Abstract

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) significantly impacts the quality of life of many elderly women. However, current treatment options have limited efficacy. In our previous research, we demonstrated that a novel miniature, wireless implantable electrical stimulation device (NuStim) is capable of improving the leak point pressure in a rat model of postpartum SUI. However, the underlying mechanism remains unclear. Therefore, we investigated the effects of Nustim on histological and collagen changes in the pelvic floor tissue. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was used to observe tissue structure and cellular morphology, Masson’s trichrome staining was applied to assess collagen fiber content, and electron microscopy was utilized to examine ultrastructural changes. Collagen content, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) were measured using Western blot and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Our findings revealed that after two weeks of Nustim treatment, the morphology of tissues, cells, and organelles improved, inflammatory responses were attenuated, and the levels of collagen content, MMPs, and TIMPs basically returned to normal. Nustim has a beneficial effect on alleviating the pathological changes and excessive collagen degradation, and may represent a promising therapeutic modality for SUI, with potential for clinical translation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urinary incontinence, the involuntary loss of urine, is common among women and can cause physical, emotional, and social distress1. Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a subtype of incontinence with symptoms of involuntary leakage of urine during activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure (e.g., coughing, sneezing or laughing). The overall prevalence of SUI (when defined as any symptoms in the previous year) among adult women is approximately 46%2. Despite its widespread occurrence, SUI remains under recognized and under reported, with less than 40% of affected women seeking medical care3.

In 1948, Arnold Kegel introduced Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (PFMT) as a behavioral intervention to alleviate SUI symptoms. The primary aim of PFMT is to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles and improve their ability to contract in response to increased intra-abdominal pressure. While PFMT is an affordable and generally effective treatment option, it has limitations. Many patients face difficulties with long-term adherence, and treatment outcomes vary significantly between individuals4. Some patients experience substantial improvements, while others show minimal response. Moreover, the need for continuous professional guidance increases the time and financial burden associated with this therapy. For patients with severe pelvic floor dysfunction, PFMT alone may not be sufficient to achieve satisfactory results. From a muscle physiology perspective, both active muscle contractions and passive electrical stimulation produce similar therapeutic effects. Pelvic Floor Electrical Stimulation (PFES) is a non-invasive treatment that uses low-frequency electrical currents delivered through electrodes placed on the skin, vagina, or rectum to stimulate the pelvic floor muscles and related nerves. Studies have demonstrated that PFES can significantly improve SUI symptoms in patients with insufficient or inaccurate pelvic floor muscle contractions5. However, the deep location of the pelvic floor muscles beneath the skin or mucosa can lead to discomfort or irritation during electrical stimulation, which may reduce patient compliance and also affect the transmission of electrical energy to the deeper tissues.

For patients with mild to moderate SUI, conservative treatments remain the first-line options. However, for those with severe symptoms and patients who respond poorly to conservative treatments, surgical interventions often provide the most effective outcomes. Implantable electrical stimulation (IES) in muscle activation, bone regeneration, nerve modulation, and neural regeneration has provided new solutions for treating complications that are difficult to treat by other means6,7,8,9. We have developed a miniature, implantable, wireless nerve stimulator (NuStim), which can be precisely implanted into the target muscles through minimally invasive surgery. This device can induce strong muscle contractions without voluntary effort10. In a subsequent study, we tested NuStim in a postpartum rat model of SUI. Biphasic exponential pulses (0.2 ms pulse width) were utilized for stimulation. The threshold, T, was determined as the minimum intensity required to elicit observable muscle contraction in the anus. Stimulation was administered daily at a frequency of 6 Hz and intensity of 2 T for 30 min per day over a period of 2 weeks. Following the completion of treatment, urodynamic tests were performed. In the stimulation group, leak point pressure (LPP) values at baseline, after vaginal distension (VD), and after two weeks of treatment were 48.4 ± 4.8, 17.8 ± 3.9, and 48.4 ± 8.5 cmH₂O, respectively. Compared with the values after VD, there was a significant improvement after two weeks of treatment (P < 0.001), returning to the baseline level. This provided the first experimental evidence that NuStim could induce pelvic floor muscle contractions and alleviate SUI symptoms, supporting its future use in both home care and clinical settings11.

In this study, we explore the therapeutic mechanisms of NuStim in treating SUI, with a focus on the tissue structure, cellular structure, ultrastructure, and changes in key organelles in the pelvic floor muscles and anterior vaginal wall. Additionally, we investigate changes in collagen fibers and collagen content, as well as alterations in enzymes related to collagen regulation, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs).

