Abstract

A fault location method based on line commutation converter (LCC) signal injection strategy for hybrid multi-terminal direct current (MTDC) system is proposed to deter-mine the fault location after the permanent fault occurs and facilitate the line inspection and maintenance by the staff. Firstly, using the fault control ability of LCC, the additional control strategy is applied to the trigger angle of LCC to realize signal injection. The frequency, duration and amplitude of the injection signal are analyzed and determined, and a signal injection strategy based on LCC is proposed. Secondly, In the injection signal mode, the fault location equations for pole to ground fault and pole to pole fault in the distributed parameter model are derived respectively. The hyperbolic function in the fault location equation is replaced by Taylor series, and the multi order fault location equation is written. Using Ferrari method to solve the analytical solution of fault location equation to realize fault location. PSCAD/EMTDC simulation results show that the proposed fault location method only uses single terminal data, the location error is less than 1%, has high location accuracy. It can withstand 400 Ω fault resistance and 40 dB noise interference, and does not have the problem of iterative convergence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The traditional high voltage direct current (HVDC) system uses line commutation converter (LCC), which can enable high-performance power transmission with three defining characteristics: long-distance transmission capability, large-capacity power transfer and seamless cross-regional grid interconnection. However, as the receiving end, it is prone to commutation failure1. With the emergence of turn off devices, voltage source converter (VSC) with high controllability has developed rapidly. Compared with LCC, VSC does not need to consider commutation failure2. Among many VSC topologies, modular multilevel converter (MMC) has become the preferred technical scheme for flexible DC transmission projects due to its highly modular design, easy expansion, and less harmonic voltage. However, MMC has high cost and large loss3. Therefore, the hybrid MTDC system, which synergistically combines the complementary advantages of both technologies, demonstrates significant potential for wide-spread adoption and future development4,5,6,7.

Long-distance and large-capacity DC transmission projects generally use overhead lines for power transmission, with high failure probability. After a permanent fault occurs, it is necessary to determine the fault location for the convenience of staff maintenance. The existing fault location methods based on signal injection strategy can be divided into traveling wave method, fault analysis method, AI method and impedance method.

The traveling wave fault location method mainly depends on the principle of traveling wave refraction and reflection and the extraction of traveling wave head. References8,9,10,11 inject traveling wave signals into the line, and realize fault location according to the time difference between the incident wave and reflected wave of traveling wave reaching the measuring end. Reference12 used the solid-state circuit breaker to inject signals with different pulse widths. Detection of first and last arrival time of pulse using improved adaptive modulus maxima method. The fault location is realized according to the propagation time interval of the injected signal. However, the above fault location methods need to accurately capture the arrival time of traveling wave head. Reference13 injects current signal into the line. The fault location is achieved through an iterative computational algorithm that leverages the precise mathematical relationship be-tween traveling wave frequencies (primary/secondary) and fault distance. The effectiveness of this method varies with the sampling rate.

The fault analysis method constructs the fault location equation according to the system model and the relationship between electrical quantities to realize the fault lo-cation. References14,15 injects characteristic signals into the line, and then constructs the ranging equation according to the distribution characteristics of electrical quantities along the line to realize fault location. However, the above method needs iterative calculation when solving the equation, which has the problems of large amount of calculation and iterative convergence. Reference16 solves the fault distance by unlocking the injection cur-rent of DC/DC converter station and using the relationship between fault resistance and high-frequency impedance. Reference17 injects a small current into the line, constructs the ranging equation by analyzing the electrical quantity characteristics of the fault circuit in the time domain. The fault location is realized by using the least square method. This method is suitable for DC distribution system with controllable current limiting reactor. References18,19 respectively inject harmonic voltage and current into the line, and use the pure resistance property of the grounding impedance at the fault point to carry out fault location. Reference20 used the injection current signal to calculate the ratio of the positive and negative line inductance from the fault point to the VSC outlet. The accurate solution of fault distance is realized. However, this method requires additional hybrid quick disconnectors. Reference21 used hybrid MMC to inject characteristic signals into the line and uses the idea of parameter identification to realize fault location. Only a few of the above methods discussed the fault location method based on LCC signal injection.

For method based on AI, Ref22. considers the physical structure of the power grid as an important constraint factor for training deep graph learning models. Then, a special spatiotemporal convolutional block is utilized to enhance the waveform feature extraction ability. Finally, a multi task learning framework is constructed for fault location. This method requires precise modeling of actual engineering models. Reference23 adopts the adaptive time-frequency signal processing method (EMT) to extract signal features, and uses the Teager energy operator (TEO) to capture the instantaneous amplitude and frequency changes of the signal, thereby obtaining fault features. Afterwards, neural networks are used to train the data and obtain accurate fault distances.

For impedance method, Ref24. injects two signals of different frequencies at the first end of the grounding electrode and measures the amplitude of impedance change Distinguish the distance interval of the fault occurrence based on the value and phase angle information. Afterwards, calculate the fault distance based on the distance measurement expression and boundary phase angle values. This method requires a higher sampling frequency and additional wave blockers. Reference16 unlocks the DC/DC converter station injection signal, constructs the fault distance measurement equation using the fault resistance expression, and solves to obtain the fault distance.

To sum up, on the one hand, fault location method based on active injection of characteristic signals are mostly based on hybrid MMC or full bridge MMC with fault self-clearing capability and DC circuit breakers, which are suitable for flexible DC transmission systems. On the other hand, research on fault location methods for hybrid MTDC systems remains limited, with most existing approaches failing to adequately address several critical challenges. Conventional methods often neglect the influence of distributed capacitive currents in transmission lines, particularly for long-distance applications. Furthermore, these methods are susceptible to multiple interfering fac-tors, including sampling rate variations, DC boundary effects. Many algorithms also rely on iterative numerical solutions for solving fault location equations, introducing convergence issues. These limitations underscore the urgent need for advanced fault location methodologies specifically designed for hybrid MTDC systems.

