Abstract

The construction industry in Pakistan faces significant challenges, including high material costs, environmental degradation, and inefficient waste management. This study addresses these issues by developing eco-friendly bricks and tuff tiles incorporating various agricultural byproducts and industrial wastes in different proportions. A comprehensive experimental analysis, including density tests, compressive strength measurements, water absorption evaluation, and microstructural analysis using X-ray Diffraction (XRD), was conducted to assess the material performance of the developed eco-friendly tuff tiles/bricks. The XRD finding affirms the crystalline phase of developed samples, which is required to enhance strength, stability, and long-term performance. The other results show that incorporating these waste materials (with rice husk) reduces water absorption by up to 1% in bricks and 9% in tuff tiles, while the compressive strength reaches up to 9 MPa for bricks and 32.3 MPa for tuff tiles (with sugarcane bagasse ash), comparable to the recommended compressive strength with few exceptions. The results indicate a density range of about 1.5 and 2.0 g/cm³. Cost analysis reveals that production costs can be lowered by 14% for bricks and 4% for tuff tiles compared to conventional products. This research offers a novel, practical framework for sustainable construction practices in Pakistan and the Globe by effectively utilizing underexploited agricultural and industrial byproducts, thus providing economically viable and environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional building materials. It is also worth mentioning that this work directly aligns with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure), Goal 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), and Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cement is one of the most widely used construction materials, essential for buildings, highways, and infrastructure. However, its production is highly energy-intensive and a major source of greenhouse gas emissions1. With growing environmental concerns and the demand for economical, durable building materials, attention has turned to supplementary cementitious materials as partial replacements for cement. In Pakistan, bricks and tuff tiles are the most used construction products; however, the country simultaneously generates millions of tons of industrial and agricultural waste each year, much of which is disposed of indiscriminately, thereby contributing to significant environmental hazards. In contrast, developed nations increasingly incorporate industrial by-products such as sludge waste, rice husk ash, and coal ash into construction materials2. This study explores the use of locally available industrial and agricultural wastes to reduce cement consumption and enhance sustainability in building units.

Research shows that adding supplementary cementitious materials to concrete can improve desired properties while lowering production costs. For instance, clay-based geopolymer bricks are promising for the future, though improving clay reactivity without increasing costs remains a challenge3. The use of geopolymer and polypropylene can result in lightweight concrete and enhance fire resistance4,5,6. Incorporating agricultural and industrial waste into clay bricks has been shown to reduce firing energy requirements, improve mechanical strength, and decrease environmental impacts, producing eco-friendly alternatives to conventional clay bricks. A variety of wastes, including cotton, polyester, PET, glass fiber, and granulated blast furnace slag, have been used to manufacture cementitious composites, offering both environmental and economic benefits7,8. Fibers have been used in reinforced concrete to enhance its mechanical performance and to highlight its potential for durable and eco-friendly construction9. The use of wastewater can promote circular economic practices by reducing freshwater demand and mitigating environmental burdens10.

Specific industrial by-products have been studied extensively. Waste marble sludge can produce lightweight bricks11, while marble dust has been found to enhance the mechanical properties of clay bricks12. Volcanic tuff waste, when used as a raw material in ceramic tile manufacturing, improved green strength (9.83 MPa), fired strength (26.77 MPa), and reduced water absorption13. Recycled crushed clay bricks have been used to produce solid cement bricks with higher compressive strength14. Papercrete bricks, produced from paper pulp, lime, and fly ash, are lightweight, cost-effective, and suitable for non-load bearing walls15.

Other industrial wastes have been explored for construction applications. Stone crusher dust and silica dust can replace a significant portion of natural aggregates in concrete while addressing air pollution concerns16. For instance, the addition of sawdust to clay bricks has been shown to improve thermal insulation and reduce the depletion of natural resources17. Sewage sludge has been incorporated into red ceramic bricks via extrusion, with moisture adjustments improving product quality18. Moreover, incorporating waste marble sludge into burnt clay bricks has produced lightweight bricks with enhanced mechanical performance19. Iron ore tailings (IOT), a by-product of beneficiation processes, can replace virgin materials, conserving natural resources20. The utilization of industrial PVC waste powder in self-compacting concrete offers a sustainable alternative to conventional materials with improved workability and mechanical strength21. Recent comprehensive reviews also explore the potential of various industrial waste byproducts in the production of both fired and unfired bricks, indicating promising prospects for eco-friendly tuff tile and brick manufacturing22.

Powdered wastes such as ceramic waste powder (CWP), eggshell powder (ESP), and granite powder (GP) have also shown potential. CWP used in brick production improved mechanical strength and resistance to efflorescence, freeze–thaw cycles, and sulfate attack23 and ceramic aggregates have been used in concrete blocks and have proven beneficial24. GP and ESP have enhanced the physical and mechanical properties of fired clay bricks25. Other studies suggest that incorporating organic and inorganic industrial waste into clay bricks can improve cost-effectiveness, thermal insulation, and environmental performance26. Agricultural residues such as wheat straw, sunflower seed cake, and olive stone flour have been tested, with sunflower seed cake showing optimal mechanical and thermal performance27.

Rice husk and rice husk ash (RHA) are particularly noteworthy. Rice husk can improve thermal insulation, while RHA offers high pozzolanic activity and reactivity when used in concrete28,29. Research indicates that RHA can alter concrete workability depending on replacement levels30, reduce dead load due to its low specific gravity31, and address early-age shrinkage32,33. In brick production, RHA and sugarcane bagasse ash (SBA) have met standards despite reduced compressive strength. The inclusion of rice straw in bricks enhances thermal and acoustic performance34. Concrete blocks made with coconut husks and pistachio shell powder as sand replacements have demonstrated durability and good strength35.