Results

Pelvic floor muscle tissue structure and inflammatory cell infiltration

In the blank group, the tissue structure was generally normal. Muscle fibers were arranged neatly and densely, with clear contours, and no abnormalities were observed. Muscle cell nuclei were intact, the cytoplasm was abundant, and no necrosis was seen. There was no obvious inflammatory cell infiltration in the tissue (Fig. 1A).

NuStim improved the tissue structure of pelvic floor muscles and the anterior vaginal wall tissue, reducing inflammatory cell infiltration. Representative H&E staining of pelvic floor muscle and anterior vaginal wall tissue in rats at 200× magnification. The images display staining for fibrosis (indicated by blue arrows), infiltrated inflammatory cells (red arrows), muscle fibers (yellow arrows), and the keratinized epithelial layer (black arrows).

In the control group, the tissue structure showed mild to moderate abnormalities. A large number of muscle fibers exhibited fibrosis (blue arrows). Individual inflammatory cell infiltration was observed (red arrows). The muscle fibers appeared loosely arranged and reduced in diameter (yellow arrows). Some muscle cell nuclei were intact, the cytoplasm was abundant, and no necrosis was observed. There was no obvious inflammatory cell infiltration (Fig. 1B).

In the sham group, the tissue structure showed mild abnormalities. The muscle fibers appeared loosely arranged (yellow arrows). Muscle cell nuclei were intact, the cytoplasm was abundant, and no necrosis was seen. Individual inflammatory cell infiltrations was observed (red arrows) (Fig. 1C).

In the stimulation group, the tissue structure showed mild abnormalities. Muscle fibers were arranged neatly and densely, with clear contours, and no abnormalities were observed. Muscle cell nuclei were intact, the cytoplasm was abundant, and no necrosis was seen. Individual inflammatory cell infiltrations were observed (red arrows) (Fig. 1D).

Anterior vaginal wall tissue structure and inflammatory cell infiltration

In the blank group, the tissue structure appeared generally normal. The epithelial structure of the mucosal layer was clear, with uniform thickness and no signs of hyperplasia. Elastic fibers in the lamina propria were neatly and densely arranged, with no abnormalities or inflammatory cell infiltration observed (Fig. 1A).

In the control and sham groups, mild structural abnormalities were noted. A keratinized layer was observed in the mucosal epithelium (blank arrows), and elastic fibers in the lamina propria were loosely arranged in some areas (yellow arrows). A small amount of inflammatory cell infiltration was also present (red arrows) (Fig. 1B,C).

In the stimulation group, the tissue structure was generally normal or exhibited mild abnormalities. The mucosal epithelial structure was clear with uniform thickness and no signs of hyperplasia. Elastic fibers in the lamina propria were arranged neatly and densely, with no significant abnormalities or inflammatory cell infiltration, though occasional individual inflammatory cells were observed (Fig. 1D).

Collagen fiber content in pelvic floor tissue

Masson’s staining of the pubococcygeus muscle and anterior vaginal wall tissue is shown in Fig. 2A. The collagen fiber content in the control group, sham group, and stimulation group was significantly lower than that in the blank group. The stimulation group showed a trend of higher collagen fiber content than the sham group in both tissues, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2B,C). Compared with the anterior vaginal wall tissue, the content of collagen fibers in the pubococcygeus muscle decreased more significantly.

NuStim increased the collagen fiber content in the pelvic floor muscle and anterior vaginal wall under Masson staining. (A) Masson’s trichrome stain of pelvic floor muscle and anterior vaginal wall tissue, 200× magnification. (B) Histogram of collagen fiber percentage in pelvic floor muscle tissue. (C) Histogram of collagen fiber percentage in anterior vaginal wall tissue. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (n = 6/group).

Pelvic floor muscle ultrastructure as revealed by electron microscopy

In the blank group (Fig. 3A), muscle fibers were arranged neatly and orderly, with abundant myofibrils, thicker diameters, and clearly defined light and dark bands. The number of mitochondria was relatively low, and no obvious degeneration was observed. In the control group, muscle fibers were severely damaged, with swollen fibers, unclear boundaries between light and dark bands, and a large number of myofibrils broken, leading to widened gaps (yellow arrows). Surrounding myofibrils appeared atrophied and thinner (red arrows). The number of mitochondria increased, with irregular shapes, and some mitochondrial membranes were ruptured (green arrows). The structure of the sham group was similar to that of the control group, with loosely arranged myofibrils, some of which were broken. The number of mitochondria increased, with irregular shapes. In the stimulation group, the degree of muscle fiber damage was significantly improved compared to the control group, with myofibrils arranged more neatly and densely, and clear boundaries between light and dark bands. Mild edema was observed in some areas, with widened gaps, and the number of mitochondria was relatively high, with more regular shapes (green arrows).

