Abstract

Syria is recognized as one of the earliest cradles of olive cultivation. Olive oil is not only an agricultural product in Syria, but it is a symbol of national culture and identity that dates back over 6000 years. Olive oil composition and quality are influenced strongly with fruit maturity and variety. Understanding these effects is essential for optimizing harvest time and ensuring oil originality. This study focused on two Syrian olive varieties, Zaity and Kaissy, to assess how different maturity stages affect on triglyceride and fatty acids profiles in their oils. Fruits from Zaity and Kaissy trees in Aleppo were taken at three maturity stages (green, colored (turning) and black) every 15 days. Oils were extracted using the ABENCOR method. Physical parameters and maturity are assessed by tensile strength, coloration index, and tissue resistance. Oil content, free acidity, peroxide value, fatty acid, and triglyceride composition were measured using standard analytical techniques, including GC and HPLC. Zaity olives had a higher oil contents than Kaissy 30.8% and 21.2% respectively, with both increasing as fruit matured. Free acidity and peroxide values remained low across all stages, indicating that good oil quality. Oleic acid content decreased while linoleic and linolenic acids increased with maturity, especially in Kaissy. Triglyceride analysis revealed that LLL content rose with maturity, particularly in Kaissy, while OOO and POO peaked at intermediate stages and then declined. Significant correlations were found between fatty acid and triglyceride profiles, varying by variety and maturity. Both olive variety and fruit maturity stage significantly affect on the triglyceride and fatty acid composition of olive oil. Zaity is best harvested in November to maximize oil yield and quality, while Kaissy allows for later harvesting without compromising oil properties. These findings provide valuable guidance for harvest timing and authenticity assessment of Syrian olive oils.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Virgin olive oil is defined, according to Syrian Standard Specifications No. 182 of 2016 and the International Specifications issued by the International Olive Council (IOC)1, as “the fatty portion of the juice of fresh olives (Olea europaea L.), with a distinctive aroma and taste, free from defects, and extracted exclusively by mechanical extraction methods or any other physical method under strict conditions, particularly temperature, that do not result in any change in the nature of the oil and without undergoing any processing other than washing, centrifugation, and filtration1. Triglycerides constitute approximately 98-99.5% of the composition of olive oil. Triglycerides are produced by the esterification of the carboxylic groups of fatty acids with the alcohol groups of glycerol through a ester bond, according to the following equation. Figure 12.

Triglycerides vary according to: The type of fatty acids that make up the glycerides and the order these acids take within the glycerides at the α, β, and γ positions. This variation reflects a variation in the physical and chemical properties of the oil, and thus a difference between different types of oils and also between varieties of the same type3. Studies have shown a high percentage of triolein OOO, which is considered one of the most important features that distinguish olive oil from other vegetable oils, which are characterized by a significant increase in the percentage of trilinolenic acid LLL4,5. Table 13,4,5 shows the composition of the triglycerides of the most important vegetable oils, which demonstrates the high content of triolein OOO in olive oil of Spanish origin compared to other vegetable oils.

Several studies have also shown variations in the triglyceride content of olive oil depending on olive varieties and their growing regions. Italian and Spanish olive oils are characterized by their higher triglyceride content OOO compared to Tunisian olive oil. Table 2 shows the triglyceride composition of these oils, divided according to the number of equivalent carbon atoms (ECN: 42-44-46-48-50)6,7,8,9. It should be noted that there is currently no documented reference study from the International Olive Council that identifies the content of these compounds in Syrian varieties, comparable to global olive varieties.

