Abstract

Accurate survival prediction is essential for guiding follow-up strategies in patients with cT1b renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Traditional AJCC TNM staging systems provide limited prognostic accuracy. Data from the SEER database were used, which included 22,426 patients with cT1b RCC who underwent surgical resection. The data were randomized into training and validation sets in a 7:3 ratioen, suring comparability using standardized mean differences (SMD < 0.1). A random survival forest (RSF) model was developed and compared with support vector machine (SVM) and extreme gradient boosting accelerated failure time (XGB-AFT) models. Model performance was assessed using AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and calibration, with 1000 bootstrap resamples. Shapley additive explanation (SHAP) values were calculated to explore variable importance and enhance interpretability. The RSF model achieved the highest discrimination for predicting 5- and 10-year overall survival (AUC: 0.746 and 0.742), outperforming AJCC TNM (AUC: 0.663 and 0.627), SVM, and XGB-AFT. The model demonstrated good calibration and clinical net benefit. SHAP analysis identified age, tumor size, grade, and marital status as the top contributors to survival prediction. The RSF model significantly improves survival prediction over conventional staging systems and other machine learning methods, with enhanced interpretability through SHAP analysis. While the lack of external validation and the use of overall survival (including non-cancer deaths) are limitations, the model shows strong potential for clinical implementation and may facilitate individualized follow-up planning. Future studies should validate the model prospectively and explore integration into clinical decision support systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common renal malignancy, accounting for over 85% of all kidney cancer cases1. With the widespread use of imaging techniques, an increasing number of patients are being diagnosed at an early stage, particularly in cases of localized renal cancer at the cT1 stage2,3. The recent emergence of targeted and immunological therapies has provided new hope for RCC treatment; however, surgery remains the first-line approach4,5,6. Radical nephrectomy (RN) and partial nephrectomy (PN) are widely recognized as the primary and effective treatment options for these patients7.

As laparoscopic and robotic surgical techniques continue to mature and clinical experience grows, the indications for PN are gradually expanding in clinical practice8,9. Numerous studies have compared the prognostic outcomes of these two surgical approaches across different populations. The results suggest that PN maximizes renal function preservation while ensuring tumor control in certain patients, thereby improving long-term survival10,11,12. However, most studies have focused on the selection of surgical modality, while research on individual differences in postoperative overall survival and predictive models for patients undergoing surgical resection remains limited.

Although most cT1b stage patients who underwent surgery had a better prognosis13, their postoperative overall survival (OS) still exhibited significant individual variability, indicating that risk assessment based solely on TNM staging may have limitations14,15. In recent years, machine learning, a key branch of artificial intelligence, has demonstrated significant potential in medicine, particularly in tumor prognosis prediction16. Machine learning has demonstrated strong predictive performance in neuroscience datasets, highlighting its potential to extract clinically meaningful patterns from large and heterogeneous sources of data17,18. Within urology, ML approaches have been applied to risk stratification and outcome prediction, providing novel tools to complement traditional staging systems19. Furthermore, ML has been increasingly utilized in oncology to improve prognostic modeling and survival prediction, underscoring its relevance across different cancer types20.

This study focuses on patients with stage cT1b RCC who have undergone surgical resection and develops a machine learning model by integrating relevant feature variables from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. The aim is to predict patients’ overall postoperative survival and identify the best-performing models for clinical application.

Methods

Study population

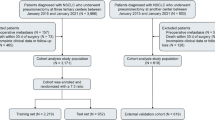

We retrieved data from SEER Research Plus Data, 17 Registries, Nov 2023 Sub (2000–2021) using SEER*Stat software (Beta 9.0.31). By condition setting, we collected data related to patients with renal cell carcinoma whose tumor size was > 40 mm but ≤ 70 mm between 2004 and 2019 (Clinical T staging). Finally, 22,426 patients with RCC at stage cT1b were included in this study. We randomly split the dataset into a training set and a validation set at a 7:3 ratio. This proportion is commonly used in machine learning applications to ensure sufficient data for model training while retaining an adequate portion for performance evaluation and preventing overfitting. 16 variables were initially included in this study, including age, sex, race, marital status, urban–rural residence, household income, laterality, tumor size, type of surgery, pathological grading, pT, pN, pM, histological subtype, number of lymph nodes examined, and number of positive lymph nodes. The detailed data extraction and processing flow of this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) diagnosis of renal cancer by site code ICD-O-3/WHO 2008 (kidney and renal pelvis); (2) Primary Site labeled (C64.9) identifying the lesion as “renal”; (3) A complete RN (codes 40, 50, 70, 80) or PN (code 30) surgical record is available; (4) Confirmation of positive histology for complete pathology; (5) Histologic subtypes consistent with renal cell carcinoma, including clear cell (code 8310), smoky cell (codes 8270, 8317), stromal cell (codes 8050, 8260), and not otherwise specified RCC (nosRCC) (codes 8010, 8140, 8312).