NuStim improved the microstructure of the pelvic floor muscle and anterior vaginal wall, reduced the mitochondrial abnormalities and endoplasmic reticulum under electron microscopy. Mitochondria are indicated by green arrows, while myofibrillar rupture is marked by yellow arrows. Myofibrillar atrophy and thinning are highlighted by red arrows, and the endoplasmic reticulum is indicated by black arrows. The scale bar represents 2 μm in the pelvic floor muscle image (A), and 1 μm in the anterior vaginal wall image (B).

Anterior vaginal wall ultrastructure as revealed by electron microscopy

In the blank group (Fig. 3B), the structure of vaginal epithelial cells was normal, with a relatively large number of mitochondria that had regular shapes, clear mitochondrial cristae, no obvious ruptures, and intact membranes (green arrows). The endoplasmic reticulum showed no significant expansion (black arrows). In the control group, the structure was severely abnormal, with the endoplasmic reticulum showing severe expansion (black arrows). The number of mitochondria was reduced, and the remaining mitochondria had ruptured membranes, broken cristae, and visible electron-lucent areas (green arrows). The structure of the sham group was similar to that of the control group, with severe damage. In the stimulation group, the degree of damage was significantly improved compared to the control group, with no significant expansion of the endoplasmic reticulum (black arrows) and occasional mitochondrial membrane ruptures (green arrows).

Collagen, MMPs, and TIMPs in pelvic floor muscles by Western blot

The levels of collagen I and collagen III in the stimulation group were similar to those in the blank group but significantly higher than those in the control and sham groups, with statistical significance (P < 0.001).

The levels of MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in the stimulation group were similar to those in the blank group but significantly lower than in the control and sham groups, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.001).

The levels of TIMP-2 and TIMP-3 in the stimulation group were similar to those in the blank group but were significantly higher than those in the control and sham groups, with these differences being statistically significant (P < 0.001).

The level of TIMP-1 in the stimulation group was significantly higher than in the blank, control, and sham groups, with these differences being statistically significant (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4).

Collagen, MMPs, and TIMPs in anterior vaginal wall by Western blot

The levels of collagen I and collagen III in the stimulation group were similar to those in the blank group but significantly higher than those in the control and sham groups, with statistical significance (P < 0.001).

The levels of MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in the stimulation group were similar to those in the blank group but significantly lower than in the control and sham groups, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.001).

The levels of TIMP-1, TIMP-2 and TIMP-3 in the stimulation group were similar to those in the blank group but significantly higher than in the control and sham groups, with statistically significant differences (P < 0.001) (Fig. 5).

Collagen, MMPs, and TIMPs in pelvic floor muscles by ELISA

The inter-group differences for MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP-1, and TIMP-3 among the blank, control, sham, and stimulation groups were consistent with Western blot (WB) measurements, with the stimulation group showing statistically significant differences compared to the control and sham groups (P < 0.01), but no statistical difference compared to the blank group. Additionally, the levels of collagen I, collagen III, and TIMP-2 exhibited similar trends to the WB results, but the stimulation group did not reach statistical significance compared to the control and sham groups (Fig. 6).

Collagen, MMPs, and TIMPs in anterior vaginal wall by ELISA

The inter-group differences for collagen III, MMP-1, MMP-9, TIMP-1, and TIMP-2 among the blank, control, sham, and stimulation groups were consistent with WB measurements, with the stimulation group showing statistically significant differences compared to the control and sham groups (P < 0.01), but no statistical difference compared to the blank group.

Additionally, the levels of collagen I, MMP-2, and TIMP-3 exhibited similar trends to the WB results, but the stimulation group did not reach statistical significance compared to the control and sham groups (Fig. 7).

Discussion

There are two main mechanisms of SUI. The first, urethral hypermobility, occurs because of loss of support of the pelvic floor muscles or vaginal connective tissue, such that the urethra and bladder neck do not close sufficiently in response to increases in intra-abdominal pressure. The second, intrinsic sphincter deficiency, occurs because of loss of urethral mucosal and muscular tone, which leads to poor urethral closure12.