This paper proposed a fault location method for hybrid MTDC system based on the LCC strategy. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

-

1.

The proposed method uses LCC to inject signal without PI regulation, and has faster response speed.

-

2.

The proposed fault location method utilizing only single end data, eliminating dependence on communication channels and their associated latency or synchronization issues. In addition, this paper used the Ferrari method to solve the analytical solution of the location equation to achieve fault location, there is no iterative convergence problem.

-

3.

The applicability of the proposed method under the influence of fault resistance, noise, sampling rate, and DC boundary was verified in PSCAD/EMTDC.

The main contents of the paper are as follows: In “Signal injection strategy”, the signal injection strategy based on LCC is proposed. In “Injection signal selection”, the selection of injection signal length, frequency and amplitude is discussed. In “Fault location method”, the fault location equation is con-structed in the injected signal mode, and the fault location method is proposed. In “Simulation verification”, the performance of the proposed method has been verified under different fault scenarios. Section “Conclusions” concludes this paper.

Signal injection strategy

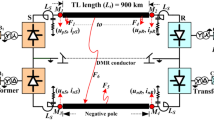

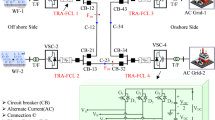

The topology of hybrid MTDC system is shown in Fig. 1. It is composed of sending end LCC and receiving end half bridge MMC in parallel.

In Fig. 1a, b are the protection installations of the positive pole, a’, b’ are the protection installations of the negative pole, Ldc is smoothing reactor.

Under normal operating conditions of the hybrid MTDC system, the LCC station implements constant current control to maintain DC current stability, while the MMC stations employ dual control modes: constant DC voltage control to regulate system voltage, and constant active power control for precise power dispatch. In case of DC line fault, LCC will conduct emergency phase shifting or change the reference value of constant current control to realize fault current limiting25. MMC side will adopt fault current limiting strategy for fault isolation.

At present, there are few researches on using LCC to realize characteristic signal injection, but there are also some papers that have carried out preliminary exploration. References14,15 inject current signal through LCC, Ref26. injects voltage signal through LCC. The control block diagram is shown in Fig. 2.

In Fig. 2, Idcn is the DC current reference value of constant current control DC current during normal operation, Idc is the measured value of DC current, Idcset is the set value of DC current in14]– [15 injection signal stage, Idcset1 is the set value of DC current in14 fault current limiting stage, αref is the reference value of trigger angle, αset is the set value of trigger angle in15,26 fault current limiting stage, αset1 is the set value of trigger angle in26 injection signal stage, α is the trigger angle of final output.

As shown in Fig. 2, LCC adopts constant current control during normal operation. After the fault occurred, Reference14 set the constant current control reference value to 0 to realize fault current limiting. Reference15 achieved fault current limiting by increasing the trigger angle to more than 90° through emergency phase shifting. After that, both inject current signals by changing the reference value of constant current control. Considering the unidirectional conductivity of the thyristor, in the current injection stage, to ensure the constant current direction, the DC component should be added to the DC current reference value of the above injection method. As shown in the following Eq.

where A is the DC component; B is the injection signal amplitude; ω is the angular frequency of the injection signal; φ is the initial phase of the injection signal.

Reference26 realizes fault current limiting by emergency phase shifting, and then realizes voltage signal injection by short-time step changing trigger angle.

When the LCC side adopts the constant current control, the PI control is driven by the deviation between the DC current reference value and the measured value to adjust, to obtain the corresponding trigger angle α. Therefore, this paper realizes characteristic signal injection by changing the trigger angle of LCC. Since the response characteristics of the AC signal system injected into the DC system are more obvious. The AC signal is injected by changing the trigger angle sinusoidally. For the fault current limiting strategy, Ref14. set the current reference value to 0 to achieve fault current limiting, and then get the trigger angle through PI control. The control function is shown in (2).

where P is the proportional coefficient of PI regulator; T is the integral time constant of the PI regulator. References15,26 realizes fault current limiting by directly changing the trigger angle, saves PI control time, and can limit the fault current to 0 faster. The effects of the two different fault current limiting strategies are shown in Fig. 3.

According to Fig. 3, the fault current limiting strategy by changing the trigger angle can limit the current to 0 faster. Consequently, the paper achieves effective fault current limitation through emergency phase-shift control.

To sum up, the LCC injection signal strategy adopted in this paper is shown in Fig. 4.

In Fig. 4, αset1 is the trigger angle setting value in the fault current limiting stage, αset2 is the trigger angle setting value in the injection signal stage.

For LCC converter, pole to ground DC voltage Udc can be expressed as:

where N is the number of 6 pulse converters in each pole, in this paper, 12-pulsae converters are used, taking N = 2, U1 is the effective value of no-load line voltage at the valve side of converter transformer, which is 210 kV in this paper; α is the trigger angle; Xr is commutation reactance; Idc is DC current.

According to (3), the voltage signal can be injected by changing the trigger angle.

When a fault occurs, the LCC side triggers the fault current limiting strategy to limit the fault current to 0. In this paper, the trigger angle α is set to 150 °, as shown in (4).

After the fault occurs, the system enters the system recovery stage after a fixed delay of 150ms (i.e. the deionization time, generally 100ms ~ 300ms)21. Currently, LCC switches from fault current limiting control strategy to signal injection control strategy, that is, signal injection is realized by changing the trigger angle.

Injection signal selection

The injection signal selection needs to be considered from three aspects: injection length, injection frequency and injection amplitude. The following is a detailed analysis.

