Abstract

Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins play a crucial role in the desiccation tolerance of resurrection plants, although their exact functions remain unclear. Therefore, we recombinantly produced desiccation-induced LEA4 protein member, RsLEAP30-His6, from Ramonda serbica and investigated its structural behaviour under simulated dehydration conditions. This is the first report on the production and purification of a recombinant LEA protein from the resurrection plant R. serbica. By immobilised metal affinity and size-exclusion chromatography, we successfully obtained RsLEAP30-His6 with a purity of over 95%, thus providing a robust and scalable method that can also be used for the production of other LEA proteins. Structural characterisation by circular dichroism spectroscopy in combination with in silico modelling, revealed that RsLEAP30 is predominantly disordered under fully hydrated conditions, whereas it adopts an α-helical structure under desiccation-like conditions and in the presence of a lipid mimetic. This disorder-to-order transition underpins the possible protective role of RsLEAP30 in chloroplasts, likely through interactions with thylakoids and desiccation-sensitive proteins enabling the rapid recovery of photosynthetic components upon rehydration. Our study provides new insights into the structure–function relationship of LEA proteins in desiccation tolerance and creates a basis for future bioengineering strategies to improve crop drought tolerance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cellular water loss leads to protein denaturation, aggregation, and degradation. It disrupts membrane lipid fluidity, impairs membrane integrity and function and reduces cell volume1. Coping with dehydration is a major challenge for all terrestrial organisms, particularly sessile organisms like plants.

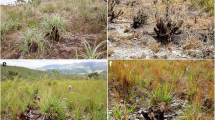

In the course of their evolution and adaptation to terrestrial environments, plants have developed multilevel mechanisms to mitigate the effects of water loss. These strategies include intricate signalling pathways that regulate processes such as stomatal opening and the formation of waxy and suberized cuticles on the surface of vegetative organs2, allowing most plants to tolerate up to 60% water loss3. However, a specialised group of vascular plants, comprising approximately 300 flowering species and known as resurrection plants, has evolved the remarkable ability to survive extreme dehydration. i.e. desiccation. When the relative water content drops below 5%, they enter a state of anhydrobiosis, while they rapidly restore full physiological function after rehydration1,4. Among them are three ancient homoiochlorophyllous resurrection plant species from the Gesneriaceae family: Haberlea rhodopensis, Ramonda nathaliae and R. serbica, which are endemic to the Balkan Peninsula5. Homoiochlorophyllous plants retain their chlorophyll during desiccation and can quickly resume photosynthesis after rehydration, whereas poikilochlorophyllous plants lose most or all of their chlorophyll during desiccation and have to resynthesise it after rehydration6.

Resurrection plants have evolved the unique vegetative mechanisms of desiccation tolerance, which are considered critical steps in the evolution of primitive land plants7. A key component of their resilience is the upregulation of genes encoding protective proteins, notably heat shock proteins (HSPs) and late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins8. LEA proteins were first identified four decades ago in cotton seeds (Gossypium hirsutum), where they were found to be involved in the late stages of seed maturation9. Subsequent research has shown that they play a broader role in protecting vegetative tissue under environmental stress conditions such as drought, salinity, and low temperatures10,11. LEA proteins are not exclusive to plants. They have also been found in other desiccation-tolerant organisms, including bacteria and certain invertebrates, underscoring their evolutionary importance for adaptation to stress12.

LEA proteins are structurally heterogeneous, predominantly hydrophilic proteins and are considered intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs)13. IDPs are defined by their lack of stable secondary and tertiary structures, containing intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) that enable functional flexibility14. In their fully hydrated state, LEA proteins primarily adopt random conformations, but during desiccation they fold into more compact α-helical structures11,15.

These proteins may play a crucial role in stabilising cellular structures, minimising damage during desiccation, and facilitating a rapid return to homeostasis upon rehydration8,16. LEA proteins may act as molecular shields by mimicking water molecules to protect molecular surfaces during desiccation17. Additionally, LEA proteins may stabilise cell membranes18, maintain the integrity of glassy sugar matrices19, chelate redox-active metal ions, and attenuate the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS)10. LEA proteins are also thought to increase the structural integrity and intracellular viscosity of cells during desiccation by forming intracellular proteinaceous condensates20,21. Recently, it has been shown that the dynamic assembly and disassembly of these proteinaceous condensates regulate the availability of free water, ensuring a well-buffered cytoplasmic environment22. Despite all these studies, the exact cellular functions of LEA proteins and their specific intracellular partners remain largely unclear23.

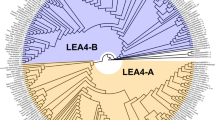

In our previous studies, we identified 318 LEA proteins from R. serbica and classified them into seven protein families based on their physicochemical properties24. Among them, RsLEA30 protein (RsLEAP30), a 254-amino acid member of the LEA4 protein group, exhibited a twofold increase in expression and accumulation in desiccated R. serbica leaves compared to fully hydrated ones25. Secondary structure predictions using several algorithms (JPred, Sopma, FELLS, PsiPred, Phyre2) indicate that over 95% of the amino acid sequence of RsLEAP30 has a strong propensity to form α-helices24. However, disorder prediction tools showed that about 85% of the sequence is intrinsically disordered, indicating its structural plasticity under different conditions.

Current efforts to improve drought tolerance in crops focus on biotechnological and synthetic biology strategies that incorporate drought-resistant traits. This emphasises the importance of resurrection plants as model systems for understanding the mechanisms of drought tolerance4. To fully understand the molecular mechanisms of desiccation tolerance, it is important to understand the physiological function of LEA proteins, which play a key role in this phenomenon.

In this study, we aimed to characterise the structural properties of desiccation-induced RsLEAP30 and thereby contribute to a broader understanding of intrinsically disordered stress proteins. We developed a protocol for the production of pure recombinant RsLEAP30-His6 in Escherichia coli and investigated its secondary structure in vitro.

Results

Expression of GBP-RsLEAP30 on a small scale

To overcome the inherent challenges of producing the intrinsically disordered RsLEAP30 in Escherichia coli—namely, its susceptibility to proteolysis, aggregation, and inclusion body formation—we fused it with chain A of the immunoglobulin G-binding protein (GBP). The successful expression of GBP-RsLEAP30 (theoretical molecular weight, Mw = 37 kDa) in E. coli BL21(DE3) was confirmed by western blot analysis with anti-His tag antibodies. A dominant band corresponding to approximately 46 kDa was detected when protein expression was induced by 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Fig. 1a). A negative control showed no visible band corresponding to GBP-RsLEAP30.

