Abstract

Classical Chinese translation presents significant challenges: manual methods suffer from high costs and inconsistent quality, while both traditional machine translation and approaches relying solely on Large Language Models often fail to adequately capture intricate semantic nuances and cultural specificities. To overcome these limitations, this study proposes an LLM-driven multi-agent framework that decomposes translation into word-level interpretation, paragraph-level generation, and multi-dimensional review, integrating a specialized Key Word Interpretation Database, Retrieval-Augmented Generation, and iterative feedback. Experiments on The Records of the Grand Historian of China: The Hereditary Houses and the Biographies, Volume 7–10 show average improvements of 18.8–25.7% in BLEURT, BLEU-1, and METEOR over single-model baselines, with \(\sim\) 12.7% reduction in score variance, indicating enhanced stability. Human evaluation confirms gains in fluency, adequacy, and cultural fidelity, particularly for weaker baselines. Ablation results reveal the indispensable roles of contextual coherence review, grammatical validation, and keyword interpretation, while efficiency analysis shows that compared with the framework without useful agents, the running time of the proposed method increases by 3.21 times, with the main contributing factor being the introduction of keyword interpretation. The framework excels in resolving polysemy, preserving cultural allusions, and improving semantic coherence. Beyond Classical Chinese, it offers a transferable blueprint for other historical or low-resource languages, supporting high-fidelity cultural heritage translation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Classical Chinese, serving as the communicative and written language of ancient China, is the vehicle for millennia of accumulated Chinese cultural heritage. Its concise linguistic structure and profound cultural connotations grant it significant importance in linguistic, literary, and historical research. However, apart from a selection of canonical texts, a vast number of ancient writings still lack translations into Modern Chinese. As time progresses and language continues to evolve, it will become increasingly challenging for contemporary readers to access, comprehend, and learn from these ancestral works. Consequently, the task of Classical Chinese translation is acquiring growing importance.

While traditional manual translation can achieve accuracy, it suffers from low efficiency, rendering it inadequate for meeting the demands of contemporary cultural dissemination. Concurrently, the rapid advancement of AI has led to significant breakthroughs in Natural Language Processing (NLP). Recent advances in semantic enhancement techniques have demonstrated the importance of semantic understanding in complex text processing tasks1, providing insights that are particularly relevant for handling the nuanced semantics of Classical Chinese. Building on these semantic processing foundations, Large Language Models (LLMs)2, trained on vast corpora, have emerged as powerful tools. Leveraging their language understanding capabilities enhanced by semantic representation learning, LLMs offer novel potential solutions to inherent challenges in Classical Chinese translation, such as ensuring grammatical consistency, achieving semantic fidelity, and performing contextual analysis3.Nevertheless, when confronted with the highly complex semantic structures and intricate contextual information characteristic of Classical Chinese, LLMs exhibit limitations, including insufficient semantic accuracy, particularly within multi-layered contexts.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes an LLM-driven multi-agent method for Classical Chinese translation. This approach integrates the powerful language understanding capabilities of LLMs with the task coordination mechanisms inherent in multi-agent systems (MAS)4. By assigning distinct roles and configuring appropriate tools for the LLMs, they are effectively transformed into specialized intelligent agents that collaborate to achieve precise translation. Specifically, this research presents the following key contributions:

-

(1)

A novel LLM-based multi-agent methodology for Classical Chinese translation is proposed, which enhances the baseline translation capabilities of LLMs through synergistic multi-agent collaboration.

-

(2)

A dedicated database containing interpretations for key words has been introduced. Agents automatically retrieve relevant interpretations from this database to refine and optimize translation outcomes, thereby facilitating more accurate Classical Chinese translation.

-

(3)

A collaborative multi-agent framework incorporating an iterative optimization mechanism has been developed. This ensures the semantic accuracy, contextual coherence, and grammatical correctness of the translated content, while maximally preserving the original connotations and cultural essence embedded within the Classical Chinese text.

Related work

Figure 1 presents a timeline illustrating the development of machine translation methods in the field of Classical Chinese translation. It outlines the evolution from rule-based machine translation to neural machine translation, and further to the application of LLMs and MAS.

Foundational work in classical Chinese translation

Machine translation research for Classical Chinese commenced in the 1970s with rule-based machine translation (RBMT)5. This approach, relying on human-designed dictionary mappings and grammatical rules, exhibited some effectiveness in constrained scenarios but struggled to handle the rich polysemy and context-dependency inherent in Classical Chinese. Subsequently, Statistical Machine Translation (SMT) techniques, introduced by Brown et al. in 19936, marked an advancement by constructing conditional probability models, improving translation performance for general languages. Nevertheless, SMT’s effectiveness remained limited when dealing with Classical Chinese due to its high context dependency and the scarcity of parallel corpora.

In recent years, propelled by advancements in deep learning, Neural Machine Translation (NMT) has become the predominant approach for Classical Chinese translation. The quality of machine translation significantly improved following the introduction of architectures like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs)7, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks8, and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs)9 significantly improved machine translation quality. Subsequently, the Transformer model, proposed by Vaswani et al.10, further advanced the field. Its encoder-decoder architecture enhanced the model’s capacity to capture sentence-level context, establishing a new paradigm for machine translation.

Within the specific domain of Classical Chinese translation, Zhang et al. (2019) proposed a sequence-to-sequence model leveraging bidirectional RNNs for translating ancient Chinese texts into Modern Chinese, addressing corpus scarcity via an unsupervised sentence alignment method11. To tackle the data bottleneck, Liu et al. (2019) constructed a large-scale dataset containing 1.24 million parallel sentence pairs of ancient and modern Chinese. They compared the performance of SMT and various NMT models, thereby providing a solid foundation for subsequent research12. Tian et al. (2021) developed AnchiBERT, a pre-trained model based on the BERT architecture, specifically tailored for understanding and generation tasks involving ancient Chinese13.

