Abstract

Seismic damage to gas pipelines can result in severe human, financial, and environmental impacts. A key strategy to mitigate these risks is incorporating regional seismic vulnerabilities into pipeline route design. Traditional methods often focus solely on minimizing distance from faults, overlooking the broader seismic hazard context. This paper presents a novel pipeline routing method that integrates probabilistic seismic risk assessment, incorporating primary consequences such as pipeline leakage and breakage, with a metaheuristic optimization algorithm within a GIS-based framework. The approach is applied to buried gas pipeline routing in the earthquake-prone region of southern Iran. The newly designed routes are compared to traditional designs, considering pipeline length, seismic exposure, and potential damage costs. Results demonstrate a reduction in physical damage risks and highlight the approach’s effectiveness in enhancing the resilience of pipeline infrastructure. This approach allows for a numerical incorporation of seismic risk into the routing of pipeline process, representing a significant improvement over the existing descriptive method.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural gas is essential for global energy, requiring efficient, safe, and environmentally friendly transmission. Pipeline transportation is the most common and effective method for moving natural gas from supply to demand centers1offering reliable long-distance delivery but remaining vulnerable to corrosion, natural disasters, and third-party damage2. Failures in gas pipelines can cause serious economic, environmental, and safety impacts3. Among natural disasters, earthquakes pose one of the important threats, especially in regions with high seismic activity4. Earthquake damage to gas pipelines, documented in major events such as the 1994 Northridge5, 1999 Izmit6, and 2016 Kaikoura7 earthquakes, seriously undermines the sustainability of transmission pipelines. These events caused major pipeline disruptions, leading to gas leaks, secondary damage, costly repairs, and indirect social and economic impacts8.

Earthquakes can trigger various hazards that threaten gas pipelines, including ground shaking, soil liquefaction, landslides, and ground failure. Ground shaking, caused by transient ground displacement (TGD), is a common hazard caused by earthquakes9. Hazards like landslides, soil liquefaction, and ground failure result from permanent ground displacement (PGD) and affect localized areas, whereas TGD hazards impact broader regions10. Assessing the seismic vulnerability of pipelines, often through post-earthquake observations, is crucial for mitigating earthquake impacts. Seismic vulnerability of pipelines is often assessed using empirical relationships based on earthquake intensity, with the repair rate (RR) serving as a key metric to quantify damage from seismic events11. Effective management of vulnerabilities is crucial to ensuring the integrity of natural gas pipelines in seismically active regions. Extensive research has focused on seismic vulnerability, emphasizing key factors such as pipe material properties12, diameter-to-wall thickness ratios13, and pipeline joint connections14. Additionally, the impacts of earthquake mechanisms15, soil liquefaction16, and landslides17 on pipeline vulnerability have been thoroughly investigated.

Seismic risk assessment integrates seismic hazard, structural vulnerability, and asset exposure to estimate potential earthquake-induced damage and losses. This assessment provides crucial information for designing more resilient pipeline systems18. Several studies have extensively analyzed the seismic risk of energy pipelines19,20 providing valuable insights and methodologies for assessing and mitigating potential impacts. For instance, comprehensive research such as seismic loss assessment of Iran gas pipeline21 evaluation of seismic hazards affecting gas transmission pipelines in the conterminous U.S22, and seismic risk analysis of the Azerbaijan (province of Iran) natural gas buried pipeline23. Ojomo et al.24 by focusing on landslides, addressed the seismic risk in gas networks in the United States. In addition to seismic risk assessment, the pipeline routes are a critical factor influencing their seismic performance, as pipelines often traverse geographically diverse areas.

Selecting the optimal pipeline route is a crucial step in the design phase of gas pipeline systems. This decision is an important part in minimizing the risk of failure and ensuring the long-term safety and reliability of the infrastructure throughout its operational life25. The most suitable route considers all relevant factors, including geopolitical issues, financial constraints, environmental impacts, and technical challenges. This process, known as route optimization, is essential for efficient and safe pipeline operation. Pipeline route optimization today employs multi-criteria decision-making techniques, which require large amounts of geographic data and complex analyses26. Geographic Information Systems (GIS) have replaced traditional models by providing efficient tools for managing, analyzing, and visualizing geospatial data to support these decisions. In particular, GIS utilizes the least cost path analysis, based on Dijkstra’s algorithm, to identify optimal routes. Research has demonstrated the effectiveness of this approach in pipeline routing, considering multiple criteria27. From a seismic perspective, several studies have investigated pipeline routing by considering various earthquake hazards using GIS and the least cost path analysis. For instance, the optimization lifeline routes concerning potential earthquake geohazards was conducted by Makrakis et al.25 and Alavi et al.26. On the other hand, in recent years, metaheuristic optimization algorithms have been increasingly applied to pipeline routing for various energy infrastructures28.

While numerous studies have analyzed seismic risk for operational pipeline systems in regions, a significant gap remains in incorporating comprehensive seismic risk considerations during the pipeline route design phase. Presently, route selection often depends on simplified criteria, such as maintaining clearance from active faults, which do not fully capture the complex interplay of seismic hazards, geological conditions, and environmental and social factors. However, this is only one aspect of a comprehensive approach to seismic criteria for pipeline routing. Other important factors include the sources of seismic hazard, parameters of ground shaking, and soil behavior. Integrating seismic risk assessment into the pipeline routing process overcomes the limitations of simplified methods by enabling detailed evaluation of potential earthquake-induced damage and its consequences26. This integrated approach enhances pipeline safety and resilience, supporting the development of robust infrastructure in earthquake-prone regions.

This study addresses the identified gap by proposing a novel pipeline routing framework that integrates seismic risk directly into the route optimization process using a metaheuristic algorithm and overcomes the complexities of the least cost path algorithm. To demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach, the proposed framework is applied to two pipeline routing case studies in southern Iran, a seismically active region influenced by the tectonic collision of the Eurasian and Arabian plates. The particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm is employed to identify optimal routes that minimize seismic failure risk and economic losses. The seismic risk assessment considers seismic hazards such as TGD and PGD, evaluating four specific seismic risk ranges corresponding to return periods of 75, 475, 975, and 2475 years, based on HAZUS methodology29. In addition to seismic risk, the framework accounts for critical factors such as topography, proximity to urban areas, environmental concerns, and geological conditions. The effectiveness of the method is demonstrated by comparing the optimized routes with existing ones based on pipeline length, failure rates, and earthquake-induced economic impacts. By explicitly integrating seismic risk into the design phase, this research offers a robust and practical approach to enhance pipeline resilience and safety in earthquake-prone regions, thereby filling a crucial gap in current pipeline routing methodologies. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In the second part, the development of the PSO algorithm for 2D route design is presented. The third part focuses on modeling seismic risk as a key factor in decision-making. The fourth part explains the proposed methodology and tool interactions, followed by a case study in the fifth part. The sixth part provides an analysis of routing results, the seventh part discusses findings and limitations, and the final part concludes with the key contributions.