Production of GBP-RsLEAP30 in E. coli BL21(DE3) in the presence or absence of IPTG inducer. (a) Western blot of GBP-RsLEAP30 using anti-His antibody, after 3 h induction at 37 °C. Optimisation of GBP-RsLEAP30 production over a 24 h period at 25 °C (b), 30 °C (c), and 37 °C (d). Equal volumes of total protein extracts were loaded onto gels, which were subsequently stained and scanned according to a standardised procedure. The amounts of GBP-RsLEAP30 and total E. coli proteins were quantified using ImageJ. The purity of GBP-RsLEAP30 is expressed as a ratio of the GBP-RsLEAP30 amount to the total E. coli protein amount. (e) Solubility analysis of GBP-RsLEAP30 over 24 h of incubation at 37 °C (p, pellet; s, supernatant). (f) Western blot analysis of pellet (p) and supernatant (s) fractions of GBP-RsLEAP30 using an anti-His antibody. The molecular weight (Mw) of the markers was specified in kDa (MWP06, NIPPON Genetics, Düren, Germany). "0", samples before induction;"−"conditions without IPTG addition;"+"induction with 1 mM IPTG. The red arrowhead indicates the band corresponding to GBP-RsLEAP30.

To determine the optimal conditions for GBP-RsLEAP30 expression in E. coli BL21(DE3), protein expression was examined at three different temperatures (25 °C, 30 °C, and 37 °C) over a 24-h period. The accumulation of GBP-RsLEAP30 was detectable already within 30 min at all tested temperatures (Figs. 1b, 1c, 1 d, Supplementary Fig. S1). As expected, the highest total yield of GBP-RsLEAP30 was achieved after 24 h, particularly at 25 °C. However, the amount of total E. coli proteins was also significantly increased after 24 h at all temperatures. The initial rate of GBP-RsLEAP30 production was the greatest at 25 °C (Supplementary Fig. S1), where after 3 h of incubation, the amount of GBP-RsLEAP30 reached 33.1% of the maximum amount of GBP-RsLEAP30 produced (after 24 h at 25 °C). At 30 °C after 2 h of incubation, the amount of GBP-RsLEAP30 reached 20.3%. However, the production rate of GBP-RsLEAP30 at 30 °C decreased over the following 2 h (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. S1). Based on the obtained amounts of GBP-RsLEAP30 and the ratio of GBP-RsLEAP30 amount to total E. coli protein amount (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. S1), a 4-h incubation at 37 °C was selected as the optimal condition for the production of GBP-RsLEAP30 in E. coli BL21(DE3).

Solubility test and purification of GBP-RsLEAP30

The protein purification protocol varies depending on whether the protein is soluble or forms inclusion bodies. To assess the solubility of intracellularly synthesised GBP-RsLEAP30, the cell pellets were resuspended in Tris–HCl buffer, lysed, and GBP-RsLEAP30 was extracted from the pellet, and the supernatant. These fractions were then separated by SDS-PAGE and stained (Fig. 1e). GBP-RsLEAP30 was detected exclusively in the supernatant (indicated by bands at ~ 46 kDa) and not in the pellet (confirmed by western blot, Fig. 1f), suggesting that GBP-RsLEAP30 is soluble in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells.

Given that GBP-RsLEAP30 is His8 tagged, the first step of its purification involved immobilised metal affinity chromatography (IMAC). An isocratic elution with 300 mM imidazole was chosen as the most efficient method to elute GBP-RsLEAP30 (Figs. 2a, 2b). Remarkably, a significant fraction (70.4%) of the applied GBP-RsLEAP30 was not retained by the column, as shown by the strong band (~ 46 kDa, Figs. 2b, 2c) in the flow-through (FT) fraction (Table 1).

Purification of GBP-RsLEAP30. (a) Representative IMAC chromatogram of GBP-RsLEAP30 elution. The peak containing GBP-RsLEAP30 was eluted with 300 mM imidazole. (b) SDS-PAGE analysis of collected fractions from IMAC; FT, flow-through. (c) Western blot analysis of the IMAC fractions using an anti-His antibody. The molecular weight (Mw) of the markers is indicated in kDa (MWP06, NIPPON Genetics, Düren, Germany). The red arrowhead indicates the band corresponding to GBP-RsLEAP30.

In total, approximately 15% of the GBP-RsLEAP30 applied to the column was recovered with 300 mM imidazole, corresponding to 2.1 mg per g of wet biomass. The purity of GBP-RsLEAP30 in these fractions was almost 91% (Table 1).

Digestion of GBP-LEAP30

To remove the fusion partner and His tag (expected Mw: 9.6 kDa) from GBP-RsLEAP30 and obtain Gly-RsLEAP30 (RsLEAP30 with a Gly residue at the N-terminus; expected Mw: 27.3 kDa), TEV protease digestion was attempted. Various factors, including pH (7–8), temperature (4–37 °C), incubation time (2–24 h), and the presence of different detergents: 0.05–0.1% Triton X-100, 0.05–0.1% Tween 20, 0.05–0,1% dodecylmaltoside (DDM); 0.1 M urea; reducing agents: 0.6–15 mM cysteine, 0.5–1 mM cystine, 1–20 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.6–20 mM reduced glutathione (GSH), 0.15–0.50 mM oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and their combinations, as well as different molar ratios of enzyme to substrate (1:1, 1:2, 1:5, 1:6, 1:25) and 0.5–2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), were systematically tested. Despite these extensive optimisations, efficient proteolysis was not achieved, although TEV protease activity was confirmed with other recombinant proteins containing its recognition site (data not shown).

Given the inefficiency of TEV digestion, an alternative strategy was pursued. A new RsLEAP30-His6 construct was designed and subcloned to allow the expression of RsLEAP30 containing only a His6-tag at the C-terminus, eliminating the need for post-expression cleavage.

Small-scale production of RsLEAP30-His6

The expression of RsLEAP30-His6 (theoretical Mw: 28 kDa) in E. coli BL21(DE3) was verified by western blot analysis with an anti-His antibody (Fig. 3a). When analysed by SDS-PAGE, the overexpressed RsLEAP30-His6 displayed three bands (Figs. 3b, 3c, 3 d). The higher mobility band (RsLEAP30-His6H) corresponded to 31.2 kDa, the intermediate mobility band, RsLEAP30-His6M, corresponded to a Mw of 29.5 kDa and the lower mobility band (RsLEAP30-His6L form) corresponded to a Mw of 25.6 kDa. These bands were absent in the non-induced control and were all visualised by the anti-His antibody (Fig. 3e).

RsLEAP30-His6 production in E. coli BL21 (DE3). (a) Western blot analysis of RsLEAP30-His6 using an anti-His antibody. Optimisation of RsLEAP30-His6 production over a period of 24 h at 25 °C (b), 30 °C (c) and 37 °C (d). Equal volumes of total protein extracts were loaded onto gels, which were subsequently stained and scanned according to a standardised procedure. The amounts of RsLEAP30-His6 and total E. coli proteins were quantified using ImageJ. The purity of RsLEAP30-His6 is expressed as a ratio of the RsLEAP30-His6 amount to the total E. coli protein amount. (e) Separation of three RsLEAP30-His6 forms obtained at 37 °C, 3 h after induction. RsLEAP30-His6H, RsLEAP30-His6M, and RsLEAP30-His6L forms are pointed by arrows. (f) Solubility analysis of RsLEAP30-His6 over a 24-h incubation at 37 °C (p, pellet; s, supernatant). The molecular weight (Mw) of the markers is indicated in kDa (MWP06, NIPPON Genetics, Düren, Germany). "0", samples before induction;"−"conditions without IPTG addition;"+"induction with 1 mM IPTG. The red arrowheads indicate the bands corresponding to RsLEAP30-His6 forms.

