Abstract

Traditional Chinese opera costumes are vital carriers of intangible cultural heritage, embodying intricate craftsmanship, symbolic aesthetics, and cultural narratives. However, conventional pedagogy struggles to convey their complexity and cultural depth due to limitations in static, lecture-based teaching methods. This study proposes an immersive Virtual Reality (VR)-based teaching model that integrates high-fidelity 3D modeling, semantic annotation, and real-time rendering optimization—specifically Level of Detail (LOD) and Occlusion Culling (OC)—to enhance the design education and cultural transmission of traditional Chinese opera costumes. A controlled experiment involving 80 undergraduate students was conducted to compare the VR-based model with traditional teaching methods across five dimensions: learning effectiveness, user experience, cultural understanding, technological adaptability, and instructional interaction. Results demonstrated that the VR-based approach significantly improved educational outcomes, particularly in interactive engagement and practical performance, while maintaining high rendering efficiency and visual fidelity. This work contributes a technically optimized, pedagogically grounded framework for integrating immersive technology into cultural heritage education, offering a scalable solution for revitalizing intangible traditions in the digital era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditional Chinese opera, as a comprehensive form of performing art that integrates music, dance, literature, and costume, represents a rich repository of China’s intangible cultural heritage. Among its various elements, opera costumes serve not only as aesthetic expressions but also as vital cultural symbols that convey character identity, social status, and narrative function1. However, with the acceleration of modernization and the gradual fading of traditional art forms from everyday life, the preservation and transmission of opera costume knowledge face significant challenges—particularly in the field of education, where outdated teaching methods often limit students’ ability to engage deeply with such cultural content2.

Conventional instructional approaches to opera costume design—typically relying on static images, textbooks, and lecture-based formats—struggle to capture the dynamic and experiential nature of this traditional art. These methods often fail to cultivate students’ cultural sensitivity or to foster the practical design skills required to understand the intricate craftsmanship and symbolic meanings embedded in opera costumes. In response to these limitations, there is a growing need for innovative pedagogical models that not only preserve the authenticity of traditional culture but also resonate with the expectations and learning styles of digital-native students3.

Recent advancements in immersive technologies, particularly VR, have opened new possibilities for reimagining cultural heritage education. VR has the capacity to create lifelike, interactive, and three-dimensional environments that simulate real-world experiences, making it a powerful tool for engaging learners and enhancing comprehension4. When applied to opera costume design education, VR can allow students to explore costume details, understand cultural context, and participate in virtual design practices in ways that traditional methods cannot replicate. Moreover, VR enables personalized, exploratory learning paths and fosters a deeper emotional and cognitive connection with cultural content.

To support these immersive experiences in complex virtual environments, the integration of advanced optimization techniques such as Level of Detail (LOD) and Occlusion Culling (OC) has become increasingly important. These methods improve system responsiveness and rendering efficiency, allowing users to interact smoothly with richly detailed 3D costume models without compromising visual fidelity. By incorporating LOD and OC into the VR teaching platform, this study ensures a technically robust foundation for delivering high-quality educational content in real time.

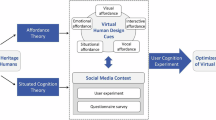

To design the VR-based platform for opera costume education, we draw on frameworks from cultural semiotics, immersion theory, and human–computer interaction (HCI) design. These theories guide our approach to the platform interface and interaction design. Cultural semiotics informs the way we present the symbolic meanings embedded in costume elements, ensuring that students understand the deeper cultural narratives. Immersion theory helps us to create an experience that fully engages students, making them feel emotionally and cognitively immersed in the learning process. Finally, HCI principles are applied to ensure the system is intuitive, user-friendly, and enhances the students’ interaction with the content. Together, these frameworks support the creation of a demonstration system that balances cultural depth with technical feasibility, providing an effective and engaging learning environment.

In this context, this study proposes an immersive teaching model for traditional Chinese opera costume design based on VR technology. The research aims to evaluate the effectiveness of this model compared to traditional teaching approaches, focusing on five key dimensions: learning effectiveness, user experience, cultural understanding, technological adaptability, and instructional interaction. By designing and implementing a controlled experimental procedure with undergraduate students, this study provides empirical evidence on how VR can enhance cultural education, promote the digital transmission of intangible heritage, and contribute to pedagogical innovation in the arts and design disciplines.

Literature review

Chinese opera costumes are a vital component of traditional theatrical performance and serve as visual carriers of cultural identity, aesthetic values, and symbolic meaning. Historically, the transmission of opera costume design knowledge has been based on master-apprentice teaching or studio-based instruction, emphasizing hands-on experience and oral guidance. In modern academic settings, however, the pedagogy often relies heavily on lecture-based delivery, textbook illustrations, and historical case studies. While these methods are valuable for preserving theoretical knowledge, they tend to be static and lack engagement, making it difficult for students to develop practical skills or appreciate the cultural depth of opera costumes5.

The application of VR in cultural heritage and design education has rapidly expanded in recent years. Liu and Sutnavivat (2024) discussed how traditional exhibition methods fail to meet contemporary visitor expectations and argued that immersive technology helps blur the boundary between virtual and real, enhancing visitor engagement6. Case studies in intangible cultural heritage education further demonstrate the effectiveness of VR. Selmanović et al. (2020) developed a VR-based experience to preserve the bridge-diving tradition of Stari Most in Bosnia and Herzegovina7. The application integrated narrative storytelling, interactive quizzes, and virtual environments. Results showed that participants gained a deeper cultural understanding and emotional connection, highlighting VR’s potential in preserving nonmaterial practices.

Despite the growing body of work, few studies have examined the technical challenges of rendering complex 3D content and supporting large-scale user interaction in VR-based education. For instance, developers in architectural visualization have pointed out that directly importing high-fidelity 3D models into VR environments—especially those with dynamic lighting and dense geometry—can easily exceed device capabilities if not properly optimized. This insight underscores the importance of incorporating graphics performance strategies in educational VR systems.

Two well-established techniques in computer graphics—LOD and OC—provide effective means to overcome performance bottlenecks in educational VR involving complex 3D models and substantial user interaction. For example, Zhang (2024) investigated high‑performance computing optimizations for real-time rendering in game engines such as Unity and Unreal, explicitly highlighting LOD management and OC as critical methods to enhance visual quality while reducing GPU load and overall latency in VR applications8. Casado-Coscolla et al. (2023) addressed challenges of rendering massive indoor point clouds in VR, combining a visibility map (a form of OC) with hierarchical LOD-like point‑cloud structures to boost rendering efficiency without compromising visual fidelity in immersive environments9.

In LOD systems, models are represented at multiple resolutions, and the rendering pipeline dynamically selects the appropriate level based on viewer distance or screen size, significantly reducing geometric complexity while preserving perceptible detail. For instance, GPU-accelerated LOD construction techniques, such as those introduced by Li (2023), enable streaming of point cloud data with octree-based LOD updates in real time—achieving rates of up to 1 billion points per second on high-end hardware—thereby making interactive high-fidelity VR feasible10.

OC complements LOD by preventing the rendering of objects that are blocked from the user’s view. Research on combined LOD–occlusion schemes, Dong and Peng (2023) shows that low-detail representations can be used to drive occlusion queries, dramatically reducing frame-by-frame rendering cost with minimal loss in visible quality11. Schutz et al. (2023) present a GPU-accelerated approach for real-time LOD generation of point clouds, demonstrating substantial improvements in rendering performance and responsiveness in immersive environments such as VR, compared to traditional CPU-based methods12.

