Abstract

Obesity is a growing public health challenge with complex causes involving both environmental and genetic factors. This study explored the contribution of genetic variants in the UCP3 gene (implicated in energy metabolism) to obesity risk in a Pakistani population. Using a case-control design, 400 participants from Karachi (200 cases—individuals with obesity; 200 controls—individuals with normal body mass index or BMI) were assessed for sociodemographic, obesity-related physical signs, comorbidities, anthropometric, metabolic, and lifestyle factors, alongside next-generation sequencing of the UCP3 gene. Individuals with obesity (cases) were more frequently married, had a family history of obesity, and exhibited obesity-related physical signs compared to controls. All anthropometric (except height) and metabolic (except HDL-C) variables were significantly aberrant in cases. Similarly, behavioral patterns such as random eating, a tendency toward fat-dense food, low physical activity, and irregular sleep-wake cycles were more prevalent among cases. Genetic analysis revealed 43 variants after quality filtering, with most located in regulatory regions rather than altering protein structure. Three variants, including rs35517703, rs142107918, and rs928421426, were observed exclusively in the individuals with obesity (cases). Additionally, three novel variants [73712770 (GA > GAA), 73718482 (CTTT > CTT), and 73718482 (CTTT > CTTTT)] were identified that may reflect population-specific genetic diversity. By focusing on UCP3 variants with population relevance, this research provides new insights into the genetic architecture of obesity in Pakistanis or South Asians in general. It supports the value of regional genetics and genomics studies in global health contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Excessive fat accumulation alters body metabolism, influences fat distribution, and compromises health1. By 2030, an estimated 2.16 billion people will be overweight and 1.12 billion obese2. Obesity is a multifactorial condition influenced by environmental, behavioral, and genetic factors, with genetic makeup determining susceptibility by affecting metabolism, appetite, and physical activity3. Family and twin studies indicate body mass index (BMI) heritability ranges from 40 to 70%, underlining the major genetic influence4,5.

Despite decades of research, the genetic basis of obesity remains incompletely understood. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCPs) have been a focus due to their role in energy metabolism6,7. An imbalance between energy intake and fat utilization drives the obese phenotype8. Energy in fat cells is either used for ATP synthesis or dissipated as heat through thermoregulation9. UCPs, originally identified for thermogenesis10 uncouple oxidative phosphorylation from ATP generation11,12. The Human Obesity Gene Map Update identifies uncoupling protein 3 (UCP3) as a candidate gene linked to hereditary obesity susceptibility13,14. UCP3, encoded on chromosome 11q13.4 with seven exons and six introns15 is mainly expressed in brown adipose tissue and skeletal muscle10,16,17 particularly in glycolytic type 2 fibers. Its role includes facilitating fatty acid anion export from the mitochondrial matrix, protecting against lipid-induced damage18,19. UCP3 expression in skeletal muscle increases with high-fat diet, acute exercise, and fasting20,21,22,23 but decreases after endurance training, weight loss, and in oxidative type 1 fibers24,25. Reduced activity of UCP3 is linked to lower energy expenditure and increased fat storage26 while higher expression may enhance metabolic rate and lower BMI27.

Not all genetic variants increase obesity risk; some may be protective. Variants in the UCP3 promoter can modulate expression in ways that predispose to higher BMI or maintain healthy weight. Some studies show no significant association between UCP3 variants and obesity, while others suggest a link28,29 demonstrating inconsistent results.

The relationship between UCP3 variation and obesity in Pakistanis remains unknown. Using sequencing data from 400 individuals in Karachi, this study aimed to identify and annotate novel and known UCP3 variants and to explore characteristics of individuals with obesity carrying variants observed only among cases and absent in controls.

Results

Sociodemographic factors, obesity onset, and associated clinical manifestations

The ages of participants ranged from 12 to 63 years old. The study sample, consisting of a sample size of 400, encompassed 183 females and 217 males. Among the total study population (n = 400), most of the study participants fell in the category of young adults with a median (interquartile range) age of 27 (13.75). Among cases (individuals with obesity), 64 individuals (32%) had obesity since childhood. However, 55 participants reported gaining weight in their twenties, 31 participants had obesity in their thirties, while only 9 participants were observed to have obesity in their forties. In addition, 20.5% of individuals with obesity (n = 41) reported that they have had obesity since adolescence (Supplementary Table 1). Table 1 presents a comparison of categorical parameters (sociodemographic factors and obesity-related physical signs, comorbidities, and stigma) between cases and controls. A statistically significant difference in sociodemographic factors (marital status and family history of obesity) was observed between cases and controls. A greater proportion of individuals with obesity were married compared to the control group (p = corrected0.003). Among participants with obesity (cases), 45% of males (47 out of 105) and 53% of females (50 out of 95) were married; the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.226). The population with obesity exhibits a greater proportion of individuals with a family history of obesity compared to the control group (p corrected= 0.009). However, no substantial difference was noted regarding parental consanguinity between cases and controls (p > 0.05). The comparison of obesity-related physical signs in Table 1, which includes abdominal striae, axillary striae, acanthosis nigricans, and hyperlipidemia signs, revealed that these manifestations were substantially more prevalent in cases than in controls (p corrected< 0.001). Similarly, a greater percentage of cases exhibited obesity-related comorbidities such as joint issues and depression compared to controls (p corrected< 0.001). Moreover, female participants with irregular menstrual cycles were substantially more prevalent in cases than in controls (pcorrected = 0.009). Furthermore, 46.5% of cases experienced stigma for having obesity. However, after comparing the obesity-related stigma between male and female cases, significantly higher percentage (65.3%) of females were found to be stigmatized for having obesity ( p corrected< 0.001) as compared to males (29.5%). All associations remained statistically significant even after applying corrections for multiple testing.