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) tumor size non-cT1b or unknown; (2) unclear pathologic grading; (3) presence of multiple concurrent tumors that were not of a single primary tumor; (4) unknown pathologic staging; (5) histologic subtypes that did not fit into the category of renal cell carcinoma; (6) patients who died within 1 month; (7) follow-up data that were incomplete or estimated; (8) age < 18 years; (9) race, marital status, laterality, urban–rural residence, and household income were unknown.

Variable consolidation and recoding

Due to the different years of the SEER database, some variables were coded inconsistently. To ensure the rigor of the study, we hereby integrate and recode the variables in this study based on previous studies and existing clinical experience. First, since our data span the years 2004–2019, three versions of the staging criteria exist. Therefore, we recorded 2004–2015 (6th edition) and 2016–2017 (7th edition) to uniformly use the American Joint Committee on Cancer(AJCC) 8th edition tumor staging. Second, we used ‘Regional_nodes_positive_1988’ to correct NX and N2 to avoid the deletion of available variables due to recording errors. Direct deletion of Mx, caused by the limitations of early imaging techniques, may lead to underestimation of true stage IV cases. Therefore, we also adjusted for Mx using the CS locus. For N2 and M2, which remain after correction, RCC does not include these stages. We therefore regarded them as recording bias and reclassified them as N1 and M1. The number of such cases was extremely low (N2: 199 cases, M2: 147 cases, each < 0.1% of the cohort), and we therefore believe that this recoding has a negligible influence on the overall findings. Similarly, NA, Tx, Nx, and Mx, which remained after correction, we deleted the relevant variables because they were not reliable. In cycles 2016–2017, partial clinical staging of N was reported. Based on clinical practice, lymph node dissection is generally not required for patients with cT1b RCC. Therefore, we utilized ‘Rx Summ_Scope_Reg_LN_Sur’ for identification. A true pN0 was assumed if no lymph node clearance was performed, and a pN0 was also confirmed if no positive lymph nodes were present after clearance. In addition, marital and Household income were recorded accordingly for integration. Due to limitations of the SEER database, surgical techniques such as open, laparoscopic, or robotic-assisted approaches were not distinguishable. Therefore, we analyzed surgical type based on partial versus radical nephrectomy only.

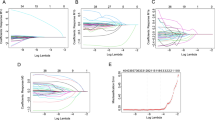

Screening of characteristic variables

Spearman’s method was used to analyze the correlation between the 16 variables initially included in the study, which is presented in the form of a correlation heat map. A correlation coefficient with an absolute value less than 0.5 indicates a weak correlation, + 1 indicates a perfect positive correlation, and − 1 indicates a perfect negative correlation. For subsequent machine learning model construction, we used the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression analysis, Boruta’s algorithm, and univariate Cox’s analysis to screen the feature variables. Lasso regression analysis can assign penalty coefficients to the above variables, which can effectively reduce the possibility of overfitting. We used the optimal lambda value (1se), set the number 100, and took a tenfold cross-validation. Boruta is based on the Random Forest algorithm, which is evaluated by assigning a randomly generated true Z-score to the feature and a corresponding Z-score to the “shadow”; if the true Z-score is greater than the maximum Z-score across multiple test samples, then this variable will be filtered out. Variables with P < 0.05 were considered to significantly influence the outcome and were screened out in the conventional one-way COX analysis. The same variables obtained through the three methods described above were included in a multifactor COX analysis to determine the final model. Finally, the screened characteristic variables were examined using the multiple covariance screening method.

Description of machine learning algorithms

Machine learning methods have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in handling high-dimensional, nonlinear, and heterogeneous data across diverse biomedical fields17,21. These findings highlight the generalizability and robustness of DL techniques in complex prediction tasks, thereby supporting their application in prognostic modeling for clinical oncology. XGBoost-Accelerated Failure Time (XGB-AFT) Survival is based on the combination of the XGBoost framework and the AFT model. XGBoost optimizes the loss function of AFT by gradient-boosting trees while using regularization to prevent overfitting22. Support Vector Machine (SVM) Survival Analysis is an extension of SVM, modeled by Ranking Loss or survival time quantile regression23. Hinge Loss is commonly used to maximize the interval between event times24. Random Forest Survival (RSF) is an extension to survival analysis based on RF, where nodes are partitioned by Cox partial likelihood or log-rank statistics25. Survival curves are generated for each tree, and the results from multiple trees are eventually summarized. The risk of overfitting can be reduced by feature subset selection.