As with GBP-RsLEAP30 production, the expression conditions (temperature and induction time) were optimised for RsLEAP30-His6 production at a small scale. Unlike GBP-RsLEAP30, temperature was not a critical factor, as RsLEAP30-His6 yield remained similar at 25 °C, 30 °C, and 37 °C (Figs. 3b, 3c, 3 d). The highest RsLEAP30-His6 production was observed after 24 h of induction (Supplementary Fig. S2); however, this also resulted in a significant increase in E. coli host proteins at all temperatures. The highest RsLEAP30-His6-to-host protein ratio was observed after 2 and 3 h of induction at 30 °C (Fig. 3c). The highest amount of RsLEAP30-His6 was achieved at 37 °C after 3 and 4 h (64% and 76%, respectively) with a similar ratio of RsLEAP30-His6 to total E. coli protein content (Fig. 3d, Supplementary Fig. S2).

Based on these results, a 3-h induction at 37 °C was determined as the optimal condition for RsLEAP30-His6 production in E. coli BL21(DE3).

Solubility test, purification, and validation of RsLEAP30-His6

To evaluate the solubility of RsLEAP30-His6 under the optimised expression conditions, cell pellets collected at different time points were resuspended in Tris–HCl buffer, lysed, and separated into pellet and supernatant fractions. RsLEAP30-His6 was consistently detected in the soluble fraction, regardless of incubation time, indicating its solubility in E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Fig. 3f).

To refine the first purification step, IMAC elution conditions (10–300 mM imidazole) were optimised (Supplementary Fig. S3). Stepwise elution with 30–50 mM imidazole resulted in the release of low molecular weight E. coli proteins, along with RsLEAP30-His6L and RsLEAP30-His6M. At 75 mM imidazole, RsLEAP30-His6M was eluted along with the initial release of the RsLEAP30-His6H form, which was more abundant. The highest yield of RsLEAP30-His6H was obtained at imidazole concentrations above 200 mM (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Based on these findings, an isocratic elution with 300 mM imidazole was chosen (Fig. 4a), ensuring high RsLEAP30-His6 recovery for all forms (Fig. 4b). In contrast to GBP-RsLEAP30, RsLEAP30-His6 was not detected in the IMAC flow-through (FT) fraction, indicating efficient column binding (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig S3). A subsequent size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) step was performed to further separate RsLEAP30-His6L, RsLEAP30-His6M, and RsLEAP30-His6H (Fig. 4c).

Purification of RsLEAP30-His6. (a) Representative IMAC chromatogram of RsLEAP30-His6 elution. The peak containing RsLEAP30-His6 was eluted with 300 mM imidazole. (b) SDS-PAGEanalysis of the collected fractions from the IMAC. The molecular weight (Mw) of the markers is indicated in kDa (MWP06, NIPPON Genetics, Düren, Germany); FT, flow-through. (c) Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) chromatogram of RsLEAP30-His6. (d) SDS-PAGE gel of the collected SEC fractions. The molecular weight (Mw) of the markers is indicated in kDa (MBS355494, San Diego, California). The red arrowheads indicate the bands corresponding to RsLEAP30-His6 forms.

Following SEC purification allowed separation of the fractions containing bands corresponding to the RsLEAP30-His6L, RsLEAP30-His6M and RsLEAP30-His6H forms (Fig. 4d). The fraction from the centre of the elution peak (fraction 31) showed two closely migrating bands, corresponding to RsLEAP30-His6H and RsLEAP30-His6M on SDS-PAGE.

To determine their Mw more precisely, SEC coupled with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) was performed. Analysis of fraction 31 revealed an average Mw of RsLEAP30-His6H and RsLEAP30-His6M of 24.64 ± 2.37 kDa, which deviates from the theoretical molecular weight of RsLEAP30-His6 (28 kDa).

To further characterise these two protein forms, a bottom-up proteomic approach with mass spectrometry (MS) detection was employed. Sequence identification confirmed almost complete sequence coverage of RsLEAP30-His6H (95%) and RsLEAP30-His6M (90%). Since both forms exhibited a sequence coverage of more than 90, fraction 31 was considered suitable for further analyses.

Overall, a total yield of approximately 0.5 mg of RsLEAP30-His6 (from fraction 31) per g of wet biomass was obtained with a final purity reaching 97% (Table 2).

Structural characterisation

The structure of RsLEAP30 (previously predicted to be localised in chloroplasts24) is key to understanding its function, so we used far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to analyse the contribution of secondary structure elements under various conditions.

We investigated the secondary structures of RsLEAP30-His6 under pH conditions ranging from 4 to 8, which, corresponds to different chloroplast subcompartments (with stromal pH ~ 8, luminal pH of 5 to 6, and the intermembrane space pH of 7.0 to 7.4), a dehydration-simulated conditions (2,2,2-trifluoroethanol; TFE) and a membrane-mimetic environment.

Under physiological (fully hydrated) conditions irrespective of the pH values tested, the RsLEAP30-His6 CD spectra showed a typical pattern of unstructured proteins with an intense minimum at 201 nm (Fig. 5a). Additionally, a slight minimum at 222 nm, characteristics of α-helices was observed. To calculate the contribution of the different secondary structures, we used DichroIDP26. Accordingly, 13%, 27%, 18%, and 42% of the RsLEAP30-His6 sequence was found in α-helical, β-turn, β-sheet, and disordered conformations, respectively.

TFE was used to simulate water removal during drying, since TFE induces desolvation of the protein backbone27. As a consequence of the gradual increasing of TFE amounts (particularly above 30%), CD spectra of RsLEAP30-His6 indicated a coil-to-helix transition, as evidenced by a shifting of the minimum at 200 nm towards higher wavelengths, finally forming two minima at 208 and 222 nm (Fig. 6b). This was supported by DichroIDP analysis, which showed an increase in α-helices and decrease in unstructured elements as the TFE content continued to increase, ultimately reaching 78% at TFE levels above 60% (Fig. 5b).

Comparative analysis of secondary and 3D structure predictions of RsLEAP30 and RsLEAP30-His6. (a) Distribution of secondary structure elements (α-helix, β-sheet and random coil) according to the five following predictors: (FELLS, PSIPRED, Phyre2, Jpred4, NetSurfP) (b) Predicted RsLEAP30 and RsLEAP30-His6 models, confidence and contribution of secondary structure elements (α-helix and random coil) according to AlphaFold3. pIDDT, per-residue measure of local confidence; pTM, predicted template modelling score.

In the presence of 1 mM SDS, CD spectra of RsLEAP30-His6 completely changed (Fig. 5c), revealing two minima at 208 and 220 nm, typical for α-helical structures, which was in accordance with DichroIDP calculations indicating that 72% of RsLEAP30-His6 sequence adopts an α-helical structure (Fig. 5c).

