Abstract

This paper investigates an encased differential planetary gear train, comprising both fixed-axis and differential gear trains, for application in coaxial counter-rotating main gearboxes. The study analyzes the conditions required to achieve equal-speed counter-rotation between the inner and outer shafts, and examines the influence of varying loading conditions on internal power flow. A dedicated load test rig was designed and built for the main gearbox, utilizing two load motors to independently apply torque to the inner and outer output shafts. Power flow within the transmission system under differential loading conditions was indirectly determined through strain measurements. The study identifies four distinct power flow scenarios in the encased differential gear train under different load combinations applied to the inner and outer output shafts. Results indicate that when the load on the inner output shaft exceeds a critical threshold, a circulating power flow emerges within the system. The power flow behavior observed during testing shows strong agreement with theoretical predictions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The conventional single-rotor helicopter with a tail rotor is limited by its inherent configuration, which constrains further increases in maximum flight speed. A new high-speed helicopter configuration, employing coaxial equal-speed counter-rotating twin rotors to generate lift and a propeller to provide forward thrust, has been proposed and investigated1,2,3,4. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the Sikorsky Boeing SB > 1 DEFIANT, a coaxial twin-rotor high-speed helicopter developed collaboratively by Sikorsky and Boeing in the United States, has achieved a cruising speed of 240 knots5,6.

SB > 1 coaxial twin-rotor high-speed helicopter5.

The coaxial twin-rotor helicopter incorporates two sets of rotors arranged vertically along a common axis and rotating in opposite directions. The torques produced by these two sets of rotors counteract each other, ensuring balanced torque during steady heading flight. Yaw control is achieved by introducing a torque difference between the upper and lower rotors. Specifically, when the loads on the inner and outer rotor shafts differ, the resulting torque imbalance produces a yaw control moment on the airframe7,8,9.

The requirement for equal-speed counter-rotation in coaxial helicopter rotors necessitates a main gearbox transmission system with a single input and dual outputs. A typical configuration employs an encased differential planetary gear train, which integrates both a fixed-shaft gear train and a differential gear train by coupling their central gears10,11,12,13. This structure enables multi-path power flow, which results in a more complex transmission mechanism and dynamic behavior compared to conventional multi-stage planetary systems.

Numerous studies have investigated power flow in gear trains. References14,15,16,17,18 analyzed the power flow characteristics of encased planetary gear trains using methods such as graphical approach. However, limited research has focused specifically on gear train systems with a single input and dual outputs.

Yang14 introduced a novel method for calculating gear ratio, torque, and power using hypergraph theory and matrix operations, substantially reducing the time required to formulate system control equations. This approach was applied to examine power flow and efficiency in multi-flow planetary gear systems. Li15 employed graphical representation techniques to analyze power distribution in complex enclosed planetary gear transmissions, both with and without accounting for power loss, and computed the overall transmission efficiency in both cases. Cui et al.16 proposed a multi-attribute topological graph method for visualizing power flow analysis in one-degree-of-freedom planar spur encased planetary gear trains. This analytical method not only reflects the types of power flow but also describes the magnitude, direction, and transmission relationships of the power flow, particularly in the case of recirculating power. Hu17 developed a bond graph model for a dual planetary gear train power coupling mechanism with multiple inputs and multiple outputs. Based on the power flow criterion, the power flow of the transmission system under six different operating conditions was analyzed. Hussen18 derived the fundamental relationships among transmission ratio, torque direction, power ratio, and efficiency based on first principles, analyzed the dual-input, single-output mechanism, and identified the conditions under which power circulation occurs.

In recent years, research on coaxial dual-output gearboxes has focused on structural design, lubrication, and kinematic analysis19,20,21,22. Ivanov19 investigated the principles governing the motion behavior of a single-input dual-output differential mechanism under external loads. Studies20,21 conducted lightweight design, lubrication analysis, and tooth contact analysis for a differential planetary gear train used in an open rotor power gearbox, with the analyses supported by experimental validation. San22 introduced a design framework for determining the dimensions of a differential planetary gearbox for a contra-rotating open rotor. Considering requirements such as power transmission capacity, durability, and spatial constraints, a novel method was developed to design gears with maximum load capacity for this application.