Length of injection signal

The length of the injection signal needs to consider factors such as signal trans-mission delay, signal sampling period, transformer transmission delay, etc. Specific analysis is as follows:

(1) Signal transmission delay. The wave speed of signal transmission is as follows14.

where rm is the resistance parameter per unit length; lm is the inductance parameter per unit length; cm is the capacitance parameter per unit length; gm is the conductivity parameter per unit length.

According to (5), considering the total length of the line used in this paper is about 1500 km, the signal transmission time in the line is about 7.5ms. The injection signal duration shall be greater than the signal transmission delay.

(2) Signal sampling period. According to Nyquist theorem, to accurately extract the signal, it needs at least twice the length of the characteristic frequency. Considering that the injection signal frequency selected is 20 Hz in this paper, a sampling period is 50ms, and the double length is 100ms.

(3) Transformer transmission delay. The current Chinese national standard GB/T 26,217 − 2019 stipulates that the transmission delay of DC electronic voltage transformer shall not be greater than 500 µs27. And the injection time shall be greater than the transmission delay of transformer.

(4) Filter delay. This paper employs a 50th-order FIR low-pass filter for precise time-domain waveform extraction, with the corresponding filter group delay calculated as (6):

where n is the filter order; fs is the system sampling rate. According to (6), to ensure accurate signal extraction at a sampling rate of 10 kHz, the injection signal length must be greater than 5ms to compensate for filter delay.

(5) The system recovers for a short time. To enhance power supply reliability and minimize outage duration, the system should be recovered in a short time to reduce the power failure time, so the injection signal time should not be too long. During the recovery process of the project, the deionization time is generally set to 100 ~ 300ms, and the number of restarts is set to 0 ~ 5. The system recovery takes several seconds or even longer.

(6) Impact on the system. When the converter operates with an excessive trigger angle (α > 50°), significant operational degradation occurs in critical converter station equipment. The service life will be reduced accordingly, and the interference level of the converter station will also increase28. Therefore, the signal injection time should not be too long.

To sum up, to ensure the effect of the injection signal, the length of the injection signal is set to 150 ms.

Frequency of injection signal

When selecting the injection signal frequency, factors such as signal transmission effect, converter frequency output capability, DC filter resonance and so on should be considered. The following is a detailed analysis.

(1) Signal transmission effect. The attenuation factor in the transmission process of injection signal shall be considered, and the line transmission coefficient is shown in (7).

Considering that the length of the line used in this paper is about 1500 km, the typical transmission attenuation curve under 1500 km overhead line is drawn according to (7), as shown in Fig. 5.

According to Fig. 5, the signal attenuation exhibits a frequency-dependent characteristic which increased injection signal frequency leads to greater attenuation. So, the injection signal frequency should not be too high.

(2) Converter frequency output capability. In this paper, a 12-pulse converter is used, and the effect of signal injection at different frequencies is shown in Fig. 6.

According to Fig. 6, due to the limitations of the converter’s output capacity, the quality of the injected signal gradually worsens as the frequency increases. At the same time, considering that the 12-pulse converter will output 12-times integer harmonics, the injected signal frequency should avoid the harmonic frequency.

(3) DC filter resonance. The injection signal frequency shall avoid the resonant frequency of the DC filter to avoid affecting the operation of the DC filter. The amplitude-frequency characteristic curve of the DC filter of the system shows in Fig. 7. in this paper.

According to Fig. 7, the DC filter has multiple series and parallel resonant frequencies, and the injection frequency should avoid the series and parallel resonant frequencies shown in the Fig. 7.

(4) Sampling rate of protection installation. In the actual project, the sampling rate of the protection installation is generally between 10 and 50 kHz29, and the injection frequency should be much lower than the sampling rate of the protection installation to ensure that the device can effectively obtain the injection signal.

(5) Considering that the distributed parameter model is used for analysis in this paper, the line length is 1500 km, so the amplitude-frequency characteristics of hyperbolic function under 1500 km are analyzed, and the amplitude-frequency characteristics are shown in Fig. 8.

According to Fig. 8, the hyperbolic function changes linearly in the low frequency band. In addition, when using the distributed parameter model to calculate the electrical quantity at the remote end, only 100 Hz and below of the line parameters can be accurately calculated30. Therefore, the injection signal frequency should not be too high.

(6) Considering that this paper needs to calculate the voltage at the remote end from the voltage at local end, it is necessary to consider the distribution error along the voltage, as shown in (8)31.

where ω is the angular frequency of the injection signal; l is the line length; v is the wave velocity. From (8), the error curve when the line length is 1500 km is shown in Fig. 9.

According to (8) and Fig. 9, at a length of 1500 km and a frequency of 30 Hz, the error reaches 10.2%, and the error increases with the increase of frequency. So, the injection frequency should not be too high.

(7) Impact on the system. The higher frequency of sine change trigger angle may cause the equipment to overheat for a short time and affect the stability of the system. Therefore, the frequency should not be too high.

To sum up, the frequency of the injection signal is 20 Hz.

Amplitude of injection signal

The amplitude of the injection signal needs to consider the measurement accuracy of the transformer, the impact on the injection equipment. Specific analysis is as follows:

(1) Measurement accuracy of transformer. It must be ensured that the amplitude of the injection signal is greater than the lower limit of the measured value of the transformer. Taking the electronic transformer as an example, the amplitude of the injection signal should be greater than 0.05p.u32. According to (3), the change range of trigger angle should be less than 87 °, and the smaller the trigger angle, the higher the injection voltage amplitude, which will affect the system operation. So the trigger angle should not be too low. It is recommended to set the change range of trigger angle sine to 83 °~85 °.

(2) Impact on injection equipment. Injection current will be generated in the DC line when the voltage signal is injected, resulting in the injection current component in the bridge arm. Because the smaller the trigger angle is, the higher the injection voltage amplitude is, the higher the injection current component amplitude is when the system resistance is constant. The bridge arm current component is composed of the injection signal component and the original AC current. It shall be ensured that the bridge arm current does not exceed its maximum bearing range to avoid secondary impact on the equipment. The overload capacity of the thyristor for 5s can reach 1.3 times the rated current28. The expression of bridge arm current is shown in (9).