Recycled materials have been integrated into paving products as well. Plastic paver blocks manufactured from waste plastic bags offer sustainable, strength-comparable alternatives to concrete pavers36. Recycled glass aggregates in concrete improve mechanical strength over time and present a cost-effective, environmentally friendly alternative37. Crushed glass as a coarse aggregate in paving blocks improves strength and reduces water absorption, though crumb rubber additions can compromise mechanical properties38.

Agro-industrial wastes such as oil palm shell, palm oil fuel ash, and quarry dust have been used to produce bricks with enhanced mechanical properties39. Even unconventional by-products, such as olive oil processing wastewater, have been trialed as partial replacements for mixing water in ceramic brick production, with slight performance improvements40.

Overall, these studies reveal a wide range of industrial and agricultural wastes, ranging from textile fibers to agricultural residues and mineral powders that can serve as partial replacements for cement or natural aggregates. Such materials can enhance mechanical properties, reduce production costs, improve thermal insulation, and significantly lower the environmental footprint of construction.

Although the benefits of utilizing waste-derived materials in construction have been extensively demonstrated at the international level, Pakistan’s construction sector has yet to fully capitalize on this potential. The indiscriminate disposal of industrial and agricultural residues continues to pose significant environmental, economic, and social challenges. Furthermore, existing research within the country has not systematically explored the incorporation of multiple locally available by-products into conventional brick and tile manufacturing, particularly with respect to achieving an optimal balance between mechanical performance, cost efficiency, and sustainability.

This study introduces a novel approach by systematically incorporating a diverse range of industrial and agricultural byproducts, such as marble powder, plastic waste, glass powder, sugarcane bagasse ash, and rice husk ash into the preparation of bricks and tuff tiles specifically tailored for Pakistan’s developing construction industry. Tuff tiles are interlocking concrete tiles widely used across Pakistan for outdoor flooring. Fabricated with a cement-sand-aggregate mix, their interlocking structure provides long-term stability, while their durability makes them fit for high-traffic and weather-exposed zones. Unlike prior research that often focuses on single byproducts or limited material types, this work provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of multiple byproducts, evaluating their effects on density, water absorption, compressive strength, and cost-efficiency. Moreover, the research uniquely emphasizes both environmental and economic benefits in the Pakistani context, addressing the pressing need for sustainable alternatives to traditional concrete and brick materials.

This research aims to fill that gap by evaluating locally generated industrial and agricultural by-products such as marble, plastic, rice husk, wheat, saw sawdust as partial cement replacements in building units. By leveraging materials readily available in Pakistan, the study seeks to promote sustainable construction practices, reduce environmental hazards associated with waste disposal, and contribute to the development of cost-effective, durable, and eco-friendly building materials.

Materials & methods used

This research focuses on the development of sustainable construction materials, specifically bricks and tuff tiles, through the strategic incorporation of industrial byproducts. The initial phase of the work is dedicated to the careful selection of these byproducts, which necessitates a thorough, on-the-ground understanding of local industrial and manufacturing contexts. To achieve this, site visits were conducted at various brick kilns and manufacturing facilities across Pakistan. These visits were instrumental for collecting material samples and, more importantly, for engaging directly with production teams to gain first-hand insight into the conventional fabrication processes.

The primary objectives of these visits were threefold: to carefully select appropriate byproducts, collect material samples directly from the source, and, most importantly, to engage with local production teams to gain a grounded, practical understanding of the conventional fabrication processes. Through direct observation and discussion, the entire production cycle for both materials was meticulously documented. The process for brick manufacturing begins with the preparation of a clay-based mixture, which is molded and then air-dried for a period highly susceptible to weather conditions, typically lasting between two to seven days, before being fired in kilns. In contrast, tuff tile production utilizes a cementitious mixture that is poured into molds and left to set. Despite a significant increase in the use of tuff tiles across Pakistan in recent years, a standardized production procedure for their manufacture remains notably absent. Tuff tiles, whose main components are cement, sand, aggregate and pigments, are currently employed in applications such as parking areas and residential flooring due to their smooth, versatile, and attractive appearance. Unlike brick manufacturing, which requires a large-scale kiln for firing, tuff tile production does not need a large production unit, as the binding properties are instead imparted through cement hydration between the sand particles. Tuff tiles/paver blocks have diversified in existence due to the availability of multiple shapes and sizes in the market. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that they are economical and require little or no maintenance if properly laid out in comparison to bricks. Ultimately, these site visits provided essential real-world insights. They helped us move beyond theory to truly understand how these materials are made, the challenges workers face, and the environmental impact of the industries. This on-the-ground knowledge was crucial for shaping the next stage of our experimental work.

During industrial visits, the byproducts have been selected according to their potential for replacement with cement. The byproducts for this research are chosen wisely according to the industry and the agriculture sector of Pakistan. It is also considered during selection that selected byproducts must be abundant and easily available across Pakistan. The list of byproducts shortlisted for this research is listed below (Fig. 1):

Organic byproducts

-

Wheat (Wheat is Pakistan’s staple crop, cultivated mainly in Punjab and Sindh, and produces significant agricultural residues such as husk and bran during milling.)

-

Rice (Rice, a major export commodity grown in Punjab and Sindh, generates byproducts like husk and straw during harvesting and processing).

-

Sugarcane (Sugarcane is widely grown in Punjab, Sindh, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, with byproducts including bagasse and molasses from milling).

-

Sawdust (Sawdust is a wood-processing residue commonly generated by Pakistan’s furniture and carpentry industries, especially in urban and industrial hubs).

Inorganic byproducts

-

Plastic (Plastic waste in Pakistan mainly originates from packaging, consumer goods, and industrial processes, forming a significant portion of municipal solid waste).

