Abstract

We aimed to assess the prevalence of high-risk HPV (hr-HPV) infection, cervical lesions observed through visual inspection, and abnormal cytology among women aged ≥ 60 years screened by the Cervical Cancer Prevention and Training Centre, Ghana. We further compared screening outcomes between women aged ≥ 60 and ≥ 65 years to assess the implications of applying these age cut-offs for screening cessation. Among 1,319 women screened, the overall mean ages were 66.7 and 71.2 years among ≥ 60- and ≥ 65-year-olds, respectively. The overall prevalence of hr-HPV infection was 27.9% (95% CI, 25.1 − 31.0), with a higher prevalence among ≥ 65-year-olds (30.8%; 95% CI, 26.6 − 35.2). Visual inspection ‘positivity’ rates were 1.9% (95% CI, 1.2 − 2.8) among ≥ 60-year-olds and 1.9% (95% CI, 1.0 − 3.2) among ≥ 65-year-olds. Cytology revealed ASCUS or worse lesions in 8.6% (95% CI, 1.8 − 23.1). Factors independently associated with hr-HPV infection among all women aged ≥ 60 included HIV co-infection (aOR, 4.12; 95% CI, 2.48 − 6.84), age (aOR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00 − 1.05), parity (aOR, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02 − 1.14), and earning an income (aOR, 1.54; 95% CI, 1.10 − 2.15). In the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup, these associations were attenuated, except for HIV infection (aOR, 4.20; 95% CI, 2.07 − 8.49; p-value < 0.001). Among histopathologically-confirmed CC cases, 39.1% (95% CI, 31.7 − 46.8) were ≥ 60-year-olds, while 25.4% (95% CI, 19.1 − 32.7) were ≥ 65-year-olds. The study indicates a higher prevalence of hr-HPV infection among older women compared to community-dwelling younger women, with similar rates of cervical lesions on colposcopy. Given the increasing life expectancy in Ghana, the population of older women at risk for CC is expected to grow. Therefore, it is premature to recommend age-based cessation of cervical precancer screening in older women in Ghana. The context of limited access to screening and the opportunistic nature of screening, supports a more conservative approach to CC prevention among older women, particularly those living with HIV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cervical cancer (CC) is the fourth most prevalent female malignancy and its rising prominence courts public health concerns, particularly in settings with limited access to vaccination, screening, and management facilities. Globally, approximately 85% of all CC-related deaths and 83% of new cases occur in resource-constrained areas1,2,3. In 2013, women aged 65 years or older composed one-third of CC deaths and one-fifth of new cases4. Among typical risk groups aged 21 to 65 years, CC is highly avertable with routine vaccination and precancer screening with cervical cytology, human papillomavirus (HPV) DNA testing, colposcopy, and Visual Inspection with Acetic acid (VIA)2,4. The World Health Organization (WHO) screening guidelines recommend an HPV DNA test every five to ten years for the timely identification of cervical premalignant lesions5,6,7asserting that screening should be targeted at women aged 30 − 49 years and cease at age 50 after two consecutive negative screening results5. This is because VIA and ablative treatment are not appropriate for screening or treating menopausal women whose transformation zones (TZs) cannot be typically visualized5. Nonetheless, those aged 50 − 65 years who have particularly never been screened should be prioritized when resources are available for management5.

When three consecutive negative cytology results or two consecutive negative co-test results occur within the preceding ten years, with the most recent test taken within the last five years, average-risk women aged 60 − 65 years may be exempted from routine screening in most high-resource countries4,8,9,10. For women older than 65 years, the American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and American Cancer Society propose discontinuing cervical precancer screening as long as no prior dysplasia was detected in the previous ten years11. Ceasing cervical precancer screening in older women is also based on the presumption that HPV infections in women of advanced age are uncommon, and unlikely to persist long enough to become malignant or invasive12. This low prevalence of high-risk HPV (hr-HPV) among women aged ≥ 55 years and the rationale that the risks of continuing screening may outweigh the potential benefits often justify the cessation of screening in older women; however, there is no conclusive evidence about the circumstances and the upper age to quit screening8.

There is also strong evidence that Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN) have a higher tendency to progress to invasive CC in the aged10. Therefore, screening in the sixties is still advised, typically for women who are at a special risk or do not meet the adequate screening criteria13. It was recently shown that the incidence and mortality rates of CC in women over 65 were 80% greater than previously thought14. Appropriate screening at ages 50–64 is associated with a significantly decreased risk of CC after age 65 4; thus, it is beneficial to increase screening uptake before age 65 and, if necessary for catch-up, after age 6513.

Our recent institutional experience with screening among older women aged ≥ 60 years suggests that this cohort may be at an increased risk of high-grade squamous lesions. Due to the lack of an organized cervical precancer screening program in Ghana, screening for most women is largely opportunistic. Thus, most women, regardless of their age, never get screened or meet the requisite number of prior screens required to properly apply the age-based recommendations for screening cessation put forward by the aforementioned international societies and organizations.

