Abstract

Epigenetic regulation is a key driver of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs), yet the interplay between epigenetics and immune infiltration in the PNET tumor microenvironment remains poorly understood. This study investigates associations between epigenetic regulators and immune markers in PNETs to evaluate the potential for a combination of epigenetic-targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Immunohistochemical staining was performed on specimens from twenty-five Grade 1 or Grade 2 PNET patients, along with matched adjacent benign controls from each individual. Quantification was conducted using ImageJ software, followed by statistical analysis to assess correlations between epigenetic regulation and immune modulation. DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) was significantly upregulated in PNET samples, positively correlated with higher tumor grades and negatively correlated with 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-HMC) levels. Overexpression of DNMT3A and DNMT3B was also observed. Additionally, immune markers such as CD3, CD8, CCL5, and NFκB were significantly elevated, with CCL5 showing a grade-dependent increase. Interestingly, while PD-L2 was upregulated in tumors, there were no differences in the expression levels of PD-L1 and FOXP3 between PNET and adjacent benign controls. Additionally, DNMT1 expression positively correlated with Ki67, CD3, PD-L2, and CCL5 while inversely correlating with Menin. These findings suggest DNMT1 plays a significant role in immune modulation during PNET progression, highlighting the potential of combining DNMT1 inhibitors with immune checkpoint blockade as a therapeutic strategy to enhance outcomes for PNET patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs) are rare neoplasms, accounting for 2–7% of all pancreatic cancers, with an incidence of 1–2 cases per 100,000 individuals annually. Nonfunctional PNETs, which do not secrete hormones, represent the most common subtype. These tumors are characterized by slow disease progression, yet approximately 40–50% of patients present with metastatic disease at diagnosis, leading to poor survival outcomes1,2,3,4,5. Five-year survival rates vary depending on disease stage, with localized disease offering a survival rate of 60–100%, regional metastasis 40%, and distant metastatic disease only 25%6.

The standard of care includes treatment with somatostatin analogues (SSA) which provide antiproliferative and antisecretory effects on PNET7. In addition, the chemotherapy regimen capecitabine-temozolomide (CAPTEM), which is generally well-tolerated for metastatic disease, has been commonly employed, either alone or combined with other therapies, including SSA, mTOR inhibitors, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors. However, resistance to these agents frequently develops and surgical resection remains the cornerstone treatment for localized PNETs, underscoring the need for novel therapeutic approaches2,8,9,10,11. An emerging area of research is epigenetic therapy, which targets reversible DNA methylation changes without altering the DNA sequence. In PNETs, epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressor genes such as MEN1, DAXX, and RASSF1 through hypermethylation has been shown to promote tumor growth11,12. Preclinical studies indicate that hypermethylation of these tumor suppressor genes is primarily mediated by the enzyme DNA methyltransferase (DNMT1). The FDA-approved drug 5-azacytidine (5-AZA), a DNMT1 inhibitor used in the treatment of myeloproliferative disorders, has shown promise in inhibiting DNMT1 activity, thereby preventing the hypermethylation and subsequent silencing of tumor suppressor genes12. We previously demonstrated that 5-azacytidine, combined with the chemotherapy agent 5-fluorouracil, enhanced tumor regression compared to chemotherapy alone in murine STC-1 cells. Moreover, treatment of PNET cell lines with 5-azacytidine revealed a significant upregulation in several immunomodulatory pathways, suggesting a potential mechanism for epigenetic roles as key regulators of immune cell function and anti-tumor immunity and providing an avenue for combination therapy involving epigenetic agents and immunotherapy13.

Combination therapies of epigenetic therapy with immunotherapy are currently being investigated in several cancers, including advanced-stage pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, metastatic colorectal cancer, and stage IV non-small cell lung cancer as a strategy to overcome the limitations of immunotherapy in isolation14. Early clinical data on immune checkpoint blockade in PNETs has been less successful, likely attributable to factors such as low tumor mutational burden, insufficient T-cell infiltration, and lower expression of immune regulatory markers like Programmed Cell Death Protein1 and its ligands PD-L1 and PD-L213,14. The heterogeneity in morphology, behavior, and genetic alterations within PNETs2 has also led to inconsistent prognostic implications for these markers15. Our study aims to investigate the tumor microenvironment of PNETs in human tissue, including tumor suppressor genes and immune markers present, to determine the extent of immune modulation and explore whether there is an association between DNA hypermethylation and immune infiltration that could be leveraged for therapeutic intervention. We provide a comprehensive analysis of methylation processes in human PNETs, emphasizing the role of DNA methyltransferases on nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), a transcription factor that is central to immune and inflammatory responses with duality in promoting tumor cell survival and modulating the immune microenvironment16,17,18,19. Aberrant activation of NF-κB has been linked to epigenetic alterations, including promoter methylation and DNMT overexpression, which drive transcriptional changes favoring tumor progression20,21,22,23. This study investigates the effect of elevated DNMT1 expression on the upregulation of NF-κB and the correlation leading to the downstream impact on immune regulation and inflammatory pathways. This information can be utilized to define characteristics correlated with tumor and immune cell interaction and identify novel therapeutic targets that may improve outcomes for patients with PNETs.

