Abstract

As the size of the device continues to decrease due to the increasing demand for faster processing speed and lower power consumption in semiconductor integrated circuit device technology, the double patterning process is widely used. The SiNx used in this double patterning process requires high etch rate and high etch selectivity over SiOx, while at the same time achieving an anisotropic etch profile. In the past, gases such as CHF3/CF4 were used for SiNx etching of double patterning. However, the low etch selectivity of these gases and their high global warming potential (GWP) have led to the need for alternative gases. To address this issue, in this study, the effect of alternative gases instead of CHF3 on SiNx etching characteristics has been investigated. When C2H2F4 was used instead of CHF3, both etch rate and etch selectivity were improved, but issues such as trenching and increased critical dimension (CD) were observed. When CF4O was added to C2H2F4, both etch rate and etch selectivity were further improved while eliminating trenching issue. The analysis showed that C2H2F4 compared to CHF3 promoted stronger polymer formation, thereby improving mask passivation while trenching defects occurred due to polymer deposition. For the C2H2F4 + CF4O mixture, increased fluorine dissociation resulted in higher SiNx etch rates and consequently better etch selectivity, and trenching was eliminated by increasing gas dissociation and decreasing polymer production. Million Metric Tones of Carbon Equivalent (MMTCE) measurements showed that C2H2F4 decreased by approximately ~83.9% and C2H2F4 + CF4O by approximately ~75.2% of greenhouse gas emissions compared to CHF3. Therefore, the results obtained with alternate gases are next-generation eco-friendly etch processes that can be applied to semiconductor devices such as Fin Field Effect Transistor (FinFET), 3D Not-AND (NAND), and other advanced semiconductor and display manufacturing technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today, SiNx and SiOxoffer high performance at low cost with excellent insulating properties and high breakdown strength1,2,3,4,5. These advantages have led to their widespread use in applications such as Fin Field-Effect Transistors (FinFETs) and Not-AND (NAND) that require high electrical performances6,7,8,9,10,11. In recent years, the size of devices has been steadily decreasing due to the continuous increase in demand for faster processing speeds and lower power consumption, and, to reduce device sizes below the photolithography wavelength limit, double patterning techniques are widely used12,13. The double patterning process requires a highly selective etching process by using an insulated upper hard mask instead of amorphous carbon layer (ACL) or bottom anti-reflective coating (BARC) layer2,14,15,16,17. This allows for the removal of unnecessary bottom layers through high etch selectivity, reducing process time and double patterning defects, leading to cost savings. In particular, increasingly complex and precise semiconductor etch processes require deeper SiNx etching than ever before, requiring high etch selectivity between SiNx and SiOx18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. This is because employing a highly selective etching process between SiNx and SiOx can effectively eliminate the multiple etching steps that are typically required in conventional double patterning techniques. Therefore, the objective of this study is to enhance process efficiency through the implementation of highly selective etching between SiNx and SiOx, which removes the necessity for multiple etching sequences commonly employed in traditional double patterning approaches.At present, SiNx is etched using gases with high global warming potential (GWP) gases such as NF3/O2, CHF3/O2/Ar, CHF3/CH3F/CH2F2/Ar, N2/O2/CF4, SF6/H2/He/Ar as etchants16,26,27,28. However, CHF3, CF4, SF6, and NF3have high GWPs. With the development of next-generation etch processes, these high GWP gases must be replaced by lower GWPs29,30,31,32. To address this issue, a relatively low GWP gas, C2H2F4 (HFC-134a), is being considered as a potential alternative to CHF3. However, it is still high and needs further improvement.In this study, the applicability of C2H2F4 to SiNx etch process as a replacement of CHF3 using inductively coupled plasma (ICP) during the double patterning process that requires selective etch compared to SiOx and highly anisotropic etch profiles has been investigated, and, in addition, the effect of CF4O addition to C2H2F4 on the SiNx etch characteristics has been studied. Because CF4O helps suppress excessive polymer formation and improve profile control, it was added to C2H2F4. Its low GWP, combined with its ability to increase F and O radicals in the plasma, makes it an effective additive for enhancing SiNx etching performance while reducing environmental impact. First, it was shown that replacing CHF3 with C2H2F4 improves etch selectivity over SiOx; however, it also resulted in an undesirable increase in critical dimension (CD) and the formation of etch profile defects such as trenching, which are considered negative effects in terms of pattern fidelity and process reliability. However, the addition of CF4O solved these etch issues, further improving etch rate and selectivity. In addition, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) analysis showed that SiNx etch processes with C2H2F4 containing CF4O improved Million Metric Tons of Carbon Equivalent (MMTCE) values when etching SiNx of the same thickness compared to conventional CHF3 processes.