To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has evaluated the risk of CC among older women in Ghana, nor critically appraised age-based recommendations for cervical precancer screening cessation. Bearing in mind that the post-recommendation age-related risks of older women are unknown, this study aimed to assess the prevalence of hr-HPV infection, cervical lesions (observed on visual inspection methods), and abnormal cytology among older women aged ≥ 60 years screened by the Cervical Cancer Prevention and Training Centre (CCPTC), Catholic Hospital, Battor. Secondarily, we sought to compare the screening outcomes among all women ≥ 60 years and a subgroup aged ≥ 65 years (hereafter, the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup) in order to assess the hypothetical implications of applying these cut-off ages for cessation of cervical precancer screening. Specific to all women ≥ 60 years (and the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup) screened using hr-HPV DNA testing, we further modeled and compared factors associated with hr-HPV infection that could potentially influence the decision to prioritize screening at these cut-offs.

Methods

Study design

We conducted this secondary data analysis of all women aged ≥ 60 years who underwent cervical precancer screening with the primary aim of examining the prevalence of hr-HPV infection, abnormal cytology [atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) or worse, according to the 2001 Bethesda System Classification], and cervical lesions [observed on visual inspection procedures: Enhanced Visual Assessment (EVA) mobile colposcopy and/or VIA]. Our secondary aim was to compare screening outcomes among all older (aged ≥ 60-year-old) women screened and the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup to assess the implications of ceasing screening based on both cut-offs. Among all women in the overall sample and the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup who were screened using hr-HPV DNA-based techniques, our tertiary aim was to model and compare factors associated with hr-HPV infection that could potentially inform resource prioritization of women with such characteristics should either age be selected as the cut-off for cervical precancer cessation.

Study setting and participants

The study participants (n = 1,319) were otherwise asymptomatic women screened between May 2016 and May 2024 by the CCPTC team either at the clinic or on outreaches, and as part of the Ghana arm of the mPharma 10,000 Women Initiative15,16 during which supervised alumni of the CCPTC training program17,18 screened women in their respective practice areas across Ghana. For each woman, screening was performed using various combinations of the three main modalities: (1) standalone testing [hr-HPV DNA testing alone, or visual inspection (EVA mobile colposcopy or VIA alone), or cytology (Pap smear) alone]; (2) concurrent testing [hr-HPV DNA testing with VIA and/or EVA mobile colposcopy in a single visit]; or (3) tritesting [all three modalities performed in a single visit].

Ethical considerations

This research is a retrospective analysis of data collected during routine clinical screening. The study protocol for this retrospective analysis, including the plan to publish the findings, was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Catholic Hospital, Battor (approval no. CHB-ERC 002/01/24). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all women for the collection of their data and samples during their clinical screening. The need for formal written informed consent was waived by the Ethics Review Committee of Catholic Hospital, Battor, due to the retrospective nature of the study. Participant confidentiality and data security were maintained throughout the study by anonymizing all information and storing it on a password-protected computer.

Sample size

No a priori statistical power calculation was conducted prior to this study because it represents a retrospective analysis of a complete clinical cohort19. Therefore, the sample size was determined by the total number of eligible women aged ≥ 60 years who were screened by the CCPTC between May 2016 and May 2024 and had their data entered into the center’s electronic database. There was also limited evidence on the risk of cervical precancer and cancer among older women in Ghana that would ideally have served as a basis for such a calculation.

Data collection, management, and curation

Regardless of the setting or choice of approach at the time of screening, data collection was performed using a structured health worker-administered questionnaire designed by the CCPTC for routine use in its clinical activities and outreaches for data capturing. Prior to administering the questionnaire, the health worker educated each woman privately, answering any question(s) she might have, after which verbal informed consent was obtained. All data were then captured into REDCap version 11.0.3 (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA)20 and stored in secure databases hosted at the CCPTC. Once screening findings or results (for any procedure) or histopathology results had become available, they were matched with the corresponding participant using unique identification numbers assigned at the time of screening. After designing the study and specifying the objectives, the data were curated via querying, extraction into a spreadsheet, and manually cross-checking for errors. To ensure the privacy and anonymity of the participants, all data were de-identified before transmission for the analyses.

Study variables and outcomes of interest

At the time of screening, we collected data pertaining to sociodemographic characteristics, including age, age at menarche, highest education level, marital status, and parity. Clinical data potentially related to the risk of CC were also collected, including information on current and past contraceptive use, ever/current smoking status, as well as HIV status. Based on the previously mentioned modalities implemented at screening, our primary outcomes of interest were a positive hr-HPV DNA test, a finding of ASCUS or worse on Pap smear, or the presence of major (and minor) changes on visual inspection (VIA or EVA mobile colposcopy).

