Abstract

Given the nutritional importance of bread in the Iranian diet, ensuring its safety regarding chemical contaminants is crucial. This study assesses the potential health risks posed by heavy metals in bread available in Iran. A total of 248 bread samples were collected from 11 provinces during winter 2020. After sample preparation, the concentration of heavy metals was measured using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy. A health risk assessment model was employed to evaluate health effects and carcinogenic potential. The average concentrations of Copper (Cu), Zinc (Zn), Iron (Fe), Cadmium (Cd), Aluminum (Al), Cobalt (Co), Lead (Pb), Chromium (Cr), Nickel (Ni), and Mercury (Hg) were 3.08 ± 1.24, 13.6 ± 44.94, 59.24 ± 30.62, 0.004 ± 0.02, 4.98 ± 2.85, 0.01 ± 0.03, 0.65 ± 1.71, 1 ± 1.42, 0.05 ± 0.23, and 0.03 ± 0.12 mg/kg dry weight, respectively. Notably, the levels of Pb (0.65 ± 1.71 mg/kg) and Cr (1 ± 1.42 mg/kg) exceeded the WHO/FAO and Iranian National Standards threshold levels for both children and adults, indicating potential health risks. Overall, these findings suggest potential health and carcinogenic risks associated with heavy metals contamination in bread. Continuous monitoring of wheat and derived products is recommended to safeguard public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food safety is a critical global concern due to the rising prevalence of chemical contaminants, particularly potentially toxic elements (PTEs), in staple foods1,2,3. Defined as elements with a density greater than 5 g/cm³, PTEs such as cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), chromium (Cr), mercury (Hg), and arsenic (As) pose significant health risks due to their environmental persistence, toxicity, and potential for bioaccumulation4,5,6,7. Chronic exposure to PTEs through food consumption is linked to severe health effects, including kidney and liver damage, neurological disorders, and increased cancer risk, with children being particularly vulnerable due to higher absorption rates and lower body weight8. According to classifications by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), manganese (Mn), chromium (Cr), and cadmium (Cd) are non-carcinogenic, while As (group 1), Cr (group 2B), Ni (group 2B), Cd (group 1), Co (group 2B), and Pb (group 2B) are classified as metals with potential carcinogenic properties8,9.

Epidemiological studies indicate that consuming certain levels of PTEs can have lasting effects on dental health, renal function, and neurological conditions, with a pronounced impact on cancer incidence10,11. Therefore, a method for assessing health risks is essential to analyze potential adverse effects on humans exposed to these risk factors. The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has developed a risk assessment method to estimate the potential health risks of pollutants12. Health risk assessment provides insights into the health and environmental consequences of various factors and plays a vital role in developing health programs and actions to prevent diseases and promote community health.

Monitoring PTEs in staple foods like bread is critical due to their widespread consumption and potential as contamination vectors13,14. Bread, a primary dietary source in many countries, is particularly significant in Iran, where per capita consumption (420 g/day) is nearly double that of Europe13,15.

Given its nutritional importance, monitoring HM contamination in bread is essential. However, existing studies on HM pollution in Iranian bread are limited, often focusing on a few metals and small sample sizes within specific regions. This study addresses these gaps by: (1) quantifying levels of 10 potentially toxic elements (Fe, Zn, Cu, aluminum (Al), Co, Hg, Cr, Ni, Pb, Cd) in 248 bread samples across 11 Iranian provinces; (2) employing Monte Carlo simulation for robust health risk assessment for children and adults; and (3) comparing PTE concentrations with national and international standards. By providing a comprehensive, national-level analysis, this work offers novel insights into PTE contamination in a dietary staple, contributing to global food safety research.

Materials and methods

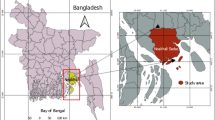

Sampling, storage, and transportation

We calculated the sample size for PTE analysis using a factorial design, accounting for 11 provinces (A–K) with major flour factories, five repetitions, and a 13% sample loss probability. In winter 2020, we collected 248 bread samples, stored them in pre-washed polyethylene bottles rinsed with double-distilled water, and transported them under cool, dark conditions at 4 °C until analysis. We prepared 10 g bread samples using standard AOAC (2012) methods16,17. Samples were dried at 100 °C to constant weight, homogenized, passed through a 2 mm sieve, and stored in polyethylene bottles at room temperature for analysis.

Chemical analysis

We analyzed bread samples for PTEs content using inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, Spectro Arcos, model 76004555, Germany) following the EPA 3050B method16. All acids, reagents, and standard solutions (stock, internal, and multi-element) were sourced from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). ICP-OES provided high sensitivity, accuracy, and a broad dynamic range for multi-element PTE analysis in food samples18,19.We calibrated the instrument using blanks and standards to ensure signal integrity, preparing standard solutions with concentrations based on prior studies and the limit of detection (LOD). Calibration curve correlation coefficients exceeded 0.99 for each PTE.

Quality control and assurance

Glassware and plastic bottles were cleaned with diluted nitric acid (HNO₃) for 24 h, rinsed with deionized water, dried at room temperature, and stored in airtight containers. We estimated the LOD for bread samples using a standard method (Table S1) and measured each sample in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. Certified reference materials (CRMs) and standard solutions with known PTE concentrations served as controls to verify accuracy, a critical practice for ICP-OES measurements16,20. After every tenth sample, we analyzed a control to confirm precision, achieving recovery rates of 80.5% to 100.6% (acceptable range: 80%–120%). Concentrations were reported in mg/kg (dry weight basis), with mean values interpreted at a 95% confidence level.

