Abstract

Accurate segmentation of gastric cavities from ultrasound images remains a challenging task due to the presence of ultrasound shadow and varying anatomical structures. To address these challenges, we collected a Gastric Ultrasound Image (GUSI) dataset using transabdominal techniques, after administering an echoic cellulose-based gastric ultrasound contrast agent (TUS-OCCA), and annotated the gastric cavity regions. We propose a model called Shadow Adaptive Tracing U-net (SATU-net) for gastric cavity segmentation on the GUSI dataset. SATU-net is specifically designed for gastric cavity segmentation in ultrasound images. The method introduces an Adaptive Shadow Tracing Module (ASTM), Shadow Separation Module (SSM), and an affine transformation mechanism to mitigate the impact of ultrasound shadow. The affine transformation aligns ultrasound image regions to reduce geometric distortion, while the ASTM dynamically tracks and compensates for ultrasound shadow, and the SSM extracts the shadow separation image. Extensive experiments on the gastric ultrasound dataset demonstrate that SATU-net achieves superior segmentation performance compared to several state-of-the-art deep learning methods, with an IoU improvement of 2.26% over the second-best competitor. Further robustness analysis and limited external validation provide preliminary evidence that SATU-net generalizes across diverse clinical scenarios. Our method provides a robust solution for ultrasound image segmentation and can be extended to other medical imaging tasks. Additionally, the ASTM module can be flexibly applied to existing network frameworks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although the global incidence of gastric cancer (GC) has declined, it remains the fifth most common malignancy and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide1,2. The prognosis of GC patients is primarily determined by the stage of the disease, the presence of distant metastasis, and the timing of treatment. Early detection of existing lesions is critical for the treatment and survival of GC patients3,4,5,6.

Abdominal ultrasound examination is one of the most widely used diagnostic tools for the preliminary investigation of abdominal symptoms. It is a relatively easy, fast, and cost-effective non-invasive method to assess normal and pathological conditions of the hepatobiliary and gastrointestinal tracts7,8,9. However, due to the low resolution of ultrasound imaging and the complexity of different organs, ultrasound examinations heavily rely on the radiologist’s expertise. Misdiagnosis and missed diagnoses are common, particularly in underdeveloped countries and regions. Moreover, due to irregular and minute lesions, radiologists often require considerable time to make accurate diagnoses. Thus, developing automated and precise computer-aided ultrasound examination methods is crucial.

In recent years, the exploration of deep learning techniques has significantly advanced the field of computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) in ultrasound imaging. For ultrasound medical image segmentation tasks, the powerful nonlinear learning capabilities of fully convolutional networks (FCNs) and U-nets have achieved remarkable success10,11,12. Inspired by these advancements, a variety of segmentation tasks in ultrasound scenarios have been tackled using state-of-the-art deep learning techniques. For instance, in 2021, Liu et al. proposed a neonatal hip bone segmentation network that integrated an enhanced dual attention module, a two-class feature fusion module, and a coordinate convolution output head, achieving excellent results across multiple segmentation datasets13. That same year, Gilbert et al. introduced a novel approach where they used generative adversarial networks to create images from high-quality existing annotations. They then trained a convolutional neural network to accurately segment the left ventricle and left atrium using these synthetic images, which resulted in positive outcomes14. In 2021, Dong et al. leveraged Guided Backpropagation to drive U-Net, adding noise only in non-feature regions and fusing via Laplacian pyramid, achieving a denoising-feature preservation win-win in portable ultrasound and laying the groundwork for “feature-first” segmentation modules40. In 2022, Frank et al. used B-mode frame, vertical ultrasound shadow information, and pleural line information as inputs to a DNN network, achieving significant results in assessing COVID-19 severity15. In 2023, Chen et al. implemented a modified U-Net structure with an adaptive attention mechanism, substituting the standard double convolution configuration with a hybrid adaptive attention module. This adjustment demonstrated efficacy in segmenting breast tumors16. Kaur et al. plugged Grad-CAM into Xception-U-Net to yield GradXcepUNet, highlighting lesions with class-activation maps and enforcing explainability41. In 2024, Luo et al. employed a semi-supervised anomaly detection model based on an adjacent frame guided detection backbone, achieving high-precision segmentation of thyroid nodules in a video training set17.