Pipeline routing design

While the straight route between two locations is often the preferred pipeline route, practical factors complicate this ideal. The geographic features, economic factors, and technological constraints frequently necessitate more complex routing designs. On the other hand, environmental impacts and social considerations further require careful adjustments to ensure sustainable and acceptable pipeline routes30. Balancing the cost of construction, time, conservational protection, and considerations of technical-economic factors is a complex challenge. It demands an in-depth analysis that surpasses the limitations of existing approaches.

Pipeline routing determines the most efficient route between two points while meeting routing and safety requirements. Traditional algorithms like Dijkstra, A-Star, and Probabilistic Roadmaps either find a viable route or conclude none exists31. These algorithms lack adaptive learning, struggle with uncertainty, and demand high computational resources. Due to routing complexity and many influencing factors, metaheuristic methods provide a more effective solution32,33. The metaheuristic algorithms are computational techniques inspired by natural or biological processes, designed to systematically explore and pinpoint the most effective or near-best solutions in complex, large-scale problem spaces. These algorithms can effectively adapt to complex, changing environments where obstacles and objectives evolve. One of the best examples of a metaheuristic algorithm used in routing design is the PSO algorithm34,35. In this study, the PSO algorithm is selected due to its proven efficiency in handling complex, multi-constrained problems like pipeline routing. The PSO algorithm offers a good balance between global and local search, requires fewer parameters compared to other metaheuristics algorithms, and has shown reliable performance in various infrastructure-related applications36,37. The implementation of the algorithm in pipeline routing is presented in more detail below.

Pipeline route design using the PSO algorithm

PSO is a population-based algorithm inspired by swarm intelligence, which models the social behavior and collective movement patterns of organisms. Originally introduced in38, PSO simulates the dynamic interactions among individuals within a swarm to effectively guide the search process. PSO starts with a group of candidate solutions called a swarm, composed of individual entities known as particles. Each particle represents a potential solution to the optimization problem. Particles explore the optimization landscape within defined boundaries. Each particle updates its position by considering both its own experience and that of its neighbors to locate the optimal solution. Each particle’s position in the n-dimensional space is defined by its coordinates, and its movement is controlled by a velocity vector applied to these coordinates. The particles update their velocities and positions using specific equations, gradually moving toward the optimal solution. The concept involves guiding particles through the solution space to explore better positions, thereby minimizing the cost function values. This study employs PSO to design an optimal route for a buried energy pipeline in a 2D space, connecting two points: a start location and an end location. The next section presents the PSO implementation for pipeline routing, based on specific constraints and assumptions.

-

1.

Each particle represents a candidate pipeline route, defined by a series of n waypoints, with fixed start and end points.

-

2.

Each particle moves holonomically, allowing free travel in any direction within the search space.

-

3.

Routing criteria are incorporated either into the objective function or as constraints.

-

4.

While real-world conditions may differ, they are simplified in this study for modeling purposes.

Particle velocity and position are fundamental concepts in the PSO algorithm. In each iteration, a velocity vector representing incremental changes to the particle’s position coordinates is used to update the particle’s location in the search space. After moving to a new position, the cost function is evaluated. During each iteration, the lowest cost function value attained by each particle is recorded. This involves identifying the best position the particle has encountered throughout its history, commonly referred to as the particle’s best position. Furthermore, the algorithm determines the overall least value of the cost function across all particles, with the corresponding position referred to as the global best position. The velocity for each particle in the subsequent iteration is calculated using the global best position and the particle’s best position. The velocity update in the PSO algorithm is influenced by three main components. First, momentum maintains the current position, scaled by an inertia weight that decreases from 0.9 to 0.4 to shift from exploration to exploitation. Second, the personal best attraction directs the particle toward its best-known position, modulated by a learning factor and a random coefficient. Third, the global best attraction guides the particle toward the swarm’s best-known position, using a group learning factor and a random coefficient. These factors are combined in the new velocity of the i-th particle formula, as shown in Eq. (1).

where vit+1 represents the updated velocity of the i-th particle at iteration i + 1, while vit denotes its velocity in the current iteration. Pit indicates the current position of the particle, whereas PtpBest is the best position that the particle has visited so far, and PtgBest, represents the global best position identified by all particles. The parameters ε1 and ε2 are random vectors with values in the range [0, 1] for stochasticity; \(\odot\) denotes the Hadamard product of two matrices, while α1 and α2 are learning constants, generally set to 239, and w is the inertia weight according to34. The updated location of the waypoint is obtained by applying the velocity vector to its current position, as shown in Eq. (2). This velocity-driven position update allows each particle to explore new routes while being guided toward better solutions.

To ensure feasibility, only intermediate waypoints are updated, as the start and end points are fixed. The new position is constrained to a feasible region by clamping coordinates. If the updated route crosses an obstacle (e.g., a restricted zone), a penalty is added to the fitness score, or the waypoint is adjusted to a valid location.

Figure 1 shows a flowchart detailing the application of the PSO algorithm to the pipeline routing process. In this approach, particles are directed towards the most favorable positions found within the search space. Through successive iterations, the algorithm steadily moves closer to identifying the optimal solution.

Seismic risk assessment

This section outlines the core concept and methodology of seismic risk modeling and evaluates it based on earthquake conditions. Seismic risk is a comprehensive assessment that relies on three fundamental components: seismic hazard, exposure, and vulnerability. Through the investigation of tectonic and seismic conditions, hazard assessment identifies the potential impacts of an earthquake, including parameters such as TGD and PGD. Exposure, on the other hand, refers to the extent to which assets are subjected to different types of earthquake hazards. Vulnerability refers to the degree of damage that assets may experience when exposed to varying levels of hazard intensity22. Seismic risk assessment encompasses a wide range of impacts, including both primary and secondary consequences. In the case of gas pipelines, primary effects such as physical damage can lead to secondary outcomes like hazardous material release, fires, explosions, environmental degradation, and service interruptions. These secondary events may, in turn, cause broader societal disruptions, environmental harm, casualties, economic losses due to downtime, and other indirect consequences. However, evaluating these risks requires specialized methodologies and detailed data. Therefore, in this study, the seismic risk for pipelines is assessed based on immediate and primary consequences. Employing a probabilistic approach improves the reliability of seismic risk assessment by quantifying uncertainties in both seismic hazard and physical vulnerability using probability theory and statistical methods40. Next, the seismic risk assessment steps are elaborated in detail based on Fig. 2, based on HAZUS methodology29. HAZUS, developed by FEMA and the National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS), is a standardized methodology for estimating potential earthquake losses across U.S. regions. It combines seismic hazard analysis, structural vulnerability, and socio-economic impacts into an integrated framework. Although originally designed for North American geological conditions, HAZUS’s unique global integration of seismic parameters, empirical fragility data, and systematic analytical methods allows it to be adapted for other regions with appropriate calibration. In this study, region-specific soil classification data and suitable ground motion prediction equations were integrated to improve the model’s relevance to the seismic conditions of the case study. Additionally, parameters such as soil liquefaction susceptibility, pipeline structural properties, and joint types consistent with those used in HAZUS were incorporated where available, ensuring a more context-sensitive application of the methodology. The seismic risk results obtained through the HAZUS methodology, presented in this section, are directly used as a technical criterion for integrating seismic considerations into the pipeline routing process in the later stages of this study. In the following, the steps of seismic risk assessment are described in detail.

