Abstract

Objectives

BMI and age are associated with the risk of osteoporosis (OP). The dynamic facial aging process involves changes in skin, muscle, fat, and facial bone structures, with facial skeletal aging affecting facial contours through volumetric reduction and morphological alterations. This study aims to develop and validate an explainable AI predictive model for opportunistic osteoporosis screening based on facial images.

Background

Effective identification of populations at risk for low bone mass and osteoporosis is crucial for implementing individualized screening strategies and subsequent orthopedic care. Although artificial intelligence technology demonstrates broad prospects and excellent performance in disease prediction using imaging data, its application in osteoporosis risk prediction utilizing facial data remains insufficiently explored and developed. We propose an explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) deep learning model named Face2Bone for osteoporosis risk prediction and opportunistic screening of at-risk populations based on 2D facial images. In this study, we conducted proof-of-concept validation by establishing predictive models and integrating XAI methods to identify and comparatively analyze facial phenotypic factors associated with osteoporosis.

Methods

An observational study of 1167 patients undergoing DXA (in March-August 2024) was conducted at Ningbo No.2 Hospital. Standardization for facial images and the collection of clinical data were performed. A preprocessing pipeline was created to remove the background noise from the facial images. A hybrid deep learning model was constructed with a pre-trained FaceNet, a custom Frequency Sparse Attention (FSA) module, a Transformer and CNN backbones, and a Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN) as the classifier. The models’ interpretability was analyzed using SHAP and CRAFT interpretation methods.

Results

The Face2Bone model demonstrated superior performance in the validation set, achieving accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score of 92.85%, 92.94%, 92.85%, and 92.83%, respectively, with an AUC of 98.56%, outperforming mainstream models including VGG, ViT, and ResNet. The model maintained excellent classification performance and calibration across both male and female subgroups (ECE = 0.027, Brier score = 0.050, all subgroup Hosmer–Lemeshow test \(P\)-values > 0.05). Explainability analysis using SHAP and CRAFT revealed, for the first time, significant facial image characteristics across three bone mass states (normal, osteopenia, osteoporosis), confirming morphological consistency between model classifications and facial skeletal aging patterns.

Conclusion

We created and validated the first explainable deep learning model for osteoporosis risk classification using facial images. Facial characteristics associated with bone loss represent changes to the skeleton that are expected with normal aging. This non-invasive technology allows for opportunistic screening and early intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) and osteopenia are complex, multifactorial systemic metabolic bone disorders with a worldwide prevalence1,2. These conditions are characterized by low bone mass and deterioration of bone microarchitecture, which leads to increased bone fragility and susceptibility to fractures3. Hip fractures and vertebral fractures represent the most severe consequences of osteoporosis. In China, the prevalence of osteoporosis reaches 19.2% in individuals aged over 50 years and escalates to 32% in those over 65 years4. Against the backdrop of an increasingly aging population, osteoporosis in middle-aged and elderly populations demonstrates significant comorbidity with geriatric syndromes. These conditions severely compromise functional capacity and quality of life in the elderly, imposing substantial burdens on individuals, families, society, and healthcare systems5,6. Consequently, osteoporosis has emerged as a critical global public health challenge.

Early screening for osteoporosis and osteopenia is crucial for addressing this public health challenge. Quantitative computed tomography (QCT) and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) are the primary modalities for osteoporosis risk assessment in clinical practice7,8,9. However, widespread adoption of these techniques in primary healthcare settings is significantly constrained by multiple factors, including complex processing technologies, high equipment costs, a shortage of qualified technicians, and patient compliance issues10. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop a convenient, cost-effective, practical, and reliable screening tool for osteoporosis risk assessment.

Compared to the limitations of screening methods such as QCT and DXA (e.g., radiation exposure, equipment dependency, and cost considerations), facial images have been widely applied in medical fields due to their non-invasive nature, accessibility, and ability to comprehensively reflect facial aging processes and individual health status, including studies on facial aging11, metabolic diseases12, and nutritional status13,14,15,16. Osteoporosis, as a systemic bone metabolic disease, not only affects axial and weight-bearing bones but also significantly involves craniofacial skeleton17, leading to reduced bone density and morphological changes. Changes in facial bone morphology and volume affect the support and appearance of facial soft tissues, primarily manifesting in four important facial regions: periorbital, midface, perinasal, and mandibular areas. For example, facial flattening, soft tissue ptosis, deepened nasolabial folds, nasal tip ptosis, reduced visible eye area, and maxillomandibular resorption are considered specific morphological changes occurring during facial skeletal aging18,19,20,21, and these changes may indirectly reflect systemic bone health status through facial images. One study found that mandibular bone density in postmenopausal women was significantly correlated with hip and spinal bone density22 indicating that craniofacial skeleton can serve as an indicator of systemic bone health. Another study using three-dimensional CT analysis confirmed that mandibular and maxillary bone loss during aging was related to systemic bone density decline23, which could lead to facial contour changes24, such as zygomatic prominence and facial hollowing. Research on facial skeletal aging has revealed that facial bone density changes follow patterns similar to axial bone density changes, with significant reduction during aging, particularly in the midface and mandibular regions, and this pattern is more pronounced in osteoporosis patients23. These studies indicate that the direct effects of osteoporosis on facial skeleton can be manifested through facial morphological changes, providing theoretical basis for facial screening. Meanwhile, both osteoporosis and skin aging are associated with collagen loss25, sharing common pathological mechanisms. Skin collagen content shows significant correlation with bone mass changes, particularly in postmenopausal women, where estrogen decline significantly affects collagen content in both skin and bone, suggesting that collagen loss caused by osteoporosis may be indirectly reflected through facial skin aging features (such as wrinkles or laxity), providing additional evidence for using facial images in osteoporosis screening. Furthermore, multiple studies have confirmed the association between BMI and BMD26,27,28, with each standard deviation increase in BMI corresponding to a 0.087 standard deviation increase in lumbar spine BMD (p = 0.006). Based on this association, 2D facial image analysis technology provides a novel non-invasive method for osteoporosis risk screening by identifying BMI-related facial geometric morphological features (such as facial contours and fat distribution)29. This technology can quantify facial features and establish BMI prediction models, thereby indirectly reflecting individual BMD levels, with its convenience and accessibility providing potential solutions for large-scale osteoporosis screening.

Although the aforementioned evidence has established a theoretical foundation for the application of facial images in osteoporosis screening, no studies have directly utilized facial images for bone mass status assessment, reflecting that this field remains in the exploratory stage. Given that these facial features are influenced by numerous factors when used for osteoporosis risk screening, including: (I) limited variety of relevant facial features with inconspicuous symptoms and facial characteristics in early disease stages; (II) lack of specific definitions and quantifiable severity grading criteria; and (III) poor reproducibility of human visual recognition. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a comprehensive tool that integrates all facial features associated with osteoporosis or osteopenia risk to enhance screening accuracy and reliability, and to fill the current research gap.

With the advancement of artificial intelligence, deep learning algorithms have emerged as powerful tools for disease screening, diagnosis, and prediction based on facial images, particularly for cancers, endocrine disorders, and genetic diseases. These algorithms enable computers to solve complex problems by leveraging neural network architectures30. Characterized by abundant neurons, multiple layers, and intricate connectivity, these networks can automatically transform raw input data into meaningful features, thereby achieving pattern recognition.

Deep learning techniques have been widely applied to osteoporosis screening and diagnosis in recent years. Current research primarily utilizes radiological data (CT, X-ray, quantitative ultrasound [QUS], MRI) or combines clinical baseline characteristics with deep learning for opportunistic osteoporosis screening31. Demonstrating promising performance. However, these approaches predominantly focus on osteoporosis detection while neglecting critical issues in vertebral localization and segmentation—data acquisition and annotation processes burden radiologists significantly32,33. Moreover, regarding clinical translation, deep learning models relying on clinical or radiological examination data exhibit limited accessibility and convenience for patients. The substantial operational and learning costs hinder model implementation, often overlooking patient-centered development principles34. Furthermore, current methods typically frame osteoporosis as a binary classification problem, failing to address the clinically important ternary classification (osteoporosis, osteopenia, and normal bone mass). Although tripartite classification presents greater technical challenges, incorporating osteopenia and normal bone mass status is crucial for osteoporosis prevention, early diagnosis, public health burden reduction, and raising population awareness.

