Abstract

This article explores the three-dimensional thermoelastic problem in a homogeneous, isotropic rectangular plate subjected to an external heat source and an electromagnetic field under three theories: nonlocal classical coupled dynamical theory (NLCDC), nonlocal Lord-Shulman theory (NLLS), and nonlocal dual phase-lag theory (NLDPL). Normal mode analysis is applied to the governing equations and employs the eigenvalue approach methodology to obtain an analytical closed-form solution. Comparative numerical differentiations are performed for three different semiconductors: Silicon (Si), Germanium (Ge), and Gallium Arsenide (GaAs). The results are presented graphically in both two-dimensional and three-dimensional formats based on fixed physical parameters of the three semiconductors. The results reveal the significant effects of the comparisons across the three theories, the heat source, electromagnetic field, and thermoelastic coupling parameter, which are influenced by the non-local theory with ultra-short thermoelastic response. Different values of energy band gap \((E_g)\) for the three semiconductors (Si, Ge, and GaAs) produce more pronounced characteristics for the variations in thermoelastic properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In modern electronic theory and photothermoelasticity, both the effect of thermoelasticity and magnetoelasticity is required. The interactions between thermal, mechanical, and optical effect can be countered to get a more accurate performance. Semiconductors and intrinsic semiconductors have a wide range of applications in modern electronics devices. This technology is based on the analysis of all the significant properties of Si, Ge, GaN, GaAs and InP which are used mainly in high-frequency optoelectronic devices. The small amount of impurities or dopants, such as phosphorus (P), antimony (Sb), arsenic (As), etc., causes it to be a conductor, and different types of dopants make it n-type or p-type conductors. This type of semiconductor is extensively used in diodes, integrated circuits (ICs) and many modern electronic gadgets. In the presence of an electromagnetic field, the Lorentz force plays a significant role in interacting between the electromagnetic field, strain, stress components, and temperature distribution in an electromagnetothermoelastic medium. This type of interactions have many applications such as tectonic plate theory in geophysics, plasma physics, theory of wave propagation in thermal and electrical engineering field. Different types of energy bands of the semiconductor are illustrated in Fig. 1b. The energy band theory mainly describes the characteristics of semiconductors and insulators. Mustafi1 investigated that the energy band gap (Eg) depends on the temperature, the density of the dopant and the carrier density of the semiconductors or intrinsic semiconductors. Recently, Kumar et al.2 investigated the behaviour of photothermal waves in a semiconducting medium using the dual phase lag (DPL) thermoelasticity theory with nonlocal effects. Ahmed et al.3 proposed a novel nonlocal mathematical model for thermo-photo-elasticity to address the limitations of classical theories in understanding the interactions between thermal, mechanical, and photoelastic deformations in semiconductors like silicon and germanium. Zenkour4 developed a system of four coupled thermoelastic differential equations incorporating a photothermal process. The study presented the refined multiphase-lag (RPL) theory to describe the thermoelastic photothermal response of a half-space semiconducting medium. Othman et al.5 investigated the coupled two-dimensional magneto-thermoelastic problem of a thermally perfect conducting half-space solid in the presence of a moving internal heat source. Mahdy et al.6 studied the one-dimensional deformation of a semiconducting elastic medium subjected to a strong magnetic field with Hall current. The study also accounted for the effect of micro-temperature when a laser beam was applied to the outer surface of the medium. Alqahtani7 introduces the analytical solution for thermal, elastic, and plasma waves generated by focused laser beams in semiconductor materials. Salah et al.8 studied the effects of magnetic fields and initial stress on a rotating semiconductor medium with ramp-type heating subjected to specific boundary conditions.

Traditionally, the theory of elasticity states the mathematical expression to determine the stress and strain of the medium. Biot9 introduced the classical coupled thermoelasticity(CCTE) theory which is based on the conventional Fourier’s law of heat conduction under a high temperature environment. Later, generalized thermoelastic theories: Lord and Shulman (LS)10 theory, Green-Lindsay (GL)11 theory, and Green-Naghdi12,13,14 theory modified the basic paradoxes of conventional theory. Basically, the dissipative theory of energy proposed by Green-Nagdi12,13 predicts a more appropriate model of mechanical and thermal situations where precision and optimal performance are required. High energy gradient machine, laser heating tools, nuclear reactor, etc. where the heat propagation with finite speed and energy dissipation is more crucial. Othman et al.15 studied generalized thermoelasticity using the Lord–Shulman theory with one relaxation time to examine photothermal wave behavior in a semiconducting medium. Lotfy et al.16 investigated the basic characteristics of plane wave propagation in the presence of an electromagnetic field that addresses the problem of two temperatures for a semi infinite two-dimensional semiconducting medium. Othman et al.17 investigated the influence of gravity in a homogeneous, isotropic semiconducting medium with an internal heat source, employing the Lord–Shulman thermoelastic theory.

Conventional theory fails to give the accuracy for low-temperature scenarios and finite speed of wave propagation which disturb to reach the equilibrium condition. Generally, it pursues the local elastic effect, which is effectively used for primary interactions on the macroscopic scale of the material, regardless of the size effect. Eriengen18 introduced a new theory that includes the size effect and non-locality. Islam et al.19 investigated the thermoelastic and electromagnetic effects for a thin circular semiconductor, considering this structural size and Eringen’s non-local elastic theory (ENET). This theory of non-locality addresses the long-range interactions between the particles of the material. The non local Lord-Shulman(NLLS) theory creates a comprehensive model that effectively captures both nonlocal mechanical effects and realistic thermal wave propagation. This unified approach is particularly beneficial for analyzing the thermomechanical behavior of materials where small-scale effects and finite thermal propagation speeds are crucial for a nano-scale composite material structures. The nonlocal dual phase lag theory (NLDPL) is an advanced framework in heat conduction that integrates nonlocal elasticity concepts with the dual phase lag (DPL) heat conduction model. This theory addresses the limitations in classical heat conduction models, particularly at the micro and nano-scales, by considering both spatial nonlocality and temporal phase lags in heat flux and temperature gradient responses. Elaziz et al.20 analyzed the propagation of plane waves in a nonlocal semiconductor nanostructure thermoelastic solid incorporating a fractional derivative, under the influence of a ramp-type heat source. Othman et al.21 investigated the impact of temperature-dependent parameters and initial stress on semiconductor materials within the framework of the dual-phase lag (DPL) model. Tzou22 has introduced a fascinating theory of dual-phase-lag heat equations that includes two phase-lag parameters related to the temperature gradient and the heat-flux vector. The NLDPL theory has been used to study thermoelastic damping in micro and nano-scale structures, such as nano-beams and nano-plates. By considering size-dependent effects, this theory provides valuable insights into the mechanisms of energy dissipation that are crucial for designing micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) resonators. Dali et al.23 examined a coupled thermoelastic model incorporating the interactions of thermal, mechanical, and energy fields in a three-dimensional medium.

