Abstract

To address low control accuracy and frequent controller updates in gas blending, a fuzzy neural network PID control method based on an event-triggered mechanism (ET-FNN-PID) is proposed. Key operational variables correlated with gas concentration are selected as model inputs based on real conditions and expert knowledge. A data-driven model is then constructed using a Takagi–Sugeno (TS) fuzzy neural network. The FNN-PID controller dynamically adjusts PID parameters through the fuzzy neural network, with online parameter updates via gradient descent. An event-triggered condition using a fixed threshold is introduced to reduce unnecessary controller updates and mechanical wear. Simulation results using real gas data show that the ET-FNN-PID controller effectively captures nonlinear system behavior and achieves precise gas concentration control while significantly reducing update frequency compared to traditional time-triggered and standard FNN-PID controllers. This approach enhances control performance and contributes to energy efficiency and emission reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low-concentration methane, the primary component of mine gas and the second largest contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions, has a warming potential approximately 21 times that of carbon dioxide1. In China, this underutilized resource is often sold, resulting in wasted energy and environmental damage. Under the dual-carbon “30·60” targets, coal-mine gas management now emphasizes methane-emission reduction and zero-discharge protocols2. However, the utilization rate of low-concentration mine gas remains low, making the development of efficient methods for its valorization a pressing challenge3.

Gas power generation technology is a promising new energy technology that converts unused gas from coal mines into electrical energy and is widely used around the world3. It helps reduce air pollution from gas emissions, improves overall resource utilization in coal mining, and generates economic benefits. However, the low-concentration gas extracted from the coal seams cannot be used directly in gas generator sets. To address this, an effective approach is to premix high-concentration gas with low-concentration gas to meet the combustion requirements for power generation4. In this process, low-concentration gas—typically below the lower explosive limit—is introduced into a combustion-supporting environment through precise mixing, allowing it to burn stably in gas engines. The key is to maintain a range of combustible concentrations and ensure safety and combustion efficiency through optimized gas blending and control.

The gas concentration extracted from different collection areas is affected by multiple factors, exhibiting significant temporal variability and non-linearity5. To ensure stable operation of gas generator sets, it is essential to rapidly and accurately regulate the concentration of mixed gases to meet operational requirements . However, establishing an accurate model of gas mixing concentration remains a fundamental challenge for effective concentration control—and such challenges are equally prevalent in broader industrial fields, including chemical processes, energy management, and intelligent mechatronic systems. These processes are generally constrained by nonlinearity, time-varying characteristics, and model uncertainty. Fuzzy logic control, which effectively addresses the aforementioned issues using linguistic information, has become one of the efficient tools for solving such complex engineering problems. A review on fuzzy control systems6, while sorting out three main directions (i.e., T-S fuzzy control, data-driven fuzzy control, and evolving fuzzy control), further points out that the in-depth integration of fuzzy systems with other intelligent technologies such as neural networks is a core approach to improve controller performance and expand applications.

In recent years, the successful implementation of data-driven modeling methodologies, including least squares, neural networks7, and support vector machines, has provided valuable references for modeling time series data8. Although TLESN introduces a transfer learning-based compensation layer to address autocorrelated errors in nonlinear system modeling and improve prediction accuracy9, ETL-ESN further expands this idea by leveraging a neural network-based error compensation mechanism with transfer learning, specifically improving forecast performance in wind power applications10. Wu et al. developed a data-driven model to predict the remaining useful life using multiple sensor signals integrated with a deep long-short-term memory neural network11. Carron et al. proposed a data-driven model control strategy12, which uses data collected during operation to enhance the robotic arm model, thus improving the tracking performance, and utilized the model for subsequent predictive control. Furthermore, data-driven control demonstrates great potential in enhancing the disturbance rejection capability of systems. By integrating system operational data with advanced control laws, this field effectively improves the robustness of systems under uncertainties and external disturbances. For instance, Roman et al. proposed a hybrid strategy combining active disturbance rejection control (ADRC) and sliding mode control13, while Yue et al. developed a model-free approach based on a data-driven observer14 Both methods have verified their effectiveness in suppressing complex disturbances through experiments, providing new insights for industrial process control.

In addition to the aforementioned data-driven methods, reinforcement learning (RL), another key branch of intelligent control, has shown great potential in control systems in recent years. Luy et al. proposed an RL-based integrated kinematic-dynamic tracking control algorithm15 for nonholonomic wheeled mobile robots, using a single neural network for an actor-critic structure to cut costs, and ensuring stability via HJI equation learning and Lyapunov techniques to resist disturbances; Zamfirache et al. developed an adaptive control method combining Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO)and slime mold algorithm16 for tower crane reference tracking, where the slime mold algorithm dynamically optimizes PPO’s learning rate to fix the adaptability defect of fixed rates and boost response performance; Hentout et al. designed a hierarchical system for mobile robot dynamic navigation17,using Deterministic Construction Algorithm(DCA)for global obstacle-avoidance paths and Efficient Fuzzy Logic Controller(EFLC) for dynamic obstacle avoidance to ensure navigation safety. These studies show that controllers with learning mechanisms better adapt to the time-varying and nonlinear characteristics of complex environments, offering a new direction to address the poor adaptability of traditional control.

Currently, the PID controller is widely used in industrial production due to its simple algorithm and easy implementation, and its proportion of applications has exceeded 90 %18. However, in the gas mixing concentration control system, due to lag in sensor acquisition and transmission, the change in internal and external environment in the mining area, and the interference of uncertain factors in the controlled object, the control system presents non-linear and time-varying characteristics19. This leads to a large error in traditional PID control, which cannot achieve the ideal control effect20,21 .To overcome the shortcomings of classical PID control, the classical PID control method of neural network optimization has become a research hotspot22. Li proposed a PID controller for the BP neural network to study the gas concentration control problem23. Shi proposed an adaptive neuro-fuzzy PID controller for nonlinear systems based on the Twin Delayed Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (TD3) algorithm24. Wang proposed a PID controller based on an echo state network25. All of these methods are based on time-triggered control mechanisms.