Therefore, we propose a deep learning-based ternary classification model for opportunistic osteoporosis screening using facial images. Given the absence of prior research on osteoporosis prediction via facial imaging, we incorporate explainable AI (XAI) methods to perform interpretability analysis of our deep learning model. This study aims to: (1) develop and validate a deep learning algorithm capable of opportunistic screening for osteoporosis, osteopenia, and normal bone mass using facial images; and (2) investigate whether facial skeletal aging correlates with systemic bone mineral density changes.

Methods

Study design

We conducted an observational, prospective, randomized sampling study involving patients who underwent DXA scans at the Bone Density Department of Ningbo No.2 Hospital between March and August 2024, collecting clinical baseline data and facial images. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision) and received prior ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of Ningbo Second Hospital (Approval No. SL-NBEY-KYSB-2024–181-01). All participants provided written informed consent compliant with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision). The study follows the Standards for Reporting Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (STARD 2015) guidelines.

Study participants

From March to August 2024, a total of 1167 patients were enrolled in this study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) postmenopausal women; (2) men aged > 50 years; (3) complete DXA examination available. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients or guardians unwilling to provide written informed consent; (2) patients with diseases affecting facial color other than anemia (such as jaundice, vitiligo, lupus erythematosus, or other skin lesions); (3) patients with bone density data from only lumbar vertebrae (LV) or neck of femur (NOF); (4) bedridden patients or those with previous lumbar spine or hip surgery (joint replacement or percutaneous vertebroplasty, PVP) that could affect bone density data; (5) patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS); (6) patients with cognitive impairment; (7) patients who had previously undergone surgery that could significantly affect facial color, blood flow, or structure (such as cosmetic surgery, jaw reconstruction, or skin grafting).

Data collection

Baseline questionnaire interviews were conducted to collect information on age, gender, height, weight, and BMI, and each patient was assigned a unique ID number to facilitate data traceability and anonymization.

Diagnostic criteria for osteoporosis

The diagnosis of osteoporosis and osteopenia was based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria35. For postmenopausal women and men aged ≥ 50 years, a T-score ≤ − 2.5 SD was diagnosed as osteoporosis, T-score > − 1.0 SD was considered normal bone mass, and T-score between -1.0 SD and -2.5 SD was classified as osteopenia. For premenopausal women and men aged < 50 years, a Z-score < − 2.0 SD indicated bone mass below the expected age range, while Z-score ≥ − 2.0 SD was considered normal bone mass. Following the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) recommendations36, we applied the "lowest T-score rule," using the lowest T-score from all measured sites as the basis for final diagnostic classification.

Image acquisition

DXA scanning

All DXA examinations were performed by certified technicians under the supervision of professional radiologists, strictly adhering to standardized operating procedures. We used a GE Prodigy Primo Lunar DXA scanner (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI, USA), with daily calibration using manufacturer-provided phantoms and strict quality control measures implemented. Regions of interest (ROI) for bone density measurements included L1-L4 lumbar spine, femoral neck, and total hip. Examination reports were generated using enCORE™ 2011 software (version 13.6, GE Healthcare), and all DXA scan results underwent dual review by two certified radiologists to ensure diagnostic accuracy and reliability.

Facial image acquisition

Under standardized lighting conditions, we captured frontal facial images of participants using the rear camera of an iPad 13.1 (Apple Inc.). Consistent ambient illumination was maintained throughout image acquisition. During photography, participants were seated in a fixed-position chair against a white wall background, with the imaging device maintained at a standardized distance and height from the subject to minimize imaging variability. Participants were instructed to: (1) remove eyeglasses and hats; (2) ensure no hair occlusion of the forehead; and (3) maintain open eyes with neutral facial expressions—all to guarantee image consistency and stability.

Image preprocessing

Although quality control was implemented during image acquisition, we used MediaPipe37 for image preprocessing to eliminate the influence of confounding factors such as facial pose, body contours, or subject clothing. MediaPipe (version 0.8.9.1) is an open-source cross-platform multimedia processing framework developed and released by Google in 2019 for building machine learning-based applications, covering computer vision, audio processing, pose estimation, and other domains. As an integrated machine learning vision algorithm toolkit, MediaPipe was utilized in this study specifically for its face detection and face alignment modules for image preprocessing.

The image preprocessing pipeline is illustrated in Fig. 1, beginning with constructing a face detector using MediaPipe’s BlazeFace Sparse (Full Range) model, which detects facial regions in the images. Subsequently, a facial mesh object is constructed based on the detected 468 facial landmarks to determine facial pose, followed by masking with a black background filling, resulting in a segmented elliptical facial region of 512 × 512 pixels. Through facial standardization, we can reduce noise in the facial image background, focusing solely on the facial region.

Data augmentation

We employed the Albumentations library38 to perform data augmentation on original facial images, utilizing various non-rigid and non-destructive image transformation techniques to expand the sample set, thereby enhancing the model’s generalization capability and robustness. Specific augmentation strategies included: horizontal flipping (HorizontalFlip), vertical flipping (VerticalFlip), affine transformation (Affine), and Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE).

Development of the models

This study proposes a pre-trained supervised Face2Bone ternary classification diagnostic network for opportunistic screening of early-stage osteoporosis, with subsequent explainable AI analysis. Figure 2 illustrates the overall network architecture. The Face2Bone network processes input facial images through two parallel pathways: (I) Facial contour features are extracted using the pre-trained FaceNet backbone model39, (II) Facial image features are extracted through a feature extraction module composed of FSA blocks, where the Spatial Supervision Attention Module (SSAM) utilizes pre-extracted facial contour features to compute attention weights for relevant facial features, with final ternary classification performed using a KAN network40 as the classifier. Post-training, the model was interpreted locally and globally using XAI techniques.

Background knowledge

Multi-head self-attention, MSA

The Transformer model41. It is built upon multi-head self-attention (MSA), enabling the model to capture long-range dependencies between tokens at different positions. Specifically, let \(\boldsymbol{\rm X}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N\times D}\) Denote the input sequence to a standard multi-head self-attention layer, where \(N\) Is the sequence length, \(D\) Represents the number of hidden dimensions. Each self-attention head computes query \({\varvec{Q}}\), key \({\varvec{K}}\) and value \({\varvec{V}}\) matrices through linear transformations of \(\boldsymbol{\rm X}\):

where \({{\varvec{W}}}_{q},{{\varvec{W}}}_{k},{{\varvec{W}}}_{v}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{D\times {D}_{h}}\) Are learnable parameter matrices, and \({D}_{h}\) Is the hidden dimension size per head? Then, the output of a single self-attention head is a weighted sum of \(N\) Value vectors:

For a multi-head self-attention layer with \({N}_{h}\) heads, the final output is obtained by concatenating the outputs of each self-attention head and applying a linear projection, which can be expressed as:

where \({W}_{o}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{\left({N}_{h}\times {D}_{h}\right)\times D}\) It is a learnable parameter matrix. In practice, \(D\) It is usually set to \({N}_{h}\times {D}_{h}\).

Transformer block

A standard Vision Transformer (ViT)42, as shown in Fig. 3, consists of a patch embedding layer, several transformer blocks, and a prediction head. Let \({\ell}\) Be the block index. Each block contains a Multi-head Self-Attention (MSA) layer and a Position-wise Feed-Forward Network (FFN), which can be expressed as:

where \(LN\) stands for LayerNorm43, and \(FFN\) consists of two fully connected layers with GELU \(\text{ ADDIN ZOTERO}\_\text{TEMP }\) Nonlinearity. Recent work on ViT proposes to divide the block into several phases (usually four stages) to generate a pyramid feature map for intensive prediction tasks.

