Abstract

Undernutrition remains a major cause of child morbidity and mortality globally, with poor dietary diversity—particularly the limited intake of animal-source foods—being a key factor. In Ethiopia, egg consumption is low, with only 13 eggs per person annually. This study assessed the impact of the Market-based Innovation for Nutrition in Ethiopia (MINE) project, which implemented the Egg Hub model to enhance egg production and marketing, and introduced a social behavior change communication (SBCC) and egg subsidy scheme to increase the demand for eggs among children aged 6–23 months. A four-round repeated cross-sectional survey was conducted in Bishoftu and East Shoa Zone targeting children aged 6–23 months. Children’s dietary diversity was assessed using the minimum dietary diversity (MDD) indicator via 24-h recall, while maternal knowledge and attitudes toward child feeding were assessed using a seven-item questionnaire. The primary outcome—change in MDD—was analyzed using multiple logistic regression, with qualitative interviews conducted to supplement quantitative findings. Results showed that the proportion of children achieving MDD increased from 29.7% in the first survey to 76.2% in the fourth. Egg consumption rose from 23.6% to 74.5% across the same period. Maternal knowledge on child feeding improved from 52.7% to 78.2%, and positive attitudes toward recommended feeding practices rose from 76.3% to 87.2%. The Egg Hub model, combined with the comprehensive SBCC and egg subsidy scheme implemented in the MINE project, significantly improved MDD. Scaling up this intervention is recommended to enhance child nutrition at a broader level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malnutrition remains a critical public health concern in Ethiopia, particularly among young children1. Undernutrition, including stunting, wasting, and micronutrient deficiencies, affects millions of children and contributes to increased morbidity and mortality. In 2022, an estimated 148.1 million children under the age of five (22.3%) were stunted, while 45 million (6.8%) were affected by wasting, including 13.6 million (2.1%) suffering from severe wasting2. Poor dietary diversity is a major determinant of child undernutrition, as many lack access to adequate nutrients needed for optimal growth and development3. Research indicates that incorporating animal-source foods (ASFs) into children’s diets can effectively mitigate stunting in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including Ethiopia4. However, ASFs are often costly for low-income households. Among ASFs, eggs are one of the most affordable and accessible options. They are highly nutrient-dense, providing high-quality protein, essential fatty acids, vitamins, and minerals, such as choline, vitamin B12, and iron5. Moreover, regular egg consumption has been shown to significantly enhance child growth and cognitive development, by improving dietary diversity and ensuring they receive sufficient nutrients to meet their dietary needs4,6,7,8,9.

Yet, despite their nutritional value, egg consumption remains low among children in Sub-Saharan Africa due to cost, scarcity, and cultural beliefs10. In 2021, the Food and Agriculture Organization reported that egg availability in the region was only 40 eggs per capita per year, significantly lower than the 322 eggs per capita in North America11. Global data from UNICEF indicate that 22% of children aged 6 to 23 months consume eggs, with disparities based on economic status—only 17% in the poorest households compared to 30% in the wealthiest3. While poultry farming is common livelihoods of rural communities in developing countries12, the dominant backyard poultry systems in these regions are largely inefficient, inadequate to increase egg supply in rural economies, and pose potential health risks13,14,15,16.

Similarly, in Ethiopia, egg consumption remains low among children aged 6–23 months17. Cultural taboos, perceptions that eggs cause illness or delayed speech in children, and low purchasing power limit their intake17,18,19,20. Additionally, Ethiopian poultry sector faces several challenges that hinder productivity and further restrict access to eggs in rural communities21,22, 13 eggs a year are available per person in Ethiopia, among the lowest in Africa21. Most poultry is raised in backyard systems with poor genetics and inadequate feeding practices, leading to low egg production per bird21. Disease prevalence is another major concern, as the lack of vaccination and biosecurity measures increases the occurrence of outbreaks, further reducing production22. Additionally, feed scarcity, driven by high costs and limited availability, restricts farmers from providing adequate nutrition to their poultry22. Market instability also poses a significant challenge, with poor infrastructure and unreliable buyers causing price fluctuations and difficulties in selling poultry products22. Furthermore, limited extension services leave small-scale farmers without access to veterinary support and proper training in improved poultry management practices, further exacerbating the sector’s struggles21,22. Addressing these barriers requires integrated interventions that enhance both egg production and household consumption behaviors.

Traditional poultry-rearing practices alone are unlikely to significantly improve egg availability and consumption. More productive, sustainable, and scalable models are needed. The Egg Hub model, successfully implemented in Malawi, has demonstrated its potential to enhance egg production, increase farmer incomes, improve community egg access, and generate revenue for egg operators23. This model centralizes support for smallholder farmers by providing high-quality inputs, training, extension services, and market access, ultimately enhancing food security and making animal-source foods more affordable24.

However, increasing production alone is insufficient to drive changes in dietary behaviors. In many Ethiopian communities, animal-source foods are considered luxury items rather than essential dietary components17. Strengthening Social and Behavior Change Communication (SBCC) is crucial to shifting perceptions and increasing egg consumption. SBCC interventions that integrate community education, mass media, and interpersonal counseling have proven effective in improving child feeding practices and promoting animal-source food intake24,25.