Pelvic muscles are major contributors to continence. The contraction of the levator ani pulls the vagina forward toward the pubic symphysis, providing support for the urinary tract. This stable support compresses the two walls of the urethra, effectively preventing urine leakage during coughing or similar increases in intra-abdominal pressure13. The integrity and strength of the pelvic floor muscle structure directly affect its ability to support these pelvic organs. If the number or quality of muscle fibers decreases, due to factors like aging or childbirth injuries, it may lead to pelvic floor dysfunction, such as SUI or uterine prolapse14,15. The elasticity and connective tissue of the anterior vaginal wall play a stabilizing role in urethral function by closely connecting to the urethra, helping to maintain its normal position and closure mechanism16.

As the fetus passes through the birth canal, particularly during the second stage of labor, the pelvic floor muscles—such as the pubococcygeus muscle—along with other supporting structures like the vaginal wall and perineum, experience intense stretching. If the stretch exceeds their elastic limit, it may result in tissue injury15. In the control group, HE staining showed mild to moderate abnormalities in the pelvic floor muscle structure. The muscle fibers appeared loosely arranged and reduced in size. Electron microscopy showed severe muscle fiber damage, with indistinct boundaries between the A and I bands and extensive myofibril rupture, resulting in enlarged interstitial spaces. Additionally, mild abnormalities were observed in the structure of the anterior vaginal wall tissue under HE staining, with keratinization seen in the epithelial layer of the mucosa and localized loosening of elastic fibers in the lamina propria.

After childbirth, damage to the pelvic floor related tissues triggers an inflammatory response. Muscle regeneration is tightly regulated by the immune response that is characterized by 2 phases: proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory17. Immune cells such as leukocytes and macrophages accumulate at the injury site to clear tissue debris and cellular remnants, while releasing inflammatory mediators18,19. This phase is accompanied by localized swelling, pain, and functional impairment. Aged mitochondria in skeletal muscle show an increased rate of abnormalities, characterized by swelling, enlargement, and more branching, along with structural impairments such as disrupted membranes, loss of cristae, matrix dissolution, and vacuolization20,21,22,23,24. Mitochondrial networks are dynamic and undergo continuous fission and fusion, which are essential for maintaining normal morphology and adapting to energy needs. Fusion involves the coordinated integration of outer and inner membranes, resulting in elongated structures that facilitate material exchange and support self-homeostasis25,26,27. In contrast, fission refers to the scission of both membranes, breaking the tubular networks into smaller organelles. This process is crucial for efficiently removing dysfunctional mitochondria, enabling mitophagy to eliminate damaged components. In older adults, ATP production declines, and the accumulation of impaired mitochondria may contribute to muscle fiber death27,28,29. The endoplasmic reticulum expands to increase protein synthesis capacity. Electron microscopy revealed that in the control group, muscle fibers were edematous, and mitochondria exhibited irregular shapes, with some mitochondrial membranes ruptured. The mucosal structure of the anterior vaginal wall showed severe abnormalities, including significant expansion of the endoplasmic reticulum, a reduction in mitochondrial numbers, and ruptured membranes and cristae of the remaining mitochondria. In the stimulation group, NuStim promoted muscle regeneration, improved tissue structure, and inhibited the inflammatory response.

Collagen is the primary structural component of all connective tissues, essential for maintaining the stability and structural integrity of tissues and organs. Type I collagen is the most prevalent and well-researched type, serving as the major collagen in tendons, skin, ligaments, and various interstitial connective tissues. Type III collagen, which constitutes about 5–20% of the total collagen content in the human body, is classified as one of the major fibrillar collagens. It is often found in association with Type I collagen in many tissues, together providing tensile strength30,31. Insufficient collagen content or imbalanced ratio of these collagen types may result in tissue laxity or weakness, thereby increasing the risk of pelvic floor dysfunction32,33. Following childbirth, the deposition and synthesis of collagen are essential for repairing damaged tissues. Excessive collagen degradation can lead to incomplete repair, heightening the risk of long-term functional impairments34. Our research has confirmed that childbirth can lead to a decrease in collagen content in the pelvic floor support structures, and that treatment with NuStim can restore collagen levels to or near normal levels.