Machine learning model construction and validation

The key risk factors affecting the overall survival of patients with cT1b renal cell carcinoma were identified by applying the Botuta algorithm, LASSO regression, and the univariate COX, and their 11 intersections were selected through a Venn diagram. The screened characteristic variables were tested using the multicollinearity screening method. A variance inflation factor (VIF) ≤ 5 was considered to be the absence of multicollinearity between variables.

OS was the endpoint of interest in this study. It was calculated from diagnosis to date of all-cause death or last follow-up. The number of feature variables included in the machine learning predictive model was 11, and the number of positive events in this study was much greater than 10 times the number of feature variables, consistent with following the Harrell guidelines26. Three machine learning survival algorithms, XGB-AFT, RSF, and SVM, were used to build a prediction model for overall survival. The training set was used to select the optimal model, and the test set was used for model testing. The best models were evaluated considering specific follow-up 5-year OS and 10-year OS, including time-specific area under the operating curve (AUC), specificity, sensitivity, negative predictive value (NPV), and positive predictive value (PPV). Decision Curve Analysis (DCA), the Net Reclassification Improvement Index (NRI), and the Integrated Discriminant Improvement Index (IDI) were used to assess the clinical benefit and utility of the optimal model compared to tumor staging based on AJCC criteria alone.

The metric NRI is more widely used to compare the accuracy of two predictive models, and IDI reflects the change in the gap between the predictive probabilities of the two models, with an improvement in NRI or IDI > 0 indicating that the new model has improved predictive ability over the old model27,28. The best model was compared with risk stratification for tumor staging based on AJCC criteria using the Kaplan–Meier method. Thresholds for risk stratification were selected using optimal thresholds.

Statistical analysis

Student t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was utilized to compare quantitative data, while Fisher’s exact test or chi-square test was used to compare qualitative data. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables are expressed as total (n) and percentage (%).To assess baseline balance between the training and test sets, we reported not only conventional p-values but also standardised mean differences (SMD). SMD < 0.1 was generally considered indicative of good balance29. Statistical analyses for this study were performed using Python (version 3.9.12), R software (version 4.4.1)30, and DecisionLnnc1.0 software31. Statistical significance was determined by two-tailed p-values less than 0.05.

Results

Basic characteristics of the study population

A total of 22,426 cases of cT1b renal cell carcinoma after undergoing surgical resection were enrolled and randomized into a training and validation cohort in a 7:3 ratio. It should be noted that age and T stage achieved statistical significance. However, the SMD for all variables in both the training and test sets was less than 0.1, indicating baseline balance29. Consequently, we consider no significant differences in demographic or clinical characteristics to have been observed between the training and test cohorts. Table 1 demonstrates the baseline characteristics of this study.

Correlation analysis and variable screening

Correlations between the 16 variables initially included in the study were analyzed using the Spellman method (Fig. 2A). Univariate Cox regression analysis revealed 12 variables significantly associated with OS (Table 2). In the LASSO regression, a total of 11 variables were identified as significant influences on OS by setting the caliper value to − 3.798, a value of λ at which a total of 11 variables were identified as significant influences on OS (Fig. 2B, C). Boruta’s algorithm showed the Z-score of each variable, picking out the most relevant features to OS (Fig. 2D). The intersection of the 3 methods was taken by plotting a Wayne diagram, resulting in 11 significant feature variables (Fig. 2E). Subsequently, we included these variables in a multivariate COX regression analysis to observe OS under the influence of follow-up time. The results showed that age, tumor size, marital status, household income, type of surgery, pathological grading, T, N, M, histological subtype, and number of positive lymph nodes emerged as significant independent risk factors affecting OS after surgical resection of cT1b stage RCC patients. To further ensure the stability needed for subsequent modeling, we performed a multicollinearity analysis. The results showed that there was no significant multicollinearity among the screened characteristic variables (Table 3).

Correlation of feature variables and feature selection process in machine learning survival prediction models. (A) Heat map of the Spearman correlation matrix of the characteristic variables. The color shade indicates the strength of the correlation. The size of the circle indicates the strength of the correlation. The asterisk indicates the significance level of the correlation. (B) LASSO regression paths show the coefficients of the variables at different values of the regularization parameter (λ). (C) Cross-validation error map for selecting the optimal λ in LASSO. The vertical dashed line indicates the optimal λ for realizing the cross-validation error. (D) Importance of variables based on Boruta’s algorithm, where attributes are categorized as “confirmed” (red) and “rejected” (brown). (E) Venn diagrams compare the variables selected by the three different methods, showing the overlap of the selected variables.

