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) test in these patients and have published a separate report24.

The height and weight of the patients were evaluated before and after the intervention. Anthropometric measurements were performed according to the method provided by the World Health Organization. Seca Clara 803 digital palm scale with accuracy of 0.01 gram was used for weighing. Height was measured using a Seca stadiometer without shoes with a sensitivity of 0.1 cm (Seca, Germany). The body mass index of people was also obtained using the relevant formula (BMI= (weight (kg)/height (m)2.

The information about the food plan of the subjects was collected through the food record questionnaire before the beginning and at the end of the study and by the interview method. Food records were used in all three groups before and after the intervention to evaluate the status of food intake for 3 non-consecutive days (two regular days and one holiday) in weeks 0 and 12. Then, the listed amounts of each food were converted to grams using the home scale guide and analyzed by Nutritionist 4 (NUT4) software modified for Iranian foods.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (LC) was used to measure the concentrations of free amino acids in serum. Following an overnight fast, a venous blood sample was drawn in the morning between the hours of 6:00 and 10:00. After being collected, samples were placed in ice and processed in no more than an hour. We used evacuated tubes containing potassium EDTA for plasma collection and empty plastic tubes for collecting serum. The fluid that was left behind after centrifugation at 3000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C was carefully removed. This process aids in preventing platelets and leukocytes—components high in taurine—from contaminating the supernatant fluid. The serum Amino Acids concentrations were measured using the LC 1200 series. Among the various chromatography technologies, high-performance pumps for supplying solvent at a steady flow rate and columns—devices made specifically for molecular separation—are some of these essential parts of chromatographs. As related technologies advanced, the system commonly referred to as LC. Ultra High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC), which has the ability to analyze data quickly, is also growing in popularity these days7.

Statistical methods

Data were analyzed using SPSS version 26 (SPSS version 26; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Shapiro-Wilk test and Q-Q plot were used to check the normality of data distribution. One-way ANOVA was used for quantitative variables and χ2 tests for qualitative variables. Given the repeated-measures design of this study, with data collected at both baseline and 12 weeks, a Linear Mixed Model (LMM) was employed to assess the effects of probiotic supplementation on serum amino acid levels over time. LMM was selected due to its capacity to account for within-subject correlations by incorporating random effects, its robustness in handling missing data without requiring imputation, and its ability to model group differences across time while adjusting for baseline variability.

To evaluate the intervention effects, a structured hypothesis-testing approach was implemented. First, the overall model significance was assessed using likelihood ratio tests (LRT) to compare models with and without the interaction terms. The null hypothesis (H₀) posited that there would be no differences in serum amino acid levels between the groups over time, while the alternative hypothesis (H₁) proposed that significant differences would be observed across groups during the intervention period. Following this, fixed effects were examined to determine the specific contributions of time, group, and their interaction. The time effect assessed whether serum amino acid levels changed irrespective of the intervention group. The group effect evaluated whether baseline differences existed among the three groups. Most importantly, the time-by-group interaction effect tested whether changes in serum amino acids differed significantly depending on the probiotic strain administered.

To further explore between-group differences, post-hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using Bonferroni correction to control for multiple testing. Adjusted p-values were calculated for comparisons between the placebo group and the L. rhamnosus group, the placebo group and the B. longum group, and between the two probiotic groups themselves.

All statistical analyses were two-tailed, with significance set at p < 0.05. Alongside p-values, effect sizes and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the magnitude and precision of the observed effects.

Results

Sixty patients were enrolled in the trial and randomly assigned to three groups: Placebo (n = 20), L. rhamnosus (n = 20), and B. longum (n = 20). All randomized participants completed the 12-week intervention and were included in the final analysis. There were no losses to follow-up or exclusions after randomization, indicating a high level of adherence and compliance across the study arms. This complete follow-up strengthens the internal validity of the trial and suggests that the findings were not significantly affected by participant dropout or attrition (Fig. 1). Baseline clinical and demographic characteristics were comparable across groups. No significant differences were observed in age, gender, and education level, type of Alzheimer’s disease, weight, and BMI at baseline (Table 1).

