Abstract

Cu–Cu direct bonding using electroplated ultrafine-grain Cu (107.24 nm) was studied in air at 110–150 °C. Unstable grain boundaries enabled ultrafast grain growth across the bonding interface, analyzed via coincidence site lattice (CSL) boundaries using EBSD. Above 125 °C, the Σ3 boundary length exceeded 40%, while below 120 °C it rapidly declined, transforming into Σ27a, indicating a critical transition dominated by the {115} plane. A temperature–time-dependent grain growth model was developed, incorporating CSL effects. Simulations showed grain evolution and timing of CSL boundary formation, with transition times from 316 to 190 s as temperature increased.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chip-to-chip stacking is the key technology for 2.5D and 3D IC packaging, which bridges system of chips, multiple layer-stacking HBM, and CoWoS (chip on wafer on substrate)1,2,3,4,5,6,7. To decrease the thermal budget, low-temperature Cu–Cu direct bonding has been investigated under special atmospheres (vacuum, N2), passivation layers (Ti, Ag, Au, Pd, Pt), and at a high pressure (over 10 MPa)8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. However, employing these special atmospheres and passivation layers increases production costs. Moreover, high bonding pressure causes the risk of cracking chips, which decreases the yield24,25,26.

In addition to the above reliability issues, Cu–Cu direct bonding has been employed to further enhance the electrical performance by minimizing contact resistance and improving the signal integrity across the dense interconnect interfaces27,28,29,30,31. Compared to traditional solder-based interconnects, Cu–Cu bonding offers superior signal integrity at high frequencies, superior thermal conductivity for heat dissipation, and supports finer pitch connections for advanced miniaturization29,31,33,35. To meet the growing demands of high-performance computing and data center applications, major semiconductor companies have widely adopted Cu–Cu bonding in their advanced packaging solutions, including in CoWoS and EMIB (Embedded Multi-die Interconnect Bridge) technologies28,32,33,34,36,37. This integration minimizes electrical loss and power consumption, which are critical in data center environments striving for higher efficiency and throughput38,39.

Therefore, low-temperature and low-pressure Cu–Cu direct bonding in ambient air is crucial for chip to chip stacking technology24,40,41. Previous studies have shown that nanocrystalline Cu can potentially achieve Cu–Cu direct bonding with low pressure at a low temperature. The current study employed ultrafine-grain Cu (UFG-Cu) for Cu–Cu direct bonding in ambient air at a low pressure (1 MPa). The ultralow surface roughness of the electroplated UFG-Cu films optimized the Cu–Cu direct bonding interfaces, minimized void formation at the bonding interface, and the roughness compensation constant was 0.84. A grain growth model for the interfacial Cu–Cu bonding mechanism was developed by incorporating the effects of the heat transfer field and coincidence site lattice (CSL) grain boundaries. This model enables estimations of the theoretical time required to achieve target CSL grain boundary fractions at the bonding interface, which not only provides valuable insights into the kinetics of grain boundary evolution but also offers practical guidelines for optimizing process parameters for efficient Cu–Cu direct bonding in advanced electronic packaging applications.

Experimental process

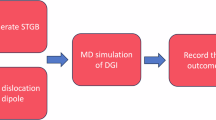

The experimental procedure is illustrated in Fig. 1. A Cu(500 nm)/Ti(200 nm) bilayer was sputtered onto a 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm silicon substrate. The Ti layer served as the adhesion layer between the Cu layer and the Si substrate, and the Cu(500 nm) layer served as the seed layer for subsequent UFG-Cu plating. The following pretreatment process was used to establish the Cu(500 nm)/Ti(200 nm) seed layer prior to the Cu plating process: first, the Cu/Ti-coated Si substrate was dipped in a microetching solution containing 0.36 M sulfuric acid and 6.25 M sodium persulfate for 30 s. The Cu/Ti-coated Si substrate was then immersed in sulfuric acid solution (0.09 M) for 1 min. These two etching processes ensured that any potential Cu surface oxides were removed. After the surface pretreatment, a 5-µm UFG-Cu layer was electroplated on the Cu/Ti/Si substrate using the following electroplating parameters: plating current density and plating time of 2 ASD and 12 min, respectively. Three additives were added to the plating solution. The carrier was composed of 1.5 M Cu sulfate, 0.18 M sulfuric acid, and 60-ppm chloride ions. Bis(3-sulfopropyl) disulfide (SPS) was used as accelerator (6–11 ppm). Polypropylene glycol (PPG) was used as the suppressor (800–1000 ppm) and the leveler was 3-methyl-2-cyclopenten-1-one-4-ol (7–9 ppm).