In this paper, we study the generalized thermoelasticity theory of non-local heat conduction considering the effects of a heat source and electromagnetic field components in a three-dimensional rectangular semiconducting medium. The fundamental governing equations are formulated in the three-dimensional thick plate within the framework of the non-local thermoelastic theory. We have also derived physical quantities such as temperature distribution, carrier density, stress and displacement components using the normal mode analysis and eigenvalue approach methodology. Several two and three-dimensional graphs show the analytical results for three semiconductors such as silicon(Si), germanium(Ge) and gallium arsenide(GaAs) by using MATLAB 2021a programming language. The corresponding discussions are depicted systematically. The results reveal a significant impact for comparing the three theories, applied external heat source, electromagnetic field, and thermoelastic coupling parameter. Also, compares the physical quantities based on different values of material constants for three different semiconductors. This study presents a nonlocal magneto-thermoelastic model based on an isotropic and homogeneous three-dimensional rectangular semiconducting medium, ensuring that both thermal and mechanical boundary conditions are satisfied. The problem is investigated within the framework of nonlocal thermoelasticity theory under three models (NLCDC, NLLS, and NLDPL) in the presence of an external heat source and magnetic field.

Basic equations for theoretical model

We consider a generalized, homogeneous, and isotropic thermoelastic rectangular semiconductor in the presence of the initial magnetic field \(H_0\) directed along the \(z\) axis, along with an applied external heat source \(Q\). The physical field variables are defined in terms of the Cartesian coordinates \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\), as well as time \(t\).

As discussed in Islam et al.[19] and Todorovic24 19, the coupled plasma equation and equation of motion for a homogeneous and isotropic semiconductor are given as:

where N(x, y, z, t) represents the carrier density, \(D_E\) is the carrier diffusion coefficient. Here, \(\theta\) and \(\theta _0\) denote the absolute temperature and reference temperature of the material, respectively. The term \(\kappa _1\) ( \(=\frac{\partial N_0}{\partial \theta } \frac{\theta }{\tau })\) represents the thermal activation coupling parameter. Additionally, \(N_0\) and \(\tau\) refer to the carrier concentration with reference temperature \(\theta _0\) and the photo-generated carrier lifetime, respectively.

The equation of motion for an isotropic semiconductor medium with an electromagnetic field is given by

The components of the Lorentz force is given by \(\mathbf {F_{i}} = \mu _{0} (\textbf{J} \times \textbf{H})_{i}\), where \(\textbf{H}\) is the magnetic field vector and \(\textbf{J}\) is the electric current density. The mass density is represented by \(\rho\). The parameters \(\lambda\) and \(\mu\) refer to Lame’s constants, while \(\alpha = (3\lambda + 2\mu ) \alpha _{\theta }\) is known as the thermoelasticity constant. Here, \(\alpha _{\theta }\) represents the coefficient of linear thermal expansion. Additionally, \(\delta _n\) denotes the difference between the conduction and valence bands.

As in Islam et al.19 and Das et al.25, the non-local heat transportation equation with the presence of the heat source is given as

In this context, \(\kappa\) denotes the thermal conductivity. The parameters \(\tau _{\theta }\) and \(\tau _q\) denote the phase lags of the temperature gradient and heat flux, respectively. The symbol \(\lambda _{q_{k}}\) signifies the non-local parameter. Additionally, \(E_g\) refers to the energy bandgap, while \(C_e\) indicates the specific heat. Lastly, Q represents an external heat source.

The constitutive stress components are as follows:

where \(\sigma _{ij}\) and \(e_{ij}\) represent the component of the stress and strain tensor, \(e=(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}+\frac{\partial v}{\partial y}+\frac{\partial w}{\partial z})\) is the cubical dilatation.

In the presence of an electromagnetic field, the medium must follow Maxwell’s equations as in Baltz26 as-

In this context, \(\mu _{0}\) and \(\epsilon _{0}\) represent the magnetic and electric permeability respectively. The vector h indicates the induced magnetic field component, while E signifies the induced electric field component expressed as E = \((E_1, E_2, 0)\).

In this works, the nonlocal heat transportation Eq. (3) presents three distinct theories as discussed in Das et al.27:

-

(i)

Non-local classical dynamical coupled (NLCDC) theory: this theory is characterised by \(\tau _{\theta } = \tau _{q} = 0\) and \(\lambda _{q} > 0\).

-

(ii)

Non-local Lord and Shulman (NLLS) theory: it is defined by \(\tau _{\theta } = 0\), \(\tau _{q} > 0\), and \(\lambda _{q} > 0\).

-

(iii)

(iii) Non-local dual phase lag (NLDPL) theory: the conditions are \(\tau _{q} \ge \tau _{\theta } > 0\) and \(\lambda _{q} > 0\).

Validation of our model compared to other models

-

(a)

Neglecting the chemical concentration (C) and the presence of external heat source (Q) :

-

For an isotropic, homogeneous, and perfectly thermoelastic thin semiconductor, the theoretical framework proposed in this article aligns with the approach presented by Islam et al.19. In this context, no external body forces are considered, and all thermal and mechanical interactions are assumed to depend solely on the radial distance.

-

-

(b)

Neglecting the heat source \(( Q = 0)\) and the carrier density\((N = 0)\):

-

If we focus on the problem of the generalized magnetothermoelastic problem with non-local theory and in the absence of an external heat source(Q) and carrier intensity(N) for the isotropic and homogeneous elastic material, then the theory proposed in this article is identically similar with Das et al.25.

-

-

(c)

Neglecting the heat source \(( Q = 0)\) and displacement \((w=0)\):

-

If we consider a two-dimensional generalized magnetothermoelastic problem with non-local theory and in the absence of an external heat source for the semiconductor silicon only, this proposed theory is similar with Sardar et al.27.

-

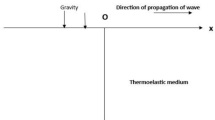

Formulation of the problem

We consider a rectangular thick semiconductor plate which is isotropic, homogeneous, and exhibits magneto-thermoelastic behaviour. The plate occupies the region: R=\(\lbrace\)(x, y, z): \(0 \le x\le h\); \(0\le y\le c\); \(0\le z\le d\) \(\rbrace\) with a magnetic field as shown in Fig. 1a. The total magnetic field, denoted as \({\textbf {H}}\) consists of an initial uniform magnetic field \(H_0\) and a perturbation h. The initial magnetic field \(\mathbf {H_0}\)=\({(0, 0, H_{0})}\) is applied in the direction of the z-axis in the cartesian coordinate system.