FaceNet

FaceNet39. Proposed by Google in 2015 is a deep learning-based face recognition system that directly trains a deep convolutional neural network to map facial images into a 128-dimensional Euclidean space (embedding). The distance between different facial images in this space correlates with their similarity. The backbone of FaceNet employs Inception-ResNetV144. or MobileNetV145. Deep learning networks automatically learn complex facial features and extract highly abstract feature vectors through multiple convolutional and pooling operations. This study uses the pre-trained FaceNet network as the backbone for the supervised branch’s feature extraction. The facial features extracted by FaceNet are used to compute attention weights for the image features extracted by the image feature extraction branch, ensuring that the final output features are face-related.

Module descriptions

This section provides detailed descriptions of each component in the Face2Bone network.

FSA (frequency sparse attention) module

As previously introduced, the standard self-attention mechanism in Transformers has become an empirical operation in most existing models. Given query \({\varvec{Q}}\), key \({\varvec{K}}\), and value \({\varvec{V}}\) with dimensions \({\mathbb{R}}^{L\times d}\), the output of dot-product attention is typically formulated as:

Typically, multi-head attention is implemented on each new \(Q\), \(K\), and \(V\), producing output channel dimensions of \(d=C/k\), which are concatenated and then projected through a linear layer to obtain the final result for all heads. It should be noted that this standard self-attention paradigm is based on dense fully connected operations, requiring the computation of attention maps for all query-key pairs. However, this process is filled with information redundancy in facial images. To address this, we designed a Frequency Sparse Attention (FSA) module that removes feature space information redundancy and then processes high and low-frequency features separately. This enhances facial skin features with high-frequency texture detail while reducing low-frequency non-texture features, thereby better preserving face-related characteristics.

Specifically, the channel context is first encoded by applying a 1 × 1 convolution followed by a 3 × 3 depthwise convolution. Self-attention is applied on the channel rather than the spatial dimension to reduce time and memory complexity. Subsequently, the similarity between all reshaped query and key pixel pairs is calculated, and in the transposed attention matrix \(M\) with size \({\mathbb{R}}^{\overline{c }\times \overline{c} }\) Unnecessary elements with lower attention weights are masked out. Unlike the dropout strategy that randomly discards scores, an adaptive selection of \(top-k\) contribution scores are implemented on \(M\), aiming to retain the most important components while removing the useless ones. Here, \(k\) Is a tunable parameter that dynamically controls the degree of sparsity, formally obtained through weighted averaging of appropriate scores. Therefore, only the \(top-k\) values of each row in \(M\) Within the range \(\left[{\Delta }_{1},{\Delta }_{2}\right].\) They are normalized for softmax computation. For other elements with scores lower than the \(top-k\). Their probabilities are replaced with 0 at given indices using the scatter function. This dynamic selection transforms the attention from dense to sparse, as derived by the following equation:

where \({\mathcal{T}}_{\text{k}}\left(\cdot \right)\) is a learnable \(top-k\) Selection operator:

The result is obtained by matrix multiplication with softmax and value. Due to the multi-head strategy, the outputs from all attention heads are concatenated and then projected through a linear layer to obtain the sparse feature results of the facial image. High/low-frequency components in the sparse feature map are processed separately in the attention layer. Essentially, the low-frequency attention branch aims to capture global dependencies of the input sparse features, which does not require high-resolution feature maps but necessitates global attention. On the other hand, the high-frequency attention branch is designed to capture fine-grained local dependencies, which requires high-resolution feature maps but can be accomplished through local attention.

High-frequency attention

Intuitively, since high frequencies encode local details of objects, applying global attention to feature maps is redundant and computationally expensive. Therefore, high-frequency attention46 is utilized to capture fine-grained high frequencies through local window self-attention (e.g., 2 × 2 windows), significantly reducing computational complexity.

Low-frequency attention

Recent studies have demonstrated that global attention in MSA helps capture low frequencies47,48. However, applying MSA to high-resolution facial sparse feature maps requires significant computational costs. Since average pooling acts as a low-pass filter, low-frequency attention first applies average pooling to each window to obtain low-frequency signals from the input \(X\). Subsequently, the average-pooled feature maps are projected into keys \({\varvec{K}}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N/{s}^{2}\times {D}_{k}}\) and values \({\varvec{V}}\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N/{s}^{2}\times {D}_{n}}\), where \(s\) is the window size. The query \({\varvec{Q}}\) in low-frequency attention, it still originates from the original sparse feature map \({\varvec{X}}\). Then, standard attention is applied to capture the rich low-frequency information in the sparse feature map.

High-frequency attention divides the same number of heads in MSA into two groups according to the split ratio \(\alpha\), where \(\left(1-\alpha \right){N}_{h}\) Heads are allocated to the high-frequency branch, and the remaining \(\alpha {N}_{h}\) heads are assigned to the low-frequency branch. By doing so, since the complexity of each attention is lower than that of standard MSA, the entire frequency-domain feature enhancement framework ensures low complexity and guarantees high throughput on GPUs. Finally, the output of FSA is the concatenation of the outputs from both low-frequency and high-frequency attention.

SSAM (spatial supervised attention module)

After the FSA module extracts rich, sparse frequency-domain image features, they are divided into bold italic cap Q sub cap F and bold italic cap V sub cap F, respectively. The facial supervision features extracted by FaceNet are divided into K sub-cap \({K}_{F}\), and attention is calculated through MSA to obtain the supervised facial frequency-domain features. The core of the Spatial Supervised Attention Module (SSAM) lies in combining the FSA module with the pre-trained FaceNet through the QKV mechanism, enhancing the accuracy of feature extraction through channel supervision.

Assuming the features extracted by the FSA module are \({{\varvec{F}}}_{0}\in C\times H\times W\) and the facial features extracted by FaceNet are \({{\varvec{F}}}_{1}\in L\). The facial features are transformed as follows:

where \({f}_{unsqueeze}\left(\cdot \right)\) is the dimension expansion operator and \({f}_{linear}\left(\cdot \right)\) Is the linear mapping operator. Meanwhile, the features extracted by the FSA module are transformed as follows:

where \({f}_{relu}\left(\cdot \right)\) Is the activation layer and \({f}_{conv}\left(\cdot \right)\) It is the convolutional layer. Finally, the spatial-channel self-supervised result is obtained as follows:

where \(MSA\left(\cdot \right)\) represents the Multi-head Self-Attention mechanism.

The SSAM module captures spatial structural dependencies and global semantic information in face recognition through two sub-modules: spatial self-attention and channel self-attention. This network architecture is simple yet effective, enabling accurate facial feature prediction. Furthermore, the SSAM module introduces a novel structural position encoding method that defines a set of structural positions based on geodesic distances. It divides facial features into multiple parts and encodes the features of each part using the same structural position encoding. This encoding method can reflect the structural characteristics of the face and improve face recognition performance.

