Abstract

The paper presents a new conception of applying a system configuration of two machines supplied by a five-phase inverter with a common leg. The space vector pulse width modulation (SVPWM) technique was used for the given configuration of the dual generator system to ensure a dual three-phase output from a single five-phase inverter. Supplying two three-phase doubly-fed induction generators (DFIG) with a five-phase voltage source inverter (VSI) is not new. Two- and multi-motor drive systems are widely used in industry. Electric vehicles (EVs) and traction systems are the most popular application areas. However, there are no solutions for generator systems. The main idea of this paper is to apply a dedicated SVPWM technique for two-motor systems as an alternative to a two-generator system. The output voltages of the five-phase inverter supplying two three-phase rotors for both generators can be generated independently, with different frequencies and amplitudes. The concept of independent control of two generators using the field-oriented control method was verified in an experimental system for 2kW generators. Tests confirmed the usefulness of the proposed solution, with the ability to independently control each generator, as well as the effectiveness of the modulation strategy used to generate high-quality energy with low voltage harmonics. The THD values for the voltages of both generators did not exceed 5% in any of the cases considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Counter-rotating rotor systems with two propellers are used as solutions in many areas, such as pumped hydro storage system1 or ocean wave energy converters2, and wind energy harvesting systems3,4,5,6. The counter-rotating propellers have several advantages, such as removal torque reversal and gyroscopic torque, resulting in increased maneuverability, wake straightening, and the second propeller recovering the energy lost in the fluid’s rotation flow rate. A promising area of application of this type of solution is wind energy. The commercial wind power industry’s most common turbine design solutions include single-rotor designs. According to Betz’s theory, the maximum power that can be extracted from the wind by a single-rotor turbine is about 59% of the total available wind energy. In practice, the energy in the wake behind a single rotor can still be useful. Installing a second rotor in the wake can further extract part of this useful energy. Simultaneously, the maximum energy that two rotors of the same diameter can extract is increased to 64% of the available energy, the theoretical limit for two rotors7. A counter-rotating wind turbine (CRWT) system consists of two rotors separated by an appropriate distance depending on the aerodynamical features of both turbines. One of the rotors rotates in a counter-clockwise direction, and the other in a clockwise direction. As shown in Fig. 1 in CRWT designs, there are two configurations. In the first case, the rotors are placed right behind each other, creating an upstream and downstream rotor configuration. In the second case, the rotors are placed at a certain distance. In both configurations, it is necessary to use two electric generators for each turbine separately or one specially designed generator for both.

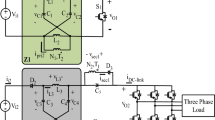

In the classic approach, the configuration of a system of two cooperating three-phase doubly-fed generators requires two separate three-phase inverters connected by a common DC-link circuit powered by a grid-side inverter. This topology allows for bidirectional energy flow between the machine part of the system and the power grid, which is important because the directions of power flow depend on the operating points of individual generators. Such a system can be connected to the power grid or work in a stand-alone grid configuration. The considered two-generator system powered by a voltage source inverter (VSI) topology with five leg eliminates two switches compared to the standard VSI configuration with two independent three-phase inverters. This structure offers a simplified configuration of the machine inverter and the ability to control two three-phase generators using only one digital signal processor (DSP)8,9.

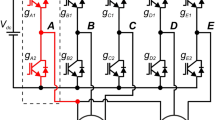

A five-leg VSI feeds two three-phase doubly-fed induction generators, as shown in Fig. 2. The two generators share the output leg of inverter A with rotor phases \(a_{1}\) and \(a_{2}\). Inverter branches B and C are connected directly to rotor phases \(b_{1}\) and \(c_{1}\), respectively, of generator A. Inverter branches D and E are connected to rotor phases \(b_{2}\) and \(c_{2}\), respectively, of generator B. The shared leg of the five-phase voltage inverter is marked in red.

In the literature, drive systems with two three-phase machines powered by a common 5-phase inverter are described only to drive systems with induction motors or permanent magnet synchronous motor10,11(PMSM). This topic is also widely described from the point of view of the pulse modulation technique, which is characterized in the next section of the text. However, the literature lacks descriptions of solutions dedicated to generator systems and application problems related to this type of solutions.

