Abstract

The effect of nighttime dosing versus daytime dosing of mirabegron is undetermined. Thus, this study aimed to clarify the effect of nighttime versus daytime mirabegron dosing. Between August 2017 and August 2023, all women with overactive bladder syndrome were randomly assigned to receive mirabegron 25 mg once with nighttime or daytime dosing for 12 weeks. A total of 109 women were enrolled. Fifty-two patients were in the daytime dosing group, and 57 patients were in the nighttime dosing group. Nocturia episodes improved in the nighttime group (5.65 ± 3.71 at baseline versus 4.26 ± 2.60 at 4 weeks, p = 0.019), but not the daytime group. In addition, after 4 weeks of treatment, the nighttime dosing group had a greater benefit in the decrease in urgency episodes at 06:00–12:00 (change: − 2.1 ± 3.7 versus 0.1 ± 2.4, p = 0.003), 18:00–24:00 (change: − 1.4 ± 3.0 versus 0.4 ± 2.7, p = 0.01) and all day (change: − 6.4 ± 10.8 versus 0.1 ± 8.5, p = 0.005), compared to daytime dosing. However, the daytime dosing group had a significant improvement in emotions (change: − 17 ± 25 versus − 6 ± 19, p = 0.006), compared to nighttime dosing. After 12 weeks of treatment, despite the significant improvement in overactive bladder symptoms in both groups, there were no differences between groups. In addition, young age (coefficient = 0.065, p = 0.039) and high baseline Overactive Bladder Symptom Score (OABSS) total score (coefficient = − 0.389, p = 0.002) were independent predictors of the improvement of OABSS total score. In conclusion, mirabegron nighttime dosing appears to benefit women more suffering from nocturia and urgency (especially urgency in the morning), and daytime dosing appears to benefit women with coexistent emotion dysfunction.

Trial registration NCT03251300, registered on 16/08/2017. Available at ClinicalTrials.gov, www.clinicaltrials.gov.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Overactive bladder syndrome (OAB) is characterized by urinary urgency, with or without urge incontinence, and usually occurs with urinary frequency and nocturia1. Among the above symptoms, urgency is the key symptom of OAB in women2.

Patients with OAB have a reduced quality of life resulting from depressive episodes, sleep disturbance and increased risk of falling and fracture due to nocturia3. As previously reported, 69% of women with OAB had an average of at least one episode of nocturia at baseline4.

Antimuscarinics and the beta-3 agonist are the main medications used to treat OAB. Mirabegron is the first beta-3 agonist approved for OAB treatment. Mirabegron is reported to have an efficacy similar to that of antimuscarinics5; however, the beta-3 agonist is associated with less annoying adverse effects, such as dry mouth6. Mirabegron reaches a maximum serum concentration approximately 3–4 h after administration, and its half-life was 50 h7. Mirabegron has been reported to improve insomnia and nocturia8.

Each time a physician prescribes a medication these days, the patient must accept or reject an electronic medical records default administration time. There is a comprehensive literature about the timing of medication administration as this is crucial for optimizing therapeutic effects and minimizing side effects across various conditions, including cardiovascular diseases, inflammation and auto-immune diseases. For examples, there are considerations related to food-drug absorption9; avoiding drug interactions (e.g., PDE-5 inhibitors and non-selective alpha-blockers10); avoiding side effects (i.e., non-selective alpha-blockers were given at night to mitigate postural hypotension11), or addressing circadian rhythms (i.e., bedtime administration of antihypertensive agents to mitigate morning blood pressure surges12 or short-acting lipid lowering agents given at night to affect the chronobiology of cholesterol synthesis13). Additionally, symptoms in some disease conditions may worsen at certain times of the day (e.g., nocturnal asthma)14,15.

Tsai et al. reported that tolterodine nighttime administration could benefit women with lower urinary tract symptoms, especially nocturia16. Mirabegron can be taken with or without food. However, it is not clear whether bedtime administration of beta-3 agonist could mitigate nocturia. Thus, we are interested to know whether nighttime dosing has superiority in reducing symptoms of OAB, such as nocturia episodes and urgency, compared to daytime dosing. Therefore, the aim of this study was to elucidate the differences in clinical efficacy between nighttime versus daytime dosing of mirabegron in women with OAB.