Ethnic diversity

The study sample consisted of participants of diverse ethnic backgrounds (Fig. 1A). The highest number of study participants was Urdu-speaking, with 56.8% participants. On the contrary, Balochis were observed as the smallest number of study participants (2.3%). In addition, Sindhis, Punjabis, and Pakhtuns were 7.0%, 17.8%, and 11.0%, respectively. Moreover, 5.1% participants belonged to various other ethnicities of Pakistan, such as Baltistan, Chitrali, Gilgit, Hazara, Kargili, and Kashmiri. Similarly, when compared between cases and normal-BMI controls, almost similar ethnic distribution was observed in both study groups. The order of ethnic representation in cases (Fig. 1B) and controls (Fig. 1C) from highest to lowest representation was—Urdu-speaking (cases = 57.5%, controls = 56.0%), Punjabi (cases = 17%, controls = 18.5%), Pakhtuns (cases = 12.0%, controls = 10.0%), Sindhi (cases = 6.0%, controls = 8.0%), others (cases = 4.0%, controls = 6.5%), Balochi (cases = 3.5%, controls = 1.0%).

Ethnic representation. Panel A shows the distribution of ethnic groups in the overall study sample, Panel B shows the distribution among cases (individuals with obesity), and Panel C among normal-BMI controls. Each rectangle represents a specific ethnic group, and the size of each area corresponds to its proportion (%) in the respective group. All values are shown in percentage. Color intensity reflects relative proportions, with darker blue indicating higher representation.

Significantly aberrant anthropometric and metabolic variables in cases

Comparison of anthropometric and metabolic variables between cases (individuals with obesity) and controls (individuals with normal BMI) is presented in Table 2. Almost all study variables including anthropometric measurements (weight, BMI, waist circumference, hip circumference, waist-to-height ratio, waist-to-hip ratio, biceps skinfold thickness, triceps skinfold thickness, abdomen skinfold thickness, supra-iliac skinfold thickness, thigh skinfold thickness, subscapular skinfold thickness and body fat percentage) and metabolic parameters (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, fasting insulin levels, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, total cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, coronary risk index, atherogenic index, triglycerides-to-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, visceral adiposity index, lipid accumulation product, and product of triglyceride and glucose) were found significantly aberrant in cases as compared to their corresponding normal-BMI controls (p < 0.05). All associations remained statistically significant even after applying corrections for multiple testing. However, height and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HCL-C) did not differ between cases and controls.

Disparities in lifestyle and behavioral factors among cases and controls

The comparison of lifestyle and behavioral characteristics between cases and controls (Table 3) revealed significant differences. A notably higher proportion of individuals with obesity (cases) followed a random eating pattern compared to controls (pcorrected = 0.015). Additionally, cases showed a significantly greater tendency to consume fat-dense foods (pcorrected = 0.002). Physical activity levels were considerably lower among cases than controls (p < 0.001). The individuals deviating from the standard sleep period (8:00 PM to 12:00 midnight) and/or wake-up time (5:00 AM to 7:30 AM) are classified as having an irregular sleep-wake cycle. This pattern was significantly more prevalent in cases (individuals with obesity) than in controls (p corrected= 0.003). Furthermore, shift work was more common among cases (p corrected= 0.013). All associations remained statistically significant even after applying corrections for multiple testing. However, no significant differences were observed between the two groups regarding diet consciousness and insufficient sleep (< 7 h) (p > 0.05).

Genetic variants of UCP3 identified through next-generation sequencing in the study population

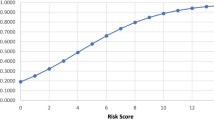

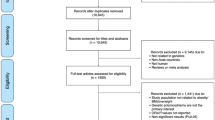

Supplementary Table 2 presents a comprehensive list of genetic variants identified in the UCP3 gene through next-generation sequencing (NGS) in the study population. After removing off-target variants beyond positions 73711111 to 73720334, 130 genetic variants were identified in the UCP3 gene. The different genetic variants were specified with chromosomal position, reference allele, and alternate allele. After exclusion of monomorphic variants (genetic positions where all individuals in the study population have the same allele, showing no variation), singleton variants (appearing only once, considering as technical artifacts) and variants detected only in normal-BMI controls (non-disease-associated variants) as a part of quality control for data reliability, a total of 43 genetic variants were selected, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions, and deletions, with some being biallelic (two alleles) and others multiallelic (more than one alternate allele). Comparison of alternate allele frequencies observed in this study with those reported in the global and South Asian populations from Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) revealed that some variants had relatively high frequencies. However, other variants such as some insertions and deletions, listed in Table 4, were extremely rare or entirely absent in these reference datasets. The functional significance of the variants was assessed using ClinVar, where some were labelled benign, while many were not reported, indicating unknown clinical impact.

Annotation of selected variants in the UCP3 gene

Figure 2 provides an overview of the forty-three genetic variants in the UCP3 gene. Among them, 3 (7%) were novel, while 40 (93%) were previously reported in databases. The distribution of variant types indicates that the majority (84%) were intronic, followed by 3′ untranslated region (UTR) variants (9%), coding variants (5%), and 5′ UTR variants (2%). All the identified coding sequence variants were observed to be synonymous. This suggests that mostly identified variants are likely to impact gene regulation rather than directly altering protein structure, which may influence gene expression or splicing rather than causing direct functional disruptions in the protein itself. Table 5 presents the annotation of 43 selected UCP3 gene variants to provide insights into their potential functional impact. The variants are classified based on their genomic location, including intron variants, 3′ and 5′ UTR variants, and synonymous variants. Additionally, most of the variants are previously known with existing rsIDs; however, a few variants, such as CTTT > CTTTT/CTT at position 73718482 and GA > GAA at position 73712770, were classified as “novel,” suggesting they were not previously reported in major databases.

Distribution of different types of variants identified in the UCP3 gene. The pie chart on the left illustrates the classification of 43 variants based on their genomic locations, with the majority being intronic (84%), followed by 3′ UTR (9%), coding sequences (5%), and 5′ UTR variants (2%). The table summarizes variant counts, including the number of novel variants (n = 3, 7.0%) identified in the study.