Human health risk assessment

Non-carcinogenic risk assessment

Risk assessment involves identifying, analyzing, and evaluating risks through four stages: hazard identification, dose-response assessment, exposure assessment, and risk characterization21. Non-carcinogenic risk assessment of PTEs in samples of flour and bread was conducted using the hazard quotient (HQ) method proposed by the 2007 EPA. We calculated the estimated daily intake (EDI), targethazard quotient (THQ), and hazard index (HI) using Eqs. (1–3)22 :

Here, EDI is the estimated daily intake (mg/kg/day), EF is exposure frequency (days/year), ED is exposure duration (years), IR is bread consumption rate (kg/day), AT is averaging time (years × days), BW is body weight (kg), and C is PTEs concentration (mg/kg dry weight) (Table S2). Reference doses (RfD, mg/kg/day) were: Cd 0.001, Ni 0.02, Cu 0.04, Cr 0.003, Fe 0.7, Zn 0.3, Al 0.7, Hg 0.0004, Co 0.0004, and Pb 0.00355,23,24. Aligns with EPA guidelines for risk assessments, Undetected concentrations were assigned a value of zero25. THQ < 1 indicates no non-carcinogenic risk, while THQ > 1 suggests potential effects21,26.

Evaluation of carcinogenic risk exposure

In addition to non-carcinogenic risks, we evaluated carcinogenic risks for Cd and Pb using Eq. (4):

EDI represents estimated daily intake (mg/kg/day), and CSF is the cancer slope factor (mg/kg/day), with EPA values of 0.38 for Cd and 0.0085 for Pb 5,23,24. According to EPA guidelines, CR < 10⁻⁶ is negligible, 10−⁴ to 10−⁶ is acceptable, and > 10−⁴ is unacceptable5,21,27.

Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis

Conventional risk assessments estimate risk as a single-point value, quantifying uncertainty and variability around this estimate28. The EPA recommends Monte Carlo simulation for precise risk estimates; thus, we employed this approach, relying on mathematical statistics and probability theory, to model uncertainty through random sampling and probability distributions, minimizing uncertainty in this study. We conducted Monte Carlo modeling with Crystal Ball software (version 11.1.34190), performing 10,000 iterations at 95% confidence to assess the 95th percentile health risk, hazard index, and carcinogenic risk. The choice of 10,000 iterations was based on EPA recommendations and standard practices in environmental risk assessment, ensuring convergence of the output distributions and stable estimates of risk metrics, as supported by previous studies29. The 95th percentile was selected as the cutoff point to represent a conservative estimate of risk, capturing the upper bound of exposure for the majority of the population while aligning with EPA guidelines for health risk assessments29,30,31. Probability distributions for input parameters were assigned based on empirical data and literature. Heavy metals concentrations (C) followed a lognormal distribution to account for their typically skewed nature in environmental samples. Bread consumption rate (IR) was modeled as a lognormal distribution, reflecting variability in dietary habits. Exposure frequency (EF) and exposure duration (ED) were assigned uniform distributions due to their consistent ranges across populations, while body weight (BW) followed a normal distribution based on the natural variability in human populations. Averaging time (AT) was modeled as a uniform distribution. These distributions were selected to reflect realistic variability and uncertainty in exposure parameters, as recommended by EPA guidelines and previous studies29.Sensitivity analysis evaluated the influence of each variable on risk outcomes32,33,34. All risk assessment parameters are detailed in Table S2.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed data using SPSS (version 19). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test assessed data normality. We compared PTE levels in bread samples with the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normal data and one-tailed ANOVA for normal data. A significance level of 0.05 was adopted, with p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics (frequency, mean, standard deviation) quantified differences in PTE concentrations.

Results

This study evaluated 248 bread samples for PTEs content. Table 1 presents the concentrations of 10 PTEs across four bread types (lavash, taftoon, barbari, sangak), with statistical comparisons using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Only Fe and Zn concentrations varied significantly across bread types (P < 0.05). Sangak bread had the highest Zn concentration, while taftoon bread had the highest Fe concentration.

Among the 11 PTEs analyzed, Fe was found in 100% of the samples, Zn was detected in 99.59% (247 samples), Al in 96% (238 samples), Cu in 91.53% (227 samples), Cr in 63.30% (157 samples), Pb in 29% (72 samples), Co in 18.54% (46 samples), Ni in 12.50% (31 samples), Hg in 9.67% (24 samples), and Cd in 8.87% (22 samples).

Level of heavy metals in bread samples

Figure 1 shows average PTEs levels in four bread types (lavash, taftoon, barbari, sangak) from 11 Iranian provinces. As shown in Fig. 1, no specific trend was observed in the concentration of heavy metals across different provinces. However, comparison with national and international standards revealed that the levels of Fe, Cr, Al, Hg, and Cd in all bread types exceeded WHO and FAO standards. In contrast, Zn and Cu levels were below these standards (Table 2; Fig. 1).

(a) illustrates the concentration of toxic elements (mg/kg) found in various types of bread, compared to the maximum permissible limits established by WHO/FAO guidelines. The red line represents the threshold for each element. (b) illustrates the concentration of toxic elements (mg/kg) found in various types of bread, compared to the maximum permissible limits established by WHO/FAO guidelines. The red line represents the threshold for each element.

Human health risk assessment

The average daily intake (EDI) of PTEs ranked as follows for both children and adults: Fe > Zn > Al > Cu > Cr > Pb > Ni > Co. Notably, the EDI for Pb through bread consumption exceeded the allowable daily intake for both groups (Table S3).

Due to their low detection rates (< 30% of samples), Hg, Cd, Co, Pb, and Ni were excluded from hazard index (HI) calculations to avoid overgeneralization. The target hazard quotient (THQ) for Cr exceeded the safe threshold (THQ > 1) in adults. In children, THQ values for Cr and Fe also exceeded this threshold. The HI for children from bread consumption was 2.35 times higher than for adults, surpassing the safe threshold (HI > 1) for both groups (Table 3).