During the past few decades, the event-triggered control mechanism has garnered significant scholarly attention due to its superior resource allocation capabilities compared to time-triggered control26,27. Reference28 examines the event-based predictive control issue in the context of the WWTP model. Du explored the consensus problem in multi-agent systems with general dynamics, establishing both centralized and distributed dynamic event-triggered mechanisms29. Reference30 introduced the event-triggered mechanism within the PID framework, focusing on sewage treatment issues. Despite some advancements in systems with varying dynamics, the event-triggered control mechanism in the neural network tuning PID framework remains inadequately addressed. This paper aims to fill this research gap by introducing an event-triggered mechanism into the concentration control of gas blending processes, in order to address the issues of frequent updates and insufficient accuracy faced by traditional methods.

It is noteworthy that in recent years, the field of intelligent control has shown a clear trend toward multi-structure integration, with a series of hybrid optimization strategies demonstrating significant potential in complex system applications. For instance, an SVD-TLS optimized dual-network recursive interval type-2 fuzzy neural network has improved the accuracy and robustness of fault diagnosis through structural innovation31; meanwhile, an interval type-2 fuzzy neural network-based sliding mode robust controller designed for magnetic spacecraft attitude control effectively combines the advantages of fuzzy reasoning and sliding mode control, achieving a higher level of control stability32. These studies not only verify the effectiveness of multi-method integration in enhancing system performance but also provide new ideas for addressing control challenges in complex industrial processes.

Against this research background, the proposed ET-FNN-PID method represents a significant advancement for industrial applications. By synergistically integrating event-triggered mechanisms, fuzzy logic reasoning, neural network learning, and PID control, this approach achieves coordinated optimization between control accuracy and operational efficiency. The method’s practical value is particularly evident in gas blending processes where it maintains high-precision control while reducing the controller update frequency by nearly 40%, offering substantial benefits for implementation on embedded platforms or PLCs with limited computational resources.

The proposed ET-FNN-PID controller offers the following key advantages: Structurally, it integrates an event-triggered mechanism with a fuzzy neural network PID, preserving the interpretability of fuzzy reasoning and the adaptability of neural networks, while significantly reducing computational and communication costs, making it suitable for deployment on embedded platforms. In terms of stability, although a fixed-threshold mechanism is adopted, theoretical analysis demonstrates the Input-to-State Practical Stability (ISpS) of the system and precludes the possibility of Zeno behavior. Compared to dynamic threshold strategies, this mechanism is more practical for industrial implementation. Regarding nonlinearity handling, the prediction model based on the TS fuzzy neural network accurately captures the dynamic nonlinear characteristics of the gas blending process, and the event-triggered mechanism further enhances the system’s robustness under time-varying operating conditions.

The principal contributions of this manuscript are summarized as follows:

-

1.

A two-level framework is proposed to address the challenge of nonlinear and time-varying gas-blending dynamics. A Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy neural network (TSFNN) is designed for data-driven process modeling, while a fuzzy neural network-based PID controller is employed to adaptively tune control parameters.

-

2.

To mitigate the problem of frequent and redundant controller updates, an event-triggered mechanism is incorporated into the FNN-PID structure. This design enables updates only when necessary, thereby reducing computational and communication burdens.

-

3.

To ensure the reliability of the proposed hybrid control structure, rigorous theoretical analysis is conducted. The analysis establishes ISpS and demonstrates the exclusion of Zeno behavior, providing a solid foundation for engineering implementation.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the gas power generation process and the proposed control strategy. Section 3 describes the modeling of the gas blending system and the event-triggered control design. Section 4 reports simulation studies with real.

Process description and control strategy for gas-fueled power generation

Gas power generation process and blending process

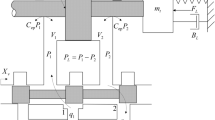

The gas power generation process, as depicted in Fig. 1, comprises five key stages: extraction, blending, supply, power generation, and transmission. Methane-rich gas is first extracted from underground mines using gas extraction pumps and transported via a pipeline network. High- and low-concentration gas streams converge in a blending unit, where they are thoroughly mixed to achieve a target concentration that meets the operational requirements of the gas generator set. The conditioned gas then passes through safety and preprocessing components, including flame arresters, dehydration systems, and additional piping, before being introduced into the gas generator for electricity production. The generated power is then increased via a transformer and integrated into the transmission grid.

Among the five stages of gas power generation, the gas blending stage is a critical prerequisite, as it directly determines whether power generation can proceed safely and efficiently. Precise control of gas concentration at this stage is therefore essential. The blending system uses gas concentration sensors and valves to perform real-time monitoring and control, as illustrated in Fig. 2. In this system, low-concentration gas is introduced into the mixing chamber at a constant flow rate, whereas high-concentration gas enters through a regulating valve according to a predefined ratio. After thorough mixing, a concentration sensor measures the concentration of the mixed gas and sends the data to a control processor. The processor compares the measured value with a predefined setpoint, calculates the error, and adjusts the valve opening accordingly. This closed-loop control ensures that the output gas consistently meets the required concentration specifications for stable and safe power generation.

Gas concentration control strategies

In the gas mixing concentration control process, the low concentration gas remains relatively stable with minimal fluctuations, as its dilute nature leads to gentle and predictable changes. In contrast, the high concentration gas exhibits significant and non-linear fluctuations as its concentration increases—these fluctuations are amplified by factors like molecular interaction intensity and sensitivity to environmental disturbances (e.g., temperature or pressure variations in the mixing chamber). Given that these fluctuations have the greatest impact on the final mixed gas concentration, the high-concentration gas flow becomes the most critical controllable factor. Thus, maintaining the mixed gas concentration within a desired range can be achieved effectively by adjusting the flow rate of the high-concentration gas.