Putative functional implications of UCP3 variants

Among 43 UCP3 variants, Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) PHRED-scaled scores were available for 37 of the identified variants, while six variants had no pre-computed scores in the database. The majority of variants (n = 36, approximately 84%) had scores < 10, suggesting low predicted deleteriousness and most likely benign or tolerated. Only a single variant (rs3741135) at a chromosomal position 73713960 with G > A transition showed a score > 10 (10.26), falling within the top 10% of potentially deleterious variants. Moreover, SpliceAI annotation revealed that the delta scores for acceptor loss and donor loss were 0.00 for all variants, indicating no predicted loss of canonical acceptor or donor splice sites. In case of delta score for acceptor gain, two variants scored 0.01 and one scored 0.02, while for delta score for donor gain, two variants scored 0.02 and one scored 0.14. All observed values were below the 0.20 threshold for predicted splice impact, indicating no strong evidence for splicing alterations among the identified variants (Supplementary Table 3). In addition, RegulomeDB annotation was available for all variants (43). Of these, 11 variants had scores between 1a–2b, indicating strong evidence of regulatory potential, including overlap with known transcription factor binding sites and DNase hypersensitive regions. The remaining variants had scores ≥ 3, suggesting less likely to affect binding with minimal or no supporting regulatory evidence (Supplementary Table 4).

Characteristics of cases carrying case-exclusive variants

Among the 43 variants identified in this study (Table 4), three (rs35517703, rs142107918, and rs928421426) were detected that showed presence of alternate allele (either in heterozygous or homozygous from) exclusively in cases (individuals with obesity) but not in any of the control samples. These case-exclusive variants were not previously listed in the ClinVar database. Table 6 presents the key characteristics of the individuals carrying these variants. The variant rs35517703 (CT > C), located within intron 6 of the UCP3 gene at chromosomal position 73712720, was found in four cases. Among them, 75% reported the onset of obesity in their twenties, while one case developed obesity in thirties. The group had an average BMI of 33.7 ± 1.7 kg/m2, and half of the individuals reported a family history of obesity. All carriers of this variant exhibited the heterozygous genotype. The variant rs142107918 (G > C), located in 4th intron of UCP3 gene at position 73716530, was identified in one Punjabi male case who was homozygous (CC) for the alternate allele. This individual had obesity onset in his thirties, a BMI of 36.5 kg/m2, and had a family history of obesity. The third variant, rs928421426, situated in intron 1 of UCP3 at position 73718482, was observed in two female cases. One reported obesity beginning in childhood, while the other reported onset in her twenties. The average BMI among these two individuals was 37.9 ± 4.5 kg/m2, and one had a family history of obesity.

Discussion

We assessed sociodemographic, clinical, anthropometric, metabolic, and behavioral parameters in individuals with obesity compared to normal-BMI controls and, for the first time in a Pakistani population, performed next-generation sequencing of UCP3 gene variants. The findings provide insights into environmental and genetic contributors to obesity, with both consistent and divergent perspectives from prior literature.

The early onset of obesity observed in this study aligns with global evidence that childhood obesity predicts adult obesity30. Married individuals were more likely to have obesity, consistent with reports from Polish, Iranian, and Chinese populations31,32,33 possibly due to post-marriage lifestyle changes, reduced physical activity, and richer meals33,34. A strong family history of obesity supports its heritability, as shown in twin and family studies4. Clinical manifestations and comorbidities such as acanthosis nigricans, hyperlipidemia signs, striae, joint problems, depression, and menstrual irregularities in women were significantly more prevalent among individuals with obesity, consistent with prior research linking obesity to multisystemic health burdens and reproductive dysfunctions35,36,37,38,39.

Anthropometric parameters—including weight, BMI, waist and hip circumference, waist-to-height and waist-to-hip ratios, skinfold thickness, and body fat percentage (%BF)—were consistently elevated among participants with obesity, reflecting generalized and central obesity40. Metabolic abnormalities, including elevated fasting blood glucose (FBG), insulin, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), triglycerides (TGs), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), very low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (VLDL-C), and lipid ratios (with no difference in HDL-C), indicate insulin resistance and dyslipidemia, consistent with prior South Asian and global findings41,42. An elevated TG-to-HDL-C ratio, visceral adiposity index (VAI), and lipid accumulation product (LAP) further support their predictive value for metabolic risk43,44,45,46. Lifestyle factors linked to obesity included random eating patterns, high intake of fat-dense foods, low physical activity, irregular sleep-wake cycles, and higher prevalence of shift work. These findings are consistent with global evidence connecting modern lifestyle patterns to obesity risk. In our sample, irregular meal timing and greater fat-dense food consumption paralleled observations from U.S. and international cohorts47,48. Reduced physical activity was also associated with obesity, consistent with Spanish49. Irregular sleep-wake cycles and shift work, known to disrupt circadian rhythms50,51 were significantly more common among cases. In Pakistan, economic pressures often necessitate shift-based employment that may partly explain this association. Cultural factors may influence the absence of significant differences in diet consciousness between cases and controls as these findings contrasts from the previous study conducted in Dutch population, where conscious dietary restraint is often more prevalent among overweight individuals52. The weight-related stigma was observed significantly more in female cases than male cases, aligning with prior findings of greater societal pressure on women’s physical appearance53.

In this study, 130 genetic variants were initially identified in the UCP3 gene region (chr11:73711111–73720334), reflecting substantial genetic diversity in the Pakistani population. After stringent quality control to remove off-target, monomorphic, and singleton variants, 43 remained, including SNPs, insertions, and deletions in intronic, 3′ UTR, 5′ UTR, and coding regions. Most were intronic, consistent with broader genomic research showing that functional variation in complex diseases like obesity often arises from non-coding regulatory variants rather than protein-altering mutations54. Such variants may affect transcription, splicing, or mRNA stability rather than directly altering UCP3 structure. Given UCP3’s role in mitochondrial energy metabolism, even subtle regulatory changes could influence energy balance55. Comparison with global datasets (gnomAD, Variant Effect Predictor) revealed several variants that were rare or absent globally. For example, rs35517703 (CT > C deletion) at position 73712720 is extremely rare globally but common (37%) in our population, while a novel GA > GAA insertion at 73712770 occurred at a high frequency (~ 66%) among Pakistanis but was absent in gnomAD. These findings highlight population-specific genetic architectures of obesity risk, supporting previous observations that South Asian populations have distinct risk profiles56,57.

