Abstract

The rice weevil, Sitophilus oryzae L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), is a formidable global pest of storage grains. This study investigated how the interplay between the physicochemical grain parameters of wheat cultivars and the pest’s physiological response modulates the resistance to the rice weevil. A forced-choice test evaluated the susceptibility of wheat cultivars based on parameters viz., percent weight loss of grains, adult emergence, mean developmental period, and susceptibility index. Among the wheat cultivars, HI 1544 and GW 322 were the least susceptible, while, PBW 343, HD 1563, and HI 8381 were highly susceptible. A significant positive correlation was noticed between percent weight loss and factors such as adult emergence, mean developmental period, total soluble sugars, starch, and insect digestive enzymes. In contrast, grain damage was negatively correlated with grain hardness, protein, amylolytic activity, and phenol content of grains. Principal component Analysis (PCA) accounted for 73.65% of the observed variation, effectively delineating key traits. Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC) classified wheat cultivars into two categories based on their susceptibility to rice weevil. We recommend prioritizing less susceptible cultivars (e.g., HI 1544, GW 322) for breeding programs and infestation-prone regions. The findings emphasise that a holistic analysis of physicochemical and biological parameters offers a robust framework for screening resistance of wheat cultivars to rice weevil S. oryzae.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the most extensively cultivated crops worldwide, spanning an expansive 218 million hectares and serving as a vital source of nutrition for nearly 40% of the global population1. India is a significant contributor to wheat production, holding 14.13% of the global wheat production of 784.91 million metric tons (MMT)2. The country’s bulk storage facilities handle approximately 60 MMT of grain annually3with an unfortunate annual loss of 14 MMT, amounting to Rs. 7000 crores. Among the factors contributing to these losses, insects are the primary culprits, causing a substantial financial setback of Rs. 1300 crores in India4.

Wheat grains under storage are damaged by several insect pests (e.g., Rhyzopertha dominica (F.), S. oryzae, Tribolium confusum (du Val.), and Trogoderma granarium (E.)), resulting in both quantitative and qualitative losses. Among these pests, the rice weevil (S. oryzae) is a devastating one, causing damage by feeding the grains and contaminating the products5. The grains are reduced to hollow shells as a result of feeding by the larvae and adult stages. It is reported as the most ruinous and pervasive insect pest of cereals throughout the world, inflicting 18–48% loss to grains in storage6. It is a severe loss, considering the maximum permissible limit for insect-infested grains by the Codex Alimentarius Commission is only 1.5%. Besides wheat, rice weevil feeds on corn, rice, oats, sorghum, buckwheat, barley, and their products.

The use of resistant cultivars has already been proposed as a potential strategy to control S. oryzae along with various stored grain insects7. Several physicochemical characteristics viz. phenolic acids, grain hardness, amylose content8and protein content9 were reported to be associated with lesser damage by stored grain pests. Despite these defensive characteristics, insects have developed diverse tactics to surpass plant defences, enabling them to thrive and reproduce on their hosts10. When insects are compelled to feed on unbalanced diets, they rely on their digestive system to regulate the amount of nutrients consumed11.

Wheat being a substantial source of carbohydrates and proteins, relies on amylases and proteases are the core digestive enzymes to intricately facilitate the digestion process for insects that feed on it12. Several studies have investigated the amylase and proteinase content across different species of stored grain insects, highlighting their critical role in nutrient acquisition13,14,15. The growth and proliferation of insect pests are influenced by nutritional challenges, unbalanced nutrition, and seed hardness, which will ultimately decide the level of resistance against the insect pests11. Hence, multiple resistance factors should be investigated for imparting durable resistance in grains to reduce the damage by stored product pests.

Several researchers have undertaken screening of the wheat cultivars for their resistance against rice weevil by measuring parameters such as weight loss of grains, adult emergence, and mean developmental period of the pest16,17. Employing the susceptibility index18researchers have categorized crop cultivars based on their resistance or susceptibility to insects8,19,20. While factors including protein, carbohydrate21,22 amylolytic activity22and phenol content17 show associations with resistance against S. oryzae, seed hardness and seed index23 were prioritized as key industry-standard physical traits influencing insect feeding efficiency, per international grain quality guidelines24. Despite these individual associations, a significant knowledge gap persists regarding the cumulative contribution of physicochemical factors of grains in imparting varietal resistance against the rice weevil25. By applying appropriate statistical and computational analysis, the cultivars can be categorized based on the dataset of physicochemical components of grains. One method employed for Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA) of cultivars is Principal Component Analysis (PCA), a multivariate statistical tool as demonstrated by Zheng et al.26. Additionally, Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC) has been used for categorizing crop cultivars depending on their similarities, as illustrated through a dendrogram27,28,29.

Our study has implemented an intricate screening protocol to assess the resistance of wheat cultivars to rice weevils. This protocol meticulously considers various physicochemical characteristics of wheat grains, including seed hardness, seed index, protein content, total soluble sugars, starch content, amylolytic activity, and phenol content besides estimating activities of digestive enzymes like amylases and proteases of rice weevil. The forced choice assay was carried out to assess the influence of the aforementioned factors on the biological parameters of the insect. These parameters include adult emergence, mean developmental period, and their effect on grain weight loss resulting from infestation. A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was followed to corroborate the cultivar differences in the damage potential of rice weevil. Further, an Agglomerative Hierarchical Clustering (AHC) analysis was done to fine-tune the categorization of wheat cultivars into resistant and susceptible ones against the weevil. The outcomes of our study have underscored the utility of polyphasic screening protocol in identifying the resistant and susceptible cultivars of wheat against rice weevil.

Results

Forced choice test

Responses of S. oryzae to wheat cultivars were assessed through the estimation of percent weight loss of grains, adult emergence, and mean developmental period through forced choice tests (Table 1).