To enable precise control during blending, this study proposes an event-triggered fuzzy neural network PID (ET-FNN-PID) control strategy, as illustrated in Fig. 3. This strategy addresses the limitations of manual control (such as low precision and poor stability) by enabling online adaptive tuning of PID parameters. It consists of three key components: FNN parameter update design (to adaptively adjust PID gains based on real-time errors), event-triggered mechanism design (to optimize computational efficiency by triggering updates only when necessary), and the overall control system architecture (integrating the above components into a closed-loop framework for stable regulation).

In this control framework, e denotes the gas concentration control error, while ec represents the rate of change of the error. The variable \(y_r\) refers to the desired value (setpoint) of the mixed gas concentration, and \(y_o\) indicates the actual output concentration of the mixing model. The variable u represents the flow rate of the high-concentration gas and \(\Delta u\) denotes the increase in control generated by the controller. ET stands for the event-triggering mechanism. The terms \(k_p\), \(k_i\), and \(k_d\) correspond to the proportional, integral, and derivative gains of the PID controller, respectively.

Modeling and control of gas concentration control system

Variable selection based on expert knowledge

In the gas blending process, when the flow of low-concentration gas remains relatively stable, both the real-time concentration and the flow rate of the high-concentration gas significantly influence the resulting mixed-gas concentration. Due to the time-varying and non-linear characteristics of the high concentration gas extracted from mines, its concentration cannot be characterized by a fixed value, and its real-time flow rate becomes a critical factor in achieving accurate blending. Therefore, based on expert knowledge from field operations, the key input variables for modeling the gas blending concentration are identified as the flow rates of low- and high-concentration gases, along with the real-time concentration of the high-concentration gas. In this study, a gas mixing concentration model is developed using actual operational data from the gas mixing process.

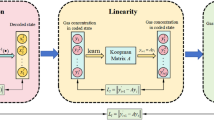

Gas concentration modeling strategy based on TSFNN network

On the basis of the above analysis, the low-concentration gas flow, high-concentration gas flow, and the real-time concentration of the gas involved in the blending were selected as input variables, while the mixed gas concentration after the blending was chosen as the output variable. Given the strong non-linear characteristics of the gas blending process, the Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy neural network (TSFNN), known for its powerful nonlinear approximation capability, was adopted to develop the gas blending concentration control model. The modeling strategy is illustrated in Fig. 4, and the structure of the TSFNN is depicted in Fig. 5.

We build a Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy neural network (TSFNN) to model the gas-blending process (multi-input single-output). The inputs are the low-concentration flow \(q_L(k)\), the high-concentration flow \(q_H(k)\), and the incoming gas concentration \(c_{\textrm{in}}(k)\); the output is the blended concentration \(c_{\textrm{out}}(k)\).

Let each input have M linguistic terms; then the rule count is

The calculation process of the fuzzy logic component is as follows. It realizes a complete mapping from precise input to fuzzy inference and then to precise output, serving as the core of the controller for handling uncertainty and nonlinearity. Taking the \(l\)-th fuzzy rule as an example, its calculation process is detailed below:

First, the precise input variable \(x_i(k)\) (representing the input value at the \(k\)-th time step) is converted into membership degrees belonging to different fuzzy sets via a Gaussian membership function. For the input variable \(i\) and its corresponding \(j\)-th fuzzy linguistic term, the membership degree at the \(k\)-th time step is calculated by the formula:

where \(c_{ij}(k)\) denotes the center of the membership function at the \(k\)-th time step, and \(\sigma _{ij}(k)\) determines the width of the function at the \(k\)-th time step. This step transforms each precise input value at the current time step into a membership degree ranging between 0 and 1.

Second, the firing strength \(\alpha _l(k)\) of the \(l\)-th rule at the \(k\)-th time step is calculated,rule \(l\in \{1,\dots ,L\}\) corresponds to a tuple of term indices \(\big (j_1(l),j_2(l),j_3(l)\big )\).Assuming the antecedent of a rule consists of multiple sub-conditions connected by “AND”, its firing strength at the \(k\)-th time step is the product of the membership degrees corresponding to each input at the same time step (i.e., product inference engine):

The firing strength \(\alpha _l(k)\) characterizes the degree to which the current input at the \(k\)-th time step satisfies the antecedent conditions of the \(l\)-th rule, reflecting the real-time applicability of the rule.

To avoid deviations that may be caused by absolute firing strengths at the \(k\)-th time step, the firing strengths of all \(L\) rules at the same time step are normalized to obtain the normalized activation degree \(\beta _l(k)\):

Normalization ensures that the sum of the activation degrees of all rules at the \(k\)-th time step equals 1 (\(\sum _{l=1}^L \beta _l(k) = 1\)), reflecting the relative weight of each rule in the final output at the current time step.

The consequent network of the TSFNN is used to generate rule-specific local outputs and perform defuzzification, converting fuzzy inference results into precise outputs usable for discrete-time dynamic systems . process is as follows:

The local output \(\hat{y}_l(k)\) of each rule \(l \in \{1,\dots ,L\}\) at the \(k\)-th time step is an affine function of the 3 input variables (\(i \in \{1,2,3\}\)):

where \(a_{l0}(k), a_{l1}(k), a_{l2}(k), a_{l3}(k)\) are time-varying parameters of the rule at the \(k\)-th time step.

Local outputs of all rules are aggregated using their normalized activation degrees \(\beta _l(k)\) as weights, yielding the TSFNN’s final output—the predicted blended concentration \(\hat{c}_{\textrm{out}}(k)\):

Given measured \(c_{\textrm{out}}(k)\), we minimize the instantaneous squared error

and update parameters \(\{c_{ij},\sigma _{ij},a_{l0},a_{li}\}\) by gradient-based methods (or solve \(\{a_{l\cdot }\}\) by least squares with fixed \(\beta _l(k)\)).