Collagen is the primary component of the extracellular matrix (ECM), a type of connective tissue in the cell microenvironment that is crucial for tissue development. The ECM in the muscle fiber niche comprises three layers: the epimysium, perimysium, and endomysium (basal lamina). These layers not only help maintain the structure of skeletal muscle but also play vital roles in muscle cell functions, including mechanical force transmission, muscle fiber regeneration, and neuromuscular junction formation35. An intact ECM supports the regeneration of muscle fibers following damage, and the activation of satellite cells triggers local remodeling of the ECM to repair the damaged basal lamina36.

The ECM is continuously remodeled in a tightly regulated manner37. Collagen breakdown is regulated by MMPs. The interstitial and neutrophil collagenases (MMP-1) cleave fibrillar collagen, while denatured collagen peptides are degraded by gelatinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9)38. The activity of these enzymes is further modulated by TIMPs, which bind to MMPs and regulate their function34. Women with SUI excrete higher levels of helical peptide α-1, a collagen breakdown product, in their urine, indicating an overactive degradation mechanism39.

The results of this study, based on observations from Western blot and ELISA, indicate that the levels of MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-9 in the stimulation and blank groups did not show significant differences but were significantly lower than those in the control and sham groups. NuStim reduced excess MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-9 during tissue repair. If the content of MMPs is not adequately controlled, it can lead to excessive collagen degradation, resulting in tissue damage.

Additionally, the levels of TIMP-1, TIMP-2, and TIMP-3 in the stimulation and blank groups were not significantly different but were significantly higher than those in the control and sham groups. In the control and sham groups, Nustim restored TIMP expression in the stimulation group. The normal content of these two classes of collagen-regulating enzymes helped prevent excessive collagen degradation in the stimulation group, with collagen fiber content similar to that of the blank group.

However, the proteins of some types detected by ELISA in this study did not show statistically significant differences when compared to those measured by WB. This may be due to a small sample size, and this experiment can serve as a preliminary study to calculate the required sample size for future research. Additionally, post-translational modifications of proteins may affect the binding of antibodies. Finally, the different quantification methods used in WB and ELISA can lead to inconsistencies in the detection results. Overall, all proteins exhibited the same trend of changes across the different detection methods. Considering the core role of the pubococcygeus muscle in urinary control of rats, and that the stimulation effect on the ipsilateral side of the stimulator might be optimal, this study used the pubococcygeus muscle on the stimulated side. However, since stimulation treats the entire pelvic floor tissue, we will further analyze the contralateral side in the future.

This study verifies the injury mechanisms of postpartum SUI while examining the structural and molecular-level effects of NuStim on pelvic floor muscles and anterior vaginal wall tissues, further revealing its mechanisms for improving SUI symptoms. These findings enhance the understanding of NuStim’s role in tissue repair, providing a solid scientific foundation for optimizing treatment strategies and advancing clinical applications. In the future, we will further explore the therapeutic effects of NuStim on neural control and the biomechanics of the pelvic floor, as well as its impact on omics changes, to gain deeper insights into NuStim’s role in the treatment of SUI. This treatment method based on electrical stimulation may even become part of a combined therapy with PRP local injection, stem cell therapy, and treatments like pro-regenerative extracellular matrix hydrogel, to provide even more powerful therapeutic effects.

Our study demonstrated that NuStim prevented excessive collagen degradation, promoted muscle fiber regeneration, and improved tissue structure. The balanced expression of MMPs and TIMPs in the pelvic floor muscles and anterior vaginal wall provides a molecular basis for the recovery of pelvic floor tissues and the improvement of SUI symptoms.

Materials and methods

Device introduction

The NuStim® device (General Stim Inc., Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China) implanted in the rats features three primary components: a stimulator (Fig. 8A), a radio frequency (RF) cushion (Fig. 8B), and an Android pad (Fig. 8C). The stimulator, which has a cylindrical shape with a diameter of 3 mm and a length of 10 mm, is housed in a glass tube with electrodes at both ends. It receives electromagnetic signals from the RF cushion to generate stimulation current signals. Stimulation parameters are set through the App and sent to the RF cushion, with ranges including intensity from 0 to 16 V, frequency from 4 to 50 Hz, and pulse width from 40 to 450 μs.

Characteristics of the device: (A) the stimulator is used to receive electromagnetic signals from the radio frequency (RF) cushion and generate current signals; (B) the RF cushion is used to receive the Bluetooth signals from the App terminal and generate the electromagnetic signals to activate the stimulator; (C) the App interface is used to record the patient’s basic information, adjust stimulus parameters, test and implement the stimulus protocol, and send feedback to the professionals. (D) X-ray was obtained to further confirm that the stimulator was at the appropriate position. (E) A schematic diagram of stimulation process.

