Abstract

Lysosome-dependent cell death (LDCD) is an emerging form of regulated cell death with critical implications in tumor development, immune modulation, and therapy responsiveness. However, the role of LDCD-related genes in colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) remains poorly understood. We comprehensively analyzed LDCD-related gene expression profiles using transcriptomic data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus databases (GEO). Unsupervised clustering was performed to identify molecular subtypes. A prognostic signature was developed using LASSO and Cox regression analyses. Immune infiltration characteristics and immunotherapy responses were assessed via multiple algorithms. Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis was conducted to explore the cellular distribution of LDCD genes. Functional assays, including colony formation, Transwell migration, and western blotting, were performed to validate the role of key LDCD regulators in COAD cell line. LDCD-related genes were differentially expressed in COAD tissues and stratified patients into two distinct subtypes with significant differences in survival, immune infiltration, and biological pathways. A five-gene prognostic signature demonstrated robust predictive ability for overall survival and was associated with tumor immune microenvironment characteristics. High-risk patients showed distinct immune checkpoint profiles and predicted sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. scRNA-seq analysis revealed cell type-specific expression patterns of LDCD genes. In vitro experiments confirmed that modulation of a key LDCD regulator, SLC11A1, affected the proliferation and invasiveness of COAD cells. Moreover, the impact of SLC11A1 on apoptosis and intracellular ROS level confirmed the potential association between SLC11A1 and COAD cell apoptosis. Our study reveals the prognostic value and immunological relevance of LDCD-related genes in COAD. These findings provide new insights into molecular classification and may aid in the development of personalized therapeutic strategies targeting LDCD pathways in colorectal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) is the most common histological subtype of colorectal cancer (CRC), ranking among the leading causes of cancer-related morbidity and mortality worldwide1. Despite advances in diagnostic techniques and the development of multidisciplinary treatment strategies, the overall prognosis of COAD remains suboptimal, especially in advanced stages2. A key challenge in the clinical management of COAD lies in its significant inter-patient heterogeneity, which contributes to variable treatment responses and disease progression3. Traditional staging systems, such as the TNM classification, provide only limited prognostic information and fail to capture the molecular complexity of the disease4. Therefore, there is an urgent need to establish molecular risk stratification models that can improve prognostic accuracy, guide personalized treatment strategies, and ultimately enhance patient outcomes.

Functional remodeling of lysosomes has been shown to facilitate tumor cell growth and contribute to therapeutic resistance by supporting oncogenic signaling pathways5. In contrast to normal cells, cancer cells exhibit a greater dependency on lysosomal function to meet their accelerated biosynthetic and energy demands, rendering them especially sensitive to disruptions in lysosomal homeostasis6. Lysosome-dependent cell death (LDCD) has emerged as a distinct mode of regulated cell death (RCD) that plays a critical role in cancer biology. This process is primarily initiated by lysosomal membrane permeabilization (LMP), which results in the cytosolic release of cathepsins and other lysosomal enzymes capable of triggering apoptotic or necrotic cascades7. Cancer cells often exhibit enhanced lysosomal biogenesis and altered lysosomal positioning, which not only supports their metabolic demands but also sensitizes them to LMP-induced cytotoxicity8,9. LDCD has been implicated in disrupting tumor cell survival by impairing autophagic flux, inducing oxidative stress, and compromising membrane integrity10. Moreover, pharmacological agents that destabilize lysosomal membranes or inhibit lysosomal acidification have demonstrated tumor-selective lethality, offering a novel avenue for therapeutic intervention11,12 Importantly, LDCD can also circumvent classical apoptosis resistance pathways, making it a promising target in treatment-refractory cancers13,14. Further exploration of LDCD-related mechanisms may therefore contribute to the development of more effective and selective anticancer strategies.

Recent evidence suggests that the lysosome functions as a central hub for cellular catabolism and immune regulation and plays a crucial role in shaping the tumor microenvironment (TME) of COAD15. In addition to its canonical function in autophagy-mediated degradation, the lysosome regulates key processes such as antigen presentation, cytokine release, and immune receptor turnover16,17,18. Within the immunosuppressive TME of COAD, lysosome-associated pathways are often hijacked by tumor cells to degrade immune-stimulatory molecules and evade cytotoxic immune responses15,19. Dysregulation of lysosomal function in tumor-infiltrating immune cells, such as dendritic cells and macrophages, can impair antigen processing and disrupt the activation of effector T cells20,21. Moreover, aberrant autophagy lysosome activity contributes to immune evasion and poor responsiveness to immunotherapy in COAD22. These findings underscore the lysosome’s multifaceted role as a mediator of TME shaping in CRC and point to lysosomal signaling as a potential target for enhancing anti-tumor immunity23.

Despite growing recognition of LDCD as a pivotal mechanism in cancer regulation, its comprehensive role in COAD remains largely unexplored. Our study systematically investigates the expression patterns, prognostic implications, and immune landscape associations of LDCD-related genes in COAD. Through integrated multi-omics analysis, unsupervised clustering, prognostic model construction, immunological profiling, single-cell RNA sequencing, and in vitro functional validation, we aim to elucidate the biological significance of LDCD in COAD progression and therapeutic responsiveness. Our findings may provide novel insights into molecular subtyping and offer potential biomarkers for guiding individualized treatment strategies in COAD.

Materials and methods

Data collection and preprocessing

The transcriptomic expression matrices and corresponding clinical baseline information for normal tissues and COAD samples used in this study were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://www.cancer.gov/). Firstly, transcriptomic data for both normal and tumor tissues were downloaded from the TCGA-COAD project using the R programming environment and preprocessed the raw data using Perl scripts. Gene labels in the TCGA dataset were annotated and standardized based on the Ensembl database. Subsequently, two COAD-related datasets, GSE17538 and GSE39582, were retrieved from the GEO database. Both datasets were generated using the same platform (GPL570, [HG-U133_Plus_2] Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0 Array). The gene labels in these datasets were annotated and converted into gene symbols using platform-specific annotation files in Perl programming environment. To eliminate batch effects across different datasets, we employed the “sva” R package to perform batch effect correction and normalization on the expression matrices from the different datasets. Of note, the samples lack clinical survival information or with an overall survival time of less than 30 days were excluded from further analysis. Ultimately, a total of 41 normal samples and 417 COAD samples were extracted from the TCGA dataset; 556 COAD samples were extracted from GSE39582; and 200 COAD samples were obtained from GSE17538 for subsequent analyses. In addition, tumor mutation burden (TMB) and copy number variation (CNV) frequency data for COAD samples were downloaded from the UCSC Xena database (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/) for integrated analysis.

Identification of lysosome-dependent cell death related differentially expressed genes and molecular subtype characterization

Based on previously published literature, a total of 215 genes associated with LDCD were identified for subsequent analysis24 (Supplementary Table 1). Differential expression analysis was performed using the “limma” R package, with thresholds set at fold change ≥ 2 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 to screen for LDCD-related differentially expressed genes (LDCD-DEGs) in COAD samples. The “ggplot2” R package was utilized to visualize the CNV frequencies of LDCD-DEGs. The “maftools” R package was used to generate a waterfall plot of the mutation landscape, depicting the somatic mutation characteristics of LDCD-DEGs in COAD samples. Additionally, based on reference genome coordinates, the “RCircos” R package was employed to construct a circular plot illustrating the chromosomal locations of the LDCD-DEGs. To further explore the expression patterns of LDCD-DEGs, an unsupervised consensus clustering analysis was performed using the “ConsensusClusterPlus” R package based on their expression profiles. The “k-means” algorithm was applied with the number of clusters (k) ranging from 2 to 9. Cluster stability was assessed by generating consensus matrix heatmaps and cumulative distribution function (CDF) curves, and the optimal number of clusters was determined to identify potential molecular subtypes. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted using the “ggplot2” R package to visualize the expression differences among the identified subtypes. Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival analysis was performed using the “survival” R package based on the “log-rank” test to evaluate differences in clinical outcomes among the molecular subtypes.