Significant differences in weight loss were observed between the wheat cultivars when exposed to feeding by the rice weevil. Percent weight loss of grains ranged from 2.70 ± 0.5 to 8.86 ± 1.4. The cultivars like HI 1544, GW 322, and HI 3117 recorded relatively lower weight loss (2.7–3.3%), while PBW 343 and HD 1563 experienced higher weight loss (> 8%). Other cultivars displayed a percentage of weight loss ranging between these values. Adult emergence varied considerably among cultivars, ranging from 18.0 ± 2.3 (GW 322) to 47.2 ± 4.1 (PBW 343). This variation reflects the differential susceptibility of the cultivars to rice weevil infestation. The mean developmental period, another critical aspect for assessing the survival and choice of insect, varied from 30.53 days (PBW 343) to 42.9 days (HI 1544). Along with HI 1544, the wheat cultivars, GW 322 (41.93 ± 0.5), HD 3117 (38.61 ± 0.8), HD 3118 (38.19 ± 1.0), HD 3086 (37.85 ± 1.3), HD 3059 (37.8 ± 0.7), and HD 4728 (39.72 ± 1.1), also recorded prolonged MDP. The susceptibility index ranged from 2.94 (GW 322) to 5.46 (PBW 343) with the lowest value comparable to most cultivars except for HD 3090 (4.43 ± 0.07), HI 8381 (4.88 ± 0.21), HI 1563 (4.92 ± 0.23), and PBW 343 (5.46 ± 0.13).

Categorization of wheat cultivars

The wheat cultivars chosen for this study were assigned ranks from 1 to 14 according to their overall score against the parameters viz., percent weight loss of grains, adult emergence, MDP, and SI, as detailed in Table 2. The cultivars with the lowest overall score of 6 (HI 1544 and GW 322) were ranked 1, indicating their least susceptible nature, while the cultivar PBW 343, with the highest overall score of 63, secured the 14th rank, showing its most susceptible nature.

Physicochemical parameters of wheat cultivars responsible for resistance

Physiochemical characteristics of wheat cultivars, such as seed hardness, seed index, soluble protein, total soluble sugar, starch, amylolytic activity, and phenol content, were measured as indicated in the methods above, and the results are summarized in Table 3.

The highest seed hardness (136 newtons) was recorded by two cultivars, HI 1544 and GW 322, while PBW 343 recorded the lowest seed hardness of 83.5 newtons. Most of the cultivars showed seed hardness of more than 100 newtons. Regarding the seed index or 100 seed weight, HD 4728 (4.80 ± 0.08 g) displayed the maximum value and HI 1500 had the minimum (3.58 ± 0.08 g), while the rest of the cultivars had a seed index ranging from 3.72 to 4.53 g.

The soluble protein content of wheat cultivars exhibited significant variability, ranging from 10.64 ± 0.16 mg/g to 14.77 ± 0.11 mg/g. The highest protein content was observed in HI 1544 (14.77 ± 0.11 mg/g), which was on par with GW 322 (14.48 ± 0.15 mg/g). Conversely, HI 8381 showed the lowest protein content (10.64 ± 0.16 mg/g), aligning with HD 3165 (10.87 ± 0.07 mg/g), PBW 343 (11.32 ± 0.12 mg/g), and HD 2932 (11.37 ± 0.11 mg/g).

The total soluble sugar content of the cultivars ranged from 64.16 ± 0.7 mg/g (GW 322) to 106.95 ± 0.42 mg/g (HD 1563). The TSS content of HD 1563 was comparable to that of HD 3090 (105.52 ± 0.9 mg/g) and PBW 343 (104.54 ± 0.6 mg/g). All other cultivars displayed TSS content within the range of 71.08 mg/g and 103.5 mg/g.

Among the evaluated cultivars, the lowest starch content of 41.81 ± 0.9% was recorded with HI 1544, which was on par with GW 322 (42.41 ± 0.19%) and HD 4728 (44.31 ± 0.5%). The highest starch content of 71.65% was observed in HD 3059 and PBW 343, comparable to HD 3165 (69.75 ± 0.58%). The starch content of the remaining cultivars varied from 45 to 69.7%.

The highest recorded amylolytic activity was observed in cultivar HI 1544 (7.69 ± 0.04 U/mg protein) and GW 322 (7.66 ± 0.08 U/mg protein). Conversely, the lowest activity of 6.02 U/mg protein was recorded with the cultivars HD 3184, HI 8381, and PBW 343, which were on par with HD 1563 (6.03 ± 0.05 U/mg protein), HD 2932 (6.11 ± 0.04 U/mg protein), HD 3090 (6.29 ± 0.06 U/mg protein), HD 2967 (6.30 ± 0.04 U/mg protein), HD 3059 (6.31 ± 0.04 U/mg protein) and HD 3086 (6.34 ± 0.05 U/mg protein). The amylolytic activity of the remaining wheat cultivars ranged between 6.39 and 6.77 mg/g.

The highest phenol content of 2.01 ± 0.03 mg/g was recorded with the cultivar HI 1544, and the lowest of 1.41 ± 0.01 mg/g was recorded with both PBW 343 and HI 8381, which was on par with HD 1563 (1.43 ± 0.01 mg/g), HD 2967 (1.47 ± 0.01 mg/g) and HI 1500 (1.48 ± 0.01 mg/g). Other cultivars ranged in phenol content between 1.49 and 1.92 mg/g.

Enzyme activities of S. oryzae

Amylase and protease activity were estimated in S. oryzae adults as a measure to assess their food utilization. Amylase and protease activity of adults reared on different wheat cultivars showed significant differences (Table 4). The highest amylase activity of 7.4 ± 0.16 U/mg protein was observed in adults fed on cultivar PBW 343, which was on par with HD 2932 (7.1 ± 0.04 U/mg) and HI 8381 (7.1 ± 0.03 U/mg). The lowest amylase activity was observed with cultivar HI 1544 as 4.4 ± 0.04 U/mg, which was on par with GW 322 (4.6 ± 0.06 U/mg), HD 3086 (4.6 ± 0.04 U/mg), HI 1500 (4.6 ± 0.07 U/mg), and HD 2967 (4.8 ± 0.04 U/mg).