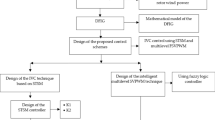

This article presents a new concept of a dual doubly-fed induction generator system configuration fed by a five-phase inverter with a common leg. This solution seems interesting for application in counter-rotating wind turbines with two generators. It allows control of both generators from the microprocessor controller of only one bidirectional power converter. The main contributions of this article are:

-

Conception of Dual energy generation system based on a two three-phase doubly-fed induction generators;

-

Adaptation on the simplified SVPWM technique for a five-leg inverter with dual three-phase output;

-

Experimental validation of the proposed configuration with control system based on field-oriented control method;

This paper is organized as follows: First, it presents the configuration of the dual doubly-fed induction generator system, with a description of the applied SVPWM algorithm dedicated to the two-machine system application with a five-phase inverter and the presentation of the field-oriented control structure. Next, it presents the test bench configuration and the results of experimental tests for the system’s steady and characteristic dynamic states. Finally, it contains a discussion and summary.

Dual generator system fed by five-leg VSI

Five-phase voltage source inverter topology

Figure 3 illustrates a dual generator system configuration in which a five-phase voltage source inverter powers two doubly-fed, three-phase induction machines, thereby eliminating the need for two transistor switches compared to a conventional dual three-phase voltage source inverter system. This change simplifies the inverter and converter design, allowing control of two three-phase generators with a single digital signal processor (DSP). This solution enhances the overall system control algorithm’s efficiency while also reducing capital costs, offering a cost-limited alternative to the traditional dual three-phase inverter configuration. In the presented configuration of powering a system of two generators using a single 5-phase inverter, complete identification of the converter’s output phase sequence is crucial. From the perspective of the overall system’s operation, it is irrelevant which phase is selected as the common phase. However, the chosen common phase must be identified, as correct system operation depends on the PWM algorithm, in which the adopted phase sequence is crucial.

SVPWM technique

During the past decade, different modulation techniques were proposed10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18. In12 authors showed the possibility of independent control of a dual-motor drive system (DMDS). The space vector pulse-width modulation (SVPWM) techniques for DMDS were discussed in13,14, with modulation techniques comparison in15 and topologies comparison in16. To control n three-phase motors fed by \((2n+1)\)-leg inverter a general PWM technique was proposed in17. In recent years, research on modulation techniques for DMDS focused on higher performance10 or algorithm simplification18. In18 the authors achieved a 42% shorter execution time than in conventional SVPWM techniques. In general, any carrier-based, e.g.19,20,21, or space vector PWMs can be used for such drive systems after the corresponding modification, where common-leg is be included to the calculation in a proper manner. Three-level voltages can be also generated, what was proven in22, where authors utilized CBPWM technique.

The implementation of SVPWM technique for a five-leg inverter with a dual-motor drive system is not new. Figure 4 shows the general principles of the SVPWM technique for a five-leg inverter with two three-phase outputs. However, this is the first attempt to implement such a modulation strategy in a dual doubly-fed induction generator system. The output voltage vector rotates inside a hexagon formed by eight vectors (6 – active and 2 – passive), as shown in Fig. 5. All vectors represent defined transistors’ state in each leg of the inverter. In dual-generator systems, two independent \(\alpha -\beta\) coordinate systems exist, as in conventional DMDS, so that, for each machine, active vectors should be identified and the durations of active vectors \(t_1\) and \(t_2\) need to be calculated.

The selected active vectors’ durations can be calculated from:

where \(V_{d}=Vn/V_{dc}\), \(V_n\) and \(V_{dc}\) are the nominal and dc-link voltage, respectively; \(T_s\) – switching period, \(V_{ref}\) is a matrix containing the reference vector components and V – a matrix consisting of normalized coefficients,18.

A Clarke transform matrix shows the relation between \(\alpha ,\beta\) voltage components and phase voltages \([V_A,V_B,V_C]\):

Considering a five-phase inverter as two independent three-phase systems, two combinations of vectors and times can be obtained at this step. Duration of transistors’ activation in each phase defines the average inverter phase voltage in a single switching period. Obtained times have been grouped and optimized, with the the average value remaining. First, these durations should be calculated for both three-phase outputs, utilising (1) and the \(\alpha ,\beta\) components obtained in (3), as:

where i is the generator number (system 1 or 2), \(g_{x_{V1}}^i\), \(g_{x_{V2}}^i\) – gates in each “x” phase, \(x=(A,B,C)\). The V1 and V2 indexes represent the selected active vectors. The ON index represents the ON state of the selected transistor. The result of (4) is shown in Fig. 6b, while the original switching sequence is shown in Fig. 6a.