Application of large language models

LLMs, typically based on the Transformer architecture, possess billions to hundreds of billions of parameters. They have demonstrated formidable language understanding and generation capabilities within the field of NLP. Consequently, recent research has begun exploring the potential of LLMs for Classical Chinese translation, focusing on both specialized model tuning and the creation of robust evaluation benchmarks. For instance, Cao et al. (2024) introduced the TongGu model, specifically designed for Classical Chinese understanding. By employing incremental pre-training and techniques such as Redundancy-Aware Tuning (RAT) and a specialized Retrieval-Augmented Generation approach (CCU-RAG), they significantly improved the accuracy of Classical Chinese comprehension14. In the specialized domain of poetic texts, Chen et al. (2024) developed PoetMT, a benchmark for evaluating LLM performance in translating classical Chinese poetry, and proposed a retrieval-augmented method to incorporate cultural knowledge15.

To standardize evaluation, several comprehensive benchmarks have been developed. Zhang & Li (2023) presented ACLUE, which assesses LLMs on a range of ancient Chinese understanding tasks16. More recently, Cao et al. (2024) introduced C3Bench, a more extensive benchmark covering classification, retrieval, NER, punctuation, and translation, providing a rigorous framework for evaluating LLM capabilities in this domain17.

While these works have advanced the field by enhancing models (TongGu) and establishing evaluation standards (PoetMT, ACLUE, C3Bench), they primarily focus on improving the intrinsic capabilities of a single LLM or evaluating them. Our work builds upon these advancements but shifts the paradigm from single-model enhancement to a collaborative multi-agent system (MAS). Instead of relying on a monolithic model, we decompose the translation process into specialized subtasks, which allows for more targeted application of LLM strengths and systematic quality control, a structural distinction from the aforementioned studies.

Combined application of multi-agent technology and large language models

The semantic understanding, knowledge generation, reasoning, and memory capabilities inherent in LLMs enhance the efficiency of intelligent agents in handling complex tasks. The feasibility of LLM-driven agents was demonstrated by Reed et al.18. A general agent architecture is depicted in Fig. 2.

MAS consists of multiple autonomous yet collaborating agents, characterized by core features such as autonomy, interactivity, cooperativity, and distribution19. These characteristics enable MAS to adapt to dynamically changing complex environments and tackle tasks that are beyond the capabilities of a single agent.

The rapid evolution of LLMs has invigorated the field of MAS. Recent works have demonstrated the potential of multi-agent frameworks in complex reasoning and generation tasks. For example, Liang et al. (2023) proposed the Multi-Agent Debate (MAD) framework, which improves performance on tasks like machine translation by encouraging diverse reasoning through structured debates20.

More directly related to our work, Wu et al. (2024) proposed TransAgents, which focuses on literary translation by incorporating role-based agents such as translator, editor, and proofreader. While both our framework and TransAgents leverage a role-playing MAS, our approach is specifically tailored to the unique challenges of Classical Chinese. TransAgents employs a generalist ”Translate-Critique-Judge” workflow. In contrast, our framework implements a more granular task decomposition, with specialized agents for word-level interpretation, contextual coherence, and key-word review, directly addressing issues like polysemy and cultural allusions that are particularly acute in Classical Chinese. Our use of an external, structured Key Word Interpretation Database is another key differentiator, providing verifiable knowledge grounding that is not explicitly detailed in the TransAgents framework.

Beyond the field of language translation, MAS has also been successfully applied to tasks such as Visual Question Answering (VQA). For instance, the QSFVQA framework21 employs a question-type segregation strategy to improve processing efficiency and scalability, illustrating the versatility of MAS in solving complex, multi-step problems across diverse domains. These studies underscore the effectiveness of MAS in addressing the complexities of translation tasks through collaborative efforts.

Despite the notable progress achieved by the aforementioned studies, several key challenges persist. Firstly, existing LLMs, while possessing strong language understanding abilities, still fall short when dealing with the specific semantic ambiguities, polysemous characters, and cultural allusions prevalent in Classical Chinese. Secondly, single-model approaches struggle to simultaneously balance translation accuracy, fluency, and the preservation of cultural connotations. Thirdly, although MAS like TransAgents incorporate collaborative mechanisms, they primarily focus on simulating general literary translation workflows and lack specialized designs tailored to the unique characteristics of Classical Chinese.

Building upon the current state of research, this paper introduces a more comprehensive and systematic multi-agent approach for Classical Chinese translation, detailed in the subsequent section.

Methods

Translating Classical Chinese into Modern Chinese effectively, which is traditionally termed ”faithfulness, expressiveness, and elegance,” is complex. It requires not only accurately grasping the grammatical structures and lexical connotations of the ancient text but also preserving its inherent cultural depth. To address this challenge, this study constructs a multi-agent translation methodology leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs), aiming to produce translations that are both accurate and culturally rich.

Framework design

The translation approach proposed in this research utilizes LLMs as foundational support, combined with a multi-agent architecture featuring a modular design based on task types. The overall translation task is represented as a collection of paragraphs comprising the source text T initially segmented into a sequence of paragraphs based on semantic structure:

where P is the set of paragraphs derived from the original text T. Each paragraph \(p_j\) serves as an independent unit processed by the translation system.

Within this framework, the Translation Command Module consists of the Translation Command Agent (\(A_{TCM}\)). This module acts as the central task coordinator, responsible for paragraph segmentation, information dispatch, and results integration. The Translation Generation Module comprises the Word Translation Agent (\(A_{WT}\)) and the Paragraph-level Translation Agent (\(A_{PT}\)). The former focuses on retrieving and optimizing interpretations for key terms, while the latter generates initial translations based on these interpretations and the surrounding context. The Expert Review Module includes the Contextual Coherence Review Agent (\(A_{RC}\)), the Key Word Review Agent (\(A_{RW}\)), and the Grammatical Structure Validation Agent (\(A_{RG}\)). These three agents collaborate to perform multi-dimensional quality control on the translated text. The structure of the three modules is shown in Fig. 3.

The agents described above collectively form the set of agents within the system:

These multiple agents support each other through unified collaborative and feedback mechanisms, ensuring the coherence and high quality of the final translation output. The overall framework of the method is depicted in Fig. 4.

Agent task allocation

Based on the framework design outlined above, this section presents a comprehensive overview of how agents collaborate within the three modules. As illustrated in Figs. 5, 6 and 7, the Translation Command Module (Fig. 5) coordinates the overall workflow, the Translation Generation Module (Fig. 6) performs the core translation tasks, and the Expert Review Module (Fig. 7) ensures quality through multi-dimensional review. The following subsections detail how these modules work in concert to achieve high-quality Classical Chinese translation.