Therefore, from Eq. (5), we have the expression of Lorentz forces such as

(a) Schematic representation of an isotropic and homogeneous thermoelastic semiconductor with finite height (\(x=h\)) in the presence of an external heat source (Q) and magnetic field \((H_{0})\). (b) Typical energy band diagram of a crystalline semiconductor. Specifically, \(E_g\) plays a crucial role in characterising the intrinsic semiconductors into conductors by decreasing the electrical resistance.

The equation of the dimensionless variable is given as

Using Eqs. (6), (7), (8), and dimensionless Eq. (9), the basic Eqs. (1)–(4) can be written as

The constitutive dimensionless equations of the stress components are as follows-

where, \(\alpha ^2_{0}=(\frac{\rho +\epsilon _{0}\mu ^2_{0}H^2_{0}}{\mu })c^2_{0},\)\(\beta ^2_{0}=(\frac{\lambda +2\mu +\mu _{0}H^2_{0}}{\mu }),\)\(\beta ^2=\frac{\rho {c^2_{0}}}{\mu }=(\frac{\lambda +2\mu }{\mu }),\)\(c^2_{0}=(\frac{\lambda +2\mu }{\rho }),\)\(\eta _{0}=\frac{\rho c_e}{\kappa },\)\(\epsilon _1=\frac{\alpha ^2 \theta _{0}}{\rho ^2 c_{e} c^2_{0}},\)\(\epsilon _{2}=\frac{\alpha E_{g}}{\kappa \delta _{n} {c_0}^2 {\eta _0}^2 \tau },\)\(q_2=\frac{1}{D_E \eta _0}, q_1=\frac{1}{D_E {c_0}^2 {\eta _0}^2 \tau },\)\(\epsilon _3 = \frac{k_1 \delta _n}{D_E {c_0}^2 {\eta _0}^2 \alpha }\).

In this context, the parameters are defined as follows: \(\epsilon _1\) is the thermo-elastic coupling parameter that depends on thermal expansion \(\alpha\), \(\epsilon _2\) is the thermo-energy coupling parameter derived from the energy band gap of the semiconductor. Lastly, \(\epsilon _3\) represents the thermoelectric coupling parameter which is based on the coefficient of electronic deformation(ED). These parameters are essential for understanding the different physical interactions in materials under various circumstances.

Solution procedure: normal mode analysis

To get the physical field variables analytically, we now apply the normal mode analysis which is defined as follows-

where \(\xi (x, y, z, t)=[N, u, v, w, \theta , \sigma _{ij}]\), \({\xi }^*(x)=[N^*, u^*, v^*, w^*, \theta ^*, \sigma ^*_{ij}]\), s is the angular frequency, \(i=\sqrt{-1}\), a and b are the wave numbers in the directions of y and z axis respectively.

Using Eq. (21), the non-dimensional basic Eqs. (10)–(14) can be expressed in the form of a vector matrix differential equation as follows:

where, \(D=\frac{d}{dx}\), V=\([N\mathrm{\; \; \; } u \mathrm{\; \; \; }v \mathrm{\; \; \; }w \mathrm{\; \; \; }\theta \mathrm{\; \; \; }\)\(\frac{dN}{dx}\mathrm{\; \; \; } \frac{d u}{d x} \mathrm{\; \; \; \; } \frac{d v}{d x} \mathrm{\; \; \; }\)\(\frac{d w}{d x} \mathrm{\; \; } \frac{d\theta }{d x} ]^{T}\), A = \(\left[ \begin{array}{cc} {L_{11} } & {L_{12} } \\ {L_{21} } & {L_{22} } \end{array}\right]\), \(f=\)\([0\mathrm{\; \; \; }0 \mathrm{\; \; \; }0 \mathrm{\; \; \; }0 \mathrm{\; \; \; }0\)\(\mathrm{\; \; \; }0 \mathrm{\; \; \; }0 \mathrm{\; \; \; }0\mathrm{\; \; \; } 0\mathrm{\; \; \; }\)\(C_{1011}]^{T}\), \(L_{11}\) is null matrix, \(L_{12}\) is identity matrix of order \(5\times 5\), the mathematical expressions for \(L_{21}\), \(L_{22}\), and \(c_{1011}\) are given an Appendix.

We now apply the eigenvalue approach methodology to solve the vector matrix differential Eq. (22). The characteristic equation of the coefficient matrix A is as follows-

where \(X=[X_{j}]_{j=(1(1)10)}\) is the eigenvectors corresponding to the eigenvalues \(\lambda =\lambda _{j}\) for \(j=1(1)10\). These eigenvalues are obtained by solving the characteristic Eq. (23) using MATLAB R2021a. The computation involves the built-in functions of MATLAB to determine the eigenvalues and their associated eigenvectors.

As the corresponding theory is discussed in Das et al.28 and considering the regularity condition, the general solution of the differential Eq. (22) for a rectangular plate is

where,

where \(A_{j}\)’s are the arbitrary constants.

Thus, the corresponding values of the physical field variables can be written as -

Using this solution, Eqs. (15–20) give the expression of stress components which are given by

The arbitrary constants \(A_{j}\)’s (j=1(1)10) are to be determined from the prescribed boundary conditions. The explicit expressions of \(R_{ij}(i=1(1)6)\) and \(d_k (k= 1(1)6)\) are given in the Appendix.

Initial and boundary conditions

To determine the arbitrary constants \(A_j\), we now examine the initial and boundary conditions for the rectangular plate with height \(h\) as illustrated in Fig. 1a. The thick rectangular plate of semiconducting medium is subjected to: Case-I - a known magnitude of load and carrier intensity gradient at the top surface, Case-II - an exponential order increase in mechanical load and temperature with known magnitude of carrier intensity gradient at the top surface.

Initial conditions

\(\theta (x, y, z, t)=\frac{\partial {\theta (x, y, z, t)}}{\partial t}=0,\)\(N(x, y, z, t)=\frac{\partial {\theta (x, y, z, t)}}{\partial t}=0,\)\((u, v, w)(x, y, z, t)=\frac{\partial {(u, v, w)(x, y, z, t)}}{\partial t},\)\(\sigma _{ij}(x, y, z, t)=\frac{\partial {\sigma _{ij}(x, y, z, t)}}{\partial t}=0\) at \(t=0.0.\)

Boundary conditions

Case-I

The top and bottom surfaces of the plate are subjected to the mechanical load as:

At x=0 (bottom surface)

\(\sigma _{xx}=0,~ \sigma _{xy}=0,~ \sigma _{xz}=0,~ \theta =0, ~ D_E \frac{dN}{dx}=\zeta _1 N.\)

At \(x=h\) (Top surface)

\(\sigma _{xx}=p,~ \sigma _{xy}=0,~ \sigma _{xz}=0,~ \theta =0,~ D_E \frac{dN}{dx}=\zeta _1 N.\)

where p and \(\zeta _1\) are constant.