Despite the potential of Egg Hub model combined with an egg subsidy scheme and SBCC, there is limited context-specific evidence on their effectiveness in Ethiopia. This pilot study aims to assess whether an integrated intervention that combines increased egg production and marketing (accessibility) through the Egg Hub model with a subsidy scheme to enhance affordability and SBCC strategies -– can enhance child dietary diversity and egg consumption. Specifically, we investigate whether greater household egg availability, paired with targeted behavior change strategies, leads to improved egg consumption and overall dietary diversity among young children in Ethiopia.

Methodology

Study design, participants and setting

A repeated cross-sectional study was conducted among children aged 6–23 months old in four districts within the Bishoftu City Administration and East Shoa Zone. The study was conducted over four survey periods: October 30 to November 3, 2023 (Survey 1); February 26 to March 1, 2024 (Survey 2); July 15 to 19, 2024 (Survey 3); and November 11 to 14, 2024 (Survey 4) monitoring changes in egg consumption and dietary diversity over time at population level. Bishoftu city and East Shoa zone are located in the Oromia regional, approximately 50 km from the capital, Addis Ababa. Ethiopia, Africa’s second-largest poultry population count, has substantial poultry resources and a growing commercial sector that supports local economic development, particularly in semi-urban and rural areas. The poultry industry has the potential to alleviate poverty and promote socio-economic inclusion by providing employment and stable livelihoods, especially for women, people with disabilities, and rural youth. However, Ethiopia struggles to meet the rising domestic demand for poultry products, as its poultry sector remains largely subsistence-based with low production and productivity26.

Intervention packages

Increase egg productivity and marketing (accessibility): The egg Hub model

The Market-based Innovation for Nutrition in Ethiopia (MINE) project, funded by the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF) and implemented by SNV with technical advisory from Sight & Life (SAL), aimed to achieve sustainable transformation of the egg value chain in targeted areas in Ethiopia. The egg supply component adopted an innovative Egg Hub model developed by SAL. The model comprises an egg hub operator and a network of farm groups having 5 members each. The egg hub operator served as a centralized unit providing high-quality affordable inputs, training, and extension services to independent poultry farmers. It is a sustainable, localized model of egg production that spurs the establishment of small-sized farms in the egg hub’s catchment area to achieve economies of scale. The egg hub achieves lower production costs and maximizes efficiency through aggregation, applying best practices for bird rearing and egg production, and supporting farmers through in-kind credit using a revolving fund. Additionally, the eggs produced were made accessible to the community through farm-gate sales (shops).

The project was designed using a phased approach, consisting of a pilot phase and a scale-up phase. The current is the pilot phase that was executed for the period of two and half years (May 2022 to December 2024). During this period, one Egg Hub was established, comprising one egg hub operator and a network of 16 farms in Bishoftu, Oromia region. The scale-up phase was planned to be implemented based on the result of the pilot phase. This paper presents the findings from the pilot phase of the project which was implemented in Bishoftu City Administration and East Shoa Zone.

Demand creation intervention: SBCC

While increasing egg production is essential for strengthening the egg value chain, evidence suggests that generating demand and implementing social marketing strategies are equally important for achieving nutrition outcomes. Ethiopian diets are largely cereal-based, with minimal consumption of animal-source foods, including eggs. Socio-cultural factors further contribute to low intake, including limited nutrition knowledge, perceptions that livestock products are primarily for income rather than household consumption, beliefs that animal-source foods are luxuries reserved for special occasions, and concerns about their digestibility for young children17. Many of these barriers are deeply ingrained and largely behavioral or influenced by social norms. Overcoming these challenges requires a targeted approach to behavior change and demand creation for animal-source foods to ensure the long-term impact of egg consumption on children’s nutritional outcomes.

To inform intervention design, a formative assessment was conducted to identify the most effective marketing channels from the available options. Several potential channels were considered, including orientation to frontline health professionals, community leader engagement, religious leaders, and discussion and capacity building to small retailers. This assessment shaped a comprehensive campaign strategy to increase egg consumption. Key marketing channels, such as health extension workers, priests, and local influencers, were prioritized due to their trusted presence within the community, more importantly the messenger effect of local influencers like religious leaders.

The SBCC team has been working on individual-level behavior change interventions, system-level capacity building, and strengthening the coordination with different actors. During this process, the role of community influencers, religious institutions, and health extension workers (HEWs) and other government structures including health center staff’s role was very important as they are trusted informants, convey a message, motivating and capacitating peoples for desired behavioral change.

The SBCC intervention focused on improving caregivers’ knowledge in several key areas: dietary diversification, hygiene, and breastfeeding. It also provided practical lessons to improve their skills in preparing nutritious food and maintaining a hygienic household, particularly emphasizing critical handwashing practices. The cooking demonstrations and mother conference sessions bring together mothers with different skills and knowledge of nutrition, and it served as a platform to share their personal experiences. These platforms facilitated the sharing of individual experiences and could motivate mothers to modify their behavior once after they learn possible options to improve diet diversity.