The prepared 1.5 cm × 1.5 cm silicon substrates coated with Cu(500 nm)/Ti(200 nm) bilayer were diced into smaller bonding samples (0.5 × 0.5 cm) for the subsequent Cu-Cu direct bonding. Cu-Cu direct bonding was conducted at temperatures of 110 °C, 115 °C, 120 °C, 125 °C, 130 °C, 135 °C, 140 °C, 145 °C, and 150 °C in 30 min. All of these temperatures are considerably lower than those used reporting during typical Cu–Cu bonding. A custom-designed graphite bonding tool (shown in Fig. 1) was used to perform Cu–Cu direct bonding at a bonding pressure of 1 MPa in ambient air. The Cu-Cu bonded samples were sectioned using a diamond saw, and the sectioned bonded samples were subsequently ground using sandpaper with various grits (#120, #800, #1200, #2500, and #4000). The ground surface was finished using polishing clothes with a 0.3-µm alumina suspension. Finally, ion milling was employed to clean and deep-etch the bonding interface and reveal the Cu granular microstructure. Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) was used to investigate the orientation of the Cu grains across the bonding interface.

Results and discussion

Analysis of Cu–Cu direct bonding and grain growth across the bonding interface

Figure 2(a) shows an IPF-Z mapping image of the Cu(500 nm)/Ti(200 nm) seed layer. The granular Cu microstructure is clearly evident, and the Cu grains have a (111)-preferred orientation. By treating the Cu grains as equivalent circles, the grain size of the Cu seed layer was estimated, and the size distribution is shown in Fig. 2(b). The average grain size of the Cu seed layer was calculated as approximately 180.73 nm. The UFG-Cu layer was electroplated on the (111)-preferred Cu seed layer. A IPF-Z mapping image on the UFG-Cu is shown in Fig. 3(a), which shows the completely random orientation of the Cu grains in the UFG-Cu layer. This finding indicates that the Cu grain orientation in the present electroplating UFG-Cu layer was not influenced by the (111)-preferred Cu seed layer. The grain size distribution of the UFG-Cu layer is shown in Fig. 3(b), and the average grain size was 107.24 nm.

Cu surface roughness is critical for Cu–Cu direct bonding, as it defines the size and amount of possible voids forming at the initial Cu–Cu bonding interface: a rougher Cu surface results in a larger voiding volume at the initial Cu–Cu bonding interface. The roughness compensation constant, a (\(\:\forall\:\)a > 0), represents the roughness variation per unit length (µm) of the electroplated Cu film. The surface roughness of the electroplated Cu film with a thickness of n can be expressed with the surface roughness compensation constant and the initial surface roughness (\(\:{R}_{a,0}\)) through Eqs. (1),

The expression in Eq. (1) implies the following: (1) if a < 1, the surface roughness of the electroplated film decreases with thickness; (2) if a > 1, the surface roughness increases with thickness. AFM was used to measure the surface roughness of the UFG-Cu layers with different thicknesses (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 μm), and the results were 1.59, 1.34, 1.13, 0.93, 0.79, and 0.67 nm, respectively. AFM images are shown in Fig. 4. With these measurements and using Eq. (1), the surface roughness compensation constant was obtained by the slope of the log-log plot of log(\(\:{R}_{a,n}/{R}_{a,n-1}\)) versus (log(a)). The roughness compensation constant (a) of the present UFG-Cu layers was determined to be 0.84.

Voids typically form at the initial Cu–Cu bonding interface, and the “spherical caps” concept proposed can be used to simulate voids forming at the bonding interface. Surface roughness was thus simulated using downward dishes on the surface roughness profile, which were treated as spherical caps, where the depth of the downward dishes corresponded to the height of the spherical caps (h). The spherical cap of the upper Cu bonding layer and the spherical cap of the bottom Cu bonding layer form the voids at the bonding interface. Thus, the average volume of the spherical caps can be expressed by the Eqs. (2),

where R is the radius of the voids formed by two opposing spherical caps, which can be defined by the average curvature of the spherical caps. Furthermore, the radius (R) of the spherical caps was simulated using the radius of the Cu grain (Rgrain). In this case, the surface roughness (Ra) was treated as the height of the spherical cap (h), and the volume of the spherical caps was expressed using Eqs. (3),

The compression pressure was 1 MPa (i.e., 106 Pa); surface roughness of the Cu layer was 0.67 × 10−9 m, the average grain size was 107.24 × 10−9 m, and the total bonding surface area was 2.25 × 10−4 m2. The outer surface area of the surface Cu grains was calculated as 3.61 × 10−15 m2 using the term of 4π\(\:{{\text{R}}_{grain}}^{2}\). The total number of Cu grains (N) was obtained by dividing the total bonding area by the single Cu grain surface area, and the result was 6.92 × 109. Initial surface roughness was 0.67 × 10−9 m. All these necessary parameters were entered into Eq. (3). The average single void volume was calculated as 7.53 × 10−26 m3. If we assume that the total number of voids corresponds to the total number of the surface Cu grains (i.e., 6.92 × 109), the total void volume would be the multiple of 7.53 × 10−26 m3 with the total number of Cu grains (N), which was calculated as 5.21 × 10−17 m3.