Controller TS-FNN and event-triggered incremental PID

The tracking error and its first difference are defined as

The controller network inputs are

Each input is described by M linguistic terms, yielding a total of \(L=M^2\) fuzzy rules. Gaussian membership functions are used for input \(i\in \{1,2\}\) and term \(j\in \{1,\dots ,M\}\):

with center \(c_{ij}\) and width \(b_{ij}>0\). A rule \(l\in \{1,\dots ,L\}\), corresponding to a pair of terms \(\big (j_1(l),j_2(l)\big )\), is activated with strength

Normalized firing strengths are then obtained as

The TS-FNN outputs the PID gain increments via a linear readout:

Gains are updated by accumulation

The nominal incremental PID control law (driving the event trigger) is

From a design perspective, the control law in (16) implicitly embeds the performance specifications. In particular, the gains \(K_P,K_I,K_D\) are tuned so as to minimize a quadratic objective of the form

which balances tracking accuracy against actuation smoothness. This criterion provides a systematic way to impose performance requirements on the closed-loop response.

Let \(\{k_t\}_{t\in {\mathbb {N}}}\) be the strictly increasing sequence of event times and \(Q>0\) a fixed threshold. Between events the applied input is held:

A constant-threshold event rule acts on the increment:

Equivalently, the next event time is

and the inter-event time is

The condition \(|\Delta u^{\textrm{nom}}(k)|>Q\) can be interpreted as a resource-aware constraint in the optimization problem: control updates are executed only when the nominal increment improves J, thereby reducing unnecessary updates without sacrificing performance. Triggering on the increment \(\Delta u^{\textrm{nom}}(k)\), rather than directly on the error or state, ensures the actuation mismatch relative to ideal updates is bounded by Q, which directly matches the stability bounds.

The stopping condition \(k < 500\) in Algorithm 1 is determined by the simulation setup. With \(T_{\text {total}}=60\) minutes and sampling interval \(\Delta t=0.1\) minutes, there are \(K = 600\) possible samples. The loop length of 500 ensures the algorithm terminates after capturing the system’s responses to the set-point steps at \(t=20\) and \(t=40\) minutes and provides sufficient time for convergence.

Within each iteration, the updates of the TS-FNN parameters and the PID gains can be interpreted as solving the optimization problem described above. This is achieved through a momentum-based gradient descent scheme, in which the learning rates \((\eta _c,\eta _b,\eta _w)\) and the momentum factor \(\alpha\) regulate convergence speed and stability. In this way, the simulation not only reproduces the transient and steady-state behavior of the closed-loop system but also illustrates the role of the optimization algorithm in shaping controller adaptation.

Computational complexity analysis

The core advantage of the event-triggered mechanism lies in significantly reducing the computational burden of the system. To quantify this advantage, we analyze the computational complexity of the control algorithms for the ET-FNN-PID and the traditional time-triggered FNN-PID.

At each sampling period k, the time-triggered FNN-PID must fully execute one forward propagation (Equations (8)–(12)) and one backpropagation learning (Equations (14)–(16)) to update the network parameters and PID parameters. Assuming the fuzzy neural network (FNN) has R rules and N input variables, the computational complexity of each forward propagation is approximately \(O(N \cdot R)\), and the learning complexity of backpropagation is approximately O(R). Therefore, for a total of \(K=500\) sampling points within the entire simulation duration, the total computational complexity is \(O(500 \cdot (N \cdot R + R))\).

In contrast, the ET-FNN-PID executes complete FNN calculations and parameter updates only when the triggering condition \(|\Delta u(k)| \ge Q\) is satisfied. At non-triggered sampling points, the system only needs to perform the following low-complexity operations:

-

1.

Collect the current output y(k), and calculate the error e(k) and error change ec(k).

-

2.

Compute the control increment \(\Delta u(k)\) according to Equation (21).

-

3.

Determine the triggering condition: \(|\Delta u(k)| \ge Q\)

-

4.

If not triggered, directly output the control signal from the previous moment: \(u(k) = u(k-1)\).

The complexity of these operations can be approximated as O(1). As shown in Fig. 9, the controller was only triggered at 312 sampling points in this simulation. Thus, the total computational complexity of the ET-FNN-PID is approximately \(O(312 \cdot (N \cdot R + R) + 188 \cdot 1)\). Compared with the time-triggered approach, the computational load is reduced by nearly 40%, which is consistent with the reduction ratio of controller update times. This improvement in computational efficiency makes the proposed method more feasible for implementation on embedded platforms or PLCs with limited computational resources.

Analysis

Consider the discrete-time nonlinear SISO plant

with bounded reference \(r_k\) and tracking error \(e_k:=r_k-y_k\). The controller is incremental,

and employs an event trigger with threshold \(Q>0\), i.e., the update is applied if \(|\Delta u^{\textrm{nom}}_k|>Q\), otherwise \(u_k\) is held constant.

The parameter update follows a momentum-based projected gradient rule,

where \(0\le \beta <1\), \(\eta >0\), \(\Vert \nabla _\theta J_k\Vert \le {\bar{g}}\), and the feasible set is \(\Theta =\{\theta :\Vert \theta \Vert \le {\bar{\theta }}\}\).

Theorem 1

(Minimum Inter-Event Time (No-Zeno)) Under the setup above, there exists a finite constant \(L_{\Delta u}\) such that

and every inter-event time \(\tau _i\) satisfies

Hence Zeno behavior (infinitely many events in finite time) is impossible in sampled time.

Proof

From the momentum update \(v_{k+1}=\beta v_k-\eta \nabla _\theta J_k\) with \(\Vert \nabla _\theta J_k\Vert \le {\bar{g}}\),

Projection keeps the parameters bounded, \(\Vert \theta _k\Vert \le {\bar{\theta }}\) for all k.