Building and evaluating three machine learning models for survival analysis

We use 11 features identified through screening as independent factors and take three machine learning algorithms for survival analysis, SVM, XGB-AFT, and RSF, to fit the model. To select the best model, AUC, Best Threshold, Specificity, Sensitivity, NPV, and PPV of the three machine learning algorithm models were generated using the 1000 Bootstrap method (Table 4). The results show that SVM has poor metrics and is not recommended. The RSF model has the highest AUC (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating strong overall discriminative ability. NPV was significantly better than other models (0.910 for 5-year OS and 0.856 for 10-year OS) and reliably predicted negative results. Specificity and sensitivity were well-balanced (no extreme values). Therefore, the RSF model was considered the best model in this study. Subsequently, the calibration curves of the RSF model in the validation set (Supplementary Fig. 2) were analyzed and aligned with the vicinity of the 45° diagonal, indicating its excellent calibration performance.

Predictive effect and clinical value of the RSF model compared to tumor staging based on AJCC criteria

Figure 3 shows the predictive effect of OS assessed by the RSF model and tumor staging based on AJCC criteria alone. The results showed that the predictive effect of the RSF model was significantly superior. Changes in NRI and IDI were used to compare the accuracy between the RSF model and tumor staging based on AJCC criteria alone (Supplementary Table 1). When RSF was used in the training set, the NRI for 5- and 10-year OS was 0.269 (95% CI = 0.249–0.293) and 0.331 (95% CI = 0.306–0.351), respectively, and the IDI values for 5- and 10-year OS were 0.066 (95% CI = 0.058–0.075) and 0.126 (95% CI = 0.115–0.138). These results were validated in the validation cohort, suggesting that RSF predicts prognosis more accurately than tumor staging based on AJCC criteria.

Model effects of RSF and AJCC criteria-based tumor staging in predicting 5-year OS and 10-year OS after surgical resection in patients with cT1b stage RCC. The subject work characteristics (ROC) curves for the training and test sets illustrate the discriminative power of the two predictive models and show the area under the curve (AUC) values for the ROC curves of the two models (A–D). Calibration curves for the training and test sets illustrate the accuracy of the predictive ability of the two models (E–H).

Figure 4 shows the clinical benefits of RSF and tumor staging alone based on AJCC criteria for assessing OS. The results of the DCA curves show (Fig. 4A–D) that RSF outperforms the net gain obtained from tumor staging based on AJCC criteria for no treatment regimen as well as for all patient treatment regimens and almost all threshold probabilities, for both the training and test sets. Thus, RSF was able to better predict 5-year OS and 10-year OS after surgical resection in patients with cT1b stage RCC. Furthermore, the visualization results of NRI and IDI clearly showed that the RSF model gained a large portion of improvement (Fig. 4E–H).

Clinical benefit and model-improving ability of RSF and AJCC criteria-based tumor staging in predicting 5-year OS and 10-year OS after surgical resection in patients with cT1b stage RCC. The DCA curves show the net benefit of each model at various threshold probabilities, comparing them to the “Treat All” and “Treat None” strategies, indicating their potential clinical utility (A–D). The maple leaf plot demonstrates the improvement in the predictive power of RSF relative to tumor staging based on AJCC criteria, with red representing improvement (E–H).

RSF model and risk stratification for tumor staging based on AJCC criteria

The optimal model RSF, as well as the AJCC criteria-based tumor staging, yielded risk scores regarding their respective OS, and we stratified the OS risk scores using the optimal cutoff value to obtain a low-risk group and a high-risk group. The Kaplan–Meier curves showed a large differentiation between the two risk groups, exceeding the AJCC criteria-based tumor staging’s ability to predict, in both the training and the validation cohorts, the OS (Supplementary Fig. 3).

RSF model interpretability

To improve clinical interpretability of the RSF model, we applied Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) analysis to quantify the contribution of each predictor. The SHAP summary plot (Supplementary Fig. 4) shows that Age, pM, pT, and pN had the largest influence on survival prediction, consistent with established clinical knowledge. Other factors, such as the type of surgery and household income, also contributed, but to a lesser extent. These findings provide additional transparency to the RSF model and reinforce its clinical plausibility.

Temporal subgroup analysis of the RSF model

To examine whether our model was robust across different TNM staging versions and periods, we performed a temporal subgroup analysis by stratifying the cohort into 2004–2015 and 2016–2019 groups. The RSF model was retrained within each subgroup using the same 11 selected variables.

As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5, the model yielded comparable predictive performance in both subgroups, with AUCs of 0.743 and 0.742 in the earlier group and 0.745 and 0.746 in the later group for predicting 5-year and 10-year OS, respectively. Although PPV was lower in the 2016–2019 group, this is likely due to the shorter follow-up and lower event rate. NPV remained high (> 0.95), and overall discrimination was stable (Supplementary Table 2). These results support the temporal robustness and generalizability of the RSF model.