Seismic hazard analysis

Earthquakes can cause various hazards, depending on their intensity, geographic location, and tectonic characteristics. The primary cause of damage to critical infrastructure during an earthquake is TGD, which results from the propagation of seismic waves4. The PGD is another critical consequence of earthquakes, capable of triggering phenomena such as soil liquefaction, landslides, and ground instability. The combined and discrete effects of these hazards can compromise pipeline performance, leading to significant long-term costs21. In the context of seismic risk assessment for infrastructure, the investigation of TGD and PGD hazards is of primary importance and is presented in the following.

Earthquake hazards related to transient ground deformation

TGD, caused by seismic waves during an earthquake, reflects a momentary yet intense shaking of the soil. As a result of seismic wave propagation, it can extend over large areas, posing a significant threat to buried pipelines across various soil conditions. These effects are largely influenced by factors such as pipeline alignment, depth of embedment, and the characteristics of seismic wave propagation9. The primary cause of strain in buried pipelines during seismic loading is the strong confinement from the surrounding soil, which restricts pipe movement and generates significant internal stresses. To assess this hazard, HAZUS29 utilizes peak ground velocity (PGV), a key parameter influencing pipeline deformation and strain during seismic events. PGV can be estimated through various methods, including acceleration integration, ground motion prediction equations, and response spectrum analysis. However, these approaches involve uncertainties due to data noise, simplified soil behavior models, and indirect estimations, which can affect the accuracy of seismic hazard assessments for buried pipelines41. To overcome these challenges, HAZUS29 proposes an empirical equation based on spectral acceleration at a 1.0-second period, SA(1s), as shown in Eq. (3). The factor 1.65 in the denominator of Eq. (3) represents the median amplification between peak spectral response and PGV for a 5%-damped system in the velocity region, according to Newmark and Hall42.

Earthquake hazards related to permanent ground deformation

PGD often results from geotechnical processes such as liquefaction, ground settlement, and slope failures. While PGD hazards typically affect small segments of pipelines, they can cause severe damage by inducing large deformations. Soil liquefaction, which occurs when earthquake shaking increases pore-water pressure, causing saturated soils to lose strength, has caused significant damage to buried lifelines in past earthquakes10. The first step in identifying this hazard is to classify areas according to their liquefaction susceptibility. PGD can be assessed by combining soil liquefaction susceptibility maps with HAZUS29 to estimate the liquefaction probability for each category. The probability of soil liquefaction at any given location depends on the soil’s sensitivity and the intensity of seismic shaking. For each susceptibility class, this probability can be calculated using Eq. (4), which is derived from statistical modeling based on an empirical liquefaction catalog43.

In this context, P[Liquefaction|PGA = pga] captures the conditional probability that liquefaction will occur within a given susceptibility zone at a specific level of peak ground acceleration (PGA). The factors KM and KW act as essential correction parameters, accounting for earthquake moment magnitude and groundwater depth, respectively, as defined in Eqs. (5) and (6)44. The parameter, Pml, represents the proportion of a mapped area that is susceptible to liquefaction. Liquefaction sensitivity is classified into four distinct levels: 0 for none, 0.05 for low, 0.1 for moderate, and 0.2 for high, representing the corresponding values of sensitivity across all categories29.

Here, dw denotes groundwater depth in feet, and M represents the moment magnitude at each location, determined based on the maximum expected magnitude of the seismic source in the region. The final step calculates the PGD due to liquefaction based on the PGA, using Eq. (7). In this equation, PGA(t) refers to the threshold PGA required to trigger liquefaction, as defined by HAZUS29. Unlike standard PGA values, PGA(t) is not the measured ground acceleration but a threshold value that depends on site-specific conditions and is used as a criterion for assessing the liquefaction potential. Equation (7) applies to a moment magnitude of 7.5 and can be adjusted for other magnitudes using KΔ from Eq. (8). Multiplying KΔ by Eq. (7) gives the modified PGD due to soil liquefaction.

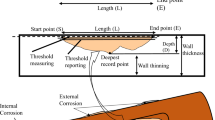

Seismic vulnerability analysis

Effective seismic risk evaluation necessitates the integration of hazard intensity, asset exposure, and the associated vulnerability corresponding to each hazard level. As outlined in HAZUS29 the assessment of seismic damage to pipelines does not consider factors such as pipe diameter, classification, or mechanical properties. Instead, it relies solely on a broad classification of pipelines as either brittle or ductile. For pipelines, damage is generally classified into two states: leak (DS1) and break (DS2)29. Typically, PGD-induced damage is more likely to cause breaks, while TGD-related damage is more commonly associated with leaks. This distinction highlights the differing responses of pipelines to the two types of seismic hazards. For TGD hazards, seismic vulnerability is typically characterized by approximately 80% leakage and 20% breakage, while the opposite distribution is observed for PGD hazards. The seismic vulnerability of pipelines is quantified using the RR, which represents the number of repairs required per unit length of pipeline4. Equations (9) and (10) describe the relationship between RR and the two types of seismic hazards, TGD and PGD, based on PGV and PGD, respectively45,46.

Here, PGV is measured in cm/sec and PGD in inches. The length of a pipeline segment is crucial in determining its failure probability, which is modeled using the exponential Eq. (11) 4.

In this context, L, RR, and Pf are the pipe length (in kilometers), the repair rate, and the probability of failure, respectively. Equation (12) is employed to calculate the joint exceedance probabilities in the context of a multi-hazard assessment.

Here, h denotes the type of seismic hazard, and n represents the total number of hazards considered in the vulnerability assessment. The expected damage states are calculated by aggregating the discrete probabilities of each damage level, as shown in Eq. (13).

Loss assessment

According to HAZUS29direct economic losses from physical damage are calculated by combining the probability of each damage state (P[ds = DSi]) with the pipeline replacement value (RV) and the corresponding seismic damage ratio (DRi). The economic loss (EL) is then determined using Eq. (14).

The compounded damage ratio is calculated using Eq. (15) by integrating individual damage ratios through a probabilistic approach.

Equations (14) and (15) is used to calculate the probability of being in damage state i (P[ds = DSi]). Table 1 presents the associated damage ratios and estimated RVs for the general buried pipeline.

The proposed methodology

This study introduces a novel approach for pipeline route optimization by incorporating seismic risk into the routing process. Accordingly, “Pipeline routing design” section presents the development of the PSO algorithm in a 2D space, enabling it to perform effective pipeline route design. Given the critical role of seismic engineering criteria in pipeline routing, “Seismic risk assessment” section provides a comprehensive modeling of seismic risk, treating it as a key factor in the decision-making process. This section further outlines how the components developed in “Pipeline routing design” section and “Seismic risk assessment” section interact alongside other technical criteria to form an integrated methodology for designing a seismically optimized and reliable pipeline route. This section presents the proposed methodology for modeling and routing pipelines with seismic risk as a key consideration. The ultimate goal is to determine the most efficient pipeline route that ensures minimal exposure to seismic risk. The methodology comprises six steps:

(1) Compilation of current pipeline routing criteria.

(2) Seismic hazard analysis.