Kolmogorov-Arnold networks

MLP49,50. The fully connected feedforward neural network is the fundamental building block of deep learning models and is commonly used in machine learning to approximate nonlinear functions. An MLP consisting of \(K\) layers can be described as the action of the transformation matrix \(W\) and activation function \(\sigma\). Its mathematical form is as follows:

Despite the widespread application of MLPs in deep learning models, they also have significant drawbacks. Due to fixed activation functions and linear combinations, MLPs face issues such as large parameter counts, computational complexity, catastrophic forgetting, and poor interpretability when processing high-dimensional image data51. Recently, Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks (KAN)40. Have been proposed as an alternative to traditional Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs). Unlike MLPs based on the universal approximation theorem, KANs are inspired by the Kolmogorov-Arnold representation theorem. KANs share a similar fully connected structure with MLPs. Still, unlike MLPs, which rely on fixed activation functions at each node, KANs introduce learnable activation functions on the edges, fundamentally changing the neural network architecture by utilizing learnable one-dimensional spline functions and eliminating linear weight matrices. Similar to MLPs, a \(K\)-Layer KAN can be described as the nesting of multiple KAN layers, with its mathematical description as follows:

where \({\Phi }_{i}\) represents the \(i\)-th layer of the KAN network. Each KAN layer has \({n}_{in}\) dimensional input and \({n}_{out}\) Dimensional output. \(\Phi\) consists of \({n}_{in}\times {n}_{out}\) Learnable residual activation functions \(\upphi\), which can be expressed as:

The residual activation function \(\phi\) Is defined as:

where \(w\) is the weight, \(b(x)\) Is the basis function used to ensure smoothness, and \(spline(x)\) is the spline function. The basis function \(b(x)\) is defined as:

The spline function \(spline(x)\) is parameterized as a linear combination of \(B-splines\), such that:

where \({c}_{i}\) They are trainable parameters. The KAN network from the layer \(k\) to layer \(k+1\) Can be described as:

Based on these contents, we replace the MLP layers with KAN layers in the Face2Bone model architecture to enhance the model’s classification performance and interpretability for facial images, thereby improving its representation capability.

Statistical analysis

This study subjected categorical variables to one-hot encoding, while continuous variables were standardized using Z-score normalization. Continuous variables were presented as mean \(\pm\) standard deviation (\(Mean\pm SD\)) or median (IQR), while categorical variables were described using frequency n (%). The Shapiro–Wilk test (significance threshold \(P\)<0.01) was employed to assess the normality of continuous variables. Intergroup comparisons were conducted using: ① independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U test; ② chi-square test (Fisher’s exact test when \(E\)<5). Model diagnostic performance was evaluated using AUC, predictive values, accuracy, recall, F1-score, and Kappa coefficient. Data analysis was implemented using Python 3.12 (SciPy 1.11, scikit-learn 1.4).

Results

Experimental settings

In this study, we randomly divided the dataset into training (n = 832) and validation (n = 208) sets at an 8:2 ratio, ensuring that all images from the same patient were allocated to a single dataset to prevent data leakage, and employed stratified random sampling to maintain consistent proportional distribution across the three bone mass states52. Based on this foundation, we further stratified the overall dataset by gender, creating male (n = 286) and female (n = 754) subgroups to evaluate the model’s generalization performance and clinical applicability across different gender populations.

The experiment was implemented using the PyTorch deep learning framework, with Visual Studio Code as the integrated development environment (IDE). The experimental platform used the Ubuntu 22.04 operating system, CUDA 12.1, and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3080 GPU to support model training and inference. To ensure experimental reproducibility, the random seed was set to 42, training epochs were set to 150, and batch size was set to 32.

During model training, original images were uniformly resized to 224 × 224-pixel resolution using bilinear interpolation and underwent standardization processing. Model optimization employed Cross-Entropy Loss, Adam optimizer, and OneCycle LR dynamic learning rate adjustment strategy. The initial learning rate was set to \(1e-3\), gradually increasing to a maximum of 0.001 during the warm-up phase (30%), and gradually decreasing to 0.000001 during the annealing phase (70%) to avoid local optima traps and promote model convergence. To prevent overfitting, the early stopping mechanism was introduced, terminating training when the validation set accuracy showed no relative improvement exceeding 5% for 10 consecutive epochs.

Study population

From March to August 2024, this study collected baseline data and facial image information from 1,167 patients according to inclusion criteria, including 360 males (31%) and 807 females (69%). 127 patients with unqualified facial images were excluded during the data cleaning phase. Among the remaining 1,040 patients were 370 patients with normal bone mass, 434 with osteopenia, and 236 with osteoporosis. The baseline demographic characteristics of the training and validation sets are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 4. In this study, significant statistical differences (\(P\)<0.001) were observed in age, gender, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) among the normal bone mass group, osteopenia group, and osteoporosis group. The non-osteoporosis group showed significantly higher BMI than the osteoporosis group, with lower proportions of female patients and younger age than the osteoporosis group (Fig. 5). In this study, we also compared the average faces across normal bone mass, osteopenia, and osteoporosis datasets. After preprocessing, the facial images of the three bone mass states were sorted and displayed according to BMD values (Fig. 6). Statistical significance (\(P\)<0.05) was observed in BMD among all three groups. We also employed XAI methods to analyze the model’s output interpretability, aiming to capture distinguishable facial features and model-attended feature regions across the three different bone mass states.

Evaluation metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance on the dataset, we employed the following evaluation metrics: accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score53, AUC, and Kappa coefficient. These evaluations were calculated using the following formulas:

where TP (True Positive) represents the number of positive samples correctly predicted by the model, TN (True Negative) represents the number of negative samples correctly predicted by the model, FP (False Positive) represents the number of negative samples incorrectly predicted as positive by the model, FN (False Negative) represents the number of positive samples incorrectly predicted as negative by the model. \({p}_{o}\) is the observed classification agreement (accuracy), and \({p}_{e}\) is the expected agreement by random classification.

Additionally, we used calibration curves, Expected Calibration Error (ECE)54, and Brier Score (BS) to evaluate the model’s calibration performance, and employed the Hosmer–Lemeshow (HL) goodness-of-fit test to assess its calibration ability.

Comparison experiment

In this study, we systematically evaluated the classification performance of the Face2Bone model against several mainstream deep learning models across different bone mass states. As shown in Table 2, the Face2Bone model outperformed other models across all evaluation metrics, demonstrating excellent performance in osteoporosis prediction. Specifically, our model achieved an accuracy of 92.85%, significantly higher than VGG16 (87.13%), VGG19 (83.16%), ResNet18 (85.83%), and ResNet34 (87.82%). Regarding precision, Face2Bone reached 92.94%, 4.48% higher than the second-best model, VGG16. For recall and F1-score, Face2Bone achieved 92.85% and 92.83%, respectively, significantly surpassing other comparison models. Particularly noteworthy is our model’s outstanding performance in AUC value (98.56%) and Kappa coefficient (88.87%), indicating that Face2Bone possesses superior classification capability and higher diagnostic consistency.

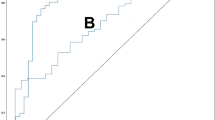

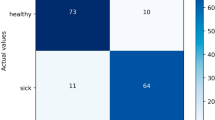

In Table 3, the Face2Bone model demonstrated high accuracy and stability in classifying different bone mass states. To further evaluate the model’s classification performance, we plotted the confusion matrix (Fig. 7) and ROC curves (Fig. 8). Our model achieved an overall AUC of 95.86%, with particularly impressive performance in osteoporosis classification: 98.28% AUC, 86.61% recall, and 94.06% precision, demonstrating extremely high sensitivity and specificity for identifying high-risk patients. Meanwhile, error analysis revealed that the model still had some misclassifications at the boundary between osteopenia and osteoporosis (9.34% misclassified as osteopenia, 1.89% misclassified as osteoporosis), possibly due to overlapping facial features between these two patient groups.

Furthermore, we conducted model performance evaluation on male and female subgroup cohorts in this study, with gender stratification revealing population differences in model performance (Table 4). The female subgroup demonstrated overall superior classification performance compared to the male subgroup, which was related to the imbalanced gender distribution in our dataset. Despite these differences, performance across gender stratifications reached clinically acceptable levels, indicating that the Face2Bone model possesses good generalization capability across different gender populations.

