Abstract

Developing reasonable energy management strategy(EMS) to coordinate the working status of various power sources is the key to ascendancy the energy-saving advantages of power-split hybrid electric bus. However, few optimal control strategies have been conducted to utilize operating condition information to achieve approximate online global optimization of energy-saving algorithms, and maximize energy-saving potential. Aiming at the problem, a real-time adaptive EMS based on improved DP algorithm and control rule extraction is proposed for a power-split HEB in this paper. An improved DP algorithm based on secant method for solve the lack of theoretical basis for determining weight coefficients is constructed. The optimal control rules are extracted through outlier detection and graphical method. And an online adaptive algorithm within Relevance Vector Machine and particle swarm optimization algorithm is performed to achieve online adaptive optimal effect. Finally, the simulation and hardware-in-the-loop test are conducted. Simulation results validate that control algorithm proposed in this paper is close to DP results, while achieving the 14.6% oil saving compared with logic threshold control. Additionally, the control algorithm proposed in this paper also demonstrates good real-time performance. The main contribution of this paper is to explore a novel way to fully exert the fuel economy potential and adaptability of power-split HEB in various cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The hybrid power system integrates the advantages of traditional internal combustion engine vehicle (long driving range) and pure electric vehicles (excellent energy-saving potential), making it a core focus in the research field of energy-saving vehicles in China1,2,3. Among various hybrid technology solutions, the power-split hybrid system decouples the engine from the vehicle drivetrain and enables the electric continuously variable transmission function, endowing it with superior power performance and remarkable energy-saving capabilities4. In the fierce market competition, maximizing fuel-saving potential under real-world driving conditions has become the core factor for power-split hybrid systems to maintain product competitiveness5.

The power-split system integrates multiple power sources with complex nonlinear efficiency characteristics, and the fuel-saving performance across different application scenarios is highly dependent on the energy management strategy (EMS)6,7,8,9. This study proposes a real-time adaptive EMS for power-split hybrid electric buses (HEBs), which is developed based on an enhanced dynamic programming (DP) algorithm and control rule extraction. The approach employs the improved DP algorithm for offline global optimization: it adopts equivalent fuel consumption as the single-step cost function and applies the secant method to calculate weight coefficients, aiming to minimize overall fuel consumption. To enhance real-time performance, the optimized DP data undergoes pattern recognition and rule extraction via outlier detection and graphical analysis methods. Additionally, a relevance vector machine (RVM) is used for driving cycle identification to select appropriate control parameters, while an advanced particle swarm optimization algorithm is developed to optimize these parameters across various driving cycles.

Literature review

Currently, the DP algorithm has been proven effective in achieving optimal fuel economy over specific driving cycles. Gong Q et al. applied the DP algorithm to optimize the control strategy of a plug-in hybrid system under charge-depletion mode, resulting in improved fuel economy10. Peng J et al. recalibrated the EMS using DP optimization results, achieving a comprehensive reduction in both fuel and electricity consumption11. Goos J et al. employed the DP algorithm for global optimization and conducted sensitivity analysis of key parameters, providing guidance for optimization design12. However, the DP algorithm requires prior knowledge of the entire driving cycle and involves high computational complexity, making it challenging to implement in online control applications without integration with other methods.

EMS based on transient optimization are feasible for online applications, with common approaches including the equivalent consumption minimization strategy (ECMS), reinforcement learning (RL), and model predictive control (MPC). ECMS is capable of yielding near-optimal energy consumption solutions13,14,15,16. He et al. investigated key parameters influencing the online implementation of the adaptive ECMS (A-ECMS), further enhancing the performance of online optimal control17. Borhan et al. applied linear time-varying MPC and nonlinear MPC to realize the online optimization of ECMS. Simulation results indicated that ECMS based on nonlinear MPC achieves superior fuel economy18. Lian et al. constructed a nonlinear regression neural network to predict the future speed of urban buses and adopted a mixed linear programming algorithm for the rolling optimization of MPC, which significantly improved the vehicle fuel efficiency19.

In the field of RL-based EMS, deep reinforcement learning (DRL) has emerged as a mainstream direction in recent years, driven by its ability to handle high-dimensional state spaces and real-time decision-making requirements. Wu Y et al. proposed a DRL-based energy management strategy: by designing an adaptive reward function that tracks battery SOC, the strategy achieved the 8.63% fuel saving compared with the equivalent fuel consumption minimization approach20. Wang H et al. proposes a multiconstrained DRL-based EMS, results show that compared with the baseline TD3, the proposed EMS can reduce the FC degradation rate by 10.49%, improve the SOC maintenance, and above 95% global optimum of the DP method21. Zare A et al.presents an intelligent EMS based on a hybrid Knowledge-Assisted system that integrates a Deterministic Policy Gradient (KA-DDPG) and a Deep Q-Network (KA-DQN), results show that KA-DDPG requires less computation time, reduces fuel consumption by 5.18%-5.67% in online mode, and maintains SOC stability22. Jia C et al. proposes a novel energy management paradigm. The comprehensive control of cabin comfort and fuel cell/battery durability is achieved by comprehensively utilizing onboard sensors and vehicle-cloud infrastructure, compared with rule-based EMSs, the proposed strategy achieves cabin comfort while extending the battery life by at least 3.79%23.