Experimental

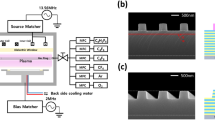

The 300 mm inductively coupled plasma (ICP) system used in the study is shown in Fig 1(a). The ICP source consists of an antenna consisting of two copper coils, one inside and one on the outside. A ~35mm thick alumina window was installed above the electrode to pass the electromagnetic field formed from the antenna into the chamber, and in addition to a gas ring located at the top edge of the chamber wall for injecting gas from the side, a gas hole was made in the center of the alumina window for uniform gas distribution in both the center and the edge. The substrate was placed on the powered lower electrode of the ICP system, which was equipped with active cooling using a chiller system. The distance between the substrate surface (placed on the powered lower electrode) and the ICP source region was approximately ~15 cm. The ICP power to the antenna is delivered by a 13.56 MHz radio frequency (RF) generator (Seren-R3001), and the bias power to the substrate is supplied by a 2 MHz RF generator (Seren-R2001). To regulate the process pressure, the chamber is equipped with an automatic process pressure controlling pendulum valve (VAT model PM.7) between the turbopump and the dry pump. At the downstream of the dry pump, an FT-IR (MIDAC, I2000) was installed to measure the recombination gas species. The experiment was performed with a sample of SiNx (200nm) patterned with SiOx (110nm) on a silicon wafer. The critical dimension (CD) of the SiOx hardmask was ~73 nm and the space between patterns was ~71 nm. A SEM cross-sectional image of SiOx patterned on SiNx is shown in Fig 1(b). The SiOx patterned SiNx etch process was performed under the conditions of an ICP source power of 1500 W with 13.56 MHz RF power, a DC bias of −100 V with the 2 MHz RF power, a process pressure of 4 mTorr, and a substrate temperature of 18 °C. The total gas flow rate was maintained at 340 sccm, consisting of CH3F (40 sccm), O2 (90 sccm), and He (100 sccm) supplied in common, together with either CHF3 (110 sccm), C2H2F4 (110 sccm), or a mixture of C2H2F4 (80 sccm) + CF4O (30 sccm) as the main etchant gas. The etch rate and selectivity, and the etch profile of SiOx patterned SiNx were examined using the field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM; Hitachi, S-4700), and SEM was also used to measure CD. The plasmas produced by the dissociation of hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) and perfluorocarbon (PFC) gases were observed by optical emission spectroscopy (OES; ANDOR, Technology SR-ASZ-0103). In addition, radicals and cations were measured using quadrupole mass spectrometry (QMS; Hiden Analytical, PSM 500). The surface composition and binding states were measured by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; VG Microtech Inc. ESCA2000). Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR; MIDAC, I2000) was used to measure the molecular species emitted outside of the process chamber and to calculate the total global warming potential of the process gases, Million Metric Tons of Carbon Equivalent (MMTCE) values, used in the experiment.