-

Marble powder (Marble powder is a fine waste produced by cutting and polishing marble in processing units located in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab, and Balochistan).

-

Glass powder (Glass powder is obtained by crushing and grinding discarded glass from domestic, commercial, and industrial sources across Pakistan).

At the next stage of research, the proposed bricks and tuff tile samples have been prepared using the above-mentioned organic and inorganic byproducts in various proportions. The chosen byproduct material ratios in sample preparation for both tuff tiles and bricks are provided in detail in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 summarizes the tuff tile samples’ composition with replacement of cement with different organic/inorganic byproducts, whereas Table 2 describes the same for brick samples. It is evident from both tables that 31 testing samples have been fabricated for tuff tiles and 21 samples for bricks by incorporating various organic/inorganic byproducts in different proportions. For every byproduct under investigation, cement was partially replaced at three distinct incremental rates: 5%, 10%, and 15% by mass. This experimental matrix was designed to methodically assess the influence of increasing byproduct incorporation on the key physical and mechanical properties of the resulting composite material. In addition to that, different morphologies (solid, ash, or powder) of byproducts have been used as well during the sample preparation to understand the possible impact of byproduct state (ash or solid) on the sample performance. Organic byproducts are used in both solid and ash form in order to optimize the ratios and to find an optimum solution. In short, this research aims to do two important things: (i) first, it will measure how using different amounts of a byproduct—5%, 10%, or 15%—affects the strength and quality of the bricks and tuff tiles (ii) second, it will also explore how the physical form of the byproduct itself, whether it is a solid material or a fine ash, influences the final product.

The tuff tile samples are prepared by combining the cement, byproduct, and aggregates in the specified proportions by following the mentioned steps. The final developed tuff tile samples are shown as well in Fig. 2, and the detailed steps for the preparation of tuff tiles are provided below:

-

i.

Preparation of Mix: The required quantities of aggregate, cement, water and byproduct were weighed according to the specified mix proportions. The aggregate and byproduct were first thoroughly mixed, after which cement was added, and the mixture was further blended in a mixing container.

-

ii.

Addition of Water: Gradually add water while continuously mixing until a homogeneous mixture is obtained.

-

iii.

Casting: Pour the prepared mixture into the tuff tiles molds, ensuring uniform distribution and proper compaction.

-

iv.

Demolding: Once the sample is molded into the desired shape, remove it from the mold after 2 days.

-

v.

Curing: Specimens were stored under water until the scheduled testing date.

The mix design adopted for the control specimens in tuff tile manufacturing follows a 1:1.5:2 proportion of cement, sand, and coarse aggregate. In this case, the total binder-to-aggregate ratio is maintained at 1:2.25, ensuring that cement content is sufficiently high to provide adequate paste for binding. The chosen sand-to-coarse aggregate split (approximately 43% fine aggregate and 57% coarse aggregate) enables an effective balance between strength and workability. Excessive fine material can lead to shrinkage and reduced durability, whereas excessive coarse material may result in harsh mixes; therefore, this balanced ratio enhances both structural integrity and surface finish, which are critical for tuff tiles.

It is worth mentioning that the adoption of a water-to-binder ratio (w/b) has been set at 0.36, which is an important parameter in the case of tuff tiles. Moreover, a reduced w/b ratio ensures lower porosity and higher density of the matrix, minimizing permeability and improving long-term strength and durability of the tiles. Previous studies41 on precast concrete products and paving blocks have shown that w/b ratios of 0.36 are effective for achieving compressive strengths exceeding 30 MPa (≈ 4350 psi), which aligns well with the target performance for control specimens in this study.

Table 2 provides a summary of brick samples prepared with different organic and inorganic byproducts (added at different proportions by replacement of clay). Bricks are commonly used in the construction of walls, both load-bearing and non-load bearing, as well as in various architectural features such as arches, columns, and facades. They offer good thermal mass properties, helping to regulate indoor temperature, and are fire-resistant, making them a preferred choice for many building applications. Traditional brickmaking processes have evolved, incorporating modern technology and techniques to enhance efficiency and quality. Additionally, sustainable practices, such as using recycled materials or optimizing firing processes to reduce environmental impact, have gained attention in brick production in recent years. The final developed brick samples after the addition of byproducts for this proposed research are shown in Fig. 2. The detailed steps involved for the preparation of brick samples have been summarized below:

-

i.

Preparation of Mix: The required quantities of clay and byproduct were weighed according to the specified mix proportions. The clay and byproduct were thoroughly mixed using a shovel.

-

ii.

Addition of Water: Gradually add water while continuously mixing until a homogeneous mixture is obtained.

-

iii.

Casting: Pour the prepared mixture into the brick molds, ensuring uniform distribution and proper compaction.

-

iv.

Demolding: Once the sample is molded into the desired shape, remove it from the mold and let it dry in the air.

-

v.

Brick Kiln: once the bricks are dried, they are stacked in the brick kiln according to the burning requirements (approximately for 2 days at 1000 °C).

Figure 2 illustrates the final developed samples of tuff tiles and bricks prepared using various organic and inorganic byproducts. Each set shows different proportions (5%, 10%, 15%) of cement or clay replaced with agricultural and industrial waste materials, such as rice husk, sugarcane bagasse, marble powder, and plastics. Notably, three replicate samples were prepared for each byproduct combination (e.g., MP-5%, SBA-10%) to ensure repeatability. Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for all tested parameters and described in detail in the “results and discussions” section.