Deep learning for gastric ultrasound segmentation remains limited, largely due to scarce public datasets and challenges from varied sampling planes, complex anatomy, and gas-induced shadows. As shown in Fig. 2, shadows occur at strong reflectors, high-attenuation zones18, and calcifications19,20, leading to missing structures or blurred boundaries. They also arise from poor probe contact or high-impedance interfaces (air–tissue or tissue–lesion)21. As illustrated in Fig. 2, an example of how ultrasound shadows originate in a specific image, the air trapped between the gastric body and the wall blocks the acoustic beam, splitting the stomach into two disconnected regions. This shadow artifact poses a major challenge to complete gastric recognition and segmentation. Its occurrence becomes even more frequent and severe when pathologies such as tumours or ulcers are present.

Recent advances in preoperative ultrasound imaging have included the use of transabdominal techniques after administering an echoic cellulose-based gastric ultrasound contrast agent (TUS-OCCA). This innovation has not only increased the detection rates for gastric cancers (GC), but also improved the assessment of the extent of GC invasion22,23.

To mitigate ultrasound shadow, Wang et al. (2021) employed a Cycle-GAN to learn from unpaired images and auxiliary masks, matching CNNs trained on manual labels in segmentation performance24. Frank et al. (2022) applied affine transformations and thresholding to generate vertical shadow masks for pulmonary shadow detection15. Xu et al. used shadow-consistent semi-supervised learning to guide feature extraction from shadow-free regions24, and Chen et al. (2023) introduced a semi-supervised, boundary-refined, shadow-aware network with mimic regions and masking blocks, achieving strong results on breast ultrasound data25.

In this work, we combine TUS-OCCA contrast imaging, affine rectification, and our SATU-net to address complex gastric anatomy and ultrasound shadow artifacts. First, an echoic cellulose agent distends the stomach, producing homogeneous mid-to-high echogenicity and minimizing mucus and air interference. Next, we apply affine transformations based on probe geometry to realign sector-shaped shadow regions into vertical rectangles, facilitating shadow mitigation. Finally, SATU-Net’s independent ASTM adapts to varying shadow depths and patterns, restoring obscured structures for accurate segmentation. Evaluated on the GUSI dataset, our approach achieves superior gastric cavity delineation under severe shadowing.

Methodology

a Ultrasound shadows from strong reflections, attenuation, poor probe contact and high-impedance interfaces. b Examples of how ultrasound shadow originates in specific images. c Original fan-shaped shadow pattern before affine mapping. d Rectified image after affine transformation, showing vertically aligned shadows. e Annotation of key points in Cartesian coordinates. f Polar coordinate system centered at point \(D\) for the sector-shaped field of view.

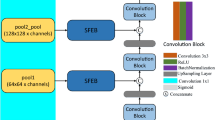

As shown in Fig. 1, the core architecture of the SATU-net model utilizes the well-established U-net framework, which is structured around an encoder (contracting) path and a decoder (expanding) path. The encoder path systematically extracts hierarchical features from the input image, and the decoder path is tasked with reconstructing these features into the segmented output.

The encoder path of SATU-net is strategically bifurcated into two distinct branches. The first branch utilizes ASTM to perform down-sampling on the input feature map via max pooling, systematically capturing the comprehensive shadow distribution across various spatial and contextual scales. Simultaneously, the second branch is dedicated to feature extraction, analogous to the traditional U-Net framework, but it innovatively integrates shadow feature information detected by the ASTM module across multiple scales. This integration is meticulously designed to enhance the algorithm’s ability to accurately segment the gastric cavity despite the presence of shadow.

Subsequently, SSM is employed to apply attention mechanisms on the extracted shadow features, generating shadow-free images. These shadow-free images are then incorporated into the shallow features of the encoder path to capture fine-grained details. Conversely, the shadow features are integrated into the deep features of the encoder path to enhance the network’s understanding of global context. This strategic integration is meticulously designed to bolster the algorithm’s capability to accurately segment the gastric cavity despite the presence of shadow.

The SATU-net decoder retains the U-shaped skip connections of the standard U-Net to preserve spatial details that may be lost during encoder downsampling, yet replaces every convolution with a wavelet-transform layer that simultaneously carries fine-edge cues and global context; a parameter-free inverse wavelet transform then up-samples the feature map, drastically reducing parameters and yielding the final gastric-cavity segmentation mask.