Results and discussion

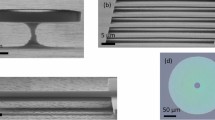

SiNx/SiOx etching

Fig 2 (a)-(c) show the etch rates and etch selectivity of SiNx over SiOx for each etch gas such as (a) 110 sccm CHF3, (b) 110 sccm C2H2F4, and (c) 80 sccm C2H2F4+ 30 sccm CF4O measured as a function of O2 flow rate. The process conditions were source power 1500 W, DC bias −100 V, process pressure 4 mTorr, and substrate temperature 18° C. CH3F (40 sccm) and He (100 sccm) were commonly supplied to the chamber. In the case of CHF3, as shown in Fig 2 (a), etch rates of both SiNx and SiOx decreased with increasing O2 flow rate possibly due to the decreasing etching species in the plasma but the SiNx etch rate decreased faster possibly due to the oxidation of SiNx surface, therefore, the etch selectivity of SiNx over SiOx decreased with increasing O2 flow rate and the highest etch selectivity of ~ 3 was observed at 30 sccm O2 flow rate. In the case of C2H2F4, as shown in Fig 2(b), the etch rates of both SiNx and SiOx increased with increasing O2 flow rate. Due to the faster increase of SiOx etch rate with O2 flow rate, the etch selectivity of SiNx over SiOx was decreased. The further increase of etch rates of SiNx and SiOx with increasing O2 flow rate appears to be related to the removal of a fluorocarbon polymer layer formed by carbon-rich C2H2F4 by increased O in the plasma. When 30 sccm CF4O was mixed with 80 sccm C2H2F4 as shown in Fig 2 (c), the etch rates of both SiNx and SiOx were higher than 110 sccm C2H2F4 at 30 sccm of O2 possibly due to lower fluorocarbon polymer on the surfaces of materials. And the further increase of O2 flow rate did not change the SiNx etch rate significantly while decreasing SiOx etch rate slightly, therefore, the etch selectivity of SiNx over SiOx was slightly increased with increasing O2 flow rate. (Additional optimization results are presented in the Supplementary Information Fig. S1. Although the highest etch rate was observed under one condition, this setting caused reduced SiNx/SiOx selectivity and profile degradation. Therefore, the condition that provided a better balance among etch rate, anisotropy, and selectivity was chosen as the optimized condition.) As a result, the SiNx etch rate and the etch selectivity of SiNx over SiOx were the highest as ~ 160 nm/min and ~ 4, respectively, at 30 sccm CF4O + 80 sccm C2H2F4. Therefore, it was found that, for the etching of SiNx selective to SiOx, CHF3-based gas can be replaceable by C2H2F4 and, especially, by C2H2F4+CF4O with higher SiNx etch rate with higher etch selectivity over SiOx. Also it should be noted that the etch rate and selectivity improvements observed in this study are not solely due to the use of low GWP gases (C2H2F4 and CF4O). The addition of O2, He, and CH3F also plays an essential role: O2 reduces excessive polymer formation, He stabilizes plasma and enhances etch uniformity, and CH3F contributes to controlled sidewall passivation. These gases, together with the low GWP etchants, collectively determine etch characteristics. To confirm repeatability, the etching experiments were repeated on three separate wafer batches, and the variation in SiNx/SiOx etch selectivity was within ±3%, indicating high process reliability.Fig 3 (a)~(c) show SEM cross-sectional images of SiOx masked SiNx etch profile after etching ~ 50 nm deep SiNx, which is generally required for SiNx etch depth in conventional double patterning process. Etch gases were (a) CHF3 (110 sccm), (b) C2H2F4 (110 sccm), and (c) C2H2F4(80 sccm)+CF4O (30 sccm) and the other process conditions were the same as those in Fig 2. As shown in Fig 3(a), for SiNx etching with CHF3-based gas, SiOx mask was consumed the most among three gases in (a)~(c) also, slight SiNx sidewall etching was observed. When C2H2F4 or C2H2F4+CF4O was used instead of CHF3, as shown in Fig 3(b) and (c), respectively, highly anisotropic SiNx etch profile with the smaller SiOx mask etching than CHF3 in (a) could be observed. However, in general, for the etching of ~50 nm deep SiOx masked SiNx etching, three etch gases were applicable for current double patterning process.

SEM images of 50nm depth partial SiNx etch with (a) CHF3 (110 sccm), (b) C2H2F4 (110 sccm), and (c) C2H2F4(80 sccm)+CF4O (30 sccm). SEM images for 200nm depth SiNx full etching with (d) CHF3, (e) C2H2F4, and (f) C2H2F4+CF4O. The other process conditions are the same as those in Fig 2.

Next generation double patterning process requires deeper SiNx etching, therefore, the etch time was increased to etch ~200 nm thick SiNx, and the results are shown in Fig 3 (d) CHF3, (e) C2H2F4, and (f) C2H2F4+CF4O13,16,28,33,34. For etching with CHF3-based gas, as shown in Fig 3(d), it was difficult to etch ~ 200 nm deep SiNx while shrinking CD size significantly and removing SiOx mask almost completely, due to the surface oxidation of SiNx at 90 sccm of O2 flow rate. (When the O2 flow rate was decreased to 30 sccm, as shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S2, full 200 nm deep SiNx could be etched with CHF3-based gas even though the CD size was decreased and SiOx mask was almost removed similar that at 30 sccm O2 flow rate.) In the case of C2H2F4 and C2H2F4+CF4O, as shown in Fig 3 (e) and (f), respectively, ~ 200 nm deep SiNx could be fully etched and almost vertical etch profiles were observed. However, in the case of C2H2F4-based gas, the CD size was slightly increased and trenching was observed at the etched SiNxpattern bottom edge possibly due to a polymer layer formed at the pattern bottom. This trenching behavior appears to be in good agreement with previous reports, which suggest that similar profile defects observed in fluorocarbon plasmas may result from localized polymer deposition17,35. However, for C2H2F4+CF4O-based gas, vertical SiNx etch profiles without CD variation and without trenching defects could be observed possibly due to the effective polymer layer removal on the pattern bottom area by addition of CF4O. As shown in Fig 3 (d-f), replacing CHF3 with C2H2F4 improved the SiNx/SiOx selectivity. Moreover, the addition of CF4O further enhanced the selectivity, which can be attributed to the increased availability of fluorine radicals required for SiNx etching and the simultaneous suppression of excessive polymer deposition by oxygen radicals. These improvements demonstrate that CF4O plays a critical role in achieving both anisotropic etching and higher selectivity. Additionally, the sidewall angle could not be measured for the CHF3-based process due to the incomplete etching of the SiNx layer. For the C2H2F4-based process, the measured sidewall angle was approximately ~84°, while for the C2H2F4+CF4O-based process, it was around ~88°, confirming highly anisotropic and vertical etch profiles. The etch uniformity across the wafer was maintained within ±5%.