Translation command module

As depicted in Fig. 5, the Translation Command Module, consisting solely of the \(A_{TCM}\), serves as the central coordinator of the entire translation framework. This module orchestrates the translation workflow through three key functions: semantic segmentation, task distribution, and iterative refinement.

The \(A_{TCM}\) initiates the process by analyzing the Classical Chinese text T and performing semantic segmentation to create a paragraph set P. To maintain contextual coherence across paragraphs, it implements a memory mechanism \(M = \{ \hat{p}_1, \hat{p}_2,..., \hat{p}_{j-1} \}\), where \(\hat{p}_j\) represents the latest translation of paragraph \(p_j\). This global contextual memory ensures that subsequent translations can reference previously translated content, maintaining narrative consistency throughout the document.

The module’s iterative refinement process, central to achieving high-quality translations, operates through a feedback loop with the Expert Review Module. The initial translation \(\hat{p}_j^{(0)}\) undergoes iterative updates based on review feedback. Let \(\delta _j^{(k)}\) represent the set of modification suggestions from the k-th round, which needs to be converted into a specific textual increment \(\Delta _j^{(k)}\) via a mapping function \(\Psi (\cdot )\):

Upon receiving review feedback \(\delta _j^{(k)}\) from the k-th review round, the \(A_{TCM}\) coordinates translation updates according to:

where \(\oplus\) denotes the integration of mapped suggestions into the current translation. This process continues until either \(\delta _j^{(k)}=\emptyset\) (indicating approval) or a predefined iteration threshold K is reached, ensuring both quality and efficiency. Once the translation and review of all paragraphs are complete, the \(A_{TCM}\) integrates the finalized translations to generate the final output.

Translation generation module

Figure 6 illustrates the Translation Generation Module, which comprises two synergistic agents: the \(A_{WT}\) for micro-level semantic parsing and the \(A_{PT}\) for macro-level segment reconstruction. These agents work in tandem to transform Classical Chinese text into accurate and culturally rich Modern Chinese translations.

The \(A_{WT}\) focuses on interpreting key characters and words with significant cultural or semantic complexity. Utilizing Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG)22, it extracts key terms \(W_j\) from paragraph \(p_j\) and retrieves relevant interpretations from the specialized database D. The initial interpretation is obtained from database D using a retrieval function \(R_D\):

where \(S_i\) is the set of candidate interpretations for \(w_i\). Due to the polysemy of Classical Chinese words, the most suitable interpretation needs to be selected or adjusted from \(S_i\) based on context. The optimization process produces contextually appropriate interpretations:

This ensures that polysemous Classical Chinese terms are interpreted correctly within their specific context.

Building upon the \(A_{WT}\)’s output, the \(A_{PT}\) generates paragraph-level translations by integrating word interpretations with contextual memory. Initially, it substitutes the interpretations of key vocabulary based on \(\hat{W}_j\):

where \(h(p_j, \hat{W}_j)\) represents the initial transformation function applying \(\hat{W}_j\) to \(p_j\). To ensure coherence, the global context M must be referenced through the context adjustment function \(q(\cdot )\):

The complete paragraph translation process can be represented as:

where M represents the global context from previously translated paragraphs. This dual-agent approach ensures both lexical accuracy and contextual coherence, with the \(A_{PT}\) dynamically adjusting translations based on feedback from the Expert Review Module through the iterative mechanism described in Equation 4.

Expert review module

The Expert Review Module, visualized in Fig. 7, implements a comprehensive quality assurance system through three specialized review agents. This module transforms initial translations into polished, high-quality outputs through systematic multi-dimensional evaluation and iterative refinement.

The module employs three complementary review perspectives:

-

The \(A_{RC}\) evaluates contextual coherence by checking the overall consistency with the context at both logical and semantic levels:

$$\begin{aligned} \delta _{j,RC}^{(k)} = f_{RC}(\hat{p}_j^{(k)}, M) \end{aligned}$$(10) -

The \(A_{RW}\) verifies key word interpretations, possessing the same access capability to the Key Word Interpretation Database as the \(A_{WT}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \delta _{j,RW}^{(k)} = f_{RW}(\hat{p}_j^{(k)}, \hat{W}_j, D) \end{aligned}$$(11) -

The \(A_{RG}\) validates grammatical structure, ensuring grammatical correctness and readability:

$$\begin{aligned} \delta _{j,RG}^{(k)} = f_{RG}(\hat{p}_j^{(k)}) \end{aligned}$$(12)

These agents operate in concert within each review round, generating comprehensive feedback:

When \(\delta _j^{(k)} = \emptyset\), the translation achieves optimal quality and proceeds to final output. Otherwise, the feedback triggers another iteration of refinement through the Translation Generation Module. This multi-round review mechanism, integrated with the iterative processes shown in Figs. 5 and 6, ensures that each translation meets the highest standards of accuracy, coherence, and grammatical correctness while preserving the cultural essence of the Classical Chinese source text. The review mechanism maximally ensures the quality of the translation while reducing potential biases that might arise from errors within a single module.

Technical implementation of the method

Agent design

Leveraging continuous advancements in AI, numerous frameworks have emerged that enable users to rapidly construct intelligent agents and facilitate efficient integration with various tools and APIs. These frameworks enhance agent adaptability and flexibility within complex environments. Owing to AutoGen’s demonstrated excellence in MAS development, this research utilizes the AutoGen framework to build a high-performance multi-agent translation system.

The proposed method implements both synchronous and asynchronous communication modes. Synchronous communication is employed for interaction scenarios demanding immediate responses, such as task distribution from the \(A_{TCM}\) to the \(A_{WT}\), \(A_{PT}\). Asynchronous communication is utilized for non-blocking processes, including the collection and integration of review feedback. Each message incorporates metadata–such as message type, content payload, priority, and timestamp–to ensure the precision and traceability of information transmission.

-

(1)

Translation Command Agent(\(A_{TCM}\)): As the core coordinator, \(A_{TCM}\) utilizes the ‘GroupChat‘ and ‘GroupChatManager‘ functionalities provided by the AutoGen framework to manage and coordinate interactions among agents. It integrates a memory management tool to store previously translated paragraphs and their associated context within the global memory module M. This information is retrieved in real-time via tool calls as needed.