Results & discussions

Following the preparation of the samples, the subsequent stage involved their evaluation through standardized testing procedures. Accordingly, experimental analyses were conducted to assess density, particle size distribution (sieve analysis), compressive strength, water absorption, and crystalline structure using X-ray diffraction (XRD). The results section also includes a discussion on cost comparison, statistical analysis, and novelty of the proposed work. The detailed results of these tests are presented below:

Sieve analysis

First of all, sieve analysis is performed to understand the fineness percentage. The results of sieve analysis are provided in Fig. 3, and it can be observed that fines (less than 0.0.75 mm size) are about 4 to 8%. Such a fineness percentage range indicates that only a small fraction of fine particles passes through the sieve # 200. Fineness values are crucial in various industries (e.g., construction, mining, or pharmaceuticals) to ensure that the material meets specific application requirements. In the context of tuff tile manufacturing, this relatively low proportion of fines suggests favorable particle gradation for mechanical strength and durability. Moreover, controlling the fineness of raw materials plays a vital role in achieving consistency in production and optimizing the overall quality of the final product.

The results presented in Fig. 3 represent the percentage of fine particles (below 0.075 mm) present in the raw materials used for sample preparation. The 4–8% fineness range confirms the coarseness suitable for structural applications in tuff tile fabrication.

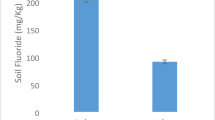

Density

After sieve analysis, the prepared samples are further characterized using density analysis, which is a crucial parameter in evaluating the quality of tuff tiles and bricks. The density measurements of both tuff tiles and brick samples are presented in Figs. 4 and 5. This test was conducted to examine the influence of incorporating industrial by-products (different proportions) on the density of the prepared specimens (tuff tiles/bricks), thereby providing insights into the modifications induced in the overall material structure.

Figure 4 presents the comparative analysis of the density of all tuff tile samples prepared with varying types and proportions of waste materials. The results indicate that the inclusion of certain byproducts, notably sugarcane bagasse solid (SBS), contributes to a lower density without compromising structural consistency. In addition to that, results further depict that the addition of byproducts is not making the samples heavier, and the density of tuff tile samples is still varying in the range of 1.5–2 g.cm−3.

It is worth mentioning that such a decrease in density can be useful for applications where construction demands the use of lightweight materials. Moreover, the decrease in density is beneficial as well in terms of easy handling, reducing transportation costs, and improving thermal insulation properties.

Analogously, the prepared brick samples showed the same density variation trend, and the density range remained between 1.5 and 2.0 g/cm³ on replacement of clay with byproducts. The figure elaborates that the minimum density observed was in the case of the SBA (5) sample, which stands around 1.35 g/cm³. Overall, it may be observed that the addition of byproducts helps reduce the density and make tuff tile/bricks lighter.

X-ray diffraction (XRD)

XRD test provides valuable insights into the crystalline nature and phase composition details of the bricks/tuff tiles, particularly when mixed with different byproducts during the formation process. XRD is a vital analytical tool that assists in evaluating the quality of cement, as the diffraction peaks provide insights into the presence of crystalline phases and impurities within the material. In addition, XRD is highly effective in identifying and quantifying the amorphous content, thereby offering a comprehensive understanding of the cement’s structural composition.

The XRD results of the samples prepared with different additives are provided below in Figs. 6 and 7. Figure 6 depicts the XRD peaks pattern from inorganic additives such as MP, GP, and Plastic; while Fig. 7 presents the XRD peaks obtained from organic byproducts. This is evident from Fig. 6a that the XRD pattern of the MP sample exhibits prominent peaks corresponding to calcite (CaCO₃) from marble, with key peaks observed near 29.4°, 39.4°, and 47.5° (2θ). Peaks associated with cement hydration products, such as portlandite (Ca (OH)₂), are also visible around 18° and 34°, indicating the interaction between marble and cement. Figure 6b shows the XRD peaks for the GP sample with possible contributions from amorphous silica in the glass powder. No sharp peaks from the glass indicate its amorphous nature. In the case of plastic, the XRD pattern of the sample shows strong cementitious peaks, including portlandite and possibly calcium silicate hydrates, as depicted in Fig. 6c. The absence of distinct crystalline peaks from plastic indicates its amorphous nature and suggests that it does not contribute crystalline phases.

Figure 7 summarizes the XRD peaks with organic additives in bricks/tuff tile samples. For instance, in Fig. 7a, the SBA sample’s XRD peaks reveal the presence of crystalline phases typical of cement, such as portlandite and silicates, with no significant peaks attributable to sugarcane, suggesting its likely amorphous contribution to the composite. The XRD pattern for the SDS sample shows characteristic peaks of cementitious phases, including portlandite (Ca(OH)₂) and calcium silicate hydrates, as depicted in Fig. 7b. Sawdust likely contributes amorphously, as no distinct crystalline peaks associated with it are observed.

The WSS sample in Fig. 7c exhibits dominant peaks corresponding to cement hydration products like portlandite and minor contributions from other crystalline phases. Wheat residues are likely to contribute as amorphous material, as no distinct peaks associated with organic matter are evident. The RHS sample exhibits strong peaks for cementitious compounds. The rice husk solid likely contributes as an amorphous phase, as there are no evident peaks from organic material. Cement hydration products dominate the pattern, as evident from Fig. 7d. However, the RHA sample displays distinct crystalline peaks of cementitious compounds alongside sharp peaks possibly corresponding to crystalline silica (quartz), which is commonly present in rice husk ash (as shown in Fig. 7e). This suggests partial crystallinity in the ash.

These diffractograms in Figs. 6 and 7 display the crystalline structure of bricks/tuff tiles prepared with various waste materials. Prominent peaks associated with portlandite, calcium silicate hydrates, and mineral traces like quartz and calcite help assess the interaction and integration of the byproducts into the cementitious matrix.