Despite the proven benefits of LOD and OC in gaming and simulation contexts, their adoption in educational VR—particularly for cultural heritage applications—remains limited. Existing VR-based educational platforms often emphasize visual immersion and storytelling but neglect the underlying computational demands of high-fidelity, real-time rendering13. As a result, many systems struggle to support large-scale, detail-rich content such as traditional opera costumes, which involve intricate textures, layered materials, and dynamic user interaction.

This study addresses this shortcoming by incorporating GPU-optimized LOD strategies and occlusion-aware rendering pipelines into a VR teaching framework tailored for traditional Chinese opera costume design. Unlike prior applications that focus solely on visual experience, the proposed model balances immersive cultural education with real-time system performance. It tackles two key challenges concurrently: delivering authentic and interactive cultural experiences, and ensuring stable, responsive rendering of complex 3D assets in multi-user learning environments. By grounding its design in both educational theory and state-of-the-art graphics optimization research, this work contributes a scalable and pedagogically sound solution for immersive heritage instruction.

Methodology

Development and optimization of VR systems

The VR teaching system developed in this study employs advanced 3D modeling techniques to authentically reproduce the intricate details and symbolic meanings of traditional Peking opera costumes. To ensure high performance and deliver a truly immersive experience, the system integrates two key technological innovations: OC and LOD management14.

OC is a technique designed to enhance rendering efficiency by intelligently identifying and eliminating objects that are not visible in the user’s current field of view, thereby reducing computational overhead15. In conventional 3D rendering workflows, all objects are rendered regardless of their visibility, which results in a substantial amount of unnecessary processing. By implementing OC, the system dynamically analyzes the spatial relationship between objects and the viewer’s perspective, automatically filtering out elements obscured by other objects16. As a result, only the objects actually visible to the user are rendered, significantly improving rendering speed and system performance while minimizing resource waste. This approach is particularly effective in complex virtual scenes, where OC can dramatically reduce computational load and enable smooth, uninterrupted user experiences.

LOD management further optimizes rendering by adjusting the geometric complexity of models based on their distance from the user. Specifically, LOD dynamically switches between multiple versions of a model, displaying lower-resolution geometry for distant objects and higher-resolution geometry for those closer to the user17. This technique reduces rendering demands without compromising visual fidelity. In a VR context, LOD not only ensures efficient performance but also enables users to closely inspect costume details and scene elements with visual clarity18, thereby enhancing both immersion and realism. The underlying principles are illustrated in Eq. 1 and Fig. 1.

The combined workflow is as follows:

In the rendering pipeline, Frustum Culling (FC), OC, and LOD Selection are key steps for optimizing rendering performance. FC is the first step, where objects outside the view frustum are culled, reducing unnecessary rendering load. Next, OC further optimizes performance by determining which objects are hidden behind others and excluding those that are not visible. Finally, LOD Selection dynamically chooses the appropriate LOD for objects based on their distance from the viewer, improving rendering efficiency while maintaining visual quality19. This sequence determines the execution priority in the pipeline, ensuring reduced computational resource usage while preserving the quality of the render.

To optimize the rendering process in VR environments, let us consider a scene containing N distinct 3D objects, which can be denoted as20:

Each object Oi is characterized by its spatial coordinates, shape, and texture attributes:

where Pi represents the object’s position in three-dimensional space, Gi defines its geometric structure, and Ti denotes its texture and material properties21.

The VR system computes a visible subset of objects from the user’s current viewpoint, indicated as:

Determining this visible set V is central to efficient rendering. Instead of processing all N objects indiscriminately, the system applies OC to eliminate non-visible items, reducing computational overhead. Formally, if an object Oi is entirely blocked by another object Oj from the camera’s perspective, then Oi \(\notin\)V.

To further enhance performance, LOD management is introduced. Define LOD(Oi, d) as the geometric complexity level of object Oi rendered at a distance d from the viewer. The system dynamically selects an appropriate LOD based on proximity, as follows22:

Here, \({G}_{i}^{high}\), \({G}_{i}^{medium}\), and \({G}_{i}^{low}\) represent high-, medium-, and low-resolution mesh variants of \({O}_{i}\) , respectively. By adapting model complexity according to the user’s viewpoint distance, rendering efficiency is significantly improved without compromising visual quality.

Integrating occlusion culling and LOD techniques within the VR architecture enables real-time optimization, allowing for high-fidelity rendering even in densely populated virtual scenes. This dual strategy ensures a balance between immersive visual realism and system responsiveness, forming the technical foundation for the immersive opera costume teaching platform developed in this study.

Construction of a virtual reality–based peking opera costume platform

Data acquisition and digital processing

Data collection

To accurately replicate the form, materiality, and cultural connotations of Peking opera costumes, this study employed a range of advanced data acquisition techniques aimed at capturing the fine details, historical background, and symbolic meanings of each garment. The data collection process was divided into three primary components: image acquisition, 3D structural capture, and semantic information gathering. Each component was designed to ensure high precision while preserving the costumes’ cultural significance and artistic value to the greatest extent possible23.

-

(1)

Image acquisition

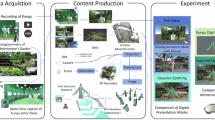

Image acquisition serves as a foundational process in the digital reconstruction of Peking opera costumes, enabling the detailed capture of intricate patterns, embroidery, fabric textures, and color schemes. As shown in Fig. 2, four representative examples of traditional opera costumes were photographed using high-resolution cameras from multiple angles. These garments include various types such as ceremonial robes, female floral costumes, and scholar attire, each exhibiting unique design characteristics.

The front-facing shots in the figure illustrate the fidelity of pattern acquisition, which plays a crucial role in subsequent texture mapping and color calibration. To ensure clarity and depth, the costumes were photographed under diverse lighting conditions to reveal fabric sheen and contrast. Furthermore, photogrammetry techniques were applied to these multi-angle images to reconstruct accurate 3D models, thereby enabling a transition from 2D visual data to immersive digital assets. Each costume in Fig. 2 corresponds to a successfully reconstructed 3D mesh, verifying the effectiveness of this acquisition process in preserving surface detail and ornamental elements24.

-

(2)

3D structural capture

While image acquisition addresses surface detail, accurate 3D structural capture ensures that the geometric and volumetric integrity of costume accessories is faithfully preserved. As illustrated in Fig. 3, six decorative components—including headgear, belts, floral hairpieces, and embroidered trims—were scanned using high-precision 3D laser scanners and structured light scanning systems. These tools enabled the recovery of minute textural and morphological features essential for high-fidelity virtual reconstructions.

In particular, Fig. 3 demonstrates how structured light was employed to capture objects with complex geometry and reflectivity. These objects exhibit substantial variation in depth and surface reflectance, making them ideal test cases for evaluating scan precision. The resulting 3D data not only captured microstructural details like stitching and embroidery relief but also ensured physical realism when rendered within VR environments25.

-

(3)

Semantic information collection

In the study of Peking opera costumes, semantic information collection extends beyond capturing visual and structural data; it involves documenting and interpreting the cultural meanings, historical contexts, and symbolic values embedded in each garment. Through expert annotation and archival research, the system systematically records the cultural attributes, symbolic meanings, and usage scenarios of each costume26. For example, specific colors, motifs, and accessories in Peking opera often carry particular symbolic significance—dragon and phoenix patterns typically represent imperial authority or nobility, while certain colors are associated with specific character archetypes (e.g., red often denotes loyalty and bravery).

