Abstract

Synovitis, driven by fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS), is a key early event in knee osteoarthritis (KOA). The lack of standardized protocols for FLS culture and molecular analysis hinders reproducible in vitro modeling of early KOA. We developed an integrated platform combining MIA-induced KOA pain modeling, standardized primary FLS culture, inflammation induction, and molecular analysis. We defined passages 3–7 (P3–P7) as the optimal functional passage window for FLS, during which FLS maintained > 98% purity and stable proliferation. LPS stimulation at 1000 ng/mL for 3 h robustly induced IL-1β and TNF-α expression at both mRNA and protein levels. Our optimized RT-qPCR protocols achieved high efficiency (> 91%) and linearity (r > 0.95). Using dexamethasone (DEX), we validated the platform by demonstrating suppression of NF-κB signaling and downstream inflammatory mediators (MMP3/13, VEGFA, NGF). This work provides a standardized system addressing major reproducibility challenges in FLS research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Synovitis, predominantly mediated by fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS), is a pivotal early event in KOA, contributing to pain and disease progression before overt cartilage degradation occurs1,2,3,4. Activated FLS secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α), matrix-degrading enzymes (e.g., MMP3/13), and neurotrophic factors (e.g., NGF)5,6,7. A critical feedback loop exists where cytokines like IL-1β and TNF-α stimulate NGF release from FLS, which in turn can amplify TNF-α production8. This process enhances pain nerve sensitivity, contributing directly to joint pain and disability. Targeting FLS in early KOA is therefore a promising therapeutic strategy6,8.

However, translational research is critically hampered by the lack of standardized protocols for primary FLS culture and molecular characterization. Current methods suffer from rapid phenotypic drift beyond early passages, inconsistent responses to inflammatory stimuli, and unoptimized workflows for molecular analyses (e.g., Western blot [WB], RT-qPCR), leading to significant inter-study variability and hindering reproducibility9,10,11,12. This lack of standardization hampers reliable investigation of early synovitis mechanisms and robust screening of FLS-targeted therapies. Although previous studies established foundational FLS methods9,13, they lacked comprehensive standardization, resulting in inherent variability. For instance, our prior work9 successfully developed a primary FLS culture model but did not rigorously define a stable in vitro passage window, a critical factor for experimental consistency. Similarly, although study13 utilized FLS for pharmacological investigation (e.g., Ski protein effects), the inflammatory induction protocol (LPS at 1 μg/mL for 3 h) and molecular assay conditions were adopted based on common practices without systematic optimization for maximal and reproducible response. A unified platform integrating in vivo modeling, standardized culture, optimized inflammation induction, and validated molecular assays was absent.

To address these gaps, we developed an integrated platform with three key advancements: 1) defining passages P3–P7 as the stable functional passage window for FLS; 2) optimizing LPS stimulation to 1000 ng/mL for 3 h for maximal, reproducible cytokine induction; and 3) implementing rigorously validated WB and RT-qPCR workflows with high efficiency and linearity. The MIA model was selected for its robust induction of early synovitis and pain behaviors relevant to KOA14,15. We demonstrate the utility of this platform by investigating the effects of dexamethasone on NF-κB signaling and inflammatory mediators in FLS.

Materials and methods

Experimental animals

Four-week-old, specific pathogen-free, male Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats weighing 80 to 120 g were provided by the Laboratory Animal Center of the Army Characteristic Medical Center, Army Medical University (Chongqing, China). The animal-feeding room was used as a standard laboratory. The room had a 12:12 h light–dark cycle, constant temperature of 22 ± 2 °C, and humidity of 55 ± 10%. All procedures complied with ARRIVE guidelines and were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Army Medical University (Protocol AMUWEC20181430). Humane care followed NIH guidelines and the 3R principle.

Experimental design of living animals

The KOA pain model was induced using monosodium iodoacetate (MIA)16,17. This study adopted simple (or complete) randomization for grouping. Rats were randomly assigned to sham operation (sham) or model (KOA) groups (n = 35 per group). In the KOA group, KOA was induced using a single knee joint cavity injection of MIA (2 mg/knee)13. On day 0, the rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium. Fifty microliters of saline containing 2 mg MIA (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were injected into the articular cavity through the infrapatellar ligament of the right knee joint in the KOA group. Fifty microliters of sterile saline without MIA were injected into each rat in the sham group. The rats were anesthetized and euthanized on day 0 within 1 h after MIA or saline injection (n = 10 per group), day 7 (n = 10 per group), and day 14 (n = 15 per group). Rats were anesthetized with 80 mg/kg pentobarbital sodium (i.p.) and euthanized following American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines, cartilage and synovial tissue were harvested and stored in a freezer at -80℃. Synovial tissue from five animals on day 14 was used for primary culture. The sample size was determined based on previous experience with the MIA model and similar studies9,17, which indicated that this number (n = 35 per group) provides adequate statistical power for detecting significant differences in the measured outcomes.