Discussion

As early detection of renal tumors increases, especially for cT1b stage RCC, surgical resection remains the cornerstone of treatment, whether through RN or PN32,33,34. As highlighted in previous studies, conventional risk stratification methods based solely on TNM staging may not fully capture patient-specific variables in RCC35,36. Additionally, the prognosis of patients with cT1b RCC after surgical treatment is generally favorable, but highly heterogeneous37,38. Previous studies report that the 5-year OS rate for patients with cT1b RCC undergoing nephrectomy ranges from 80 to 90%, depending on various clinicopathologic factors, including tumor size, grade, histologic subtype, and patient comorbidities39,40. Although PN is increasingly preferred for better renal function preservation and comparable oncologic outcomes, several studies suggest that PN may not always lead to better OS in cT1b tumors, particularly in elderly or high-risk patients41,42,43. These unresolved clinical dilemmas highlight the need for better risk stratification tools that go beyond tumor staging to incorporate patient-specific factors. Importantly, our study differs from many previous studies that primarily focused on comparing surgical approaches (PN vs. RN)44. Instead, we focus on the survival heterogeneity in patients who have already undergone surgery and highlight the current clinical need for accurate post-treatment prognostic assessment tools.

In this study, we developed and validated machine learning-based models to predict OS after surgical resection in patients with cT1b stage RCC using a large population-based dataset. To identify the most critical risk factors, univariate Cox regression, LASSO regression, and the Boruta algorithm were applied, with Venn diagrams used to obtain common results. The results showed that age, tumor size, marital status, household income, type of surgery, pathological grading, T, N, M, histological subtype, and number of positive lymph nodes emerged as significant independent risk factors affecting OS after surgical resection of cT1b stage RCC patients. These variables reflect not only tumor-related biological behaviors but also social determinants of health, emphasizing the complex and multifactorial nature of patients’ postoperative prognosis. It suggests that clinicians should take care to document these metrics to comprehensively assess OS after surgical resection in patients with cT1b stage RCC. Subsequently, we utilized these characteristic variables to construct predictive models using three machine learning algorithms. By comprehensively evaluating the performance of the models, we identified RSF as the optimal model. On this basis, we further compared with the AJCC standard tumor staging for predicting OS, confirming that our model, constructed by incorporating the above variables, has improvement and good clinical decision-making ability, increasing the credibility of the study results.

In the present study, the RSF model yielded an AUC of 0.746 and 0.742 for predicting 5- and 10-year OS, respectively. These values indicate moderate discrimination, comparable to previous studies applying machine learning for survival prediction in renal cell carcinoma, which typically reported AUC ranging from 0.70 to 0.80 45,46,47. Although such performance may appear limited for direct clinical decision-making, our model consistently outperformed the AJCC TNM stage across multiple evaluation metrics, including NRI, IDI, and decision curve analysis, suggesting added clinical utility in risk stratification. To further enhance predictive accuracy, future models could integrate additional clinical variables such as comorbidity indices, laboratory biomarkers, and perioperative parameters, which were not available in SEER48. Moreover, ensemble approaches or deep learning models may capture nonlinear interactions more effectively49. Finally, external validation using contemporary multicenter cohorts and prospective data collection will be crucial for improving generalizability and ensuring clinical applicability50,51.

Although the RSF model demonstrates markedly superior discriminatory power compared to traditional staging systems, its routine clinical implementation faces several challenges. Firstly, the model’s complex structure demands significant computational resources, rendering its deployment impractical in all clinical settings. Consequently, its application is best facilitated through user-friendly online calculators or clinical decision support tools integrated with electronic health record systems52. Secondly, although we enhanced the model’s interpretability through variable importance and SHAP analysis, the “black box” nature of ensemble models may still affect clinicians’ acceptance53. Thirdly, the model requires external validation in independent cohorts to better support real-world applications. Addressing these issues is crucial for translating RSF’s predictive advantages into meaningful clinical value. Beyond traditional clinicopathological features, emerging evidence suggests that genomic alterations may also play an important role in the prognosis of urological cancers. For example, recent studies have highlighted the relationship between loss of the Y chromosome (LOY) and tumor biology in renal, bladder, and prostate cancers, underscoring the potential of molecular markers in refining risk stratification 54. While our current RSF model was developed using readily available SEER clinicopathological data, integrating such molecular features in future ML frameworks may further enhance predictive accuracy and clinical utility.