While DRL demonstrates significant advantages in high-dimensional optimization and multi-scenario adaptation, it was not adopted as the core control method in this study. The specific reasons are as follows:

First, DRL exhibits a strong reliance on high-quality, large-scale labeled training data, which poses challenges for the specific research object of this study—hybrid urban buses. The driving cycles of urban buses are significantly influenced by route characteristics (bus stop density, traffic signal timing) and operational schedules (passenger load during peak hours), resulting in substantial discrepancies between actual bus operation data and public datasets such as NEDC and WLTC. Moreover, collecting and labeling a sufficient volume of route-specific bus driving data requires coordination with bus company operational arrangements, making it difficult to complete within a short timeframe. Second, as public transport vehicles, urban buses have strict requirements for safety and reliability. During actual operation, they may encounter unexpected scenarios not covered in the training set. The control stability of DRL still needs improvement when facing such unseen extreme conditions.

Additionally, control rule extraction methods based on DP optimization results can effectively enable the online implementation of control strategies, making them an important category of online optimization approaches24,25,26. Zhang et al. proposed a DP-based algorithm to derive the optimal control strategy for minimizing fuel consumption over a specified driving cycle27. Chen et al. employed a recalibration approach to enhance the performance of rule-based energy management, leveraging results computed via the DP algorithm28. Kum et al. adopted a comprehensive rule extraction method, extracting mode-switching rules by analyzing DP optimization results29. The key advantage of this method lies in its ability to preserve both the real-time performance of the control strategy and control effects that approximate the DP-derived optimality. However, when the target driving conditions change, the original objective function often fails to maintain effective adaptability to the new driving cycle.

Real-time acquisition of vehicle operating states and road traffic conditions can be integrated into the DP algorithm, and the combination of data exchange and EMS enables optimal energy allocation decisions30,31,32,33. Wang X et al. adopted the New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) as the vehicle test cycle and developed a globally optimal control strategy for different driving ranges34. Xu et al. proposed a hybrid algorithm that integrates an energy-efficient path planning algorithm with a RL strategy, investigating the impact of driving conditions on the computation time of EMS and the optimization of energy flow allocation35. Wang W et al. acquired traffic information (including driving cycles and road speed limits) for PHEBs via onboard sensors and further leveraged this data for energy management36. For heavy-duty commercial vehicles sensitive to load change, Liu Z et al. innovatively integrated vehicle weight variation into the construction of multi-dimensional driving cycles. Combining Markov chain modeling with big data analysis, this study quantified the impact of load change on cycle characteristics and energy consumption, highlighting the significance of the load factor in multi-dimensional driving cycle optimization37. For hybrid electric buses operating in complex terrain environments, Li Y et al. systematically incorporated terrain information into the design of EMS. Based on an improved DDPG algorithm, this study achieved the optimization of a discrete-continuous hybrid action space. Compared with strategies that do not consider terrain, integrating terrain information could improve fuel economy by approximately 2%38. However, since the urban buses studied in this paper mainly operate on urban route in daily operations, where the terrain is mostly flat, and the impact of short-term load fluctuations on energy consumption is usually smaller than that of traffic condition changes. Therefore, this study focuses on the scenario characteristics of urban buses (short-distance, multi-stop, and traffic conditions dominating energy consumption) to achieve adaptive control for urban buses.

Research gaps and contributions

Among existing studies, the core challenge lies in how to leverage driving condition information to achieve near-optimal online global optimization of energy-saving algorithms while maximizing energy-saving potential. To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes an adaptive energy-saving optimization algorithm for power-split hybrid vehicles, which is based on improved DP and control rule extraction. Compared with recent studies that apply multi-constrained or multi-objective DRL to vehicle energy management21,39, this research exhibits two key distinctions: In terms of algorithm design, it differs from DRL reliance on large-scale labeled training data and complex reward functions. Instead, it combines the global optimization capability of improved DP with rule extraction, enabling fast online adaptation while supporting both small-sample regulatory driving cycles and mixed driving cycles. In terms of application scenarios, it focuses on power-split hybrid electric urban buses (targeting scenarios characterized by short distance, frequent stop, and significant traffic impact) rather than FCHEVs or adaptive cruise control (ACC) scenarios. This avoids the relative instability of DRL under untrained bus-specific operating conditions and better aligns with the real-time control requirements of urban buses. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows.

-

(1)

A method for extracting near-optimal control rules with an online application basis is proposed. This method extracts control rules through visual visualization and identifies data derived from the DP algorithm in a pattern-based manner, which effectively reduces computational cost and enables real-time optimization.

-

(2)

A variable-parameter control strategy based on driving cycle recognition is proposed. Leveraging a RVM model for real-time driving cycle identification, this method selects the corresponding optimal control parameters, thereby achieving variable-parameter optimal control.

Paper organization

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Following the introduction, Sect. 2 describes the power-split system configuration. The adaptive optimization algorithm based on improved dynamic programming and control rule extraction is presented and implemented in Sect. 3. Section 4 validates the online optimal control strategy under the offline simulation and HIL experiment. Section 5 presents the conclusion of the study.

Structure of the power system

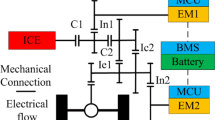

The structure of power-split HEB is shown in Fig. 1.The main parts of the hybrid powertrain system include an engine, two PG sets, two motor/generators and battery package. The PG1 set is the power-split device and the PG2 set is the reducer given its fixed ring gear. The engine output shaft is connected to the carrier of PG1. Motor/generator (MG1) is connected to the front sun gear while MG2 is connected to the rear sun gear. The ring gear of PG1 is connected to the carrier of PG2, which is connected to the final drive. The battery package is used as the electric energy storage.