Methods

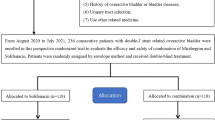

This study was conducted in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology in a tertiary referral center. Far Eastern Memorial Hospital Research Ethics Review Committee approved the study protocol (No.106001-F). The study design was prospective, randomized, controlled, and open label. This study has been registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03251300, date of registration: 16/08/2017). All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The screening visit was designed as visit 0. The inclusion criteria were women aged at least 20 years who had a history of urinary urgency in recent one month. Exclusion criteria included clinically significant dysuria, mixed urinary incontinence with dominant stress incontinence, ≥ stage III pelvic organ prolapse, neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (e.g., related to stroke, brain injury, spinal cord injury, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, or other neurodegenerative disease), and other symptoms that were contraindications to beta-3 agonists.

Eligibility was determined at visit 1 with the diagnosis of overactive bladder syndrome. The patients were requested to complete 20-min pad tests, urodynamic studies, and 3-day bladder diaries prior to visit 1. Patients were randomized into two groups using a computer-generated random number list to receive mirabegron 25 mg during the day (approximately 08:00) (i.e., the daytime group) or at night (approximately 20:00) (i.e., the nighttime group) once a day for 12 weeks. Participants were reminded of the exact time of mirabegron administration when the first prescription was obtained and again during follow-up visits. The randomization sequence was created using Excel 2007 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) with a 1:1 allocation using simple randomization. The patients were followed up at week 4 (visit 2) and week 12 (visit 3).

Participants enrolled were asked to complete the Urgency Severity Scales (USS)17, the Overactive Bladder Symptom Scores questionnaires18, and the King’s Health Questionnaires (KHQ)19 at each visit. Additionally, patients were asked to complete 3-day bladder diaries before each visit. The validated Chinese version of the USS questionnaire is a modified version of the Indevus Urgency Severity Scale17. Urgency severity as measured by the USS was rated by circling 0, 1, 2, or 3, which were defined as none, mild, moderate, and severe urgency, respectively. In addition to the scores of 0–317, we defined urgency with urinary incontinence as a score of 420. In this study, the KHQ inquires how much is the “affect” of this bladder symptom (i.e., 0—no symptom, 0—with symptom but no “affect”, 1—a little, 2—moderately, 3—a lot)19.

Urodynamic studies were performed with the Goby System (Laborie Medical Technologies Corp., Portsmouth, New Hampshire, USA), with patients in a seated position. The studies included uroflowmetry, filling (at a rate of 60 ml/min) and voiding cystometry (with an infusion of distilled water at 35 °C), and stress urethral pressure measurement (with a strong-desire amount of distilled water in the bladder)21.

All terminology used in this document conforms to the standards recommended by the joint report of the International Urogynecological Association and the International Continence Society22. STATA software (Version 11.0; StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA) was used for statistical analyzes. The paired t test was used as a statistical method. The dosing coefficient of dosing (nighttime = 1; daytime = 0) was derived from a linear regression analysis of the change from baseline in each parameter adjusted for the baseline variables. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The primary objective of this study was to compare the effect of nighttime dosing versus daytime dosing on diary counted symptoms of OAB, such as nocturia episodes and timeline diary counted urgency episodes (i.e., between-group differences in the changes of urgency episodes from baseline at 24:00–06:00, 06:00–12:00, 12:00–18:00 and 18:00–24:00). Secondary objectives of this study were to investigate the effects between groups on OAB symptoms from questionnaires, blood pressure, heart rate, and health-related quality of life. Based on a previous similar study on the comparison of the impact of nighttime versus daytime dosing of tolterodine ER on OAB symptoms16, we concluded that approximately 36 subjects in each group were required to test the null hypothesis. This study was a superior trial design23,24.