By Young–Laplace Eqs42,43,44,45,46.,

where γ is the Cu surface energy (1.8 J/m2). ΔP is the compression pressure (106 Pa) and rcur is the curvature radius, 3.6 × 10−6 m. Roughness after the bonding compressive pressure (h = 3.99 × 10−10 m) can be calculated using the geometric relationship Eq. (5) for a spherical cap,

where the total void volume after compressive pressure was then calculated as 1.85 × 10−17 m3. The total void volume reduction after the Cu–Cu bonding compression is the difference between the initial void volume and the void volume after bonding compression, which was calculated as 3.36 × 10−17 m3. The applied compression pressure greatly reduces the void volume by approximately 64.5%.

IPF-X images (obtained from EBSD analysis) of Cu–Cu direct bonding samples at different temperatures (110℃, 115℃, 120℃, 125℃, 130℃, 135℃, 140℃, 145℃, and 150℃) are shown in Fig. 5, and the distributions of the grain size (equivalent as circles) of the Cu–Cu direct bonding samples at the different bonding temperatures are shown in Fig. 6. Abnormal grain growth refers to the selective rapid grain growth by grains with specific crystallographic orientations, which results in a bimodal grain size distribution with annealing time. The rapid-growth grains with specific crystallographic orientations typically exhibit lower boundary energy and higher mobility, which enables a faster boundary migration. A bimodal distribution was observed in all the Cu–Cu bonding samples, which indicated that abnormal grain growth behavior occurred in the present Cu–Cu direct bonding under low temperature and low pressure.

To study the grain-growth orientation, we used the inverse pole figure to analyze the preferred orientation of the grain growth, and IPF-X and IPF-Y images of the Cu–Cu direct bonding samples at the different bonding temperatures are shown in Fig. 7. The X-direction is the direction vertical with the Si substrate, and the Y-direction is the parallel direction of the Si substrate. The preferred grain-growth orientations at different bonding temperatures in the X-direction and Y-direction are shown in Tables 1, 2.

As shown in Table 2, we found that the preferred grain-growth orientation varied with the bonding temperature. For the X- direction, the preferred grain-growth orientation occurred in the {111} and {001} plane families in the high bonding temperature range (135℃–150℃). At a bonding temperature below 135℃, the planes with a higher Miller index started to show as the preferred grain-growth orientation. For example, the {115} plane family was the preferred grain-growth orientation at 130℃, 120℃, and 115℃, whereas at 125℃, the {323} plane family was the preferred grain-growth orientation in addition to the {115} plane family. At the lowest bonding temperature of 110℃, high Miller index planes such as {203}, {313}, and {556} dominated the preferred grain-growth orientation. For the Y-direction, the {101} plane family was the only dominant preferred grain-growth orientation in the high bonding temperature range (140℃−150℃). Typically, the preferred grain-growth orientations are determined by the two key factors, i.e., thermodynamics and kinetics. In this work, a relatively high Miller index planes of {323} plane family appears as the preferred grain-growth orientation at 125℃ in the high-temperature Cu-Cu bonding group (> 115℃), which have low Miller index planes as the preferred grain-growth orientation in this work. We believe that, at this temperature of 125℃, either thermodynamics or kinetics could be dominant and favoring the particular {323} plane family as the preferred grain-growth orientation. At a bonding temperature below 135℃, the numbers of the preferred grain-growth orientation plane family with a higher Miller index increased (for instance, {112}, {115},{203}, {212}, and {313}). An interesting finding was that for the X-direction and Y-direction, the preferred grain-growth orientation plane family at 125℃ had the highest Miller index number. From the above IPF-X and IPF-Y results, we found that the Miller index number of the preferred grain-growth orientation plane family increased inversely with the bonding temperature. This finding implies that as the bonding temperature increases, the stability of the grain boundaries with the Miller index number generally increases.