Regulation of KEGG signaling pathways and immune microenvironment landscape

Based on the KEGG pathway gene set “c2.cp.kegg.v7.2.symbols,” gene set variation analysis (GSVA) was performed using the “GSVA” R package to evaluate the differences in enrichment scores of KEGG pathways among the identified molecular subtypes25,26,27. To assess the immune infiltration status of different molecular subtypes, the “estimate” R package was applied based on transcriptomic expression profiles. Immune score, Stromal score, ESTIMATE score, and Tumor purity were calculated to characterize the tumor microenvironment components. In addition, single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) was conducted using the “GSVA” R package to quantify the infiltration levels of 23 immune cell types based on the marker genes. The results were visualized using the “ggplot2” R package to illustrate the immune landscape differences across molecular subtypes.

Identification of differentially expressed genes associated with LDCD molecular subtypes and characterization of gene-based subtype

Differential expression analysis between LDCD-related molecular subtypes was performed using the “limma” R package. With the criteria of fold change ≥ 1.5 and adjusted p-value < 0.05, we identified the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between different molecular subtypes. The shared and unique DEGs among different groups were visualized using the “VennDiagram” R package. To further explore the potential biological functions of these DEGs, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were conducted using the “clusterProfiler” R package, aiming to elucidate the underlying molecular regulatory mechanisms. Based on the expression profiles of DEGs, unsupervised consensus clustering analysis was performed using the “k-means” algorithm implemented in the “ConsensusClusterPlus” R package to identify potential gene-based subtypes. A heatmap was generated using the “pheatmap” R package to visualize the expression patterns of DEGs across different clinicopathological features and molecular subtypes, providing further insight into their biological significance and inter-subtype differences.

Construction of the LDCD scoring model based on integrated machine learning algorithms

To construct a prognostic scoring model based on LDCD, we merged the TCGA-COAD dataset with the GSE39582 dataset as a training cohort and designated the GSE17538 dataset as an independent external validation cohort. The DEGs expression matrices were extracted from both the training and validation cohorts using the “limma” R package, and survival time along with clinical outcomes were integrated for subsequent prognostic modeling. Under the framework of leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV), we applied 101 combinations of 10 machine learning algorithms—including randomForestSRC, glmnet, plsRcox, superpc, gbm, mixOmics, survcomp, CoxBoost, survivalsvm, and BART—to compute the concordance index (C-index) for both the training and validation sets. The model with the highest average C-index was selected as the optimal machine learning model. Subsequently, multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed on the prognostic variables identified by the optimal machine learning model using the “survival” R package to determine independent prognostic indicators and corresponding risk coefficients. Based on prognostic variables and risk coefficients, the LDCD scoring model was constructed. The LDCD score for each sample was calculated using the formula: LDCD score = Σ (expression level of variable × risk coefficient). Samples in both the training and validation cohorts were stratified into high- and low-LDCD score groups according to the median LDCD score. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were generated using the “survival” R package, and survival differences between groups were assessed using the “log-rank” test. Furthermore, time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated using the “timeROC” R package, and the area under the curve (AUC) at 1, 3, and 5 years was calculated to evaluate the predictive performance of the LDCD scoring model. Lastly, the “ggalluvial” R package was employed to construct Sankey diagrams, providing an intuitive visualization of the relationship between LDCD score subgroups and patient prognostic outcomes.

Independent prognostic analysis and nomogram construction

The “limma” R package was used to analyze the distribution differences of the LDCD score across various clinicopathological subgroups. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed using the “survival” R package to calculate the hazard ratios (HR) and p-values for the LDCD score and clinicopathological variables. Based on the results of the multivariate analysis, a nomogram was constructed using the “rms” R package by integrating the LDCD score with clinicopathological features to predict 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year overall survival probabilities in patients. To assess the calibration of the nomogram, calibration plots were generated using the “regplot” R package, comparing the predicted survival probabilities with the actual observed outcomes.

Prediction of immunotherapy response, tumor mutation burden landscape, and drug sensitivity analysis

Based on the transcriptomic expression matrix of the samples, we employed the Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) database (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) to quantify the TIDE scores of each sample, thereby evaluating their potential immune evasion capability and predicting response to immune checkpoint blockade. Additionally, we accessed The Cancer Immunome Atlas (TCIA) database to systematically analyze the immunogenomic features of different molecular subgroups and to calculate the Immunophenoscore (IPS), which predicts the potential response to CTLA-4 and PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor therapies. For drug sensitivity prediction, we utilized the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC) database and applied the “pRRophetic” R package to estimate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values of various small-molecule drugs across different subgroups. Regarding tumor mutation burden (TMB), raw TMB data were preprocessed using Perl scripts to calculate TMB scores for each sample. Subsequently, differential analysis of TMB scores between molecular subgroups was conducted using the “limma” R package. Mutation profiles of key genes within each subgroup were visualized using waterfall plots generated by the “maftools” R package.

Preprocessing and analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data

The single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) dataset GSE231559 was obtained from the GEO database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). A total of seven samples, including three from normal colon tissues and four from COAD tumor tissues, were extracted for downstream analysis. Data preprocessing and systematic analysis were performed in R (version 4.4.1) using the Seurat package (version 4.3.0). Initially, the gene expression matrix of each sample was loaded and converted into individual Seurat objects. Quality control (QC) filtering was then applied with the following criteria: cells with a number of detected genes (nFeature_RNA) between 200 and 6000 and a mitochondrial gene percentage (percent.mt) less than 15% were retained. Low-quality cells, doublets, and dying cells were removed to ensure data reliability and accuracy. Each sample was normalized using the “NormalizeData” function with the “LogNormalize” method. The top 2000 highly variable genes in each sample were identified using the “FindVariableFeatures” function for downstream analysis. To eliminate batch effects and integrate multiple samples, the “FindIntegrationAnchors” and “IntegrateData” functions were used. The integrated expression matrix was then scaled and centered using the “ScaleData” function. PCA was performed for linear dimensionality reduction, and the top 20 principal components (PCs) were selected for subsequent clustering and visualization. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) and t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) analyses were conducted using the “RunUMAP” and “RunTSNE” functions, respectively. Cell clustering was performed using the “FindNeighbors” and “FindClusters” functions with a resolution set to 1.2, enabling the identification of biologically meaningful cell subpopulations. Clustering results were visualized with distinct colors representing different cell types, highlighting the cellular composition differences between normal and tumor tissues. Cell type annotation was initially performed using the “SingleR” package, referencing known marker genes from the CellMarker database. Manual correction was then applied to improve annotation accuracy. Specific DEGs in each cell cluster were identified using the “FindAllMarkers” function, with thresholds set at log2 fold change > 0.25 and adjusted p-value < 0.05. To investigate the expression patterns of the LDCD gene set across different cell populations, module scores were calculated using the “AddModuleScore” function. Violin plots were generated to visualize the distribution of LDCD scores among various cell subsets, allowing for the evaluation of LDCD gene set expression characteristics at the single-cell level.