When the system operates normally, the simulation results of rated DC current and rated AC current at LCC side is shown in Fig. 10.

According to Fig. 10, the rated DC current is 1.535 kA and the rated AC current is 2.346 kA during normal operation of the system. According to (9), the rated current of the bridge arm is about 1.685 kA. Because the overload capacity of the thyristor for 5s can reach 1.3 times the rated current, the maximum current that the bridge arm can withstand is about 2.191 kA.

When the sinusoidal change range of trigger angle is 83 °~85 °, the simulation results of DC current and AC current at LCC side in the stage of signal injection under the most serious fault condition (i.e., DC line first end fault) are shown in Fig. 11.

According to Fig. 11, when the DC current is 3.131kA and the AC current is 0.7169kA, the bridge arm current reaches its peak. According to (9), the bridge arm current is about 1.463 kA, within its acceptable range. When the trigger angle continues to decrease, the DC peak current will increase, which may exceed the current bearing range of the bridge arm. Therefore, the trigger angle should not be too low.

To sum up, to ensure the effect of injection signal, the sine change range of trigger angle is 83 °~85 °.

The trigger angle and DC voltage response obtained by using the above injection signal length, frequency and amplitude are shown in Fig. 12.

From the above analysis, the injection method proposed in this paper does not need to be adjusted by PI, and has faster response speed.

Fault location method

Response characteristics analysis of injection signal parameters

For accurate fault analysis in bipolar systems, decoupling of the coupled positive and negative DC lines is essential through modal domain transformation. The decom-posed current and voltage components at the protection location are calculated as follows.

where the 1-mode and 0-mode are represented by subscripts “1” and “0” respectively; the electricity quantites of the positive and negative electrodes is represented by p and n, respectively.

The response characteristics of fault point parameter changes under permanent pole-to-ground (PTG) fault and permanent pole-to-pole (PTP) fault are analyzed as follows33.

(1) Pole-to-ground fault.

In PTG fault, the fault pole LCC triggers the signal injection strategy. Currently, the fault pole emergency phase shift limits the current to 0 and then injects the characteristic signal. The sound pole LCC will not trigger the signal injection strategy and will not inject the characteristic signal. Therefore, the sound pole injection characteristic signal is 0. Taking the positive PTG fault as an example, the system topology is shown in Fig. 13.

In Fig. 13, Uf is the injection voltage at the positive fault point; If is the injection current at the positive fault point. Currently, the injection voltage and current at the positive fault point meet the following relationship:

Using (10) and (11) to decouple the positive and negative voltages and currents at the fault point, the modulus expression can be obtained as (13).

From (13) and (14), it can be concluded that the 0-mode current, voltage and 1-mode voltage at the fault point meet the following relationship:

From the above analysis, the 0-mode voltage at the fault point is equal to the 1-mode voltage, and the 0-mode current is equal to the 1-mode current when the signal is injected. Taking the 0-mode voltage and 0-mode current at the fault point under the permanent PTG fault through 100 Ω fault resistance as an example, the response waveform is shown in Fig. 14.

From Fig. 14 that the 0-mode voltage and current at the fault point change sinusoidally under the permanent single pole grounding fault under 100 Ω fault resistance, and its response characteristics conform to (15).

(2) Pole-to-pole fault.

Both positive and negative LCCs trigger the signal injection strategy in case of PTP fault. Both positive and negative LCCs inject characteristic signals after emergency phase shifting limits the fault current to 0. The system topology is shown in Fig. 15.

Currently, the positive voltage, current and negative voltage, current at the fault point meet the following relationship.

where Upf and Unf are positive fault point voltage and negative fault point voltage respectively; Ipf and Inf are positive fault point current and negative fault point current respectively.

Using (10) and (11) to decouple the positive and negative voltages and currents at the fault point, (17) can be obtained.

From (17), it can be concluded that there is no 0-mode component in case of PTP fault, and the relationship between the 1-mode voltage and current at the fault point meets the following.

The response of the 1-mode voltage and current at the fault point under the permanent PTP fault under 100 Ω fault resistance is shown in Fig. 16.

It can be seen from Fig. 16 that the 1-mode voltage and the 1-mode current at the fault point change sinusoidally under the permanent inter pole fault with 100 Ω fault resistance, and their response characteristics conform to (18).

Construction of fault location equation based on distributed parameter model

(1) Pole-to-ground fault.

According to the analysis in Sect. 4.1.1, the mode domain equivalent network in case of PTG fault is shown in Fig. 17.

In the Fig. 17, Ua0, Ia0 are the 0-mode voltage and 0-mode current at side a respectively; Ub0, Ib0 are 0-mode voltage and 0-mode current at side b respectively; Ua1, Ia1 are the 1-mode voltage and current at side a respectively; Ub1, Ib1 are the 1-mode volt-age and 1-mode current at side b respectively; R00, L00, C00, R01, L01, C01 are 0-mode and 1-mode resistance, inductance and capacitance respectively; Ilf0, Irf0, Ilf1, Irf1 are 0-mode current and one mode current upstream and downstream of the fault point respectively; Uf0, If0 are 0-mode voltage and 0-mode current at the fault point respectively; Uf1, If1 are the 1-mode voltage and current at the fault point respectively.

According to Fig. 17, the 0-mode voltage and the 1-mode voltage at the fault point under the distributed parameter model are shown in (19).

Ilf0 and Ilf1 are shown in (20).

By introducing (19) and (20) into (15), If0 is the function of fault resistance Rf and fault distance x, as shown in (21).

From Kirchhoff current law (KCL) at fault point, Irf0 is shown in (22).