Using the differential gear train power flow analysis method, Shi23 investigated the power flow behavior in a single-input, dual-output transmission system and derived the condition for avoiding circulating power within the system. However, the complex theoretical derivations presented in the study are challenging to interpret and apply directly in design practice, and no experimental or numerical validation has been provided to support these theoretical results. Improper parameter design in an encased differential planetary gear train may induce circulating power flow, which increases loads on gears and bearings, accelerates wear, and leads to additional power loss. These effects consequently result in reduced transmission efficiency, elevated operating temperatures, and overall degradation of transmission system performance24,25,26.

When a coaxial helicopter executes yaw maneuver, the torque balance between the inner and outer rotors is disrupted through collective pitch adjustments. This operation directly alters the load torque ratio between the inner and outer rotor shafts. Under these conditions, circulating power flow may arise within the encased differential planetary gear system. Therefore, investigating the power transmission characteristics of the gear system under different load conditions is essential for precise gearbox design and performance analysis.

In this study, the kinematic and load relationships within the encased differential planetary gear train are analyzed. The system parameter conditions required to achieve equal-speed counter-rotation of the inner and outer shafts are established, along with the corresponding rotational speed and torque relationships among all components. The power flow within the transmission system under varying loads applied to the inner and outer shafts is investigated. An experimental scheme is developed and implemented to validate the theoretical findings.

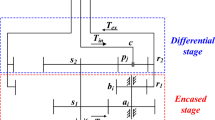

Analysis of kinematic and load relationship

The research subject of this paper is the encased differential gear transmission system of a coaxial main gearbox, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In this system, the fixed-axis gear train, comprising the sun gear s1, the stepped planet gears ai and bi, and the ring gear r1, is referred to as the encased stage. The first gear step of the stepped planet gears meshes with the sun gear s1, while the second gear step meshes with the ring gear r1. The differential planetary gear train, which consists of the sun gear s2, the planet gears pj, the carrier c2, and the ring gear r2, is denoted as the differential stage. The encased stage and the differential stage are interconnected through the dual sun gear and the dual ring gear arrangement.

Power is input into the system through the dual sun gear shaft and is subsequently divided into two transmission paths. One portion is transmitted to the ring gear r1 via the encased stage, while the other portion is transferred to carrier c2 and ring gear r2 via the differential stage. Power from carrier c2 is output directly through the inner shaft, whereas power from both ring gears r1 and r2 converges before being output through the outer shaft.

Schematic diagram of the encased differential gear transmission system10.

Kinematic analysis of the encased differential planetary gear train

A kinematic analysis is first performed to establish two aspects: the conditions for achieving equal and opposite rotational speeds at the inner and outer output shafts, and the rotational speed relationships among all components.

Given a transmission system input speed of nin, the angular velocity of sun gear s1, denoted as \(\omega_{\text{s1}}\), is given by:

Based on the structural characteristics of the transmission system shown in Fig. 2, the transmission ratio of the encased gear stage is given by:

where \({{z}}_{\text{s1}}\), \({{z}}_{\text{a}}\), \({{z}}_{\text{b}}\), and \({{z}}_{\text{r1}}\) are the tooth numbers of sun gear s1, stepped planet gears ai and bi, and ring gear r1, respectively. The angular velocity \({{\omega}}_{\text{r1}}\) of ring gear r1 in the encased stage is therefore:

In the differential gear system, the angular velocities of sun gear s2, carrier c2, and ring gear r2 satisfy the following relationship23:

where \({{\omega}}_{\text{s2}}\), \({{\omega}}_{\text{r2}}\), and \({{\omega}}_{\text{c2}}\) are the angular velocities of sun gear s2, ring gear r2, and carrier c2, respectively. The parameter \({{p}}_{\text{2}}\) is the characteristic parameter of the differential stage, defined as:

where \({{z}}_{\text{s2}}\) and \({{z}}_{\text{r2}}\) are the tooth numbers of sun gear s2 and ring gear r2, respectively. Based on the structural configuration of the transmission system, the following kinematic constraints apply:

Combining Eqs. (3) and (4), the angular velocity of carrier c2 is obtained as:

Equation (6) shows that when the tooth numbers are selected achieve a transmission ratio \({{i}}_{\text{c2r2}}=-1\), the carrier and ring gear rotate at equal speeds in opposite directions.