The highest protease activity was noted in rice weevil adults fed on cultivars HI 1563 and PBW 343 as 0.49 ± 0.02 U/mg, which was statistically on par with HI 8381 (0.48 ± 0.04 U/mg). The protease activity of insects reared on cultivars HI 1544 and GW 322 was the lowest (0.19 ± 0.02 U/mg), while the insects maintained on the rest of the cultivars recorded protease activity in the range of 0.25 to 0.42 U/mg.

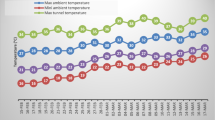

Correlation analysis

A correlation analysis between all assessed damage parameters and insect responses was done, and the results are depicted in Fig. 1 (see details in Table S1 of supporting information). Among the parameters of the forced-choice test, the results revealed a significant positive correlation of grain weight loss with adult emergence (0.818**; P = 0) and a significant negative correlation with MDP (− 0.242**; P = 0.003). A perusal of correlation analysis data shows that wheat grain weight loss due to rice weevil damage is negatively correlated with seed hardness (− 0.317**; P = 0.003), protein content (− 0.257*; P = 0.024), amylolytic activity (− 0.296**; P = 0.009) and total phenol content (− 0.381**; P = 0.001) and it was having a positive correlation with TSS (0.384**; P = 0.001), starch content (0.232*; P = 0.042), insect amylase (0.295**; P = 0.009) and insect proteases (0.373**; P = 0.001).

Graphical representation of the correlation matrix for all assessed damage parameters due to rice weevil. Brighter squares of green and red indicated large positive and negative correlations respectively, whilst smaller correlations are represented by darker shades. (percent weight loss of grains (WL), Adult emergence (AE), mean developmental period (MDP), seed hardness (SH), seed index (S.I.), total soluble sugars (TSS), amylolytic activity (AA), insect amylase (IA) and insect protease (IP)).

Discussion

Screening methods exhibit variability contingent upon the pest or crop under consideration30. Employing a force choice test for screening wheat cultivars against rice weevils could prove to be an effective technique for identifying resistant cultivars31. This method, involving the confinement of test insects to food grains, constitutes a prevalent laboratory screening approach widely employed for the evaluation of crop cultivar resistance. A key component of this approach is the evaluation of biological parameters related to storage insect pests, which offers a thorough grasp of the resistance profile of the cultivar32. In line with this approach, our study demonstrates a clear distinction that susceptible wheat cultivars were characterized by early and rapid adult emergence, while delayed adult emergence was noticed in less susceptible lines. These findings are consistent with earlier reports33,34,35which noted higher insect emergence and weight loss in susceptible cultivars, whereas resistant wheat and maize grains were associated with prolonged developmental periods. Similarly, Shafique & Chaudry36 associated low insect populations and minimal grain weight loss with grain resistance. In our study, early adult emergence reflected by a lower MDP, was characteristic of more susceptible cultivars. Comparable relationships between grain weight loss, adult emergence, and developmental period have also been observed in rice genotypes19,37. This aligns with the categorization of wheat varieties by Arve et al.17 based on oviposition preference, duration of life cycle, percentage of grain damage, and percentage of grain weight loss. Similarly, Bhanderi et al.38 applied the susceptibility index to screen sorghum genotypes, while cumulative biological traits were used to categorize wheat20 and rice39 cultivars. Together, these studies highlight that traits including percent weight loss of wheat grains, adult emergence, mean developmental period of the weevil, and susceptibility index provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating cultivar resistance to S. oryzae. Several reports have shown that the physicochemical characteristics of grains have a profound impact on the developmental traits of the pest5,19. Our studies have indicated significant differences in the damage potential of rice weevil when reared on wheat cultivars with varying physicochemical features. Seed hardness is considered one of the most imperative physical factors influencing insect pest damage22. Consistent with our findings, previous studies19,23,40,41 reiterated that harder grains in sorghum and rice were associated with reduced grain damage and lower weight loss caused by S. oryzae. Macronutrients, particularly proteins, and carbohydrates, are recognized to be the primary determinants influencing the proliferation of insect pests11with wheat varieties exhibiting higher protein content observed to be relatively more resistant to storage insects42. Additionally, several researchers have noticed a negative association between the damage inflicted by S. granarius and S. oryzae with the protein content of wheat grains17,22. A similar inverse relationship between insect damage and grain protein content was displayed by our research. While higher protein content imparts resistance, higher carbohydrate content in grains can aid faster development of insects, thus making the grains susceptible to insect attack11. Soujanya et al.43 and Aly & Ali44 observed a positive relation between the starch content of grain and the damage by S. oryzae in maize and wheat, respectively, which are in line with the findings of our study. Starch serves as the predominant form of storage polysaccharides in seeds and is primarily degraded via the amylolytic pathway during seed germination45. Piasecka-Kwiatkowska et al.46 further suggested that the development of granary weevil larvae can stimulate saccharide metabolism resulting in enhanced amylolytic activity. Our observations are in line with Nawrot et al.22 who observed that having an enhanced amylolytic activity in wheat grains could be considered a factor of resistance against the grain weevil. Phenols are important secondary metabolites in imparting resistance against pathogens as well as insect pests47. In general, the antinutritional, antibiotic, or unpalatable nature of phenolic compounds contributes to their defensive property48. Phenolics play a crucial role in protecting the grain, with Ramputh et al.8,49 further demonstrating a significant negative correlation between the phenolic content of sorghum grains and the weight loss caused by S. oryzae. Consistent with these findings, Ngom et al.8 also found that elevated phenol content in maize showed resistance to the larger grain borer (Prostephanus truncates (Horn)), aligning closely with the outcomes of the present study.