-

(2)

Word Translation Agent (\(A_{WT}\)): This agent leverages the AutoGen framework and integrates a database retrieval tool, denoted as \(R_D(w)\), to access the specialized word interpretation database D. It extracts interpretations for key words identified in the text and optimizes these interpretations based on the surrounding contextual information.

-

(3)

Paragraph-level Translation Agent (\(A_{PT}\)): \(A_{PT}\) utilizes the optimized interpretation results from \(A_{WT}\) as input. It invokes the LLMs via the AutoGen framework to generate an initial translation. Prompt engineering techniques are employed to guide the LLM, with prompts including the current paragraph’s text, interpretations of key terms (\(\hat{W}_j\)), and contextual information from the memory M. It integrates a context retrieval tool to access M, ensuring inter-paragraph coherence. Furthermore, it employs a feedback processing mechanism to iteratively refine the translation based on review suggestions received from the Expert Review Module.

-

(4)

Contextual Coherence Review Agent (\(A_{RC}\)): Operating within the AutoGen framework, \(A_{RC}\) accesses the global memory M to rapidly retrieve and analyze the contextual information surrounding the translation segment under review (\(\hat{p}_j^{(k)}\)). Its prompts instruct the LLM to compare the current translation with preceding and succeeding paragraphs, identify any logical or semantic inconsistencies, and generate specific modification suggestions.

-

(5)

Key Word Review Agent (\(A_{RW}\)): This agent uses prompts to guide the LLM in verifying the interpretations provided by \(A_{WT}\) against the paragraph content and global context. The prompts specifically emphasize the identification of potential mistranslations, particularly for polysemous words or culturally significant allusions. Additionally, \(A_{RW}\) integrates the same database retrieval tool \(R_D(w)\) as \(A_{WT}\), allowing it to independently access the interpretation database D to validate or correct interpretation results.

-

(6)

Grammatical Structure Validation Agent (\(A_{RG}\)): The \(A_{RG}\) inspects the grammatical structure of the generated translation. It identifies syntactic errors or expressions that deviate from standard Modern Chinese usage conventions. Based on its findings, it generates improvement suggestions aimed at enhancing the linguistic quality and fluency of the translation.

Detailed prompt templates are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Introduction of the Key word interpretation database

To enhance the translation system’s capability in accurately parsing key words in Classical Chinese, this research introduces a specialized interpretation database for key characters and words. This database is derived from the Dictionary of Frequently Used Characters in Ancient Chinese (5th Edition). Through the structured processing of the original dictionary data, an efficient and precise word interpretation database D was constructed. An entry in the database for a word w can be represented as:

where w represents a Classical Chinese word or term, and \(\text {def}_k\) denotes the k-th potential interpretation retrieved from the dictionary source.

This database not only provides essential interpretational support for the \(A_{WT}\) and \(A_{RW}\) but also seamlessly integrates with the overall multi-agent architecture of the platform. This integration effectively enhances the system’s translation accuracy and ensures consistency in the interpretation of interpretations.

The source data for this database originates from the aforementioned Dictionary of Frequently Used Characters in Ancient Chinese. This dictionary contains interpretations, pinyin transcriptions, and contextual usage examples for common words and characters found in Classical Chinese texts. As the original data exists in an unstructured text format, a comprehensive data processing and retrieval workflow was designed to enable efficient querying and parsing, ensuring seamless integration with the agent modules.

The database retrieval tool, \(R_D(w)\), can be abstractly represented as:

This function is invoked during the word translation or review stages to rapidly retrieve interpretations. It supports both character-by-character and word-based matching modes, selected based on the query.

Experiments and evaluation

This section elaborates on the test set, experimental setup, evaluation metrics, and experimental results. Furthermore, it provides an analysis of these results.

Test set

In this study, the test dataset is based on The Records of the Grand Historian of China: The Hereditary Houses and the Biographies, Volume 7–10 (史记·七十列传). The specific parallel corpus (Classical Chinese to Modern Chinese) was sourced from the open-source Classical-Modern Chinese parallel corpus provided by Northeastern University (available at https://github.com/NiuTrans/Classical-Modern). The Records of the Grand Historian of China: The Hereditary Houses and the Biographies, Volume 7–10 possesses not only a profound historical and cultural background but also highly concise linguistic features, fully embodying the challenges inherent in Classical Chinese translation.

The Seventy Biographies constitute approximately 49.9% of the entire Records of the Grand Historian, totaling 248,373 Chinese characters. It comprises seventy chapters (biographies) written in Classical Chinese, with lengths varying from 766 to 9,066 characters per chapter and an average length of 3,861 characters. This variation in chapter length introduces greater complexity and diversity to the translation task, serving to further validate the adaptability and stability of the proposed method when handling Classical Chinese texts of differing lengths. Specific details are shown in Fig. 8.

Experimental setup

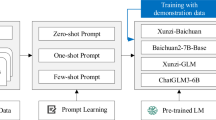

To comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of the multi-agent method, a controlled experiment was designed. The experimental groups included: (1) Single-Model Translation: Relying solely on the independent translation capabilities of each selected LLM. (2) Multi-Agent Method Translation: Integrating each respective LLM into the proposed MAS for translation. By comparing the results from these two groups, the performance improvement attributable to the multi-agent approach can be quantified.

Six representative LLMs were selected for the experiments, as detailed in Table 1. These models encompass diverse architectures and scales, allowing for a thorough assessment of the applicability of the multi-agent method.

In the experiments, all models utilized their default parameters with a temperature setting of 1.0. No task-specific fine-tuning was performed to ensure the fairness and comparability of the results.

Evaluation metrics

To conduct a comprehensive and multi-dimensional assessment of translation quality, we employed a suite of four widely-recognized automatic evaluation metrics. This approach mitigates the biases of any single metric and allows for a nuanced analysis of different quality aspects.

-

BLEU-1 (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy)24: Measures lexical fidelity by calculating the precision of unigram overlap between the generated translation and the reference, with a penalty for overly short translations.