Model construction

-

(a)

Vehicle longitudinal dynamics: The required power during the vehicle operation process is necessary for EMS design. Generally, the required power\({P_{req}}\)of HEV can be calculated by the vehicle longitudinal dynamics40, which is given as follow.

$$\begin{gathered} {P_{req}}={F_t}v=({F_f}+{F_w}+{F_i}+m\dot {v})v \hfill \\ {\text{ }}=(mgf\cos {\alpha _{inc}}+mg\sin {\alpha _{inc}}+0.5{C_D}A\rho {\omega _w}^{2}R_{w}^{2}+m\dot {v})v \hfill \\ \end{gathered}$$(1)Where\({F_t}\)represents the traction force provided by the driving motor;v represents the vehicle speed; \({R_w}\)represents the wheel radius; g, f,\({\alpha _{inc}}\)represent gravity, rolling resistance coefficient and incline angle respectively; \({C_D}\), A,\(\rho\)indicate drag coefficient, vehicle frontal area, air density respectively.

-

(b)

Engine fuel consumption: A steady-state fuel consumption map of the engine is applied. which is from engine expression data of test bench, and the fuel consumption rate\({\dot {m}_f}\), can be defined as formula (2):

$${\dot {m}_f}=f({\omega _e},{T_e})$$(2)where\({T_e}\)is the torque of the engine, \({\omega _e}\) is the rotational speed of the engine.

-

(c)

Motor efficiency: A motor efficiency map is employed, which is bound up with the speed and torque of the motor:

$$\left\{ \begin{gathered} {\eta _{MG1}}=f({\omega _{MG1}},{T_{MG1}}) \hfill \\ {\eta _{MG2}}=f({\omega _{MG2}},{T_{MG2}}) \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.$$(3)where\({\eta _{MG1}}\)and\({\eta _{MG1}}\)are the efficiency of MG1 and MG2, \({\omega _{MG1}}\)and\({\omega _{MG2}}\)are the rotational speed of MG1 and MG2, \({T_{MG1}}\)and\({T_{MG2}}\)are the torque of MG1 and MG2.

-

(d)

Planetary gear mechanism: Ignoring the internal rotational inertia and friction loss, the basic speed and torque relationship of the planetary gear mechanism can be obtained, as shown in formula (4).

$$\left\{ \begin{gathered} {T_{S1}}={T_{C1}}/(1+{k_1}) \hfill \\ (1+{k_1}){\omega _{C1}}={k_1}{\omega _{R1}}+{\omega _{S1}} \hfill \\ {T_{S2}}={T_{C2}}/(1+{k_2}) \hfill \\ (1+{k_2}){\omega _{C2}}={\omega _{S2}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.$$(4)Where T and\(\omega\)represent torque and speed respectively; Subscripts\(C1\),\(S1\), and\(R1\)represent the planetary carrier, sun gear, and ring gear of PG1, Subscripts\(C2\)and\(S2\)represent the planetary carrier and sun gear of PG2, and\({k_1}\), \({k_2}\)is the characteristic parameter of PG1 and PG2, which is the ratio of the number of teeth on the ring gear to the number of teeth on the sun gear.

-

(e)

Power battery: The battery is modeled as the equivalent circuit, which consists of a voltage source and a resistor41. The internal resistance of the battery\({R_{bat}}\)and open-circuit voltage\({V_{bat}}\), which are a function of the battery SOC\(SO{C_{bat}}\). Formulated by Kirchhoff’s voltage law, the current of the battery\({I_{bat}}\)and\(SO{C_{bat}}\)are expressed as follows.

$${I_{bat}}=\frac{{{V_{bat}} - \sqrt {V_{{bat}}^{2} - 4{R_{bat}}{P_{bat}}} }}{{2{R_{bat}}{P_{bat}}}}$$(5)Where\({P_{bat}}\)represents the power of the battery.\({Q_{bat}}\)is the battery capacity.\(SO{C_{bat0}}\)represents the initial SOC of the battery, Based on the battery model, the\(SO{C_{bat}}\)can be calculated by formula (6).

$$S\dot {O}{C_{bat}}=\frac{{ - {I_{bat}}}}{{{Q_{bat}}}}$$(6)Based on the connection relationships between each power source and the planetary gear, the relationship between the system output speed and torque can be derived, as shown in formula (7):

$$\left\{ \begin{gathered} {T_{out}}={T_e}\frac{{{k_1}}}{{1+{k_1}}}+{T_{MG2}}{i_2},{i_2}=1+{k_2} \hfill \\ {\omega _{out}}=\frac{{{\omega _e}(1+{k_1}) - {\omega _{MG1}}}}{{{k_1}}}=\frac{{{\omega _{MG2}}}}{{{i_2}}} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.$$(7)Where subscript\(out\)represents the output axis.

Design of energy management strategy

This paper proposes a real-time EMS for power-split hybrid electric vehicles, designed to enhance fuel economy by integrating three key factors: global optimization, real-time performance, and driving cycle adaptability. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the proposed strategy comprises three components: (1) An improved DP algorithm based on the secant method; (2) Control rule extraction; (3) An online adaptive control algorithm.

To calculate the optimal fuel economy and maximize the energy-saving potential of HEBs, an improved DP algorithm is proposed to address limitations of the traditional DP algorithm. Specifically, the significant influence of SOC variations on the cost function and the lack of a theoretical basis for weight coefficient determination. Equivalent fuel consumption is adopted as the single-step cost function, and the secant method is used to iteratively calculate weight coefficients, thereby deriving the optimal set of control variables. To enable online optimal control, the DP optimization data are patterned and analyzed; near-optimal control rules are extracted via outlier detection and graphical methods, which enhances the real-time performance and robustness of the control strategy. To improve the adaptability of the online optimization algorithm across different driving cycles, this paper employs a RVM method for driving cycle recognition. Corresponding control parameters are selected based on the recognition results, and an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm is proposed to optimize the control parameters for each specific cycle.