Cervical specimen collection for hr-HPV DNA testing and pap smear

Cervical sample collection for hr-HPV testing and Pap smear for cytology were performed with the woman lying in the dorsal lithotomy position, after which a sterile vaginal speculum was placed to expose the cervix. The decision to use liquid-based or conventional cytology was made prior to screening based on the kit available at the time. Pap smears for liquid-based cytology were obtained with a Cervex-Brush® (Rovers Medical Devices BV, Oss, Netherlands) and fixed in PreservCyt (ThinPrep). Pap smears for conventional cytology were obtained with an Ayre spatula and cytobrush, smeared on a glass slide, and fixed using 92% alcohol. After collection, Pap smears were sent to a pathologist at a tertiary center about 100 km away from the CCPTC since our center does not have an in-house cytotechnologist. All results were made available within two weeks. Cervical samples for hr-HPV DNA testing were obtained with either a cytobrush or cotton-tipped applicator (depending on their availability), placed in a plain sample collection tube, and sent to the central laboratory of the Catholic Hospital, Battor for testing.

Cervical visual inspection procedures

Trained health workers performed VIA as per standard protocol by applying 5% acetic acid to the ectocervix, watching for the presence or appearance of acetowhitening at the TZ, and making a final decision/comment after 90–120 s. EVA mobile colposcopy was performed using the EVA system (MobileODT, Tel Aviv, Israel) which is built into a smartphone device and operated through an app. Colposcopic images were captured before and after acetic acid application, often for quality assurance purposes. In keeping with the 2011 International Federation of Cervical Pathology and Colposcopy (IFCPC) nomenclature21,22findings on both VIA and EVA mobile colposcopy were recorded and reported. TZ types were classified as follows: type 1, if the entire squamocolumnar junction (SCJ) circumference could be visualized (entirely ectocervical); type 2, if the entire SCJ circumference was visible (partially or fully endocervical); or type 3, if the SCJ could not be visualized (partially or entirely endocervical)21. The outcomes of EVA mobile colposcopy or VIA were described as positive if acetowhite lesions were observed at the TZ or any clinically significant lesions were seen; otherwise, the outcome was described as ‘negative’.

Laboratory processing of cervical samples for hr-HPV DNA testing

The choice of test platform for hr-HPV DNA testing depended on the time of screening, and therefore the platform predominantly being used at the Central Laboratory, Catholic Hospital, Battor at that time. Study participants who underwent HPV testing were screened using one of the following platforms: careHPV (Qiagen GmBH, Hilden, Germany), GeneXpert HPV system (Cepheid, Sunnyvale, CA, USA), AmpFire HPV system (Atila BioSystems, Inc., Mountain View, USA), or MA-6000 HPV assay system (Sansure Biotech Inc., Hunan, China). All tests were run in strict compliance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Details of these protocols have been previously published elsewhere23,24,25,26,27. In terms of genotype identification, careHPV qualitatively detects HPV 16/18/31/33/35/39/45/51/52/56/58/59/66/68 (not individually) while GeneXpert specifically detects HPV16 and 18/45, while qualitatively detecting HPV31/33/35/39/51/52/56/58/59/66/68 as other hr-HPV type(s). The semi-quantitative modules of both the AmpFire and MA-6000 systems, which were used, specifically detect HPV16 and HPV18, while qualitatively detecting HPV31/33/35/39/45/51/52/53/56/58/59/66/68 as other hr-HPV type(s).

Statistical methods

We employed Q − Q plots, histograms, and the Shapiro − Wilk test to assess the distributions of continuous and discrete data such as age and number of lifetime pregnancies/births. Such data are reported as means and standard deviations (SDs) if found to have a normal distribution or as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) if skewed. Categorical characteristics are reported as frequencies and percentages. Positivity rates recorded on each screening modality [cytology, visual inspection (VIA and EVA), and hr-HPV DNA testing] are reported as proportions, with 95% Clopper − Pearson confidence intervals (CIs) constructed to assess uncertainty around each point estimate. By way of comparison, this was done for the entire group and separately for the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup. We also compared the TZ type distributions identified by CCPTC staff vs. alumni considering both cut-offs using Pearson’s chi-squared test of independence.

We then fit two univariable and multivariable nominal logistic regression models looking for factors associated with hr-HPV infection, one for the whole group and another for the ≥ 65-year-old group. Variables with < 10% missing data were handled using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) with ten iterations because they were found to be missing completely at random, such that this approach would be unbiased. The results of the MICE were combined according to Rubin’s rules. Apart from age which was forced into the adjusted analyses, each multivariable model was adjusted using only variables found to be statistically significant in the univariable analyses. Effect estimates from the logistic regression models are reported as odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted ORs (aORs), each with their 95% CIs. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 18.5 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA). All hypothesis tests were two-tailed and considered statistically significant at p-value < 0.05.