Results

Baseline characteristics of PNET patients

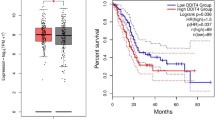

A total of 25 patients were included in this study, comprising 17 males and 8 females. The cohort’s median age was 65 years (IQR 59.5–72 years). All PNET specimens were histologically confirmed as well-differentiated PNETs. Among the specimens, 13 were classified as Grade 1 tumors, while 12 were Grade 2. Ki-67 scores were documented for all specimens, with a median score of 2% (IQR 1.0–4.0%) to support the grading of each WD-PNET based on the proliferative index24. Data on perineural invasion, perivascular invasion, nodal involvement, and metastasis were comprehensively recorded and are detailed in Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table S1. The median overall-survival for the cohort was 60 months (IQR 24–96 months). Beyond 60 months, survival rates declined sharply, with most patients not surviving beyond 7.5 years (Fig. 1B). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining confirmed tumor grade and diagnosis for all specimens, with adjacent benign tissue used as a baseline comparison. Representative images of three distinct patient samples, highlighting architectural differences between Grade 1 non-functional, Grade 1 functional, and Grade 2 non-functional PNETs, are shown in Fig. 1C. Adjacent benign tissues displayed uniformly globular acinar cells with well-preserved architecture, serving as a control for comparison. In contrast, Grade 1 non-functional tumors exhibited a transition from globular to linear and ribbon-like acinar cell morphology, with mild cellular disorganization and minimal nuclear atypia. Grade 1 functional tumors retained well-preserved architecture but displayed subtle atypical features, including increased vascularity and evidence of hormone-secreting activity, characterized by prominent nucleoli and mild cytoplasmic clearing. The more advanced Grade 2 tumors showed advanced pathological changes, including pronounced architectural disarray, a significant loss of globular acinar cell structures, increased nuclear splitting, and visible mitotic activity, indicative of higher tumor grade. Therefore, this cohort of PNET samples confirms the diagnosis of PNET and highlights the morphological differences between benign and malignant tissue and between tumor grades, ensuring accurate grade designation for all specimens1.

Baseline characteristics of PNET patients. (A) The cohort of 25 patients had a median age of 65 years, with 68% male and 32% female, and predominantly well-differentiated tumors. Tumors were most frequently located in the tail of the pancreas, with a median size of 2.0 cm, and a median overall survival of 60 months. (B) Logarithmic curve depicting overall survival in the PNET cohort. The graph demonstrates that survival the initial diagnosis was relatively stable for the first 60 months. Beyond 60 months, survival rates experienced a sharp decline, with majority of patients not surviving beyond 7.5 years. (C) Representative H&E-stained slides of surgically resected PNET specimens were analyzed to confirm pathology, differentiate tumor from benign tissue, and determine tumor grade. Samples include adjacent benign tissue, Grade 1 nonfunctional (NF) tumors, Grade 1 functional tumors, Grade 2 tumors, and their corresponding adjacent benign tissues. Insets in each panel highlight the morphological abnormalities characteristic of each tissue type. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