By integrating computer vision techniques with AI-driven semantic analysis, the system can automatically detect symbols and identifiers on the garments and tag them with relevant cultural, historical, and functional metadata27. This ensures that each virtual costume is not merely a geometric replica but also a rich cultural artifact embedded with layers of meaning. This process greatly enhances the educational and exhibition experience by enabling users to better understand and appreciate the deeper significance of Peking opera costumes within the virtual environment.

Digital processing workflow

To effectively reconstruct and present the intricate details and cultural significance of Peking opera costumes, this study adopts a comprehensive and efficient digital processing workflow. This workflow encompasses several key stages, including 3D modeling, texture mapping, data format conversion, and performance optimization, aiming to ensure both high visual fidelity and smooth user interaction within the VR platform.

-

(1)

3D modeling and geometric reconstruction

3D modeling and geometric reconstruction are central to the digitization of Peking opera costumes. Based on acquired imagery and structural data, detailed 3D models were created using advanced software such as Blender or Maya. By integrating multi-angle photography with laser scanning data, accurate reconstructions were achieved that reflect not only the garments’ basic forms and dimensions but also the intricate details of embroidery, accessories, and fabric draping28. The modeling process combined automated processing with manual refinement to ensure precision in detail reproduction, meeting the needs of immersive display and interaction.

-

(2)

Texture mapping and material definition

Texture mapping and material definition are crucial for enhancing the visual realism of costume models. High-resolution photographs obtained from image acquisition were applied as textures to accurately replicate the appearance of the original garments. Elements such as fabric textures, embroidery patterns, and metallic reflections were faithfully reproduced. Material properties—including glossiness, transparency, and roughness—were defined using Physically Based Rendering (PBR) techniques to simulate realistic light-material interactions29. These enhancements allow the virtual costumes to not only match real-world garments in form, but also in visual impact.

-

(3)

Data format conversion and performance optimization

Upon completion of 3D modeling and texturing, the assets were converted into formats compatible with VR platforms, such as .obj, .fbx, or .glb. During this phase, performance optimization was conducted to ensure smooth operation in real-time environments. This included reducing redundant polygons, simplifying high-detail meshes, employing LOD strategies, and compressing texture files to minimize system load30. These optimization techniques significantly lowered rendering overhead, improved runtime efficiency, and ensured a seamless user experience.

-

(4)

Database integration and semantic annotation

Integrating the digital assets into a structured database and assigning semantic annotations was key to enhancing the educational value of the VR system. Each costume was linked to a database entry containing its 3D model, texture resources, and associated cultural and historical metadata31. Detailed annotations were added, covering role types, symbolic meanings, and usage contexts in Peking opera. These metadata not only aid user understanding but also support interactive exploration. Users can access contextual information through intuitive interactions such as clicking or touching, further enriching the immersive and educational experience32.

To enhance clarity and transparency, Fig. 4 presents the overall digital processing workflow, explicitly illustrating how LOD and OC modules are integrated into the rendering pipeline and interact with the asset preparation and runtime display systems. This flowchart demonstrates how input data (2D images, 3D scans, and cultural metadata) are transformed into semantically annotated, performance-optimized, and visually rich assets within the VR teaching platform.

Platform interface and interaction design

The platform’s interface and interaction design serve as a critical bridge between technological implementation and user experience. To ensure a smooth and natural user journey while presenting rich cultural content, the platform adopts a design philosophy based on immersive experience and progressive knowledge acquisition, resulting in a visually appealing and functionally logical multimodal interactive environment (see Fig. 5).

Schematic diagram of VR platform interface (All models were created using Autodesk 3ds Max 2024 (https://www.autodesk.com/products/3ds-max/overview) and rendered with the built-in Arnold renderer to illustrate spatial configurations and material applications.)

Unlike traditional graphical user interfaces (GUIs), the platform employs an “environment-as-interface” paradigm. The virtual environment itself becomes the primary interface, enabling users to escape the limitations of conventional UI frameworks and fully immerse themselves in the virtual space33. The system is structured into three layers, guiding users from visual perception to interactive engagement:

-

(1)

Scene layer

This layer provides the overall design of the virtual environment, recreating various historical and cultural settings using high-quality 3D modeling. The platform supports multiple scene types—such as traditional opera stages, imperial courts, and historical streets—allowing users to explore how costumes function in different contexts34. Dynamic lighting and advanced material rendering techniques enhance the authenticity and atmosphere of each scene. Scenarios can be flexibly adapted to suit different educational and experiential objectives.

-

(2)

Functional layer

The functional layer emphasizes a clean and intuitive interface that enables users to easily access various tools without disrupting immersion.

Floating Toolbar: A semi-transparent floating menu grants access to functions such as costume browsing, scene switching, and audio settings. The minimalist design ensures rapid navigation without interfering with the viewing experience.

View control buttons: Buttons for zooming, rotating, and manipulating 3D models are positioned unobtrusively on the top or right side of the interface, allowing intuitive interaction via clicks or drags35.

Real-time feedback display: A corner panel displays contextual information such as the currently selected costume or scene, with quick access to switch views, helping users stay oriented and engaged.

-

(3)

Interaction feedback layer

The interaction feedback layer enhances user engagement through eye tracking, gesture recognition, and multi-sensory feedback.

Eye tracking: When a user’s gaze focuses on an object or detail, the system highlights relevant cultural or historical information, providing contextual knowledge without requiring manual input.

Gesture recognition: Users can perform natural gestures—such as pinch to zoom or rotate—to manipulate 3D models, making the interaction intuitive and expressive36.

Audio and haptic feedback: Subtle sound effects respond to user interactions (e.g., the rustle of silk or metallic jingles when a costume is touched), enriching the sensory immersion.

Through this innovative layered design, the platform delivers a culturally rich, visually detailed, and highly interactive learning experience. Users can intuitively explore cultural knowledge in an emotionally engaging virtual environment, making the learning process both meaningful and memorable.

Results

Performance testing of Peking opera costume models in a VR environment

This study aims to analyze the optimization effects of LOD and OC techniques on system performance in VR environments. To achieve this, a series of comparative experiments were designed, focusing on the differences in system load during model rendering under varying detail levels and OC strategies. The core objective of the research is to evaluate the potential of LOD and OC techniques in improving rendering efficiency.

The experiment utilized a standardized hardware and software configuration, loading multiple 3D model scenes, each with different detail reduction ratios and OC algorithms applied. Using a controlled variable approach, the original models, LOD-simplified models, and models with OC enabled were rendered separately37. Key performance metrics, including real-time FPS, rendering time, and polygon count, were recorded.

Evaluation of vertex count and triangle count

Six 3D models were chosen for evaluation: Models A, C, and E are the original, unsimplified meshes, representing high geometric complexity and corresponding to higher rendering loads. Models B, D, and F are the LOD-optimized versions of these models, with OC applied (Fig. 6).

By comparing the rendering performance of each original model with its LOD and OC-optimized counterpart, we can effectively assess the combined impact of LOD and OC in reducing resource consumption and improving rendering efficiency. The detailed results are provided in Table 1.

Table 1 presents the changes in the number of vertices and triangles between the original models and their simplified versions. All simplified models show significant reductions in both vertices and triangles, demonstrating the effectiveness of LOD techniques in reducing model complexity.