The variation in the triglyceride composition of olive oils across varieties is linked to variations in the fatty acid content of these oils. This may be due to differences in the degree of fruit ripeness, in addition to the influence of climatic conditions and irrigation10. Changes in the fatty acid composition of Picholine marocaine olive oil at various stages of ripeness were studied. It was observed that the degree of ripeness is one of the most important factors influencing changes in fatty acid ratios. The early ripening stage is characterized by a decrease in oleic, stearic, and linoleic acids. As the fruit ripens, the proportions of palmitic, palmitoleic, and linolenic acids decrease, while the proportion of arachidic acid remains relatively constant11. Amelio M. concluded that to obtain an oil rich in monounsaturated fatty acids, it is preferable to harvest the fruit late (November and December). It was also mentioned that the variety affects the change in fatty acid ratios by 15%, the degree of fruit ripeness by 30%, while the period between harvest and pressing affects it by 20%, the pressing method by 20%, and the harvesting method by 10%12 It should be noted that olive oil contains low concentrations of diglycerides, ranging from 1 to 2.8%, while monoglycerides are present at a rate determination of at 0.25%10. It has been shown that the proportion of diglycerides linked to fatty acids at positions 1 and 2 of the glyceride is very low in high-quality, newly produced oils, resulting from the intermediate stages of the biosynthesis of triglycerides. While diglycerides, in which fatty acids are linked at positions 1 and 3, are formed as a result of the hydrolysis of triglycerides by lipase, as the oil ages, diglycerides 1 and 2 can convert to forms 1 and 3, as in old or poorly preserved oil, especially when exposed to light and heat, or when stored in unsuitable containers. Therefore, it can be concluded that the quality of the oil can be judged by the type of diglycerides present in its composition13.

Triglycerides play a fundamental role in determining the chemical fingerprint of the oil, determining its authenticity and purity. They also play a key role in highlighting the characteristics of each olive oil variety. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the characteristics of Syrian olive oil varieties. Furthermore, determining the composition of the glycerides is very important for detecting fraud in other vegetable oils14,15,16,17. The Zaity and Kaissy olive varieties are considered among the most important Syrian olive varieties, due to their widespread distribution in Aleppo Governorate, specifically in the Afrin, Jandairis, and Sheikh Hadid regions. In general, the Zaity and Kaissy varieties occupy 5–33% of the total olive cultivated area in the country, respectively. The importance of these varieties stems from their inherent characteristics and their distinctive chemical and sensory properties. Many of their chemical compounds have been studied, with the exception of their triglyceride composition. Therefore, this research aims to study the triglyceride composition of the oil of the Zaity and Kaissy varieties and the fatty acid content of these varieties and their relationship to the triglyceride composition.

Materials and methods

Source of studied varieties

The Zaity olive variety (Aleppo): It is primarily used for oil extraction, with an oil content of 32%18.

The Kaissy olive variety (Aleppo): A dual-purpose (pickling and oil extraction), with an oil content of 18%18.

Three trees of each variety were identified in the Maarset al-Khatib region of Aleppo Governorate. The farm is affiliated with the Department of Olive Research, General Commission for Scientific Agricultural Research (GCSAR), Syria. And the permission to collect plant material was obtained from the [General Commission for Scientific Agricultural Research (GCSAR), Syria]. The selected trees were homogeneous in terms of age and production. Olive fruit samples weighing (5) kg were collected from each labeled tree (duplicate). The harvest is carried out during three periods with sampling of three stages of maturity: green, turning and black.

Oil extraction

The oil was extracted using a laboratory press according to the ABENCOR method19. The sample was ground, then kneaded for (30) minutes, and the liquid phase was separated from the solid phase by centrifugation. The oil was separated by sedimentation and then filtered using filter paper. The samples were stored in suitable glass containers in the freezer until the required analyses were conducted in the study to minimize any changes in the oil composition.

Criteria studied

Determining the degree of fruit ripeness

The degree of fruit ripeness was determined based on three indicators:

Fruit tensile strength

Determined using a dynamometer on 50 fruits per tree and expressed in Newtons20.

Fruit tissue resistance to penetration

Determined using the same previous meter after it was equipped with a probe with a diameter of (1.5) mm, on 50 fruits per tree20.

Maturity index

Determined using a fruit sample of 100 fruits per tree using the Chyne color index21.

Degree of ripeness was calculated according to the following equation:

n0 Number of green fruits.

n1 Number of yellow fruits.

n2 Number of fruits with less than 50% of their outer surface purple.

n3 Number of fruits with more than 50% of their outer surface colored purple.

n4 Number of fruits with their entire surface colored black and their flesh colored white.

n5 Number of fruits with their entire surface colored black and less than 50% of their flesh colored purple.

n6 Number of fruits with their entire surface colored black and more than 50% of their flesh colored purple.

n7 Number of fruits with their entire surface colored black and the purple color reaching the seed.