Applying the relative motion principle by imposing a common rotation \(-{{\omega}}_{\text{c2}}\) to the entire differential gear train, the carrier becomes stationary relative to the new reference frame, converting the epicyclic train into an equivalent fixed-axis gear train. In this converted mechanism, the relative angular velocity ratio between planet gear p and ring gear r2 is:

where \({{z}}_{\text{p}}\) is the number of teeth of planet gear p, and \({{\omega}}_{\text{p}}\) is its absolute angular velocity. Combining Eqs. (6) and (7), the absolute angular velocity of planet gear p is derived as:

Load relationship analysis of the encased differential planetary gear train

When the inner and outer output shafts are subjected to rotor loads, the input torque to the encased differential gear train is distributed through the dual sun gear shaft to the sun gears of both the encased and differential stage. The torque is then transmitted via the respective planet gear sets (including stepped planet gears) to the planet carrier and the ring gear for output. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the following relationship holds:

where \({{p}}_{\text{in}}\), \({{n}}_{\text{in}}\), and \({{T}}_{\text{in}}\) are the input power, input speed, and input torque, respectively. \({{T}}_{\text{s1}}\) and \({{T}}_{\text{s2}}\) denote the torques on sun gears s1 and s2. Neglecting power losses, the torque relationship for the encased-stage components is:

where \({{T}}_{\text{r1}}\) is the torque on ring gear r1. In the differential gear train operating under steady rotation, the power and torque satisfy the equilibrium conditions27, expressed as:

where, \({{T}}_{\text{s2}}\), \({{T}}_{\text{c2}}\), and \({{T}}_{\text{r2}}\) represent the torques on sun gear s2, carrier c2, and ring gear r2, respectively.

According to the principle of relative motion, the transmission ratio of the converted differential gear train mechanism is:

In this converted mechanism, the carrier c2 is stationary and thus transmits no power. Since the sun gear s2 and ring gear r2 rotate in opposite directions, their power relationship satisfies:

where \({{\omega}}_{\text{s2}}^{\text{c2}}\) and \({{\omega}}_{{\text{r}}_{2}}^{{\text{c}}_{2}}\) denote the angular velocities of sun gear s2 and ring gear r2 in the conversion mechanism, respectively.

Combining Eqs. (11) to (13), the torque relationships among the components of the differential gear train are obtained as follows:

Thus, the proportional relationship among the torques transmitted by the components of the differential stage is:

The load torques on the inner and outer output shafts are given by:

where \({{T}}_{\text{c}}\) and \({{T}}_{\text{r}}\) represent the torques on the inner and outer output shafts, respectively.

The torque acting on each component can be determined by solving the system of equations comprising (9), (10), (15), and (16). The analysis demonstrates that the torque distribution throughout the system components depends on both the transmission ratios of the gear system and the load torques applied to the inner and outer shafts.

Influence of outer and inner shaft loads on power flow

Equation (15) indicates that the torques on the differential stage components maintain a fixed proportional relationship, which is determined solely by the transmission ratio and is independent of other parameters.

Based on this analysis, Fig. 3 illustrates the power transmission behavior when the load on the outer shaft remains constant at Tr, while the load on the inner shaft, \({T}_{c}\), increases gradually from zero.

(1) When only the outer shaft is subjected to the load Tr, and the inner shaft load Tc is zero, the torque \({{T}}_{\text{c2}}\) transmitted by the differential stage carrier is zero according to Eq. (16). Under this condition, the differential stage does not transmit torque. All torque is transferred to the outer output shaft through the ring gear of the encased stage. The corresponding power flow is illustrated in Fig. 3a.