Specifically, Model A before simplification has 66,184 vertices and 124,241 triangles, indicating a high level of geometric complexity. After LOD simplification, Model B has 14,509 vertices and 19,139 triangles, showing a substantial reduction in complexity, which significantly reduces rendering load.

Model C before simplification has 62,254 vertices and 119,152 triangles, representing a similarly high geometric complexity. After simplification, Model D has 16,230 vertices and 29,632 triangles, which, while less simplified than Model B, still effectively reduces the model’s complexity.

Model E before simplification has 19,377 vertices and 35,787 triangles, reflecting relatively lower complexity. After simplification, Model F has only 4158 vertices and 5684 triangles, showing an extremely significant reduction, making it almost the simplest version of the model.

From the data in Table 1, it is clear that all simplified models show a reduction in both vertices and triangles, which effectively lowers the computational load during rendering, improving system performance38. The application of LOD techniques leads to a noticeable optimization in rendering efficiency, particularly for more complex models such as Models A and C, where LOD can significantly reduce the rendering burden.

Comparative analysis of rendering time

To comprehensively assess the combined impact of LOD and OC techniques on rendering time, each model was rendered 10 times independently to ensure data reliability and statistical validity. By comparing the rendering times of the original models with those optimized using LOD and OC, we are able to analyze the synergistic effect of both techniques in practical rendering scenarios39.

For the original models, the high geometric complexity led to significantly longer rendering times. Specifically, Model A, Model C, and Model E, with their larger number of vertices and triangles, required considerable computational resources, resulting in extended rendering times. However, when LOD and OC techniques were applied, the geometric complexity of the models was effectively reduced. Additionally, by using OC to eliminate the rendering of invisible objects blocked by others, further reductions in rendering time were achieved40.

In particular, Model B, Model D, and Model F exhibited significant improvements, with LOD reducing the number of vertices and triangles, while OC minimized the rendering of occluded geometry. The combined application of these techniques dramatically increased rendering efficiency. The experimental results demonstrate that the integration of LOD and OC not only shortened rendering times but also reduced memory usage and computational load, especially for more complex models.

Overall, the combination of LOD and OC techniques significantly enhanced rendering efficiency and optimized system performance. In large-scale scenes or on resource-constrained hardware, the joint application of these techniques provides a powerful solution for improving real-time rendering performance and reducing unnecessary computational work, making them essential for efficient rendering in VR systems41.

Figure 7 horizontal axis denotes the trial iteration number, and the vertical axis represents rendering time (ms). The plotted line graph clearly illustrates the change in rendering performance before and after LOD simplification, with the inclusion of OC further optimizing the results by reducing rendering time due to the elimination of occluded objects.

The data in the Table 2 illustrates the comparison of rendering times between the original models and their simplified counterparts, reflecting the effectiveness of LOD and OC techniques in optimizing rendering performance. Specifically, Model A has a rendering time of 264.4 ms, Model C has 233.6 ms, and Model E has 190.9 ms before simplification. As the geometric complexity of the models increases, the rendering time also increases, indicating that the original models, with a higher number of vertices and triangles, require more computational resources, resulting in longer rendering times.

After the application of LOD simplification and OC techniques, the rendering times are significantly reduced. Model B has a rendering time of 124.8 ms, a reduction of 139.6 ms compared to the original Model A; Model D takes 87.3 ms, 146.3 ms less than Model C; and Model F has a rendering time of 58.5 ms, a reduction of 132.4 ms compared to Model E. These results indicate that the combination of LOD simplification and OC techniques effectively reduces the computational demand during the rendering process, thereby improving rendering efficiency.

Overall, the rendering times of the simplified models are generally reduced by more than 50%, with particularly significant reductions observed in Model B and Model F. This demonstrates that LOD and OC techniques, by reducing the number of geometric details and eliminating the rendering of occluded objects, substantially optimize the rendering process. Therefore, the integration of LOD and OC not only enhances rendering performance but also effectively supports the improvement of real-time rendering efficiency in VR systems.

FPS comparison test

In the FPS test, each model was rendered 10 times before and after applying LOD and OC techniques to evaluate their effect on real-time rendering performance. The primary objective of this test was to assess how model simplification through LOD and the removal of occluded objects using OC could enhance the frame rate during rendering (Table 3).

Table 3 presents a comparison of FPS between the original models and their simplified counterparts, reflecting the optimization effects of LOD and OC techniques on real-time rendering performance.

Specifically, Model A has an FPS of 106.3, Model C has 105.0 FPS, and Model E has 98.1 FPS before simplification. It is evident that the original models have lower FPS due to their higher geometric complexity. The increased computational load required by high-complexity models leads to longer rendering times and reduced real-time performance.

After applying LOD and OC techniques, the FPS values for the simplified models show significant improvements. Model B achieves 118.2 FPS, an increase of 11.9 FPS compared to Model A, a 11.2% improvement; Model D has 115.6 FPS, 10.6 FPS higher than Model C, representing a 10.1% improvement; Model F reaches 109.9 FPS, 11.8 FPS higher than Model E, with a 12.0% improvement. These results demonstrate that the combined application of LOD and OC effectively reduces computational load, thereby improving rendering performance.

Upon further analysis, the FPS of the simplified models is consistently over 10% higher than that of the original models. This confirms the effectiveness of LOD in reducing geometric complexity and computational load, while OC contributes to further optimizing performance by eliminating unnecessary rendering calculations of occluded objects.

In addition, testing both the maximum and minimum FPS helps assess the performance fluctuations during the rendering process and ensures the model’s stability across different rendering scenarios. Table 4 shows the maximum FPS and minimum FPS for each model before and after simplification over 10 rendering trials.

Before simplification, Model A had a maximum FPS of 114 and a minimum FPS of 96.8, Model C had a maximum FPS of 112 and a minimum FPS of 99.5, and Model E had a maximum FPS of 106 and a minimum FPS of 94. It is evident that both the maximum and minimum FPS fluctuated before simplification, indicating instability in rendering performance due to increasing geometric complexity.

After applying LOD and OC techniques, Model B reached a maximum FPS of 127.0 and a minimum FPS of 113.0, Model D had a maximum FPS of 123.0 and a minimum FPS of 109.0, and Model F had a maximum FPS of 117.0 and a minimum FPS of 104.0. Simplified models not only showed an increase in maximum FPS but also demonstrated a reduction in performance fluctuations, with a notable improvement in the minimum FPS, indicating enhanced rendering stability.

Overall, the application of LOD and OC techniques effectively improved rendering performance, reduced FPS fluctuations, and especially showed a significant improvement in minimum FPS.

In conclusion, the integration of LOD and OC not only significantly enhances FPS but also optimizes real-time rendering smoothness and system responsiveness, making it particularly suitable for VR applications requiring high-performance rendering.

Evaluation of the VR-based teaching model for traditional Chinese opera costume design

Testing procedures and process

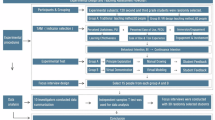

This study aims to explore the effectiveness of a VR-based teaching model for traditional Chinese opera costume design. By comparing it with conventional instructional methods, the research evaluates differences between the two approaches across five key dimensions: learning effectiveness, user experience, cultural understanding, technological adaptability, and instructional interaction42. To achieve this, a rigorous testing procedure was designed to ensure the reliability of the data and the accuracy of the analytical results (see Fig. 8).