The physiological response of insects varies with varietal resistance. In this study, the activities of amylase and protease of adult weevils fed on different wheat cultivars were considered. A positive correlation was observed in the case of both amylase and protease activity of the insect with weight loss of grains. The higher the activity of amylase and protease, the more grain weight loss and the greater the susceptibility of the wheat cultivar to rice weevil. Changes in digestive enzyme activity in response to diet content and growth and development have previously been reported by Chi et al.50 and Fabres et al.51 in cowpea bruchids and red flour beetles, respectively. As amylose is the predominant storage carbohydrate in grains and seeds, an endowment of high amylase content facilitates better digestion and absorption of carbohydrates in insects feeding on grains or seeds52. This has been exemplified in a study involving lesser grain borer R. dominica and rice weevil S. oryzae feeding on barley and rice cultivars, respectively11,53.

The mechanism of insect resistance to cereal grains is a complicated phenomenon, and it relies on multiple physiochemical characteristics of grain and the biochemical and physiological adaptation of post-harvest insects to them54. Grains, in contrast to plants, do not change their chemical composition and food quality during storage. Thus, grain-feeding insects consume consistent food without any defensive compounds changing in amounts during storage and insect development. Hence, the biochemical grain constituents like protein, phenol, and amylolytic activity that are nontoxic to humans and physical characteristics like seed hardness that do not interfere with grain processing while at the same time possessing targeted activity against storage insect pests can be employed in reducing the damage.

Varietal resistance is a complex phenomenon, and hence, it is essential to identify the key components and their interactions to find the role of different parameters in conferring resistance. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is employed to reduce dimensionality, retain crucial information, and identify critical components that account for the majority of variation in the dataset. Several researchers have used PCA to identify the vital components of host plant resistance against various insect pests19,55. Taking into consideration all the twelve parameters viz., adult emergence, MDP, percent weight loss of grain, seed hardness, seed index, protein, total soluble sugars, starch, amylolytic activity, phenol, insect amylase, and insect protease, PCA was performed. Using the Kaiser normalization process, two principal components (PCs) have been identified with eigenvalues above 1.0 (see more details in Figure S1 of supporting information). All of the variables evaluated had extraction commonality of less than 0.5, conveying that the variables were accurately reflected by the extracted PCs, which together accounted for 73.65% of the total variation. While PC2 accounted for 11.98% of the variation, PC1 explained 61.67% of it. PC1 had the loadings for adult emergence (0.845), mean development period (− 0.904) percent weight loss of grain (0.925), seed hardness (− 0.809), protein (− 0.775), total soluble sugars (0.879), starch (0.627), amylolytic activity (− 0.863), phenol (− 0.816), insect amylase (0.729) and insect protease (0.789). While the seed index (0.876) was loaded in PC2 (see more details in Table S2 of supporting information).

The correlation circle and the biplot obtained from PCA shows the parameters being placed further from the origin, indicating that more variability of them is represented by the two displayed principal components (Figs. 2 and 3). Biplot also represents a positive correlation of PC 1 with adult emergence, weight loss percent, total soluble sugars, starch, insect amylase, and insect protease, and a negative correlation with MDP, seed hardness, seed index, protein, amylolytic activity, and phenol. A positive correlation of PC 2 with all the parameters except seed hardness, total soluble sugars, phenol, and starch can also be observed.

Correlation circle showing the association between the different parameters under study. The data points are the average of five replications. The parameters which are on the opposite side are negatively correlated, while those which are closely placed shows a positive correlation and the one which is orthogonally placed do not correlate with each other. It is evident from the correlation circle that all of the variables are positioned far from the center, indicating the principal components’ ability to explain the variables. Thus, it is evident that the variables protein and starch, TSS and AA, are negatively correlated to each other and those that are close to one another like AA, SH, and phenol are positively correlated.

Biplot of principal component analysis (PCA). Axis 1 for principal component 1 with adult emergence (AE), mean developmental period (MDP), percent weight loss of grains (WL), seed hardness (SH), protein, total soluble sugars (TSS), starch, amylolytic activity (AA), phenol, insect amylase (IA) and insect protease (IP) and axis 2 for principal component 2 with seed index (S.I.). Lines with blue dots represent the various parameters and orange dots represent the wheat cultivars understudy in the order HI 1544 (1), GW 322 (2), HD 3117 (3), HD 3184 (4), HD 3118 (5), HD 2932 (6), HD 3086 (7), HD 3165 (8), HI 1500 (9), HD 2967 (10), HD 3059 (11), HD 3090 (12), HD 4728 (13), HI 8381 (14), HD 1563 (15) and PBW 343 (16).

The clustering of a large set of varieties into homogeneous subsets is a useful tool in identifying varieties with desirable traits. This helps to bring the maximum number of desired traits into varieties with minimum effort56. AHC is a tool used by several researchers in categorizing crop varieties based on their similarities27,28,29. AHC of the description with a dendrogram (Fig. 4) has identified two major groups of cultivars, where group 1 has cultivars HD 3059, PBW 343, HI 8381, HD 1563, HD 2967, HD 4728, HI 1500, and HD 3090, which belongs to the susceptible categories of previous classification with higher rank positions (Table 2). Group 2 comprises cultivars HI 1544, GW 322, HD 3086, HD 3184, HD 2932, HD 3165, HD3117, and HD 3118, which belong to the less susceptible category. Also, among them, HI 1544 and GW 322 have more similarities as compared to HD 3117. Hence, the characteristics of cultivars GW 322 and HI 1544, which have a negative impact on the performance and digestive enzymes of S. oryzae, could be regarded as resistance factors against this pest.