Given that we purified RsLEAP30 with a His6, we further examined whether this tag could influence the 3D structure of native RsLEAP30 using in silico analysis (Fig. 6). According to five commonly used secondary structure predictors, only minor differences in proportion of α-helical compared to random coils between RsLEAP30-His6 and RsLEAP30 were observed: RsLEAP30 exhibited 81% α-helix, 1% β-sheet, 18% random coil, while RsLEAP30-His6 showed 79% α-helix, 1% β-sheet, 21% random coil (Fig. 6a). Disorder predictors indicated a consistent proportion of disorder for both, RsLEAP30 and RsLEAP30-His6, averaging 83% (Supplementary Fig. S4). In addition, very similar 3D structures of RsLEAP30-His6 and RsLEAP30 were generated by AlphaFold3, although per-residue measure of local confidence (pIDDT) and predicted template modelling (pTM) score values indicated low confidence levels.

Discussion

As a tertiary relict, R. serbica serves as an excellent model for studying vegetative desiccation tolerance, a phenomenon that is considered a pivotal step in the evolution of early land plants7. LEA proteins are a hallmark of vegetative desiccation tolerance. However, despite various proposed functions, their precise role remains unclear8,23.

In this study, we report for the first time the recombinant expression of a LEA protein from the dicotyledonous, homoiochlorophyllous resurrection plant R. serbica using a bacterial expression system. RsLEAP30 was selected as it was significantly induced during desiccation and predicted to be localized in the chloroplasts, indicating that it could be involved in the protection of thylakoids, photosynthetic pigments, and associated proteins during stress.

Initially, we aimed to achieve high-yielding, tag-free RsLEAP30 expression in the E. coli BL21(DE3) system, given its simplicity, rapid growth, ease of genetic modification, and cost-effectiveness28. However, this system presents certain challenges, including the formation of inclusion bodies and protein degradation29. Additionally, recombinant production of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) is inherently difficult due to their structural plasticity and susceptibility to proteolysis and aggregation29. The presence of disordered and hydrophobic regions predisposes these proteins to the formation of inclusion bodies29,30.

To overcome these limitations, we integrated a fusion partner GBP in our initial approach, as it has been shown to reduce the formation of the inclusion bodies and increase the stability, solubility, and yield of the target proteins30,31. Consequently, we successfully obtained GBP-RsLEAP30 with an estimated molecular weight (Mw) of 46 kDa, achieving a yield of ~ 13% and a purity of ~ 91% (Fig. 1). The observed discrepancy in Mw, caused by retarded electrophoretic mobility compared to the theoretical Mw of GBP-RsLEAP30 (37 kDa), is more likely a result of the high content of negatively charged amino acids (Glu 8%, Asp 8.3%), which reduces SDS binding efficiency, as previously reported32. In addition, the disordered and extended structures of the examined LEA protein (Figs. 5, 6) may account for the observed differences in Mw (20% higher in the case of GBP-RsLEAP30). For instance, two proteins featuring intrinsically disordered regions, NTAIL and PNT, exhibited an apparent Mw that was 33–36% higher when analysed via SDS-PAGE compared to their theoretical Mw33.

Despite numerous attempts to cleave the fusion partner with TEV protease under a variety of reaction conditions, we were unable to obtain native RsLEAP30. TEV protease is widely used for the cleavage of fusion partners due to its high specificity, activity across diverse conditions, and commercial availability. Since digestion of GBP-RsLEAP30 did not occur under optimal conditions for TEV proteolytic activity (despite successful cleavage of other TEV-site-containing recombinant proteins under the same conditions), we propose that GBP-RsLEAP30 adopts a conformation in which the recognition site (ENLYFQ/G) at the N-terminus is inaccessible, thereby preventing TEV binding. A similar explanation can be given for the weak interaction of GBP-RsLEAP30 with Ni-based resin during the first purification step using IMAC, as the His8 tag is also located in the N-terminal region, like GBP. This suggests that the N-terminus of GBP-RsLEAP30 may be structurally buried inside the protein.

Since TEV protease activity is not affected by certain detergents such as Triton X-100, Tween-20, and DDM34, we attempted to induce conformational changes in GBP-RsLEAP30 to expose the TEV recognition site, but these efforts were unsuccessful.

Given that RsLEAP30 is a highly polar protein, with 28% polar and 34% charged amino acids and a GRAVY index of − 1.0024, the absence of a fusion partner is unlikely to affect its solubility in E. coli. Indeed, RsLEAP30-His6 was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells at 37 °C for 3 h as a soluble protein (Fig. 3) and subsequently, it was purified using IMAC and SEC, as shown in Fig. 4. Similarly, maximum expression of the cytosolic dehydrin-like LEA protein, Dsp1635 from another dicot, homoiochlorophyllous resurrection plant species Craterostigma plantagineum, in E. coli using the T7 system was observed 3.5 h after induction36. RsLEAP30-His6 exhibited a lower yield than GBP-RsLEAP30, due to the additional purification step (Tables 1 and 2), while they achieved similar purities at the end (91% and 97%) which is comparable with the recombinant Dsp16 final purity of 95%36.

Recombinant DNA technology has already been successfully employed to produce LEA proteins in various organisms. Besides the mentioned Dsp16 from C. plantagineum36, six LEA proteins from the monocot poikilochlorophyllous resurrection species Xerophyta schlechteri were successfully expressed in E. coli37. Similarly, three members of the LEA4 protein family were expressed in E. coli to generate specific antibodies for functional analyses in Arabidopsis mutants38. Eleven LEA proteins from Dendrobium officinale were also expressed in E. coli to investigate their roles in stress tolerance39. In addition, LEA11 and LEA25 from Arabidopsis were produced in E. coli to study their potential interactions with membranes18. Recently, two recombinant LEA proteins from tardigrades and nematodes were expressed in E. coli and purified by the same two-step chromatographic methods (IMAC and SEC) employed in our study40. However, none of these reports provide quantitative data on yield and purity.

The integrity of RsLEAP30-His6H should be regarded as tentative, since we did not employ MS to confirm its Mw. Although MS analysis of RsLEAP30-His6H confirmed a sequence identity of over 95%, its experimentally determined Mw derived from electrophoretic mobility, was approximately 10% higher than the theoretically expected value (Figs. 3,4). This discrepancy can be attributed to the conformational heterogeneity and altered SDS binding (as discussed above). On the other hand, Mw as determined by SEC-MALS was slightly underestimated. Since SEC separates molecules based on hydrodynamic radius rather than Mw, this discrepancy can be attributed to a significant contribution of unstructured regions in RsLEAP30-His6 (Fig. 5). Proteins containing disordered regions often adopt an elongated conformation, leading to later elution and an underestimated Mw by SEC-MALS41.

24. To estimate the effect of His6 tag on native RsLEAP30 conformation we computed the proportion of secondary structure elements in RsLEAP30-His6, and observed that the His6 tag had a minimal effect on the secondary structure of RsLEAP30 (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. S4). Crystallographic structural analysis demonstrated that various His-tags generally have no significant effect on the structure of the native protein42, particularly in proteins averaging 350 amino acids in length with tags comprising approximately 10 amino acids. Moreover, it is very rare for His tags to adopt an ordered structure; they are typically disordered42.

