Abstract

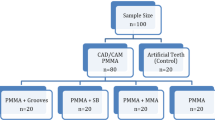

Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) is commonly used in medical devices for the oral cavity. It is precisely due to its biocompatibility, mechanical strength, wear resistance, and aesthetic qualities that it is so prolific. While widely used in dental and biomedical applications, PMMA has several limitations that necessitate improvement. Due to mechanical limitations, low impact resistance, susceptibility to cracking and wear, low thermal conductivity, and microbial adhesion, various modifications have been introduced. In this study, the PMMA surface was modified with a SiO2 coating obtained from a TEOS precursor under both acidic and alkaline conditions using the sol-gel method. Additionally, Graphene oxide (GO) and cannabidiol (CBD) were added to the coating, and the mechanical properties of the modified coatings were studied. This study aimed to investigate the effect of surface modification on the physicochemical properties of PMMA. The coatings were subjected to comprehensive physicochemical investigations, including TGA, FTIR, XPS, SEM, surface topography, surface wettability, Shore hardness, and tribological evaluations in artificial saliva. The study confirmed that the modification of PMMA with SiO2, GO and CBD has a beneficial effect on their structure, chemical properties, thermal stability, mechanical properties, and potentially the antibacterial of PMMA for used in biomedical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) is widely used in dental applications due to its biocompatibility, mechanical strength, wear resistance, and aesthetic qualities1,2,3. However, it has limitations, such as low thermal conductivity, susceptibility to water absorption and staining, which can affect patient comfort and aesthetics. Chemically, PMMA is stable in the oral environment but can release residual monomers with potential cytotoxic effects, including inflammation and oxidative stress4,5,6,7,8. As a result, recent studies have focused on surface functionalization through the application of various coatings. Materials intended for contact with the interior of the human body must meet a series of stringent regulatory and biocompatibility requirements, similar to the coatings proposed for these materials, which must also be tailored to specific functional and biological demands. When designing such a coating, it is essential to consider the following aspects: adhesion to the substrate, abrasion and corrosion resistance, absence of cytotoxic effects, and antibacterial properties9,10,11,12. Coating can be applied to the surface of biomaterials using various deposition methods, but the sol-gel method has many advantages that make it widely used in the synthesis of materials with advanced properties. First and foremost, it is a simple and efficient process that allows for the preparation of high-purity products13,14,15,16. Due to precise control over the chemical composition, it is possible to obtain uniform materials, including composite oxides. Additionally, it allows a high degree of flexibility in modifying the number of precursors, solvents, catalyst and processing temperature17,18,19,20,21.

Improving surface hydrophobicity has the potential to significantly reduce bacterial adhesion, thereby conferring antimicrobial properties. Ortiz et al.22 developed durable silica nanoparticles (SiNP) coating with hydrophilic properties using a sol-gel method. After silanization with dodecyltrichlorosilane, the coating gained superhydrophobic properties, reaching a water wetting angle of more than 150°, which significantly reduces the adhesion of bacteria and other microorganisms. Silica-based coatings, in addition to their anti-microbial properties, have shown the potential to improve biomaterial corrosion resistance and stimulate cell growth23,24,25. Recent studies have demonstrated that incorporating graphene oxide (GO) or TiO2 in the surface can improve mechanical properties, biological interactions, and even enhance sensing performance, which highlights the versatility of nanoparticle-enhanced coatings for biomedical applications9,26,27,28,29. Empirical evidence indicates that GO addition substantially enhances cellular interactions, thereby supporting their suitability for biomedical applications30. Research by Scarano et al.28 highlights that graphene-doped PMMA implants improve cell adhesion and proliferation without compromising mechanical properties. Additionally, in their review, Podila et al.31 emphasizes the biocompatibility and chemical inertness of graphene coatings, which contribute to improved surface characteristics and reduced bacterial adhesion. As another candidate material, cannabidiol (CBD) shows analgesic properties, allowing its incorporation into coatings on biomaterials aimed at relieving pain. It has the potential to provide a local, long-lasting release of this compound, leading to pain relief32,33,34.

Although silica-based coatings and GO modifications have been widely investigated for biomedical applications, previous studies have typically employed either GO or CBD individually to improve a single functionality, such as hydrophilicity or bioactive properties. However, their combined integration within a single coating remains largely unexplored. To address this gap, the present study introduces a novel hybrid coating system in which both GO and CBD are separately and simultaneously incorporated into the sol-gel-derived silica matrix on PMMA substrates. Sol-gel-based processes are proposed and systematically evaluated to develop multifunctional silica-based bio-coatings with improved mechanical properties. The main idea is that silica matrix provides excellent adhesion to the substrate, high chemical, and mechanical stability, as well as antibacterial properties, which are crucial for biomedical applications. The addition of GO can improve mechanical properties, while CBD adds analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects to the coating. In that purpose, SiO2, SiO2/GO, and SiO2/CBD, and SiO2/CBD/GO composite coatings were deposited on PMMA surface using sol-gel method. The chemical properties of the modified PMMA were studied using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), while the mechanical properties were evaluated in terms of topography, surface wettability, friction/wear (in artificial saliva), and Shore hardness.

Materials and methods

PMMA substrate preparation

Self-curing acrylic resin (Villacryl SP, Zhermack, Zhermapol) was used as the substrate in this work. The chemical composition of the acrylic resin consisted of a powder component: polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), benzoyl peroxide, and pigments; and a liquid: methyl methacrylate, ethylene glycol dimethacrylare, N,N-dimethyl-p-toluidine. Samples with a diameter of 28 mm and a thickness of 11 mm were made from acrylic resin in a ratio of 10 g powder to 7 mL liquid. The samples were polymerized in water at T = 55 °C under p = 2 bar pressure for t = 30 min using a pressure polymerizer. After polymerization, the samples were ultrasonically cleaned in deionized water and alcohol for 10 min each and dried by air.