Three novel variants were identified: GA > GAA insertion at 73712770 in the 6th intron, and CTTT > CTT deletion and CTTT > CTTTT insertion at 73718482 in the 1st intron. These were absent in Single Nucleotide Polymorphism database (dbSNP), gnomAD, and ClinVar, suggesting population-specific mutations. Given UCP3’s roles in thermogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, and lipotoxicity protection18,19,24,25 even minor regulatory changes could be phenotypically relevant. Higher alternate allele frequency in our cohort compared to their absence globally may reflect population-specific diversity or shared ancestral background.

Using multiple in silico annotation tools, we assessed the potential functional relevance of the identified variants. Most had low CADD PHRED scores (< 10), indicating limited predicted deleteriousness, except rs3741135 (score = 10.26), which merits further consideration. This pattern is consistent with reports that common, especially non-coding, variants tend to have lower CADD scores than rare ones58,59. SpliceAI predictions suggested no substantial splicing effects, with all acceptor and donor gain scores below the 0.20 threshold and a maximum donor gain of 0.14, indicative of weak prediction. While rare exceptions exist, functional validation would be needed to confirm any splicing impact60. RegulomeDB analysis highlighted some variants with ranks ≤ 2b, supported by transcription factor binding and DNase evidence, suggesting possible regulatory roles. Notably, this observation aligns with a previous comprehensive computational analysis of obesity-associated intronic variants, many of which also had RegulomeDB ranks ≤ 261. Such variants, despite low CADD scores, may still influence gene regulation.

Three intronic variants—rs35517703, rs142107918, and rs928421426—were observed exclusively in cases. Their presence in regulatory regions supports a possible effect on UCP3 expression through alternative splicing62,63. Although no functional annotations exist in ClinVar or dbSNP, their occurrence only in obesity cases, coupled with early obesity onset and elevated BMI in carriers, suggests a contributory role in obesity pathogenesis. Larger studies are needed to confirm these findings, assess their association with obesity, and examine their presence in other populations.

A key strength of this study is the deliberate selection of variants for functional annotation, population frequency assessment, and pathogenicity prediction, providing a strong foundation for replication. Inclusion of well-represented variants minimizes misinterpretation and reinforces the importance of studying population-specific variants56. Genetic studies in understudied populations, such as Pakistanis, offer opportunities to identify novel markers. Another strength is the integration of sociodemographic, clinical, lifestyle, and genetic data, providing a holistic view of obesity. Rigorous variant screening and annotation further enhance data reliability. At this point, it is important to mention the limitations of this study. One of these limitations includes the relatively moderate sample size (n = 400). Another limitation is the inclusion of only one gene (UCP3) for NGS analysis, which may overlook other relevant genes or polygenic effects. Finally, the reliance on self-reported lifestyle data may be subject to recall bias. All these limitations are attributable to financial and time constraints.

Conclusion

This study compared sociodemographic, clinical, anthropometric, metabolic, and behavioral parameters between individuals with obesity and normal-BMI control individuals in a Pakistani population. Participants with obesity showed a higher prevalence of physical signs and comorbidities such as abdominal and axillary striae, acanthosis nigricans, hyperlipidemia signs, joint issues, and depression. Among females, irregular menstrual cycles were more common in those with obesity. Anthropometric and metabolic parameters were markedly elevated in individuals with obesity, and aberrant lifestyle patterns were more prevalent in this group. The genetic analysis identified several UCP3 variants, including three found exclusively in individuals with obesity. These variants, located in regulatory regions, may influence obesity risk through modulation of gene expression rather than changes in protein structure. These findings provide population-specific insights that can inform future research on the genetic basis of obesity.

Materials and methods

Study design, work location, and ethical approval

This study used a case-control research design at Dr. Panjwani Center for Molecular Medicine and Drug Research, located at the University of Karachi in Pakistan. The study involved 400 participants, 200 of whom had obesity and 200 were individuals of normal BMI. The study was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) of the International Center for Chemical and Biological Sciences (Ref. No ICCBS-001-BC-2014/Protocol/1.0) and the Advanced Studies and Research Board (ASRB), University of Karachi, Pakistan. A simple random sampling procedure without replacement was used to select participants. Participants with endocrine disorders and a history of medications known to affect body weight were excluded from the study. Pregnant and lactating women were also excluded from the study. Individuals with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 were included in the case category, while participants with a BMI within the range of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2, along with the absence of self-reported or clinically diagnosed obesity-related conditions / metabolic diseases, encompassed the control group. Adult subjects (≥ 20 years old) had their BMI reference ranges based on WHO (World Health Organization) recommendations. However, the BMI reference ranges for individuals under 20 years old were considered according to the CDC (Center for Disease Control and Prevention) growth charts. The demographic data encompassed a broad range of information such as sex, age, marital status, ethnicity, parental consanguinity, and family history of obesity. A written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to their participation in the study. In case of children and adolescents, consent was obtained from their parents or legal guardians. It is important to note that all study protocols were adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and its subsequent amendments or equivalent ethical standards.

Obesity-related physical signs, comorbidities and behavioral traits

A physical examination was conducted to assess for the presence of hyperlipidaemia signs, acanthosis nigricans, and abdominal and axillary striae. Weight-related stigma was assessed via concise, direct, and self-reported questions (framed as yes/no)64. The study participants with obesity (cases) were asked whether they had ever experienced unfair or negative treatment because of their weight, been teased about their weight, or had avoided social or healthcare situations due to fear of judgment for body weight. Information related to comorbidities (Joint problems, depression, and female menstrual cycle) and behavioral factors (eating pattern, diet consciousness, tendency towards fat-dense food, physical activity, lack of sleep, sleep-wake cycle, and shift work) for each participant was collected via a well-designed questionnaire.

Collection of blood samples

A 5-mL blood sample was obtained with a disposable syringe after fasting for 8 to 12 h. A 2-mL blood sample was taken into a yellow-top vacutainer tube for serum isolation. The serum was taken in a 2 mL microfuge tube for further biochemical analyses. One mL of blood was taken into a grey-top tube containing an antiglycolytic agent for determining FBG concentration. Finally, a 2 mL blood sample was collected in an EDTA-coated lavender-capped vacutainer tube for DNA extraction.