Results

Participant selection and dispositions

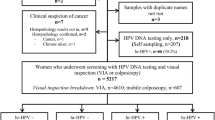

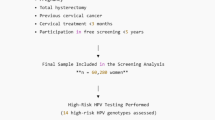

Flow charts illustrating participant selection, screening, and dispositions are shown in Figs. 1 − 4. In all, 1,319 women aged ≥ 60 consented to be screened during the study period and were included in the study. Among them, 700 (53.1%) belonged to the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup. In terms of the test combinations used among all participants, concurrent testing with HPV testing + VIA was most frequently used in n = 690 (52.3%), followed by any form of standalone testing (n = 489, 37.1%), concurrent testing with HPV testing + EVA mobile colposcopy (n = 106, 8.0%), tritesting (n = 30, 2.3%), Pap smear + VIA (n = 3, 0.2%), and Pap smear + EVA (n = 1, 0.1%). Similar proportions of test use were recorded in the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup: 51.0% for HPV testing + VIA, 40.0% for standalone testing, 7.0% for HPV + EVA mobile colposcopy, 1.7% for tritesting, and 0.1% each for Pap + VIA and Pap + EVA mobile colposcopy.

Flow charts showing the dispositions and outcomes for all women aged ≥ 60 years (blue) and the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup (red) who underwent cervical precancer screening using a standalone method. CaCx, cervical cancer; EVA, Enhanced Visual Assessment; hr-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus; VIA, Visual Inspection with Acetic acid.

Flow charts showing the dispositions and outcomes for all women aged ≥ 60 years (blue) and the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup (red) who underwent cervical precancer screening using (A) Pap smear + EVA mobile colposcopy and (B) Pap smear + VIA. EVA, Enhanced Visual Assessment; VIA, Visual Inspection with Acetic acid.

Flow charts showing the dispositions and outcomes for all women aged ≥ 60 years (blue) and the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup (red) who underwent cervical precancer screening using concurrent (A) hr-HPV DNA testing + EVA mobile colposcopy and (B) hr-HPV DNA testing + VIA. EVA, Enhanced Visual Assessment; hr-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus; VIA, Visual Inspection with Acetic acid.

Flow charts showing the dispositions and outcomes for all women aged ≥ 60 years (blue) and the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup (red) who underwent cervical precancer screening using tritesting (hr-HPV DNA testing + visual inspection method [EVA/VIA] + cytology). EVA, Enhanced Visual Assessment; hr-HPV, high-risk human papillomavirus; VIA, Visual Inspection with Acetic acid.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the women

Selected social, demographic, and clinical details of all the study participants (and the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup) are summarized in Table 1. The overall mean age at screening was 66.7 years (SD, 6.7) (95% CI, 66.3 − 67.1) and 71.2 years (SD, 6.4) (95% CI, 70.7 − 71.7) in the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup. The participants had experienced a median of 5 (IQR: 3, 6) lifetime pregnancies and 1 (IQR: 0, 2) live births. Twenty-six (2.0%) had a history of abnormal vaginal discharge at screening, while 14 (1.1%) had experienced postmenopausal bleeding and 12 (0.9%) had a history of postcoital bleeding. In terms of marital status, they were most commonly widowed (n = 469, 35.6%) or married (n = 464, 35.2%). A small minority (n = 3, 0.2%) had ever smoked and 10 (0.8%) regularly used alcohol. At the time of screening, 119 (9.0%) underwent HIV tests; overall, 118 (9.0%) were either confirmed or self-reported being HIV positive. None (0.0%) had ever received an HPV vaccine and 9.6% (n = 127) had undergone prior cervical precancer screening.

Screening characteristics and outcomes among the study participants

Findings recorded on gross genital examination and outcomes of cervical precancer screening among all ≥ 60-year-olds (and the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup) are summarized in Table 2. Gross examination revealed abnormal vulval inspection findings in 6 (0.5%) of all ≥ 60-year-olds and 4 (0.6%) of ≥ 65-year-olds, while abnormal vaginal findings were identified in 6 (0.5%) of all ≥ 60-year-olds and 3 (0.4%) of ≥ 65-year-olds. Abnormal cervical inspection findings were recorded in 23 (1.9%) ≥ 60-year-olds and 5 (0.8%) ≥ 65-year-olds. A TZ type 3 was found in a large majority of the study participants (n = 1103, 83.6%).

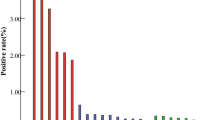

The overall prevalence of hr-HPV infection found among all participants was 27.9% (95% CI, 25.1 − 31.0) with much higher prevalence in the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup (30.8%; 95% CI, 26.6 − 35.2) but significantly overlapping CI. The platform-specific prevalence estimates of hr-HPV infection were 23.9% (95% CI, 12.6 − 38.8) for careHPV, 25.9% (95% CI, 15.0 − 39.7) for AmpFire, and 48.1% (95% CI, 43.2 − 53.0) for MA-6000.