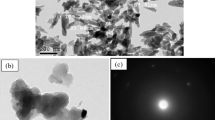

Graphene oxide particles preparation

GO was prepared using the modified Hummers’ method. One gram of graphite powder is added to a solution consisting of 180 mL concentrated H2SO4 and 20 mL H3PO4 and stirred. Then, 7 g of potassium permanganate (KMnO4) is gradually added, and the mixture is stirred for two hours (in an ice bath). The graphite exfoliation process is continued by stirring the dispersion for 24 h at T = 50–90 °C. After 24 h, 7 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is added to the dispersion. Then, the sample is repeatedly centrifuged and neutralized by adding demineralized water until the solution reached the pH 5. GO dispersion is kept in concentrated gel-like stage.

CBD solution preparation

(1’R,2’R)-5’-Methyl-4-pentyl-2’-(prop-1-en-2-yl)-1’,2’,3’,4’-tetrahydro-[1,1’-biphenyl]-2,6-diol (Cannabidiol, THC Pharm) was used to prepare the CBD solution. 40 mg of CBD was added to 1 mL of ethanol and fractionated with ultrasonication for 15 min. Then, 1 mL of oil phase (castor oil, Biomas) was added, followed by 1 mL of polyethylene sorbitol ester surfactant (Tween80, Acros Organics) and successively smashed with ultrasound for 15 min.

Preparation of sol-gel, sol-gel/GO, sol-gel/CBD, and sol-gel/CBD/GO solutions

In this study, two types of acidic- and alkaline-sol solutions were prepared. The acidic sol solution (SG3) was obtained by mixing 20 mL tetraethoxysilane (TEOS), 80 mL ethanol, and 20 mL deionized water. Then, the pH of the mixture was adjusted to pH = 3 by a few drops of acetic acid (CH3COOH). The mixture was then stirred for 24 h and held for 92 h at 24 °C for complete hydrolysis. The jelly point was found at 60 °C. On the other hand, the alkaline sol solution (SG9.5) was obtained by mixing 20mL TEOS and 80 mL ethanol. Then, the pH of the mixture was adjusted to pH = 9.5 with NH3 by a few drops. The mixture was then stirred for 30 min at 50 °C for a complete hydrolysis process. Sol solutions, with pHs of 3 and 9.5, were also synthesized as a control sample.

The second set of samples was made by modifying the acidic and alkaline sol solutions with GO. 1 g graphene oxide dispersion was added to 10 mL deionized water and sonicated for 2 h. The resulting suspension was added to the sol solutions (SG3 and SG9.5), to yield the sol-gel/GO composite with a ratio of 3:1. The mixture was then stirred with an electromagnetic stirrer for 15 min, 250 rpm. The sol-gel/GO solution was made for both acidic and alkaline sol.

The third set of samples in this study is the mixture of sol-gel and CBD solution. A CBD solution of V = 3 mL was added to a sol-gel solution of V = 27 mL and stirred on an electromagnetic stirrer for 15 min. The obtained sol solution yields the sol-gel/CBD composite with a concentration of 1 mg/mL. The sol-gel/CBD solution was also made for acidic and alkaline sols.

The last set was a sol-gel/CBD/GO solution. The CBD solution was added to the sol-gel/GO composite to obtain a concentration of 1 mg/mL CBD concentration. The solution was stirred using an electromagnetic stirrer for 30 min, 250 rpm.

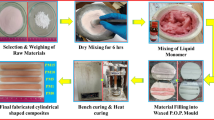

Preparation of SiO2, SiO2/GO, SiO2/CBD, and SiO2/CBD/GO coatings

The overall synthesis and coating preparation procedure are shown schematically in Fig. 1. The dip-coating method was used to prepare the coatings on the PMMA substrates. The coating series of sol-gel (SiO2), sol-gel/GO, sol-gel/CBD, and sol-gel/CBD/GO were prepared with two sol-gel solution variants of: acidic (pH 3) and alkaline (pH 9.5). For both pH variants, the same dip-coating parameters were used. The pre-treated samples were immersed in the sol solution for 5 min, then taken out at 0.006 mm/s. The coated samples were heat-treated at 60 °C for 30 min, then at 100 °C for 30 min, and then at 120 °C for 30 min in an oven. The obtained sol-gel coatings were designated with abbreviations which are given in Table 1.

Thermogravimetric and chemical characterizations

The thermal stability of CBD was first evaluated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). A 5 mg sample was placed in a cuvet and analyzed with a TG 209 F1 Netzsch Thermogravimetric Analyzer under a constant nitrogen atmosphere. The temperature was increased at a rate of 10 °C per minute, starting at 30 °C and continuing up to 600 °C.

The infrared (IR) spectra of coatings were collected using the single reflection (attenuated total reflection) ATR technique with a diamond crystal on FT-IR spectrometer Tensor 27, Bruker. The measurement parameters were the following: spectral region 4000–400 cm-1, spectral resolution 4 cm-1, 64 scans. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was done using a PHI Quantera X-ray photoelectron spectrometer. The samples were irradiated with monochromated Al Kα X-rays at a spot size of 200 μm under ultra-high vacuum conditions. Ejected electrons were collected at a 45-degree emission angle and analyzed using a hemispherical capacitor analyzer operating in fixed-analyzer-transmission mode. All measurements were conducted with an active low-voltage ion gun and an electron neutralizer. Calibration of the spectrometer was performed under ISO 15472:2010 standards to ensure a minimum accuracy of 0.2 eV. Survey spectra were acquired with a pass energy of 280 eV and a step size of 1 eV, while high-resolution spectra were recorded with a pass energy of 55 eV and a step size of 0.05 eV. Data analysis was conducted using CasaXPS v. 2.3.22. Background subtraction was done with Shirley method, and peak fitting was executed with a Gaussian-Lorentzian line shape (GL(30)). Charge correction was done by setting the C–C/C–H component to 285.0 eV.