Weight-bearing capacity

Weight-bearing capacity is an important index for determining joint discomfort and pain in KOA rats17. On days 0, 3, 7, 10, and 14 after MIA injection, the strength of the right hind limb of KOA rats was assessed by measuring the hind paw weight distribution using a disability tester (Norford Clinton Instruments, UK). Percentage of weight distributed on the right hind limb was calculated as weight-bearing rate (%) = (right hind limb weight/left hind limb weight + right hind limb weight) × 100%.

Knee joint diameter

Joint swelling is one of the important indicators for determining joint discomfort and pain in KOA Rats14. After the MIA was injected into the articular cavity of the rat knee, the horizontal distance between the right knee laterals was measured on days 0, 3, 7, 10, and 14 with vernier calipers at 90° knee bend. Each knee was measured three times and the average value was calculated.

Acquisition and isolation of synovial tissue, and primary culture of FLS

After 14 days, rats in the sham and KOA groups (n = 5 per group) were anesthetized via intraperitoneal injection of 1.5% pentobarbital sodium at a dose of 2 mL/kg body weight. The animals were then immersed in 75% ethanol for 10 to 20 min in the isolation room of the cell culture chamber. The right posterior knee joint was surgically excised from both sham and KOA rats. The hair and blood of the knee joint were sequentially washed with tap water, 75% ethanol, and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin three times for 1 to 2 min each time. Each washed knee joint was transferred to a PBS plate containing 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin on an ultra-clean bench for synovial tissue separation using an ice bath, sterile conditions, PBS soaking, and sharpness separation.

The isolated synovial tissue was cut into a 1 × 1 × 1 mm block, transferred to a 10 ml sterile centrifuge tube, and centrifuged at 1 500 × g for 1 min. The sediment containing synovial tissue was resuspended in 2 to 3 mL of 0.2% (w/v) type I collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and transferred to a 25 cm2 culture bottle. Each bottle was gently shaken by hand to evenly distribute the synovial tissue at the bottom of the bottle. The evenly distributed synovial tissue was digested at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 for 4 to 6 h. After the synovial tissue adopted a cotton wool-like consistency, digestion was stopped by the addition of 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). To minimize serum-induced variability, a single batch of FBS was screened and used for all experiments. Following centrifugation at 1 500 × g for 1 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate was resuspended and washed once using a complete medium and transferred to a 25 cm2 culture bottle. The volume was maintained at 2 to 3 mL with complete medium, and the culture bottle was gently shaken to evenly distribute the synovial tissue at the bottom of the bottle. The cultures were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and cell motility was observed daily. The motility of spindle cells was evident the next day. The fluid was changed every 2 to 3 days.

Passage of primary culture synovial cells

When the fusion of primary cells reached 70 to 80%, the medium was aspirated, and 0.25% pancreatic enzyme in disodium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) was added to digest adherent cells. During trypsin digestion, the culture flask was gently shaken by hand to ensure that the digestive solution covered the bottom of the flask, and periodically tapped to aid digestion. Inverted microscopy examination revealed that the cell space increased and the cells shrank, became round, and suspended. Digestion was terminated by the addition of 10% FBS. The cells were transferred to a centrifuge tube, centrifuged at 1 500 × g for 1 min, washed once and thoroughly resuspended in a complete medium with a cell-to-medium ratio of 1:2–3, and transferred to 2–3 new aseptic culture flasks.

Immunofluorescence histochemical staining

Histochemistry examination by immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously described9. Briefly, synovial cells passaged three times were adjusted to 4 × 104/mL, and 0.2 mL aliquots were seeded in wells of MillicellR Ezislidea 8-Well glass slides (Merck Millipore Ltd., Germany) and incubated for 24 h. The cells were fixed by the addition of 300 μL of 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, followed by two to three washes with PBS. After permeation with 0.2%Triton X-100 at 37℃ for 20 min, a mouse anti-vimentin antibody (1:200, Cat. no. ab8978, Abcam) was added to each well and incubated overnight at 4℃ in a wet box. Fluorescent 488 conjugated anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (1:500) was added and incubated at 37℃ for 1 h in the dark. Cell nuclei were stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) at 37℃ for 15 min, and the plates were sealed in the presence of an anti-fluorescence quencher. Fluorescence microscopy was used to observe and photograph the samples. The purity of FLS was determined based on vimentin staining in synovial cells and was observed by two observers who were unaware of the the experimental groups using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica SP8, Mannheim, Germany), and normalized to the total number of cells stained with DAPI.