(3) Determination of seismic vulnerability.

(4) Network formation and spatial segmentation.

(5) Pipeline routing using a metaheuristic method of GIS-based routing.

(6) Evaluation of the designed route.

To ensure safe pipeline routing within the study area, a series of structured steps is followed. Each step is detailed in the sections below.

Compilation of current pipeline routing criteria

The first step involves the compilation of existing spatial criteria that influence pipeline routing. These criteria are broadly categorized into technical, environmental, and social aspects. Technical factors include topography, elevation, slope, land use, and proximity to man-made structures (e.g., roads, urban areas). Environmental criteria account for protected areas and ecological sensitivity, while social criteria consider population density and land ownership. A comprehensive spatial data inventory is developed by sourcing data from national agencies such as the Geological Survey of Iran (GSI) and the National Cartographic Center (NCC). These spatial datasets are processed within a GIS environment to produce thematic layers that serve as the foundation for subsequent hazard and vulnerability analysis. This step ensures the integration of existing routing knowledge with spatial constraints and decision-making layers. One of the most important inputs identified here is the seismic zoning layer, which will guide risk-sensitive routing in the next steps.

Seismic hazard analysis

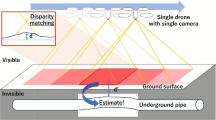

In this step, a detailed seismic hazard assessment is conducted to identify and quantify earthquake-induced ground hazards commonly categorized into wave propagation and ground failure that may impact potential pipeline routes. This involves evaluating both TGD and PGD hazards. To support this evaluation, seismic hazard modeling is performed using a variety of geospatial and geotechnical data, including seismicity, fault distribution, soil liquefaction susceptibility, and dynamic soil properties such as soil type and shear wave velocity in the upper 30 m of the ground. The dynamic characteristics of each study area can be incorporated as input into the seismic hazard analysis process to enable a more accurate estimation of strong ground motion intensity. Probabilistic seismic hazard analysis (PSHA) is conducted to investigate wave propagation hazards, resulting in the zoning of strong ground motion intensities like PGA and SA(1s). Since pipelines are extensive and buried at depth, ground displacement exerts a greater impact on them than ground acceleration. According to HAZUS methodology29 TGD hazard is represented by PGV, as buried infrastructure like pipelines is more sensitive to ground velocity than acceleration, as shown in Eq. (3). Empirical studies further support this by showing that PGV correlates more strongly with structural damage than other seismic intensity measures, making it a more reliable indicator for TGD hazard41. In addition, ground deformation resulting from soil liquefaction, along with the expected PGD, is calculated based on the region’s susceptibility to soil liquefaction and PGA, as defined by Eq. (4) through (8).

Seismic vulnerability analysis

Following hazard identification, this step evaluates the seismic vulnerability of buried pipelines by quantifying potential damage resulting from both TGD and PGD hazards. The RR is used to quantify the severity of pipeline vulnerability, with empirical RR relationships estimating the frequency of pipeline failure based on strong ground motion mechanisms. Two damage states of leak and break are considered to express the vulnerability of the pipeline due to TGD and PGD hazards29. For TGD hazard, the vulnerability is primarily due to wave-induced vibrations. An RR–TGD model, presented in Eq. (9), is used to estimate the expected number of pipeline failures per kilometer based on a given level of PGV, while an RR–PGD model, defined in Eq. (10), is applied to estimate failures per kilometer corresponding to the intensity of PGD. Subsequently, the probability of failure for each damage state is independently evaluated for PGD and TGD hazards, as shown in Eq. (11). Thereafter, the joint probability of failure resulting from the combined effects of both seismic hazards is determined, assuming the hazards are independent, using Eqs. (12) and (13) to provide a more accurate representation of the likelihood of each damage scenario. Finally, utilizing these damage probabilities, the economic losses attributable to physical damage of the pipeline are assessed using Eqs. (14) and (15), serving as a key metric for evaluating the pipeline routing alternatives. In the next step, the method developed in this research is presented for pipeline routing.

Network formation and Spatial segmentation

This stage initiates the pipeline routing process by systematically organizing spatial data into a structured, analyzable format. The study area is divided into a uniform grid system, converting complex geospatial datasets into raster format to facilitate efficient spatial analysis and integration. Each cell in this grid represents a distinct geographic segment and contains key attributes such as elevation, land use type, accessibility indices, and other technical, environmental, and social criteria outlined during the spatial data collection phase (Fig. 3a). This gridding approach standardizes diverse datasets, allowing seamless overlay and analysis across various data types. Furthermore, this discretization improves computational performance by converting continuous spatial data into manageable units, enabling faster processing in subsequent modeling steps. The resulting raster layer captures the physical and socio-environmental characteristics of the region, providing a comprehensive foundation for vulnerability and hazard assessments. This process is visually illustrated in Fig. 3b, where spatial data is compiled and prepared for seismic hazard evaluation.

Pipeline routing using a metaheuristic method of GIS-based

A comprehensive framework is developed to mathematically model the pipeline routing problem. This framework systematically represents the problem, ensuring that the routing process complies with predefined design criteria and constraints. The approach formulates pipeline routing as an optimization problem, aiming to identify the most efficient route while balancing multiple, often conflicting criteria. The details of the optimization components are presented in the following.

Objective function

The pipeline route optimization in this study focuses primarily on two key factors: seismic risk and route length. The objective function is formulated to minimize overall routing costs by balancing the economic impacts of seismic-induced failures and the expenses associated with pipeline construction, as expressed by Eq. (16). This approach ensures the selection of cost-effective routes that prioritize safety and resilience alongside economic considerations.

where li is the length of the i-th part of the pipeline, n is the number of pipeline sections. The a1, a2, and a3 represent the cost coefficients for the pipeline’s length, leakage, and breakage, respectively. This holistic cost metric guides the search for routes that optimize both economic efficiency and structural resilience.

Constraint condition

Real-world pipeline routing faces various constraints that must be embedded in the optimization model.

-

1.

Connectivity should be ensured between the pipeline’s source and destination points.

-

2.

Spatial restrictions are modeled through a binary raster layer derived from the network formation step. Grid cells are classified as either passable (0) or restricted (1), reflecting natural (e.g., environmental protection zones, fault lines), technical (e.g., terrain slope, soil erosion), and social constraints (e.g., urban proximity). However, the raster datasets have fixed resolution, and higher-resolution data may not be available. Due to fixed raster resolution and partial coverage of obstacles within cells, the model applies neighborhood averaging to smooth classification and reduce false positives in obstacle detection. This binary logic framework is critical for maintaining realistic routing constraints. In practice, routes may unavoidably cross restricted areas. To manage this, the model assigns penalty coefficients in the objective function, allowing flexible and realistic handling of various constraints. In Fig. 3b, red cells indicate transmission constraints, while other cells have no transmission constraints. The resulting raster layer, containing gridded area information and routing criteria, forms the basis of the routing process. These constraints are considered for each cell after forming the raster network using the binary zero and one method.