Cell culture

The human normal colon epithelial cell line NCM460 was purchased from INCELL Corporation (San Antonio, TX, USA), and the human colon cancer cell line SW480 was obtained from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). NCM460 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco, USA). SW480 cells were maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Gibco, USA) containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. All cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The culture medium was replaced every 2–3 days, and cells were passaged using 0.25% trypsin–EDTA solution (Gibco, USA) when they reached 70%–80% confluence. Prior to experiments, cell morphology was examined under an inverted microscope to ensure that the cells were in good condition, in logarithmic growth phase, and free from contamination, thereby ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of subsequent experimental results.

Western blot analysis

NCM460 and SW480 cells at logarithmic growth phase were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), then lysed with RIPA buffer (Beyotime, China) containing 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Beyotime, China). The lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The supernatants were collected, and total protein concentrations were determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Equal amounts of protein (30 μg) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk dissolved in TBST buffer at room temperature for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C with primary antibodies: rabbit anti-SLC11A1 (1:1000, Abcam, ab85370), rabbit anti-Bcl-XL (1:1000, Abcam, ab32370), rabbit anti-Cleaved Caspase-3 (1:1000, Abcam, ab2302), rabbit anti-Bax (1:1000, Abcam, ab32503), rabbit anti-GAPDH (1:5000, Abcam, ab9485). After washing three times with TBST (10 min each), membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:5000, Cell Signaling Technology, #7074) at room temperature for 1 h. Following further washing steps, protein bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (Millipore, USA) and imaged with the ChemiDoc imaging system (Bio-Rad, USA). GAPDH was used as an internal loading control for normalization. Band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software.

Construction of siRNA interference model

To establish an SW480 cell model with low SLC11A1 expression, small interfering RNA (siRNA) technology was employed to specifically silence the expression of SLC11A1. SW480 cells were seeded into 6-well plates and transfected when the cell density reached 50–60%. The siRNA sequences targeting SLC11A1 (si-SLC11A1) and negative control siRNA (si-NC) were synthesized by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine™ 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, siRNA (50 nM), P3000 reagent, and Lipofectamine 3000 were diluted separately in Opti-MEM medium, incubated at room temperature for 5 min, then mixed and incubated for an additional 15 min to form transfection complexes. The complexes were then gently added dropwise to the wells. Cells were further cultured for 24–48 h post-transfection in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and without antibiotics (medium was replaced once during the incubation). The transfection efficiency was verified by assessing the protein expression level of SLC11A1 via Western blot analysis.

Colony formation assay

SW480 cells transfected with either si-SLC11A1 or si-NC were trypsinized and counted. Approximately 500 cells per well were seeded into 6-well plates, with three replicates per group. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 for 10–14 days, with fresh DMEM complete medium containing 10% FBS replaced every 3 days until visible colonies (≥ 50 cells per colony) formed. At the end of the culture period, the medium was gently discarded, and the cells were washed once with PBS. Colonies were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed with PBS, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min. Excess stain was removed by rinsing, and the plates were air-dried. Colonies were visualized and photographed under a microscope, and the number of colonies was quantified using ImageJ software. This assay was used to evaluate the impact of SLC11A1 silencing on the clonogenic ability of SW480 cells, thereby reflecting its potential role in cell proliferation.

Transwell assay

A 24-well Transwell system (8 μm pore size; Corning, USA) without Matrigel coating was used to assess cell migration. After 48 h of transfection, SW480 cells were resuspended in serum-free DMEM and counted. A total of 200 μL of cell suspension (approximately 5 × 104 cells) was added to the upper chamber, while 600 μL of DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber as a chemoattractant. The cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. After incubation, the Transwell inserts were carefully removed, and non-migrated cells on the upper surface were wiped off with a cotton swab. The inserts were then washed twice with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, washed again with PBS, and stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min. After rinsing and air-drying, the membranes were cut and mounted onto microscope slides. Five random fields per membrane were photographed at 200 × magnification, and the number of migrated cells was counted using ImageJ software. This assay aimed to assess the effect of SLC11A1 knockdown on the migratory ability of SW480 cells, highlighting its potential function in CRC cell metastasis.

CCK-8 cell assay

Following transfection with si-SLC11A1 or si-NC, SW480 cells were digested, counted, and adjusted to a concentration of 1 × 104 cells/mL. A total of 100 μL of cell suspension was seeded into 96-well plates, with six replicates per group. After allowing cells to adhere for 4 h, 10 μL of CCK-8 reagent was added at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. The plates were incubated for 1.5 h at 37 °C, and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (BioTek, USA). The experiment was repeated three times, and the average values were calculated. Changes in OD values between the si-SLC11A1 and control groups at different time points were compared to evaluate the impact of SLC11A1 knockdown on SW480 cell proliferation dynamics.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Intracellular ROS levels were quantified using a commercial ELISA kit (MEIKE, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, cell supernatants were prepared by centrifugation (Neofuge 15R, Heal Force) to remove particulate matter. Samples and standards (100 µL/well) were loaded onto pre-coated 96-well plates alongside blank and control wells. After 1–2 h incubation at 37 °C and plate washing (RT3100 autowasher, Rayto), biotinylated detection antibody (100 µL/well) was added followed by 1 h incubation at 37 °C. After repeated washes, enzyme conjugate (100 µL/well) was added and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in darkness. TMB substrate (100 µL/well) was then added for color development (10–30 min, 37 °C in darkness), with the reaction terminated by 2 M sulfuric acid (100 µL/well). Optical density was measured at 450 nm within 10 min using a microplate reader (BioTeK Epoch, USA). Sample concentrations were calculated from standard curves generated with serially diluted standards. All samples were processed in triplicate, avoiding hemolyzed or hyperlipidemic specimens, with precise pipetting (Dragon pipettes) and strict adherence to incubation times.

Statistical analysis

All experimental data were preprocessed and analyzed using R software (version 4.4.1), Perl, and GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, USA). Data results are presented as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD). Two-group comparisons were performed using Wilcoxon rank sum test and Student’s t-test, while comparisons among multiple groups were conducted using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by multiple comparison tests. Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences were evaluated with the log-rank test. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical significance is indicated as follows: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Results

Identification of differentially expressed LDCD signatures and mutation landscape in COAD

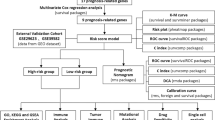

The overall analytical workflow of this study is illustrated in a flowchart (Fig. 1). In this study, a total of 215 LDCD-related signatures were included to elucidate their potential regulatory roles in COAD. By applying the differential expression threshold of |fold change|≥ 2 and adjusted p < 0.05, we identified eight LDCD-DEGs between normal and COAD tissues (Fig. 2A). Among them, PLA2G3, ATP6V0A4, and SLC11A1 were significantly upregulated in COAD samples, whereas CHGA, CTSG, MRGPRX2, CLU, and BLK were significantly upregulated in normal tissues (Fig. 2B,C). To further investigate the potential roles of LDCD-DEGs in COAD, we analyzed the CNV frequencies and mutational landscape. CNV analysis revealed notable amplification in ATP6V0A4 and PLA2G3, whereas CLU, BLK, and CHGA showed prominent deletion frequencies in COAD (Fig. 2D). The mutational landscape analysis showed that 13.44% of COAD samples harbored mutations in LDCD-related genes. The mutation frequencies for ATP6V0A4, SLC11A1, BLK, CLU, PLA2G3, and MRGPRX2 were 4%, 3%, 3%, 2%, and 2%, respectively (Fig. 2E). In addition, chromosomal colocalization analysis revealed the distinct chromosomal distribution patterns of these eight LDCD-DEGs genes (Fig. 2F). Collectively, these findings indicate differential expression of LDCD-related genes in COAD and highlight the associations of LDCD-DEGs with somatic mutation burden and CNV alterations.