The next step is a transition from a six-phase (two 3-phase systems) to a five-phase modulation scheme. Phase “A” was considered as an inverter common-leg during calculation, Fig 2. Introducing a zero-sequence component to the switching sequence, the output voltages remain unchanged, and the five durations are calculated as follows:

The resulting switching sequence after (6) is shown in Fig. 6c. From this step only the optimization procedure is left, to ensure the correct voltage generation. During the optimization it should be checked that all durations are not negative and not greater than the switching period \(T_s\). The optimization procedure can be expressed as follows:

From this stage, the modulation algorithm is ready to generate the output voltages correctly. In Fig. 6dthe resulting switching sequence was shown and the PWM structure is ready to generate voltages correctly receiving the reference voltage vectors from the control system.

Control system for stand-alone mode of generator

Operation of the dual generator system in stand-alone mode requires the excitation of both generators by supplying a magnetizing component (\(i_{msA}\)) of the current from the rotor side. The voltage at the stator terminal of generator A is regulated by controlling the direct axis rotor current \(i_{rAd}\). The direct reference axis rotor current \(i_{rAd}\) is obtained by processing the voltage error between the reference voltage \(U_{Aref}\) and the measured terminal voltage value \(|U_{sA}|\), taking into account the magnetizing current value, using proportional-integral PI 1 and PI 2 controllers, as shown in Fig. 7. The value of the magnetizing current component (\(i_{msA}\)) is calculated from the generator estimated stator flux \(\Psi _{dA}\) value A. The following parameters in the per-unit system were adopted for the control system. For the PI1 voltage regulator, the gain parameters for proportional and integral were Kp1 = 1.5 and Ki1 = 1.5, respectively. For the magnetising current controller, PI2, the gains were Kp1 = 1.2 and Ki1 = 0.5. The gain values of the d-axis and q-axis rotor voltage components controllers were set equal to Kp3=Kp4=1.2 and Ki3=Ki4=0.7. The dynamics of the entire control system largely depend on the PI controller settings in the cascade voltage control system. The priority in selecting the controller settings was to ensure the stable operation of the entire system. The primary purpose of a five-phase VSI supplying power to generator rotors is to maintain the voltage(\(u_{sA}\), \(u_{sB}\)) and frequency at the stator terminals of the machines under varying torque and varying load. The rotor side converter (RSC) is controlled in a stator flux-oriented reference frame. The application of the concept of modifying the SVPWM algorithm of a five-phase inverter to power a system of two three-phase generators from the rotor side, which was presented above, enables independent rotor voltage regulation in two independent orthogonal systems. For the correct implementation of dual generator control, information on the rotor position angle (\(\varphi _{rA}\), \(\varphi _{rB}\)) of each machine is necessary. The control structure diagram shown in Fig. 7 was adopted due to hardware limitations of the laboratory station configuration resulting from the inability to measure the shaft position angle \(\varphi _{rB}\) of generator B. A classic field-oriented control system for the stator flux (SFOC) of machine A was used to control generator A. The mathematical description of the structure of the control system is given in23. Generator B was controlled in an open feedback loop. The values of the rotor voltage components (\(u_{rB\alpha }\), \(u_{rB\beta }\)) in the second control plane for the SVPWM algorithm are calculated in the component generator block based on the set demanded amplitude and pulsation stator voltage value (\(U_{sB ref}\), \(\omega _{sBref}\)) and the set of rotor speed \(\omega _{rB}\). Functional blocks related to the voltage control of generator B are shaded in grey. The grid-side converter (GSC) control system, responsible for maintaining the necessary voltage in the DC-link circuit and the required power factor at the converter connection, is implemented independently and indicated in the drawing as a separate functional block. It is worth noting that both generators can operate in closed control systems after the elimination of hardware limitations without significant restrictions.