The structural models of RsLEAP30 generated by AlphaFold3, indicated a disordered N-terminal region, while the segment spanning residues ~ 60–250 was predominantly α-helical irrespective of the His6 tag. These results must be interpreted with caution, due to AlphaFold’s biased prediction towards helical structures and its low confidence in modeling disordered regions43,44. As CD measurements showed increase of helicity of RsLEAP30-His6 under higher concentrations of SDS and TFE (Fig. 5), we hypothesised that the residues ~ 60–250 might be predisposed to adopt α-helical structures under such conditions. Furthermore, according to HeliQuest web server predictions45, this region, if adopts helical structure, is expected to fold mainly into A-type α-helices, containing distinct positive, negative, and/or hydrophobic faces24.

RsLEAP30-His6 was predicted to be localised in chloroplasts24, where the stromal pH is ~ 8, the luminal pH is from 5 to 6, and the pH of the intermembrane space is 7.0–7.4. Since conformational changes in IDPs can be triggered by environmental factors such as pH46, we examined the secondary structure of RsLEAP30-His6 in a pH range of 4–8 to better understand the functional properties of these stress-associated proteins. Interestingly, CD spectroscopy revealed no significant changes in the secondary structure in this pH range, suggesting that RsLEAP30-His6 is largely disordered (Fig. 5a). Similarly, recombinant dehydrin-related Dsp16 from C. plantagineum showed a strong minimum at 198 nm in the native state, which indicates a largely random conformation36. Also, recombinantly produced LEA proteins from the monocot poikilochlorophyllous resurrection species X. schlechteri also exhibited a predominantly disordered nature37.

TFE induces protein folding by promoting desolvation of the protein backbone27 and facilitates the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds at the expense of solvent/water-backbone hydrogen bonds, which can be physically and conceptually related to the effects of drying. A molecular dynamics simulation study by Mehrnejad et al.47 demonstrated that TFE molecules remove alternative hydrogen bonding partners and create a low dielectric environment, both of which favour the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds. The transition of RsLEAP30-His6 structure from predominantly unstructured to mostly α-helical conformation upon an increase of TFE content (Fig. 5b) models its proposed behavior during desiccation18,27. A continuous increase in α-helicity with increasing TFE content and decreasing water potential was observed in the case of intrinsically disordered LEA4 protein family members from Arabidopsis thaliana48 and in the case of Dsp16 from C. plantagineum36. Therefore, we suggest that RsLEAP30 adopts mostly α-helical structures during leaf desiccation, enabling its interaction with other proteins and membranes.

Similarly, under 1 mM SDS (and 10 mM SDS, that corresponds to the critical micelle concentration at 25 °C—data not shown), RsLEAP30-His6 undergoes a disordered-to-ordered transition (folding into α-helical structures, Fig. 5c). We propose that this dual structure of RsLEAP30 may be essential for its role in protecting membranes, particularly thylakoids in chloroplasts, and for maintaining membrane integrity under desiccation conditions. The α-helical regions of RsLEAP30 may interact electrostatically with the negatively charged phosphate groups of phospholipids via their positively charged side, while their hydrophobic side may interact with the fatty acid tails of membrane lipids.

However, the inner envelope membrane of chloroplasts, etioplasts, and proplastids, as well as the thylakoid membrane, mainly consists of neutral galactolipids and only 8–10% phospholipids49. This composition suggests that interaction with membranes may be a minor role of RsLEAP30, while its interaction (via its A-type α-helices with alternating positive and negative sides) with desiccation-sensitive proteins within chloroplasts, particularly components of the photosynthetic electron transport chain, may be more important. This is particularly important since R. serbica, as a homoiochlorophyllous species, can rapidly resume photosynthesis after rehydration. Moreover, the presence of IDRs may allow RsLEAP30-His6 to remain in a predominantly random coil conformation under normal physiological conditions, while adopting an α-helical structure during desiccation. Indeed, members of the LEA4 protein family in Arabidopsis have been shown to adopt an α-helical structure under water-limiting conditions, thereby preventing the inactivation and aggregation of lactate dehydrogenase in vitro48. Furthermore, recombinant LEA proteins from the LEA1 family in X. schlechteri were found to adopt a fully α-helical conformation in hydrophobic acetonitrile solutions37.

Conclusion

Our study presents the first report on the recombinant production and structural characterisation of a desiccation-induced LEA protein from the ancient resurrection plant R. serbica. We propose that a disorder-to-order transition of RsLEAP30, a chloroplastic member of the LEA4 protein family, plays a crucial role in the rapid recovery of photosynthetic components upon rehydration. Further investigation of these mechanisms and elucidation of the full functional repertoire of LEA proteins in planta would provide valuable insights in desiccation tolerance mechanisms in resurrection plants. Understanding these processes will contribute to future application in agricultural interventions to boost drought tolerance in crops.

Methods

Vector, construct and host strain

The expression plasmid pET24a(+) (Supplementary Fig. 5a) containing the His-tagged GBP-RsLEAP30 construct was sourced from Synbio Technologies (Monmouth Junction, USA), with kanamycin resistance. The construct featured a His8 tag followed by a fusion partner, chain A of the immunoglobulin G-binding protein (GBP) from Streptococcus sp., followed by an asparagine polylinker (Supplementary Fig. S5b). The C-terminus of the construct contained a Tobacco Etch Virus (TEV) protease recognition site and the RsLEAP30 gene. The complete construct consisted of His8-tag-GBP–polylinker–TEV protease site–RsLEAP30, with NdeI and XhoI restriction sites (Supplementary Fig. S5b).

E. coli strains DH5α and BL21(DE3) were used for plasmid amplification and protein expression, respectively. After amplification of the plasmid in DH5α, the plasmid was validated by sequencing at the Macrogen Europe sequencing facility (Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Subcloning of RsLEAP30

The vector containing the RsLEAP30 gene with a His tag at the C-terminus (Supplementary Fig. S5c) was derived from the GBP-RsLEAP30 construct. Primers were designed for amplification: the forward primer contained a NdeI restriction site (5’-CATATGGCGGCGATGTTCGTTGCAAAAACGACCGTGTTAAATTTGTC-3’), and the reverse primer contained an XhoI restriction site, a stop codon, and the His6 tag (5’-GCAGAGTCTAAACGGCATCACCATCATCACCACTGAATTCTCGAG-3’). The RsLEAP30 gene was amplified by PCR from the ordered plasmid with the mentioned primers. The PCR product was purified using the GeneJET PCR Purification Kit (K0701, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and inserted into a TOPO vector carrying ampicillin and kanamycin resistance markers (11,543,147, Invitrogen, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Calcium-competent E. coli DH5α cells were transformed by heat shock and plated on LB agar supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg mL−1), ampicillin (100 μg mL−1), IPTG (1 mM), and xGal (20 μg mL−1). Positive, white, colonies were identified by colony PCR and used for plasmid isolation. To ensure proper insertion, empty pET24a(+) and TOPO vectors containing the insert were digested with XhoI, NdeI, and HindIII. An additional HindIII digestion confirmed that the insert was cloned. After restriction digestion, the mixtures were purified using the GeneJET PCR Purification Kit, and ligation was performed using a vector:insert ratio of 1:2.5, polyethylene glycol, and T4 ligase according to the manufacturer’s protocol (EL0011, Thermo Fisher Scientific). After incubation at 23 °C for 1 h, competent DH5α cells were transformed and plated on LB agar containing kanamycin (50 μg mL−1). The presence of the correct insert was confirmed by sequencing plasmids isolated from individual colonies using the GeneJET Plasmid Miniprep Kit (K0503, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and T7 primers at the Macrogen Europe sequencing facility (Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Small-scale RsLEA protein production

For protein expression, calcium competent E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with the pET24a(+) vector containing the construct. A single bacterial colony containing the transformed plasmid was cultured overnight in 10 mL of Luria–Bertani medium (LB) supplemented with 100 μg mL−1 of kanamycin and 0.25% glycerol at 37 °C and shaken at 200 rpm.