To further investigate the relationship between the grain-growth behavior and the grain boundaries at the bonding interface, we plotted the CSL grain boundaries on the band contrast. The images of the CSL grain boundaries at the bonding interface at different temperatures are shown in Fig. 8. We found that most of the CSL grain boundaries at the bonding interface were Σ3, Σ9, Σ19a, Σ19b, and Σ27a. The planes, spin axes, and spin angles of the different CSL grain boundaries are shown in Table 1. The Σ9, Σ19a, Σ19b, and Σ27a grain boundaries are associated with twin twist grain boundaries47,48,49,50,51,52, and this indicates that the grain boundaries in the UFG-Cu layer are unstable across the Cu–Cu bonding interface, which greatly drives ultra-fast grain growth at the interface of the Cu–Cu direct bonding.

Furthermore, the length percentage of the CSL grain boundary at the Cu–Cu direct bonding interfaces at the different bonding temperatures is shown in Table 3. We found that the Σ3 grain boundary exceeded 40% at temperatures over 125℃. Remarkably, the important temperature was 120℃, at which the Σ3{111} grain boundary was transformed to Σ27a{511}. At a bonding temperature below 120℃, the length percentage of the Σ3 grain boundary dramatically decreased and that of the Σ27a grain boundary increased. This indicates that the {115} plane family dominates the grain growth behavior at the bonding interface below 120℃.

To further validate the mechanical integrity of UFG-Cu direct bonding under low temperature and low pressure, the shear strength of copper to copper direct bonding samples was measured and is shown in Fig. 9. The results demonstrate that all datum of bonding strength exceeds 20 MPa, confirming the feasibility of UFG-Cu bonding for reliable integration under low thermal budgets. These results reinforce the effectiveness of UFG-Cu in promoting strong metallurgical bonding through rapid grain boundary migration and elimination of interfacial voids.

Grain growth model incorporating CSL and heat transfer field

As previously mentioned, grain growth is the key process involved in Cu-Cu direct bonding. Grain growth generally follows the classical kinetic equation,

where D(t) is the average grain size with time, D(0) is the initial grain size, and K is the growth rate constant. In the actual Cu–Cu bonding process, the K of grain growth at the bonding interface is influenced by the temperature field and the presence of CSL boundaries. Therefore, the classical grain growth kinetics Eq. (6) can be modified and incorporated with the effects of the temperature-field driven growth and the CSL boundaries. First, the effect of the temperature field on the grain growth rate is derived as described below.

The heat transfer process can be controlled by Fourier’s law of the heat conduction and the heat diffusion equation, which is shown as Eqs. (7),

where T(x, y, t) is the temperature distribution, α is thermal diffusivity (m2/s), k is thermal conductivity (W/m·K), ρ is density (kg/m³), Cp is the specific heat capacity (J/kg·K), and \(\:{\nabla\:}^{2}\varvec{T}\) is the Laplacian operator. In a two-dimensional system, the Laplacian operator is shown in Eqs. (8),

The time derivative can be approximated by using the forward difference method, as shown in Eqs. (9),

Furthermore, the second-order spatial derivatives can be approximated using the central difference method, as expressed by Eqs. (10) and (11),

The discretized time Eq. (9) and the spatial derivatives (Eqs. (10) and (11)) can be substituted into the heat diffusion equation Eq. (7), and the solution for the heat diffusion equation provides the temperature for the next time (n + 1) second, as shown in Eqs. (12),

The numerical formula used in the MATLAB code to update the temperature field is expressed as Eq. (12). Based on the above calculation, we used the temperature in the n second to derive the temperature in the (n + 1) second. Thus, the time-dependent temperature formula can be expressed as Eqs. (13),

where knormalized = kCu[1/(dx2) + 1/(dy2)].

For the above explicit method (explicit FDM) and MATLAB calculated solutions, the stability condition and boundary conditions must be met. The stability condition is described in Eqs. (14),

and the fixed temperature boundary conditions are applied in the left and right Si substrates. The initial temperature of the Cu–Cu interface was set as 25℃, which means T(0.5n_x, j, 0) = 25℃. The target bonding temperature is expressed as T(1, j, 0) = T(n_x, j, 0). Another two boundary conditions of the grain growth equations are (1) the total void volume after compressive pressure and (2) the length percentages of the CSL grain boundaries with different bonding temperatures (110℃, 115℃, 120℃, 125℃, 130℃, 135℃, 140℃, 145℃, and 150℃).

Hence, the growth rate constant (K) follows the Arrhenius equation and is modified with the influence of the length percentages of the CSL grain boundaries and the temperature time-dependent field, as described by Eqs. (15),

where K0 is the pre-exponential factor, Q is the activation energy for grain boundary migration (activation energy in Cu bulk = 120 kJ/mol), R = 8.314 J/(mol·K) is the gas constant, T(x, y, t) is local temperature at time t, and fCSL(x, y) is the CSL boundary influence factor.