Conclusion

The results indicate that various physicochemical factors of grains, along with biological parameters of S. oryzae, were found to influence its damage potential, as revealed by the cultivar ranking based on percent weight loss, adult emergence, MDP, and susceptibility index. The cultivars HI 1544 and GW 322 were identified as the least susceptible (rank 1) and the cultivar PBW 343 was determined to be most susceptible (rank 14). Further analysis unveiled a significant positive correlation of percent weight loss with adult emergence, MDP, total soluble sugars, starch, and insect digestive enzymes (amylase and protease), whereas a significant negative correlation with grain hardness, protein content, amylolytic activity, and phenol content of grains. A principal component analysis extracted two PCs explaining 73.65% of the cumulative variation, and to enhance the interpretability, an agglomerative hierarchical cluster (AHC) analysis was run in conjunction with it, grouping the wheat cultivars into two categories based on their susceptibility to rice weevil. HI 1544 and GW 322 clustered within the less susceptible group, demonstrating high similarity and suitability for breeding programs or storage in infestation-prone regions. Crucially, our findings reveal that one-dimensional analysis of either physical or biochemical factors may be insufficient to predict the resistance of grains to stored grain pests, considering the physiological flexibilities conferred by certain digestive enzymes like amylases and proteases to the pest. Therefore, a comprehensive analysis considering all contributing variables, as demonstrated in our study, would facilitate the identification of the relative resistance of cereal grains to rice weevil.

Materials and methods

Wheat (Triticum aestivum) cultivar collection

Freshly harvested grains from sixteen wheat cultivars (HI 1544, GW 322, HD 3117, HD 3184, HD 3118, HD 2932, HD 3086, HD 3165, HI 1500, HD 2967, HD 3059, HD 3090, HD 4728, HI 8381, HD 1563, and PBW 343) were procured from the Division of Genetics and Division of Seed Science and Technology at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), New Delhi. These cultivars represent widely adopted Indian varieties with diverse traits: high-yield potential (e.g., HD 2967, HD 3086, GW 322, HD 2932, HI1544, PBW 343, HD 3117, HD 3059, HI 8381)57,58,59,60,61disease resistance (e.g., PBW 343 and HD 1563 against rusts62HD 2967 63 and HD 318464 against spot blotch, HI 1544 and HI 150065 against leaf rust, HD 4728 against brown rust, HI 8381 for brown and black rust66 and abiotic stress tolerance (e.g., HD 3090 67 and HD 293268 for heat, HI 150059 for drought tolerance, GW 32266, HD 3118 and HD 316569 for heat tolerance). The grains were thoroughly cleaned and inspected to remove damaged ones and prevent contamination. Before the commencement of experiments, the grains were conditioned to achieve a moisture content of 13–14% by maintaining a relative humidity (RH) of 70% by following the KOH method, as outlined by Solomon70.

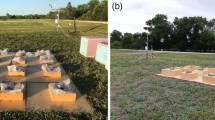

Insect rearing

The insect sample (S. oryzae) for the study was identified71collected, and maintained on whole wheat grains at the stored product insect laboratory within the Division of Entomology, IARI, New Delhi, India. The insect culture was maintained in glass jars (1.5 L) secured with muslin cloth, adhering to the standard rearing protocol, maintaining a temperature of 27 ± 1 °C and an RH of 70 ± 5% in growth chambers (Accumax India)16. Subcultures were periodically initiated to sustain a continuous insect supply.

Screening of wheat cultivars under forced choice test

Forced choice experiments were conducted as per the methodology outlined by Jha et al.16 to assess the response of adult weevils of S. oryzae against all 16 wheat cultivars. For the forced choice test, 500 grains of each cultivar were separated into five replicates of 100 grains each. After recording the initial weight, these grains were transferred to glass vials measuring 6.5 cm height and 1.5 cm diameter, and covered with a cotton plug. Two pairs (with a male and a female in each pair) of newly emerged adult insects were inoculated to each of those vials and were kept for oviposition for a week. The experiment was conducted under controlled conditions, with the temperature consistently maintained at 27 ± 1 °C and relative humidity at 70 ± 5%. After a week, the weevils were removed and the glass vials were left undisturbed for observation. Periodic observations were taken on alternate days (See more details in Table S3 of supporting information), and the adults were counted and removed as soon as they emerged. Monitoring continued until no adults appeared for ten consecutive days72and their final sample weight was determined after that.

-

(i)

The percent weight loss of wheat grains after the insect infestation was determined using the formula73.

where, IW- the initial weight of the wheat grains. FW- the final weight of wheat grains after insect damage.

-

(ii)

The time it takes for 50% of adults to emerge following oviposition is known as the mean development period (MDP). It was estimated by using the formula74:

where, D1- the day when adults began to emerge; A1- the number of adults emerged on the D1th day; (A1 + A2 + A3…An)- Total number of adults emerged.

-

(iii)

The susceptibility index (SI) of each cultivar was determined using the following formula proposed by Dobie18:

where, F = Number of adults that emerged. D = Mean developmental period.

Categorization of wheat cultivars

The wheat cultivars were categorized into two groups, namely less susceptible and highly susceptible, determined by their performance concerning parameters such as percent weight loss of grains, adult emergence, MDP, and SI. To achieve this classification, the varieties were ranked on a scale of 1–14, following the methodology outlined by Mehta & Kumar20.

Quantification of physicochemical characteristics of wheat grains

Physical parameters viz., seed hardness and seed index (100 seed weight) were determined with a texture analyzer (TA.XT2i by Stable Micro Systems) and an electronic weighing balance (Mettler XPR206DR), respectively. For each wheat cultivar, the experiment was replicated five times.

The biochemical characteristics of the grains viz., protein75,total soluble sugars (TSS)76,starch77,amylolytic activity78, and phenol contents79 were estimated by using standard protocols mentioned herewith (see details in Appendix S1 of supporting information). The whole experiment was replicated five times for each wheat cultivar.