Surface characterizations

The surface morphology of the samples was examined using a ZEISS GeminiSEM 460 scanning electron microscopy (SEM) operating at 1 KeV in secondary electron mode. Samples were analyzed without any sputter-coating. 3D topography profiles of all samples were measured by a Dektak XT Stylus Profilometer with a stylus diameter of 2 μm (Bruker, Germany). 2D surface profiles with a length of 524 μm were measured on all samples. Mean roughness Sa, RMS roughness Sq, skew Ssk, and maximum height Sz were used as the characterization parameters. Surface wettability was evaluated by the sessile drop method using an Attention Theta Flex optical tensiometer (Biolin Scientific) with OneAttention software. A 2 mm3 drop of distilled water (H2O) as polar component and diiodomethane (I2CH2) as non-polar component was used for the test. The measurement lasted 60 s, with a sampling frequency of 1 Hz. The contact angle (Θ) was determined by the Young-Laplace equation, and the surface free energy (SFE) by Owens-Wendt method. Five measurements were made on each sample.

Biomechanical testing

Sliding friction studies were conducted using a universal tribometer (CSM Instruments SA) in a ball-on-disc configuration. Samples were rotating (at 1 mm/s) under a clean alumina (Al2O3) ball with a diameter of 6 mm at 2 and 5 N loads. The specimens were immersed in the artificial saliva (Table 2) in accordance with ISO 10993-15 standard at a constant temperature of 24 °C for the entire duration of the test. Wear marks were examined with SEM (ZEISS, GeminiSEM 460), and analyzed with a Dektak Stylus Profilometer. The final coefficient of friction (CoF) of each test was decided by the mean of five tests.

Shore hardness was measured using a Shore D Durometer. The test specimen was positioned on a flat surface, and the indenter was applied without impact. Hardness values were recorded after 10 s. Measurements were taken at multiple locations on the specimen, including both the center and the edges.

Results

Thermogravimetric analyses

The thermogravimetric analysis was used to determine thermal decomposition and show the presence of CBD in the composites. Figure 2 shows the thermograms of only (a) CBD, (b) GO, along with (c) SG3, (d) SG9.5, and composites of (e) SG3/CBD/GO and (f) SG9.5/CBD/GO. As can be seen, the complete thermal decomposition of only CBD occurs at 271 °C, while the partial decomposition temperature of GO was 524.9 °C, SG3 at about 420 °C, and SG9.5 at 410 °C. The composite samples’ thermograms show peaks at 244.7 °C and 427.4 °C for the SG3/CBD/GO sample and 270 °C and 408.4 °C for the SG9.5/CBD/GO sample. The thermograms at Fig. 2b–d show peaks at temperatures below 100 °C, indicating the evaporation of solvents present in the samples during their thermal decomposition. The peaks at 244.7 °C (Fig. 2e) and 270.9 °C (Fig. 2f) indicate the decomposition of CBD present in the composites in the amounts of probably 8.31 wt% and 3.61 wt%, respectively. The sharp peaks at 427.4 °C and 408.4 °C indicate the thermal decomposition of the sols.

Chemical analyses

The FTIR spectra of PMMA substrate and the coated samples are shown in Figs. S1 and 3, respectively. The results confirm the deposition of the coatings on the PMMA substrate. For the pure PMMA substrate, the intense signals corresponding to the methacrylate groups are visible (Fig. S1). A characteristic band for the C = O carbonyl groups of 1721 cm-1 is present. The 2950 cm-1 and 2850 cm-1 peaks indicate the asymmetric and symmetric stretching of CH2 groups, and the peak at 1437 cm-1 corresponds to asymmetric bending vibration (CH3) of methyl groups of PMMA (Fig. S1).

For the CBD IR-spectrum shown in Fig. 3, a broad band of 3406 cm-1 was recorded indicating O-H (aromatic) stretching vibrations characteristic of hydroxyls in CBD molecules, while the bands around 2900 cm-1 were assigned to C-H stretching (phenyl). The 2192 cm-1 was indicative of methyl and methylene groups, 1575 cm-1 was indicative of C = C stretching (phenyl ring), and C-O stretching vibrations were at 1212 cm-134.

FTIR spectrum of GO sample (Fig. 3) presents the following characteristic absorption peaks at 3197 cm-1 (OH), 2942 cm-1 (CH2), 1720 cm-1 (C = O), 1618 cm-1 (C = C), and characteristics for epoxide group 1221 cm-1 (COO) and 1041 cm-1 (C-O-C) 35.

In FTIR spectra of SG3 and SG9.5 coatings (Fig. 3), bands corresponding to Si-O-Si and Si-OH were observed, for both pH = 3 and pH = 9.5. These peaks were identified at 1048 cm-1 (Si-O-Si), 937 cm-1 (Si-OH), and 435 cm-1 (Si-O-Si)36.

The spectra of all CBD-containing samples show peaks characteristic of the CBD structure and at 1459 –1439 cm-1, indicating the presence of O-H deformation vibrations (Fig. 3).

For a GO coating modified with APTES (pH = 3 and pH = 9.5), the new characteristic absorption peaks appear at: 1181 cm-1 (Si-O-Si), 1048 cm-1 (Si-O-C), 940 cm-1 (Si-OH), 792 cm-1 (Si-O-C), 431 cm-1 (Si-O-Si)35.

The silica coatings SG3 and SG9.5, when combined with CBD and GO, exhibit notable chemical interactions that can be identified through the FTIR spectra. Specifically, the band at 1358 cm-1 suggests interactions between the hydroxyl groups of CBD and the epoxy groups of GO. Additionally, the broadening of the band at 3197 cm-1, corresponding to hydroxyl stretching vibrations, further indicates strong interactions between CBD and GO. These spectral features provide evidence of chemical bonding or intermolecular interactions between the components in the coatings, confirming the successful fabrication of the intended coatings.