Plasma analysis

Using the process conditions in Fig 3, the dissociated species in the plasma were observed using QMS and OES. Fig 4 (a) and (b) show positive ion species in the plasma and their relative intensities, respectively, measured by QMS. (Total measured ion intensities were measured and the results are shown in Supplementary Information Fig. S3 and the total ion intensities were the highest for CHF3-based gas and the lowest for C2H2F4-based gas possibly indicating the lowest plasma density for the C2H2F4-based gas.) Fig 4(a) shows an overview of the positive ion species detected in the plasma for each gas chemistry, as measured by QMS. As shown in Fig 4 (b), polymerizing ion species such as CH2F+, CHF2+, and C2H2F3+ were slightly more abundant in the CHF3-based plasma compared to C2H2F4 and C2H2F4+CF4O plasmas, which showed similar levels. In addition, the CHF3 plasma exhibited the highest O2+ ion intensity, whereas the lowest O2+ intensity was observed with the C2H2F4-based plasma, indicating a stronger oxidation potential in the CHF3 condition. The largest amount of O2+ in the plasma for CHF3-based gas is believed to be related to the oxidation of SiNx while the lowest O2+ amount in the plasma for C2H2F4-based gas is related to the trenching of the patterned SiNx edge due to the polymer formed on the pattern surface. Etch species such as HF+ and CF3+ were the highest for C2H2F4+CF4O and the lowest for CHF3+, and which is believed to be partially related to the highest SiNx etch rate for C2H2F4+CF4O and the lowest for the CHF3.Fig 4 (c) shows the OES wide scan data for CHF3, C2H2F4, and C2H2F4+CF4O-based gas in Fig 3 and (d)~(f) show OES narrow scan data related to (d) F (703.7 nm), (e) O (777.4 nm), and (f) H (656.5 nm)30,31,36,37,38. The peak intensities were normalized by He (501.6 nm) peak intensity. The intensity variation of O and H observed by OES were similar to the variation of those positive ion mass intensities (for O, CHF3>>C2H2F4+CF4O>C2H2F4 and for H, CHF3>C2H2F4>C2H2F4+CF4O) The highest O2⁺ ion intensity was observed in the CHF3-based plasma, which is associated with enhanced oxidation and suppression of polymer accumulation. In contrast, the lowest O2⁺ level in C2H2F4-based plasma results in reduced oxidation, promoting polymer formation and the occurrence of trenching. In addition, using OES, the variation of F peak intensity in the sequence of C2H2F4+CF4O>C2H2F4>CHF3 could be observed, and which is believed to be related to the SiNx etch rate together with variation of CF3+ and HF+ observed by QMS.