Egg subsidy scheme for children aged 6–23 months

To encourage egg consumption among children 6–23 months, the MINE project introduced a subsidized egg program providing one egg per day for a year at an affordable price (7 eggs for 20 birr—which was 70% discount compared to local market) over a one-year period in 16 pilot implementation kebeles (communities) each linked to one of the 16 farms. This initiative, informed by caregiver feedback from a formative assessment, aimed to address immediate nutritional needs while promoting long-term behavior change by enhancing perceptions of egg affordability. Only households with children aged 6–23 months were eligible to participate in the subsidy scheme. Through a voucher system, eligible caregivers purchased eggs from designated egg retailers sourcing directly from the 16 pilot farms. Eligible children and their households were identified and registered through a community-based targeting process conducted by local health extension workers (HEWs).

Sample size and sampling techniques

Sample size was calculated using a two-proportion comparison in STATA analysis software. The baseline prevalence of Minimum Dietary Diversity (MDD) among children aged 6–23 months was assumed to be 29.9%27, based on literature from area similar to the study setting, and a 50% increase after intervention was expected—resulting in an anticipated prevalence of 44.9%. This corresponds to an absolute effect size of about 15%. Using a 95% confidence level and a power of 80%, the initial sample size was estimated at 161 participants per each survey round. Adjusting for a design effect of 2 increased the sample size to 322 per round, and further adjustment for a 20% non-response rate resulted in a final sample size of 387 children aged 6–23 months per round.

The study employed a multi-stage sampling approach. The MINE project intervention included 16 kebeles. From these 16 kebeles, six kebeles were randomly selected using a lottery method. These same six kebeles were consistently used in all four survey rounds to assess changes over time in child dietary practices. Within each selected kebele, HEWs assisted the research team in preparing a list of all households with at least one child aged 6–23 months. This list served as the sampling frame for selecting study participants. A simple random sampling method was then used to select eligible households from each kebele. If a household had more than one child in the eligible age range 6–23months , one child was randomly selected to participate in the survey, following standard nutrition survey protocols.

It is important to note that each survey round employed a repeated cross-sectional design. That is, the same households or children were not followed over time, as children quickly age out of the 6–23 month eligibility window. Instead, a new sample of eligible children was drawn in each round based on updated household listings.

During data collection, two related studies were conducted in parallel. The first focused on households with children aged 6–23 months to assess the impact of the intervention on children dietary diversity. The second targeted households with Pregnant and Lactating Women (PLWs) to explore the program’s effect on maternal nutrition. In some cases, during the PLW-focused data collection, enumerators encountered sampled PLW households that also had programme participant child aged 6–23 months. In such instances, child-level dietary data were also collected. This overlap contributed to minor variations in sample sizes across rounds. However, the data collected for each target group were analyzed separately, and the sampling criteria remained distinct.

Data collection tools and procedures

Quantitative data

A standardized, semi-structured, and pre-tested questionnaire was used to collect data in all four rounds of the survey. Data collection was conducted using KOBO Toolbox, an open-source application that allowed for efficient and user-friendly data collection. The same data collectors and supervisors were employed throughout all survey rounds. The questionnaire was initially prepared in English and then translated into the local language. The tool was designed to capture information on socio-demographic characteristics, including land and livestock ownership, income, educational status, and WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene). Subsequently, maternal nutrition-related knowledge and attitudes were collected. Finally, data on dietary diversity for children aged 6–23 months were obtained.

UNICEF/WHO water and sanitation assessment tool was employed to assess access to safe drinking water and sanitation28. Maternal knowledge and attitude was evaluated using the Food and Agriculture Organization questionnaires for assessing knowledge, attitudes and practices concerning nutrition and feeding of infants and young children29. Child dietary diversity scores were assessed based on the mother/care givers recall of foods consumed by the child in the last 24 h. The MDD questionnaire was adopted from the WHO/UNICEF guidelines30 and aligned with versions used in national surveys such as the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). This ensured the food lists and classification were culturally relevant and comparable to national datasets. We used the open recall method, where trained enumerators guided respondents through a sequential 24-h recall of all foods and drinks consumed by the child. Standard probing questions helped identify individual food items and ingredients in mixed dishes. After the initial open recall, a “second pass” was conducted using a structured food group checklist to verify whether any major food groups had been missed, following WHO/UNICEF best practices. The food groups cover a wide range of essential nutrients and food categories, including grains, dairy, fruits and vegetables, protein sources like flesh foods, eggs, legumes, and breast milk.

Qualitative data

To complement the quantitative data, qualitative data were collected through in-depth interviews with a sub-sample of mothers/caregivers from the same study population, who were randomly selected from each kebele. In-depth interviews with caregivers were conducted during the survey period using a checklist to assess their KAP regarding child feeding, as well as the accessibility and affordability of eggs in the community. Each interview lasted between 45 to 60 min and was conducted by trained and experienced interviewers. All in-depth interviews were audio-recorded after obtaining consent from the participants. In addition to audio recording, the interviewers also took notes. The interviews were conducted in spaces that ensured the privacy, confidentiality, and safety of both participants and interviewers. All interviews were conducted in the local language and continued until information saturation was reached.