The visual inspection ‘positivity’ rates were 1.9% (95% CI, 1.2 − 2.8) and 1.9% (95% CI, 1.0 − 3.2) among all ≥ 60-year-olds and in the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup, respectively. The VIA-specific ‘positivity’ rates were 0.6% (95% CI, 0.3 − 1.4) and 0.7% (95% CI, 0.2 − 1.8) among all ≥ 60-year-olds and in the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup, respectively, whereas the EVA-specific ‘positivity’ rates were 9.7% (95% CI, 5.6 − 15.3) and 10.1% (95% CI, 4.5 − 19.0) among all ≥ 60-year-olds and in the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup, respectively.

Cytology revealed findings of ASCUS or worse in 8.6% (95% CI, 1.8 − 23.1) among all participants.

Comparison of TZ type distribution between CCPTC staff vs. alumni

Cervical examinations conducted by CCPTC alumni were associated with a higher detection of TZ types 1 and 2 compared to those performed by CCPTC staff (Table 3) (chi-squared tests of contingency, p-value < 0.001). Specifically, for women aged ≥ 60 years, among CCPTC staff, 0.5% of examinations were classified as TZ type 1 and 2.4% as type 2, with a majority 97.1% classified as type 3. In contrast, CCPTC alumni reported significantly higher proportions of TZ types 1 (4.0%) and 2 (12.1%), with a correspondingly lower frequency of type 3 (83.9%). A similar pattern was observed in the subgroup of women aged ≥ 65 years. CCPTC staff examinations showed 0.7% TZ type 1 and 2.6% type 2, with type 3 constituting 96.7% of cases. Examinations performed by CCPTC alumni, however, yielded 4.0% TZ type 1 and 14.4% type 2, while type 3 was noted in 81.6% of cases.

Exploratory analysis of factors associated with hr-HPV infection among older women

The results of the univariable and multivariable exploratory logistic regression analyses seeking factors associated with hr-HPV infection among the study participants are shown in Table 4. In the univariable analyses, each unit increase in parity was found to increase the odds of hr-HPV infection by approximately 8–9%, showing OR = 1.09 (95% CI, 1.03 − 1.14) among all ≥ 60-year-olds and OR = 1.08 (95% CI, 1.01 − 1.15) among ≥ 65-year-olds. Similarly, HIV-positive older women showed 4-fold higher odds of hr-HPV infection, showing OR = 4.11 (95% CI, 2.51 − 6.74) among all ≥ 60-year-olds and OR = 4.26 (95% CI, 2.12 − 8.57) among ≥ 65-year-olds. In the adjusted analyses, the following factors showed statistically independent associations with hr-HPV infection among all ≥ 60-year-old women: HIV infection (aOR = 4.12; 95% CI, 2.48 − 6.84; p-value < 0.001), age (aOR = 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00 − 1.05; p-value = 0.024), parity (aOR = 1.08; 95% CI, 1.02 − 1.14; p-value = 0.007), and earning an income (aOR = 1.54; 95% CI, 1.10 − 2.15; p-value = 0.012). All the aforementioned multivariable associations were attenuated in the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup, except HIV infection, which continued to show an aOR = 4.20 (95% CI, 2.07 − 8.49; p-value < 0.001).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first to evaluate the prevalence of abnormal outcomes at cervical screening among older women in Ghana. Drawing from a large database of screening information meticulously collected between 2016 and 2024, we further examined these outcomes among women aged ≥ 60 years and in a ≥ 65-year-old subgroup in order to look into the potential implications of applying each of these cut-offs as cessation thresholds for cervical precancer screening in older women. Again, we assessed factors associated with hr-HPV infection that would potentially inform further studies for prioritizing continued access to screening and surveillance among older women in Ghana. Briefly, we found an overall hr-HPV point prevalence of 27.9% and 30.8% in the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup, with a significant overlap in 95% CI when considering the two groups as independent. The point prevalence of cervical lesions on any visual inspection method was 1.9% both overall and in the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup. The respective breakdowns were 0.6% and 0.7% for VIA and 9.7% and 10.1% for EVA mobile colposcopy. The overall prevalence of ASCUS or worse was 8.6%. In the overall group, informative factors independently associated with hr-HPV infection were HIV co-infection, age, parity, and earning an income. In the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup all other associations were attenuated, except for HIV co-infection which maintained an adjusted 4-fold higher-odds association with hr-HPV infection. Of particular interest, we recorded a zero rate of HPV vaccination and an approximately 10% rate of prior cervical screening utilization.