All experiments were conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Third Central Hospital of Tianjin (Approval No. IRB2024-069-01). Informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians.

Affine transformation

To increase the contact area between the probe and the patient’s skin, clinical abdominal ultrasound commonly uses a convex array probe. For convex array probes, several element transmit and receive apertures are arranged along the fan-shaped region at the front of the probe26,27,28,29,30. When an ultrasound wave encounters a medium that it cannot penetrate, such as air or bone, the wave’s energy is absorbed, reducing the clarity of subsequent images and causing ultrasound shadow, which typically exhibit a fan-shaped distribution. To address this, we apply affine transformations to the original ultrasound images. This adjustment aligns the image regions generated by each emitter to be perpendicular to the image, resulting in vertically rectangular distributions of the ultrasound shadow regions in the transformed images, as shown in Fig. 2. This facilitates the algorithm’s ability to accurately track and mitigate the impact of ultrasound shadow on the ultrasound images. During clinical gastric ultrasound examinations, the depth parameter on the ultrasound device is dynamically adjusted by the physician according to the target area and the patient’s physique. This results in varying field shapes under different depth settings. To address this, we develop a geometric-assisted sector-shaped field annotation method. First, a Cartesian coordinate system is established with the origin at the top-left corner of the image. Annotators then mark the intersection points of the inner arc and inner diameter \(A(x_A, y_A)\) and \(B(x_B, y_B)\), the lowest point of the inner arc \(C(x_C, y_C)\), and the left intersection of the outer arc and outer diameter \(E(x_E, y_E)\), as shown in Fig. 2. The coordinates are geometrically adjusted as follows:

where \(D(x_D, y_D)\) represents the coordinates of the center of the sector-shaped field of view, which can be calculated by:

Since the image field of view is distributed as a sector shape centered at \(D\), we establish a polar coordinate system with \(D\) as the origin, as shown in Fig. 2.

To ensure the rectangular image resulting from the affine transformation fills the entire image, we normalize the position of the image within the polar coordinate system. For each pixel \(I(\theta _i, R_i)\) in the polar coordinate system, the coordinate range is:

The normalized Cartesian coordinates for any point \(I(x_{\text {rect}_i}, y_{\text {rect}_i})\) are:

where \(W\) and \(H\) are the width and height of the output image, respectively.

Adaptive shadow tracing module

A key innovation of SATU-net is the introduction of the ASTM, specifically designed to address the challenge of ultrasound shadow in ultrasound images. The ASTM operates on the features extracted by the encoder path, enhancing the network’s ability to accurately segment the gastric cavity by tracing and compensating for shadows. The designed ASTM mainly consists of three parts: a shadow feature extraction layer with varying kernel sizes, a channel attention layer, and a shadow feature resizing block. Specifically, the input ultrasound image undergoes average pooling using 16 parallel Adaptive Shadow Tracing Cores (ASTC) of different sizes, resulting in the overall shadow feature of the image, as shown in Fig. 1.

Shadow Feature Extraction Layer: Leveraging the physics of ultrasound shadow formation, shadow artifacts predominantly distribute along the transducer’s receptive field in a fan-shaped pattern. After applying an affine transformation to the input ultrasound images, these shadow regions are rectified into rectangular dark patches of varying sizes. Through extensive ablation studies, we have determined the optimal combination of ASTC kernel sizes. The size configuration for each ASTC channel and the corresponding extracted shadow feature maps are summarized in Table 1.

Channel Attention Layer: To improve the performance of the SATU-net model in handling ultrasound shadow, we employ a Channel Attention Layer, which is specifically designed to enhance the extraction of shadow features. The Channel Attention Layer applies a Global Average Pooling (GAP) operation to the extracted shadow features to capture global spatial information. The resulting feature map is then passed through a fully connected (FC) layer, followed by a sigmoid activation function \(\sigma\) to compute the attention map. This mechanism enables the network to learn and apply adaptive attention weights to different channels, emphasizing the most informative channels while suppressing irrelevant ones.

Shadow Feature Resizing and Integration: The extracted shadow features are first adjusted to match the spatial dimensions of the encoder’s deep layers through max pooling and convolution. Max pooling reduces the spatial resolution of the shadow features, ensuring compatibility with the encoder’s feature map. The features are then refined via convolution to enhance their representation. After adjustment, the shadow features are integrated into the encoder path’s features from the 2nd to the 4th deep layers using skip connections. This fusion process ensures the network captures both fine-grained details and high-level context, improving the model’s ability to differentiate between the gastric cavity and ultrasound shadow, ultimately enhancing segmentation accuracy.