Results

A total of 109 patients were enrolled in the study. Fifty-seven patients were in the nighttime group and the other fifty-two patients were in the daytime group after 4 weeks of mirabegron treatment. Forty-six patients in the nighttime group and forty patients in the daytime group underwent 12 weeks of mirabegron treatment (Fig. 1).

The baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients were tabulated in Tables 1 and 2. Due to the presence of statistical differences in baseline urgency episodes (Table 1) and emotions (Table 2), we used linear regression analyses adjusted by the above variables to investigate the effect of dosing.

There was a significant reduction of nocturia episodes at 4 weeks (n = 23, 5.65 ± 3.71 at baseline vs. 4.26 ± 2.60 at 4 weeks, p = 0.019) and a trend to be a significant reduction at 12 weeks (n = 12, 6.58 ± 3.15 at baseline vs. 4.33 ± 3.84 at 12 weeks, p = 0.060) in the nighttime group. Contrarily, in the daytime group, there were no significant changes of nocturia episodes at 4 weeks (n = 16, 4.88 ± 2.80 at baseline vs. 4.25 ± 3.32 at 4 weeks, p = 0.435) and at 12 weeks (n = 11, 5.27 ± 3.10 at baseline vs. 4.27 ± 3.43 at 12 weeks, p = 0.219).

Although there was no between-group difference in the Question 2 score of OABSS (i.e., nocturia); however, there were a significant reduction of the score of nocturia at 4 weeks (1.98 ± 0.98 at baseline vs. 1.63 ± 1.01 at 4 weeks, p < 0.001) and at 12 weeks (1.95 ± 1.00 at baseline vs. 1.22 ± 1.01 at 12 weeks, p < 0.001) in the nighttime group, but not at 4 weeks (2.04 ± 0.91 at baseline vs. 1.90 ± 1.03 at 4 weeks, p = 0.18) in the daytime group (Table 3).

After 4 weeks of treatment, the nighttime group had more benefit in decreasing urgency episodes at 06:00–12:00 (change from baseline: − 2.1 ± 3.7 versus 0.1 ± 2.4, p = 0.003), 18:00–24:00 (change from baseline: − 1.4 ± 3.0 versus 0.4 ± 2.7, p = 0.01) and all day (change from baseline: − 6.4 ± 10.8 versus 0.1 ± 8.5, p = 0.005), compared to the daytime group (Table 3, Fig. 2). After adjustment by the corresponding baseline variables (i.e., urgency episodes in each time interval or total urgency episodes), the coefficients remained statistically significant (i.e., the coefficients of urgency episodes for nighttime dosing were − 1.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] = − 2.6 to − 0.5) at 06:00–12:00, p = 0.003; and − 4.1 (95% CI = − 7.4 to − 0.7) at all day, p = 0.02).

In addition, the daytime group had a significant improvement in emotions after 4 weeks of treatment (change from baseline: − 17 ± 25 versus − 6 ± 19, p = 0.006), compared to the nighttime group (Table 4, Fig. 3). After adjustment by the baseline emotions score, daytime dosing had a trend to be significant in improving emotions (i.e., the nighttime dosing coefficient was 7.68, 95% CI = − 0.02, to 15.37, p = 0.050).

After 12 weeks of treatment, both groups had significant improvements in USS, OABSS, and many domains of the KHQ, despite there being no differences between groups (Tables 3 and 4).

Improvement in depression (that is, KHQ Question 6A, one component of emotions, “Does your bladder problem make you feel depressed?”) was not associated with the improvement of OABSS (at 4 weeks, − 1.97 ± 3.32 vs. − 0.46 ± 0.95, Spearman’s rho = 0.04, p = 0.26; at 12 weeks, − 1.82 ± 2.72 vs. − 0.61 ± 1.01, Spearman’s rho = 0.13, p = 0.35).