Experimental animals

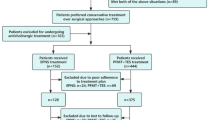

The experiments involved 24 nulliparous female Sprague–Dawley rats, each weighing 250–300 g and aged 2–3 months, sourced from Beijing Jinmuyang Experimental Animal Breeding Co., Ltd. The rats were randomly divided into four groups: blank, control, sham, and stimulation, with six rats per group. Prior to the experiments, all groups were housed individually in appropriately sized enclosures at 22–24 °C with 65–70% humidity and adequate ventilation. They received a nutritionally balanced diet suitable for their species and were kept in a clean environment for at least one week to acclimate and reduce stress. All procedures complied with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and approval was granted by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Capital Medical University (AEEI-2024–055). This study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines.

Model preparation, stimulator implantation and stimulation protocol

According to our well-established protocols, the following procedures were performed11. The rats were randomly divided into four groups: blank, control, sham, and stimulation, with six rats in each group. SUI models were established using VD in all groups except the blank group. The rats were anesthetized with urethane (1.2 g/kg, intraperitoneal injection), then underwent urodynamic testing and balloon inflation in the vagina with a 0.3 kg sandbag suspended for 8 h. Vital signs of rats were monitored in a suitable environment. They generally regain consciousness approximately 8 h after anesthesia, followed by a gradual recovery of motor ability, food intake, and water consumption. Animals were housed individually in separate cages within 24 h post-surgery. After the procedure, penicillin was administered for 3 days. One week later, the rats were anesthetized with urethane and underwent urodynamic testing, sneezing tests were carried out to confirm the successful establishment of the model. Immediately after that, the stimulator implantation was performed in both the stimulation and sham groups. A 1-cm incision was made at approximately 0.5–1 cm lateral to the perianal region. The stimulator was inserted near the pubococcygeus muscle to a depth of about 2 cm, with the anode end facing outward and the cathode end inward. Successful implantation was verified by observing rhythmic anal contractions during stimulation testing. The insertion depth was adjusted by monitoring the force of anal contractions, and the incision was subsequently sutured. The proper implantation position of the stimulator was confirmed via X-ray imaging (Fig. 1D). One week after the implantation, the rats in the stimulation group were anesthetized under isoflurane and placed on the operating table. The RF cushion was positioned horizontally at a 90° angle relative to the stimulator (Fig. 1E). Biphasic pulses (0.2 ms) were used, and the threshold (T) was defined as the minimum intensity to induce visible anal contractions. Stimulation at a frequency of 6 Hz and an intensity of 2 T was applied daily for 30 min for a period of 2 weeks11. After that, the rats were euthanized by cervical dislocation under deep isoflurane anesthesia.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining

Pubococcygeus muscle on the stimulated side and anterior vaginal wall tissues were harvested and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for at least 24 h. After fixation, the tissues were trimmed to the regions of interest and underwent dehydration through a graded ethanol series (75%, 85%, 90%, and 95% ethanol) followed by absolute ethanol and xylene baths. The dehydrated tissues were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned at a thickness of 4 µm using a microtome, and mounted on glass slides. Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated before being stained with Harris hematoxylin for nuclear visualization and eosin for cytoplasmic structures. Following staining, the sections were dehydrated again, cleared with xylene, and mounted with neutral gum. Finally, the stained slides were examined under a light microscope.

Masson’s staining

Specimens were stained with Masson’s staining. For each section, three random fields of view at 200 × magnification were photographed, ensuring that the tissue fully occupied the field and that background illumination remained consistent across all images. Images were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) by applying a standardized blue threshold to identify collagen fibers. The software calculated the percentage of the collagen fiber area relative to the total tissue area for each image.

Electron microscopy

Specimens embedded in methyl methacrylate were sectioned and polished to a thickness of 100 µm before sputter coating. The elemental composition of specific regions of interest was analyzed using a scanning electron microscope equipped with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (HITACHI SU8010, Japan).