Shadow separation module

To eliminate ultrasound shadow, the shadow features extracted by the ASTM are processed in conjunction with the original image. Module structure as shown in Fig. 1. The first step is to normalize the channel attention of the shadow features, ensuring that the sum of attention across all channels equals 1. This normalization can be mathematically expressed as:

Where \(\text {Attention}_i\) is the attention for channel \(i\) and \(C\) is the total number of channels. The normalized channel attention is then applied to weight the shadow features, yielding the aggregated shadow features \(\textbf{F}_{agg}\), as follows:

Where \(\textbf{F}_i\) is the shadow feature of the i-th channel produced by the preceding Shadow Feature Extraction Layer in Table 1. Equation (6) therefore fuses multi-resolution shadow cues into a single illumination map that encodes both shadow geometry and the vertical intensity roll-off. Next, compute the average brightness \(\textbf{L}_{avg}\) of the input image:

Where \(I(x, y)\) is the pixel intensity at position \((x, y)\), and \(H\) and \(W\) are the height and width of the image. The shadow-compensated image features \(\textbf{F}_{comp}\) are then obtained by subtracting the average brightness from the aggregated shadow features. This zero-centering step converts the illumination map into a relative residual, mirroring the Retinex/homomorphic principle widely used in CV.

Finally, the shadow separation image features \(\textbf{F}_{output}\) are obtained by adding the shadow-compensated features to the original image features \(\textbf{F}_{input}\):

This process ensures the effective compensation of ultrasound shadow, enhancing the model’s ability to accurately segment the gastric cavity. The shadow separation image, computed using the shadow features as shown in Table 1. Additional image results can be found in Fig. 3. To quantitatively evaluate shadow-compensation performance, we selected ten representative images and computed–within the mask area of each image–the entropy and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) of all pixels before and after processing. The proposed method consistently reduced image entropy, indicating diminished noise and complexity in shadowed regions. Meanwhile, CNR also decreased; this is expected because shadow regions are homogenized and the intensity gap between tissue and shadow is narrowed. These trends demonstrate that the model effectively suppresses shadow artifacts, yielding more uniform and interpretable ultrasound images and thereby improving segmentation accuracy.

Loss function

In our study, we adopt a combined loss function that incorporates both Binary Cross Entropy (BCE) and the Dice loss to effectively handle two-class image segmentation tasks. The Binary Cross Entropy (BCE) term is widely used for its ability to measure the direct difference between predicted masks and ground-truth labels. Its definition is as follows:

Where \(Y(i,j) \in [0,1]\) denotes the ground-truth label of pixel \((i,j)\), and \(\hat{Y}(i,j) \in [0,1]\) represents the predicted masks. In this work, we employ BCE to minimize pixel-wise differences between the predictions and ground truth.

In addition, we include a Dice Loss term to address class imbalance and focus on overlap between the predicted and ground-truth masks, which is defined as:

The total loss function used in training our network combines both BCE and Dice losses, expressed as:

The Dice loss encourages the network to maximize the overlap between the prediction and the ground truth, while the BCE ensures accurate pixel-wise classification.

Datasets and experimental settings

Dataset

In this study, we employed two gastric ultrasound image datasets based on the TUS-OCCA protocol. The first dataset, named GUSI-A, was collected at Tianjin Third Central Hospital and comprises 793 images. Data acquisition followed the TUS-OCCA experimental standards17. After fasting for more than eight hours with no residual gastric contents, participants received a single oral dose of ultrasound contrast agent. Dynamic continuous scans were then performed with the patient in standing, left-lateral, or right-lateral positions using a Philips broadband convex abdominal probe (C5-1) to image the gastric cardia, fundus, body, angle, antrum, and pylorus. The seven standard gastric sections retained in the dataset and their distribution are shown in Table 2. In these images, the gastric cavity regions have been annotated. To ensure objectivity, all annotations were first carried out by three master’s students with ultrasound expertise following a standardized protocol, then validated by a doctoral student specializing in ultrasound, and finally overseen by three clinical gastric ultrasound experts.