In this study, the risk of carcinogenesis was based on the levels of Cd and Pb. Due to the detection of these toxic metals in only four provinces (A, B, D, H), the carcinogenic risk values are based on data from these provinces and cannot be generalized to other provinces in Iran. The average carcinogenic risk from bread consumption for children and adults was found to be 8.67 × 10− 6 ± 2.11 × 10− 5 and 2.05 × 10− 5 ± 5. × 10− 5, respectively (Table 4). Therefore, carcinogenic risks for Cd and Pb, assessed in four provinces, were moderate (10⁻⁴ < CR ≤ 10⁻⁶).

Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis

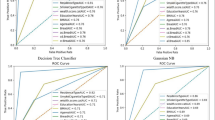

The risk index associated with bread consumption, considering appropriate confidence intervals (95%), was evaluated using the Crystal Ball software with 10,000 iterations. In assessing health risks, all measures should be taken cautiously; therefore, the 95th percentile was considered as the cutoff point. As shown in Fig. 2, with 95% confidence, the HI for children is in the range of 3.37 to 8.53, whereas for adults, it ranges from 1.52 to 3.78, significantly exceeding the permissible limit set by the EPA (HI > 1). Additionally, as shown in Fig. 2, with 95% confidence, the CR from bread consumption for children ranges from 3.47 × 10− 6 to 1.84 × 10− 5, while for adults, it ranges from 8.37 × 10− 6 to 4.08 × 10⁻⁵. These values indicate a moderate risk level (10⁻⁴ < CR ≤ 10⁻⁶).

Sensitivity analysis revealed that Cr concentration was the primary driver of non-carcinogenic risk, contributing 45.8% to HI variance in children and 44.7% in adults, based on contribution-to-variance metrics. Fe concentration was the second-largest contributor, with 17.6% in children and 17.4% in adults. Other parameters, including bread consumption rate (IR, 13.1% in children, -13.5% in adults), body weight (BW, -12.9% in children, 12.7% in adults), and exposure duration (ED, 3.9% in children, 4.9% in adults), had lesser impacts. Negative BW correlations reflect inverse exposure-dose relationships. For carcinogenic risk, Pb concentration dominated (32.2% in children, 36.8% in adults), followed by Cd concentration (29.3% in children, 31.8% in adults). The analysis underscores the need to prioritize Pb/Cd reduction in mitigation strategies. Other variables contributing including body weight (BW, -17.6% in children, -20.2% in adults), bread consumption rate (IR, 16.5% in children, 13.5% in adults), and exposure duration (ED, 1.9% in children, 0.2% in adults), had lesser impacts (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Evaluation of heavy metal concentrations in bread

We analyzed 248 bread samples for PTEs concentrations, focusing on four types: lavash, taftoon, barbari, and sangak. Fe and Zn concentrations varied significantly across bread types (P < 0.05). Sangak bread exhibited the highest Zn levels, likely due to its traditional baking on a hot pebble bed, which may transfer Zn from naturally abundant soil and rocks35,36,37,38. Conversely, the higher Fe content in taftoon bread may stem from the baking process itself, as evidence suggests that baking significantly influences iron concentrations39. The high levels of Fe in taftoon bread could also be due to the use of cast iron, which is frequently used in rotary kilns because of its cost-effectiveness and ease of production. Variations in Zn and Fe concentrations may also arise from the selective enrichment of some samples while others remain deficient16,40.

Concentrations of Fe, Cr, Pb, Al, Cd, and Hg in all bread types exceeded WHO/FAO safety limits, while Zn and Cu levels were below these standards. Pb contamination likely stems from flour production equipment, bakery exhaust, and contaminated water, with bakeries near busy roads at higher risk due to air pollution16,41. Studies have shown that Pb levels in wheat and bread are frequently elevated in provinces adjacent to industrial zones and high-traffic areas. For example, research in Zanjan province, where Pb–Zn mining is active, found significant Pb deposition onto agricultural soils from atmospheric emissions, which subsequently entered wheat grains and bread42. Similarly, peri-urban farms near major highways, such as those in Isfahan, have recorded increased Pb levels from vehicular exhaust particulates43.Consistent with our findings, a study by Lebbos et al. in Lebanon indicated that Pb concentrations in some pitta bread brands exceeded permissible standards44. Ghoreishy et al. (2018) reported significantly higher Pb levels in bread samples from Isfahan, Iran than the safe limits established by Codex41. Similar concerns were raised by Bossou et al., who investigated health risks associated with Pb exposure among bread consumers in Benin45. Olmez et al. found that Pb levels in flour samples from Çorum, Turkey, also exceeded safety standards46. However, studies by Kianpour et al. (2017) in Hamedan47 and Khodayi et al. (2022) in Isfahan showed Pb levels below FAO/WHO limits48. Basaran (2022)49 reported Pb concentrations in bread samples ranging from 0.002 to 0.115 mg/kg, lower than our findings.

Iron is essential for the growth and survival of nearly all living organisms. Sources of iron contamination in bread include corrosion of production lines and contact with contaminated surfaces, as well as metallic contamination of water and salt used in bread-making39,50,51. Additionally, the enrichment of wheat flour with iron contributes to higher iron levels in bread16. In Iran, elevated Fe levels in bread have also been linked to the common use of cast-iron baking plates in traditional ovens, where prolonged high-temperature contact facilitates Fe leaching into dough16. Additionally, studies in Neyshabur and Mashhad have reported that the application of animal manure and phosphate fertilizers—often containing Fe impurities—enriches agricultural soils with iron, increasing its uptake by wheat52. A study by Woldetsadik et al. on traditional Ethiopian flatbread (injera) found that Fe concentrations exceeded the maximum permissible limits established by various organizations53. Khodayi et al. (2022)48 and Ghasemi et al. (2021)16 also reported Fe levels in bread samples surpassing FAO/WHO recommendations. Ozbek and Akman found Fe concentrations in various types of bread, including white and wholemeal bread, ranging from 15 to 68.7 mg/kg54. Notably, the mean Fe concentration in our study exceeded the average reported by Feyzi et al. (2017) of 30.31 ± 6.8 mg/kg55.