The surface chemical composition of the pure PMMA substrate was analyzed using XPS (figure S2). The survey spectrum in figure S2 (a) show core-level and Auger peaks corresponding exclusively to carbon and oxygen. The high-resolution C 1s spectrum was fitted with four components representing four different carbon environments within PMMA (figure S2 (b)). Figure S2 (b) also shows the carbon classification of C1, C2, C3, and C4. The component corresponding to C-C/C-H or C1 is located at 285.0 eV (area of 45.4%). The C2 component is positioned at 285.8 eV (18.9%), C3 at 286.9 eV (19.4%), and C4 component at 289.0 eV (16.3%). The O 1s spectrum was fitted with two components: O = C bonds or O1 at 532.2 eV (48.4%) and O-C bonds or O2 at 533.7 eV (51.6%), as shown in figure S2 (c).

The XPS survey spectra of the coated samples under acidic conditions, namely SG3, SG3/GO, and SG3/CBD/GO, are shown in Fig. 4. The survey spectra display C 1s, O 1s, and Si 2s and Si 2p peaks (Fig. 4a). In the high-resolution C 1s spectra (Fig. 4b), four components were used to fit the spectra, representing C-C/C-H, C-C = O, C-O, and O–C = O groups. However, in SG3/GO and SG3/CBD/GO, an additional component appeared at approximately 0.5 eV lower binding energy than the C-C/C-H component, which was attributed to sp²-hybridized carbon atoms found in aromatic rings or graphene-like structures37. In SG3/GO, this component accounted for 4% of the total C 1s peak area, which is shown in the form of dashed line. In SG3/CBD/GO, the area of this component increased to 10% which is attributed to the presence of CBD and GO. The appearance of this component and its area increase confirm the incorporation of GO and CBD/GO intro the composite coatings.

The O 1s spectra (Fig. 4c) were fitted with two components: O = C at 532.3 eV and a higher binding energy component representing C-O-H/C, Si-O-Si, and Si-O-C groups. In SG3 coating, the higher binding energy component was at 533.5 eV with an area of 44%. In SG3/GO composite coating, the higher binding energy component shifted to 533.2 eV and its area increased to 49.2%. According to Fu et al., this shift can be attributed to an increase in Si-O-Si and Si-O-C bonds, which shifts the position of this component to lower binding energies24. Therefore, the increase of Si-O-Si and Si-O-C bonds is possibly due to increased interactions between Si-O groups and GO particles, which also confirms the incorporation of GO into SiO2 coating. In SG3/CBD/GO composite coating, the high-binding energy component further shifted to 533.1 eV and its area significantly increased to 70%. This could be due to more Si-O-C formation and much higher interaction of carbon atoms with SiO2 coating; this also can confirm from incorporation of CBD and GO into the composite layer of SG3/CBD/GO.

The Si 2p spectra (Fig. 4d) were fitted with two components: Si-O bonds at 103.4-103.5 eV and Si-O-C bonds at 101.9–102.0 eV25. In SG3 coating, the Si-O-C component represented 12.8% of the total Si 2p signal. In SG3/GO composite coating, this component’s area increased to 15.2%, and in SG3/CBD/GO composite coating, it further increased to 23.5%, indicating that the addition of GO and CBD enhances the formation of Si-O-C bonds.

The XPS analyses of samples prepared under alkaline conditions, namely SG9.5, SG9.5/GO, and SG9.5/CBD/GO, are presented in Fig. 5. The survey spectra (Fig. 5a) showed peaks corresponding to C 1s, O 1s, and Si 2s and Si 2p, confirming the presence of these elements on the surface. The high-resolution C 1s spectra (Fig. 5b) were fitted with the same four components shown in Fig. 4. In SG9.5/GO and SG9.5/CBD/GO composite coatings, the additional sp2 carbon component also appeared at approximately 0.5 eV lower binding energies than C-C component. This indicates the presence of GO and CBD/GO in the mentioned composite coatings.

Similar to Fig. 4, the O 1s spectra of alkaline coatings (Fig. 5c) were also fitted with two components: O = C bonds at 532.2-532.3 eV and a higher binding energy component representing O-C/H and Si-O-Si/C bonds. This component was located at 533.4 eV for SG9.5, slightly shifted to 533.3 eV for SG9.5/GO, and then to 533.2 eV for SG9.5/CBD/GO. As mentioned for the acidic coatings, the shift of this component to lower binding energies shows an increase in the amount of Si-O-Si and Si-O-C bonds. This happened with the addition of GO and CBD/GO, suggesting their incorporation into the coating. Nevertheless, this result shows the presence of CBD and GO within the alkaline coating in lower amount compared to the acidic composite coating. This is consistent with the TGA analysis.

The Si 2p spectrum (Fig. 5d) of SG9.5 was fitted with a single component corresponding to Si-O bond at 103.5 eV, indicating the predominance of Si–OH and Si–O–Si structures on surface. For SG9.5/GO and SG9.5/CBD/GO composite coatings, an additional Si-O-C component appeared at 101.9 eV, which also confirms the successful incorporation of GO and CBD into the composite coating on the PMMA surface at alkaline conditions.

The binding energies and peak area of all components are listed in Table S1.

Surface characteristics

Surface morphology

Figure S3 shows a smooth surface morphology for pure PMMA substrate before the coating process. The morphology of SG3 coating (Fig. 6a) indicates a relatively homogenized layer with distinct agglomerates. In contrast, at higher pH 9, the structure becomes heterogeneous, with more distinct irregularities (Fig. 6b). The presence of GO influences the formation of irregular structures on the surface. In the SG3/GO coating (Fig. 6c), the layer is clearly more uniformly patterned in relation to the SG9.5/GO coating (Fig. 6d), where larger agglomerates and greater structural variability are observed on the surface. The addition of CBD affects the morphology and possibly modifies the surface roughness. For SG3/CBD coatings (Fig. 6e), the surface appears to have more unregulated smaller features than the higher pH coating (SG9.5/CBD) in Fig. 6f). The composite CBD/GO coating obtained at pH 3 (Fig. 6g) initially appears more homogeneous compared to the surface at pH 9.5 (Fig. 6h), the presence of bright, elongated bands in Fig. 6g indicates local inhomogeneities within the coating.