DNMT1 is overexpressed in PNETs

To evaluate the clinical and pathological significance of DNMT1 in PNETs, PNET patient tumor samples were used for immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, which was quantified using Image J software (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S1). IHC Staining revealed that DNMT1 demonstrated consistent overexpression across all tumor samples, with intensity correlating with tumor grade, suggesting an association with disease progression (Fig. 2A–C,V–X). In addition to DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B, key enzymes involved in de novo DNA methylation were overexpressed in 90% of the tumor samples, particularly in higher-grade tumors (Fig. 2D–C,V–X). Furthermore, 5-HMC, an epigenetic mark associated with active DNA demethylation, exhibited intense nuclear staining in benign tissues but was nearly absent in Grade 1 and Grade 2 PNETs samples (98.6%, Fig. 2H–I and V–W). Image Density scoring further revealed significant downregulation of Menin, a tumor suppressor and epigenetic modifier known to interact with DNMT1 in pancreatic cancer. Menin expression was markedly reduced in Grade 2 tumors compared to Grade 1 (Fig. 2M–O,V–X), supporting its role in tumor suppression and highlighting its progressive loss in advanced disease. RASSF1, another tumor suppressor known to be regulated by DNMT1-mediated hypermethylation, exhibited reduced expression in 92% of tumor samples. While benign tissues demonstrated intense RASSF1 staining, tumor tissues displayed a significant reduction (Fig. 2P–R,V–W). In contrast, PTEN, a commonly lost tumor suppressor in other solid tumors4, showed no statistically significant differences between tumor and benign samples (Fig. 2S–X), suggesting its loss may not be a universal feature in PNETs.

DNMT1 is overexpressed in PNETs. (A–U) Representative IHC Staining immune markers including DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B, 5-HMC, MEN1, RASSF1, PTEN, in adjacent benign, Grade 1, and Grade 2 tissue sections, respectively. Scale bars represent 50 μm. (V) Bar graph depicting abovementioned percentages of upregulation/downregulation of each marker, with Standard of Error plotted. (W) Box and whisker plot showing the range and median of density scores determined using the Mann-Whitney U test. The boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), with whiskers extending to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 × IQR. The horizontal line within each box indicates the median. Statistical significance is stratified by tumor versus benign groups. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001, and “ns” indicates not statistically significant. (X) Box and whisker plot showing the range and median of density scores determined using the Mann-Whitney U test. The boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), with whiskers extending to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 × IQR. The horizontal line within each box indicates the median. Statistical significance is stratified by Grade 1 versus Grade 2 groups. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001, and “ns” indicates not statistically significant.

DNMT1 expression correlates with PNET-Specific markers

To elucidate whether DNMT1 overexpression is associated with immune PNETs, Spearman correlation analysis was conducted between DNMT1 and key biological markers (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table S2). DNMT1 expression exhibited a strong positive correlation with Ki67, a PNET proliferation marker (r = 0.4713, p = 0.0174), and a negative correlation with Menin (r = − 0.5138, p = 0.0086), reinforcing DNMT1’s role as a driver of tumor growth and epigenetic silencing. No significant correlation was found between DNMT1 and other PNET-specific markers.

DNMT1 expression correlates with PNET-specific markers. Spearman Rho Correlation Test was performed to test correlation between DNMT1 density score against seven additional variables including other DNMTs and PNET markers. p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant. “+” indicates positive correlation. “-’’ indicates negative correlation. Solid lines represent the fitted regression models, while data points correspond to individual samples.

Immune signaling is upregulated in PNETs

Next, Immune marker expression was similarly evaluated in all human PNET samples via IHC. All 25 tumor samples (100%) exhibited positive staining for CD3 (Fig. 4A–C) and CD8 (Fig. 4D–F), markers indicative of T cell infiltration. Notably, CD3 and CD8 expression levels were more significant in Grade 2 than Grade 1 tumors (Fig. 4T–U), consistent with increased immune activity in more aggressive disease states. We further assessed the expression of immune checkpoint ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2, which are involved in immune evasion through the Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 signaling pathway. While PD-L1 staining yielded equivocal results, suggesting variable expression across PNET samples (Supplementary Fig. S2), PD-L2 demonstrated significant overexpression in high-grade tumors (Fig. 4G–I,T–U). Additionally, CCL5, a chemokine known to recruit T regulatory cells and facilitate Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 signaling, was significantly upregulated in Grade 2 tumors compared to Grade 1 (Fig. 4J–L,T–U). However, FOXP3, a transcription factor regulating Treg function and a downstream target of CCL5, showed no significant differences in expression between benign tissues and Grade 1 or 2 PNETs (Fig. 4M–O,T–U). The NF-κB pathway, a master regulator of inflammatory signaling and CCL5 activation20, was also examined. NF-κB demonstrated significant upregulation in all tumor samples, with expression levels more than twice those observed in benign tissues (Fig. 4P–S). Importantly, NF-κB expression did not vary significantly between tumor grades, suggesting its activation may be an early event in PNET tumorigenesis (Fig. 4U).