Experimental results

Experimental setup

The dual machine connection fed by a five-phase bidirectional power converter permits the utilization of two generators of disparate design. The system can be configured with a different rated power, a different number of pole pairs, and, most importantly, a different rated speed. This is in line with the theory presented in the previous section. The paper details the validation and testing of a dual doubly-fed generator system in a stand-alone mode configuration. Importantly, this setup does not require synchronization with the grid voltage, making implementing the control algorithm and hardware application conception more straightforward. The setup was designed to verify theoretical assumptions for independent stator voltage control on each generator’s terminal. The control system for the test bench configuration shown in Fig. 8 was implemented in a prototype of a bidirectional power converter (Con1) with a rated power of 5 kW. The basic specifications of the power converter prototype are provided in Table 1. The converter prototype utilized a DSP controller board with a Sharc ADSP21363 floating-point signal processor and an Altera Cyclone II FPGA. The PWM switching frequency was 3.3 kHz. The interrupt time was set to 150 ms. The prime mover system comprises two squirrel-cage motors (IM1 and IM2) that operate independently. The driving motors are supplied by commercial voltage source inverters (VSI) (Con2 and Con3). These motors drive three-phase identically doubly-fed generators with a power of 2kW (DFIG A and B) respectively. Generator parameters are shown in Table 2. For the correct operation of the entire generator system, it is necessary to measure the voltages on the stators of both machines and information about the angular position of the rotor of each generator. Due to hardware limitations regarding the number of measurement channels in the five-phase inverter used, the voltage on the stator terminals, the rotational speed and the shaft position angle were measured only for generator A in order to provide feedback for the voltage regulation system. Generator B was controlled in an open control loop. The five-phase converter prototype allowed for the connection of only one encoder. The three phase power windings on the stators of the DFIGs were connected to the external, independent, RC loads with variable resistance (LoadA, LoadB). The mechanical rotational speed (\(\omega _{rA}\), \(\omega _{rB}\)) of each generator was force-controlled by two motors IM1 and IM2 (Fig.8). A photo of the laboratory stand with relevant descriptions is shown in Fig. 9.

Laboratory tests

The following two groups of tests were carried out. The first group concerns the steady-states of the dual generator system operation, while the second group concerns the dynamic states. Laboratory tests were carried out to verify the possibility of independent regulation of voltage and frequency at each machine’s stator terminals and the harmonic content of the output voltage. The following notation convention was adopted to record the time waveforms of current and voltage values on oscillograms during testing. Waveform number one, viewed from the top of the oscilloscope screenshots, is the line-to-line voltage on generator A stator terminals (\(\ U_{sA}\)), followed by the line-to-line voltage on generator B (\(\ U_{sB}\)), the common-leg current of the inverter phase \(\ i_{A sum}\), the phase current of generator B (\(\ i_{e}\)), and the phase current of generator A (\(\ i_{b}\)). Steady-state tests were conducted for various configurations of load values on the terminal side of the generator stators. The first steady-state test was performed with a constant rotational speed of the first DFIG A and the second DFIG B equal to \(\omega _{rA}\), \(\omega _{rB}\)= 700 rpm, respectively. An essential feature of all generator system operation is the high quality of energy transferred to the power grid. Fig. 10 shows the time waveforms characterizing the system’s steady-state operation for both generators and the spectrum of harmonics for the measured stator terminal voltages for generators A (GEN A) and B (GEN B), respectively. The value of power transferred to the load was 250W for each generator. For the presented case, the THDu coefficient value for generator A was 1.51 %, while for generator B, it was 3.14 %. Fig. 11 shows the test results in which the generator stator load was increased to 500 W; the THDu coefficients for the measured voltages increased slightly to 1.52 % for generator A, and to 3.54% for generator B. A low content of higher harmonics characterises the measured voltages at the terminals of both generators. The slowly changing envelope voltage values at the terminals of generator B, amounting to 0.5 Hz, are the effect of the generator operating in an open control system and the lack of phase shift control between currents in a common phase. Elimination of this negative feature is possible after using a closed voltage control system of generator B and coordination of the setpoint values of the rotor current components (\(\ i_{rAq ref}\), \(\ i_{rBq ref}\))in the q-axis for generators A and B.

The tests in the system’s dynamic operating states included changes in the reference voltage of both generators \(U_{sAref}\), \(U_{sBref}\), step changes in the load value (Load A,Load B), and changes in the rotational speed \((\omega _{rA}\), \(\omega _{rB}\)) of the generator rotors.