Since there is no public TUS-OCCA dataset available for external verification, we used 21 images from 10 patients presenting to Beijing Friendship Hospital to form a relatively small test set with an average resolution of \(1260 \times 910\). The part of the gastric cavity in this data set was also annotated under the guidance of three clinical gastric ultrasound experts. All participants were informed during ultrasound examinations that ultrasound data could be used for research purposes.

Experimental settings and evaluation metrics

We utilized the Adam optimizer to train our network, with the initial learning rate established using a learning rate finder to determine the optimal range. During training, a stepwise learning rate scheduler dynamically adjusts the rate to ensure stable convergence and optimal performance. Optimal segmentation results were achieved when the epoch size and batch size were configured at 50 and 4, respectively. The proposed SATU-net model contains 16.6 million trainable parameters and requires 37.3 GFLOPs for a single forward pass. The average inference time per image is 6.8 ms on an NVIDIA A100 GPU, running Python 3.10 and PyTorch 2.3.1. We strictly enforced patient-wise splits throughout the experiments to eliminate any possibility of data leakage. To prevent overfitting and improve the generalization ability of our model, we applied data augmentation techniques to enhance the robustness of the model. These techniques included horizontal flipping, vertical flipping, and diagonal flipping to increase the number of labeled images. In our experiments, we used five widely used segmentation metrics to evaluate the accuracy of GUS segmentation, including accuracy, precision, recall, intersection over union (IoU), dice similarity coefficient (Dice) and specificity.

Experimental results

Ablation Study

To verify the contribution of each module in the proposed SATU-net model for gastric cavity segmentation, we designed an ablation study comparing the performance of the following four model configurations. Table 3 shows the experimental results of different components on GUSI-A. The ablation study demonstrated that adding the affine transformation or the ASTM alone to the U-net does not significantly improve its segmentation performance. However, when both are present, the model’s performance is significantly enhanced, especially in terms of IoU and Dice score, reaching 80.87% and 89.39%, respectively. This indicates a strong synergistic effect between the affine transformation and the ASTM. The affine transformation corrects the geometric distortion of the ultrasound images, transforming the originally fan-shaped shadow regions into rectangular ones. This provides more consistent and stable shadow features for the ASTM, allowing it to more effectively handle complex shadow structures and improve overall segmentation accuracy.

Comparison with state-of-the-art methods

To assess the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed method, we initially compared it with leading deep learning techniques for segmenting ultrasound and medical images. Our comparative methods include U-net31, R2U-Net32, AAU-net16, LGANet33, Swin-UNet34, Transfuse35, and FAT-Net36. To ensure a fair comparison, all competing methods were implemented in identical computing environments and subjected to the same data augmentation techniques during our experiments.

Table 4 displays typical challenging ultrasound images alongside the segmentation results from various competitors. U-Net, which utilizes simple stacked continuous convolutions to preserve more local information, fails to deliver superior segmentation performance due to its inability to model long-range dependencies.

AAU-net, using a hybrid adaptive attention module, can capture more features under different receptive fields and performs better in edge fitting. However, due to the difficulty in identifying gastric cavities in areas with irregular shapes and sizes of ultrasound shadow under dynamic receptive fields, large areas of false positives (FP) or false negatives (FN) are generated.

R2U-Net, by introducing recurrent residual convolutional layers, can accurately segment the texture details of images, but under the influence of ultrasound shadow, the texture features of gastric cavity edges are inconsistent. As a result, R2U-Net cannot accurately segment the target region in gastric ultrasound images with severe ultrasound shadow.

LGANet, with the introduction of a Local Focus Module, focuses more on the image boundary regions and can analyze the contextual structural features of boundary regions through a Global Augmentation Module. This allows LGANet to accurately segment the target region even when the boundary is unclear. However, the widespread presence of ultrasound shadow in the training set, especially large shadow areas, severely interferes with LGANet’s ability to learn boundary textures, resulting in large areas of FP due to undetected accurate boundaries.

FAT-Net, which utilizes a dual-encoder structure based on CNN and Transformer, uses CNN to extract local features and Transformer to capture global contextual information. However, when ultrasound shadow penetrate the gastric cavity from different directions, FAT-Net struggles to learn all the combinations of ultrasound shadow and gastric cavity patterns, especially with a limited training set. This leads to parts of the gastric cavity being inaccurately segmented, forming large FN areas.