N Total number of olives in the sample.

Determination of oil content

This was determined using a Soxhlet extractor by weighing (20) grams of olives, grinding them in a mortar, then transferring them to a porcelain bowl and placing them in a dryer at a temperature of (103 °C ± 2) for (24) hours until the weight stabilized. The dried fruit powder is then transferred to a Soxhlet extractor to extract the oil using the organic solvent “hexane” for (12) hours until complete extraction. The extracted oil is then weighed and the oil percentage is calculated according to the following formula:21.

Estimate the free acidity of the oil (based on oleic acid)22.

Estimate the peroxide value (mEq/kg oil)23.

Fatty acid contentexpressed as a percentage according to the method (COI-T.20-Doc. no. 24) using a gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with a SUPLCO – SP 2340 column24.

Triglyceride content was determined according to the method that using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) equipped with an RP18 column, using the carrier phase (acetone + acetonitrile) at a mixing ratio of (45:55), a flow rate of (0.8) ml/min, and using a refractive index detector (RI)24.

Statistical analysis

SPSS (Anova) was used to analysis the results.

Results and discussion

Fruit maturity

This was determined for the two studied varieties, “Zaity” and “Kaissy”, according to three indicators:

Fruit tensile strength

The results showed significant differences in the value of fruit tensile strength during the various stages of ripening in both studied varieties. At the beginning of ripening, the value was (5.3–5.9 N) for both Zaity and Kaissy, respectively, and reached (3.3–4.6 N) at the end of the ripening stage, respectively. Since the tensile strength decreased significantly in the Zaity variety, this indicates that delaying the harvest of this variety could expose it to fruit drop, thus deteriorating the quality of the resulting oil. This is consistent with the findings of Famiani20, which emphasized the need to avoid delaying the harvest of the Zaity variety. Note that the low tensile strength of the fruit allows for the use of mechanical harvesting or the use of small, portable hand-held harvesters, especially since this variety is characterized by the phenomenon of early fruit set. While these fruits are difficult to harvest manually, the Kaissy variety maintained a value higher than 4 N, preventing them from falling to the ground for a relatively longer period.

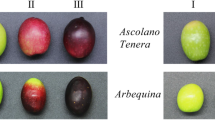

Coloration index

The coloration index of the fruit increased significantly across the various ripening stages in both studied varieties. It increased, reaching 0.3–0.7 in the early ripening stages of Zaity and Kaissy, respectively, and reached 2.4–3.5 in the late ripening stages of Zaity and Kaissy. Comparing the two varieties, we note that Zaity is more susceptible to coloration compared to Kaissy, a late-ripening Syrian variety. This explains the use of this variety, especially when its fruits are large, for green pickling. This is consistent with the findings of Abdine and his colleagues18.

Resistance of fruit tissue to penetration

Tshe reistance of fruit tissue to penetration decreased significantly in Zaity and Kaissy between the first and second ripening stages, while this decrease was not significant in the third ripening stage. However, in the Kaissy variety, this decrease was significant at different stages of maturity. In general, the average resistance of the fruit tissue to penetration was higher in the Kaissy variety, which explains the increased sensitivity to mechanical damage during harvesting and transportation in the fruits of the Zaity variety, which is negatively reflected in the properties of the resulting oil compared to the fruits of the Kaissy variety. This is consistent with Abdine and his colleagues18. Table 3 shows the results of the maturity indicators for the Zaity and Kaissy varieties.