(a–c): X-ray Diffraction (XRD) patterns of bricks and tuff tiles prepared with inorganic byproduct additives (GP, MP, and Plastic), highlighting the presence of crystalline phases such as portlandite (P), calcite (C), and quartz (Q), as well as indications of amorphous contributions from certain materials.

(a–e): X-ray Diffraction (XRD) patterns of bricks and tuff tiles prepared with organic (SBA, SDS, WSS, RHS, and RHA) agricultural and industrial byproduct additives, highlighting the presence of crystalline phases such as portlandite (P), calcite (C), and quartz (Q), as well as indications of amorphous contributions from certain materials.

The XRD analysis not only characterizes the crystalline and amorphous phases in the byproduct-based mixtures but also clarifies their implications for mechanical strength and chemical durability. Crystalline phases such as portlandite, calcite, and quartz contribute to a robust microstructural framework, enhancing load-bearing capacity and resistance to degradation. Across all eight XRD patterns, calcite (CaCO₃) is the dominant crystalline phase, evidenced by the intense peak at ~ 29.4° 2θ along with secondary peaks at ~ 39–48° and ~ 57°. Quartz (α-SiO₂) is consistently observed in several samples—particularly MP, SBA, SDS, and GP—through its strong reflection at ~ 26.6° and related minor peaks. Portlandite (Ca(OH)₂) is also present in multiple samples, with characteristic reflections near ~ 34° and ~ 47°, most prominent in MP, SBA, SDS, and GP. RHS and RHA patterns are distinguished by extremely strong calcite peaks and minimal quartz signatures, indicating high carbonate content and reduced crystalline silica. Reactive amorphous phases, particularly silica-rich materials, improve densification through secondary hydration reactions, while inert amorphous phases may act as fillers with limited structural contribution. These findings, supported by microstructural evidence and aligned with previous literature (e.g., Mechanical and durability performance of geopolymer concrete), explain the observed improvements in strength and durability of the developed bricks and tuff tiles.

Water absorption test

The next test performed on the samples is the water absorption test. This is a proven method to calculate the durability of construction materials based on the percentage of water absorbed. This quantifies the material’s porosity and water absorption capacity, critical for evaluating the durability and suitability of a material for construction purposes. The high levels of water absorption make the material weaker and lead to cracks and lesser life span. This test is also useful in evaluating the response of tuff tiles/bricks in water, rain, or other humid environmental conditions. Thus, it may be concluded that it is optimum to choose such materials in construction that have lower levels of water absorption.

The graphical representation of water absorption tests for both bricks and tuff tiles with different byproduct additives is depicted in Figs. 8 and 9, respectively. Figure 8 indicates that the water absorption level is lower with the RHS (15) among the tuff tile samples, standing at 1%. Comparable findings have been reported in previous studies, where the incorporation of rice husk has consistently been associated with reduced water absorption in construction materials42.

Figure 9 presents the water absorption capacity of brick samples developed with different clay replacement materials. Among these, rice husk ash (RHA) at a 10% replacement level exhibited the most favorable performance, with a water absorption rate of approximately 10%.

The obtained result reinforces that rice husk in both solid and ash form plays a crucial role in making the water absorption levels optimum if added as a byproduct in construction material. The results further confirm that rice husk serves as a suitable additive for construction materials, as its incorporation leads to comparatively lower water absorption levels. This reduction in water uptake not only enhances the material’s resistance to moisture ingress but also contributes to improved durability and long-term performance in construction applications. This test is critical for ensuring bricks/tuff tiles are reliable and long-lasting in construction projects.

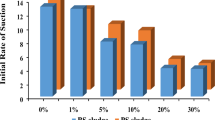

Compressive strength test

At the next stage, the compressive strength tests have been performed on fabricated samples to determine the ability of a material to withstand loads that tend to compress or crush it. It is a critical test for evaluating the material’s suitability for construction and structural applications in compressive environments.

The uniaxial compression tests were performed on some brick (ASTM C67)43 and tuff tile (ASTM C936)44 samples. The graphical representation of the compressive strength test is displayed in Figs. 10 and 11. Figure 10 illustrates the compressive strength of tuff tile samples incorporating varying proportions of by-product substitutions, with values ranging from 6 MPa to 32 MPa. Notably, the sample containing 5% sugarcane bagasse ash (SBA 5) achieved the highest strength of approximately 32 MPa, underscoring its potential as an optimal additive.

In the case of bricks, the strength levels vary in the range of 1 MPa to 11 MPa, with SBA (5) showing the highest levels of strength, as shown in Fig. 11. Among the tested additives, sugarcane bagasse ash (SBA) and marble powder (MP) led to the highest strength values, reinforcing their mechanical advantage45. The strength of bricks and tuff tiles does not depend only on the materials used but also on several other factors. Things like the burning time, type of fuel, soil composition, and even the skill of the workers play an important role. Since clay and sand are the main ingredients of bricks, their quality directly affects the final product. During firing, clay develops binding properties that hold the particles together, but this process also releases harmful gases into the environment. Even after going through these steps, traditional bricks often lack durability.

Cost comparison

Several factors may affect the price of bricks and Tuff tiles in Pakistan, in addition to the cost of materials. These include the quality of materials used, the efficiency of the burning/manufacturing process, and the cost of raw materials. The following Tables 3 and 4 present a cost comparison of proposed bricks and tuff tiles (10% cement/clay replaced with byproducts) with standard commercially available bricks and tuff tiles. For instance, Table 3 provides a cost comparison between conventional bricks produced in a brick kiln and those incorporating optimal by-products at a 10% replacement level. The approximate manufacturing cost of one brick (compressive strength 10.3 MPa = 1500 psi) having a volume = 1,767,456 mm3 (L x W x H = 228 mm x 102 × 76 mm) is 14.5 PKR. In contrast, the cost can be reduced by as low as 14% when clay is replaced with 10% MP byproduct in bricks.