Identification of differentially expressed LDCD signatures and landscape analysis of mutation burden. (A–C) Differential expression analysis of LDCD signatures between normal and tumor groups with thresholds of |fold change|≥ 2 and adjusted p-value < 0.05. (D) Copy number variation frequency analysis of LDCD-DEGs. (E) Mutation burden frequency analysis of LDCD-DEGs signatures. (F) Colocalization analysis of LDCD-DEGs signatures across different chromosomes.

Identification of LDCD molecular subtypes and evaluation regulatory mechanisms

To further elucidate the molecular regulatory mechanisms of LDCD in COAD, we integrated the TCGA and GSE39582 datasets, extracting a total of 973 samples for LDCD molecular subtyping. Based on the optimal classification determined by an unsupervised consensus clustering algorithm, three distinct LDCD molecular subtypes (k = 3) were identified: Subtype A (n = 273), Subtype B (n = 230), and Subtype C (n = 470) (Fig. 3A). PCA plot demonstrated distinct expression patterns among the three subtypes, highlighting the heterogeneity of LDCD molecular subtypes (Fig. 3B). Survival analysis revealed significant differences in overall survival among the three LDCD subtypes, with Subtype B showing the worst prognosis (Fig. 3C, p = 0.003). Moreover, GSVA indicated that multiple metabolism-related pathways were significantly downregulated in Subtype B compared to Subtype A, including butanoate metabolism, citrate cycle (TCA cycle), nitrogen metabolism, ascorbate and aldarate metabolism, and retinol metabolism. In contrast, Subtype C exhibited significant downregulation of immune-related signaling pathways, such as ECM-receptor interaction, chemokine signaling pathway, leukocyte transendothelial migration, and cell adhesion molecules (Fig. 3D,E). These findings suggest that distinct LDCD molecular subtypes in COAD are characterized by specific metabolic and immune signatures, potentially contributing to the heterogeneity of clinical outcomes.

Identification of LDCD molecular subtype characteristics and differential analysis of KEGG signaling pathways. (A) Identification of LDCD molecular subgroups based on unsupervised consensus clustering analysis. (B) PCA plot illustrating the distribution of three LDCD molecular subgroups. (C) Clinical prognosis evaluation of LDCD molecular subgroups using the log-rank test. (D,E) GSVA analysis revealing differential KEGG signaling pathways among LDCD molecular subgroups.

Immune microenvironment landscape and immunotherapy response assessment of LDCD molecular subtypes

The tumor immune microenvironment plays a pivotal regulatory role in the initiation and progression of COAD, and the degree of immune cell infiltration may influence immune evasion and therapeutic efficacy. In the subsequent analysis, we employed multiple immune infiltration estimation algorithms to explore the immune landscape of the LDCD molecular subtypes. Results from ssGSEA revealed significant differences in the infiltration levels of most immune cell types among the LDCD subtypes, including eosinophils, gamma delta T cells, immature B cells, immature dendritic cells, and MDSCs (Fig. 4A). ESTIMATE analysis showed that Subtype B, which was associated with worse prognosis, exhibited markedly higher stromal score, immune score, and ESTIMATE score, but lower tumor purity compared to Subtypes A and C, indicating a more extensive immune infiltration status in Subtype B (Figs. 4B–E). Furthermore, we assessed the potential response of different LDCD subtypes to immunotherapy. The TIDE score was significantly lower in Subtype C, suggesting a better potential response to immune checkpoint blockade therapies (Fig. 4F). Additionally, the IPS analysis indicated that patients in Subtypes A and C—despite poorer prognoses—had higher IPS values than those in Subtype B, implying greater clinical benefit from CTLA-4 and PD-1 targeted therapies (Fig. 4G–I). Collectively, these results reveal distinct patterns of immune microenvironment infiltration and immunotherapy response among LDCD molecular subtypes, offering novel insights into personalized therapeutic strategies for COAD patients based on LDCD subtype classification.

Immune microenvironment infiltration landscape and immunotherapy response prediction of LDCD molecular subgroups. (A) Quantification of the infiltration proportions of 23 immune cell types in different molecular subgroups based on the ssGSEA algorithm. (B–E) Evaluation of immune infiltration characteristics using the ESTIMATE algorithm. (F) TIDE score analysis of LDCD molecular subgroups. (G–I) IPS score analysis revealing the immunotherapy response of CTLA-4/PD-1 across LDCD molecular subgroups.

Comprehensive analysis of gene subtype characteristics associated with LDCD molecular subtypes

Based on differential analysis algorithm, we identified 39 DEGs associated with LDCD molecular subtypes (Fig. 5A, Supplementary Table 2–4). KEGG enrichment analysis indicated that these DEGs were primarily enriched in immune-related signaling pathways, including the Chemokine signaling pathway, Viral protein interaction with cytokine and cytokine receptor, and Cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction (Fig. 5B). GO analysis revealed that these genes were associated with biological functions such as humoral immune response, muscle system process, cytokine activity, and chemokine activity (Fig. 5C). Based on the DEGs associated with LDCD molecular subtypes, unsupervised consensus clustering analysis was performed, identifying three distinct gene subtypes: Subtype A (n = 278), Subtype B (n = 330), and Subtype C (n = 365) (Fig. 5D). PCA plot further demonstrated clear separation among the three gene subtypes, supporting their molecular heterogeneity (Fig. 5E). Survival analysis revealed significant differences in clinical outcomes among the gene subtypes, with Subtype C exhibiting the most favorable prognosis compared to Subtypes A and B (Fig. 5F). A heatmap was generated to visualize the expression patterns of the 39 DEGs across different clinicopathological features and LDCD molecular subtypes in COAD (Fig. 5G). Moreover, differential expression analysis showed that several key LDCD signature genes—including PLA2G3, CHGA, CTSG, SLC11A1, CLU, and BLK—displayed significant expression differences among the gene subtypes (Fig. 5H).

Identification of gene subtype characteristics associated with LDCD molecular subgroups. (A) Differential expression analysis of genes among LDCD molecular subgroups with thresholds of |fold change|≥ 2 and adjusted p-value < 0.05. (B,C) GO and KEGG enrichment analyses of DEGs among LDCD molecular subgroups. (D) Identification of gene subtypes based on unsupervised consensus clustering analysis of DEGs. (E) Unsupervised PCA plot of gene subgroups. (F) Clinical prognosis curve analysis of gene subtypes. (G) Expression profiles of DEGs across different clinicopathological features and molecular subgroups. (H) Differential expression analysis of the LDCD signature within gene subgroups.