The hr-HPV positivity rates observed among all participants and the ≥ 65-year-old subgroup were higher than reported in a separate cohort of women screened at an outpatient clinic setting in Accra (10.7%)28. The rates were again much higher than the rates of 17.9%29 we found in a prior cohort of women in the general population screened using concurrent testing (hr-HPV DNA testing and a visual inspection method) with the same procedures and test platforms applied in this study. It is worth noting that women in this study were much older (mean age, 67 years) than women screened in these two aforementioned studies, who were in their mid to late thirties. The low rate of VIA ‘positivity’ compared to that recorded in the latter group of concurrently tested women29 (2.1%) given the much higher rate of EVA positivity may indicate a suboptimal performance of this tool when used for screening in postmenopausal women, given the effects of hypoestrogenism on the TZ.

The maximum age at which cervical precancer screening can be stopped remains an area of controversy in many countries with varying policies30,31. Evidently, one of the most prominent points emphasized among guidelines recommending an age cut-off is how adequately women in a population have participated in screening32. While developed countries like the United States and the United Kingdom have demonstrated participation rates as high as 70% and 63%, respectively33participation remains suboptimal at 2.4–2.7% in Ghana34,35. In this regard, and considering that prior screening utilization in our study was approximately 10%, it would be premature to limit cervical precancer screening in older women in a country with such a low screening attendance rate relative to the settings from which these recommendations have originated. Due to the increasing incidence of CC and its associated mortality in countries like Korea, the target age for screening cessation had to be increased to 74 for women who had consecutively screened negative in the prior 10-year period and without a diagnosis of CIN2 + in the preceding 20 years36. Similarly, Australia had to extend the age ceiling from 69 to 74 years; however, the guidelines continue to recommend screening for older women who have previously screened positive or had not been screened in the preceding 5 years37.

Another point that needs emphasis when considering an age ceiling for cervical precancer screening is the life expectancy of women in the population38. Ghana has chalked remarkable success in terms of an increased life expectancy among both sexes, with a relatively higher increase in life expectancy at birth among females from 59.3 years in 2000 to 67.8 years in 2024; this is forecasted to reach 72.3 years by 205039. Thus, hypothetically, ignoring the issue of adequate participation in screening, and assuming that organized screening was immediately made available across Ghana, the average woman would live at least 7.8 years beyond our lower threshold of 60 years considered in this study–the risk of missing precancers during this time cannot be ignored. Again, incident cases of CC have been reported to show a bimodal distribution, peaking at 30 − 39 and 60 − 69 years40. In 2020, 604,127 women globally were diagnosed with CC41among whom 22% were older than 65 years. Our institutional data collected between 2015 and 2021, were not too dissimilar: a total of n = 169 cases of histopathologically confirmed CC presented to the parent facility of the CCPTC (Catholic Hospital, Battor). Among these, 39.1% were ≥ 60-year-olds and 25.4% were ≥ 65-year-olds. CC is clearly neither a disease of younger women globally nor in Ghana. The high HPV positivity rate (48.1%) using the MA6000 platform compared to the other platforms (careHPV, GeneXpert, AmpFire) may be explained by the fact that the MA6000 might have been used for a higher risk cohort in the mPharma 10,000 women initiative, which prioritized higher risk women who otherwise could not afford screening with hr-HPV DNA testing.

The higher proportion of TZ type 3 findings among CCPTC staff (compared to alumni) could indicate that more experienced examiners are better at recognizing that, in older women, the SCJ often recedes deeper into the endocervical canal42. As a result, they may be more likely to classify the TZ as type 3 (i.e., not fully visible and extending into the cervical canal). Less experienced examiners might label a borderline or partially visible zone as type 1 or 2 because they are less confident in delineating the true position of the SCJ22. Stated differently, examiners who have performed many colposcopic evaluations on older patients may be more adept at judging when the TZ is no longer fully visible, whereas newer or less experienced practitioner may inadvertently categorize the same findings as a type 1 or 2 TZ. This difference in classification could reflect the subtle differences in performing and interpreting cervical examinations in older age groups, and thus the importance of experience and familiarity with the receded TZ that occurs with advancing age. This might influence clinical management decisions, particularly in determining eligibility for ablative vs. excisional treatment43.

Strengths and limitations

This study adds to the discourse on critical appraisals of age-based recommendations for cervical precancer screening cessation. A key strength is the inclusion of a large, real-world cohort, representing a census of older women who underwent screening at our center, which enhances the generalizability of our findings to similar settings in Ghana. The relatively large sample size also enabled us to stratify both prevalence and detection rates among the age strata and screening methods without loss of statistical power. However, the study had several limitations based on which future studies can improve to influence cervical screening policy in Ghana and similar resource-limited settings. First, due to financial and logistical reasons, we could not perform full genotyping for the participants to distinguish among recognized, probable, and potential hr-HPV genotypes. We could also neither distinguish between persistent and transient hr-HPV infections nor perform HIV screening for all women at screening. Last, data on certain hr-HPV-related cofactors such as sexual activity among women in this study could not be collected.