Surface analysis & etch mechanism

The atomic composition of the etched SiNx and SiOx surfaces and the binding states of Si under the process conditions in Fig 3 were measured by XPS, which are shown in Fig 5. All plasma and surface characterizations in this study were conducted on blanket wafers. As such, sidewall-specific effects in patterned features are not directly assessed. To minimize surface contamination, the etched samples were vacuum-packed to reduce exposure to air and then transferred to the XPS chamber. The measurements were carried out under high vacuum conditions (~10-9Torr). For the XPS analysis, the SiNx and SiOx were etched for 2 min. Fig 5 (a) and (b) show the atomic composition of the etched SiNx and SiOx surfaces, respectively. As shown in Fig 5(a), the SiNx surface has the most C percentage for C2H2F4-based gas, followed by C2H2F4+CF4O, and then CHF3, while O percentage has the most for CHF3, followed by C2H2F4+CF4O, and C2H2F4. Therefore, it is believed that the SiNx surface etched by CHF3-based gas was oxidized due to the highest O percentage while the SiNx surface etched by C2H2F4 was polymerized due to the highest C percentage. In addition, the higher percentages of Si and N in the order of CHF3, C2H2F4, and C2H2F4+CF4O appear to be related to the etch rate of SiNx. In contrast, the etched SiOx surfaces, as shown in Fig 2(a)–(c), exhibit similar etch rates regardless of gas chemistry, suggesting that the underlying etching mechanism remains consistent across the different plasma conditions. The surface characteristics were further investigated by observing XPS narrow scan data of Si 2p for the SiNx and SiOx etched with CHF3, C2H2F4, and C2H2F4+CF4O. The results are shown in Fig 5(c) CHF3, (d)C2H2F4, and (e)C2H2F4+CF4O for etched SiNx surface and (f) CHF3, (g)C2H2F4, and (h)C2H2F4+CF4O for etched SiOx surface. As shown in Fig 5 (c~e), the SiNx etched with CHF3 showed the highest Si-O bonding (~103.6 eV)39 while the SiNx etched with C2H2F4 and C2H2F4+CF4O showed the highest Si-N bonding (~101.8 eV)40 indicating the oxidation of SiNx surface by CHF3, which results in low SiNx etch rate. (Supplementary Information Fig. S4 shows XPS C1s narrow scan data for SiNx and SiOx etched with CHF3, C2H2F4, and C2H2F4+CF4O. Both SiNx and SiOx surfaces etched with C2H2F4 showed the highest C–F (~289.5 eV), C–CF (~287.5 eV), and C–CF2 (~291.8 eV) bondings related to a fluorocarbon polymer layer, and C2H2F4+CF4O exhibited slightly lower intensities, while CHF3 showed the lowest among the three gases. Therefore, SiNx etched with C2H2F4 exhibited the thickest polymer layer on the etched SiNx surface, and which might be related to the trenching of etched SiNx pattern edge.) In the case of SiOx surfaces, as shown Fig 5 (f~h), Si-O bonding (~103.6 eV) was the highest binding peaks for all the three gases, therefore, no significant differences in SiOx etch rate could be observed. (Supplementary Information Fig. S5 shows the atomic percentages of SiNx and SiOx surfaces measured by XPS after etching using CHF3 with 30 sccm of O2 flow rate, and XPS Si 2p and C1s narrow scan data on SiNx and SiOx surfaces etched using CHF3 with 30 sccm of O2 flow rate. The use of 30 sccm O2 flow rate for the etching of SiNx and SiOx with CHF3 decreased the O percentage and Si-O bonding peak on the etched SiNx surface similar to those for the SiNx etched using C2H2F4 and C2H2F4+CF4O with 90 sccm O2 flow rate while no significant change was observed for the etched SiOx surface similar to the surface etched with 90 sccm O2 flow rate.)Fig 6(a)~(c) shows the potential etch mechanism of SiOx masked SiNx pattern etching under the process conditions in Fig 3. Fig 6(a) shows the etch behavior of SiNx when using CHF3 gas. During the etching process with CHF3, surface oxidation occurs on SiNx surface, resulting in significant decrease of SiNx etching. Fig 6(b) shows the SiNx etching process using C2H2F4 gas. The low surface oxidation of SiNx maintains etching, enabling full etching with a thickness of ~ 200 nm. However, the formation of a polymer layer in the SiNx pattern due to C2H2F4 leads to problems such as tapered profile and trenching. Fig 6(c) shows the etching mechanism under the C2H2F4+CF4O. The addition of CF4O reduced polymer formation, resulting in higher etching rates and better selection ratios compared to C2H2F4 alone, eliminating trenching within the SiNx pattern. Consequently, the trenching and tapered profiles observed under C2H2F4-based plasma are primarily caused by excessive fluorocarbon polymer deposition, which disrupts uniform ion flux toward the pattern bottom. The incorporation of CF4O promotes the oxidation of carbon-based species, thereby reducing polymer thickness and improving etch anisotropy.

Atomic percentages of (a) SiNx and (b) SiOx surfaces measured by XPS after etching using the process conditions in Fig 3. XPS Si 2p narrow scan data on etched SiNx for (c) CHF3, (d) C2H2F4, and (e) C2H2F4+CF4O and XPS Si 2p narrow scan data on etched SiOx for (f) CHF3, (g) C2H2F4, and (h) C2H2F4+CF4O.

Schematic drawings of etch mechanism for SiOx masked SiNx etching with CHF3, C2H2F4, C2H2F4+CF4O-based gases. (a) for CHF3-based gas, due to the SiNx oxidation, the etching of SiNx is very slow. (b) for C2H2F4-based gas, due to the polymer formation, trenching is formed at the SiNx pattern bottom edge. (c) for C2H2F4+CF4O, the polymer layer in the pattern is effectively removed and highly anisotropic SiNx etching is obtained.