Development and stability validation of the LDCD scoring system based on machine learning algorithm

Based on the DEGs associated with LDCD molecular subtypes and survival status, we developed an LDCD scoring system to evaluate clinical prognosis and accurately stratify risk in COAD patients. Using the GSE17538 dataset as the validation cohort, we implemented 101 algorithmic combinations derived from 10 machine learning models under a LOOCV framework. Among them, the StepCox[backward] + CoxBoost model achieved the highest concordance index (C-index), indicating optimal performance (Fig. 6A). In both the training and validation cohorts, we stratified patients into high- and low-score LDCD subgroups based on the median value of the LDCD score (Fig. 6B,C). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis revealed that patients in the low LDCD score subgroup exhibited significantly better clinical outcomes compared to those in the high-score subgroup in both cohorts (Fig. 6D,F). Time-dependent ROC analysis showed that in the training set, the AUC for 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival was 0.717, 0.658, and 0.652, respectively; in the validation set, the AUC values were 0.722, 0.701, and 0.693, respectively (Fig. 6E,G). Differential analysis further demonstrated that the LDCD score was significantly higher in molecular subtypes associated with poor prognosis, suggesting that an elevated LDCD score might be linked to unfavorable outcomes in COAD (Fig. 6H,I). Moreover, a Sankey diagram illustrated the close associations among LDCD molecular subtypes, gene subtypes, LDCD score, and clinical prognosis (Fig. 6J). Collectively, these findings confirm that the LDCD scoring system is a robust tool for prognostic evaluation and risk stratification in COAD, while also highlighting its potential links with different molecular subtypes.

Construction of the LDCD scoring index system based on multiple machine learning algorithms and stability validation. (A) Calculation of C-index for the training set and independent external validation sets using 101 algorithm combinations from 10 machine learning methods. (B,C) Stratification of LDCD scoring index subgroups in the training and external validation cohorts. (D–G) Clinical prognosis survival curve analysis and time-dependent ROC curves of LDCD scoring subgroups in training and validation cohorts. (H,I) Differential analysis of LDCD scores across LDCD molecular and gene subgroups. (J) Sankey diagram illustrating the relationships among different molecular subgroups, LDCD scoring subgroups, and clinical survival outcomes.

Independence assessment of LDCD score and construction of nomogram model

We further explored the expression levels of the LDCD score across different clinicopathological subgroups to assess potential associations. Differential analysis revealed that the LDCD score varied significantly among subgroups stratified by age, clinical stage, N stage, and T stage, with higher scores observed in patients with more advanced disease stages (Fig. 7A–E). To evaluate the independent prognostic value of the LDCD score, univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed in both training and validation cohorts. In the training set, age, stage, T stage, and the LDCD score were significantly associated with poor prognosis (Fig. 7F,G). Similarly, in the validation cohort, stage, grade, and the LDCD score were identified as independent adverse prognostic factors (Fig. 7H,I). Subsequently, we constructed nomogram models integrating clinical variables and the LDCD score to predict 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival probabilities in COAD patients across both cohorts (Fig. 7J,L). Calibration curves indicated a high degree of consistency between the predicted survival probabilities from the nomogram and the actual observed outcomes in both datasets (Fig. 7K,M).

Evaluation of independent prognostic value and construction of the nomogram model. (A–E) Differential analysis of LDCD scoring index across various clinicopathological features. (F,G) Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of LDCD scoring index and clinicopathological variables in the training cohort. (H,I) Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of LDCD scoring index and clinicopathological variables in the validation cohort. (J,K) Construction of the nomogram model based on clinicopathological variables and LDCD scoring index along with calibration curve analysis in the training cohort. (L,M) Construction of the nomogram model and calibration curve analysis in the validation cohort.

Immune infiltration landscape and drug sensitivity analysis of LDCD score subgroups

To explore the potential association between the LDCD score and immune microenvironmental characteristics in COAD, we employed both the ESTIMATE and ssGSEA algorithms. The ESTIMATE analysis revealed that the immune score, stromal score, and ESTIMATE score were significantly elevated in the high LDCD score subgroup, while tumor purity was markedly reduced, suggesting a higher degree of immune infiltration in this subgroup (Fig. 8A–D). Results from ssGSEA further indicated a heterogeneous immune cell infiltration pattern: the high LDCD score subgroup exhibited decreased infiltration of Activated B cells, Activated CD8+ T cells, Monocytes, Neutrophils, and Type 17 T helper cells, while the infiltration of Gamma delta T cells, Immature dendritic cells, Regulatory T cells, and Type 2 T helper cells was significantly increased (Fig. 8E). In addition, drug sensitivity analysis demonstrated that the IC50 values for 8 anticancer drugs, including Vinorelbine, Thapsigargin, Imatinib, Linifanib, Paclitaxel, Pazopanib, Saracatinib, and Sunitinib, were significantly lower in the high LDCD score subgroup. This implies that patients in this group may derive greater clinical benefit from these therapeutic drugs (Fig. 8F). Collectively, these findings reveal the distinct immune infiltration landscape of the LDCD score subgroups and highlight potentially effective anti-cancer drugs, offering novel insights for risk-based clinical management in COAD.

Immune microenvironment infiltration landscape and drug sensitivity analysis of LDCD scoring index subgroups. (A–D) Immune infiltration characteristic analysis based on the ESTIMATE algorithm. (E) Quantification of infiltration proportions of 23 immune cell types using the ssGSEA algorithm. (F) Drug sensitivity analysis of LDCD scoring subgroups.

Tumor mutation burden landscape and immunotherapy response assessment

TMB is closely associated with response to immunotherapy. In this study, we further investigated the somatic mutation profiles and immunotherapy responsiveness of different LDCD score subgroups. TMB analysis revealed that the high LDCD score subgroup exhibited significantly elevated TMB scores compared to the low-score group (Fig. 9A). In contrast, IPS analysis suggested that the low LDCD score subgroup had significantly higher IPS values, indicating a greater likelihood of favorable clinical responses to CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade therapies (Fig. 9B–D). Moreover, somatic mutation profiling showed that 98.97% of patients in the high LDCD score subgroup harbored somatic mutations. Notably, APC (73%), TTN (51%), PIK3CA (34%), and SYNE1 (34%) exhibited significantly higher mutation frequencies in the high-score subgroup compared to the low-score group (Fig. 9E,F).

Single-cell sequencing analysis revealed the distribution characteristics of the LDCD prognostic signature

We further evaluated the distribution patterns of cellular subpopulations and the expression of the LDCD prognostic signature at the single-cell sequencing level in COAD. Based on the GSE231559 dataset, scRNA-seq data from three normal samples and four COAD samples were extracted for subsequent analysis. After quality control of scRNA-seq data from the seven samples, the top 2,000 highly variable genes were identified for dimensionality reduction analysis (Fig. 10A,B). According to known marker genes for each cell type, 22 distinct cell types were identified, and their distribution was visualized using UMAP and t-SNE plots (Fig. 10C,D). Violin plot analysis demonstrated the expression levels of the LDCD prognostic signature across the 22 cell types, indicating significant expression of genes such as SLC11A1, PLA2G2A, and CLCA1 in these populations (Fig. 10E). Using the SingleR annotation algorithm, 10 cell subpopulations were accurately identified from the 22 cell types, including epithelial cells, fibroblasts, monocytes, NK cells, tissue stem cells, B cells, macrophages, neutrophils, T cells, and endothelial cells. The distribution characteristics of these 10 subpopulations were further illustrated by UMAP and t-SNE plots (Fig. 10F,G). Quantitative analysis of the LDCD signature expression across the 10 cell subpopulations revealed a notably higher score in epithelial cells (Fig. 10H). Additionally, violin plots revealed distinct expression patterns of key LDCD genes within these subpopulations: SFRP2 was significantly expressed in fibroblasts; SLC11A1 was prominent in macrophages and monocytes; FXYD6 was markedly expressed in epithelial cells and fibroblasts; MFAP5 showed significant expression in fibroblasts and tissue stem cells; and SLC11A1 was also substantially expressed in epithelial cells, tissue stem cells, and fibroblasts (Fig. 10I).