Conclusions

Our study points to a higher prevalence of hr-HPV infection among older women compared to previously studied groups of younger women in the general population, with a similar prevalence of cervical lesions on colposcopy (despite lower prevalence on VIA). Given that a significant proportion of all histologically-confirmed CC cases seen at our institution were recorded among older women (considering both age cut-offs), and that the life expectancy among females at birth in Ghana is rapidly increasing, the population of older women at risk of developing and succumbing to CC is expected to grow. This, together with the low prior participation rate makes it premature to recommend either of these age cut-offs for cervical precancer screening cessation among older women in Ghana. While this might make sense in developed countries given the compelling epidemiology of CC development, gaps in access and the prevailing opportunistic nature of screening in Ghana support a more conservative approach to CC prevention among older women, particularly those living with HIV.

Data availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available, upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

World Health Organization. Cervical cancer. (2024). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cervical-cancer

Chatterjee, S., Chattopadhyay, A., Samanta, L. & Panigrahi, P. HPV and cervical cancer Epidemiology - Current status of HPV vaccination in India. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 17, 3663–3673 (2016).

Albert, S., Oguntayo, O. & Samaila, M. Comparative study of visual inspection of the cervix using acetic acid (VIA) and Papanicolaou (Pap) smears for cervical cancer screening. Ecancermedicalscience 6, 262 (2012).

White, M. C., Shoemaker, M. L. & Benard, V. B. Cervical cancer screening and incidence by age: unmet needs near and after the stopping age for screening. Am. J. Prev. Med. 53, 392–395 (2017).

World Health Organization. WHO Guideline for Screening and Treatment of Cervical Pre-Cancer Lesions for Cervical Cancer Prevention (World Health Organization, 2021).

Tuncer, H. A. & Tuncer, S. F. The effect of age on cervical cancer screening in women aged 20–29. Acta Clin. Croat. 59, 277–284 (2020).

Akshatha, C., Arul, P. & Shetty, S. Prevalence and comparison of cervical cytology abnormalities in postmenopausal and elderly women: A experience from tertiary care hospital. J. Med. Soc. 31, 23 (2017).

Tranberg, M. et al. Expanding the upper age limit for cervical cancer screening: a protocol for a nationwide non-randomised intervention study. BMJ Open. 10, e039636 (2020).

Castañón, A., Landy, R., Cuzick, J. & Sasieni, P. Cervical screening at age 50–64 years and the risk of cervical cancer at age 65 years and older: population-based case control study. PLoS Med. 11, e1001585 (2014).

Rebolj, M. et al. Incidence of cervical cancer after several negative smear results by age 50: prospective observational study. BMJ 338, b1354 (2009).

Levine, E., Ginsberg, N. & Fernandez, C. Age and cervical cancer screening recommendations. Med Res. Arch. 9, (2021).

Tranberg, M., Jensen, J. S., Bech, B. H. & Andersen, B. Urine collection in cervical cancer screening – analytical comparison of two HPV DNA assays. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 926 (2020).

Rosenblatt, K. A., Osterbur, E. F. & Douglas, J. A. Case-control study of cervical cancer and gynecologic screening: A SEER-Medicare analysis. Gynecol. Oncol. 142, 395–400 (2016).

Lichter, K. E., Levinson, K., Hammer, A., Lippitt, M. H. & Rositch, A. F. Understanding cervical cancer after the age of routine screening: characteristics of cases, treatment, and survival in the united States. Gynecol. Oncol. 165, 67–74 (2022).

Effah, K. Rounding off the mPharma 10,000 women initiative in Ghana. https://drkofieffah.com/rounding-off-the-mpharma-10000-women-initiative-in-ghana/ (2022).

mPharma Ghana. The 10,000 Women Initiative. accessed on February 18, (2025). https://wellness.mpharma.com/hpv

Effah, K. et al. A revolution in cervical cancer prevention in Ghana. Ecancer. med. Sci. 16, ed123 (2022).

Effah, K. et al. Mobile colposcopy by trained nurses in a cervical cancer screening programme at battor, Ghana. Ghana. Med. J. 56, 141–151 (2022).

Vandenbroucke, J. P. et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 4, e297 (2007).

Harris, P. A. et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J. Biomed. Inf. 42, 377–381 (2009).

Zhang, B., Hong, S., Zhang, G. & Rong, F. Clinical application of the 2011 IFCPC colposcope terminology. BMC Womens Health. 21, 1–9 (2021).

Effah, K., Tekpor, E., Wormenor, C. M. & Essel, N. O. M. Transformation zone types: a call for review of the IFCPC terminology to embrace practice in low-resource settings. Ecancermedicalscience 17, (2023).