Consider the one-step change of the nominal increment:

Along bounded trajectories we have \(\Vert \phi _k-\phi _{k-1}\Vert \le c_\phi\) and \(\Vert \phi _k\Vert \le {\bar{\phi }}\), while

Therefore,

Immediately after an update, if \(|\Delta u^{\textrm{nom}}|\le Q\), the next event can occur only after \(|\Delta u^{\textrm{nom}}|\) crosses the threshold Q. Since the per-sample growth of \(|\Delta u^{\textrm{nom}}|\) is at most \(L_{\Delta u}\), at least \(\lceil Q/L_{\Delta u}\rceil\) sampling steps are required. Because time is discrete,

Hence every inter-event time is uniformly lower bounded, and Zeno behavior (infinitely many events in finite time) is impossible. \(\square\)

Theorem 2

(Input-to-State Practical Stability) Under the setup above, there exist \(P=P^\top \succ 0\) and constants \({\underline{\alpha }},\kappa _1,\kappa _2,\kappa _3>0\) such that

Proof of ISpS

Construct the Lyapunov function

Under the assumed output and input Lipschitz properties of the plant and bounded \(({\bar{w}},{\bar{\varepsilon }})\), the hold mode (\(u_k=u_{k-1}\)) satisfies

which implies the drift inequality for some \(\alpha _{\textrm{H}},c_{\textrm{H}}>0\),

For the update mode (\(u_k=u_{k-1}+\Delta u^{\textrm{nom}}_k\)), consider the ideal increment \(\Delta u_k^\star\) yielding

Input Lipschitzness gives

Because the trigger acts on \(\Delta u^{\textrm{nom}}_k\) and both the regressor and gains are bounded, the actuation mismatch obeys

so for some \(\alpha _{\textrm{U}},c_Q,c_\theta ,c_{\textrm{U}}>0\),

Let

The no-Zeno result ensures a uniform lower bound on inter-event times, preventing chattering; combining the two mode drifts yields the per-step bound

A standard discrete comparison argument then provides an ultimate bound for \(V_k\) proportional to the constant term on the right, which implies

for suitable positive constants \({\underline{\alpha }},\kappa _1,\kappa _2,\kappa _3\). This establishes input-to-state practical stability. \(\square\)

In adaptive control systems, it is crucial to distinguish between convergence and stability. Stability (determined via ISpS analysis) ensures that system trajectories remain bounded under disturbances, while convergence refers to the asymptotic behavior of tracking errors and parameters. The proposed controller guarantees stability through an event-triggering mechanism and Lyapunov analysis, whereas gradient-based learning ensures that parameters converge to optimal values, thereby minimizing tracking errors.

Results

Physical model and synthetic-data generation

All simulations start from a unified initial condition to compare the performance of different controllers: the flow rate of low-concentration gas \(Q_1 = 100 \, \text {m}^3/\text {h}\), the flow rate of high-concentration gas \(Q_2 = 0 \, \text {m}^3/\text {h}\), and the initial value of methane concentration in the mixed gas is 5%. This initial condition represents a safe stationary state of the system. To clarify the setup of the simulation and control methods, Table 1 presents the key parameters for the gas mixing model, the TSFNN (Triangular Sugeno Fuzzy Neural Network) model, and the ET-FNN-PID controller. For the gas mixing model, parameters like gas flow rates, target methane concentration, and environmental conditions (temperature, pressure) define the system under study. The TSFNN model’s parameters, including the number of input variables, fuzzy rules, and membership function, shape the fuzzy neural network’s structure and behavior. Meanwhile, the ET-FNN-PID controller parameters, such as initial PID gains, learning rates, momentum factor, and event-triggered threshold, determine the controller’s initialization and adaptive learning process, as well as the conditions for triggering control updates. These parameters collectively establish the foundation for the subsequent control performance evaluation.

The mixing of gaseous species s is modeled as an adiabatic well-mixed junction governed by semi-perfect gas thermodynamics.

State equation and species properties. Each species k obeys \(p=\rho _k R_k T\), with temperature-dependent property tables \(c_{p,k}(T)\), \(h_k(T)\), \(\mu _k(T)\) and \(k_k(T)\). Mixture properties follow linear mixing rules

where \(Y_k\) and \(X_k\) are the mass and mole fractions of species k in the mixture, respectively.

Steady mixing node. For n inlet streams with known \((\dot{m}_i, p_i, T_i, Y_{k,i})\), the outlet state \((p_\text {out}, T_\text {out}, Y_{k,\text {out}})\) is determined by the following balance equations:

where \(\dot{m}_i\) is the mass flow rate of inlet i, and \(Y_{k,i}\) is the mass fraction of species k in the ith stream.

Dynamic tracer filling. When considering a finite control volume V, the time evolution of passive-tracer mass fractions is described by:

where \(\rho\) is the mixture density and \(Y_k\) is the mass fraction of species k in the control volume. Here, p denotes the pressure, T the temperature, \(\rho\) the density, \(\dot{m}\) the mass flow rate, and \(h_m\) the mixture enthalpy. The parameters \(R_m\), \(c_{p,m}\), \(\mu _m\), and \(k_m\) represent the mixture gas constant, specific heat at constant pressure, dynamic viscosity, and thermal conductivity, respectively. The subscripts k and i refer to species and inlet branch, respectively.