Single-cell sequencing analysis revealing the composition of COAD cell subpopulations and expression characteristics of the LDCD prognostic signature. (A) Violin plots showing quality control preprocessing of scRNA-seq data from seven samples. (B) Identification of highly variable genes. (C,D) UMAP and tSNE plots illustrating the distribution of 22 cell types. (E) Violin plots displaying the expression levels of the LDCD prognostic signature across 22 cell types. (F,G) UMAP and tSNE plots depicting the distribution of 10 cell subpopulations. (H) Scoring of the LDCD signature in 10 cell subpopulations. (I) Expression levels of the LDCD prognostic signature within the 10 cell subpopulations.

Knockdown of SLC11A1 significantly inhibits proliferation and migration of COAD cells

Among the LDCD prognostic variables, SLC11A1 exhibited the highest risk coefficient, suggesting its potential role as a key target influencing COAD development. To further validate the role of SLC11A1 in COAD, we conducted in vitro experiments. Western blot (WB) analysis demonstrated that the protein expression level of SLC11A1 was significantly elevated in the COAD cell line SW480 compared to the control group (Fig. 11A,B). Using siRNA-mediated interference, we established an siSLC11A1 knockdown model in SW480 cells to assess the functional effects of SLC11A1 suppression. WB results confirmed that SLC11A1 protein levels were markedly reduced in the siSLC11A1 group, verifying effective knockdown (Fig. 11C,D). Colony formation assays showed that silencing SLC11A1 significantly inhibited the proliferative capacity of COAD cells compared to the siNC control (Fig. 11E,F). Furthermore, Transwell assays revealed that SLC11A1 knockdown significantly suppressed the invasive ability of COAD cells (Fig. 11G,H). CCK-8 assays conducted at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h indicated that cell viability was notably reduced in the siSLC11A1 group relative to controls (Fig. 11I). After intervention with siSLC11A1, WB results showed the apoptosis-related protein Cleaved-Caspase3 and Bax were significantly upregulated, the anti-apoptosis-related protein Bcl-xl was significantly downregulated (Fig. 11J,K) and the level of ROS increased significantly as well after SLC11A1 suppression (Fig. 11L), which indicates that intervention in siSLC11A1 can promote cell apoptosis. Collectively, these results highlight the potential role of SLC11A1 in COAD progression, where its inhibition effectively suppresses cell proliferation and migration, providing novel targets and perspectives for future mechanistic studies.

Knockdown of SLC11A1 expression significantly inhibits proliferation and migration of COAD. (A) Protein expression of SLC11A1 detected in NCM460 and SW480 cell lines (n = 3). (B) Quantitative analysis of SLC11A1 protein levels (n = 3). (C,D) Validation of interference efficiency in the siSLC11A1 knockdown model. (E,F) Colony formation assays showing changes in cell proliferation before and after SLC11A1 knockdown (n = 3). (G,H) Transwell assays before and after SLC11A1 interference (n = 3), bar = 50 μm. (I) CCK8 assays (n = 3). (J,K) Protein expression of apoptosis-related proteins before and after SLC11A1 knockdown (n = 3). (L) Quantification of ROS levels before and after SLC11A1 knockdown in SW480 cells (n = 3). Data are presented as mean ± SD, and statistical significance is indicated as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Discussion

As a recently discovered form of cell death, current understanding of LDCD remains limited. However, emerging evidence suggests that LDCD is associated with antitumor activity. For instance, LDCD induced by STAT3 inhibitors has been shown to exert potent antitumor effects28. Considering the critical role of the STAT3 pathway in colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), LDCD may possess potential antitumor properties in COAD29,30,31. In addition, LDCD is known to crosstalk with autophagy and may jointly participate in the death of tumor cells32,33,34. This relationship is further supported by changes in LMP observed during autophagy18,35,36,37. Autophagy has been confirmed to regulate proliferation and cell death during COAD progression38. Our findings confirm the prognostic value of the LDCD-related risk model in COAD, further suggesting the involvement of LDCD in tumor progression.

In the immune infiltration analysis, five T helper cell subtypes showed significant differences between LDCD-defined risk groups. Generally, type 1 T helper cells (Th1) play a critical role in enhancing antitumor activity of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, while type 2 T helper cells (Th2) mainly promote the activity of immunosuppressive cells and contribute to tumor immune evasion39,40. Our results showed that both Th1 and Th2 levels were significantly elevated in high-risk COAD patients compared to the low-risk group. Although most studies have indicated an antitumor role of Th1 in CRC41,42, the elevated Th1 observed in high-risk patients may be associated with functional exhaustion or immune exclusion. Indeed, some evidence suggests that Th1 levels in CRC patients may negatively correlate with immune responses, highlighting the complexity of Th1 function in CRC43. Moreover, some studies have focused on the Th1/Th2 balance and its impact on the efficacy of immunotherapy44, which may help explain the differences in immunotherapy responsiveness between risk groups observed in our study.

Type 17 T helper (Th17) cells mainly secrete IL-17A, IL-21, and IL-22 and are capable of promoting inflammation and recruiting immune cells45. In CRC, Th17 cells have been reported to exert both tumor-promoting and antitumor effects46,47. Cytokines such as IL-17A and IL-22 produced by Th17 cells can have antitumor activity48. In our study, the poorer prognosis COAD subgroup exhibited lower Th17 infiltration levels. Regulatory T cells (Tregs), which promote tumor progression through immunosuppression, were more abundant in the poor prognosis group, which is consistent with previous findings49. Follicular helper T cells (Tfh), which typically cooperate with B cells in antigen presentation and immune activation, are potential biomarkers of immunotherapy responsiveness50. However, dysregulated Tfh cells have also been associated with immune dysfunction and even tumorigenesis51. The prognostic role of Tfh varies across tumor types52. Most CRC-related studies have reported a positive correlation between Tfh infiltration and favorable immune responses or prognosis, and Tfh cells may also be involved in gut microbiota–mediated immune modulation in CRC53,54,55. It should be noted that since our risk model was not constructed based on Tfh-related features, the observed elevation of Tfh in high-risk patients may represent a non-determinant variable caused by immune dysregulation or systemic compensatory activation.