How the PSO algorithm works in routing

The PSO metaheuristic algorithm is employed to efficiently explore the solution space. Initial candidate routes are generated as sequences of spatial coordinates between source and destination points, representing potential pipeline routes in Eq. (17).

where (xs,ys,Cris), (xD,yD,CriD), the coordinates and criteria information of the source and destination points are fixed, while the remaining points represent random positions through which the pipeline route passes. Each route is evaluated based on its interaction with obstacles encountered along the route, such as roads, rivers, faults, terrain slopes, and other geographical features. The algorithm iteratively evaluates a set number of candidate routes (using Eqs. (1) and (2) ), selecting the optimal one based on the minimal number of encountered obstacles. This process accounts for the inevitable presence of obstacles, particularly at intersections, within the pipeline routing context. Through successive iterations, the algorithm refines candidate routes to identify the most efficient route. That minimizes obstacle interference and reduces seismic risk, thereby optimizing seismic stability (see Fig. 3b). Given a pipeline route, G, this study defines the criteria function g as the following line integral along the G route (Eq. (18)).

where e(g) represents the criteria cost at a point g along route G, depending solely on the geographical location and criterion information of each cell r. By employing a binary logic framework, the algorithm selects routes that keep G close to zero, as specified. This approach ensures improved seismic structural integrity and safety. G represents the cumulative cost of traversing different points, calculated as the sum of the constraints. While it is impossible to completely avoid constraints in a real-world problem, they can be minimized to approach zero.

Evaluation of the designed route

The final step involves quantitatively assessing the designed pipeline routes relative to existing routes. Evaluation metrics include total route length and calculated seismic risk factors derived from the earlier seismic hazard and vulnerability models in number of failures and seismic economic loss. Routes generated by the GIS-based PSO framework are compared by their objective function values, those with higher costs than the current existing route are excluded from further consideration. This comparative analysis ensures that proposed routes not only reduce seismic exposure but also maintain economic and logistical viability. The GIS-based routing framework proposes routes with reduced seismic risk, as illustrated in Fig. 4.

A case study

This section applies the proposed method to two routing cases in the southern region of Iran (Fig. 5). This region is located in the active seismic zone of the Zagros Mountains, caused by the collision between the Eurasian and Arabian tectonic plates48. The following section outlines and describes the steps of the proposed methodology for the case study area.

Seismic risk modeling

This study uses four hazard levels with return periods of 75, 475, 975, and 2475 years for seismic risk assessment, though the method can be adapted to accommodate other hazard levels if needed. The following sections provide a detailed explanation of the seismic risk assessment for the study area.

Seismic hazard analysis

Strong ground motion can be characterized using a wide range of intensity measures. However, each hazard, such as TGD and PGD, exhibits stronger correlations and greater sensitivity to specific intensity parameters. Various tools and methodologies are employed to identify relevant hazard parameters and estimate their values. Among these, PSHA is widely recognized as a standard approach for estimating the intensity of different strong ground motion parameters, taking into account the seismic background of the region. This study uses the OpenQuake engine49 to perform PSHA, estimating exceedance probabilities and ground motion intensities related to TGD and PGD hazards. As recommended by HAZUS29, SA(1s) and PGA represent intensity measures correlated with TGD and PGD, respectively. Identifying seismic sources and their seismicity parameters is the first step in PSHA. In this study, seismic sources are classified into linear and area sources. For defining the geometry and seismic parameters of area sources, this study utilizes the earthquake catalog provided by the International Institute of Earthquake Engineering and Seismology50 covering the period from 1926 to 2020, that shown in Fig. 6a. The Iranian guideline (No. 626) is applied to remove foreshocks and aftershocks and to adjust mainshock magnitudes. The geometry and seismicity of area sources are defined by analyzing earthquake distributions and their association with regional faults, and characterized using the Gutenberg-Richter relationship (a and b values). Faults are considered the principal sources of seismic activity in line source models. Seismic parameters of linear sources in this study are adopted from the EMME database51. Both seismic source models are presented in Fig. 6b. All seismic sources have a minimum moment magnitude of 4.5.

Following the characterization of seismic sources, four ground motion prediction models recommended by the EMME project52,53,54,55 are applied to estimate the expected intensity measures at the site51. A logic tree approach is employed to represent epistemic uncertainties in the seismic hazard analysis, assigning weights of 35% to linear sources and 65% to area sources in this study. Although the ground motion equations used were not explicitly developed for Iran, they are based on data from the EMME project51 and demonstrate satisfactory compatibility with the study region, particularly the southern Zagros area. However, due to data limitations inherent in each model, the coefficients have been adjusted within a range of 0.1 to 0.3 through a ranking process to better reflect regional seismic characteristics and address varying levels of model uncertainty. The overall process of PSHA is described in Fig. 7.

This section aims to develop a seismic hazard map by evaluating the probability of seismic events in the study area. To accomplish this, specific sites are selected based on their sensitivity metrics as defined by Alavi et al.56 with one site chosen in each 0.08-degree interval of longitude and latitude. The seismic hazard assessment for each site considers all active seismic sources within a 150 km radius. Following the estimation of PGA and SA(1s), kriging interpolation is applied to develop the seismic hazard zoning map57. SA(1s) intensity is used to model TGD, while PGA intensity models PGD. Using Eq. (3) and the calculated SA(1s) values, the PGV map for the study area is generated, as shown in Fig. 8.

Using the soil liquefaction susceptibility map, the probability of soil liquefaction and the corresponding PGD can be estimated through the HAZUS29. Figure 9a presents the soil liquefaction susceptibility map of Iran, developed by the IIEES, which is employed in this study. Based on Fig. 9a and Eq. (4), the PGD values corresponding to various return periods are determined. The PGD caused by soil liquefaction for a 475-year return period is illustrated in Fig. 9b.

PGD hazard estimation in the studied area, (a) Soil Liquefaction susceptibility map58(b) PGD hazard map.

Seismic vulnerability analysis

Using Eqs. (9) and (10), RR maps for the study area are generated for various return periods. The maps corresponding to TGD and PGD damages for the 475-year return period are shown in Fig. 10a and b, respectively.