The residual void (Vresidual) represents the voids remaining at the bonding interface. The critical void (Vcritical) represents a cease in the grain growth when the void is at a critical size. For typical thermocompression bonding, residual voids and critical voids affect grain growth (K), which is expressed as Eq. (16). This equation substitutes the vacancy diffusion model to the ΔGeff yields of the effective Arrhenius law53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,

With the previous model developed using the thermal compression process, Vcritical is calculated as 9.63 × 10−17 m3, and Vresidual as 1.85 × 10−17 m3. Hence, using Eq. (16), K0 for the grain growth of the intrinsic Cu can be calculated as 4.45 × 10−4 m2/s and that for Cu grain growth across the bonding interface as 3.67 × 10−4 m2/s.

The effect of the CSL boundaries on grain growth can be defined by the retardation factor shown below,

where WCSL is the length percentage corresponding to different CSL types. This means that the more stable the CSL boundary, the greater the influence on the grain boundary migration, which reduces the local grain growth rate. Combining the above-defined effects from the length percentages of the CSL grain boundaries and the temperature time-dependent field, the overall grain growth equation is

As T(x, y,t) increases, K becomes larger, which accelerates the grain growth rate. WCSL reduces the grain boundary migration rate and slows the grain growth in that region.

The initial length percentages of the CSL grain boundaries (Σ3, Σ9, Σ19a, Σ19b, and Σ27a) at the bonding interface were 4%, and the final length percentages of the CSL grain boundaries are listed in Table 3. We used MATLAB to monitor the length percentages of the CSL grain boundaries in the bonding interface. The monitoring range extended to 200 nm on each side of the bonding interface, for a total of 400 nm. As the length percentage of the CSL grain boundaries met the experimental data, the direct bonding time and the video of the grain growth were recorded.

Video footage showing the output grain evolution can be found at the following link: [https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1KAkzADSVsb8kS7mnQ4ngS8Jezk4Io8IV?usp=drive_link]. The videos show grain growth with bonding temperatures of 110℃, 115℃, 120℃, 125℃, 130℃, 135℃, 140℃, 145℃, and 150℃. The samples at different bonding temperatures achieved the length percentage of the CSL grain boundary in the interface at different times of 316, 283, 255, 220, 213, 206, 198, 194, and 190 s, respectively.

Conclusions

In this study, ultrafast surface grain growth was investigated using CSL (coincidence site lattice) grain boundary analysis with EBSD and the heat transfer field across the bonding interface was analyzed. Random orientation UFG-Cu was electroplated on the (111)-preferred Cu seed layer, and the average grain size of the UFG-Cu layer was 107.24 nm. The roughness compensation constant (a) of the UFG-Cu on the (111)-preferred Cu seed layer was determined as 0.84. Under 1 MPa compression, the void volume was reduced by approximately 64.5%. In this studies, the ultra-fast surface grain growth was investigated by the CSL (coincidence site lattice) grain boundary analysis with EBSD and heat transfer field across the bonding interface.

From the above IPF-X and IPF-Y results, we found that the Miller index number increased inversely with the bonding temperature. This finding implies that as the bonding temperature increases, the stability of the grain boundaries generally increases with the Miller index number. The grain growth behavior across the bonding interface is governed by the stability of the grain boundaries, which has the dependence on the bond.

The length percentage of the Σ3 grain boundary exceeded 40% at a bonding temperature above 125℃. At a bonding temperature below 120℃, the length percentage of the Σ3 grain boundary dramatically decreased and transformed to Σ27a grain boundary. This indicates that the {115} plane family dominates grain growth behavior at the bonding interface below 120℃. Therefore, 120℃ is a critical temperature for converting the dominant grain boundary from Σ3{111} to Σ27a{511}.

Combining the effects from the length percentages of the CSL grain boundaries and the temperature time-dependent field, the overall grain growth equation was modeled. Using this developed model, the grain evolution with the output temperature field was recorded on video, which showed grain growth with bonding temperatures (110℃, 115℃, 120℃, 125℃, 130℃, 135℃, 140℃, 145℃, and 150℃). From the video, the different times taken to achieve the length percentage of the CSL grain boundary were defined at the interface, and these were 316 s, 283 s, 255 s, 220 s, 213 s, 206 s, 198 s, 194 s, and 190 s for 110 °C, 115 °C, 120 °C, 125 °C, 130 °C, 135 °C, 140 °C, 145 °C, and 150 °C, respectively.

Data availability

All experimental data supporting the findings of this study are included within the manuscript and its supplementary information files.

References

Lee, I. et al. Extremely large 3.5D heterogeneous integration for the next-generation packaging technology. 2023 IEEE 73rd Electron Compon. Technol. Conf 893–898 (2023).