Anthropometric measurements

During the study, detailed anthropometric data was collected from each participant, including measurements of body height, weight, waist circumference (WC), hip circumference (HC), and various skinfold thicknesses to compute %BF. Measurements were recorded while wearing lightweight clothing. Participants were instructed to stand upright and remain relaxed during measurements. Body weight (in kilograms) and height (in centimeters) were measured by a weight and height machine (TCS-180 L, Capacity 180 kg×50 g, KINLee ®). The BMI of adults was calculated using the online BMI calculator of NIH (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmicalc.htm). For children and adolescents, BMI was determined using percentiles. WC was measured in centimeters using a non-stretchable measuring tape by wrapping it at the midpoint between the hip bone and ribs. To ensure precision, WC was measured after expiration. HC was also measured in centimeters by placing a non-stretchable measuring tape around the widest area of the buttocks. The waist, height, and hip circumference measurements were used to calculate the waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) by dividing WC by height and the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) by dividing WC by HC. Skinfold thickness at different body locations, such as biceps, triceps, abdomen, sub-scapular, supra iliac, and thighs, was assessed using a skinfold caliper (Model # C-120B, Slim guide, MI, USA). Skinfold thickness measurements were used to calculate %BF using equations appropriate to each sex, as outlined by Jackson and Pollock in 198565.

Metabolic parameters

The metabolic assessments comprised blood pressure, fasting insulin, FBG, and lipid profile. For accurate and consistent measurement of systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), the participant was instructed to sit comfortably and remain at rest before measuring blood pressure. The blood pressure was measured from the right arm of each participant. A digital blood pressure monitor (Model CH-453-AC, CITIZEN SYSTEMS, JAPAN) and blood pressure cuff (Model SCN-003, CITIZEN SYSTEMS, JAPAN) were used for blood pressure assessment. The fasting insulin concentration was measured by sandwich immunoassay using Elecsys Insulin assay (Catalog number 12017547 122 Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN 46250, US) on an automatic immunochemistry analyzer (Roche Hitachi cobas e 411). The levels of FBG (Catalog number 5.17604.0001, Martin Dow, France), TC (Catalog number 5.17501.0001, Martin Dow, France), TGs (Catalog number 5.17511.0001, Martin Dow, France), HDL-C (Catalog number 5.17518.0001, Martin Dow, France), and LDL-C (Catalog number 5.17519.0001, Martin Dow, France) were measured via end-point enzymatic-colorimetric-based assay kits on automatic chemistry analyzer (Selectra Pro M Lite, France). The estimated VLDL-C levels were obtained by dividing the TG concentrations by 5. Moreover, by computing the values from different anthropometric and biochemical assessments, additional parameters such as HOMA-IR, VAI (mmol L−1), LAP (mmol L−1), TyG index (product of triglyceride and glucose), coronary risk index (CRI), atherogenic index (AI), TG/HDL-C (triglyceride-to-HDL-C ratio) were calculated. HOMA-IR was calculated using the formula suggested by Matthews et al.66. To calculate VAI46 and LAP67 gender-specific formulae were used. The formula suggested by Simental-Mendia et al.68 was used to calculate TyG index. For calculating VAI and LAP, the values of TGs and HDL‐C were converted into mmol L−1 by multiplying the TG values by 0.0113 and HDL-C values by 0.0259. CRI was considered as the ratio of TC-to-HDL-C, and AI was taken as the ratio of LDL-C-to-HCL-C.

DNA extraction and NGS

DNA was isolated from total blood using the genomic DNA purification kit (ZYMO RESEARCH, catalog number D4068, CA, US) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The horizontal agarose gel electrophoresis (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) was conducted to evaluate the overall integrity of the genomic DNA. The isolated DNA was quantified using a NanoDrop™ spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). The UCP3 gene sequence from the NCBI Reference Sequence (RefSeq: NC_000011.9) was used as the basis for primer design. The forward (AGCGTCCACAGCTTAAAGGAG) and reverse primers (TTGGAAGTCGGTCGTCTGG) were designed using the free online tool Primer3 (v. 0.4.0) (https://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3-0.4.0/). The UCP3 gene is positioned at 73711322 (start) − 73720130 (end) on chromosome 11. For amplification of the UCP3 gene, the upstream and downstream regions were also considered (73711111–73720334). Thus, the final product size was found to be 9224 bp. The UCP3 was amplified by long-range PCR using 2X Invitrogen Platinum SuperFi II PCR Master Mix (Catalog number 12368010, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Purification of PCR products was done using an automated Agencourt AMPure XP purification system (Kit Part number A63880, BECKMAN COULTER, MA, USA). The Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit (Catalog number Q32854, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) was employed for the quantification of the amplicon. The concentration of amplicon in all the samples was adjusted to a range of 0.2-0.3 ng/µL. The amplicon was sequenced by preparing a paired-end DNA library by using the Nextera XT DNA library prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, US) using the reference guide. For this, 1 ng of purified PCR product was used. The pooled library was diluted for sequencing on the Illumina® MiSeq® system (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). For this, 10 µL of each library was added in a clean and sterile 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube to create a multiplexed library pool.

Bioinformatic analysis

Raw sequencing reads were assessed using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) to evaluate base quality69. Low-quality reads were trimmed using Trimmomatic70 and high-quality paired-end reads were aligned to the human reference genome (GRCh37/hg19) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner with the maximum exact matches71. Resulting SAM files were converted to BAM format and processed with SAMtools version 0.1.1972 and PICARD (version 1.109; http://picard.sourceforge.net)73 for sorting, duplicate removal, and read group assignment. Variant calling was performed using the HaplotypeCaller tool in Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK v3.2) applying a quality score threshold of 30, following realignment around insertions and deletions and base quality score recalibration74. Individual GVCF files were merged using GenotypeGVCFs, and variants were filtered based on depth (DP < 20), genotype quality (GQ < 20), and overall quality (QUAL < 50). Variant Quality Score Recalibration was applied to improve variant call accuracy using established training datasets75. Variants outside the target region (chr11:73711111–73720334) were excluded, along with monomorphic sites, singletons, and variants exclusive to controls (non-disease-associated variants). Final variant sets were used for downstream analyses including functional annotation, population frequency assessment, and pathogenicity prediction.