Since the remote end is in open circuit state at this time, the remote end current Ib0 = 0, so (23) can be obtained.

Combining (19) and (22), (24) can be obtained.

After finishing the above equation, Ib0 can be obtained as shown in (25).

A0, A1, A2, A3 in (25) is shown below.

To address the convergence challenges of iterative methods for solving the non-linear fault location Eq. (25), Taylor series is used to replace the hyperbolic function term with unknown x in this paper. To ensure model accuracy while enabling non-iterative solutions, this paper strategically truncates Taylor series expansions be-yond 4th-order terms due to the small γ0x and γ1x terms. The fault location equation is obtained as shown in (30).

B0, B1, B2, B3, B4, B5 in (30) is shown below.

If the real part and imaginary part of (30) are 0 respectively, (37) can be obtained.

Using (37) to eliminate the fault resistance Rf, the fault location for PTG fault can be obtained as (38).

where \({m_i}=Im({B_0})Re({B_i}) - Re({B_0})Im({B_i})\), i = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

The fault distance x can be obtained by solving (38), and the value range of x is 0 ≤ x ≤ l.

(2) Pole-to-pole fault.

According to the analysis in Sect. 4.1.2, the model domain equivalent network in case of PTP fault is shown in Fig. 18.

From Fig. 18, the expressions of the 1-mode voltage at the fault point and the 1-mode current upstream of the fault point are shown in (39).

Substituting (39) into (18), If1 is a function of fault resistance Rf and fault distance x, as shown in (40).

Based on KCL at fault point, the downstream current at fault point is shown in (41).

Since the remote end is in open circuit state at this time, the remote end current Ib0 = 0, so (42) can be obtained.

Combining (41) and (42), (43) can be obtained.

After finishing the above, Ib1 can be obtained as shown in (44).

A0, A1 in (44) is shown below.

Using Taylor series instead of hyperbolic function and ignoring the higher-order term of more than four times, (47) can be obtained.

B0, B1, B2, B3, B4, B5 in (47) is shown below.

If the real part and imaginary part of (47) are 0 respectively, (54) can be obtained.

Using (54) to eliminate the fault resistance Rf, the fault location equation for PTP fault can be obtained as follows:

The fault distance x can be obtained by solving (55), and the value range of x is 0 ≤ x ≤ l.

The above derived fault location equations are all univariate quartic equations, and the iterative solution method has convergence problems. Therefore, this paper us-es the Ferrari method to obtain the analytical solution. In addition, this paper uses LCC to inject the characteristic signal, so the filter algorithm is used to extract the line parameters at the injection frequency (20 Hz), which can mitigate the impact of line frequency variation parameters to a certain extent.

Solution of fault location equation for distributed parameter model based on Ferrari method

For solving the quaternion equation in one variable, the numerical method has the problem of iterative convergence, and the analytical solution can avoid this problem. At present, there are three most representative methods for solving analytical solutions, namely, Ferrari method, Descartes method and Euler method.

The Ferrari method was proposed by the Italian mathematician Lodovico Ferrari. Its core advantage is that through the ingenious variable substitution and order reduction strategy, the univariate quartic equation is transformed into a cubic auxiliary equation and a combination of two quadratic equations to solve. Thus, a complete theoretical framework of analytical solutions is constructed. This method is applicable to all forms of quaternion equation with one variable and has strong generality, but the amount of calculation is slightly larger34.

Descartes’ method was proposed by the French mathematician René Descartes. Based on the idea of factorization, Descartes’ method decomposes the unary quartic equation into the product of two quadratic equations. By assuming the decomposition form and comparing the coefficients, the analytical solution of the unary quartic equation is obtained by the elimination method. This method has a small amount of calculation, but it depends on whether the quartic equation can be decomposed into the product of two quadratic equations. There is an applicability problem for the equation that cannot be decomposed. In the actual solution process, it may need to guess or try the form of factorization, which increases the uncertainty.

Euler method was proposed by the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler. Its specific idea is to convert the quaternion equation of one variable into a simplified form, then introduce new variables. Using symmetry to transform the equation into a de-composable form, solve the transformed equation, and obtain the root of the quaternion equation. Based on the theory of symmetric polynomials and algebraic equations, this method has high mathematical value, but the requirement for the symmetry of the equation is too high. It has no advantage for the general form of monadic quartic equation. In practical application, its computational complexity and limitations make it less practical than the Ferrari method.

The advantages and disadvantages of the above three methods are comprehensively compared as shown in Table 1.

Taking the unary quartic equation x4 + 2 × 3 + 3 × 2 + 4x + 5 = 0 as an example, the time re-quired for solving the above three methods is further verified as shown in Table 2.

From Table 2, Descartes’ method needs to bring in the guessing factor of equation coefficient, while Euler’s method considers the symmetry of the equation and the calculation is complex. Therefore, the above two methods take longer time to solve than the Ferrari method. Therefore, considering the advantages and disadvantages of the above methods, considering that the fault location equation in this paper is a general form, the applicability of Descartes method and Euler method may exist. In this paper, the Ferrari method is used to solve the quaternion equation of one variable and generate the algebraic closed form expression, which avoids the inherent convergence test requirements of the iterative method.

To further illustrate the advantages of the Ferrari method over iterative methods, simulations were conducted from two aspects: solution time and memory usage. The specific results are shown in Table 3.

According to Table 3, the solution time used by the iterative method is about four times that of the Ferrari method, and the memory consumption of the iterative method is also greater than that of the Ferrari method. Therefore, using the Ferrari method to solve a univariate quartic equation not only avoids convergence problems, but also outperforms iterative methods in terms of computational speed and memory usage.

The specific steps of solving quartic equation with one variable by Ferrari method are as follows:

Both sides of (38) are divided by m4, (56) can be obtained.

where m4 ≠ 0.