The first step involved preparatory work. A total of 80 undergraduate participants were recruited through campus announcements and social media platforms. The sample was carefully selected to ensure diversity across gender, age, academic background, and prior VR experience. The recruitment process maintained a balanced gender ratio and distributed participants across various VR experience levels to ensure representativeness. Participants were then asked to complete a pre-survey questionnaire collecting demographic information and prior exposure to VR, which served as a reference for subsequent analyses. Relevant evaluation indicators were also selected at this stage.

The second step was pre-experimental preparation. During this phase, all participants received a brief training session on the use of VR equipment. The training covered basic operations such as wearing the VR headset, navigating the virtual environment, and interacting with virtual instructional content. Additionally, the research team provided a detailed explanation of the experimental procedure and task requirements to ensure participants clearly understood their roles and objectives. A short trial session followed the training to confirm that each participant could successfully operate the system and complete basic tasks in the virtual environment43.

The formal experimental phase involved a comparative study between two groups: one following a traditional teaching model, and the other utilizing the VR-based model. Each group participated in a 2 h instructional session, which included theoretical lectures on the fundamentals of opera costume design, analysis of design cases, and hands-on practice. In the traditional teaching group, the session consisted of teacher-led lectures supported by textbooks and printed illustrations. In contrast, the VR group engaged with the learning materials through a virtual platform, experiencing costume design and cultural elements directly in a 3D environment. Both groups were assigned identical learning tasks to ensure consistency for comparative analysis44.

Data were collected through three primary methods: post-session questionnaires, classroom observation, and technical usage tracking. After each session, participants completed self-assessment questionnaires evaluating their learning experience, technological adaptability, and understanding of cultural content. Additionally, qualitative data were gathered through direct observation of student interactions, learning progress, and task completion. For the VR group, system-generated logs recorded technical usage metrics such as interaction time and device usage frequency, providing supplementary data for analysis.

In the final analysis phase, all collected data—including questionnaire responses, observational notes, and system logs—were subjected to statistical and qualitative analysis. Quantitative data were analyzed using SPSS software, employing t tests and other statistical methods to compare outcomes between the traditional and VR-based teaching models across the five dimensions mentioned above. Qualitative data were analyzed using content analysis to identify specific feedback and experiential differences between the two groups. Based on the results, the study evaluates the strengths and limitations of the VR-based teaching model and provides recommendations for its future optimization.

Through this comprehensive testing procedure, the study offers an in-depth assessment of the instructional effectiveness of different teaching models and provides empirical evidence for the broader application of VR technology in education.

Selection of evaluation indicators

In this study, five key indicators were selected to comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the VR-based teaching model for traditional Chinese opera costume design, compared to the conventional instructional approach. These indicators are: learning effectiveness, user experience, cultural understanding, technological adaptability, and instructional interaction. By comparing the performance of both teaching models across these dimensions, the study aims to provide insights for optimizing educational strategies.

-

(1)

Learning effectiveness

Learning effectiveness measures the extent to which students acquire knowledge of opera costume design under the two teaching models. In the traditional model, effectiveness is primarily gauged through comprehension of lectures and textbooks, with assessments typically conducted via written exams or assignments. In contrast, the VR-based model evaluates learning outcomes through students’ practical performance in virtual environments. For example, students are required to carry out costume design tasks such as styling, matching, and detail adjustments within the VR platform. This method provides a more direct and interactive way of assessing learning outcomes. While the traditional approach emphasizes theoretical knowledge, the VR-based model enhances hands-on skills and deepens engagement through experiential learning45.

-

(2)

User experience

User experience reflects students’ subjective perceptions of their learning process under each teaching model. In traditional classrooms, the experience is shaped by physical environment constraints and the teaching style of the instructor, which can limit comfort and engagement. In VR-based teaching, students benefit from heightened immersion and interactivity, with vivid visual and operational experiences that allow them to interact directly with virtual costume design elements. This increases both interest and participation. Using questionnaires and interviews, the study assesses student satisfaction and comfort levels to determine which model delivers a higher-quality learning experience.

-

(3)

Cultural understanding

This indicator evaluates students’ comprehension of the cultural background associated with Chinese opera costumes. In traditional settings, students learn through reading materials and teacher explanations, but the lack of sensory and experiential input can limit depth of understanding. The VR-based model, by contrast, immerses students in culturally rich environments that simulate the costume design process, often incorporating virtual displays and role-playing elements. These methods enhance cultural perception and foster a deeper appreciation of traditional values. The study compares the acquisition of cultural knowledge across both models to determine which method more effectively conveys cultural content46.

-

(4)

Technological adaptability

Technological adaptability assesses students’ ability to operate and engage with the tools required in each teaching mode. Traditional instruction requires minimal technological engagement, relying mainly on lectures and printed materials. The VR model, however, demands higher technical proficiency, as students must navigate VR environments, use head-mounted displays, and interact with virtual objects. By comparing students’ adaptability in both models, the study explores how differing levels of technical background affect student performance and identifies factors influencing their capacity to adapt to new technologies.

-

(5)

Instructional interaction

This indicator examines the quality and frequency of instructional interaction under each model. In traditional classrooms, interaction typically occurs between teachers and students through lectures, discussions, and demonstrations, which may be limited by class size and time constraints. VR-based teaching, on the other hand, fosters dynamic interactions between students and the virtual environment, as well as between students and instructors. The VR platform enables real-time feedback and multiple forms of engagement, enhancing students’ sense of participation. The study observes and compares interaction patterns across both models to assess which approach fosters more effective instructional communication.

By comparing these five indicators, this study offers a comprehensive evaluation of the strengths and limitations of the VR-based teaching model in Chinese opera costume design education, thereby providing a theoretical basis for future innovation and optimization in educational practices.

Participant information and demographics

This study employed a questionnaire-based survey to collect data from participants between March and June 2025. A total of 80 undergraduate students were recruited through in-person participation. The questionnaire employed a Likert scale to quantify participants’ perceptions, attitudes, and acceptance of the VR-based teaching model for Chinese opera costume design. The survey covered areas such as satisfaction with the VR experience, perceived technical usability, and evaluation of learning outcomes, aiming to capture a comprehensive understanding of students’ performance and feedback47. Statistical analyses were conducted across demographic characteristics such as gender, age, education level, and prior VR experience to ensure diversity and representativeness of the data.

The study was designed to compare the VR-based instructional approach with traditional teaching methods. Conventional Chinese opera costume design instruction relies on face-to-face lectures, illustrated textbooks, and hands-on practice, with a focus on the transmission of traditional craftsmanship and classical theory. While effective for conveying foundational knowledge, this method often lacks interactivity and immersion, which may limit student engagement and motivation.

In contrast, the VR-based teaching model offers an immersive learning experience, enabling students to engage with the design and cultural essence of Chinese opera costumes in a highly visual and interactive virtual environment. This approach allows students to gain a deeper, more intuitive understanding of the subject matter. It also enhances student participation and interactivity, while facilitating the detailed visualization of traditional cultural elements through VR technology. As a result, students not only grasp theoretical concepts but also apply them in practice within the virtual environment, achieving a more comprehensive and enriched learning experience.

In this study, participant selection was stratified based on gender, age, educational level, and prior VR experience (see Table 5).