The following Table 4 includes a comparison of the cost of one tuff tile, along with the optimum byproducts with a replacement level of 10% (i.e., 10% byproduct and 90% cement). The estimated manufacturing cost of a single tuff tile, with a compressive strength of 30 MPa (≈ 4300 psi) and a volume of 1,200,000 mm³ (200 mm × 100 mm × 60 mm), is calculated to be 24.22 PKR. This cost, however, can be reduced by up to 4% when 10% of the cement content is replaced with sugarcane bagasse ash (SBA), thereby demonstrating the economic potential of by-product incorporation in construction materials.

Statistical validation

Finally, the statistical analysis is performed in order to further validate the results and observations as obtained during experimentation. The statistical analysis via one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) confirmed that differences in compressive strength and water absorption across byproduct types and replacement levels were significant (p* < 0.05), except for minor exceptions (e.g., GP-5% tiles). Standard deviations for all replicates were < 10% of mean values, indicating high repeatability.

Societal contributions

To highlight the contributions, Table 5 provides a structured comparison of novelty between selected previous studies and the present work, explaining how this research advances existing knowledge and introduces new dimensions in the sustainable utilization of industrial and agricultural by-products for construction materials.

This research study highlights several key contributions, which are provided below.

-

i.

It presents a dual emphasis on both bricks and tuff tiles; an approach seldom explored together in existing research.

-

ii.

It offers a comprehensive evaluation of diverse industrial byproducts—including rice husk ash (RHA), sugarcane bagasse ash (SBA), marble powder (MP), waste plastic, glass powder, and sawdust—as potential partial replacements in mix formulations.

-

iii.

It successfully establishes optimum replacement levels in the range of 5–10%, where mechanical and durability properties are most favorable.

-

iv.

For tuff tiles, the mix incorporating SBA achieved a compressive strength of 32 MPa, demonstrating structural viability.

-

v.

The investigation also reports minimal water absorption values, with rice husk ash (RHS) producing results as low as 1% in tuff tile specimens, indicating improved durability.

-

vi.

Finally, the study confirms cost-effectiveness, with bricks produced at approximately 14% lower cost and tuff tiles at nearly 4% lower cost compared to conventional market alternatives.

-

vii.

This research aligns with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), promotes environmental sustainability, and provides a viable solution for eco-friendly construction materials.

Conclusion

The present study offers novel insights by demonstrating the feasibility of using a variety of industrial and agricultural byproducts as partial replacements in bricks and tuff tiles, achieving comparable or improved physical and mechanical properties compared to conventional materials. The comprehensive evaluation of additives like sugarcane bagasse ash, marble powder, and rice husk ash in both bricks and tuff tiles, combined with detailed density, water absorption, and compressive strength analyses, distinguishes this research from previous studies that often limited scope or focused on a single byproduct. Importantly, the cost comparison reveals significant economic advantages, making these sustainable materials viable alternatives for the Pakistani construction sector.

This study investigated the incorporation of industrial and agricultural by-products into the production of bricks and tuff tiles, with their performance subsequently evaluated through a series of standardized tests, including density analysis, sieve analysis, X-ray diffraction (XRD), water absorption, compressive strength, and statistical analysis. The test results showed that adding by-products led to a slight change in the density, resulting in a minor reduction. The sieve analysis described that the sand used had a fineness between 4 and 8%, which is within the acceptable ranges. The XRD analysis of samples proved the crystalline nature of brick/tuff tiles when mixed with different byproducts. XRD is an important test to evaluate the quality of cement based on the peaks received from impurities in the cement. Moreover, the results obtained from the water absorption test indicated that the addition of byproducts was able to reduce the water absorption levels up to 1% and 9% respectively, in both tuff tiles and bricks.

In addition, compressive strength levels as high as 32 MPa were achieved in tuff tiles using sugarcane bagasse ash (SBA) as a byproduct, while bricks exhibited compressive strengths of about ~ 11 MPa with the same byproduct. The compressive strength of tuff tiles with 5–10% cement replacement by marble powder, plastic, glass powder, or sugarcane bagasse ash can match the strength of the control specimen. On the other hand, the compressive strength of brick with 5–10% clay replacement by marble powder or sugarcane bagasse ash can match the strength of the control specimen. Finally, a cost comparison for the proposed bricks and tuff tiles reinforces the importance of this research in terms of the economy. It is observed that the costs of developed samples are comparably less than commercially available bricks/tuff tiles by 14% (bricks) and 4% (tuff tiles).

Overall, this work provided valuable insights that will undoubtedly contribute to our broader understanding of construction materials and their role in sustainable and efficient building practices. The outcomes of this study support global sustainability efforts by addressing key United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly in promoting sustainable construction practices, reducing waste, and advancing resilient infrastructure. While they present a multitude of advantages, it is equally important to acknowledge and assess their limitations in relation to their appropriateness for specific construction endeavors. Therefore, the discussion related to limitations and recommendations is provided below.

Limitations

The study primarily focused on laboratory-scale tests, which may not fully capture long-term durability under real-world field conditions such as variable weather, loading, and environmental exposure. Furthermore, for assessing lifecycle sustainability and structural integrity, the performance of materials over extended periods is necessary. Another limitation is the variability of byproduct composition depending on its source, which may affect the reproducibility and consistency of results.