Study outcome

Our primary study outcome was change in the proportion of children meeting the MDD at population level, measured by comparing data from the first round survey with that of the fourth round. As secondary outcomes, we also assessed changes between the first and second rounds, as well as between the first and third rounds of the survey.

Quantitative data analysis

The study did primarily employ quantitative analysis. Qualitative findings were used to triangulate with the quantitative results and deepen interpretation of the findings.

All outcome variables (change in MDD from first (baseline) to fourth survey round and change from first to second and third survey rounds) were analyzed using STATA Software/MP, Version 18.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics, with continuous variables presented as means ± SDs and nominal variables as frequencies and percentages. WASH data were analyzed using the WHO & UNICEF (2018) method28, categorizing drinking water sources as either improved or unimproved. Similarly, sanitation facilities were classified as improved or unimproved.

The assessment of nutrition knowledge such as the recommended duration of continued breastfeeding, the appropriate age to introduce complementary feeding, reasons for providing complementary foods, and methods to enhance their nutritional value. The knowledge scale comprised seven items, including both open-ended and multiple-choice questions, with each correct response awarded one point. Individual scores were totaled and calculated as a percentage out of 100%. The assessment of attitudes toward infant and young child feeding practices focused on confidence in meal preparation, dietary diversity, feeding frequency, and potential barriers. The attitude scale also included seven items, measured using a 3-point Likert scale. Depending on the aspect being assessed, two versions of the scale were used: for perceived barriers, responses ranged from 1 (not difficult) to 3 (difficult), while for perceived benefits, responses ranged from 1 (not good) to 3 (good). To ensure that higher scores reflected a positive attitude, responses for perceived barriers were reverse-scored (i.e., 1 = 3, 2 = 2, and 3 = 1). Participants’ total attitude scores were then aggregated and expressed as a percentage out of 100%.

Child MDD scores were generated using WHO-UNICEF guidelines and dichotomized as achieved or not achieved. A score of fewer than 5 food groups out of 8 was considered not achieved and ≥ 5 as achieved30. Chi square test for the categorical MDD was used to measure changes due to the intervention effect. This test compares the outcome variables between groups (first round vs. fourth round, and first round vs. second and third rounds) without requiring paired observations. Furthermore, a multivariable binary logistic regression model was fitted to identify the independent effect of the project intervention (first-round vs. fourth round survey) on child dietary diversification after controlling potential confounders (maternal age, child age, sex of the child, maternal educational status, livestock ownership, maternal knowledge and attitude towards child feeding). The same confounder variables were adjusted for secondary outcome variables. The degrees of associations was assessed using adjusted odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval and a significance level of 0.05. Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to determine model fitness31. Multicollinearity between explanatory variables was checked by using the variance inflation factor (VIF).

Qualitative data analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and translated into English. Thematic analysis was used to categorize emerging themes, ensuring that broad conceptual descriptions reflected the overarching meanings of the data. Qualitative findings were triangulated with quantitative results to enhance analytical depth and reliability.

Data quality control

Enumerators were recruited based on their competence and commitment to staying with the project until its completion. They underwent intensive training at the study’s outset, covering research objectives, data collection tools, interview techniques, and ethical considerations. Before each survey round, refresher training sessions were conducted to address challenges encountered in previous rounds, reinforce adherence to study protocols, and emphasize ethical principles. Daily feedback sessions were held to promptly address any issues that arose during data collection.

Ethical clearance

Ethical approval was obtained from Oromia Regional Health bureau ethical review board, reference number BFO/HBTFH/116/772. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from the mothers of the study children or their legal guardians after a thorough explanation of the study’s purpose.

Result

Household and child characteristics

The study included four rounds of surveys, with the number of children surveyed ranging from 387 in round 1 to 425 in round 4, while the mean age of children between 12 and 14 months across all rounds (Table 1). The sample size varied between the four survey rounds due to the combined assessment of pregnant and lactating women and children in randomly selected households for surveillance monitoring purposes. This process resulted in the inclusion of more children than statistically required. Around one-third of the mothers had completed primary education. Livestock ownership decreased from 60% to 49.6%, and agricultural land ownership declined from 47.8% to 38.2%. Access to improved drinking water sources increased steadily from 80.5% in round 1 to over 91% in round 4, and improved toilet facilities remained consistently high, ranging from 83.8% to 88.4% (Table 1).