Immune signaling is upregulated in PNETs. (A–R) Representative IHC Staining immune markers including CD3, CD8, PDL2, FOXP3, CCL5, and NFκB, in adjacent benign, Grade 1, and Grade 2 tissue sections, respectively. Scale bars represent 50 μm. (S) Bar graph depicting abovementioned percentages of upregulation/downregulation of each marker, with Standard of Error plotted. (T) Box and whisker plot showing the range and median of density scores determined using the Mann-Whitney U test. The boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), with whiskers extending to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 × IQR. The horizontal line within each box indicates the median. Statistical significance is stratified by tumor versus benign groups. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001, and “ns” indicates not statistically significant. (U) Box and whisker plot showing the range and median of density scores determined using the Mann-Whitney U test. The boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), with whiskers extending to the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 × IQR. The horizontal line within each box indicates the median. Statistical significance is stratified by Grade 1 versus Grade 2 groups. Statistical significance is denoted as follows: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 ***p < 0.001, and “ns” indicates not statistically significant.

DNMT1 expression correlates with immune modulation in PNETs

To elucidate whether DNMT1 overexpression is associated with immune responses in PNETs, Spearman correlation analysis was conducted between DNMT1 and key immune markers (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table S2). DNMT1 expression exhibited a strong positive correlation with Ki67, a PNET proliferation marker (r = 0.4713, p = 0.0174), and a negative correlation with Menin (r = − 0.5138, p = 0.0086), reinforcing DNMT1’s role as a driver of tumor growth and epigenetic silencing. DNMT1 expression also correlated significantly with CD3 (r = 0.4313, p = 0.0313) and demonstrated strong correlations with PD-L2 (r = 0.7877, p < 0.0001) and CCL5 (r = 0.6882, p = 0.0001). These findings suggest that DNMT1 overexpression may influence tumor progression through modulation of T cell-mediated immune responses and checkpoint ligand expression. Interestingly, no significant correlations were observed between DNMT1 and CD8 (r = 0.2639, p = 0.2025), FOXP3 (r = 0.3255, p = 0.1123), or NF-κB (r = 0.2985, p = 0.1373), implying that DNMT1’s regulatory effects on these markers may be indirect in the parameters of this study.

DNMT1 expression correlates with immune modulation in PNETs. Spearman Rho Correlation Test was performed to test correlation between DNMT1 density score against six additional variables of immune signaling markers. p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant. “+” indicates positive correlation. “-’’ indicates negative correlation. Solid lines represent the fitted regression models, while data points correspond to individual samples.

Multiple signaling pathways correlate with immune modulation in PNET progression

In addition to DNMT1, we explored correlations between other epigenetic and immune markers to uncover the relationships underlying PNET progression. DNMT3A expression significantly correlated with CD3 (r = 0.4702, p = 0.0176), highlighting a potential link between de novo methylation and T-cell infiltration. Conversely, Menin expression exhibited a negative correlation with PD-L2 (r = − 0.4931, p = 0.0122), suggesting a role for Menin loss in immune evasion. RASSF1, a hypermethylation target, demonstrated significant negative correlations with CD3 (r = − 0.6563, p = 0.0004) and CD8 (r = − 0.4254, p = 0.0034) while showing a positive correlation with PD-L2 (r = 0.4216, p = 0.0358), indicating complex epigenetic regulation of immune responses. The multivariable matrix test presents a comprehensive list of all markers analyzed in this study (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table S2).

Multiple signaling pathways correlate with immune modulation in PNET progression. A correlation matrix analysis of 25 PNET tumor samples was performed using GraphPad Prism’s correlation matrix module. Spearman correlation coefficients and statistical significance are indicated for each variable pair (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns). The histogram on the right indicates the correspondence between color hues and Rho values.

We further performed hierarchical clustering heatmap analysis to validate the correlation between epigenetic markers and immune infiltration across distinct tumor groups. This analysis stratified biological groups based on correlations among gene expression patterns. Overall, 25 PNET patient samples were effectively grouped into benign tissues, Grade 1 tumors, and Grade 2 tumors, with a few outliers (Fig. 7). Notably, immune-related markers such as CCL5, PD-L2, CD3, and CD8 were closely clustered, reflecting the validation of their interconnected roles in PNET immune microenvironment. These findings underscore distinct expression patterns of molecular signaling pathways involved in epigenetic regulation and immune infiltration during PNET progression.

Hierarchical clustering heatmap analysis stratifies distinct PNET groups. A heatmap with hierarchical clustering illustrates the differential expression of tumor markers between tumor and benign tissues. Clustering was based on correlation distance and linkage. Rows represent tumor samples, and columns represent tumor marker clusters. The top-right histogram indicates the correspondence between color hues and z-scores.