Our study has several strengths. First, it is based on a large representative cohort of 22,426 patients, which enhances the generalizability of our findings55. Second, strong internal validation and bootstrapping techniques are used to support the stability and reliability of our models. Third, we apply several evaluation metrics to comprehensively assess model performance. In addition to model performance, we also investigated interpretability by using SHAP analysis. The SHAP results highlighted Age, pM, pT, and pN as the most influential predictors, which is in line with clinical experience. This enhances the transparency of the RSF model and may facilitate its potential clinical uptake. Nonetheless, some limitations should be recognized. One major limitation is the long enrollment period (2004–2019), during which changes in clinical practice, staging criteria, and treatment strategies may have occurred. Our RSF model was only evaluated using internal validation within the SEER dataset. Although the training–testing split provides a robust approach to assess model stability, the lack of external validation in an independent, contemporary cohort inevitably limits the generalizability and clinical applicability of the model. External validation in prospectively collected, multicenter cohorts is essential to confirm the reproducibility and robustness of our findings before the model can be adopted in real-world clinical decision-making. Miscoding (e.g., N2/M2, Nx/Mx, or AJCC edition harmonization) is a known issue in SEER and other registry datasets. Although our recoding minimized inconsistencies, some degree of misclassification bias cannot be excluded. Given the small number of affected cases, the overall impact is likely negligible, but this remains a general limitation of registry-based studies. Future studies using prospectively curated, multicenter datasets will be needed to confirm the reproducibility of our results without reliance on such data corrections. In addition, the SEER database lacks information about individual surgeons’ experience or technical details, making it impossible to directly assess ‘technical proficiency’. Another limitation concerns the choice of OS as the endpoint. OS includes both cancer-related and non-cancer-related deaths. Given the relatively favorable prognosis of cT1b RCC, competing risks such as cardiovascular mortality may have influenced the observed outcomes. Although cancer-specific survival (CSS) or cause-specific survival would provide a more precise oncological endpoint, we relied on OS because it is consistently available and less prone to misclassification in the SEER database. Nevertheless, future studies incorporating competing risk models or validated cause-specific endpoints are warranted to further refine prognostic accuracy. Finally, some potentially relevant clinical variables, such as comorbidities, physical status, and molecular markers, were not available in the dataset and may have further improved model performance had they been included.

Conclusions

Our study emphasizes the value of applying machine learning methods to enhance OS prediction in postoperative cT1b RCC patients. In particular, the RSF model provides greater accuracy and clinical utility compared with traditional AJCC staging and holds promise for improving individualized risk stratification and clinical decision-making. Future studies should focus on external validation and model improvement, as well as other variables such as comorbidity indices and genomic data.

Data availability

All data utilized for this analysis were obtained from the SEER database. The analysis code was derived from DecisionLinnc 1.0 software with built-in Python and R.

References

Bukavina, L. et al. Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma: 2022 Update. Eur. Urol. 82(5), 529–542 (2022).

Hussain, S. et al. Modern diagnostic imaging technique applications and risk factors in the medical field: A review. Biomed. Res. Int. 2022, 5164970 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Predictive value of extracellular volume fraction determined using enhanced computed tomography for pathological grading of clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A preliminary study. Cancer Imaging Off. Publ. Int. Cancer Imaging Soc. 25(1), 49 (2025).

Alonso-Gordoa, T. et al. Expert consensus on patterns of progression in kidney cancer after adjuvant immunotherapy and subsequent treatment strategies. Cancer Treat. Rev. 136, 102925 (2025).

Cesas, A. et al. Sequential treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients after first-line vascular endothelial growth factor targeted therapy in a real-world setting: Epidemiologic, noninterventional, retrospective-prospective cohort multicentre study. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149(10), 6979–6988 (2023).

Ouzaid, I. et al. Surgical metastasectomy in renal cell carcinoma: A systematic review. Eur. Urol. Oncol. 2(2), 141–149 (2019).

Mir, M. C. et al. Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy for clinical T1b and T2 renal tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Eur. Urol. 71(4), 606–617 (2017).

Huang, R., Zhang, C., Wang, X. & Hu, H. Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy for clinical T2 or higher stage renal tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 11, 680842 (2021).

Kunath, F. et al. Partial nephrectomy versus radical nephrectomy for clinical localised renal masses. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5(5), Cd012045 (2017).

Mao, W. et al. Comparing oncologic outcomes of partial and radical nephrectomy for T2 renal cell carcinoma: A propensity score matching cohort study and an external multicenter validation. World J. Urol. 43(1), 166 (2025).

Zeng, Z. et al. Perioperative and oncological outcomes of partial versus radical nephrectomy for complex renal tumors (RENAL Score ≥ 7): Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 31(7), 4762–4772 (2024).