The normal stress component \(\sigma _{xx}\) is considered as zero at the bottom surface of the plate, while the top surface is subjected to a uniform normal mechanical load of magnitude p. The shear stress components \(\sigma _{xy}\) and \(\sigma _{xz}\) are assumed to vanish on both the bottom and top surfaces. The thermal condition \(\theta =0\) specifies that these surfaces are maintained at a constant reference temperature, thereby simulating an environment without additional thermal excitation. The carrier condition \(D_E \tfrac{dN}{dx}=\zeta _1 N\) corresponds to the surface recombination of charge carriers at the bottom and top surfaces.

Case-II

At x=0 (bottom surface)

\(\sigma _{xx}=0,~ \sigma _{xy}=0,~ \sigma _{xz}=0,~ \theta =0,~ D_E \frac{dN}{dx}=\zeta _1 N.\)

At \(x=h\) (top surface)

\(\sigma _{xx}=P_1~exp(st+i(ay+bz)),~ \sigma _{xy}=0,~ \sigma _{xz}=0,~ \theta =\theta _{0}~exp(st+i(ay+bz)),~ D_E \frac{dN}{dx}=\zeta _1 N.\)

where \(P_1\) is constant. Bottom surface of the plate is subjected to traction-free, while the top surface is subjected to a uniform normal mechanical and thermal load which varies exponentially. The shear stress components \(\sigma _{xy}\) and \(\sigma _{xz}\) are assumed to vanish at the top surfaces. The carrier condition \(D_E \tfrac{dN}{dx}=\zeta _1 N\) corresponds to the surface recombination of charge carriers at the bottom and top surfaces.

The arbitrary constants \(A_j\) (j=1(1)10) have been calculated by using the matrix inversion method from the two types of boundary conditions mentioned above. The closed form of the analytical solution of the problem is completely obtained according to the unique solution of these arbitrary constants, which are used for numerical results and discussions.

Numerical results and discussions

We consider the thermoelastic problem of the three-dimensional rectangular plate with the presence of an external heat source and an electromagnetic field under the three theories of NLCDC, NLLS, and NLDPL. An efficient computer programming language (MATLAB R2021a) is used to study the numerical analysis and the corresponding graphical representations. As discussed by Islam et al.19 and Alshehri et al.29, the material constants of silicon (Si), germanium (Ge) and gallium arsenide (GaAs) are used for the numerical computations. The values of the material constants are provided in Table 1.

The corresponding numerical values of the associated constants are given by:

\(\epsilon _0=\frac{10^{-9}}{36\pi }\), \(\mu _0=4\pi \times 10^{-7}\), \(H_0= \frac{10^7}{4\pi }\), \(p=1.0, P_1=0.01\), \(\zeta _1=1.0, a=1.2, b=1.3, z=0.5,\) angular frequency(s)=2.5 and time(t)=0.2.

Significant impact of the three theories

Figures 2, 3, 4 and 5 depict the variation of the normal stress(\(\sigma _{xx}\)), shearing stress(\(\sigma _{xy}\)), and the temperature distribution (\(\theta\)) versus space variable(x) in silicon material. The effect of the non-local classical dynamical coupled (NLCDC) theory (\(\tau _\theta =0.0, \tau _q=0.0, \lambda _{q_1}=0.012, \lambda _{q_2}=0.015, \lambda _{q_3}=0.017\)), non-local Lord and Shulman(NLLS) theory (\(\tau _\theta =0.0, \tau _q=0.4, \lambda _{q_1}=0.012, \lambda _{q_2}=0.015, \lambda _{q_3}=0.017\)), and non-local dual phase lag (NLDPL) theory (\(\tau _\theta =0.2, \tau _q=0.4, \lambda _{q_1}=0.012, \lambda _{q_2}=0.015, \lambda _{q_3}=0.017\)) are discussed for the thick rectangular plate of the semiconductor medium.

Figure 2 illustrates that the variation of the normal stress(\(\sigma _{xx}\)) versus the space variable \(x\) according to three different theories: NLCDC, NLLS, and NLDPL. For the NLCDC theory, the variations of the stress distributions are all smooth in nature. The wave of the three theories converges at the peak on the top surface of the plate. The variation of the stress component (\(\sigma _{xx}\)) could be due to different factors such as applied loads, material behaviour, or geometric constraints.

Figure 3 illustrates the variations of the shearing stress component (\(\sigma _{xy}\)) with the space variable (\(x\)) under three theories: NLCDC, NLLS, and NLDPL. The characteristics of the shearing stress (\(\sigma _{xy}\)) in NLLS theory differ from those in the NLCDC and NLDPL theories. The structural size effect due to the non-local theory causes a significant change in the shearing stress. These types of characteristics appear to predict delayed effects in stress response, which could be due to phase-lagging and coupled behaviour in the shearing stress.

In Fig. 4, the temperature distribution (\(\theta\)) as a function of the space variable (x) is presented for three theories: NLCDC, NLLS, and NLDPL. The behaviour of \(\theta\) is more pronounced in the nonlocal generalized thermoelastic theory compared to the other two theories. The temperature distribution is at a minimum on both surfaces (bottom and top), confirming the prescribed boundary conditions. The middle portion of the plate experiences the highest temperature. The resulting curves are smooth and symmetrical, indicating a well-behaved thermal distribution.

Figure 5 beautifully illustrates the normal stress component (\(\sigma _{xx}\)) as it relates to the space variable (x) across three different theories: NLCDC, NLLS, and NLDPL. It’s particularly noteworthy that this stress component reaches its minimum value at \(x = 0.7\). The NLCDC and NLDPL models exhibit almost identical physical behaviour concerning normal stress (\(\sigma _{xx}\)). Overall, the generalised theory for fixed values of the physical parameters presents even more significant results. Importantly, the physical disturbance occurs in the middle section of the plate, which confirms the boundary conditions at \(x=0\) and \(x=1\). The concave downward shape of all the curves suggests that both compression and tension behaviour are most pronounced in the middle portion.

Figures 2, 3, 4 and 5 illustrate the significant effects of the relaxation time parameters and the phase-lagging parameter in the two theories, NLLS and NLDPL, respectively, compared to the classical theory. Stress components and temperature distributions are characterized by a wave-type formulation in photo-thermoelasticity. Carrier concentration and free carrier movement in silicon (Si) are analyzed through these figures.