Discussion

Our study reveals DNMT1’s dual role in promoting PNET progression by silencing tumor suppressors and disrupting immune regulation. DNMT1 overexpression strongly correlates with immune activity markers like PD-L2 and CCL5, indicating its role in driving immune evasion through epigenetic reprogramming. These findings are consistent with observations in other solid tumors, where DNMT overexpression silences immune-regulatory genes, activates immune checkpoints, and facilitates tumor progression and escape19.

The strong association between DNMT1 expression and immune markers highlights its potential as a prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target in PNETs. Epigenetic therapies, such as DNMT inhibitors (e.g., decitabine or 5-AZA), could reverse DNMT1-driven immune suppression and enhance the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Our study also identifies significant immune microenvironment alterations in PNETs, including increased T cell infiltration (CD3 + and CD8 +) and upregulation of immune checkpoint ligands, particularly PD-L2. These changes were more pronounced in higher-grade tumors, indicating a robust immune response. However, the overexpression of PD-L2 in Grade 2 tumors suggests additional immune evasion via the Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 /PD-L2 axis, consistent with observations in gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors and other malignancies, where PD-L2 upregulation correlates with poor immune response and tumor progression25,26,27,28. Additionally, we observed significant CCL5 upregulation, particularly in higher-grade tumors. As a chemokine known to recruit T regulatory cells and modulate immune checkpoint pathways, elevated CCL5 likely contributes to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment that supports tumor progression29. Notably, FOXP3, a marker of Treg function, showed no significant variation across tumor grades or between benign and malignant tissues, nor did it correlate with DNMT1. The elevated CD3 and CD8 levels observed in our study suggest an active tumor microenvironment with robust T cell infiltration that do not rely heavily on FOXP3-dependent CD4 + Tregs in PNETs. Instead, the immune suppression in PNETs may involve CCL5-mediated recruitment of other suppressive immune subsets.

NF-κB levels were more than twice as high in all tumor samples when compared with benign tissues and were activated early in PNET development, independent of tumor grade, suggesting that it is a critical regulator of inflammation and immune signaling. Given NF-κB’s role in driving CCL5 expression and immune cell recruitment22,23, this pathway likely underpins the chronic inflammation and immune landscape alterations characteristic of PNETs. Hierarchical clustering and correlation analyses further underscored the interplay between epigenetic regulation and immune modulation in PNETs30,31,32. The clustering of immune markers, such as PD-L2, CCL5, CD3, and CD8, highlights a strong immune response alongside the activation of immune evasion mechanisms, particularly in higher-grade tumors. These results support of a model where DNMT1 overexpression drives epigenetic silencing of tumor suppressors and immune-regulatory genes, facilitating immune evasion, chronic inflammation, and tumor progression33. Future follow-up experiments, including gain- and loss-of-function experiments that utilize siRNA or small-molecule DNMT1 inhibitors to modify DNMT activities in PNET tumor cell lines and xenograft mouse models, will be needed to further validate the regulatory network linking epigenetics to immune response in this study. Due to the limited sample size, even though a substantial portion of epigenetic and immune infiltration markers were significantly upregulated in tumor samples compared to benign samples, the correlation analysis did not reveal statistically significant positive associations. Moving forward, our group aims to collaborate across multiple medical institutions to include a larger cohort of PNET samples, thereby expanding the scope of the correlation study. This approach will enhance our understanding of the molecular events underlying PNET progression and facilitate the development of improved diagnostic and predictive tools, potentially leveraging the ever-advancing artificial intelligence technology. Additionally, Genome-wide transcriptomic analyses could further elucidate DNMT1’s role in regulating immune-related gene expression and its downstream effects on the tumor immune microenvironment.

In the present study, we mainly focused on the relationship between DNA methylation and T cell modulation in PNET, as our primary objective was to investigate the link between epigenetic regulation and immune response, thereby identifying potential targets for immunotherapy. T cells, as central components of adaptive immunity, remain a cornerstone of immunotherapeutic strategies due to their antigen specificity and robust tumor-killing capabilities34,35. It needs to be pointed out that PNET progression is closely related with the tumor associated microenvironment, which includes not only T cells but also other immune cell types such as tumor-associated macrophages, natural killer cells, and mast cells34,35,36,37,38,39,40. In future studies, we plan to expand our analysis to explore the correlation between DNMT1 and other immune cell types. This broader investigation could help identify novel combinations of epigenetic and immunotherapeutic strategies for PNET, particularly given the emerging success of non–T cell–based immunotherapies in treatment of both PNET and other malignancies40,41.