Chromium is prevalent due to its geological origin and extensive industrial use56. Wheat has a high biological accumulation capacity for chromium, meaning that chromium-contaminated soil and water can easily transfer to wheat and its products57. Additionally, stainless-steel equipment used in food processing may leach chromium during milling and baking58. Another significant pathway is irrigation with contaminated groundwater near industrial parks, such as in Yazd and Isfahan provinces, where Cr from leather tanning and metal plating industries has been detected in both soils and wheat grains59. In alignment with our findings, Adebiyi et al.60 reported Cr levels in Nigerian bread ranging from 6.40 to 10.20 mg/kg, exceeding WHO limits. The increased chromium levels in our analyzed bread samples may result from the absorption of minerals from contaminated soil60. Studies in Mashhad City16 similarly found Cr concentrations exceeding FAO limits, while a study on Turkish bread58 reported an average Cr level of 0.062 ± 0.083 mg/kg, lower than our findings.

Cadmium is typically found in low concentrations in soil and is released into the environment through natural and industrial processes61,62. In Iranian wheat production, Cd contamination often arises from the use of phosphate fertilizers, which naturally contain cadmium, and from sewage sludge application on farmlands. For instance, a survey in northern Iran found Cd concentrations in wheat exceeding FAO/WHO limits in fields irrigated with treated wastewater, highlighting the role of irrigation sources in Cd transfer to food crops63. Traditional bread baked on pebble beds or with fuel torches can further increase Cd levels through fuel and surface contamination64. Consistent with our findings, Kianpour et al.47 and Ghoreishy et al.41 reported cadmium levels in bread samples that exceeded FAO/WHO limits. Adebiyi et al.60 found Cd levels in bread samples ranging from 0.30 to 0.80 mg/kg, with the mean concentration in our study exceeding WHO limits. However, Khodayi et al.48 reported Cd levels below recommended values. Basaran (2022)49 found Cd concentrations in Turkish bread ranging from 0.0034 to 0.278 mg/kg, lower than our findings.

Human activities, particularly mining and metal industries, contribute to aluminum presence in the environment65. The alloys used in rotary ovens can contain iron, which may introduce aluminum into the bread. Increased temperatures lead to corrosion and migration of aluminum from the baking equipment66. Additionally, aluminum contamination may occur from fuel sources and food additives used in bread-making67. Case studies from Mashhad and Isfahan indicate that the alloys used in rotary ovens and baking trays—combined with high baking temperatures—facilitate Al migration into bread16,48. Additionally, industrial emissions from aluminum smelting facilities in central Iran have been shown to deposit fine Al-bearing particulates on agricultural fields, further contributing to crop contamination48.Similar to our results, Khodaei et al.48 in Isfahan reported an average Al concentration of 29.88 ± 8 mg/kg, exceeding FAO/WHO limits. Ghasemi et al.16 also found aluminum levels in Mashhad bread samples exceeding safety standards. A study by Wong et al.68 in Hong Kong found aluminum levels in steam-cooked bread and cakes ranging from 100 to 320 mg/kg, indicating that contamination sources are complex and difficult to quantify.

Mercury is one of the most toxic environmental metals and can enter the food chain through contaminated irrigation water69. The presence of Hg in bread may be linked to contaminated water or salt used in production70. In Iran, Hg contamination in wheat has been linked to the use of irrigation water sourced from rivers downstream of industrial discharges, as reported in studies of certain southern provinces. These sources, combined with Hg present in some rock salt used in bread making, can account for the Hg concentrations found in our samples70. Research on Hg levels in bread is limited; however, a study by Basaran49 in Turkey reported Hg levels ranging from < LOQ to 0.0009 mg/kg. The average Hg concentration in examined bread samples from Isfahan48 was estimated at 0.008 ± 0.01 mg/kg, lower than our findings.

Differences in this study’s results compared to others may stem from various factors, particularly the wheat used in bread production. In Iran, bread contamination can occur through sewage irrigation, indiscriminate pesticide and fertilizer use, and contamination during production processes41,61,62.

Health risk assessment

Bread is the most consumed food in Iran, making it crucial to determine the levels of PTEs and assess the health risks associated with PTEs contamination to protect consumer health. Among the studied PTEs, chromium and lead are particularly hazardous, with long-term exposure linked to an increased risk of certain cancers. Lead primarily affects the nervous system, and prolonged exposure can disrupt normal functioning, potentially leading to serious damage to the kidneys and brain. The body absorbs lead readily, and children are especially vulnerable as they absorb more lead than adults, posing significant developmental risks71,72. Long-term exposure to chromium, another heavy metal, can result in toxicity and various health issues, including allergic reactions, anemia, burns, and ulcers, particularly in the stomach and small intestine. It can also adversely affect sperm and male reproductive health, impacting multiple biological systems7.

The results indicate that the non-carcinogenic risk for chromium exceeds the threshold of 1 due to bread consumption among adults. In children, the THQ values for Cr and Fe through bread consumption also surpass 1, suggesting potential non-cancerous health effects in these groups. Furthermore, the calculated HI for all age groups through food consumption exceeds 1, indicating health risks associated with PTEs consumption, which are notably higher in children. Their vulnerability arises from higher intestinal absorption rates, lower effective excretion, and a greater “food intake to body weight” ratio, with estimates suggesting that children consume three times more food relative to their body mass compared to adults73,74.