Western blot

Proteins were extracted from tissues using pre-chilled RIPA buffer with a protease inhibitor cocktail and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm (4 °C) for 15 min. The supernatant was collected, and protein concentrations were measured using the BCA assay. BCA working solution was prepared by mixing reagents A and B in a 50:1 ratio. Standards were diluted to 0.5 mg/mL, and samples were assayed in duplicate. After adding BCA reagent, plates were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min and absorbance was read at 570 nm. 30 µg of protein per sample was separated on SDS-PAGE gels (8% separation, 5% stacking) and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA-TBST for 1 h and incubated overnight with primary antibodies against MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-9, TIMP1-3, Collagen I, Collagen III, and ACTIN at appropriate dilutions. After washing, membranes were probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and developed using ECL. Bands were visualized and quantified using ImageJ.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Samples were analyzed using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Elabscience Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) following the manufacturer’s protocol, the proteins detected are the same as those detected by WB. Briefly, 100 µL of diluted standards, blanks, and samples were added to designated wells in duplicate and incubated at 37 °C for 90 min. After decanting the unbound substances, 100 µL of biotinylated detection antibody was applied and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The plates were then washed three times with wash buffer. Subsequently, 100 µL of HRP-conjugate was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by five additional washes. Next, 90 µL of substrate reagent was added, and the plates were incubated in the dark for approximately 15 min at 37 °C. After adding 50 µL of stop solution, the optical density was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (version 10.0; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). All data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). One-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons, was used to assess statistical significance (P < 0.05).

Data availability

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author.

References

Landefeld, C. S. et al. National Institutes of Health state-of-the-science conference statement: Prevention of fecal and urinary incontinence in adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 148, 449–458 (2008).

Abufaraj, M. et al. Prevalence and trends in urinary incontinence among women in the United States, 2005–2018. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 225, 161–166 (2021).

Waetjen, L. E., Xing, G., Johnson, W. O., Melnikow, J. & Gold, E. B. Factors associated with reasons incontinent midlife women report for not seeking urinary incontinence treatment over 9 years across the menopausal transition. Menopause-J. N. Am. Menopause Soc. 25, 29–37 (2018).

Bo, K. & Hilde, G. Does it work in the long term?–A systematic review on pelvic floor muscle training for female stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 32, 215–223 (2013).

Sahin, U. K., Acaroz, S., Cirakoglu, A., Benli, E. & Akbayrak, T. Effects of external electrical stimulation added to pelvic floor muscle training in women with stress urinary incontinence: A randomized controlled study. Neurourol. Urodyn. 41, 1781–1792 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Implantable zinc-oxygen battery for in situ electrical stimulation-promoted neural regeneration. Adv. Mater. 35, e2302997 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. Rehabilitation exercise-driven symbiotic electrical stimulation system accelerating bone regeneration. Sci. Adv. 10, eadi6799 (2024).

Maeng, W. Y., Tseng, W. L., Li, S., Koo, J. & Hsueh, Y. Y. Electroceuticals for peripheral nerve regeneration. Biofabrication 14, 042002 (2022).

Long, Y., Li, J., Yang, F., Wang, J. & Wang, X. Wearable and implantable electroceuticals for therapeutic electrostimulations. Adv. Sci. 8, 2004023 (2021).

Li, X., Deng, H., Wang, Z., Li, H. & Liao, L. Safety and effectiveness of nustim system implantation in dogs. Bladder 9, e49 (2022).

Long, B. et al. A potential therapeutic strategy using a miniature, implantable, wireless nerve stimulation device for treating stress urinary incontinence in rats. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 57, 1311–1318 (2024).

Wu, J. M. Stress incontinence in women. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 2428–2436 (2021).

Norton, P. & Brubaker, L. Urinary incontinence in women. Lancet 367, 57–67 (2006).

Koelbl, H., Strassegger, H., Riss, P. A. & Gruber, H. Morphologic and functional aspects of pelvic floor muscles in patients with pelvic relaxation and genuine stress incontinence. Obstet. Gynecol. 74, 789–795 (1989).

DeLancey, J. et al. Pelvic floor injury during vaginal birth is life-altering and preventable: What can we do about it?. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 230, 279–294 (2024).

Ashton-Miller, J. A. & DeLancey, J. O. Functional anatomy of the female pelvic floor. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1101, 266–296 (2007).

Kobayashi, A. J., Sesillo, F. B., Do, E. & Alperin, M. Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on pelvic floor muscle regeneration in a preclinical birth injury rat model. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 230, 431–432 (2024).

Tidball, J. G., Dorshkind, K. & Wehling-Henricks, M. Shared signaling systems in myeloid cell-mediated muscle regeneration. Development 141, 1184–1196 (2014).