Detection of proliferation of FLS

FLS cell proliferation was determined as previously described 13 using 5-ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine (EdU). A Cell-Light Apollo 567 In Vitro Kit (Ribobio Co., Ltd., China) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the cell ratio of synovial cells passaged seven and eight times was adjusted to 4 × 104/mL, and 0.2 mL aliquots of the final suspension were seeded in wells of a MillicellR Ezislide 8-Well glass slide and cultured for 24 h, followed by incubation with 50 μM EdU (1:1000) for 12 h. FLS were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 20 min at 37 °C, followed by permeabilization in 0.5% Triton X-100 at 37 °C. One hundred microliters of Apollo® reaction cocktail was added to each well and incubated for 30 min under light-shading conditions. After three washes with PBS, DNA was stained with 100 μL of 1 × Hoechst 33,342 for 25 min at 37 °C in darkness and washed two to three times with PBS. Each glass slide was sealed in the presence of an anti-fluorescence quencher. The results were acquired using a laser scanning confocal microscope (TCS-SP8, Leica), and the EdU-labeled FLS were independently assessed by two blinded observers for quantitative analysis, without knowledge of the experimental groups and treatment conditions.

In vitro inflammatory response of LPS-induced FLS

KOA FLS at passage 3 (> 98% pure) were used. The cell number was adjusted to 4 × 104/mL for the experiment. The cells were inoculated in wells (0.2 mL/well) of MillicellR Ezislide 8-Well glass slides. After 12 h of culture at 37 °C, LPS (Cat. no. 60748ES08, YEASEN) was added to the cells at final concentrations of 500, 1000, and 2000 ng/mL. At 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h, LPS-induced FLS were digested with 0.25% trypsin for 2–5 min (n = 70 wells per time point), and the digestion was terminated by the addition of 10% FBS. The cells were collected and stored at − 80℃ for future use.

DEX treatment of FLS and LPS-stimulated FLS in vitro

Synovial inflammation is the main event in the comprehensive pathological changes in OA of the whole joint8. Hence, we investigated the anti-inflammatory effects of targeting FLS in vitro and examined the correlation between FLS and analgesia. The third passage normal and KOA FLS of SD rats (cell purity > 98%) were used. The cell number was adjusted to 4 × 104/mL, and aliquots of 0.2 mL were added to wells of MillicellR Ezislide 8-Well glass slides and cultured for 12 h. The cells were divided into six groups (n = 5 wells/group): no MIA or DEX (MIA − and DEX −); MIA and no DEX (MIA + and DEX −); both MIA and DEX (MIA + and DEX +); both MIA and LPS (MIA + and LPS +); MIA, LPS, and normal saline (MIA + and LPS + and NS +); and MIA, LPS, and DEX (MIA + and LPS + and DEX +). LPS stimulation was accomplished using 1 μg/mL LPS for 3 h. DEX(Cat. no. D4902, Sigma-Aldrich) concentration was 10 μM. All FLS were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, followed by digestion with 0.25% trypsin for 2 to 5 min. Digestion was terminated by the addition of 10% FBS. The FLS were collected and stored at − 80℃ until used for the analysis of protein expression.

Western blot

Cartilage, synovial tissue, and FLS were recovered from the − 80 °C storage and ground using a mortar filled with liquid nitrogen. The samples were treated with tissue lysates containing protease inhibitors and centrifuged at 13 000 × g for 15 min to extract total protein. The total protein concentration was determined using the standard Coomassie brilliant blue assay to normalize the total protein concentration of each sample. Equal amounts of tissue and cell extracts were mixed with sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer and each sample of 30 μg was used for 11% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) using distilled water, 2.18 mL; 3.0 mol/L Tris, 1.5 mL; 30% acrylamide-bis (29.2:0.8), 2.2 mL; 10% SDS, 0.12 mL; 10% ammonium persulfate, 60 μL; and N, N, N′, N′-tetramethylethylenediamine, 5 μL. The resolved proteins were transferred to 0.45 μm nitrocellulose membranes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The membranes were blocked with PBS containing 6% skim milk powder for 3 h at 22 ± 2 °C, then hybridized at 4℃ overnight with primary antibodies against IL-1β (Cat. no. #5204, CST, USA), TNF-α (Cat. no. #3707, CST); IL-4 (Cat. no. ab9811, Abcam), IL-6 (Cat. no. ab9324, Abcam), osteopontin (OPN; Cat. no. ab307994, Abcam), NGF (Cat. no. ab6199, Abcam), matrix metalloproteinase 3 (MMP3 (Cat. no. ab52915, Abcam), MMP13 (Cat. no. ab39012, Abcam), proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA; Cat. no. ab18197, Abcam), p-NF-κB p65 (Cat. no. sc-101752, Santa Cruz), IκBα (Cat. no. sc-371, Santa Cruz), vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA; Cat. no. ab1316, Abcam), and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated β-actin (Cat. no. ab49900, Abcam. Each membrane was then washed with 0.01 mol/L PBS (pH 7.2), and the corresponding HRP-labeled IgG antibody (1:10,000) was added and incubated for 40 to 50 min. The binding of the primary antibody was visualized using the ECL method. To quantify the relative expression levels of the target protein, two independent observers, who were blinded to the experimental groups and treatment conditions, analyzed the Western blot images using the Labwork 4.6 image analysis software (Labwork, USA). The expression intensities of the different proteins were statistically compared.