Significant impact of the external heat source (Q)

Figures 6, 7, 8 and 9 represent the variations of the normal stress component (\(\sigma _{xx}\)), shearing stress components (\(\sigma _{xy}, \sigma _{xz}\)), and temperature distribution (\(\theta\)) with the space variable (x) for three distinct values of an external heat source (Q) of the semiconductor material silicon(Si). We now consider the three fixed values of the nonlocal parameters(\(\lambda _{q_{1}}=0.012, \lambda _{q_{2}}=0.015,\) and \(\lambda _{q_{3}}=0.017\)), the temperature gradient (\(\tau _\theta =0.2\)) and the heat flux(\(\tau _q=0.4\)).

Figure 6 illustrates the variations of the normal stress component (\(\sigma _{xx}\)) with the space variable (x) for three distinct values of the heat source \((Q=0.0, 5.0, 10.0)\). The characteristics of \(\sigma _{xx}\) for \(Q=0.0\) gradually increase with an increase of x. The graphs of \(\sigma _{xx}\) for the heat sources (\(Q=5.0, 10.0\)) show a very significant characteristic compared to the graph without an external heat source. As Q increases, the stress \(\sigma _{xx}\) develops a more significant concave behaviour, showing increased tensile and compressive effects within the domain. It is illustrated that the internal resistance decreases with increasing heat source. The magnitude of Q increase stress gradients, making the system more susceptible to higher tensile or compressive stresses in the middle portion of the plate.

In Fig. 7, the variation of the shearing stress (\(\sigma _{xy}\)) with the space variable (x) for three distinct values of the heat source \((Q=0.0, 5.0, 10.0)\). The characteristics of the shearing stress do not significantly impact on the plate at \(Q=0.0\). The shearing stress \((\sigma _{xy})\) varies with the increase of the external heat source (Q). The thermal effect influences the stress field. This effect also leads to more pronounced mechanical and electronic effects in semiconductor materials. The shearing stress \((\sigma _{xy})\) is crucial in Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems(MEMS) devices, where mechanical deformation affects the electronic deformation(ED). The increasing Q could represent thermal expansion, piezoelectric effects, or external mechanical forces acting on the semiconductor.

Figure 8 represents the variation of the normal stress component (\(\sigma _{yy}\)) with the space variable (x). It includes multiple curves corresponding to different values of the heat source \(Q =0.0, 5.0,\) and 10.0. Therefore, the mechanical load may also be present without thermal influences. The properties of the normal stress (\(\sigma _{yy}\)) for \(Q=10.0\) are significantly effective in this plate. The characteristics of this normal stress \((\sigma _{yy})\) are more crucial for strain engineering, piezoelectric effects, and thermal stress analysis in semiconductor devices. The minimum magnitude becomes more negative as Q increases, showing increased compressive stress in the central region.

Figure 9 describes the variation of the normal stress component(\(\sigma _{xx}\)) with the space variable (x) for three different values of the heat source (\(Q=0.0, 5.0\), and 10.0). The behaviour of \(\sigma _{xx}\) is significantly affected in the middle portion of this plate. The applied heat source(Q) enhances compressive stress in the thick plate of the semiconductor. All the curves exhibit a parabolic shape in nature. This stress component vanishes at both the surfaces(top and bottom) and attains the minimum at the middle of the plate.

The temperature can modify the energy range between the conduction and valence bands of the semiconductor crystal. That may cause a continuous decrease of surface resistivity along with more modifications of the energy level for the respective energy of the indirect band gap. Carrier mobility can be estimated by increasing the effect of temperature. So, the corresponding values of the external heat source (Q) play a significant role in transforming a semiconductor or an intrinsic semiconductor to a conductor.

Significant impact of the applied magnetic field \((H_0)\)

Figures 10, 11, 12 and 13 describe the normal stress component (\(\sigma _{xx}\)), shearing stress components (\(\sigma _{xy}, \sigma _{xz}\)), and temperature distribution (\(\theta\)) with the space variable(x) under three various values of the magnetic field (\(H_0\)) for semiconductor material silicon(Si). Here, we consider the fixed values of the nonlocal parameters(\(\lambda _{q_{1}}=0.012, \lambda _{q_{2}}=0.015,\) and \(\lambda _{q_{3}}=0.017\)), the temperature gradient (\(\tau _\theta =0.2\)), the heat flux(\(\tau _q=0.4\)), and the heat source(\(Q=5.0\)).

Figure 10 illustrates the normal stress component \((\sigma _{xx})\) as a function of the space variable (x) under three different values of the magnetic field: \(H_0 = \frac{10^7}{4\pi }\), \(\frac{10^{11}}{4\pi }\) and \(\frac{10^{14}}{4\pi }\). The behaviour of \(\sigma _{xx}\) for \(H_0 = \frac{10^7}{4\pi }\) is notably distinct compared to the other two graphs. Higher values of magnetic fields result in greater stress variations, likely as a result of the enhanced Lorentz forces acting on the material. The increasing effect of the magnetic field suggests that magneto-mechanical coupling plays a crucial role in stress distribution.

Figure 11 illustrates the shearing stress component (\(\sigma _{xz}\)) as a function of the space variable (\(x\)) for three different values of the magnetic field: \(H_0 = \frac{10^7}{4\pi }\), \(\frac{10^{11}}{4\pi }\) and \(\frac{10^{16}}{4\pi }\). The behavior of \(\sigma _{xz}\) for \(H_0 = \frac{10^7}{4\pi }\) shows a significant impact compared to the other two variations. The characteristics of \(\sigma _{xz}\) are most pronounced for the values of \(H_0 = \frac{10^{11}}{4\pi }\) and \(\frac{10^{16}}{4\pi }\) in the middle portion of the plate. The observed reduction in \(\sigma _{xz}\) as \(H_0\) increases indicates that the applied magnetic field has a stabilizing effect on the shearing stress. This figure demonstrates that the applied magnetic field has a significant influence on the shearing stress \(\sigma _{xz}\).

Figure 12 depict the shearing stress component(\(\sigma _{xy}\)) with the space variable (x) for three different values of the magnetic field (\(H_0= \frac{10^7}{4\pi }, \frac{10^{11}}{4\pi }\), and \(\frac{10^{14}}{4\pi }\)). The graphs of \(\sigma _{xy}\) are a smooth parabola for the values of the magnetic field \(H_0 = \frac{10^{11}}{4\pi }\) and \(\frac{10^{14}}{4\pi }\), where shearing stress reaches the maximum at the center and decreases toward the edges. The characteristic of \(\sigma _{xy}\) for \(H_0 = \frac{10^{7}}{4\pi }\) is relatively negligible compared to the others. The increase in shearing stress with \(H_0\) indicates that the material may exhibit magnetorheological properties, where the applied magnetic fields enhance its shear resistance. The shearing stress \(\sigma _{xy}\) indicate that magneto-mechanical interactions play a significant role in this system.