A study by Ghoreishy et al.41 found that the hazard quotient often exceeded 1, aligning with our findings. Similarly, research by Khodayi et al. (2023)48 showed that the HI exceeded 1 for both children and adults, with children facing a 5.73 times higher risk of non-cancerous hazards. Ghanati et al. 75 reported an HI greater than 1 in both urban and rural areas, consistent with our research. However, Noori et al.76 found that all estimated values for non-carcinogenic risk remained within the safe range (HI < 1), which contrasts with our findings. In Tehran, Esfandiari et al.77 evaluated the risk of aluminum from bread, reporting an HI below 1, further highlighting inconsistencies with our results.

Woldetsadik et al.53 observed a risk index through bread consumption above 1, similar to our findings. Basaran et al.49 reported an HI exceeding 1 for all types of bread, consistent with this study. Kose et al.78 also indicated an HI related to bread consumption above 1, aligning with our results. Conversely, Alemu et al.79 found both the THQ and HI for the studied PTEs below 1, differing from our conclusions. This suggests that wheat and its derivatives are significant sources of PTEs contamination, warranting attention to the associated risks from high concentrations in consumers.

In this study, the carcinogenic risk was assessed for Cd and Pb in provinces A, B, D, and H, where these metals were detected in bread samples. Cd and Pb were not detected in samples from the other provinces studied; therefore, the results of the carcinogenic risk assessment cannot be generalized to the entire population of Iran. This regional limitation suggests that Cd and Pb contamination may be linked to localized sources, such as industrial activities, agricultural practices, or soil contamination in these provinces, necessitating targeted monitoring in these regions and further investigation to assess risks elsewhere in Iran. Based on this study’s findings and a comparison of carcinogenic risk values against the maximum acceptable risk proposed by the EPA, carcinogenic risks for Cd and Pb, assessed in four provinces, were moderate (10⁻⁴ < CR ≤ 10⁻⁶). Our results parallel those of Noori et al. 76, Khodayi et al.48, and Alemu et al.79, all of which exceeded permissible limits.

The analysis indicates that the concentration of PTEs in bread has a considerable impact on both carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk, while other factors such as body weight and per capita bread consumption have less influence. Similar findings have been reported by Sharafi et al.80, Wang et al.81,82, and Liu et al.83, reinforcing the notion that reducing PTEs contamination in cereals is critical for mitigating health risks associated with cereal consumption.

Limitation

This study provides a robust assessment of health risks from heavy metals in bread using Monte Carlo simulations, but it has limitations. Assigning zero to non-detected concentrations of Hg, Cd, Co, Pb, and Ni may underestimate risks, particularly for highly toxic metals like Cd and Pb. Alternative methods, such as using the limit of detection (LOD) or LOD/2, could provide more conservative estimates and should be considered in future studies to better capture potential risks from these metals. The limitation of carcinogenic risk calculations to provinces A, B, D, and H, where Cd and Pb were detected, restricts generalizability across Iran, as these metals were not detected in other provinces. This suggests regional variability in contamination sources, such as industrial or agricultural activities, requiring further investigation to assess risks in other regions.

Conclusion

This study provides a comprehensive evaluation of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in bread, a cornerstone of the Iranian diet, using a robust Monte Carlo simulation approach to assess associated health risks. The analysis of 248 bread samples from 11 provinces revealed significant contamination by PTEs, including iron (Fe), chromium (Cr), lead (Pb), aluminum (Al), cadmium (Cd), and mercury (Hg), with concentrations exceeding WHO/FAO safety thresholds. The results highlight significant non-carcinogenic and carcinogenic risks, particularly for children, who are more vulnerable due to higher absorption rates and greater food intake relative to body weight.

Notably, carcinogenic risk assessments for Cd and Pb were limited to four provinces due to their detection in these regions, indicating localized contamination sources such as industrial activities or agricultural practices. The absence of Cd and Pb in samples from other provinces restricts the generalizability of the CR results to the entire Iranian population. This regional variability suggests localized contamination sources, such as industrial activities or agricultural practices, which warrant targeted monitoring and further investigation. It is important to note that the carcinogenic risk findings for cadmium and lead are limited to the four provinces where these metals were detected in bread samples. Additionally, this study focused on Cd and Pb due to their detection rates and established carcinogenic classifications (IARC Group 1 and 2B, respectively). However, other carcinogenic metals, such as arsenic (As) and nickel (Ni), were not included in the CR assessment due to their low detection rates or absence in the samples. Literature suggests that these metals, if present, could contribute to cumulative carcinogenic risks. For instance, As (Group 1) and Ni (Group 2B) are known to pose significant cancer risks through dietary exposure. Future studies should expand the scope to include these metals for a more comprehensive risk evaluation.

Beyond identifying risks, this study emphasizes broader implications for food security and public health policy in Iran. Elevated contaminant levels in bread indicate systemic issues in the wheat supply chain that necessitate coordinated intervention. Continuous monitoring of wheat, flour, and bread emerges as a critical strategy for mitigating these risks, ensuring that safety measures adapt to increasing environmental pressures. To address the significant health risks posed by PTEs contamination in bread, several actionable mitigation measures can be implemented to enhance food safety in Iran. First, stricter soil and water testing protocols should be established to monitor and control PTEs levels in agricultural inputs. Regular testing of soils and irrigation water, particularly in regions with high industrial activity or historical pollution, can identify contamination hotspots and prevent the uptake of PTEs like Cd, Pb, and Cr by wheat crops. For instance, implementing mandatory testing for heavy metals in irrigation water and soils, as recommended by the FAO, could reduce contamination at the source. Second, transitioning to cleaner fuel sources for baking, such as natural gas or electric ovens, can minimize the introduction of PTEs like Cd and Zn from contaminated fuel torches or pebble beds used in traditional baking methods. Third, upgrading baking equipment to materials with lower leaching potential, such as food-grade stainless steel with minimal Cr and Fe content or ceramic-coated surfaces, can significantly reduce PTEs migration into bread. Additionally, enforcing stricter regulations on the use of phosphate fertilizers and sewage sludge in wheat farming, which are major sources of Cd and Pb, is critical. Adopting precision agriculture techniques, such as targeted fertilizer application, can further minimize PTEs accumulation in crops. Finally, establishing a national monitoring program for PTEs levels in wheat and bread, coupled with public awareness campaigns, can promote compliance with safety standards and inform consumers about safe consumption practices. These measures, if integrated into Iran’s food safety policies, can substantially reduce PTEs contamination risks and protect public health.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Pirhadi, M., Shariatifar, N., Bahmani, M. & Manouchehri, A. Heavy metals in wheat grain and its impact on human health: A mini-review. J. Chem. Health Risks. 12, 421–426 (2022).