RT-qPCR

Total RNA was extracted from the collected synovial tissues and FLS using TRIzol™ reagent (Invitrogen). The integrity and purity of total RNA were verified by 0.8% formaldehyde agarose gel electrophoresis and the 260/280 nm absorbance ratio. Total RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a reverse transcription kit (Promega, USA). The selected PCR annealing temperature was optimized using a gradient PCR instrument (Bio-Rad, USA). The linear relationship between cycle threshold (Ct ) values and the gradient of cDNA concentration was studied with 1 ug/uL FLS cDNA diluted in multiple proportions. After optimization, IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA expression were analyzed; five replicates were used for each analysis. The PCR reaction system comprises 2 × master mix, 10 μL; DNase/RNase-free water, 7 uL; primer 0.5 μL; and cDNA, 2 μL. The PCR conditions were denaturation at 95℃ for 10 s, and 40 cycles of PCR-optimized annealing temperature or 15 s annealing. The melt cure was observed at 55.0 to 95.0 °C. The primer sequence was determined according to the literature18 and compared with the rat gene sequence through the Primer Blast of NCBI. The sequence was identical. IL-1β mRNA (Forward: 5′-CCTTGTGCAAGTGTCTGAAG-3′, Reverse: 5′- GGGCTTGGAAGCAATCCTTA-3′); TNF-α mRNA: (Forward: 5′-CAAGGAGGAGAAGTTCCCA-3′, Reverse:5′-TTGGTGGTTTGCTACGACG-3′); GAPDH mRNA (Forward: 5′- TCTTCCAGGAGCGAGATCCC-3′, Reverse: 5′-TTCAGGTGAGCCCCAGCCTT-3′).

Statistical analyses

Western blot results are expressed as relative optical density. Fluorescence qRT-PCR data are expressed as 2−ΔΔCt. Experimental data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. For comparisons among more than two groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons. For pairwise comparisons, the Student t test was chosen for those satisfying equal variances, while the Welch t test was chosen for those with unequal variances. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., USA) and Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Full, uncropped blot images are provided in Supplementary Fig. S1–S5.

Results

Validation of early synovitis in MIA-induced KOA pain model rats

MIA injection successfully induced early KOA pathology, as confirmed by molecular and phenotypic changes characteristic of synovitis. At days 7 and 14, synovial tissue and chondrocytes exhibited significant upregulation of osteoarthritis-associated markers: OPN (synovium at day 14: 4.2-fold increase, P < 0.001); cartilage: 4.9-fold increase, P < 0.001 vs. sham), a synovitis biomarker19; MMP13 (synovium at days 14: 2.4-fold increase; cartilage: 2.2-fold increase, both P < 0.001), a cartilage-degrading enzyme20; NGF (synovium: 4.7-fold increase; cartilage: 3.6-fold increase, both P < 0.01), a pain sensitizer8,13 (Fig. 1A-B). These molecular alterations correlated with established clinical hallmarks of early KOA: progressive joint swelling (transverse diameter increase: 28.3 ± 3.1% at day 14, P < 0.01; Fig. 1C) and impaired weight-bearing capacity (right hindlimb: 23.5 ± 2.1% vs. sham 49.8 ± 3.4%, P < 0.01; Fig. 1D). This integrated molecular-phenotypic profile confirms MIA effectively induces synovitis-driven early KOA pain in rats, sharing features with human disease progression8,13.

MIA-induced early synovitis and functional impairment in rat knees. (A) Representative Western blots and quantification of OPN, MMP13, and NGF in synovium. (B) Protein expression in chondrocytes. Data normalized to sham (dashed line). (C) Progressive joint swelling shown by transverse knee diameter at 90° flexion. (D) Impaired weight-bearing capacity of the ipsilateral hindlimb. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 5 biological replicates; ** P < 0.01 vs. sham.