Evidence from other malignancies indicates that targeting DNMT1 with epigenetic therapies can restore immune sensitivity and enhance the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors42,43. Mechanistically, DNMT1 can promote immune evasion by silencing genes which are critical to anti-tumor immune responses44. For example, DNMT1 has been shown to regulate PD-L1 expression, a key immune checkpoint molecule that enables tumor cells to escape immune surveillance. Additionally, DNMT1 also limits the anti-tumor effects of interferon-beta (IFN-β), a cytokine involved in innate and adaptive immunity45. Given the observed correlation between DNMT1 expression and immune modulation in our study, further investigation is warranted to evaluate the therapeutic potential of DNMT1-specific inhibition in PNET treatment. Our ultimate goals are to better define the nature of immune response in the PNET tumor microenvironment46 and explore preclinical models to evaluate the therapeutic potential of combining DNMT inhibitors with immunotherapy, particularly focusing on PD-L2 and CCL5 pathways.

Methods

All patients were diagnosed via symptoms and tissue confirmation with an endoscopic ultrasound guided pancreatic biopsy. None of these patients received neoadjuvant therapy. These patients underwent surgery between 2013 and 2019, after which their tumor tissue was processed by the Cooper Hospital pathology labs and samples were embedded in paraffin. All patients underwent radial resection. 21 out of 25 patients underwent a distal pancreatectomy and splenectomy for a PNET located in the tail of the pancreas and 4 out of 25 patients underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy for a PNET located in the head of the pancreas. All patients had appropriate lymph node harvesting as well. 19 out of the 25 patients did not have adjuvant chemotherapy due to their low grade, well-differentiated PNET as recommended by the NCCN criteria at the time of surgery. 4 out of the 25 patients did undergo adjuvant chemotherapy with octreotide due to metastatic disease at the time of surgery. Finally, 2 out the 25 patients deceased prior to discharge due to infectious complications.

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were sectioned at 5-µm intervals and mounted onto slides for subsequent analysis. Immunohistochemical staining was performed as described previously13. Adjacent benign tissues served as controls. In brief, tissue sections were first deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series, followed by distilled water. Antigen retrieval was performed using Tris-EDTA buffer in a microwave pressure cooker. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min. Sections were then incubated in blocking serum (Optimax buffer, BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) for 1 h, followed by overnight incubation with primary antibodies in Optimax buffer at 4 °C. The next day, sections were washed with phosphate-buffered saline with tween-20, then probed with a biotinylated anti-mouse IgG antibody (dilution 1:200, Cat No. BA-2000, Vector Laboratories, CA) for 30 min. After further PBS-T washes, an avidin-biotin complex (ABC, Cat No. PK-6100, Vector Laboratories, CA) was applied for 30 min, and sections were visualized using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated through increasing concentrations of ethanol, cleared with xylene, and mounted in Permount. Epigenetic markers were assessed using specific antibodies, including 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5-HMC), DNMT1, DNMT3A, and DNMT3B. Additionally, tumor suppressor genes of interest were evaluated, including MEN1, RASSF1, and PTEN, along with transcription factor NF-κB. Immune markers, including CD3, CD8, CCL5, FOXP3, PD-L1, and PD-L2, were also included in the analysis. A detailed description of antibodies in this study is provided in Supplementary Table S3. Stained sections were quantitatively analyzed using Image J software and reviewed by a board-certified pathologist using an Olympus BX43 microscope. Negative controls were prepared by substituting primary antibodies with phosphate-buffered saline.

Statistical analyses, including Mann Whitney U Test, Spearman Rho Correlation Test, and multiple variable matrix test, were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 to assess differences in epigenetic and immune expression patterns between tumor and benign tissues. Unsupervised hierarchical analysis was conducted utilizing the online platform provided by the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

Data availability

Supplementary figures are provided. Additional data supporting the conclusions of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request through Cooper University Hospital. Access to these data is subject to restrictions in accordance with HIPAA guidelines to ensure patient confidentiality.

References

Guilmette, J. M. & Nosé, V. Neoplasms of the neuroendocrine pancreas: An update in the classification, definition, and molecular genetic advances. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 26, 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/pap.0000000000000201 (2019).

Zhou, C., Zhang, J., Zheng, Y. & Zhu, Z. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Cancer. 131, 1013–1022. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.27543 (2012).

Halfdanarson, T. R., Rabe, K. G., Rubin, J. & Petersen, G. M. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PNETs): incidence, prognosis and recent trend toward improved survival. Ann. Oncol.: Of. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 19, 1727–1733. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdn351 (2008).