This overnight culture was then diluted 1:10 into fresh LB supplemented with the 100 μg mL−1 kanamycin and 0.25% glycerol, and grown at 37 °C until the optical density (OD600) reached 0.7. An aliquot of non-induced culture was saved as a control, while gene expression was induced using 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Induced cultures were incubated at 25 °C, 30 °C, and 37 °C and shaken on an orbital shaker (200 rpm). Aliquots of induced and non-induced broths were collected at various time points (30 min, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 24 h).

For the optimisation of the expression, cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 g for 5 min, resuspended in 180 μL of Laemmli buffer, and incubated overnight at 25 °C. The samples were then centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min, and the supernatants were analysed by SDS-PAGE on 12% gels as described by Vidović et al. (2016)50.

Protein concentration

Protein concentrations of the aliquots were determined using the Bradford assay (1976)51 with a temperature-controlled spectrophotometer (Infinite M Nano +, TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland) at 595 nm, with measurements performed in triplicate in 96-well microplates.

SDS-PAGE and western blotting

Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on 12% gels and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250. For western blotting, proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes soaked in Tris–Glycine buffer (pH 8.3) containing 20% methanol, using a semi-dry transfer method at 1.5 mA cm−2 for 45 min. The blotting was done using the SNAP i.d.® 2.0 Protein Detection System for western blotting (Millipore, Burlington Massachusetts). After blocking with 0.5% non-fat dry milk in TBST (Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20), the membranes were incubated with primary mouse monoclonal anti-His antibodies (Takara Bio, 631,212) diluted 1: 5,000 in TBST with 0.5% non-fat dry milk for 1 h. Following four washes in TBST, membranes were incubated with a secondary anti-mouse IgG antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP; Sigma-Aldrich, A9044) diluted 1: 80,000 for 1 h. After two additional washes in TBST, proteins with His tags were detected using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore, Burlington Massachusetts) and visualised with a ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Protein band quantification on gel was performed using ImageJ52.

Testing the solubility of GBP-RsLEAP30 and RsLEAP30-His6 recombinant proteins

To assess the solubility of recombinant GBP-RsLEAP30 and RsLEAP30-His6 proteins, E. coli cell pellets obtained after incubation under previously optimised conditions, were resuspended in 100 μL of 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8) and lysed by sonication for 5 s at 10 microns of probe amplitude (Soniprep 150, MSE Crowley, London, UK) on ice. The sonication was repeated three times. The lysates were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the pellets and supernatants were separated. Both fractions were resuspended in 180 μL Laemmli buffer, incubated overnight at 25 °C, and centrifuged again at 15,000 g for 10 min. Equal volumes of the supernatants were analysed by SDS-PAGE.

Large-scale GBP-RsLEAP30 and RsLEAP30-His6 protein production

To scale up protein production, the starter overnight cultures of E. coli BL21(DE3) containing the relevant construct were used to inoculate 400 mL of LB medium supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg mL−1) in 2-L flasks and shaken at 200 rpm under previously optimised temperature conditions. At an OD600 of 0.7, gene expression was induced using 1 mM IPTG under optimal conditions. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 g, resuspended in lysis buffer (1:7, w/v), consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8) and cOmplete EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), and lysed via sonication (12 cycles of 20 s on ice, followed by 20 s pauses). The cell debris was then removed by centrifugation at 15,000 g for 20 min at 4 °C.

Protein purification

The lysate was filtered through 0.45 μm and 0.22 μm filters before being loaded onto 5 mL HisTrap HP column filled with nickel-based resin (Cytiva, Marlborough, Massachusetts) using the ÄKTA Go™ protein purification system (Cytiva, Marlborough, Massachusetts). A total of 50 mL of filtered lysate was applied to the column pre-equilibrated with 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.00). The target RsLEAP were eluted using a stepwise imidazole gradient (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 75, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 mM). Following an optimised elution profile, 2-mL fractions were collected at a flow rate of 2 mL min−1, with absorbance monitored at 280 nm. Imidazole was removed using Amicon® Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units (10 kDa cut-off, Merck). Eluted fractions were analysed by SDS-PAGE. Chosen fractions were pooled, concentrated, snap-frozen in aliquots, and stored at − 80 °C until use. Further purification was done using a HiLoad Superdex 75 prep grade resin packed into a 16/100 (17,104,402, Cytiva, Marlborough, Massachusetts) column size exclusion chromatography (SEC). The resin was pre-equilibrated in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), and protein separation based on molecular weight (Mw) was achieved using the same buffer at a flow rate of 2 mL min−1. The fractions collected were dialyzed against MilliQ water, analysed by SDS-PAGE, lyophilised, and stored at − 80 °C until use. All chromatographic purifications were repeated in at least five independent replicates, with representative chromatograms shown.

Digestion of GBP-RsLEAP30 by TEV

To obtain Gly-RsLEAP30 from the GBP-RsLEAP30 fusion protein, TEV protease (Z03030, GenScript, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA) was used. Following the manufacturer’s instructions, one unit of TEV protease is expected to cleave over 85% of 3 μg of protein in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) at 30 °C within 1 h.

Size exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS)

Mw of purified RsLEAP30-His6 was determined using static light scattering with a Dawn Heleos II MALS recorder (Wyatt Technology Europe), coupled to an HPLC system (Alliance e2695, Milford, Massachusetts, USA). Selected fractions obtained from SEC were filtered through 0.1 µm centrifugal filter units (Millipore, Burlington Massachusetts, USA), and 50 µL of each sample was injected onto a Superdex 75 Increase 10/300 SEC column (Cytiva, Marlborough, Massachusetts). The proteins were eluted with 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5). Mw calculations were performed using ASTRA 6 software (Wyatt Technology Europe, Dernbach, Germany), following the manufacturer’s guidelines.

In-gel digestion and MS analysis

Protein bands from gels (1 × 1 mm) were cut with a clean scalpel and transferred to tubes. Gel pieces were destained with 10% acetic acid and 40% ethanol, and than with a 1:1 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate and acetonitrile. After that, reduction with 10 mM DTT and alkylation with 55 mM iodoacetamide were performed. Following the digestion with trypsin (100 ng) overnight at 37 °C, proteins were extracted with 0.5% trifluoroacetic acid and 50% acetonitrile and dried. Dried samples were resuspended in 2% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid in water, and injected into a Q Exactive MS coupled to a Vanquish Neo high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The samples were loaded on a PepMapTM 100 C18 with a length of 150 mm, an internal diameter 0.1 mm, and a particle size of 5 μm (Thermo Fisher Scientific, cat. number 164199) for 5 min with 0.1% formic acid in water. Two buffer systems were used to elute the peptides: 0.1% formic acid in water (buffer A) and 0.1% formic acid in 80% acetonitrile (buffer B). Peptide separation was performed using a gradient : step1: 2.0% to 2.0% in 1.0 min, step 2: from 2.0% to 37.5% in 41.0 min, step 3: from 37.5% to 100.0% in 2.0 min, step 4: from 100.0% to 100.0% in 10.0 min, step 5: from 100.0% to 2.0% in 1.0 min, and step 6: from 2.0% to 2.0% in 5.0 min, of buffer B. The database search was performed using X!Tandem (version 201.2.1.4)53.