Establishment of a standardized primary fibroblast-like synoviocytes (FLS) culture system

Having validated the MIA-induced synovitis model, we next established a standardized primary FLS culture system from the synovial tissues. Isolated primary FLS from KOA synovium exhibited characteristic spindle morphology (Fig. 2A–C), with vimentin immunofluorescence confirming > 98% purity at passage 3 (Fig. 2E–G). Proliferative capacity remained stable through P7, evidenced by EdU + staining (Fig. 2I–Q) and consistent proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) expression (P < 0.01 for P8 decline, Fig. 2R–S). Statistical trend analysis revealed a significant decrease in PCNA expression starting at P8 (P < 0.01 compared to P7), confirming P7 as the upper limit of stable proliferation. Beyond P7, cells exhibited morphological alterations (e.g., a shift to an oval shape, vacuolation; Fig. 2D) suggestive of potential cellular senescence. EdU proliferation assay on the 8th passage of primary cultured synovial cells showed that the FLS had lost their proliferation ability (Fig. 2O–Q). Thus, P3–P7 was defined as the optimal functional passage window for reproducible experiments.

Primary culture, purity and proliferation of FLS in knee joints of SD rats. (A) Synovial cell culture day 1 (× 10, ruler = 25 μm). (B) Synovial cell culture day 6 before the first generation of passage (× 10, ruler = 25 μm). (C) Synovial cell culture to the third generation (× 10, ruler = 25 μm). (D) Synovial cell culture to the eighth generation (× 10, ruler = 25 μm). (E–G) Synovial cells were cultured to the third generation of Vimentin fluorescence chemical identification (× 40, ruler = 25 μm) (E: Vimentin, green; F: DAPI, blue; G: Merge). (I-N) EdU proliferation assay of 7th generation synovial cells (× 10, ruler = 50 μm) (I) Proliferating cells (red); (M) DNA staining (blue); (N) Merged image. (O-Q) EdU proliferation assay of 8th generation synovial cells (× 10, ruler = 50 μm). (O) Proliferating cells (red); (P) DNA staining (blue); (Q) Merged image. (R) WB results of synovial tissue and proliferating cell nuclear antigen protein (PCNA) from the 3rd to 8th generations of primary culture FLS. (S) Relative content of PCNA protein in each group. Compared with the 3rd generation, ** P < 0.01. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 5 biological replicates.

Optimization of molecular assays for pro-inflammatory cytokines

With the optimized FLS culture system in place, we proceeded to standardize molecular assays for pro-inflammatory cytokine detection. Critical parameters for WB and RT-qPCR were rigorously standardized: WB: Coomassie staining confirmed equal protein loading (Fig. 3A) and complete transfer (Fig. 3B); β-actin uniformity validated technical consistency (Fig. 3C). RT-qPCR: RNA integrity (260/280 nm ratio: 1.8–2.0; Fig. 3F) and optimized annealing temperature (59.0 °C) eliminated non-specific amplification (Fig. 3G–I). Amplification efficiency exceeded 91% (r > 0.95), ensuring linear quantification (Fig. 3J–L). Expressions of IL-1β and TNF-α protein and mRNA: Using these protocols, KOA-FLS showed significant elevation of IL-1β and TNF-α vs. sham (P < 0.01; WB: Fig. 3D–E; RT-qPCR: Fig. 3N).

Optimization of conditions for detecting pro-inflammatory factors at the molecular level (A) Coomassie-stained gel confirming equal protein loading. (B) Post-transfer gel validation of complete protein transfer. (C) Uniform β-actin expression confirming technical consistency. (D) Representative blots of IL-1β and TNF-α in synovial tissue (ST) and FLS. (E) Quantitative analysis showing elevated IL-1β and TNF-α in KOA groups. (F) Integrity assessment of total RNA by formaldehyde agarose gel electrophoresis. (G-I) Specificity validation at gradient annealing temperatures (58.0–63.0 °C) for: (G) IL-1β, (H) TNF-α, (I) GAPDH. Lane M: DNA marker (100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600 bp); lanes 2–9: annealing temperatures. Arrowheads indicate specific amplicons without primer dimers. (J) Amplification curves for IL-1β. (K) Melting curves confirming specific amplification. (L) Standard curve demonstrating linear quantification (r > 0.95, efficiency > 91%). (M) Agarose gel verification of specific products at optimal annealing temperatures (IL-1β:59.0 °C; TNF-α:59.0 °C; GAPDH:59.9 °C). (N) Elevated IL-1β and TNF-α mRNA in KOA synovial tissue (ST) and FLS. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 5 biological replicates; **P < 0.01 vs. sham.

LPS-induced FLS inflammatory model optimization

Using the validated molecular assays, we next optimized LPS-induced inflammatory stimulation in FLS. FLS stimulated with LPS (500–2000 ng/mL) exhibited time- and dose-dependent upregulation of IL-1β/TNF-α. Maximal response occurred at 1000 ng/mL LPS for 3 h (mRNA: 19.1 ± 5.4-fold for IL-1β, 18.3 ± 3.6-fold for TNF-α; protein: peak at 3 h, F = 28.7–175.0, P < 0.001; Fig. 4A–E). Higher concentrations (2000 ng/mL) accelerated signal decay post-3 h, supporting 1000 ng/mL × 3 h as the standardized inflammatory challenge.