-

ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation)25: We use ROUGE-1, ROUGE-2, and ROUGE-L to assess recall-based overlap of unigrams, bigrams, and the longest common subsequence, respectively, evaluating content similarity.

-

METEOR (Metric for Evaluation of Translation with Explicit Ordering)26: Captures semantic correspondence by considering synonymy, stemming, and word order, offering a more robust measure of translation adequacy than n-gram-only metrics.

-

BLEURT (Bilingual Evaluation Understudy with Representations from Transformers)27: A learning-based metric that leverages Transformer representations to model semantic similarity. It has been shown to correlate strongly with human judgments and is our primary metric for evaluating semantic accuracy28.

The combined use of these metrics provides a holistic view: BLEU and ROUGE assess surface-level lexical and phrasal matching, while METEOR and the learning-based BLEURT provide deeper insights into semantic and structural correctness.

Simulation analysis

This section presents and analyzes the experimental data to comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed multi-agent Classical Chinese translation method in terms of translation quality. The analysis focuses on two key aspects: a performance comparison of baseline models and the enhancement effect provided by the multi-agent method.

Baseline model performance comparison and analysis

To establish a performance baseline and understand the initial capabilities of various models on the task, several common LLMs were evaluated independently. The experimental results detail the performance differences among these baseline models on the Classical Chinese translation task. Table 2 specifically lists the performance of the six baseline models, measured by evaluation metrics including BLEURT, BLEU-1, and METEOR.

As shown by the baseline model test results in Table 2, DeepSeek V3 achieved the best performance across most metrics, with a BLEURT score of 0.635 and a BLEU-1 score of 0.481, significantly surpassing the other baseline models. This indicates its comprehensive advantages in lexical matching, phrase overlap, and semantic similarity. The performances of Qwen Plus and Qwen Turbo were comparable, with BLEURT scores of 0.531 and 0.528, respectively, demonstrating their strong adaptability to Chinese-language tasks. GLM Air exhibited moderate performance. GLM Flash showed weaker performance. GPT-4o Mini consistently scored the lowest across all metrics, highlighting its limitations in the context of Classical Chinese translation.

Regarding the standard deviation (std) data presented in Table 2, DeepSeek V3’s BLEURT std of 0.121 was lower than that of the other models, indicating more stable translation quality. Conversely, GPT-4o Mini exhibited higher standard deviations, such as a BLEU-1 std of 0.197, reflecting greater variability in its translation results and suggesting potential difficulties with certain complex sentence structures.

The superior performance of DeepSeek V3 likely stems from its extensive pre-training on Chinese corpora and stronger language modeling capabilities, enabling it to better capture the semantics and sentence structures of Classical Chinese. The Qwen series models, specifically optimized for Chinese, demonstrated good stability in Classical Chinese translation. As a lightweight model, GLM Flash sacrifices some depth in language understanding, leading to its comparatively lower performance. The relatively poor performance of GPT-4o Mini is likely attributable to a lower proportion of Classical Chinese in its training data, making it difficult to effectively handle the concise expressions and cultural context inherent in the language.

Verification of the multi-agent method’s enhancement effect

To validate the enhancement effect of the multi-agent method, each baseline model was integrated into the proposed MAS, and the performance difference before and after integration was compared across metrics like BLEURT. Table 3 presents the performance of each model after being enhanced by the multi-agent method. Figure 9 visually illustrates the percentage improvement in translation quality achieved by the multi-agent method, providing a clearer view of its optimization effect.

By comparing the data in Table 2 and Table 3, combined with Fig. 9, the following analytical conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

Significant and comprehensive performance improvement across models: The multi-agent method led to substantial gains for all baseline models across various metrics. Enhanced Semantic Understanding and Accuracy: The average BLEURT score increased by 18.8% (from a baseline average of 0.526 to 0.625 post-integration), indicating that the MAS significantly bolstered the models’ ability to grasp the semantics of Classical Chinese. Improved Lexical Conversion Precision: The average BLEU-1 score improved by 21.5% (from 0.381 to 0.463), confirming that the method enhances lexical accuracy in translations, likely aided by the precise conversion capabilities of the \(A_{WT}\). Largest Gain in Semantic Consistency: The METEOR score saw the most substantial average improvement, increasing by 25.7% (from 0.358 to 0.450). This highlights the method’s exceptional capability in maintaining semantic fidelity. Improved Structure and Fluency: The ROUGE metrics showed average improvements ranging from 3.6% to 7.5%, demonstrating that the multi-agent method effectively enhances the structural integrity and fluency of the translated text.

-

(2)

Gradient effect in performance improvement: Observing the individual model performance gains depicted in Fig. 9, it is evident that the magnitude of improvement provided by the multi-agent method generally increases as the baseline performance of the model decreases. For instance, the GPT-4o Mini model, the weakest baseline, achieved the highest relative improvement (e.g., 27.9% gain in BLEURT). Conversely, the top-performing baseline, DeepSeek V3, saw a smaller relative gain (e.g., 2.8 This ’gradient effect’ suggests that the multi-agent method provides complementary capabilities tailored to the deficiencies of the base model, demonstrating the method’s adaptive nature. Notably, even for the best-performing baseline (DeepSeek V3), the multi-agent method still achieved a substantial 18.4% improvement on the ROUGE-2 metric. This gain is significantly above the average improvement level observed for ROUGE metrics across all models, indicating that the MAS can still markedly enhance translation quality even when applied to strong baseline models, particularly concerning aspects like bigram overlap captured by ROUGE-2.

-

(3)

Significant enhancement in translation stability: The improvement in translation stability is also evident when comparing the standard deviations before and after MAS integration. Comparing the standard deviation values in Table 2 and Table 3, it is observed that the standard deviations for all models generally decreased after integration with the multi-agent method, with an average reduction of 12.7%. For example, as depicted in Fig. 10, the BLEU-1 standard deviation for GPT-4o Mini decreased from 0.197 to 0.159, and the BLEURT standard deviation for Qwen Plus dropped from 0.178 to 0.125. This demonstrates that the multi-agent method not only improves the average translation quality but also enhances the consistency and reliability of the translation results.