Given the importance of osteoporosis classification prediction in clinical risk assessment, this study further evaluated the model’s calibration performance (Fig. 9). The HL test assesses model calibration quality by comparing consistency between predicted probabilities and observed outcomes, with \(P\)-values > 0.05 indicating good calibration performance. Through comparative analysis of calibration performance across different validation sets and bone mass states, the overall cohort demonstrated optimal calibration performance (ECE = 0.027, Brier Score = 0.050, \(\chi^{2} = {3}.{91}\), \(P\)=0.418), followed by the female subgroup (ECE = 0.040, Brier Score = 0.074, \(\chi^{2} = 4.15\), \(P\)=0.528), while the male subgroup, despite its smaller sample size, maintained good calibration (ECE = 0.036, Brier Score = 0.049, \(\chi^{2} = 1.{07}\), \(P\)=0.585). All validation sets showed HL test \(P\)-values above the 0.05 threshold, indicating that the Face2Bone model achieved statistically significant good calibration across different populations, ensuring the reliability of predicted probabilities and safety of clinical applications. This consistent calibration performance is of great significance for probability-based clinical decision support, enabling clinicians to trust the model’s probabilistic predictions and make more accurate osteoporosis risk assessments.

Overall, the model comparison results demonstrate the feasibility and potential application value of the Face2Bone model in opportunistic osteoporosis screening. Compared to traditional diagnostic methods like DXA, our approach provides a non-invasive, cost-effective, and convenient alternative for early osteoporosis screening, offering an innovative technical pathway for preventive medical intervention and public health management in osteoporosis.

Ablation experiment

To demonstrate the effectiveness of the modules proposed and designed in this study, and to deeply reveal the contribution of each component of the Face2Bone model and its impact on overall performance, we designed a series of ablation experiments. By selectively removing or disabling key modules in the model, we tested and validated the impact of the FSA module, SSAM module, and KAN network classification head on model performance. The comparison results, as shown in Table 5 and Fig. 10, indicate that all three modules positively influenced the model’s classification performance. All experimental configurations used the same training and validation datasets and experimental parameters to ensure result comparability.

Ablation study of the FSA module

The FSA module serves as the core component of the model, integrating residual layers, Top-K attention mechanism, and high-low frequency feature processing through cascade connections to construct a facial image feature extraction network for different bone mass states. It processes features at different scales and abstraction levels across four feature layers (Layer1-Layer4), achieving spatial-frequency dual-domain analysis capability for facial images. When this module was removed, the model’s performance significantly declined, with overall accuracy dropping from 92.85% to 61.34%, a performance decrease of 37.79%. The F1-score decreased from 92.83% to 57.75%, and precision dropped from 92.94% to 69.51%. Notably, the FSA module is crucial for identifying the osteopenia category, with its F1-score dropping from 93.37% to 43.11% after removal, a substantial decrease of 53.83%. This indicates that the FSA module can effectively capture subtle facial image features of patients in the intermediate osteopenia state and efficiently integrate feature information from different levels, enhancing the model’s comprehensive understanding of facial osteoporosis features, particularly in improving the efficiency of integrating features from different facial regions.

Ablation study of the SSAM module

The SSAM module establishes correlation interactions between feature maps and FaceNet embedding vectors through the QKV mechanism, combining feature maps with embedding vectors to establish associations between facial structure and facial image representations of different bone mass states, thereby enhancing the model’s ability to identify facial osteoporosis features. After removing this module, the model’s overall accuracy decreased by 4.91%, the F1-score dropped to 87.95%, with a performance decrease of approximately 5.26%. The SSAM module’s impact on different categories was relatively balanced, revealing its ability to establish correlations between facial structure and overall facial image representation features. Particularly for the osteoporosis category, removing the SSAM module caused its F1-score to decrease from 92.29% to 86.5%, a decrease of 4.2%, indicating that the SSAM module possesses unique advantages in capturing facial features of osteoporosis patients.

Removal of KAN classification head

The KAN network serves as the classification head in the Face2Bone model, where high-order nonlinear function approximation enhances the model’s ability to express complex feature relationships. After removing KAN and replacing it with traditional linear layers (MLP), the model’s overall accuracy decreased by 3.1%, the F1-score dropped to 89.74%, with a performance decrease of approximately 3.33%. KAN’s contribution to the overall model was relatively smaller than that of the other two modules. However, it still significantly improved the model’s classification capability for the normal bone mass category. After removing KAN, the F1-score for the Normal category decreased from 93.82 to 90.71, revealing that KAN can enhance the model’s boundary judgment ability and adaptive nonlinear mapping capability for different bone mass states in facial images, enabling it to handle the complex nonlinear relationships between facial features and bone mineral density across different bone mass states.

Analysis of inter-module coordination effects

As shown in Fig. 11, we used the F1-score as a metric to measure the actual contribution of model components. We found significant synergistic effects among the three modules. The base model (with FSA removed) achieved an F1-score of 57.75%. After adding the SSAM module, it increased by 4.88% to 62.63%. Further addition of the KAN module increased it by 3.09% to 65.72%. Finally, adding the FSA module improved it by 27.11% to 92.83%. This indicates that the relationship between modules is not simply additive but achieves synergy through information complementarity and feature enhancement. Although the KAN module’s contribution was relatively smaller in this process, its combination with SSAM and FSA models produced significant synergistic effects, further demonstrating the effectiveness of KAN in visual tasks55,56.

Furthermore, this study found that compared to osteopenia, which represents an intermediate disease progression, the recognition of facial images from osteoporosis patients demonstrated higher robustness. Even in the simplified model with the core FSA module removed, this category maintained relatively high performance (F1 = 66.67%), indicating that the facial representations of osteoporosis patients are more distinctive and can still be partially recognized even in simplified models. The normal bone mass category showed good balance across all modules, with all three modules contributing to its overall accuracy. Particularly in the model with the FSA module removed, although the accuracy (55.64%) significantly decreased, the recall rate (91.9%) remained high. This asymmetry reveals that the model tends to classify more samples as positive after losing the core FSA module, leading to a high false-positive rate.

Analysis of explainability

In the medical field, explainable AI technology has been widely applied57. For medical tasks, explainability encompasses factors not considered in other domains, including risk, responsibility, and ethics. As emphasized by the FAT (Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency) principles58, the purpose of explainability in AI algorithm black boxes is to "ensure that algorithmic decisions and any data driving those decisions can be explained in non-technical terms to end users and other stakeholders." Related studies in medical scenarios such as non-invasive detection59, skill assessment60, disease prediction61, and risk analysis62 have further confirmed the critical role of explainability in clinical decision-making. In this study, we employed two explainability methods for interpretive analysis of model results: SHAP63 and CRAFT64, enhancing the reliability and credibility of model prediction results through multi-dimensional, complementary explainability analysis. Meanwhile, from the perspective of model prediction result visualization, we revealed the regions of facial images that the model focuses on for different bone mass states.

Furthermore, this study constructed a comprehensive quantitative analysis framework to evaluate the explainability of the Face2Bone model, primarily comprising SHAP quantitative attribution analysis and CRAFT concept-level analysis. In SHAP quantitative attribution analysis, we divided the face into five anatomical regions (forehead, periorbital, midface, mandibular, and nasolabial) based on MediaPipe’s 468 key points, calculated SHAP contribution values for each region across different bone mass states, and assessed intra-class consistency by evaluating the similarity of SHAP value distributions within the same class to verify the stability of model interpretations. Inter-class discriminative analysis was used to quantify the discriminative ability of SHAP value distributions between different bone mass states, thereby validating the discriminative power of model interpretations. Based on this foundation, we analyzed SHAP variation patterns from normal bone mass to osteoporosis across all regions through SHAP visualization to verify the biological plausibility of disease progression. In CRAFT concept analysis, we extracted facial concept activation explanation maps under different bone mass states to identify facial regions of model focus, and used Jensen-Shannon divergence65 to quantify the degree of attention distribution differences between different bone mass states.

SHAP

SHAP (Shapley Additive exPlanations)63 is a model interpretation method developed based on the Shapley value concept from game theory. This method assigns Shapley weights to each feature of the trained model and explains model decisions by calculating the marginal contribution of each feature to the model’s prediction results. For any feature \(i\), its SHAP value is defined as:

where \(N\) is the set of all features, \(|N|\) is the total number of features, \(S\) is a subset of features, excluding the feature \(i\), \(f\) is the model function, \(f(S)\) represents the model prediction using only the feature set \(S\), \(\frac{\left|S\right|!\left(\left|N\right|-\left|S\right|-1\right)!}{\left|N\right|!}\) is the combination weight that considers all possible feature combinations, and \(f\left(S\cup \left\{i\right\}\right)-f(S)\) is the marginal contribution.