Variant annotation, population frequency comparison, and functional impact assessment

To interpret the NGS results, all variants types (single nucleotide polymorphisms and indels) were considered, including those in 3’ and 5’ untranslated regions (UTRs), intronic regions, exonic regions (missense, synonymous, and frameshift), and variants near splice sites76. The variant annotation was performed using the ANNOVAR tool (v2014)77. For further analysis, the annotated VCF file was converted to an MS Excel-compatible format using tab-delimited settings. For maximum accuracy and comprehensive funactional annotations, the variants were analyzed using the web-based human VEP (Ensembl GRCh37 release 113) (https://www.ensembl.org/info/docs/tools/vep/index.html). The VEP output showed the consequence, impact, the intron or exon number, protein position, and amino acid. It also showed whether the variant is novel or already existing. The scores of CADD and delta scores of SpliceAI (v1.3) prediction from the VEP tool were also used to explore putative functional implications. The CADD PHRED-scaled scores were considered to estimate the potential deleteriousness of each variant78. However, SpliceAI predictions were extracted to assess the predicted effect of variant on splicing through acceptor gain/loss or donor gain/loss79,80. Moreover, RegulomeDB scores (v2.0) were used to assess the likelihood of a variant being located within a regulatory region81. The variants of interest (VOIs) were further examined using publicly accessible genetic databases. To evaluate the allele frequencies of the variants, comparisons were made with genetic data from South Asian and global population available in the gnomAD v2.1.1 (https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org). ClinVar (a curated repository of human genetic variant-phenotype associations; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) was also used to check the pathogenicity (pathogenic, likely pathogenic, variant of uncertain significance, likely benign or benign) of the VOIs if they are present on the database82. The variants which were not reported in ClinVar were searched in dbSNP. All databases and tools were accessed in March, 2025.

Sample size calculation

The Calculator.net sample size tool (available at: https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html) was used for estimating sample size of the study. A minimum sample of 375 participants was required based on a population size of 235,001,746 (Pakistan’s estimated population in 2020, according to Worldometer; available at: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/pakistan-population/) and a generalized obesity prevalence of 57.9% as reported in a prior study83 with a 95% confidence level and 5% margin of error. Thus, a total of 400 participants were included in the study, exceeding this requirement.

Statistical analysis

Age categories and obesity age onset were presented as counts with percentages. All categorical variables were analysed using the chi-square test. Normality of continuous parameters was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, with a p-value < 0.05 indicating non-normal distribution. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were expressed as median with interquartile range, while normally distributed parameters were represented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparative analysis of continuous parameters between cases (individuals with obesity) and normal-BMI controls was performed by the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data, providing mean ranks, and p-values, whereas for parameters with normal distribution t-test was employed. All association analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control for false discovery rates84. Statistical significance was determined by a p-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25. The treemaps illustrating the distribution of ethnicities were generated using RAWGraphs 2.0, an open-source web-based tool for visual data representation (https://app.rawgraphs.io/)85.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 894, i–xii, 1–253. (2000).

Kelly, T., Yang, W., Chen, C. S., Reynolds, K. & He, J. Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 32, 1431–1437. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2008.102 (2008).

Frayling, T. M. Are the causes of obesity primarily environmental? No. Bmj 345, e5844. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e5844 (2012).

Wardle, J., Carnell, S., Haworth, C. M. & Plomin, R. Evidence for a strong genetic influence on childhood adiposity despite the force of the obesogenic environment. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87, 398–404. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.2.398 (2008).

Silventoinen, K., Rokholm, B., Kaprio, J. & Sørensen, T. I. The genetic and environmental influences on childhood obesity: A systematic review of twin and adoption studies. Int. J. Obes. (Lond). 34, 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2009.177 (2010).

Jia, J. J., Zhang, X., Ge, C. R. & Jois, M. The polymorphisms of UCP2 and UCP3 genes associated with fat metabolism, obesity and diabetes. Obes. Rev. 10, 519–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00569.x (2009).

Brondani, L. A. et al. The role of the uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) on the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arq. Bras. Endocrinol. Metabol. 56, 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0004-27302012000400001 (2012).

Jamal, N. et al. Safety, efficacy, and mechanism of action of herbs used for obesity management: A thematic review. Obes. Med. 32, 100415 (2022).

Brownstein, A. J., Veliova, M., Acin-Perez, R., Liesa, M. & Shirihai, O. ATP-consuming futile cycles as energy dissipating mechanisms to counteract obesity. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 23, 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-021-09690-w (2022).

Ricquier, D. & Bouillaud, F. Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins: From mitochondria to the regulation of energy balance. J. Physiol. 529 Pt 1, 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00003.x (2000).

Brand, M. D. et al. Mitochondrial superoxide: Production, biological effects, and activation of uncoupling proteins. Free Radic Biol. Med. 37, 755–767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.05.034 (2004).

Brand, M. D. & Esteves, T. C. Physiological functions of the mitochondrial uncoupling proteins UCP2 and UCP3. Cell. Metab. 2, 85–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2005.06.002 (2005).

Rankinen, T. et al. The human obesity gene map: The 2005 update. Obes. (Silver Spring). 14, 529–644. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2006.71 (2006).

Boss, O., Muzzin, P. & Giacobino, J. P. The uncoupling proteins, a review. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 139, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1530/eje.0.1390001 (1998).

Solanes, G., Vidal-Puig, A., Grujic, D., Flier, J. S. & Lowell, B. B. The human uncoupling protein-3 gene. Genomic structure, chromosomal localization, and genetic basis for short and long form transcripts. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 25433–25436. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.272.41.25433 (1997).

Vidal-Puig, A., Solanes, G., Grujic, D., Flier, J. S. & Lowell, B. B. UCP3: An uncoupling protein homologue expressed preferentially and abundantly in skeletal muscle and brown adipose tissue. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 235, 79–82. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1997.6740 (1997).