CD spectroscopy

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded using a Chirascan CD spectrometer (Applied Photophysics, Leatherhead, UK), equipped with a Peltier temperature controller. To prepare the samples, the buffer in the purest RsLEAP30-His6 fractions was exchanged for MilliQ water. The samples were then freeze-dried and resuspended in MilliQ water to a concentration of 178 μM, which served as the stock solution. For CD measurements, protein solutions were prepared by diluting the stock solution in a 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 4.0–8.0) to achieve a final concentration of 5 μM. Spectral data were recorded from 240 to 190 nm in 1 mm quartz cuvettes (Hellma, Mühlheim, Germany) at 25 °C using a 1 nm step size, 1 nm/s scanning speed, 1 s sampling intervals, and 1 nm band width. The final spectra represent the average of three scans. The secondary structure content of RsLEAP30-His6 was estimated using DichroIDP software26.

Structural modelling of RsLEAP30 and RsLEAP30-His6

The secondary structure prediction of RsLEAP30 and RsLEAP30-His6 was performed using the following predictors: FELLS54, PSIPRED55, JPred456, Phyre257, and NetSurfP58. The disorder prediction was performed via specialised disorder predictors: the FELLS54, PONDR59, IUPred360 and PrDOS61. Finally, the protein 3D structures of RsLEAP30 and RsLEAP30-His6 were predicted and visualised using AlphaFold362. Default settings were used for all predictions.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files. All other results (e.g. original images of gels and membranes) are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Oliver, M. J. et al. Desiccation tolerance: Avoiding cellular damage during drying and rehydration. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 71, 435–460 (2020).

Bowles, A. M., Paps, J. & Bechtold, U. Evolutionary origins of drought tolerance in spermatophytes. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 655924 (2021).

Farrant, J. M. Mechanisms of desiccation tolerance in angiosperm resurrection plants. In Plant Desiccation Tolerance (eds Jenks, M. A. & Wood, A. J.) 51–90 (Wiley, 2007).

Farrant, J. M. & Hilhorst, H. W. M. What is dry? Exploring metabolism and molecular mobility at extremely low water contents. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 1507–1510 (2021).

Rakić, T. et al. Resurrection plants of the genus Ramonda: Prospective survival strategies—Unlock further capacity of adaptation, or embark on the path of evolution?. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 550 (2014).

Georgieva, K. et al. Photosynthetic activity of homoiochlorophyllous desiccation tolerant plant Haberlea rhodopensis during dehydration and rehydration. Planta 225, 955–964 (2007).

Toldi, O., Tuba, Z. & Scott, P. Vegetative desiccation tolerance: Is it a gold mine for bioengineering crops?. Plant Sci. 176, 187–199 (2009).

Olvera-Carrillo, Y., Reyes, J. L. & Covarrubias, A. A. Late embryogenesis abundant proteins: Versatile players in the plant adaptation to water-limiting environments. Plant Signal Behav. 6, 586–589 (2011).

Dure, L. 3rd., Greenway, S. C. & Galau, G. A. Developmental biochemistry of cottonseed embryogenesis and germination XIV Changing mRNA populations as shown by in vitro and in vivo protein synthesis. Biochemistry 20, 4162–4168 (1981).

Battaglia, M., Olvera-Carrillo, Y., Garciarrubio, A., Campos, F. & Covarrubias, A. A. The enigmatic LEA proteins and other hydrophilins. Plant Physiol. 148, 6–24 (2008).

Hundertmark, M. & Hincha, D. K. LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) proteins and their encoding genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genom. 9, 118 (2008).

Close, T. J. & Lammers, P. J. An osmotic stress protein of cyanobacteria is immunologically related to plant dehydrins. Plant Physiol. 101, 773–779 (1993).

Amara, I. et al. Insights into late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins in plants: From structure to functions. Am. J. Plant Sci. 5, 3440–3455 (2014).

Uversky, V. N. Protein intrinsic disorder and structure-function continuum. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 166, 1–17 (2019).

Hincha, D. K. & Thalhammer, A. LEA proteins: IDPs with versatile functions in cellular dehydration tolerance. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 40, 1000–1003 (2012).

Gechev, T., Lyall, R., Petrov, V. & Bartels, D. Systems biology of resurrection plants. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 78, 6365–6394 (2021).

Chakrabortee, S. et al. Intrinsically disordered proteins as molecular shields. Mol. Biosyst. 8, 210–219 (2012).

Bremer, A., Wolff, M., Thalhammer, A. & Hincha, D. K. Folding of intrinsically disordered plant LEA proteins is driven by glycerol-induced crowding and the presence of membranes. FEBS J. 284, 919–936 (2017).

Hoekstra, F. A., Golovina, E. A. & Buitink, J. Mechanisms of plant desiccation tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 9, 431–438 (2001).

Cuevas-Velazquez, C. L. & Dinneny, J. R. Organization out of disorder: Liquid-liquid phase separation in plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 45, 68–74 (2018).

Belott, C., Janis, B. & Menze, M. A. Liquid-liquid phase separation promotes animal desiccation tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 117, 27676–27684 (2020).

Watson, J. L. et al. Macromolecular condensation buffers intracellular water potential. Nature 623, 842–852 (2023).

Dirk, L. M. A. et al. Late embryogenesis abundant protein-client protein interactions. Plants 9, 814 (2020).

Pantelić, A., Stevanović, S., Komić, S. M., Kilibarda, N. & Vidović, M. In silico characterisation of the Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) protein families and their role in desiccation tolerance in Ramonda serbica Panc. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 3547 (2022).

Vidović, M. et al. Desiccation tolerance in Ramonda serbica Panc.: an integrative transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolite and photosynthetic study. Plants 11, 1199 (2022).

Miles, A. J., Drew, E. D. & Wallace, B. A. DichroIDP: a method for analyses of intrinsically disordered proteins using circular dichroism spectroscopy. Commun. Biol. 6, 823 (2023).

Kentsis, A. & Sosnick, T. R. Trifluoroethanol promotes helix formation by destabilizing backbone exposure: desolvation rather than native hydrogen bonding defines the kinetic pathway of dimeric coiled coil folding. Biochemistry 37, 14613–14622 (1998).

Rosano, G. L. & Ceccarelli, E. A. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: Advances and challenges. Front. Microbiol. 5, 172 (2014).

Bhatwa, A. et al. Challenges associated with the formation of recombinant protein inclusion bodies in Escherichia coli and strategies to address them for industrial applications. Front. Bioeng Biotechnol. 9, 630551 (2021).