Figure 13 illustrates the normal stress component(\(\sigma _{zz}\)) with space variable (\(x\)) for three different values of the magnetic field: \(H_0 = \frac{10^7}{4\pi }\), \(\frac{10^{11}}{4\pi }\) and \(\frac{10^{14}}{4\pi }\). The behaviors of \(\sigma _{zz}\) show a greater variation with more pronounced values of positive and negative stress. This behaviour is important for applications involving magneto-thermoelastic materials, stress-controlled actuators, and structural components that are subjected to magnetic forces. The electro-magnetic field induces additional Lorentz forces that enhance the normal stress component which also leads to greater compressive and tensile effects within the material.

The free carrier concentration in a semiconductor acquires higher energy from the applied electric field, which also produces a magnetic field. This energetic carrier can be promoted to a higher energy level such as the conduction band. This may happen because of the impact of ionisation on a semiconductor in the presence of high electric and magnetic fields.

Comparison of the significant impact for three semiconductors

Figures 14, 15 and 16 present a comparison of the significant behavior of three materials silicon (Si), germanium (Ge), and gallium arsenide (GaAs) focusing on the shearing and normal stress components \((\sigma _{xy}, \sigma _{yy}, \sigma _{xz}, \sigma _{zz})\). Based on the fixed values for the temperature gradient (\(\tau _\theta = 0.2\)), the heat flux (\(\tau _q = 0.4\)), the non-local parameters (\(\lambda _{q_1} = 0.012\), \(\lambda _{q_2} = 0.015\), \(\lambda _{q_3} = 0.017\)), and the external heat source (\(Q = 5.0\)), the corresponding discussions are depicted.

Figure 14 illustrates that the shearing stress (\(\sigma _{xy}\)) with the space variable (\(x\)) for three different semiconductor materials: silicon (Si), germanium (Ge) and gallium arsenide (GaAs). The shearing stress (\(\sigma _{xy}\)) exhibits a smooth oscillatory pattern and reaches the maximum value at the bottom surface of the semiconductor. Germanium displays the highest magnitude of shearing stress, while gallium arsenide shows the lowest. Shearing stress can induce strain effects that influence the electronic band structure, subsequently affecting carrier mobility in semiconductor devices.

Figure 15 illustrates the representation of the shearing stress(\(\sigma _{xz}\)) with the space variable (\(x\)) for three different semiconductor materials. The magnitude of the shearing stress \(\sigma _{xz}\) is higher for silicon as compared than for the other two materials. In contrast, gallium arsenide shows a lower absolute value of \(\sigma _{xz}\) than both silicon and germanium. Germanium demonstrates intermediate shearing stress characteristics, lower than silicon but higher than gallium arsenide. All curves are smooth, symmetric and parabolic in shape, which is more indicative of the shearing stress distributions under uniform loading conditions. Silicon’s superior shear stress resistance makes it particularly suitable for applications where mechanical stability is essential, such as in microelectromechanical systems (MEMS).

Figure 16 illustrates the variation of the normal stress component (\(\sigma _{zz}\)) as a function of the space variable (\(x\)) for three different semiconductor materials. The basic characteristics of the graphs for \(\sigma _{zz}\) indicate the compressive nature. The magnitude of \(\sigma _{zz}\) for germanium exhibits an intermediate compressive stress which is lower than that of silicon but higher than that of gallium arsenide. The significant properties in the stress variation offer valuable insights for engineers, enabling them to evaluate the mechanical reliability of these semiconductor materials under operational loads.

The characteristics of the carrier intensity (N) significantly depend on the density of the changed carrier, which is extremely influenced by the temperature gradient, fluctuations in temperature, and the diffusion of carriers in semiconductors. In addition to these factors, internal stresses and corresponding surface resistivity are more important for different semiconductors. Lower values of stress and corresponding resistivity yield an increase in diffused carrier concentration, which is also characterized by the behavior of conduction in semiconductors.

Significant impact of the thermoelastic coupling parameter \((\epsilon _{1})\)

Figures 17, 18 and 19 illustrate the variation of the normal stress component (\(\sigma _{xx}\)) and the shear stress components (\(\sigma _{xz}, \sigma _{yz}, \sigma _{xy}\)) with the space variable (\(x\)). This analysis is performed for three fixed values of the thermoelastic coupling parameter (\(\epsilon _1 = 0.001, 0.005,\) and \(0.009\)) in silicon(Si) semiconductor material. Additionally, we have maintained fixed values for the temperature gradient (\(\tau _\theta = 0.2\)), the heat flux (\(\tau _q = 0.6\)), the non-local parameters (\(\lambda _{q_1} = 0.12, \lambda _{q_2}=0.15, \lambda _{q_3}=0.17\)), and the heat source (\(Q = 5.0\)).

Figure 17 describes the normal stress component (\(\sigma _{xx}\)) with the space variable (\(x\)) for three distinct values of thermoelastic coupling parameter (\(\epsilon _1 = 0.001, 0.005,\) and \(0.009\)). For the highest value of \(\epsilon _1 = 0.009\), the \(\sigma _{xx}\) becomes slightly negative for a small region of the semiconductor, which may indicate stress reversal due to significant thermoelastic interactions. The value of \(\sigma _{xx}\) decreases as \(\epsilon _1\) increases, which indicates that the stronger thermoelastic effects tend to reduce the stress levels. The reduction in stress magnitude with increasing \(\epsilon _1\) suggests that materials with strong thermoelastic coupling may be more resistant to thermal stress-induced failure.

Figure 18 illustrates the shearing stress component(\(\sigma _{xz}\)) with the space variable \(x\) for different values of the thermoelastic coupling parameter (\(\epsilon _1 = 0.001, 0.005,\) and \(0.009\)). The increasing behaviour of \(\sigma _{xz}\) for \(\epsilon _1 = 0.005\) and \(\epsilon _1 = 0.009\) indicates that a stronger thermoelastic coupling enhances the shearing stress in the material. The shearing stresses can be significant in materials subjected to combined thermal and mechanical loading for higher thermoelastic coupling \(\epsilon _1\).

Figure 19 illustrates the shearing stress component(\(\sigma _{xy}\)) along the space variable (\(x\)) for distinct values of the thermoelastic coupling parameter \(\epsilon _1 = 0.001\), \(0.005\), and \(0.009\). As the value of \(\epsilon _1\) increases, the graphs of \(\sigma _{xy}\) shift upward, indicating greater shear stress effects due to the enhanced thermal coupling. Absolute surface resistivity vanishes at the two surfaces of the thick plate.