Equation (56) is simplified as follows:

Transform (57), as shown in (58).

First, convert the left side of (58) to the complete square equation, as shown in (59).

The auxiliary variable y is introduced to make the original equation equivalent to (59), as shown in (60).

The equation is processed on the left side of (60) and simplified on the right side to obtain:

For ease of solution, at this time, we want the right side of the equation to be a complete square, so we need to make the equation Δ on the right side of the equation equal to 0, and (62) can be obtain:

Equation (62) is the univariate cubic equation of y, which can be solved by Kardan formula, and will not be repeated here.

When solving the descendant into the original equation, both sides of the original equation are complete square expressions. After that, two monadic quadratic equations can be obtained. It can be calculated by the root formula of quadratic equation of one variable, and will not be repeated here. Finally, the root seeking formula of the quaternion equation of one variable can be obtained as shown in (63).

Δ in (63) is shown below.

Δ1, Δ2 in (64) is shown below.

By introducing the coefficients of each degree in the fault location equation into the above rooting formula, the analytical solution of the quaternion equation of one variable can be obtained without iteration and consideration of convergence.

Implementation process of fault location method

The fault location method is constructed from the fault location equation con-structed above and the Ferrari method. The specific process is shown in Fig. 19.

As shown in Fig. 19, the specific process of fault location is as follows:

(1) If the line is judged to be a permanent fault, the polar electrical quantity is de-coupled into analog electrical quantity using the decoupling matrix shown in (10) and (11), and the analog electrical quantity is collected;

(2) The FIR band-pass filter is used to extract the line parameters under the injection signal (20 Hz);

(3) FFT is used for time-frequency domain transformation to obtain frequency domain information;

(4) The coefficient of the fault location equation is calculated according to the fault type, and the fault location equation is constructed;

(5) The Ferrari method is used to solve the fault location equation under the corresponding fault type;

(6) According to the actual fault distance, it should meet 0 ≤ x ≤ l to remove the pseudo root and output the fault distance.

Simulation verification

The electromagnetic temporary model of hybrid MTDC system is established in PSCAD/EMTDC, and the fault location method is verified by MATLAB. The line is the Frequency-dependent parameter model, and the system topology and specific parameters are shown in Fig. 20; Table 4 respectively. The sampling rate of the system is 10 kHz.

The definition of fault location error is shown in (66).

Performance of fault location method

The proposed fault location method is simulated and verified by taking PTG metallic fault and PTP metallic fault as examples. Take f1 on line L1 and f2 on line L2 as examples. The fault of line L1 is 15 km, 250 km, 475 km, 700 km and 935 km away from a-end respectively(f1-15, f1-250, f1-475, f1-700, f1-935). The fault of line L2 is 15 km, 140 km, 275 km, 410 km and 535 km away from c-end respectively(f2-15, f2-140, f2-275, f2-410, f2-535). The fault location results are shown in Table 5, and the fault location error is shown in Fig. 21.

The fault location results are shown in Table 5; Fig. 21. On the one hand, the distributed parameter model considers the influence of the line distributed capacitance current. On the other hand, the line parameters at the injected signal frequency are extracted by filtering algorithm, which avoids the influence of line frequency variation parameters to a certain extent. Furthermore, the analytical solution of the quaternion equation of one variable also avoids the problem of iterative convergence. Therefore, the error of the proposed fault location method is low. The simulation results validate that the proposed fault location method achieves sub-1% relative error across test scenarios.

Performance of fault resistance

Taking the PTG fault and the PTP fault as examples, the fault resistance is set to 100 Ω, 200 Ω, 300 Ω and 400 Ω respectively to verify the impact of the fault resistance on the performance of the proposed location method. The fault location is the same as that in 5.1. The fault location error is shown in Figs. 22, 23, 24 and 25.

From Figs. 21, 22, 23, 24 and 25 that although the location error of the proposed fault location method has increased under high resistance fault, the overall location error remains below 1%. Therefore, the proposed fault location method demonstrates exceptional immunity to fault resistance variations.

Performance of noise interference

Taking the PTG and PTP fault as examples, SNR is 40dB of noise and 400 Ω fault resistance are set to verify the impact of noise interference on the performance of the proposed method. The fault location is the same as that in 5.1. The fault location results of line L1 are shown in Table 6, and the fault location errors of lines L1 and L2 are shown in Fig. 26.

As shown in Table 6; Fig. 26, due to the strong randomness of Gaussian white noise, the fault location error increases significantly compared with that without noise. However, since the proposed method converts the time domain waveform into frequency domain data through FFT and uses band-pass filter to obtain the frequency signal, it achieves robust anti-noise performance. Therefore, the overall location error is still less than 1%.

Performance of different sampling rate

Taking the PTG fault and PTP fault of line L1 as an example, set the sampling rate to 5 kHz, 20 kHz, and set the fault resistance to 400 Ω, to verify the impact of sampling rate on the performance of the proposed method. Take fault f1 on line L1 and fault f2 on line L2 as examples. The fault of line L1 is 15 km, 475 km, and 935 km away from a-end respectively(f1-15, f1-475, f1-935). The fault of line L2 is 15 km, 275 km, and 535 km away from c-end respectively(f2-15, f2-275, f2-535). The fault location results of line L1 are shown in Table 7, and the fault location errors of lines L1 and L2 are shown in Fig. 27.

As demonstrated in Table 7; Fig. 27, the proposed fault location method maintains sub-1% localization accuracy even at reduced sampling rates (5 kHz), which is less affected by the sampling rate.

Performance of different boundary conditions

Taking the PTG fault and PTP fault of line L1 as an example, the smoothing reactor at LCC side is set at 100mH and 500mH respectively, and the fault resistance is set at 400 Ω to verify the impact of boundary conditions on the performance of the proposed method. The fault location is the same as that in Ⅴ-4. The fault location results of line L1 are shown in Table 8, and the fault location error results of lines L1 and L2 are shown in Fig. 28.