The mixing node receives two gas streams: Inlet 1 is low–concentration mine gas delivered at \(Q_{1}=100~\text {m}^{3}\,\text {h}^{-1}\) with fixed composition \((Y_{\text {CH}_4},Y_{\text {N}_2},Y_{\text {O}_2},Y_{\text {CO}_2},Y_{\text {CO}},Y_{\text {H}_2\text {O}})=(0.05,0.88,0.03,0.02,0.01,0.01)\); Inlet 2 is a high–concentration stream with methane mass fraction \(Y_{\text {CH}_4}=0.35\) whose flow rate \(Q_{2}\in [0,150]~\text {m}^{3}\,\text {h}^{-1}\) is commanded by a feed-forward neural network to achieve a \(12~\%\) methane target at the outlet. Operation is isothermal and isobaric at \(T=298.15~\text {K}\) and \(p=101{,}325~\text {Pa}\), so the semi-perfect-gas state equation and the species property tables introduced earlier apply directly. A 60-min simulation with step size \(\Delta t=0.1~\text {min}\) is run, during which two disturbances are imposed: (i) a stochastic \(\pm 1~\%\) fluctuation on the methane fraction of Inlet 1 each time step, and (ii) set-point steps from \(12~\%\) to \(15~\%\) at \(t=20~\text {min}\) and to \(10~\%\) at \(t=40~\text {min}\).

Steady-state error

where \(e(t) = y_{\textrm{ref}} - y(t)\) is the tracking error, \(y_{\textrm{ref}}\) is the reference value, and \(y(t)\) is the system output. This metric quantifies the final deviation from the desired setpoint.

Maximum overshoot

This metric indicates the maximum positive deviation of the output from the setpoint, reflecting the system’s tendency to overshoot.

Integral of Absolute Error (IAE)

where \(\Delta t\) is the sampling interval and \(T = N\Delta t\) is the evaluation period. IAE quantifies the cumulative tracking error over time.

Root-Mean-Square Error (RMSE)

RMSE provides a scale-sensitive measure of the average squared error, giving more weight to large deviations.

Control smoothness

where \(u[k]\) is the control signal at time step \(k\), and \(\bar{u}\) is the mean control signal. A smaller \(\sigma _u\) indicates smoother control action and less actuator strain.

Average learning error

where \(\varepsilon [k]\) represents the instantaneous update magnitude from the online learning module at time step \(k\). This metric evaluates the adaptation effort of the learning mechanism.

All metrics are computed over the simulation window \(0 \le t \le T\), based on the discrete sequences \(e[k]\) and \(u[k]\), sampled at time \(t = k \Delta t\). Together, they comprehensively assess the closed-loop performance of the controller.

Performance evaluation of the neuro–fuzzy control strategy

Figure 6 illustrates that the neuro–fuzzy controller attains rapid error convergence while ensuring stable set-point tracking through adaptive weight tuning. In Fig.6(a) , as the control error shifts from positive to negative, the network weight decreases from 0.85 to 0.60, whereas the methane volume fraction rises from roughly 9 % to 16 %. These variables exhibit a clear negative correlation (\(r\!\approx \!-0.9\)), confirming that the weight-update mechanism finely regulates the concentration. Figure 6(b) reveals three distinct output phases—start-up ramp, oblique transition, and steady maintenance. Within 15 min the flow rate stabilises at 50–55 \(\textrm{m}^{3}\,\textrm{h}^{-1}\) with a steady-state error below 1 %. During the transition, neural-network and fuzzy-logic outputs remain synchronised, curbing overshoot and oscillations. Collectively, these results demonstrate that the proposed neuro–fuzzy architecture combines fast transient response with high steady-state accuracy and robustness.

The result for Fig. 7 is designed to compare and evaluate the set-point tracking performance of different controllers under step changes. To highlight the dynamic response characteristics of each controller, the methane concentration set-point was stepped up from 12% to 15% at \(t = 20\ \text {min}\), and then stepped down to 10% at \(t = 40\ \text {min}\). The primary objective of this result is to examine the controllers’ response speed, overshoot suppression, and steady-state recovery accuracy under significant changes in operating conditions. The figure compares the output response curves of the conventional PID controller, the pure Neural Network (NN) controller, and the proposed ET-FNN-PID controller, with their quantified performance metrics detailed in Table 2.

Although Fig. 7 demonstrates that both the PID and stand-alone neural-network (NN) controllers can eventually drive methane concentration toward the set-point, their dynamic responses reveal structural weaknesses that render them sub-optimal for the present, highly nonlinear gas-mixing process. Specifically, the PID loop (Fig. 7(a) ) shows a sluggish, quasi-integrating ramp after each step change and even drifts under the second set-point, indicating gain–phase constraints and integral wind-up when faced with the system’s large dead-time and variable gain; such fixed-gain linear control cannot adapt to the strong operating-point dependence observed in Fig. 8. Conversely, the pure NN controller (Fig. 7(b) ) accelerates the transient, but its output is accompanied by pronounced overshoot, high-frequency jitter and marginal damping (see also the blue dotted trace in Fig. 8(b) ), symptoms of over-fitting to nominal conditions, lack of explicit stability guarantees and susceptibility to measurement noise. Together these results clarify why neither PID (too rigid and slow) nor NN (too aggressive and noisy) meets the combined requirements of fast tracking, low overshoot and robust steadiness—hence motivating the hybrid neuro–fuzzy strategy, which blends rule-based damping with data-driven adaptation to exploit the strengths and offset the weaknesses of both individual controllers.

Figure 8 further quantifies the controller’s flow-regulation performance under step disturbances. A first step at \(t\!\approx \!20\) min raises the set-point from 30 to 50 \(\textrm{m}^{3}\,\textrm{h}^{-1}\), while a second step at \(t\!\approx \!40\) min lowers it to 20 \(\textrm{m}^{3}\,\textrm{h}^{-1}\). In Fig. 8(a) the actual high-concentration gas flow reaches the new steady state within about 1.2 min and 1.5 min, respectively, with overshoot below 2 % and no sustained oscillation. This indicates that the controller can generate precise execution commands, achieving fast and well-damped closed-loop performance, which is of great significance for protecting physical actuators (such as control valves) and ensuring the stability of the mixing process.