Pipeline routing criteria overview

Gas pipeline routing is influenced by multiple factors, and identifying the optimal route requires a comprehensive assessment of their interactions. Key considerations in gas pipeline routing include identifying the relevant criteria that influence route selection, quantifying their impact, and acquiring the corresponding spatial datasets. Although the routing process is inherently complex, the selection of input factors is largely constrained by data availability, spatial resolution, and computational capacity. It is important to note that, although numerous factors can influence gas pipeline routing, this study considers only those for which reliable and readily accessible data are available. The selected criteria are categorized into seven groups, adapted from the works of Yildirim et al.59 and Arabi and Gharehhassanloo30 as presented in Table 2. All sub-criteria are projected into a common coordinate system (UTM Zone 39 N) to ensure spatial consistency. In GIS, spatial data are generally classified into two main types: vector and raster. Vector data are represented by three basic geometries, points, lines, and polygons, used to model discrete spatial features. In contrast, raster data consists of a matrix of cells or pixels arranged in rows and columns, with each cell containing a value that represents specific spatial information. Raster formats are particularly well-suited for representing continuous spatial phenomena. In this study, raster datasets are derived from the vector datasets listed in Table 2 by applying GIS-based spatial analysis and data conversion tools. All criteria, except seismic vulnerability, are treated as constraints. Routing is shaped by safety, environmental, and regulatory factors that limit route options. This study incorporates the specific constraints linked to each criterion. These include minimum buffer distances of 250 m for environmental and communication-related features, and buffer zones of 1000 and 2000 m for population centers and fault lines, respectively. For the geology criterion, pipeline routing is restricted from traversing areas characterized by highly erodible soils, as well as land designated for agriculture, residential use, forests, and water bodies. In terms of topography, routes with slopes exceeding 30 degrees are excluded. These restrictions are derived from the standards set by the National Iranian Gas Company, such as IGS-C-TP-001 and IGS-C-PI-001. Additionally, areas with lower seismic vulnerability are preferred to reduce potential seismic risks. Next, a grid is created over the study area, with criteria-related data recorded at the center of each cell for four different seismic risk levels. All criteria except for geology, which is excluded from the visual presentation due to its complexity and numerous attributes, are illustrated in the following section, based on the characteristics of the study area. The land use criterion includes categories such as agricultural land, orchards, airport areas, dry farming, various forest densities, settlement zones, productivity ranges, and fallow lands. Soil erosion is classified into eight levels, ranging from very low to very high.

Result

Figure 11a shows the source and destination locations for the two routing problems analyzed in this study, along with the existing routes for each case. These routes, developed using traditional methods, serve as benchmarks for evaluating the efficiency of the proposed approach. The gas pipelines in Fars Province are important branches of Iran’s national natural gas network. They carry gas from major production and processing centers in southwestern Iran to various consumption points in Fars and beyond. These pipelines supply urban areas, industries, and power plants, ensuring reliable energy delivery. Due to Fars Province’s strategic and economic significance, these pipelines support both local and national development. Their safe operation is crucial for meeting energy demands and fostering regional growth. Figure 11a provides a visual representation of the two routing problems and their existing routes, while Fig. 11b illustrates the routing criteria within the study area. The proposed approach enables seamless integration of seismic risk evaluations at any specified hazard level as an informational layer within the routing process. This study evaluates four risk levels corresponding to return periods of 75, 475, 975, and 2475 years for each routing problem. In route labels, ‘DR’ denotes Designed Route, followed by the risk level’s return period, while ‘ER’ refers to the Existing Route. It is important to note that, due to the sensitive nature of pipeline infrastructure, detailed data on existing pipelines is limited to general location and configuration. However, the available information is appropriate for this study. For a thorough comparison of designed and existing routes, evaluated for each route, considering two earthquake-related hazards: TGD and PGD. Each route’s seismic performance is evaluated by combining the two damage states and hazards, labeled as DS1-TGD, DS1-PGD, DS2-TGD, and DS2-PGD. Comparison metrics include pipeline length, seismic risk, and economic losses for a 475-year earthquake return period. The following subsections provide detailed descriptions of the routing problems and their evaluations.

Pipeline routing – case study 1

Figure 11c presents four alternative routes developed for the first case study: DR-75, DR-475, DR-975, and DR-2475. These routes represent deviations from the existing pipeline route, as illustrated in the figure. Figure 12 compares the lengths of the designed routes with the existing pipeline. The designed routes are approximately 3% shorter than the existing pipeline route, with DR-75 emerging as the shortest among them.

The pipeline routes designed based on varying levels of seismic risk are compared with the existing route under a hazard level corresponding to a 475-year return period. As illustrated in Fig. 13, the spatial distributions of PGV and PGD along these routes are presented. Notably, the pipeline endpoints are located in areas with relatively higher seismic hazard compared to the central segments of the routes. However, the newly designed routes tend to be more elongated through regions with lower seismic hazard, thereby reducing the potential for damage along the pipeline route.

Figure 14 compares the seismic risk of the newly designed pipeline routes with that of the existing route, based on damage levels caused by seismic events. The results show that in DS1, the designed routes experience a 2.7% reduction in seismic risk, while in DS2, the reduction is approximately 2%. This reduction can be scientifically attributed to the optimization of the pipeline route, which directs the pipeline through regions with lower seismic hazard levels, such as areas with lower PGV and PGD. Moreover, the selected routes pass through geologically stable areas with lower soil amplification potential, reducing the seismic demand on the pipeline structure. Figure 15 complements this analysis by presenting the seismic economic losses associated with each route, including direct repair costs. The designed routes exhibit, on average, 2.5% lower economic losses compared to the existing route. This advantage results from a combination of reduced physical damage and enhanced network resilience, leading to faster recovery and lower repair costs following seismic events.

Pipeline routing – case study 2

Figure 11d presents four designed routes developed for the third case study. Notably, the existing route traverses a region highly susceptible to soil liquefaction. Given the heightened risk of displacement caused by liquefaction, the routing algorithm prioritizes designing routes that avoid highly susceptible areas and instead pass through zones with lower soil liquefaction sensitivity. Figure 16 compares the lengths of the designed routes with the existing one, showing that the newly designed routes are approximately 4.65% shorter.

Fig. 17 illustrates the hazard distribution map at the 475-year return period for both the existing route and the designed routes. While the PGV hazard distribution appears generally limited and similar across all routes (see Fig. 17a), the variation in PGD hazard is significantly more pronounced in the designed routes compared to the existing route, according to Fig. 17b.

As shown in Fig. 18, the designed routes demonstrate a 5.6% reduction in seismic risk compared to the existing route under DS1. Notably, under DS2, which represents more severe damage scenarios, the reduction reaches approximately 51%, indicating a substantial improvement in seismic performance. This significant reduction can be largely attributed to the fact that the existing route passes through areas highly susceptible to soil liquefaction. It appears that in the original route planning, liquefaction hazard was not adequately considered, which has led to elevated seismic vulnerability, particularly under high-intensity ground motions. In contrast, the designed routes were optimized with explicit consideration of soil liquefaction risk. As a result, the alignment of these routes tends to avoid areas with high liquefaction susceptibility and instead shifts toward zones with more stable soil conditions. This strategic adjustment is especially evident under higher hazard levels, where the effect of soil liquefaction becomes more critical.

Figure 19 compares the seismic economic losses of the routes, showing that the designed routes reduce economic losses by about 46.7% relative to the existing route. While the reduction in break risk (DS2) observed here is significant, it is important to recognize that this result is specific to the conditions of the current study and may not be directly applicable to other regions or projects. Despite this, the significant reduction demonstrates the promising capability of the proposed method to enhance seismic safety, serving as a strong qualitative indicator of its effectiveness.