We analyzed the facial regions that the model focused on for males and females across three different bone mass states. SHAP analysis results revealed significant differences in the facial image regions that the model attended to for patients with different bone mass states. In patients with normal bone mass (Fig. 12a), the model showed relatively balanced attention across facial regions, with all facial regions exhibiting negative SHAP contribution values (Table 6). Males and females showed minimal facial feature differences under normal bone mass conditions, indicating relatively stable facial feature distribution in normal bone density states, which was consistent with intra-class consistency analysis results (Table 7) and reflected the natural biological diversity of facial features in healthy populations. In patients with osteopenia (Fig. 12b), the model’s attention pattern underwent significant changes, with SHAP contribution values shifting from negative to positive across all regions. Notably, important changes occurred in the nasolabial region, which aligns with facial skeletal aging involving maxillary bone resorption during osteopenia19. The periorbital region showed the most significant changes and became the core region of model attention, consistent with orbital bones being the most vulnerable facial skeletal structures and being affected earliest in osteoporosis. Meanwhile, we found that female individuals exhibited relatively more pronounced and concentrated changes during the osteopenia stage, particularly in the periorbital and nasolabial regions, suggesting more significant facial changes in females during early disease stages. Notably, in osteoporosis patients (Fig. 12c), the model’s attention regions demonstrated unique changes compared to the previous two bone mass states, with highly concentrated attention in landmark regions of facial skeletal aging, particularly the jawline, periorbital, and nasolabial areas showing strong positive contributions, consistent with age-related facial skeletal aging biomechanical markers24,66: overall facial flattening, soft tissue ptosis, jawline “discontinuity” phenomenon, deepened nasolabial folds, and reduced visible eye area. The periorbital region achieved the highest positive contribution, becoming the most important feature for model identification of the osteoporosis category. At this stage, SHAP value variability across all facial regions significantly decreased (Table 7), indicating highly consistent typical facial change patterns in osteoporosis patients. CRAFT attention difference Jensen-Shannon analysis further validated this finding (Table 8), demonstrating that attention distribution differences gradually increased with disease progression.

Based on SHAP explainability analysis comparing changes across different bone mass states, we observed systematic progression patterns, confirming that all five facial regions exhibited evolution patterns from negative to positive values, with females showing more pronounced changes across different bone mass states compared to males, which relates to accelerated bone remodeling due to decreased estrogen levels after menopause67. To verify the reliability of this finding, we further analyzed intra-class consistency and inter-class discriminability, with two-sample t-tests revealing that intra-class similarity was significantly higher than inter-class similarity (\(P\)<0.001). Intra-class consistency and inter-class discriminability analysis results revealed clear increasing trends and good discriminative ability, reflecting the transition of individual features from natural diversity to pathological consistency during disease progression.

CRAFT: concept recursive activation factorization

CRAFT64 is a Concept Recursive Activation Factorization method that generates concept-based explanations to answer the questions "where is the model looking simultaneously" and "what is the model seeing." It employs a recursive strategy to achieve cross-layer detection and concept decomposition. It uses Sobol indices to calculate the importance of various concepts related to model predictions, then backpropagates concept scores to the pixel space to generate concept attribution heatmaps. The calculation of Sobol indices is as follows:

CRAFT obtains key visual concepts for different bone mass states through concept activation decomposition, concept importance estimation, and concept mapping attribution. We found that the key facial regions of interest for the model in predicting osteoporosis exhibit distinct category-specific patterns. As shown in Figs. 13, 14, and 15 we present the concept explanation maps, global concept importance, and the best image patches (facial regions that the model considers most representative of a particular concept) for facial images in different bone mass states.

From CRAFT concept maps of different bone mass states, we obtained the osteoporosis-related core visual concepts and their distributions extracted by the model, providing both macro and micro perspectives for understanding model decision-making. In normal bone mass facial images, concept distributions were relatively uniform, covering multiple facial regions and highlighting the structural contours of overall facial skeletal support, which formed a consistent explanatory framework with the uniform negative value distribution and higher individual variability shown in SHAP analysis (Table 7), indicating that the model focused on overall facial coordination rather than specific pathological regions in healthy states. As an intermediate state of disease progression, osteopenia showed concept distributions beginning to concentrate toward specific facial regions, with increased concept weights in the nasolabial region reflecting early maxillary bone resorption, consistent with the nasolabial region change patterns in SHAP analysis (Fig. 12b). Obvious concept changes around the orbital area corresponded to the maximum change magnitude in the periorbital region from SHAP analysis, indicating that facial orbital structures begin to change in this state. Meanwhile, midface concept weights were higher than other anatomical regions, possibly related to weakened soft tissue mechanical support due to age-related facial skeletal aging18. For osteoporosis facial images, the continuous state of concept maps was disrupted, with significantly expanded concepts in the orbital region and further enhanced weights in the nasolabial region, completely consistent with the highest positive contribution in the periorbital region and nasolabial region enhancement from SHAP analysis (Fig. 12c), which was also reflected in CRAFT’s best image patches. This aligns with results from existing studies showing degenerative changes in skeletal structures during facial aging measured through CT imaging68,69. Jensen-Shannon analysis results from CRAFT attention map difference analysis further quantified this finding (Table 8), confirming the concept reconstruction phenomenon during critical disease progression periods, indicating that the model underwent significant attention pattern redistribution during the transition from osteopenia to osteoporosis.

Through explainability analysis of the model using SHAP and CRAFT, our research results revealed differences in facial images across different bone mass states, supporting the hypothesis of associations between facial skeletal aging and systemic bone density status, and confirming that artificial intelligence can achieve early identification of osteoporosis through facial image analysis. SHAP analysis provided precise regional contribution quantification for the model, while CRAFT analysis revealed concept-level visual pattern evolution during disease progression. The consistency between these two methods validated the biological plausibility and clinical relevance of the Face2Bone model. This dual explainability framework not only opens new research directions for developing non-invasive osteoporosis screening technologies but also provides possibilities for further revealing cross-tissue regulatory mechanisms of facial soft tissue-bone metabolism and facial bone phase quantification.

Discussion

This study first proposed an innovative osteoporosis prediction model, Face2Bone, based on facial 2D images. SHAP and CRAFT XAI technologies revealed the model’s decision-making mechanism and the biological basis of facial skeletal aging. Our research results validated the feasibility of osteoporosis risk prediction based on facial images and provided necessary algorithmic evidence for applying this method to early risk screening of osteoporosis.

The model design of Face2Bone is the key driver for osteoporosis prediction using facial images. The FSA module, SSAM module, and KAN module significantly enhanced the model’s osteoporosis classification capability, enabling the model to effectively focus on and extract key facial regions related to osteoporosis. This allowed the model to outperform mainstream models such as VGG, ViT, and ResNet across all evaluation metrics, achieving 92.85% accuracy and 98.56% AUC. It demonstrated excellent performance in classifying facial images of osteoporosis patients, which is significant for identifying high-risk patients in early risk screening. The XAI interpretability analysis in this study provides possibilities for the clinical translation of deep learning models. SHAP and CRAFT methods transform the neural network black box into visual feature understanding.