Measurement of million metric tons of carbon equivalents

Table 1 provides detailed information including the names of the gases used in the experiment, their molecular weights, GWP values and the Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) values. CHF3 exhibits a high global warming potential (GWP100yr) value of 14,600, C2H2F4 shows a GWP100yr value of 1,430, and CF4O represents a very low GWP100yrvalue close to ~141. However, since the gases used in etching have the potential to recombine and form by-products after decomposition during plasma discharge, it is essential to analyze the gas concentration in the exhaust line and calculate the Million Metric Tons of Carbon Equivalent (MMTCE), which corresponds to the total global warming index. Below is the equation for the MMTCE. The MMTCE was calculated using GWP100yr, which refers to the integrated global warming potential over a 100-year time horizon, while Mi represents the total mass emission of HFCs and PFCs measured by FT-IR during the process42

Fig 7(a) shows the concentration (in ppm) of exhaust gases measured in the exhaust line using FT-IR during plasma generation using CHF3, C2H2F4, and C2H2F4+CF4O-based gas under the process conditions in Fig 3, and which shows the various recombinants of decomposed etched gases. In the case of CHF3, recombinants such as HF (GWP = 0), COF2 (GWP = ~1), and CHF3 itself were detected along with the formation of C2F6(GWP = 12,400), a high GWP gas41,43. In the case of C2H2F4, more HF and COF2 with low GWP values were formed compared to CHF3, while the formation of CHF3 having a high GWP decreased. Although CF4(GWP = 7,380) was produced, it was found to be relatively small44,45. For C2H2F4+CF4O, the formation of C2F6 was also observed compared to C2H2F4, and the amount of COF2 increased. The concentrations of HF and CHF3 remained similar. However, the addition of CF4O led to an increase in CF4 formation during its dissociation and recombination. Fig 7(b) shows the MMTCE graph calculated when etching a ~50 nm high SiNx target. When C2H2F4-based gas was used instead of the conventional CHF3-based gas, ~83.9% reduction of MMTCE was observed. In the case of using C2H2F4+CF4O-based gas, CF4 was produced due to CF4O, resulting in a ~75.2% reduction compared to the conventional CHF3-based gas. However, the C2H2F4+CF4O -based etch process not only showed higher SiNx etch rates and etch selectivity of SiNx over SiOx but also emitted much lower greenhouse emissions compared to the conventional CHF3 process, confirming that it is an etching process that can replace the etching process using CHF3, which is suitable for next-generation applications and is environmentally friendly.

(a) Concentration of exhaust gases (ppm) measured using FT-IR in the exhaust line during plasma generation using CHF3, C2H2F4, C2H2F4+CF4O-based in Fig 3. (b) MMTCE values calculated for the gases used to etch the same SiNx thickness.

Conclusions

This study investigated etch properties using low global warming potential (GWP) gases as an alternative to CHF3, which has traditionally been used in SiNx etch processes selective to SiOx such as double patterning processes for FinFET, 3D NAND fabrication, etc. Such processes are directly relevant to advanced memory fabrication, where SiNx is commonly used as a spacer or dielectric layer. These structures require precise profile control, minimization of polymer-induced defects, and compatibility with high-aspect-ratio integration. Replacing CHF3 with C2H2F4 resulted in higher SiNx etch rates and higher etch selectivity over SiOx, but trenching phenomena were observed in the etched pattern edge. By replacing it with C2H2F4+CF4O, not only higher SiNx etch rate but also trenching could be eliminated.Plasma and surface analysis showed that, in the case of etch processing using CHF3, the SiNx etch rate was slow due to oxidation of the SiNx surface due to the large amount of oxygen in the plasma, while in the case of C2H2F4, the trenching phenomenon was observed by forming a polymer on the pattern surface. By adding CF4O to the C2H2F4, the polymer formed on the pattern surface could be successfully removed, and not only the SiNx etch rate was increased, but also the trenching phenomenon was eliminated. In addition, the calculation of MMTCE showed that, when C2H2F4 and C2H2F4+CF4O were used instead of conventional CHF3, the MMTCEs were significantly reduced by ~83.9% and ~75.2%, respectively. These improvements, combined with significantly reduced MMTCE values, suggest that C2H2F4+CF4O is a promising candidate for eco-friendly and high-precision SiNx etch processes applicable to advanced FinFET and 3D NAND device fabrication.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request to Yongil Kim (yikim11@skku.edu) and Geun Young Yeom. (gyyeom@skku.edu).

Change history

05 February 2026

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, the Supplementary Information file which was included with the initial submission, was omitted. The Supplementary Information file now accompanies the original Article.

References

Sun, Y. Destruction of Fluorinated Greenhouse Gases by Using Nonthermal Plasma Process, In: Planet Earth 2011 - Global Warming Challenges and Opportunities for Policy and Practice, InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/23405.

Ye, J. H. & Zhou, M.S. Carbon Rich Plasma-Induced Damage in Silicon Nitride Etch, 2000.

Rentsch, J. et al. Preu, Plasma Cluster Processing for Advanced Solar Cell Manufacturing, n.d.

Lugani, G. S. et al. Direct Emissions Reduction in Plasma Dry Etching Using Alternate Chemistries: Opportunities, Challenges and Need for Collaboration. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSM.2024.3444465 (2024).