Discussions

Considering the vital performance of gas pipelines, the introduced method offers a strategic solution for determining more efficient and reliable routing options. Consequently, it enhances the quality and safety of decision-making in routing operations. The approach delivers a detailed and quantitative analysis of seismic risk for gas pipeline route planning. This approach provides a mathematically rigorous solution that directly minimizes costs and seismic risk, rather than relying on subjective weighting or pairwise comparisons. However, the approach is subject to certain limitations, categorized into three main areas: (a) In the geographical data, the performance of the proposed method in identifying optimal routes improves significantly with higher-resolution geographical data. (b) In the objective function, employing a more comprehensive objective function can lead to better route identification. For example, in one of the case studies, the suggested pipeline route demonstrated a higher risk of leakage but a reduced risk of break compared to the existing route. This discrepancy arose from variations in the costs associated with leakage and breakage, which were accounted for in the objective function. (c) Earthquake-related hazards such as ground shaking and ground failure based spatial cross-correlation of their intensity60. Moreover, the RR relationships provided in HAZUS29 which are derived from limited empirical data, further constrain the accuracy of vulnerability assessments. To improve accuracy, analytical RR models can be developed for pipeline types used in different regions. The proposed routing algorithm intentionally prioritizes pipeline routing through zones with lower PGD susceptibility, even if this results in a marginal increase in exposure to seismic wave-induced leakage. This approach is further justified by the sensitivity of the objective function to rupture-related losses, which carry greater weight due to their higher severity and potential economic impact. On the other hand, the implementation of the proposed method results in the design of routes for various seismic risk levels that not only reduce the total pipeline length but also exhibit lower seismic risk compared to the existing pipelines. Although the extent of risk decrease falls within a specific and relatively limited range, it is considered highly significant in the context of pipeline design, especially given its positive implications for both cost efficiency and safety. Future studies can integrate relevant data on these hazards using appropriate methodologies to enhance the model’s accuracy and reliability.

Conclusions

This study aimed to develop a robust and risk-informed routing method for gas pipelines by integrating GIS with a PSO algorithm, with a particular emphasis on minimizing seismic risk. Given the critical importance of natural gas pipelines in energy supply, especially in seismic regions, the study addressed the need for risk-informed routing that accounts for potential earthquake-induced damage. The method evaluates TGD and PGD hazards probabilistically and is applied to three case studies, comparing optimized and existing routes by length, seismic risk, and economic loss. The significant findings are as follows:

-

1.

The optimized routes exhibit significantly lower seismic risk levels compared to existing ones, confirming the method’s capability to avoid high-hazard zones.

-

2.

Findings from the proposed method indicate that incorporating higher hazard levels in the design process leads to lower seismic risk, primarily due to enhanced structural resilience achieved by accounting for more severe seismic scenarios. Consequently, routes designed with consideration of more severe seismic scenarios demonstrate reduced overall seismic risk, primarily due to enhanced structural resilience achieved through improved avoidance of vulnerable areas and increased robustness.

-

3.

Each of the newly designed route’s results in lower seismic damage costs relative to the existing routes. The value of cost reduction, however, differs notably among the two case studies due to various influencing factors. Across two case studies, the proposed routes yield lower seismic damage costs than the existing ones. Nonetheless, the value of this decrease differs considerably among the three case studies. A key contributing factor to this variation is the level of soil liquefaction susceptibility in each region, which plays a significant role in determining the potential for seismic damage.

The developed GIS–PSO framework provides a practical, hazard-aware solution for seismic risk reduction in pipeline routing. It demonstrates strong potential for enhancing infrastructure resilience in earthquake-prone areas. Future research may focus on expanding the methodology to include additional hazard types, socio-environmental constraints, and integration with real-time geospatial data. Limitations such as the reliance on available hazard maps and assumptions in damage cost estimation should be addressed in subsequent studies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

References

Ríos-Mercado, R. Z. & Borraz-Sánchez, C. Optimization problems in natural gas transportation systems: A state-of-the-art review. Appl. Energy. 147, 536–555 (2015).

Zakikhani, K., Nasiri, F. & Zayed, T. A review of failure prediction models for oil and gas pipelines. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 11, 03119001 (2020).

Yang, X., Chen, K. & Liu, M. Research on the connectivity reliability analysis and optimization of natural gas pipeline network based on topology. Sci. Rep. 15, 13442 (2025).

Farahani, S., Tahershamsi, A. & Behnam, B. Earthquake and post-earthquake vulnerability assessment of urban gas pipelines network. Nat. Hazards. 101, 327–347 (2020).

Jeon, S. S. & O’Rourke, T. D. Northridge earthquake effects on pipelines and residential buildings. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 95, 294–318 (2005).

Fan, X., Zhang, L., Wang, J., Ren, Y. & Liu, A. Analysis of faulting destruction and water supply pipeline damage from the first mainshock of the February 6, 2023 Türkiye earthquake doublet. Earthq. Sci. 37, 78–90 (2024).

Cubrinovski, M. et al. Wellington’s earthquake resilience: lessons from the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake. Earthq. Spectra. 36, 1448–1484 (2020).

Zhao, J. et al. Research on leakage detection technology of natural gas pipeline based on modified Gaussian plume model and Markov chain Monte Carlo method. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 182, 314–326 (2024).

Jahangiri, V. & Shakib, H. Reliability-based seismic evaluation of buried pipelines subjected to earthquake-induced transient ground motions. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 18, 3603–3627 (2020).

Xu, Z., Che, A. & Zhou, H. Seismic landslide susceptibility assessment using principal component analysis and support vector machine. Sci. Rep. 14, 3734 (2024).

Makhoul, N., Navarro, C., Lee, J. S. & Gueguen, P. A comparative study of buried pipeline fragilities using the seismic damage to the Byblos wastewater network. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 51, 101775 (2020).

Yang, M. et al. Research on the interaction between trench material and pipeline under fault displacement. Sci. Rep. 14, 12439 (2024).

Li, H., Feng, X., Chen, S. & Song, K. Structural behavior of large diameter prestressed concrete cylinder pipelines subjected to strike-slip faults. Sci. Rep. 15, 7560 (2025).

Zhao, K. et al. Dynamic behavior and failure of buried gas pipeline considering the pipe connection form subjected to blasting seismic waves. Thin-Walled Struct. 170, 108495 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Seismic performance analysis of shallow-buried large-scale three-box-section segment-connected pipeline structure under multiple actions. Sci. Rep. 13, 2584 (2023).

Castiglia, M., de Magistris, F. S., Onori, F. & Koseki, J. Response of buried pipelines to repeated shaking in liquefiable soils through model tests. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 143, 106629 (2021).

Darvishi, R., Lashgari, A. & Jafarian, Y. Predictive models for assessment of buried pipeline response under seismic landslides in Iran. Transp. Geotechnics. 45, 101208 (2024).

Du, A., Wang, X., Xie, Y. & Dong, Y. Regional seismic risk and resilience assessment: methodological development, applicability, and future research needs–An earthquake engineering perspective. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 233, 109104 (2023).

Caputo, A. C., Giannini, R. & Paolacci, F. Pressure Vessels and Piping Conference. V008T008A032 (American Society of Mechanical Engineers).

Cheng, Y. & Akkar, S. Probabilistic permanent fault displacement hazard via Monte Carlo simulation and its consideration for the probabilistic risk assessment of buried continuous steel pipelines. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dynamics. 46, 605–620 (2017).

Farahani, S., Behnam, B. & Tahershamsi, A. Probabilistic seismic multi-hazard loss Estimation of Iran gas trunklines. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 66, 104176 (2020).

Kwong, N. S. et al. Earthquake risk of gas pipelines in the conterminous united States and its sources of uncertainty. ASCE-ASME J. Risk Uncertain. Eng. Syst. Part. A: Civil Eng. 8, 04021081 (2022).