Lau, J. H. Recent advances and trends in advanced packaging. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag Manuf. Technol. 12, 228–252 (2022).

Agrawal, A. et al. Thermal and electrical performance of direct bond interconnect technology for 2.5D and 3D integrated circuits. IEEE 67th Electron. Compon. Technol. Conf. 989–998 (2017). 989–998 (2017). (2017).

Chou, T. C. et al. Investigation of pillar–concave structure for low-temperature Cu–Cu direct bonding in 3-D/2.5-D heterogeneous integration. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag Manuf. Technol. 10, 1296–1303 (2020).

Min, M. & Kadivar, S. Accelerating innovations in the new era of HPC, 5G and networking with advanced 3D packaging technologies. 2020 Int. Wafer Level Packag Conf 1–6 (2020).

Li, M. J. et al. Cu–Cu bonding using selective Cobalt atomic layer deposition for 2.5-D/3-D chip integration technologies. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag Manuf. Technol. 10, 2125–2128 (2020).

Agarwal, R. et al. C. 3D packaging for heterogeneous integration. 2022 IEEE 72nd Electron. Compon. Technol. Conf 1103–1107 (2022).

Zhang, M., Gao, L. Y., Li, J. J., Sun, R. & Liu, Z. Q. Characterization of Cu–Cu direct bonding in ambient atmosphere enabled using (111)-oriented nanotwinned-copper. Mater. Chem. Phys. 306, 128089 (2023).

Panigrahy, A. K. & Chen, K. N. Low temperature Cu–Cu bonding technology in three-dimensional integration: an extensive review. J. Electron. Packag. 140, 010801 (2018).

Gondcharton, P., Imbert, B., Benaissa, L., Carron, V. & Verdier, M. Kinetics of low temperature direct copper–copper bonding. Microsyst. Technol. 21, 995–1001 (2015).

Juang, J. Y. et al. Low-resistance and high-strength copper direct bonding in no-vacuum ambient using highly (111)-oriented nano-twinned copper. 2019 IEEE 69th Electron. Compon. Technol. Conf 642–647 (2019).

Park, H. & Kim, S. E. Two-step plasma treatment on copper surface for low-temperature Cu thermo-compression bonding. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag Manuf. Technol. 10, 332–338 (2020).

Juang, J. Y. et al. Copper-to-copper direct bonding on highly (111)-oriented nanotwinned copper in no-vacuum ambient. Sci. Rep. 8, 13910 (2018).

Lin, P. F., Tran, D. P., Liu, H. C., Li, Y. Y. & Chen, C. Interfacial characterization of low-temperature Cu-to-Cu direct bonding with chemical mechanical planarized nanotwinned Cu films. Materials 15, 937 (2022).

Cho, J. et al. Mechanism of low-temperature copper-to-copper direct bonding for 3D TSV package interconnection. IEEE 63rd Electron. Compon. Technol. Conf. 1133–1140 (2013). 1133–1140 (2013). (2013).

Liu, D. et al. Investigation of low-temperature Cu–Cu direct bonding with Pt passivation layer in 3-D integration. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag Manuf. Technol. 11, 573–578 (2021).

Hong, Z. J. et al. Investigation of bonding mechanism for low-temperature Cu–Cu bonding with passivation layer. Appl. Surf. Sci. 592, 153243 (2022).

Huang, Y. P., Chien, Y. S., Tzeng, R. N. & Chen, K. N. Demonstration and electrical performance of Cu–Cu bonding at 150°C with Pd passivation. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices. 62, 2587–2592 (2015).

Jeong, M. S. et al. Unraveling diffusion behavior in Cu-to-Cu direct bonding with metal passivation layers. Sci. Rep. 14, 6665 (2024).

Suga, T., He, R. & Vakanas, G. & La Manna, A. Direct Cu to Cu bonding and alternative bonding techniques in 3D packaging. in 3D Microelectron. Packag. 201–231Springer Singapore, (2021).

Panigrahy, A. K., Bonam, S., Ghosh, T., Singh, S. G. & Vanjari, S. R. K. Ultra-thin Ti passivation mediated breakthrough in high-quality Cu–Cu bonding at low temperature and pressure. Mater. Lett. 169, 269–272 (2016).

Bonam, S., Panigrahy, A. K., Kumar, C. H., Vanjari, S. R. K. & Singh, S. G. Interface and reliability analysis of Au-passivated Cu–Cu fine-pitch thermocompression bonding for 3-D IC applications. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag Manuf. Technol. 9, 1227–1234 (2019).