Boninsegna, L. et al. Malignant pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour: Lymph node ratio and Ki67 are predictors of recurrence after curative resections. Eur. J. Cancer (Oxford England: 1990). 48, 1608–1615. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2011.10.030 (2012).

Dasari, A. et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the united States. JAMA Oncol. 3, 1335–1342. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589 (2017).

Chauhan, A. et al. Critical updates in neuroendocrine tumors: Version 9 American joint committee on cancer staging system for gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancer J. Clin. 74, 359–367. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21840 (2024).

Mpilla, G. B., Philip, P. A., El-Rayes, B. & Azmi, A. S. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Therapeutic challenges and research limitations. World J. Gastroenterol. 26, 4036–4054. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v26.i28.4036 (2020).

Dogan, I., Tastekin, D., Karabulut, S. & Sakar, B. Capecitabine and Temozolomide (CAPTEM) is effective in metastatic well-differentiated Gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors. J. Dig. Dis. 23, 493–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-2980.13123 (2022).

Stueven, A. K. et al. Somatostatin analogues in the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors: Past, present and future. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20123049 (2019).

Frost, M., Lines, K. E. & Thakker, R. V. Current and emerging therapies for PNETs in patients with or without MEN1. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrendo.2018.3 (2018).

Falconi, M. et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of patients with functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and non-functional pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Neuroendocrinology 103, 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1159/000443171 (2016).

Saleh, Z. et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: signaling pathways and epigenetic regulation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25021331 (2024).

Zhu, C. et al. Novel treatment strategy of targeting epigenetic dysregulation in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Surgery 173, 1045–1051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2022.12.008 (2023).

Topper, M. J., Vaz, M., Marrone, K. A., Brahmer, J. R. & Baylin, S. B. The emerging role of epigenetic therapeutics in immuno-oncology. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-019-0266-5 (2020).

Yang, M. et al. World health organization grading classification for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms: A comprehensive analysis from a large Chinese institution. BMC Cancer. 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-020-07356-5 (2020).

Rindi, G. et al. Overview of the 2022 WHO classification of neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr. Pathol. 33, 115–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12022-022-09708-2 (2022).

Cowan, L. A., Talwar, S. & Yang, A. S. Will DNA methylation inhibitors work in solid tumors? A review of the clinical experience with Azacitidine and decitabine in solid tumors. Epigenomics 2, 71–86. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi.09.44 (2010).

Maharjan, C. K. et al. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Cancers 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13205117 (2021).

Hu, C., Liu, X., Zeng, Y., Liu, J. & Wu, F. DNA methyltransferase inhibitors combination therapy for the treatment of solid tumor: Mechanism and clinical application. Clin. Epigenet. 13 (2021).

Hoesel, B. & Schmid, J. A. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol. Cancer. 12, 86. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-4598-12-86 (2013).

Lu, T. & Stark, G. R. NF-κB: regulation by methylation. Cancer Res. 75, 3692–3695. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-15-1022 (2015).

Mauro, C., Zazzeroni, F., Papa, S., Bubici, C. & Franzoso, G. In In inflammation and cancer: Methods and protocols: Volume 2: Molecular analysis and pathways. 169–207 (eds Kozlov, S. V.) (Humana, 2009).

Perkins, N. D. Post-translational modifications regulating the activity and function of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway. Oncogene 25, 6717–6730. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1209937 (2006).

McCall, C. M. et al. Grading of well-differentiated pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors is improved by the inclusion of both Ki67 proliferative index and mitotic rate. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 37, 1671–1677. https://doi.org/10.1097/pas.0000000000000089 (2013).

Greenberg, J. et al. Metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors feature elevated T cell infiltration. JCI Insight. 7 https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.160130 (2022).

Lee, J., Ahn, E., Kissick, H. T. & Ahmed, R. Reinvigorating exhausted T cells by Blockade of the PD-1 pathway. Forum Immunopathol. Dis. Ther. 6, 7–17. https://doi.org/10.1615/ForumImmunDisTher.2015014188 (2015).

Okadome, K. et al. Prognostic and clinical impact of PD-L2 and PD-L1 expression in a cohort of 437 oesophageal cancers. Br. J. Cancer. 122, 1535–1543. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-0811-0 (2020).

Hoffmann, F. et al. Prognostic and predictive value of PD-L2 DNA methylation and mRNA expression in melanoma. Clin. Epigenetics. 12, 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-020-00883-9 (2020).

Rodriguez, A. B. & Engelhard, V. H. Insights into Tumor-Associated tertiary lymphoid structures: Novel targets for antitumor immunity and cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 8, 1338–1345. https://doi.org/10.1158/2326-6066.Cir-20-0432 (2020).