Kim, T., Shin, D., Park, J., Pham, D. P. & Yi, J. Mobility improvement of LTPS thin film transistor using stacked capping layer. Microelectron Eng https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mee.2021.111591 (2021).

Guertin, J. P. & Onvszchuk, M. Coordination of silicon tetraBuoside with pyridisae and other nitrogen electron-pair donor molecnPesl. Can. J. Chem. 47(8), 1275–1279 (1969).

Mccurdy, B. J. Matrix Reactions of Silicon Difluoride as Studied by Infrared Spectroscopy, 1966.

Zhou, H., Song, Y., Xu, Q., Li, Y. & Yin, H. Fabrication of Bulk-Si FinFET using CMOS compatible process. Microelectron Eng 94, 26–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mee.2012.01.004 (2012).

Chatterjee, S. & Kim, H. Material engineering to enhance reliability in 3D NAND flash memory. Mater. Today Phys. 40, 100928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtphys.2024.100928 (2024).

Sevilla, G. A. T. et al. Flexible and transparent silicon-on-polymer based sub-20 nm non-planar 3D FinFET for brain-architecture inspired computation. Adv. Mater. 26, 2794–2799. https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.201305309 (2014).

IEEE Staff, IEEE/SEMI Advanced Semiconductor Manufacturing Conference, IEEE, 2009.

Barnola, S. et al. Integration of dry etching steps for double patterning and spacer patterning processes, In: Optical Microlithography XXII, SPIE,: 72741X. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.814856. (2009).

2018 IEEE International Interconnect Technology Conference (IITC) : 4-7 June 2018, [IEEE], 2018.

Hyun, K. D. Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Low-temperature atomic layer deposition of high-quality SiO2 and Si3N4 thin films, 2019.

Chang, B. Integrated in situ self-aligned double patterning process with fluorocarbon as spacer layer. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., B: Nanotechnol. Microelectron.: Mater., Process., Meas., Phenom. https://doi.org/10.1116/6.0000089 (2020).

Reyes-Betanzo, C., Moshkalyov, S. A., Swart, J. W. & Ramos, A. C. S. Silicon nitride etching in high- and low-density plasmas using SF6/O2/N2 mixtures. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., A: Vac., Surf. Films 21, 461–469. https://doi.org/10.1116/1.1547703 (2003).

Kuo, W. C. & Liu, C. M. A plasma processing combined with trench isolation technology for large opening of parylene based high-aspect-ratio microstructures. Microelectron Eng 133, 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mee.2014.11.012 (2015).

Lill, T. et al. Low-temperature etching of silicon oxide and silicon nitride with hydrogen fluoride. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., A https://doi.org/10.1116/6.0004019 (2024).

Hsiao, S. N., Britun, N., Nguyen, T. T. N., Sekine, M. & Hori, M. Etching Mechanism Based on Hydrogen Fluoride Interactions with Hydrogenated SiN Films Using HF/H2 and CF4/H2 Plasmas. ACS Appl Electron Mater 5, 6797–6804. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsaelm.3c01258 (2023).

Hsieh, S. I. et al. Reliability and memory characteristics of sequential laterally solidified low temperature polycrystalline silicon thin film transistors with an oxide-nitride-oxide stack gate dielectric, Japanese J. Applied Phys. Part 1: Regular Papers and Short Notes and Review Papers 45 3154–3158. https://doi.org/10.1143/JJAP.45.3154. (2006).

Huzaibi, H. U. et al. Charge transport mechanism in low temperature polycrystalline silicon (LTPS) thin-film transistors. AIP Adv https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5082994 (2019).

Kim, J., Kang, H., Kim, Y., Jeon, M. & Chae, H. Low global warming C5F10O isomers for plasma atomic layer etching and reactive ion etching of SiO2 and Si3N4. Plasma Processes Polym. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.202300216 (2024).

Chen, B. W. et al. Systematic Analysis of High-Current Effects in Flexible Polycrystalline-Silicon Transistors Fabricated on Polyimide. IEEE Trans Electron Devices 64, 3167–3173. https://doi.org/10.1109/TED.2017.2715500 (2017).

Gong, L. et al. Investigation of the etching mechanism of silicon nitride by CF4/O2/Ar gas mixture plasma in ICP. Vacuum 233, 114000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2024.114000 (2025).

Gil, H. S. et al. Selective isotropic etching of SiO2 over Si3N4 using NF3/H2 remote plasma and methanol vapor. Sci Rep https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38359-4 (2023).

Pankratiev, P. et al. Selective SiN/SiO2 etching by SF6/H2/Ar/He plasma, In: AIP Conf Proc, American Institute of Physics Inc., https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5135490. (2019).