Improvement in anxiety (that is, KHQ Question 6B, another component of emotions, “Does your bladder problem make you feel anxious or nervous?”) was not associated with the improvement of OABSS (at 4 weeks, − 1.97 ± 3.32 vs. − 0.43 ± 0.96, Spearman’s rho = 0.04, p = 0.67; at 12 weeks, − 1.82 ± 2.72 vs. − 0.60 ± 1.01, Spearman’s rho = − 0.12, p = 0.37).

Improvement in KHQ Question 6C (the other component of emotions, “Does your bladder problem make you feel bad about yourself?”) was not associated with the improvement of OABSS (4 weeks, − 1.97 ± 3.32 vs. − 0.10 ± 0.74, Spearman’s rho = 0.03, p = 0.74; 12 weeks, − 1.82 ± 2.72 vs. − 0.24 ± 0.84, Spearman’s rho = 0.02, p = 0.89).

Multivariable backward stepwise linear regression analysis was performed to predict the factors of the improvement of OABSS after 12 weeks of treatment. Young age (coefficient = 0.065, p = 0.039) and high baseline OABSS total score (coefficient = − 0.389, p = 0.002) were found to be independent predictors of the improvement of OABSS total score (Table 5).

Discussion

Although there is no between-group difference after treatment in nocturia episodes; however, a significant reduction of nocturia episodes at 4 weeks (p = 0.019), voiding episodes at 24:00–06:00 (within-group difference = − 1.4 ± 1.9, p = 0.007) and 06:00–12:00 (within-group difference = − 2.0 ± 3.7, p < 0.001) were observed in the nighttime group after 12 weeks of treatment. Contrarily, there was no significant improvement of nocturia episodes, voiding episodes at 24:00–06:00 (within-group difference = − 0.8 ± 2.9, p = 0.128) and 06:00–12:00 (within-group difference = − 0.0 ± 4.3, p = 0.966) in the daytime group (Table 3). To our knowledge, there is no literature that mentions the clinical effect of mirabegron nighttime versus daytime dosing on lower urinary tract symptoms. Our above findings may suggest that mirabegron nighttime administration could improve nocturia. Thus, bedtime administration of mirabegron is suggested for OAB women who are suffered from nocturia.

On the other hand, there was a significant reduction of voiding episodes at 18:00–24:00 (within-group difference = − 1.1 ± 2.9, p = 0.042) in the daytime dosing group. However, there was no improvement of voiding episodes at 18:00–24:00 (within-group difference = − 1.1 ± 3.8, p = 0.131) in the nighttime group (Table 3). For women who are concerned about the frequency of urination in the evening, morning administration should be a better option.

In this study, mirabegron nighttime administration could benefit a reduction in urgency episodes more, compared to daytime administration. The median time to reach the maximum concentration is 3–4 h and the elimination half-life of mirabegron is approximately 50 h7. Due to right-hand distribution of the mean mirabegron plasma concentration curve25, the mirabegron concentration could be high during 4 to 12 h after administration; thus, the above right-hand distribution phenomenon might explain why there was an improvement of urgency episodes at 06:00–12:00 in the nighttime group (Table 3). After adjustment, the reduction in urgency episodes remained statistically significant at 06:00–12:00 and all day. Thus, the improvement of urgency episodes at all day seems at least partly related to the improvement of urgency episodes in the morning.

In this study, we also found that mirabegron daytime administration is beneficial in emotions, comparing to nighttime administration (Table 4). In this study, the improvement of emotions at week 4 was not associated with the improvement of urgency episodes at 06:00–12:00 (Spearman’s rho = − 0.02, p = 0.84). Furthermore, the improvement in emotions was not associated with the improvement of urgency episodes of the day (Spearman’s rho = − 0.08, p = 0.11) or with the change in OABSS (Spearman’s rho = 0.03, p = 0.76). Thus, the improvement of emotions seems not subsequent to the improvement of urgency or OAB.

The beta-3 agonist has been shown to be helpful in patients with anxiety and depression26,27,28,29. Tanyeri et al. also reported that mirabegron could be useful for elderly patients with depression and anxiety30. Due to the higher concentration of mirabegron during 4–12 h after administration, it seems reasonable that daytime administration is beneficial to “emotions” (Table 4). The contents of the “emotions” domain include depression and anxiety. In women with OAB with psychologic distress, daytime administration may be better than nighttime administration to improve their depression/anxiety.