Surface roughness

The 3D surface topography maps of samples are shown in Fig. 7 and the respective quantitative roughness parameters are summarized in Fig. 8.

The surface of PMMA before coating exhibits low surface roughness values, with Sa = 0.15 ± 0.04 μm and Sq = 0.19 ± 0.02 μm. However, the high skewness (Ssk = 1.11 ± 0.03 μm) indicates a pronounced imbalance between peaks and valleys. The deposition of an acidic silicon-based coating (SG3) significantly increased the Sa and Sq values to Sa = 1.27 ± 0.13 μm and Sq= 1.61 ± 0.11 μm, respectively, suggesting a higher surface roughness. Conversely, the SG9.5 coating also increased roughness compared to PMMA, with Sa = 0.51 ± 0.02 μm and Sq = 0.68 ± 0.02 μm, though the increase was less significant. The addition of GO to SG3 further increased roughness, resulting in Sa = 2.36 ± 0.21 μm and Sq = 2.84 ± 0.19 μm, highlighting the introduction of surface irregularities. In contrast, incorporating GO into SG9.5 did not alter surface roughness compared to SG9.5 coating, with values of Sa = 0.50 ± 0.03 μm and Sq = 0.64 ± 0.02 μm. The addition of CBD to SG3 did not cause significant changes, as Sa = 1.31 ± 0.10 μm and Sq = 1.66 ± 0.08 μm were close to the values observed for the SG3 coatings. However, the addition of CBD to SG9.5 increased roughness, with Sa = 0.70 ± 0.02 μm and Sq = 0.94 ± 0.02 μm. The composite SG3/CBD/GO coating on PMMA exhibited Sa = 1.18 ± 0.76 μm and Sq = 1.51 ± 0.82 μm, demonstrating the lowest roughness among acidic coatings (SG3, SG3/CBD, and SG3/GO). For SG9.5/CBD/GO composite coating, the roughness values were similar to SG9.5/CBD and were the highest among the alkaline coatings with values of Sa = 0.69 ± 0.02 μm and Sq = 0.99 ± 0.01 μm, but the skewness (Ssk = -0.04 ± 0.01) indicated a more uniform surface profile.

Surface wettability

The average contact angle and surface energy of all samples are reported in Table 3. The PMMA is characterized by a surface with a contact angle of θH2O = 76.4 ± 1.7°, θI2CH2 = 45.1 ± 3.9° and SFE = 42.3 mN/m. The imposition of an acidic silicon-based coating (SG3) had a slight effect on lowering the contact angle with water and diiodomethane to θ = 73.5 ± 0.8° and 41.2 ± 2.5°, respectively, while increasing the surface free energy to 45 mN/m. The SG9.5 coating also causes a decrease in the value of the contact angle, θH2O = 51.3 ± 2.1°, θI2CH2 = 41.9 ± 1.6°, and an increase in SFE = 56.4 mN/m. Further decreasing the water contact angle values were affected by the addition of GO and CBD to the SG3 coating (θH2O = 68.9 ± 2.4°, θI2CH2 = 50.2 ± 2.0° and θH2O = 0, θI2CH2 = 34.9 ± 1.7°, respectively). Also, the addition of CBD significantly increased the surface free energy value to 76.6 mN/m. In contrast, the addition of CBD to the SG9.5 coating did not significantly affect the surface wettability compared to SG9.5 coating. Additionally, the SG9.5/GO coating showed an increase in the contact angle and a decrease in the surface free energy with respect to SG9.5. It was observed that the addition of CBD/GO to the SG9.5 coating increased the contact angle values and decreased the SFE values with respect to SG3 and SG9.5. In addition, the SG3/CBD/GO composite coating was the only one among all the analyzed variants that had a hydrophobic character.

Biomechanical properties of samples

Friction evaluations

The coefficient of friction (CoF) of the coatings based on SG3 and SG9.5 is presented in Table 4. Typical variations in the coefficient of friction as a function of a sliding distance, as shown in Fig. 9.

Pure PMMA substrate display fluctuations and instabilities in CoF curves (Fig. 9a and b). These fluctuations and instabilities are more pronounced under the higher load of 5 N in artificial saliva. The SG3 and SG9.5 coatings have demonstrated lower CoF (Table 4) values as well as a steady behavior compared to the PMMA substrate. The curves start with a running-in behavior, due to the high roughness with the deposition of silica coatings. However, the SG3 coating exhibits slightly lower CoF compared to the SG9.5 coating. The addition of GO and CBD into the coating has positive effects, showing slight stabilization and reduction of CoF. All CBD containing coatings show minimum fluctuations of CoF values. Incorporation of both additives (CBD/GO) synergically provide the combination of low CoF values with proper stability at both acidic and alkaline conditions. Overall, coatings made in acidic conditions show slightly lower CoF values compared to alkaline coatings.

Wear of the coatings

SEM observations after tests show that there are distinct differences in morphology of worn surface both between different conditions and between different loads, as shown in Fig. 10. Profiles after tribological tests are shown in the Fig. 11. SEM observations reveal notable differences in the morphology of the worn surfaces between various materials and loading conditions. The Surface of worn SG3 coating shows slightly shallower wear tracks compared to the SG9.5 coating (Fig. 11a). According to SEM images of the wear tracks in Fig. 11 for SG3, SG3/GO, SG9.5, and SG9.5/GO coatings, signs of possible abrasive wear can be seen. According to the wear track images and profiles in Figs. 10 and 11, the SG3/CBD/GO composite coating shows more delamination, while SG9.5/CBD/GO composite coating demonstrates shallower wear tracks with visible cracking.