By coordinating the uptake and efflux of nutrients across cell membranes, solute carrier (SLC) family proteins are essential for meeting the metabolic demands of cancer cells, supporting their survival, proliferation, and adaptation to the tumor microenvironment (TME)56. Among the prognostic variables in COAD, SLC11A1 had the highest risk coefficient. Subsequent in vitro experiments confirmed that SLC11A1 influences the proliferation and migration of COAD cells. Solute carrier family 11member 1 protein (SLC11A1) is located in phagolysosomes and functions as a divalent metal ion transporter in macrophages57. Due to its role in lysosomal targeting, SLC11A1 is essential for proper lysosomal function and may contribute to the development or progression of several diseases, including cancer58,59. Previous reports suggest that SLC11A1 may predict overall survival in CRC patients and serve as a potential biomarker for immunotherapy efficacy60,61. There is also evidence implicating SLC11A1 in photodynamic therapy responsiveness and immune microenvironment modulation in CRC62. However, these findings have lacked in vitro validation in CRC. For the first time, our study provides experimental evidence that SLC11A1 affects the proliferation and migration of COAD cells, suggesting its potential as a therapeutic target. Given the possible correlation between SLC11A1 and LDCD in COAD, future studies involving SLC11A1 knockdown followed by comprehensive functional assays will be of great significance to validate its role in modulating immune cell biological functions.

The rapid development of immunotherapy has transformed the current landscape of cancer treatment, including COAD, and has achieved long-lasting remission in some patients63. However, due to the relatively low infiltration of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes (TILs) in the TME of CRC, some patients exhibit poor responses to immunotherapy64. In our study, we effectively predicted the immunotherapy responsiveness of COAD patients through the construction of a risk model. Currently, there is no direct evidence indicating a relationship between LDCD and drug resistance. One possible explanation is that lysosomes are closely involved in maintaining intracellular iron homeostasis7,65. Alterations in LMP can modulate the signaling strength of ferroptosis66,67. Considering the crosstalk among ferroptosis, immunogenic cell death, and TME reprogramming, this may explain the differences in immunotherapy responsiveness observed in the LDCD risk model68,69.

This study has several limitations. First, although the prognostic model was validated in independent cohorts, prospective clinical validation in larger, multicenter cohorts is still warranted. Second, our in vitro experiments focused on limited genes and cell lines, which may not fully represent the complex tumor ecosystem in vivo. Future studies incorporating organoid models and animal experiments will be necessary to expand upon our findings. In addition, although SLC11A1 is reported as a LDCD related gene, it should be noted that direct experimental validation of the impact of SLC11A1 knockdown on LDCD induction remains an important area for future investigation. To address this, functional assays assessing lysosomal enzyme activity, lysosomal membrane permeability, and cell death morphology upon SLC11A1 modulation are currently underway as a primary focus of our subsequent research. Moreover, concerning our single-cell sequencing analysis result that SLC11A1 was prominent in macrophages and monocytes, the impact of SLC11A1 on monocytes or macrophages migration and whether monocytes or macrophages affect cell survival in an SLC11A1-dependent manner would be an interesting topic.

In conclusion, our multi-omics analysis establishes LDCD as a critical determinant of molecular heterogeneity, immune microenvironment dynamics, and clinical outcomes in COAD. By defining LDCD-based molecular subtypes and constructing a robust prognostic model, this study provides novel insights into the prognostic stratification and therapeutic implications of LDCD, paving the way for future mechanistic investigations into key regulators such as SLC11A1.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Thrumurthy, S. G. et al. Colorectal adenocarcinoma: risks, prevention and diagnosis. BMJ 354, i3590 (2016).

Johnson, D. et al. Current advances in targeted therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer—Clinical translation and future directions. Cancer Treat. Rev. 125, 102700 (2024).

Li, Q. et al. Signaling pathways involved in colorectal cancer: pathogenesis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 9(1), 266 (2024).

Quirke, P. et al. The future of the TNM staging system in colorectal cancer: time for a debate?. Lancet Oncol. 8(7), 651–657 (2007).

Davidson, S. M. & Vander Heiden, M. G. Critical functions of the lysosome in cancer biology. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 57, 481–507 (2017).

Pu, J. et al. Mechanisms and functions of lysosome positioning. J. Cell Sci. 129(23), 4329–4339 (2016).

Tang, D. et al. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Res. 29(5), 347–364 (2019).

Kallunki, T., Olsen, O. D. & Jaattela, M. Cancer-associated lysosomal changes: friends or foes?. Oncogene 32(16), 1995–2004 (2013).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144(5), 646–674 (2011).

Piao, S. & Amaravadi, R. K. Targeting the lysosome in cancer. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1371(1), 45–54 (2016).

Peng, F. et al. Regulated cell death (RCD) in cancer: key pathways and targeted therapies. Signal Transduct. Target Ther. 7(1), 286 (2022).

Appelqvist, H. et al. The lysosome: from waste bag to potential therapeutic target. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 5(4), 214–226 (2013).

Takeda, A. et al. Macrolide antibiotics enhance the antitumor effect of lansoprazole resulting in lysosomal membrane permeabilization-associated cell death. Int. J. Oncol. 57(6), 1280–1292 (2020).

Circu, M. et al. Modulating lysosomal function through lysosome membrane permeabilization or autophagy suppression restores sensitivity to cisplatin in refractory non-small-cell lung cancer cells. PLoS ONE 12(9), e0184922 (2017).

Liu, D. et al. Reinvigoration of cytotoxic T lymphocytes in microsatellite instability-high colon adenocarcinoma through lysosomal degradation of PD-L1. Nat. Commun. 15(1), 6922 (2024).

Herhaus, L. et al. IRGQ-mediated autophagy in MHC class I quality control promotes tumor immune evasion. Cell 187(25), 7285-7302 e29 (2024).

Gou, Q. et al. PPARgamma inhibited tumor immune escape by inducing PD-L1 autophagic degradation. Cancer Sci. 114(7), 2871–2881 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Autophagy in tumor immune escape and immunotherapy. Mol. Cancer 24(1), 85 (2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Modulation of lactate-lysosome axis in dendritic cells by clotrimazole potentiates antitumor immunity. J. Immunother. Cancer. 9(5) (2021).

Yan, R. et al. Carnosine regulation of intracellular pH homeostasis promotes lysosome-dependent tumor immunoevasion. Nat. Immunol. 25(3), 483–495 (2024).

Khazen, R. et al. Melanoma cell lysosome secretory burst neutralizes the CTL-mediated cytotoxicity at the lytic synapse. Nat. Commun. 7, 10823 (2016).

Zhitomirsky, B. & Assaraf, Y. G. Lysosomes as mediators of drug resistance in cancer. Drug Resist. Updat. 24, 23–33 (2016).

Xing, Y. et al. Lysosome targeted nanoparticle aggregation reverses immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment for cancer immunotherapy. Adv. Mater. 36(47), e2412730 (2024).

Zou, Y. et al. Leveraging diverse cell-death patterns to predict the prognosis and drug sensitivity of triple-negative breast cancer patients after surgery. Int. J. Surg. 107, 106936 (2022).

Kanehisa, M. et al. KEGG: biological systems database as a model of the real world. Nucleic Acids Res. 53(D1), D672–D677 (2025).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28(11), 1947–1951 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28(1), 27–30 (2000).

Xu, M. X. et al., A novel synthesised STAT3 inhibitor exerts potent anti-tumour activity by inducing lysosome-dependent cell death. Br. J. Pharmacol. (2025).