Swin-Unet, leveraging a pure Transformer architecture with a shifted window attention mechanism, excels at capturing both global contextual information and local details. By integrating a hierarchical Swin Transformer encoder and patch-expanding layers in the decoder, Swin-Unet demonstrated strong performance in medical image segmentation tasks. However, the use of patch-expanding layers for upsampling, while effective in maintaining spatial resolution, may introduce certain limitations in boundary refinement. The resulting segmented edges from Swin-Unet sometimes exhibit jagged or serrated ultrasound shadow. This can be attributed to the fixed-size patch mechanism in the Transformer, which might not be flexible enough to handle fine-grained boundary details when dealing with high variability in local textures, such as those found in the gastric cavity. The fixed nature of patches may limit the model’s ability to precisely capture subtle variations along the boundaries, causing jagged edges in the segmentation results.

Transfuse, leveraging a parallel-in-branch architecture combining CNNs and Transformers, excels in capturing both local spatial features and global contextual information. This dual-path design enables Transfuse to strike a balance between maintaining fine-grained details and capturing long-range dependencies. However, in gastric ultrasound segmentation, where training data is often sparse and ultrasound shadow are highly variable, the model might not generalize well to all cases, resulting in segmentation inaccuracies, particularly in challenging regions where both local and global information are crucial for accurate segmentation.

Our SATU-net extracts alpha shadow features of different sizes from ultrasound images through the ASTM and integrates these features into each layer, achieving the best segmentation results compared to other competitors, particularly in images affected by large alpha shadows. The quantitative evaluation results of different segmentation methods are summarized in Table 3, where our method outperforms others on five key metrics. Specifically, the performance values on the GUSI-A dataset are 97.39%, 89.26%, 89.63%, 80.87%, and 89.39% for each metric. When compared to the second-best results, our method shows improvements of 0.28%, 0.17%, 0.98%, 2.26%, and 1.37%, respectively.

External verification

Due to the fundamentally different signal formation in ultrasound–where raw acoustic echoes undergo filtering, logarithmic compression, and scan-conversion–images from different scanner–probe combinations exhibit substantial texture and contrast variability. Such domain shifts can degrade segmentation performance when a model trained on one device’s data is applied to another. To assess generalization, we evaluated our SATU-net, trained on the GUSI-A cohort (793 TUS-OCCA images), on the independent GUSI-B set (21 images from ten patients, acquired with different ultrasound systems). Despite GUSI-B’s limited size, our method consistently led all competing architectures across six metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, IoU, Dice, Specificity; Table 5), demonstrating its robustness to device-specific appearance variations and its suitability for real-world gastric ultrasound segmentation.

Discussion

In this work, we present SATU-net, a dual-branch Shadow Adaptive Tracing U-Net that leverages affine geometric rectification and an ASTM for robust gastric cavity segmentation under severe ultrasound shadowing. Ablation experiments demonstrate a strong synergistic effect: the affine pre-warp aligns fan-shaped shadow artifacts into axis-aligned rectangles, providing consistent receptive-field contexts for ASTM’s multi-scale shadow kernels. When combined, these components yield significant gains in IoU and Dice over the baseline U-Net, validating our design for feature fusion under adverse imaging conditions.

Compared to state-of-the-art backbones (U-Net, R2U-Net, AAU-Net, LGANet, Swin-UNet), SATU-net’s shadow-aware attention and shadow-separation branch consistently improve boundary delineation and mitigate false positives in low-contrast regions. However, large contiguous shadow regions and inter-device texture shifts still pose challenges, leading to occasional missing edges and domain-shift degradations. Future work will explore transformer-based global context modules and boundary-aware loss functions to further enhance robustness, and extend our framework to volumetric gastric modeling and lesion localization for broader clinical deployment.