As demonstrated in Table 8; Fig. 28 that when the parameters of smoothing reactor at LCC side are changed, the proposed fault location method still has high location accuracy. Fault location method maintains sub-1% localization accuracy and is less affected by boundary conditions.

Performance of different line lengths

Taking the PTG and PTP fault of line L1 as examples, set the fixed fault of line L1 is 100 km away from a-end. And set the L1 line lengths to 200 km, 300 km, 400 km, 500 km, 600 km, 700 km, and 800 km respectively. At the same time, set the fault resistance to 400 Ω. The fault location results of line L1 are shown in Table 9.

According to Table 9, when the fault location is fixed at 100 km and the L1 line length is 200–800 km, the proposed fault location method can accurately calculate the fault location, with a fault location error of less than 1%. It can be concluded that the proposed fault location method is less affected by the line length.

Performance of HVDC system

Taking the HVDC system shown in Fig. 29 as an example, the applicability of the proposed method in traditional high-voltage direct current transmission systems is verified. The fault of line L1 is 15 km, 375 km, 750 km, 1125 km, 1485 km away from a-end respectively(f1-15, f1-375, f1-750, f1-1125, f1-1485). And set the fault resistance to 400 Ω. The fault location results of line L1 are shown in Table 10.

According to Table 10, the proposed fault location method has high positioning accuracy in HVDC systems and good applicability in HVDC transmission systems.

Performance of time-varying resistance

When a lightning fault occurs in a transmission line, the fault resistance can be approximately equivalent to time-varying resistance. Taking the PTG fault and PTP fault of line L1 as an example to verify the performance of the proposed scheme under the time-varying fault impedance scenario. The fault of line L1 is 15 km, 475 km, and 935 km away from a-end respectively(f1 − 15, f1 − 475, f1 − 935). The time-varying fault impedance is set as Rf = 200 + 50t Ω (t > tfault, tfault is the time corresponding to the initial instant of the fault). The fault location results are shown in Table 11.

According to Table 11, the proposed fault location method has a positioning error of less than 1% under lightning strike faults, indicating high positioning accuracy.

Comparative methods

To further illustrate the advantages of this method, it is analyzed and compared with the traveling wave method of12,13, the AI method of22,23, the impedance method of16,24, the fault analysis method of15,19. The specific comparison results are shown in Table 11. The location error in the Table 12 is calculated by (66).

As demonstrated in Table 12; the proposed method demonstrates significant ad-vantages over existing approaches. Primarily, it operates effectively at lower sampling rates. Secondly, employing Ferrari’s method for solving the fault location equations eliminates iterative convergence issues. Furthermore, the derivation based on distributed parameter modeling inherently accounts for both distributed capacitive currents and frequency-dependent parameter effects in long transmission lines. Notably, under interference conditions, the proposed method maintains superior localization accuracy with errors consistently below 1%, outperforming all comparative methods.

Conclusions

For hybrid MTDC system, a fault location method based on LCC signal injection strategy is proposed in this paper. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The proposed signal injection strategy changes the trigger angle to above 90° through emergency phase shifting after a fault occurs, quickly achieving fault current limiting. After a fixed delay waiting for the arc to extinguish, inject signal by changing the triggering angle sinusoidally. This injection strategy does not require PI control and has a faster response speed.

(2) The proposed method uses the characteristics of the modal domain components under different fault types. Based on the local electric quantity in the injected signal mode, the fault location equations of PTG fault and PTP fault in the distributed parameter model are derived respectively. The hyperbolic function in the fault location equation is replaced by Taylor series, and the multi-order fault location equation is written. The derived equation only uses single ended data, does not require communication between both ends, and is not affected by data channels. Due to the derivation through a distributed parameter model, it is not affected by the distributed capacitance current of the long line.

(3) The proposed method uses the Ferrari method to solve the fault location equation and obtain the analytical solution. There is no iterative convergence problem. Compared to the iterative method, the Ferrari method requires less time to solve, occupies less system memory, and imposes less burden on the protection system. In addition, the method uses filtering algorithm to extract the line parameters at the injected signal frequency, which is not affected by the frequency variation parameters to a certain extent.

(4) The simulation results show that the fault location error of the proposed meth-od is less than 1%. It still has high positioning accuracy under the interference of 400 Ω fault resistance and 40dB noise, and is less affected by the sampling rate and DC boundary, so it has strong robustness. In addition, this method is applicable to HVDC systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Wang, Y. L., Li, X. H., Li, H., Li, S. Y. & Zheng, Y. X. A constant extinction angle acceleration control method for suppressing continuous commutation failure. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 52, 56–66 (2024).

Yu, X. et al. A steady-state voltage control method for a multi-terminal hybrid UHVDC transmission system. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 50, 174–180 (2022).

Dai, Z. H. & Shi Xu. A pilot protection for hybrid HVDC transmission lines based on Voltage-Current sampling trajectory. Power Syst. Technol. 48, 2179–2188 (2024).

Zhang, Y. N., Luo, Y. P. & Hong, Y. Y. Multi-port DC circuit breaker-based fault clearing scheme for LCC-VSC hybrid multi-terminal HVDC systems. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 49, 146–153 (2021).

Li, H. F., Xu, C. X., Liang, Y. S., Lai, J. Y. & Wang, G. Backup protection design for multi-terminal hybrid HVDC lines considering control response. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 51, 155–163 (2023).

Mohammad, M. M. et al. Fault type classification in the presence of inverter-based resources: review, challenges and future works. IEEE Access. 13, 37051–37077 (2025).

Gil, M., Mohammad, M. M. & Ali, A. A. A new method for fault location in special parallel lines called stitched lines. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 227, 110003 (2024).