Rosano, G. L., Morales, E. S. & Ceccarelli, E. A. New tools for recombinant protein production in Escherichia coli: A 5-year update. Protein Sci. 28, 1412–1422 (2019).

Tepap, C. Z., Anissi, J. & Bounou, S. Recent strategies to achieve high production yield of recombinant protein: A review. J. Cell Biotechnol. 9, 25–37 (2023).

Kaufmann, E., Geisler, N. & Weber, K. SDS-PAGE strongly overestimates the molecular masses of the neurofilament proteins. FEBS Lett. 170, 81–84 (1984).

Sambi, I., Gatti-Lafranconi, P., Longhi, S. & Lotti, M. How disorder influences order and vice versa – mutual effects in fusion proteins containing an intrinsically disordered and a globular protein. FEBS J. 277, 4438–4451 (2010).

Sun, C. et al. Tobacco etch virus protease retains its activity in various buffers and in the presence of diverse additives. Protein Expr. Purif. 82, 226–231 (2012).

Schneider, K. et al. Desiccation leads to the rapid accumulation of both cytosolic and chloroplastic proteins in the resurrection plant Craterostigma plantagineum Hochst. Planta 189, 120–131 (1993).

Lisse, T., Bartels, D., Kalbitzer, H. R. & Jaenicke, R. The recombinant dehydrin-like desiccation stress protein from the resurrection plant Craterostigma plantagineum displays no defined three-dimensional structure in its native state. Biol. Chem. 377, 555–561 (1999).

Artur, M. A. S. et al. Structural plasticity of intrinsically disordered LEA proteins from Xerophyta schlechteri provides protection in vitro and in vivo. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1272 (2019).

Olvera-Carrillo, Y., Campos, F., Reyes, J. L., Garciarrubio, A. & Covarrubias, A. A. Functional analysis of the group 4 late embryogenesis abundant proteins reveals their relevance in the adaptive response during water deficit in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 154, 373–390 (2010).

Ling, H., Zeng, X. & Guo, S. Functional insights into the Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) protein family from Dendrobium officinale (Orchidaceae) using an Escherichia coli system. Sci. Rep. 6, 39693 (2016).

Abe, K. M., Li, G., He, Q., Grant, T. & Lim, C. J. Small LEA proteins mitigate air-water interface damage to fragile cryo-EM samples during plunge freezing. Nat. Commun. 15, 7705 (2024).

Smith, K. P. et al. SEC-SAXS/MC ensemble structural studies of the microtubule binding protein Cdt1 show monomeric, folded-over conformations. Cytoskeleton 82, 372–387 (2025).

Carson, M., Johnson, D. H., McDonald, H., Brouillette, C. & DeLucas, L. J. His-tag impact on structure. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 63, 295–301 (2007).

Agarwal, V. & McShan, A. C. The power and pitfalls of AlphaFold2 for structure prediction beyond rigid globular proteins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 20, 950–959 (2024).

Saldaño, T. et al. Impact of protein conformational diversity on AlphaFold predictions. Bioinformatics 38(10), 2742–2748 (2022).

Gautier, R., Douguet, D., Antonny, B. & Drin, G. HELIQUEST: A server to screen sequences with specific alpha-helical properties. Bioinformatics 24, 2101–2102 (2008).

Uversky, V. N. Intrinsically disordered proteins and their environment: effects of strong denaturants, temperature, pH, counter ions, membranes, binding partners, osmolytes, and macromolecular crowding. Protein J. 28, 305–325 (2009).

Mehrnejad, F., Naderi-Manesh, H. & Ranjbar, B. The structural properties of magainin in water, TFE/water, and aqueous urea solutions: Molecular dynamics simulations. Proteins 67, 931–940 (2007).

Cuevas-Velazquez, C. L., Saab-Rincón, G., Reyes, J. L. & Covarrubias, A. A. The unstructured N-terminal region of Arabidopsis group 4 late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins is required for folding and for chaperone-like activity under water deficit. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 10893–10903 (2016).

Candat, A. et al. The ubiquitous distribution of late embryogenesis abundant proteins across cell compartments in Arabidopsis offers tailored protection against abiotic stress. Plant Cell 26, 148–166 (2014).

Vidović, M. et al. Characterisation of antioxidants in photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic leaf tissues of variegated Pelargonium zonale plants. Plant Biol. 18, 669–680 (2016).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 7(72), 248–254 (1976).

Schneider, C., Rasband, W. & Eliceiri, K. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 671–675 (2012).

Craig, R. & Beavis, R. C. TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics 20, 1466–1467 (2004).

Piovesan, D., Walsh, I., Minervini, G. & Tosatto, S. C. E. FELLS: Fast Estimator of Latent Local Structure. Bioinformatics 33, 1889–1891 (2017).

McGuffin, L. J., Bryson, K. & Jones, D. T. The PSIPRED protein structure prediction server. Bioinformatics 16, 404–405 (2000).

Drozdetskiy, A., Cole, C., Procter, J. & Barton, G. J. Pred4: a protein secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W389–W394 (2015).

Powell, H. R., Islam, S. A., David, A. & Sternberg, M. J. Phyre2.2: A community resource for template-based protein structure prediction. J. Mol. Biol. 437, 168960 (2025).

Høie, M. H. et al. NetSurfP-3.0: Accurate and fast prediction of protein structural features by protein language models and deep learning. Nucleic Acids Res. 50(W1), W510–W515 (2022).

Xue, B., Dunbrack, R. L., Williams, R. W., Dunker, A. K. & Uversky, V. N. PONDR-FIT: A meta-predictor of intrinsically disordered amino acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 996–1010 (2010).

Erdős, G., Pajkos, M. & Dosztányi, Z. IUPred3: prediction of protein disorder enhanced with unambiguous experimental annotation and visualization of evolutionary conservation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W297–W303 (2021).

Ishida, T. & Kinoshita, K. PrDOS: prediction of disordered protein regions from amino acid sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W460–W464 (2007).

Abramson, J. et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 630, 493–500 (2024).

Acknowledgements

Ana Pantelić wishes to acknowledge the support of COST Action CA21160 for approving a Short-Term Scientific Mission in Ljubljana. We thank Dr Mira Milisavljević and Dr Milorad Kojić for their useful discussions on protein expression and Dr Miloš Rokić for his suggestions regarding the RsLEAP30 purification.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia–RS (PROMIS project LEAPSyn-SCI, grant no. 6039663) and by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (Contract No. 451–03-136/2025–03/200042).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. A.P. was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, investigation, conducting experiments, data analysis, preparation of the original draft, reviewing, and editing. M.V. was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, data analysis, preparation of the original draft, reviewing, and editing. T.I. was responsible for methodology, investigation, conducting experiments, and preparation of the original draft. D.M. was responsible for methodology, conducting experiments, and data analysis. H.G. and J.R. were responsible for methodology, reviewing, and editing. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent to publish

All authors consent to the publication of this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pantelić, A., Ilina, T., Milić, D. et al. Structural flexibility of a recombinant intrinsically disordered LEA protein from Ramonda serbica. Sci Rep 15, 34808 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18648-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-18648-w