(2) As the load Tc on the inner shaft increases, the torque on the differential stage carrier Tc2 increases. Consequently, the torque on the differential stage ring gear Tr2 also rises, while the torque on the encased stage ring gear Tr1 decreases. The power flow in this case is shown in Fig. 3b.

(3) when the load Tc on the inner output shaft increases to

the entire load on the outer shaft is supported solely by the ring gear of the differential stage, and the encased stage gear train ceases to transmit torque. At this point, the torque Tr1 on the encased stage ring gear becomes zero. The power flow under this condition is depicted in Fig. 3c.

(4) When the inner shaft load Tc increases beyond the critical value defined by Eq. (17), the torque supplied to the outer shaft by the differential stage exceeds the external load Tr. The excess torque circulates back through the encased stage, resulting in a negative torque Tr1 and creating a circulating power flow. The power flow in this scenario is shown in Fig. 3d.

Power flow calculation example for the encased differential gear train

This section analyzes the power flow using the transmission system parameters of a coaxial helicopter, listed in Table 1. The selected parameters satisfy the condition for equal-speed counter-rotation of the inner and outer output shafts and yield an overall reduction ratio of approximately 5.63.

With a constant torque of Tr = 2815 N m applied to the outer output shaft and the torque on the inner shaft Tc increased from zero to 2Tr , the resulting torques Tr1 and Tr2—transmitted by the ring gears of the encased and differential stages, respectively—are calculated and presented in Fig. 4. In the figure, the solid and dashed lines represent the torques on the ring gears of the encased and differential stages, Tr1 and Tr2, both plotted as functions of the inner shaft torque.

As shown in Fig. 4, when the main gearbox operates under only an outer shaft load Tr, the torque on the differential stage ring gear Tr2 is initially zero. As the load on the inner shaft increases, the torque Tr2 rises, while the torque Tr1 on the encased stage ring gear decreases. This trend occurs because a growing portion of the outer shaft load is supported by the differential stage, reducing the share of torque transmitted through the encased stage ring gear.

The torque Tr1 decreases to zero when the inner shaft torque reaches the critical value defined by:

At this critical point, the entire outer shaft load is supported by the differential stage ring gear, and no power is transmitted through the encased stage. If the inner shaft load continues to increase beyond this critical value, the torque on the encased stage ring gear Tr1 becomes negative, and circulating power flow emerges within the system.

When equal loads Tc=Tr=2815 N m are applied to the inner and outer shafts, respectively, the torques on the encased and differential stage ring gears are calculated as follows:

The load distribution coefficients for the encased and differential stage gear trains are therefore:

This result indicates that under equal inner and outer shaft loading, the differential stage ring gear r1 transmits 30.1% of the total load on the outer shaft, while the encased stage ring gear r2 transmits the remaining 69.9%.

Experimental validation

A test scheme was designed and a dedicated bench was constructed to measure the power flow in the coaxial contra-rotating main gearbox. Resistance strain gauges were installed on the ring gears to measure strain, from which can indirectly obtain the power flow distribution of the encased stage and differential stage. By adjusting the load motor torques, the influence of varying load conditions on the power flow through each transmission path was investigated.

Experimental setup

Figure 5 illustrates the overall layout of the test rig. A driving motor serves as the power source, which drives the coaxial counter-rotating gearbox through a bevel gear reversal unit. Two load motors independently apply torque to the inner and outer output shafts of the main gearbox; each is also connected via bevel gear reversals.

The test object is a coaxial contra-rotating gearbox. The arrangement of the strain gauges and data acquisition equipment is shown in Fig. 6. The strain gauges are mounted on the outer surface of the transmission ring gear. The strain signal acquisition instrument and its counterweight assembly are fixed to the outer output shaft ‘s coupling and rotate with it during testing.

The strain gauges used in the experiment were model BA120-3HA-150 (11), with a resistance of 120.2 ± 0.3 (Ω) and a sensitivity coefficient of 1.95 ± 1%. Multiple strain gauges were mounted on the transmission ring gear, which can form a half bridge or full bridge circuit to measure the torque of the ring gear. Figure 7 shows the transmission ring gear with the installed strain gauges.