Improved DP algorithm based on secant method

To explore the maximum energy-saving potential of hybrid powertrains, this paper proposes an improved DP algorithm. The algorithm adopts equivalent fuel consumption as the single-step cost function and employs the secant method to iteratively calculate weight coefficients. This approach addresses the lack of a theoretical basis for weight coefficient determination in the traditional DP algorithm. Based on the cost function and reverse recursion formula, optimal control variables are derived, laying the foundation for the subsequent refinement of control rules.

The objective function for constructing DP problem is:

Where\({L_k}\)represents the cost function for single step state transition; J represents the cumulative cost function; \(x(k)\) represents the state variable at time k, which include the battery SOC and engine speed; \(u(k)\)represents the control variable, which include the engine throttle, the target gear, and the target torque of motor MG1.

The system state variables under the influence of control variables is shown in the formula(9).

In the process of single step optimization, in addition to ensuring minimal fuel consumption, other optimization objectives such as battery SOC balance and minimizing gear shifting operations need to be considered. Therefore, the cost function of single step in traditional algorithms can be expressed as:

Where\({L_{fuel}}\),\({L_{SOC}}\)and\({L_{gs}}\)represent the fuel consumption function, SOC penalty function, and shift penalty function respectively; \(\alpha\)and\(\beta\)represent the weight coefficient of the penalty function; To return the SOC reference value\(SO{C_{ref}}\)quickly, the SOC penalty function is the square term of the SOC change, as shown in formula (11).

According to the Bellman principle, it is necessary to search for optimization under constraint conditions recursively. The constraint conditions are defined based on the engine speed, motor speed, and SOC limits, as shown in formula(12):

After clarifying the constraints, the solution process is completed by reverse recursion, as shown in formula(13) and (14):

Step N:

Step k \((0 \leqslant k<N - 1)\):

Where\(J_{k}^{ * }(x(k))\)represents the optimal cumulative cost function. By solving above recursive formula, the optimal control variable at each moment can be obtained in formula (15).

The weight coefficient in traditional DP algorithm are usually determined through repeated attempts based on experience, which lacks sufficient theoretical basis. The weight coefficient \(1/{K_{eq}}\)in the improved DP algorithm proposed in this paper needs to satisfy the condition of SOC balance:

Newton’s iteration method is usually used to find approximate solutions, the advantage is that the square convergence near the single root of equation\(f(x)=0\), which can quickly determine equation root. However, due to the difficulty in listing the relationship between the SOC change and the equivalent coefficient\({K_{eq}}\), the zero value approximate solution of the f function is considered to be obtained by the secant iteration method. The specific design process is as follows:

Taking\({x_0}=a\),\({x_1}=b\), the equation of the secant passing through function\({P_0}({x_0},f({x_0}))\) and\({P_1}({x_1},f({x_1}))\)is given as:

Two weight coefficients\({K_{eq0}}\)and\({K_{eq1}}\)are solved using DP algorithm to obtain\(\Delta SO{C_0}\)and \(\Delta SO{C_1}\). Applying point\(({K_{eq0}},\Delta SO{C_0})\)and\(({K_{eq1}},\Delta SO{C_1})\)according to Eqs. (5–26), the approximate solution that causes the SOC change to be zero can be obtained, which is also the optimal solution for the hybrid powertrain.

Control rule extraction

Control rules need to be extracted based on the optimal control variables and state data solved by the DP algorithm, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Considering that the engine and motor operate in various states under different working modes, the data is first categorized and then graphically visualized according to working mode identification results. Under a specific working mode, the control of engine and motor speed and torque is also correlated with vehicle speed and required power. The variation patterns of target speed or torque with respect to vehicle speed and required power can be determined via interpolation algorithms, thereby deriving the control rules for engine and motor speed and torque.

System operation in electric mode is primarily constrained by the external characteristics of motor MG2 and the peak battery power. Conversely, the lower boundary for hybrid mode is not inherently restricted and established based on global optimization results. The extraction of mode-switching rules involves analyzing the collective behavior of operating points under the same mode. To conduct group characteristic analysis, it is essential to filter out individual operating points that deviate significantly from the group norm, a process referred to as outlier detection. The practical causes of outliers can be specifically categorized into the three types: noise interference, mode-switching transient state and unusual driving demand.

Firstly, outliers mixed within the current group and exhibiting distinct characteristics can hinder the identification of group features. Secondly, outliers represent discontinuous operating states relative to the dominant mode. Their presence can trigger intermittent switching into certain modes, leading to frequent engine start-stop cycles, which is an issue highly detrimental to fuel efficiency, emissions, and driving performance.

Based on the characteristics of various outlier detection methods, this paper proposes a detection method that combines distance and density:

Firstly, the Euclidean distance between two working points p and o is defined as:

According to the above definition, the reachable distance of working point p relative to working point s in the neighborhood\({N_{k\_dis(p)}}\)is shown in formula(19):

Based on reachable distance, if\({N_{k\_dis(p)}}\)contains n working points, the local reachable density of p is denoted as:

The concept of local outlier factor\(LOF\)is obtained, as shown in formula(21):

Where\(LO{F_n}(s)\)represents the average density of all working points within the neighborhood\({N_{k\_dis(p)}}\)of working point p relative to\(LR{D_n}(p)\). If p belongs to the group, \(LR{D_n}(s)\)and\(LR{D_n}(p)\)at each working point are close to each other,\(LO{F_n}(p)\)is close to 1. Based on LOF, this paper adopts the Chauvenet criterion to achieve preliminary screening of outliers, and obtains the preliminary screening set of outliers\({N_{LOF}}\).