-

(4)

Analysis of technical drivers for metric improvements: BLEURT: The improvement in BLEURT primarily stems from the method’s enhancement of semantic accuracy. Corrections made by the \(A_{RW}\) reduced mistranslations of cultural allusions and polysemous words. Concurrently, the application of the \(A_{RG}\) significantly lowered grammatical errors, further boosting semantic fidelity. BLEU-1 and ROUGE: The gains in BLEU-1 and the ROUGE series metrics are attributed to the synergy between the \(A_{WT}\) and the interpretation database, which markedly improved lexical-level matching precision. METEOR: The substantial increase in the METEOR score is largely due to the multi-round review mechanism, especially the contribution of the \(A_{RC}\). This agent effectively addressed the issue of logical disruptions commonly observed in text generation by single models.

Overall, the experimental results robustly validate the technical advantages of the multi-agent method for Classical Chinese translation. By leveraging task decomposition and agent collaboration, this approach effectively overcomes the limitations of single models in handling the unique multi-layered semantic structures and cultural connotations inherent in Classical Chinese. It thus offers a new methodological paradigm for complex language translation. The demonstrated adaptability, stability, and comprehensive performance enhancements of the multi-agent method not only address the issues of semantic distortion and stylistic inconsistency prevalent in traditional Classical Chinese translation but also provide reliable technological support for the digital dissemination of cultural heritage.

Human evaluation

To complement automatic metrics, we conducted a human evaluation on three dimensions: Fluency, Adequacy, and Cultural Fidelity. All dimensions use five-point Likert scales with anchors (1 = poor, 3 = acceptable, 5 = excellent).

We selected two representative models from our experiments: DeepSeek V3 (strongest single-model baseline) and GPT-4o Mini (weakest baseline). For each model, we evaluated both the Single-Model Baseline and the version integrated into our Multi-Agent Framework. A total of 100 sentences were randomly sampled from the test set (balanced by chapter and length). Three bilingual annotators (Classical and Modern Chinese) rated each item in a double-blind, randomized setting after a short calibration round. Scores were averaged over annotators; we report mean ± standard deviation across items.

As shown in Table 4, for DeepSeek V3, the multi-agent framework yields consistent gains across all three dimensions, with the largest improvement in Cultural Fidelity (+0.48). For GPT-4o Mini, improvements are more pronounced: Cultural Fidelity +0.96, Adequacy +0.67, and Fluency +0.47. These results align with our automatic metrics and show larger relative benefits for weaker baselines.

Ablation study

To dissect the framework and quantify the contribution of its core components, we conducted an ablation study. This analysis isolates the impact of individual agents and mechanisms by systematically removing them from the full system. We used the GPT-4o Mini model as the backbone for this study, as it exhibited one of the most significant performance gains, making it an ideal case for examining the sources of improvement. The results are presented in Table 5.

The ablation study results, detailed in Table 5, allow for a quantitative assessment of each component’s contribution to the overall performance of the MAS framework. The analysis clearly reveals that the system’s strength lies in the synergistic collaboration of its agents, as the removal of any single component leads to a substantial decline in quality.

-

(1)

Quantifying the impact of the expert review module: The three review agents are critical for refining the initial translation.

-

Removing the contextual coherence review agent (\(A_{RC}\)): This action triggers the most severe performance collapse, causing the BLEURT score to plummet by 27.2% (from 0.596 to 0.434), falling below the single-model baseline (0.466). The METEOR score regresses by 33.4% (from 0.362 to 0.241), effectively nullifying all gains in semantic and ordering consistency. This quantifies the \(A_{RC}\)’s indispensable role in ensuring logical flow and contextual integrity, which is a primary weakness of single-pass generation models.

-

Removing the grammatical structure validation agent (\(A_{RG}\)): The impact is similarly drastic. The BLEURT score drops by 27.2% (to 0.434), and the METEOR score sees the largest degradation of all ablations, falling by 41.7% (from 0.362 to 0.211). This explicitly demonstrates that the \(A_{RG}\) is fundamental for producing fluent, grammatically correct translations that align with modern linguistic norms.

-

Removing the key word review agent (\(A_{RW}\)): Disabling this agent results in a 10.1% drop in the BLEURT score (from 0.596 to 0.536) and a 40.9% drop in the METEOR score. This highlights the \(A_{RW}\)’s crucial function as a semantic safeguard, correcting nuanced errors related to polysemy and cultural terms that the initial translation agent might miss.

-

-

(2)

Quantifying the impact of keyword interpretation: Removing the entire keyword interpretation pipeline (\(A_{WT}\) + DB) cripples the system, causing a 25.2% decrease in the BLEURT score (from 0.596 to 0.446) and a 32.3% decrease in METEOR. The impact is particularly notable on ROUGE-2, which drops by 16.7%. This quantifies the foundational importance of grounding the translation in accurate lexical knowledge retrieved via RAG. Without this step, subsequent agents operate on a flawed premise, making high-quality output unattainable.

-

(3)

Synergistic effect of collaboration: The analysis unequivocally demonstrates that the framework’s 27.9% overall BLEURT improvement over the baseline is not an additive sum of individual contributions but a product of their synergy. The initial translation from \(A_{PT}\) (informed by \(A_{WT}\)) provides a strong draft, which is then polished by the multi-faceted review process (\(A_{RC}\), \(A_{RW}\), \(A_{RG}\)). Each agent’s isolated impact is significant, but their collective, iterative operation is what enables the system to overcome the complex, multi-layered challenges of Classical Chinese translation.

Computational efficiency analysis

While our MAS framework demonstrates significant improvements in translation quality, these gains are accompanied by increased computational cost. To provide insights into the practical feasibility of our method, we analyzed its time cost. The analysis was conducted on a randomly selected sample of 24,747 characters from the test set, using the GPT-4o Mini as the backbone LLM. The results are detailed in Table 6.

Analysis: The results reveal a clear trade-off between translation quality and computational cost. The complete MAS framework requires approximately 3.21 times the processing time of the baseline single-model approach. This overhead is primarily attributable to two factors: the multi-agent communication and the multiple inference calls to the LLM.