No serious side effects were reported. Mean age was 63.3 ± 5.45 years (placebo), 68.65 ± 8.62 years (L. rhamnosus), and 71.60 ± 6.97 years (B. longum). Gender distribution was equal, with 33.3% females and 66.7% males in each group. Majority of participants were illiterate, with a higher percentage in the B. longum group. The mean baseline weight and BMI were similar across groups, and end-of-trial weights and BMIs showed no significant changes.

Changes in energy, protein, fat, and carbohydrate, PUFA, MUFA, SFA, and cholesterol intake at the beginning and end of the study are presented in Table 2. LMM test showed no significant differences between groups at the end of the study (PTime×Group > 0.05).

Table 3 summarizes the changes in serum amino acid levels over 12 weeks across placebo, L. rhamnosus, and B. longum groups. While the placebo group showed minimal or declining amino acid levels, both probiotic groups demonstrated increases, with the most significant improvements observed in the B. longum group. Notably, BCAAs and AAAs increased substantially following B. longum supplementation.

Table 4 presented the effect of probiotic on amino acid levels over 12 weeks. The LMM test was used to compare the average values at the end of the study across the groups. A significant increase in total amino acids was observed (PTime × Group = 0.04). Post hoc comparisons indicated that B. longum (I2) led to a significantly greater increase compared to the placebo group (difference: 2132.67, 95% CI: 464.06 to 3801.28; P = 0.01) and L. rhamnosus (I1) (difference: 1454.37, 95% CI: -226.31 to 3135.07; P = 0.08). There was no significant difference between the two intervention groups (difference: -678.29, 95% CI: -678.29 to 1002.39; P = 0.42) (Table 4; Fig. 2).

A significant increase in BCAAs was observed by the end of the trial (PTime × Group = 0.03). Post hoc comparisons showed a significant increase in both the L. rhamnosus group (difference: 206.08, 95% CI: 3.94 to 408.23; P = 0.04) and the B. longum group (difference: 255.15, 95% CI: 53.01 to 457.30; P = 0.01) compared to the placebo group. No significant difference was found between the two treatment groups (difference: -49.07, 95% CI: -251.21 to 153.07; P = 0.62) (Table 4; Fig. 3). The probiotic supplements showed a marginally significantly change in the levels of AAAs after 12 weeks (PTime × Group = 0.05). However, a significant increase was noted in the B. longum group compared to the placebo (difference: 374.34, 95% CI: 57.45 to 691.23; P = 0.02) and the L. rhamnosus group (difference: 303.12, 95% CI: -13.77 to 620.01; P = 0.06). There was no significant difference between the two intervention groups (difference: 0.13, 95% CI: -0.37 to 0.64; P = 0.6) (Table 4; Fig. 4).

Although this study focused on amino acid metabolic profiles, cognitive function was assessed using the MMSE at baseline and after 12 weeks, with results reported in a separate publication24. No cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers were collected in this study.

Discussion

The present randomized controlled trial demonstrated that 12 weeks of probiotic supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus HA-114 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175 strains led to significant increases in serum levels of total amino acids, BCAAs, and AAAs in adults with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease compared to placebo. These findings align with previous research suggesting a link between altered amino acid metabolism and AD pathogenesis, as well as the potential for probiotics to modulate amino acid profiles.

Several studies have reported lower circulating levels of amino acids such as tryptophan, phenylalanine, tyrosine, methionine, and branched-chain amino acids in AD patients compared to healthy controls8,18,25. The decreased availability of these amino acids, which serve as precursors for neurotransmitter synthesis, may contribute to neuronal dysfunction and cognitive impairment in AD6. Our results indicate that probiotic supplementation, particularly with the B. longum strain, can significantly increase serum levels of BCAAs and AAAs in AD patients, potentially ameliorating deficits in these key amino acid classes.