Kinjo et al. reported that mirabegron could improve anxiety and depression; however, the improvement of depression was not associated with the improvement of OABSS31. We also found that the improvement in depression (i.e., KHQ Question 6A, “Does your bladder problem make you feel depressed?”) was not associated with the improvement of OABSS. The improvement of anxiety (i.e., KHQ Question 6B, “Does your bladder problem make you feel anxious or nervous?”) was not associated with the improvement of OABSS. Thus, the improvement in emotions might be related to the direct effect of mirabegron, not subsequent to the improvement in OAB.

In this study, an improvement of nocturia episodes was observed in the nighttime group (Table 3), despite of no between-group difference (change from baseline: − 1.4 ± 1.9 versus − 0.8 ± 2.9, p = 0.40, Table 3). A superiority of nighttime administration of antimuscarinics had been observed in the treatment of nocturia16. Beta-3 agonists suppress detrusor contraction induced by endogenous acetylcholine, but does not suppress detrusor contraction induced by exogenous acetylcholine administration (only 25% reduction), and is involved in detrusor relation mediated by prejunctional mechanisms32. Mirabegron plasma concentrations peaked at 3 to 5 h and declined multiexponentially with a t1⁄2 of 32–60 h33. It has been reported that mirabegron can improve nocturia8,34,35. However, small sample size and different half-lifes between mirabegron (50 h) and tolterodine ER (6.2–11 h) might partly explain no differences in the impact on nocturia between the daytime and nighttime groups (Table 3)7,36.

It is worth mentioning that the questionnaire 2 of OABSS is “How many times do you typically wake up to urinate from sleeping at night until waking in the morning?” is not equally to the nocturia question in KHQ (i.e., the “affect” of “getting up at night to pass urine”). However, the correlation between OABSS (i.e., nocturia episodes) and KHQ (i.e., the “affect” due to nocturia) in nocturia is strong (Spearman’s rho = 0.64 in this study).

We found that young age and higher OABSS total scores were the predictors of the improvement of OABSS 12 weeks after mirabegron treatment (Table 5). Old age was found to be associated with added medication after OAB treatment37, and hint that old age was associated with less improvement of OAB after treatment. Additionally, an increase of severity in OAB was found to be associated with better therapeutic efficacy after solifenacin treatment20, and the above findings were in line with our current finding.

Urodynamic studies and 20-min pad tests were performed for our patients. However, according to the AUA/SUFU guideline, urodynamic studies should not be routinely performed in the evaluation of patients with OAB. In addition, bladder diary may be obtained to assist in the diagnosis of OAB, exclude other disorders, ascertain the degree of bother, and/or evaluate treatment response38. From the bladder diaries, those women who are suffered from nocturia and urgency (especially in the morning) might benefit from bedtime dosing of mirabegron.

In this study, there was no association between OABSS total score and pad weights (Spearman’s rho = 0.176, p = 0.070) and there was no association between USS total score and pad weights (Spearman’s rho = 0.171, p = 0.079). Thus, the 20-min pad test, a test for assessing the severity of urine leakage in women with stress urinary incontinence39, cannot be used to assess the severity of OAB.

The maximum physiological filling rate is estimated to be a quarter of body mass (kg) in ml/min, usually between 20 to 30 ml/min. For the balance between a filling rate, which is physiological enough to reproduce the patient’s symptoms, and a rate fast enough to complete the test promptly40, the filling rate is suggested not to exceed 50 mL/min41,42. An increase in filling rate may act as a mechanical trauma to receptors, and decrease bladder compliance, increase micturition pressure thresholds and increase urgent voids43,44,45. In our study, the filing rate of 60 mL/min is higher than the maximum recommended filling rate (i.e., 50 mL/min); thus, our filing rate of 60 mL/min may increase in the estimated rate of detrusor overactivity (Table 1).