Rahati, S., Hashemi, M., Orooji, A., Afshari, A. & Sany, S. B. T. Health risk assessments of heavy metals and trace elements exposure in the breast milk of lactating mothers in the Northeastern Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res., 1–15 (2024).

Asadi Touranlou, F. et al. Health risk assessment of exposure to heavy metals in wheat flour from Iran markets: application of Monte Carlo simulation approach. Biol. Trace Elem. Res., 1–11 (2024).

Asadi Touranlou, F., Raeesi, A. & Rezaei, M. Health risk assessment of the concentration of heavy metals in pistacia species: a global systematic review. Nutr. Food Sci. 54, 468–482 (2024).

Pirhadi, M. et al. Potential toxic elements (PTEs) concentration in wheat and flour products in iran: A probabilistic risk assessment. Heliyon 8 (2022).

Kazemi Moghaddam, V. et al. Heavy metal contaminated soil, water, and vegetables in Northeastern iran: potential health risk factors. J. Environ. Health Sci. Eng. 20, 65–77 (2022).

Hossini, H. et al. A comprehensive review on human health effects of chromium: insights on induced toxicity. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 70686–70705 (2022).

Marufi, N., Conti, G. O., Ahmadinejad, P., Ferrante, M. & Mohammadi, A. A. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic human health risk assessments of heavy metals contamination in drinking water supplies in iran: a systematic review. Rev. Environ. Health. 39, 91–100 (2024).

Lyon, F. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. World health organization, International agency for research on cancer. (2014).

Rokni, L. et al. Effect of persistent organic pollutants on human health in South korea: A review of the reported diseases. Sustainability 15, 10851 (2023).

Kiani, B. et al. Association between heavy metals and colon cancer: an ecological study based on geographical information systems in North-Eastern Iran. BMC Cancer. 21, 1–12 (2021).

Fairbrother, A., Wenstel, R., Sappington, K. & Wood, W. Framework for metals risk assessment. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 68, 145–227 (2007).

Kamalabadi, M., Kamankesh, M., Mohammadi, A., Hadian, Z. & Ferdowsi, R. Contamination and daily intake of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in Iranian bread samples. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. (2019).

Collar, C. Role of bread on nutrition and health worldwide. Bread its Fortification Nutritional Healthy Benefits, 26–52 (2015).

Abdel-Rahman, G. N. E. Heavy metals, definition, sources of food contamination, incidence, impacts and remediation: A literature review with recent updates. Egypt. J. Chem. 65, 419–437 (2022).

Ghasemi, S. et al. Effect of baking methods types on residues of heavy metals in the different breads produced with wheat flour in iran: A case study of Mashhad. J. Chem. Health Risks 12 (2022).

Moyo, N. A. & Rapatsa, M. M. Trace metal contamination and risk assessment of an urban river in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Bull. Environ Contam. Toxicol. 102, 492–497 (2019).

Douvris, C., Trey, V., Bussan, D., Bartzas, G. & Thomas, R. How ICP-OES changed the face of trace element analysis: review of the global application landscape. Sci. Total Environ. 167242 (2023).

Olesik, J. ICP-OES capabilities, developments, limitations, and any potential challengers? (2020).

Alidadi, H. et al. Health risk assessments of arsenic and toxic heavy metal exposure in drinking water in Northeast Iran. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 24, 1–17 (2019).

Javedan, G. et al. Concentration of potentially toxic elements in black tea imported to iran: a potential risk assessment study. (2022).

EPA, U. Concepts, methods and data sources for cumulative health risk assessment of multiple chemicals, exposures and effects: A resource document. US Environmental Protection Agency, National Center for Environmental Assessment (2007).

Ghaffari, H. R. et al. The concentration of potentially hazardous elements (PHEs) in drinking water and non-carcinogenic risk assessment: A case study in Bandar Abbas, Iran. Environ. Res. 201, 111567 (2021).

Asadi Touranlou, F., Hashemi, M., Ghavami, V. & Tavakoly Sany, S. B. Concentration of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in bread and health risk assessment across the globe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 23, e13411 (2024).

Moya, J. et al. Exposure factors handbook: 2011 edition. US Environ. Prot. Agency (2011).

Kamari, Z. et al. Assessing the risk of carcinogenesis caused by exposure to heavy metals through the consumption of drinking water (A case study of Bandar Abbas drinking water). J. Prev. Med. 9, 90–101 (2022).

Pirsaheb, M., Hadei, M. & Sharafi, K. Human health risk assessment by Monte Carlo simulation method for heavy metals of commonly consumed cereals in Iran-Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis. J. Food Compos. Anal. 96, 103697 (2021).

Tajdar-Oranj, B. et al. The concentration of heavy metals in noodle samples from iran’s market: probabilistic health risk assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 25, 30928–30937 (2018).