Shore hardness

Figure 12 presents the Shore D hardness results for all samples. All modification resulted in the improvement of PMMA’s surface hardness. The application of a SiO2 coating at pH = 3 led to a greater increase in hardness compared to pH = 9. The addition of GO and CBD does not always yield benefits, while it reduces the hardness in the case of SG3, it enhances hardness when combined with SG9.5. The highest hardness values were achieved for coatings containing CBD, specifically SG9.5/CBD and SG9.5/CBD/GO, both reaching Shore D hardness values of 86.

Discussion

Surface characterization using FTIR and XPS confirmed the effective deposition of coatings on the PMMA substrate and the presence of components such as CBD, GO, and SiO2. In the FTIR spectra of pristine PMMA, characteristic bands of methacrylate groups were observed, including a strong C = O signal at 1721 cm-1 and peaks corresponding to CH2 and CH3 groups. The FTIR spectrum of CBD showed a broad O-H band at 3406 cm-1, as well as signals for C-H, C = C, and C-O groups. GO exhibited typical absorption peaks for O-H, CH2, C = O, C = C, and epoxy groups. In the SG3 and SG9.5 coatings, bands corresponding to Si-O-Si and Si-OH groups were identified. The presence of CBD was confirmed by characteristic peaks of its molecular structure in all CBD-containing samples. Furthermore, the FTIR spectra of SG3 and SG9.5 coatings with both CBD and GO revealed strong chemical interactions, including a band at 1358 cm-1 (indicating interactions between hydroxyl groups of CBD and epoxy groups of GO) and broadening of the band at 3197 cm-1 (associated with O-H stretching vibrations), confirming the successful formation of functional composite coatings. XPS analysis revealed an additional sp2-hybridized carbon component in the GO-containing coatings, confirming the effective incorporation of GO and CBD/GO into the composite structure. These results were consistent with TGA analysis, further confirming the presence of GO and CBD in the composite coatings. Additionally, the results indicated that the amount of CBD and GO in alkaline coatings was lower compared to acidic ones.

Surface morphology analysis showed that all coatings were deposited on a smooth PMMA surface. The SG3 coating exhibited a more homogeneous layer with fewer agglomerates compared to the SG9.5 coating. The presence of GO influenced the formation of irregular structures. SG3/GO coatings appeared more uniform than SG9.5/GO, which showed larger agglomerates. The addition of CBD modified the morphology, as the SG3/CBD coating had irregular but smaller surface features compared to SG9.5/CBD. Coating deposition increased the roughness of the initially smooth PMMA surface. Among the silica-based coatings, those deposited under acidic conditions consistently produced higher surface roughness than their alkaline counterparts. Incorporating GO into the silica matrix notably increased roughness in the acidic system. However, in the alkaline coatings, GO had little impact on surface roughness, possibly due to lower amount of GO incorporation under alkaline conditions. The addition of CBD also had minimal impact on surface roughness. Hybrid coatings combining GO and CBD showed a unique behavior, where in the acidic system, the surface roughness was reduced and in the alkaline conditions, a more uniform roughness profile was achieved. These observations demonstrate that both high and low surface roughness levels can be achieved on PMMA simply by adjusting the coating composition and deposition conditions. These findings correlate with existing research emphasizing that surface roughness is a critical factor influencing microbial adhesion. Increased roughness provides microtopographical features that enhance cell retention by increasing the contact area and potentially shielding adhered microorganisms from shear forces. Rough surfaces offer niches that facilitate microbial attachment and biofilm formation, which are less accessible on smoother substrates. This has been observed in materials such as silicone prostheses, where higher roughness notably enhances Candida retention. The incorporation of GO into the coating reduced hydrophobicity, promoting a hydrophilic surface. CBD increased hydrophilicity in SG3- and SG9.5-based coatings, but SG3/GO/CBD exhibited hydrophobic behavior. Surface hydrophobicity is often considered a critical factor determining the adhesion of microorganisms, including Candida species, to various substrates. Hydrophobic surfaces tend to promote stronger interactions with hydrophobic microbial cells due to reduced interfacial free energy and increased London forces in the presence of water38,39.

Tribological improvements were observed under simulated oral conditions using artificial saliva. Compared to uncoated PMMA, which exhibited unstable and load-sensitive friction behavior, both SG3 and SG9.5 coatings showed lower and more stable CoF values. This stabilization can be attributed to the formation of a hard, protective silica layer that smoothens the tribological interaction. The introduction of GO into both systems led to a modest reduction in CoF. However, the most pronounced improvement in frictional stability was observed in coatings containing CBD. Across both pH conditions, CBD-containing coatings consistently exhibited the lowest CoF fluctuations, suggesting its lubricating role within the silica matrix. Composite coatings incorporating both GO and CBD revealed a synergistic effect, combining low CoF values with reduced fluctuations under both loading conditions. The SG3/CBD/GO composite displayed the lowest mean CoF values. All coatings showed an abrasive wear mechanism, with SG3/GO and SG3/CBD/GO showing slight delamination marks. The SG9.5/CBD/GO coating exhibited relatively shallower wear tracks. Hardness results showed that all coatings increased surface hardness, with acidic coatings generally showing greater hardness than alkaline ones. Notably, SG9.5/CBD/GO achieved one of the highest hardness values (Shore D hardness of 86).