Conclusion

To better address the challenges posed by ultrasound shadow and complex anatomical structures in gastric cavity segmentation, we propose SATU-net, a novel Shadow Adaptive Tracing U-net, specifically designed for ultrasound image segmentation tasks. By integrating affine transformation and the ASTM, the network can more accurately restore normal gastric structures under varying degrees of shadow interference. The proposed model significantly improves segmentation accuracy in the presence of ultrasound shadow. Extensive experiments, including comparative studies with state-of-the-art segmentation methods, robustness analyses, and external validation, demonstrated the superior performance of SATU-net in gastric cavity segmentation tasks. The experimental results show that SATU-net surpasses existing methods on several metrics and provides preliminary evidence of generalization across devices. We believe that SATU-net provides a robust tool for gastric ultrasound image segmentation and will contribute to advancing the field of computer-aided diagnosis. In the future, we plan to extend the scope of SATU-net to medical image captioning tasks. Accurate segmentation masks produced by SATU-net can serve as pixel-level prior knowledge to guide radiology-report generation, thereby automating clinical narratives, improving interpretability, and supporting decision-making, building on recent advances37,38,39.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author, Jun Tian (jtian@nankai.edu.cn), upon reasonable request.

References

Kim, M. et al. Gastric cancer: development and validation of a CT-based model to predict peritoneal metastasis. Acta Radiol. 61, 732–742 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Evaluation of transabdominal ultrasound after oral administration of an echoic cellulose-based gastric ultrasound contrast agent for gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 15, 1–8 (2015).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, J., Yang, L. & Huang, S. A meta-analysis of the utility of transabdominal ultrasound for evaluation of gastric cancer. Medicine 100, e26928 (2021).

Chen, C. N. et al. Association between color Doppler vascularity index, angiogenesis-related molecules, and clinical outcomes in gastric cancer. J. Surg. Oncol. 99, 402–408 (2009).

Shi, H. et al. Double contrast-enhanced two-dimensional and three-dimensional ultrasonography for evaluation of gastric lesions. World J. Gastroenterol. 18, 4136 (2012).

Pan, M. et al. Double contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in preoperative Borrmann classification of advanced gastric carcinoma: comparison with histopathology. Sci. Rep. 3, 3338 (2013).

Maconi, G. et al. Gastrointestinal ultrasound in functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract–EFSUMB consensus statement. Ultrasound Int. Open 7, E14–E24 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Preliminary opinion on assessment categories of stomach ultrasound report and data system (Su-RADS). Gastric Cancer 21, 879–888 (2018).

Urakawa, S. et al. Preoperative diagnosis of tumor depth in gastric cancer using transabdominal ultrasonography compared to using endoscopy and computed tomography. Surg. Endosc. 37, 3807–3813 (2023).

Huang, R. et al. Boundary-rendering network for breast lesion segmentation in ultrasound images. Med. Image Anal. 80, 102478 (2022).

Xian, M., Zhang, Y. & Cheng, H. D. Fully automatic segmentation of breast ultrasound images based on breast characteristics in space and frequency domains. Pattern Recognit. 48, 485–497 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Deep attentive features for prostate segmentation in 3D transrectal ultrasound. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 2768–2778 (2019).

Liu, R. et al. NHBS-Net: A feature fusion attention network for ultrasound neonatal hip bone segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 40, 3446–3458 (2021).

Gilbert, A. et al. Generating synthetic labeled data from existing anatomical models: an example with echocardiography segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 40, 2783–2794 (2021).

Frank, O. et al. Integrating domain knowledge into deep networks for lung ultrasound with applications to COVID-19. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 571–581 (2021).

Chen, G., Li, L., Dai, Y., Zhang, J. & Yap, M. H. AAU-Net: an adaptive attention U-Net for breast lesions segmentation in ultrasound images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 42, 1289–1300 (2023).

Luo, X. et al. Semi-supervised thyroid nodule detection in ultrasound videos. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 43(5), 1792–803 (2024).

Kremkau, F. W. & Taylor, K. J. Artifacts in ultrasound imaging. J. Ultrasound Med. 5, 227–237 (1986).

Choi, S. H., Kim, E. K., Kim, S. J. & Kwak, J. Y. Thyroid ultrasonography: pitfalls and techniques. Korean J. Radiol. 15, 267–276 (2014).

Le, H. T. et al. Imaging artifacts in echocardiography. Anesth. Analg. 122, 633–646 (2016).

Alsinan, A. Z., Patel, V. M. & Hacihaliloglu, I. Bone shadow segmentation from ultrasound data for orthopedic surgery using GAN. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 15, 1477–1485 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Gastric lesions: demonstrated by transabdominal ultrasound after oral administration of an echoic cellulose-based gastric ultrasound contrast agent. Ultraschall Med. Eur. J. Ultrasound 37, 405–411 (2016).