Duan, S. et al. Spatial profiling reveals tissue-specific neuro-immune interactions in gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J. Pathol. 262, 362–376. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.6241 (2024).

Takahashi, D. et al. Profiling the tumour immune microenvironment in pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms with multispectral imaging indicates distinct subpopulation characteristics concordant with WHO 2017 classification. Sci. Rep. 8, 13166. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-31383-9 (2018).

Hofving, T. et al. The neuroendocrine phenotype, genomic profile and therapeutic sensitivity of GEPNET cell lines. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 25, 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1530/erc-17-0445 (2018).

Chen, X. et al. Differential roles of human CD4 + and CD8 + regulatory T cells in controlling self-reactive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 26, 230–239. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41590-024-02062-x (2025).

Zhang, Y. & Zhang, Z. The history and advances in cancer immunotherapy: Understanding the characteristics of tumor-infiltrating immune cells and their therapeutic implications. Cell Mol. Immunol. 17, 807–821. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41423-020-0488-6 (2020).

Grywalska, E., Pasiarski, M., Góźdź, S. & Roliński, J. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors for combating T-cell dysfunction in cancer. OncoTargets Therapy. 11, 6505–6524. https://doi.org/10.2147/ott.S150817 (2018).

Cai, L. et al. Role of Tumor-Associated macrophages in the clinical course of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs). Clin. Cancer Research: Official J. Am. Association Cancer Res. 25, 2644–2655. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-1401 (2019).

Krug, S. et al. Therapeutic targeting of tumor-associated macrophages in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Int. J. Cancer. 143, 1806–1816. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.31562 (2018).

Aparicio-Pagés, M. N., Verspaget, H. W., Peña, A. S., Jansen, J. B. & Lamers, C. B. Natural killer cell activity in patients with neuroendocrine tumours of the Gastrointestinal tract; relation with Circulating Gastrointestinal hormones. Neuropeptides 20, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0143-4179(91)90033-f (1991).

Soucek, L. et al. Mast cells are required for angiogenesis and macroscopic expansion of Myc-induced pancreatic islet tumors. Nat. Med. 13, 1211–1218. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1649 (2007).

Soucek, L. et al. Modeling Pharmacological Inhibition of mast cell degranulation as a therapy for Insulinoma. Neoplasia (New York N Y). 13, 1093–1100. https://doi.org/10.1593/neo.11980 (2011).

Du, N., Guo, F., Wang, Y. & Cui, J. N. K. Cell therapy: A rising star in cancer treatment. Cancers 13 https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13164129 (2021).

Aumer, T. et al. The type of DNA damage response after decitabine treatment depends on the level of DNMT activity. Life Sci. Alliance. 7 https://doi.org/10.26508/lsa.202302437 (2024).

Maslov, A. Y. et al. 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine-induced genome rearrangements are mediated by DNMT1. Oncogene. 31, 5172–5179. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.9 (2012).

Kerdivel, G. et al. DNA hypermethylation driven by DNMT1 and DNMT3A favors tumor immune escape contributing to the aggressiveness of adrenocortical carcinoma. Clin. Epigenetics. 15, 121. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-023-01534-5 (2023).

Huang, K. C. et al. DNMT1 constrains IFNβ-mediated anti-tumor immunity and PD-L1 expression to reduce the efficacy of radiotherapy and immunotherapy. Oncoimmunology 10, 1989790. https://doi.org/10.1080/2162402x.2021.1989790 (2021).

Sharma, P. & Allison, J. P. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 348, 56–61. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa8172 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a research grant from Cooper University Health Care.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.S. and R.N. contributed equally to this study. Z.S., R.N., F.S., T.G., and Y.K.H conceptualized the original idea and planned the experiments. Z.S., R.N., M.M., Y.G., H.J., and Y.L. carried out the experiments. Z.S., R.N., and U.J. conducted the statistical analysis. Z.S., R.N., A.K., T.G., and Y.K.H. wrote and edited the manuscript. T.G. and Y.K.H. co-supervised the study and obtained the funding. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The experiment was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and approval by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Cooper University Hospital (IRB 23–130). The collection, storage, and processing of PNET samples were carried out in strict accordance with the guidelines and regulations set by the IRB.

Informed consent

was waived by Cooper University Hospital.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Saleh, Z., Nation, R.J., Moccia, M.C. et al. DNA methyltransferase 1 correlates with immune modulation in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Sci Rep 15, 41497 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25384-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25384-8