Time- and dose-dependent induction of IL-1β and TNF-α by LPS in FLS. (A) Representative Western blots of IL-1β and TNF-α protein expression. (B, C) Quantitative analysis showing peak expression at 3 h: (B) IL-1β (F = 28.7, P < 0.001), (C) TNF-α (F = 175.0, P < 0.001). (D, E) RT-qPCR analysis of (D) IL-1β and (E) TNF-α mRNA demonstrating maximal induction at 1000 ng/mL for 3 h. Data are presented as mean ± SD of 5 biological replicates; * P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. 0 h; #P < 0.05 vs. 1000 ng/mL at same time point.

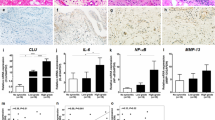

Dexamethasone suppresses FLS-driven inflammation via NF-κB

To demonstrate the pharmacological utility of our optimized platform, we investigated the effects of dexamethasone on LPS-stimulated FLS. In KOA-FLS, MIA and LPS synergistically amplified pro-inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, NGF; P < 0.01; Fig. 5A–B, D–F) while suppressing IL-4 (P < 0.01; Fig. 5A, C). Dexamethasone (DEX) reversed these effects: Inhibited NF-κB pathway activation (p65, IκBα; P < 0.01; Fig. 5G–I); Downregulated downstream effectors: MMP3, MMP13, VEGFA (P < 0.01; Fig. 5G, J–L); Restored IL-4 expression (P < 0.01; Fig. 5C). This confirms FLS as a pharmacologically tractable target in early KOA synovitis.

Dexamethasone modulates inflammatory mediators, the NF-κB signaling pathway, and its downstream effectors. (A) Representative Western blots of indicated proteins. (B-F) Quantitative analysis of: (B) IL-1β, (C) IL-4, (D) IL-6, (E) TNF-α, (F) NGF. (G) Representative Western blots of NF-κB pathway components. (H–L) Quantitative analysis of: (H) p-NF-κB p65, (I) IκBα, (J) MMP3, (K) MMP13, (L) VEGFA. Group designations: 1: MIA- and DEX-; 2: MIA + and DEX-; 3: MIA + and DEX + ; 4: MIA + and LPS + ; 5: MIA + and LPS + and NS + ; 6: MIA + and LPS + and DEX + . Data are presented as mean ± SD of 5 biological replicates; **P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001.

The molecular expression pattern is closely related to the activation status of NF-κB

To gain deeper insights into the coordinated regulation of inflammatory mediators, we performed hierarchical clustering analysis of the protein expression profiles. The protein expression of inflammatory mediators across experimental groups is presented in Fig. 6. Key observations include: 1. LPS-induced inflammation: KOA + LPS group showed pronounced upregulation of IL-1β, TNF-α, and MMPs (rows 1–2, 6–7), correlating with NF-κB activation (red annotation). 2. Dexamethasone effects: KOA + LPS + DEX treatment markedly suppressed pro-inflammatory mediators (blue clusters) and shifted NF-κB status to “Inhibited”. 3. Cluster segregation: Hierarchical clustering identified two molecular subgroups: Cluster A (IL-1β, TNF-α, MMP3, MMP13): LPS-responsive- Cluster B (IL-4, IL-6, NGF): DEX-modulated.

The protein expression profiling of inflammatory mediators and NF-κB activation status in FLS. Heatmap of Z-score normalized expression for 8 mediators (n = 5 samples/group). Columns: experimental groups—C: control; K: KOA; K + D: KOA + DEX; K + L: KOA + LPS; K + L + NS: KOA + LPS + NS; K + L + D: KOA + LPS + DEX. Rows: hierarchical clustering of mediators. Top annotation: group (color-coded) and NF-κB status (red: activated; blue: inhibited). Color scale: expression relative to mean (blue: low; red: high).

Discussion

This study addresses key reproducibility challenges in synovitis research through three interconnected optimizations comprising a standardized platform. First, we rigorously defined passages 3–7 (P3–P7) as the functional passage window for primary FLS cultures, during which cells maintain > 98% vimentin positivity and stable proliferative capacity (EdU⁺ and PCNA expression) (Fig. 2). This resolution of phenotypic drift (the progressive change in cell characteristics with prolonged culture) beyond early passages ensures consistent cellular responses across experiments. Second, we systematically standardized LPS stimulation at 1000 ng/mL for 3 h as the optimal inflammatory challenge, achieving maximal and reproducible induction of pivotal cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α at both mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 4). This precise parameter captures the early NF-κB-driven signaling cascade, directly addressing the inconsistencies in cytokine induction timing reported across previous studies. Third, we implemented and validated robust molecular workflows: Western blot transfer completeness was confirmed by Coomassie staining (Fig. 3B), and RT-qPCR protocols demonstrated high amplification efficiency (> 91%) and excellent linearity (r > 0.95; Fig. 3L). This technical rigor enables the sensitive and accurate quantification of low-abundance mediators (e.g., IL-4, NGF), which was previously hampered by technical variability.