This study also has limitations. This study was not a blinded study. Some of bladder diaries in this study did not record sleep times making it difficult to tally nocturia. This was a single site sample. There was a significant drop out rate within the 12-week study. The ready availability of mirabegron in most outpatient clinics obviates the need for travel to medical centers, and the above phenomenon might partly explain our dropout rate46. Most of the enrolled women were Taiwanese and this might limit its generalisability.

In addition, the nighttime group has a lower OABSS total score but appears much worse in diary recorded urgency symptoms (Table 1). However, multivariable linear regression analysis by using bladder diary parameters to predict OABSS showed that urinary incontinence episodes was the sole independent predictor for OABSS (coefficient = 0.571, p < 0.001), but not frequency episodes (coefficient = 0.024, p = 0.338) or urgency episodes (coefficient = 0.012, p = 0.670). Our nighttime group had a lower mean urinary incontinence score than the daytime group (1.2 ± 1.8 versus 1.8 ± 3.3). Thus, the above might partly explain the phenomenon about that the nighttime group has a lower OABSS score but worse in diary recorded urgency symptoms.

In our hospital, only 25 mg of mirabegron is available, but not 50 mg. In Taiwan, the United States and Canada, the recommended starting dose is 25 mg once daily, with the option of increasing 50 mg once daily47,48. In addition, according to the report by Iitsuka et al.49, although the time to reach maximum plasma concentration was similar (i.e., 3.6 ± 1.0 h for 25 mg, 3.5 ± 0.9 h for 50 mg, and 3.3 ± 1.1 h for 100 mg), the increase in maximum plasma concentration of mirabegron was greater than the increase in dose when a single dose of 25–100 mg was given (i.e., maximum plasma concentration: 9.88 ± 3.91 ng/mL for 25 mg, 30.1 ± 16.8 ng/mL for 50 mg, and 80.5 ± 31.7 ng/mL for 100 mg). Therefore, if a patient is treated with 50 mg of mirabegron, the effect of taking the medication at night and during the day may be different compared with that of taking 25 mg of mirabegron.

In conclusions, mirabegron nighttime dosing appears to benefit women suffering from nocturia and urgency (especially in the morning), and daytime dosing appears to benefit women with coexistent emotion dysfunction.

Data availability

The datasets generated and / or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abrams, P. et al. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: Report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology 61, 37–49 (2003).

Hung, M. J. et al. Urgency is the core symptom of female overactive bladder syndrome, as demonstrated by a statistical analysis. J. Urol. 176, 636–640 (2006).

Stewart, R. B., Moore, M. T., May, F. E., Marks, R. G. & Hale, W. E. Nocturia: A risk factor for falls in the elderly. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 40, 1217–1220 (1992).

Fitzgerald, M. P., Lemack, G., Wheeler, T. & Litman, H. J. Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network. Nocturia, nocturnal incontinence prevalence, and response to anticholinergic and behavioral therapy. Int. Urogynecol. J. 19, 1545–1550 (2008).

Chapple, C. R. et al. Safety and efficacy of mirabegron: Analysis of a large integrated clinical trial database of patients with overactive bladder receiving mirabegron, antimuscarinics, or placebo. Eur. Urol. 77, 119–128 (2020).

Wagg, A. et al. Oral pharmacotherapy for overactive bladder in older patients: Mirabegron as a potential alternative to antimuscarinics. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2, 621–638 (2016).

Sacco, E. & Bientinesi, R. Mirabegron: A review of recent data and its prospects in the management of overactive bladder. Ther. Adv. Urol. 4, 315–324 (2012).

Petrossian, R. A., Dynda, D., Delfino, K., El-Zawahry, A. & McVary, K. T. Mirabegron improves sleep measures, nocturia, and lower urinary tract symptoms in those with urinary symptoms associated with disordered sleep. Can. J. Urol. 27, 10106–10117 (2020).

Deng, J. et al. A review of food-drug interactions on oral drug absorption. Drugs 77(17), 1833–1855 (2017).