Liu, Z. et al. Evaluation of transabdominal ultrasound after oral administration of an echoic cellulose-based gastric ultrasound contrast agent for gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 15, 1–8 (2015).

Xu, X. et al. Shadow-consistent semi-supervised learning for prostate ultrasound segmentation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 1331–1345 (2021).

Chen, F. et al. Deep semi-supervised ultrasound image segmentation by using a shadow aware network with boundary refinement. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 42(12), 3779–93 (2023).

Pedersen, M. H., Gammelmark, K. L. & Jensen, J. A. In-vivo evaluation of convex array synthetic aperture imaging. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 33, 37–47 (2007).

Demi, L. Practical guide to ultrasound beam forming: beam pattern and image reconstruction analysis. Appl. Sci. 8, 1544 (2018).

Khuri-Yakub B. T. et al. Miniaturized ultrasound imaging probes enabled by CMUT arrays with integrated frontend electronic circuits. In Proc. 2010 Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol., 5987–5990 (2010).

Yun, Y. H., Jho, M. J., Kim, Y. T. & Lee, M. Testing of a diagnostic ultrasonic array probe and estimation of the acoustic power using radiation conductance. IEEE Sens. J. 12, 965–966 (2011).

Noda T., Tomii N., Azuma T. & Sakuma I. Self-shape estimation algorithm for flexible ultrasonic transducer array probe by minimizing entropy of reconstructed image. In Proc. 2019 IEEE Int. Ultrasonics Symp., 131–134 (2019).

Ronneberger O., Fischer P. & Brox T. U-Net: convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proc. 18th Int. Conf. Med. Image Comput. Comput.-Assist. Interv. MICCAI 2015, 234–241 (2015).

Alom M.Z., Hasan M., Yakopcic C., Taha T.M. & Asari V.K. Recurrent residual convolutional neural network based on U-Net (R2U-Net) for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.06955 (2018).

Guo Q., Fang X., Wang L., Zhang E. & Liu Z. LGANet: Local-global augmentation network for skin lesion segmentation. In Proc. 2023 IEEE 20th Int. Symp. Biomed. Imaging (ISBI), 1–5 (2023).

Cao H. et al. Swin-UNet: UNet-like pure transformer for medical image segmentation. In Proc. Eur. Conf. Comput. Vis., 205–218 (2022).

Zhang Y., Liu H. & Hu Q. Transfuse: fusing transformers and CNNs for medical image segmentation. In Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. – MICCAI 2021, 14–24 (2021).

Wu, H. et al. FAT-Net: feature adaptive transformers for automated skin lesion segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 76, 102327 (2022).

Sharma, D., Dhiman, C. & Kumar, D. FDT–Dr2T: a unified dense radiology report generation transformer framework for X-ray images. Mach. Vis. Appl. 35, 68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00138-024-01544-0 (2024).

Song W., Tang L., Lin M., Shih G., Ding Y. & Peng Y. Prior knowledge enhances radiology report generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.03761 (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2201.03761

Beddiar, D.-R., Oussalah, M. & Seppänen, T. Automatic captioning for medical imaging (MIC): a rapid review of literature. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 4019–4076. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-022-10270-w (2023).

Dong, G., Ma, Y. & Basu, A. Feature-guided CNN for denoising images from portable ultrasound devices. IEEE Access 99, 1–1. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3059003 (2021).

Kaur, A., Dong, G. & Basu, A. GradXcepUNet: Explainable AI based medical image segmentation. In Smart Multimedia, ser. LNCS 13782, 174–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22061-6_13 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Young Talents Research Project of College of Software, Nankai University under Grant 63243193, College of Software, Nankai University, Tianjin, China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Z. conceptualized the study, developed the methodology and software, performed the investigation, and wrote the original draft. T.Z. and D.L. curated data and conducted investigations. S.W. contributed to the investigation, methodology, formal analysis, and manuscript revision. X.S. conducted investigation, methodology design, and formal analysis. Y.Y. performed data curation and contributed to methodology. L.M. curated data and revised the manuscript. C.F. revised the manuscript. Z.N. contributed to data curation. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, H., Zhou, T., Wang, S. et al. SATU-net: a shadow adaptive tracing U-net for gastric cavity segmentation based on the principle of ultrasound imaging. Sci Rep 15, 36799 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20687-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-20687-2