The observed increase in BCAAs with probiotic treatment is noteworthy, as reduced BCAA levels have been associated with AD-related pathology and cognitive deficits in both human and animal studies8,26. BCAAs play crucial roles in protein synthesis, energy metabolism, and neurotransmitter production, and their depletion may contribute to synaptic dysfunction and neurodegeneration in AD27. Our finding that both L. rhamnosus and B. longum strains significantly elevated BCAAs levels compared to placebo suggests a potential mechanism by which these probiotics could exert neuroprotective effects in AD17.

Furthermore, the significant increase in AAAs observed in the B. longum group is promising, as these amino acids are precursors for the synthesis of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin – neurotransmitters implicated in cognitive function and emotional regulation9. Decreased levels of aromatic amino acids have been reported in AD patients and associated with cognitive decline28. Thus, the ability of B. longum to AAAs levels may help mitigate neurotransmitter deficiencies and support cognitive function in AD.

Our results are consistent with previous preclinical studies demonstrating the potential of probiotic supplementation to modulate amino acid metabolism and improve cognitive outcomes in AD mouse models. For instance, Aura et al. (2020) reported that probiotic treatment in the AppNL-G-F mouse model of AD increased brain levels of BCAAs and AAAs, accompanied by improved cognitive performance15. Similarly, Bonfili et al. showed that probiotic intervention in AD mice altered amino acid profiles and reduced AD-related pathology, including amyloid-beta deposition and neuroinflammation10.

The observed changes in serum amino acid profiles, particularly the increase in BCAAs and AAAs, may have implications for AD pathology. BCAAs are essential for protein synthesis and mitochondrial function and may support neuronal energy metabolism, potentially alleviating some AD-related deficits6,9. Additionally, increased levels of AAAs can enhance the synthesis of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin, which are often depleted in AD patients9,28. While this study did not directly measure AD-specific biomarkers such as CSF Aβ42 or tau proteins, the metabolic shifts observed here suggest potential avenues for future research exploring the link between amino acid metabolism and AD progression. Since the exact mechanisms underlying why B. longum Outperformed L. rhamnosus in AD remain to be elucidated, several potential pathways have been proposed: The superior performance of B. longum may be attributed to its greater ability to modulate microbiota composition and stimulate amino acid biosynthesis. Bifidobacterium species are known to colonize the human gut early in life and have demonstrated strong capabilities in promoting BCAA synthesis, essential for muscle metabolism, neurotransmitter production, and neuroprotection14. Moreover, B. longum strains are potent modulators of the gut-brain axis, enhancing serotonergic and dopaminergic pathways by influencing tryptophan metabolism10. This may explain the strain’s effect on increasing precursors for key neurotransmitters involved in cognition. In contrast, L. rhamnosus predominantly modulates the GABAergic system, which plays a more direct role in anxiety and stress regulation rather than amino acid biosynthesis11.

Additionally, B. longum R0175 has been shown to promote the growth of butyrate-producing bacteria, which improve intestinal barrier function and facilitate amino acid absorption12. Restoration of the gut microbial ecosystem in AD patients, who often exhibit microbial dysbiosis, may further enhance the efficacy of B. longum by optimizing amino acid transport and utilization29. These effects are particularly relevant for AD, where altered amino acid metabolism and compromised gut-brain communication contribute to neurodegeneration.

The increase in BCAAs observed in the B. longum group supports the hypothesis that this strain facilitates enhanced protein metabolism and may serve neuroprotective roles. BCAAs are integral precursors for neurotransmitters such as glutamate and GABA and are involved in mitochondrial energy production and immune modulation6,9,30. Furthermore, increased levels of AAAs such as phenylalanine and tyrosine suggest upregulation of catecholamine biosynthesis pathways, potentially supporting improved mood and cognitive resilience17,27.