First, in terms of gender, the sample was evenly split with 40 male and 40 female participants, ensuring a balanced gender distribution. Regarding age, participants were categorized into three groups: 20–21 years old (24 participants, 30%), 22–23 years old (40 participants, 50%), and 24 years old (16 participants, 20%). The majority of the participants (50%) were aged 22–23, representing the typical age range of undergraduate students. All participants were enrolled as undergraduate students, which ensured consistency in educational background and eliminated bias stemming from educational level differences.

In terms of VR experience, participants exhibited varying levels of familiarity with the technology: 45% had used VR once or less, 40% had experienced it 2–3 times, and 15% had used it four times or more. This distribution provided the study with data across different levels of prior experience, which facilitated the analysis of adaptability and learning effectiveness in VR-based instruction. By incorporating these demographic and experiential distinctions, the study offers a comprehensive examination of how learners with different backgrounds perceive and respond to the VR-based teaching model for Chinese opera costume design48.

Evaluation results

In this experimental survey, an in-depth analysis was conducted to compare the evaluation scores of the traditional teaching method and the VR-based instructional approach. A total of 80 valid questionnaires were collected, recording participants’ ratings across various instructional design attributes.

To ensure the reliability of the evaluation instrument, we conducted a Cronbach’s α analysis on the five-item questionnaire used in the post-session survey. Based on the responses from 80 participants, the analysis yielded a Cronbach’s α coefficient of 0.719, indicating acceptable internal consistency. According to widely accepted standards (α ≥ 0.70), the questionnaire demonstrates sufficient reliability to support further inferential statistical analyses.

First, the mean scores and standard deviations for each attribute under both teaching methods were calculated through descriptive statistical analysis. Subsequently, to determine whether the differences in scores were statistically significant, independent samples t tests were performed.

The results indicated that the VR-based teaching method—optimized with LOD and OC technologies—achieved significantly higher ratings compared to the traditional approach. Detailed results are presented in Fig. 9.

The evaluation results demonstrate that the VR-based method outperformed the traditional approach across all five assessment criteria (see Table 6).

In terms of learning effectiveness, the VR method received an average score of 4.00, compared to 3.10 for the traditional method—a difference of 0.90. This suggests that participants believed the VR method was more effective in helping them achieve their learning goals.

For user experience, the VR group scored an average of 4.20, while the traditional group scored 3.30, again showing a 0.90 difference. This indicates a more positive user experience with the VR approach, likely due to its immersive and interactive features.

Regarding cultural understanding, the VR method achieved a score of 3.87 versus 3.33 for the traditional method, reflecting a smaller yet meaningful difference of 0.53. This suggests that the VR model has a slight advantage in fostering cultural comprehension, potentially because of its ability to present content in a more vivid and engaging manner.

In terms of technological adaptability, the VR method received an average score of 4.17, compared to 3.33 for the traditional method—a difference of 0.83. This highlights the VR model’s strength in helping users quickly adapt to new technology.

Finally, for instructional interaction, the VR group scored 4.33, while the traditional group scored 3.23, revealing the largest difference at 1.10. This suggests that the VR method provides a higher quality of interaction, likely due to its capacity to enhance engagement among students, instructors, and instructional content.

Overall, the VR-based method consistently outperformed the traditional approach across all evaluation criteria, with particularly pronounced differences observed in instructional interaction and learning effectiveness.

Data analysis

Furthermore, the results of the independent samples t tests confirmed that the advantages of the VR method over the traditional approach were statistically significant across all indicators (see Table 7). A deeper analysis of these differences provides further insight into the specific strengths of VR technology in educational contexts.

In terms of learning effectiveness, the VR group scored 4.00 ± 0.69, while the traditional group scored 3.10 ± 0.61. The Cohen’s d was 1.32, with a 95% confidence interval of [0.55, 1.25], t = 5.14, and p < 0.001. This result indicates that VR not only delivers rich visual and interactive experiences but also effectively enhances students’ motivation and engagement. The immersive nature of VR allows learners to establish stronger connections with the learning content, thereby improving learning efficiency and depth of understanding. Such high levels of engagement and immersion make VR particularly effective for tasks that require deep conceptual understanding and repeated practice, offering a more impactful learning platform compared to traditional methods.

Regarding user experience, the VR group achieved a mean score of 4.20 ± 0.55, whereas the traditional group scored 3.30 ± 0.75. The Cohen’s d was 1.37, 95% CI [0.56, 1.24], t = 5.23, and p < 0.001. The interactivity and immersive quality provided by VR significantly enhanced the overall learning experience. Rather than passively receiving information, learners participated in a multisensory, interactive process. Real-time interaction through visual, auditory, and even tactile feedback made the learning experience more engaging, and improved memory retention and understanding. Compared to the static nature of traditional instruction, the dynamic interaction and immersive environment offered by VR greatly improved the quality of user experience.

In terms of cultural understanding, the VR group scored 3.87 ± 0.63, while the traditional group scored 3.33 ± 0.61. The Cohen’s d value was 0.86, 95% CI [0.21, 0.85], t = 3.34, and p < 0.010. Although this dimension showed a smaller gap relative to others, the difference was still statistically significant. Traditional teaching methods often rely on text and images, which may limit learners’ comprehensive perception of cultural context. In contrast, VR offers immersive experiences that allow students to “enter” virtual cultural settings and intuitively perceive the finer details and deeper meanings of traditional culture. This form of experiential learning fosters a more profound understanding of cultural content and enhances students’ cultural sensitivity and sense of identity.

For technological adaptability, the VR group scored 4.17 ± 0.46, compared to 3.33 ± 0.71 in the traditional group. The Cohen’s d was 1.39, 95% CI [0.52, 1.14], t = 5.39, and p < 0.001. The VR method demonstrated a clear advantage in this dimension. As students are increasingly accustomed to modern technological tools, the introduction of VR—a relatively novel technology—was met with high levels of interest and quick acceptance. This result indicates that students are not constrained by the limitations of traditional delivery methods; rather, VR has the potential to stimulate curiosity and facilitate rapid adaptation and mastery of new tools. By tightly integrating technical operation with learning tasks, VR creates an environment where students simultaneously engage in practice and knowledge acquisition, further enhancing learning outcomes.

In the area of instructional interaction, the VR group scored 4.33 ± 0.55, while the traditional group scored 3.23 ± 0.63. The Cohen’s d reached 1.87, with a 95% CI of [0.79, 1.40], t = 7.25, and p < 0.001. This represents the most substantial difference across all dimensions. Traditional teaching is often teacher-centered, with students in a relatively passive role and limited opportunities for interaction. VR, however, breaks through this constraint by enabling dynamic, multi-level interaction within virtual environments. Students are able to engage deeply with instructional content, as well as interact in real time with instructors and peers. This form of interaction significantly increases engagement and learner agency. Particularly in collaborative or hands-on tasks, VR fosters cooperation and communication among students, greatly enhancing both classroom interactivity and learning outcomes.

In conclusion, the advantages of the VR-based method across all evaluated dimensions are not incidental. The immersive experiences and interactive capabilities it offers contribute not only to improved learning performance but also to better user experience, deeper cultural comprehension, enhanced technological adaptability, and significantly higher instructional interactivity. These factors collectively demonstrate the great potential of VR as an educational technology, capable of significantly improving both learning efficiency and educational quality49.

Discussion

This study proposes and evaluates a VR-based immersive teaching model for traditional Chinese opera costume design, aiming to bridge the gap between cultural heritage preservation and educational innovation. The empirical results demonstrate that the model significantly enhances learning effectiveness, user experience, cultural understanding, technological adaptability, and instructional interaction. The following discussion elaborates on the broader implications of these findings.