Hesselink, M. K. et al. Protein expression of UCP3 differs between human type 1, type 2a, and type 2b fibers. Faseb J. 15, 1071–1073 (2001).

Schrauwen, P. et al. Uncoupling protein 3 as a mitochondrial fatty acid anion exporter. FASEB J. 17, 2272–2274 (2003).

Schrauwen, P. The role of uncoupling protein 3 in fatty acid metabolism: Protection against lipotoxicity? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 63, 287–292 (2004).

Weigle, D. S. et al. Elevated free fatty acids induce uncoupling protein 3 expression in muscle: A potential explanation for the effect of fasting. Diabetes 47, 298–302. https://doi.org/10.2337/diab.47.2.298 (1998).

Tsuboyama-Kasaoka, N. et al. Up-regulation of uncoupling protein 3 (UCP3) mRNA by exercise training and down-regulation of UCP3 by denervation in skeletal muscles. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 247, 498–503. https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1998.8818 (1998).

Schrauwen, P. et al. Effect of acute exercise on uncoupling protein 3 is a fat metabolism-mediated effect. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 282, E11–17. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpendo.2002.282.1.E11 (2002).

Schrauwen, P., Hoppeler, H., Billeter, R., Bakker, A. H. & Pendergast, D. R. Fiber type dependent upregulation of human skeletal muscle UCP2 and UCP3 mRNA expression by high-fat diet. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 25, 449–456. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801566 (2001).

Boss, O. et al. Effect of endurance training on mRNA expression of uncoupling proteins 1, 2, and 3 in the rat. Faseb J. 12, 335–339. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.12.3.335 (1998).

Vidal-Puig, A. et al. Effects of obesity and stable weight reduction on UCP2 and UCP3 gene expression in humans. Obes. Res. 7, 133–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00694.x (1999).

Saltzman, E. & Roberts, S. B. The role of energy expenditure in energy regulation: Findings from a decade of research. Nutr. Rev. 53, 209–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.1995.tb01554.x (1995).

Schrauwen, P., Xia, J., Bogardus, C., Pratley, R. E. & Ravussin, E. Skeletal muscle uncoupling protein 3 expression is a determinant of energy expenditure in Pima Indians. Diabetes 48, 146–149. https://doi.org/10.2337/diabetes.48.1.146 (1999).

Pohl, E. E., Rupprecht, A., Macher, G. & Hilse, K. E. Important trends in UCP3 investigation. Front. Physiol. 10, 470. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2019.00470 (2019).

Hesselink, M. K., Mensink, M. & Schrauwen, P. Human uncoupling protein-3 and obesity: An update. Obes. Res. 11, 1429–1443. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2003.192 (2003).

Simmonds, M., Llewellyn, A., Owen, C. G. & Woolacott, N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 17, 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12334 (2016).

Lipowicz, A., Gronkiewicz, S. & Malina, R. M. Body mass index, overweight and obesity in married and never married men and women in Poland. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 14, 468–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.10062 (2002).

Moghimi-Dehkordi, B. et al. Overweight and obesity and related factors in urban Iranian population aged between 20 to 84 years. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 3, 171–176. https://doi.org/10.4103/2141-9248.113656 (2013).

Tang, F., Pan, Y. & Deng, H. Effect of marriage on overweight and obesity: Evidence from China. BMC Public. Health. 24, 3591. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-21184-3 (2024).

Averett, S. L., Sikora, A. & Argys, L. M. For better or worse: Relationship status and body mass index. Econ. Hum. Biol. 6, 330–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2008.07.003 (2008).

Luppino, F. S. et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 67, 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2 (2010).

Hirt, P. A., Castillo, D. E., Yosipovitch, G. & Keri, J. E. Skin changes in the obese patient. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 81, 1037–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.12.070 (2019).

Klop, B., Elte, J. W. & Cabezas, M. C. Dyslipidemia in obesity: Mechanisms and potential targets. Nutrients 5, 1218–1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5041218 (2013).

Lai, S. W., Ng, K. C., Lin, H. F. & Chen, H. L. Association between obesity and hyperlipidemia among children. Yale J. Biol. Med. 74, 205–210 (2001).

Hartz, A. J. et al. The association of obesity with joint pain and osteoarthritis in the HANES data. J. Chronic Dis. 39, 311–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/0021-9681(86)90053-6 (1986).

Piqueras, P. et al. Anthropometric indicators as a tool for diagnosis of obesity and other health risk factors: A literature review. Front. Psychol. 12, 631179. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.631179 (2021).

Grundy, S. M. Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 89, 2595–2600. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-0372 (2004).

Abbasi, F., Malhotra, D., Mathur, A., Reaven, G. M. & Molina, C. R. Body mass index and waist circumference associate to a comparable degree with insulin resistance and related metabolic abnormalities in South Asian women and men. Diab Vasc Dis. Res. 9, 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/1479164111433578 (2012).

McLaughlin, T. et al. Use of metabolic markers to identify overweight individuals who are insulin resistant. Ann. Intern. Med. 139, 802–809. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00007 (2003).

Nusrianto, R. et al. Visceral adiposity index and lipid accumulation product as a predictor of type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Bogor cohort study of non-communicable diseases risk factors. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 155, 107798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2019.107798 (2019).

Yu, S. R. & Shin, K. A. Visceral adiposity index and lipid accumulation product as effective markers of different obesity phenotypes in Korean adults: A cross-sectional analysis. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 16, 495–504. https://doi.org/10.2147/dmso.S397043 (2023).

Amato, M. C. et al. Visceral adiposity index: A reliable indicator of visceral fat function associated with cardiometabolic risk. Diabetes Care. 33, 920–922. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc09-1825 (2010).

Pot, G. K., Almoosawi, S. & Stephen, A. M. Meal irregularity and cardiometabolic consequences: Results from observational and intervention studies. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 75, 475–486. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0029665116000239 (2016).