Epa, U. S. Exposure factors handbook. Office Res. Dev. Wash. DC. 20460, 2–6 (2011).

Shetty, B. R., Pai, B. J., Salmataj, S. & Naik, N. Assessment of carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk indices of heavy metal exposure in different age groups using Monte Carlo simulation approach. Sci. Rep. 14, 30319 (2024).

Eid, M. H. et al. New approach into human health risk assessment associated with heavy metals in surface water and groundwater using Monte Carlo method. Sci. Rep. 14, 1008 (2024).

Khazaei, S., Talebi Ghane, E., Bashirian, S. & Mehri, F. The concentration of potentially toxic elements (PTEs) in fruit juices: a global systematic review, meta-analysis and probabilistic health risk assessment. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 103, 1259–1271 (2023).

Pirhadi, M. et al. EThe effect of the milling pro-cess on the level of aluminum contamination in wheat and flour of Alborz Province. Plant. Biotechnol. Persa. 2, 24–27 (2020).

Mohammadpour, A. et al. Trace elements human health risk assessment by Monte Carlo probabilistic method in drinking water of Shiraz, Iran. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 20, 3775–3788 (2023).

Izadi Najafabadi, L., Hamdami, N., Le-Bail, A., Monteau, J. Y. & Keramat, J. Impact of baking bed and baking temperature on Staling of Sangak bread. J. Agricultural Sci. Technol. 17, 375–386 (2015).

Karizaki, V. M. Ethnic and traditional Iranian breads: different types, and historical and cultural aspects. J. Ethnic Foods. 4, 8–14 (2017).

Baran, A., Wieczorek, J., Mazurek, R. & Urbański, K. Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A. Potential ecological risk assessment and predicting zinc accumulation in soils. Environ. Geochem. Health. 40, 435–450 (2018).

Masjed-Suleiman Branch, I. Metals distribution in topsoils around industrial town of Ahwaz II, Ahwaz, Iran. J. Appl. Sci. 9, 1121–1127 (2009).

Jawad, I. & Allafaji, S. H. The levels of trace metals contaminants in wheat grains, flours and breads in Iraq. Aust J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 6, 88–92 (2012).

Tourchi, M., Azizinezhad, S. E. Y. E. D. A. I. N. A. S. & Nematollahi, F. R. Assessing the effect of baking methods on the levels of heavy metals in Iranian traditional breads. (2017).

Ghoreishy, F., Salehi, M. & Fallahzade, J. Cadmium and lead in rice grains and wheat breads in Isfahan (Iran) and human health risk assessment. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assessment: Int. J. 25, 924–934 (2019).

Faraji, M., Alizadeh, I., Conti, G. O. & Mohammadi, A. Investigation of health and ecological risk attributed to the soil heavy metals in iran: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 857, 158925 (2023).

Esmaeili, A., Moore, F., Keshavarzi, B., Jaafarzadeh, N. & Kermani, M. A geochemical survey of heavy metals in agricultural and background soils of the Isfahan industrial zone. Iran. Catena. 121, 88–98 (2014).

Lebbos, N. et al. Lebanese population exposure to trace elements via white bread consumption. Foods 8, 574 (2019).

Bossou, T., Dabade, D. S., Bello, O. D. & Dossou, J. Risk assessment of lead in wheat flour bread consumed in Benin. J. Appl. Biosci. 164, 17056–17064 (2021).

ÖLMEZ, E., GÖKMEŞE, E., ERGUN, Ü. & GOKMEŞE, F. Monitoring of lead and some heavy metals in wheat flour of corum province, turkey: an air quality comparison. Hittite J. Sci. Eng. 10, 49–56 (2023).

Kianpoor, S. & Sobhanardakani, S. Evaluation of Zn, Pb, Cd and Cu concentrations in wheat and bread consumed in Hamedan city. (2017).

Khodaei, S. M., Esfandiari, Z., Sami, M. & Ahmadi, A. Determination of metal (oids) in different traditional flat breads distributed in Isfahan city, iran: health risk assessment study by Latin hypercube sampling. Toxicol. Rep. 10, 382–388 (2023).

Basaran, B. Comparison of heavy metal levels and health risk assessment of different bread types marketed in Turkey. J. Food Compos. Anal. 108, 104443 (2022).

Doe, E., Awua, A., Gyamfi, O. & Bentil, N. Levels of selected heavy metals in wheat flour on the Ghanaian market: a determination by atomic absorption spectrometry. Am. J. Appl. Chem. 1, 17–21 (2013).

Shiralipour, R., Jahangiri, A. & Baaghdezfooli, M. Determination of iron, zinc and copper in fortified wheat flour consumed in ahvaz. (2017).

Zafarzadeh, A. et al. Assessment of the health risk and geo-accumulation of toxic metals in agricultural soil and wheat, Northern Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 750 (2021).

Woldetsadik, D. et al. Contents of metal (loid) s in a traditional Ethiopian flat bread (Injera), dietary intake, and health risk assessment in addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 198, 732–743 (2020).

Ozbek, N. & Akman, S. Method development for the determination of calcium, copper, magnesium, manganese, iron, potassium, phosphorus and zinc in different types of breads by microwave induced plasma-atomic emission spectrometry. Food Chem. 200, 245–248 (2016).

Feyzi, Y. et al. Metals that are important for food safety control of bread product. Adv. Biores. 8 (2017).

Jacobs, J. A. & Testa, S. M. Overview of chromium (VI) in the environment: background and history. Chromium (VI) handbook, 1–21 (2005).

Gupta, N. et al. Trace elements in soil-vegetables interface: translocation, bioaccumulation, toxicity and amelioration-a review. Sci. Total Environ. 651, 2927–2942 (2019).