Zhang, Y. N., Hao, H. M., Li, J. & Li, L. Z. Fault location of HVDC grounding electrode lines based on combination of pulse injection method and single-ended fault travelling wave method. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 45, 117–122 (2017).

Zhang, S., Zou, G. B., Li, B. W., Xu, B. & Li, J. Fault property identification method and application for MTDC grids with hybrid DC circuit breaker. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 10, 136–143 (2019).

Yang, S. Z., Xiang, W. & Lu, X. J. An adaptive reclosing strategy for MMC-HVDC systems with hybrid DC circuit breakers. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 35, 1111–1123 (2020).

Song, G. B., Wang, T. & Hussain, K. S. T. DC line fault identification based on pulse injection from hybrid HVDC breaker. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 34, 271–280 (2019).

Wang, S., Shuai, Z. K., Li, Y., He, L. L. & Fang, C. C. Active injection DC fault location method based on solid state circuit breaker. Trans. China Electrotechnical Soc. 39, 2360–2370 (2024).

Li, B. et al. Fault location for flexible DC grid based on reclosing residual current breaker of DC circuit breaker. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 45, 140–148 (2021).

Xu, R. D., Song, G. B., Hou, J. J. & Chang, Z. X. Adaptive restarting method for LCC-HVDC based on principle of fault location by current injection. Global Energy Interconnect. 4, 554–563 (2021).

Hou, J. J., Song, G. B. & Fan, Y. F. Fault properties identification scheme for hybrid MTDC system based on LCC signal injection and distributed parameter line model. IET Gener Transm Distrib. 17, 3718–3738 (2023).

Liu, Z. Y. et al. An active converter injection-based fault location method for a flexible DC distribution network. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 51, 21–30 (2023).

Liu, K. Y., Ren, Z. Y. & Wang, Y. Fault location method for Multi-terminal flexible DC distribution network based on control and protection coordination. High. Voltage Eng. 49, 3458–3466 (2023).

Li, B., Sun, Q., He, J. W. & Li, Y. Fault location for grounding electrode line of MMC DC system based on harmonic injection. Power Syst. Technol. 44, 4773–4782 (2020).

Zhao, G. K., Jia, K., Chen, J. F., Chen, M. & Bi, T. S. A single terminal fault location method for a DC transmission line based on circuit breaker reclosing. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 49, 48–56 (2021).

Xue, S. M., Zhu, X. S. & Wang, S. X. Current Single-ended ranging protection of ring DC microgrid based on control and protection Cooperation. High. Voltage Eng. 48, 4959–4967 (2022).

Song, G. B., Hou, J. J. & GUO, B. Single-ended fault location of hybrid MMC-HVDC system based on active detection. Power Syst. Technol. 45, 730–740 (2021).

Hu, J. X. et al. Fault Location and Classification for Distribution Systems Based on Deep Graph Learning Methods. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 1135–1151 (2023).

Farkhani, J. S., Çelik, Q., Ma, K. Q., Bak, C. L. & Chen, Z. Fault Detection, Classification, and Location Based on Empirical Wavelet Transform-Teager Energy Operator and ANN for Hybrid Transmission Lines in VSC-HVDC Systems. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 13840–13851 (2025).

Zhang, X. H. et al. Fault location method for DC grounding electrode line based on Composite-frequency signal injection. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 48, 109–118 (2024).

Wang, L., Sun, X. F., Wang, B. C., Zhao, W. & Li, X. Research on protection scheme of DC line fault in LCC-MMC hybrid HVDC system. Proc. CSEE. 41, 7339–7352 (2021).

Liang, C. G. et al. Waveform difference based adaptive restart strategy for LCC-MMC hybrid DC system. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 37, 4237–4247 (2022).

Zhu, M. M. et al. Field test and analysis of delay characteristics of a DC electronic voltage transformer. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 51, 126–132 (2023).

Zhao, W. J., Xie, G. E. & Zeng, N. C. High Voltage Direct Current Transmission Engineering Technology 2nd edn 60–77 (China Electric Power, 2011).

Wang, T., Song, G. B. & Hussain, K. S. T. Adaptive Single-Pole Auto-Reclosing scheme for hybrid MMC-HVDC systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 34, 2194–2203 (2019).

Song, G. B., Rao, J., Gao, S. P., Cai, X. L. & Suo N.J.L. Monopole protection for HVDC transmission lines based on compensating voltage. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 37, 102–106 (2013).

Zheng, J. C., Wen, M. H., Chen, Y. & Shao, X. N. A novel differential protection scheme for HVDC transmission lines. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 94, 171–178 (2018).

Wang, P., Zhang, G. X., Li, L. Z., Zhu, X. M. & Luo, C. M. Error analysis of electronic instrument Transformers. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Science Technology). 47, 1105–1108 (2007).

Duan, M. Z., Liu, Y., Lu, D. & Pan, R. Y. A novel noniterative single-ended fault location method with distributed parameter model for AC transmission lines. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 153. (2023).

Su, T. T., Zhang, H. J., Wang, Y. K. & Qin, X. F. Dynamic picking algorithm based on ferrari༇s method for delta robot. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Tech. (Natural Sci. Edition). 46, 128–132 (2018).

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (52567016, 52442705), Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2022D01C662), Tianchi Talent Introduction Plan.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Junjie Hou: Conceptualization; Methodology; Funding acquisition; Project administration; Supervision. Chao Gao: Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Software; Validation; Visualization; Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing –review & editing. Yanfang Fan: Funding acquisition; Supervision. Guobing Song: Funding acquisition; Supervision. Xiaofang Wu: Supervision, Formal analysis. Chaowang Mu: Validation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, J., Gao, C., Fan, Y. et al. Fault location method for hybrid MTDC system based on LCC signal injection strategy. Sci Rep 15, 31769 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17375-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17375-6