Nicholas, J. et al. Time course of chemokine expression and leukocyte infiltration after acute skeletal muscle injury in mice. Innate Immun. 21, 266–274 (2015).

Pietrangelo, L. et al. Age-dependent uncoupling of mitochondria from ca2(+) release units in skeletal muscle. Oncotarget 6, 35358–35371 (2015).

Bratic, A. & Larsson, N. G. The role of mitochondria in aging. J. Clin. Investig. 123, 951–957 (2013).

Leduc-Gaudet, J. P. et al. Mitochondrial morphology is altered in atrophied skeletal muscle of aged mice. Oncotarget 6, 17923–17937 (2015).

Huang, D. D. et al. Nrf2 deficiency exacerbates frailty and sarcopenia by impairing skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics in an age-dependent manner. Exp. Gerontol. 119, 61–73 (2019).

Sebastian, D. et al. Mfn2 deficiency links age-related sarcopenia and impaired autophagy to activation of an adaptive mitophagy pathway. EMBO. J. 35, 1677–1693 (2016).

Romanello, V. The interplay between mitochondrial morphology and myomitokines in aging sarcopenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 91 (2020).

Gan, Z., Fu, T., Kelly, D. P. & Vega, R. B. Skeletal muscle mitochondrial remodeling in exercise and diseases. Cell Res. 28, 969–980 (2018).

Eisner, V., Lenaers, G. & Hajnoczky, G. Mitochondrial fusion is frequent in skeletal muscle and supports excitation-contraction coupling. J. Cell. Biol. 205, 179–195 (2014).

Cai, L., Shi, L., Peng, Z., Sun, Y. & Chen, J. Ageing of skeletal muscle extracellular matrix and mitochondria: finding a potential link. Ann. Med. 55, 2240707 (2023).

Yamano, K. & Youle, R. J. Coupling mitochondrial and cell division. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1026–1027 (2011).

Gelse, K., Poschl, E. & Aigner, T. Collagens–structure, function, and biosynthesis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 55, 1531–1546 (2003).

Kuivaniemi, H. & Tromp, G. Type iii collagen (col3a1): gene and protein structure, tissue distribution, and associated diseases. Gene 707, 151–171 (2019).

Gong, R. & Xia, Z. Collagen changes in pelvic support tissues in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 234, 185–189 (2019).

Jackson, S. R. et al. Changes in metabolism of collagen in genitourinary prolapse. Lancet 347, 1658–1661 (1996).

Campeau, L., Gorbachinsky, I., Badlani, G. H. & Andersson, K. E. Pelvic floor disorders: linking genetic risk factors to biochemical changes. BJU Int. 108, 1240–1247 (2011).

Zhang, W., Liu, Y. & Zhang, H. Extracellular matrix: an important regulator of cell functions and skeletal muscle development. Cell Biosci. 11, 65 (2021).

Rayagiri, S. S. et al. Basal lamina remodeling at the skeletal muscle stem cell niche mediates stem cell self-renewal. Nat. Commun. 9, 1075 (2018).

Naba, A. Mechanisms of assembly and remodelling of the extracellular matrix. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 865–885 (2024).

de Almeida, L. et al. Matrix metalloproteinases: from molecular mechanisms to physiology, pathophysiology, and pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev. 74, 712–768 (2022).

Kushner, L., Mathrubutham, M., Burney, T., Greenwald, R. & Badlani, G. Excretion of collagen derived peptides is increased in women with stress urinary incontinence. Neurourol. Urodyn. 23, 198–203 (2004).

Acknowledgements

Figure 8E support was provided by Figdraw

Funding

This study was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3606003), the Cooperative Project of China Rehabilitation Research Center (2021HZ-08), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7222235) and the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Public Welfare Research Institutes, conducted by China Rehabilitation Science Institute (CRSI2025QB-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: BHL, HD, XL, HYS, CL. Methodology: HYS, BHL, HD, XL. Investigation: HYS, BHL, HD. Visualization: CL, BHL. Supervision: XL, LML. Writing—original draft: CL. Writing—review & editing: CL, XL All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Long, B., Deng, H. et al. Implantable electrical stimulation device enhances pelvic floor tissue repair and reduces collagen over-degradation in rats with stress urinary incontinence. Sci Rep 15, 31354 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16162-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16162-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Effects of pelvic floor electrical stimulation with an implantable device at different frequencies on stress urinary incontinence in rats

European Journal of Medical Research (2025)