The conducted research successfully fulfills the primary objective of assessing the impact of surface modifications on the physicochemical and mechanical properties of PMMA substrates. The applied SiO2-based coatings effectively enhanced PMMA characteristics, with the incorporation of functional additives such as CBD and GO further improving overall coating performance. Specifically, CBD improved coating stability and may provide additional biomedical benefits, including bioactivity, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic properties. GO, when combined with CBD, substantially improved mechanical properties and frictional behavior. The SiO2 matrix acted as a chemically stable foundation, contributing high resistance to environmental degradation and excellent mechanical properties. Among all tested formulations, the SG9.5/CBD/GO coating exhibited the most balanced performance, demonstrating high hardness, low CoF with high stability, and minimal wear. Future research should focus on evaluating long-term in vivo performance and understanding the biological interactions of GO and CBD to further optimize their clinical potential.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that SiO2-based composite coatings incorporating CBD and GO effectively enhanced the surface properties of PMMA. FTIR, XPS, and TGA confirmed the successful deposition and chemical integration of the functional components, which also hold potential biomedical benefits such as anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activity. Morphological analysis showed that both the coating composition and pH conditions significantly influenced surface roughness and uniformity. Notably, coatings deposited under acidic conditions exhibited higher surface roughness than those prepared under alkaline conditions.

The incorporation of CBD and GO also affected surface wettability, and both hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces could be obtained by adjusting the coating deposition conditions. Tribological tests conducted in artificial saliva revealed a clear reduction in the coefficient of friction and wear for all coated samples compared to uncoated PMMA. CBD-containing coatings, in particular, demonstrated high frictional stability. Among all tested systems, the SG9.5/CBD/GO coating delivered the most favorable performance, achieving a Shore D hardness of 86, low and stable friction, and minimal wear. These results suggest that the SG9.5/CBD/GO formulation is a promising candidate for durable and functional surface modification of PMMA in biomedical applications, such as dental prosthetics.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PMMA:

-

Polymethylmethacrylate

- GO:

-

Graphene oxide

- CBD:

-

Cannabidiol

- TEOS:

-

Tetraethoxysilane

- SG3:

-

SiO2 (pH = 3) coating

- SG9.5:

-

SiO2 (pH = 9.5) coating

- SG3/GO:

-

SiO2 (pH = 3) + GO composite coating

- SG3/CBD:

-

SiO2 (pH = 3) + CBD coating

- SG3/CBD/GO:

-

SiO2 (pH = 3) + CBD + GO composite coating

- SG9.5/GO:

-

SiO2 (pH = 9.5) + GO composite coating

- SG9.5/CBD:

-

SiO2 (pH = 9.5) + CBD coating

- SG9.5/CBD/GO:

-

SiO2 (pH = 9.5) + CBD + GO composite coating

- TGA:

-

Thermogravimetric analysis

- FTIR:

-

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

- XPS:

-

X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- Sa :

-

Mean roughness

- Sq :

-

RMS roughness

- Ssk :

-

Skew

- Sz :

-

Maximum height

- SFE:

-

Surface free energy

References

Zafar, M. S. Prosthodontic applications of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA): an update. Polymers 12, 2299 (2020).

Frazer, R. Q., Byron, R. T., Osborne, P. B. & West, K. P. PMMA: an essential material in medicine and dentistry. J. Long. Term Eff. Med. Implants. 15, 629–639 (2005).

Agop-Forna, D., Popa, P. S. & Popa, G. V. Pmma in dentistry: a modern solution for sustainable dental restorations. Med. Mater. 4, 77–84 (2024).

Pituru, S. M. et al. A review on the biocompatibility of PMMA-Based dental materials for interim prosthetic restorations with a glimpse into their modern manufacturing techniques. Mater. 2020. 13, 2894 (2020).

Canallatos, P. et al. Maxillary resection prosthesis fabricated from urethane dimethacrylate for a patient with polymethyl methacrylate allergy: a clinical report. J. Prosthet. Dent. 130, 655–658 (2023).

Pemberton, M. A. & Kimber, I. Methyl methacrylate and respiratory sensitisation: a comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 52, 139–166 (2022).

Samuelsen, J. T. & Dahl, J. E. Biological aspects of modern dental composites. Biomater. Investig. Dent. 10, 1425 (2023).

Ali, U., Karim, K. J. B. A. & Buang, N. A. A review of the properties and applications of Poly (Methyl Methacrylate) (PMMA). Polym. Rev. 55, 678–705 (2015).

Su, W., Wang, S., Wang, X., Fu, X. & Weng, J. Plasma pre-treatment and TiO2 coating of PMMA for the improvement of antibacterial properties. Surf. Coat. Technol. 205, 465–469 (2010).

Duchatelard, P., Baud, G., Besse, J. P. & Jacquet, M. Alumina coatings on PMMA: optimization of adherence. Thin Solid Films. 250, 142–150 (1994).

Paul, P., Pfeiffer, K. & Szeghalmi, A. Antireflection coating on PMMA substrates by atomic layer deposition. Coat. 10, 64 (2020).

Ziebowicz, A., Woźniak, A., Ziebowicz, B., Kosiel, K. & Chladek, G. The effect of atomic layer deposition of ZrO2 on the physicochemical properties of Cobalt based alloys intended for prosthetic dentistry. Arch. Metall. Mater. 63, 1077–1082 (2018).

Khan, J. et al. Design and evaluation of sustained release matrix tablet of flurbiprofen by using hydrophilic polymer and natural gum. Int. J. Med. Toxicol. Legal Med. 23, 149–159 (2020).

Bokov, D. et al. Nanomaterial by sol-gel method: synthesis and application. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 5102014 (2021).

Yeh, J. M., Weng, C. J., Liao, W. J. & Mau, Y. W. Anticorrosively enhanced PMMA–SiO2 hybrid coatings prepared from the sol–gel approach with MSMA as the coupling agent. Surf. Coat. Technol. 201, 1788–1795 (2006).

Singh, H. In-vitro bioactivity investigation and surface properties of a PMMA-SiO2 composite coating on SS-316L using the Sol-Gel technique. J. Adv. Mater. Eng.. https://doi.org/10.1177/09544062241249401 (2024).

Hajfarajzadeh, M. et al. Fabrication and characterization of an optical nano-hybrid sol-gel derived thin film on the PMMA substrate. J. Adv. Mater. Eng.. https://doi.org/10.29252/jame.36.3.1 (2022).