In this experiment, a DH5916 wireless data acquisition unit, with a maximum sampling frequency of 100 kHz, was used to collect the strain data. The unit is mounted on a bracket fixed to the output shaft coupling, as shown in Fig. 8.

Test procedure and data acquisition

To analyze the power distribution between the encased and differential stage under various loads, the test parameters listed in Table 2 were used for the main gearbox power flow tests.

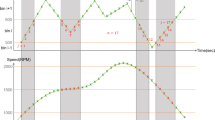

Loading tests were performed on the coaxial main gearbox. The load motor input torque was sequentially set according to Table 2, and the resulting strain on the transmission ring gear was measured for each case, as shown in Fig. 9. Using Eqs. (15) and (16), the load on the transmission ring gear was calculated for the five test cases listed in Table 2. The calculated torque values and the experimentally measured strain data are summarized in Table 3.

Results and discussion

This section presents the experimental results and discusses their implications through a direct comparison with the theoretical predictions established in Section Analysis of kinematic and load relationship. The measured strain data and corresponding calculated torque values under the five load cases (Fig. 9; Table 3) serve as the basis for validating the theoretical models.

Validation of power flow regimes

The experimental results robustly validate the distinct power flow regimes theorized in Section Influence of outer and inner shaft loads on power flow, confirming the system’s behavior under varying load conditions.

As shown in Fig. 9; Table 3, the measured strain decreases markedly as the operating condition shifts from Case 2 (\({T}_{c}=0\)) to Case 3 (\(0<{T}_{c}<{T}_{c}^{cv}\)). This trend occurs because, while the outer shaft load remains constant, the application of load to the inner shaft causes the outer shaft load to be shared between the encased and differential stages, rather than being supported entirely by the encased stage. As a result, the torque transmitted through the encased stage ring gear decreases significantly—from 100% to approximately one-third of the total outer shaft load. These load sharing behaviors correspond to the transition of power flow patterns from that illustrated in Fig. 3a to b.

A pivotal experimental finding is the clear manifestation of circulating power flow during the transition from Case 3 (\(0<{T}_{c}<{T}_{c}^{cv}\)) to Case 4 (\({T}_{c}>{T}_{c}^{cv}\)). The emergence of negative strain values provides definitive experimental evidence that power flows back from the differential stage to the encased stage—a key behavioral characteristic predicted by the theoretical load analysis. This phenomenon arises because, under these load conditions, the fixed proportion of torque transmitted to the differential stage ring gear flows backward into the encased stage, leading to an internal circulating power flow. This transition corresponds to the change of the power flow pattern from Fig. 3b to d.

Discrepancy analysis and model refinement

A quantitative comparison between the theoretical and experimental results across all load cases is summarized in Table 3. The close agreement in both variation trends and magnitudes confirms the overall correctness of the proposed kinematic and load analysis models.

Despite the high overall consistency, minor discrepancies are observed. These deviations primarily stem from several factors not fully considered in the ideal theoretical model, the most critical being the composite deformation of the transmission ring gear under load. The theoretical model accounts for torsional deformation but assumes other deformations are negligible. However, under actual operating conditions, the ring gear undergoes composite deformation—including bending deformation, radial elastic deformation, and other forms—when subjected to planetary gear meshing forces. This composite deformation alters the local strain field at the strain gauge mounting locations, resulting in measured strain that is not a simple function of pure torque load, but rather a composite representation of all deformations coupled together.

Future modeling efforts can be improved by incorporating finite element analysis to quantify ring gear deformation effects and establish a more comprehensive strain-torque calibration model.

Implications for system design

These experimental results have direct guiding significance for the design and operation of the transmission system of coaxial contra-rotating gearboxes.

The excellent agreement between theory and experiment confirms that the models established in Section Analysis of kinematic and load relationship are not only mathematically rigorous but also reliable for practical engineering applications. They equip designers with an effective tool to predict system behavior, optimize load distribution, and select gear parameters that proactively avoid the detrimental regime of circulating power, thereby enhancing the transmission efficiency and reliability of the gearbox system.