Pereira, M. A. et al. Fast-food habits, weight gain, and insulin resistance (the CARDIA study): 15-year prospective analysis. Lancet 365, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(04)17663-0 (2005).

Brugnara, L. et al. Low physical activity and its association with diabetes and other cardiovascular risk factors: A nationwide, Population-Based study. PLoS One. 11, e0160959. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160959 (2016).

Tse, L. A. et al. Timing and length of nocturnal sleep and daytime napping and associations with obesity types in High-, Middle-, and Low-Income countries. JAMA Netw. Open. 4, e2113775. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13775 (2021).

Liu, Q. et al. Is shift work associated with a higher risk of overweight or obesity? A systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47, 1956–1971. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy079 (2018).

van Strien, T., Herman, C. P. & Verheijden, M. W. Eating style, overeating, and overweight in a representative Dutch sample. Does external eating play a role? Appetite 52, 380–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.11.010 (2009).

Mazur, A. US trends in feminine beauty and overadaptation. J. Sex Res. 22, 281–303 (1986).

Maurano, M. T. et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science 337, 1190–1195. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1222794 (2012).

Schrauwen, P. & Hesselink, M. UCP2 and UCP3 in muscle controlling body metabolism. J. Exp. Biol. 205, 2275–2285. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.205.15.2275 (2002).

Popejoy, A. B. & Fullerton, S. M. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature 538, 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1038/538161a (2016).

Fatumo, S. et al. A roadmap to increase diversity in genomic studies. Nat. Med. 28, 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-021-01672-4 (2022).

Mather, C. A. et al. CADD score has limited clinical validity for the identification of pathogenic variants in noncoding regions in a hereditary cancer panel. Genet. Med. 18, 1269–1275. https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.44 (2016).

Rentzsch, P., Schubach, M., Shendure, J. & Kircher, M. CADD-Splice-improving genome-wide variant effect prediction using deep learning-derived splice scores. Genome Med. 13, 31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-021-00835-9 (2021).

Grzybowski, J. et al. P644: Unlocking the code: When spliceai falls short in variant assessment. Genetics Med. Open 2, 101550 (2024).

Cheng, M. et al. Computational analyses of obesity associated loci generated by genome-wide association studies. PloS One. 13, e0199987 (2018).

Hull, J. et al. Identification of common genetic variation that modulates alternative splicing. PLoS Genet. 3, e99. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0030099 (2007).

Azzu, V. & Brand, M. D. The on-off switches of the mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 35, 298–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibs.2009.11.001 (2010).

Schafer, M. H. & Ferraro, K. F. The stigma of obesity: Does perceived weight discrimination affect identity and physical health? Social Psychol. Q. 74, 76–97 (2011).

Jackson, A. S. & Pollock, M. L. Practical assessment of body composition. Physician Sportsmed. 13, 76–90 (1985).

Matthews, D. R. et al. Homeostasis model assessment: Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00280883 (1985).

Kahn, H. S. The lipid accumulation product performs better than the body mass index for recognizing cardiovascular risk: A population-based comparison. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-5-26 (2005).

Simental-Mendia, L. E., Rodriguez-Moran, M. & Guerrero-Romero, F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 6, 299–304. https://doi.org/10.1089/met.2008.0034 (2008).

Andrews, S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data, https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2010).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Li, H. et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Hwang, S., Kim, E., Lee, I. & Marcotte, E. M. Systematic comparison of variant calling pipelines using gold standard personal exome variants. Sci. Rep. 5, 17875 (2015).

McKenna, A. et al. The genome analysis toolkit: A mapreduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010).

Lek, M. et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536, 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature19057 (2016).

Manco, L. et al. Next-generation sequencing of 12 obesity genes in a Portuguese cohort of patients with overweight and obesity. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 66, 104728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmg.2023.104728 (2023).

Wang, K., Li, M. & Hakonarson, H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e164–e164 (2010).

Rentzsch, P., Witten, D., Cooper, G. M., Shendure, J. & Kircher, M. CADD: Predicting the deleteriousness of variants throughout the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D886–d894. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1016 (2019).

Haque, B. et al. Estimating the proportion of nonsense variants undergoing the newly described phenomenon of manufactured splice rescue. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 32, 238–242. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-023-01495-6 (2024).

Kaltak, M., Corradi, Z., Collin, R. W. J., Swildens, J. & Cremers, F. P. M. Stargardt disease-associated missense and synonymous ABCA4 variants result in aberrant splicing. Hum. Mol. Genet. 32, 3078–3089. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddad129 (2023).

Boyle, A. P. et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 22, 1790–1797. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.137323.112 (2012).

Landrum, M. J. et al. ClinVar: Public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D980–D985 (2014).

Basit, A., Askari, S., Zafar, J., Riaz, M. & Fawwad, A. NDSP 06: Prevalence and risk factors for obesity in urban and rural areas of pakistan: A study from second National diabetes survey of Pakistan (NDSP), 2016–2017. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 15, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orcp.2020.11.007 (2021).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. Roy. Stat. Soc. Ser. B (Methodol.). 57, 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x (1995).

Mauri, M., Elli, T., Caviglia, G., Uboldi, G. & Azzi, M. In Proceedings of the 12th Biannual Conference on Italian SIGCHI Chapter Article 28 (Association for Computing Machinery, Cagliari, Italy, 2017).

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to the participants of the study for their participation in the study.

Funding

This research was mainly supported by a research grant from the Higher Education Commission (HEC) of Pakistan (Ref. No. 5740/Sindh/NRPU/R&D/HEC/2016) and also by a recurring grant provided by the International Center for Chemical and Biological Sciences (ICCBS), University of Karachi. The funders had no role in the design of the study, collection of samples, data analysis and interpretation, or the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R. conceived and designed the study, acquired funding, contributed to data collection and interpretation, and critically revised the manuscript. A.A.B. performed the experiments, contributed to data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, and wrote the manuscript. M.K. contributed in methodology. H.N. contributed in methodology. M.I. helped in NGS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bhatti, A.A., Rana, S., Khalid, M. et al. UCP3 gene variants and obesity in a Pakistani sample population. Sci Rep 15, 33135 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18434-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18434-8