In osteoporosis prevention and management, osteopenia, as an intermediate state of disease progression, requires precise identification for significant clinical and public health implications. As a transitional period of bone loss, implementing lifestyle interventions and necessary pharmacological treatments during this stage can significantly delay or reverse bone loss progression70, providing clinicians with an optimal therapeutic window. From a public health perspective, early identification of osteopenia populations is of great value for advancing prevention frontlines. Compared to existing systems utilizing CT imaging or clinical data for osteoporosis prediction71,72 and traditional DXA examinations, using facial images as an osteoporosis screening gateway, Face2Bone significantly reduces technical barriers while maintaining high accuracy, simplifies screening procedures, and enhances implementation feasibility. Input data is more accessible and economically convenient, particularly suitable for large-scale screening implementation in primary healthcare institutions and community health service centers, creating favorable conditions for early detection and timely intervention of osteopenia. Given this, we propose a standardized stratified screening decision pathway based on the Face2Bone model: for individuals predicted to have normal bone mass, provide bone health education and recommend regular follow-up to increase awareness and attention to osteoporosis while strengthening preventive consciousness; for individuals predicted to have osteopenia, recommend DXA examination for confirmation while initiating lifestyle interventions, including calcium and vitamin D supplementation, enhanced physical exercise, and consideration of preventive pharmacological treatment based on patients’ overall risk assessment and FRAX scores73 for high-risk individuals predicted to have osteoporosis, conduct DXA examination confirmation and specialist referral for systematic evaluation and targeted pharmacological treatment. Through establishing a risk-stratified screening strategy guided by the Face2Bone model, we aim to achieve optimal allocation of limited DXA resources and maximize individual health benefits, providing innovative technical support for early detection, timely intervention, and effective prevention of osteoporosis.

Study limitations

Although the Face2Bone model demonstrated excellent performance in osteoporosis prediction, this study has several limitations. First, this study employed a single-center design with all data derived from Ningbo No.2 Hospital, which may lead to selection bias. This bias stems from bidirectional selection processes in healthcare settings: on one hand, as a tertiary hospital, the medical institution tends to admit more complex or advanced cases; on the other hand, patients with more severe symptoms or greater concern about their condition often actively choose tertiary hospitals, while those with mild symptoms or asymptomatic early-stage patients tend to undergo routine examinations and preliminary screening at community hospitals or primary healthcare institutions. This differential healthcare-seeking behavior may result in systematic bias in disease severity distribution within our study sample. Additionally, patients who can access tertiary hospitals typically have better economic conditions, medical insurance coverage, and health awareness, and this socioeconomic selection bias further exacerbates sample non-randomness. The occupational structure dominated by manufacturing and service industries in Ningbo, along with corresponding occupational exposure patterns (sedentary work, heavy physical labor, etc.), may systematically affect the bone health status of the local population, making our research results difficult to generalize to regions with different occupational exposure characteristics. Single-center design also means that all data collection was conducted under identical environmental and technical conditions, which, while improving internal consistency, may mask the model’s true performance under different conditions.

Second, sample size limitations constitute another important constraining factor. This study included 1,040 patient images for model construction. Considering the complexity of osteoporosis clinical phenotypes and the extensive individual differences, the existing sample may not adequately cover all pathological change patterns and individual variations. Particularly for subtle changes or atypical presentations in early disease stages, the model’s recognition capability may be limited. The observed gender distribution imbalance (72.5% female), while somewhat reflecting the epidemiological characteristics of osteoporosis, also introduces significant performance bias. Detailed stratified analysis revealed that model accuracy in females was slightly higher than in males, and this difference may stem from more pronounced facial skeletal changes due to postmenopausal estrogen deficiency, making AI models more capable of identifying pathological features in females. However, this also suggests that the model’s clinical utility in male populations requires further validation and optimization.

Furthermore, the inherent limitations of cross-sectional study design restrict our in-depth understanding of disease dynamic processes. Single time-point data collection cannot establish temporal causal relationships between facial changes and bone density decline, nor can it validate the model’s predictive capability for disease progression trajectories. This limitation is particularly pronounced in research on slowly progressive chronic diseases like osteoporosis, because the temporal course of facial aging may have complex temporal differences with bone density changes, and these subtle temporal dynamic changes cannot be accurately captured in cross-sectional studies. Meanwhile, there exists a significant gap between standardized conditions at the technical implementation level and real-world application scenarios. To ensure data quality, this study employed highly controlled imaging conditions, including unified equipment, standard lighting, and standardized backgrounds, but these conditions are difficult to fully replicate in actual clinical screening environments. Equipment diversity, environmental lighting variations, patient compliance differences, and inconsistent operator skill levels in the real world could all significantly affect image quality and subsequently influence the model’s actual performance. Additionally, as a proof-of-concept study, we have not yet systematically validated key implementation elements such as operational feasibility, healthcare provider acceptance, and patient compliance of this technology in real clinical workflows.

To systematically address the above limitations, we plan to implement a phased validation strategy in future research. In the short term, we will expand validation scope through multi-center collaboration within the Ningbo Medical Consortium, a cooperation model that can reduce technical variability under relatively standardized clinical environments while incorporating diverse patient populations from different levels of healthcare institutions, thereby effectively alleviating single-center selection bias issues. Simultaneously, we will focus on strengthening male patient recruitment and borderline case collection to optimize sample composition and improve the model’s generalization capability. Medium-term goals include initiating prospective longitudinal cohort studies to establish temporal relationship models between facial changes and bone density evolution through 1–2 years of systematic follow-up. We will also develop robust image preprocessing algorithms and comprehensive quality assessment frameworks to improve the model’s adaptability to variable imaging conditions. In the long term, we plan to explore collaboration opportunities with broader healthcare networks to validate the model’s performance consistency across different geographic regions and healthcare environments, and develop clinical decision support tools to facilitate the practical application of this technology.

Conclusion

In this study, through CRAFT and SHAP interpretability analysis, we have demonstrated that the Face2Bone model can identify characteristic changes related to osteoporosis from 2D facial images and revealed the biological connections between these changes and the clinical manifestations of osteoporosis. The research results validate the feasibility of osteoporosis risk prediction based on facial images and provide algorithmic foundations for developing convenient, non-invasive osteoporosis screening tools. The interpretability of the Face2Bone model offers clinicians transparent and comprehensible decision support, which is expected to improve the early detection rate of osteoporosis and substantially contribute to reducing the global disease burden caused by osteoporosis.

Data availability

Data are available upon reasonable request due to privacy/ethical restrictions. Requests should be submitted to the corresponding author with a detailed research proposal.

Abbreviations

- OP:

-

Osteoporosis

- XAI:

-

Explainable artificial intelligence

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DXA:

-

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- VGG:

-

Visual geometry group (network)

- ViT:

-

Vision transformer

- ResNet:

-

Residual network

- LV:

-

Lumbar vertebrae

- NOF:

-

Neck of femur

- AS:

-

Ankylosing spondylitis

- PVP:

-

Percutaneous vertebroplasty

- LV:

-

Lumbar vertebrae

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- QUS:

-

Quantitative ultrasound

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CRAFT:

-

Concept recursive activation factorization

- FFN:

-

Feedforward network

- MLP:

-

Multilayer perceptron

- KAN:

-

Kolmogorov-Arnold networks

- SHAP:

-

Shapely additive explanantions

- MSA:

-

Multi-head self-attention

- FSA:

-

Frequency sparse attention

- SSAM:

-

Spatial supervised attention module

- ECE:

-

Expected calibration error

- BS:

-

Brier score

References

Xiao, P. L. et al. Global, regional prevalence, and risk factors of osteoporosis according to the world health organization diagnostic criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoporos. Int. 33, 2137–2153 (2022).

Khandelwal, S., Lane, N. E. & Osteoporosis Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 52, 259–275 (2023).

for the International Osteoporosis Foundation. Fragility fractures in europe: burden, management and opportunities. Arch. Osteoporos. 15, 59 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Prevalence of osteoporosis and associated factors among Chinese adults: a systematic review and modelling study. J. Glob Health. 15, 04009 (2025).

Chandran, M., Ebeling, P. R., Mitchell, P. J., Nguyen, T. V. & On behalf of the Executive Committee of the Asia Pacific Consortium on Osteoporosis (APCO). Harmonization of osteoporosis guidelines: paving the way for disrupting the status quo in osteoporosis management in the Asia Pacific. J. Bone Miner. Res. 37, 608–615 (2020).