Chang, Y. C. et al. Secretory RAB GTPase 3C modulates IL6-STAT3 pathway to promote colon cancer metastasis and is associated with poor prognosis. Mol. Cancer 16(1), 135 (2017).

Liu, X. et al. BMI1 and MEL18 promote colitis-associated cancer in mice via REG3B and STAT3. Gastroenterology 153(6), 1607–1620 (2017).

Wang, Z. et al. Panaxadiol inhibits programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression and tumour proliferation via hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and STAT3 in human colon cancer cells. Pharmacol. Res. 155, 104727 (2020).

Domagala, A. et al. Typical and atypical inducers of lysosomal cell death: a promising anticancer strategy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19(8) (2018).

Nakamura, H. et al. Lysosome-associated membrane protein 3 induces lysosome-dependent cell death by impairing autophagic caspase 8 degradation in the salivary glands of individuals with Sjogren’s disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 75(9), 1586–1598 (2023).

Yang, L. X. et al. Silver-coated zero-valent iron nanoparticles enhance cancer therapy in mice through lysosome-dependent dual programed cell death pathways: triggering simultaneous apoptosis and autophagy only in cancerous cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 8(18), 4122–4131 (2020).

Hsu, K. F. et al. Cathepsin L mediates resveratrol-induced autophagy and apoptotic cell death in cervical cancer cells. Autophagy 5(4), 451–460 (2009).

Meyer, N. et al. Autophagy activation, lipotoxicity and lysosomal membrane permeabilization synergize to promote pimozide- and loperamide-induced glioma cell death. Autophagy 17(11), 3424–3443 (2021).

Fucho, R. et al. ASMase regulates autophagy and lysosomal membrane permeabilization and its inhibition prevents early stage non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 61(5), 1126–1134 (2014).

Devenport, S. N. & Shah, Y. M. Functions and implications of autophagy in colon cancer. Cells. 8(11) (2019).

Gabitass, R. F. et al. Elevated myeloid-derived suppressor cells in pancreatic, esophageal and gastric cancer are an independent prognostic factor and are associated with significant elevation of the Th2 cytokine interleukin-13. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 60(10), 1419–1430 (2011).

LaCasse, C. J. et al. Th-1 lymphocytes induce dendritic cell tumor killing activity by an IFN-gamma-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 187(12), 6310–6317 (2011).

Thoma, O. M. et al. p21 prevents the exhaustion of CD4(+) T cells within the antitumor immune response against colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 166(2), 284–297 e11 (2024).

Paladhi, A. et al. Targeting thymidine phosphorylase alleviates resistance to dendritic cell immunotherapy in colorectal cancer and promotes antitumor immunity. Front. Immunol. 13, 988071 (2022).

Loyon, R. et al. Peripheral innate lymphoid cells are increased in first line metastatic colorectal carcinoma patients: A negative correlation with Th1 immune responses. Front. Immunol. 10, 2121 (2019).

Shang, Q. et al. Polysaccharides regulate Th1/Th2 balance: A new strategy for tumor immunotherapy. Biomed. Pharmacother. 170, 115976 (2024).

Knochelmann, H. M. et al. When worlds collide: Th17 and Treg cells in cancer and autoimmunity. Cell Mol. Immunol. 15(5), 458–469 (2018).

Greten, T. F. et al. Human Th17 cells in patients with cancer: Friends or foe?. Oncoimmunology 1(8), 1438–1439 (2012).

Wilke, C. M. et al. Th17 cells in cancer: help or hindrance?. Carcinogenesis 32(5), 643–649 (2011).

Grabowski, E. F., Naus, G. J. & Weksler, B. B. Prostacyclin production in vitro by rabbit aortic endothelium: correction for unstirred diffusional layers. Blood 66(5), 1047–1052 (1985).

Imianowski, C. J. et al. Regulatory T cells in the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Cancer. (2025).

Tangye, S. G. et al. The good, the bad and the ugly—TFH cells in human health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13(6), 412–426 (2013).

Crotty, S. T follicular helper cell biology: A decade of discovery and diseases. Immunity 50(5), 1132–1148 (2019).

Gutierrez-Melo, N. & Baumjohann, D. T follicular helper cells in cancer. Trends Cancer 9(4), 309–325 (2023).

Cremonesi, E. et al. Gut microbiota modulate T cell trafficking into human colorectal cancer. Gut 67(11), 1984–1994 (2018).

Overacre-Delgoffe, A. E. et al. Microbiota-specific T follicular helper cells drive tertiary lymphoid structures and anti-tumor immunity against colorectal cancer. Immunity. 54(12), 2812–2824 e4 (2021).

Bindea, G. et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity 39(4), 782–795 (2013).

Hushmandi, K. et al. Amino acid transporters within the solute carrier superfamily: Underappreciated proteins and novel opportunities for cancer therapy. Mol. Metab. 84, 101952 (2024).

Atkinson, P. G., J. M. Blackwell, & Barton, C. H. Nramp1 locus encodes a 65 kDa interferon-gamma-inducible protein in murine macrophages. Biochem. J. 325(Pt 3), 779–786 (1997).

Lam-Yuk-Tseung, S., Picard, V. & Gros, P. Identification of a tyrosine-based motif (YGSI) in the amino terminus of Nramp1 (Slc11a1) that is important for lysosomal targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 281(42), 31677–31688 (2006).

Awomoyi, A. A. The human solute carrier family 11 member 1 protein (SLC11A1): linking infections, autoimmunity and cancer?. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 49(3), 324–329 (2007).

Ma, Y. et al. SLC11A1 associated with tumor microenvironment is a potential biomarker of prognosis and immunotherapy efficacy for colorectal cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 13, 984555 (2022).

Hsu, H. C. et al. SLC11A1 predicts the overall survival of patients with colorectal cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 14(6), 2839–2851 (2024).

Xu, J. et al. PDT-regulated immune gene prognostic model reveals tumor microenvironment in colorectal cancer liver metastases. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 13129 (2025).

Ganesh, K. et al. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: rationale, challenges and potential. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16(6), 361–375 (2019).

Al Zein, M. et al. Immunotherapy and immunoevasion of colorectal cancer. Drug Discov. Today 28(9), 103669 (2023).

Chen, Z. et al. Improving ferroptosis-mediated immunotherapy for colorectal cancer through lysosome-targeted photodynamic therapy. Mater. Today Bio. 31, 101552 (2025).

Li, W. et al. Molecular engineering of pH-responsive NIR oxazine assemblies for evoking tumor ferroptosis via triggering lysosomal dysfunction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145(6), 3736–3747 (2023).

Rizzollo, F. et al. The lysosome as a master regulator of iron metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 46(12), 960–975 (2021).

Xie, L. et al. Phototheranostic metal-phenolic networks with antiexosomal PD-L1 enhanced ferroptosis for synergistic immunotherapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144(2), 787–797 (2022).

Liang, H. et al. Renal clearable ultrasmall single-crystal Fe nanoparticles for highly selective and effective ferroptosis therapy and immunotherapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143(38), 15812–15823 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.X. and X.W. conceived and designed the study. Z.L. performed most of the analyses and wrote the manuscript. L.C., B.L., and B.W. performed some of the analyses. All authors participated in the acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, and approval of the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Cai, L., Liao, B. et al. Comprehensive characterization of lysosome-dependent cell death reveals prognostic significance and immune landscape in colon adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep 15, 33132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18267-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18267-5