A breakdown of the component costs yields further insights:

Keyword Interpretation is the Main Bottleneck: Removing the keyword interpretation pipeline (\(A_{WT}\) and its database) results in the most significant time reduction, decreasing the total time by 9,366 seconds (a 39.5% reduction from the complete system). This indicates that the RAG-based initial semantic parsing, which involves database queries and dedicated LLM calls, is the most time-intensive single component within the framework.

Iterative Review Adds Incremental Cost: The three expert review agents (\(A_{RC}\), \(A_{RG}\), \(A_{RW}\)) collectively account for a smaller portion of the overhead. Removing the grammatical (\(A_{RG}\)) or contextual (\(A_{RC}\)) review agents saves 1,538s and 753s, respectively. The near-identical time for the system with and without the keyword review agent (\(A_{RW}\)) suggests that the time cost of a single review step is relatively minor compared to the overall processing, and small variations can be attributed to network or inference latency fluctuations.

It is crucial to note that these figures are indicative and highly dependent on external factors such as network speed and the LLM provider’s inference service load. Nevertheless, the analysis shows that while our method introduces a quantifiable computational cost, this cost is a direct result of the structured, multi-step process that ensures higher fidelity. For applications where quality, accuracy, and cultural resonance are paramount–such as the digital preservation of cultural heritage–this trade-off is often justifiable.

Empirical analysis

To further validate the practical efficacy of the proposed method in the Classical Chinese translation task, this section conducts a multi-dimensional analysis of typical case studies from The Records of the Grand Historian of China: The Hereditary Houses and the Biographies, Volume 7–10. The DeepSeek V3 model was integrated into the multi-agent method. The translation results generated by this integrated system are compared against both baseline model outputs and human reference translations, using evaluation metrics like BLEURT alongside qualitative assessment, to analyze the technical advantages stemming from the multi-agent collaborative mechanism.

Comparative analysis of translation instances

Table 7 presents an analysis of the famous ”Returning the Jade Intact to Zhao” (完璧归赵) segment from the ”Biographies of Lian Po and Lin Xiangru” (《廉颇蔺相如列传》).

Comparing the three translations reveals several distinct advantages of the multi-agent method over the baseline model:

Accurate Conveyance of Cultural Connotation: The baseline model simply translates ”璧” as ”玉璧” (jade disc), whereas the multi-agent method accurately identifies that ”璧” here specifically refers to the historical artifact ”和氏璧” (He Shi Bi), consistent with the manual reference translation. This reflects the synergy between the \(A_{WT}\) and the Key Word Interpretation Database, further validating the method’s effectiveness in conveying cultural nuances.

Improved Semantic Coherence: In the multi-agent method’s translation, ”赵王惧怕秦国的强大” (King of Zhao feared the might of Qin) expresses the original intent more completely than the baseline model’s ”赵王害怕秦国” (King of Zhao feared Qin) by adding the reason for the fear.

Natural and Fluent Expression: In the dialogue part, the multi-agent method translates ”若何” as ”那该怎么办” (Then what should be done?), which is more natural in tone and contextual adaptation compared to the baseline model’s ”怎么办” (What to do?), aligning better with modern Chinese expression habits. This improvement benefits from the effective work of the \(A_{RC}\), which optimizes the translation result by analyzing the context, ensuring fluency and accuracy.

Systematic error analysis and mitigation strategies

Although the multi-agent method significantly improves translation quality, it is not without limitations. To better understand its failure modes, we conducted a systematic error analysis on a random sample of 200 translated sentences from the test set. Errors were manually categorized into four distinct types. The distribution and a qualitative analysis are presented below, using examples from the ”Treatise on the Distribution of Wealth” (《货殖列传》) (see Table 8).

-

1.

Lexical and terminological errors (42%): These are the most frequent errors, typically involving the mistranslation of specific nouns, archaic terms, or culturally-specific items. For example, translating ”鲍” as ”鲍鱼” (abalone) instead of its correct historical meaning, ”腌咸鱼” (salted/cured fish).

Cause: Gaps in the Key Word Interpretation Database or the LLM’s inability to select the correct context-specific meaning from multiple candidates.

Mitigation Strategy: Continuously enrich the database with more domain-specific knowledge (e.g., ancient economics, geography, and customs). Implement a disambiguation mechanism where the \(A_{RW}\) can flag low-confidence interpretations for further verification.

-

2.

Cultural Misinterpretation (25%): This category includes errors where the literal translation is correct, but the deeper cultural allusion or connotation is lost. For example, translating ”璧” as a generic ”玉璧” (jade disc) instead of the historically significant ”和氏璧” (He Shi Bi) in the context of the Lian Po biography. While our system often handles this correctly, occasional failures highlight the challenge.

Cause: Lack of deep, structured cultural knowledge beyond what is available in standard text corpora.

Mitigation strategy: Integrate the framework with a formal knowledge graph focused on ancient Chinese history and culture. This would allow agents to retrieve not just definitions but also relational context.

-

3.

Syntactic and fluency issues (18%): These errors pertain to awkward phrasing or grammatical structures that, while understandable, deviate from natural Modern Chinese. For example, overly literal translations of Classical Chinese sentence patterns that result in stilted prose.

Cause: The \(A_{RG}\) may over-prioritize faithfulness to the source syntax, or the base LLM may have inherent stylistic biases.

Mitigation strategy: Refine the prompts for the \(A_{RG}\) to place greater emphasis on idiomatic expression and fluency, perhaps by providing it with examples of high-quality, elegant translations.

-

4.

Semantic incoherence (15%): This refers to cases where the local translation is accurate, but the overall logical flow or semantic consistency with adjacent sentences is disrupted. This was less common due to the \(A_{RC}\) but still occurred in highly complex narrative passages.

Cause: The contextual window provided to the \(A_{RC}\), while global, may not always be sufficient for resolving very long-range dependencies or subtle shifts in narrative tone.

Mitigation strategy: Enhance the memory module (M) to include not just previous translations but also a running summary of key events, characters, and relationships, providing the \(A_{RC}\) with a richer contextual model.

This systematic analysis provides a clear roadmap for future improvements, focusing on targeted knowledge enrichment and more sophisticated agent capabilities.

Conclusion

This work presents an LLM-driven multi-agent Classical Chinese translation framework that addresses the semantic, syntactic, and cultural limitations of conventional approaches. By modularizing translation into generation, keyword interpretation, contextual review, and grammatical validation, the method achieves substantial quality gains—18.8–25.7% across BLEURT, BLEU-1, and METEOR—while improving stability by \(\sim\)12.7%.