Oil content

The average oil content on a fresh weight basis for the two studied varieties, Zaity and Kaissy, was 16.4–28.5%, respectively. The highest was in Zaity, which explains the use of Zaity in oil extraction. Significant differences were observed with increasing maturity for both varieties. The highest oil content of the Zaity variety, 30.8%, was achieved in December, with significant differences compared to the first harvest date and insignificant differences compared to the second harvest date. Therefore, it is recommended to harvest Zaity fruit during November to ensure that the fruit does not over-ripen, which exposes it to falling and thus impairs the quality of the oil. However, there were significant differences in the oil content during the various stages of ripening for the Kaissy caltivar, with the oil content reaching 21.2% in December. This delay in harvesting is possible, as the Kaissy caltivar maintains its firmness until a later date of ripening. Furthermore, the drop rate is lower due to the increased tensile strength (the fruit’s attachment to the tree). Therefore, there will be no negative impact on the sensory properties of the oil.

Free acidity

A non-significant increase in the free acidity content was observed with the progression of the ripening stages, with the average for the Zaity and Kaissy varieties being 0.26–0.34%, respectively. The higher free acidity in Kaissy olive oil compared to Zaity olive oil can be attributed to the higher water content of Kaissy olive fruits compared to Zaity olive fruits, which increases the hydrolysis of glycerides20.

Peroxide value

The average peroxide value during the three ripening stages of Zaity and Kaissy olive varieties was (4.8–4.9) milliequivalents O2/kg, a number so low that the oil produced is classified as virgin olive oil.

Table 4 shows the oil percentage based on fresh weight, the free acidity percentage, and the peroxide value (mEq. O2/kg) in Zaity and Kaissy olive varieties during the different ripening stages.

Fatty acids

The proportions of fatty acids within each variety varied according to the maturity stages. While the proportions of palmitic, palmitoleic, stearic, and arachidic were close to constant across the various maturity stages for both varieties (the average palmitic percentage in the olive and Kaissyvarieties was 13.2–13.9%, respectively, the average palmitoleic percentage was 0.6–0.7%, the average stearic percentage was 3.8–3.7%, and the average arachidic percentage was 0.36–0.50%, the oleic percentage decreased significantly in both varieties. At the beginning of maturity, the olive and Kaissy varieties were 72.4–68.5%, respectively, and then decreased to 66.6–71.1%, respectively. This was accompanied by significant increases in both linoleic and linolenic acids. Linoleic acid levels were 8.3–12.5% at the beginning of ripening, reaching 9.5–14.0% at the end of the ripening stage. Linolenic acid levels were 0.6–0.7% at the beginning of ripening, reaching 0.8–0.9% at the end of the ripening stage. A study of the correlation between oleic and linoleic acids revealed a significant negative correlation in the Kaissy variety, with an r2 value of 0.998. However, there was a non-significant negative correlation in the Zaity variety, with an r2 value of 0.965. Figure 2 shows the correlation between the two oleic and linoleic fatty acids. This is consistent with numerous studies25,26,27 that explained these differences as a result of changes in the activity of enzymes responsible for fatty acid synthesis during the ripening stages of olive fruit, particularly the activity of the enzyme Δ12-Desaturase, responsible for converting oleic acid to linoleic and linolenic acids. However, the behavior of arachidic acid differs from the same studies, which reported a decrease in its percentage with slight significant differences. The composition of fatty acids in the Zaity and Kaissy varieties shown in Table 5.

Triglycerides

Significant differences were found in the proportions of triglycerides during the different ripening stages of both the Zaity and Kaissy varieties Table 6.

The proportion of LLL triglycerides increased in the advanced ripening stages, with an average proportion at the beginning of ripening of 0.14% and reaching 0.18% in the Zaity variety. The increase was greater in the Kaissy variety, where it was 0.11% at the beginning of ripening and reached 0.24% in the advanced ripening stage. This is a relatively high proportion compared to Spanish and Italian olive oils, and average compared to Tunisian olive oil9. This confirms that the proportion of LLL triglycerides alone cannot be relied upon to detect olive oil adulteration with vegetable oils, as stated by Naasan (2009), who indicated that an increase of more than 0.23% indicates olive oil adulteration with vegetable oils by 1%17. our findings underscore the caution required when applying single triglyceride markers such as LLL proportion as definitive indices. Considering natural variation during ripening and varietal differences, multi-parameter approaches integrating triglyceride fingerprinting with advanced chromatographic and chemometric techniques yield enhanced reliability. These approaches mitigate the risk of false positives and improve the detection of subtle adulteration levels, providing a robust framework for quality assurance in oils from diverse origins and maturity stages28,29.