Quantification of enzyme activity of rice weevil

Physiological responses of rice weevil to the wheat cultivars were assessed by measuring the activities of digestive enzymes like amylases80 and proteases81,82 by following standard protocols (see details in Appendix S2 of supporting information). Newly emerged, unsexed adult insects (both males and females), reared on each of the sixteen wheat cultivars were taken for the assay. Twenty adult weevils were homogenized with ice-cold potassium phosphate buffer (pH-7), and the assay was performed with the supernatant.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, Version 16 (SPSS) and XL STAT. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the differences in the levels of insect susceptibility between various treatments. Means were categorized into homogenous groups and compared using Tukey’s test at a significance level of 0.05%. To explore the relationship between the different growth parameters of the investigated insects, a one-tailed Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) analysis was conducted. The XL STAT software was used to execute the correlation test, principal component analysis (PCA), and agglomerative hierarchical cluster (AHC) analysis.

Data availability

All data analyzed in this study are included in this article or are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Giraldo, P., Benavente, E., Manzano-Agugliaro, F. & Gimenez, E. Worldwide research trends on wheat and barley: a bibliometric comparative analysis. Agronomy 9, 352 (2019).

Statista Production of wheat worldwide from 1990/91 to 2023/24. https://www.statista.com/statistics/267268/production-of-wheat-worldwide-since-1990/ (2024). (accessed 29 Nov).

Ranjith, H. V., Sagar, D., Kalia, V. K., Dahuja, A. & Subramanian, S. Differential Activities of Antioxidant Enzymes, Superoxide Dismutase, Peroxidase, and Catalase vis-à-vis Phosphine Resistance in Field Populations of Lesser Grain Borer (Rhyzopertha dominica) from India. Antioxidants 12, 270 (2023).

Banga, K. S., Kumar, S., Kotwaliwale, N. & Mohapatra, D. Major insects of stored food grains. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 8, 2380–2384 (2020).

Srivastava, C. & Subramanian, S. Storage insect pests and their damage symptoms: an overview. Indian J. Entomol. 78, 53 (2016).

Tiwari, S. C., Rao, A. S. & Dwivedi, B. K. Effect of storage period and interspecific competition among Sitophilus oryzae (L.), Rhizopertha dominica, and Tribolium castaneum on their population build-up and resultant loss to 6 varieties of wheat. Indian J. Entomol. 5, 411–415 (1989).

Chaudhary, R. S., Dubey, P., Regmi, R. & T. & Varietal resistance of wheat to the rice weevil (Sitophilous oryzae) under stored condition. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 11, 307–313 (2021).

Ngom, D. et al. Varietal susceptibility of maize to larger grain borer, Prostephanus truncatus (Horn) (Coleoptera; Bostrichidae), based on grain physicochemical parameters. PLoS One 15, (2020).

Kalsa, K. K. et al. Susceptibility of Ethiopian wheat varieties to granary weevil and rice weevil infestation at optimal and sub-optimal temperatures. J. Stored Prod. Res. 83, 267–274 (2019).

Mello, M. O. & Silva-Filho, M. C. A cross-talk between plants and insects plant-insect interactions: an evolutionary arms race between two distinct defense mechanisms. J Plant. Physiol 14 (2002).

Jalaeian, M., Mohammadzadeh, M., Mohammadzadeh, M. & Borzoui, E. Rice cultivars affect fitness-related characteristics and digestive physiology of the rice weevil, Sitophilus oryzae (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J Stored Prod. Res 93, (2021).

Borzoui, E., Bandani, A. R., Goldansaz, S. H. & Talaei-Hassanlouei, R. Dietary protein and carbohydrate levels affect performance and digestive physiology of Plodia interpunctella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 111, 942–949 (2018).

Baker, J. E. Amylase/proteinase ratios in larval midguts of ten stored-product insects. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 40, 41–46 (1986).

Oppert, B. Effects of proteinase inhibitors on digestive proteinases and growth of the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C: Toxicol. Pharmacol. 134, 481–490 (2003).

Lemos, F. J. A., Campos, F. A. P., Silva, C. P. & Xavier-Filho, J. Proteinases and amylases of larval midgut of Zabrotes subfasciatus reared on Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) seeds. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 56, 219–227 (1990).

Jha, A. N., Srivastava, C. & Dhar, S. Resistance in wheat genotypes to rice (Oryza sativa) weevil (Sitophilus oryzae). Indian J. Agric. Sci. 82, 1093–1095 (2012).

Arve, S. S., And, S. M. & Patel Varietal susceptibility of wheat grains against rice weevil, Sitophilus oryzae L. Trends Biosci. 7, 925–934 (2014).

Dobie, P. The laboratory assessment of the inherent susceptibility of maize varieties to post-harvest infestation by Sitophilus Zeamais Motsch. J. Stored Prod. Res. 10, 183–197 (1974). Coleoptera, Curculionidae.

Gowda, G. B. et al. Physico-chemical characteristics of rice (Oryza sativa L.) grain imparting resistance and their association with development of rice weevil, Sitophilus oryzae (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Environ. Sustain. 2, 369–379 (2019).

Mehta, V. & Kumar, S. Relative susceptibility and influence of different wheat cultivars on biological parameters of Sitophilus oryzae L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 41, 653–661 (2021).

Ahmed, A. G. et al. Recent Research Advances in Biology Vol. 2. (Book Publisher International (a part of SCIENCEDOMAIN International), (2020). https://doi.org/10.9734/bpi/rrab/v2.

Nawrot, J. et al. The effect of wheat grain composition, cuticular lipids and kernel surface microstructure on feeding, egg-laying, and the development of the granary weevil, Sitophilus granarius (L). J. Stored Prod. Res. 46, 133–141 (2010).

Prasad, G. S. et al. Resistance in sorghum to Sitophilus oryzae (L.) and its association with grain parameters. Phytoparasitica 43, 391–399 (2015).

Sergio, O. & Serna-Saldivar Cereal Grains: Laboratory Reference and Procedures Manual (CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2012).

Kordan, B., Nietupski, M., Ludwiczak, E., Gabryś, B. & Cabaj, R. Selected Cultivar-Specific parameters of wheat grain as factors influencing intensity of development of grain weevil Sitophilus granarius (L). Agriculture 13, 1492 (2023).