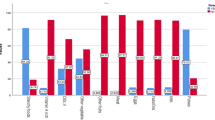

Association between SBCC intervention and maternal knowledge and attitudes

Table 2 shows a significant improvement in maternal knowledge and attitudes towards child feeding following the implementation of SBCC intervention. The proportion of mothers correctly answering key knowledge-related questions increased across all survey rounds, with notable gains in understanding the recommended duration of continued breastfeeding (55.4% in round 1 to 80.3% in round 4), the importance of meal consistency (27.2% to 78.9%), and the concept of responsive feeding (57.0% to 99.5%). Overall, the proportion of mothers classified as having high knowledge increased from 52.7% in round 1 to 78.2% in round 4. Similarly, maternal attitudes toward child feeding also showed positive trends. Confidence in food preparation rose from 86.7% to 97.4%, and the perception that dietary diversity benefits children remained high (98.7% to 99.1%). Additionally, the proportion of mothers reporting difficulties in feeding children a variety of foods and multiple times a day declined significantly, from 84.3% to 55.5% and 86.5% to 32.9%, respectively. The overall classification of positive attitudes improved from 76.3% in round 1 to 87.5% in round 4, highlighting the effectiveness of SBCC in fostering improved maternal feeding practices. The quantitative findings are supported by qualitative data. During in-depth interviews, mothers consistently reported that a key barrier to feeding eggs to their children had been common misconceptions about egg consumption. However, they noted that these misconceptions were corrected after receiving awareness-raising information from health professionals through the project.

"Previously, many mothers in our community, including myself, avoided giving eggs to our children due to the local belief that eggs are difficult for children to digest. However, after receiving education from health professionals about the benefits of eggs, we changed our mindset and started feeding them to our children. The availability of subsidized eggs at a lower price in our village also made it easier for me to include eggs in my child’s diet."

26 year old pregnant mother.

Egg accessibility and affordability

The intervention significantly improved household access to eggs. Caregivers reported increased availability of eggs near their households, attributed to higher local production at farm gates. Additionally, affordability improved as the intervention contributed to a more stable egg supply with subsidized prices, 7 eggs were sold for 20 birr at the retailer outlet—which was 70% discount compared to local market. The impact on accessibility and affordability is further evidenced by the rise in the proportion of children consuming eggs in the last 24 h. At baseline (Round 1), only 23.6% of children had consumed eggs in the previous 24 h. This figure increased to 35.4% in Round 2, 73.3% in Round 3, and 74.5% in Round 4, demonstrating the intervention’s positive effect on egg accessibility and affordability in the local market. These findings are reinforced by qualitative data, where caregivers consistently reported improved affordability and accessibility of eggs following the implementation of the MINE project.

"I am very happy that eggs are available for our children at a subsidized cost—I get seven eggs from the retailer outlet for 20 birr, which is much cheaper compared to the local market. At least my child’s breakfast is covered. I have noticed that my child’s appetite has improved since I started feeding him eggs. I can easily mix the egg with different ingredients like avocado, potato, or carrot, and he eats them comfortably."

27-year-old mother residing in Biyo Bisqe Kebel.

"I used to buy noodles or pastini for my child’s breakfast as they were cheaper, easy to prepare, and lasted longer—one packet could last up to two weeks. Eggs were too expensive, so I provided them only occasionally. However, since this project began, eggs have become more affordable and accessible. Now, I can buy them more often, significantly improving my child diet."

19 years young lady residing in Godino Kebele.

Trend of minimum dietary diversity

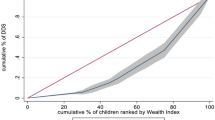

A significant improvement in egg consumption in the last 24 h was observed across the survey rounds. Similarly, a statistically significant improvement in achieving MDD among children aged 6–23 months was observed across the survey rounds. The proportion increased from 29.7% in the first round to 43.5% in the second round, 73.5% in the third round, and 76.2% in the fourth round (Fig. 1). A chi-square test comparing the proportion of children achieving MDD across the four round survey confirmed these differences, yielding a p-value of < 0.001. Similarly, the mean (± SD) number of food groups consumed increased across survey rounds: 3.7 (± 1.7), 4.5 (± 1.6), 5.5 (± 1.6), and 6.1 (± 1.7), respectively. Furthermore, to better understand the increased prevalence of meeting MDD across survey rounds, we conducted an additional analysis examining the proportion of children consuming each of the eight MDD food groups (Table 3). The results show that while egg consumption increased most significantly over time, there were also moderate improvements in the consumption of legumes and nuts, vitamin A rich fruits and vegetables, and other vegetables and fruits.

To control for potential confounding effects, logistic regression analysis was conducted, adjusting for maternal age, maternal educational status, livestock ownership, the age of the child, sex of the child, and maternal knowledge and attitude towards child feeding. The analysis confirmed a significant improvement (Table 4). Compared to the first survey round, the odds of achieving MDD among children aged 6–23 months were 1.8 times higher in the second round and 6.8 times higher in the third survey round, while keeping other variables constant. Similarly, compared to the first survey round, the odds of achieving MDD among children aged 6–23 months were 7.8 times higher in the fourth survey round. In addition, higher maternal knowledge and a more positive attitude toward good child feeding practices were both significantly associated with increased odds of meeting MDD.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that the Egg Hub model, combined with SBCC interventions and an egg subsidy scheme was significantly associated with improvements in egg consumption and dietary diversity among children aged 6–23 months in the study areas. These results highlight the effectiveness of integrated interventions in addressing both supply- and demand-side barriers to child nutrition. Our findings align with similar interventions conducted in low-resource settings that have successfully combined agricultural production with nutrition-focused behavior change strategies23,24.