Human evaluation confirms benefits in fluency, adequacy, and cultural fidelity, especially for weaker baselines. Ablation studies show the indispensable roles of each agent, particularly in ensuring contextual coherence and grammatical accuracy.

Efficiency analysis reveals a trade-off: compared with the framework without useful agents, the running time of the proposed method increases by 3.21 times, primarily from the keyword interpretation stage, which is justified in contexts prioritizing fidelity over speed.

While this study focuses on Classical Chinese, the framework has broad potential for other historical or low-resource languages, such as Sanskrit or Latin. The modular design–decomposing translation into distinct tasks–is language-agnostic. Adapting it involves building language-specific Key Word Interpretation Databases and tailoring expert agents to the syntactic features of the target language. This flexibility makes the framework a robust blueprint for high-fidelity translations across diverse linguistic domains.

Despite its success, challenges remain in handling specialized terminology, ancient units, and complex cultural references. Future work will focus on expanding knowledge bases, refining cultural context modeling, and optimizing agent collaboration, ensuring that the framework can effectively preserve and disseminate cultural heritage in a variety of languages.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during this study are publicly available in the GitHub repository for this project at https://github.com/Anthemy/A-Multi-Agent-Classical-Chinese-Translation-Method

References

Zhang, K. et al. Dual channel semantic enhancement-based convolutional neural networks model for text classification. Int. J. Mod. Phys. C 36, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0129183124420129 (2025).

Raiaan, M. A. K. et al. A review on large language models: Architectures, applications, taxonomies, open issues and challenges. IEEE Access 12, 26839–26874. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3365742 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Recent advances in interactive machine translation with large language models. IEEE Access 12, 179353–179382. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3487352 (2024).

Dorri, A., Kanhere, S. S. & Jurdak, R. Multi-agent systems: A survey. IEEE Access 6, 28573–28593. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2831228 (2018).

Hutchins, J. Machine translation: A concise history. Comput. Aided Trans. Theory Pract. 13, 11 (2007).

Och, F. J. & Ney, H. Discriminative training and maximum entropy models for statistical machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (eds Isabelle, P. et al.) 295–302 (Association for Computational Linguistics, Philadelphia, 2002). https://doi.org/10.3115/1073083.1073133.

Elman, J. L. Finding structure in time. Cogn. Sci. 14, 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15516709cog1402_1 (1990).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735 (1997).

Cho, K. et al. Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv:1406.1078) (2014.

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 30 (eds Guyon, I. et al.) (Curran Associates Inc., New York, 2017).

Zhang, Z., Li, W. & Su, Q. Automatic translating between ancient Chinese and contemporary Chinese with limited aligned corpora. In Natural Language Processing and Chinese Computing (eds Tang, J. et al.) 157–167 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2019).

Liu, D., Yang, K., Qu, Q. & Lv, J. Ancient-modern Chinese translation with a new large training dataset. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inf. Process https://doi.org/10.1145/3325887 (2019).

Tian, H., Yang, K., Liu, D. & Lv, J. AnchiBERT: A pre-trained model for ancient Chinese language understanding and generation. In 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/IJCNN52387.2021.9534342(2021).

Cao, J. et al. TongGu: Mastering classical Chinese understanding with knowledge-grounded large language models. arXiv:2407.03937 (2024).

Chen, A. et al. Large language models for classical Chinese poetry translation: Benchmarking, evaluating, and improving. arXiv:2408.09945 (2024).

Zhang, Y. & Li, H. Can large language model comprehend ancient Chinese? A preliminary test on Aclue. arXiv:2310.09550 (2023)

Cao, J., Shi, Y., Peng, D., Liu, Y. & Jin, L. \({\rm C}^{3}\)bench: A comprehensive classical Chinese understanding benchmark for large language models . arXiv:2405.17732 (2024).

Reed, S. et al. A generalist agent. arXiv:2205.06175 (2022).

Srinivasan, D. Innovations in Multi-Agent Systems and Application-1 Vol. 310 (Springer, New York, 2010).

Liang, T. et al. Encouraging divergent thinking in large language models through multi-agent debate. arXiv:2305.19118 (2024).

Chowdhury, S. & Soni, B. QSFVQA: A time efficient, scalable and optimized VQA framework. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 48, 10479–10491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13369-023-07661-8 (2023).

Lewis, P. et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 33 (eds Larochelle, H. et al.) 9459–9474 (Curran Associates, Inc., New York, 2020).

DeepSeek-AI, Liu, A., Feng, B. et al. Deepseek-v3 technical report . arXiv:2412.19437 (2025)

Papineni, K., Roukos, S., Ward, T. & Zhu, W.-J. Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 311–318 (2002).

Lin, C.-Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Text summarization branches out, 74–81 (2004).

Banerjee, S. & Lavie, A. Meteor: An automatic metric for mt evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments. In Proceedings of the ACL workshop on intrinsic and extrinsic evaluation measures for machine translation and/or summarization, 65–72 (2005).

Sellam, T., Das, D. & Parikh, A. P. Bleurt: Learning robust metrics for text generation . arXiv:2004.04696 (2020).

Lee, S. et al. A survey on evaluation metrics for machine translation. Mathematics 11, 1006. https://doi.org/10.3390/math11041006 (2023).

Funding

This work was supported by the project ”Research on Personalized Recommendation of Mobile Reading Based on Fusion of Multi-Source Heterogeneous Data” (Project No. 2023CJR032) funded by Chongqing Municipal Education Commission.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.L. conceived the experimental methodology, conducted the primary investigation and data acquisition, performed the experimental data analysis, and generated the initial drafts of the manuscript. Q.C. contributed to the conceptualization of the research, secured funding for the project, acquired essential research resources, validated and verified the experimental design, and provided supervision and guidance throughout the research process. Additionally, Q.C. critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. X.L. provided supervision and guidance for the research project and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final manuscript review and approved the submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lv, W., Cao, Q. & Liu, X. A multi agent classical Chinese translation method based on large language models. Sci Rep 15, 40160 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23904-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23904-0