Chou, T. C. et al. Electrical and reliability investigation of Cu-to-Cu bonding with silver passivation layer in 3-D integration. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag Manuf. Technol. 11, 36–42 (2021).

Lee, Y. F. et al. Low temperature Cu–Cu direct bonding in air ambient by ultrafast surface grain growth. R Soc. Open. Sci. 11, 240459 (2024).

Fukushima, T. et al. Oxide-oxide thermocompression direct bonding technologies with capillary self-assembly for multichip-to-wafer heterogeneous 3D system integration. Micromachines 7, 184 (2016).

Shie, K. C., Hsu, P. N., Li, Y. J., Tran, D. P. & Chen, C. Failure mechanisms of Cu–Cu bumps under thermal cycling. Materials 14, 5522 (2021).

Huang, Y. C., Lin, Y. X., Hsiung, C. K., Hung, T. H. & Chen, K. N. Cu-based thermo-compression bonding and cu/dielectric hybrid bonding for three-dimensional integrated circuits (3D ICs) application. Nanomaterials 13, 2490 (2023).

Hsu, M. P. et al. K.-N. Development of low-temperature bonding platform using ultra-thin area selective deposition for heterogeneous integration. Appl. Surf. Sci. 635, 157645 (2023).

Li, B. et al. High Cu-Cu bonding strength achievement using micron copper particles under formic acid atmosphere. Processes 13, 1042 (2025).

Wu, Y., Zhang, X., Li, Y. & Chen, K. Process parameters and modeling study of thermosonic flip chip bonding. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag Manuf. Technol. 13, 545–552 (2023).

Moon, J. H., Kim, S. Y. & Lee, J. H. Materials quest for advanced interconnect metallization in integrated circuits. Adv. Sci. 10, 2207321 (2023).

Xu, Y., Wang, L. & Zhao, H. Structural analysis of anisotropic conductive film for liquid crystal displays and semiconductor packaging applications. in Proc. 24th Int. Conf. Electron. Packag. Technol. (ICEPT) 1–5 (2023).

Cheemalamarri, H. K., Patel, R. & Lee, C. Cu/dielectric hybrid bonding among glass and Si. in Proc. 74th Electron. Compon. Technol. Conf. (ECTC) 1234–1239IEEE, (2024).

Sudarshan, C. C., Kumar, A., Singh, R. & ECO-CHIP Estimation of carbon footprint of chiplet-based architectures for sustainable VLSI. in Proc. IEEE Int. Symp. High-Perform. Comput. Archit. (HPCA) 456–467 (2024).

He, T., Zhang, Y. & Liu, M. A modified Qian-Liu constitutive model based on advanced packaging underfill materials. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 176, 108340 (2024).

Qiao, P., Li, X. & Zhang, Y. Research on the related properties of ACF anisotropic conductive adhesive. Highl Sci. Eng. Technol. 56, 308–314 (2023).

Wang, Y., Zhou, Z. & Lin, H. Challenges and recent prospectives of 3D heterogeneous integration. J. Electron. Packag. 144, 031002 (2022).

Huang, H. D., Chen, L. & Wang, J. Promising strategies and new opportunities for high barrier polymer packaging films. Prog Polym. Sci. 132, 101722 (2023).

Alzyod, H. & Ficzere, P. Thermal evaluation of material extrusion process parameters and their impact on warping deformation. Jordan J. Mech. Ind. Eng. 17, 123–130 (2023).

Shigetou, A., Itoh, T., Matsuo, M., Hayasaka, N. & Okumura, K. Bumpless interconnect through ultrafine Cu electrodes by means of surface-activated bonding (SAB) method. IEEE Trans. Adv. Packag. 29, 577–583 (2006).

He, R., Fujino, M., Yamauchi, A., Wang, Y. & Suga, T. Combined surface activated bonding technique for low-temperature cu/dielectric hybrid bonding. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 5, P1–P6 (2016).

Chang, Y. W., Lu, Y. S. & Tu, K. N. Interfacial characterization of low-temperature Cu-to-Cu direct bonding using nanotwinned films. Micromachines 13, 222 (2022).

Lai, Y. H., Hsu, W. H., Hsieh, C. H. & Wu, W. W. Characterization of Cu–Cu direct bonding in ambient atmosphere. Mater. Chem. Phys. 303, 127728 (2023).

Wang, Z., Chen, K. N. & Tu, K. N. Low-temperature direct copper-to-copper bonding enabled by creep. Micromachines 6, 1215–1231 (2015).

Wang, Q., Ma, D., Wu, W., Zhang, Y. & Guo, Y. Impact of crystalline orientation on Cu–Cu solid-state bonding behavior by molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 13, 16980 (2023).