The Egg Hub model played a critical role in enhancing egg availability and affordability is consistent with findings from a similar intervention in Malawi, which showed that centralized poultry farming systems improved smallholder farmer productivity, increased household egg consumption, and contributed to higher farmer incomes23. By providing smallholder farmers with access to affordable inputs, training, and structured market linkages, the intervention addressed several production-related barriers, including feed scarcity, poor poultry management, and market instability. This is particularly important in Ethiopia, where previous studies have noted that backyard poultry systems are highly inefficient, leading to low egg production and limited accessibility21,22.

Beyond supply-side improvements, our study highlights the crucial role of demand-side interventions in improving child feeding behaviors. The SBCC strategies, including roadshows, community sensitization, and household nutrition counseling —were significantly associated with increased caregiver knowledge and more favorable attitudes toward good complementary feeding practices over the course of the intervention. The qualitative data supports these findings, as mothers reported that the SBCC intervention enhanced their awareness of the nutritional benefits of egg consumption. It also played a crucial role in dispelling long-standing community taboos that previously discouraged egg consumption among children. These results aligns with research from Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Vietnam, where behavior change interventions improved maternal dietary practices32. Furthermore, systematic review by Bhutta et al33 found that SBCC programs positively influenced caregiver practices and child nutrition outcomes. Similar improvement in egg consumption have been reported in cluster-randomized trial in Malawi, which demonstrated improved intake of animal-source foods34 and a study in Rwanda, which reported a 73% increase in egg intake compared to the control group, driven by significant improvements in knowledge and attitudes35.

Our study suggests that targeted subsidy programs may play an important role in supporting increased egg intake among young children. The subsidized egg scheme appeared to provide a crucial short-term mechanism for improving affordability and accessibility. Evidence from China supports this approach, showing that food subsidy programs significantly improved child nutrition and dietary diversity36. However, sustainability remains a concern, as subsidy reliance may reduce egg consumption once external support is withdrawn. Future interventions should explore ways to integrate such programs into national social protection systems or link them with local government initiatives to ensure long-term impact. Additionally, a follow-up study is required to assess the sustainability of increased egg consumption after the subsidy scheme ends.

Beyond egg consumption, our findings showed a notable improvement in the proportion of children meeting the MDD, as supported by the increase in the mean (± SD) number of food groups consumed across survey rounds. While the most substantial increase was observed in egg consumption—providing the plausibility that the observed improvements in MDD were largely attributable to the intervention—our expanded analysis also revealed moderate increases in the consumption of other nutrient-dense foods such as legumes and nuts, vitamin A rich fruits and vegetables, and other vegetables and fruits. These broader dietary improvements are consistent with the focus of the SBCC messaging, which emphasized both egg consumption and overall dietary diversity. This is consistent with a study conducted in another part of the country, where a chicken production intervention combined with nutrition education led to increased dietary diversity scores among children37. Additionally, a multi-country analysis by Headey et al38 emphasized the strong association between dietary diversity and child growth outcomes, reinforcing the importance of diversified diets in early childhood. Our qualitative data also suggested that the MINE project intervention was associated with improved access to eggs in local markets at affordable prices, enabling mothers to provide eggs more regularly than before. Additionally, cooking demonstrations appeared to help caregivers learn how to mix eggs with different ingredients, which some reported lead to improved child appetite and greater acceptance of a variety of foods.

To better contextualize these findings, we compared dietary outcomes in our study population with national and regional benchmarks. The 2023 national food and nutrition baseline survey reported MDD prevalence of 8% nationally and 7% in the Oromia region among children aged 6–23 months (1). In contrast, our pilot data show that MDD reached 74.5% at endline, suggesting a notable improvement that may be attributable to the integrated intervention approach. Furthermore, our baseline data also indicate that a higher proportion of children met MDD (29.7%) compared to national and regional figures. A possible explanation for this difference is that our study was conducted in an area located very close to the capital city, which is relatively food-secure, unlike the national and regional figures that include very rural areas with higher levels of food insecurity.

However, despite these promising results, the pilot also faced important operational challenges. For example, some affiliated shop owners showed limited commitment to distributing eggs, largely due to price fluctuations and the declining purchasing power of the Ethiopian Birr, which reduced profit margins. Egg productivity at the affiliated farms also fluctuated between profit and loss, leading to interruptions in egg supply. Distribution challenges in remote kebeles, where access to shops and distributors was limited. Additionally, it was difficult to identify and retain committed egg distributors who could follow the program procedures reliably. These challenges offer important lessons for future program design and highlight the need for practical, flexible, and innovative solutions in implementation planning.

Overall, this study contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the role of integrated food production, behavior change interventions, and an egg subsidy scheme in improving child nutrition outcomes. By addressing both supply-side constraints and demand-side behavioral factors—along with subsidies to enhance affordability—the Egg Hub model, combined with SBCC and a subsidy scheme, has proven to be a viable approach for improving child dietary diversity. Future research should explore the long-term sustainability of increased egg consumption after the subsidy is withdrawn and assess the potential scalability of the project in different contexts.