Mousavi, M., Hesari, M. & Azarbakht, A. Seismic risk assessment of the 3rd Azerbaijan gas pipeline in Iran. Nat. Hazards. 74, 1327–1348 (2014).

Ojomo, O. et al. Regional earthquake-induced landslide assessments for use in seismic risk analyses of distributed gas infrastructure systems. Eng. Geol. 340, 107664 (2024).

Makrakis, N., Psarropoulos, P. N. & Tsompanakis, Y. Optimal routing of gas pipelines in seismic regions using an efficient Decision-Support tool: A case study in Northern Greece. Appl. Sci. 14, 10970 (2024).

Alavi, S. H., Mashayekhi, M. & Zolfaghari, M. Incorporating seismic risk assessment into the determination of the optimal route for gas pipelines. Sustainable Resilient Infrastructure. 9, 328–348 (2024).

Arya, A. K. A critical review on optimization parameters and techniques for gas pipeline operation profitability. J. Petroleum Explor. Prod. Technol. 12, 3033–3057 (2022).

Sarbu, I. Optimization of urban water distribution networks using deterministic and heuristic techniques: comprehensive review. J. Pipeline Syst. Eng. Pract. 12, 03121001 (2021).

FEMA. Hazus Earthquake Model Technical Manual (Hazus 6.1) (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2024).

Arabi, M. & Gharehhassanloo, S. Application and comparison of analytical hierarchy process (AHP) and network methods in path finding of pipeline water transmission system, from Taleghan’s dam to Hashtgerd new city, Tehran, Iran. Open. Access. Libr. J. 5, 1–16 (2018).

Karur, K., Sharma, N., Dharmatti, C. & Siegel, J. E. A survey of path planning algorithms for mobile robots. Vehicles 3, 448–468 (2021).

Mashayekhi, M., Estekanchi, H. E., Vafai, H. & Ahmadi, G. An evolutionary optimization-based approach for simulation of endurance time load functions. Eng. Optim. 51, 2069–2088 (2019).

Zamani, F. et al. Optimum design of double tuned mass dampers using multiple metaheuristic multi-objective optimization algorithms under seismic excitation. Front. Built Environ. 11, 1559530 (2025).

Halder, R. K. Applying Particle Swarm Optimization: New Solutions and Cases for Optimized Portfolios. 209–232 (Springer, 2021).

Alavi, S., Pilehvaran, A. & Mashayekhi, M. Damage identification in truss structures using a hybrid PSO-HHO algorithm with selective natural frequencies and mode shape. Civil Eng. Appl. Solutions. 1, 55–73 (2025).

Kumar, S. et al. . 7th International Conference on Contemporary Computing and Informatics (IC3I).. 1119–1124 (IEEE, 2024).

Peng, Z., Manier, H. & Manier, M. A. Particle swarm optimization for capacitated location-routing problem. IFAC-PapersOnLine 50, 14668–14673 (2017).

Kennedy, J. & Eberhart, R. Proceedings of ICNN’95-International Conference on Neural Networks.. 1942–1948 (IEEE).

Yang, X. S. Optimization and metaheuristic algorithms in engineering. Metaheuristics Water Geotech. Transp. Eng. 1, 23 (2013).

El-Maissi, A. M., Argyroudis, S. A. & Nazri, F. M. Seismic vulnerability assessment methodologies for roadway assets and networks: A state-of-the-art review. Sustainability 13, 61 (2020).

Bommer, J. J. & Alarcon, J. E. The prediction and use of peak ground velocity. J. Earthquake Eng. 10, 1–31 (2006).

Newmark, N. M. & Hall, W. J. Earthquake spectra and design. In Engineering Monographs on Earthquake Criteria (1982).

Liao, S. S., Veneziano, D. & Whitman, R. V. Regression models for evaluating liquefaction probability. J. Geotech. Eng. 114, 389–411 (1988).

Seed, H. B., Romo, M., Sun, J., Jaime, A. & Lysmer, J. The Mexico earthquake of September 19, 1985—Relationships between soil conditions and earthquake ground motions. Earthq. Spectra. 4, 687–729 (1988).

O’Rourke, T. & Jeon, S. S. Factors affecting the earthquake damage of water distribution systems. In Technical Council on Lifeline Earthquake Engineering. 16, 379–388 (1999).

Honegger, D. & Eguchi, R. Determination of the Relative Vulnerabilities to Seismic Damage for Dan Diego Country Water Authority (SDCWA) Water Transmission Pipelines. (FEMA, 1992).

FEMA. Hazus Inventory Technical Manual (Hazus 6.0) (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2022).

Ghodrati Amiri, G., Razeghi, H., Amrei, R., Aalaee, S., Rasouli, S. & H. & Seismic hazard assessment of Shiraz, Iran. J. Appl. Sci. 8, 38–48 (2008).

Pagani, M. et al. OpenQuake engine: an open hazard (and risk) software for the global earthquake model. Seismol. Res. Lett. 85, 692–702 (2014).

Seismology, I. I. O. E. E. A (Tehran, 2022).

Crowley, H. et al. A brief overview of the past, present and future of the global earthquake model (GEM) foundation. Ann. Geophys. 67, S433–S433 (2024).

Akkar, S. & Bommer, J. J. Empirical equations for the prediction of PGA, PGV, and spectral accelerations in Europe, the Mediterranean region, and the Middle East. Seismol. Res. Lett. 81, 195–206 (2010).

Akkar, S., Sandıkkaya, M. A. & Bommer, J. J. Empirical ground-motion models for point-and extended-source crustal earthquake scenarios in Europe and the Middle East. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 12, 359–387 (2014).

Chiou, B. J. & Youngs, R. R. An NGA model for the average horizontal component of peak ground motion and response spectra. Earthq. Spectra. 24, 173–215 (2008).

Zhao, J. X. et al. Attenuation relations of strong ground motion in Japan using site classification based on predominant period. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 96, 898–913 (2006).

Alavi, S. H., Bahrami, A., Mashayekhi, M. & Zolfaghari, M. Optimizing interpolation methods and point distances for accurate earthquake hazard mapping. Buildings 14, 1823 (2024).

Oliver, M. A. & Webster, R. Kriging: a method of interpolation for geographical information systems. Int. J. Geographical Inform. Syst. 4, 313–332 (1990).

Panah, A. & Farajzadeh, M. Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Seismic Zonation (Nice, October 17–19). 1651–1658 (1995).

Yildirim, V., Yomralioglu, T., Nisanci, R., Erbas, Y. S. & Bediroglu, S. Proceedings of the 6th International Pipeline Technology Conference, Ostend, Belgium. 6–9.

Cheng, Y., Ning, C. L. & Du, W. Spatial cross-correlation models for absolute and relative spectral input energy parameters based on Geostatistical tools. Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 110, 2728–2742 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the writing of the article and to the conceptualization of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alavi, S.H., Mashayekhi, M. & Zolfaghari, M. Optimized seismic risk mitigation in pipeline routing using a metaheuristic GIS based approach. Sci Rep 15, 32916 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17525-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-17525-w