The coupling of plasma and the non-local thermoelastic plane waves is studied simultaneously, which also provides the finite speed of wave propagation and satisfies the basic criterion of the generalised theory of thermoelasticity. This comparison, along with the graphical representation, holds great importance in photothermoelasticity.

Significant impacts of three-dimensional distributions for stresses and temperature

Figures 20, 21, 22 and 23 illustrate the variation of normal stress\((\sigma _{yy})\), the shear stress components \((\sigma _{xy}, \sigma _{xz})\), and temperature\((\theta )\) with the space variables \(x\) and \(y\). This analysis takes into account the influence of the electromagnetic field and the external heat source \((Q)\). The behavior of the stress components and the temperature distribution is examined for fixed values of the temperature gradient \((\tau _\theta = 0.2)\), the heat flux \((\tau _q = 0.4)\), the non-local parameters \((\lambda _{q_1} = 0.012, \lambda _{q_2} = 0.015, \lambda _{q_3} = 0.017)\), and the external heat source \((Q = 5.0)\) in the silicon(Si) semiconductor material.

Figure 20 describes the variation of the normal stress component \((\sigma _{yy})\) versus the space variables x and y. The absolute value of \(\sigma _{yy}\) increases with the space variables x and y increasing simultaneously, and it reaches maximum values at \(x=0.99\) and \(y=0.6\). The normal stress component (\(\sigma _{yy}\)) exhibits a smooth variation in the domain, with regions with positive and negative stress values. The stress component \((\sigma _{yy})\) has a more significant effect in some regions. The graph illustrates a peak (yellow region) indicating the maximum stress value and a trough (blue region) representing the minimum stress value.

Figure 21 illustrates the variation of the shearing stress component(\(\sigma _{xy}\)) with the space variables x and y. The characteristics of the shearing stress component (\(\sigma _{xy}\)) attain maximum and minimum values due to the applied mechanical load. The central transition region shows where the stress changes from positive to negative values, likely due to the symmetry of the applied forces. The distribution of the shearing stress component (\(\sigma _{xy}\)) is responsible for structural analysis which is essential for machine design.

Figure 22 illustrates the temperature distribution (\(\theta\)) with the space variables x and y. This three-dimensional plot effectively depicts the temperature field within a thermoelastic system. The temperature distribution indicates non-uniform heat propagation, with significant temperature variations in the central region and near-zero values at the boundaries. The temperature appears to be zero at the edges, suggesting the presence of fixed boundary conditions or thermal equilibrium at those points. This graph indicates that heat conduction is not uniform, being influenced by differences in boundary conditions, material properties, or external sources.

Figure 23 illustrates how the shearing stress component (\(\sigma _{xz}\)) varies with the space variables x and y. The shearing stress component \(\sigma _{xz}\) experiences a gradual increase and decrease in the domain, influenced by the applied loads and the properties of the material. The maximum values are concentrated in the central regions, indicating a localised stress concentration resulting from external forces or internal material deformation. The smooth curvature of the surface suggests a continuous variation of shearing stress throughout the domain. Understanding the shearing stress distribution helps in analysing elasticity, plasticity, and fracture mechanics, which is essential for designing strong and durable structures.

Figures 20, 21, 22 and 23 illustrate that the significant impact of stress and temperature with the space variables x and y is studied for the fixed values of the physical field variables. These graphical representations could be focused on research depending upon the experimental measurement and validate the non-local theory in the design of semiconductor devices.

Conclusion

This study presents a nonlocal magneto-thermoelastic model based on an isotropic and homogeneous three-dimensional rectangular semiconductor medium, ensuring that both thermal and mechanical boundary conditions are satisfied. The problem is investigated within the framework of nonlocal thermoelasticity theory under three models (NLCDC, NLLS, and NLDPL) in the presence of an external heat source and magnetic field. Solutions are derived through normal mode analysis and the eigenvalue approach to examine the variations of the physical field variables. The analytical results are presented graphically using the material constants of three different semiconductors( Si, Ge, and GaAs), and a comparison of the material properties is illustrated. Based on our analysis and the corresponding numerical results, we can draw several conclusions:

-

(1)

The variations of the stress components and temperature distribution for the NLCDC, NLLS, and NLDPL theories significantly affect the resistivity of the semiconductors.

-

(2)

The distributions of the normal and shearing stress components with the different values of an external heat source help to process semiconductor chips that involve heat treatment.

-

(3)

The magnetic fields play an essential role in influencing the stress distributions of electromechanical systems for semiconducting materials. This analysis and results are particularly valuable for the design of magnetically controlled actuators, structural components, and smart materials that require precise stress management capabilities.

-

(4)

The comparative study of the properties of three important semiconductor materials: silicon (Si), germanium (Ge), and gallium arsenide (GaAs) plays a significant role in the semiconductor industry, and silicon is particularly crucial due to its unique properties and widespread uses.

-

(5)

The significant influence of the thermoelastic coupling parameter (\(\epsilon _1\)) on the upper portion of the rectangular semiconductor plate helps us to study the behavior of the ionized impurity or the mobility of doping scattering.

-

(6)

The present three-dimensional models are essential for effective thermal management and structural design, ensuring material stability and preventing failures in engineering applications.

-

(7)

As discussed in Mostefai14, the energy band gap \((E_g)\) is a function of temperature, rather than being considered constant. Therefore, these semiconductors are characterised by controlling the temperature as per Eq. (27) and the corresponding figures.

-

(8)

As it is prescribed in Table 1 that the energy band gaps of silicon(Si), germanium (Ge), and gallium arsenide (GaAs) are 1.11 eV, 0.72 eV, and 1.42 eV, respectively, at 300k. It is shown that the energy band gap and the corresponding doping concentration are also temperature dependent. This article presents the dependence of internal surface resistivity for different semiconductors. This is another fundamental property for the semiconductors which is considered as the geometrical dimensions along with the interatomic spaces that affect the vibrations of the free atoms. This property also helps the free electrons along with the doping atoms bound to overlap the respective energy band. It has great importance for many modern electronic devices.

-

(9)

This study also predicts the comparative characteristics of three semiconductors Si, Ge, and GaAs. On the basis of this analysis, the type of semiconductor can be chosen as the principal advantage of electronic devices.

-

(10)

The analytical closed-form solutions and the corresponding numerical results with discussions have been presented for this model. The electromagnetic field components and an external heat source significantly influence the thermoelastic behaviour and wave propagation in semiconductors. In addition to all the results and discussions drawn in this article, it is more important to implement practical experiments to verify these types of behaviour and properties in the operational form of the different types of modern electronic devices.