Zheng, X. Q. et al. Screening the cultivar and processing factors based on the flavonoid profiles of dry teas using principal component analysis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 67, 29–37 (2018).

Uarrota, V. G. et al. Metabolomics combined with chemometric tools (PCA, HCA, PLS-DA and SVM) for screening cassava (Manihot esculenta) roots during postharvest physiological deterioration. Food Chem. 161, 67–78 (2014).

Chanda, S. C., Islam, N., Tinne, F. J. & Sarwar, A. K. M. G. Screening of sesbania accessions based on seed germination and seedling biomass. Arch. Agric. Environ. Sci. 3, 137–142 (2018).

Arifuzzaman, M. et al. Screening of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes under drought stress conditions using multivariate analysis. Cereal Res. Commun. 48, 301–308 (2020).

Kavitha, K. & Reddy, K. D. Screening techniques for different insect pests in crop plants. Int. J. Bio-resour Stress Manag. 3, 188–195 (2012).

Suleman, N., Aslam, M. & Riaz, A. Evaluation of resistance in some wheat cultivars to Sitophilus oryzae L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) under laboratory conditions. Pak J. Biol. Sci. 3, 1029–1032 (2000).

Giga, D. P. Selection of oviposition sites by the Cowpea weevils Callosobruchus Rhodesianus and Callosobruchus maculatus. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 16, 145–149 (1995).

Verma, R. A., Yadav, P. & Sultana, N. Growth and development of Sitophilus oryzae on some wheat varieties. Indian J. Entomol. 74, 88–90 (2012).

Mebarkia, A., Rahbé, Y., Guechi, A., Bouras, A. & Makhlouf, M. Susceptibility of twelve soft wheat varieties (Triticum aestivum) to Sitophilus granarius (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Agric. Biol. J. N Am. 1, 571–578 (2010).

Demissie, G., Swaminathan, R., Ameta, O. P., Jain, H. K. & Saharan, V. Biochemical basis of resistance in different varieties of maize for their relative susceptibility to Sitotroga Cerealella (Olivier) (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). J. Stored Prod. Postharvest Res. 6, 1–12 (2015).

Shafique, M. & Chaudry, M. A. Susceptibility of maize grains to storage insects. Pakistan J. Zool. 39, 77 (2007).

Ajao, S. K., Popoola, K. O., Mande, S. & Togola, A. Resistance levels of selected rice genotypes to Sitophilus oryzae L. and Rhyzopertha dominica F. infestations. Zoologist. 17, 39–46 (2020).

Bhanderi, G. R., Radadiya, G. G. & Patel, D. R. Screening of sorghum genotypes against rice weevil (Sitophilus oryzae L). Int. J. Agric. Sci. 11, 93–98 (2015).

Badii, K. B., Asante, S. K. & Adarkwa, C. Varietal differences in the susceptibility of new rice for Africa (Nerica) to Sitophilus oryzae L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Afr. J. Agric. Res. 8, 1375–1380 (2013).

Bamaiyi, L. J., Dike, M. C. & Onu, I. Relative susceptibility of some sorghum varieties to the rice weevil, Sitophilus oryzae L. (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J. Entomol. 4, 387–392 (2007).

Tongjura, J. D. C., Amuga, G. A. & Mafuyai Laboratory assessment of the susceptability of some varieties of Zea Mays infested with Sitophilus zeamais, motsch. (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) in jos, plateau state, Nigeria. Sci. World J. 5, (2010).

Sinha, R. N., Demianyk, C. J. & Mckenzie, R. I. H. Vulnerability of common wheat cultivars to major stored-product beetles. Can. J. Plant. Sci. 68, 337–343 (1988).

Soujanya, P. L., Sekhar, J. C. & Kumar, P. O. Physical and biochemical changes in stored maize due to infestation of Sitophilus oryzae L. Madras Agric. J. 100, 187–189 (2013).

Aly, M. F. K. & Ali, A. M. Evaluation of certain Egyptian wheat cultivars against rice weevil, Sitophilus oryzae (L.) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) using biochemical and biophysical traits. J. Phytopathol. Pest Manag. 6, 54–65 (2019).

Liu, X., Zhang, S., Shan, X. & Zhu, Y. G. Toxicity of arsenate and arsenite on germination, seedling growth and amylolytic activity of wheat. Chemosphere 61, 293–301 (2005).

Piasecka-Kwiatkowska, D., Nawrot, J., Zielińska-Dawidziak, M., Gawlak, M. & Michalak, M. Detection of grain infestation caused by the granary weevil (Sitophilus granarius L.) using zymography for α-amylase activity. J. Stored Prod. Res. 56, 43–48 (2014).

Kumar, S., Abedin, M. M., Singh, A. K. & Das, S. Role of phenolic compounds in plant-defensive mechanisms. in Plant Phenolics in Sustainable Agriculture 517–532Springer Singapore, Singapore, (2020).

Lattanzio, V., Lattanzio, V. M. T. & Cardinali, A. Role of phenolics in the resistance mechanisms of plants against fungal pathogens and insects. in Phytochemistry Advances in Research (ed Imperato, F.) 23–67 (Research Signpost, Trivandrum, India, (2006).

Ramputh, A., Teshome, A., Bergvinson, D. J., Nozzolillo, C. & Arnason, J. T. Soluble phenolic content as an indicator of sorghum grain resistance to Sitophilus oryzae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). J. Stored Prod. Res. 35, 57–64 (1999).

Chi, Y. H. et al. Cowpea bruchid midgut transcriptome response to a soybean cystatin – costs and benefits of counter-defence. Insect Mol. Biol. 18, 97–110 (2009).

Fabres, A. et al. Comparative performance of the red flour beetle Tribolium castaneum (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) on different plant diets. J. Pest Sci. 87, 495–506 (2014).

Franco, O. L., Rigden, D. J. & Melo, F. R. Grossi-de-Sá, M. F. Plant α-amylase inhibitors and their interaction with insect α-amylases: structure, function and potential for crop protection. Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 397–412 (2002).