Figure 8(b) contrasts neural-network output (red dashed), fuzzy-logic output (blue dotted) and hybrid output (black solid). Through the analysis of control signal decomposition to explore its internal working mechanism, it can be observed that the NN component produces an aggressive response to step changes and outputs sharp peaks to provide rapid correction. The FL component is responsible for fine adjustment but introduces high-frequency fluctuations of \(\pm 2\)–\(3~\textrm{m}^{3}\,\textrm{h}^{-1}\). However, the final output obtained through intelligent weighted fusion effectively suppresses the high-frequency noise of FL, smooths the aggressive peaks of NN, and generates a smooth control signal that is highly consistent with the actual flow rate. The weighted hybrid output suppresses both issues: its envelope nearly coincides with the measured flow and has the lowest variance (estimated \(<0.5~\textrm{m}^{3}\,\textrm{h}^{-1}\)). Hence, the hybrid strategy delivers rapid tracking and high steady-state precision while attenuating the noise and overshoot inherent to single-mode controllers.

Control result analysis

As summarized in Table 2, the hybrid ET-FNN-PID controller markedly outperforms its single-strategy counterparts. The conventional PID suffers from a sizeable steady-state error (1.167%) and the highest integral absolute error (IAE = 115.30) and RMSE (2.129%), indicating that its fixed linear gains cannot fully compensate for the pronounced nonlinearities and time-varying dynamics of the gas-flow process. Conversely, the standalone ET-FNN achieves excellent static accuracy (0.064%) and the smoothest control action (standard deviation = 0.72), yet its IAE (41.07) and RMSE (1.132%) remain substantially larger than those of the hybrid scheme, revealing that the neural network alone adapts too slowly when large transients occur. By embedding the ET-FNN as a nonlinear feed-forward compensator in front of a finely tuned PID feedback loop, the hybrid controller combines rapid error correction with real-time adaptation, driving the IAE down to 4.49 and the RMSE to 0.255% without sacrificing accuracy. Hence, the PID alone lacks sufficient adaptability, while the ET-FNN alone lacks robust transient suppression; only their synergistic integration delivers the requisite precision, speed, and stability for high-concentration gas-flow regulation.

In the traditional, time-based continuous control scheme the controller must be updated at every sampling instant—500 times in our test. By contrast, as shown in Fig. 9, the proposed event-triggered ET–FNN–PID controller needs only 312 updates, demonstrating a significant reduction in update frequency and thus in computational and communication burden. Compared with the conventional time-based continuous control, the ET–FNN–PID controller reduces its update count by almost 40 %. This reduction clearly illustrates the efficacy of the event-triggered mechanism in alleviating computational and communication loads. Figure 10 depicts the inter-event intervals: the maximum interval spans 9 samples, the minimum is 1 sample, and the mean interval is 1.6026 samples. Thus, unlike the rigid periodic updates of time-triggered control, the event-triggered scheme adapts dynamically to the system’s state, invoking controller updates only when warranted by the error dynamics.

To demonstrate the superiority of the ET-FNN-PID method, based on the parameters in Table 2 and the experimental results in Fig. 9, the percentage improvements of the ET-FNN-PID method over the traditional PID and standard FNN-PID methods in key performance indicators were calculated, with the specific results presented in Table 3. Quantitative analysis shows that the ET-FNN-PID controller achieves significant improvements in all key performance indicators.In particular, the improvements in integral error and RMSE exceed 77%. This result quantitatively proves the practical effectiveness of the proposed hybrid control strategy in the coordinated optimization of control accuracy and resource utilization efficiency.

Although the proposed ET-FNN-PID controller exhibits superior performance compared to the baseline controllers (Tables 2-3), these results do not stem from overfitting. The hybrid architecture inherently mitigates overfitting risks through multiple mechanisms: (1) the event-triggering mechanism prevents excessive parameter updates; (2) fuzzy logic provides interpretable rule-based reasoning; (3) the controller has been validated under various disturbance scenarios and set-point changes. Future work will include large-scale validation across diverse gas-blending scenarios to further confirm the generalization capability of this method.

Conclusion

To address the issues of low control accuracy and frequent controller updates in the gas blending concentration control process, this study establishes a gas concentration prediction model using a Takagi–Sugeno fuzzy neural network (TSFNN) and designs an event-triggered fuzzy neural network PID (ET-FNN-PID) controller based on this model. Experimental validation using real operational data yields the following conclusions: The TSFNN model accurately captures the non-linear characteristics of the gas blending process, as demonstrated by the close match between the predicted outputs and actual measurements. This confirms the modeling effectiveness of TSFNN and eliminates the need for complex mechanism-based models. The proposed ET-FNN-PID controller enables online adjustment of PID parameters, thereby improving control accuracy and dynamic performance while reducing actuator wear. In addition, the event-triggering mechanism, based on a fixed threshold, ensures that control actions are executed only when necessary. This not only maintains control performance, but also significantly reduces the frequency of controller updates, thereby minimizing unnecessary resource consumption.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Liu, Y. et al. Simulation study on catalytic oxidation of low concentration mine gas in an oxidation device. Sci. Rep. 15, 25 (2025).

Bai, E. et al. Control effect of overburden grout injection on surface subsidence and groundwater quality pollution. Bull.Eng. Geol. Environ. 83, 387 (2024).

Xu, H. et al. Combustion characteristics of low-concentration coal mine gas with metal fiber burners. Case Stud. Therm.Eng. 63, 105256 (2024).

Zhang, Q. Process technology and design research of intelligent mixing system for low concentration gas based on s7–1200. Min. Saf. Environ. Prot. 46, 79–83 (2019).

Skabelund, B. B., Jenkins, C. D., Stechel, E. B. & Milcarek, R. J. Thermodynamic and emission analysis of a hydrogen/methane fueled gas turbine. Energy Convers. Manag.: X 19, 100394 (2023).