Chauvenet criterion is a statistical approach for outlier screening that finds extensive application in engineering data analysis42. The fundamental principle lies in identifying outliers by assessing whether the deviation of an individual sample from the overall statistical properties of the population surpasses a reasonable threshold. When applied to either univariate or multivariate datasets, the implementation of Chauvenet criterion generally follows two key steps:

-

(1)

Calculate the population statistical indicators: For the target variable set, compute the mean \(\mu\) and standard deviation\(\sigma\)

-

(2)

Determine the outlier threshold: Define samples that satisfy\(\left| {x - \mu } \right|>{k_1}\sigma\)as preliminary outliers, where\({k_1}\)is a dimensionless threshold coefficient. In engineering practice, \({k_1}=2.5\sim 3.0\)is commonly used to balance the accuracy of outlier screening and the retention of valid sample.

Chauvenet criterion serves primarily for the preliminary screening of LOF values. The detailed application procedure is outlined below:

-

(1)

Preprocessing of LOF values: Initially, the LOF value for each operating point is computed using formula (20). These LOF values indicate the extent to which each operating point deviates from the neighboring points.

-

(2)

Statistical analysis via Chauvenet criterion: All LOF values are treated as a statistical population, with the mean\({\mu _{LOF}}\)and standard deviation\({\sigma _{LOF}}\).

-

(3)

Preliminary outlier screening: Operating points whose LOF values meet the condition\(\left| {LOF - {\mu _{LOF}}} \right|>{k_1}{\sigma _{LOF}}\)are categorized into the preliminary outlier set. This step effectively filters out operating points with extreme degrees of deviation while retaining those with mild deviations for subsequent manual review.

Compared with the LOF method which requires traversing all neighborhood points and has high computational complexity, the Chauvenet criterion only relies on statistical indicators for screening, which plays a key preliminary filtering role in outlier detection process.

Once outliers have been identified and removed, the convex hull algorithm can be employed to extract outer envelope points from the remaining operating points. It is crucial to ensure that the lower boundary of the hybrid mode encompasses the minimum torque and vehicle speed requirements. Specifically, when the vehicle speed falls below the minimum speed threshold defined at the lower boundary, or the required torque at the current vehicle speed is less than the torque corresponding to this boundary, the system defaults to electric mode. Conversely, when the required torque exceeds the upper boundary of the electric mode, the system transitions to hybrid mode.

Online adaptive control algorithm

The online adaptive control algorithm proposed in this paper is illustrated in Fig. 4. The overall approach involves using a RVM method for driving cycle recognition. Based on the identified cycle types, corresponding control parameters are selected. Additionally, an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm is proposed to optimize the control parameters for each specific driving cycle.

The specific steps are as follows:

-

Step 1: The operation data under congested, off-peak, and smooth traffic conditions are segmented into cycle blocks by the composite equal division method, and the feature parameters are calculated to obtain the first four principal components to replace the original cycle feature.

-

Step 2: Define the sample set as\(\left\{ {{x_n},{t_n}} \right\}\), where\({x_n}\)is the input variable,\({t_n}\)is the category label, and\(n=1,2, \cdots ,N\)is the sample number. The decision function of the RVM model is as follows:

$$f(x;w)=\sum\limits_{{n=1}}^{N} {{w_n}K(x,{x_n})+{w_0}}$$(22)

Where\({w_n}\)represents the weight vector, \(K( \cdot , \cdot )\) represents the kernel function, and \({w_0}\) represents the bias.

Assuming\(P(t|x)\)follows the 0–1 distribution, applying the logistic sigmoid function to\(y(x)\)

The Gaussian prior probability distribution for the weight vector is defined as:

Step 3: Utilize the Improved Particle Swarm Optimization (IPSO) algorithm to optimize the control parameters of the hybrid urban bus under different cycle, and obtain three sets of optimal control parameters corresponding to congested conditions, off-peak conditions, and smooth traffic conditions. The key difference between the improved particle swarm optimization (IPSO) algorithm proposed in this study and the standard PSO lies in the dynamic adjustment mechanism of the inertia weight. The basic design process is as follows:

First, an initial population is randomly generated, and the initial position and initial velocity of each particle are determined. The fitness function is then calculated to obtain the initial historical position of all particles and the optimal solution position of the population. Subsequently, the velocity and position of each particle are updated according to formula(25):

Where\(V_{i}^{t}\)represents the velocity of the particle at the i-th dimension in the t-th iteration,\(x_{i}^{t}\)denotes the position of the particle at the \(x_{i}^{t}\)-th dimension in the i-th iteration,\(Lbes{t_i}\)stands for the optimal solution position that the current particle has traversed,\(Gbes{t_i}\)is the optimal solution position of the particle swarm itself,\({C_1}\)and\({C_2}\)are learning factors;\({\omega ^t}\) is the inertia weight,\({r_1}\)and\({r_2}\)are random numbers.

As a key parameter of global search and local exploitation in the algorithm, the inertia weight directly determines the convergence speed and optimization capability of the IPSO algorithm. A Sigmod function is used for its calculation, which can effectively overcome the drawbacks of linear inertia weight, such as unchanging decreasing direction and high tendency toward instability. The specific calculation is shown in formula (26). In the early stage of iteration, the inertia weight\({\omega ^t}\)is close to the maximum inertia weight, and the global optimization capability is at its strongest. As the number of iterations increases, the inertia weight\({\omega ^t}\)gradually decreases, and the local optimization capability becomes increasingly prominent. This allows the optimal value to be flexibly adjusted between global search and local optimization:

Where\({\omega _{\hbox{max} }}\)is the maximum inertia weight,\({\omega _{\hbox{min} }}\)is the minimum inertia weight,\({T_I}\)is the maximum number of iterations set by the algorithm,\({a_1}\)and\({b_1}\)are constants for adjusting the shape of the Sigmod function.