Garibay-Martínez, F. et al. Optical, mechanical and dielectric properties of sol-gel PMMA-GPTMS-ZrO2 hybrid thin films with variable GPTMS content. J. Non-Cryst. Solid (2021).

Baskaran, K. et al.. Sol-gel derived silica: a review of polymer-tailored properties for energy and environmental applications. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. (2022).

Kim, G. H. et al. Controllable synthesis of silica nanoparticle size and packing efficiency onto PVP-functionalized PMMA via a sol–gel method. Wiley Online Library 2020, 662–672 (2020).

Santana, J. A. et al. PMMA-SiO2 organic-inorganic hybrid coating application to Ti-6Al-4V alloy prepared through the sol-gel method. SciELO Brasil. 31, 409–420 (2020).

Ortiz, R., Chen, J. L., Stuckey, D. C. & Steele, T. W. J. Poly(methyl methacrylate) surface modification for Surfactant-Free Real-Time toxicity assay on droplet microfluidic platform. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 9, 13801–13811 (2017).

Harb, S. V. et al. PMMA-silica nanocomposite coating: effective corrosion protection and biocompatibility for a Ti6Al4V alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng., C. 110, 110713 (2020).

Fu, Y., Ni, Q. Q. & Iwamoto, M. Interaction of PMMA-silica in PMMA-silica hybrids under acid catalyst and catalyst-less conditions. J. Non Cryst. Solids. 351, 760–765 (2005).

dos Santos, F. C. et al. On the structure of high performance anticorrosive PMMA–siloxane–silica hybrid coatings. RSC Adv. 5, 106754–106763 (2015).

Wu, F., Wang, M., Su, Y., Chen, S. & Xu, B. Effect of TiO2-coating on the electrochemical performances of LiCo1/3Ni1/3Mn1/3O2. J. Power Sources. 191, 628–632 (2009).

Shen, G. X., Chen, Y. C., Lin, L., Lin, C. J. & Scantlebury, D. Study on a hydrophobic nano-TiO2 coating and its properties for corrosion protection of metals. Electrochim. Acta. 50, 5083–5089 (2005).

Scarano, A., Orsini, T., Di Carlo, F., Valbonetti, L. & Lorusso, F. Graphene-doped poly (methyl-methacrylate) (Pmma) implants: a micro-CT and histomorphometrical study in rabbits. Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 14523 (2021).

Darbandi, M., Panahi, P. & Asadpour-Zeynali, K. Fe (III) doped TiO2 nanoparticles prepared by high energy ball milling as booster for non-enzymatic, mediator-free and sensitive electrochemical sensor. Microchem. J. 183, 108093 (2022).

Martynková, G. S. & Valásková, M. Antimicrobial nanocomposites based on natural modified materials: a review of carbons and clays. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 14, 673–693 (2014).

Podila, R., Moore, T., Alexis, F. & Rao, A. Graphene coatings for biomedical implants. J. Vis. Exp. 2013, 50276. https://doi.org/10.3791/50276 (2013).

Fernandes Ramos, M. et al. Sourcing cannabis sativa L. by thermogravimetric analysis. Sci. Justice. 61, 401–409 (2021).

Muresan, P. et al. Evaluation of Cannabidiol nanoparticles and nanoemulsion biodistribution in the central nervous system after intrathecal administration for the treatment of pain. Nanomedicine 49, 102664 (2023).

Moqejwa, T., Marimuthu, T., Kondiah, P. P. D. & Choonara, Y. E. Development of stable nano-sized transfersomes as a rectal colloid for enhanced delivery of cannabidiol. Pharmaceutics 14, 1452 (2022).

Liu, L. et al. SiO2-GO nanofillers enhance the corrosion resistance of waterborne polyurethane acrylic coatings. Adv. Compos. Lett. 29, 2633366X20941524 (2020).

Poologasundarampillai, G. et al. Cotton-wool-like bioactive glasses for bone regeneration. Acta Biomater. 10, 3733–3746 (2014).

Díez, N., Śliwak, A., Gryglewicz, S., Grzyb, B. & Gryglewicz, G. Enhanced reduction of graphene oxide by high-pressure hydrothermal treatment. RSC Adv. 5, 81831–81837 (2015).

Park, S. E., Periathamby, A. R. & Loza, J. C. Effect of surface-charged poly(methyl methacrylate) on the adhesion of Candida albicans. J. Prosthodont. 12, 249–254 (2003).

Henriques, M., Azeredo, J. & Oliveira, R. Adhesion of Candida albicans and Candida Dubliniensis to acrylic and hydroxyapatite. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 33, 235–241 (2004).

Acknowledgements

Publication supported by the Excellence Initiative - Research University program. Silesian University of Technology, grant number: 07/020/SDU/10-27-03. REFRESH – Research Excellence For REgion Sustainability and High-tech Industries”, grant number: CZ.10.03.01/00/22_003/0000048. The publication was co-financed from the state budget under the "Excellent Science II" program of the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education, no. KONF/SP/0443/2024/02. The co-financing amount was PLN 249,000.00, and the total project value was PLN 334,500.00.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: M.A. Methodology: M.A., M.A., M.H., RC. Software: M.A., M.A. Validation: M.A.,M.A., M.H., Formal analysis: M.A., M.A., K.W., A.T., J.M., G.S., Investigation: M.A., M.A., M.H., K.W., G.S. R.C. Resources: M.A., M.A. Data curation: M.A., M.A. Writing-original draft: M.A., A.T., J.M., Writing-review&editing: M,A., G.S., R.C., Visualization: M.A., M.A., Supervision: M.A. Project administration: M.A., Funding acquisition: M.A.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Antonowicz, M., Hüpsch, M., Wilk, K. et al. Graphene oxide and cannabidiol-based hybrid coatings on PMMA for biomedical applications. Sci Rep 15, 41375 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25325-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25325-5