One notable metabolic pathway influenced by probiotic intervention is the tryptophan-kynurenine-serotonin pathway. Tryptophan, an essential amino acid, is diverted through inflammatory mechanisms in AD toward neurotoxic kynurenine derivatives, leading to reduced serotonin availability. By modulating gut microbiota composition, B. longum may redirect tryptophan metabolism toward serotonin synthesis, contributing to better neurological outcomes9,10. This mechanistic insight provides a compelling rationale for the observed increase in aromatic amino acids and their potential link to improved brain function.

Moreover, chronic systemic inflammation in AD is known to dysregulate amino acid metabolism. Probiotic supplementation may mitigate this by restoring intestinal homeostasis and reducing inflammatory cytokines, thereby stabilizing neurotransmitter precursors in circulation13. The influence of probiotics on specific microbial populations also deserves mention. Several studies have shown that probiotic supplementation increases the abundance of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus while suppressing pro-inflammatory genera such as Escherichia and Clostridium20,31. These microbial shifts are associated with improved metabolic flexibility, better nutrient absorption, and modulation of the central nervous system through microbial metabolites and signaling molecules.

This randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial has several strengths, including its rigorous design, the use of two different probiotic strains, and the comprehensive assessment of serum amino acid profiles using advanced analytical techniques like LC. The relatively large sample size of 60 participants with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease also enhances the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. However, certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, the study duration of 12 weeks may not be sufficient to evaluate the long-term effects of probiotic supplementation on amino acid levels and disease progression. Additionally, the study population was limited to a specific geographic region, and the results may not be directly applicable to other populations with different dietary patterns or gut microbiome compositions. Furthermore, the study did not assess the potential mechanisms by which probiotics modulate amino acid metabolism or the cognitive and functional outcomes in Alzheimer’s patients, which could be valuable areas for future research.

Conclusion and future directions

B. longum demonstrated greater efficacy in increasing serum BCAAs and AAAs, possibly due to its stronger effects on gut microbiota modulation and neurotransmitter synthesis. The study highlights the importance of strain-specific selection in probiotic interventions for AD. Future research should integrate KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway analysis to explore metabolic pathways linked to probiotic effects and assess long-term cognitive outcomes.

These findings suggest that probiotic supplementation is a promising therapeutic strategy for managing metabolic imbalances in AD, though further research is needed to elucidate its full clinical impact.

Data availability

All the data produced or examined during the research are included in this article. For additional information, please contact the corresponding author.

References

2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dementia 19, 1598–1695. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.13016 (2023).

Organization, W. H. A Blueprint for Dementia Research (World Health Organization, 2022).

Wimo, A. et al. The worldwide costs of dementia 2015 and comparisons with 2010. Alzheimer’s Dement. 13, 1–7 (2017).

Nichols, E. et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Public. Health. 7, e105–e125 (2022).

Corso, G. et al. Serum amino acid profiles in normal subjects and in patients with or at risk of alzheimer dementia. Dement. Geriatric Cogn. Disorders Extra. 7, 143–159 (2017).

Polis, B. & Samson, A. O. Role of the metabolism of branched-chain amino acids in the development of alzheimer’s disease and other metabolic disorders. Neural Regeneration Res. 15, 1460–1470. https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.274328 (2020).

Gałęzowska, G., Ratajczyk, J. & Wolska, L. Determination of amino acids in human biological fluids by high-performance liquid chromatography: critical review. Amino Acids. 53, 993–1009 (2021).

Siddik, M. A. B. et al. Branched-chain amino acids are linked with alzheimer’s disease-related pathology and cognitive deficits. Cells 11, 3523 (2022).

Fukuwatari, T. Possibility of amino acid treatment to prevent the psychiatric disorders via modulation of the production of Tryptophan metabolite kynurenic acid. Nutrients 12, 1403 (2020).

Bonfili, L. et al. Microbiota modulation as preventative and therapeutic approach in alzheimer’s disease. FEBS J. 288, 2836–2855 (2021).

Dinan, T. G. & Cryan, J. F. The microbiome-gut-brain axis in health and disease. Gastroenterol. Clin. 46, 77–89 (2017).