We validated the pharmacological applicability of this platform using DEX. In LPS-stimulated FLS, DEX potently suppressed NF-κB pathway activation, as evidenced by reduced phospho-p65 and restored IκBα levels (Fig. 6A–C). This was concomitantly associated with the downregulation of key pro-inflammatory effectors (IL-1β, TNF-α, MMP3/13, VEGFA; Figs. 5 and 6) and the restoration of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 (Fig. 5C). The observation of this rapid shift from a pro-inflammatory to a pro-resolving state within 3 h underscores the platform’s high sensitivity and its capacity to capture dynamic FLS responses. Hierarchical clustering analysis further affirmed the centrality of NF-κB signaling, identifying a cluster of mediators (IL-1β, TNF-α, MMP3/13) tightly linked to its activation status, while another cluster (IL-4, IL-6, NGF) was predominantly modulated by DEX intervention (Fig. 6).

Our data, derived from a model of KOA pain and synovitis, reinforce the concept that FLS represent an important regulatory target in early KOA synovitis, coordinating the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, matrix degradation, angiogenesis, and pain sensitization largely via the NF-κB pathway. The platform’s ability to model this multifaceted role—particularly the functional link between NF-κB activation, IL-1β/TNF-α production, and the pain mediator NGF—provides a valuable and standardized in vitro system for mechanistic studies of synovitis and joint pain.

By integrating standardized MIA modeling, stable FLS culture within a defined passage window, a controlled inflammatory induction protocol, and validated molecular detection methods, this platform offers a reliable approach for synovitis research. The LPS × 3 h standardization ensures cross-study comparability, which is vital for the validation of therapeutic targets like NF-κB. Future applications should leverage this standardized platform for high-throughput screening of NF-κB inhibitors and biologics (e.g., anti-IL-1β and anti-TNF-α antibodies). This approach will facilitate the disruption of the synovitis-cartilage degradation axis and accelerate the development of FLS-targeted therapies for early osteoarthritis intervention21.

Looking forward, the standardized nature of this platform makes it particularly suitable for translational applications. It provides an ideal in vitro system for the efficient screening of both novel small-molecule NF-κB inhibitors and biologic agents (e.g., anti-IL-1β, anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibodies). By enabling high-throughput and reproducible assessment of drug effects on a critical FLS-driven inflammatory cascade, this platform can significantly contribute to identifying and prioritizing candidate therapeutics for further preclinical and clinical development in osteoarthritis.

Notwithstanding its utility, this study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. Firstly, our pharmacological validation relied solely on dexamethasone. While DEX serves as an excellent proof-of-concept agent, testing a broader range of therapeutics, including NSAIDs and biologic agents (e.g., anti-IL-1β, anti-TNF-α), would significantly broaden the translational relevance of the platform. Secondly, the inflammatory induction is dependent on a single agent, LPS. Future studies could benefit from incorporating other stimuli (e.g., IL-1β, TNF-α, or advanced glycation end products) to better mimic the diverse inflammatory milieu of OA. Furthermore, we cannot fully rule out that the reduced cytokine response observed at higher LPS concentrations (2000 ng/mL) or longer durations may be influenced by early cytotoxic effects; incorporating viability assays in future work would be valuable. Finally, the in vivo component utilizes the MIA model, which is highly valuable for efficacy screening of analgesics and for studying pain-related behaviors and synovitis. However, it does not fully recapitulate the slow, multifaceted structural pathology of human OA. Therefore, findings related to disease modification from this platform should be interpreted with caution and ultimately validated in more physiologically relevant models, such as the surgical DMM model, before clinical translation.

Conclusion

In summary, we developed a standardized FLS research platform featuring three key innovations: defining P3–P7 as the optimal functional passage window, standardizing LPS-induced inflammation (1000 ng/mL, 3 h), and implementing molecular workflows with > 91% efficiency. This system enables physiologically relevant pathophysiological investigation, as demonstrated with dexamethasone testing. Future work should prioritize the screening of NF-κB inhibitors and IL-4 modulators, and also aim to address the limitations of this study, such as its reliance on a single inflammatory inducer (LPS) and validation drug (DEX), which may contribute to accelerating the development of treatments for early KOA.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the Postgraduate Research Innovation Project of Chongqing [Grant No. CYB23292].

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Giorgino, R. et al. Knee osteoarthritis: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and mesenchymal stem cells: What else is new? an update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24(7), 6405 (2023).