Strength and limitation of the study

A major strength of this study was the implementation of the Egg-Hub poultry farm model. This model has been proven to outperform previous poultry farm models, offering a more sustainable and efficient approach to boosting local egg production23. The project also incorporated practical sessions that enabled mothers to share their experiences and acquire hands-on skills related to dietary diversification, complementing the theoretical awareness-creation interventions. These sessions provided valuable opportunities for learning and peer support. Additionally, each survey period involved a substantial sample of children, ensuring that the findings were representative and robust across different time points. Finally, the use of consistent data collectors and supervisors enhances data quality. However, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, in the present study we don’t have a control group allows for a direct comparison between those who receive the intervention and those who do not, which could have help to establish causality relationships between the intervention and the outcomes. Second, we were unable to control for all potential confounding factors—such as seasonality, climate variability, and broader economic conditions—which may have influenced child feeding practices independently of the intervention. Although data collection was conducted quarterly over one year, with survey rounds capture both lean and post-harvest periods, these contextual factors may still have affected the results. We recommend future similar studies to consider a comparator (control) group and longitudinally following the same children would add valuable insights into individual-level change and improve causal inference. Additionally, efforts should be made to account for contextual variables such as seasonal food availability, environmental conditions, and macroeconomic factors to strengthen attribution and improve the validity of the findings.

Conclusion

The combined implementation of the Egg Hub model, SBCC strategies, and a targeted subsidy scheme was associated with improvements in egg production and availability, maternal nutrition knowledge and attitude, and dietary diversity among children aged 6–23 months. These findings suggest that an integrated, market-based approach has potential to address both supply- and demand-side barriers to child nutrition. Given these promising results, scaling up this integrated model to other regions may contribute to broader improvements in egg availability, affordability and children dietary diversity.

Data availability

The dataset used and/or analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- APR:

-

Annual progress review

- CIFF:

-

Children’s investment fund foundation

- DOC:

-

Day-old chicks

- FAO:

-

Food and agricultural organization

- HEW:

-

Health extension workers

- IYCF:

-

Infant and young child feeding

- LMICs:

-

Low- and middle-income countries

- MINE:

-

Market-based innovation for nutrition in Ethiopia

- SBCC:

-

Social and behavioral change communication

- SAL:

-

Sight and life

- WASH:

-

Water, sanitation, and hygiene

References

EPHI. National Food and Nutrition Strategy Baseline Survey: Key findings preliminary report [Internet]. Available from: https://ephi.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/FNS_baseline_survey_preliminary_findings.pdf (2023).

UNICEF / WHO / World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates. Level and trend in child malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/ World Bank Group Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates Key findings of the 2023 edition. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240073791 (2023).

UNICEF. Fed to Fail: The crisis of children’s diets in early life. 2021 Child Nutrition Report. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/media/11016/file/FedtoFail-FullReport.pdf (2021).

Iannotti, L. L. et al. Eggs in early complementary feeding and child growth: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics 140(1) (2017).

Réhault-Godbert, S., Guyot, N. & Nys, Y. The golden egg: Nutritional value, bioactivities, and emerging benefits for human health. Nutrient 11(3), 1–26 (2019).

Caswell, B. L. et al. Impacts of an egg intervention on nutrient adequacy among young Malawian children. Matern. Child. Nutr. 17(3), 1–16 (2021).

Iannotti, L. L., Lutter, C. K., Bunn, D. A. & Stewart, C. P. Eggs: The uncracked potential for improving maternal and young child nutrition among the world’s poor. Nutr. Rev. 72(6), 355–368 (2014).

Stewart, C. P. et al. The effect of eggs on early child growth in rural Malawi: The Mazira Project randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 110(4), 1026–1033 (2019).

Ara, G. et al. A comprehensive intervention package improves the linear growth of children under 2-years-old in rural Bangladesh: A community-based cluster randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. [Internet]. 12(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26269-w (2022).

Morris, S. S., Beesabathuni, K. & Headey, D. An egg for everyone: Pathways to universal access to one of nature’s most nutritious foods. Matern.Child.Nutr. 14, 1–9 (2018).

FAO. World food and agriculture- statistical yearbook [Internet]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#compare (2023).

Akinola, L. A. F. & Essien, A. Relevance of rural poultry production in developing countries with special reference to Africa. World. Poult. Sci. J. 67(4), 697–705 (2011).

Beesabathuni, K., Lingala, S. & Kraemer, K. Increasing egg availability through smallholder business models in East Africa and India. Matern. Child. Nutr. 14(July), 1–10 (2018).

Bardosh, K. L. et al. Chicken eggs, childhood stunting and environmental hygiene: An ethnographic study from the Campylobacter genomics and environmental enteric dysfunction (CAGED) project in Ethiopia. One Heal Outlook. 2(1) (2020).

Alders, R. G. et al. Family poultry: Multiple roles, systems, challenges, and options for sustainable contributions to household nutrition security through a planetary health lens. Matern. Child. Nutr. 14, 1–14 (2018).

Wong, J. T. et al. Small-scale poultry and food security in resource-poor settings: A review. Glob. Food. Sec. 15(March), 43–52 (2017).