-

(3)

Set the loop termination conditions. If the current iteration number exceeds the set maximum iteration number, the computation stop; Otherwise, return to update the velocity and position of each particle.

-

Step 4: Based on the historical vehicle speed data, the composite equal division method is applied to divide the operating vehicle into cycle blocks, extracted the statistical features of the cycle blocks, and calculated the principal components.

-

Step 5: Input the principal components of the current cycle block into the trained RVM model to determine the cycle category to the current block. The cycle judgment result is send to the vehicle controller to update the energy management algorithm in real-time.

A bar chart is used to show the fuel consumption comparison under the four driving cycles(NEW_YORK BUS cycle, Manhattan cycle, CBD BUS cycle, and urban cycle), as shown in Fig. 5. The data directly reflects the ability of the three algorithms to avoid local optima.

The standard PSO exhibits the highest fuel consumption across all driving cycles due to its inherent inability to balance global exploration and local development capabilities. This indicates that it is trapped in local optima for an extended period and fails to explore better parameter combinations. Although the linear PSO achieves lower fuel consumption than the standard PSO, the fuel consumption remains higher than IPSO. This reflects its drawbacks: insufficient global exploration in the early iteration stage and entrapment in local optima in the later stage.

In contrast, the IPSO achieves the lowest fuel consumption in all driving cycles, which proves that through Sigmod function-based weight regulation, it effectively avoids local optima and ultimately approaches the global optimal solution. Furthermore, under the Manhattan cycle, 10 independent optimization experiments were conducted consecutively, and the “fuel consumption variance data of the 10 independent experiments” was calculated. The results show that the variance of the IPSO is 0.12, linear decreasing PSO is 0.35, and standard PSO is 0.58. This further confirms that the IPSO not only avoids local optima but also converges stably near the global optimal solution, with the favorable convergence efficiency, stability, or solution quality.

Results and discussions

Firstly, based on the improved DP algorithm, the optimal energy-saving effect is calculated. The equivalent coefficient of fuel electric conversion under driving cycle is calculated. The lowest fuel consumption of the bus is solved through reverse recursion as shown in Table 1.

Figure 6 shows the variation curve of battery SOC under the entire urban cycle. The SOC remains basically unchanged before and after simulation, with initial and final values of 70%, which indicates that the expected battery SOC is tracked well and maintained power balance.

Figure 7 show the speed and torque curves of the power source and the speed curve of the gear ring throughout the entire time domain. It can be seen that the ring gear speed is approximately proportional to the vehicle speed, and the engine speed is within a reasonable working range. Considering the dual freedom degree of the planetary gear, both the motor MG1 and the motor MG2 achieve effective control of speed and torque.

Figure 8 shows the distribution of engine operating points. The target engine operating point in the efficiency matching of the planetary hybrid system is based on the optimal control algorithm of the engine. However, the operating points are still distributed near the optimal engine operating curve. In addition, after the engine is started, the engine operating point is basically distributed in the high-efficiency and economical operating range, which is conducive to reducing fuel consumption.

Secondly, the control rule extraction results are validated. In Fig. 9, the white grid represents the working area of the hybrid drive mode under the DP algorithm, and the black grid represents the working area of the electric drive mode. When the required power is less than 60 kW, it is mostly distributed in the pure electric drive mode, when the demand power is greater than 10 kW, the system enters the hybrid drive mode. However, the distribution of the working area based on observation is difficult to directly apply to the control strategy.

It is necessary to extract the switching curve between pure electric drive and hybrid drive modes based on the control rule extraction method in Fig. 3, as shown in Fig. 9. The blue curve represents the boundary condition for switching from electric drive mode to hybrid drive mode, and the red curve represents the boundary condition for switching from hybrid drive mode to electric drive mode. The boundary curves can be embedded into the logical threshold strategy to achieve an approximate optimal control effect.

Considering the two-degree-freedom characteristics of the planetary system, the control rules for engine speed and torque are refined according to the method shown in Fig. 3, as illustrated in Fig. 10.

Based on the control characteristics of the planetary hybrid system, it is necessary to control the engine speed based on power demand and vehicle speed, and then control the engine torque to achieve power output. The engine torque is determined by the engine speed, the MG1 motor speed, and the total vehicle power demand.

Next, in order to verify the adaptability of the proposed strategy, a mixed driving cycle was constructed to simulate and test different control strategies. The cycle consists of three different driving conditions, including NEW_YORK BUS cycle(driving cycle1), Manhattan cycle(driving cycle2), and CBD BUS cycle(driving cycle3). The identification result is shown in Fig. 11. It can be seen that the cycle identification algorithm can automatically select the standard cycle number that is closest to the input characteristic parameter value as the output, and has a favorable identification effect.

Finally, real-world driving cycle data were used to verify the generalization ability of the proposed algorithm, with a total time duration of 800 s. Figure 12 presents the variation curve of battery SOC throughout the entire cycle. During the entire simulation, the SOC remained within a reasonable fluctuation range. This result not only demonstrates the algorithm excellent performance in tracking and controlling the battery SOC but also confirms that it can effectively maintain the vehicle energy balance under real-world operating conditions, thereby verifying the method adaptability to different operating conditions and generalization ability.

Figure 13 shows the speed and torque curves of the power sources (engine, MG1, and MG2) as well as the speed curve of the ring gear over the entire time domain. It can be clearly observed from the figure that the engine speed remained stable within the high-efficiency operating range throughout the process, with no instances of exceeding the upper limit or operating at low efficiency. Considering the dual-degree-of-freedom characteristic of the planetary gear mechanism, both MG1 and MG2 motors achieved precise control of speed and torque according to the demands of the operating conditions, with no significant fluctuations or control delays. From the perspective of coordinated control of power sources, this further confirms stable control performance and generalization ability of proposed algorithm under complex operating conditions.