Lee, T. Y. & Chen, K. N. Copper–copper direct bonding: Impact of grain size. in Proc. IEEE 66th Electron. Compon. Technol. Conf. (ECTC) 2169–2173IEEE, (2016).

Głowinski, K., Głowinska, E., Kaczmarek, Ł. & Pawlicki, J. Grain boundary engineering using self-organized high-index twins. Mater. Charact. 205, 112787 (2024).

Głowinski, K. Microstructure, crystallography and CSL grain boundaries in copper. SKB Tech. Rep (2023). TR-23-01, Svensk Kärnbränslehantering AB. ISSN 1404-0344

Rohrer, G. S., Hu, X., Szpunar, J. A., Saylor, D. M. & Wynblatt, P. Orientation distribution of Σ3 grain boundary planes in Ni before and after grain boundary engineering. Acta Mater. 55, 4111–4122 (2007).

Głowinski, K., Głowinska, E., Krawczyk, J. & Pawlicki, J. Methods for quantitative characterization of three-dimensional grain boundary networks. Mater. Charact. 201, 111684 (2023).

Lin, B., Schuh, C. A. & Dillon, S. J. Investigating annealing twin formation mechanisms in face-centered cubic metals. Acta Mater. 83, 176–186 (2015).

Li, X., Zhang, Y., Wang, Y., Chen, X. & Han, X. Twin-related grain boundary engineering and its influence on mechanical properties of face-centered cubic metals: A review. Metals 13, 234 (2023).

Herring, C. Diffusional viscosity of a polycrystalline solid. Acta Metall. 30, 339–344 (1982).

Miller, M. K., Russell, K. F. & Miller, M. K. Void growth due to vacancy supersaturation – a non-equilibrium thermodynamics study. Acta Mater. 55, 2059–2069 (2007).

Huang, P., Yip, S. & Orkoulas, G. Finite-element simulation of the diffusive growth of grain boundary voids. Model. Simul. Mater Sci. Eng. 8, 285–295 (2000).

Magri, M., Lemoine, G., Adam, L. & Segurado, J. A coupled model of diffusional creep of polycrystalline solids based on climb of dislocations at grain boundaries. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 135, 103786 (2020).

Po, G. et al. Ghoniem, N. A model of thermal creep and annealing in finite domains based on coupled dislocation climb and vacancy diffusion. J. Mech. Phys. Solids. 169, 105066 (2022).

Dholabhai, P. P., Anwar, S., Adams, J. B., Crozier, P. & Sharma, R. Kinetic lattice Monte Carlo model for oxygen vacancy diffusion in Praseodymium doped ceria: applications to materials design. J. Solid State Chem. 184, 811–817 (2011).

Kirchheim, R. Reducing grain boundary, dislocation line and vacancy formation energies by solute segregation. I. Theoretical background. Acta Mater. 55, 5129–5138 (2007).

Ko, K. J., Cha, P. R., Srolovitz, D. & Hwang, N. M. Abnormal grain growth induced by sub-boundary-enhanced solid-state wetting: analysis by phase-field model simulations. Acta Mater. 57, 838–845 (2009).

Zhou, X., Mousseau, N. & Song, J. Is hydrogen diffusion along grain boundaries fast or slow? Atomistic origin and mechanistic modeling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 215501 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was mainly supported by Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of Taiwan under the projects of MOST 111-2221-E-008-084-MY3. Especially, Authors like to thank Mr. Yang and Pf. L.W. Chang for their assistance of EBSD of the department of materials and optoelectronic science in National Sun Yat-sen University.

Funding

This work was mainly supported by Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST) of Taiwan under the projects of MOST 111-2221-E-008-084-MY3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yun Fong Lee is the first author, leads the full research, and writes the full paper.Cheng-Yi Liu and Chia-Hua Lin are the supervisors of this paper.Chih-Wen Chiu, Chin-Yen Chiu, and Yu-Chen Huang help Yun Fong Lee to discuss the equations and derivations.Mei-Hsin Lo, Liu-Hsin-Chen Yang, Ting-Yi Cheng, and Zhong-Yen Yu help to data collection of the EBSD images.Chih-En Hsu, Kai-Chi Lin, Po-Yu Chen, Wei-Cheih Huang, Jui-Sheng Chang, Shao-An Pan, Yi-Cheng Su, Chin-Li Lin, and Hang-Chen Hsieh help to do the paper survey and experiment assistances.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, YF., Chiu, CW., Chiu, CY. et al. Grain boundary motions of low temperature and low pressure copper to copper direct bonding by electroplating ultra-fine-grain (UFG) Cu. Sci Rep 15, 30978 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17058-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17058-2