Ohtake, H., Wanifuchi, T. & Sasaki, M. SiN etching characteristics of Ar/CH3F/O2 plasma and dependence on SiN film density. Jpn J Appl Phys https://doi.org/10.7567/JJAP.55.086502 (2016).

Gatzert, C., Blakers, A. W., Deenapanray, P. N. K., Macdonald, D. & Auret, F. D. Investigation of reactive ion etching of dielectrics and Si in CHF3∕O2 or CHF3∕Ar for photovoltaic applications. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., A: Vac., Surf. Films 24, 1857–1865. https://doi.org/10.1116/1.2333571 (2006).

Fracassi, R. F. D’agostino, Contribution to Global Warming of Plasma Polymerization and Treatment Processes Fed with Fluorinated Compounds*, (1999).

Woo Hong, J. et al. Reactive ion etching of indium gallium zinc oxide (IGZO) and chamber cleaning using low global warming potential gas. Appl Surf Sci https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2024.160692 (2024).

Hong, J. W. et al. Indium tin oxide etch characteristics using CxH2x+2(x=1,2,3)/Ar. Mater Sci Semicond Process https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2023.107395 (2023).

Kim, Y. et al. Low Global Warming C4H3F7O Isomers for Plasma Etching of SiO2 and Si3N4Films. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 10, 10537–10546. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c01705 (2022).

Kwan Lee, H. Soo Chung, H. & Su Yu, J. Selective Etching of Thick Si3N4 , SiO2 and Si by Using CF4/O2 and C2F6> Gases with or without O2 or Ar Addition, (2009).

Loong, S. Y. et al. Characterization of polymer formation during Si02 etching with different fluorocarbon gases (CHF3, CF4, C4F8), n.d. http://spiedl.org/terms.

Kim, S.-W. et al. Analytical study of polymer deposition distribution for two-dimensional trench sidewall in low-k fluorocarbon plasma etching process. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., B: Nanotechnol. Microelectron.: Mater., Process., Meas., Phenom. https://doi.org/10.1116/1.4996641 (2018).

Hong, J. W. et al. Effect of various pulse plasma techniques on TiO2 etching for metalens formation. Vacuum https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2023.111978 (2023).

Hong, J. W. et al. Etched characteristics of nanoscale TiO2 using C4F8-based and BCl3-based gases. Mater Sci Semicond Process https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2023.107617 (2023).

Il Cho, N. et al. Etch characteristics of maskless oxide/nitride/oxide/nitride (ONON) stacked structure using C4H2F6-based gas. Sci Rep https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74107-y (2024).

De Santis, P. Palleschi, A. Savino, M. Scipioni, A. & Moro, C. P. A. Per lo Studio degli, Poly(DL-prollne), a Synthetic Polypeptide Behaving as an Ion Channel across Membranes: In Conformational Studies on Ion Complexes of the Tetramer Boc(D-Pro-L-Pro)2OCH3. https://pubs.acs.org/sharingguidelines. (1988).

Lee, W.-J. Lee, J.-H. Park, C.O. Lee, Y.-S. & Shin, S.-J. A Comparative Study on the Si Precursors for the Atomic Layer Deposition of Silicon Nitride Thin Films, 2004.

AR6 WGI Report-List of corrigenda to be implemented, n.d. https://github.com/IPCC-WG1/Chapter-7.

Lee, H. S. et al. SiO2 etch characteristics and environmental impact of Ar/C3F6O chemistry. J. Vac. Sci. Technol., A: Vac., Surf. Films https://doi.org/10.1116/1.5027446 (2018).

Victor, D. G. & Macdonald, G. J. A Model For Estimating Future Emissions of Sulfur Hexafluoride and Perfluorocarbons. (1999).

Rabie, M. & Franck, C. Computational screening of new high voltage insulation gases with low global warming potential. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 22, 296–302. https://doi.org/10.1109/TDEI.2014.004474 (2015).

Harvey, R. Estimates of U.S. Emissions of High-Global Warming Potential Gases and the Costs of Reductions. http://www.epa.gov/ghginfo. (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program Development Program-Development of core technology in Carbon Neutrality (RS-2023-00265858, Development of alternative PFC gas with low GWP value under 150 for OLED display oxide TFT insulator patterning) funded By the Ministry of Trade, Industry & Energy(MOTIE, Korea).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.L.K and J.W.H contributed to the experimental design. Y.W.J contributed to the experimental setup. J.W.J, C.H.K, H.J.E and S.H.K contributed to the data analysis. J.S.P and N.I.C, J.H.K initiated the project. G.Y.Y and Y.G.K participated in writing the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, K.L., Hong, J.W., Jeon, Y.W. et al. Effect of C2H2F4/CF4O with low global warming potentials on SiNx etching as a CHF3 replacement. Sci Rep 15, 40517 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24378-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-24378-w