Table 2 shows the optimization results of urban cycle under DP control, logic threshold control (without control parameter optimization), and proposed control (adaptive control algorithm in this paper). Compared with the DP control strategy, the fuel economy under logic threshold control and proposed control strategy increased by 14.6% and 3.2%, respectively. Tables 3 and 4 Shows the optimization results of mixed cycle and real-world cycle under DP control, logic threshold control, and proposed control. Compared with the DP control strategy, the fuel economy under logic threshold control and proposed control strategy increased by 13.8% and 2.9% under mixed cycle, 15.2% and 3.5% under mixed cycle, respectively. It can be seen that the proposed algorithm can achieve approximately optimal energy-saving effect and demonstrate strong generalization ability.

In order to further verify the real-time performance of the control strategy proposed in this paper, hardware in the loop (HIL) experiment is carried out. Real controller is applied to verify control functions and fuel efficiency in real-time environment. A HIL test platform is built, as shown in Fig. 14, which mainly includes dSPACE/Simulator, rapid prototyping controller, and host computer. dSPACE/Simulator communicates in real-time with the rapid prototyping controller via CAN network, and the host computer software is used to create a visual interface for real-time data observation and parameter adjustment.

The comparison between offline simulation and HIL test results under urban cycle is shown in Table 5. The fuel economy and average fuel consumption rate are basically the same, and the battery can achieve SOC balance, which proves that the designed adaptive optimization algorithm based on improved dynamic programming and control rule extraction has good real-time performance.

Conclusions

This paper proposes a real-time adaptive EMS based on improved DP algorithm and control rule extraction for power-split HEB. The improved DP algorithm was selected for offline global optimization in order to minimize the overall fuel consumption, the equivalent fuel consumption is taken as the single step cost function, and the secant method is used to calculate the weight coefficients. In order to improve the real-time performance of the algorithm, the data of DP algorithm is patterned and identified, and the optimal control rules are extracted through outlier detection and graphical method. Besides, this paper uses RVM for working condition recognition by selecting different control parameters, and propose an improved particle swarm optimization algorithm for optimizing the control parameters of each cycle.

The algorithm performance is verified based on simulation platform and HIL experiment platform. The results show that improved DP under the urban cycle can obtain the approximate optimal control effect to DP results, with oil saving 14.6% compared with logic threshold control. In addition, the algorithm can effectively extract control rules based on the working status of the power source, and perform effective condition recognition, thereby achieving energy-saving optimization effects similar to the DP algorithm. And the HIL simulation test shows that the proposed optimal control strategy has good real-time performance.

The control algorithm proposed in this paper utilize operating condition information to achieve approximate online global optimization of energy-saving algorithms, and maximize energy-saving potential. Besides, the method provides an reference to solve the calibration problem for power-split HEB, which give full play to the fuel economy potential in various driving cycles. Future work will focus on verifying the algorithm via real-vehicle test under complex real-world cycles and exploring the extension to multi-energy hybrid systems.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Varga, B., Doba, D. & Tettamanti, T. Optimizing vehicle dynamics co-simulation performance by introducing mesoscopic traffic simulation[J]. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory. 125, 102739 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Hierarchical speed planning and energy management for autonomous plug-in hybrid electric vehicle in vehicle-following environment[J]. Energy 260, 125212 (2022).

Yang, W. et al. Investigation of integrated uninterrupted dual input transmission and hybrid energy storage system for electric vehicles[J]. Appl. Energy. 262, 114446 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Comparison of power-split and parallel hybrid powertrain architectures with a single electric machine: dynamic programming approach[J]. Appl. Energy. 168, 683–690 (2016).

Hong, S. et al. Mode shift control for a dual-mode power-split-type hybrid electric vehicle[J]. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers Part D Journal of Automobile Engineering, 228(10): 1217–1231. (2014).

Dong, P. et al. Practical application of energy management strategy for hybrid electric vehicles based on intelligent and connected technologies: development stages, challenges, and future trends[J]. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 170, 112947 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. A survey on key techniques and development perspectives of equivalent consumption minimisation strategy for hybrid electric vehicles[J]. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 151, 111607 (2021).

Fan, L. et al. A GA-based online real-time optimized energy management strategy for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles[J]. Energy 241, 122811 (2022).

Pan, X., Chen, B. & Evangelou, S. Optimal Vehicle Following Strategy for Joint Velocity and Energy Management Control of Series Hybrid Electric Vehicles[J] Vol. 53, 14161–14166 (IFAC-PapersOnLine, 2020). 2.

Gong, Q., Li, Y. & Peng, Z. Trip-based optimal power management of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles[J]. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 57 (6), 3393–3401 (2018).

Peng, J., He, H. & Xiong, R. Rule based energy management strategy for a series-parallel plug-in hybrid electric bus optimized by dynamic programming[J]. Appl. Energy. 185, 1633–1643 (2017).

Goos, J., Criens, C. & Witters, M. Automatic Evaluation and Optimization of Generic Hybrid Vehicle Topologies Using Dynamic Programming[C]// (IFAC World Congress, 2017).

Martinez, C. et al. Energy management in plug-in hybrid electric vehicles: recent progress and a connected vehicles perspective[J]. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 66 (6), 4534–4549 (2016).

Lian, R. et al. Rule-interposing deep reinforcement learning based energy management strategy for p ower-split hybrid electric vehicle[J]. Energy 197, 117297 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. An optimal control strategy for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles based on enhanced model predictive control with efficient numerical method[J]. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification. 8 (2), 2516–2530 (2022).