The two-generator system is first operated under normal conditions with the load balanced in steady-state conditions. At time \(t_{1}\), the reference voltage for generator B changes from 200 Vrms to 300 Vrms, and at the time \(t_{2}\) step, it increases to 400 Vrms. The response of the controlled system is shown in Fig. 12. The next test involved the reverse reference voltage change situation for generator A. At the moment \(t_{1}\), indicated in the Fig. 13., a step change on the reference stator voltage amplitude, \(U_{refA}\), occurs for the generator A. The control system’s response to changes in the reference set voltage in generator A is slow, taking approximately 1 second to occur. The reason for this slow response was to ensure stable operation of the entire system, in which generator B is controlled in an open-loop control loop. As can be mentioned from figure, the amplitude of the independent rotor output current in phase E, for generator A changed and all five-leg currents waveform can be easily analyzed. The next test of the system operation included the system response to step changes in the load value at the stator terminals of generator A; generator B remained in a non-load state. Three-step load changes were forced during the test at moments \(t_{1}\), \(t_{2}\), and \(t_{3}\), respectively. This corresponded to a change in the load of generator A with active power in the range from 250 to 750W. The change in the generator load is visible in the step change in the value of the phase E current in the rotor circuit, generator A, and in the current of a common phase of the inverter \(\ i_{A sum}\).The system response is shown in Figure 14.

Figure 15 shows the generator system’s response in the case of changes in the rotational speed of the generator A shaft at a constant value of the generator B shaft speed. When the drive system of generator A forced the shaft speed to change in the range of 700-1000 rpm, i.e. from sub-synchronous to super-synchronous speed, the speed of generator B was maintained at 700 rpm. All tests of the dual generator system were performed at a reduced voltage. The descriptions under the oscillograms include the setting parameters for the individual oscilloscope voltage and current measurement channels and the time base for subsequent system tests.

Discussion

The article presents the application of a system of two three-phase generators powered from the side of the rotors by a five-phase voltage inverter in a common-phase configuration. The presented topology of generator connections allows for independent control of both generators. This configuration provides for the cooperation of two generators differing in rated power, rotor rotation direction, or range of rotational speed changes. This is important when using this solution in power generation systems for wind turbines rotating in the opposite direction. The cooperating generators do not have the same rated power value in such systems. The main generator driven by the first turbine is characterized by a power significantly more significant than the second generator, whose rotor rotates in the opposite direction to the rotor of the first generator. The rated power of the second generator is only a dozen or so per cent of the rated power of the first generator, and this difference depends on the aerodynamic properties of the working parts of the turbines. The power flow in the rotor circuits of both generators depends on the operating point of each machine, which results from the properties of such a generator design. Powering the generator systems in the proposed configuration allows for better energy management and reduced losses in the inverter system itself. The use of the five-leg VSI saves two switches, compared to alternative two independent three-phase VSI power systems. For this configuration of VSI, fewer components are required, which can lead to higher reliability. It should be noted that the common leg of the inverter carries the sum of the phase currents feeding the rotor of the two generators, so it is essential to consider the maximum values at the design stage of the five-phase inverter. It is worth noting that the presented solution allows both generators to fully utilize the available DC link voltage, provided that the total voltage requirements of both machines are within the range of the power supply capabilities. The PWM method used in the tested system is not new. The modulation method algorithm is easy to implement using standard DSP processors and allows control of two independent generators using only one DSP processor. The paper presents the results of experiments that verify the concept of using this solution for a two-generator system. The tests were carried out for the system’s steady and dynamic states. In steady-states of generator operation, the voltage at the stator terminals of both machines was characterized by low harmonic content and voltage THD coefficients below 5%.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are available upon request. Researchers interested in accessing the data should contact the corresponding author.

References

Fahlbeck, J., Nilsson, H., Arabnejad, M. H. & Salehi, S. Performance characteristics of a contra-rotating pump-turbine in turbine and pump modes under cavitating flow conditions. Renewable Energy 237, 121605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2024.121605 (2024).

Xiao, H. et al. Study of a novel rotational speed amplified dual turbine wheel wave energy converter. Applied Energy 301, 117423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2021.117423 (2021).

Wang, Z., Ozbay, A., Tian, W. & Hu, H. An experimental study on the aerodynamic performances and wake characteristics of an innovative dual-rotor wind turbine. Energy 147, 94–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2018.01.020 (2018).

Vasel-Be-Hagh, A. & Archer, C. L. Wind farms with counter-rotating wind turbines. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 24, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2016.10.004 (2017).

Salah, D. A. H., Nosier, M.A.E.-R. & Hamed, A. M. Investigation of the performance of a horizontal-axis dual rotor wind turbine. Scientific Reports 14, 6208. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-55844-6 (2024).

Radhakrishnan, J., Sridhar, S., Zuber, M., Ng, E. Y. K. & Shenoy, B. S. Conceptual design of airborne contra rotating VAWTs for rooftop wind energy. Scientific Reports 15, 6921. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-90601-3 (2025).