Accordingly, designers should prioritize operation within Regime 2 (as illustrated in Fig. 3b), where power is efficiently distributed without circulation. Adhering to this guideline mitigates risks of excessive wear, heat generation, and associated power loss. The derived critical load condition (Eq. 17) offers a clear and actionable criterion for defining these safe operational boundaries.

Conclusions

This study investigated the power flow and load distribution in an encased differential planetary gear train under varying operational conditions, employing an integrated approach of theoretical modeling and experimental validation. A dedicated test rig was designed and instrumented with strain gauges on the transmission ring gear, with data acquired in real time using a dynamic data acquisition system. By systematically controlling torque applied to the inner and outer output shafts, strain responses were captured under multiple load cases, enabling detailed analysis of power flow distribution. The main findings of this study are summarized as follows:

-

(1)

When the gear tooth numbers satisfy a specific kinematic relationship, the system enables equal-speed counter-rotation of the inner and outer output shafts—through the planet carrier and the ring gear, respectively—making it suitable for applications such as coaxial twin-rotor helicopters.

-

(2)

Four distinct power transfer modes were identified when the inner shaft load was increased under constant outer shaft load. A critical load threshold was derived, beyond which circulating power flow occurs, resulting in reduced transmission efficiency and increased internal loading.

-

(3)

The self-designed test platform successfully acquired strain data under various loads. Measured strain trends agreed well with theoretical predictions, and negative strain values under reflux conditions provided clear evidence of power reversal, thereby validating the proposed kinematic models.

These findings provide critical guidance for avoiding circulating power flow and enhancing the transmission efficiency and reliability of coaxial rotor systems through optimized load distribution and gear parameter selection.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- \({{z}}_{\text{s1}}\) :

-

Number of teeth of gear s1

- \({{\omega}}_{\text{s1}}\) :

-

Angular velocity of gear s1

- \({i}\) :

-

Transmission ratio

- \({{T}}_{\text{s1}}\) :

-

Torque of the sun gear s1

- \({{\omega}}_{\text{r2}}^{\text{c2}}\) :

-

Angular velocity of the ring gear r2 relative to the carrier c2

- \({{i}}_{\text{s2r2}}^{\text{c2}}\) :

-

Angular velocity ratio between the sun gear s2 and the ring gear r2 relative to the carrier c2

References

Passe, B., Sridharan, A. & Baeder, J. Computational investigation of coaxial rotor interactional aerodynamics in steady forward flight. In 33rd AIAA Applied Aerodynamics Conference, Dallas, TX (2015).

Bouwer, S. & Kaiser, E. Investigation of performance, loads, and vibrations of a coaxial helicopter in high-speed flight. In 72nd Annual AHS International Forum and Technology Display, West Palm Beach (2016).

Go, J. I., Kim, D. H. & Park, J. S. Performance and vibration analyses of lift-offset helicopters. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2017, 1865751 (2017).

Qiu, Y., Li, Y., Lang, J. & Wang, Z. Dynamics analysis and control of coaxial high-speed helicopter in transition flight. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 137, 108278 (2023).

Scott, B. & Eric, K. Design and development of the main rotor gearbox for the Sikorsky Boeing SB>1 DEFIANT JMR technology demonstrator aircraft. In 75th Vertical Flight Society Annual Forum 2949–2957 (2019).

Bouwer, S. & Bowen, D. W. Leveraging geometry optimization tools to reduce component weight, development cost, and design schedule. In 72nd Annual AHS International Forum and Technology Display (2016).

Yuan, Y., Thomson, D., Chen, R. & Dunlop, R. Heading control strategy assessment for coaxial compound helicopters. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 32, 2037–2046 (2019).

Chen, M. Technology characteristic and development of coaxial rotor helicopter. Aeronaut. Manuf. Technol. 17, 26–31 (2009).

Yuan, X., Che, X., Zhu, R. & Chen, W. Effect of bearing support parameters on the radial and angular deformation of rotor shaft gear based on CRDRS support configuration with intermediate bearing support. Machines 13, 513 (2025).