Cultural preservation through technological and pedagogical integration

Traditional Chinese opera costumes encapsulate rich layers of historical symbolism, aesthetic expression, and cultural identity. However, conventional pedagogical approaches often fall short in conveying their multidimensional significance. This study demonstrates how immersive VR technology, when underpinned by intelligent performance optimization techniques such as LOD management and OC, can effectively revitalize and transmit traditional costume culture in contemporary educational settings.

By embedding AI-driven semantic annotation, interactive visualization, and real-time rendering into the VR platform, the proposed model goes beyond static reproduction. It creates a dynamic, multisensory environment where learners not only observe but also manipulate costume details, navigate symbolic meanings, and explore historical contexts in an embodied and participatory manner. This aligns with constructivist learning theory, which emphasizes active, contextually grounded knowledge construction.

From a technical perspective, integrating GPU-accelerated rendering strategies ensures that complex cultural content—characterized by intricate textures, layered structures, and symbolic ornamentation—can be rendered responsively without compromising visual fidelity. This technical innovation is not merely a back-end enhancement; it directly improves the educational experience by reducing system latency, minimizing distractions, and sustaining cognitive engagement. Therefore, this model represents a meaningful convergence of cultural preservation and digital innovation in arts education.

Learner-centered immersion and cultural engagement

One of the most significant outcomes of the study is the enhanced instructional interaction and learner engagement observed in the VR-based model. The immersive environment fosters a shift from teacher-centered delivery to learner-centered exploration. Learners gain autonomy in navigating cultural content, manipulating costume models, and engaging in exploratory tasks—all of which increase motivation, deepen focus, and enhance retention.

Notably, the VR model showed the most pronounced effect in improving instructional interaction (Cohen’s d = 1.87), suggesting that dynamic engagement with virtual environments supports more active learning than traditional passive modes. Students benefit from multisensory feedback—including gesture recognition, eye tracking, and auditory cues—that make the learning process more intuitive and emotionally resonant.

Moreover, the platform’s ability to situate costume elements within culturally authentic virtual scenarios enables a more nuanced understanding of their symbolic and performative roles. While the score gap in cultural understanding between the two models was smaller, it remains significant. This suggests that while VR enhances cultural perception through visualization and immersion, it should be complemented by interpretive guidance to achieve deep cultural literacy. Thus, the VR-based approach can be seen as a catalyst for cultural empathy and identity reinforcement—especially valuable in intangible cultural heritage education.

Limitations and future directions

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, the participant sample was limited to undergraduate students from a single academic institution, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Future research should include more diverse learner populations and explore cross-cultural adaptability of the model, especially when applied to other forms of traditional art education.

Second, while the system incorporates advanced rendering optimizations and semantic features, it remains a single-user experience. Future iterations could integrate multi-user collaborative features, AI-driven adaptive learning, and haptic feedback to further enrich the educational value and realism of the platform.

Additionally, long-term studies are needed to evaluate knowledge retention, transfer of design skills to real-world contexts, and the sustainability of cultural engagement over time. Expanding the system to encompass other elements of Chinese opera—such as music, choreography, and stage design—would contribute to building a holistic virtual archive and educational ecosystem for the preservation and revitalization of Chinese intangible cultural heritage.

Conclusion

This study developed and empirically validated an immersive teaching model for traditional Chinese opera costume design based on VR, integrating advanced 3D modeling, semantic annotation, and GPU-accelerated rendering optimization techniques. By combining pedagogical theory with cutting-edge visualization technologies—specifically LOD management and OC—the model successfully addresses the dual challenges of cultural preservation and educational innovation in the digital era.

Experimental results revealed that the VR-based model significantly outperformed traditional instructional approaches across five core dimensions: learning effectiveness, user experience, cultural understanding, technological adaptability, and instructional interaction. Particularly, the model’s immersive interactivity and real-time responsiveness not only enhanced students’ practical skills and cognitive engagement, but also deepened their appreciation of the symbolic and historical depth embedded in Chinese opera costumes. The empirical data provide robust evidence that immersive technologies can serve as effective vehicles for the transmission of intangible cultural heritage when coupled with optimized technical infrastructure and pedagogically sound design.

The study contributes to the growing body of research on digital cultural heritage by demonstrating that VR is not merely a visualization tool, but a transformative educational medium capable of enhancing learner autonomy, contextual understanding, and emotional resonance. It also sets a precedent for performance-oriented VR system design in cultural education, emphasizing that technological performance and instructional design must be co-optimized to achieve meaningful learning outcomes.

From a practical standpoint, the proposed model provides a scalable framework for educators, cultural institutions, and technology developers seeking to digitize and disseminate traditional knowledge in engaging, accessible, and pedagogically effective formats. The system’s modular architecture and optimization strategies make it adaptable to various cultural domains beyond opera costume design, including traditional crafts, performing arts, and ritual practices.

Looking ahead, future research should explore longitudinal impacts on cultural literacy, integrate collaborative multi-user environments, and incorporate intelligent learning analytics to support personalized education. Additionally, extending the platform to encompass the full ecosystem of Chinese opera—such as music, movement, makeup, and staging—will facilitate a comprehensive and immersive cultural learning experience. As immersive technologies continue to evolve, their role in shaping the future of cultural education and digital heritage preservation will become increasingly pivotal.

In conclusion, this study affirms that immersive VR—when thoughtfully integrated with cultural semantics and technical optimization—can serve as a powerful pedagogical tool for bridging the gap between heritage and innovation, between tradition and technology, and between past and future.

Data availability

Data is available in the manuscript.

References

Shang, Q. & Wang, H. Cultural continuity and change: Female characters in modern Chinese opera’s evolution. Cult. Int. J. Philos. Cult. Axiol. 21(2), 293 (2024).

Niemi, H. Active learning—a cultural change needed in teacher education and schools. Teach. Teach. Educ. 18(7), 763–780 (2002).

Thianthai, C. & Tamdee, P. How ‘digital natives’ learn: Qualitative insights into modern learning styles and recommendations for adaptation of curriculum/teaching development. J. Community Dev. Res. (Humanities and Social Sciences) 15(3), 85–93 (2022).

Wood, R. E., Beckmann, J. F. & Birney, D. P. Simulations, learning and real world capabilities. Educ. Train. 51(5/6), 491–510 (2009).

Zhang, J., Wan Yahaya, W. A. J. & Sanmugam, M. The impact of immersive technologies on cultural heritage: A bibliometric study of VR, AR, and MR applications. Sustainability 16(15), 6446 (2024).

Liu, Q. & Sutunyarak, C. The impact of immersive technology in museums on visitors’ behavioral intention. Sustainability 16(22), 9714 (2024).

Selmanović, E. et al. Improving accessibility to intangible cultural heritage preservation using virtual reality. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 13(2), 1–19 (2020).

Zhang, Q. Advanced techniques and high-performance computing optimization for real-time rendering. Appl. Comput. Eng. 90, 14–19 (2024).

Casado-Coscolla, A. et al. Rendering massive indoor point clouds in virtual reality. Virtual Real. 27(3), 1859–1874 (2023).

Li, R. View-dependent Adaptive HLOD: Real-time interactive rendering of multi-resolution models. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGGRAPH European Conference on Visual Media Production 1–10 (2023).