Kloner, R. A. et al. Princeton IV consensus guidelines: PDE5 inhibitors and cardiac health. J. Sex. Med. 21(2), 90–116 (2024).

Gül, O., Eroğlu, M. & Ozok, U. Use of terazosine in patients with chronic pelvic pain syndrome and evaluation by prostatitis symptom score index. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 32(3), 433–436 (2001).

Jiang, H., Yu, Z., Liu, J. & Zhang, W. Bedtime administration of antihypertensive medication can reduce morning blood pressure surges in hypertensive patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Palliat. Med. 10(6), 6841–6849 (2021).

Awad, K. & Banach, M. The optimal time of day for statin administration: a review of current evidence. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 29(4), 340–345 (2018).

Beam, W. R., Weiner, D. E. & Martin, R. J. Timing of prednisone and alterations of airways inflammation in nocturnal asthma. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 146(6), 1524–1530 (1992).

Pincus, D. J., Humeston, T. R. & Martin, R. J. Further studies on the chronotherapy of asthma with inhaled steroids: The effect of dosage timing on drug efficacy. J. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 100(6 Pt 1), 771–774 (1997).

Tsai, K. H., Hsiao, S. M. & Lin, H. H. Tolterodine treatment of women with overactive bladder syndrome: Comparison of night-time and daytime dosing for nocturia. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 43, 1719–1725 (2017).

Nixon, A. et al. A validated patient reported measure of urinary urgency severity in overactive bladder for use in clinical trials. J. Urol. 174, 604–607 (2005).

Homma, Y. et al. Symptom assessment tool for overactive bladder syndrome–overactive bladder symptom score. Urology 68(2), 318–323 (2006).

Kelleher, C. J., Cardozo, L. D., Khullar, V. & Salvatore, S. A new questionnaire to assess the quality of life of urinary incontinent women. Br. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 104(12), 1374–1379 (1997).

Hsiao, S. M., Lin, H. H. & Kuo, H. C. Factors associated with a better therapeutic effect of solifenacin in patients with overactive bladder syndrome. Neurourol. Urodyn. 33(3), 331–334 (2014).

Schäfer, W. et al. Good urodynamic practices: uroflowmetry, filling cystometry, and pressure-flow studies. Neurourol. Urodyn. 21, 261–274 (2002).

Haylen, B. T. et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint report on the terminology for female pelvic floor dysfunction. Int. Urogynecol. J. 21, 5–26 (2010).

Kishore, K. & Mahajan, R. Understanding superiority, noninferiority, and equivalence for clinical trials. Indian. Dermatol. Online. J. 11(6), 890–894 (2020).

Dunn, D. T., Copas, A. J. & Brocklehurst, P. Superiority and non-inferiority: Two sides of the same coin?. Trials 19, 499 (2018).

Dickinson, J. et al. Effect of renal or hepatic impairment on the pharmacokinetics of mirabegron. Clin. Drug Investig. 33, 11–23 (2013).

Overstreet, D. H., Stemmelin, J. & Griebel, G. Confirmation of antidepressant potential of the selective beta3 adrenoceptor agonist amibegron in an animal model of depression. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 89, 623–626 (2008).

Stemmelin, J. et al. Stimulation of the beta3-Adrenoceptor as a novel treatment strategy for anxiety and depressive disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 33, 574–587 (2008).

Tamburella, A., Micale, V., Leggio, G. M. & Drago, F. The beta3 adrenoceptor agonist, amibegron (SR58611A) counteracts stress-induced behavioral and neurochemical changes. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 20, 704–713 (2010).

Consoli, D., Leggio, G. M., Mazzola, C., Micale, V. & Drago, F. Behavioral effects of the beta3 adrenoceptor agonist SR58611A: is it the putative prototype of a new class of antidepressant/anxiolytic drugs?. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 573, 139–147 (2007).

Tanyeri, M. H. et al. Effects of mirabegron on depression, anxiety, learning and memory in mice. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 93(suppl 4), e20210638 (2021).