Nemati-Kalkhoran, M., Razmjou, J., Borzoui, E. & Naseri, B. Comparison of life table parameters and digestive physiology of Rhyzopertha Dominica (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae) fed on various barley cultivars. J Insect Sci 18, (2018).

Warchalewski, J. R., Gralik, J., Winiecki, Z., Nawrot, J. & Piasecka-Kwiatkowska, D. The effect of wheat α-amylase inhibitors incorporated into wheat-based artificial diets on development of sitophilus granarius L., tribolium confusum duv., and ephestia Kuehniella Zell. J. Appl. Entomol. 126, 161–168 (2002).

Mirnezhad, M. et al. Metabolomic analysis of host plant resistance to thrips in wild and cultivated tomatoes. Phytochem Anal. 21, 110–117 (2010).

Gayacharan et al. Understanding genetic variability in the Mungbean (Vigna radiata L.) gene pool. Ann. Appl. Biol. 177, 346–357 (2020).

ICAR- Indian Agricultural Research Institute. Annual Report. (2023).

Gawdiya, S. et al. Field screening of wheat cultivars for enhanced growth, yield, yield attributes, and nitrogen use efficiencies. Agronomy 13, 2011 (2023).

Todkar, L. et al. Introgression of drought tolerance QTLs through marker assisted backcross breeding in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Indian J. Genet. Plant. Breed 80, (2020).

Jat, A. et al. Genetic variability, heritability and diversity for yield contributing traits in reference varieties of wheat. Indian J. Plant. Genet. Resour. 31, 11 (2018).

Ram, H. & Gupta, N. Productivity, yield attributes and phenology of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under different sowing environments under central Punjab. J. Wheat Res. 8, 34–38 (2016).

Sharma, A. et al. Resurrection of wheat cultivar PBW343 using Marker-Assisted gene pyramiding for rust resistance. Front Plant. Sci 12, (2021).

Chattopadhyay, N., Mandal, R., Roy, A., Bhattacharya, P. M. & Chowdhury, A. K. Assessment of wheat genotypes based on genotype-by-environment interaction for durable resistance to spot blotch disease in hot spot. Cereal Res. Commun. 50, 95–102 (2022).

Singh, D. P. et al. Spot Blotch Resistance in Wheat (Triticum aestivum) and Triticale. (2017). https://iiwbr.org.in/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Wheat-Barley-Newsletter-V.111-2017.pdf.

Mishra, T. L. P., Prakasha, A. N., Kaushal, T. L. & Dubey, V. G. K. Validation of Lr24 in some released bread wheat varieties and its implications in leaf rust resistance breeding and deployment in central India. Indian Phytopath 67, (2014).

Gupta et al. Wheat varieties notified in India since. (1965). https://www.aicrpwheatbarleyicar.in/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/wheat-varieties-notified-in-india.pdf (2018).

Meena, V. K. et al. Elucidating molecular diversity in spring wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) under terminal heat stress environment using morpho-physiological traits and SSR markers. Indian J. Genet. Plant. Breed. 82, 47–55 (2022).

Gupta, V. et al. AMMI and GGE biplot analysis of yield under terminal heat tolerance in wheat. Mol. Biol. Rep. 50, 3459–3467 (2023).

Sood, N. et al. Evaluating the performance of bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genotypes for terminal heat tolerance. IJAEB 10, 295 (2017).

Solomon, M. E. Control of humidity with potassium hydroxide, sulphuric acid, or other solutions. Bull. Entomol. Res. 42, 543–554 (1951).

Kumar Singh, A., Kumar, K. & Kumar, S. & Arun Kumar singh, C. Taxonomic redescription of the rice weevil (Sitophilus oryzae). J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem 1 (2018).

Nwana, I. E. & Akibo-Betts, D. T. The resistance of some rice varieties to damage by Sitophilus Zeamais during storage. Trop. Stored Prod. Inf. 4, 10–15 (1982).

Soumia, P. S., Srivastava, C., Dikshit, H. K. & Guru Pirasanna Pandi, G. Screening for resistance against pulse beetle, Callosobruchus analis (F.) in Greengram (Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek) accessions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. India Sect. B Biol. Sci. 87, 551–558 (2017).

Howe, R. W. A parameter for expressing the suitability of an environment for insect development. J. Stored Prod. Res. 7, 63–65 (1971).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Somogyi, M. Notes on sugar determination. J. Biol. Chem. 195, 19–23 (1952).

McCready, R. M., Guggolz, J., Silviera, V. & Owens, H. S. Determination of starch and amylose in vegetables. Anal. Chem. 22, 1156–1158 (1950).

Bernfeld, P. [17] amylases, α and β. Methods Enzymol. 1, 149–151 (1955).

Malik, C. P. & Singh, M. B. Plant Enzymology and Histoenzymology (Kalyani, 1980).

Kotkar, H. M., Sarate, P. J., Tamhane, V. A., Gupta, V. S. & Giri, A. P. Responses of midgut amylases of Helicoverpa armigera to feeding on various host plants. J. Insect Physiol. 55, 663–670 (2009).

Anson, M. L. The Estimation of pepsin, trypsin, papain, and cathepsin with hemoglobin. J. Gen. Physiol. 22, 79–89 (1938).

Folin, O. & Ciocalteau, V. Enzymatic assay of protease using casein as a substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 73, 627–650 (1929).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Pusa Campus, New Delhi, for providing the necessary facilities for the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.S.A., C.S. Conceptualization, Methodology, Data duration, Software, P.S.A., S.S. Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing- Original draft preparation and Reviewing. P.S.A., S.R, and H.V.R. Methodology, Editing and Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arya, P.S., Srivastava, C., Rajna, S. et al. Physicochemical grain properties of wheat cultivars and insect biology drive resistance to Sitophilus oryzae L.. Sci Rep 15, 35308 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19299-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19299-7