Dong, Y. & Peng, C. Multi-GPU multi-display rendering of extremely large 3D environments. Vis. Comput. 39(12), 6473–6489 (2023).

Schütz, M. et al. GPU-accelerated LOD generation for point clouds. Comput. Graph. Forum 42(8), e14877 (2023).

Ye, J. et al. Neural foveated super-resolution for real-time VR rendering. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 35(4), e2287 (2024).

Wu, P. et al. VR-empowered interior design: Enhancing efficiency and quality through immersive experiences. Displays 86, 102887 (2025).

Coorg, S. & Teller, S. Real-time occlusion culling for models with large occluders. In Proceedings of the 1997 Symposium on Interactive 3D graphics 83-ff (1997).

Wang, D,, Qiu, L,, Li, B. et al. FocalSelect: Improving occluded objects acquisition with heuristic selection and disambiguation in virtual reality. In IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics (2025).

Ge, Y., Xiao, X., Guo, B. et al. A novel LOD rendering method with multi-level structure keeping mesh simplification and fast texture alignment for realistic 3D models. In IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing (2024).

Zhang, S. et al. Data mining evoking scintillators auto-discovery for low-LoD high-resolution deep-penetrating X-ray imaging of portable digital radiography. Adv. Func. Mater. 35(7), 2415220 (2025).

Bezruchko, O., Gavran, I., Korablova, N. et al. Stage costume as an important element of the subject environment in cinema and theatre. In E-Revista de Estudos Interculturais 12 (2024).

Wang, L., Shi, X. & Liu, Y. Foveated rendering: A state-of-the-art survey. Comput. Visual Media 9(2), 195–228 (2023).

Liao, Y., Xie, J. & Geiger, A. Kitti-360: A novel dataset and benchmarks for urban scene understanding in 2D and 3D. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45(3), 3292–3310 (2022).

Wu, P. et al. 90The application of VR in interior design education to enhance design effectiveness and student experience. Displays 90, 103161 (2025).

Talaat, F. M. et al. Effective scheduling algorithm for load balancing in fog environment using CNN and MPSO. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 64(3), 773–797 (2022).

Chuprina, N. et al. Design of the contemporary garments on the basis of the transformation of stylistic and artistic-compositional characteristics of traditional decorative art. Art Des. 3(4), 30–44 (2021).

Ding, Q. K. & Liang, H. E. Digital restoration and reconstruction of heritage clothing: A review. Herit. Sci. 12(1), 225 (2024).

He, W. et al. Modeling and realization of image-based garment texture transfer. Vis. Comput. 40(9), 6063–6079 (2024).

Sani, M. N. A. & Sin, N. S. M. Development of character costume symbolism in animation folklore: A systematic review. Oppor. Risks AI Bus. Dev. 1, 485–495 (2024).

Smith-Glaviana, D. et al. Comparative study and expansion of metadata standards for historic fashion collections. Visual Resour. Assoc. Bull. 50(1), 6 (2023).

Radavičienė, S. & Jucienė, M. Influence of embroidery threads on the accuracy of embroidery pattern dimensions. Fibres Text. Eastern Europe 20(3), 92–97 (2012).

Kroes, T., Post, F. H. & Botha, C. P. Exposure render: An interactive photo-realistic volume rendering framework. PLoS ONE 7(7), e38586 (2012).

Spielmann, J. L. Planetary Rendering using Tessellation and Chunked LOD (University of Applied Sciences Technikum Wien, Wien, 2015).

Kirkland, A. Costume core: Metadata for historic clothing. Visual Resour. Assoc. Bull. 45(2), 6 (2018).

Mine, M., Yoganandan, A. & Coffey, D. Principles, interactions and devices for real-world immersive modeling. Comput. Graph. 48, 84–98 (2015).

Sutcliffe, A. G. et al. Reflecting on the design process for virtual reality applications. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 35(2), 168–179 (2019).

Pantouvaki, S. Embodied interactions: Towards an exploration of the expressive and narrative potential of performance costume through wearable technologies. Scene 2(1–2), 179–196 (2014).

Velloso, E. et al. The feet in human–computer interaction: A survey of foot-based interaction. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 48(2), 1–35 (2015).

Guay, M., Cani, M. P. & Ronfard, R. The line of action: An intuitive interface for expressive character posing. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 32(6), 1–8 (2013).

van der Vaart, J. et al. Enriching lower LoD 3D city models with semantic data computed by the voxelisation of BIM sources. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 10, 297–308 (2024).

Shi, S. & Hsu, C. H. A survey of interactive remote rendering systems. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 47(4), 1–29 (2015).

Marwah, K. et al. Compressive light field photography using overcomplete dictionaries and optimized projections. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 32(4), 1–12 (2013).

Hladky, J., Seidel, H. P. & Steinberger, M. The camera offset space: Real-time potentially visible set computations for streaming rendering. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 38(6), 1–14 (2019).

Vince, J. Essential Virtual Reality Fast: How to Understand the Techniques and Potential of Virtual Reality (Springer, Cham, 2012).

Dalle, J., Aydin, H. & Wang, C. X. Cultural dimensions of technology acceptance and adaptation in learning environments. J. Form. Des. Learn. 8, 1–14 (2024).

Piccoli, G., Ahmad, R. & Ives, B. Web-based virtual learning environments: A research framework and a preliminary assessment of effectiveness in basic IT skills training. MIS Q. 25, 401–426 (2001).

Alfieri, L., Nokes-Malach, T. J. & Schunn, C. D. Learning through case comparisons: A meta-analytic review. Educ. Psychol. 48(2), 87–113 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Application and renovation evaluation of Dalian’s industrial architectural heritage based on AHP and AIGC. PLoS ONE 19(10), e0312282 (2024).

Rovegno, I. Content-knowledge acquisition during undergraduate teacher education: Overcoming cultural templates and learning through practice. Am. Educ. Res. J. 30(3), 611–642 (1993).

Kyriakides, L., Christoforou, C. & Charalambous, C. Y. What matters for student learning outcomes: A meta-analysis of studies exploring factors of effective teaching. Teach. Teach. Educ. 36, 143–152 (2013).

Wang, T. J. Incorporating virtual reality into teaching–a case study of the Dan character’s body movement course in traditional Chinese opera. Int. J. Perform. Arts Digit. Media https://doi.org/10.1080/14794713.2025.2471610 (2025).

Funding

This research was supported by the following projects: the Quality Engineering Project of the Department of Education of Anhui Province—Anhui Creative Design Industry College (Grant No. 2024cyts007); the Quality Engineering Project of the Department of Education of Anhui Province—Upgrading and Transformation of the Fashion and Costume Design Program (Grant No. 2024zygzts060); and the Key Scientific Research Project of Universities in Anhui Province—Research on Stage Art Design of Huangmei Opera from a Cross-cultural Perspective (Grant No. 2024AH052760).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhiyan Su: Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Investigation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing; Project administration; Funding acquisition.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Anqing Normal University (Approval No. AQNU2025-Ethics-0032). All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Prior to participation, all undergraduate student participants were fully informed about the objectives, methods, and voluntary nature of the study. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Personal data were anonymized, and participants were assured of the confidentiality and secure handling of all collected information.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, Z. Immersive teaching model for traditional Chinese opera costume design based on virtual reality: digital cultural heritage, inheritance, and innovation. Sci Rep 15, 34830 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19350-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19350-7