A difference in the percentage of PLnO triglycerides was also observed between the two studied varieties. While its percentage was almost constant in the olive variety, averaging 0.83%, it decreased from 0.92% to 0.87% in the advanced stages of ripening. The percentage of triglycerides OLO was also considered low in the olive variety compared to Tunisian and Italian oils9, and with average 11.56–14.19% for the olive and Kaissy varieties, respectively. The two studied varieties were characterized by moderate levels of triglycerides OOO, compared to Italian or Spanish olive oil, which are characterized by a high level of this percentage, sometimes reaching 59%, while in Tunisian oil it does not exceed 21.16%, according to several studies9,30. A significant increase in the OOO percentage was observed, from 31.46 to 31.67% in the Zaity and Kaissy varieties, respectively, at the beginning of ripening to 34.69–37.2% in the intermediate stage of ripening, and then a significant decrease to 29.43–34.47% as ripening progressed. This decrease was more pronounced in the Zaity variety than in the Kaissy variety. This can be attributed to the fact that the Zaity variety is an early-maturing variety compared to the Kaissy variety. Significant differences were also found in the percentage of triglycerides POO, which ranged from 27.4% to 27.86% for the olive and Kaissy varieties, respectively, and decreased to 25.82−21.11%. This is a high percentage compared to9 and consistent with what was found by30. A significant decrease in the percentage of triglycerides PPO was also observed in the Kaissy variety during the ripening stages, where its percentage was 5.24% and decreased to 3.08% at an advanced stage of ripening, while its decrease was less in the olive variety, where its percentage decreased from 5.14 to 4.7% at advanced stages of ripening. In general, its percentage is consistent with what was found by30 in Spanish olive oil and close to its percentage in Tunisian olive oil9. Table 6 shows the average percentages of triglycerides in the oil of the studied varieties according to the number of carbon atoms. A variation in the behavior of triglyceride POS was observed between the two studied varieties. While its percentage tended to increase in the olive variety, it decreased again at an advanced stage of maturity, averaging approximately 0.58%. In the Kaissy variety, a significant decrease was observed in its percentage, from 0.71% at the beginning of maturity to 0.51% at an advanced stage of maturity. As for triglyceride SOO, its percentage remained almost constant throughout the maturity stages in the Kaissy variety, averaging 5.31%. While its percentage increased significantly in the olive variety, from 5.92% at the beginning of maturity to 7.22% at the intermediate stage of maturity, and then decreased to 6.64% at the advanced stages of maturity. When studying the correlation between the percentage of LLL triglycerides and linoleic acid shown in Figure 3, it was noted that there was a medium positive correlation (75% > r2 = 0.574 > 50%) between linoleic fatty acid and LLL glycerides in the Kaissy variety and a weak positive correlation (r2 = 0.479 < 50%) in the olive variety. This confirms the necessity of taking into account the high content of linoleic acid in the oil of these varieties, which can give a greater value to the triglycerides with a number of carbon atoms of 42, of which LLL triglycerides are an essential part when determining the purity of the oil, according to what Naasan mentioned in 200917.

indicating that linoleic acid availability influences LLL triglyceride levels, but additional factors including enzymatic activities and environmental conditions modulate this relationship. This complexity is supported by recent analyses emphasizing the necessity to consider multiple biochemical parameters for accurate quality assessment and authenticity verification31,32.

The correlation between oleic acid and triglyceride OOO was also studied, as shown in Figure 4. The results showed a weak positive correlation (coefficient of determination r2 = 0.132 < 50%) in the Zeit variety and a weak negative correlation (r2 = 0.449 < 50%) in the Kaissyvariety between oleic acid and triglyceride OOO. Therefore, it is not necessary that if the percentage of oleic acid in the oil of the varieties is high, it will necessarily combine with glycerol to form OOO. Rather, it can combine in other forms to form other types of triglycerides, such as (POO, SOO), which were relatively high compared to Spanish and Italian olive oils. This observation aligns with the complex and dynamic nature of triacylglycerol biosynthesis in olives, where oleic acid although the predominant monounsaturated fatty acid in olive oil (typically 70–85% of total fatty acids), can be esterified at different positions on the glycerol backbone resulting in a diverse array of triglyceride molecules beyond OOO such as POO (palmitoyl-oleoyl-oleoyl) and SOO (stearoyl-oleoyl-oleoyl)33.