Haileselassie, M. et al. Why are animal source foods rarely consumed by 6–23 months old children in rural communities of Northern Ethiopia ? A qualitative study. PLoS One 1–21 (2020).

Zerfu, T., Duncan, A., Baltenweck, I. & Mcneill, G. Low awareness and affordability are major drivers of low consumption of animal - source foods among children in Northern Ethiopia : A mixed - methods study. Matern Child Nutr. 2024 (2024).

Kase, B. E. et al. Determinants of egg consumption by infants and young children in Ethiopia. Public.Health.Nutr. 25(11), 3121–3130 (2022).

Alemneh Kabeta, D., Mary Murimi, K. A. & DH. Determinants and constraints to household-level animal source food consumption in rural communities of Ethiopia. J. Nutr. Sci.1–10 (2021).

Barry, I,S., Getachew, G., Solomon, D., Asfaw, N. & Kidus Nigussie Gezahegn Mechale, H. M. Ethiopia livestock sector analysis: A 15 year livestock sector strategy. ILRI Project Report. Nairobi, Kenya: ILRI. (2017).

Ebsa, Y. A., Harpal, S. & Negia, G. G. Challenges and chicken production status of poultry producers in Bishoftu, Ethiopia. Poult. Sci. [Internet]. 98(11), 5452–5455 (2019).

Lingala, S. et al. The egg hub model: A sustainable and replicable approach to address food security and improve livelihoods. Curr. Dev. Nutr. [Internet]. 8(8), 103795 (2024).

Birhanu, MY., Osei-amponsah, R. & Obese, F. Y. Smallholder poultry production in the context of increasing global food prices : Roles in poverty reduction and food security. Anim.Front. 13(1) (2023).

Kennedy, E., Stickland, J., Kershaw, M. & Biadgilign, S. Impact of social and behavior change communication in nutrition sensitive interventions on selected indicators of nutritional status. J. Hum. Nutr. 2(1), 24–33 (2018).

Tsigereda Fekadu, W. E. et al. Ethiopia national poultry development strategy 2022–2031. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Government of Ethiopia, Ministry of Agriculture. (2022).

Molla, W. et al. Dietary diversity and associated factors among children ( 6 – 23 months ) in Gedeo zone , Ethiopia : cross - sectional study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 1–10 (2021).

WHO and UNICEF. Core questions on water, sanitation and hygiene for household surveys. [Internet]. Available from: https://washdata.org/report/jmp-2018-core-questions-household-surveys (2018).

Yvette Fautsch Macías, PG. Guidelines for assessing nutrition-related K nowledge, A ttitudes and P ractices manual Guidelines for assessing nutrition-related K nowledge, A ttitudes and P ractices manual. (2014).

WHO/UNICEF. Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices. (2021).

Hosmer, D. W. Jr., Lemeshow, S. & Sturdivant, R. Applied Logistic Regression 3rs edn. (JohnWiley & Sons, 2013).

Kim, S. S. et al. Different combinations of behavior change interventions and frequencies of interpersonal contacts are associated with infant and young child feeding practices in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Vietnam. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 8, 1–10 (2019).

Bhutta, Z. A. et al. Maternal and Child Nutrition 2 Evidence-based interventions for improvement of maternal and child nutrition : What can be done and at what cost? Lancet 382 (2013).

Lora, L. et al. Eggs in early complementary feeding and child growth : A randomized controlled trial. Pediatric. (2017).

Siegal, K., Wekesa, B., Uweh, J. & Niyonshuti, M. A good egg : An evaluation of a social and behavior change communication campaign to increase egg consumption among children in Rwanda. Matern.Child.Nutr. (2023).

Chen, Q., Pei, C., Bai, Y. & Zhao, Q. Impacts of nutrition subsidies on diet diversity and nutritional outcomes of primary school students in rural northwestern china — do policy targets and incentives matter? Int. J. Environ. Res. Pub. Health. (2019).

Passarelli, S. et al. A chicken production intervention and additional nutrition behavior change component increased child growth in ethiopia: A cluster-Randomized trial. J. Nutr. Communit. Int. Nutr. 150(10), 2806–2817 (2020).

Headey, D., Hirvonen, K. & Hoddinott, J. Animal sourced foods and child stunting. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 100(5), 1302–1319 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the participating families for their involvement in this study. Our gratitude also extends to the research staff for their dedication to data collection and supervision. We appreciate CIFF for their financial support, SNV for their role in implementation, and SAL for their technical advisory assistance.

Funding

This paper is an output from a MINE project which is funded by CIFF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GG: Conceptualization and design, acquisition, formal analysis and interpretation, drafted the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, gave final approval, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring integrity and accuracy. NM, AM, AF, SN, MG, WM, SG, SM, AM, KN, and MHB: Conceptualization and design, critically revised the manuscript, gave final approval, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gizaw, G., Mekonnen, N., Mamo, A. et al. Effects of an egg production intervention with social behavioral change communication and subsidy on child dietary diversity in Ethiopia. Sci Rep 15, 35501 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19603-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-19603-5