Chen, D. et al. Osteoarthritis: toward a comprehensive understanding of pathological mechanism. Bone Res. 5, 160443 (2017).

Kratzer, R. F. & Kreppel, F. Production, purification, and titration of first-generation adenovirus vectors. Methods Mol. Biol. 1654, 377–388 (2017).

Mobasheri, A. et al. The role of metabolism in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 13(5), 302–311 (2017).

Wilczyński, M., Bieniek, M., Krakowski, P. & Karpiński, R. Cemented vs. cementless fixation in primary knee replacement: A narrative review. Mater 17(5), 1136 (2024).

Min, S. et al. Serum levels of the bone tumover marker dickkepf-1, osteoprotegerin, and TNF-α in knee osteoarthritis patients. Clin. Rheumatol. 36(10), 2351–2358 (2017).

Yu, D. S. Effects and mechanism of chondrocyte metabolism in osteoarthritis pathogenesis(D) (Zhejiang University, 2017).

Liao, L. F. et al. Acute synovitis after trauma precedes and is associated with osteoarthritis onset and progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16(6), 970–980 (2020).

Xiong, A. et al. Establishment and characteristic analysis of a model of knee fibroblast-like synoviocytes inlipopolysaccharide-induced Sprague-Dawley rats. Acta Lab. Anim. Sci. Sin. 28(4), 436–446 (2020).

Chen, D., Kim, D. J., Shen, J., Zou, Z. & O’Keefe, R. J. Runx2 plays a central role in osteoarthritis development. J. Orthop. Transl. 23, 132–139 (2020).

Chang, L. H., Chen, C. H., Wu, S. C., Chang, J. K. & Ho, M. L. Cyclooxygenase-2 regulates PTHrP transcription in human articular chondrocytes and is involved in the pathophysiology of osteoarthritis in rats. J. Orthop. Transl. 30, 16–30 (2021).

Chen, D. Osteoarthritis: A complicated joint disease requiring extensive studies with multiple approaches. J. Orthop. Transl. 32, 130 (2022).

Xiong, A., Xiong, R. P. & Luo, F. Ski ameliorates synovial cell inflammation in monosodium iodoacetate-induced knee osteoarthritis. Heliyon 10(2), e24471 (2024).

Lee, D. H., Ju, M. K. & Kim, H. Commiphora extract mixture amelioractes monosodium iodoacetate-induced osteoarthritis. Nutrients 12(5), 1477 (2020).

Oo, W. M. et al. Are OMERACT knee osteoarthritis ultrasound scores associated with pain severity, other symptoms, and radiographic and magnetic resonance imaging findings?. J. Rheumatol. 48(2), 270–278 (2020).

Bianchi, E. et al. Prophylactic role of acetyl-l-carnitine on knee lesions and associated pain in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Life Sci. 106(1–2), 32–39 (2014).

Dal, L. H. et al. Silencing of miR-101 prevents cartilage degradation by regulating extracellular matrixrelated genes in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Mol. Ther. 23(8), 1331–1340 (2015).

Brown, K. T. et al. Innate immune signaling in the ventral tegmental area contributes to drugprimed reinstatement of cocaine seeking. Brain Behav. Immun. 67, 130–138 (2018).

Gao, S. G. et al. Elevated osteopomin level of synovial fluid and articular cartilage is associated with disease severity in knee osteoarthritis patients. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18(1), 82–87 (2010).

Kevorkian, L. et al. Expression profiling of metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in cartilage. Arthritis Rheum 50(1), 131–141 (2004).

Pereira, T. V. et al. Effectiveness and safety of intra-articular interventions for knee and hip osteoarthritis based on large randomized trials: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 33(2), 207–217 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the support from the Postgraduate (Doctor) Research Innovation Project of Chongqing, China (CYB23292). We are grateful to members of the Professor Ping Li Laboratory of the Chinese Army Characteristic Medical Center for helpful discussions and assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ao Xiong: Investigation, Writing—original draft. Renping Xiong: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing—review & editing. Fei Luo: Data curation, Validation, Writing—review & editing. Zhaoxin Ma: Investigation. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

Animal studies were conducted in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines under protocol AMUWEC20181430 (Animal Ethics Committee of Army Medical University). All procedures adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The work has been carried out in accordance with either the U.K. Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986 and associated guidelines, the European Communities Council Directive 2010/63/EU or the National.

Consent for publication

We declare that the publisher has the authors’ permission to publish the relevant contribution.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiong, A., Ma, Z., Xiong, R. et al. Optimization of primary culture, inflammatory induction, and molecular analysis of fibroblast-like synoviocytes in a rat model of osteoarthritis pain. Sci Rep 15, 41557 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25494-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-25494-3