Sansure Biotech. Sansure Biotech MA-6000 PCR System-Final | Enhanced Reader. https://www.sansureglobal.com/product/ma-6000-real-time-quantitative-thermal-cycler/

Thi, N. et al. Evaluation of GeneXpert MTB/RIF for diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis. (2014). https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.01834-13

Katanga, J. et al. Performance of carehpv, hybrid capture 2 and visual inspection with acetic acid for detection of high-grade cervical lesion in tanzania: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 14, e0218559 (2019).

Juliana, N. C. A. et al. Detection of high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) by the novel AmpFire isothermal HPV assay among pregnant women in Pemba island, Tanzania. Pan Afr. Med. J. 37, 1–10 (2020).

Effah, K. et al. Comparison of the AmpFire and MA-6000 polymerase chain reaction platforms for high-risk human papillomavirus testing in cervical precancer screening. J. Virol. Methods. 114709 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2023.114709 (2023).

Domfeh, A. B. et al. Cervical human papillomavirus infection in accra, Ghana. Ghana. Med. J. 42, 71–78 (2008).

Effah, K. et al. Concurrent HPV DNA testing and a visual inspection method for cervical precancer screening: A practical approach from battor, Ghana. PLOS Global Public. Health. 3, e0001830 (2023).

Akanda, R., Kawale, P. & Moucheraud, C. Cervical cancer prevention in africa: A policy analysis. J. Cancer Policy. 32, 100321 (2022).

Dilley, S., Huh, W., Blechter, B. & Rositch, A. F. It’s time to re-evaluate cervical cancer screening after age 65. Gynecol. Oncol. 162, 200–202 (2021).

Fontham, E. T. H. et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American cancer society. CA Cancer J. Clin. 70, 321–346 (2020).

Firtina Tuncer, S. & Tuncer, H. A. Cervical cancer screening in women aged older than 65 years. J. Low Genit. Tract. Dis. 27, 207–211 (2023).

Osei, E. A. & Ani-Amponsah, M. Ghanaian women’s perception on cervical cancer threat, severity, and the screening benefits: A qualitative study at Shai Osudoku district, Ghana. Public. Health Pract. (Oxf). 3, 100274 (2022).

Calys-Tagoe, B. N. L., Aheto, J. M. K., Mensah, G., Biritwum, R. B. & Yawson, A. E. Cervical cancer screening practices among women in ghana: evidence from wave 2 of the WHO study on global ageing and adult health. BMC Womens Health. 20, 49 (2020).

Min, K. J. et al. The Korean guideline for cervical cancer screening. J. Gynecol. Oncol. 26, 232 (2015).

Australian Government & Department of Health and Aged Care. National Cervical Screening Program. https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/national-cervical-screening-program

Grad, R. et al. Age to stop? Appropriate screening in older patients. Can. Fam Physician. 65, 543–548 (2019).

United Nations Population Division. Ghana: Life expectancy at birth, females (years). http://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=PopDiv&f=variableID%3a67

Quick, A. M., Krok-Schoen, J. L., Stephens, J. A. & Fisher, J. L. Cervical cancer among older women: analyses of surveillance, epidemiology and end results program data. Cancer Control. 27, 1073274820979590 (2020).

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figs. 2020 (American Cancer Society, 2020).

Cremer, M. et al. Adequacy of visual inspection with acetic acid in women of advancing age. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 113, 68–71 (2011).

Desai, K. T. et al. Squamocolumnar junction visibility, age, and implications for cervical cancer screening programs. Prev. Med. (Baltim). 180, 107881 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to mPharma for funding the screening of women in the 10,000 Women Initiative included in this study. The authors are also grateful to the alumni of the Cervical Cancer Prevention and Training Centre (CCPTC) who conducted the screening across Ghana as well as the clinical staff and staff of the IT Department of the CCPTC who helped in screening the women and putting the data together.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conceptualization and design: KE, ET, and NOME. Screening and data collection: ET, AED, GBK, BHA, SK, SD, YTK, and KE. Data management and formal analysis: NOME, SD, STE, YO-B, SK, FA, YTK, ET, and KE. Writing – original draft: NOME, SI, ET, and KE. All the authors read and approved the manuscript in its current form.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

This research is a retrospective analysis of data collected during routine clinical screening. The study protocol for this retrospective analysis, including the plan to publish the findings, was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Catholic Hospital, Battor (approval no. CHB-ERC 002/01/24). The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all women for the collection of their data and samples during their clinical screening. The need for formal written informed consent was waived by the Ethics Review Committee of Catholic Hospital, Battor, due to the retrospective nature of the study. Participant confidentiality and data security were maintained throughout the study by anonymizing all information and storing it on a password-protected computer.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Effah, K., Tekpor, E., Ohene-Bredu, Y. et al. Assessing high-risk human papillomavirus-based cervical precancer screening recommendations and implications among women aged 60/65 years and older in Ghana. Sci Rep 15, 31723 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16409-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16409-3