Recommendations

For practical implementation, it is recommended that construction stakeholders and manufacturers in Pakistan pilot these byproduct-enhanced bricks and tuff tiles in real-world projects to validate their long-term performance under local climatic and loading conditions. Industry partnerships should be established to secure consistent supply chains for quality-controlled byproducts, alongside developing standardized production protocols ensuring uniformity and reliability. Additionally, governmental bodies could incentivize the adoption of these eco-friendly materials through subsidies or regulations promoting waste reutilization and emissions reduction in traditional brick kiln operations.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ASTM:

-

American society for testing and materials

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- CS:

-

Control sample

- CWP:

-

Ceramic waste powder

- ESP:

-

Eggshell powder

- GP:

-

Glass powder

- IOT:

-

Iron ore tailings

- MP:

-

Marble powder

- PKR:

-

Pakistani rupee

- PVC:

-

Polyvinyl chloride

- RHA:

-

Rice husk ash

- RHS:

-

Rice husk solid

- SBA:

-

Sugarcane bagasse ash

- SBS:

-

Sugarcane bagasse solid

- SCBA:

-

Sugarcane bagasse ash (alternate abbreviation used in some references)

- SDGs:

-

Sustainable development goals

- SDS:

-

Sawdust solid

- WMS:

-

Waste marble sludge

- WSA:

-

Wheat straw ash

- WSS:

-

Wheat straw solid

- XRD:

-

X–ray diffraction

References

Tasnim, F., Istiaque, F., Morshed, A. M. & Ahmad, M. U. A CFD investigation of conventional brick kilns, presented at AIP Conference Proceedings 2121(1), 1–7 (2019).

Al-Hdabi, A., Fakhraldin, M. K., Al-Fatlawy, R. A. & Ali, T. S. Investigate the effect of paper sludge Ash addition on the mechanical properties of granular materials. Pollack Periodica. 15 (3), 79–90 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Wonga, Y. C., Arulrajah, A. & Horpibulsuk, S. A review of studies on bricks using alternative materials and approaches. Constr. Build. Mater. 188, 1101–1108 (2018).

Mostafa, S. A., Agwa, I. S., Elboshy, B., Zeyad, A. M. & Hassan, A. M. S. The effect of lightweight geopolymer concrete containing air agent on Building envelope performance and internal thermal comfort. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 20, e03365 (2024).

Hassan, A. M. S., Aly, R. M. H., Alzahrani, A. M. Y., El-razik, M. M. A. & Shoukry, H. Improving fire resistance and energy performance of fast buildings made of Hollow polypropylene blocks. J. Building Eng. 46, 103830 (2022).

Hassan, A. M. S. et al. Evaluation of the thermo-physical, mechanical, and fire resistance performances of limestone calcined clay cement (LC3)-based lightweight rendering mortars. J. Building Eng. 71, 106495 (2023).

Khan, H. et al. Exploration of solid waste materials for sustainable manufacturing of cementitious composites. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 86606–86615 (2022).

Ibrahim, J. E. F. M., Tihtih, M., Şahin, E. İ., Basyooni, M. A. & Kocserha, I. Sustainable zeolitic tuff incorporating tea waste fired ceramic bricks: development and investigation. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 19, e02238 (2023).

Dharek, M. S., Vengala, M. M. S. B., Tangadagi, R. B. & J. & Performance evaluation of hybrid fiber reinforced concrete on engineering properties and life cycle assessment: A sustainable approach. J. Clean. Prod. 458, 142498 (2024).

Maddikeari, M. et al. A comprehensive review on the use of wastewater in the manufacturing of concrete: fostering sustainability through recycling. Recycling 9 (3), 45 (2024).

Munir, M. J., Kazmi, S. M. S., Wu, Y. F., Hanif, A. & Khan, M. U. A. Thermally efficient fired clay bricks incorporating waste marble sludge: an industrial-scale study. J. Clean. Prod. 174, 1122–1135 (2018).

Khan, H. et al. Exploration of solid waste materials for sustainable manufacturing of cementitious composites. Environmental Sci. Pollution Research (2022).

Süleyman Akpınar, S. T. A. Using volcanic tuff wastes instead of feldspar in ceramic tile production. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manage. 25, 2159–2170 (2023).

Sadek, D. M. Physico-mechanical properties of solid cement bricks containing recycled aggregates. J. Adv. Res. 3 (3), 253–260 (2012).

Dileep, A., Lal, A., Jamal, J. & Kunju, A. A. An experimental study on papercrete bricks manufactured using paper Pulp, lime and fly Ash. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. 10 (6), 968–974 (2021).

Attri, G. K., Gupta, R. C. & Shrivastava, S. Sustainable precast concrete blocks incorporating recycled concrete aggregate, stone crusher, and silica dust. J. Clean. Prod. 362, 132354 (2022).

Alela, A. A., Elboshy, B., Hassan, A. S., Mohamed, A. & Shaqour, E. Effect of the addition of sawdust on clay brick construction properties and thermal insulation: experimental and simulation approaches. J. Archit. Eng. 30 (1), 05023010 (2023).

Zat, T. et al. Potential re-use of sewage sludge as a Raw material in the production of eco-friendly bricks. J. Environ. Manage. 297, 01–12 (2021).

Hassan, A. M. S., Abdeen, A., Mohamed, A. S. & Elboshy, B. Thermal performance analysis of clay brick mixed with sludge and agriculture waste. Constr. Build. Mater. 344, 128267 (2022).

Thejas, H. K. & Hossiney, N. A short review on environmental impacts and application of iron ore tailings in development of sustainable eco-friendly bricks. Mater. Today: Proc. 61, 327–331 (2022).

Manjunatha, M., Seth, D., Balaji, K. V. G. D., Roy, S. & Tangadagi, R. B. Utilization of industrial-based PVC waste powder in self-compacting concrete: A sustainable Building material. J. Clean. Prod. 428, 139428 (2023).