Saitta, C. et al. Propensity score-matched analysis of radical and partial nephrectomy in pT3aN0M0 renal cell carcinoma. Clin. Genitourin. Cancer 23, 102343 (2025).

Fero, K., Hamilton, Z. A., Bindayi, A., Murphy, J. D. & Derweesh, I. H. Utilization and quality outcomes of cT1a, cT1b and cT2a partial nephrectomy: Analysis of the national cancer database. BJU Int. 121(4), 565–574 (2018).

Srivastava, A. et al. Delaying surgery for clinical T1b–T2bN0M0 renal cell carcinoma: Oncologic implications in the COVID-19 era and beyond. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 39(5), 247–257 (2021).

Caputo, P. A. et al. Cryoablation versus partial nephrectomy for clinical t1b renal tumors: A matched group comparative analysis. Eur. Urol. 71(1), 111–117 (2017).

Rahmani, A. M. et al. Machine learning (ML) in medicine: Review, applications, and challenges. Mathematics 9(22), 2970 (2021).

Bayram, B., Kunduracioglu, I., Ince, S. & Pacal, I. A systematic review of deep learning in MRI-based cerebral vascular occlusion-based brain diseases. Neuroscience 568, 76–94 (2025).

Ince, S., Kunduracioglu, I., Algarni, A., Bayram, B. & Pacal, I. Deep learning for cerebral vascular occlusion segmentation: A novel ConvNeXtV2 and GRN-integrated U-Net framework for diffusion-weighted imaging. Neuroscience 574, 42–53 (2025).

Liu, Z., Ma, H., Guo, Z., Su, S. & He, X. Development of a machine learning-based predictive model for transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis in White Americans: A SEER-based study. Transl. Androl. Urol. 13(12), 2681–2693 (2024).

Yang, W. et al. Machine learning to improve prognosis prediction of metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma treated with cytoreductive nephrectomy and systemic therapy. Biomol. Biomed. 23(3), 471–482 (2023).

Pacal, I. et al. A systematic review of deep learning techniques for plant diseases. Artif. Intell. Rev. 57(11), 304 (2024).

Dong, J., Chen, Y., Yao, B., Zhang, X. & Zeng, N. A neural network boosting regression model based on XGBoost. Appl. Soft Comput. 125, 109067 (2022).

Van Belle, V., Pelckmans, K., Van Huffel, S. & Suykens, J. A. Support vector methods for survival analysis: A comparison between ranking and regression approaches. Artif. Intell. Med. 53(2), 107–118 (2011).

Zhang, C., Pham, M., Fu, S. & Liu, Y. Robust multicategory support vector machines using difference convex algorithm. Math. Program. 169(1), 277–305 (2018).

Wang, H. & Li, G. A selective review on random survival forests for high dimensional data. Quant. Bio-sci. 36(2), 85–96 (2017).

Collins, G. S., Reitsma, J. B., Altman, D. G. & Moons, K. G. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed) 350, g7594 (2015).

Pepe, M. S., Fan, J., Feng, Z., Gerds, T. & Hilden, J. The Net Reclassification Index (NRI): A misleading measure of prediction improvement even with independent test data sets. Stat. Biosci. 7(2), 282–295 (2015).

Miller, T. D. & Askew, J. W. Net reclassification improvement and integrated discrimination improvement. Stat. Med. 6(4), 496–498 (2013).

Hashimoto, Y. & Yasunaga, H. Theory and practice of propensity score analysis. Ann. Clin. Epidemiol. 4(4), 101–109 (2022).

R Core Team (2024). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/.

Guo, Y. et al. Relationship between atherogenic index of plasma and length of stay in critically ill patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A retrospective cohort study and predictive modeling based on machine learning. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 24(1), 95 (2025).

Grosso, A. A. et al. Robot-assisted partial nephrectomy for renal cell carcinoma: A narrative review of different clinical scenarios. Asian J. Urol. 12, 210–216 (2025).

Carbonara, U. et al. Robotic-assisted partial nephrectomy for “very small” (< 2 cm) renal mass: Results of a multicenter contemporary cohort. Eur. Urol. Focus 7(5), 1115–1120 (2021).

Lyskjær, I. et al. Management of renal cell carcinoma: Promising biomarkers and the challenges to reach the clinic. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 30(4), 663–672 (2024).

Klatte, T., Rossi, S. H. & Stewart, G. D. Prognostic factors and prognostic models for renal cell carcinoma: A literature review. World J. Urol. 36(12), 1943–1952 (2018).

Zini, L. et al. Radical versus partial nephrectomy: Effect on overall and noncancer mortality. Cancer 115(7), 1465–1471 (2009).