Leblhuber, F., Steiner, K., Schuetz, B., Fuchs, D. & Gostner, J. M. Probiotic supplementation in patients with alzheimer’s dementia-an explorative intervention study. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 15, 1106–1113 (2018).

Naomi, R. et al. Probiotics for alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. Nutrients 14, 20 (2021).

Neis, E. P., Dejong, C. H. & Rensen, S. S. The role of microbial amino acid metabolism in host metabolism. Nutrients 7, 2930–2946. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu7042930 (2015).

Kaur, H. et al. Effects of probiotic supplementation on short chain fatty acids in the AppNL-G-F mouse model of alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD. 76, 1083–1102. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-200436 (2020).

Messaoudi, M. et al. Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects. Br. J. Nutr. 105, 755–764 (2011).

Chu, C. et al. Lactobacillus plantarum CCFM405 against rotenone-induced parkinson’s disease mice via regulating gut microbiota and branched-chain amino acids biosynthesis. Nutrients 15, 1737 (2023).

Ghosh, D. In Nutraceuticals in Brain Health and Beyond3–13 (Elsevier, 2021).

Altomare, D. et al. Plasma biomarkers for alzheimer’s disease: a field-test in a memory clinic. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 94, 420–427 (2023).

Ma, T. et al. Targeting gut microbiota and metabolism as the major probiotic mechanism - An evidence-based review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 138, 178–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tifs.2023.06.013 (2023).

Williams, J. R. The declaration of Helsinki and public health. Bull. World Health Organ. 86, 650–652 (2008).

Cummings, J. The National Institute on Aging—Alzheimer’s association framework on alzheimer’s disease: application to clinical trials. Alzheimer’s Dement. 15, 172–178 (2019).

Sclan, S. G. & Reisberg, B. Functional assessment staging (FAST) in alzheimer’s disease: reliability, validity, and ordinality. Int. Psychogeriatr. 4, 55–69 (1992).

Akhgarjand, C., Vahabi, Z., Shab-Bidar, S., Etesam, F. & Djafarian, K. Effects of probiotic supplements on cognition, anxiety, and physical activity in subjects with mild and moderate alzheimer’s disease: A randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 1032494 (2022).

Latmiral, L. & Armata, F. Berry-Hannay relation in nonlinear optomechanics. Sci. Rep. 10, 2264 (2020).

Le Couteur, D. G. et al. Branched chain amino acids, aging and age-related health. Ageing Res. Rev. 64, 101198 (2020).

Yoo, H. S., Shanmugalingam, U. & Smith, P. D. Potential roles of branched-chain amino acids in neurodegeneration. Nutrition 103, 111762 (2022).

Griffin, J. W. & Bradshaw, P. C. Amino Acid Catabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain: Friend or Foe? Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 5472792. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5472792 (2017).

Tiffany, C. R. & Bäumler, A. J. Dysbiosis: from fiction to function. Am. J. Physiology-Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. 317, G602–G608 (2019).

González-Domínguez, R., García-Barrera, T. & Gómez-Ariza, J. L. Metabolite profiling for the identification of altered metabolic pathways in alzheimer’s disease. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 107, 75–81 (2015).

Clapp, M. et al. Gut microbiota’s effect on mental health: the gut-brain axis. Clin. Pract. 7, 987. https://doi.org/10.4081/cp.2017.987 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from Tehran University of Medical Science. The authors appreciate all participants and the staff of Ziaeeian, Roozbeh and shariatic Hospital.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KD takes responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the research. NJ and CA were responsible for composing the manuscript, while SSB and CA gathered the data. ZV and HKH reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jouni, N., Akhgarjand, C., Vahabi, Z. et al. Strain specific effects of probiotic supplementation on serum amino acid profiles in Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 29924 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15355-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15355-4

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Protective effects of Parabacteroides distasonis against high-fat diet-induced brain injury in mice

npj Science of Food (2025)