The numerical simulations are presented in three-dimensional geometries; therefore, the semiconductor is considered very thin compared to other dimensions, the model can be restricted to a two-dimensional analysis and validating it experimentally further its applicability and accuracy accordingly in realistic engineering contexts. The results obtained both numerically and graphically demonstrate that photothermal effects significantly impact various phenomena with numerous applications in the engineering field. This includes areas such as semiconductors, chemical reactions during photothermal processes, modern aeronautics, astronautics, advanced chemical engineering (such as chemical and mechanical planarization), and nuclear reactors. Overall, this work contributes a unified theoretical formulation of photo-thermoelasticity for a more advanced framework to design in renewable energy applications.

Data availability

All data generated or discussed in this article are included in this study. The software used in this article is MATLAB(R2021a).

References

Mostefai, A. Comparison between silicon (Si) and gallium arsenide (GaAs) using MATLAB. J. Nano- Electron. Phys. 14(4), 04028 (2022).

Kumar, R., Tiwari, R. & Singhal, A. Analysis of the photo-thermal excitation in a semiconducting medium under the purview of DPL theory involving non-local effect. Meccanica 57(8), 2027–2041 (2022).

Ahmed, I. E., Abouelregal, A. E. & Aldandani, M. Study of the behavior of photothermal and mechanical stresses in semiconductor nanostructures using a photoelastic heat transfer model that incorporates non-singular fractional derivative operators. Acta Mechanica 236(2), 1339–1358 (2025).

Zenkour, A. M. Refined multi-phase-lags theory for photothermal waves of a gravitated semiconducting half-space. Compos. Struct. 212, 346–364 (2019).

Othman, M. & Lotfy, K. Transient disturbance in a half-space under generalized magneto-thermoelasticity with internal heat source. Acta Phys. Pol., A 116(2), 185–192 (2009).

Mahdy, A. M. S., Lotfy, K., Ahmed, M. H., El-Bary, A. & Ismail, E. A. Electromagnetic Hall current effect and fractional heat order for microtemperature photo-excited semiconductor medium with laser pulses. Results Phys. 17, 103161 (2020).

Alqahtani, Z., Abbas, I., El-Bary, A. A. & Almuneef, A. Analytical solutions of photothermal wave in semiconductor materials. Silicon 16(13), 5355–5365 (2024).

Salah, D. M., Abd-Alla, A. M., Abo-Dahab, S. M., Alharbi, F. M. & Abdelhafez, M. A. Magnetic field and initial stress on a rotating photothermal semiconductor medium with ramp type heating and internal heat source. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 16456 (2024).

Biot, M. A. Thermoelasticity and irreversible thermodynamics. J. Appl. Phys. 27(3), 240–253 (1956).

Lord, H. W. & Shulman, Y. A generalized dynamical theory of thermoelasticity. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 15(5), 299–309 (1967).

Green, A. E. & Lindsay, K. Thermoelasticity. J. Elast. 2(1), 1–7 (1972).

Green, A. E. & Naghdi, P. A re-examination of the basic postulates of thermomechanics. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Series A: Math. Phys. Sci. 432(1885), 171–194 (1991).

Green, A. E. & Naghdi, P. On undamped heat waves in an elastic solid. J. Therm. Stresses 15(2), 253–264 (1992).

Green, A. E. & Naghdi, P. Thermoelasticity without energy dissipation. J. Elast. 31(3), 189–208 (1993).

Othman, M. I., Tantawi, R. S. & Eraki, E. E. Propagation of the photothermal waves in a semiconducting medium under LS theory. J. Therm. Stresses 39(11), 1419–1427 (2016).

Lotfy, K., Hassan, W. & Gabr, M. E. Thermomagnetic effect with two temperature theory for photothermal process under hydrostatic initial stress. Results Phys. 7, 3918–3927 (2017).

Othman, M. I., Tantawi, R. S. & Eraki, E. E. Effect of the gravity on the photothermal waves in a semiconducting medium with an internal heat source and one relaxation time. Waves Random Complex Media 27(4), 711–731 (2017).

Eringen, A. C. Theory of nonlocal thermoelasticity. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 12(12), 1063–1077 (1974).

Islam, N., Das, B., Shit, G. C. & Lahiri, A. Thermoelastic and electromagnetic effects in a semiconducting medium. Acta Mechanica 236, 217 (2025).

Abd-Elaziz, E. M., Jahangir, A. & Othman, M. I. Propagation of plane waves in nonlocal semiconductor nanostructure thermoelastic solid with fractional derivative due to ramp-type heat source. Int. J. Comput. Mater. Sci. Eng. 13(04), 2350032 (2024).

Othman, M. I., Tantawi, R. S. & Eraki, E. E. Effect of initial stress on a semiconductor material with temperature-dependent properties under DPL model. Microsyst. Technol. 23(12), 5587–5598 (2017).

Tzou, D. Y. A unified field approach for heat conduction from macro-to micro-scales. J. Heat Transfer 117(1), 8–16 (1995).

El-Dali, A., Othman, M. I., Alaofi, Z. M., Elsakout, D. M. Novel two-dimensional uncertainty envelop estimation using stochastic analysis for the semiconductor materials during opto-electronic deformation. Results Eng. 106537 (2025).

Todorović, D. M. Plasma, thermal, and elastic waves in semiconductors. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74(1), 582–585 (2003).

Das, B., Islam, N. & Lahiri, A. Study of non-local thermoelasticity of a rectangular plate. J. Therm. Stress. 48(2), 186–208 (2025).

Baltz, R. Dielectric description of semiconductors: From Maxwell to semiconductor Bloch equations. In Ultrafast Dynamics of Quantum Systems: Physical Processes and Spectroscopic Techniques 323–356 (Springer, US, Boston, MA, 2002).

Sardar, S. S., Das, B., Ghosh, D., Lahiri, A. Photothermal effects of semiconducting medium with non-local theory. Waves in Random and Complex Media 1-22 (2023).

Das, B., Sardar, S. S., Ghosh, D. & Lahiri, A. Wave propagation in a non-local magneto-thermoelastic medium permeated by heat source. Int. J. Comput. Methods Eng. Sci. Mech. 24(5), 314–327 (2023).

Alshehri, H. M., Lotfy, K., Raddadi, M. H. & El-Bary, A. A. A nonlocal photoacoustic effect with variable thermal conductivity of semiconductor material subjected to laser heat source. Results Phys. 61, 107715 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the esteemed reviewers for their suggestions, based on which the present work has been improved. The authors are also thankful to the DST-FIST Purse Programme (Programme no. SR/FST/MS-II/2021/101(C)) of the Department of Mathematics, Jadavpur University, Kolkata, India.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Das, B., Islam, N. & Lahiri, A. Comparative thermoelastic analysis of semiconductors with an external heat source under three theories. Sci Rep 15, 40120 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23984-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23984-y