Shapiro, D. D. et al. Comparing outcomes for patients with clinical T1b renal cell carcinoma treated with either percutaneous microwave ablation or surgery. Urology 135, 88–94 (2020).

Ou, W. et al. Impact of time-to-surgery on the prognosis of patients with T1 renal cell carcinoma: Implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Clin. Med. 11(24), 7517 (2022).

Khodabakhshi, Z. et al. Overall survival prediction in renal cell carcinoma patients using computed tomography radiomic and clinical information. J. Digit. Imaging 34(5), 1086–1098 (2021).

Tsimafeyeu, I. et al. Five-year survival of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the Russian Federation: Results from the RENSUR5 registry. Clin Genitourin Cancer 15(6), e1069–e1072 (2017).

Marconi, L., Desai, M. M., Ficarra, V., Porpiglia, F. & Van Poppel, H. Renal preservation and partial nephrectomy: Patient and surgical factors. Eur. Urol. Focus 2(6), 589–600 (2016).

Deng, H. et al. Partial nephrectomy provides equivalent oncologic outcomes and better renal function preservation than radical nephrectomy for pathological T3a renal cell carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Int. Braz. J. Urol. Off. J. Braz. Soc. Urol. 47(1), 46–60 (2021).

Mühlbauer, J. et al. Partial nephrectomy preserves renal function without increasing the risk of complications compared with radical nephrectomy for renal cell carcinomas of stages p T2-3a. Int. J. Urol. Off. J. Jpn. Urol. Assoc. 27(10), 906–913 (2020).

Guo, R. Q., Zhao, P. J., Sun, J. & Li, Y. M. Comparing the oncologic outcomes of local tumor destruction vs. local tumor excision vs. partial nephrectomy in T1a solid renal masses: A population-based cohort study from the SEER database. Int. J. Surg. (London, England) 110(8), 4571–4580 (2024).

Jiang, W. et al. Machine learning algorithms being an auxiliary tool to predict the overall survival of patients with renal cell carcinoma using the SEER database. Transl. Androl. Urol. 13(1), 53–63 (2024).

Hou, Z. et al. Explainable machine learning for predicting distant metastases in renal cell carcinoma patients: A population-based retrospective study. Front. Med. 12, 1624198 (2025).

Wang, F. et al. A novel nomogram for survival prediction in renal cell carcinoma patients with brain metastases: An analysis of the SEER database. Front. Immunol. 16, 1572580 (2025).

Yao, D. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting overall survival in patients with primary central nervous system germ cell tumors. Front. Immunol. 16, 1630061 (2025).

Acosta, P. H. et al. Intratumoral resolution of driver gene mutation heterogeneity in renal cancer using deep learning. Can. Res. 82(15), 2792–2806 (2022).

Wu, J. et al. Radiomics predicts the prognosis of patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma by reflecting the tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment. Cancer Imaging Off. Publ. Int. Cancer Imaging Soc. 24(1), 124 (2024).

Guo, Y. et al. Development of a new TNM staging system for poorly differentiated thyroid carcinoma: A multicenter cohort study. Front. Endocrinol. 16, 1586542 (2025).

Chen, X. et al. Risk of intraoperative hemorrhage during cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy surgery: Development and validation of an interpretable machine learning prediction model. EClinicalMedicine 78, 102969 (2024).

Meng, C., Trinh, L., Xu, N., Enouen, J. & Liu, Y. Interpretability and fairness evaluation of deep learning models on MIMIC-IV dataset. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 7166 (2022).

Russo, P. et al. Relationship between loss of Y chromosome and urologic cancers: New future perspectives. Cancers 16(22), 3766 (2024).

Deng, Q., Li, S., Zhang, Y., Jia, Y. & Yang, Y. Development and validation of interpretable machine learning models to predict distant metastasis and prognosis of muscle-invasive bladder cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 15(1), 11795 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and staff of the SEER database.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number 62376050) and the Science and Technology Bureau of Dalian (Project No. 2022RQ088).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sixiong Jiang and Long Lv conceived and designed the study. Zufa Zhang and Li Chen collected and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. Danni He and Sheng Guan contributed to data interpretation and visualization. Fengze Jiang and Weibing Sun participated in methodology development and statistical analysis. Fengze Jiang, Zuyi Chen, Feng Tian, and Hongxuan Song critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

All analyses and their reports followed the SEER reporting guidelines. Due to the anonymously coded design of the SEER database, study-specific institutional review board ethics approval was not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Z., Chen, L., Chen, Z. et al. Machine learning prediction of overall survival in patients with cT1b renal cell carcinoma after surgical resection using the SEER database. Sci Rep 15, 38366 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22342-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-22342-2