Larsson, V., Johannesson, L. & Egardt, B. Cubic spline approximations of the dynamic programming cost-to-go in HEV energy management problems[C]. 2014 European Control Conference (ECC). Strasbourg, France, 1699–1704. (2014).

He, Y. et al. An energy optimization strategy for power-split drivetrain plug-in hybrid electric vehicles[J]. Transp. Res. Part C. 22 (5), 29–41 (2022).

Borhan, H. et al. MPC-Based energy management of a power-split hybrid electric vehicle[J]. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 20 (3), 593–603 (2022).

Lian, J. et al. A mixed logical dynamical-model predictive control (MLD-MPC) energy management control strategy for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs)[J]. Energies 10 (1), 74–85 (2017).

Wu, Y. et al. Deep reinforcement learning of energy management with continuous control strategy and traffic information for a series parallel plug-in hybrid electric bus[J]. Appl. Energy. 247, 454–466 (2019).

Wang, H., Wang, X. & Fu, Z. Energy management strategy for optimal charge depletion of plug-in FCHEV based on multiconstrained deep reinforcement learning[J]. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification. 11 (1), 1077–1090 (2025).

Zare, A. & Boroushaki, M. A knowledge-assisted deep reinforcement learning approach for energy management in hybrid electric vehicles[J]. Energy, 2024: 134113. (2024).

Jia, C. et al. Deep reinforcement learning-based energy management strategy for fuel cell buses integrating future road information and cabin comfort control[J]. Energy. Conv. Manag. 12, 119032 (2024).

Li, P., Jiao, X. & Li, Y. Adaptive real-time energy management control strategy based on fuzzy inference system for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles[J]. Control Eng. Pract. 107, 104703 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Driving pattern prediction model for hybrid electric buses based on real-world driving data[C]. International Electric Vehicle Symposium and Exhibition, KINTEX, Korea, 1–9. (2015).

Chen, Z. et al. An on-line predictive energy management strategy for plug-in hybrid electric vehicles to counter the uncertain prediction of the driving cycle[J]. Appl. Energy. 185, 1663–1672 (2017).

Zhang, S. & Xiong, R. Adaptive energy management of a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle based on driving pattern recognition and dynamic programming[J]. Appl. Energy. 155, 68–78 (2015).

Chen, B., Wuy, Y. & Tsaih, C. Design and analysis of power management strategy for range extended electric vehicle using dynamic programming[J]. Appl. Energy. 113, 1764–1774 (2014).

Kum, D., Peng, H. & Bucknor, N. Supervisory control of parallel hybrid electric vehicles for fuel and emission reduction[J]. J. Dynamic Syst. Meas. Control. 133 (6), 061010 (2011).

Zhou, Y., Ravey, A. & Péra, M. A survey on driving prediction techniques for predictive energy management of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles[J]. J. Power Sources. 412, 480–495 (2019).

Wang, Y., Zeng, X. & Song, D. Hierarchical optimal intelligent energy management strategy for a power-split hybrid electric bus based on driving information[J]. Energy 199, 117499 (2020).

Liu, T. et al. Driving conditions-driven energy management strategies for hybrid electric vehicles: A review[J]. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 151, 111521 (2021).

Chen, Z. et al. Multimode energy management for plug-in hybrid electric buses based on driving cycles prediction[J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 17 (10), 2811–2821 (2016).

Wang, X. et al. Application study on the dynamic programming algorithm for energy management of plug-in hybrid electric vehicles[J]. Energies 8 (4), 322544 (2015).

Xu, Y. et al. Joint energy management and eco-routing for electric vehicles with hybrid energy storage systems[C]//2023 4th Information Communication Conference, Nanjing, China,: 374–378. (2023).

Wang, W. et al. A multi-objective optimization energy management strategy for power split HEV based on velocity prediction[J].Energy, 238: 121714. (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Synthesis of Representative Driving Cycle for Heavy Duty Vehicle Based on Markov Chain and Big Data Considering Weight variation[J] (SAE report, 2023). 2023-32-0177.

Li, Y. et al. Energy management for a power-split hybrid electric bus via deep reinforcement learning with terrain information[J]. Appl. Energy. 255, 1–13 (2019).

Wang, H. & Wang, X. Energy management of intelligent FCHEVs under adaptive cruise control based on multi-objective deep reinforcement learning[J]. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 74 (5), 1–12 (2025).

Mahler, G. & Vahidi, A. An optimal velocity-planning scheme for vehicle energy efficiency through probabilistic prediction of traffic-signal timing[J]. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 1 (5(6), 2516–2523 (2014).

Xu, Q. et al. Research on double fuzzy control strategy for parallel hybrid electric vehicle based on GA and DP optimization[J]. IET Electr. Syst. Transport. 8 (2), 144–151 (2018).

Ni, W. et al. A Pulse Signal Preprocessing Method Based on the Chauvenet criterion[J] Vol. 2019, 1–9 (Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, 2019). 9.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the 2025 Key Scientific Research Projects of Higher Education Institutions in Henan Province (25A630025).We also thank the anonymous reviewers for providing critical comments and suggestions that improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Methodology, Z.R. and T.L.; software, Z.R. ; validation, Z.R. and T.L.; investigation, Z.R. and T.L.; resources, Z.R. and T.L.; writing-original draft preparation, Z.R.; writing-review and editing, and T.L.; supervision, T.L.; project administration, Z.R. and T.L. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, R., Tang, L. Research on energy-saving adaptive optimization of hybrid electric vehicle based on improved dynamic programming and control rule extraction. Sci Rep 15, 41564 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25431-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25431-4