Conclusions

This study clearly demonstrates that the stage of fruit maturity and the choice of olive variety have significant impacts on the triglyceride and fatty acid composition particularly LLL, OOO, LOO, POO, and PPO. As well as the overall quality, of olive oil produced in Syria. The Zaity variety, with its higher oil content and earlier ripening, is optimal for oil extraction when harvested in November, ensuring both maximum yield and superior quality. In contrast, the Kaissy variety, characterized by greater fruit firmness and later maturation, allows for a more extended harvest period without compromising oil quality. Changes in triglyceride and fatty acid profiles during ripening highlight the importance of precise harvest timing to achieve desired oil characteristics and maintain authenticity. These findings provide valuable guidance for olive growers, producers, and quality control authorities, supporting improved harvest management and the production of high-quality, authentic Syrian olive oil. Future research should further explore the biochemical mechanisms underlying these compositional changes and extend the analysis to additional local varieties and environmental conditions.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

International olive council. Trade standard applying to Olive oils and Olive pomace oils. COI/T.15/NC 3/rev. (2025). 21 July. Madrid – España.

Nelson, D. L. & Cox, M. M. Lehninger, Principles of Biochemistry, 3rd edn (2000).

Gigoliott, C., Daghtta, A. & Sidoli, A. Study of Triglyceride Composition Seed Oils with High Acid Oleic Content. La Rivista Italian Della Sostanze Grasse vol. lxx (1993).

Santinelli, F., Daini, P. & Christie, W. W. The triacylglycerol structure of olive oil determination by silver ion high performance liquid chromatograph in combination with stereo specific analysis. Food Chem. 60, 425–432 (1992).

Karleskind, A. Manuel des Crops Gras, sous I´égide de I´Associiation Françaisen pour I´Etude des Crops Gras, Tec/Doc. Paris, 121–135–189–223 (1992).

Fedeli, E. Analysis of triglycerides in the determination of genuineness of olive oil. La. Rivista Italian Delle Sostanze Grasse 76, 245–247 (2001).

Kiritsakis, A. & Christie W.W. Analysis of Edible Oil Handbook of Olive Oil 130 (2000).

Mataix, F. H. & Martinez Victoria, Y. E. EI aceite de olive Bases para el futuro’’ Diputacion Provicial, Jaén (1988).

International Olive Council. World Olive Encyclopaedia (International Olive Council, 1996).

Boskou, D., Blekas, G. & Tsimidou, M. Olive oil composition, chemistry and technology. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 113, 41–72 (2006).

Yacein, A. Z., Serhroochni, M. & Hilali, S. Changes in the Fatty Acids Composition of Olive Oilat Different Stages of Olive Maturity; Case of the Tadla Region of Morocco. Olivae, No.94-December (2002).

Amelio, M. Chemical-physical Characteristics of Olive Oil (ONAOO, 2003).

Frega, N., Bocci, F. & Lercker, G. Composizione lipidica Della maturazone triglyceri ed acidi grassi. Rivista Italian Delle Sostanze Grasse 68, 69–74 (1991).

Cortesi, N., Fedeli, E. & Rovellini, P. HPLC triglycerides analysis for the detection of mixtures of high oleic seed oils with olive oil. Rivista Italiana Delle Sostanze Grasse. 75, 483–489 (1998).

Cert, A. & Moreda, W. Algorithms for the detection of hazelnut oil in Olive oil. Grasas Y Aceites. 51, 145–151 (2000).

Cert, A., Perez, Camino, M. C. & Moreda, W. Study of New Parameters for Detecting Hazelnut Oils and Olive Residues of Oils in Virgin and Refined Olive Oil 23–24 (J. Tecnicas del Aceite de Oliva, 2003).