Mathebula, M. W., Mandiwana, K. & Panichev, N. Speciation of chromium in bread and breakfast cereals. Food Chem. 217, 655–659 (2017).

Taghavi, M. et al. Ecological risk assessment of Cd, As, Cr, and Pb metals in farmed wheat in the vicinity of an industrial park. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 103, 3196–3211 (2023).

Adebiyi, F. M., Ore, O. T. & Ojile, F. J. Evaluation of potentially toxic elements and bromate levels in bread commonly consumed in Nigeria for human health risk assessment. J. Trace Elem. Minerals. 2, 100016 (2022).

Huang, Y., Mubeen, S., Yang, Z. & Wang, J. In Theories and Methods for Minimizing Cadmium Pollution in Crops: Case Studies on Water Spinach 1–30 (Springer, 2022).

Saatloo, N. V. et al. Quantification and human health risk assessment of cadmium and lead in wheat flour on the Iranian market by atomic absorption spectrometry. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 8, 100438 (2023).

Azhdarpoor, A., Moeini, Z., Ranjbar, F., Samaei, M. & Hashemi, H. Risk assessment of heavy metals in soil and simultaneous monitoring in wheat irrigated with groundwater and treated wastewater and its long-term effects for residents of adjacent regions. Environ. Science: Water Res. Technol. 10, 1135–1146 (2024).

Tavakoli, H. Familiarity of different methods of standard bread baking. Natl. Project 76–77 (2011).

Aguilar, F. et al. Safety of aluminium from dietary intake scientific opinion of the panel on food additives, flavourings, processing aids and food contact materials (AFC). EFSA J. 754, 1–34 (2008).

Jekle, M. et al. Aluminium leaching from baking tray materials into surface-alkalized baked products. Cereal Technol. 3, 127–135 (2016).

Yang, M. et al. Dietary exposure to aluminium and health risk assessment in the residents of Shenzhen, China. PLoS One. 9, e89715 (2014).

Wong, W. W., Chung, S. W., Kwong, K., Yin Ho, Y. & Xiao, Y. Dietary exposure to aluminium of the Hong Kong population. Food Addit. Contam. 27, 457–463 (2010).

Gautam, P. K., Gautam, R. K., Banerjee, S., Chattopadhyaya, M. & Pandey, J. Heavy metals in the environment: fate, transport, toxicity and remediation technologies. Nova Sci. Publishers. 60, 101–130 (2016).

Hashemi, M., Salehi, T., Aminzare, M., Raeisi, M. & Afshari, A. Contamination of toxic heavy metals in various foods in iran: a review. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 9, 1692–1697 (2017).

Collin, M. S. et al. Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects on human: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 7, 100094 (2022).

Nag, R. & Cummins, E. Human health risk assessment of lead (Pb) through the environmental-food pathway. Sci. Total Environ. 810, 151168 (2022).

Eslami, H. et al. Potentially toxic metal concentration, Spatial distribution, and health risk assessment in drinking groundwater resources of Southeast Iran. Geosci. Front. 13, 101276 (2022).

Bair, E. C. A narrative review of toxic heavy metal content of infant and toddler foods and evaluation of united States policy. Front. Nutr. 9, 919913 (2022).

Ghanati, K., Zayeri, F. & Hosseini, H. Potential health risk assessment of different heavy metals in wheat products. Iran. J. Pharm. Research: IJPR. 18, 2093 (2019).

Noori, S. M. A. et al. Measurement of the toxic trace elements in commercial wheat flours: potential health risk via dietary intake. J. Chem. Health Risks 12 (2022).

Esfahani, T. A., Amoli, J. S. & Daneshmand, M. Measurement of heavy metals in bread with an emphasis on the risk assessment of aluminum. J. Nutr. Fasting & Health 9 (2021).

Köse, B. G., Pekmezci, H. & Basaran, B. Bread consumption-induced heavy metal exposures and health risk assessment of pregnant women: Turkey. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 202, 473–480 (2024).

Alemu, W. D., Bulta, A. L., Doda, M. B. & Kanido, C. K. Levels of selected essential and non-essential metals in wheat (Triticum aestivum) flour in Ethiopia. J. Nutritional Sci. 11, e72 (2022).

Sharafi, K. et al. Human health risk assessment for some toxic metals in widely consumed rice brands (domestic and imported) in Tehran, iran: uncertainty and sensitivity analysis. Food Chem. 277, 145–155 (2019).

Wang, Y. et al. Health risk and Temporal trend of dietary potentially toxic elements exposure in the residents of the Shenzhen metropolis, China, between 2005 and 2017: a risk assessment based on probabilistic Estimation. Environ. Geochem. Health. 43, 113–126 (2021).

Wang, Y. et al. Deterministic and probabilistic health risk assessment of toxic metals in the daily diets of residents in industrial regions of Northern Ningxia, China. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 201, 4334–4348 (2023).

Liu, P., Zhang, Y., Feng, N., Zhu, M. & Tian, J. Potentially toxic element (PTE) levels in maize, soil, and irrigation water and health risks through maize consumption in Northern Ningxia, China. BMC Public. Health. 20, 1–13 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the vice president of research at the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, and the chiefs of the health centers affiliated with the university. We would also like to extend our appreciation to all participants and data collectors.

Funding

This study was funded by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Deputy of Research, Grant No. 971851.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.A & S.B.T: writing original draft, review, and editing. M.M: review and revise manuscript. S.Kh and A.A: conceptualization, analysis, and review and editing. M.H: supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences (#IR.MUMS.MEDICAL.REC.1398.623) after obtaining the required permit for the research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Asadi Touranlou, F., Tavakoly Sany, S., Ghayour Mobarhan, M. et al. Health risk assessment of potentially toxic elements in bread from Iranian markets using Monte Carlo simulation. Sci Rep 15, 38315 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22207-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22207-8