Zhang, D., Zhu, R., Fu, B. & Tan, W. Modal properties of contra-rotating encased differential gear train used in coaxial helicopter. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 8, 799–814 (2020).

Zhang, D., Cui, J., Zhu, R. & Li, M. Dynamic modeling and analysis of the rotor-stator coupling system of a coaxial contra-rotating gearbox. Sci. Rep. 13, 10076 (2023).

Yue, Z., Chen, Z., Qu, J. & Li, Y. Analysis of the dynamic characteristics of coaxial counter-rotating planetary transmission system. Appl. Sci. 14, 2123 (2024).

Che, X., Yu, H., Zhang, C. & Zhu, R. The effect of floating spline parameter on the dynamic characteristic of encased differential planetary gear train. Sci. Rep. 14, 3136 (2024).

Yang, F., Feng, J. & Zhang, H. Power flow and efficiency analysis of multi-flow planetary gear trains. Mech. Mach. Theory 92, 86–99 (2015).

Li, J. & Hu, Q. Power analysis and efficiency calculation of the complex and closed planetary gears transmission. Energy Procedia 100, 423–433 (2016).

Cui, Y., Gao, J., Ji, X. & Zhou, X. The multi-attribute topological graph method and its application on power flow analysis in closed planetary gear trains. Adv. Mech. Eng. 10, 1–9 (2018).

Hu, J. et al. Power flow and efficiency analyses of dual planetary coupling mechanism based on bond graph theory. J. Adv. Mech. Des. Syst. Manuf. 12, 1–13 (2018).

Hussen, H. A., Esmail, E. L. & Hussen, R. A. Power flow simulation for two-degree-of-freedom planetary gear transmissions with experimental validation. Model. Simul. Eng. 2020, 8837605 (2020).

Ivanov, K. S. Dynamics of gear differential with one input only. In 12th IFToMM World Congress 1–6 (2007).

Imai, H. et al. Design and test of differential planetary gear system for open rotor power gearbox. In Proceedings of the ASME 2013 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (ASME, 2013). https://doi.org/10.1115/DETC2013-1208.

Sato, K. et al. Design, analysis, and tests of differential planetary gear system for open rotor power gearbox (final report). In Proceedings of the ASME 2015 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference (ASME, 2015). https://doi.org/10.1115/DETC2015-46414

San Benito Pastor, D. G. et al. Preliminary design framework for the power gearbox in a contra-rotating open rotor. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 143, 041022 (2021).

Shi, W. K., Li, L. J., Qin, D. T. & Lim, T. C. Analysis of power flow in a counter-rotating epicyclic gearing for electrical propulsion system. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 225, 2973–2980 (2011).

Pennestri, E. & Freudenstein, F. The mechanical efficiency of epicyclic gear trains. J. Mech. Des. 115, 645–651 (1993).

Del Castillo, J. M. The analytical expression of the efficiency of planetary gear trains. Mech. Mach. Theory 37, 197–214 (2002).

Wu, Y. C. & Cheng, C. H. Computing the power flow and mechanical efficiency of in-hub bicycle transmissions. Eng. Comput. 31, 267–282 (2014).

Marciniec, A., Sobolak, M. & Połowniak, P. Graphical method for the analysis of planetary gear trains. Alex. Eng. J. 61, 4067–4079 (2022).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Laboratory of Science and Technology on Helicopter Transmission (Grant No. HTL-O-21G09) and the Scientific Research (Starting) Foundation for High-level Talents in Nanjing Vocational College of Information Technology (Grant No. YB20210208).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Donglin Zhang, Rupeng Zhu and Luqiang Ma wrote the main manuscript text, Wei Zhang and Ji Cui prepared Figs. 2 and 3 The drawings in Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 were drawn by the author Zhang Donglin. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, D., Zhu, R., Zhang, W. et al. Research on power flow of encased differential gear train in coaxial contra-rotating gearbox. Sci Rep 15, 39387 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23712-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23712-6