Si, L., Winzenberg, T. M., Jiang, Q., Chen, M. & Palmer, A. J. Projection of osteoporosis-related fractures and costs in china: 2010–2050. Osteoporos. Int. 26, 1929–1937 (2015).

Link, T. M. Osteoporosis imaging: state of the Art and advanced imaging. Radiology 263, 3–17 (2012).

Salzmann, S. N. et al. Regional bone mineral density differences measured by quantitative computed tomography: does the standard clinically used L1-L2 average correlate with the entire lumbosacral spine? Spine J. 19, 695–702 (2019).

Dimai, H. P. Use of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for diagnosis and fracture risk assessment; WHO-criteria, T- and Z-score, and reference databases. Bone 104, 39–43 (2017).

Kanis, J. A. & Johnell, O. Requirements for DXA for the management of osteoporosis in Europe. Osteoporos. Int. 16, 229–238 (2005).

Mayes, A. et al. Ageing appearance in china: biophysical profile of facial skin and its relationship to perceived age. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 24, 341–348 (2010).

Wu, D. et al. Artificial intelligence facial recognition system for diagnosis of endocrine and metabolic syndromes based on a facial image database. Diabetes Metabolic Syndrome: Clin. Res. Reviews. 18, 103003 (2024).

Wang, J., He, C. & Long, Z. Establishing a machine learning model for predicting nutritional risk through facial feature recognition. Front. Nutr. 10, 1219193 (2023).

Lin, N. et al. Development and validation of a point-of-care nursing mobile tool to guide the diagnosis of malnutrition in hospitalized adult patients: a multicenter, prospective cohort study. MedComm 5, e526 (2024).

Lei, C. et al. AI-assisted facial analysis in healthcare: from disease detection to comprehensive management. Patterns 6, 101175 (2025).

Tomasiewicz, A., Polański, J. & Tański, W. Advancing the Understanding of malnutrition in the elderly population: current insights and future directions. Nutrients 16, 2502 (2024).

Kyrgidis, A., Tzellos, T. G., Toulis, K. & Antoniades, K. The facial skeleton in patients with osteoporosis: A field for disease signs and treatment complications. J. Osteoporos. 2011, 1–11 (2011).

Shaw, R. B. et al. Aging of the facial skeleton: aesthetic implications and rejuvenation strategies. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 127, 374–383 (2011).

Mendelson, B. & Wong, C. H. Changes in the facial skeleton with aging: implications and clinical applications in facial rejuvenation. Aesth Plast. Surg. 44, 1151–1158 (2020).

Shaw, R. B. et al. Facial bone density: effects of aging and impact on facial rejuvenation. Aesthetic Surg. J. 32, 937–942 (2012).

Swift, A., Liew, S., Weinkle, S., Garcia, J. K. & Silberberg, M. B. The facial aging process from the inside out. Aesthetic Surg. J. 41, 1107–1119 (2021).

Jonasson, G., Jonasson, L. & Kiliaridis, S. Changes in the radiographic characteristics of the mandibular alveolar process in dentate women with varying bone mineral density: A 5-year prospective study. Bone 38, 714–721 (2006).

Shaw, R. B. et al. Aging of the mandible and its aesthetic implications. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 125, 332–342 (2010).

Paskhover, B., Durand, D., Kamen, E. & Gordon, N. A. Patterns of change in facial skeletal aging. JAMA Facial Plast. Surg. 19, 413–417 (2017).

Castelo-Branco, C. et al. Relationship between skin collagen and bone changes during aging. Maturitas 18, 199–206 (1994).

Chucherd, O. et al. Association of sarcopenic obesity and osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: risk factors and protective effects of hormonal therapy and nutritional status. Arch. Osteoporos. 20, 83 (2025).

Yanmeng, Q. et al. Association between body composition components and bone mineral density in older adults. Sci. Rep. 15, 26190 (2025).

Song, J. et al. The relationship between body mass index and bone mineral density: A Mendelian randomization study. Calcif Tissue Int. 107, 440–445 (2020).

Tkachenko, Y. & Jedidi, K. A megastudy on the predictability of personal information from facial images: disentangling demographic and non-demographic signals. Sci. Rep. 13, 21073 (2023).

Qiang, J. et al. Review on Facial-Recognition-Based applications in disease diagnosis. Bioengineering 9, 273 (2022).

Gatineau, G. et al. Development and reporting of artificial intelligence in osteoporosis management. J. Bone Miner. Res. 39, 1553–1573 (2024).

Vania, M., Mureja, D. & Lee, D. Automatic spine segmentation from CT images using convolutional neural network via redundant generation of class labels. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 6, 224–232 (2019).

Rao, A. A radiologist’s perspective of medical annotations for AI programs: the entire journey from its planning to Execution, challenges faced. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging. s-0044-1800860 https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0044-1800860 (2024).

Chen, Y., Clayton, E. W., Novak, L. L., Anders, S. & Malin, B. Human-Centered design to address biases in artificial intelligence. J. Med. Internet Res. 25, e43251 (2023).

Kanis, J. A. & Kanis, J. A. Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis: synopsis of a WHO report. Osteoporos. Int. 4, 368–381 (1994).

Watts, N. B., Leslie, W. D., Foldes, A. J. & Miller, P. D. International Society for Clinical Densitometry Position Development Conference: Task Force on Normative Databases. Journal of Clinical Densitometry 16, 472–481 (2013). (2013).

Lugaresi, C. et al. MediaPipe: A Framework for Building Perception Pipelines. Preprint at (2019). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1906.08172

Buslaev, A., Parinov, A., Khvedchenya, E., Iglovikov, V. I. & Kalinin, A. A. Albumentations: fast and flexible image augmentations. Information 11, 125 (2020).

Schroff, F., Kalenichenko, D., Philbin, J. & FaceNet: A Unified Embedding for Face Recognition and Clustering. in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 815–823 (2015). 815–823 (2015). (2015). https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298682

Liu, Z. et al. KAN: Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks. Preprint at (2025). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.19756

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention Is All You Need. Preprint at (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1706.03762

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An Image is Worth 16x16 Words: Transformers for Image Recognition at Scale. Preprint at (2021). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2010.11929

Ba, J. L., Kiros, J. R. & Hinton, G. E. Layer Normalization. Preprint at (2016). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1607.06450

Szegedy, C., Ioffe, S., Vanhoucke, V. & Alemi, A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning. AAAI 31, (2017).

Howard, A. G. et al. MobileNets: Efficient Convolutional Neural Networks for Mobile Vision Applications. Preprint at (2017). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1704.04861

Pan, Z., Cai, J. & Zhuang, B. Fast Vision Transformers with HiLo Attention. Preprint at (2023). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.13213

Park, N. & Kim, S. How Do Vision Transformers Work? Preprint at (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2202.06709

Liu, Z. et al. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer using Shifted Windows. Preprint at (2021). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2103.14030

Mcculloch, W. S. & Pitts, W. A LOGICAL CALCULUS OF THE IDEAS IMMANENT IN NERVOUS ACTIVITY.

Rosenblatt, F. The perceptron: A probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain. Psychol. Rev. 65, 386–408 (1958).

Yu, R., Yu, W. & Wang, X. KAN or MLP: A Fairer Comparison. Preprint at (2024). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2407.16674

Haibo, H. & Garcia, E. A. Learning from imbalanced data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 21, 1263–1284 (2009).

Vakili, M., Ghamsari, M. & Rezaei, M. Performance Analysis and Comparison of Machine and Deep Learning Algorithms for IoT Data Classification.

Guo, C., Pleiss, G., Sun, Y. & Weinberger, K. Q. On Calibration of Modern Neural Networks.

Cacciatore, A. et al. A preliminary study on continual learning in computer vision using Kolmogorov-Arnold networks. Preprint at (2024). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2409.13550