Nandipati, S., Rao, G. V. R. S., Manjunatha, M., Dora, N. & Bahij, S. Potential Use of Sustainable Industrial Waste Byproducts in Fired and Unfired Brick Production. Advances in Civil Engineering 1–16 (2023). (2023).

Riaz, M. H., Khitab, A., Ahmad, S., Anwar, W. & Arshad, M. T. Use of ceramic waste powder for manufacturing durable and eco-friendly bricks. Asian J. Civil Eng. 21, 243–252 (2019).

Hassan, A. M. S., Mohamed, A. S., Shaqour, E., Shaqour, E. & Alela, A. H. A. Life cycle impact assessment of solid concrete blocks incorporating recycled fine and coarse crushed ceramic aggregates. J. Archit. Eng. 31 (1), 05024010 (2024).

Ngayakamo, B., Bello, A. & Onwualu, A. P. Development of eco-friendly fired clay bricks incorporated with granite and eggshell wastes. Environ. Challenges. 1, 100006 (2020).

Arsenović, M., Radojević, Z., Jakšić, Ž. & Pezo, L. Mathematical approach to application of industrial wastes in clay brick. Ceram. Int. 41 (3), 4890–4898 (2015).

Bories, C., Aouba, L., Vedrenne, E. & Vilarem, G. Fired clay bricks using agricultural biomass wastes: study and characterization. Constr. Build. Mater. 91, 158–163 (2015).

Kazmi, S. M. S., Abbas, S., Munir, M. J. & Khitab, A. Exploratory study on the effect of waste rice husk and sugarcane Bagasse ashes in burnt clay bricks. J. Building Eng. 7, 372–378 (2016).

Elakkiah, C. Rice husk Ash (RHA)—The future of concrete. Sustainable Constr. Building Materials 25 (2018).

Jongpradist, P., Homtragoon, W., Sukkarak, R., Kongkitkul, W. & Jamsawang, P. Efficiency of rice husk Ash as cementitious material in high-strength cement-admixed clay. Adv. Civil Eng. 2018, 01–11 (2018).

Bheel, N. et al. Use of rice husk Ash as cementitious material in concrete. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 9 (3), 4209–4212 (2019).

Amin, M. N., Hissan, S., Shahzada, K., Khan, K. & Bibi, T. Pozzolanic reactivity and the influence of rice husk Ash on early-age autogenous shrinkage of concrete. Front. Mater. 6, 01–13 (2019).

Minh, L. T. & Tram, N. X. T. Utilization of rice husk ash as partial replacement with cement for production of concrete brick, MATEC Web of Conferences 97 01121 (2017).

Ahmed, H., Ibrahim, I. M., Radwan, M. A. & Sadek, M. Preparation and analysis of cement bricks based on rice straw. Int. J. Emerg. Trends Technol. Comput. Sci. 8 (10), 7393–7403 (2020).

Mohammed, S. A. et al. An environmental sustainability roadmap for partially substituting agricultural waste for sand in cement blocks. Front. Built Environ. 9, 01–19 (2023).

Ghuge, J., Surale, S., Patil, D. B. M. & Bhutekar, S. B. Utilization of waste plastic in manufacturing of paver blocks. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 6 (4), 1967–1970 (2019).

Ogundairo, T. O., Adegoke, D. D. & Olofinnade, O. M. Akinwumi Sustainable use of recycled waste glass as an alternative material for building construction – A review. 1st International Conference on Sustainable Infrastructural Development, IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering 640, 1–12 (2019).

Wang, X., Chin, C. S. & Xia, J. Material characterization for sustainable concrete paving blocks. Appl. Sci. 9 (6), 01–15 (2019).

Chin, W. Q. et al. A sustainable reuse of Agro-Industrial wastes into green cement bricks. Materials 15 (5), 01–18 (2022).

Eliche-Quesada, D., Iglesias-Godino, F. J., Pérez-Villarejo, L. & Corpas-Iglesias, F. A. Replacement of the mixing fresh water by wastewater Olive oil extraction in the extrusion of ceramic bricks. Constr. Build. Mater. 68, 659–666 (2014).

Yeo, J. S., Koting, S., Onn, C. C. & Mo, K. H. Optimization of mix design of concrete paving block using response surface methodology. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2521, 012012 (2023).

Ahmed, S. O. Rice husk Ash as a partial replacement of cement in high strength concrete containing fly Ash. Int. J. Curr. Eng. Technol. 11 (2), 195–200 (2021).

International, A. S. T. M. ASTM C67 – Standard test methods for sampling and testing brick and structural clay tile. (ASTM International, 2018).

International, A. S. T. M. ASTM C936 – Standard specification for solid concrete interlocking paving units. (ASTM International, 2018).

Cordeiro, G. C., Andreão, P. V. & Tavares, L. M. Pozzolanic properties of ultrafine sugar cane Bagasse Ash produced by controlled burning. Heliyon 5 (10), e02566 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research has been supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R909), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors are also grateful to the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan for facilitating the experimentation and characterization work.

Funding

This research has been supported by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R909), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors are also grateful to the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan for facilitating the experimentation and characterization work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Khawaja Adeel Tariq: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing — Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Corresponding author. Aashir Waleed: Investigation, Methodology, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing. Muhammad Shahid: Validation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—Review & Editing. Muhammad Zahid: Software, Visualization, Formal analysis, Writing—Review & Editing. Amina Salhi: Revision of Manuscript—Analysis of research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tariq, K.A., Salhi, A., Waleed, A. et al. Eco-friendly bricks and tuff tiles from agricultural and industrial waste: advancing the United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals. Sci Rep 15, 36431 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20545-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20545-1