Precup, R.-E., Nguyen, A.-T. & Blažič, S. A survey on fuzzy control for mechatronics applications. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 55, 771–813 (2024).

Zhu, Y., Yu, W. & Li, X. A multi-objective transfer learning framework for time series forecasting with concept echo state networks. Neural Networks 186, 107272 (2025).

Zhang, Z., Zhu, Y., Wang, X. & Yu, W. Optimal echo state network parameters based on behavioural spaces. Neurocomputing 503, 299–313 (2022).

Zhu, Y., Liu, Y., Zhang, Z. & Yu, W. Optimized echo state network for error compensation based on transfer learning. Appl. Soft Comput. 174, 112935 (2025).

Zhu, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, N., Zhang, Z. & Li, Y. Real-time error compensation transfer learning with echo state networks for enhanced wind power prediction. Appl. Energy 379, 124893 (2025).

Wu, J. et al. Data-driven remaining useful life prediction via multiple sensor signals and deep long short-term memory neural network. ISA transactions 97, 241–250 (2020).

Carron, A. et al. Data-driven model predictive control for trajectory tracking with a robotic arm. IEEE Robotics Autom.Lett. 4, 3758–3765 (2019).

Roman, R.-C., Precup, R.-E., Petriu, E. M. & Borlea, A.-I. Hybrid data-driven active disturbance rejection sliding mode control with tower crane systems validation. Romanian J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 27, 50–64 (2024).

Yue, J., Liu, Z. & Su, H. Data-driven adaptive extended state observer-based model-free disturbance rejection control for dc–dc converters. IEEE Transa. Ind. Electron. 71, 7745–7755. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIE.2023.3317860 (2024).

Luy, N. T., Thanh, N. T. & Tri, H. M. Reinforcement learning-based intelligent tracking control for wheeled mobile robot. Trans. Inst. Meas. Control. 36, 868–877 (2014).

Zamfirache, I. A., Precup, R.-E. & Petriu, E. M. Adaptive reinforcement learning-based control using proximal policy optimization and slime mould algorithm with experimental tower crane system validation. Appl. Soft Comput. 160, 111687 (2024).

Hentout, A., Maoudj, A. & Kouider, A. Shortest path planning and efficient fuzzy logic control of mobile robots in indoor static and dynamic environments. Romanian J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 27, 21–36 (2024).

Zhao, D., Wang, Z., Wei, G. & Han, Q.-L. A dynamic event-triggered approach to observer-based pid security control subject to deception attacks. Automatica 120, 109128 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Dai, Q. & Zhu, Y. A multi-model prediction method for coal mine gas concentration with hierarchical structure. Appl. Artif. Intell. 36, 2146296 (2022).

Jin, G.-G. & Son, Y.-D. Design of a nonlinear pid controller and tuning rules for first-order plus time delay models. Stud.Informatics Control. 28, 157–166 (2019).

He, F. et al. Transient behavior of fuzzy pid-controlled transpiration cooling with phase change under dynamic thermal environments. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 217, 110088 (2025).

Borase, R. P., Maghade, D., Sondkar, S. & Pawar, S. A review of pid control, tuning methods and applications. Int. J. Dyn.Control. 9, 818–827 (2021).

Li, H., Fan, D., Hu, X. & Zhou, S. Research on improved bp neural network pid controller in gas concentration control. J. Sichuan Uni. Nat. Sci. Edit 57, 1103–1109 (2020).

Shi, Q., Lam, H.-K., Xuan, C. & Chen, M. Adaptive neuro-fuzzy pid controller based on twin delayed deep deterministic policy gradient algorithm.. neurocomputing 402, 183–194 (2020).

Wang, Z., Yao, X., Li, T. & Zhang, H. Design of pid controller based on echo state network with time-varying reservoir parameter. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 52, 6615–6626 (2021).

Chen, L., Wang, Y.-W., Yang, W. & Xiao, J.-W. Robust consensus of fractional-order multi-agent systems with input saturation and external disturbances. Neurocomputing 303, 11–19 (2018).

Jetto, L. & Orsini, V. A new event-driven output-based discrete-time control for the sporadic mimo tracking problem. Int.J. Robust Nonlinear Control. 24, 859–875 (2014).

Boruah, N. & Roy, B. Event triggered nonlinear model predictive control for a wastewater treatment plant. J. WaterProcess. Eng. 32, 100887 (2019).

Du, S.-L., Liu, T. & Ho, D. W. Dynamic event-triggered control for leader-following consensus of multiagent systems. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 50, 3243–3251 (2018).

Du, S., Yan, Q. & Qiao, J. Event-triggered pid control for wastewater treatment plants. J. Water Process. Eng. 38, 101659 (2020).

Zhao, N., Zhao, T., Cao, J. & Shi, H. Fault diagnosis of dual-network recursive interval type-2 fuzzy neural network based on svd-tls optimization. Comput. Ind. Eng. 207, 111280 (2025).

Liu, X., Zhao, T., Cao, J. & Li, P. Design of an interval type-2 fuzzy neural network sliding mode robust controller for higher stability of magnetic spacecraft attitude control. ISA Transactions 137, 144–159 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Joint Fund Project of the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province and Shaanxi Coal and Chemical Industry Group (Grant No. 2019JLZ-08), and the Natural Science Basic Research Program of Shaanxi Province (Grant Nos. 2020JM-522 and 2021JM-396).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.D. conceived the methodology, implemented the software, performed the formal analysis, and drafted the original manuscript. S.W. supervised the study and contributed to writing—review and editing. Z.Z. secured funding and assisted in the manuscript review. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dong, W., Wang, S. & Zhang, Z. Event-triggered fuzzy neural-network PID control for nonlinear gas-blending processes. Sci Rep 15, 40309 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23998-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-23998-6