Newman, B. Actuator-disc theory for vertical-axis wind turbines. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics 15, 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-6105(83)90204-0 (1983).

Blecharz, K., Ryndzionek, R. & Kutt, F. Modeling and Control of a Brushless Multiphase Doubly-Fed Induction Generator in a Stand-Alone Wind Generation System. IEEE Access 12, 122340–122349. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3452415 (2024).

Ryndzionek, R., Blecharz, K., Kutt, F., Michna, M. & Kostro, G. Development and performance analysis of a novel multiphase doubly-fed induction generator. Archives of Electrical Engineering 71, 1003–1015, https://doi.org/10.24425/AEE.2022.142121 (2022).

Geng, Q. et al. An Improved PWM Method of Five-Leg VSI Fed Dual-PMSM System With Duty Cycles Regulation. IEEE/ASME Transactions on Mechatronics 27, 5771–5779. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMECH.2022.3190690 (2022).

Jing, G. & Zhou, C. Control strategy for a five-leg inverter supplying dual three-phase PMSM. IEEE Access 8, 174480–174488. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3025392 (2020).

Delarue, P., Bouscayrol, A. & Francois, B. Control implementation of a five-leg voltage-source-inverter supplying two three-phase induction machines. In IEEE International Electric Machines and Drives Conference, 2003. IEMDC’03., 3, 1909–1915, https://doi.org/10.1109/IEMDC.2003.1210713 (publisherIEEE, 2003).

Vukosavic, S. N., Jones, M., Dujic, D. & Levi, E. An improved PWM method for a five-leg inverter supplying two three-phase motors. In 2008 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics, 160–165, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISIE.2008.4676881 (publisherIEEE, 2008).

Jones, M., Vukosavic, S., Dujic, D., Levi, E. & Wright, P. Five-leg inverter PWM technique for reduced switch count two-motor constant power applications. IET Electric Power Applications 2, 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1049/iet-epa:20070497 (2008).

Jones, M., Dujic, D. & Levi, E. A performance comparison of PWM techniques for five-leg VSIs supplying two-motor drives. In 2008 34th Annual Conference of IEEE Industrial Electronics, 508–513, https://doi.org/10.1109/IECON.2008.4758005 (publisherIEEE, 2008).

Jacobina, C. B. et al. Reduced Switch Count Multiple Three-Phase AC Machine Drive Systems. IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 23, 966–976. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPEL.2007.915027 (2008).

Dujic, D., Jones, M., Vukosavic, S. & Levi, E. A General PWM Method for a \((2n + 1)\) -Leg Inverter Supplying \(n\) Three-Phase Machines. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 56, 4107–4118. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2009.2014909 (2009).

Kondratenko, D. & Lewicki, A. A Simplified SVPWM Technique for Five-leg Inverter with Dual Three-phase Output. In 2023 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICECCME57830.2023.10252832 (publisherIEEE, 2023).

Can, E. & Sayan, H. H. Development of fractional sinus pulse width modulation with β gap on three step signal processing. International Journal of Electronics 110, 527–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207217.2022.2040056 (2023).

Can, E. The levels effect of the voltage generated by an inverter with partial source on distortion. International Journal of Electronics 107, 1414–1435. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207217.2020.1726496 (2020).

Can, E. & Kilic, U. A new high-frequency multilevel inverter effecting cables weight and energy efficiency of aircraft. Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology 96, 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1108/AEAT-06-2023-0158 (2024).

Odeh, I. C., Lewicki, A., Morawiec, M. & Ojo, J. O. A Five-Leg Three-Level Dual-Output Inverter. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 70, 690–694. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2022.3211273 (2023).

Achkar, M. E., Mbayed, R., Salloum, G., Patin, N. & Monmasson, E. Voltage Control of a Stand-Alone Cascaded Doubly Fed Induction Generator. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 66, 762–771. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2018.2856186 (2019).

Funding

This work has been developed as a result of research carried out in the Leader XIII Program, contract no. LIDER13/0153/2022, funded by the Polish National Centre for Research and Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.B. Conceptualization, methodology, validation, resources, writing-review and editing, data curation; K.B. and D.K.: writing text, conducted the experiment, analysed the results; D.K. the PWM algorithm. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blecharz, K., Kondratenko, D. A dual doubly-fed generator system supplied by a five-phase voltage inverter. Sci Rep 15, 33439 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19073-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19073-9