Naasan, Z. Detection of adulteration in virgin olive oil using HPLC for triglycerides and GC/MS for volatile substances and colorimetric reagents, a thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Food Sciences 54 (Faculty of Agriculture, University of Damascus. Syria, 2009).

Abdine, M., Jbara, G., Contento, F. & Famiani, F. Characterization of Syrian Olive Varieties (GCSAR & CIHEAM- IAM, 2006).

Martinez, J. M., Mùnoz, E., Alba, J. & Lanzôn Informe sobre lautilizaciôn Del analizador derndiminto ABENCOR. Grasasy Acetes. 26(6), 379–385 (1975).

Jbara, G., Ashtar, S., Jawhar, A., Khatib, M., Bido, Z., Abdul Hamid, R. & Famiani,F. Oil quality and morphological, phenological, bio-agronomical and molecular characterization of Syrian Olea europea L. germplasm. Options Méditerranéennes. Série A: Séminaires Méditerranéens 73, 85–94 (2007).

International Olive Council. in Guide for the Determination of the CHaracteristics of Oil-Olives OI/OH/Doc. No 1 November (Madrid – España, 2011)

ISO. ISO 660 Determination of Acid Value and Acidity, 3rd edn, 9 (Switzerland, Geneva, 1996a).

ISO. ISO 3960 Determination of Peroxide Value, 4th edn, 9 (Switzerland, Geneva, 1996a).

Commission Regulation (EEC). No 268/91. On the characteristic of Olive Oil and Olive-residue Oil and thr Relevant Methods of Analysis 87 (OJL 248) (1991)

Uceda, M., Hermoso, A., Garcia Ortiz, A. & Jmenez, B. Intraspecific variation of oil contents and characteristics of oil in olive varieties. Acta Hort. 474, 652–659 (1999).

Aparicio, R. & Luna, G. Characterization of monovarietal virgin olive oil. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 104, 614–627 (2002).

Champolivier, L. & Merrien, A. Evolution De La Teneur En Huile Et De Composition En Acides Gras Chez Deux Varieties De Tournesol (Oléique Ou non) Sous I´effect De Temperatures Différentes Pendant La Maturation Des Grains 3140–144 (Oléagineux, Cops Gras, 1996).

Wei, H. et al. Accurate quantification of tags to identify adulteration of edible oils by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole-time of flight-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Res. Int. 165, 112544 (2023).

Hashempour-baltork, F. et al. Recent methods in detection of olive oil adulteration: State-of-the-art. J. Agric. Food Res. 16, 101123 (2024).

Bueno, E. O., Casas, J. S., Martinez, M. & Garcia, M. M. Estudio del contenido en triglicéridos de aceites monovarietales elaborados a partir de aceitunas en la regiόn extremeňa Grasas y Aceites, Vol. 54. Fasc 1–6 (2003).

El Yamani, M., Boussakouran, A. & Rharrabti, Y. Influence of ripening index and water regime on the yield and quality of Moroccan Picholine virgin olive oil. Ocl 27, 19 (2020).

Ghreishi Rad, S. A., Jalili, M., Ansari, F., Nodeh, R., Rashidi, L. & H., & Maturity impact on physicochemical composition and polyphenol properties of extra virgin olive oils obtained from manzanilla, arbequina, and Koroneiki varieties in Iran. Food Sci. Nutr. 11(9), 5396–5408 (2023).

Jimenez-Lopez, C. Bioactive compounds and quality of extra virgin olive oil. Foods 9(8), 1014 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the staff of the Department of Olive Research at the General Commission for Scientific Agricultural Research (GCSAR), Syria, for their invaluable support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.J and A.J. design of the Study, Project administration, Investigation. A.J. Methodology, data curation, writing original draft. M.G.E. statistical analysis. A.D. Written, Resources and writing, review and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jawad, M.A., Jawhar, A., Dakah, A. et al. Effect of maturity stages on triglyceride and fatty acid profiles in olive oil from Zaity and Kaissy varieties grown in Syria. Sci Rep 15, 35935 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20162-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20162-y