Kinjo, M., Yamaguchi, T., Tambo, M., Okegawa, T. & Fukuhara, H. Effects of mirabegron on anxiety and depression in female patients with overactive bladder. Urol. Int. 102(3), 331–335 (2019).

Kwon, J. et al. Pathophysiology of overactive bladder and pharmacologic treatments including β3-adrenoceptor agonists -basic research perspectives. Int. Neurourol. J. 28(Suppl 1), 12–33 (2024).

Krauwinkel, W. et al. Pharmacokinetic properties of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist: Results from two phase I, randomized, multiple-dose studies in healthy young and elderly men and women. Clin. Ther. 34(10), 2144–2160 (2012).

Suzuki, T. et al. Effect of oxybutynin patch versus mirabegron on nocturia-related quality of life in female overactive bladder patients: A multicenter randomized trial. Int. J. Urol. 28(9), 944–949 (2021).

Lee, C. L., Ong, H. L. & Kuo, H. C. Therapeutic efficacy of mirabegron 25 mg monotherapy in patients with nocturia-predominant hypersensitive bladder. Tzu. Chi. Med. J. 32(1), 30–35 (2019).

Olsson, B. & Szamozi, J. Multiple dose pharmacokinetics of a new once daily extended release tolterodine formulation versus immediate release tolterodine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 40, 227–235 (2001).

Hsiao, S. M. Predictors of non-persistence in women with overactive bladder syndrome. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 7499 (2024).

Cameron, A. P. et al. The AUA/SUFU guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic overactive bladder. J. Urol. 212(1), 11–20 (2024).

Wu, W. Y., Hsiao, S. M., Wu, P. C. & Lin, H. H. Test-retest reliability of the 20-min pad test with infusion of strong-desired volume in the bladder for female urodynamic stress incontinence. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 18472 (2020).

Yao, M. & Simoes, A. Urodynamic Testing and Interpretation in StatPearls (StatPearls, Treasure Island, 2025).

Rosier, P. F. W. M. et al. International Continence Society good urodynamic practices and terms 2016: Urodynamics, uroflowmetry, cystometry, and pressure-flow study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 36(5), 1243–1260 (2017).

D’Ancona, C. et al. The International Continence Society (ICS) report on the terminology for adult male lower urinary tract and pelvic floor symptoms and dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn. 38(2), 433–477 (2019).

Kim, A. K. & Hill, W. G. Effect of filling rate on cystometric parameters in young and middle aged mice. Bladder (San Franc). 4(1), e28 (2017).

Klevmark, B. Volume threshold for micturition. Influence of filling rate on sensory and motor bladder function. Scand. J. Urol. Nephrol. Suppl. 210, 6–10 (2002).

Redmond, E. J., O’Kelly, T. & Flood, H. D. The effect of bladder filling rate on the voiding behavior of patients with overactive bladder. J. Urol. 202(2), 326–332 (2019).

Hsiao, S. M. & Chang, S. R. Effect of tibolone versus hormone replacement therapy on lower urinary tract symptoms and sexual function. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 123(6), 710–715 (2024).

Chapple, C. R. et al. Onset of action of the β3-adrenoceptor agonist, mirabegron, in Phase II and III clinical trials in patients with overactive bladder. World J. Urol. 32(6), 1565–1572 (2014).

Liao, C. H. & Kuo, H. C. Mirabegron escalation to 50 mg further improves daily urgency and urgency urinary incontinence in Asian patients with overactive bladder. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 118(3), 700–706 (2019).

Iitsuka, H. et al. Pharmacokinetics of mirabegron, a β3-adrenoceptor agonist for treatment of overactive bladder, in healthy Japanese male subjects: Results from single- and multiple-dose studies. Clin. Drug. Investig. 34(1), 27–35 (2014).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and animal rights

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (Far Eastern Memorial Hospital Research Ethics Review Committee, No. 106001-F, approval date: 01 August 2017) at Far Eastern Memorial Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hsiao, SM. Mirabegron nighttime versus daytime dosing for women with overactive bladder syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 15, 30687 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15780-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-15780-5